Abstract

The current study involved a comprehensive comparative examination of overt and relational aggression and victimization across multiple perspectives in the school setting (peers, teachers, observers in the lunchroom, self-report). Patterns of results involving sociometic status, ethnicity and gender were explored among 4th graders, with particular emphasis on girls. Controversial and rejected children were perceived as higher on both forms of aggression than other status groups, but only rejected children were reported as victims. Both European American and African American girls showed a greater tendency toward relational aggression and victimization than overt aggression or victimization. Results indicated negative outcomes associated with both relational and overt victimization and especially overt aggression for the target girl sample. Poorer adjustment and a socially unskillful behavioral profile were found to be associated with these three behaviors. However, relational aggression did not evidence a similar negative relation to adjustment nor was it related to many of the behaviors examined in the current study. Implications of these results are discussed.

Keywords: Aggression, Victimization, Peer Relations, Gender, Ethnicity

For many years, studies of children's aggression and victimization focused on overt, confrontational behaviors like physical and verbal assault, threats, and insults. The vast literature that has been amassed confirms that for many children, overt aggression (see Coie & Dodge, 1998) and victimization (Juvonen & Graham, 2001) are recurring and stable problems that place children at risk for a host of adjustment difficulties, both internalizing and externalizing. More recently, conceptualizations of aggression and victimization have been broadened to include more “relational” forms of aggression such as negative gossip, ostracism, or manipulation of social relationships. Whether these forms of aggression are referred to as indirect, social, or relational aggression, all capture to some degree behaviors that are intended to harm another's reputation, social relationships, or feelings of inclusion by the peer group. Ranging from direct and unambiguous exclusion to indirect and even disguised attacks (e.g., negative gossip in the guise of helpful advice), relational forms of aggression are characterized by an intent to do social harm, using relationships to inflict the damage.

The inclusion of relational aggression in our conceptualization of harm has also broadened the range of children identified as potential targets of intervention, and most of those identified in this casting of a wider net are girls. In fact, researchers have found that as many as 60% of girl aggressors (Henington, Hughes, Cavell, & Thompson, 1998) and 71.4% of girl victims (Crick & Nelson, 2002) would be overlooked if intervention programs excluded relational forms of harm from their identification of perpetrators and victims (corresponding rates for boys were only 7% of aggressors and 21.1% of victims). The predominant instigators and targets of physical aggression are boys (Coie & Dodge, 1998), so it is not surprising that a literature historically focused on physical aggression would place so little emphasis on girls. However, over the past decade, growing interest in girls' aggression has generated much research activity (Pepler, Madsen, Webster & Levine, 2005; Putallaz & Bierman, 2004), including a proliferation of studies on relational aggression and its victims. But the topic is still in its infancy and many questions remain.

The current study aims to further the development of this emerging literature with a comprehensive comparative examination of aggression and victimization in the school setting, with a particular emphasis on girls. We first collected peer nominations from a large and diverse sample of elementary aged children (boys and girls) to validate and expand upon previous research on gender, ethnicity, and sociometric status differences in both overt and relational forms of aggression and victimization. To address the paucity of data on girls, we then selected a smaller sub-sample of African American and European American girls for a more in-depth study of girls' relational aggression and victimization as compared to more overt forms. Using a multi-method, multi-informant approach, the objectives of the current study were to: 1) explore the role of ethnicity and sociometric status in aggression and victimization; 2) address unresolved questions in the adjustment correlates of aggression and victimization, particularly relational forms; 3) provide a broader and more complete behavioral profile of aggressors and their victims.

Gender, Ethnicity, Sociometric Status and Relational Aggression/Victimization

Gender

Because interest in girls' aggression evolved in tandem with an increased focus on aggression's more relational forms, the implication might be that most relational aggressors are females, and, in fact, that stereotype predominates in the popular press. However, empirical evidence is less compelling; although some studies find girls more relationally aggressive than boys, others report no gender differences or even higher rates of relational aggression among boys than girls (for a review, see Underwood, 2003). Where gender differences are found more consistently is in the proportional use of physical and relational aggression in that girls are more apt to use relational aggression than physical aggression (Crick, 1995; Crick & Grotpeter, 1995; Henington et al., 1998; Loukas, Paulos, & Robinson, 2005). Boys, on the other hand, appear to utilize the two more equally, with correlations between physical and relational aggression for boys sometimes so high (in the .85 range) that discriminant validity is lacking (Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004; Nelson, Robinson, & Hart, 2005; Tomada & Schneider, 1997). Research regarding relational victimization has lagged behind that of relational aggression and possesses some of the same inconsistencies, but there is increasing evidence that girls experience more relational than physical victimization (Cullerton-Sen & Crick, 2005), and are more relationally victimized than boys (Crick & Bigbee, 1998; Cullerton-Sen & Crick, 2005; Ostrov & Keating, 2004). Thus, in summary, boys are generally found to be more overtly aggressive and victimized than girls, and girls more relationally victimized than boys. We expected to replicate these findings in our study. However, based on inconsistencies in previous research, we made no predictions about gender differences in relational aggression.

Ethnicity

There is a much smaller literature on ethnicity differences in aggression and victimization. African American elementary school children have been higher on peer nominations of overt and relational aggression than European American children (David & Kistner, 2000; Osterman, Bjorkqvist, Lagerspetz, Kaukiainen, Huesmann, & Fraczek., 1994), but no ethnic differences emerged in adolescents' self reports of either overt or relational aggression (Prinstein, Boergers, & Vernberg, 2001). Hanish and Guerra (2000) found no ethnic differences in children's peer ratings of overt victimization, but African American youth in a comprehensive national survey reported being bullied more often than European American youth (Nansel, Overpeck, Pilla, Ruan, Simons-Morton, & Scheidt, 2001). Given the relative lack of information on ethnicity and aggression and victimization, especially on ethnicity and relational victimization, we considered this analysis exploratory.

One explanation proposed for girls' proportionally greater use of relational aggression is that girls are socialized to refrain from outwardly expressing anger or engaging in confrontation and conflict, a pattern that discourages their use of overt aggression and instead encourages a preference for indirect forms of aggression that are more likely to shield the perpetrator's identity (Underwood, 2003). Almost all prior research in this field has been conducted using white middle class subjects. Yet some researchers have proposed that African American families socialize their children in less sex-specific ways than European American families do, and that gender neutrality is instead the norm, with African American daughters encouraged to be as assertive, strong, and independent as sons (Hill & Sprague, 1999; Peters, 1988). If this is the case, then we might expect to see less of a preference or differential between overt and relational aggression among African American girls than European American girls. Given this logic, it was our expectation that African American girls would use both forms of aggression equivalently, whereas European American girls would exhibit a preference for relational aggression.

Even further complicating the interpretation of previous research is that these studies did not control for socioeconomic status (SES), a significant confound when exploring ethnic/race differences in the United States. In fact, in the Osterman et al. (1994) samples, the confound with SES was explicit in that the African American girls were drawn from a more economically disadvantaged school than all other ethnicities. Multiple studies have shown that low SES children are more likely than their higher SES peers to be overtly aggressive (Coie & Dodge, 1998), and Xie, Farmer, and Cairns (2003) found high levels of physical aggression among middle-school girls in their inner-city African American sample, higher in fact than among rural and suburban African American girls from a multi-ethnic study that followed a similar protocol (Xie, Cairns, & Cairns, 2002). But levels of social and relational aggression in Xie et al.'s (2003) inner-city sample were quite low (and lower than those in the rural-suburban African American girls). Thus, in investigating differences in proportional use of aggression between African American and European American girls, this study specifically controlled for SES.

Sociometric status

The pattern for sociometric status has been much more consistent, with rejected and controversial children consistently reported as being more overtly and relationally aggressive than their peers (Nelson et al., 2005; Tomada & Schneider, 1997). Rejected children also appear more likely to be victimized (both overtly and relationally) than other children (Crick & Bigbee, 1998; Cullerton-Sen & Crick, 2005; Paquette & Underwood, 1999). However, researchers have generally not examined the relation between controversial status and overt and relational victimization. In one study, Perry, Kusel and Perry (1988) found both rejected and controversial children to be more overtly aggressive than popular and average children, but only rejected children were more overtly victimized than any other status group. Controversial children were no more likely to be overt victims than popular and average children, perhaps because retaliating or aggressing against them might be too risky given their high profile, their frequent use of aggression, and their likeability among a portion of their peers. But relational forms of aggression could serve the purpose of indirectly and more safely retaliating against controversial children, in which case we might find controversial children also high on relational victimization. The size of our sample and the inclusion of both forms of aggression and victimization in our sociometric measure allowed us to test this possibility among boys and girls.

Consistency across Multiple Informants

Although past research indicates that cross-informant agreement varies as a function of the child's age, gender, and type of aggression involved (Hawker & Boulton, 2000; McEvoy, Estrem, Rodriguez, & Olson, 2003; McNeilly-Choque et al., 1996; Tomada & Schneider 1997), generally peer reports and teacher reports of aggression are more highly correlated than either is with self report (e.g., Cairns, Cairns, Neckerman, Ferguson, & Gariepy, 1989; Xie et al., 2002). In contrast, low to moderate correlations among teacher, peer, and self reports of victimization are generally found (e.g., Crick & Bigbee, 1998; Cullerton-Sen & Crick, 2005). Few studies have used naturalistic observation to assess aggression and victimization, especially relational forms, and findings about concordance of observer report with other informants are mixed. Observed aggression and victimization generally correspond more with peer and teacher ratings than with self reports among elementary school children (e.g., Pellegrini & Bartini, 2000; Tapper & Boulton, 2004), although Tapper and Boulton did find low but significant agreement between observers and self reports of indirect aggression. Among preschool populations, McNeillyChoque et al. (1996) reported moderate correlations between observer and teacher reports of overt but not relational aggression, whereas the findings of Ostrov and Keating (2004) were the reverse; there was more agreement between teachers and observers regarding relational aggression than overt. Although a somewhat mixed picture emerges from past research, we anticipated highest concordance among our teacher and peer informants, especially for overt aggression and victimization. It was expected that the quality and predictive utility of any assessment of aggression and victimization would be strengthened by combining the information garnered from our multiple informants and methodologies into a single score for each aggression and victimization type.

Ethnicity of the teacher

Earlier it was argued that there exists a different socialization pattern between African American and European American girls. It is possible that this differential socialization pattern could extend to our teachers as well, such that teacher ethnicity would influence the amount of aggression they report among their students, with African American teachers reporting similar levels of overt aggression but less relational aggression among their students than European American teachers. Indeed there is some evidence suggesting that teacher ethnicity does not influence their reporting of overt aggression. Hudley (1993) found that African American boys were more likely to be perceived as aggressive by teachers of all races. Similarly, Leff, Kupersmidt, Patterson and Power (1999) found that both African American and European American teachers more accurately identified bullies among their African American than European American students. The authors suggested that the higher base rates of bullying among their African American sample may have heightened the saliency of this behavior for the teachers, thus facilitating the teachers' identification of overt aggressors regardless of their own ethnicity. There has been no research examining the influence of teacher ethnicity on their reporting of relational aggression. The ethnic diversity among the teachers of our target girls allowed us to examine the relation between teacher ethnicity and their ratings of aggression. Based on past research and our hypothesized socialization difference, we predicted that African American teachers would report similar levels of overt aggression among their students but would be less sensitive to their students' use of relational aggression than European American teachers.

Adjustment Indices and Social Behavior

Physical and verbal aggression are highly stable characteristics and, especially in the case of physical aggression, constitute a risk factor for both concurrent and future adjustment difficulties (see Coie & Dodge, 1998). Longitudinal studies of relational aggression are fewer but still suggest moderate stability (Tomada & Schneider, 1997). Less clear is the degree to which relational aggression is a risk factor for adjustment difficulties. Concurrently, it has been significantly correlated with depression, loneliness, social anxiety, externalizing symptoms, and peer rejection during middle childhood (Craig, 1998; Crick & Grotpeter, 1995), and relationally aggressive adolescent girls endorsed more negative self-representations, greater loneliness, and higher levels of externalizing behavior (Moretti, Holland, & McKay, 2001; Prinstein et al., 2001). However, relational aggression has also been linked to higher social intelligence, clique centrality, and perceived popularity, especially for adolescent girls (Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004; Kaukiainen, Bjorkvqvist, Lagerspetz, Osterman, Salmivalli, Rothberg, & Ahlbom, 1999; Xie, et al., 2002), and it has been unrelated to later adjustment difficulties like teen pregnancy and school dropout (Xie et al., 2002). It also seems to be a fairly normative and widespread behavior among girls, at least at moderate levels, and may sometimes serve adaptive functions (Underwood, 2003), in which case labeling all forms of it maladaptive or deviant may be premature. Regarding relational victimization, the results seem clearer. Relationally victimized children experience significant socio-emotional challenges including internalizing difficulties and lower peer status even after overt victimization is controlled for (see Crick & Bigbee, 1998; Crick & Grotpeter, 1996; Cullerton-Sen & Crick, 2005; Paquette & Underwood, 1999; Prinstein et al., 2001). However, only one of these studies included teacher ratings of adjustment (Cullerton-Sen & Crick, 2005).

Perhaps a reflection of the few observational studies examining relational aggression and victimization, there has been little identification and compilation of behaviors characterizing relational victims and perpetrators. Yet developing a behavioral profile of relational aggressors and their victims, especially in contrast to overt aggressors and victims, is essential to further our theoretical understanding of relational aggression as well as guide the development of empirically based intervention programs. Thus, a final purpose of the present research was to provide a comparative examination of the relation between both forms of aggression and victimization and indices of adjustment and social behavior. In addition to incorporating adjustment and behavioral assessments of teachers, peers and self-reports, the current study includes a behavioral observational component to allow for a more specific set of behavioral measures. The combination of multi-assessor ratings and behavioral data on girls should allow for validation of earlier research, while adding to the growing literature on girls' aggression and victimization.

Method

Participants

The current research involves data from a comprehensive study of two successive cohorts of 4th grade public school children in a midsized southeastern city. Sociometric nominations were obtained from a total of 1,397 students on 913 boys and 915 girls in the 78 4th-grade classrooms of 13 public schools. Five of the schools were predominantly African American, 3 were predominantly European American, and 5 were racially balanced. Participation rates within schools ranged from 62% to 96%, with a mean of 72%. The sample was ethnically diverse and reflective of the community with the vast majority being of African American (52%) or European American (42%) descent but also including Asian (3%) and Hispanic (2%) children.

Grade-wise sociometric and behavioral nominations were obtained from all children. An unlimited nomination procedure was employed such that children were not restricted in the number of peers they could nominate in response to any question. All children were asked to indicate those peers: (1) who they like the most, (2) who they like the least, (3) who fight a lot (overt aggression), (4) who get picked on and teased by other kids (overt victim), (5) who leave others out and try to get other kids not to like someone (relational aggression), (6) who have mean things told about them behind their backs or who get left out of things on purpose (relational victim), (7) who try to make sure everyone who wants to play or be involved in something is included and not left out (inclusive), (8) who act shy or who play and work alone a lot because they're too shy (shy), (9) who seem unhappy and sad a lot (sad), and (10) who cooperate, help others, and share a lot (prosocial). All nominations were summed and standardized within classroom. Children were classified as popular, rejected, average (including unclassified), or controversial status on the basis of the liked most and liked least votes they received using the criteria specified by Coie, Dodge, and Coppotelli (1983) with scoring modifications developed for use with unlimited modifications (Terry, 2000). Children were classified as being rejected by peers if their social preference score was less than −1, standardized like most score was less than 0, and standardized like least score was greater than 0. Children were classified as popular if their social preference score was greater than 1, standardized like most score was greater than 0, and standardized like least score was less than 0. Controversial children were those with social impact scores greater than 1. Children were classified as being average if their social preference score was between −1 and 1 and their social impact score was less than 1.

Target Girl Sample

To address the relative paucity of detailed information available in the peer relations literature on girls, 238 assenting girls (119 African American, 119 European American) with parental permission were selected from the two cohorts for more detailed study. Consent rate was 90% for girls invited to participate in the study. Target girls were chosen so as to include an equal number of African American and European American girls distributed equally among rejected, average, and popular sociometric status types. The Hollingshead (1975) index of sociometric status (SES) for the target girls' families ranged from 14 to 66 (M = 41.45, SD = 14.06). Because there were significant SES differences across sociometric status groups [F(2,234) = 8.70, p < .0001; M = 35.21, 41.78, and 46.74 for rejected, average, and popular girls, respectively] and across ethnicity [t (1, 235) = 8.48, p<.0001; M=48.27 for European Americans; M=34.69 for African Americans], target girls' SES was controlled in all analyses.

Measures

Teacher Measure

The teachers of all target girls completed questionnaires in the spring evaluating the girls on a variety of dimensions. The measure was adapted from the Teacher Checklist of Social Behavior (Coie, Terry, Underwood, & Dodge, 1992) and consists of 82 items comprising 15 scales (i.e., overt aggression, relational aggression, overt victimization, relational victimization, hyperactivity, disruption, social avoidance, fear of negative evaluation, depression, empathy, leadership, inclusiveness, entry competence, conflict resolution, and academic competence). Teachers rated each item along a 5-point scale (1 = never true to 5 = usually true). This measure was highly reliable as individual scale reliability coefficients ranged from .83 to .96, with an overall alpha coefficient across the measure of .89. Fifty-eight teachers (38 European American, 19 African American, 1 Asian, 5 males) provided information on our target girls. Teachers were paid $20 for each completed questionnaire.

Lunchroom Observations

In order to get a naturalistic glimpse into the girls' social behavior and experiences, each girl was observed during lunch in her school cafeteria on 5 different occasions. Observers, blind to the girls' sociometric status, rated the girls' lunchroom social interactions on five consecutive days during the spring using a 21-item behavioral coding system [i.e., overt aggression (acts of physical aggression or verbal abuse), relational aggression (deliberate exclusion of a peer from ongoing interaction), overt victim (being the target of any overtly aggressive act), relational victim (being deliberately excluded from interaction), sociability with adults, sociability with peers, watch, initiate, initiations accepted, initiations rejected, silly, bossy, prosocial, inclusive, positive, angry, sad, included, approached, accepts approach, rejects approach]. On the first day of coding, a team of coders spent one hour in the targeted classroom prior to lunchtime to familiarize themselves with the girls and their classmates. No coding took place during this classroom familiarization period. Subsequently, a coder observed each girl during one ten-minute section of the 30-minute lunch period. After each ten-minute observation period, coders rated the frequency of each behavior on a 3-point scale (0 = none, 1 = some, 2 = a lot). Ratings were completed 5 times per girl and scores were based on a total of 50 minutes of observation (10 minutes × 5 days). Thirteen percent of the observations were completed simultaneously by two coders to assess inter-rater reliability. Coders were able to use this system quite reliably as kappa coefficients for the individual codes ranged from .87 to 1.00, with an overall kappa of .91.

Self-Report Measures

In order to obtain an index of self-reported adjustment, target girls completed the Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1981; study alpha= .85), the Social Anxiety Scale for Children –Revised (SASC-R; LaGreca & Stone, 1993; study alpha=.88), and the Children's Loneliness Scale (Asher & Wheeler, 1985; study alpha=.82) during the course of the study. The target girls also completed Crick and Grotpeter's (1996) self-report measure of perceived victimization, yielding an assessment of how much they perceived themselves to be a target of relational and overt aggression by peers (study alpha=.84).

Results

Consistency of Aggression and Victimization Ratings

The first sets of analyses concerned the inter-rater consistency of the assessments of aggression and victimization within the target sample of girls. The correlations reported in Table 1 permit an examination of the agreement across reporters on the two types of aggression and victimization within our target sample. Peers and teachers agreed on who they perceived to be overt and relational aggressors as well as victims of both overt aggression and relational aggression. However, the correlations between teacher and peer ratings of overt and relational aggression and their ratings of overt and relational victimization were almost as high, suggesting significant overlap between perceptions of the two types of aggression and especially the two types of victimization by teachers and peers.

Table 1.

Correlations among Aggression and Victimization Measures (Target Girl Sample)

| Peer Ratings | Teacher Ratings | Lunchroom | Self | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overt Aggress |

Relation Aggress |

Overt Victim |

Relation Victim |

Overt Aggress |

Relation Aggress |

Overt Victim |

Relation Victim |

Overt Aggress |

Relation Aggress |

Overt Victim |

Relation Victim |

Overt Victim |

|

| Peer | |||||||||||||

| Relational Aggression |

0.51** | ||||||||||||

| Overt Victim |

0.14* | 0.09 | |||||||||||

| Relational Victim |

0.26** | 0.26** | 0.57** | ||||||||||

| Teacher | |||||||||||||

| Overt Aggression |

0.48** | 0.29** | 0.37** | 0.40** | |||||||||

| Relational Aggression |

0.29** | 0.32** | 0.21** | 0.30** | 0.78** | ||||||||

| Overt Victim |

0.31** | 0.08 | 0.52** | 0.52** | 0.53** | 0.42** | |||||||

| Relational Victim |

0.38** | 0.23** | 0.55** | 0.50** | 0.67** | 0.57** | 0.81** | ||||||

| Lunchroom | |||||||||||||

| Overt Aggression |

0.26** | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.23** | 0.17* | 0.11 | 0.14* | |||||

| Relational Aggression |

0.04 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.00 | −0.06 | −0.04 | −0.11 | −0.10 | 0.24** | ||||

| Overt Victim |

0.11 | 0.01 | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.04 | −0.10 | −0.04 | −0.06 | 0.15* | −0.05 | |||

| Relational Victim |

0.02 | −0.08 | 0.28** | 0.23** | 0.14* | 0.06 | 0.21** | 0.24** | 0.15* | 0.08 | −0.05 | ||

| Self | |||||||||||||

| Overt Victim |

0.03 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.21** | 0.14* | 0.19* | 0.25** | 0.15* | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.22** | |

| Relational Victim |

0.09 | 0.06 | 0.15* | 0.05 | 0.24** | 0.18* | 0.17* | 0.28** | 0.12 | −0.06 | 0.07 | 0.15* | 0.61* |

Note:

p<.05

p<.01

Correspondence between peer and teacher ratings and the lunchroom observations yielded a slightly different picture. Overt aggression in the lunchroom was related modestly to peer rated overt aggression and teacher rated overt aggression, while the correlations between relational aggression as observed in the lunchroom and perceived by peers or teachers were not significant. Interestingly, while there was significant agreement between the three types of informants for overt aggression, but not relational aggression, the reverse pattern was true for victimization. Relational victimization in the lunchroom was correlated significantly with both peer-rated overt victimization and relational victimization, as well as teacher-rated overt and relational victimization. Observed lunchroom overt victimization was not significantly related to either peer or teacher ratings of overt or relational victimization. Thus, with regard to the lunchroom measure, the distinctions between forms of aggression and victimization appeared to matter.

As seen in Table 1, self-reported overt victimization related only slightly to teacher-rated overt victimization, and not to peer or observer reports of overt victimization. Self-reported relational victimization related significantly to teacher reports of relational victimization and observer reports, but not to peer perceptions. Interestingly, both lunchroom and teacher reports of relational victimization related to both overt and relational self-reported victimization. In fact, all of the teacher measures of aggression and victimization related significantly to self-reported relational and overt victimization. Teachers appeared very sensitive to children's reports of victimization, although apparently viewing self-reported victims as both victims and aggressors.

Gender, Ethnicity, and Sociometric Status Differences in the Larger Sample

In the larger sociometric data set, which included behavioral nominations of both boys and girls, it was possible to examine the relationships between gender, ethnicity and sociometric status as predictors of aggression and victimization. A repeated measures Multivariate Analysis of Variance (RM-MANOVA) revealed significant main effects for all subject variables [Gender: F(4,1677)=36.70, p<.001; Ethnicity: F(4,1677)=16.30, p<.001; Status: F(12,4437)=3.24, p<.01]. The RM-MANOVA also revealed significant interactions between gender and status [F(12,4437)=3.24, p<.01] and gender and ethnicity [F(4,1677)=3.48, p< 01]. To interpret the MANOVAS, a series of univariate analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were run for each form of aggression and victimization.

Gender, Ethnicity, and Status Differences in Aggression and Victimization

The univariate analyses confirmed that boys were perceived by peers as more overtly aggressive than girls [F (1,1680) = 92.31, p<.001; M= .35 for boys vs. M= -.30 for girls] but not more relationally aggressive. In terms of victimization, boys were more likely than girls to be seen by their peers as victims of overt aggression [F (1, 1680) = 9.18, p<.001; M =.03 for boys vs. M=-.03 for girls] whereas girls were seen as more likely victims of relational aggression [F (1, 1680) = 18.70, p<.001, M = -.04 for boys vs. M= .06 for girls].

There were significant main effects for ethnicity for both overt aggression [F(1,1680)=62.51, p<.001; M=.24 for African American vs. M=-.24 for European American] and relational aggression [F(1,1680)=12.85, p<.001; M=.17 for African American vs. M=-.12 for European American] but not overt victimization or relational victimization. African American children were seen by their peers as engaging in more aggressive behavior than European American children, both overt and relational, but there was no difference in perceived victimization.

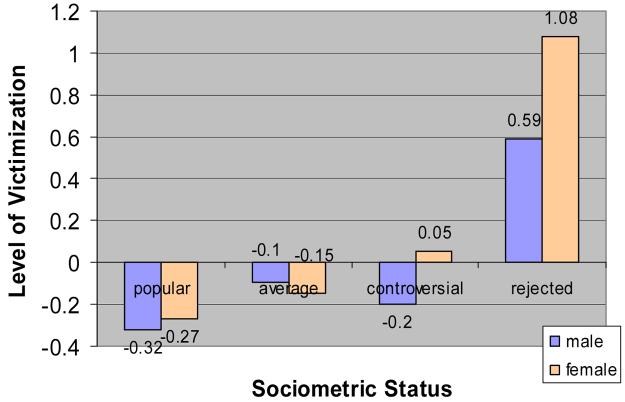

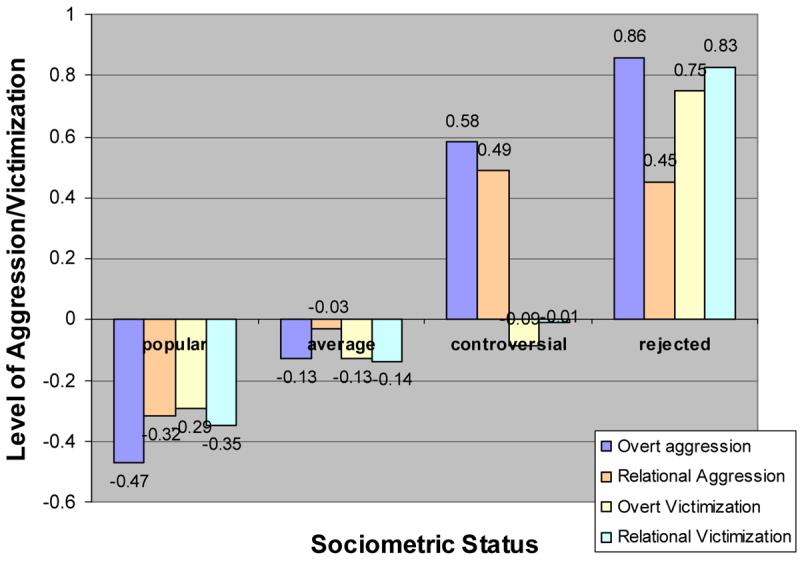

Regarding sociometric status, results indicated significant status effects for overt aggression [F (3,1680) = 76.21, p<.001], relational aggression [F(3,1680)=28.27, p<.001], overt victimization [F(3,1680)=79.62, p<.001] and relational victimization [F(3,1680)=90.26, p<.001]. As seen in Figure 1, both rejected and controversial children were seen by peers as engaging in both overt and relational aggression more than average children who, in turn, engaged in them more than popular children. However, only rejected children were perceived as being more overtly and relationally victimized than all other status groups. Controversial children were seen by peers as engaging in aggressive behavior, both overt and relational, but not as victimized, while rejected children were perceived by their peers as both aggressors and victims.

Figure 1.

Aggression and Victimization by Status

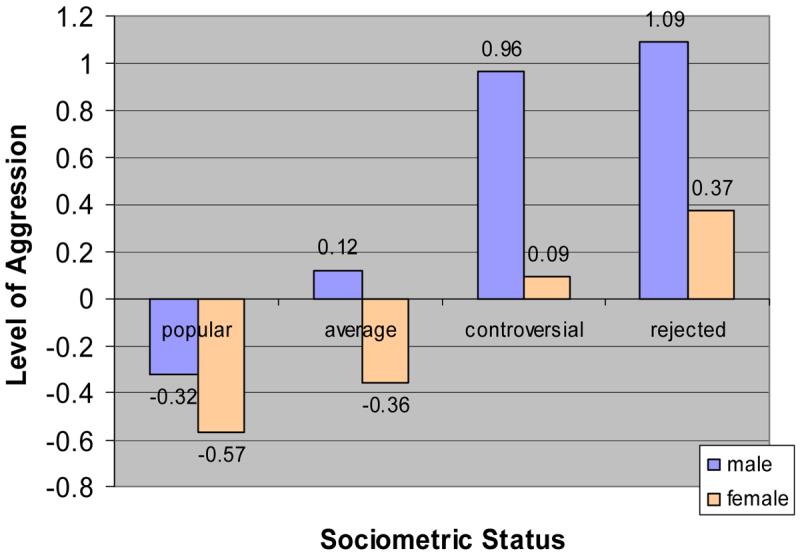

Aggression and Victimization: Interaction Effects

Univariate analyses revealed a significant interaction between status and gender for overt aggression [F (3,1680) = 4.02, p<.01] and overt victimization [F (3,1680) = 6.11, p<.001], but not for either relational aggression or relational victimization. The tendency for controversial and rejected children to be seen as more overtly aggressive by peers was significantly more exaggerated for boys than for girls (see Figure 2a). The reverse was true regarding victimization. Rejected girls were significantly more likely to be seen by their peers as overt victims than boys (see Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Overt Aggression: Gender by Status

Figure 2b. Overt Victimization: Gender by Status

Univariate ANOVAS revealed a significant interaction between gender and ethnicity only for overt aggression [F(1,1680)=11.17, p<.01]. While boys were more aggressive than girls, this pattern was even more exaggerated for African American boys who were seen by their peers as significantly more overtly aggressive (M=.65) than all other groups (M=-.02 for European American boys, M=-.17 for African American girls, M=-.46 for European American girls).

Status and Ethnicity Differences in the Target Sample

Next, we examined the sociometric status and ethnicity differences among the target girl sample controlling for socioeconomic status. A two-way status (Popular, Average, Rejected) by ethnicity (African American, European American) MANCOVA conducted on the aggression and victimization observed in the lunchroom revealed only a significant main effect for status [F(8,442)=3.67, p<.001]. The RM-MANCOVA of teacher reports of aggression and victimization with status (Popular, Average, Rejected) and ethnicity (African American, European American) serving as the between subject variables revealed main effects for status [F (8, 438) = 14.52, p<.001] and ethnicity [F (4,219)=5.60, p<.01]. The RM-MANCOVA of the girls' self-reported victimization revealed only a main effect for status [F(4,402)=3.16, p<.05].

Table 2 contains the results of all follow-up univariate analyses. Results indicated the most differentiation on victimization. In contrast to average or popular girls, rejected girls received higher overt aggression, but not relational aggression scores from their teachers. In terms of victimization, teachers reported rejected girls to be victimized (both overtly and relationally) more than average or popular girls. The lunchroom data were even more striking as only relational victimization showed any significant effect. Rejected girls were observed to be relationally victimized in the lunchroom more than popular or average girls. In terms of self-reported victimization, rejected girls viewed themselves as the target of both overt and relational victimization significantly more than both average and popular girls. With regard to the main effect for race, African American girls were seen by their teachers as higher in both forms of aggression [overt aggression: F(1,222)=13.76, p<.001; relational aggression: F(1,222)=9.47, p<.01] and victimization [overt victimization: F(1,222)=11.97, p<.001; relational victimization: F(1,222)=5.41, p<.05] than their European American classmates.

Table 2.

Aggression and Victimization Means by Status Type (Target Girl Sample)

| Popular | Average | Rejected | F-statistic | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher Measure | |||||

| Overt Aggression | 1.67a | 2.12b | 2.78c | 18.27 | .001 |

| Relational Aggression | 1.94a | 2.43b | 2.70b | 6.21 | .01 |

| Overt Victim | 1.36a | 1.69b | 2.72c | 42.04 | .001 |

| Relational Victim | 1.50a | 1.96b | 3.20c | 50.21 | .001 |

| Lunchroom | |||||

| Overt Aggression | .02 | .04 | .06 | 1.94 | ns |

| Relational Aggression | .09 | .05 | .05 | 1.15 | ns |

| Overt Victim | .00 | .00 | .01 | .82 | ns |

| Relational Victim | .00a | .06a | .13b | 10.83 | .001 |

| Self-Report | |||||

| Overt Victim | 1.40a | 1.56a | 1.86b | 6.20 | .01 |

| Relational Victim | 1.83a | 1.97a | 2.24b | 3.57 | .05 |

Note: Means within rows with different letter superscripts are significantly different.

Within-Ethnicity Analyses of Aggression and Victimization

A follow-up analysis was conducted to investigate whether the observed preference for relational over overt aggression for girls was merely a phenomenon exclusive to European American girls or whether this pattern would hold true regardless of ethnicity. Separate RM-ANCOVAs (controlling for SES) were conducted for overt and relational aggression by ethnicity for all reporters (peer, teacher, lunchroom observers). As predicted, peers reported European American girls to be significantly higher in their use of relational aggression (M=-.12) relative to overt aggression (M=-.46) [F(1,370)=5.94, p<.001]. Teachers too reported European American girls to be significantly more relationally aggressive (M=.13) than overtly aggressive (M=.00) [F(1,473)=9.26, p<.001]. Only the lunchroom observers did not report any significant difference in aggression usage for European American girls. However, contrary to predictions, peers reported African American girls, like European American girls, to be higher in their use of relational aggression (M=.14) relative to overt aggression (M=-.17) [F(1,473)=50.82, p<.001]. Similarly, lunchroom reporters observed African American girls to be more relationally aggressive (M=.06) than overtly aggressive (M=.05) [F(1,112)=5.67, p<.05]. Only teachers did not report any significant difference in usage of overt versus relational aggression for African American girls. Girls demonstrated a preference for relational over overt aggression regardless of their ethnicity.

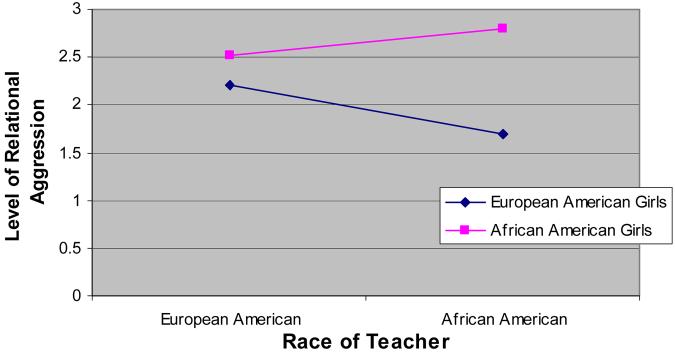

Effect of Teacher Ethnicity

Next, we examined whether the ethnicity of the teacher would influence the amount of relational and overt aggression and victimization they reported as well as whether the ethnicity of the student would affect their ratings. A 2 (Ethnicity of Girl) by 2 (Ethnicity of Teacher) MANCOVA (controlling for student SES) was conducted with overt and relational aggression and victimization serving as the dependent variables. There was no significant main effect for teacher ethnicity, but there was a significant interaction between the ethnicity of girl and ethnicity of teacher [F(4,210)=2.62, p<.05]. Only the follow-up univariate ANOVA for relational aggression was significant [F(1,213)=7.80, p<.01]. As can be seen in Figure 3, African American teachers were more likely to differentiate between African American and European American girls with regard to relational aggression than European American teachers, perceiving African American girls as more relationally aggressive and European American girls as less relationally aggressive than European American teachers did.

Figure 3.

Relational Aggression: Race of Girl by Race of Teacher

Aggression and Victimization and Adjustment in the Target Sample

To estimate the impact of victimization and aggression on the adjustment of children within the school setting, we next examined the relation between overt and relational aggression and victimization with indices of social, academic, and psychological adjustment. Because of the significant overlap between peers', teachers' and lunchroom observers' views of aggression and victimization, we standardized and summed the aggression and victimization scores across our reporters to obtain a single overt aggression, relational aggression, overt victimization, and relational victimization score. These scores thus encompass the multiple perspectives of teachers, peers and lunchroom observers within a single score. Next, given the high correlation between overt and relational aggression and overt and relational victimization, partial correlations were computed controlling for the other aggression or victimization form (e.g., correlations with overt aggression were computed controlling for relational aggression).

As can be seen in Table 3, relational aggression had a very distinct relation to adjustment relative to overt aggression and the two forms of victimization. Only two adjustment indices were significantly related to relational aggression, and their direction indicated the absence of an adjustment problem. Children high on relational aggression were less likely to be nominated by their peers as shy and were less likely to be seen by their teachers as avoiding social situations. In contrast, children seen as high on overt aggression were likely to report feeling depressed and lonely, likely to be observed as angry in the lunchroom, and likely to be reported as depressed by their teachers. Further, children high on overt aggression were likely to have academic problems and to have low social preference scores. Children high on either type of victimization were seen by their peers as sad, reported by their teachers to be depressed and fearful of negative evaluation, and had low social preference scores. In addition, children high on relational victimization were seen by teachers as avoiding social situations, were observed as sad in the lunchroom, and reported feeling lonely. Like overt aggression, overt victimization was significantly correlated with the academic problem index.

Table 3.

Partial Correlations of Aggression and Victimization with Adjustment Indices (Target Girl Sample)

| Mean | Overt Aggression |

Relational Aggression |

Overt Victimization |

Relational Victimization |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer Measures | |||||

| Social Preference | .19 | −.40** | .01 | −.21** | −.48** |

| Sad | .07 | .06 | −.02 | .25** | .15* |

| Shy | .16 | .06 | −.14* | .15* | .02 |

| Teacher Measures | |||||

| Academic Performance | 2.36 | −.27** | − .09 | −.14* | −.09 |

| Depressed | 1.79 | .28** | −.08 | .26** | .24** |

| Social Avoidance | 2.03 | .10 | −.16* | .09 | .25** |

| Fear of Negative Evaluation | 2.46 | .11 | .01 | .18** | .17** |

|

Lunchroom Measures |

|||||

| Angry | .15 | .16* | .09 | .03 | .01 |

| Sad | .02 | .14* | .01 | .02 | .15* |

|

Self-Report Measures |

|||||

| Loneliness | 1.81 | .29** | −.12 | .07 | .19* |

| Depression | 5.43 | .27** | −.07 | .07 | .12 |

| Anxiety | 44.20 | .14* | −.02 | .04 | .06 |

Note:

p<.05

p<.01

Aggression and Victimization and Behavior in the Target Sample

In order to gain some initial insight into what behaviors might prove to be good candidates for intervention, partial correlations were computed between our standardized measures of aggression and victimization with possible behavioral targets of intervention controlling for the other form of aggression or victimization (e.g., overt aggression controlling for relational aggression). Again, a striking feature of these results was the lack of significant relations involving relational aggression relative to overt aggression or the two forms of victimization (see Table 4). Only two behaviors were significantly correlated with relational aggression. According to lunchroom observers, girls high on relational aggression were not apt to watch ongoing interaction in the lunchroom. They were also seen by their teachers to be hyperactive, although to a lesser degree than girls high on overt aggression or relational victimization. Again, it was overt aggression and relational victimization that had the most number of significant correlations, and actually had a fairly similar pattern of results. Girls high on overt aggression and relational victimization were seen by peers as low in prosocial behavior, as not inclusive according to both peers and teacher, as hyperactive and disruptive in the classroom according to their teachers, and as lacking in leadership skills, conflict resolution ability, ability to join in the interaction of others easily, and lacking in empathy. In addition, girls high on overt aggression were also seen as engaging in silly behavior according to lunchroom observers. Like relational victimization, girls high on overt victimization were also seen by their teachers as disruptive, lacking in leadership, entry and conflict resolution skills, and low on empathy.

Table 4.

Partial Correlations of Aggression and Victimization with Behavioral Indices (Target Girl Sample)

| Mean | Overt Aggression |

Relational Aggression |

Overt Victimization |

Relational Victimization |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer Measures | |||||

| Prosocial | .42 | −.46** | −.01 | −.06 | −.28** |

| Inclusive | .25 | −.25** | −.07 | −.10 | −.16** |

|

Teacher Measures |

|||||

| Hyperactivity | 24.61 | .46** | .15* | .11 | .25** |

| Disruptive | 1.92 | .51** | .10 | .20** | .33** |

| Inclusive | 3.73 | −.46** | −.10 | −.13 | −.36** |

| Joins Easily | 3.61 | −.35** | .00 | −.18** | −.37** |

| Resolves Conflicts | 3.42 | −.48** | −.11 | −.20** | −.29** |

| Empathy | 3.60 | −.39** | −.09 | −.15* | −.30** |

| Leader | 3.28 | −.35** | .07 | −.17* | −.34** |

|

Lunchroom Measures |

|||||

| Silly | .05 | .29** | −.13 | .01 | .09 |

| Bossy | .13 | .10 | .12 | −.09 | .05 |

| Watch | .33 | .02 | −.24** | −.09 | .13* |

Note:

p<.05

p<.01

Discussion

Role of Gender, Ethnicity, and Sociometric Status in Aggression and Victimization

A first purpose of the current study was to investigate the role of gender, ethnicity and sociometric status in overt and relational aggression and victimization. Regarding gender, our results conform to predictions. Boys were perceived by peers as more overtly aggressive than girls, whereas there were no gender differences in the use of relational aggression. In terms of victimization, boys were slightly more likely than girls to be seen by peers as victims of overt aggression, whereas girls were viewed by peers as the more likely victims of relational aggression. This pattern is consistent with results of previous research (e.g., Cullerton-Sen & Crick, 2005) and suggests that the more in-depth focus on girls in the second part of the study was warranted. It also foreshadows a general pattern found repeatedly throughout our results, one that underscored the importance of relational victimization.

With regard to sociometric status, our results are also consistent with predictions. Both rejected and controversial children were seen by peers as engaging in overt and relational aggression more than average children, who, in turn, engaged in them more than popular children. These results are consistent with prior research indicating rejected and controversial children to be more overtly and relationally aggressive than their peers (Nelson et al, 2005; Tomada & Schneider, 1997). However, when it comes to victimization, there was a clear consensus among the multiple reporters in our study (peers, teachers, lunchroom observers, the girls themselves) that rejected children were the most likely to be victimized, both overtly and relationally. Controversial children are seen as aggressors, but not victims, whereas rejected children are perceived as both aggressors and victims. These results probably reflect the differences in social power and social skillfulness between controversial and rejected children. Retaliating or aggressing against controversial children, even relationally, may carry risk given their high profile, their frequent use of aggression, and their likeability among a subset of peers. Controversial children may derive their status in part because they use aggression strategically, in a manner that causes harm to another while significantly mitigating the possibility for retaliation, thereby earning them the admiration of a subset of peers. In contrast, rejected children may aggress in a manner that provokes reciprocal aggression, either because of its reactive nature or because of their general lack of skillfulness. Although relational aggression is by definition more indirect or covert and should shield the identification of the perpetrator, the lack of social competence of rejected children may make even their relationally aggressive acts obvious to their peers. This potential difference between controversial and rejected children suggests the need for future research to explore potentially quite subtle differences in the form of aggression used by these two types of children to discern if and how controversial children aggress in a manner that effectively stifles retaliation.

Consistent with prior research, there was a main effect for ethnicity with regard to aggression, specifically African American children were perceived by peers as more overtly and relationally aggressive than European American children (David & Kistner, 2000; Osterman et al., 1994). Teachers also reported this difference among the girls in our target sample (even after controlling for SES), but further viewed their African American students as more victimized than their European American students. Thus, one explanation for observed ethnicity differences in aggression and victimization is eliminated in this study; they do not reflect underlying differences in SES. This suggests the need to look at potential differences in the socialization patterns of African American and European American children.

No ethnicity differences were observed in the lunchroom or in the self-reported victimization data. The lack of ethnicity differences in aggression and victimization observed in the lunchroom may be attributable to the low incidence of aggression observed in this setting. Relational and overt aggression occurred infrequently during lunch (M=.06 and M=.04), making any ethnicity differences in aggression or victimization unlikely to be detected. The lack of ethnicity differences in self-reported victimization may reflect that self-report data do not involve the same degree of social comparison processes as invoked by teachers, peers, or observers when making similar assessments among a broad set of individuals.

Within Ethnicity Analyses of Aggression

Another objective of this study was to investigate through within ethnicity analyses whether relational aggression was a phenomenon predominantly characteristic of aggressive behavior among European American girls. Results indicated relational aggression to the more commonly used aggression regardless of ethnicity. Peers and teachers reported a higher usage of relational aggression relative to overt aggression among European American girls, but peers and lunchroom observers also saw African American girls using more relational aggression than overt aggression. Thus, peers viewed all girls as universally demonstrating a preference for relational over overt aggression. Teachers, however, reported this preference only among their European American students. This result may reflect that the majority of teachers who were themselves European American (66%) were more sensitive to the forms of relational aggression displayed by their European American students than their African American students. Alternatively, they may have been more sensitive to overt aggression when enacted by African American girls than European American girls. However, if we look at the overall pattern across informants, relational aggression appears to be preferred by girls over overt aggression regardless of their ethnicity, at least for the two ethnicities included in the current study. This finding is in keeping with Maccoby's (1998) contention that girls receive a powerful socialization experience within their same-sex peer group to prefer more indirect means of expressing their anger than by direct confrontation and aggression.

We also investigated whether the ethnicity of the teacher affected their ratings of the target girls' aggression and victimization. There was no main effect for teacher ethnicity, suggesting no inherent differences in how our African American and European American teachers used the measure. However, there was one significant interaction between the ethnicity of the teacher and the ethnicity of the student. African American teachers showed more differentiation in their ratings of relational aggression for their African American and European American students than did European American teachers. Teachers generally reported African American girls to be higher on relational aggression than European American girls, a finding more exaggerated for African American teachers than European American teachers. There are two potential interpretations for this result. African American teachers may be more sensitive to the form of aggression African American girls display than their European American colleagues. It may also be the case that African American teachers expect to see less relational aggression from African American girls than European American girls and thus rate its use by African American girls higher when they observe it. The key point, however, is that there were not directional differences in the evaluation by African American and European American teachers, the differences found here were matters of degree.

Adjustment and Behavioral Profiles of Aggressors and Victims

A further purpose of the present research was to explore the adjustment and behavioral correlates of aggression and victimization as seen through multiple perspectives in the school setting. The pattern of relations between our adjustment and behavioral measures and the two forms of aggression was striking for our target sample of girls. Unlike overt aggression, which related negatively to adjustment, similar to prior research (e.g., Coie & Dodge, 1998), relational aggression did not seem problematic for the aggressor. In contrast to overt aggression's clear and pronounced negative behavioral profile, relational aggression correlated significantly with very few behaviors. Relational aggression showed a modest positive association with hyperactivity and a negative association with the tendency to watch the interactions of others in the lunchroom. Similarly, relational aggression only related to the absence of adjustment issues in the present study, evidencing significant negative correlations with shyness and social avoidance. Thus, our results are not consistent with earlier research suggesting a link between relational aggression and poor adjustment (e.g., Crick et al., 1999; Moretti et al., 2001; Prinstein et al., 2001). Relational aggression evidenced no relation to loneliness, depression, social anxiety, peer rejection or externalizing behaviors in the current study. Nor did we find a positive association between relational aggression and social indices as others have (e.g., Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004; Kaukiainen et al., 1999; Xie et al., 2002). Similar to Xie et al. (2002) we found an absence of a relation with negative outcomes.

One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that in the present study relational aggression was treated as a continuous variable, whereas most prior studies focused on children with more extreme relational aggression scores. Thus, it could be that only relatively extreme forms of relational aggression are related to adjustment problems. However, somewhat inconsistent with this explanation is that the three other measures of aggression and victimization, also continuous variables not reflecting extreme scores, were highly related to several adjustment and behavioral indices. This discrepancy in results may reflect that relational aggression in its less extreme forms may serve other functions besides aggression, especially for girls. Negative gossip, for example, may serve to provide information about social norms as well as facilitate social bonding and self-disclosure (Gottman & Mettetal, 1986). Gossip also allows for emotional venting and provides a means to solicit social support (for a further discussion, see McDonald, Putallaz, Grimes, Kupersmidt, & Coie, in press; Putallaz, Kupersmidt, Coie, McKnight, & Grimes, 2004). Thus, the lack of association between relational aggression and maladjustment may reflect a broader set of functions that it serves in addition to aggression. It should be noted that these results in the current research only involved the target sample of girls and thus may not generalize to boys. The greater exclusiveness of girls' friendships, the increased sharing of confidences and self-disclosures among girls, and the greater impact of relational aggression on girls underscore that relational aggression may involve a very different process for girls than boys. Future research involving both boys and girls is required to fully interpret these results.

Both overt and relational victimization were related significantly to multiple adjustment problems and evidenced negative behavioral profiles for our target sample of girls. In particular, the results for victims of relational aggression were quite strong. Relational victims were seen as sad or depressed by all observers, reported feelings of loneliness, appeared avoidant of social situations and fearful of negative evaluation according to their teachers and had low social preference scores. If one function of relational aggression is to inflict harm, the data indicate that it effectively does so. These findings are consistent with earlier research (see Crick & Bigbee, 1998; Crick & Grotpeter, 1996; Cullerton-Sen & Crick, 2005; Paquette & Underwood, 1999; Prinstein et al., 2001). Overt victimization also was related negatively to some of the adjustment indices, specifically, having lower academic performance, being shy and fearful of negative evaluation according to their teachers, seen as sad and shy by peers and had lower social preference scores. If there is a difference between the consequences of the two forms of victimization, it is that relational victimization appears to result in more socially related consequences than overt victimization (i.e., its strong negative correlations with social preference, social avoidance as assessed by teachers, sadness as observed in the lunchroom, and self-reported loneliness). Thus, while there is clearly harm inflicted through both forms of victimization, relational victimization, at least in girls, seems to achieve its purpose; relational victims are relationally harmed.

Interestingly, despite somewhat differing patterns with adjustment, there is a consistent pattern of behavior associated with overt aggression, relational victimization, and overt victimization, especially overt aggression and relational victimization for our girls. All appear disruptive, not inclusive of others, weak in entry and conflict resolution skills, lacking in empathy and low in prosocial behavior. These behavioral results are helpful on the one hand, and present an intellectual conundrum on the other. They are helpful in that they suggest a consistent opportunity for intervention; interventions focused upon improving entry and conflict resolution skills and prosocial and inclusive behavior seem obvious targets for addressing overt aggression and overt and relational victimization. The conundrum is that these behavioral data do not inform us as to why some children are aggressors and some are victims. The only hint comes from the highest correlations in each case. For overt aggression and overt victimization, the two highest correlations are the positive correlation with teacher-reported disruptive behavior and the negative correlation with conflict resolution. For relational victims, the two highest correlations are the negative ones with joins easily and inclusiveness. Perhaps general negative behavior (conflict, disruptiveness) plays a more pivotal role involved in overt aggression and victimization whereas more socially centered deficits (entry skill, inclusiveness) are more central to relational victimization.

Utility of Multiple Informants

Finally, our results illustrate the value of using a multi-measure, multi-informant approach to the study of aggression and victimization. The generally high correspondence found across informants in our study is especially impressive given that very different assessments of aggression and victimization were employed. Rather than completing different versions of the same questionnaire as often done in prior research (e.g., Cullerton-Sen & Crick, 2005), our reporters completed quite different measures of aggression and victimization. The general consistency provides a much stronger case for the results. There is a clear conviction in the finding, for example, that overt aggression and victimization are related to depression for our target girls when teacher, lunchroom observer and self report data all reveal the same result.

Although our informants provided somewhat consistent information, each provided a unique and valuable perspective. Two patterns, in particular, emerge from the comparison across reporters in these data. First, there were some differences in the sociometric status and ethnicity results across informants. The analyses of teacher and peer ratings revealed sociometric status differences across both forms of aggression and victimization, whereas lunchroom data revealed status differences only for relational victimization. Further, teachers and peers were the only informants for which ethnicity results were significant. One explanation for the greater sensitivity of peers and teachers relative to observers is that the lunchroom assessment permitted only relatively gross measurement of aggression and victimization as coders had to rely on behaviors that could be easily observed since subtle behaviors and conversations could not always be discerned. In contrast, peers and teachers draw upon a long history of knowledge of these children in their assessments and have a very good sense of the social dynamics of their classroom. It is also the case that our lunchroom observational codes for aggression and victimization were single items whereas the teacher measures of these two constructs reflect a composite of multiple items.

Regardless, teachers emerged in our study (as in Cullerton-Sen & Crick, 2005), as valuable sources of information on the female experience of aggression and victimization, as indicated by the high consistency found between teachers and all other reporters. Especially with regard to identifying victims, teachers appear to be very sensitive observers of the social worlds of their students. Given the ease with which teacher assessments can be garnered relative to peer assessments of aggression and victimization, future intervention aims may want to consider teachers as an effective resource in identifying troubled children. This is especially the case when other findings in our study suggest that both types of victims, along with overt aggressors, are at the greatest risk for maladjustment and, consequently, the greatest need for intervention.

Summary and Future Directions

The current study involved a comprehensive examination of overt and relational aggression and victimization across multiple perspectives in the school setting. Controversial and rejected boys and girls were perceived as higher on both forms of aggression than other status groups, but only rejected children were reported as victims. Both European and African American girls showed a greater tendency toward relational aggression and victimization than overt aggression or victimization. As expected, results indicated negative outcomes associated with both relational and overt victimization and especially overt aggression. Poorer adjustment and socially unskillful behavioral profiles were found to be associated with these three behaviors, suggesting clear implications for intervention. However, intervention implications for relational aggression were less clear as relational aggression did not evidence a similar negative relation to adjustment nor was it related to many of the behaviors examined in the current study.

Thus, in spite of the clear harm inflicted by female relational aggressors (as evidenced by the negative outcomes associated with relational victimization), their adjustment and behavioral profile do not indicate risk. Further research is needed to understand this result. It may be the case that the correct correlate behaviors were not examined in the present study. It may also be that, because relational aggression is a relatively normative practice among girls, profiles of risk occur only among those who are its most extreme or least skillful perpetrators. Thus, one direction for future research would be to explore the correlates and consequences of relational aggression in a more multi-faceted way, considering its variability in form, function, and severity. For example, at what level of severity does relational aggression become maladaptive or place the aggressor at risk? Another direction is longitudinal analyses of relational aggression to further our understanding of its association with risk. It is critically important to develop a better understanding of relational aggression, not only to determine when it might become problematic for adjustment, but also, and primarily, because it is a determining factor in relational victimization, a variable of clear importance in this study.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by grant MH52843-05 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Portions of this research were presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Albuquerque, New Mexico, April, 1999. The authors wish to acknowledge the statistical assistance provided by Blair Sheppard. We are grateful to the children and teachers who participated in this research and to the staff of the Social Development Lab for their contributions to data coding.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Asher SR, Wheeler VA. Children's loneliness: A comparison of rejected and neglected peer status. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:500–505. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.4.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns RB, Cairns BD, Neckerman HJ, Ferguson LL, Gariepy JL. Growth and aggression: 1.Childhood to early adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25:320–330. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DT, Fiske DW. Convergent and discriminant validation of the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin. 1959;56:81–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen AH, Mayeux L. From censure to reinforcement: Developmental changes in the association between aggression and social status. Child Development. 2004;75:147–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA. Aggression and antisocial behavior. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol, 3. Social, Emotional, and Personality Development. Wiley; New York: 1998. pp. 779–862. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA, Coppotelli H. Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:557–570. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Terry R, Underwood M, Dodge KA. A Teacher Checklist for Social Behavior. 1992 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Craig WM. The relationship among bullying, victimization, depression, anxiety, and aggression in elementary school children. Personality and Individual Differences. 1998;24:123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Craig WM, Pepler D, Atlas R. Observations of bullying in the playground and in the classroom. School Psychology International. 2000;21:22–36. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR. Relational aggression: The role of intent attributions, feelings of distress, and provocation type. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Bigbee MA. Relational and overt forms of peer victimization: A multi-informant approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:337–347. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development. 1995;66:710–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Children's treatment by peers: Victims of overt and relational aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:367–380. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK, Bigbee MA. Relationally and physically aggressive children's intent attributions and feelings of distress for relational and instrumental peer provocations. Child Development. 2002;73:1134–1142. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Nelson Relational and physical victimization within friendships: Nobody told me there'd be friends like these. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:599–607. doi: 10.1023/a:1020811714064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullerton-Sen C, Crick NR. Understanding the effects of physical and relational victimization: The utility of multiple perspectives in predicting social-emotional adjustment. School Psychology Review. 2005;34:147–160. [Google Scholar]

- David CF, Kistner JA. Do positive self-perceptions have a “dark side?” Examination of the link between perceptual bias and aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28:327–337. doi: 10.1023/a:1005164925300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galen BR, Underwood MK. A developmental investigation of social aggression among girls. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:589–600. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanish LD, Guerra NG. The roles of ethnicity and school context in predicting children's victimization by peers. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:201–223. doi: 10.1023/A:1005187201519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawker DSJ, Boulton MJ. Twenty years' research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2000;41:441–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henington C, Hughes JN, Cavell TA, Thompson B. The role of relational aggression in identifying aggressive boys and girls. Journal of School Psychology. 1998;36:457–477. [Google Scholar]

- Hill SA, Sprague J. Parenting in Black and White families: The interaction of gender with race and class. Gender & Society. 1999;13:480–502. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four-factor index of social status. Department of Sociology, Yale University; 1975. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Hudley CA. Comparing teacher and peer perceptions of aggression: An ecological approach. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1993;85:377–384. [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Graham S. Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. Guilford Press; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kaukiainen A, Bjorkqvist K, Lagerspetz K, Osterman K, Salmivalli C, Rothberg S, Ahlbom A. The relationships between social intelligence, empathy, and three types of aggression. Aggressive Behavior. 1999;25:81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Rating scales to assess depression in school-aged children. Acta Paedopsychiatrica. 1981;45:305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaGreca AM, Stone WL. Social Anxiety Scale for Children--Revised: Factor structure and concurrent validity. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1993;22:17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Leff SS, Kupersmidt JB, Patterson CJ, Power TJ. Factors influencing teacher identification of peer bullies and victims. School Psychology Review. 1999;28:505–517. [Google Scholar]

- Loukas A, Paulos SK, Robinson S. Early adolescent social and overt aggression: Examining the roles of social anxiety and maternal psychological control. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2005;34:335–345. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. The two sexes: Growing up apart, coming together. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald KL, Putallaz M, Grimes CL, Kupersmidt JB, Coie JD. Girl talk: Gossip, friendship, and sociometric status. Merrill Palmer Quarterly. in press. [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy MA, Estrem TL, Rodriguez MC, Olson ML. Assessing relational and physical aggression among preschool children: Intermethod agreement. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2003;23:53–63. [Google Scholar]

- McNeilly-Choque MK, Hart CH, Robinson CC, Nelson L,J, Olsen SF. Overt and relational aggression on the playground: Correspondence among different informants. Journal of Research in Childhood Education. 1996;11:47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Johnson S, Moore BL, Underwood MK, Coie JD. African-American girls and physical aggression: Does stability of childhood aggression predict later negative outcomes? In: Pepler DJ, Madsen KC, Webster C, Levene KS, editors. The Development and Treatment of Girlhood Aggression. Erlbaum; Mawhah, NJ: 2005. pp. 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti MM, Holland R, McKay S. Self-other representations and relational and overt aggression in adolescent girls and boys. Behavioral Sciences & Law. 2001;19:109–126. doi: 10.1002/bsl.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285:2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DA, Robinson CC, Hart CH. Relational and physical aggression of preschool age children: Peer status linkages across informants. Early Education and Development. 2005;16:115–139. [Google Scholar]

- Osterman K, Bjorkqvist K, Lagerspetz KM, Kaukiainen A, Huesmann LR, Fraczek A. Peer and self-estimated aggression and victimization in 8-year-old children from five ethnic groups. Aggressive Behavior. 1994;20:411–428. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrov JM, Keating CF. Gender differences in preschool aggression during free play and structured interactions: An observational study. Social Development. 2004;13:255–277. [Google Scholar]

- Paquette JA, Underwood MK. Young adolescents' experiences of peer victimization: Gender differences in accounts of social and physical aggression. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1999;45:233–258. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini AD. The role of direct observation in the assessment of young children. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 2001;42:861–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini AD, Bartini M. An empirical comparison of methods of sampling aggression and victimization in school settings. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2000;92:360–366. [Google Scholar]

- Pepler DJ, Madsen KC, Webster C, Levene KS, editors. The Development and Treatment of Girlhood Aggression. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Perry DG, Kusel SJ, Perry LC. Victims of peer aggression. Developmental Psychology. 1988;24:807–814. [Google Scholar]

- Peters MF. Parenting in Black families with young children: A historical perspective. In: McAdoo HP, editor. Black Famlies. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Vernberg EM. Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30(4):479–491. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putallaz M, Bierman KL. Aggression, antisocial behavior and violence among girls: A developmental perspective. Guilford; NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Putallaz M, Kupersmidt JB, Coie JD, McKnight K, Grimes CL. A behavioral analysis of girls' aggression and victimization. In: Putallaz M, Bierman KL, editors. Aggression, antisocial behavior and violence among girls: A developmental perspective. Guilford; NY: 2004. pp. 110–134. [Google Scholar]

- Tapper K, Boulton MJ. Sex differences in levels of physical, verbal, and indirect aggression amongst primary school children and their associations with beliefs about aggression. Aggressive Behavior. 2004;30:123–145. [Google Scholar]

- Terry R. Recent advances in measurement theory and the use of sociometric techniques. In: Damon W, Cillessen AHN, Bukowski WM, editors. New directions for child and adolescent development: Vol. 88. Recent advances in the measurement of acceptance and rejection in the peer system. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2000. pp. 27–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomada G, Schneider BH. Relational aggression, gender, and peer acceptance: Invariance across culture, stability over time, and concordance among informants. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:601–609. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood MK. Social Aggression among Girls. Guilford; New York, NY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, Cairns RB, Cairns BD. The development of social aggression and physical aggression: A narrative analysis of interpersonal conflicts. Aggressive Behavior. 2002;28:341–355. [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, Cairns BD, Cairns RB. The development of aggressive behaviors among girls : Measurement issues, social functions, and differential trajecories. In: Pepler DJ, Madsen KC, Webster C, Levene KS, editors. The Development and Treatment of Girlhood Aggression. Erlbaum; Mawhah, NJ: 2005. pp. 105–136. [Google Scholar]