Postmenopausal hormone therapy (HT) use among American women over recent decades peaked in the 1999 to 2002 period (Brett & Madans, 1997; Hersh, Stefanick, & Stafford, 2004). The increase before 2002 was promoted by a position statement of the American College of Physicians issued in 1992 that almost all postmenopausal women be offered hormone therapy (American College of Physicians, 1992). This recommendation was based on evidence that suggested that HT not only reduced menopausal symptoms, but also had a potentially protective effect against bone loss and cardiovascular disease (American College of Physicians, 1992). Unless women knew themselves to be at increased risk for breast cancer, HT was generally recommended. However, more recent results from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) randomized clinical trial indicate no protective effect of hormone use on cardiovascular disease, and have even suggested an adverse effect (Rossouw et al., 2002). These results, published in July of 2002, resulted in a change in the recommendations for use of HT at the beginning of 2003. The revised guidelines indicated that short-term postmenopausal HT use was appropriate among postmenopausal women seeking to relieve menopausal symptoms and recommended the discontinuation of HT for women using HT for disease prevention (North American Menopause Society, 2003a, 2003b, 2004).

Changes in the Use of Postmenopausal HT Over Time

Evidence from records of prescriptions filled, physician visits (Hersh et al., 2004; Hing & Brett, 2006), observational studies (Bruist et al., 2004; Ettinger, Grady, Tosteson, Pressman, & Macer, 2003; Haas, Kaplan, Gerstenberger, & Kerlikowske, 2004; Schonberg, Davis, & Wee, 2005) and a national telephone survey (Kelly et al., 2005) indicates a reduction in the use of postmenopausal HT after the recommendation changes, but these estimates have not been based on nationally representative samples or well-specified data on menopausal status and social characteristics.

A better understanding of national changes in the use of HT in the last 15 years can be obtained by examining changes in use of HT in a nationally representative sample and by examining change by subgroups of the population by age, race/ethnicity, education, health care use and health care accessibility.

Empirical Evidence

Given the limited evidence on the timing of changes in the use of postmenopausal HT and changes in recommendations, we have examined change in the use of HT for time periods that roughly represent time before and after the changes in the recommendation for hormone use. Using the data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) III and 1999–2004, cross-sectional studies representative of the civilian, non-institutionalized population of the United States, we have examined postmenopausal HT use in three periods: 1988–1994, 1999–2002 and 2003–2004.

Postmenopausal female respondents aged 50 and over (those who had not had a period for the past 12 months) are included in our analysis, with sample sizes as follows: 3,396 (NHANES III, 1988–1994), 1,967 (NHANES 1999–2002) and 1,046 (NHANES 2003–2004). Because of the way the data are released, it is not possible to analyze change over single years of time. We limit our analysis to oral hormone use because this is the subject of recent recommendations and because few women report use of only the patch format for hormone therapy in the United States.

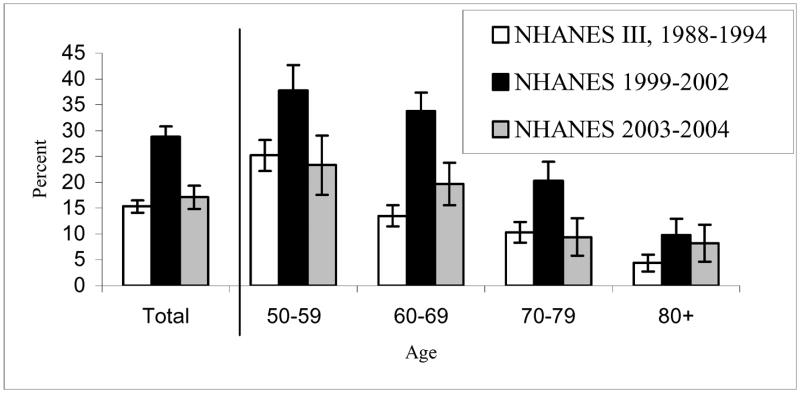

The percent of women using postmenopausal HT in each of these three periods is shown in Figure 1. Between 1988–1994 and 1999–2002, among all postmenopausal women the use of HT nearly doubled, from 15.3% to 28.8%. By 2003–2004 use had almost dropped back to the earlier level, at 17.1%.

Figure 1.

Percentage of Postmenopausal Women, 50 Years or Older Using Postmenopausal Oral Hormone Therapy in 1988–1994, 1999–2002, 2003–2004: NHANES III and NHANES 1999–2004

Note: Numbers of sample for each age group are 805 for ages 50–59, 1,088 for ages 60–69, 893 for ages 70–79, and 610 for ages 80 and over for 1988–1994 NHANES III; 454, 693, 465, 355 for NHANES 1999–2002; and 212, 361, 245, 228 for NHANES 2003–2004.

Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Between 1988–1994 and 1999–2002, with the recommendation that HT use was appropriate for most menopausal women, women in all age groups over 50 experienced a significant increase in the use of postmenopausal HT with the largest increase occurring among women aged 60 to 69. Then concomitant with the changes in recommended use after the results of the WHI, all age groups less than 80 experienced a significant reduction in use between 1999–2002 and 2003–2004. The largest decreases in HT use between 1999–2002 and 2003–2004 occurred among those aged 60–69 (41.7% reduction) and 70–79 (53.7%). The level of use in 2003–2004 is not significantly different from that in 1988–1994 in any age group.

The age pattern of postmenopausal HT use has also changed over time. In 1988–1994, HT use was highest among women 50 to 59 and markedly lower for older women; while in 1999–2002 and 2003–2004, HT use was almost as high for women in their 60’s (in 1999–2002, 37.7% for those aged 50–59 vs. 33.8% for those aged 60–69; in 2003–2004, 23.3% for those aged 50–59 vs. 19.7% for those aged 60–69).

Along with changes in rates of usage of HT, we also found changes in the average duration of use among users, from 11.2 years in 1988–1994 to 13.0 and 15.4 years, respectively, in the two more recent periods. In the most recent period, there were very few short-term users of postmenopausal HT: only 3.6% of users had been using for less than a year, indicating very low recent initiation of HT use.

There is also evidence of somewhat different patterns of change in HT use by education. Women with more education (more than 12 years of schooling) were more likely to use HT in 1988–1994 than those with less schooling (20.1 versus 13.5); women with more education experienced a 6% greater increase by 1999–2002 (16.1% in those with higher education compared to 10.1% increase for those with lower education) with 95% CI for the difference [1.26%, 10.74%]. Both education groups had a similar decrease between 1999–2002 and 2003–2004 (11.5 versus 13.2) such that, in 2003 and 2004, women with more than a high school education were about twice as likely to use HT as women with lower education (23% versus 12 %).

One of the reasons that postmenopausal HT use may be related to education is that both HT and education are related to the likelihood of having a regular physician and having health care insurance for women younger than the age of eligibility for Medicare. Those with access to health care and with access to insurance are more likely to see physicians and may be more aware of changes in recommendations for HT use and more likely to follow recommended guidelines. Indeed we find that women who visited a doctor at least once in the past year experienced a significant increase (80%) in HT use between 1988–1994 and 1999–2002 and a significant decrease (42%) between 1999–2002 and 2003–2004; those not seeing a doctor in the past year did not experience a significant change either between 1988–1994 and 1999–2002 or between 1999–2002 and 2003–2004.

Implications of Trends in the Use of Postmenopausal HT

The increase in use of HT during 1990s and the decrease after 2002 appear to reflect responses to changes in the recommendations for hormone therapy use for postmenopausal women in 1992 and 2003. While an association of the timing of change in use with the timing of changes in recommendations is not proof of a relationship, it is suggestive of the link between the changed recommendations and the changes in behavior. The largest proportional increase in the 1988–1994 to 1999–2002 period occurred among women 60–69; then in the next period the largest proportional decrease was among women 70–79. This pattern of change by age reflects, first, the increasing use of postmenopausal HT intended to prevent disease and disability at older ages, rather than to treat menopausal symptoms, and then declining use in response to the conclusion that such usage was not appropriate in light of the associated risks.

We find a somewhat higher level of current usage in this large national sample (17%) than that reported by Kelly and colleagues (12%) (Kelly et al., 2005). Perhaps the fact that we study a somewhat longer period (2003 and 2004) than they observed in their telephone survey (the first half of 2004) accounts for this difference, although our period is centered on a time close to that used in the telephone survey. Interestingly, both surveys found similar usage rates for the 2002 period; the NHANES for 1999–2002 and the early 2002 telephone survey (Kelly et al., 2005) each report HT usage of about 28%.

This report of the estimated change in HT use based on a nationally representative sample of the U.S. postmenopausal female population provides important information that confirms and extends results from previous studies on changes in HT use. Because almost all women who take part in the physical examination portion of the NHANES who are eligible for the postmenopausal HT questions provide answers (98% in 1988–1994, 94% in 1999–2002, and 95% in 2003–2004), our reports of changes in postmenopausal HT use are of particular value compared to other studies with very low response rates (Kelly et al., 2005).

Health Care Access and Changes in the Use of Postmenopausal HT Use

Most women in the postmenopausal ages appear to have regular medical care. About 93% of the postmenopausal women in our sample had visited at least one health care provider in the past year. Health care use can be a critical factor in use of drugs requiring a physician’s prescription; changes in recommendations for use require women to consult physicians in order to begin or renew prescriptions. Our findings show that those who have seen a doctor in the last year are more likely to make changes in HT use that are in line with recommended guidelines, and thus most postmenopausal women in the U.S seem to be quickly guided by the changes in health-related recommendations. While it is true that women respond quickly to changes in recommended usage of HT drugs, awareness and accessibility may be an important key for changing the practice of HT use. This suggests that members of minority groups, those with lower education, financially deprived women, and immigrants with a limited or no access to health care services may be potentially disadvantaged in terms of exposure to changes in health-related information and/or health care policy changes. It alerts health care professionals that dissemination of health information and health care policy needs to be targeted to those who have limited health care utilization.

Future Study on Changes in the Use of Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy

In addition to trends in HT use per se, it would be interesting to examine other health trends that might have occurred concurrently with changes in HT use. Recent studies have shown that HT increases the level of C-Reactive Protein (CRP) in individuals (Cushman et al., 1999; Pradhan et al., 2002; Ridker, Hennekens, Rifai, Buring, & Manson, 1999), and the increase in HT use may have contributed to the trend of increased CRP levels among women in the U.S. (Ford, Giles, Mokdad, & Myers, 2004; Kim, Alley, Seeman, Karlamangla, & Crimmins, 2006). The potential effect of HT use on population trends in CRP levels is important to examine given the importance of inflammation, particularly CRP, as a risk factor or predictor of cardiovascular diseases (Koenig et al., 1999; Ridker, Glynn, & Hennekens, 1998), cardiac event outcomes (Smith et al., 2004), diabetes (Pradhan, Manson, Rifai, Buring, & Ridker, 2001) and mortality (Harris et al., 1999; Reuben et al, 2002).

Another striking health trend that may potentially be linked to recent reductions in the use of postmenopausal HT is the recent decline in breast cancer rates in the United States (Ravdin, Cronin, Howlander, Chlebowski, & Berry, 2007). In 2003, the incidence of breast cancer sharply declined by 7% in one year after a steady increase of about 1.7% per year from 1990 to 1998 and a steady decline of about 1% per year from 1998 to 2003. This sharp decline between 2002 and 2003 was sustained in 2004, which provides additional support for the hypothesis that the declines in breast cancer incidence may be related to declining use of HT in reaction to the release of the WHI results in mid 2002. Future studies of population health trends related to changes in HT use including trends in CRP and breast cancer will provide a better understanding of women’s health issues at a population level and suggest further avenues for investigation using clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants R01 AG023347, T32 AG00037, K12AG01004 and P30 AG17265 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA).

Grant Support: This research was supported by grants R01 AG023347, T32 AG00037, K12AG01004 and P30 AG17265 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jung Ki Kim, Andrus Gerontology Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089-0191, (email) jungk@usc.edu, (tel) 213-740-0794, (fax) 213-740-0787

Dawn Alley, Robert Wood Johnson Health and Society Scholars Program, University of Pennsylvania, Colonial Penn Center #302, 3641 Locust Walk, Philadelphia, PA 19104-6218, (email) alley@wharton.upenn.edu, (tel) 215-746-2771, (fax) 215-746-0397

Peifeng Hu, Division of Geriatrics, UCLA School of Medicine, BOX 951687, 2339 PVUB, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1687, (email) PHu@mednet.ucla.edu, (tel) 310-825-8253, (fax) 310-794-2199

Arun Karlamangla, Division of Geriatrics, UCLA School of Medicine, BOX 951687, 2339 PVUB, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1687 (email) AKarlamangla@mednet.ucla.edu, (tel) 310-825-8253, (fax) 310-794-2199

Teresa Seeman, Division of Geriatrics, UCLA School of Medicine, BOX 951687, 2339 PVUB, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1687, (email) TSeeman@mednet.ucla.edu, (tel) 310-825-8253, (fax) 310-794-2199

Eileen M. Crimmins, Andrus Gerontology Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089-0191, (email) crimmin@usc.edu, (tel) 213-740-1707, (fax) 213-740-0787

References

- American College of Physicians. Guidelines for counseling postmenopausal women about preventive hormone therapy. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1992;117:1039–1041. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-12-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett KM, Madans JH. Use of postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy: estimates from a nationally representative cohort study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;145:536–545. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruist DS, Newton KM, Miglioretti DL, Beverly K, Connelly MT, Andrade S, et al. Hormone therapy prescribing patterns in the United States. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;104:1042–50. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000143826.38439.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman M, Legault C, Barrett-Connor E, Stefanick M, Kessler C, Judd H, et al. Effect of postmenopausal hormones on inflammation-sensitive proteins: the Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Study. Circulation. 1999;100:717–722. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.7.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettinger B, Grady D, Tosteson A, Pressman A, Macer J. Effect of the Women’s Health Initiative on women’s decisions to discontinue postmenopausal hormone therapy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;102:1225–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.obstetgynecol.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ES, Giles WH, Mokdad AH, Myers GL. Distribution and correlates of C-reactive protein concentrations among adult US women. Clinical Chemistry. 2004;50:574–581. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.027359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas JS, Kaplan CP, Gerstenberger EP, Kerlikowske K. Changes in the use of postmenopausal hormone therapy after the publication of clinical trial results. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;140:184–188. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-3-200402030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris TB, Ferrucci L, Tracy RP, Corti MC, Wacholder S, Ettinger W, et al. Associations of elevated interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein levels with mortality in the elderly. American Journal of Medicine. 1999;106:506–512. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh AL, Stefanick ML, Stafford RS. National use of postmenopausal hormone therapy. Annual trends and response to recent evidence. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291:47–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hing E, Brett KM. Changes in U.S. prescribing patterns of menopausal hormone therapy, 2001–2003. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;108:4–5. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000220502.77153.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JP, Kaufman DW, Rosenberg L, Kelley K, Cooper SG, Mitchell AA. Use of postmenopausal hormone therapy since the Women’s Health Initiative findings. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 2005;14:837–842. doi: 10.1002/pds.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JK, Alley D, Seeman T, Karlamangla A, Crimmins E. Recent changes in cardiovascular risk factors among women and men. Journal of Women’s Health. 2006;15:734–746. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig W, Sund M, Frohlich M, Fischer H, Lowel H, Doring A, et al. C- reactive protein, a sensitive marker of inflammation, predicts future risk of coronary heart disease in initially healthy middle-aged men: Results from the MONICA Augsburg Cohort Study, 1984–1992. Circulation. 1999;99:237–242. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North American Menopause Society. Amended report from the NAMS advisory panel on postmenopausal hormone therapy. Menopause. 2003a;10:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North American Menopause Society. Estrogen and progestogen use in peri- and postmenopausal women: September 2003 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2003b;10:497–506. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000102909.93629.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North American Menopause Society. Recommendations for estrogen and progestogen use in peri- and postmenopausal women: October 2004 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2004;11:589–600. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000145876.76178.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286:327–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan A, Manson J, Rossouw J, Siscovick D, Mouton C, Rifai N, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers, hormone replacement therapy, and incident coronary heart disease prospective analysis from the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:980–987. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.8.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravdin PM, Cronin KA, Howlander N, Berg CD, Chlebowski RT, Feuer EJ, et al. The decrease in breast-cancer incidence in 2003 in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356:1670–1674. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr070105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuben DB, Cheh AI, Harris TB, Ferrucci L, Rowe JW, Tracy RP, et al. Peripheral blood markers of inflammation predict mortality and functional decline in high-functioning community-dwelling older persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002;50:638–644. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridker PM, Glynn RJ, Hennekens CH. CRP adds to the predictive value of total and HDL cholesterol in determining risk of first MI. Circulation. 1998;97:2007–2011. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.20.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Rifai N, Buring JE, Manson JE. Hormone replacement therapy and increased plasma concentration of C-reactive protein. Circulation. 1999;100:713–716. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.7.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonberg MA, Davis RB, Wee CC. After the women’s health initiative: Decision making and trust of women taking hormone therapy. Women’s Health Issues. 2005;15:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SC, Anderson JL, Cannon RO, III, Fadl Y, Koenig W, Libby P, et al. CDC/AHA Workshop on markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: Application to clinical and public health practice report from the Clinical Practice Discussion Group. Circulation. 2004;110:e550–e553. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148981.71644.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]