Abstract

This critical care perspective appraises reprogramming of gene expression in inflammatory diseases as an emerging concept of clinical importance. We emphasize gene reprogramming that “silences” acute proinflammatory genes during severe systemic inflammation, wherein in the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) exists as a continuum during severe sepsis, septic shock, and the multiorgan dysfunction and failure phenotypes without infection. In contrast, silencing of acute proinflammatory genes is not apparent in sites of localized inflammatory processes like rheumatoid arthritis. We discuss in three parts the clinical context and the translational basic science associated with gene silencing during the SIRS continuum of severe systemic inflammation: (1) reprogramming of acute proinflammatory genes; (2) a “nuclear factor-κB paradox,” coupled with RelB expression, that combine to silence genes using an epigenetic (inherited and reversible) signature on the nucleosome; and (3) the potential clinical importance of compartmentalization in gene silencing. Our emergent understanding of these physiologic processes may provide a novel framework for developing treatments.

Keywords: compartmentalization, epigenetic, gene silencing, reprogramming

The late Lewis Thomas, in his essay on germs, presciently and eloquently described in 1974 the host response to bacterial endotoxins, which we now recognize as the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), with infection (sepsis, severe sepsis septic shock) or without infection (e.g., after severe trauma and acute pancreatitis) (1). Thomas stated,

It is the information carried by germs that we cannot abide. Macromolecules are read by our tissues as the very worst of bad news. We are likely to turn on every defense at our disposal; we will bomb, defoliate, blockade, seal off, and destroy all the tissues of the area. It is a shambles.

Both good- and bad-news stories developed after Thomas's masterful description of the “information carried by germs,” as the role of innate immunity in inflammation emerged. It was good news when cytokines were identified as essential mediators that induce SIRS (2). It was bad news when anticytokine therapies invariably failed to “correct” human SIRS associated with severe sepsis or septic shock, although this strategy “prevented” the syndrome in animals (3). In contrast, good-news stories developed when anticytokine therapy was used to treat rheumatoid arthritis and other local inflammatory processes, and a Lasker Award for these accomplishments was bestowed on Mark Feldmann and Ravinder Maini in 2003 (4).

What accounts for differences responsible for the distinct outcomes observed after treating rheumatoid arthritis versus SIRS associated with severe sepsis or septic shock with anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α/anticytokine therapy? While recognizing the complexity of host response both by the organ and distribution of cell types, we advocate that insight is provided by the following clinically applicable concepts of gene reprogramming: (1) silencing of acute proinflammatory genes, (2) an “NF [nuclear factor]-κB paradox” coupled with increased avian reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene related B (RelB) expression that combine to silence genes using an epigenetic (inheritable and reversible) signature on the nucleosome, and (3) compartmentalization of gene reprogramming during inflammation. The paradigm of gene silencing that is emphasized in this Perspective is embedded in a larger framework of gene reprogramming, which is emerging as critically important in generating the “functional” and clinically relevant phenotypes of inflammatory diseases. We will refer to the clinical state of SIRS associated with sepsis or septic shock as severe systemic inflammation.

Some of the results discussed in this Perspective have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (33).

SILENCING OF ACUTE PROINFLAMMATORY GENES OCCURS DURING SEVERE SYSTEMIC INFLAMMATION

The paradigm of gene silencing was first identified in the 1940s by the late Paul Beeson as a feature of “endotoxin tolerance” (5). Although endotoxin tolerance is the classic model for investigating gene silencing in animal and cell models, the term is complex, restrictive, and should be dropped in the context of its application to animal and human severe systemic inflammation in favor of the more appropriate concept of gene reprogramming to a silent phenotype.

Gene reprogramming that generates silencing of acute proinflammatory genes is typified by repression of mediators that initiate both systemic and local acute inflammation (6). These include TNF-α, IL-1β, chemokines, and chemotaxins. The gene silencing phase, when it occurs, may develop rapidly (3–5 h) after an initial activation phase that generates the “cytokine storm” (7, 8). The two-phase signature of induction followed by repression is common to animal (9) and human severe systemic inflammation with infection (10), and occurs variably in noninfectious clinical states of severe systemic inflammation, such as severe blunt trauma, hemorrhagic shock, and acute pancreatitis (11). Sustained silencing of acute proinflammatory genes is observed in blood neutrophils (12) and monocytes (13) during severe systemic inflammation in animals and humans, and can be faithfully modeled in cultures of human and animal cell lines and primary monocytes (14–16). Humans given intravenous endotoxin develop the silencing signature for a brief period (12–24 h) (8), but in severe systemic inflammation, the silencing of expression of acute proinflammatory genes can persist in blood leukocytes for many days or even weeks (12). This suggests that epigenetic events may contribute to gene silencing in leukocytes.

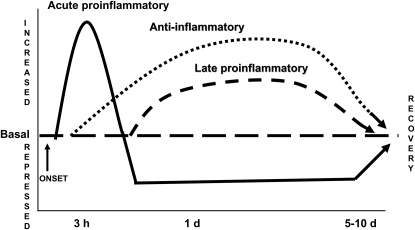

Figure 1 depicts a schematic of three functional and thus clinically relevant signatures of gene expression (changes in levels of mRNA and/or protein production or release), which are generated among a complexity of hundreds of genes whose expression is reprogrammed during severe systemic inflammation (17). In addition to the silencing signature (phase 2) that follows the induction of acute proinflammatory genes (phase 1), two other well-established and clinically important patterns are shown: sustained increases in expression of antiinflammatory gene products (e.g., IL-1 receptor antagonist [IL-1RA], TNF-α receptors 1 and 2, IL-6, the type II IL-1 receptor, and IL-10) and delayed and persistent expression of gene products with proinflammatory potential (e.g., high mobility group 1B [HMGB1] and macrophage inhibiting factor [MIF]). The second and third signatures of enhanced expression can be identified by increased levels of the mediators in plasma. They are not discussed in this Perspective on silencing but may participate in generating the compensatory antiinflammatory response syndrome with immunosuppression and in sustaining the course of inflammation, respectively (18).

Figure 1.

Reprogramming of expression of clinically important genes and gene products during inflammatory shock. This simplified scheme shows three functional and clinically significant gene expression patterns typical of inflammatory shock: (1) increased expression followed by sustained silencing of acute proinflammatory genes (solid line), such as IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α; (2) sustained increases in expression of antiinflammatory genes (dotted line), such as IL-1 receptor antagonist and IL-6; and (3) sustained increases in expression of “late” proinflammatory genes (dashed line), such as high mobility group 1B (HMGB1) and macrophage inhibiting factor (MIF). Changes in expression of many other genes or gene products (with increases or decreases) occur within or in addition to these signatures.

We found that repressed transcription (as opposed to other mechanisms [e.g., increased mRNA turnover] that may decrease gene expression) is a cellular mechanism responsible for the silencing of acute proinflammatory genes after the initiation of severe systemic inflammation (6). A recent report, which also analyzed gene expression by mRNA arrays at multiple times (up to 24 h) after intravenous administration of endotoxin to human volunteers, observed several hundred genes that fit the “up and then down” pattern typical of the silencing signature (19). Prominent examples of other classes of silenced genes that may be clinically relevant are those whose products are involved in protein synthesis or apoptosis (17, 19, 20).

The decreased expression of acute proinflammatory genes is clinically important, because it participates in generating sustained immunodepression and predicts increased mortality (21). Reprogramming of other genes also may influence clinical disease, as exemplified by increased and sustained expression of antiinflammatory gene products and the “late” proinflammatory mediators schematized in Figure 1 (22, 23). However, reprogramming of other distinct groups of genes that have not been definitively linked to clinical outcomes is not included in the simplified scheme.

The silencing of acute proinflammatory TNF-α and IL-1β is a plausible major contributor to the bad news of using anticytokine therapy in human sepsis. In those studies, the cytokine storm already occurred during the initial phase of SIRS, and thereafter the genes that encode these products likely were silenced. Not surprisingly, a further block was not clinically useful, and indeed could be detrimental (18). In contrast, a possible explanation for the good news of treating chronic local inflammatory processes such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel diseases with the anticytokine therapy is that the silencing of acute proinflammatory genes does not occur, thus allowing the activation phase reprogramming of acute proinflammatory genes to persist. This explanation is supported by the observations of persistently elevated cytokine levels of protein and mRNA (e.g., IL-1β and TNF-α) in rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of chronic local inflammation (24). This theory that silencing of acute proinflammatory genes may differ in sites of local inflammation introduces the potential clinical importance of the concept of compartmentalization of gene silencing during severe systemic inflammation, as discussed subsequently.

No clinically useful surrogate marker for silencing of acute proinflammatory genes yet exists. Also, the silencing phase of the first reprogramming signature depicted in Figure 1 is not readily apparent in investigations that are limited to measuring “snapshot” levels of mRNA or protein of acute proinflammatory genes, which usually are low during severe systemic inflammation. The silencing signature still must be identified by the inability of mRNA levels and protein production of a set of acute proinflammatory genes to increase in response to stimulation by bacterial endotoxin of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) (and likely ligands for other TLRs) (25, 26).

Another concept with potential clinical relevance is that the silencing of acute proinflammatory genes (as well as other signatures of gene reprogramming) subsides during clinical improvement, as depicted in Figure 1 (18). Thus, although the presence of the silencing signature connotes a poorer outcome, its reversal implies a good prognosis. Therefore, it is likely that the mechanisms responsible for regenerating the basal phenotype of gene expression are important in the clinical resolution of severe systemic inflammation. There are no reports to our knowledge that address these processes.

A NUCLEAR NF-κB PARADOX COUPLED WITH RelB EXPRESSION MAY COMBINE WITH AN EPIGENETIC SIGNATURE ON THE NUCLEOSOME TO SILENCE ACUTE PROINFLAMMATORY GENES

A nuclear NF-κB paradox occurs during severe systemic inflammation, as defined by a disassociation between cytosolic and nuclear NF-κB activation processes. Many studies of severe systemic inflammation associated with animal (27) or human sepsis (28) and investigations of cell models that simulate the sepsis phenotype (21, 29) have reported increased activation of NF-κB during sepsis. This interpretation is based on detecting elevated levels of NF-κB p65 transcription factor in the nucleus blood leukocytes or organ tissues, and/or by binding of NF-κB p65 to segments of cognate DNA, using electrophoretic mobility shift assay. These reports advocating NF-κB activation create a contradiction in terms, since the acute proinflammatory genes silenced during severe systemic inflammation are NF-κB dependent, requiring the formation of transcriptionally active NF-κB p65 and p50 heterodimers on gene enhancer/promoter DNA (30). NF-κB p65 binds and directly transactivates over 100 rapid response genes, including many of the acute proinflammatory class that initiate severe systemic inflammation and are then silenced (31).

To resolve this inconsistency of increased NF-κB p65 nuclear levels and silenced transcription of NF-κB–dependent genes that typify the phenotype of severe systemic inflammation, we analyzed NF-κB p65 and p50 binding in correlation with activation of the IL-1β promoter during the transcriptionally silent phase of signature 1, using in vivo assessment of the promoter by chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (32). Transcriptionally repressed leukocytes remain responsive to stimulation of TLR4 by endotoxin, as exemplified by degradation of cytosolic IκBα and nuclear translocation and accumulation of NF-κB p65 transcription factor. However, NF-κB p65 binding to promoter DNA was disrupted in the silenced phenotype, as investigated in the human promonocyte (THP-1) cell model (32), as well as in blood leukocytes obtained from humans with severe systemic inflammation (33). In contrast, promoter binding of NF-κB p50 occurred both in the basal state and during silencing, which is consistent with studies of the TNF-α promoter (30). These findings support reports that NF-κB p50 homodimers participate in silencing acute proinflammatory gene expression during gene silencing (16, 34).

Although providing a possible explanation for the NF-κB paradox of severe systemic inflammation and underscoring the importance of the nuclear phase of NF-κB–dependent events, the use of in vivo promoter analysis does not identify the precise mechanisms responsible for disrupting DNA binding of NF-κB p65 as a heterodimer with NF-κB p50. We have identified two possible contributors to this silencing process.

One contributing mechanism involves RelB. RelB, a member of the NF-κB family, first was characterized as a repressor of NF-κB (35), and later as a positive regulatory transcription factor that primarily heterodimerizes with NF-κB p100 or p52 (36). We discovered that increased RelB expression and its nuclear accumulation act as a negative feedback to repress transcription during gene silencing (37). RelB appears to both sequester nuclear NF-κB p65 (thus limiting its ability to bind and promote transcription) and to directly bind the IL-1β promoter. We also observed increased expression of RelB in “silenced” blood leukocytes obtained from humans with severe systemic inflammation (37). Our results support and extend earlier reports indicating that RelB can directly bind and compete with NF-κB p65 transactivation of TNF-α (38), as well as bind and repress the promoters of other acute proinflammatory genes (30, 39).

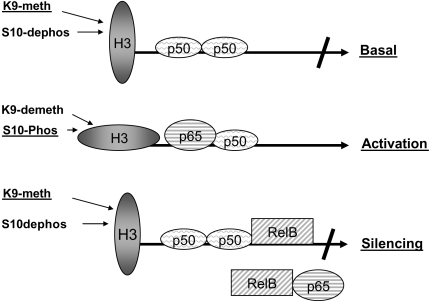

A second contributor is a chromatin-based mechanism characterized by disruption of the transcriptional “nucleosome shift” that occurs on histone 3 (H3), which is required for changing the repressed state of transcription to competent transactivation of acute proinflammatory genes like IL-1β and TNF-α (40). When the promoter of these genes is responsive, the basal, transcriptionally inactive state of nucleosomal chromatin, which is characterized by methylated H3 lysine 9 coupled with unphosphorylated H3 serine 10, “shifts” to the transcriptionally active state of demethylated H3 lysine 9 and phosphorylated H3 serine 10 (32). This shift cannot occur when acute proinflammatory genes are silenced, wherein the remethylation of H3 lysine 9 and dephosphorylation of H3 serine 10 persist (32). These data support that an epigenetic “imprint” may sustain silencing of acute proinflammatory genes in leukocytes during their increased production by bone marrow and rapid turnover in the circulation during severe systemic inflammation.

Promoter disruption as a mechanism for gene silencing during inflammatory shock is schematized in Figure 2. This model suggests that the NF-κB disruption of p65 binding that is coupled to increase expression of RelB and the epigenetic nucleosome signature of persistent H3 K9 methylation combine to silence acute proinflammatory genes. These events may not be mutually exclusive, and do not exclude the participation of other silencing events within cells. We also emphasize that cellular events that decrease positive signals or increase negative signals may also influence gene silencing (41).

Figure 2.

Nuclear mechanisms contributing to silencing of acute proinflammatory genes. The silenced phenotype for acute proinflammatory gene expression during inflammatory shock is associated with the following: (1) disrupted promoter assembly of nuclear factor (NF)-κB p65:p50 transcriptionally active heterodimers; (2) induction of an epigenetic “chromatin silencing mark” that involves sustained nucleosomal histone 3 (H3) lysine 9 methylation (K9-meth) and reduced H3 serine 10 phosphorylation (S10-Phos); and (3) increases in nuclear RelB, which limit NF-κB p65 transactivation by binding to NF-κB in nucleoplasm and/or through binding directly to promoter complexes of proteins and DNA. K9-demeth = H3 lysine 9 demethylation; S10-dephos = H3 serine 10 dephosphorylation.

COMPARTMENTALIZATION OF GENE SILENCING IN LUNG MAY EXIST DURING SEVERE SYSTEMIC INFLAMMATION WITH ACUTE LUNG INJURY/ADULT RESPIRATORY DISTRESS SYNDROME

The good-news story of effectiveness of anticytokine therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and other states of restrictive inflammation supports that compartmentalization that excludes gene silencing might be clinically important in severe systemic inflammation (4, 24). However, reports of compartmentalization of gene expression in severe systemic inflammation are limited. Investigations in animals support that the compartments of blood leukocytes, spleen, and liver display the common features of silencing of acute proinflammatory genes (21). The most extensive study of compartmentalization of acute proinflammatory gene silencing was reported by Fitting and associates during SIRS with sepsis or endotoxin shock in mice (42). Although the acute proinflammatory genes in cells and tissues of hematopoietic system of spleen, liver, bone marrow, and whole blood developed silencing, the inflamed lung did not display a robust silencing phase of signature 1.

Human studies of severe systemic inflammation with acute lung injury/adult respiratory distress syndrome (ALI/ARDS) support that the lung compartment may reprogram gene expression differently from that of blood, spleen, liver, or bone marrow (43). For example, acute proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, TNF-α) and chemokines (e.g., IL-8) remain constitutively elevated in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid obtained from humans with ALI/ARDS and severe systemic inflammation (44). Further evidence supporting compartmentalization of inflammation in human ALI/ARDS is the observation that gene expression profiles differ between circulating neutrophils and those that have migrated into the alveolar spaces (45). This observation is buttressed by a recent report in a rat model of sepsis that demonstrates the same paradigm (46). These studies suggest that the silencing phase of signature 1 may not occur in lung tissue external to the intravascular space. However, a recent report in a murine model of peritonitis-induced sepsis found the repressed phase of signature 1 in alveolar macrophages assessed for up to 24 hours after the onset of infection (47).

Study of NF-κB is another important method to investigate compartmentalization. NF-κB p65 protein levels are elevated in the lung during human ALI/ARDS (48), but no in vivo assessment of NF-κB p65 binding to the promoters of the acute proinflammatory genes has been reported, to our knowledge. Nevertheless, a recent report convincingly supports that NF-κB–dependent events in the lung may differ from those of blood compartments. A murine model was developed that generated ALI after sustained administration of endotoxin (49). Persistent transcriptional activation of NF-κB occurred, as determined by an NF-κB p65–dependent transfected reporter gene. In contrast, a single dose of endotoxin induced only transient activation of the NF-κB reporter gene. Sustained NF-κB transcription correlated with ALI, which was attenuated by an inhibitor of NF-κB activation. Clinical outcomes also were improved in animals treated with an NF-κB inhibitor after the initiation of the lung inflammation.

Taken together, these data support that NF-κB promoters may not be disrupted in this model of ALI, and that expression of acute proinflammatory genes persists. Thus, there are similar features between ALI/ARDS and the chronically inflamed joints of rheumatoid arthritis. The mechanisms responsible for compartmentalization are unknown, but suggest the local environment and the systemic environment may differentially influence gene silencing.

The concept of compartmentalized silencing of gene expression has potential clinical relevance. If the repressive phase of signature 1 of gene reprogramming does not occur in lung extravascular tissue during ALI/ARDS, localized therapies like those applied to rheumatoid arthritis might be specifically protective to lung, despite their failure when given systemically. A caveat to this concept is that the increased expression of antiinflammatory gene products in bronchoalveolar lavage may be immunosuppressive (50), and anticytokine or anti–NF-κB therapy might increase immunosuppression. However, systemic therapies that prevent or reverse gene silencing might generate good news.

CONCLUSIONS

Reprogramming of gene expression is an emerging concept with substantial clinical relevance. Reprogramming with silencing of transcription of acute proinflammatory genes may develop soon after the initiation of severe systemic inflammation, and its resolution correlates with clinical improvement. Such silencing of acute proinflammatory genes is not apparent in local inflammatory processes such as rheumatoid arthritis, providing a plausible explanation of the successes of anticytokine therapies in local inflammatory diseases and their failure in severe systemic inflammation. Nuclear processes of disruption of nuclear NF-κB p65 promoter binding and transactivating function coupled with induction of RelB and epigenetic imprint on nucleosomal histone may combine to silence gene promoters. The molecular mechanisms of silencing of acute proinflammatory genes may not be prominent in the extravascular compartment of lung when severe systemic inflammation is accompanied by ALI/ARDS.

These concepts should be further pursued for their potential to reveal new opportunities to translate basic biomedical science into improved therapies in critical care medicine.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sue Cousart, Karen Klein, Richard Loeser, and Linda McPhail for contributions to this manuscript.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants RO1AI-09169 (C.E.M.), RO1AI-065791 (C.E.M.), and MO-1RR 007122 to the Wake Forest University Medical Center General Clinical Research Center.

Conflict of Interest Statement: Neither author has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Thomas L. Lives of a cell, notes of a biology watcher. New York: Penguin Books; 1974. p. 78–79.

- 2.Tracey KJ, Lowry SF, Cerami A. The pathophysiologic role of cachectin/TNF in septic shock and cachexia. Ann Inst Pasteur Immunol 1988;139:311–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vincent JL, Abraham E. The last 100 years of sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:256–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldmann M, Maini RN. Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award: TNF defined as a therapeutic target for rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases. Nat Med 2003;9:1245–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beeson P. Tolerance to bacterial pyrogens. J Exp Med 1947;86:29–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoza BK, Hu JY, Cousart SL, McCall CE. Endotoxin inducible transcription is repressed in endotoxin tolerant cells. Shock 2000;13:236–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Granowitz EV, Porat R, Mier JW, Orencole SF, Kaplanski G, Lynch EA, Ye K, Vannier E, Wolff SM, Dinarello CA. Intravenous endotoxin suppresses the cytokine response of peripheral blood mononuclear cells of healthy humans. J Immunol 1993;151:1637–1645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Poll T, Coyle SM, Moldawer LL, Lowry SF. Changes in endotoxin-induced cytokine production by whole blood after in vivo exposure of normal humans to endotoxin. J Infect Dis 1996;174:1356–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathison JC, Virca GD, Wolfson E, Tobias PS, Glaser K, Ulevitch RJ. Adaptation to bacterial lipopolysaccharide controls lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor production in rabbit macrophages. J Clin Invest 1990;85:1108–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavaillon JM, Adib-Conquy M, Fitting C, Adrie C, Payen D. Cytokine cascade in sepsis. Scand J Infect Dis 2003;35:535–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarter MD, Mack VE, Daly JM, Naama HA, Calvano SE. Trauma-induced alterations in macrophage function. Surgery 1998;123:96–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCall CE, Grosso-Wilmoth LM, LaRue K, Guzman RN, Cousart SL. Tolerance to endotoxin-induced expression of the interleukin-1 beta gene in blood neutrophils of humans with the sepsis syndrome. J Clin Invest 1993;91:853–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munoz C, Misset B, Fitting C, Bleriot JP, Carlet J, Cavaillon JM. Dissociation between plasma and monocyte-associated cytokines during sepsis. Eur J Immunol 1991;21:2177–2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Virca GD, Kim SY, Glaser KB, Ulevitch RJ. Lipopolysaccharide induces hyporesponsiveness to its own action in RAW 264.7 cells. J Biol Chem 1989;264:21951–21956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LaRue KE, McCall CE. A labile transcriptional repressor modulates endotoxin tolerance. J Exp Med 1994;180:2269–2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ziegler-Heitbrock HW, Wedel A, Schraut W, Strobel M, Wendelgass P, Sternsdorf T, Bauerle PA, Haas JG, Riethmuller G. Tolerance to lipopolysaccharide involves mobilization of nuclear factor kappa B with predominance of p50 homodimers. J Biol Chem 1994;269:17001–17004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calvano SE, Xiao W, Richards DR, Felciano RM, Baker HV, Cho RJ, Chen RO, Brownstein BH, Cobb JP, Tschoeke SK, et al. A network-based analysis of systemic inflammation in humans. Nature 2005;437:1032–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med 2003;348:138–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Storey JD, Xiao W, Leek JT, Tompkins RG, Davis RW. Significance analysis of time course microarray experiments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:12837–12842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cobb JP, Mindrinos MN, Miller-Graziano C, Calvano SE, Baker HV, Xiao W, Laudanski K, Brownstein BH, Elson CM, Hayden DL, et al. Application of genome-wide expression analysis to human health and disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:4801–4806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.West MA, Heagy W. Endotoxin tolerance: a review. Crit Care Med 2002;30:S64–S73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang H, Yang H, Czura CJ, Sama AE, Tracey KJ. HMGB1 as a late mediator of lethal systemic inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:1768–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin TR. MIF mediation of sepsis. Nat Med 2000;6:140–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cope AP, Feldmann M. Emerging approaches for the therapy of autoimmune and chronic inflammatory disease. Curr Opin Immunol 2004;16:780–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cain BS, Tung TC. Endotoxin cross tolerance: another inflammatory preconditioning stimulus? Crit Care Med 2000;28:2164–2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacinto R, Hartung T, McCall C, Li L. Lipopolysaccharide- and lipoteichoic acid-induced tolerance and cross-tolerance: distinct alterations in IL-1 receptor-associated kinase. J Immunol 2002;168:6136–6141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bohrer H, Qiu F, Zimmermann T, Zhang Y, Jllmer T, Mannel D, Bottiger BW, Stern DM, Waldherr R, Saeger HD, et al. Role of NFkappaB in the mortality of sepsis. J Clin Invest 1997;100:972–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arnalich F, Garcia-Palomero E, Lopez J, Jimenez M, Madero R, Renart J, Vazquez JJ, Montiel C. Predictive value of nuclear factor kappaB activity and plasma cytokine levels in patients with sepsis. Infect Immun 2000;68:1942–1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fan H, Cook JA. Molecular mechanisms of endotoxin tolerance. J Endotoxin Res 2004;10:71–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schreiber J, Jenner RG, Murray HL, Gerber GK, Gifford DK, Young RA. Coordinated binding of NF-kappaB family members in the response of human cells to lipopolysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:5899–5904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jenner RG, Young RA. Insights into host responses against pathogens from transcriptional profiling. Nat Rev Microbiol 2005;3:281–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan C, Li L, McCall CE, Yoza BK. Endotoxin tolerance disrupts chromatin remodeling and NF-kappaB transactivation at the IL-1beta promoter. J Immunol 2005;175:461–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCall CE, Yoza BK. Episomal memory to silence gene expression during inflammatory shock. Functional Genomics of Critical Injury and Stress 2006;79:10–14. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bohuslav J, Kravchenko VV, Parry GC, Erlich JH, Gerondakis S, Mackman N, Ulevitch RJ. Regulation of an essential innate immune response by the p50 subunit of NF-kappaB. J Clin Invest 1998;102:1645–1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryseck RP, Bull P, Takamiya M, Bours V, Siebenlist U, Dobrzanski P, Bravo R. RelB, a new Rel family transcription activator that can interact with p50-NF-kappa B. Mol Cell Biol 1992;12:674–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bours V, Azarenko V, Dejardin E, Siebenlist U. Human RelB (I-Rel) functions as a kappa B site-dependent transactivating member of the family of Rel-related proteins. Oncogene 1994;9:1699–1702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoza BK, Hu JY, Cousart SL, Forrest LM, McCall CE. Induction of RelB participates in endotoxin tolerance. J Immunol 2006;177:4080–4085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marienfeld R, May MJ, Berberich I, Serfling E, Ghosh S, Neumann M. RelB forms transcriptionally inactive complexes with RelA/p65. J Biol Chem 2003;278:19852–19860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saccani S, Pantano S, Natoli G. Modulation of NF-kappaB activity by exchange of dimers. Mol Cell 2003;11:1563–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheung P, Allis CD, Sassone-Corsi P. Signaling to chromatin through histone modifications. Cell 2000;103:263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liew FY, Xu D, Brint EK, O'Neill LA. Negative regulation of Toll-like receptor-mediated immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 2005;5:446–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fitting C, Dhawan S, Cavaillon JM. Compartmentalization of tolerance to endotoxin. J Infect Dis 2004;189:1295–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matthay MA, Zimmerman GA. Acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome: four decades of inquiry into pathogenesis and rational management. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2005;33:319–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meduri GU, Kohler G, Headley S, Tolley E, Stentz F, Postlethwaite A. Inflammatory cytokines in the BAL of patients with ARDS: persistent elevation over time predicts poor outcome. Chest 1995;108:1303–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coldren CD, Nick JA, Poch KR, Woolum MD, Fouty BW, O'Brien JM, Gruber MP, Zamora MR, Svetkauskaite D, Richter DA, et al. Functional and genomic changes induced by alveolar transmigration in human neutrophils. Am J Physiol Lun Cell Mol Physiol 2006;291:1267–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo RF, Riedemann NC, Sun L, Gao H, Shi KX, Reuben JS, Sarma VJ, Zetoune FS, Ward PA. Divergent signaling pathways in phagocytic cells during sepsis. J Immunol 2006;177:1306–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deng JC, Cheng G, Newstead MW, Zeng X, Kobayashi K, Flavell RA, Standiford TJ. Sepsis-induced suppression of lung innate immunity is mediated by IRAK-M. J Clin Invest 2006;116:2532–2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abraham E. Nuclear factor-kappaB and its role in sepsis-associated organ failure. J Infect Dis 2003;187:S364–S369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Everhart MB, Han W, Sherrill TP, Arutiunov M, Polosukhin VV, Burke JR, Sadikot RT, Christman JW, Yull FE, Blackwell TS. Duration and intensity of NF-kappaB activity determine the severity of endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. J Immunol 2006;176:4995–5005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park WY, Goodman RB, Steinberg KP, Ruzinski JT, Radella F, Park DR, Pugin J, Skerrett SJ, Hudson LD, Martin TR. Cytokine balance in the lungs of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:1896–1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]