Abstract

Brachydactyly (BD) type A2 is an autosomal dominant hand malformation characterized by shortening and lateral deviation of the index fingers and, to a variable degree, shortening and deviation of the first and second toes. We performed linkage analysis in two unrelated German families and mapped a locus for BD type A2 to 4q21-q25. This interval includes the gene bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1B (BMPR1B), a type I transmembrane serinethreonine kinase. In one family, we identified a T599 → A mutation changing an isoleucine into a lysine residue (I200K) within the glycine/serine (GS) domain of BMPR1B, a region involved in phosphorylation of the receptor. In the other family we identified a C1456 → T mutation leading to an arginine-to-tryptophan amino acid change (R486W) in a highly conserved region C-terminal of the BMPR1B kinase domain. An in vitro kinase assay showed that the I200K mutation is kinase-deficient, whereas the R486W mutation has normal kinase activity, indicating a different pathogenic mechanism. Functional analyses with a micromass culture system revealed a strong inhibition of chondrogenesis by both mutant receptors. Overexpression of mutant chBmpR1b in vivo in chick embryos by using a retroviral system resulted either in a BD phenotype with shortening and/or missing phalanges similar to the human phenotype or in severe hypoplasia of the entire limb. These findings imply that both mutations identified in human BMPR1B affect cartilage formation in a dominant-negative manner.

Brachydactylies (BDs) are a group of inherited malformations characterized by shortening of the digits due to abnormal development of the phalanges and/or the metacarpals. They have been classified on an anatomic and genetic basis into five groups, A–E, including three subgroups (A1–A3) that usually manifest as autosomal dominant traits (1). BD type A2 (BDA2) was described first by Mohr and Wried (2) in a large Norwegian kindred. Thus far, the causative gene for BDA2 has not been found. Other BDs, however, have been characterized on the molecular level. BDA1 shows hypoplasia/aplasia of all middle phalanges, sometimes with joint fusions between the middle and the proximal phalanx. BDA1 is caused by mutations in Indian hedgehog, a signaling molecule with pivotal roles in the regulation of chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation (3). Characteristics of BDB are aplasia/hypoplasia of the terminal phalanges and nails. Symphalangism, especially of the distal joints, occurs. BDB is caused by truncating mutations located in two distinct regions of the receptor tyrosine kinase ROR2 (4, 5). BDC is characterized by brachymesophalangia of the second, third, and fifth fingers, sometimes together with hyperphalangia, usually of the second and third fingers. Heterozygous frameshift or nonsense mutations affecting growth/differentiation factor 5 (GDF5), a signal protein of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) family, have been identified in several individuals with BDC (6). Thus, BD types A–C have certain overlapping features including hypoplasia/aplasia of phalanges and abnormal interdigital joint formation, suggesting that the formation of joints and phalanges are linked on a developmental and molecular basis.

Development of the digital rays starts with the condensation of mesenchymal precursor cells according to a genetically determined pattern. Cells within the condensations differentiate into chondrocytes to form the anlage, a cartilaginous template of the future bone. Growth occurs mainly at the distal ends where new cells are recruited into the anlage. The digital rays are thought to be formed from spatially continuous prechondrogenic condensations that subsequently segment into individual skeletal elements, i.e., the phalanges and the metacarpals. Segmentation of the skeletal anlagen occurs according to a preset pattern involving the condensation of cells at the future joint, the formation of a joint cavity, and the formation of a synovia and a joint capsule. Chondrocytes within the cartilaginous anlage differentiate, and cartilage calcifies and then is removed by osteoclasts and replaced by bone, a process termed endochondral ossification.

Patterning, condensation, and differentiation are controlled by a molecular network involving a multitude of signaling pathways. One of the most prominent is the BMP/transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) pathway, which plays a central role in skeletal development. Proteins that are structurally similar to TGF-β are collectively referred to as the TGF-β superfamily. More than 30 such proteins exist in mammals. To date, at least 12 different BMPs and 8 different members of the GDFs, which also belong to this family, have been described. BMP2 and BMP4, the prototype of the BMPs, induce bone and cartilage in vivo and in vitro. GDF5, the most prominent member of the GDFs, was shown to play a vital role in the differentiation of chondrocytes and the formation of joints (7, 8). The capacity of BMPs to elicit bone formation has important clinical implications in, for example, the treatment of segmental bone defects or improving fracture healing (9).

Signaling of the TGF-β superfamily members requires binding of ligands to cell surface receptors consisting of two kinds of transmembrane serine-threonine kinase receptors classified as types I and II. These receptors form homodimeric and heterodimeric complexes on the cell surface consisting of types I and II receptor monomers (10). Two BMP type I receptors (BMPR1A and BMPR1B) and one type II receptor (BMPR2) are presently known. Ligand binding results in transphosphorylation of the type I by the type II receptor. Activated BMPR1s transduce signals to the nucleus and finally control the transcription of target genes mainly by phosphorylating members of the Smad family of transcriptional activators (11, 12). The importance of this signaling pathway for human disease is exemplified by the presence of germ-line and somatic mutations in several TGF-β-related genes. Mutations in BMPR2, for example, cause primary pulmonal hypertension (13), whereas mutations in BMPR1A are the cause of hereditary juvenile polyposis coli (14). Somatic mutations disabling a component of the TGF-β signaling pathway have been identified in many different types of cancer and are involved in the majority of colon and pancreatic cancers (for review see ref. 15).

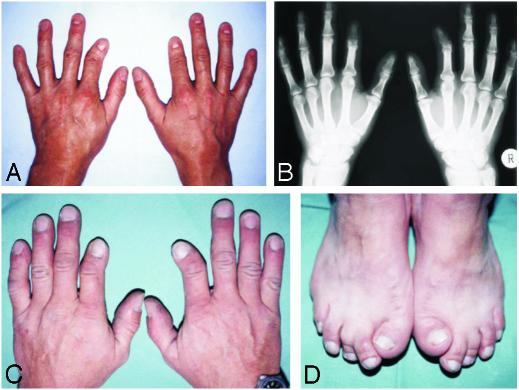

In this article we describe the molecular cause of BDA2, a hand malformation characterized by hypoplasia/aplasia of the middle phalanx of the second and sometimes the fifth fingers (Fig. 1). We show that BDA2 is caused by mutations in BMPR1B and demonstrate that these mutations function as dominant negatives in vitro and in vivo.

Fig. 1.

Phenotype of BDA2. (A and C) Short and medially deviated second fingers and clinodactyly of the fifth fingers. (B) Radiograph of the triangular-shaped middle phalanx of the second finger (Right) and missing middle phalanx of the second finger (Left). (D) Short, broad, and laterally deviated first toe and medial deviation of the second toe. The pictures were taken from persons A–D as indicated in Fig. 2.

Subjects, Materials, and Methods

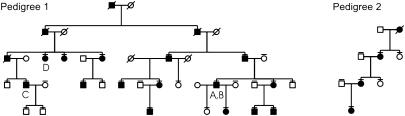

Patients. Two unrelated German families with BDA2 were investigated. The pedigrees are shown in Fig. 2. Affected and unaffected individuals were clinically examined, and select affected individuals were radiographed. All affected individuals had the characteristic BDA2 hand phenotype consisting of medially deviated or shortened index fingers (Fig. 1). Approximately half of them also had foot involvement such as deviation and shortening of the first or second toes, cutaneous syndactyly between the second and third toes, and camptodactyly. We did not observe any family-specific phenotypes between the two families or sex-correlated characteristics. All participants gave informed consent.

Fig. 2.

BDA2 pedigrees. Affected persons are indicated by filled symbols. Overlined symbols indicate individuals who underwent clinical examination and mutation analysis.

Linkage Analysis. DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples/buccal swabs by standard methods. A genomewide scan with a set of 395 polymorphic microsatellite markers (modified Weber9 set, Marshfield Institute, Marshfield, WI), with an average spacing of ≈11 centimorgans according to the Marshfield map, was performed. Additional markers were used for the fine mapping. Products of PCR assays with fluorescently labeled primers were analyzed by automated capillary genotyping on MegaBACE 1000 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). A two-point linkage analysis was performed by using the linkage 5.20 package and assuming an autosomal dominant model of disease inheritance with a disease allele frequency of 0.0001 and equal female and male recombination rates. Haplotypes were reconstructed by simwalk2 2.82 and genehunter 1.3.

Mutation Analysis. Focusing on BMPR1B, which is known to have two alternative transcript variants (16), we amplified the coding region of the BMPR1B variant expressed in the limb, composed of 10 exons (17). Standard protocol PCRs were carried out to amplify exons 1–10 (see Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org, for primer sequences). PCR products were analyzed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Purified PCR products were sequenced in both directions by using PCR primers as sequencing primers and the Applied Biosystems Prism BigDye terminator cycle sequencing reaction kit. The products were evaluated on an Applied Biosystems 3100 DNA sequencer.

Micromass Cultures. Fertilized chicken eggs were obtained from Charles River Breeding Laboratories and incubated at 37.5°C in a humidified egg incubator for ≈4.5 days. Limb buds of Hamburger/Hamilton stage 23/24 (18) were isolated as described (19). Ectoderm was removed by incubation with dispase (3 mg/ml), and cells were isolated from the limb buds by digestion with 0.1% collagenase type Ia and 0.1% trypsin. Micromass cultures were plated at a density of 2 × 105 cells per 10-μl drop in the middle of a 24-well tissue-culture plate. Infection was performed with 1 μl of the concentrated RCAS viral supernatants, as described (20), containing the cDNA encoding WT chick (ch)BmpR1b, I200K chBmpR1b, or R486W chBmpR1b. As a control RCAS–enhanced GFP was used. Cells were allowed to attach for 2 h in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C and then complemented with DMEM-F12 culture medium supplemented with 10% FBS/0.2% chicken serum/l-glutamine/penicillin (100 units/ml)/streptomycin (100 μg/ml). The culture medium was replaced every 2 days. Micromass cultures were stained with Alcian blue at days 5 and 6 as described (19). Quantification of the staining was achieved by extraction with 6 M guanidine hydrochloride for 8 h at room temperature (RT). Dye concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at A650. A standard dilution curve was recorded in a range of OD 0–2.5 at A650. Linearity of the signal was given over the complete standard curve.

Construct Design and Retroviral Infection of Chicken Limbs. chBmpR1b was used as a template for generating the mutations I200K and R486W corresponding to the human mutations. In addition, the Q249R mutation described in association with increased ovulation rate in Booroola Mérino ewes (21) was introduced into the chBmpR1b. Mutagenesis was performed with the GeneEditor Kit (Promega) by using the primers I200K-R (5′-CATCTGAATCTGTTTTGCTTTGGTCCTTTGAACCAGGAGAG-3′), R486W-R (5′-GCAAGTGTTTTTTTGACCCATAGGGCTGTGAGTCGGGATGC-3′), and Q249R-R (5′-GAATATTTTCATGCCTCATCAGGACAGTACGGTAGATTTCTGTTT-3′) (mutant positions are underlined) according to manufacturer recommendations. Production of concentrated viral supernatant and injection into the limb field of Hamburger/Hamilton stage 10 chicken embryos was performed as described (22). Embryos were harvested at Hamburger/Hamilton stage 34/35 and stained with Alcian blue to visualize cartilage.

Immunocytochemistry. COS7 cells grown on glass coverslips were transfected with hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged mouse BmpR1b in pcDNA3 as described (10) by using Polyfect (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Cells were washed twice with serum-free DMEM 48 h after transfection and incubated for 1 h at 37°C to allow endocytosis of ligand-bound receptors. After washing with PBS, cells were fixed for 15 min at RT in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and washed three more times with PBS. To block nonspecific binding, cells were incubated in 10% FCS in PBS for 45 min at RT. This was followed by incubation with anti-HA rabbit (Sigma, 1:100) at RT for 1 h. Detection was achieved after extensive washings by incubation with anti-rabbit-Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes, 1:1,000). Cells were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories). Fluorescence digital images were recorded with a LSM510 Axioplan2 microscope (Zeiss).

Immunoprecipitation and in Vitro Kinase Assay. COS7 cells were transiently transfected with HA-tagged mouse BmpR1b constructs as described (10). Two days posttransfection, cells were washed twice with ice-cold Tris-buffered saline (TBS) and lysed in 20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5/150 mM NaCl/1% Nonidet P-40/2 mM CaCl2/2 mM MgCl2/10 mM NaF/10 mM Na3VO4 and protease inhibitors from Roche. Receptors were immunoprecipitated by anti-HA. Precipitates were washed intensively with lysis buffer and subjected to either Western blot or an in vitro kinase assay. For the latter, immunoprecipitates were washed with kinase buffer containing 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5/10 mM MnCl2/5 mM MgCl2 and resuspended in kinase buffer with 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP [300 Ci/mmol (1 Ci = 37 GBq), Amersham Pharmacia Biotech] for 20 min at RT. Free radioactive ATP was removed by washing with 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0/150 mM NaCl/20 mM EDTA/0.1% Nonidet P-40. The products were resolved by SDS/PAGE, and the phosphorylated proteins were visualized by autoradiography by using a PhosphorImager.

Results

BDA2 Maps to 4q21-q25. A locus for BDA2 was mapped in two unrelated families to a 21.2-centimorgan region between markers D4S2361 and D4S1571 on chromosome 4. The pairwise logarithm of odds score were highest for marker D4S2623 (Zmax = 5.8 at θ = 0). Linkage analysis of a third family revealed no association to this region, indicating that BDA2 is genetically heterogeneous. We searched for candidate genes in the region and focused on BMPR1B, a serine-threonine kinase receptor of the TGF-β superfamily, known to play a pivotal role in chondrocyte differentiation through signal transduction pathways involving BMPs and related molecules.

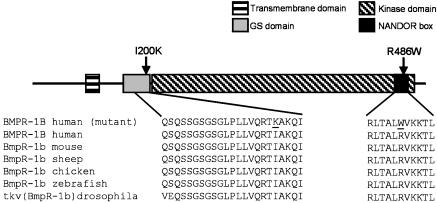

Identification of Mutations in BMPR1B. We amplified all exons from genomic DNA and sequenced both strands. In family 1 (Fig. 2), we identified a C-to-T transition (C1456 → T) in exon 10, which results in an arginine-to-tryptophan substitution (R486W). The mutation was present in all affected but in none of the unaffected family members. In family 2 (Fig. 2), a T-to-A transversion (T599 → A) was identified in exon 6, leading to an isoleucine-to-lysine substitution (I200K). Both missense mutations are located in highly conserved regions of the receptor. As depicted in Fig. 3, BMPR1B consists of an extracellular ligand-binding domain, a transmembrane domain, an amino acid stretch involved in phosphorylation called the GS domain, a serine-threonine kinase, and a C-terminal motif of 11 amino acids [referred to as a nonactivating, non-down-regulating (NANDOR) box (23)] thought to be involved in phosphorylation as well as receptor down-regulation. Mutation I200K is located in the GS box, and mutation R486W lies within the NANDOR box.

Fig. 3.

Schematic BMPR1B structure and mutations. Shown is the structure of BMPR1B showing the functional domains and the position of mutations (indicated by arrows). The amino acid sequences of BMPR1B are from different species, demonstrating the high degree of conservation within both domains. The two different mutations within the domains are underlined.

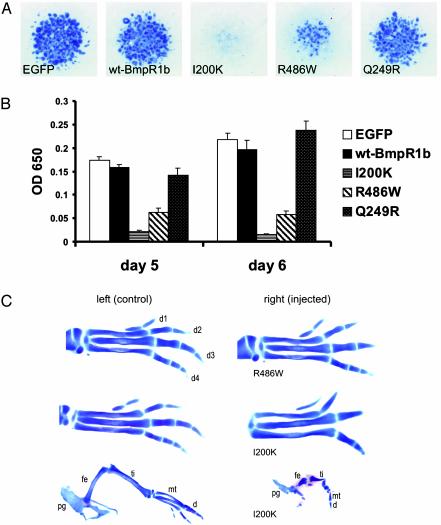

Mutant BMPR1B Inhibits Chondrogenic Differentiation. To investigate the cellular effects of these amino acid changes on BMPR1B function, the mutations were introduced into chBmpR1b cDNA, which is highly homologous to human BMPR1B. WT and mutant gene constructs were expressed in ch limb micromass cultures by using a retroviral system (RCAS) (24). This in vitro system is widely used as a model of chondrogenic differentiation. The degree of early chondrocyte differentiation was quantified by Alcian blue staining of proteoglycans at days 5 and 6. Cells transfected with WT chBmpr1b were not distinguishable from enhanced GFP-expressing control cultures. In contrast, cultures transfected with mutant chBmpR1b showed a strong inhibition of cartilage differentiation. Mutation I200K had a stronger effect than the R486W mutant in this system (Fig. 4 A and B). For comparison, we also tested a mutation (Q249R) in BmpR1b that was described recently in the Booroola strain of Australian Mérino sheep, a strain characterized by high ovulation rate and litter size but having a normal skeleton (21, 25). We found a slight but not significant increase in Alcian blue staining when compared with the WT infected cells.

Fig. 4.

Retroviral overexpression of BmpR1B mutants in micromass cultures and in chicken embryos. (A) Alcian blue-stained micromass cultures after 5 days of cultivation transfected with control [enhanced GFP (EGFP)] virus, WT Bmpr1b, or the indicated mutant constructs. In comparison with cultures expressing enhanced GFP– or the WT gene, those expressing either the I200K or R486W mutation genes exhibited a strong inhibition of chondrogenesis. (B) The quantification of Alcian blue incorporation into the extracellular matrix of micromass cultures reflecting the production of proteoglycan-rich cartilaginous matrix measured at days 5 and 6 is shown. Both mutations strongly inhibit cartilage formation. Note the stronger effect of the I200K mutation. The Q249R mutation described in the Booroola strain of Mérino sheep was also tested but shows no significant difference to WT BmpR1b. (C) Transfection of mutant chBmpR1b in chicken limbs induces a variable phenotypic severity, presumably due to infection efficacy. Infected limbs (Right) are shown along with the uninfected contralateral control limbs (Left). The milder phenotypes observed for both mutations (Top) display a marked BD with absent middle phalanges (R486W) or missing distal phalanges (1200K). In limbs with a high infection rate, a much stronger phenotype was observed, resulting in extreme shortening of all skeletal elements (I200K, Bottom). pg, pelvic girdle; fe, femur; ti, tibia; mt, metatarsal; d, digit.

Effects of BMPR1B Mutants in Vivo. To explore whether the perturbation of chondrogenesis observed in vitro also occurs in vivo, we introduced both chBmpR1b mutants (I200K and R486W) into limbs of chicken embryos by retroviral-mediated overexpression. Alcian blue staining of ch limbs at Hamburger/Hamilton stage 34/35 revealed a severely impaired cartilage differentiation when infected with the mutant constructs (Fig. 4C). Both mutants resulted in phenotypes with variable severity, presumably corresponding to the level of retroviral infection. The mildly affected cases presented with BD (30% of I200K and 75% of R486W mutants), and the severely affected limbs (70% of I200K and 25% of R486W mutants) showed a severe disturbance of the overall cartilage patterning and condensation. The BD phenotype was similar to the BDA2 phenotype involving aplasia or hypoplasia of individual phalanges.

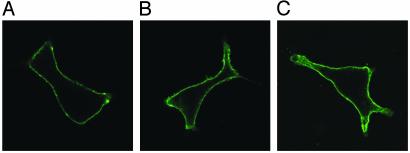

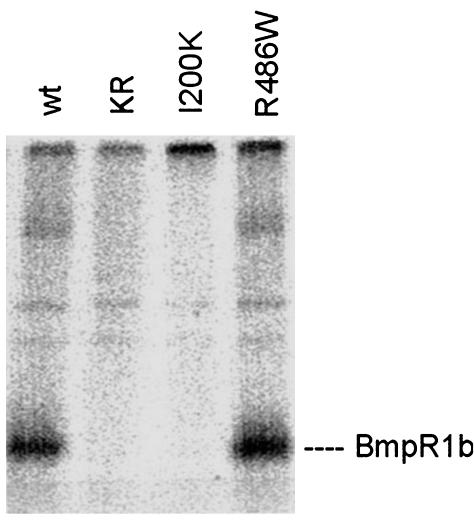

Localization and Receptor Activation of BMPR1B Mutants. BMPR1s are transmembranous receptors located at the cell surface. The immunodetection of HA-tagged mouse BmpR1b constructs in COS7 cells demonstrated that both mutant BmpR1b constructs as well as WT BmpR1b are located at the cell surface (Fig. 5), indicating that the mutant receptors were processed similar to the WT receptor. Nontransfected control cells showed no immunostaining. Next, the effects of I200K and R486W mutations on receptor activation were studied. Immunoprecipitation studies on COS7 cells transfected with the different BmpR1b mutants were performed and compared with WT BmpR1b and a dominant-negative mutant form of mouse BmpR1B (K231R) lacking kinase activity (26). As shown in Fig. 6, the WT BmpR1b construct shows constitutive autophosphorylation in vitro. The GS domain mutant I200K was kinase-deficient and revealed no autophosphorylation. In contrast, the R486W mutant showed normal kinase activity, indicating a different pathogenic mechanism in this mutant.

Fig. 5.

Immunodetection of BmpR1b constructs expressed in COS7 cells. COS7 cells were transfected with HA-tagged mouse BmpR1b constructs containing WT BmpR1b (A), I200K BmpR1b (B), and R486W BmpR1b (C). Immunostaining against HA shows that WT and both mutant BmpR1b constructs are located at the cell surface.

Fig. 6.

In vitro kinase assay. COS7 cells were transiently transfected with mouse BmpR1B constructs containing WT BmpR1b, a kinase-inactivated receptor (KR), and the mutations I200K and R486W. Cells were solubilized, and BMPRs were immunoprecipitated by anti-HA antibodies and then subjected to in vitro kinase assays in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. The kinase-inactivated receptor and I200K mutant showed no kinase activity; mutant R486W revealed a unchanged kinase activity.

Discussion

In this study we describe missense mutations in BMPR1B as the cause for BDA2, a hand malformation characterized by hypoplasia/aplasia of specific phalanges. BmpR1b is of general interest because of its role in the regulation of skeletogenesis. Both BMPR1s (BmpR1a and BmpR1b) are involved in the initial steps of cartilage condensation. After the differentiation of cartilage elements, BmpR1a is down-regulated, but the expression of BmpR1b continues in cartilage (27). Inactivation of BmpR1b in the mouse results in a recessive BD phenotype involving all digits (16, 28). Interestingly, the rest of the skeleton is normal, indicating that, in the mouse, BmpR1b is an essential signaling component for the formation of the digits but not for other parts of the endochondral skeleton. The ligands of BmpR1b are the BMPs but Gdf5 binds with the highest affinity (29). Mutations in Gdf5 cause BDC in humans (6) and the brachypodism (bp) phenotype in the mouse (30). Brachypodism mice and mice with inactivated BmpR1b have similar phenotypes. The phenotype of BDA2 is distinct from the BmpR1b–/– and the bp phenotype. The same is true for the overexpression phenotypes in the ch, in particular in the severe phenotypes that show malformations of the entire limb skeleton (Fig. 4C). The mutations described here function as dominant negatives and can be expected to interfere with the signaling of other TGF-β receptors (TGFBRs) and their respective ligands, thus explaining the different effects.

The missense mutations in the BMPR1B gene presented here are shown to be disease-causing BMPR1B mutations in humans. The I200K and R486W amino acid changes in BMPR1B are both located in highly conserved regions of the receptor, the GS and NANDOR domains, respectively. The functional role of the GS domain has been investigated in the type I TGFBR (TGFBR1). Immunophilin FKBP12, an inhibitory protein of the TGF-β pathway, blocks the unphosphorylated GS region of the type I receptor and stabilizes the inactive form of TGFBR1. Phosphorylation of the GS domain prevents the inhibition by FKBP12 and augments the kinase activity of TGFBR1 (31). Two distinct motifs seem to be essential within the GS domain: the GS box in the middle and the RTI sequence at the end of the domain, which is directly adjacent to the kinase domain. Mutations of threonine to valine at positions 200 and 204 caused loss of ligand-induced phosphorylation in the GS box and impaired signaling. In contrast, a mutation of Thr-204 to an acidic residue resulted in constitutive activation of the receptor (32, 33). The I200K mutation in BMPR1B described here, equivalent to position 201 in TGFBR1, replaces the isoleucine in the RTI motif. In in vitro kinase assays, we demonstrate that mutation I200K results in the loss of BmpR1b kinase function. In addition, our micromass results for the I200K Bmpr1b mutant indicate a significant inhibition of cartilage differentiation. These results confirm the assumption that the I200K amino acid change within the RTI motif of the GS domain works as a dominant negative by disturbing the phosphorylation process necessary for activating kinase function.

The sequence between amino acids 482 and 491 (NANDOR box) in TGFBR1, identical to amino acids 481–492 in human BMPR1B, was shown to be important for endocytosis of TGFBR complexes at the cell surface in mesenchymal cells. Furthermore, this sequence regulates the activation of TGFBR1 and is thought to be essential for transphosphorylation of TGFBR1 by the type II TGFBR (23). In the micromass experiments as well as in vivo experiments, the R486W mutant was less potent than the I200K mutant. Our in vitro kinase assay shows that this mutant has normal kinase activity, a finding that is in agreement with the proposed function of this domain. Compared with WT BmpR1b, the R486W mutant receptor is localized at the cell surface in a unchanged manner, indicating that the initial intracellular processing is not affected by the mutation. In analogy to the known function of this domain in TGF-β, we propose that the mutation R486W in BMPR1B exerts its dominant effect by either interfering with receptor down-regulation or the transphosphorylation by BMPR2 at the cell surface.

Recently, in Booroola Mérino ewes a Q249R alteration in a highly conserved region of BmpR1b was shown to be associated with an increased ovulation rate and litter size (21, 25). An important role for BmpR1b in female reproduction function is supported by the occurrence of infertility in female BmpR1b–/– knockout mice (34). However, there are no reports of skeletal abnormalities associated with the Q249R mutation. This is also indicated by our in vitro results for the Q249R Bmpr1b mutant using the micromass culture system. No significant change in chondrocyte differentiation was observed (Fig. 4 A and B), indicating that the mutation specifically alters the response of oocytes to BMP signaling but has no major effect on skeletal differentiation. Interestingly, Freire-Maia et al. (35) published a large Brazilian kindred with 117 family members of German origin with BDA2, in which the analysis of the pedigree indicated a higher fertility in affected females than among unaffected individuals. We did not find any evidence of BmpR1b-associated reproductive variance in our BDA2 families.

We performed in vitro experiments using a micromass culture system and carried out in vivo overexpression tests in ch embryos. Both indicate that the mutations I200K and R486W in chBmpR1B affect cartilage formation in a dominant-negative manner. Similar to the in vitro experiments, the I200K mutant in vivo caused the stronger dominant-negative effect on cartilage differentiation. In ch limbs the weaker phenotype (30% of I200K and 75% of R486W mutants) showed shortening and/or absence of individual phalanges and thus closely resembled the human BDA2 phenotype. The BD phenotype generated with our ch mutants was similar to that observed by Zou et al. (36) when using a dominant-negative chBmpR1B mutant construct with an inactivated kinase domain. However, the severe phenotype (70% of I200K and 25% of R486W mutants) with an overall limb reduction was not described in their work.

We hypothesize that the severe phenotype of I200K and R486W ch mutants, supposedly caused by a very high efficacy of retroviral infection, is comparable with the homozygous status of BDA2 in humans. This severe phenotype in the chicken limb parallels the description of a strongly affected child described in the original BDA2 publication by Mohr and Wried (2). The affected girl, an offspring of two affected parents with BDA2, was described as having a very severe phenotype (“her whole osseous system was in disorder and her hands and feet, or at any rate her fingers and toes, were entirely absent”), raising the possibility that the clinical description represents a homozygous case of BDA2.

In summary, we describe missense mutations in BMPR1B that are causative for BDA2 in humans. We conclude from our studies that these mutations affect cartilage differentiation and bone formation in a dominant-negative way. Challenges for the future will be to understand exactly how these amino acid changes are involved in BMPR1B activation and the regulation of BMP signaling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Niswander for generously providing us with the clones for ch-BmpR-1bs. We acknowledge the expert technical support of Asita Carola Stiege. We also thank the families for participation. This study was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to S.M.). P.N. was supported by Federal Department of Education and Research Grant 01 GR 0104 (Subproject KB-P6T01-1).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: BD, brachydactyly; BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β; GDF, growth/differentiation factor; BMPR, BMP receptor; ch, chick; RT, room temperature; HA, hemagglutinin; NANDOR, nonactivating, non-down-regulating; TGFBR, TGF-β receptor; GS, glycine/serine.

References

- 1.Bell, J. (1951) in Treasury of Human Inheritance (Cambridge Univ. Press, London), Vol. 5, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohr, O. L. & Wried, C. (1919) A New Type of Hereditary Brachphalangy in Man (Institution of Washington, Washington, DC).

- 3.Gao, B., Guo, J., She, C., Shu, A., Yang, M., Tan, Z., Yang, X., Guo, S., Feng, G. & He, L. (2001) Nat. Genet. 28, 386–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oldridge, M., Fortuna, A. M., Maringa, M., Propping, P., Mansour, S., Pollit, C., DeChiara, T. M., Kimble, R. B., Valenzuela, D. M., Yancopoulos, G. D. & Wilkie, A. O. (2000) Nat. Genet. 24, 275–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwabe, G. C., Tinschert, S., Buschow, C., Meinecke, P., Wolff, G., Gillessen-Kaesbach, G., Oldridge, M., Wilkie, A. O., Komec, R. & Mundlos, S. (2000) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 67, 822–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polinkovsky, A., Robin, N. H., Thomas, J. T., Irons, M., Lynn, A., Goodman, F. R., Reardon, W., Kant, S. G., Brunner, H. G., van der Burgt, I., et al. (1997) Nat. Genet. 17, 18–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Francis-West, P. H., Abdelfattah, A., Chen, P., Allen, C., Parish, J., Ladher, R., Allen, S., MacPherson, S., Luyten, F. P. & Archer, C. W. (1999) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 126, 1305–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Storm, E. E. & Kingsley, D. M. (1996) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 122, 3969–3979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reddi, A. H. (2001) J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 83, Suppl. 1, S1–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilboa, L., Nohe, A., Geissendorfer, T., Sebald, W., Henis, Y. I. & Knaus, P. (2000) Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 1023–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Bubnoff, A. & Cho, K. W. (2001) Dev. Biol. 239, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Attisano, L. & Wrana, J. L. (2002) Science 296, 1646–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lane, K. B., Machado, R. D., Pauciulo, M. W., Thomson, J. R., Phillips, J. A., 3rd, Loyd, J. E., Nichols, W. C. & Trembath, R. C. (2000) Nat. Genet. 26, 81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howe, J. R., Bair, J. L., Sayed, M. G., Anderson, M. E., Mitros, F. A., Petersen, G. M., Velculescu, V. E., Traverso, G. & Vogelstein, B. (2001) Nat. Genet. 28, 184–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massague, J., Blain, S. W. & Lo, R. S. (2000) Cell 103, 295–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baur, S. T., Mai, J. J. & Dymecki, S. M. (2000) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 127, 605–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ide, H., Katoh, M., Sasaki, H., Yoshida, T., Aoki, K., Nawa, Y., Osada, Y., Sugimura, T. & Terada, M. (1997) Oncogene 14, 1377–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamburger, V. & Hamilton, H. L. (1992) Dev. Dyn. 195, 231–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeLise, A. M., Stringa, E., Woodward, W. A., Mello, M. A. & Tuan, R. S. (2000) Methods Mol. Biol. 137, 359–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Logan, M. & Tabin, C. (1998) Methods 14, 407–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mulsant, P., Lecerf, F., Fabre, S., Schibler, L., Monget, P., Lanneluc, I., Pisselet, C., Riquet, J., Monniaux, D., Callebaut, I., et al. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 5104–5109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stricker, S., Fundele, R., Vortkamp, A. & Mundlos, S. (2002) Dev. Biol. 245, 95–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garamszegi, N., Dore, J. J., Jr., Penheiter, S. G., Edens, M., Yao, D. & Leof, E. B. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 2881–2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan, B. A. & Fekete, D. M. (1996) Methods Cell Biol. 51, 185–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson, T., Wu, X. Y., Juengel, J. L., Ross, I. K., Lumsden, J. M., Lord, E. A., Dodds, K. G., Walling, G. A., McEwan, J. C., O'Connell, A. R., et al. (2001) Biol. Reprod. 64, 1225–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zou, H. & Niswander, L. (1996) Science 272, 738–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ashique, A. M., Fu, K. & Richman, J. M. (2002) Int. J. Dev. Biol. 46, 243–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yi, S. E., Daluiski, A., Pederson, R., Rosen, V. & Lyons, K. M. (2000) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 127, 621–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishitoh, H., Ichijo, H., Kimura, M., Matsumoto, T., Makishima, F., Yamaguchi, A., Yamashita, H., Enomoto, S. & Miyazono, K. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 21345–21352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Storm, E. E., Huynh, T. V., Copeland, N. G., Jenkins, N. A., Kingsley, D. M. & Lee, S. J. (1994) Nature 368, 639–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huse, M., Muir, T. W., Xu, L., Chen, Y. G., Kuriyan, J. & Massague, J. (2001) Mol. Cell 8, 671–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wieser, R., Wrana, J. L. & Massague, J. (1995) EMBO J. 14, 2199–2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dore, J. J., Jr., Yao, D., Edens, M., Garamszegi, N., Sholl, E. L. & Leof, E. B. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 675–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yi, S. E., LaPolt, P. S., Yoon, B. S., Chen, J. Y., Lu, J. K. & Lyons, K. M. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 7994–7999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freire-Maia, N., Maia, N. A. & Pacheco, C. N. (1980) Hum. Hered. 30, 225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zou, H., Wieser, R., Massague, J. & Niswander, L. (1997) Genes Dev. 11, 2191–2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.