Abstract

Neighborhoods with poor-quality housing, few resources, and unsafe conditions impose stress, which can lead to depression. The stress imposed by adverse neighborhoods increases depression above and beyond the effects of the individual's own personal stressors, such as poverty and negative events within the family or work-place. Furthermore, adverse neighborhoods appear to intensify the harmful impact of personal stressors and interfere with the formation of bonds between people, again increasing risk for depression. Neighborhoods do not affect all people in the same way. People with different personality characteristics adjust in different ways to challenging neighborhoods. As a field, psychology should pay more attention to the impact of contextual factors such as neighborhoods. Neighborhood-level mental health problems should be addressed at the neighborhood level. Public housing policies that contribute to the concentration of poverty should be avoided and research should be conducted on the most effective ways to mobilize neighborhood residents to meet common goals and improve the context in which they live.

Keywords: neighborhood, community, depression, poverty

Most theories relating depression to stress focus on events that occur within peoples' immediate lives, such as relationship problems or work stressors. Recent research reveals that depression may be linked to characteristics of the neighborhoods in which people live. Research has only recently undertaken to understand the ways in which neighborhoods affect depression and other forms of mental illness. Much less has been written about how neighborhoods influence mental health compared to the large amount that has been written about how neighborhoods influence problem behaviors like delinquency, crime, drug use, and adolescent childbearing (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000).

It is important to understand the role of neighborhoods in the development of depression for at least three reasons: (a) People often do not realize that they are affected by the context around them and thus mistakenly blame themselves for the invisible stressors that affect their well-being; (b) outsiders also fail to realize that residents of adverse neighborhoods are influenced by their surroundings (high rates of mental health problems in poor neighborhoods may be blamed on the personal characteristics or race of residents rather than on the neighborhoods themselves); and (c) when threats to public health are caused by characteristics of entire communities, it is more efficient to address these threats at the community level rather than to treat each affected individual separately. Thus, it is important to raise public awareness of the mental health risks that accompany adverse neighborhoods.

Issues of neighborhood quality have immediate practical implications. The New Orleans neighborhoods most severely damaged by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 were areas of concentrated poverty; if they are rebuilt as before, with poor-quality resources and little integration with more prosperous families, a wide range of social problems, including threats to mental health, will reappear. As we will describe in more detail, the hopelessness of individual poverty is compounded by community impoverishment.

The question addressed in this article is how psychological health, specifically depression, is affected by residence in a specific neighborhood, beyond the strains of low family income and other personal factors that heighten risk for depression. All of the studies summarized in this review examined the effects of neighborhood characteristics on depression after statistically eliminating the effects of individual and family characteristics, such as income, education, employment status, age, and race, that may increase personal vulnerability to depression.

WHAT IS A NEIGHBORHOOD?

Most often, neighborhoods are defined as census tracts. The U.S. Census works with local residents to identify meaningful neighborhood units when it decides on tract boundaries. A census tract typically has 4,000 to 6,000 people and includes approximately nine city blocks. Some researchers use smaller units, called block groups, which are smaller areas within census tracts. A few researchers use very small areas, called face blocks (both sides of the street for one block). The impact of neighborhood characteristics on mental health does not depend much on the neighborhood unit that is used in a particular study (Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, 2002).

NEIGHBORHOOD CHARACTERISTICS

Physical features of neighborhoods, such as quality of housing and the presence or absence of basic resources, including hospitals, reliable public transportation, and retail stores, can be important determinants of well-being. More research has been conducted on the influence of the people who live in neighborhoods than on the physical characteristics of neighborhoods. Two types of “person” characteristics have received research attention: structural and functional. Aspects of the population makeup of a neighborhood are termed structural characteristics. They include, but are not limited to, the percent of neighborhood residents who are poor, jobless, well-educated, or members of an ethnic minority group. Information about structural aspects of neighborhoods is almost always derived from the U.S. Census.

Aspects of how people in a neighborhood behave are termed functional characteristics. Examples of negative functional characteristics include the extent to which neighborhood residents behave in an uncivil or threatening manner and tolerate or engage in unlawful behavior (“social disorder”). Although not everyone in the neighborhood may engage in a specific behavior, if the behavior is sufficiently prevalent and affects a large number of residents, it may be viewed as a functional characteristic of that neighborhood. Functional characteristics are assessed through surveys of neighborhood residents or by systematic observation by researchers (e.g., counting the number of teenagers who hang out on the street late at night).

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

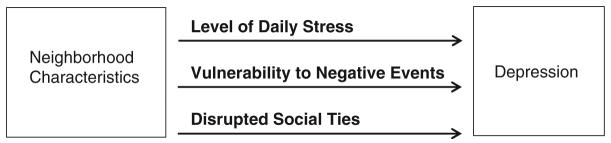

Stress plays a central role in theories that link neighborhood characteristics and depression. Characteristics of the neighborhoods in which people live influence the stress process in three different ways (see Fig. 1). First, neighborhood characteristics influence the level of daily stress imposed upon residents. Second, neighborhood characteristics influence people's vulnerability to depression following negative events in their lives (Elliott, 2000). In a highly adverse neighborhood, the same event is more likely to trigger depression than in a good-quality neighborhood. Third, neighborhood characteristics interfere with the formation of bonds among people. In turn, disrupted bonds lead to depression through several different pathways including lower levels of informal social control, inadequate social support, and poor family-role performance.

Fig. 1.

Three pathways from neighborhood characteristics to depression.

Daily Level of Stress

Neighborhood stressors may be imposed by physical characteristics of the neighborhood (e.g., lack of resources and unpleasant physical surroundings) or by the people who inhabit the neighborhood (e.g., threats to physical safety).

Lack of Resources and Physical Stressors

Many physical features of high-poverty neighborhoods impose stress on the lives of their residents, including low-quality housing, high traffic density, and undesirable commercial operations (e.g., adult bookstores). Observer ratings of housing quality predicted depression beyond the effects of family income in a study of low- and middle-income rural women (Evans, Wells, Chan, & Saltzman, 2000). Furthermore, women who moved from poor-quality apartments to single-family homes through Habitat for Humanity showed significant decreases in depressive symptoms (Evans et al., 2000). Low-income neighborhoods lack many resources, including health care, retail stores, and recreational facilities. Lack of access to needed resources is demoralizing because of the extra effort required to meet daily needs (Sampson et al., 2002). Very few studies have quantified neighborhood resources. More refined measures that capture type, accessibility, and distance to community resources are needed.

The People in the Neighborhood

A potent source of stress is fear of victimization (Hill, Ross, & Angel, 2005). There is evidence that social disorder, not poverty per se, is the neighborhood characteristic that most directly causes depression (Ross, 2000). People who live in neighborhoods with high rates of crime must cope with anxiety over their safety and that of their possessions. Neighborhood social disorder is associated with depressive symptoms in both children and adults (Aneshensel & Sucoff, 1996; Hill et al., 2000). By contrast, neighborhood poverty without social disorder does not show a consistent effect on depression in adults (Cutrona, Russell, Hessling, Brown, & Murry, 2000), although its effects on children appear to be more consistent (Xue, Leventhal, Brooks-Gunn, & Earls, 2005).

Vulnerability to Depression Following Negative Events

A second way that adverse neighborhoods engender depression is by intensifying the harmful mental health impact of negative events in people's lives (Cutrona et al., 2005). Someone who experiences a negative event (e.g., job loss) in a poor neighborhood is more likely to become depressed than is one who experiences the same event in a more advantaged neighborhood. Among African American women, all of whom had experienced at least one severe negative life event in the past year, only 2% of those who lived in low-stress neighborhoods experienced the onset of a major depressive episode, as compared to 12% of those who lived in high-stress neighborhoods. Reasons for this heightened vulnerability may include lack of resources, the absence of role models who provide hope for personal success, and local norms that promote ineffective coping and negative interpretations of events (Elliott, 2000).

Neighborhood Effects on Interpersonal Relationships

Neighborhood characteristics influence the probability that people will form ties with each other (Sampson et al., 2002). When residential turnover is high, people are less likely to form relationships. Similarly, people do not tend to form relationships when they live in neighborhoods high in social disorder, because they mistrust their neighbors (Hill et al., 2005). Relationship disruption may have several different consequences relevant to depression, including lower levels of informal social control, inadequate social support, and poor family-role performance.

Informal Social Control

When people do not know each other, they do not monitor or control each others' behavior, and norms that permit antisocial or maladaptive behavior may arise (Sampson et al., 2002). When people engage in maladaptive behavior, problems often result, such as job loss or unintended pregnancy, which in turn lead to depression. By contrast, in neighborhoods where people know and trust one another, they are more likely to discourage problem behaviors that might lead to depression (e.g., through disapproval, telling parents, alerting authorities, or forming neighborhood-watch groups).

Social Support

People who live in high-social-disorder neighborhoods have fewer ties with their neighbors and perceive their relationships with their closest friends and relatives as being less supportive than do people in better neighborhoods (Aneshensel & Sucoff, 1996), perhaps because support providers themselves are highly burdened. Residence in an economically disadvantaged neighborhood appears to weaken the protective power of social resources in people's lives. Among adolescents, a close supportive relationship with parents only protected against depression in higher-income neighborhoods, not in lower-income neighborhoods (Wickrama & Bryant, 2003). Similarly, among adults, frequent contact with friends and involvement in community organizations protected against depression in higher- but not in lower-income neighborhoods (Elliott, 2000).

Family-Role Performance

Some neighborhoods provide few role models for competent fulfillment of family roles; thus marriages and parenting processes may suffer, resulting in depression among both adults and children (Cutrona et al., 2003; Wickrama & Bryant, 2003). Neighborhood poverty predicted lower-quality parenting behaviors, including lower observed warmth, in parents of adolescents (Wickrama & Bryant, 2003). Poor parenting, in turn, predicted depression among the adolescents. In another observational study, residents of high-poverty neighborhoods behaved less warmly toward their spouses than residents of low-poverty neighborhoods did (Cutrona et al., 2003). Low warmth may lead to marital problems, which have been widely shown to predict depression.

DIFFERENCES IN REACTIONS TO NEIGHBORHOODS

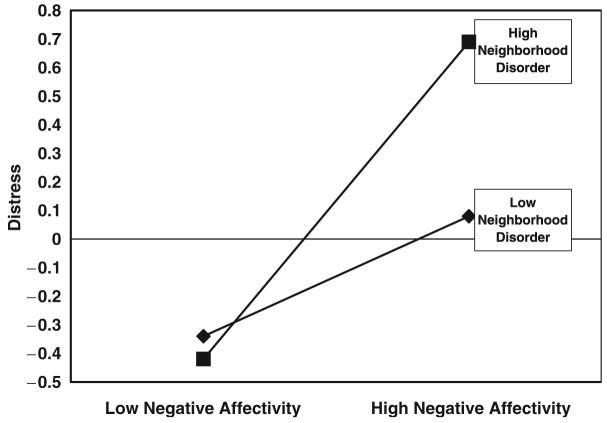

The impact of neighborhood characteristics on people's psychological adjustment varies noticeably, depending on people's personal traits and circumstances (Cutrona et al., 2000). In one study of women who lived in high-social-disorder neighborhoods, levels of distress were extremely high if the women were high on the personality trait of negative affectivity (a tendency to strong emotional reactions; see Fig. 2). By contrast, women who scored high on optimism and personal mastery were relatively immune to the negative mental health impact of neighborhood social disorder (Cutrona et al., 2000). Some people with particularly resilient personalities can cope successfully, even in dangerous and disorderly neighborhoods. However, other people are highly vulnerable to depression when they live in adverse surroundings. It may be that living in a disadvantaged and disorderly neighborhood eventually erodes optimism and replaces it with hopelessness and negativity.

Fig. 2.

Effect of neighborhood social disorder on distress for women high on negative affectivity versus for women low on negative affectivity. (Lines are plotted for 1 standard deviation above and one standard deviation below the sample mean on neighborhood social disorder; the y-axis is labeled in standard deviation units.) From “Direct and Moderating Effects of Community Context on the Psychological Well-Being of African American Women,” by C.E. Cutrona, D.W. Russell, R.M. Hessling, & P.A. Brown, 2000, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, p. 1097. Copyright 2000 by the American Psychological Association. Reprinted with permission.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The field of psychology has paid insufficient attention to the impact of contextual factors on well-being. Neighborhood context affects important psychological processes, above and beyond personal and family stressors, by increasing stress load, intensifying reactivity to negative life events, and damaging the quality of interpersonal relationships. Furthermore, psychological characteristics appear to moderate the impact of neighborhoods on adjustment. Some people with particularly resilient personalities cope effectively with neighborhood stressors, but others appear to be significantly harmed psychologically. The influence of contexts on a wide range of psychological processes merits further study.

Better methods for separating the mental health impact of people's personal characteristics from those of their neighborhoods are needed. Social experiments in which low-income people are given rent subsidies and randomly assigned to live in different kinds of neighborhoods have shown that youth and adults show better mental health when they move from impoverished neighborhoods to middle-class neighborhoods (e.g., Rosenbaum & Harris, 2001). These studies demonstrate clearly that some of the problems associated with low-income people should actually be attributed to low-income environments.

Duncan and Raudenbush (2001) offered a number of suggestions for how to improve the design of survey-based neighborhood studies. These include analyzing family characteristics that might mistakenly be attributed to neighborhoods; examining the similarity between siblings, neighbors, and non-neighbors on mental health outcomes to sort out the contributions of family characteristics from those of neighborhood characteristics; and using separate samples of neighborhood residents to obtain information about the neighborhood (e.g., degree of social disorder) and outcome measures (e.g., level of depression).

The most efficient way to improve mental health in impoverished neighborhoods is to improve the quality of neighborhoods. A number of projects are currently underway around the country to help residents of impoverished inner-city neighborhoods organize to improve the quality of life in their neighborhoods (e.g., Jason, 2006). Research is needed to determine the best strategies for empowering local residents to take effective action. Techniques are needed to study processes of change in neighborhoods and the factors that facilitate change.

Decisions about where to build subsidized housing for low-income families are critically important. There is evidence that economically integrated neighborhoods are beneficial and that concentrating low-income housing in the poorest neighborhoods perpetuates problems of social disorder and resource deprivation. As noted earlier, rebuilding New Orleans presents the opportunity to avoid concentrations of poverty, which breed hopelessness and depression as well as other social problems. It is important that policymakers have access to empirical data that will help them make informed decisions about housing and economic-development issues. Greater collaboration across the disciplines of city planning, economics, sociology, and psychology are needed in generating such data.

Recommended Reading

- Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood poverty, Vol. 1: Context and consequences for children. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jencks C, Mayer SE. The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighborhood. In: Lynn LE, McGeary MGH, editors. Adolescents at risk: Medical and social perspectives. Westview Press; Boulder, CO: 1990. pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Denton NA. American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. The stress process revisited: Reflections on concepts and their relationships. In: Aneshensel C, Phelan J, editors. Handbook of the sociology of mental health. Plenum Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. How do communities undergird or undermine human development? Relevant contexts and social mechanisms. In: Booth A, Crouter AC, editors. Does it take a village? Community effects on children, adolescents, and families. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

REFERENCES

- Aneshensel C, Sucoff CA. The neighborhood context of adolescent mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1996;37:293–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell DW, Abraham WT, Gardner KA, Melby JN, Bryant C, Conger RD. Neighborhood context and financial strain as predictors of marital interaction and marital quality in African American couples. Personal Relationships. 2003;10:389–409. doi: 10.1111/1475-6811.00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell DW, Brown PA, Clark LA, Hessling RM, Gardner KA. Neighborhood context, personality, and stressful life events as predictors of depression among African American women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:3–15. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell DW, Hessling RM, Brown PA, Murry V. Direct and moderating effects of community context on the psychological well-being of African American women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:1088–1101. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.6.1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Raudenbush SW. Neighborhoods and adolescent development: How can we determine the links? In: Booth A, Crouter AC, editors. Does it take a village? Community effects on children, adolescents, and families. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. pp. 105–136. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott M. The stress process in neighborhood context. Health & Place. 2000;6:287–299. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(00)00010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Wells NM, Chan HYE, Saltzman H. Housing quality and mental health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:526–530. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.3.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill TD, Ross CE, Angel RJ. Neighborhood disorder, psychophysiological distress, and health. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 2005;46:170–186. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA. Benefits and challenges of generating community participation. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2006;37:132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence upon child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JE, Harris LE. Low-income families in their new neighborhoods. Journal of Family Issues. 2001;22:183–210. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE. Neighborhood disadvantage and adult depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:177–187. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley, T. Assessing “Neighborhood Effects”: Social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology. 2002;28:443–478. [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama KAS, Bryant CM. Community context of social resources and adolescent mental health. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65:850–866. [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J, Earls FJ. Neighborhood residence and mental health problems of 5- to 11-year-olds. Archives of Genetic Psychiatry. 2005;62:554–563. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]