Abstract

A series of hairpin pyrrole–imidazole polyamide–fluorescein conjugates were synthesized and assayed for cellular localization. Thirteen cell lines, representing 11 human cancers, one human transformed kidney cell line, and one murine leukemia cell line, were treated with 5 μM polyamide–fluorescein conjugates for 10–14 h, then imaged by confocal laser scanning microscopy. A conjugate containing a β-alanine residue at the C terminus of the polyamide moiety showed no nuclear localization, whereas an analogous compound lacking the β-alanine residue was strongly localized in the nuclei of all cell lines tested. The localization profiles of several other conjugates suggest that pyrrole–imidazole sequence and content, dye choice and position, linker composition, and molecular weight are determinants of nuclear localization. The attachment of fluorescein to the C terminus of a hairpin polyamide results in an ≈10-fold reduction in DNA-binding affinity, with no loss of binding specificity with reference to mismatch binding sites.

Small molecules that preferentially bind to predetermined DNA sequences inside living cells would be useful tools in molecular biology, and perhaps human medicine. The effectiveness of these small molecules requires not only that they bind to chromosomal DNA site-specifically, but also that they be permeable to the outer membrane and gain access to the nucleus of living cells. Polyamides containing the aromatic amino acids N-methylpyrrole (Py), N-methylimidazole (Im), and N-methyl-3-hydroxypyrrole (Hp) bind DNA with affinities and specificities comparable to naturally occurring DNA-binding proteins (1, 2). A set of pairing rules describes the interactions between pairs of these heterocyclic rings and Watson–Crick base pairs within the minor groove: Im/Py is specific for G·C, Hp/Py is specific for T·A and Py/Py binds both A·T and T·A. Exploitation of polyamides to target sequences of biological interest has yielded results in a number of cell-free systems (3–8).

Extension of these in vitro biological results to cellular systems has proven to be cell-type dependent. Polyamides exhibited biological effects in primary human lymphocytes (9), human cultured cell lines (10), and when fed to Drosophila embryos (11, 12). However, attempts to inhibit the transcription of endogenous genes in cell lines other than insect or T lymphocytes have met with little success. For example, polyamides that downregulate transcription of the HER2/neu gene in cell-free experiments display no activity in HER2-overexpressing SK-BR-3 cells (13).

To determine whether these results were caused by poor cellular uptake or nuclear localization, a series of polyamides incorporating the fluorophore Bodipy FL was synthesized. Intracellular distribution of these molecules in several cell lines was then determined by confocal laser scanning microscopy (14). Cells that demonstrated robust responses to polyamides, such as T lymphocyte derivatives, showed staining throughout the cells, including the nucleus. In other cell lines studied, however, treatment with polyamide–Bodipy conjugates produced a punctate staining pattern in the cytoplasm, with no observable signal in the nuclei. Bashkin and coworkers (15) recently reported that an eight-ring polyamide–Bodipy conjugate colocalized with LysoTracker Red DND 99 (a lysosome and trans-Golgi stain, 23) in several cell lines, indicating that the punctate staining pattern was presumably caused by trapping of the polyamide in acidic vesicles. In contrast, an eight-ring polyamide–fluorescein conjugate, 1, was shown to accumulate in the nuclei of HCT-116 human colon cancer cells.

We have found that a similar eight-ring polyamide–fluorescein conjugate, 2, with a single Py to Im change, is excluded from the nuclei of 13 different mammalian cell lines, whereas removal of the β-Ala residue in the linker, affording 3, enables nuclear localization in all of these cell lines, with no obvious toxicity. This raises the issue: what are the molecular determinants (fluorophore, position of attachment, linker composition, polyamide sequence and size) of uptake and nuclear localization in cultured cells? Understanding nuclear accessibility in a wide variety of living cells is a minimum first step toward chemical regulation of gene expression with this class of molecules. A further issue will be whether polyamides modified for optimal cellular and nuclear uptake retain favorable DNA-binding affinity and sequence specificity. We have synthesized 22 polyamide–fluorophore conjugates with incremental changes in structure and examined their intracellular distribution in thirteen cell lines.

Materials and Methods

For more details, see Supporting Materials and Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org.

Chemicals. Polyamides 1 and 2 were prepared by solid phase methods on Boc-β-alanine-PAM-resin (Peptides International, Louisville, KY) (16). All other polyamides were synthesized by solid phase methods on the Kaiser oxime resin (Nova Biochem, Laufelfingen, Switzerland) (17). After cleavage with the appropriate amine and reverse-phase HPLC purification, polyamides were allowed to react at room temperature for ≈3 h at ≈0.01 M in N,N-dimethylformamide with FITC (compounds 1-3 and 5-22) or the N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester of BODIPY-FL (4), as well as 20 eq of Hünig's base, to yield polyamide dye conjugates. The purity and identity of the dye conjugates were verified by analytical HPLC, UV-visible spectroscopy, and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization/time-of-flight mass spectrometry. All fluorescent dye reagents were from Molecular Probes. Chemicals not otherwise specified were from Sigma.

Confocal Microscopy. Adherent cell lines were trypsinized for 5–10 min at 37°C, centrifuged for 5 min at 5°C at 2,000 rpm in a Beckman-Coulter Allegra 6R centrifuge, and resuspended in fresh medium to a concentration of 1.25 × 106 cells per ml. Suspended cell lines were centrifuged and resuspended in fresh medium to the same concentration. Incubations were performed by adding 150 μl of cells into culture dishes equipped with glass bottoms for direct imaging (MatTek, Loveland, OH). Adherent cells were grown in the glass-bottom culture dishes for 24 h. The medium was then removed and replaced with 142.5 μl of fresh medium. Then 7.5 μl of the 100 μM polyamide solution was added and the cells were incubated in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C for 10–14 h. Suspended cell line samples were prepared in a similar fashion, omitting trypsinization. These samples were then incubated as above for 10–14 h. Imaging was performed with a ×40 oil-immersion objective lens on a Zeiss LSM 510 META NLO laser scanning microscope with a Coherent Chameleon 2-photon laser, or on a Zeiss LSM 5 Pascal inverted laser scanning microscope.

Energy Dependence Experiments. Inhibitory medium was prepared by supplementing glucose- and sodium pyruvate-free DMEM (Gibco catalog no. 1196025) with 2-deoxyglucose (6 mM) and sodium azide (10 mM) (18). Cells were grown, trypsinized, resuspended, plated, and incubated as above. After 24 h of growth at 37°C in 5% CO2, the medium was removed and replaced with either 142.5 μl of fresh normal DMEM or 142.5 μl of inhibitory DMEM. The cells were incubated for 30 min, then treated with 7.5 μl of 100 μM compound 3. The cells were then incubated for 1 h, followed by confocal imaging as above. Samples in inhibitory medium were then treated by removal of the medium, washing, and removal of 200 μl of normal medium, replacement with 142.5 μl of normal medium and addition of 7.5 μlof100 μM compound 3. These samples were incubated for 1 h and then imaged once more.

DNase I Footprinting Titration Experiments. A3′ 32P-labeled restriction fragment from the plasmid pDEH9 was generated in accordance with standard protocols and isolated by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis (19, 20).

Results

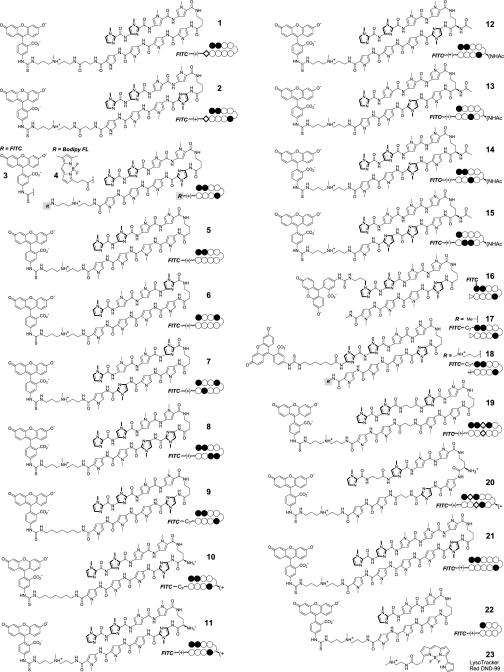

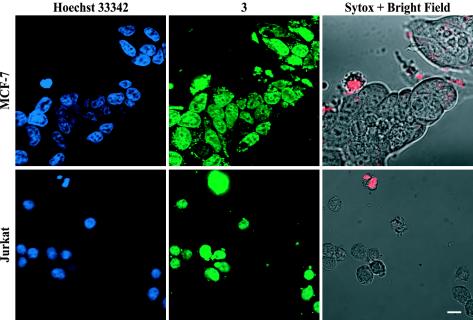

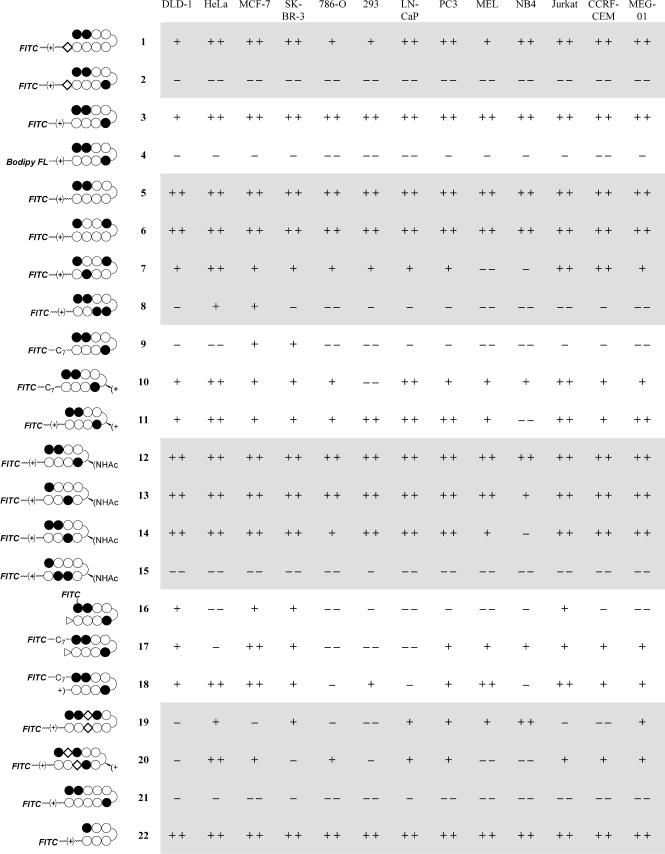

Structures for all of the compounds synthesized are listed in Fig. 1. Sample images for compounds 2 and 3 in two cell lines are shown in Fig. 2. To show that compound 3 localizes to the nuclei of live cells, samples were treated with 3, the nuclear stain Hoechst dye 33342, and the dead-cell stain Sytox Orange (Fig. 3). The uptake characteristics of compounds 1-22 were examined in 13 cell lines by confocal microscopy, and each sample was rated qualitatively for the extent of nuclear localization (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

Structures of compounds 1–22, which were synthesized for this work, and compound 23, which was purchased from Molecular Probes.

Fig. 2.

Cellular localization of polyamide–fluorescein conjugates. (Upper) Adherent MCF-7 cells were treated with compound 2 (Upper Left)or 3 (Upper Right) for 10–14 h at 5 μM. Compound 2 was excluded from the cells entirely, whereas compound 3 localized to the nucleus. (Bottom) Suspended Jurkat cells were similarly treated and show similar results. (Scale bar = 10 μm.)

Fig. 3.

Colocalization of polyamide 3 and Hoechst in live cells, imaged by using sequential single- and two-photon excitation. (Upper) MCF-7 cells were treated with the nuclear stain Hoechst dye 33342 (15 μM), compound 3 (5 μM), and the dead cell stain Sytox Orange (0.5 μM). Fluorescence signals from Hoechst (Upper Left, blue) and compound 3 (Upper Center, green) colocalize in cell nuclei. (Upper Right) Overlay of the visible light image (grayscale) and the Sytox Orange fluorescence image (red), indicating that the majority of cells are alive. (Lower) Jurkat cells were treated similarly and show similar results. (Scale bar = 10 μm.)

Fig. 4.

Uptake profile of compounds 1–22 in 13 cell lines. + +, Nuclear staining exceeds that of the medium; +, nuclear staining less than or equal to that of the medium, but still prominent; -, very little nuclear staining, with the most fluorescence seen in the cytoplasm and/or medium; --, no nuclear staining.

The molecules showing the highest degree of nuclear uptake in most cell lines stained nuclei very brightly with reference to the background fluorescence caused by fluorescent agent in the medium. Agents 1, 3, 5, 6, 11-14, and 22 showed such high levels of uptake in many cell lines. Many compounds exhibited a very scattered uptake profile in the series of cells studied, and compounds 2, 4, 15, and 21 showed no significant nuclear staining in any cell line. Of the entries in Fig. 4 indicating poor nuclear uptake properties, most reflect lysosomal staining, as indicated by costaining with LysoTracker Red DND-99, as well as fluoresence in the intercellular medium. Only compound 2 was found exclusively in the medium, showing no uptake in cells.

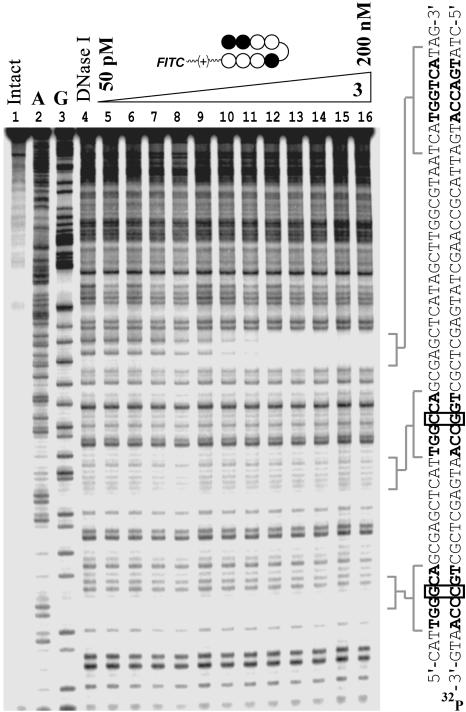

The DNA-binding properties of 3 were assessed by DNase I footprinting titrations on the plasmid pDEH9, which bears the 5′-TGGTCA-3′ match site and discrete single base pair mismatch sites. Conjugate 3 bound to the match site with a Ka of 1.6 (±0.3) × 109 M-1, and showed specificity over mismatch sites by >100-fold (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Fig. 5.

Quantitative DNase I footprinting titration. Compound 3 binds the 3′-TGGTCA-5′ site with Ka = 1.6 (±0.3) × 109 M-1. Compound 3 does not bind the single base pair mismatch sites shown at concentrations ≤200 nM.

To investigate the energy dependence of the cellular uptake mechanism of compound 3, HeLa cells growing under normal conditions were incubated for 30 min in either normal DMEM or inhibitory DMEM, then treated with 3 for 1 h before confocal imaging (see Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The cells growing in normal medium showed clear nuclear staining, whereas the cells growing in inhibitory medium displayed very little to no discernable staining. Subsequent washing and replacement of the inhibitory medium with normal medium (supplemented with 5 μM 3), resulted in nuclear staining after 1 h, comparable to that seen in the sample grown continuously in the normal medium.

It had been shown previously that polyamide–Bodipy conjugates stain the nuclei of T lymphocytes, but no other cell type tested, and most commonly produced a punctate cytoplasmic staining pattern (14). Our studies indicated that a polyamide–fluorescein conjugate, 2, uniformly proved refractory to nuclear uptake in several human cancer cell lines. Elimination of the β-alanine residue at the C terminus of the polyamide afforded compound 3, which, surprisingly, showed excellent nuclear staining properties in the cell lines examined. Attachment of the Bodipy-FL fluorophore to the polyamide precursor of compound 3 provided compound 4. This molecule showed no nuclear staining, sequestering itself in cytoplasmic vesicles, indicating that some characteristic of polyamide–Bodipy conjugates differing from that of polyamide–FITC conjugates, and not the C-terminal β-alanine, prevents their trafficking into the nucleus. It is interesting to note that the structure of LysoTracker Red DND-99 (23) includes both a tertiary alkyl amine, similar to that often used in hairpin polyamide tails, and a Bodipy moiety.

It became our intent to explore the structure-space of polyamide–fluorophore conjugates to overcome cellular exclusion and lysosomal trapping, allowing the polyamides to travel to the nucleus. To explore the criteria that permit uptake of 3, and that prevent that of 4, several variations on the structure of the compound were made and their effects were determined by confocal microscopy.

Wishing to explore the effect of Py/Im sequence and content of hairpin polyamides on cellular trafficking, we synthesized compounds 5-8. Compounds 5 and 6, both containing two imidazole residues, showed a high degree of nuclear staining in all cell lines studied. Three-imidazole compound 7 showed intermediate levels of nuclear staining in the cell lines studied. The nuclear localization of four-imidazole compound 8 was quite poor in all cell lines tested. The difference in nuclear staining levels exhibited by compounds 3 and 7 shows that Py/Im sequence alone is an important determinant of nuclear uptake, although overall content (in terms of the number of Py and Im residues) may also be a factor.

To explore the effect of the positively charged linker on nuclear uptake, compound 9 was synthesized. This agent showed nearly global abrogation of nuclear uptake efficiency versus the analog containing a tertiary amine. Further, substitution of the γ-aminobutyric acid turn (γ-turn) of 9 with the [(R)-α-amino]-γ-diaminobutyric acid turn (H2Nγ-turn) provided 10, which restored most of the nuclear uptake properties of 3. This finding suggests that the overall charge of the molecule, and perhaps the placement of that charge, are important variables in nuclear uptake of polyamide dye conjugates.

The H2Nγ-turn is a structural element commonly included in polyamide design. Replacement of the γ-turn of 3 with the H2Nγ-turn provided 11. This molecule showed nuclear staining in all cell lines tested, save NB4, although often to a lesser degree than 3. It is unclear whether this reduction in uptake efficiency is caused by an increase in the overall positive charge of the molecule, a more branched structure than the linear γ-linked hairpin, or the positioning of a positive charge medial in the molecule.

Selective acetylation of the polyamide precursor to 11, followed by FITC conjugation, provided 12. This molecule exhibited excellent nuclear uptake, as good or better than both 11 and 3. The excellent uptake of 12 argues against branching as a negative determinant of nuclear staining. This result also prompted us to synthesize 13-15 to probe the generality and flexibility of turn acetylation across several polyamide sequences. The uptake of 13 and 14 was mostly nuclear. Compound 15, on the other hand, was a very poor nuclear stain. This result reaffirms the importance of polyamide sequence on nuclear uptake.

We next synthesized several conjugates to explore the uptake effects of different points of attachment of the fluorophorelinker moiety to the polyamide. An N-propylamine linkage from the terminal imidazole and a methylamide tail were incorporated into 16, which showed poor nuclear uptake in nearly all cell lines tested. We thought it possible that the poor uptake properties of conjugate 16 was caused by some nonlinearity introduced into the overall structure of the molecule by the linkage at the 1-position of the N-terminal ring of the polyamide. Consequently, conjugates 17 and 18 were synthesized, appending the linker–fluorophore moiety to the N-terminal amine. Although compound 17 has an overall structure and charge distribution very similar to that of 9, it possesses better nuclear uptake properties, particularly in suspended cell lines. Subsequent addition of a positive charge at the C terminus of the polyamide through employment of an N,N-dimethylaminopropylamine tail (compound 18) boosts uptake in all cell lines studied, except NB4. Once again, this suggests that the addition or deletion of a single charge may (but not necessarily will) have a strong effect on nuclear uptake. In fact, a comparison of compounds 3, 10, and 18 (differing in the placement of a positive charge) with 9 and 17 (which lack a positive charge) seems to indicate that the positioning of this charge is less influential than its presence.

Another common structural feature used in DNA-binding polyamides is the addition of one or more β-alanine residues. This amino acid is often used to relax overcurvature of a polyamide backbone with reference to the minor groove of DNA and permits the targeting of longer sequences than that of eight-ring hairpins. Compound 19, which includes this structural element, and 20, which includes both β-alanines and the H2Nγ-turn, showed fair to poor nuclear uptake in the cell line series. The reduced uptake levels could be caused by the increased molecular flexibility imparted by the β-alanine residues, increased molecular weight, decreased recognition by a cellular import protein, or some combination of these criteria.

To determine whether the added size imparted to 19 and 20 by the β-alanine residues was likely a major contributor to their poor uptake, the 10-ring compound 21 was synthesized. Its ubiquitously poor nuclear uptake suggests that molecular weight may, indeed, play a prominent role in uptake character. The excellent uptake character of the 6-ring compound 22 furthers this hypothesis, although Py/Im sequence in the 6-ring and 10-ring contexts is also likely to be important.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the cellular localization profile of a host of polyamide dye conjugates in a wide variety of cell lines. In general, compounds exhibiting good nuclear uptake properties have several common elements: an eight-ring polyamide DNA-binding domain, one or more positive charges incorporated within either the linker or the turn residue, and a conjugated fluorescein fluorophore. This study also demonstrates that each cell line possesses a unique uptake profile for the panel of compounds presented to it. These profiles will be important in choosing a cell line and compound architecture appropriate to a given experiment.

Conjugation of the fluorophore to the polyamide DNA-recognition domain results in an ≈10-fold reduction in DNA-binding affinity as compared with the parent polyamide, with retention of binding specificity over mismatch sites. This quality, along with the nuclear uptake results, suggests that fluorophoreconjugated polyamides may be used directly in experiments designed to take place in living mammalian cells.

Clearly, there are many criteria at work, each one having its share of influence on nuclear uptake of polyamide dye conjugates. The extension of the structure–space of compounds known to both bind chromosomal DNA specifically and with high affinity, as well as to traffic to the nucleus of living cells is the object of current investigations. The illumination of these possibilities will permit the further study of transcriptional regulation in living systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Waring for helpful discussions. We are grateful to the National Institutes of Health for support (Grant GM57148) and for predoctoral support to T.P.B. (Grant T32-GM08501) and to the Howard Hughes Medical Institute for a fellowship to B.S.E. Mass spectral analyses were performed in the Mass Spectrometry Laboratory of the Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering of Caltech, supported in part by National Science Foundation Materials Research Science and Engineering program.

Abbreviations: Py, N-methylpyrrole; Im, N-methylimidazole.

References

- 1.Dervan, P. B. & Edelson, B. S. (2003) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 13, 284–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dervan, P. B. (2001) Bioorg. Med. Chem. 9, 2215–2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickinson, L. A., Trauger, J. W., Baird, E. E., Ghazal, P., Dervan, P. B. & Gottesfeld, J. M. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 10801–10807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gottesfeld, J. M., Turner, J. M. & Dervan, P. B. (2000) Gene Expression 9, 77–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang, C. C. C. & Dervan, P. B. (2001) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 8657–8661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ansari, A. Z., Mapp, A. K., Nguyen, D. H., Dervan, P. B. & Ptashne, M. (2001) Chem. Biol. 8, 583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottesfeld, J. M., Melander, C., Suto, R. K., Raviol, H., Luger, K. & Dervan, P. B. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 309, 615–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehley, J. A., Melander, C., Herman, D., Baird, E. E., Ferguson, H. A., Goodrich, J. A., Dervan, P. B. & Gottesfeld, J. M. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 1723–1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickinson, L. A., Gulizia, R. J., Trauger, J. W., Baird, E. E., Mosier, D. E., Gottesfeld, J. M. & Dervan, P. B. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 12890–12895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coull, J. J., He, G. C., Melander, C., Rucker, V. C., Dervan, P. B. & Margolis, D. M. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 12349–12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janssen, S., Durussel, T. & Laemmli, U. K. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 999–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janssen, S., Cuvier, O., Muller, M. & Laemmli, U. K. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 1013–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiang, S. Y., Bürli, R. W., Benz, C. C., Gawron, L., Scott, G. K., Dervan, P. B. & Beerman, T. A. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 24246–24254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belitsky, J. M., Leslie, S. J., Arora, P. S., Beerman, T. A. & Dervan, P. B. (2002) Bioorg. Med. Chem. 10, 3313–3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crowley, K. S., Phillion, D. P., Woodard, S. S., Schweitzer, B. A., Singh, M., Shabany, H., Burnette, B., Hippenmeyer, P., Heitmeier, M. & Bashkin, J. K. (2003) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 13, 1565–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baird, E. E. & Dervan, P. B. (1996) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 6141–6146. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belitsky, J. M., Nguyen, D. H., Wurtz, N. R. & Dervan, P. B. (2002) Bioorg. Med. Chem. 10, 2767–2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richardson, W. D., Mills, A. D., Dilworth, S. M., Laskey, R. A. & Dingwall, C. (1988) Cell 52, 655–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heckel, A. & Dervan, P. B. (2003) Chem. Eur. J. 9, 3353–3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trauger, J. W. & Dervan, P. B. (2001) Methods Enzymol. 340, 450–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.