Abstract

Ethanol’s effects on the developing brain include alterations in morphological and biochemistry of the hypothalamus. In order to examine the potential functional consequences of ethanol’s interference with hypothalamic differentiation, we studied the long-term effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on basal circadian rhythms of core body temperature (CBT) and heart rate (HR). We also examined the late afternoon surge in corticosterone (CORT). CBT and HR rhythms were studied in separate groups of animals at 4 months, 8 months and 20 months of age. The normal late-afternoon rise in plasma corticosterone was examined in freely-moving male rats at 6 months of age via an indwelling right-atrial cannula. Results showed that the CBT circadian rhythm exhibited an earlier rise following the nadir of the rhythm in fetal alcohol exposed (FAE) males at all ages compared to controls. At 8 months of age, the amplitude of the CBT circadian rhythm in FAE males was significantly reduced to the level observed in controls at 20 months. No significant effects of prenatal ethanol exposure were observed on basal HR rhythm at any age. The diurnal rise in corticosterone secretion was blunted and prolonged in 6-month-old FAE males compared to controls. Both control groups exhibited a robust surge in corticosterone secretion around the onset of the dark phase of the light cycle, which peaked at 1930 hours. Instead, FAE males exhibited a linear rise beginning in mid afternoon, which peaked at 2130 hours. These results indicate that exposure to ethanol during the period of hypothalamic development can alter the long-term regulation of circadian rhythms in specific physiological systems.

Keywords: prenatal, alcohol, suprachiasmatic nucleus, SCN, circadian, rats, heart rate, core body temperature, corticosterone, aging, male

INTRODUCTION

In addition to well-established effects on cognitive and physical development, in utero, ethanol exposure induces long-term alterations in the regulation of autonomic and endocrine responses integrated by the hypothalamus in animals and humans (Abel, 1984, Hellstrom et al., 1996, Lee et al., 2000, Schneider et al., 2004, Suess et al., 1997, Weinberg, 1994). As the major output area from the limbic system, the hypothalamus integrates metabolism, temperature regulation, autonomic function, circadian rhythms, and motivated behaviors to insure biochemical, physiological, and behavioral homeostasis (Card et al., 1999, Morgane and Panksepp, 1980).

Adult rats exposed to ethanol during the last week of gestation, which is the period of hypothalamic differentiation, show disruptions of several physiological and behavioral systems under hypothalamic control. Among these are an impairment of growth hormone, LH and FSH release, increased stress-induced release of glucocorticoids, decreases in thyroxine, reduced prenatal and postnatal surge of testosterone, poor thermoregulation and shorter reproductive life spans in females. (Blaine et al., 1999, Handa et al., 1985, Lee et al., 2000, McGivern et al., 1988, 1993, 1995; Scott et al., 1998, Taylor et al., 1982a, Weinberg et al., 1996, Wilcoxon and Redei, 2004, Zimmerberg et al., 1993). Disruptions in behaviors regulated by the hypothalamus are also observed in FAE (Fetal Alcohol Exposed) animals, including decreased maternal behavior in females, decreased reproductive behavior in males, feminization of taste preferences in males and increased daily water consumption (Barron and Riley, 1985, Hard et al., 1984, McGivern et al., 1984, 1998). Neuroanatomically, the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the hypothalamus is reduced in FAE males (Barron et al., 1988, Rudeen et al., 1986), which likely stems from the reduced prenatal and postnatal surge of testosterone in these animals.

One aspect of hypothalamic function that has received little study in FAE animals is the regulation of circadian rhythms. In mammals, circadian rhythms are entrained by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus. Individual oscillators in the CNS regulating activity, temperature, and hormone secretion are not strictly tied to a 24-hour rhythm, nor are they inherently phase-locked (Moore et al., 2002). The SCN serves as a master clock by synchronizing individual oscillators (i.e., temperature, activity, heart rate) to a zeitgeiber such as light. This synchronization allows the organism to anticipate physiological and behavioral needs associated with circadian changes in environmental conditions, an essential component for survival and adaptation.

Because the rodent SCN develops primarily during fetal life, maternal influences such as poor nutrition, stress and drugs can interfere with normal development of the SCN function (Kennaway, 2002). For example, both prenatal stress and prenatal hypoxia during the last week of gestation significantly reduce the ability of animals to entrain to light as measured by daily rhythms in corticosterone or locomotor activity (Joseph et al., 2002, Koehl et al., 1997). Therefore, developmental damage to the SCN by prenatal ethanol exposure might be predicted. This is consistent with the report of reduced sensitivity in FAE males to phase shifting in response to light pulses (Sei et al., 2003). However, Taylor and co-workers (1982a) found that treating dams with alcohol during the last two weeks of gestation did not influence the age of onset for the circadian rhythm of corticosterone in the offspring.

Evidence for alcohol induced damage to the developing SCN was found by Rojas and coworkers (1999) who injected dams with ethanol on days 14–17 of gestation during the period when the neurons of the SCN are born. The authors observed significant morphological changes in VIP processes within the SCN at postnatal day 30 ethanol exposed offspring compared to controls. VIP is a major regulatory peptide within the SCN, which is involved in rhythm entrainment (van Esselveldt et al., 2000). Evidence for long-term ethanol damage to the developing SCN was observed by Chen et al., (2006) in adult male offspring exposed to ethanol during the prenatal developmental period (gestation days 10–21). Prenatal exposure to ethanol altered the diurnal expression of proopiomelanocortin mRNA in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus, as well as the rPER1 and rPER2 in the SCN. In another study from this laboratory, adult males exposed to the same prenatal alcohol regimen exhibited altered immune rhythms as well (Arjona et al., 2006)

Recent studies have also identified long-term effects of postnatal ethanol exposure on SCN morphology, behavior and gene expression in the rat. As adults, males administered ethanol between postnatal days 4 and 9 exhibited enhanced sensitivity to the phase shifting effects of a light pulse on the circadian locomotor rhythm, as well as a decrease in the circadian expression of the neurotrophin, BDNF, within the SCN (Allen et al. 2004, 2005a, 2005b, Farnell et al., 2004).

The present studies were undertaken to characterize the prenatal effects of ethanol on several physiological parameters that show basal rhythms in expression. These included core body temperature, heart rate and corticosterone secretion. On the basis of findings from several studies showing morphological, biochemical and molecular changes in the SCN of animals exposed prenatally to ethanol, we expected to see a dysregulation of these basal circadian rhythms in adult FAE males. Females exposed to ethanol become were not included for comparison because of the interaction between the estrous cycle and circadian rhythms for temperature and activity (Rusak & Zucker, 1979). Prenatal ethanol exposure markedly accelerates the ageing of the female reproductive system, resulting in a premature onset of anovulation between 6 and 12 months of age compared to PF and CF controls (McGivern et al., 1995).

Because developmental effects of drugs are sometimes unmasked by age (Sparber 1991), we also examined the rhythms of CBT and HR across age, in 4, 8, and 18–20 month old animals. The diurnal rise in corticosterone secretion, a rhythm which is entrained to the feeding schedule associated with the onset of the dark cycle (Homma et al., 1996, Pecoraro et al., 2002), was examined at 6 months of age. Finally, work from our laboratory showing alterations in behavior and physiology related to hypothalamic regulation has focused on ethanol’s effects on the developing hypothalamus. Toward that end, we have studied animals exposed to ethanol only during the period of hypothalamic differentiation, which is the third week of gestation in the rat. We have followed the same approach in this study of SCN related functions in FAE males.

METHODS

Subjects and Treatments

Thirty multiparous, time-pregnant, Sprague-Dawley dams (Harlan Laboratories, Inc. San Diego, CA.) arrived in the laboratory on day 6 of gestation. The animals were individually housed in shoebox cages in a separate room in a climate-controlled vivarium. Tap water and dry food pellets (Teklab) were available ad libitum. From days 14–20 of gestation, dams in the ethanol treatment group (N=12) were fed a nutrionally fortified liquid diet containing 35% ethanol-derived calories (FAE: Fetal Alcohol Exposed). Control dams were either pair-fed (PF) an isocaloric diet containing no ethanol (N=10), or continued on dry food pellets and tapwater (chow-fed; CF) (N = 8). Twenty four hours prior to parturition, diets were replaced with dry food pellets. The liquid diet regimen that we used is associated with ethanol intake of 11–13 g/day in the dams and peak BACs over 100 mg/dl (McGivern, et al., 1987).

The diet consisted of chocolate flavored Boost (Mead Johnson, Evansville, IN) supplemented with vitamins (Vitamin Diet Fortification Mixture; ICN Nutritional Biochemicals; 1.3 g/12 oz Boost) and salts (Salt Mixture IV; ICN Nutritional Biochemicals; 2.1 g/12 oz Boost). Pair-fed dams were administered the same diet with sucrose (8.4 g/12 oz Boost) isocalorically substituting for ethanol. The diets were made fresh daily and presented to the dams 2–3 hours prior to lights off. Pair-fed dams were given the same amount of diet as consumed by a weight matched ethanol-fed dam during the previous evening. Chow-fed dams had access to dry food pellets and water ad libitum throughout pregnancy. Nesting material was provided to all dams on day 18 of gestation.

Offspring were weighed, sexed and culled to five males and five female pups per litter within 12 hours of birth. Litter size at birth ranged from 5 to 16 animals. Litters that had less than 5 males or 5 females were brought to five of each sex using animals from other litters in the same treatment group with more than 10 pups. Weaning was performed on day 26, with all animals subsequently group housed by sex and treatment. Group housing was done so that animals from different litters within a treatment were housed together. All experiments were conducted with no more than 2 animals represented from any litter.

Cohorts of male rats at 4, 8, or 18 to 20 months of age, were examined for heart rate and core body temperature rhythms. At 6 months of age, another cohort of males was used to study the late afternoon rise in corticosterone. Animals used in all experiments were naïve. During the entire length of this study, the group-housed animals were maintained under a 12:12 light/dark schedule with food and water available ad libitum. Ambient light in the vivarium during the light phase was approximately 200 Lux. All animal procedures were previously approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at San Diego State University.

Procedures: Core Body Temperature and Heart Rate Rhythms

Basal core body temperature and heart rate exhibit significant circadian rhythms that are independent of environmental changes in physical activity or stress (Elliott, 1983). We studied these rhythms in individually housed animals using a data collection system (Vital View Data Acquisition Software) and equipment purchased from Minimitter Co. (Bend, OR). Studies were conducted in vivarium rooms used solely for this purpose, and experimentally naïve cohorts of animals were used at each age.

To measure heart rate (HR) and core body temperature (CBT) rhythms, each animal was surgically implanted in the intraperitoneal cavity with a passive transmitter, two weeks prior to the measurement period according to the manufacturer’s protocol, which follows the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.. Surgical procedures were performed under ketamine (100mg.kg)/xylazine (20 mg/kg) anesthesia. Animals were monitored for recovery and returned to their home cage when they were ambulatory and feeding.

At the beginning of the study period, each animal was singly housed in a plastic shoebox cage beneath which was a receiver that transmitted CBT and heart rate data (MiniMitter, Co., Bend OR) to a computer in an adjacent room. Core Body Temperature was recorded every 3 minutes and heart rate every 15 seconds. Food and water were available ad libitum.

The study was conducted in replicates, with six to eight animals tested at a time. CF, PF and FAE animals were represented in each cohort. Lighting conditions were 12:12 light/dark, with lights on at 0600 hrs. To allow animals to acclimate to the cages, data collection was not begun until after three days after they were placed in the cage. Data from the following two days were used to measure circadian rhythms.

Plasma Corticosterone Rhythm

In the rat, plasma levels of corticosterone begin to increase several hours before the beginning of the dark phase of the circadian cycle, in anticipation of feeding. To study the effect of prenatal ethanol exposure on this rhythm, we took serial blood samples via a right-atrial catheter implanted into naïve 6 month old males.

Five days prior to blood sampling, while under ketamine/xylazine (100/20 mg/kg) anesthesia, right-atrial catheters were implanted through the right jugular vein of PF, CF and FAE rats, as we have described previously (Handa et al., 1985). For one week prior to surgery and thereafter, animals were individually housed in specially designed cages that allow remote blood sampling of blood from freely-moving animals. Under these conditions, the animals were acclimated to the individual housing conditions and unaware that a sample was being obtained. On the day of sampling, blood samples (20 μl) were obtained every two hours between 12:00 and 24:00 hrs. Replacement of blood volume was with heparinized (10 units/ml), normal saline. The lighting schedule was 12:12 LD, with lights on at 0600 hrs.

Corticosterone Radioimmunoassay

Corticosterone levels were measured by RIA as previously described (Handa et al., 1994). Briefly, an anti-corticosterone antiserum was purchased from ICN (Irvine, CA) and used at a dilution of 1:2000. A standard curve ranging from 2 to 1000 pg/tube was run alongside all unknown samples. Plasma was diluted 1:20 in 0.1M PBS (ph. 7.0) and was heated at 65C for 1 hr to destroy plasma binding proteins that could interfere with Ab binding. Sensitivity of this assay is 10 pg/tube. Inter-assay variation is 8.1%, intra-assay variation is 4.4%.

Data Analysis

Data for HR and CBT were averaged over two successive days, and collapsed into 15-minute periods. Data were analyzed by using a Treatment (FAE, PF, CF) X Period (48 blocks) ANOVA with repeated measures over the Period factor. Degrees of freedom were adjusted with a Huynh-Feldt correction to meet sphericity assumptions for the repeated measures factor. Orthogonal trend analyses were included to evaluate significant changes in the overall rhythm. Plasma corticosterone levels were analyzed using a Treatment (FAE, PF, CF) X Time (7 hourly measurements) ANOVA with repeated measures across time.

The amplitude of the CBT rhythm was analyzed by comparing the 15 minute averages of individual animals during the four successive 6-hour blocks that comprised the circadian data between 12 am and 12pm. These data were analyzed in a Treatment (FAE, PF, CF) X Age (4, 8, and 20 months) X Block (4 blocks: 12–6am, 6am–12pm, 12pm–6pm, 6pm–12am) ANOVA with repeated measures over the last factor. Post hoc analyses of comparing the treatment means within ages were conducted with Student t-tests using Bonferroni corrections for multiple groups.

At 18 months of age, the HR circadian rhythm amplitude normally exhibits a marked, age-related attenuation. To assess the impact of prenatal alcohol on this phenomenon, we conducted two separate analyses. In the first, we used a Treatment (FAE, PF, CF) X Period (48 blocks) ANOVA with repeated measure over the last factor, which included an orthogonal trend analysis. In the second, we analyzed each animal’s circadian HR data with an orthogonal trend analysis for the presence of a significant quartic component to establish the presence of a circadian rhythm. This allowed us to establish how many animals in each treatment group at this age still exhibited a detectable rhythm. Subsequent treatment comparisons regarding the statistical presence of a HR circadian rhythm were made using a Chi Square analysis.

RESULTS

All dams gave birth within 24 hours of each other. However, ethanol treated dams gave birth approximately 5–12 hours later than CF and PF dams. No differences were observed in litter size. Daily ethanol consumption in dams averaged 9.89 g/kg (±0.91 SEM) per day between day 14 and day 20 of gestation.

Core Body Temperature (CBT)

4 Months of Age

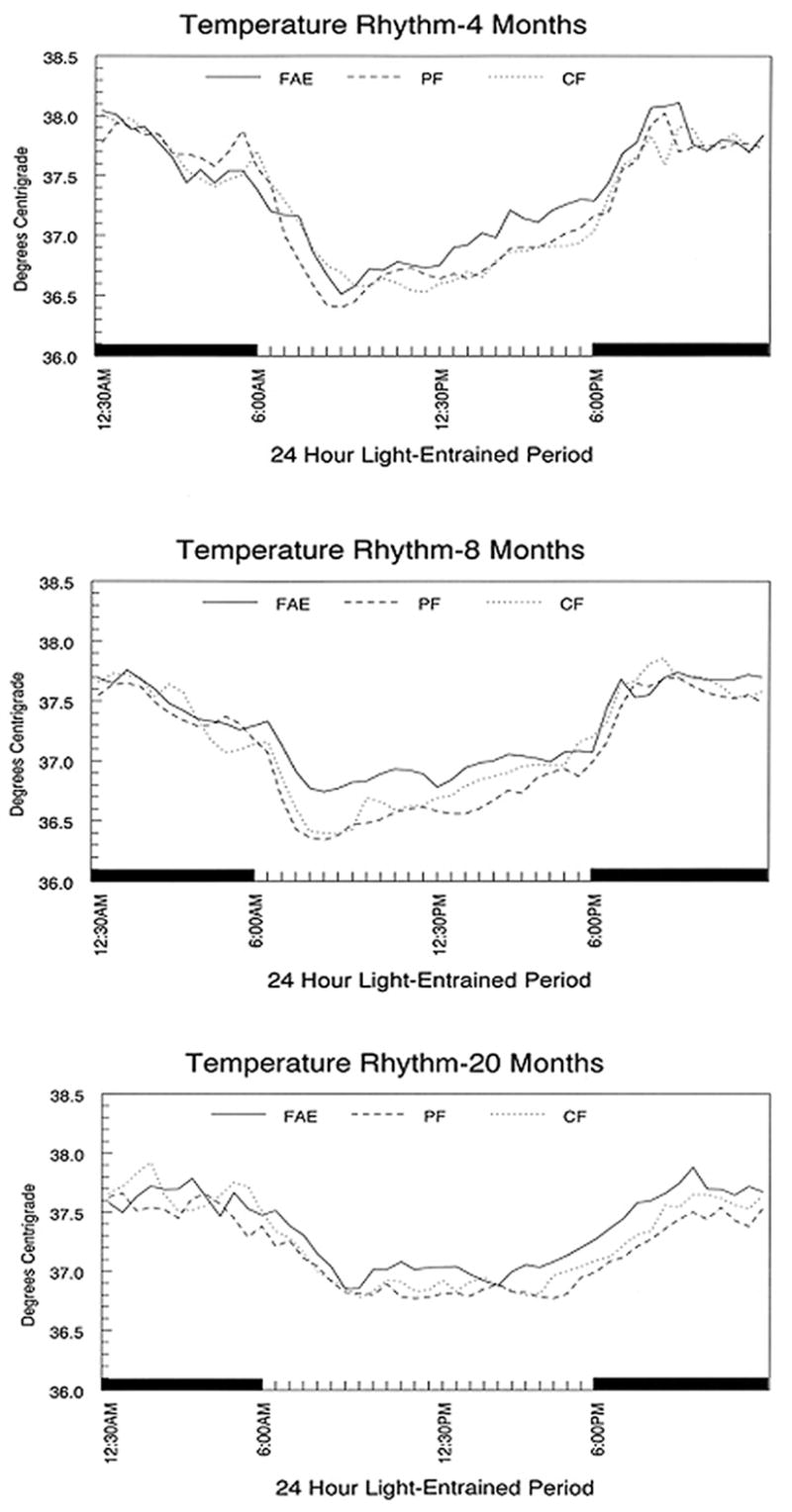

CBT was measured in 5 FAE, 5 PF, and 4 CF males using two cohorts of animals in which each treatment group was represented by animals from at least 2 different litters. Cohorts were run 10 days apart. The ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Period (F[47,517] = 86.20; p<0.0001) and a significant Treatment X Period interaction (F[94,517] = 1.71; p<0.005). As shown in Figure 1, FAE animals at this age exhibited a significantly sharper rise in CBT following the nadir than controls, which was reflected in a significant interaction effect between treatment and linearity in the orthogonal trend analysis (F[2,11] = 5.91; p<0.02).

Figure 1.

Core body temperature rhythm in male rats entrained to a 12:12 LD schedule. Data shown are the average of 30 minute bins over two successive days. Individual groups of rats were examined at each of the three ages. FAE = fetal alcohol exposed, PF= pair fed, CF = chow fed.

8 Months of Age

Measurements were made in 8 FAE, 8 CF and 8 PF males representing at least 4 litters per treatment group. The ANOVA revealed a significant main effect for Period (F[47,987] = 84.70; p<0.0001) as well as an interaction between Period and Treatment (F[94,987] = 1.69; p<0.01). As shown in Figure 1, there is a marked reduction in the temperature rhythm amplitude of FAE males at this age compared to CF and PF controls.

18 Months of Age

Measurements were made from 9 FAE, 8 PF and 6 CF males. The analysis revealed a significant main effect of period (F[47,940] = 32.22; p<0.0001). A subsequent analysis, that was limited to the rising phase of the rhythm (between 3 pm and 9 pm), revealed a significant effect for Period (F[9,153] = 3.03; p<0.01) and an interaction between Treatment and Period (F[18,153] = 2.11; p<0.02). As shown in Figure 1, FAE animals exhibited an earlier rise in temperature than PF and CF males in the late afternoon.

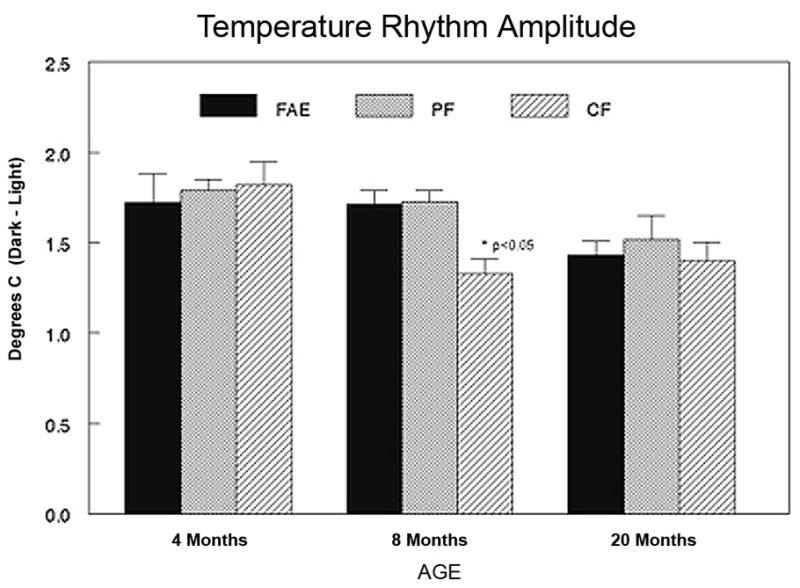

Core Body Temperature Rhythm Amplitude

The analysis of the 6 hour time blocks revealed a significant effect of Time (F[3,156] = 326.58; p<0.0001), as well as interactions between Age and Time (F[6,156] = 3.73; p<0.002). Rhythm amplitude decreased with aging, as shown in Figure 2. For purposes of depiction, the data are collapsed across the light and dark phases of the cycle and shown as difference scores. The linear decrease across age in CF and PF controls was not observed in FAE animals. Orthogonal decomposition revealed a significant interaction between Age and Treatment in the cubic trend over the Time factor (F[4,52] = 2.97; p<0.05). The rhythm amplitude at 8 months of age in FAE males was significantly smaller than PF or CF controls (P<0.05). Both control groups exhibited a decrease from 4 to 20 months that was equal to the decrease in amplitude observed between 4 and 8 months of age in FAE males.

Figure 2.

Amplitude of core body temperature rhythm across age. Each bar represents the mean +/− SEM of 4–6 animals. Data shown are difference in body temperature between the mean temperatures during the dark versus the light phase of the cycle. * = p<0.05 from both PF and CF controls at the same age.

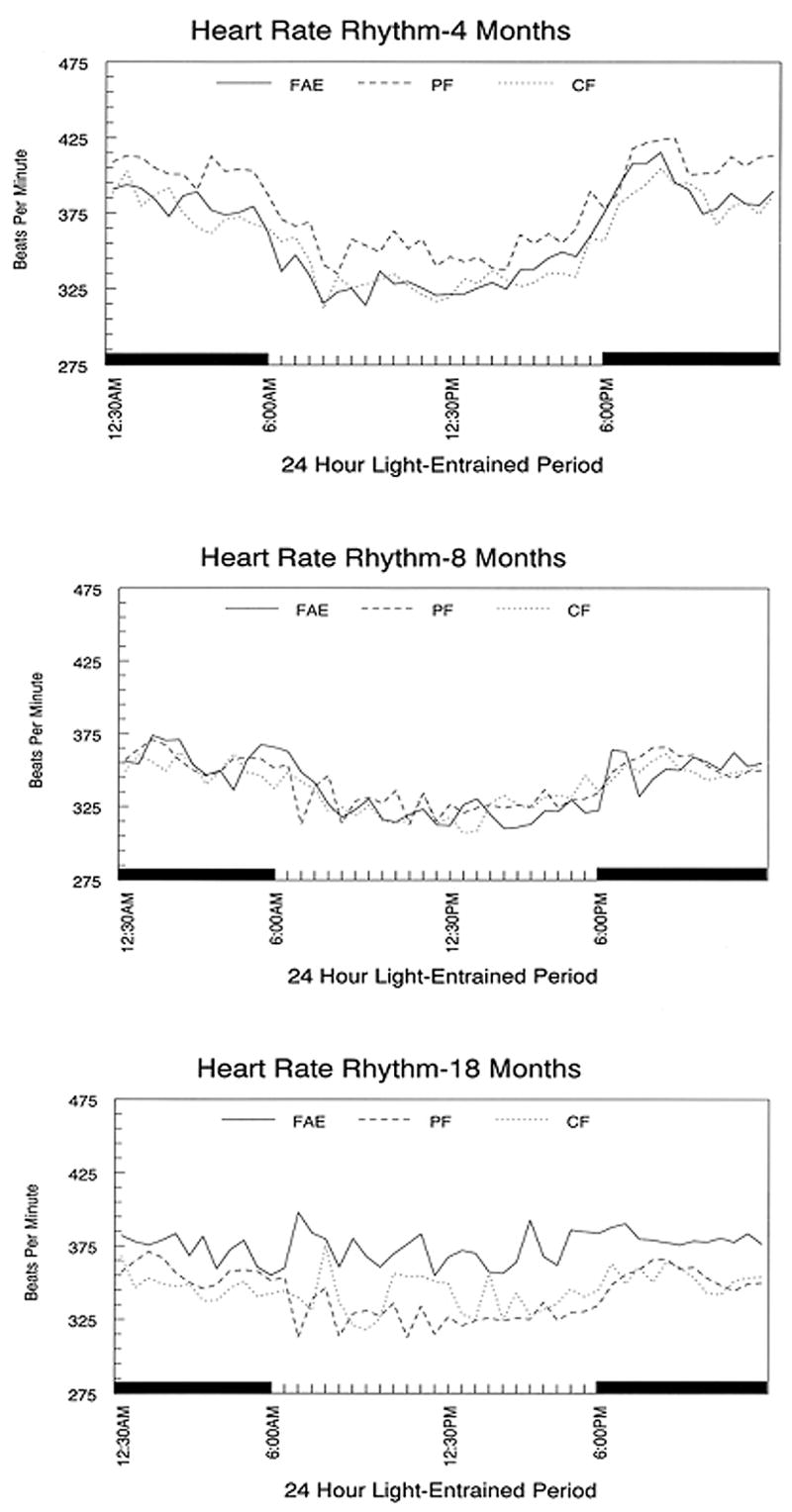

Heart Rate

Individual analyses revealed a distinct circadian rhythm in HR at 4 and 8 months of age (p<0.05) in all FAE, CF and PF males. Subsequent group comparisons using Treatment X Period ANOVAs at each age showed no significant treatment effects at these two ages. At 18 months of age, the analyses of data from individual animals revealed that only 3/8 FAE males, 5/8 PF males and 4/7 CF males exhibited a significant circadian rhythm in heart rate. This loss rate was not significantly different across treatment groups. Data are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Diurnal heart rate rhythm in male FAE and control rats entrained to a 12:12 LD schedule. Circadian rhythms did not differ significantly between treatment groups. Each point represents the 30 min. average of 4–6 animals per treatment group.

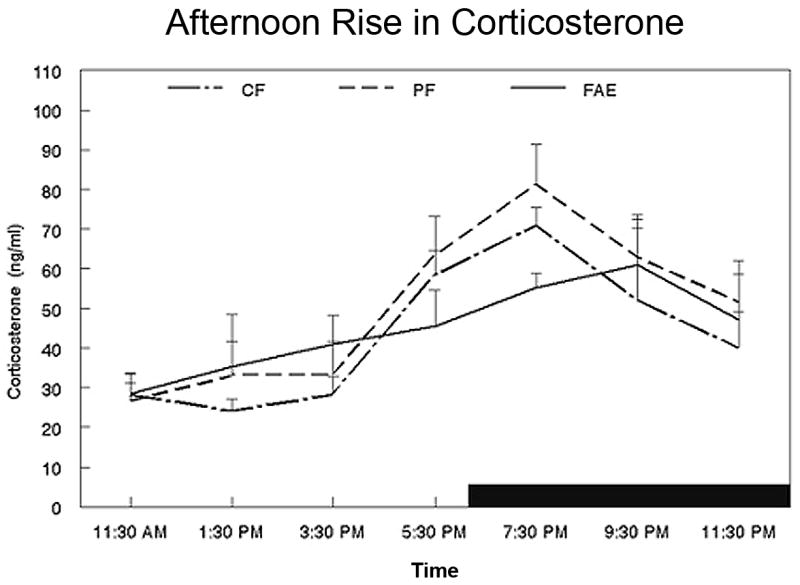

Plasma Corticosterone Rhythm

As shown in Fig. 4, both CF and PF males at 6 months of age exhibited the normal surge in plasma corticosterone prior to the onset of the dark phase of the light cycle, and a continued rise that peaked at 19:30 hrs. In contrast, FAE males exhibit a linear rise in corticosterone between 15:30 and 21:30 hrs, with the peak level detected at 21:30 hrs. This difference in the secretory pattern between FAE and controls was detected in the orthogonal trend analysis, which revealed a significant quadratic component in the response of controls that was not detected in FAE animals (F[2,12] = 4.07; p<0.05).

Figure 4.

Diurnal changes in plasma corticosterone levels in 6 month old FAE, PF and CF male rats (N=5/group). Animals were entrained under a 12:12 LD cycle, with light off at 6:00 PM. Serial blood samples were obtained at two-hour intervals starting at 11:30 AM. Data shown are the mean +/− SEM.

DISCUSSION

The results of these studies reveal a long-term influence of prenatal ethanol exposure on the circadian regulation of core body temperature and corticosterone release in anticipation of feeding. These effects are evident in mature adult animals, and show some characteristics of accelerated aging in the control of circadian rhythms. Together, they suggest a functional disruption of SCN development by ethanol.

At 4 and 18 months of age, FAE males exhibited an earlier rise in core body temperature during the light phase of the LD cycle compared to either CF or PF animals. At 8 months of age, the amplitude of the temperature rhythm of FAE males was significantly smaller than the amplitude of either control group. However, the earlier rise observed in FAE animals at 4 and 20 months was not evident at 8 months, perhaps being masked by the significant decrease in rhythm amplitude at this age. The amplitude of the temperature rhythm in PF and CF controls showed a linear, age-related decrease between 4 and 20 months. The rhythm amplitude of FAE animals, however, decreased by 8 months of age to the level observed in controls at 20 months. No further decrease was detected at 20 months.

In normal animals, there is a surge of plasma corticosterone 1–2 hours prior to the onset of the dark cycle in anticipation to the onset of the feeding during the active phase of the rodent cycle (Buijs et al., 2003), which is paralleled in humans by the early morning rise in cortisol (Weitzman et al., 1971). The diurnal rise in corticosterone is SCN gated through efferents to the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus and lesions of the SCN prevent the afternoon rise in corticosterone (Watanabe and Hiroshige, 1981; Buijs et al., 1993). We observed the normal rodent pattern in both PF and CF controls at 6 months of age. Corticosterone levels were significantly higher at 5:30 pm compared to levels earlier in the afternoon and subsequently peaked at 7:30 pm. In FAE males, there was no detectable surge prior to the onset of the dark cycle. Plasma levels rose in a gradual linear fashion until they peaked at 9:30 pm, which was 2 hours after controls. Plasma corticosterone levels in FAE males did not differ significantly from those observed in the afternoon until 7:30pm, which was 90 minutes after the onset of the dark cycle. This overall pattern of corticosterone secretion in 6 month old FAE males is similar to that previously reported in normal 12 and 20 month old animals (Honma et al., 1996).

Normal aging of mammalian circadian rhythms is generally characterized by a reduction in rhythm amplitude, as well as fragmentation (Oster et al., 2003). Thus, the age-related pattern of alterations in the amplitude of both temperature and corticosterone rhythms of FAE animals raises the possibility that exposure to ethanol during SCN development leads to an acceleration of functional aging in the circadian control of these physiological rhythms. Although the study of physiological aging was not the purpose of this investigation, the incidence in mortality and large tumor formation in this study was less than 5% in all groups prior to the study’s termination at 23 months. Therefore, the changes in circadian regulation of physiological rhythms are not obviously the reflection of a general acceleration of the biological process of aging.

This is the first report of age-related alterations in the circadian regulation of physiological rhythms following prenatal exposure to ethanol. The mechanisms involved are unknown. However, neurotoxic effects of ethanol on the developing SCN appear likely and may be reflected in long-term alterations in the molecular underpinnings that entrain and synchronize individual rhythms. Allen and co-workers (2004) have observed a reduction in the circadian production of BDNF in the SCN of 5–6 month old male rats exposed to alcohol during the early postnatal period. This is a period of rapid brain growth in the rat that is roughly equivalent to third trimester brain development in humans. This same postnatal ethanol regimen also induced shorter and more fragmented free-running rhythms of wheel running activity in males at 2–3 months of age (Allen et al., 2005a) and an enhanced sensitivity to entrainment by light pulses (Allen et al., 2005b). Reduced BDNF production in the hypothalamus and shorter free-running rhythms are frequent concomitants of normal aging (Mont, 2005, Silhol et al., 2005), and are conceptually similar to the changes found in the present study with prenatal alcohol exposure. Thus, it might be expected that similar effects underlie some of the effects we have observed. In support of this, studies by Chen et al. (2006) have demonstrated that prenatal exposure to ethanol altered the diurnal expression of rPER1 and rPER2 in the SCN, suggesting altered SCN function. Alternatively, it cannot be ruled out that the effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on circadian function may be elicited upstream of the SCN, perhaps by changes in retinal ganglion cells or fibers in the retinohypothalamic tract that project to the neurons of the SCN.

No influence of fetal alcohol exposure was observed on the basal circadian rhythm of heart rate at any of the three ages studied. The heart rate data at 4 and 8 months of age were obtained simultaneously with temperature data from the same animals who exhibited alterations in the basal rhythm of body temperature. This selective effect of ethanol may indicate an ethanol effect on brain regions beyond the SCN. While both rhythms are entrained by afferents from the SCN, they involve different pathways, and may also involve differential control by areas within the SCN (Scheer et al., 2003). SCN projections to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus are important for circadian regulation of heart rate, while projections to the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus and the preoptic area are involved in circadian regulation of core body temperature (Pu et al., 1998, Zaretskaia et al., 2003). An additional consideration is the endogenous circadian rhythm maintained by clock genes in cardiomyocytes and regulated by norepinephrine (Burgan et al., 2005).

Age-related changes are well-documented in other regulatory peptides in the SCN, including arginine vasopressin (AVP) and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), which are essential for rhythm entrainment and integration by SCN (Duncan et al., 2001, Kalamatianos et al., 2004). In vivo studies also report age-related changes in the circadian rhythm of the expression of several clock genes intrinsic to the SCN, including Per1, Per2 and Cry2 (Oster et al., 2003, Weinert et al., 2001). Similar changes have been reported in the SCN of young FAE males (Chen et al. 2006), suggesting that prenatal ethanol exposure is influencing SCN development to induce some of the changes observed in the present report. Moreover, the findings of Rojas and co-workers (1999) of reduced VIP immunoreactivity in the SCN in preadolescent FAE animals are consistent with this.

Finally, consideration should be given to the role of the SCN in other functional deficits observed in adult FAE animals, including those related to reproduction and stress. Efferent projections of the SCN are extended throughout the basal forebrain, including the preoptic area (POA), the ventromedial, dorsomedial, and paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus (Buijs et al., 1998, Moore et al., 2002). The regulation and timing of ovulation is controlled by the SCN through projections to regions of the POA that trigger the LH surge (Miller et al., 2004). In a previous study, we found that FAE females, exposed to the same prenatal ethanol regimen used in the present study, exhibited a premature loss of ovulatory cycles (McGivern et al., 1995). At 6–7 months of age, approximately 50% of FAE females were anovulatory, whereas a similar percentage in control groups was not observed until 12 months of age.

Normal aging is accompanied by a reduction in VIP expression within the SCN 11. Recent work by Gerhold and co-workers (2005) shows that premature aging of the hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal axis can be induced in young rats by blocking the actions of VIP fibers from the SCN that innervate GnRH neurons. Thus, it will be of interest to determine if VIP expression is altered in the SCN of FAE animals at an early age.

A role for the SCN in the increased stress reactivity of FAE animals might also be predicted based upon anatomical and functional connections between the SCN and both the PVN and adrenals. Studies have consistently observed long-term HPA hyper-responsiveness to stress in FAE animals, which involves increased CRF expression in the PVN (Gabriel et al., 2005, Lee et al., 2000, Taylor et al., 1982a, Weinberg 1994). The HPA stress responsiveness receives is modulated by the SCN as evidenced by the observation that it differs across the diurnal cycle. This influence is mediated not only by SCN projections to the PVN, but probably SCN sympathetic projections to the adrenal gland as well (Buijs et al., 1997). Further support for an involvement of the SCN in regulating adrenal hormone secretion comes from a recent study demonstrating that light induced regulation of adrenal corticosterone secretion is accompanied by sympathetic regulation of Per1 and Per2, as well as other clock genes in the adrenal cortex (Ishida et al., 2005). Stimulation of adrenal corticosterone secretion was related to light intensity and these effects were eliminated by lesioning the SCN or denervating the sympathetic input to the adrenal. On the basis of these findings, it might be hypothesized that developmental damage to the SCN may influence the normal late afternoon peak of corticosterone secretion, as well as stress responsiveness.

In summary, our data indicate that prenatal ethanol exposure alters the basal circadian rhythms of temperature and corticosterone in a manner consistent with premature aging of the SCN. However, in light of ethanol’s relatively ubiquitous effect on neural development (Goodlett et al. 2005, Miller, 1995, Tajuddin and Druse, 1999), it seems unlikely that this effect stems only from selective damage to the SCN.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abel EL. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Fetal Alcohol Effects. Plenum Press; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Allen GC, West JR, Chen WJ, Earnest DJ. Developmental alcohol exposure disrupts circadian regulation of BDNF in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2004;26:353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen GC, West JR, Chen WJ, Earnest DJ. Neonatal alcohol exposure permanently disrupts the circadian properties and photic entrainment of the activity rhythm in adult rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005a;29:1845–1852. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000183014.12359.9f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen GC, Farnell YZ, Maeng JU, West JR, Chen WJ, Earnest DJ. Long-term effects of neonatal alcohol exposure on photic reentrainment and phase-shifting responses of the activity rhythm in adult rats. Alcohol. 2005b;37:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arjona A, Boyadjieva N, Kuhn P, Sarkar DK. Fetal ethanol exposure disrupts the daily rhythms of splenic granzyme B,IFN-gamma, and NK cell cytotoxicity in adulthood. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1039–1044. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron S, Riley EP. Pup-induced maternal behavior in adult and juvenile rats exposed to alcohol prenatally. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1985;9:360–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1985.tb05560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron S, Tieman SB, Riley EP. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area of the hypothalamus in male and female rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1988;12:59–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaine K, Gasser K, Conway S. Influence of fetal alcohol exposure on the GABAergic regulation of growth hormone release in postnatal rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:1681–1691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijs RM, Wortel J, Van Heerikhuize JJ, Kalsbeek A. Novel environment induced inhibition of corticosterone secretion: physiological evidence for a suprachiasmatic nucleus mediated neuronal hypothalamo-adrenal cortex pathway. Brain Res. 1997;758:229–236. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijs RM, Hermes MH, Kalsbeek A. The suprachiasmatic nucleus – paraventricular nucleus interactions: a bridge to the neurendocrine and autonomic nervous system. Progr Brain Res. 1998;119:365–382. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61581-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card JP, Swanson LW, Moore RY. The Hypothalamus: An Overview of Regulatory Systems. In: Zigmond MJ, Bloom FE, Landis SC, Roberts JL, Squire LR, editors. Fundamental Neuroscience. 1999. pp. 1013–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Chen CP, Kuhn P, Advis JP, Sarkar DK. Prenatal ethanol exposure alters the expression of period genes governing the circadian function of beta-endorphin neurons in the hypothalamus. J Neurochem. 2006;97:1026–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan MJ, Herron JM, Hill SA. Aging selectively suppresses vasoactive intestinal peptide messenger RNA expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the Syrian hamster. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;87:196–203. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnell YZ, West JR, Chen WJ, Allen GC, Earnest DJ. Developmental alcohol exposure alters light-induced phase shifts of the circadian activity rhythm in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1020–1027. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000130807.21020.1b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel KI, Glavas MM, Ellis L, Weinberg J. Postnatal handling does not normalize hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing factor mRNA levels in animals prenatally exposed to ethanol. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2005;157:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhold LM, Rosewell KL, Wise PM. Suppression of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in the suprachiasmatic nucleus leads to aging-like alterations in cAMP rhythms and activation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:62–67. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3598-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlett CR, Horn KH, Zhou FC. Alcohol teratogenesis: mechanisms of damage and strategies for intervention. Exp Biol Med. 2005;230:394–406. doi: 10.1177/15353702-0323006-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National; Acad. Press; Washington, D.C.: 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa RJ, McGivern RF, Noble EP, Gorski RA. Exposure to alcohol in utero alters the adult patterns of luteinizing hormone secretion in male and female rats. Life Science. 1985;37:1683–1690. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(85)90295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa RJ, Nunley KM, Lorens SA, Louie JP, McGivern RF, Bollnow MR. Androgen regulation of adrenocorticotropin and corticosterone secretion in the male rat following novelty and foot shock stressors. Physiol Behav. 1994;55:117–24. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hard E, Dahlgren IL, Engel J, Larsson K, Liljequist S, Lindh AS, Musi B. Impairment of reproductive behavior in prenatally ethanol-exposed rats. Drug Alc Depend. 1984;14:51–61. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(84)90019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom A, Jansson C, Boguszewski M, Olegard R, Laegreid L, Albertsson-Wikland K. Growth hormone status in six children with fetal alcohol syndrome. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85:1456–1462. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb13952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honma S, Katsuno Y, Abe H, Honma K. Aging affects development and persistence of feeding-associated circadian rhythm in rat plasma corticosterone. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:R1514–1520. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.6.R1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida A, Mutoh T, Ueyama T, Bando H, Masubuchi S, Nakahara D, Tsujimoto G, Okamura H. Light activates the adrenal gland: timing of gene expression and glucocorticoid release. Cell Metab. 2005;5:297–307. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph V, Mamet J, Lee F, Dalmaz Y, Van Reeth O. Prenatal hypoxia impairs circadian synchronisation and response of the biological clock to light in adult rats. J Physiol. 2002;543(Pt 1):387–395. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.022236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalamatianos T, Kallo I, Coen CW. Aging and the diurnal expression of the mRNAs for vasopressin and for the V1a and V1b vasopressin receptors in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of male rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2004;16:493–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2004.01196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennaway DJ. Programming of the fetal suprachiasmatic nucleus and subsequent adult rhythmicity. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13:398–402. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(02)00692-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehl M, Barbazanges A, Le Moal M, Maccari S. Prenatal stress induces a phase advance of circadian corticosterone rhythm in adult rats which is prevented by postnatal stress. Brain Res. 1997;759:317–320. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00394-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Schmidt D, Tilders F, Rivier C. Increased activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis of rats exposed to alcohol in utero: role of altered pituitary and hypothalamic function. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;16:515–528. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGivern RF, Clancy AN, Hill MA, Noble EP. Prenatal alcohol exposure and adult expression of sexually dimorphic behavior in the rat. Science. 1984;224:896–898. doi: 10.1126/science.6719121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGivern RF, Holcomb C, Poland RE. Effects of prenatal testosterone propionate treatment on saccharin preference of adult rats exposed to ethanol in utero. Physiol Behav. 1987;39:241–246. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(87)90016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGivern RF, Raum WJ, Salido E, Redei E. Lack of prenatal testosterone surge in fetal rats exposed to alcohol: alterations in testicular morphology and physiology. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1988;12:243–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGivern RF, Handa RJ, Redei E. Decreased postnatal testosterone surge in male rats exposed to ethanol during the last week of gestation. Alcoholism: Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:1215–1222. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb05232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGivern RF, McGeary J, Robeck S, Cohen S, Handa RJ. Loss of reproductive competence at an earlier age in female rats exposed prenatally to ethanol. Alcoholism: Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:427–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGivern RF, Ervin MG, McGeary J, Somes C, Handa RJ. Prenatal ethanol exposure induces a sexually dimorphic effect on daily water consumption in prepubertal and adult rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:868–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW. Generation of neurons in the rat dentate gyrus and hippocampus: effects of prenatal and postnatal treatment with ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:1500–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BH, Olson SL, Turek FW, Levine JE, Horton TH, Takahashi JS. Circadian clock mutation disrupts estrous cyclicity and maintenance of pregnancy. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1367–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk TH. Aging human circadian rhythms: conventional wisdom may not always be right. J Biol Rhythms. 2005;20:366–374. doi: 10.1177/0748730405277378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgane PJ, Panksepp J, editors. The Handbook of the Hypothalamus. Vol. 3. Dekker; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Moore RY, Speh JC, Leak RK. Suprachiasmatic nucleus organization. Cell Tiss Res. 2002;309:389. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0575-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oster H, Baeriswyl S, Van Der Horst GT, Albrecht U. Loss of circadian rhythmicity in aging mPer1−/−mCry2−/− mutant mice. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1366–1379. doi: 10.1101/gad.256103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandi-Perumal SR, Seils LK, Kayumov L, Ralph MR, Lowe A, Moller H, Swaab DF. Senescence, sleep, and circadian rhythms. Aging Res Rev. 2002;1:559–604. doi: 10.1016/s1568-1637(02)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecoraro N, Gomez F, Laugero K, Dallman MF. Brief access to sucrose engages food-entrainable rhythms in food-deprived rats. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:757–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu S, Kalra PS, Kalra SP. Ovarian steroid-independent diurnal rhythm in cyclic GMP/nitric oxide efflux in the medial preoptic area: possible role in preovulatory and ovarian steroid-induced LH surge. J Neuroendocrinol. 1998;10:617–625. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1998.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas CJ, Vigueras RM, Reyes G, Rojas P, Cintra L, Aguilera-Roblero R. Morphological changes produced by prenatal exposure to ethanol on the immunoreactive vasoactive intestinal peptide cells of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Proc W Pharm Soc. 1999;42:75–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudeen PK, Kappel CA, Lear K. Postnatal or in utero ethanol exposure reduction of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area in male rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1986;18:247–252. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(86)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusak B, Zucker I. Neural regulation of circadian rhythms. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:449–526. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott HC, Sun GY, Zoeller RT. Prenatal ethanol exposure selectively reduces the mRNA encoding alpha-1 thyroid hormone receptor in fetal rat brain. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:2111–2117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer FA, Kalsbeek A, Buijs RM. Cardiovascular control by the suprachiasmatic nucleus: neural and neuroendocrine mechanisms in human and rat. Biol Chem. 2003;384:697–709. doi: 10.1515/BC.2003.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider ML, Moore CF, Kraemer GW. Moderate level alcohol during pregnancy, prenatal stress, or both and limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis response to stress in rhesus monkeys. Child Dev. 2004;75:96–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sei H, Sakata-Haga H, Ohta K, Sawada K, Morita Y, Fukui Y. Prenatal exposure to alcohol alters the light response in postnatal circadian rhythm. Brain Res. 2003;987:131–134. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silhol M, Bonnichon V, Rage F, Tapia-Arancibia L. Age-related changes in brain-derived neurotrophic factor and tyrosine kinase receptor isoforms in the hippocampus and hypothalamus in male rats. Neuroscience. 2005;132:613–624. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparber SB. Measurement of drug-induced physical and behavioral delays and abnormalities in animal studies: a general framework. NIDA Res Monogr. 1991;114:148–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suess PE, Newlin DB, Porges SW. Motivation, sustained attention, and autonomic regulation in school-age boys exposed in utero to opiates and alcohol. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;5:375–87. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.5.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajuddin NF, Druse MJ. In utero ethanol exposure decreased the density of serotonin neurons. Maternal ipsapirone treatment exerted a protective effect. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;117:91–97. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Esseveldt KE, Lehman MN, Boer GJ. The suprachiasmatic nucleus and the circadian timekeeping system revisited. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;33:34–77. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AN, Branch BJ, Liu SH, Kokka N. Long-term effects of fetal ethanol exposure on pituitary-adrenal response to stress. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1982a;16:585–589. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90420-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AN, Branch BJ, Cooley-Matthews B, Poland RE. Effects of maternal ethanol consumption in rats on basal and rhythmic pituitary-adrenal function in neonatal offspring. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1982b;7:49–58. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(82)90054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J. Recent studies on the effects of fetal alcohol exposure on the endocrine and immune systems. Alcohol Alcohol Suppl. 1994;2:401–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J, Taylor AN, Gianoulakis C. Fetal ethanol exposure: hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and beta-endorphin responses to repeated stress. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:122–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert H, Weinert D, Schurov I, Maywood ES, Hastings MH. Impaired expression of the mPer2 circadian clock gene in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of aging mice. Chronobiol Int. 2001;18:559–565. doi: 10.1081/cbi-100103976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman ED, Fukushima D, Nogeire C, Roffwarg H, Gallagher TF, Hellman L. Twenty-four hour pattern of the episodic secretion of cortisol in normal subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1971;33:14–22. doi: 10.1210/jcem-33-1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcoxon JS, Redei EE. Prenatal programming of adult thyroid function by alcohol and thyroid hormones. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E318–E326. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00022.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaretskaia MV, Zaretsky DV, DiMicco JA. Role of the dorsomedial hypothalamus in thermogenesis and tachycardia caused by microinjection of prostaglandin E2 into the preoptic area in anesthetized rats. Neurosci Lett. 2003;340:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerberg B, Tomlinson TM, Glaser J, Beckstead JW. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on the developmental pattern of temperature preference in a thermocline. Alcohol. 1993;10:403–408. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(93)90028-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]