Abstract

ACh may help set the dynamics within neural systems to facilitate the learning of new information. Neural models have shown that if new information is encoded at the same time as retrieval of existing information already stored, the memories will interfere with each other. Structures such as the hippocampus have a distinct laminar organization of inputs that allows this hypothesis to be tested. In region CA1 of the rat hippocampus, the cholinergic agonist carbachol (CCh) suppresses transmission in stratum radiatum (SR), at synapses of the Schaffer collateral projection from CA3, while having lesser effects in stratum lacunosum-moleculare (SLM), the perforant path projection from entorhinal cortex (Hasselmo and Schnell, 1994). The current research extends support of this selectivity by demonstrating laminar effects in region CA3. CCh caused significantly greater suppression in SR than in SLM at low concentrations, while the difference in suppression was not significant at higher concentrations. Differences in paired-pulse facilitation suggest pre-synaptic inhibition substantially contributes to the suppression and is highly concentration and stratum dependent. This selective suppression of the recurrent excitation would be appropriate to set CA3 dynamics to prevent runaway modification of the synapses of excitatory recurrent collaterals by reducing the influence of previously stored associations and allowing incoming information from the perforant path to have a predominant influence on neural activity.

Keywords: perforant path, recurrent collaterals, presynaptic, muscarinic, acetylcholine

Acetylcholine (ACh) has been shown to play a vital role in learning and memory ((for a review see Hagan and Morris, 1988; Rasmusson, 2000)). An extensive range of experiments using ACh agonists and antagonists (Davis et al., 1971; Ghoneim and Mewaldt, 1977; Kopelman, 1986; Hagan and Morris, 1988; Whishaw, 1989; Fibiger, 1991) indicate a vital role for ACh in the encoding of new memories. Selective lesions of the primary cholinergic input to the hippocampus using IgG-192 saporin have been shown to influence attention and various aspects of cognitive behavior (Baxter et al., 1997; Janisiewicz et al., 2004), including causing transient impairments of spatial memory function (Vuckovich et al., 2004), but they may not always have strong mnemonic effects as some levels of hippocampal ACh may remain (Chang and Gold, 2004). A role for ACh may therefore be to help set the dynamics within neural systems to facilitate the learning of new information. Neural models have shown that if new information is encoded at the same time as retrieval of existing information already stored, the memories will interfere with each other and cause degradation, or a failure to accurately encode new information (Hasselmo and Bower, 1992; Hasselmo and Bower, 1993).

Impaired encoding with cholinergic blockade has been shown in human studies (Ghoneim and Mewaldt, 1975; Ghoneim and Mewaldt, 1977; Petersen, 1977). The administration of scopolamine, an ACh antagonist, prior to attempts to memorize word lists caused a deficit in encoding the information. However, when scopolamine was administered after encoding and prior to retrieval, no detriment was found. This would suggest that cholinergic modulation is vital to setting the dynamics necessary to encode new information. Similar selective encoding impairments have been shown in monkeys (Aigner et al., 1991) and in rats (Davis et al., 1971; Whishaw, 1989), and recently localized injections of scopolamine into regions CA1 and CA3 have both been shown to selectively interfere with encoding (Rogers and Kesner, 2003).

In the hippocampus, extrinsic and intrinsic fibers are separated into distinct layers (see Amaral and Witter, 1989 for a review). The traditional trisynaptic model of the hippocampus depicts extrinsic information from the entorhinal cortex projecting to the dentate gyrus through the perforant path fibers, the dentate gyrus then projecting through the mossy fibers to region CA3, and region CA3 then projecting through the Schaffer collaterals to region CA1. This simplified version, however leaves out critical aspects. Extrinsic activity (the new incoming information) from entorhinal cortex layers II and III also arrives through the perforant path synapses onto hippocampal pyramidal dendrites in stratum lacunosum-moleculare (SLM) in both region CA1 and CA3. Intrinsic activity of hippocampal pyramidal cells spreads through synapses of the Schaffer collaterals to pyramidal cell dendrites in stratum radiatum (SR) of CA1 and through the longitudinal association fibers to synapses in SR of CA3. Input from granule cells in the dentate gyrus spreads through sparse synapses of the mossy fibers in stratum lucidum of CA3. Cholinergic modulation suppresses the excitatory transmission at the intrinsic fiber synapses in SR of CA1 while allowing the excitatory transmission of the extrinsic synapses in SLM of CA1 to predominate as shown by Hasselmo and Schnell (1994). Such selective presynaptic inhibition has been shown in a neural network model of region CA3 to control the amount of overlap between new and previously encoded information (Hasselmo et al., 1995). With no suppression, previously encoded information dominates in region CA3 activity and this activity is passed complete to CA1 with little or no influence from new incoming information. This impairs the capacity to effectively encode new associations.

In contrast, a high level of suppression causes the new incoming information to be encoded in the CA3 region with no influence from previously encoded information and to be passed to region CA1 relatively unaltered. Levels between these absolutes allow proportionate amounts of chunking or interleaving of the new and old information, producing effective integration of old and new memories. Loss of NMDA receptors in CA3 has been shown to retard acquisition of new goal locations while not interfering with previously learned locations (Nakazawa et al., 2003), and loss of just the longitudinal fibers (recurrent collaterals and mossy fibers) in CA3 also attenuated spatial tasks and interfered with recall of prior learned associations (Steffenach et al., 2002) further supporting a role for the recurrent collaterals in the rapid acquisition of patterns, and the recall or reconstruction of prior memories.

While there has been a great deal of research on cholinergic suppression in region CA1 (Hounsgaard, 1978b; Hounsgaard, 1978a; Dutar and Nicoll, 1988; Sheridan and Sutor, 1990; Hasselmo and Schnell, 1994; McQuiston and Madison, 1999; Hasselmo and Fehlau, 2001), there has been relatively little research on specific effects of ACh in region CA3. Because injections of ACh agonist scopolamine directly into CA3 cause similar deficits in learning as injections into CA1 (Rogers and Kesner, 2003), it is important to discover if ACh has similar selective inhibition in CA3. Cholinergic suppression of the CA3 recurrent collaterals has been demonstrated (Hasselmo et al., 1995), but the study did not verify different levels of suppression between the SR and SLM. Others have also demonstrated ACh suppression of the recurrent collaterals in CA3, and that this suppression is by direct action on this pathway, and not through indirect means of ACh modulation of GABAergic interneurons (Vogt and Regehr, 2001). A minimal effect of ACh modulation on the mossy fiber projections to CA3 (Romo-Parra et al., 2003) has also been demonstrated, although here ACh exhibits an indirect and lessened modulation of the mossy fibers through activation of GABAergic interneurons (Vogt and Regehr, 2001). While this prior research has addressed the modulation of recurrent collaterals and therefore the processing of internal information, or the indirect input via the dentate gyrus, no research addressing ACh modulation of the direct perforant path-CA3 connectivity has been conducted to determine potential ACh effects on the processing of new incoming information from the entorhinal cortex through this pathway.

If region CA3 with its recurrent collaterals serves an autoassociative role, as previous models have suggested (Hasselmo et al., 1996), a similar pattern to CA1 should be seen in CA3 and the recurrent fibers in SR should show greater suppression from ACh and its agonists than the incoming perforant path fibers in SLM. Recent research however, has shown that in the rat hippocampus, the cholinergic projection is significantly less dense in SLM of CA1 as compared to SR of CA1 (Aznavour et al., 2002). This finding correlates well with the prior findings of greater cholinergic suppression in SR of CA1 than SLM of CA1. The Aznavour et al. (2002) study also, however, found that the cholinergic projection to SLM of CA3 was significantly denser than the projections to SR of CA3. If the actual suppression in CA3 follows the relationship seen in CA1, then it is possible that in CA3, ACh has greater inhibitory effects on the perforant path, and allows the recurrent collaterals to be the predominant input to CA3 pyramidals, as has been projected by other neural models of CA3 (Levy, 1996). We therefore conducted the following experiment to determine the relationship of cholinergic inhibition of transmission between CA3 SR and SLM. This data has been previously presented in abstract form (Kremin and Hasselmo, 2003).

Materials and Methods

All experiments utilized male Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River). Animals varied in age from 5 weeks to 8 weeks. Animals were deeply anesthetized with halothane, quickly decapitated and the brains removed in 4°C ACSF (concentrations in millimolar: NaCl [124.0], KCl [2.5], MgSO4 [1.3], Dextrose [10.0], NaHCO3 [26.0], KH2PO4 [1.2], CaCl2 [2.4]) oxygenated by bubbling 95% O2/5% CO2 through the solution. The brain was mounted on its dorsal surface in a manner which provided a 10-15° offset from horizontal to optimize preservation of the Schaffer collateral fibers and sliced in oxygenated 4°C ACSF using a Campden vibroslicer. Slices were cut at 400 micron thickness. The mid septotemporal slices were retained and hippocampal regions dissected from other tissue.

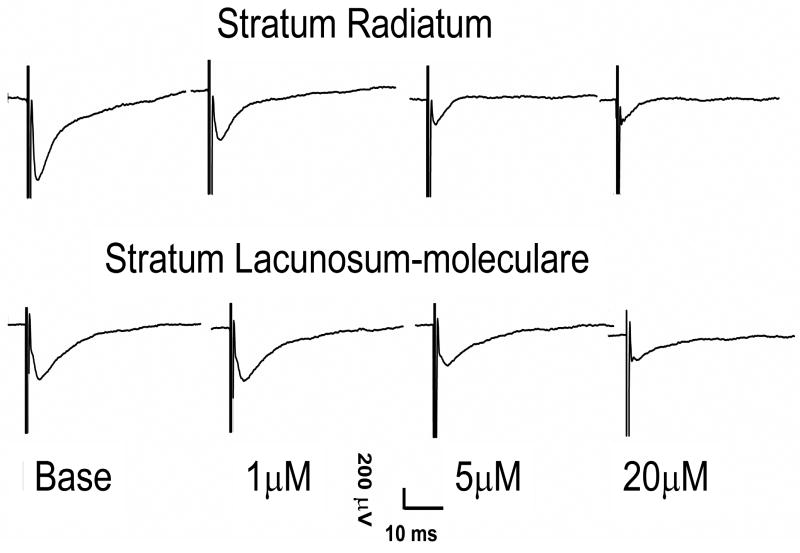

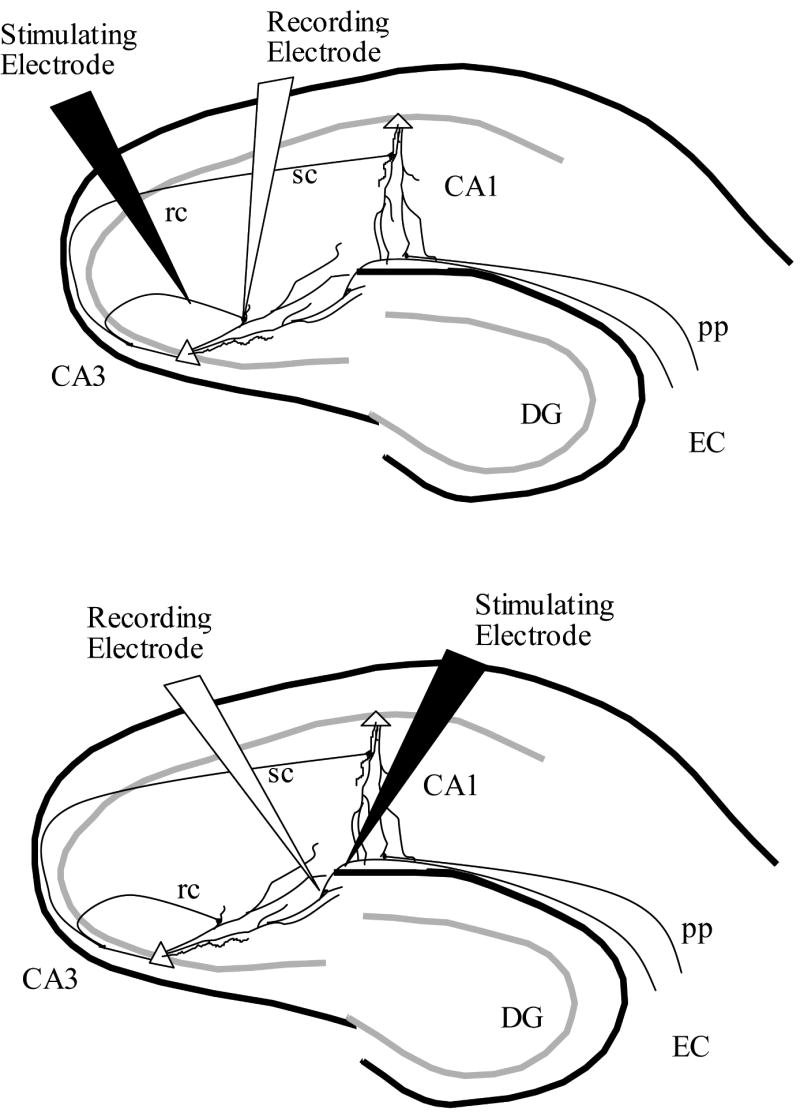

The slices of the hippocampus were stored in room temperature ACSF. After a minimum of 1 hour, individual slices were transferred to the recording chamber (Fine Science Tools) and submerged in continuously flowing, oxygenated ACSF at 33-34°C. Unipolar stimulating electrodes (WPI Inc) were placed in either the SR of CA3 to activate recurrent collateral fibers to cause evoked potentials in SR, or placed in SLM of CA3 to activate perforant path fibers to cause evoked potentials in SLM. Recording electrodes were pulled from 1mm borosilicate capillary tubes (WPI Inc) using a Sutter Instruments model P-87 pipette puller and filled with 2 M NaCl (3-6 MΩ resistance) and placed in either SR or SLM of CA3 corresponding to stimulating electrode placement. Figure 1 depicts typical placement in SR (top) and SLM (bottom) of the electrodes for all experiments presented here. Paired-pulse stimulation was delivered with a 100ms ISI, with pulse pairs applied every 10s (Neuro Data Instruments PG4000 digital stimulator and SIU90 stimulus isolation unit). Data were acquired and recorded using an A-M Systems Model 1800 AC Amplifier connected to a Micro1401 ADC providing input to Spike2 software (Both Cambridge Electronic Designs) running under Windows 2000.

Figure 1.

Once potentials were established, they were allowed to stabilize for a minimum of 30 minutes before experimental runs. All suppression measures are reported as mean percent suppression from baseline ± SEM. After the stabilization period, recording commenced with a 10 minute baseline, followed by a 10 minute perfusion of either 1μM, 5μM, 20μM, 50μM, or 100μM carbachol (CCh; Sigma), followed by a 20 minute washout period to insure fEPSPs returned to a minimum of 85% of baseline. The 20μM concentration was added to better define the dose response-curve. Multiple trials were conducted on each slice, with perfusions applied in order of increasing concentrations. No more than 1 trial of each concentration was conducted on a single slice. Figure 2 depicts a typical fEPSP under baseline conditions, 1μM, 5μM, and 20μM CCh recorded in both the SR and SLM. The difference in suppression between SR and SLM is evident.

Figure 2.

Any trials in which the potential failed to reach 85% of baseline during wash were discarded, and no further experiments were run on that slice. The average amplitude of 10 fEPSPs before perfusion was used to establish baseline amplitude. The average of the last ten trials after potentials reached a stable minimum and before switching to washout solutions were used to generate an average percentage suppression value for that phase of the trial. Percentage suppressions were analyzed using a MANOVA statistic (SPSS 11.0) for concentration and group, with planned comparisons of each dose.

Results

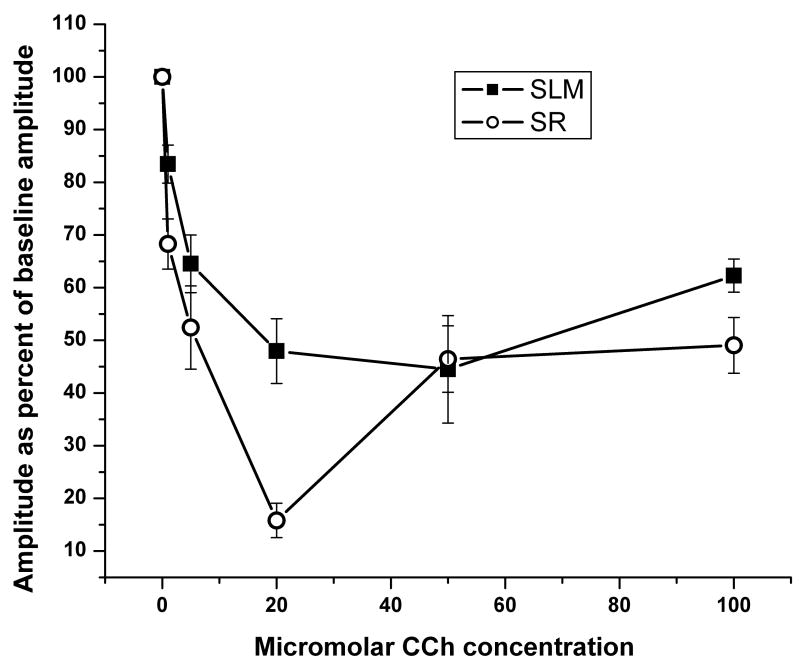

Primary Pulse

CCh inhibits synaptic transmission with laminar selectivity in CA3 similar to the pattern of inhibition seen in CA1. As shown in Figures 2 and 3, stimulus-induced fEPSPs recorded in SLM showed significantly less suppression than induced fEPSPs in SR (1,72, F = 19.57, p <.001). As expected, a significant overall effect of CCh concentration was found (6,72, F = 25.61, p < .001) with increasing concentration showing a standard dose response curve in SLM, and a biphasic curve in SR as has also been shown in mouse CA1 SR using these same concentrations (Kremin et al., 2006). The CCh-induced inhibition in both strata was completely eliminated by atropine challenge. A concentration-by-stratum interaction was also found (6,72, F=4.47, p = .001). For concentrations below 50μM, these results are similar to the suppression in SR that has been previously demonstrated (Hasselmo et al., 1995). Specifically, 1 μM CCh shows significantly less suppression in SLM (n=9, 16.6%±3.6) than in SR (n=4, 31.7%±4.8; p=.03), and 20 μM showed less suppression in SLM (52.1%±6.1) than SR (84.2%±3.3; p<.01). However, 5 μM failed to show significant differences in SLM (35.5%±5.5) compared to SR (47.6%±7.9, p=.22 ). 50 μM showed no significant differences in suppression in SLM (51.3% ±13.2) than SR (53.6% ±6.3, p=.87), with 100 μM also failing to show a significant difference in SLM (37.7%±3.1) than SR (49.1% ±7.6, p=.22).

Figure 3.

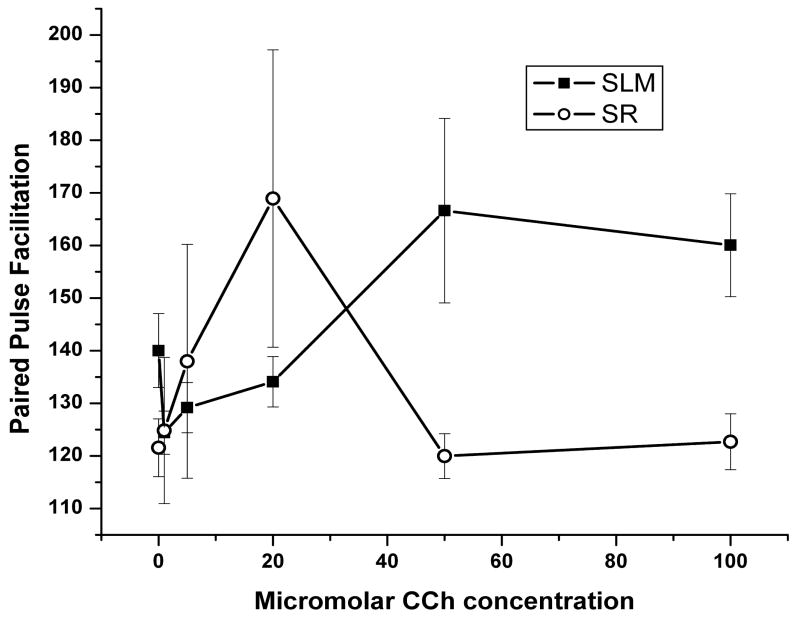

Paired Pulse Facilitation

As illustrated in figure 4, the effect of CCh concentration on paired pulse facilitation (PPF) of the above trials was significant (6,72, F = 2.42, p = .03) and CCh caused significantly different PPF in SR than SLM (1,72, F = 8.03, p = .006). As increases in PPF have been associated with presynaptic inhibition, these findings suggest that CCh exhibits significantly different pre-synaptic inhibition in SR than in SLM. Individual concentration analyses failed to detect significant differences in PPF between SR and SLM during baseline (1,22, F = 3.72, p = .07), 1 μM perfusion (1,11, F ≪ 1) or 5μM perfusion (1,15, F≪1). 20μM perfusion appeared to exhibit greater PPF in SR than SLM, but the differences failed to reached significance (1,11, F = 3.29, p = .09). At 50μM concentration, the trend in stratum specific PPF reversed with SLM showing significantly greater PPF than SR (1,6, F = 22.68, p = .003), Similarly, 100μM perfusion induced significantly greater PPF in SLM than in SR (1, 5, F = 13.11, p = .015).

Figure 4.

Discussion

Our results indicate that acetylcholine causes differential presynaptic inhibition of glutamatergic transmission in SR versus SLM of region CA3 of the rat hippocampus. Similar to region CA1 of both the mouse (Kremin et al., 2006) and rat (Hasselmo and Schnell, 1994), ACh inhibits glutamatergic transmission at intrinsic fibers (recurrent collateral synapses in SR) to a significantly greater degree than the inhibition exhibited at extrinsic fibers (perforant path synapses in SLM) in region CA3. These results support the theory that ACh plays a vital role in setting the dynamics of regions CA1 and CA3 of the hippocampus to preferentially process either intrinsic information or extrinsic information.

Further, our result support the hypothesis that recurrent collaterals are subject to a different dose-dependent pattern of cholinergic pre-synaptic inhibition of glutamatergic transmission compared to the perforant path. While the recurrent collaterals show a predominant increase in PPF around the 20 μM concentration and then return to baseline levels, perforant path inputs show a slight decrease from baseline levels of PPF with initial low concentrations, and then build to a maximal PPF at the 50 μM concentration, and then maintain an elevated level of PPF at 100 μM concentration. This difference may serve to bias the input to the CA3 pyramidal cells. While postsynaptic effects of ACh (i.e.: on the membrane potential of pyramidal cell dendrites) may be similar at any given phase of cholinergic modulation during theta activity, the release of glutamate from the recurrent collaterals and the perforant path synapses could be independently inhibited by a small variation in ACh concentration. With regard to the time course of theta rhythm oscillations, the sensitivity to differences in concentration indicates that the dynamics of modulation can change dramatically during the time necessary for the concentration to fall by only about one half of its initial value (from 50 μM to 20 μM). The rhythmic activity of cholinergic neurons in the medial septum (Brazhnik and Fox, 1999) could result in changes in acetylcholine concentration that might cause rhythmic changes in network dynamics in region CA3.

Network Dynamics

As predicted by neural models of the hippocampus from this lab (Hasselmo et al., 1995; Hasselmo et al., 1996; Hasselmo et al., 2002), experimental results show that in hippocampal region CA3 ACh causes a greater suppression of glutamatergic transmission in SR than in SLM, and has a stratum-specific, dose-dependent pattern of presynaptic inhibition. These findings extend to region CA3 the previous findings of selective suppression of the SR intrinsic fiber synaptic transmission as opposed to SLM extrinsic fibers synaptic transmission in CA1 of rats (Hasselmo and Schnell, 1994) and mice (Kremin et al., 2006). These findings provide further support for network models of the hippocampus that rely on selective suppression of the retrieval of intrinsic information to prevent interference with incoming new information (Hasselmo et al., 1995; Hasselmo and Wyble, 1997).

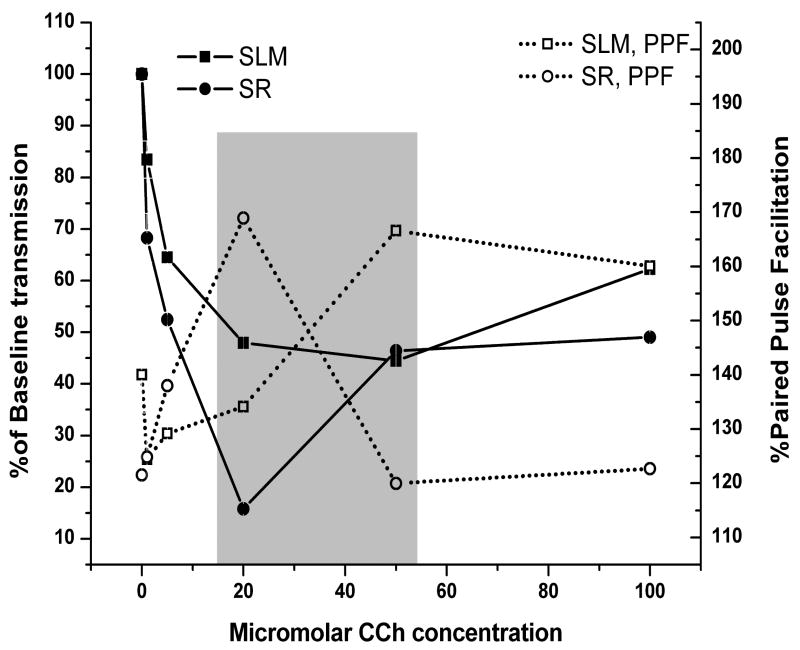

Previous studies demonstrated that effects of acetylcholine at muscarinic receptors are unlikely to decay quickly enough to allow for switching between extrinsic (perforant path) and intrinsic (recurrent collaterals & Schaffer collateral) inputs (Hasselmo and Fehlau, 2001) within single cycles of theta. In the previous study, a picospritzer was used to apply ACh locally to the recording electrode site with varying intervals between pressure pulse injection and synaptic stimulation. This allowed measurement of the time required for the clearance of the effect of the applied ACh. The results of that study suggested that it would take several seconds (far longer than a single theta cycle) for suppression in stratum radiatum to return to baseline after application of ACh. Our data, however, suggest that the biasing of intrinsic versus extrinsic inputs could occur during a continuous cholinergic tone, and would only require that the concentration varies in small amounts, such as during theta cycles, and that fully clearing ACh would not be required. As seen in Figure 5, when PPF and overall suppression are consider together, a reversal of pre-synaptic inhibition occurs from perforant path to recurrent collaterals fibers between the 20 and 50 μM concentrations (see box in figure). While no one has currently reported half-life figures for ACh at a hippocampal synapse, a 1.4ms half-life has been reported for ACh clearance from neuromuscular junction synapses (Katz and Miledi, 1973). As theta phases correspond to periods of approximately 83 to 166 ms (6-12Hz), ACh clearance from the hippocampal synapses could be substantially slower, and would not need to be completely cleared, to still be able to alternately bias inputs toward extrinsic information or intrinsic information during a single cycle of theta.

Figure 5.

Physiological implications

The cholinergic innervation of the hippocampus reaches all lamina of the hippocampus and appears to disperse among all cell types and at various loci throughout cells (Aznavour et al., 2002). It does however appear that there is a gradation of ACh fiber and varicosity concentrations with the highest density in stratum pyramidale, followed by SR, and the lowest density in SLM (Aznavour et al., 2002) in region CA1. This would seem to suggest that ACh levels would follow a corresponding gradation, and in CA1 the amount of cholinergically induced inhibition of synaptic transmission does follow a similar gradation of efficacy (Hasselmo and Schnell, 1994). In region CA3, however, Aznavour et al. (2002) found the density of fibers and varicosities between SR and SLM reversed. Our findings suggest that while there is a greater density of ACh positive fibers in SLM, the actual sensitivity to ACh presynaptic inhibition of glutamatergic transmission is much greater in SR than SLM, opposite from the pattern of the density of ACh fibers. The greater density of cholinergic fibers in SLM could, however, contribute to nicotinic enhancement of field potentials in SLM (Giocomo and Hasselmo, 2005).

Reports suggest that the majority of ACh modulation in the hippocampus may be primarily nonsynaptic, with only approximately 7% of ACh axonal varicosities in the CA fields synaptically located (Umbriaco et al., 1995; Descarries, 1998) and therefore cholinergic effects could involve volume transmission. With such a small proportion of ACh modulation at specific synaptic contacts, the level of ACh receptor expression, the distribution of subtypes of ACh receptors, as well as the postsynaptic and presynaptic localization in a given area may be the determining factor as to how much and what type of effect ACh has in vivo. Therefore, measurements of the activity of ACh on synaptic transmission and neuronal excitability may be the most accurate measurement of selectivity in ACh modulation, rather than the density of fibers. This is supported by similar finding of greater suppression of synaptic potentials in CA3 of SR than SLM in vivo as demonstrated by Kosub and Derrick (2003). Both in vivo research and the in vitro research presented here support a greater suppression of the recurrent collaterals synaptic transmission as opposed to the synaptic transmission from the perforant path.

Relationship to behavioral role of acetylcholine

The physiological data on laminar selectivity of cholinergic modulation presented here supports a role for acetylcholine in enhancing the influence of afferent input relative to excitatory recurrent excitation. This could enhance encoding of new information (Hasselmo et al., 1995), but could also be interpreted as enhancing attention to sensory stimuli relative to internal processing (Hasselmo and McGaughy, 2004). These effects could underlie the strong impairments of encoding shown with blockade of muscarinic receptors with antagonists such as scopolamine (Davis et al., 1971; Ghoneim and Mewaldt, 1977; Kopelman, 1986; Hagan and Morris, 1988; Whishaw, 1989; Fibiger, 1991). Other studies (Cahill and Baxter, 2001; Janisiewicz et al., 2004; Fletcher et al., 2007) have used 192 IgG-saporin to selectively lesion cholinergic neurons in the medial septum/diaganol band of Broca, the primary source of cholinergic innervation to the hippocampus. In contrast to the clear mnemonic effects of cholinergic antagonists, these selective lesion studies cause only transient impairments to spatial memory function (Vuckovich et al., 2004). However, saporin lesions of cholinergic hippocampal innervation do cause impairments of attentional parameters that are consistent with the selective modulation of synaptic transmission shown here (Baxter et al., 1997; Janisiewicz et al., 2004). In addition, other research using 192 IgG-saporin lesions and in vivo microdialyses (Chang and Gold, 2004) has suggested that substantial cholinergic activity is left in the hippcampus after 192 IgG-saporin lesions, and that the attenuation of ACh activity is sufficient to disrupt an alternation task. In agreement with our findings of small concentration changes having large effects, the preserved but attenuated cholinergic activity post 192 IgG-saporin lesions may be sufficient in simpler tasks with low levels of interference between learning and recall, while more complex tasks with greater interference risks may require a fully functional ACh projection for accurate learning and recall.

Relationship to other effects of acetylcholine

Neural models of CA3 function have shown that a laminar-selective suppression of transmission in CA3 can provide a necessary separation of intrinsic versus extrinsic information. The current findings show physiological evidence that this selective suppression does occur in the hippocampus. Also important in these models is a presynaptic locus for the effects of this selective suppression, and the current findings support ACh exerting presynaptic suppression of glutamatergic transmission in SR of CA3, as has been suggested by prior work in CA1 (Dutar and Nicoll, 1988; Sheridan and Sutor, 1990). As increases in PPF have been suggested to be evidence of presynaptic effects (Valentino and Dingledine, 1981; Zucker, 1999; Vogt and Regehr, 2001), our finding of significant enhancement of PPF in SR and SLM suggest a presynaptic effect of ACh on synaptic transmission in region CA3.

ACh has been shown to have a multitude of actions. ACh or its agonists have been shown to enhance LTP in the CA1 region of the hippocampus (Blitzer et al., 1990) and dentate gyrus (DG, Natsume and Kometani, 1997), enable LTP in piriform cortex (Patil et al., 1998), induce an NMDA-independent form of LTP (Auerbach and Segal, 1994) as well as causing increased excitability (Markram and Segal, 1992; Marino et al., 1998). In addition, ACh has also been shown to suppress glutamatergic transmission (Hounsgaard, 1978b; Hounsgaard, 1978a; Valentino and Dingledine, 1981; Hasselmo and Bower, 1992; Hasselmo and Schnell, 1994; Hasselmo et al., 1995; Levey, 1996; Bouron and Reuter, 1997; Kimura and Baughman, 1997; Patil and Hasselmo, 1999). Paradoxically, it has been shown that when cholinergic suppression of the Schaffer collaterals is strongest is also when induction of LTP in pyramidal dendrites is easiest (Natsume and Kometani, 1997). Therefore, at the point when LTP is most easily induced in pyramidals, ACh also provides presynaptic suppression of recurrent collaterals fibers further biasing the synaptic transmission levels toward allowing greater perforant path synaptic efficacy, and therefore much higher probability of perforant path synaptic activity dominating the induced activity in CA1 pyramidals. At concentrations higher than those required for maximal suppression of recurrent collaterals, we find that the presynaptic inhibition of the perforant path synapses is greater than the presynaptic inhibition of recurrent collaterals, which would provide a physiological state similar to the one proposed by Levy (1996) for accurate sequence retrieval by the CA3 region.

Neural models of the hippocampus have provided many hypotheses to be tested, including whether the recurrent collaterals pathway or the perforant path is suppressed to a greater degree during learning. Our results support a significantly greater suppression of the recurrent collaterals as compared to the perforant path. Further, our results suggest that there is a great deal of ACh induced presynaptic inhibition in recurrent collaterals at lower concentrations and little to no presynaptic inhibition in the perforant path at these same concentrations, and that this biasing reverses at higher concentrations. This data supports models suggesting that the dominant influence on CA3 activity can shift between the perforant path input and input from the synapses of recurrent collaterals.

Acknowledgments

This work supported by NIMH 60013, NIMH 61492, NIDA 16454, NSF SBE 0354378 and the Silvio O. Conte Center MH71702.

List of Abbreviations

- Ach

Acetylcholine

- CCh

carbachol

- fEPSP

field excitatory post synaptic potential

- MANOVA

multivariate analysis of variance

- PPF

paired pulse facilitation

- SLM

stratum lacunosum-moleculare

- SR

stratum radiatum

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aigner TG, Walker DL, Mishkin M. Comparison of the effects of scopolamine administered before and after acquisition in a test of visual recognition memory in monkeys. Behav Neural Biol. 1991;55:61–67. doi: 10.1016/0163-1047(91)80127-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral DG, Witter MP. The three-dimensional organization of the hippocampal formation: a review of anatomical data. Neuroscience. 1989;31:571–591. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach JM, Segal M. A novel cholinergic induction of long-term potentiation in rat hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:2034–2040. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.4.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aznavour N, Mechawar N, Descarries L. Comparative analysis of cholinergic innervation in the dorsal hippocampus of adult mouse and rat: a quantitative immunocytochemical study. Hippocampus. 2002;12:206–217. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter MG, Holland PC, Gallagher M. Disruption of decrements in conditioned stimulus processing by selective removal of hippocampal cholinergic input. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5230–5236. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05230.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blitzer RD, Gil O, Landau EM. Cholinergic stimulation enhances long-term potentiation in the CA1 region of rat hippocampus. Neurosci Lett. 1990;119:207–210. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90835-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouron A, Reuter H. Muscarinic stimulation of synaptic activity by protein kinase C is inhibited by adenosine in cultured hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12224–12229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazhnik ES, Fox SE. Action potentials and relations to the theta rhythm of medial septal neurons in vivo. Exp Brain Res. 1999;127:244–258. doi: 10.1007/s002210050794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill JF, Baxter MG. Cholinergic and noncholinergic septal neurons modulate strategy selection in spatial learning. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:1856–1864. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Q, Gold PE. Impaired and spared cholinergic functions in the hippocampus after lesions of the medial septum/vertical limb of the diagonal band with 192 IgG-saporin. Hippocampus. 2004;14:170–179. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JW, Thomas RK, Adams HE. Interactions of scopolamine and physostigmine with ECS and one trial learning. Physiology and Behavior. 1971;6(3):219–222. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(71)90029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descarries L. The hypothesis of an ambient level of acetylcholine in the central nervous system. J Physiol Paris. 1998;92:215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(98)80013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutar P, Nicoll RA. Classification of muscarinic responses in hippocampus in terms of receptor subtypes and second-messenger systems: electrophysiological studies in vitro. J Neurosci. 1988;8:4214–4224. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-11-04214.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fibiger HC. Cholinergic mechanisms in learning, memory and dementia: a review of recent evidence. Trends Neurosci. 1991;14:220–223. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90117-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher BR, Baxter MG, Guzowski JF, Shapiro ML, Rapp PR. Selective cholinergic depletion of the hippocampus spares both behaviorally induced Arc transcription and spatial learning and memory. Hippocampus. 2007;17:227–234. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoneim MM, Mewaldt SP. Effects of diazepam and scopolamine on storage, retrieval and organizational processes in memory. Psychopharmacologia. 1975;44:257–262. doi: 10.1007/BF00428903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoneim MM, Mewaldt SP. Studies on human memory: the interactions of diazepam, scopolamine, and physostigmine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1977;52:1–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00426592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giocomo LM, Hasselmo ME. Nicotinic modulation of glutamatergic synaptic transmission in region CA3 of the hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:1349–1356. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan JJ, Morris RGM. The cholinergic hypothesis of memory: A review of animal experiments. In: Iverson LL, et al., editors. Psychopharmacology of the Aging Nervous System, Handbook of of Psychopharmacology. Vol. 20. Plenum Press; New York: 1988. pp. 237–323. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo M, McGaughy J. High acetylcholine levels set circuit dynamics for attention and encoding and low acetylcholine levels set dynamics for consolidation. Progress in Brain Research. 2004;145:207–231. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)45015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, Bodelon C, Wyble BP. A proposed function for hippocampal theta rhythm: separate phases of encoding and retrieval enhance reversal of prior learning. Neural Comput. 2002;14:793–817. doi: 10.1162/089976602317318965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, Bower JM. Cholinergic suppression specific to intrinsic not afferent fiber synapses in rat piriform (olfactory) cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1992;67:1222–1229. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.5.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, Bower JM. Acetylcholine and memory. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:218–222. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90159-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, Fehlau BP. Differences in time course of ACh and GABA modulation of excitatory synaptic potentials in slices of rat hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:1792–1802. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.4.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, Schnell E. Laminar selectivity of the cholinergic suppression of synaptic transmission in rat hippocampal region CA1: computational modeling and brain slice physiology. J Neurosci. 1994;14:3898–3914. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-06-03898.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, Schnell E, Barkai E. Dynamics of learning and recall at excitatory recurrent synapses and cholinergic modulation in rat hippocampal region CA3. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5249–5262. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-05249.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, Wyble BP. Free recall and recognition in a network model of the hippocampus: simulating effects of scopolamine on human memory function. Behav Brain Res. 1997;89:1–34. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, Wyble BP, Wallenstein GV. Encoding and retrieval of episodic memories: role of cholinergic and GABAergic modulation in the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 1996;6:693–708. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:6<693::AID-HIPO12>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hounsgaard J. Inhibition produced by iontophoretically applied acetylcholine in area CA1 of thin hippocampal slices from the rat. Acta Physiol Scand. 1978a;103:110–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1978.tb06197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hounsgaard J. Presynaptic inhibitory action of acetylcholine in area CA1 of the hippocampus. Exp Neurol. 1978b;62:787–797. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(78)90284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janisiewicz AM, Jackson O, 3rd, Firoz EF, Baxter MG. Environment-spatial conditional learning in rats with selective lesions of medial septal cholinergic neurons. Hippocampus. 2004;14:265–273. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, Miledi R. The binding of acetylcholine to receptors and its removal from the synaptic cleft. J Physiol. 1973;231:549–574. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura F, Baughman RW. Distinct muscarinic receptor subtypes suppress excitatory and inhibitory synaptic responses in cortical neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:709–716. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.2.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopelman MD. The cholinergic neurotransmitter system in human memory and dementia: a review. Q J Exp Psychol A. 1986;38:535–573. doi: 10.1080/14640748608401614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosub KA, Derrick BE. Modulation of intrinsic hippocampal CA3 - CA3 synaptic responses by novelty and theta rhythm. Society for Neuroscience 2003 Abstract Viewer/Itinerary Planner. 2003 Program No. 289. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Kremin T, Gerber D, Giocomo LM, Huang SY, Tonegawa S, Hasselmo ME. Muscarinic suppression in stratum radiatum of CA1 shows dependence on presynaptic M1 receptors and is not dependent on effects at GABA(B) receptors. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2006;85:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremin T, Hasselmo ME. Cholinergic suppression of synaptic transmission in region CA3 of the rat hippocampal formation shows laminar selectivity. Society for Neuroscience 2003 Abstract Viewer/Itinerary Planner. 2003 Program No. 474. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Levey AI. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor expression in memory circuits: implications for treatment of Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:13541–13546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy WB. A sequence predicting CA3 is a flexible associator that learns and uses context to solve hippocampal-like tasks. Hippocampus. 1996;6:579–590. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:6<579::AID-HIPO3>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino MJ, Rouse ST, Levey AI, Potter LT, Conn PJ. Activation of the genetically defined m1 muscarinic receptor potentiates N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor currents in hippocampal pyramidal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:11465–11470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Segal M. The inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate pathway mediates cholinergic potentiation of rat hippocampal neuronal responses to NMDA. J Physiol. 1992;447:513–533. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuiston AR, Madison DV. Muscarinic receptor activity has multiple effects on the resting membrane potentials of CA1 hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5693–5702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05693.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa K, Sun LD, Quirk MC, Rondi-Reig L, Wilson MA, Tonegawa S. Hippocampal CA3 NMDA receptors are crucial for memory acquisition of one-time experience. Neuron. 2003;38:305–315. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natsume K, Kometani K. Theta-activity-dependent and -independent muscarinic facilitation of long-term potentiation in guinea pig hippocampal slices. Neurosci Res. 1997;27:335–341. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(97)01167-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil MM, Hasselmo ME. Modulation of inhibitory synaptic potentials in the piriform cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:2103–2118. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.5.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil MM, Linster C, Lubenov E, Hasselmo ME. Cholinergic agonist carbachol enables associative long-term potentiation in piriform cortex slices. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:2467–2474. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.5.2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC. Scopolamine induced learning failures in man. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1977;52:283–289. doi: 10.1007/BF00426713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmusson DD. The role of acetylcholine in cortical synaptic plasticity. Behav Brain Res. 2000;115:205–218. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JL, Kesner RP. Cholinergic modulation of the hippocampus during encoding and retrieval. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2003;80:332–342. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7427(03)00063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romo-Parra H, Vivar C, Maqueda J, Morales MA, Gutierrez R. Activity-dependent induction of multitransmitter signaling onto pyramidal cells and interneurons of hippocampal area CA3. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:3155–3167. doi: 10.1152/jn.00985.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan RD, Sutor B. Presynaptic M1 muscarinic cholinoceptors mediate inhibition of excitatory synaptic transmission in the hippocampus in vitro. Neurosci Lett. 1990;108:273–278. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90653-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffenach HA, Sloviter RS, Moser EI, Moser MB. Impaired retention of spatial memory after transection of longitudinally oriented axons of hippocampal CA3 pyramidal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3194–3198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042700999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbriaco D, Garcia S, Beaulieu C, Descarries L. Relational features of acetylcholine, noradrenaline, serotonin and GABA axon terminals in the stratum radiatum of adult rat hippocampus (CA1) Hippocampus. 1995;5:605–620. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450050611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Dingledine R. Presynaptic inhibitory effect of acetylcholine in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1981;1:784–792. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-07-00784.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt KE, Regehr WG. Cholinergic modulation of excitatory synaptic transmission in the CA3 area of the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:75–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00075.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuckovich JA, Semel ME, Baxter MG. Extensive lesions of cholinergic basal forebrain neurons do not impair spatial working memory. Learn Mem. 2004;11:87–94. doi: 10.1101/lm.63504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whishaw IQ. Dissociating performance and learning deficits on spatial navigation tasks in rats subjected to cholinergic muscarinic blockade. Brain Res Bull. 1989;23:347–358. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(89)90221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS. Calcium- and activity-dependent synaptic plasticity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:305–313. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80045-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]