Abstract

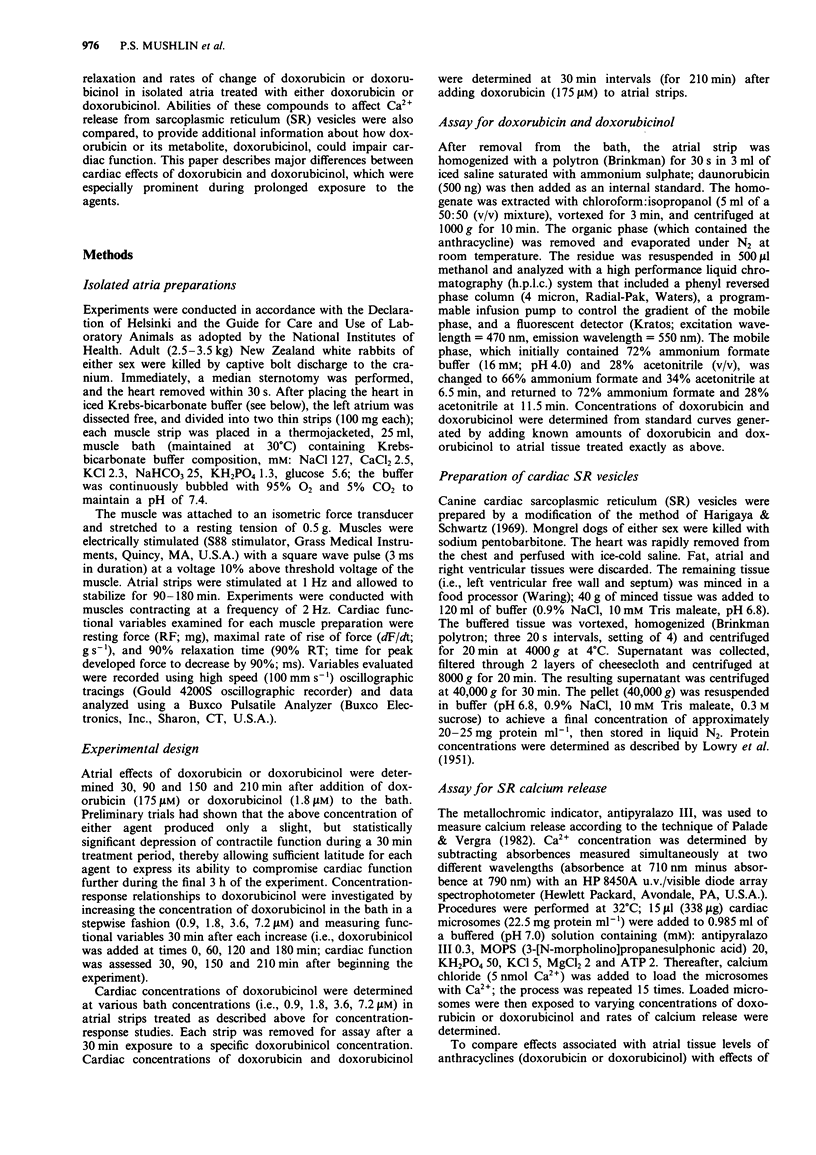

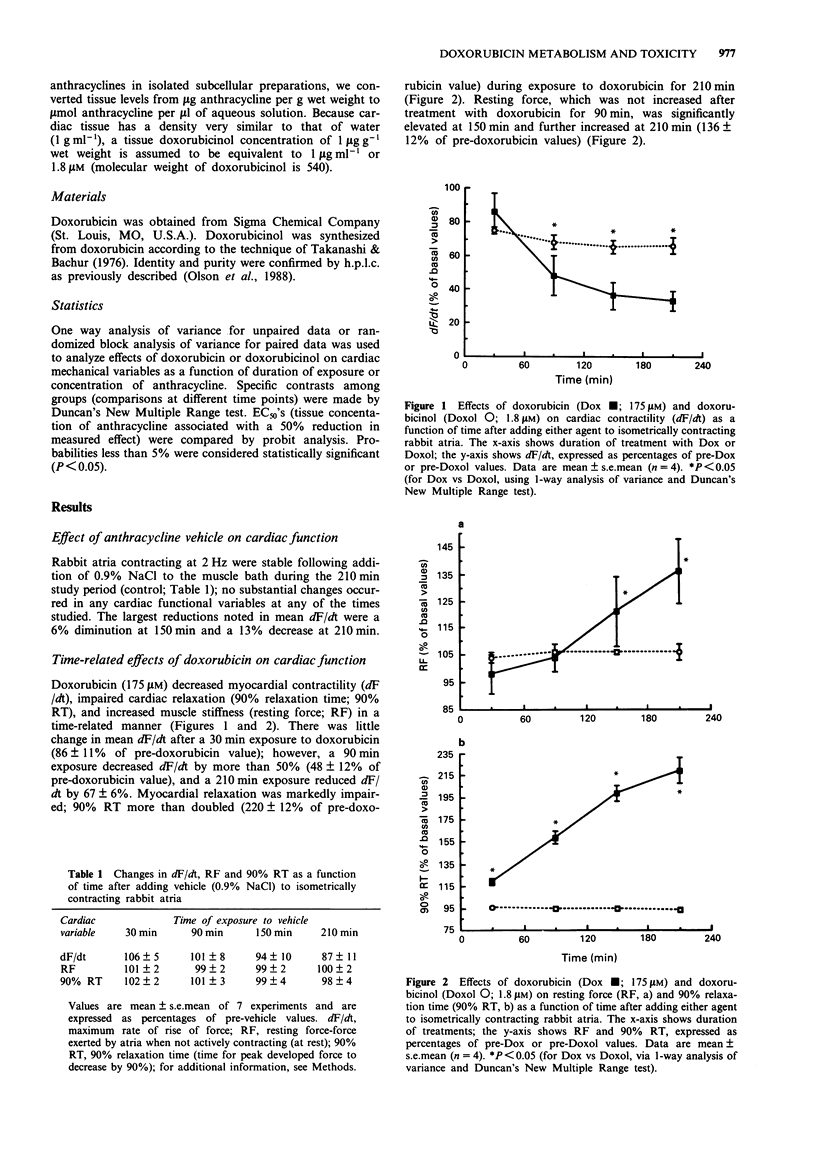

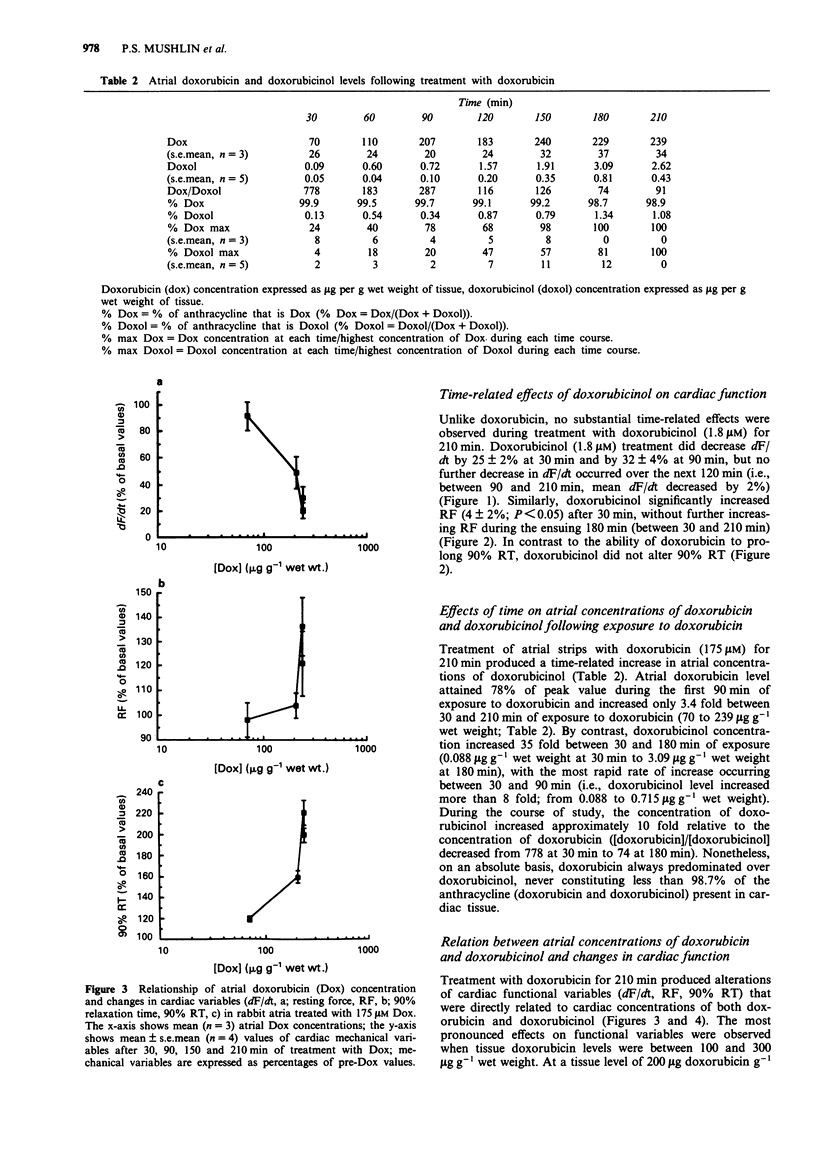

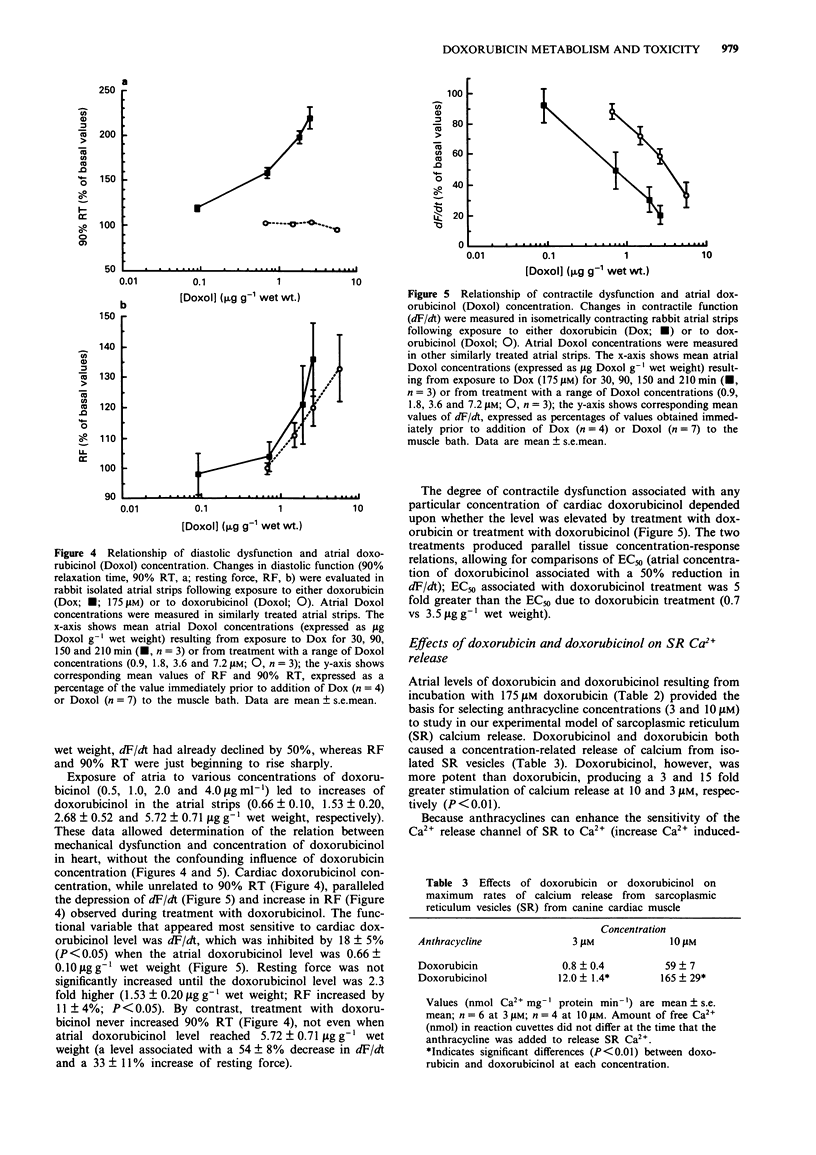

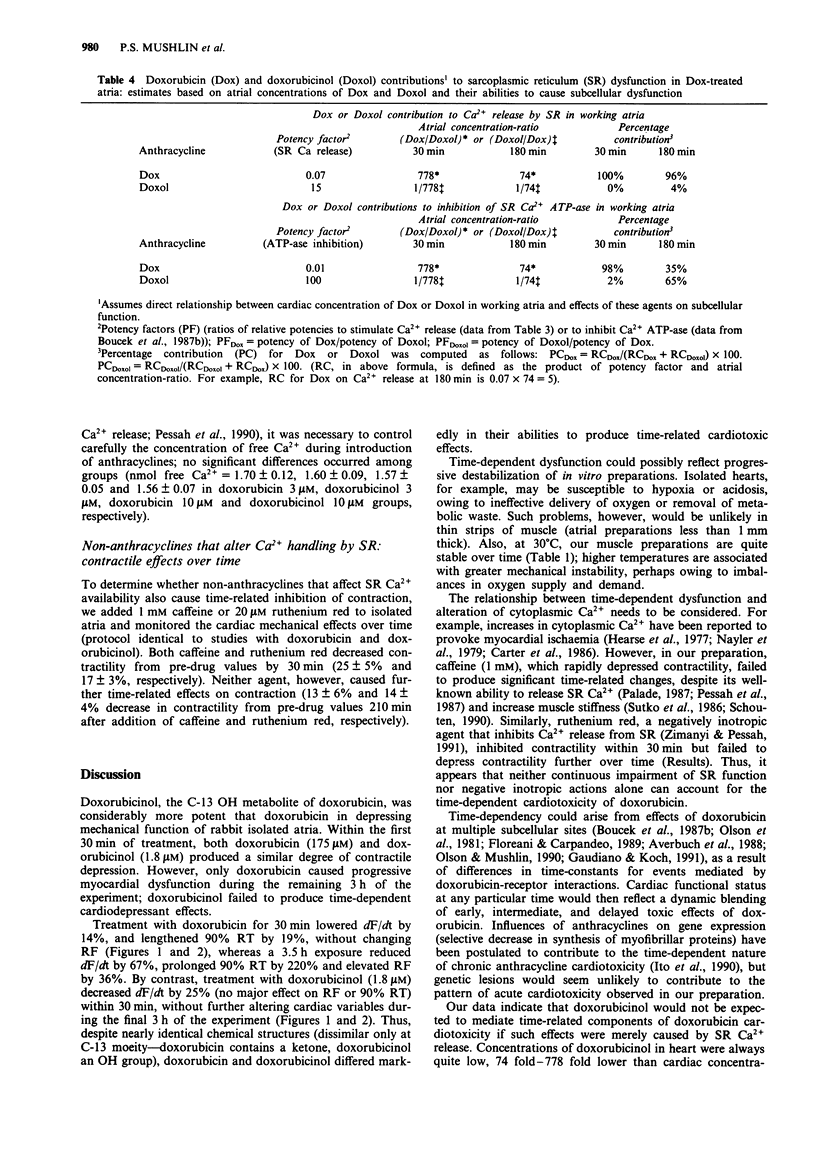

1. The present study evaluated the time-dependency of acute anthracycline cardiotoxicity by varying the duration of exposure of rabbit isolated atria to doxorubicin and determining changes (1) in contraction and relaxation and (2) in atrial concentrations of doxorubicin and its C-13 hydroxy metabolite, doxorubicinol. 2. Following addition of doxorubicin (175 microM) to atria, contractility (dF/dt), muscle stiffness (resting force, RF) and relaxation (90% relaxation time, 90% RT) were monitored for a 3.5 h period. 3. Doxorubicin (175 microM) progressively diminished mechanical function (decreased dF/dt, increased RF and prolonged 90% RT) over 3 h. Doxorubicinol (1.8 microM), however, failed to produce time-related cardiac dysfunction; it depressed contractile function and increased muscle stiffness during the first 30 min without causing additional cardiac dysfunction during the remaining 3 h of observation. Doxorubicinol had no effect on 90% RT. 4. During treatment with doxorubicin, atria contained considerably more doxorubicin than doxorubicinol (ratio of doxorubicin to doxorubicinol ranged from 778 to 74 at 0.5 and 3 h, respectively). Elevations of doxorubicin and doxorubicinol in atria paralleled the degree of dysfunction of both contraction and relaxation; increases in muscle stiffness, however, were more closely associated with increases of doxorubicinol than doxorubicin. 5. To probe the relation between cardiac doxorubicinol and myocardial dysfunction further, without confounding effects of cardiac doxorubicin, concentration-response experiments with doxorubicinol (0.9-7.2 microM) were conducted. 6. Plots of doxorubicinol concentrations in atria vs contractility indicated that the cardiac concentration of doxorubicinol, at which contractility is reduced by 50%, is five fold lower in doxorubicin-treated than in doxorubicinol-treated preparations.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 250 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Averbuch S. D., Boldt M., Gaudiano G., Stern J. B., Koch T. H., Bachur N. R. Experimental chemotherapy-induced skin necrosis in swine. Mechanistic studies of anthracycline antibiotic toxicity and protection with a radical dimer compound. J Clin Invest. 1988 Jan;81(1):142–148. doi: 10.1172/JCI113285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucek R. J., Jr, Olson R. D., Brenner D. E., Ogunbunmi E. M., Inui M., Fleischer S. The major metabolite of doxorubicin is a potent inhibitor of membrane-associated ion pumps. A correlative study of cardiac muscle with isolated membrane fractions. J Biol Chem. 1987 Nov 25;262(33):15851–15856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter J. E., Palacios I., Frist W. H., Rosenthal S., Newell J. B., Powell W. J., Jr Improvement in relaxation by nifedipine in hypoxic isometric cat papillary muscle. Am J Physiol. 1986 Feb;250(2 Pt 2):H208–H212. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.250.2.H208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floreani M., Carpenedo F. Inhibition of cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase activity by menadione. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1989 Apr;270(1):33–41. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudiano G., Koch T. H. Redox chemistry of anthracycline antitumor drugs and use of captodative radicals as tools for its elucidation and control. Chem Res Toxicol. 1991 Jan-Feb;4(1):2–16. doi: 10.1021/tx00019a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagane K., Akera T., Berlin J. R. Doxorubicin: mechanism of cardiodepressant actions in guinea pigs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988 Aug;246(2):655–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada H., Cusack B. J., Olson R. D., Stroo W., Azuma J., Hamaguchi T., Schaffer S. W. Taurine deficiency and doxorubicin: interaction with the cardiac sarcolemmal calcium pump. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990 Feb 15;39(4):745–751. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90154-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harigaya S., Schwartz A. Rate of calcium binding and uptake in normal animal and failing human cardiac muscle. Membrane vesicles (relaxing system) and mitochondria. Circ Res. 1969 Dec;25(6):781–794. doi: 10.1161/01.res.25.6.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearse D. J., Garlick P. B., Humphrey S. M. Ischemic contracture of the myocardium: mechanisms and prevention. Am J Cardiol. 1977 Jun;39(7):986–993. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(77)80212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H., Miller S. C., Billingham M. E., Akimoto H., Torti S. V., Wade R., Gahlmann R., Lyons G., Kedes L., Torti F. M. Doxorubicin selectively inhibits muscle gene expression in cardiac muscle cells in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Jun;87(11):4275–4279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O. H., ROSEBROUGH N. J., FARR A. L., RANDALL R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa N., Kanaide H., Meno H., Nakamura M. Adriamycin and altered membrane functions in rat hearts. Br J Exp Pathol. 1986 Oct;67(5):747–755. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayler W. G., Poole-Wilson P. A., Williams A. Hypoxia and calcium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1979 Jul;11(7):683–706. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(79)90381-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson R. D., Boerth R. C., Gerber J. G., Nies A. S. Mechanism of adriamycin cardiotoxicity: evidence for oxidative stress. Life Sci. 1981 Oct 5;29(14):1393–1401. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson R. D., Mushlin P. S., Brenner D. E., Fleischer S., Cusack B. J., Chang B. K., Boucek R. J., Jr Doxorubicin cardiotoxicity may be caused by its metabolite, doxorubicinol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 May;85(10):3585–3589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.10.3585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson R. D., Mushlin P. S. Doxorubicin cardiotoxicity: analysis of prevailing hypotheses. FASEB J. 1990 Oct;4(13):3076–3086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palade P. Drug-induced Ca2+ release from isolated sarcoplasmic reticulum. I. Use of pyrophosphate to study caffeine-induced Ca2+ release. J Biol Chem. 1987 May 5;262(13):6135–6141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palade P., Vergara J. Arsenazo III and antipyrylazo III calcium transients in single skeletal muscle fibers. J Gen Physiol. 1982 Apr;79(4):679–707. doi: 10.1085/jgp.79.4.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelikan P. C., Weisfeldt M. L., Jacobus W. E., Miceli M. V., Bulkley B. H., Gerstenblith G. Acute doxorubicin cardiotoxicity: functional, metabolic, and morphologic alterations in the isolated, perfused rat heart. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1986 Sep-Oct;8(5):1058–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessah I. N., Durie E. L., Schiedt M. J., Zimanyi I. Anthraquinone-sensitized Ca2+ release channel from rat cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum: possible receptor-mediated mechanism of doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. Mol Pharmacol. 1990 Apr;37(4):503–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessah I. N., Stambuk R. A., Casida J. E. Ca2+-activated ryanodine binding: mechanisms of sensitivity and intensity modulation by Mg2+, caffeine, and adenine nucleotides. Mol Pharmacol. 1987 Mar;31(3):232–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schouten V. J. Interval dependence of force and twitch duration in rat heart explained by Ca2+ pump inactivation in sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Physiol. 1990 Dec;431:427–444. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutko J. L., Thompson L. J., Kort A. A., Lakatta E. G. Comparison of effects of ryanodine and caffeine on rat ventricular myocardium. Am J Physiol. 1986 May;250(5 Pt 2):H786–H795. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.250.5.H786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takanashi S., Bachur N. R. Adriamycin metabolism in man. Evidence from urinary metabolites. Drug Metab Dispos. 1976 Jan-Feb;4(1):79–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimányi I., Pessah I. N. Comparison of [3H]ryanodine receptors and Ca++ release from rat cardiac and rabbit skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991 Mar;256(3):938–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]