Abstract

Detection of motor dysfunction in genetic mouse models of neurodegenerative disease requires reproducible, standardized and sensitive behavioral assays. We have utilized a Center of Pressure (CoP) assay in mice to quantify postural sway produced by genetic mutations that affect motor control centers of the brain. As a positive control for postural instability, wild type mice were injected with harmaline, a tremorigenic agent, and the average areas of the 95% confidence ellipse, which measures 95% of the CoP trajectory values recorded in a single trial, were measured. Ellipse area significantly increased in mice treated with increasing doses of harmaline and returned to control values after recovery. We also examined postural sway in mice expressing mutations that mimic frontotemporal dementia with Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17) (T-279, P301L or P301L-NOS2−/− mice) and that demonstrate motor symptoms. These mice were then compared to a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease (APPSwDI) that demonstrates cognitive, but not motor deficits. T-279 and P301L-NOS2−/− mice demonstrated a significant increase in CoP ellipse area compared to appropriate wild type control mice or to mice expressing the P301L mutation alone. In contrast, postural instability was significantly reduced in APPSwDI mice that have cognitive deficits but do not have associated motor deficits. The CoP assay provides a simple, sensitive and quantitative tool to detect motor deficits resulting from postural abnormalities in mice and may be useful in understanding the underlying mechanisms of disease.

Keywords: Tremor, FTDP-17, mouse models, center of pressure assay, motor behavior, postural sway, neurodegeneration

Introduction

The development of multiple mouse models of human disease has led to the requirement for reliable, reproducible and sensitive assays of mouse behaviors (van der Staay and Steckler, 2002;Meredith and Kang, 2006). Behavioral phenotyping is particularly important as an outcome measure because of the potential relevance for direct comparison to human disease. Our lab has focused on mouse models of chronic neurodegenerative diseases such as frontotemporal dementia with Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17), Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Huntington’s disease (HD). Each of these diseases is associated with pathological changes in those regions of the brain that control motor behavior. For example in Huntington’s disease, abnormal gait and changes in muscle activity are typically observed and can be correlated with damage to the corticostriatal input to the striatal neuron pool as well as the striatum itself (Schilling et al, 1999; Sieradzan and Mann, 2001). Loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra in PD is well known to be associated with progressive motor dysfunctions that include bradykinesis and rigidity (Braak et al, 2004; Bhidayasiri, 2005; von Bohlen and Und Halbach, 2005; Meredith and Kang, 2006). In addition, neurodegenerative diseases such as Huntington’s and Parkinson’s disease demonstrate tremor (Hefter et al, 1987;Mangiarini et al, 1996; Bhidayasiri, 2005). In Parkinson’s disease the involuntary tremor resulting from loss of dopaminergic neurons in the basal ganglia is typically a mixture of postural and resting tremor and can be lessened with voluntary movements (Bhidayasiri, 2005). The other major type of tremor in the human population is essential tremor which is the most common form of action tremor and is produced by voluntary muscle contraction (Bhidayasiri, 2005).

Motor symptoms that are reminiscent of neurodegenerative diseases in humans can be at least partially reproduced in both pharmacological and genetic mouse models. For example, harmaline is a well-described tremorigenic compound that acts through modulation of dopamine release in the basal ganglia and the inferior olive nucleus (Miwa et al, 2000; Fowler et al, 2002). Harmaline treatment is associated with a dose-dependent increase in action tremor with a frequency of 10–12 Hz (Wang and Fowler, 2001; Martin et al, 2005). Treatment with 1-methy-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) produces motor symptoms in mice that mimic Parkinson’s disease, including akinesia and tremor (Haobam et al, 2005; von Bohlen and Und Halbach, 2005). These behavioral changes correlate with loss of tyrosine hydroxylase immunopositive neurons in the striatum and confirm that dopaminergic neuronal function is compromised. In mouse models of FTDP-17 that express mutated human tau, overt disease onset is commonly manifest by motor impairment and dystonia progressing to limb paralysis (Nasreddine et al, 1999; Lewis et al, 2000; Arendash et al, 2004; Ramsden et al, 2005). Changes in movement, thus, can be used as a reliable indicator of disease pathology and progression in rodent models of human disease.

A variety of behavioral tests are commonly used to study movement disorders in rodents, including the wire hang test for general muscle strength, the balance beam or pole test for general motor function, and the rotorod assay for motor coordination (Sango et al, 1996; Hamm, 2001; Arendash et al, 2004; Meredith and Wang, 2006). Measurement of postural instability and tremor in rodents has primarily relied on subjective measures such as counting of head shakes. More recently, however, new techniques using load sensors or force plate actometers have been developed for detection and quantification of mouse activities such as rotation, rearing activity and gait (Fowler et al, 2001; Martin et al, 2005). The force platform is particularly useful in detecting loss of balance (postural sway) by measuring differences in the center of pressure (CoP). This technique has recently been used to measure postural sway in a healthy elderly population and in patients with essential tremor (Masui et al, 2005; Bove et al, 2006).

We have applied a simplified “center of pressure” assay for use on mice in order to phenotype motor dysfunction in genetic mouse models of neurodegenerative diseases. In this study we used a well-established genetic model of human FTDP-17, that expresses the human P301L tau mutation and demonstrates hyperphosphorylated tau and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain stem, forebrain and spinal cord but does not exhibit dopaminergic neuronal loss (Lewis et al, 2000). P301L mice demonstrate motor deficits such as impaired rotorod and poor balance beam performance prior to paralysis in late disease stages (Arendash et al, 2004). A bigenic mouse created by crossing the P301L mouse to a NOS2−/− mouse was also examined since removal of NOS2 has recently been associated with enhanced tau pathology (Colton et al, 2006). We also tested a mouse model of amyloid deposition reminiscent of Alzheimer’s disease (APPSwID) that displays cognitive but not motor deficits (Miao et al, 2005; Xu et al, 2007). Finally, we used the T-279 mouse that models FTDP-17 and demonstrates loss of dopaminergic neurons in the striatum (Dawson et al, 2007). Overall, the CoP assay is simple to perform, is easily quantifiable and is highly sensitive allowing detection of significant differences in motor activity between closely related mouse models.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Transgenic mice (APPSwDI) containing the Swedish, Dutch (E22Q) and Iowa (D23N) APP mutations, were generated as described (Davis et al, 2004) and were a generous gift from Dr. William Van Nostrand, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY. P301L mice expressing the P301L human tau mutation were generated as described by Lewis et al (Lewis et al, 2000) and were a generous gift from Drs. Lewis and Hutton, Mayo Clinic at Jacksonville, Jacksonville, FL. Bigenic mice were produced by crossing P301L mice with NOS2−/− mice (B6 129P2NOS2 tau1Lau/J) (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor ME) mice. T-279 mice expressing the N279K human FTDP-17 tau mutation under the control of the human TAU promoter were generated and characterized by Dr. Hana Dawson. Control mice for the T-279 strain were generated from a backcrossed strain and were aged under the same conditions and for the same time period as the genetic strain. C57/Bl6 littermate mice bred in our facility served as control mice for all other strains. All mice were genotyped using standard procedures. Male and female mice were bred and housed under standard temperature and light conditions in an AAALAC/NIH approved facility.

Center of Pressure Apparatus

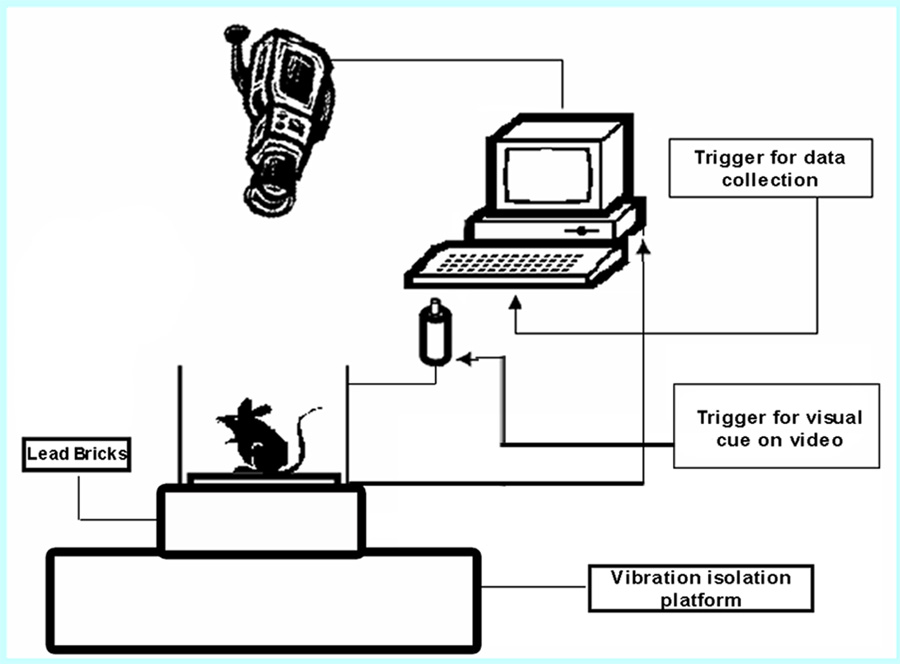

The Center of Pressure (CoP) analysis system is comprised of the AMTI Biomechanics Force Platform (Model HE6x6; Advanced Mechanical Technology Inc., 176 Waltham Street, Watertown, MA), automated data acquisition software (AMTI NetForce), analysis software (AMTI BioAnlaysis) and a digital video camera. The force platform was designed by AMTI to be sensitive enough to detect changes in force and moment initiated by tremor in 10–50 gm mice. Zumwalt et al (2006) have performed a detailed analysis of the force platform response linearity and accuracy. Reduction of spurious, externally -generated vibrations was accomplished by placing the force platform on a large inertial mass (lead bricks), which was then placed on a table-top vibration isolation platform (Model 66-500, Technical Manufacturing Corporation, 15 Centennial Drive, Peabody, MA). Finally, to prevent the mice from moving off of the platform, a plexi-glass box with a non-reflective inner surface was placed around the platform. The dimensions of the box were large enough to allow ¼ inch clearance between the box and platform. To provide a visual cue on the video at the time of measurement, a small, red LED was mounted inside the box near the top edge. This LED was activated by a small push-button switch connected to a battery. The placement of the box was checked prior to measurement of tremor to ensure that accidental interference of the force platform motion by the box did not occur. Figure 1 shows the general apparatus configuration.

Figure 1.

Basic schematic for the center of pressure apparatus.

Measurements

Each mouse was weighed and then placed onto the platform within the box. The video camera and acquisition program were activated and the mouse was allowed to explore the platform for approximately 1–2 minutes. In order to avoid measuring voluntary movements such as walking or grooming, the mouse was watched by the operator and a video image recorded for each force measurement. When the mouse was observed to be resting still, that is, remaining in a prolonged stationary position on all 4 legs with no overt motion, the operator initiated signal acquisition. The software was set to record the forces experienced by the force platform for the one second prior to signal initiation, which corresponded to the time the operator observed that the animal was standing still. To further confirm that the mouse did not exhibit active movements of the limbs or head, the video was activated by a remote trigger and verbal descriptions of the animal’s activity were recorded. In this manner, the video image of each force measurement could be used to confirm the “resting status” of each mouse. The measurements were repeated 8–10 times per mouse in each test period (approximately 30 mins).

Pharmacological induction of tremor

Harmaline hydrochloride (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis MO) was dissolved into normal saline and injected subcutaneously at the nape of the neck in young adult mice. Doses given were 5mg/4ml/kg and 10mg/4ml/kg. Onset of tremor usually occurred at 15–20 minutes post injection and was defined as the point where a resting tremor first became noticeable. Measurements of tremor were started 3–5 minutes after tremor onset for each dose. Mice that did not demonstrate visible tremor by 15 min were judged to be non-responders and were not used in the study. The mice were then returned to their cage for recovery and retested after 24 hours.

Analysis

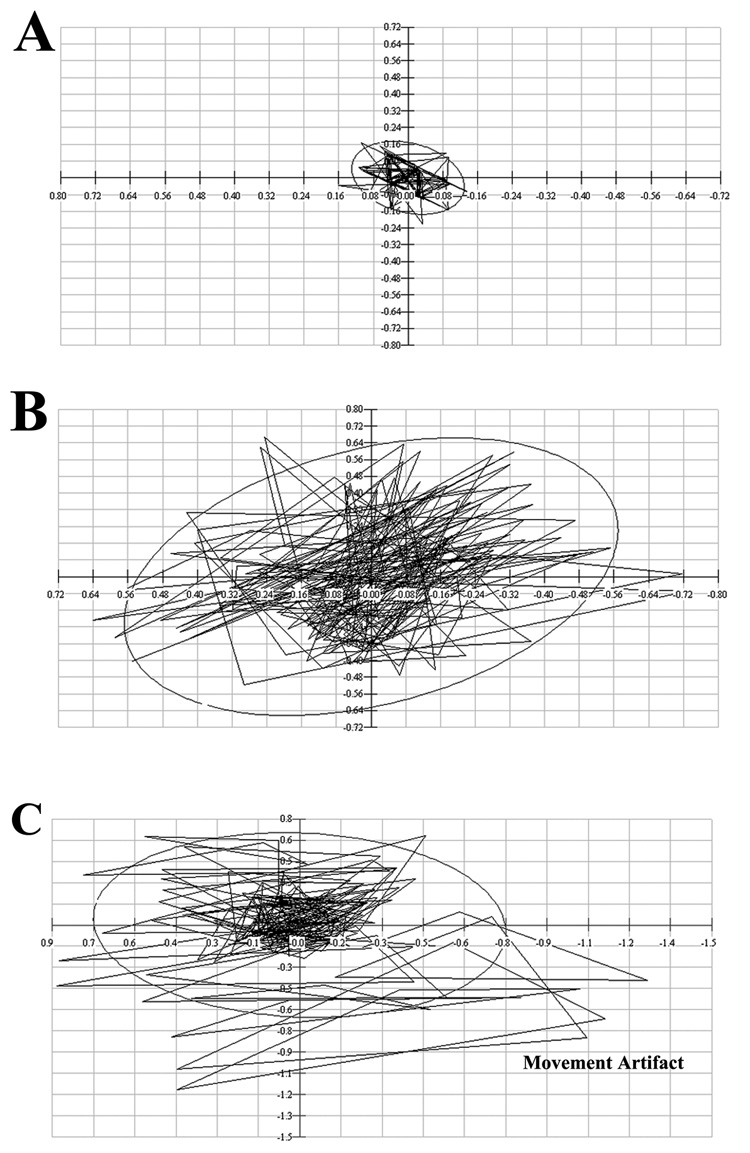

Using this plate type (Zumwalt et al, 2006) the center of pressure is calculated from the relative outputs of four vertical sensors. Changes in position of the center of pressure can then be used to measure body sway (Rocchi et al, 2006). The BioAnalysis Program analyzes CoP displacement trajectory through 180 degrees in a plane parallel to the ground. A 95% confidence ellipse encloses approximately 95% of the CoP trajectory values recorded in a single trial. The area of the ellipse is calculated and used to indicate the amount of sway exhibited by a mouse in a particular trial. Examples of 95% ellipses and their calculated areas (cm²) are shown in Figure 2. The ellipse areas in Fig 2A and B were generated by wild type (A) and P301L/NOS2−/− (B) mice, respectively and are plotted on the same axis scale. The video recording was also used to identify ellipses produced by animal’s voluntary movements (Fig 2C) so that these trials could be rejected from the study. To estimate the frequency of the whole body sway, the CoP displacements along the Y-axis for single 1 sec traces were displayed with respect to time. The frequency of trajectory displacement was measured for each trace and an average value obtained from at least 4 traces per animal.

Figure 2.

Typical graphical representations of 95% ellipse areas. A) Verified resting 95% ellipse area measured for a wild type mouse. Calculated area = 0.069 cm². Verified resting 95% ellipse area measured for a P301L-NOS2−/− mouse. Calculated area = 1.17 cm². Note :axis scale is the same in A and B. C) Non-usable area measurement from a P301L-NOS2−/− mouse. Calculated area= 1.54 cm². Axis scale is different from A or B. Note the large deviations outside of the calculated 95% ellipse area which are created by voluntary movements of the mouse.

Statistics

A minimum of 5 different 95% ellipse areas were measured for each mouse within a specific genotype and an average ellipse area was determined for each mouse. Data from each mouse of the same genotype within the same age range were then grouped and the average 95% ellipse area ± SEM was determined for each genotype. Significant differences between genotypes were determined using the unpaired student’s t test or ANOVA with p < 0.05 as significant. For drug treatment studies the average 95% ellipse area was measured before and during treatment. Significant changes were determined using a paired students t test.

Results

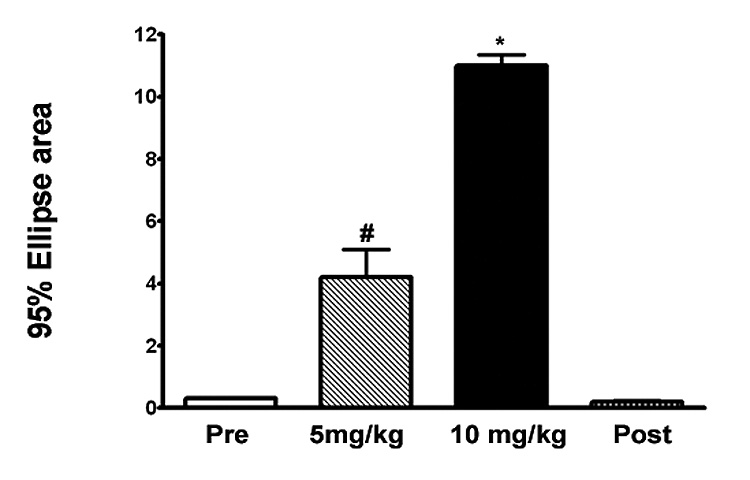

To verify that body sway could be detected in mice using CoP analysis, we injected young adult (18–25 weeks old), wild type mice with varying doses of harmaline, a known tremorigenic agent. Two concentrations of harmaline were studied using 2 separate groups of mice (5mg/kg and 10 mg/kg with 5 mice per dose) and CoP was performed before treatment, approximately 5 min after induction of tremors and approximately 24 hours post treatment. As shown in Fig 3, action tremors generated by harmaline produced a change in body sway that was dose dependent and readily reversible. Using each mouse as its own control, the average 95% ellipse area increased significantly for each dose (p < 0.03 or p < 0.001 for 5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, respectively; paired t test) compared to the untreated condition and returned to the baseline value after recovery. We also measured the y-axis frequency of displacement in harmaline-treated mice. The average frequency for mice injected with 5mg/kg harmaline was 12 ± 0.3 Hz (n=4 mice) compared to 3 ± 0.4 Hz for the same mice before treatment and 2.7 ± .04 Hz after recovery. Thus, the postural sway detected by CoP analysis demonstrated a tremor component typical of harmaline action in rodents.

Figure 3.

Dose-response curve for harmaline-induced tremor in wild type mice. Average 95% ellipse areas (± SEM) were calculated for 2 groups of young adult mice (18–30 weeks of age) prior to treatment, after subcutaneous injection of 5 mg/kg (group 1, n= 5 mice) or 10 mg/kg (group 2, n = 5 mice) harmaline and after recovery from treatment. Measurements were completed within 15 min of onset of visual tremors, animals were allowed to recover for 24 hours after tremors had ceased and 95% ellipse areas were again measured to obtain post-recovery values. Statistical significance was determined using the student’s paired t test for each group. # = p < 0.03; * p = 0.001.

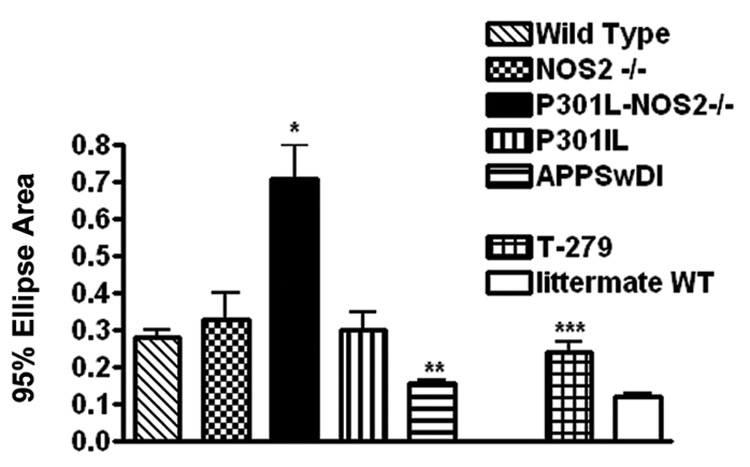

We also examined whether CoP analysis could detect more subtle differences in body sway by measuring the average 95% ellipse areas in different mouse models of neurodegenerative diseases. We used 4 mouse models of neurodegenerative disease including mice that express tau mutations (P301L, P301L-NOS2−/−, and T-279 mice), amyloid mutations (APPSwDI) and control mice (NOS2−/−, C57/Bl6 or appropriate littermate wild type mice). The average 95% ellipse areas (± SEM) for each strain are shown in Figure 4. Mice expressing the P301L human tau mutation on a NOS2 knockout background (P301L-NOS2−/− bigenic mice) showed a significant increase in postural sway compared to age-matched, wild type, NOS2−/− or P301L mice (Fig 4). A significant increase in the 95% ellipse area was also observed in the T-279 mouse compared to its littermate control strain while the 95% ellipse area in the APPSwDI mouse was significantly less than the 95% ellipse area observed in age-matched littermate wild type mice.

Figure 4.

Resting postural sway in mouse models of FTDP-17 and AD. Average 95% ellipse areas (±SEM) were calculated for wild type mice (n=5; 66–71 wks), NOS2−/− mice (n=9; 66wks), P301L-NOS2−/− mice (n=6; 65–71 wks), P301L mice (n=3; 66 wks) and APPSwDI (n=8; 59 wks). Data is also shown for T-279 mice (n=3; 59 wks) compared to their own littermate control wild type mice (n = 4; 59 wks). * = significant at p < 0.01 compared to wild type; ** = significant at p < 0.005 compared to wild type mice; *** = significant at p < 0.007 compared to littermate control mice. P values were determined using the unpaired student’s t test.

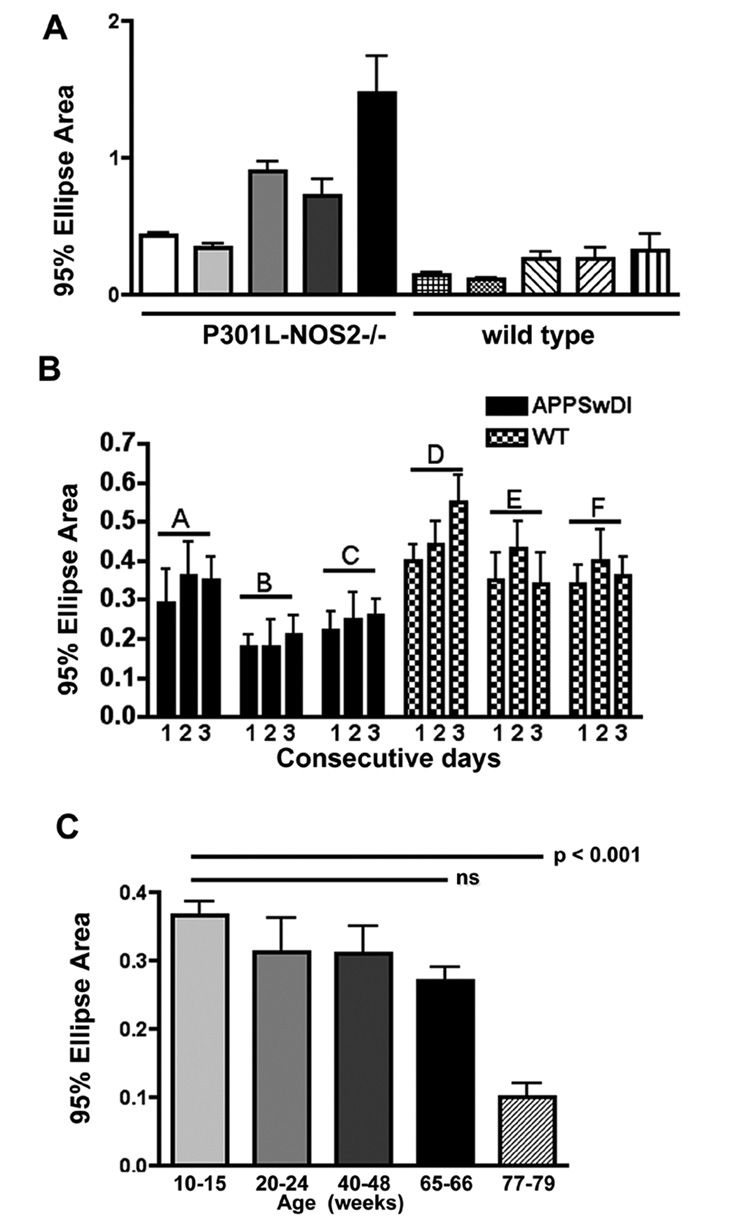

Since the above data indicated that statistically significant changes in postural sway and tremor could be detected using CoP analysis, we further examined the reliability and usefulness of the technique as a tool for measuring motor deficits. Differences between mice within a specific genetic strain are shown by comparing the average 95% ellipse areas (± SEM of areas) from 5 individual P301L-NOS2−/− mice and from 5 individual age-matched wild type control mice (Fig 5A). The different values for ellipse areas for individual mutated mice are likely to represent an inherent difference in disease severity levels between mice which is commonly observed in genetic mouse models (Arendash et al, 2004). We also examined the day-to-day repeatability of the CoP assay over 3 consecutive days (Fig 5B). Postural sway measurements were obtained from three different APPSwDI (66 wk) and 3 different C57/Bl6 wild type (12–15 wk) mice on 3 consecutive days at the same time each day. No significant variation in the 95% ellipse area was observed for each mouse over the 3-day measurement period. The average ellipse area was also independent of gender or body weight (data not shown). Finally, the effect of age on postural sway was examined by measuring the average 95% ellipse area in different age groups of C57/Bl6 mice (Fig 5C). No significant difference in the average 95% ellipse area was observed until 66 weeks of age. However, mice in the 77–79 wk old age group showed a significant reduction in postural sway compared to younger mice (p < 0.001, ANOVA).

Figure 5.

Variability in CoP analysis within strain, over 3 consecutive days of testing and with age of mice. Panel A- The average 95% ellipse area (± SEM) was determined for 5 individual P301L-NOS2−/− mice (65–71 wks) and 5 individual C57/Bl6 wild type mice (66–72 wks). Panel B- Postural sway measurements for three individual APPSwDI (A–C; 53wks) and 3 individual C57/Bl6 wild type mice (D–E; 10–12 wks) were taken over 3 consecutive days. No significant difference in the average 95% ellipse area was observed over the 3 day period for each individual mouse. Panel C- CoP analysis was performed on groups (4–6 mice/group) of C57/Bl6 wild type mice at different ages. No significant change in the average 95% ellipse area was observed from 10 to 66 weeks of age. A significant decrease in postural sway was observed in very old mice (77–79 wks ) (p < 0.001 by ANOVA).

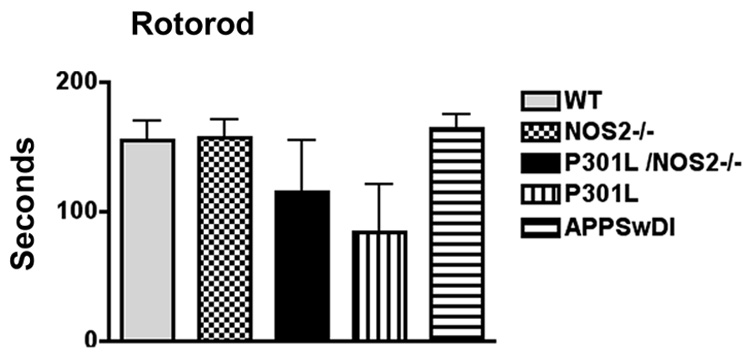

Rotorod measurements are often used to detect vestibulomotor abnormalities in mouse models of neurodegenerative diseases. To determine if CoP analysis for body sway was independent of general motor co-ordination skills as tested by rotorod, we also performed rotorod on the same mice used in the CoP assay. As shown in Fig 6 large variations in the duration on the rotating rod (seconds to fall) were observed for each of the mouse strains. No significant differences in the time on the bar were found between the P301L, P301L-NOS2−/−, NOS2−/−, APPSwDI or WT mice.

Figure 6.

Analysis of vestibulomotor function using rotorod. Mice used in CoP were also analyzed for generalized motor dysfunction as detected by the rotorod assay. No significant differences were observed between the P301L, P301L-NOS2−/−, NOS2−/−, APPSwDI and littermate wild type mice. Large standard errors for P301L and P301L-NOS2−/− mice reflect the large variability in individual mouse responses.

Discussion

Our data demonstrate that CoP analysis provides a simple and quantitative tool to examine motor deficits in pharmacological or genetic mouse models of neurodegenerative diseases. CoP analysis measures postural stability during quiet stance and provides an integrated measure of muscle activity in the inactive (stationary) rodent. Abnormal postural sway in rodents resting on 4 limbs is likely to represent a mixture of motor deficits; including tremor, imbalance and bradykinesia that each can lead to postural instability. For example, the inability to control the center of mass can be due to delayed responses leading to poor correction of sway and hence exaggerated postural imbalance (Rocchi et al, 2006). Tremor is also a major cause of postural sway and can be induced using pharmacological agents such as harmaline. We show that treatment of normal wild type mice with harmaline demonstrated a dose dependent increase in the 95% ellipse area with an average displacement frequency in the y-axis of about 12 Hz. The observed increased in postural sway is consistent with essential tremor, the primary type of tremor initiated by harmaline in mice (Martin et al, 2005) and verifies that CoP analysis in mice can detect changes in levels of postural sway.

Since mouse models are commonly used to examine mechanisms of disease and to test the efficacy of therapeutics, we explored the ability of CoP analysis to discriminate motor deficits in mice expressing pathological features of neurodegenerative disease. In this study we used genetic mouse models relevant to frontal temporal dementia with Parkinson- like symptoms (FTDP-17) and compared these to an AD mouse model that does not demonstrate motor deficits. The T-279 and P301L mouse strains express different human tau mutations but both show hyperphosphorylated tau and neurofibrillary tangles (Lewis et al 2000; Dawson et al, 2007). Motor abnormalities including dystonic posturing, impaired balance beam performance, and paralysis are evident in end stage pathology of P301L mutant mice (Arendash et al, 2004; Dawson et al, 2007). Although both strains demonstrate severe motor deficits, CoP analysis revealed a significant postural sway in the T-279 mouse but not the P301L strain compared to age-matched littermate control mice. Postural sway was also significantly greater in the P301L-NOS2−/− bigenic mouse and suggests that the genetic deletion of NOS2 may enhance the neurodegenerative process leading to the FTDP-17-like motor changes. Interestingly, a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease that expresses three mutations in the Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP) gene and demonstrates significant amyloid deposition as well as learning and memory deficits did not show increased tremor. Rather, a significant decrease in postural sway was observed and may correspond with the lack of motor deficits previously observed in this strain (Miao et al). The CoP analysis, thus, provides statistically relevant discrimination of motor changes between closely related mouse genetic models.

Importantly, the change in postural sway could be readily detected at stages of disease where rotorod was ineffective at discerning significant motor differences. Part of the difference in sensitivity between rotorod and CoP measurements may reflect the different areas of the brain that are involved in the motor actions. This is unlikely to solely account for the differences in motor outcomes, however, since postural adjustments are required to remain on a rotorod. Thus, common brain regions are likely to be activated for both the rotorod and CoP tasks. Rotorod performance is also well-known to vary from mouse to mouse and can be further altered by learning (Meredith and Wang, 2006). Unlike rotorod where a learning curve is shown over 3 days of testing (Hamm, 2001), no change in the average 95% ellipse area was observed over 3 days in mice tested for postural sway with the CoP analysis. It was also independent of gender and weight, both of which can alter performance on other motor tasks. However, postural sway is clearly dependent on the age and on the strain of mouse and emphasizes the importance of age-and littermate-comparisons.

Resting tremor is a dominant feature of PD that has predictive value of disease (Rocchi et al, 2004; Bhidayasiri, 2005). The mice models of FTDP-17 expressing human tau mutations demonstrated average displacement frequencies of around 6 Hz which was lower than the frequency (12Hz) for harmaline treatment in wild type mice. These data suggest that action (essential) tremor alone could not account for the postural sway. Instead it is likely that CoP analysis measurements are composed of multiple factors affecting motor function including resting tremor, action tremor and other motor actions that affect postural stability. Resting tremor in rodent models is difficult to measure and most clearly observed in rats with severe dopamine depletion only when a forelimb is positioned off the floor in a non-weight bearing posture (Cencei et al, 2002). Thus, although CoP analysis measures a mixture of motor actions, it does provide an integrated assessment of postural sway that likely includes resting tremor. This type of analysis may better reflect the pathophysiologcial condition associated with PD, however, since tremor in PD is frequently complex and includes both action tremors and resting tremors (Bhidayasiri, 2005).

Finally, nigrostriatal dopaminergic dysfunction is a principal cause of the motor symptoms observed in PD including the postural sway and resting tremor associated with this disease (Meredith and Wang, 2006; Rocchi et al, 2004; Rocchi et al 2006). A significant loss (28 ± 11%) of TH+ neurons compared to wild type littermate control mice has been observed in the substantia nigra of T-279 mice (Dawson et al, 2007) and, although not fully proven, is consistent with the increased postural sway. No dopaminergic neuronal loss has been reported for P301L or the APPSwDI strains and has not yet been assayed for the P301L-NOS2−/− bigenic strain.

The enhanced sensitivity of CoP analysis compared to other commonly used motor tasks such as the rotorod may allow correlation of neuronal changes at early stages of disease. In turn, detecting subtle disease related changes in motor function prior to significant progression of the disease could provide important information on disease mechanisms as well as opportunities to explore useful early therapeutic approaches. Thus, the CoP assay may be useful to detect early disease onset or therapeutic effectiveness in mouse models of disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank AMTI for their cooperative efforts in designing a suitable mouse CoP platform and for providing the necessary software for analysis.

Abbreviations

- APP

Amyloid Precursor Protein

- CoP

Center of Pressure

- FTDP-17

frontotemporal dementia with Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17

- HD

Huntington’s disease

- MPTP

1-methy-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine

- NOS2

Nitric Oxide Synthase 2

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- TH

Tyrosine hydroxylase

- TH+

Tyrosine hydroxylase immunopositive

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arendash G, Lewis J, Leighty R, McGowan E, Cracchiolo J, Hutton M, Garcia M. Multi-metric behavioral comparison of APPsw and P301L models for Alzheimer's disease: linkage of poorer cognitive performance to tau pathology in forebrain. Brain Res. 2004;1012:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.02.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhidayasiri R. Differential diagnsis of common tremor syndromes. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:752–762. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2005.032979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bove M, Marinelli L, Avanzino L, Marchese R, Abbruzzese G. Posturigraphic analysis of balance control in patients with essential tremor. Movement Disord. 2006;21:192–198. doi: 10.1002/mds.20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Ghebremedhim E, Rub U, Bratzke H, Del Tredici K. Stages in the development of Parkinson's disease related pathology. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;318:121–134. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0956-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenci MA, Whishaw IQ, Schallert T. Animal models of neurological deficits: how relevant is the rat? Nat Rev. 2002;3:574–579. doi: 10.1038/nrn877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colton C, Vitek M, Wink D, Xu Q, Cantillana V, Previti M, VanNostrand W, Weinberg J, Dawson H. NO synthase 2 (NOS2) deletion promotes multiple pathologies in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12867–12872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601075103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J, Xu R, Deane G, Romanov M, Previti M, Zeigler K, Zlokovic B, VanNostrand W. Early-Onset and Robust Cerebral Microvascular Accumulation of Amyloid β-Protein in Transgenic Mice Expressing Low Levels of a Vasculotropic Dutch/Iowa Mutant Form of Amyloid β-Protein Precursor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20296–20306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312946200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson H, Cantillana V, Vitek M. The tau N279K exon 10 splicing mutation recapitulates FDTP-17 tauopathy in a mouse model. J Neurosci. 2007 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5492-06.2007. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler S, Birkestrand B, Chen R, Moss S, Vorontsova E, Wang G, Zarcone TJ. A force-plate actometer for quantitating rodent behaviors: illustrative data on locomotion, rotation, spatial patterning, stereotypies, and tremor. J Neurosci Methods. 2001;107:107–124. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler S, Zarcone T, Vorontsova E, Chen R. Motor and associative deficits in D2 dopamine receptor knockout mice. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2002;20:309–321. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(02)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm RJ. Neurobehavioral assessment of outcome following traumatic brain injury in rats: an evaluation of selected measures. J Neurotrauma. 2001;18:1207–1216. doi: 10.1089/089771501317095241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haobam R, Sindhu K, Chandra G, Mohanakumar K. Swim-test as a function of motor impairment in MPTP model of Parkinson's disease: a comparative study in two mouse strains. Behav Brain Res. 2005;163:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefter H, Homberg V, Lange H, Freund H. Impairment of rapid movement in Huntington's disease. Brain. 1987;110:585–612. doi: 10.1093/brain/110.3.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J, McGowan E, Rockwood J, Melrose H, Nacharaju P, VanSlegtenhorst M, et al. Neurofibrillary tangles, amyotrophy and progressive motor disturbance in mice expressing mutant (P301L) tau protein. Nature Genetics. 2000;25:402–405. doi: 10.1038/78078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangiarini L, Sathasivam K, Seller M, Cozens B, Harper A, Hetherington C, Lawton M, Trottier Y, Lehrach H, Davies S, Bates G. Exon 1 of the HD gene with an expanded CAG repeat is sufficient to cause a progressive neurological phenotype in transgenic mice. Cell. 1996;87:493–506. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81369-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin F, Thu LA, Handforth A. Harmaline-induced tremor as a potential preclinical screening method for essential tremor medications. Mov Disord. 2005;20:298–305. doi: 10.1002/mds.20331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masui T, Hasegawa Y, Matsuyama Y, Sakano S, Kawasaki M, Susuki S. Gender differences in platform measures of balance in rural community dwelling elders. Arch Gerontol Geriat. 2005;41:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith GE, Kang UJ. Behavioral models of Parkinson's disease in rodents: A new look at an old problem. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1595–1606. doi: 10.1002/mds.21010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao J, Xu F, Davis J, Otte-Holler I, Verbeek M, Van Nostrand W. Cerebral microvascular amyloid beta protein deposition induces vascular degeneration and neuroinflammation in transgenic mice expressing human vasculotropic mutant amyloid beta precursor protein. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:505–515. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62993-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa H, Nishi K, Fuwa T, Mizuno Y. Differential expression of c-fos following administration of two tremorgenic agents: harmaline and oxotremorine. Neuroreport. 2000;11:2385–2390. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200008030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine Z, Loginov M, Clark L, Lamarche J, Miller B, Lamontagne A, Zhukareva V, Lee V, Wilhelmsen K, Geschwind D. From genotype to phenotype: a clinical pathological, and biochemical investigation of frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism (FTDP-17) caused by the P301L tau mutation. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:704–715. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199906)45:6<704::aid-ana4>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsden M, Kotilinek L, Forster C, Paulson J, McGowan E, SantaCruz K, Guimaraes A, Yue M, Lewis J, Carlson G, Hutton M, Ashe K. Age-dependent neurofibrillary tangle formation, neuron loss, and memory impairment in a mouse model of human tauopathy (P301L) J Neurosci. 2005;25:10637–10647. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3279-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocchi L, Chiari L, Cappello A. Feature selection of stabilometric parameters based on principal component analysis. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2004;42:71–79. doi: 10.1007/BF02351013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocchi L, Chiari L, Cappello A, Horak F. Identification of distinct characteristics of postural sway in Parkinson's disease: a feature selection procedure based on principal component analysis. Neurosci Lett. 2006;39:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sango K, McDonald M, Crawley J, Mack M, Tifft C, Skop E, Starr C, Hoffmann A, Sandhoff K, Suzuki K, Proia R. Mice lacking both subunits of lysosomal beta-hexosaminidase display gangliosidosis and mucopolysaccharidosis. Nat. Genet. 1996;14:348–352. doi: 10.1038/ng1196-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling G, Becher M, Sharp A, et al. Intranuclear inclusions and neuritic aggregates in transgenic mice expressing a mutant N-terminal fragment of huntingtin. Human Mol Gen. 1999;8:397–407. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieradzan K, Mann D. The selective vulnerability of nerve cells in Huntington's disease. Neuropath Appl Neurobiol. 2001;27:1–21. doi: 10.1046/j.0305-1846.2001.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Staay FJ, Steckler T. The fallacy of behavioral phenotyping without standardisation. Genes Brain Behav. 2002;1:9–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1601-1848.2001.00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bohlen Und Halbach O. Modeling neurodegenerative diseases in vivo review. Neurodegener Dis. 2005;2:313–320. doi: 10.1159/000092318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Fowler SC. Concurrent quantification of tremor and depression of locomotor activity induced in rats by harmaline and physostigmine. Psychopharmacol. 2001;158:273–280. doi: 10.1007/s002130100882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Grande AM, Robinson JK, Previti ML, Vasek M, Davis J, Van Nostrand WE. Early-onset subicular microvascular amyloid and neuroinflammation correlate with behavioral deficits in vasculotropic mutant amyloid beta-protein precursor transgenic mice. Neuroscience. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.043. E publication Feb 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumwalt A, Hamrick M, Schmitt D. A force platform for measuring ground reaction forces in small animal locomotion. J Biomech. 2006;39:2877–2881. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]