Abstract

The ZAS proteins are large zinc-finger transcriptional proteins implicated in growth, signal transduction, and lymphoid development. Recombinant ZAS fusion proteins containing one of the two DNA-binding domains have been shown to bind specifically to the κB motif, but the endogenous ZAS proteins or their physiological functions are largely unknown. The κB motif, GGGACTTTCC, is a gene regulatory element found in promoters and enhancers of genes involved in immunity, inflammation, and growth. The Rel family of NF-κB, predominantly p65.p50 and p50.p50, are transcription factors well known for inducing gene expression by means of interaction with the κB motif during acute-phase responses. A functional link between ZAS and NF-κB, two distinct families of κB-binding proteins, stems from our previous in vitro studies that show that a representative member, ZAS3, associates with TRAF2, an adaptor molecule in tumor necrosis factor signaling, to inhibit NF-κB activation. Biochemical and genetic evidence presented herein shows that ZAS3 encodes major κB-binding proteins in B lymphocytes, and that NF-κB is constitutively activated in ZAS3-deficient B cells. The data suggest that ZAS3 plays crucial functions in maintaining cellular homeostasis, at least in part by inhibiting NF-κB by means of three mechanisms: inhibition of nuclear translocation of p65, competition for κB gene regulatory elements, and repression of target gene transcription.

The Rel family of NF-κB encodes important transcription factors that regulate the induction of genes involved in immunological, inflammatory, and antiapoptotic responses (1, 2). In most resting cells, NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm, bound to a family of inhibitory molecules, inhibitor (I)κB. Many stimuli, including lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (3) and inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor (TNF) (4), activate the NF-κB signal transduction pathway and lead to the phosphorylation and degradation of IκB. NF-κB is then imported into the nucleus, where it activates transcription of target genes. In many cell types, the predominant NF-κB species are p65.p50 and p50.p50. However, other κB-DNA-binding proteins (designated as non-Rel-κBs) distinct from NF-κB have been characterized. Generally, non-Rel-κBs differ from NF-κB by size, immunogenicity, sensitivity to detergents, and sequence specificity to the κB motif (Table 1).

Table 1. Distribution and properties of non-Rel-κB.

| Name | Distribution | Properties | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Band A | BU-11 (pro-B to early pre-B), WEHI-231 (slg+), and 70Z/3 (late pre-B) | 125-135 kDa; did not react with NF-κB antibodies; decreased by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons | 20 |

| 110- and 180-kDa species | Jurkat T lymphocyte | Differential specificity of DNA binding for various κB enhancer sequences from NF-κB; induced by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate | 35 |

| Abnormal κB-binding protein | S107 plasmocytoma | Localize in cytoplasm; binding abolished by deoxycholate and NP-40; 110-115 kDa; suggested to inhibit nuclear translocation of cytoplasmic NF-κB and thereby void κB-mediated expression | 19 |

| Brain-specific κB-binding protein (BETA) | Primary neurons | Does not activate κB-mediated expression; reacts with antisera against ZAS2 but not ZAS1 or p65 antibodies; DNA binding depends on zinc ion | 11, 36 |

| Neuronal κB-binding factor (NKBF) | Brain, primary neurons, cerebellum, and cell lines (N9, CBL, and NT2) | Does not react with NF-κB antibodies (p50, p65, c-Rel, p52, and RelB) or with ZAS2 antibodies; sensitive to DOC; present in p105/p50 knockout mice; composed of proteins of 27, 82, and 109 kDa; induces by 8-Br-cGMP; inhibits by glutamate | 12 |

| Developing-brain factors 1 and 2 (DBF1 and -2) | Developing cortex, brain not in lung, liver, intestine, heart, and kidney | 110 and 115 kDa; sensitive to DOC; binding-site specificity similar to NF-κB; does not react with p100 or p105 antibodies; developmentally regulated in brain | 37 |

| Posthepatectomy factor (PHF) | Regenerating livers | Induced >1,000-fold within minutes postheptatectomy in a protein-synthesis-independent manner; DNA binding sensitive to phosphatases | 38 |

| Not named | 293 cells | Induced by NF-κB-activating kinase | 39 |

An additional gene family known to encode proteins that also bind to the κB motif is called the ZAS family (5). “ZAS” describes a structural domain that contains a pair of C2H2 zinc fingers, an acidic region, and a serine/threonine-rich sequence (6). There are three ZAS proteins, ZAS1, -2, and -3, in mammals and a distant relative, schnurri (shn), in Drosophila. The ZAS proteins have been shown to regulate transcription of genes involved in immunity, development, and metastasis (5). They have also been shown to regulate signal transduction. Schnurri associates with Mad/Smad to modulate decapentaplegic/transforming growth factor β signaling during embryonic development (7). ZAS3 associates with TRAF2 to inhibit TNF-induced NF-κB-dependent transactivation and JNK phosphorylation in vitro (8).

Extensive DNA–protein interaction analyses have shown that individual ZAS domains bind specifically to κB-like sequences (9, 10). This observation has prompted several groups, including ours, to investigate whether the ZAS proteins are non-Rel-κBs. Results of antibody gel-shift assays and reporter gene assays suggest that non-Rel-κBs are related to ZAS2 and -3 (11–13). However, another study suggests that non-Rel-κB may be related to Sp1 (14). Recently, several immortalized ZAS3–/– preB cell lines have been established from a malignant teratoma that developed spontaneously in a ZAS3–/–RAG2–/– chimeric mouse (15). To clarify the origin of non-Rel-κB, we examine the κB-binding species and show that non-Rel-κB is absent in those ZAS3–/– cells. Additionally, in keeping with our previous results, which show that ZAS3 associates with TRAF2 to inhibit NF-κB activation, NF-κB is constitutively expressed in ZAS3–/– cells. Because ZAS3 can regulate κB-mediated transcription and influence the activity of NF-κB, this mechanism provides a checkpoint to control the reprogramming of gene expression.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids. The reporter plasmids, 3×κB-Luc and p7×κB, and expression constructs for p50 and p65 have been described (16, 17). Both plasmids were used in reporter gene assays and yielded similar results. For the construction of a ZAS3 expression vector, a 5.7-kb XhoI ZAS3 cDNA fragment (nucleotides 973–6693) was inserted into the XhoI site of the expression vector pCMV-Tag2 (Stratagene). pSG-ZASC was constructed by inserting a 1.6-kb ZAS3 cDNA fragment (nucleotides 5831–7490) into the EcoRI site of the plasmid pSG424 (18).

Antibodies. ZAS3 antisera have been described (13). NF-κB antibodies were gifts from Denis Guttridge, Ohio State University: p65 (Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA), p50 (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), p52 (K-27; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and c-Rel (N; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Antibodies for IκBα (C-21), p-IκBα (B-9), hsp90, TRAF1, TRAF2, histone H1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and FLAG (Sigma) were purchased.

Cell Lines and Transient Transfection Assays. Immortalized ZAS3–/–B1 and ZAS3–/–B2 preB cells were previously called KRC-mIII and -mIV, respectively (15). PreB cells were cultured in complete medium (RPMI medium 1640) containing 10% FCS and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol. p65+/+ and p65–/– mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF), human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293, and Cos-7 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS. For transient transfection, 2–5 × 105 suspension cells were seeded into each well of a 24-well plate and were cultured overnight in complete medium. After 24 h, reporter plasmid (250 ng), with or without ZAS3 expression plasmid, was transfected into cells by using the cationic lipid reagent DMRIE-C (2 μl per well) (Invitrogen). Plasmid pCH110 (250 ng) encoding β-galactosidase was included to normalize transfection efficiency. pCMV-Tag2 was supplemented to yield a total plasmid concentration of 1 μg in each transfection. Thirty-six hours posttransfection, LPS (10 μg/ml) was added to a subset of cells, and all cells were harvested 4 h later. For adherent cells, reporter plasmid (10 ng), p65 and p50 expression plasmids (10 ng each), ZAS3 expression plasmid (0–0.4 μg), lipofectamine 2000 (2 μl per well; Invitrogen), and pCMV-Tag2 (to adjust total DNA to 0.5 μg) were used in each transfection. Luciferase and β-galactosidase activity were measured as described (15).

Electrophoretic Mobility-Shift Assays (EMSAs), Antibody-Supershift Assays, and Immunoblot Analyses. EMSAs and antibody-supershift assays, with a 32P-labeled probe (2 × 104 cpm) containing a κB site (underlined), 5′-CCGGGGGGACTTTCCGCTCCAC-3′, were performed as described (10). Immunoblot analyses were performed as described (15). The presence of equivalent protein loading was verified by protein staining of duplicated gels or by incubating duplicated protein blots with histone H1 or heat-shock protein hsp90 antibodies.

Results and Discussion

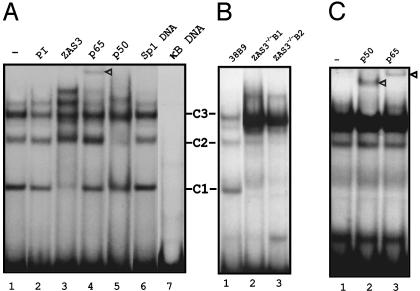

ZAS3 Antisera React with a Non-Rel-κB Absent in ZAS3–/– Cells. In EMSA, nuclear extracts prepared from a standard preB cell line, 38B9, and a 32P-κB probe yielded several sequence-specific DNA–protein complexes (Fig. 1A, lane 1). The prominent complexes were designated C1, -2, and -3. The addition of a ZAS3-antiserum but not preimmune serum to the binding reactions diminished the amount of C1 (Fig. 1 A, lanes 2 and 3). Antibodies against p65 and p50 also altered the pattern of the DNA–protein complexes (Fig. 1 A, lanes 4 and 5). Likely, C2 and -3 were composed of p50.p50 and p65.p50, respectively. The specificity of the protein–DNA interaction was demonstrated by DNA competition. Unlabeled κB oligonucleotides (20 ng; 100-fold excess) competed away the formation of all complexes (Fig. 1 A, lane 7), whereas a similar amount of Sp1 oligonucleotide was noncompetitive (Fig. 1 A, lane 6). Therefore, non-Rel-κB is present in preB cells, in agreement with previous studies of B cell lineages (19, 20). The data also show that non-Rel-κB is immunologically related to ZAS3.

Fig. 1.

NF-κB and ZAS3 are the major κB DNA-binding proteins in B lymphocytes. (A) EMSA of 32P-κB oligonucleotide and 38B9 nuclear extracts. Antibodies or unlabeled DNA (20 ng; 100-fold excess) supplemented to binding reactions are indicated at the top of each lane. The major DNA–protein complexes were designated as C1, -2, and -3. (B) EMSA of 32P-κB oligonucleotide and nuclear extracts. Lane 1, 38B9; lanes 2 and 3, representative ZAS3-deficient cells ZAS3–/–B1 and ZAS3–/–B2. (C) Gel supershift assays show the presence of p65 and p50 in the predominant κB–DNA protein complex derived from ZAS3–/–B1 nuclear extracts. Triangles indicate antibody supershifted complexes.

To clarify the origin of the non-Rel-κB in B lymphocytes, EMSA was performed by using a genetic background where ZAS3 was knocked out by homologous recombination. ZAS3–/–B1 and ZAS3–/–B2 were preB cell lines independently derived from a malignant teratoma of a RAG2–/–ZAS3–/– chimera mouse (15). In EMSA, a prominent p65.p50 complex but not the C1 complex was observed from either nuclear extracts of the ZAS3–/– cells (Fig. 1 B and C). Previous extensive RNA studies, including Northern blot analysis, RT-PCR, RNase protection, and in situ hybridization, had shown that ZAS3 was expressed specifically in neuronal and lymphoid tissues (6, 10, 21–23). Therefore, the lymphoid expression, immunogenicity, and κB-binding capability of ZAS3 and non-Rel-κB are similar. Because non-Rel-κB had been detected in different lineages of B cells (20), the absence of C1 from ZAS3–/– B cells supports our notion that non-Rel-κB was a product of ZAS3. Although the ZAS–/– cell lines have been classified as preB cells based on morphology and cell-surface markers (15), there are no isogenic controls for those cells. The ZAS3–/– and ZAS3+/+ cells studied inevitably have other intrinsic genetic and subtle developmental differences. However, similar differential NF-κB regulation had been observed in two ZAS–/– preB cells and several standard ZAS3+/+ preB cell lines examined (38B9, 22D6, and IIA1.6). The establishment of isogenic ZAS3–/– and ZAS3+/+ mice will allow the performance of physiologically relevant experiments and the investigation of how ZAS3 deficiency may affect TNF-induced activation of NF-κB and JNK in an animal model.

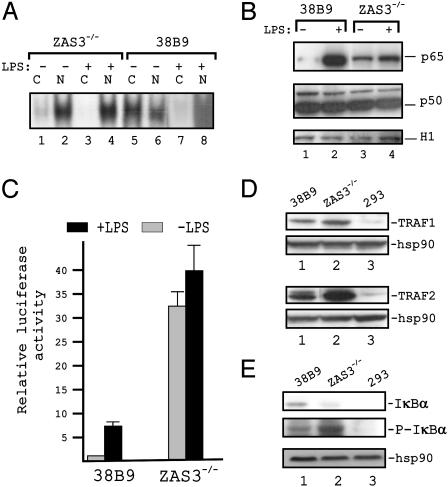

Constitutive Expression of p65 in the Nucleus of ZAS3-Deficient Cells. Previous in vitro studies have implicated ZAS3 in the inhibition of TNF-driven NF-κB activation by sequestering an adaptor molecule, TRAF2, essential for the assembly of the IκB kinase complex (8). The prominence of p65.p50 in nuclear extracts of ZAS3–/– cells supports that model. To demonstrate a functional link between ZAS3 and NF-κB, NF-κB was characterized in ZAS3–/– and ZAS3+/+ cells by EMSA. In unstimulated ZAS3–/– cells, NF-κB-binding activity was mostly found in nuclear extracts (Fig. 2A). As such, LPS (10 μg/ml for 4 h), a reagent commonly used to stimulate NF-κB in B cells (3), showed minimal effect. Conversely, NF-κB DNA-binding activity was found in both cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts from 38B9 cells. On LPS stimulation, NF-κB-binding activity from 38B9 cells was reduced to minimal levels in the cytoplasmic extracts with a concomitant increase of NF-κB-binding activity in the nuclear extracts. The higher NF-κB-binding activity from the nucleus of ZAS3–/– cells was due, at least in part, to constitutive nuclear localization. Immunoblot analysis of nuclear extracts showed that the amount of p65 in ZAS3–/– cells was 5- to 10-fold higher than in 38B9 cells (Fig. 2B), in keeping with EMSA results. In addition, LPS (10 μg/ml for 4 h) increased the nuclear levels of p65 significantly in 38B9 cells but minimally in ZAS3–/– cells. The constitutive expression of nuclear p65 in ZAS3–/– cells and the induction of p65 in 38B9 cells by LPS were specific, because the amounts of p50 and histone H1 were comparable among all samples.

Fig. 2.

Constitutive activation of NF-κB in ZAS3–/– cells. (A) EMSA of 32P-κB oligonucleotide, nuclear extracts (N), or cytoplasmic extracts (C), and with (+) or without (–) LPS (10 μg/ml for 4 h). (B) Immunoblot analysis of nuclear extracts. (C) Reporter gene assays. Indicated cells were cotransfected with p7×κB (0.25 μg) and pCH110 (0.1 μg). Thirty-six hours posttransfection, duplicated cell samples were incubated with LPS (10 μg/ml, 4 h). Luciferase activity, normalized to β-galactosidase activity, from unstimulated 38B9 cells was assigned as +1. (D and E) Immunoblot analyses of cytoplasmic extracts.

Reporter gene assays were performed to assess the κB-mediated transcriptional competence of the preB cells. In line with the increase of κB-DNA binding and nuclear p65, the κB-reporter activity was 30-fold higher from ZAS3–/– than 38B9 cells (Fig. 2C). This observation agrees with the fact that, although all NF-κB contain a Rel homology domain for DNA binding, only p65, RelB, and c-Rel contain transactivation domains (1). In addition, LPS (10 μg/ml for 4 h) augmented κB-reporter activity 5- to 8-fold in 38B9 cells but minimally in ZAS3–/– cells. The increase in NF-κB binding and consequently κB-mediated transcription in ZAS3–/– cells was due, in part, to the up-regulation of nuclear p65.

The remarkable effect of ZAS3 on the κB-reporter suggests that ZAS3 should have a major impact on NF-κB-dependent gene expression and cell fate. Accordingly, ZAS3 had been shown to control the expression of TNFα, an NF-κB target gene, in macrophages and in an epithelial cell line (8). Additionally, tumorogenesis and immortalization had been observed in ZAS3-deficient animals and cells, respectively (15). In keeping with the differential expression of NF-κB, immunoblot analyses showed that the amount of TRAF1 and -2, whose expression was controlled by NF-κB, was higher in ZAS3–/– cells than in 38B9 cells (Fig. 2D).

In most cell types, NF-κB associated with IκB in the cytoplasm but was translocated into the nucleus when IκB was degraded. To further characterize NF-κB signaling in ZAS3–/– cells, the expression and phosphorylation status of IκBα were examined. The amount of IκBα in unstimulated 38B9 cells was significantly higher than that of ZAS3–/– cells (Fig. 2E), in keeping with the constitutive expression of NF-κB in the latter cells. Of interest, IκBα was hyperphosphorylated in ZAS3–/– cells, suggesting an induction of IκB kinase (IKK). Taken together, in ZAS3–/– cells, the absence of ZAS3, a TRAF2 inhibitor, activates the assembly of the IKK complex. IKK phosphorylates IκB, which marks IκB for ubiquitination and degradation. NF-κB then translocates into the nucleus, leading to activation of gene expression.

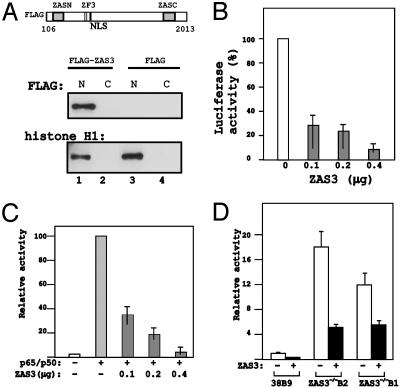

ZAS3 Directly Represses NF-κB-Mediated Transcription. ZAS3 expression was restored in ZAS3–/– cells to demonstrate that the induction of NF-κB was a consequence of ZAS3 deficiency. To this end, a 7.2-kb ZAS3 cDNA harboring the largest ORF of 2,348 residues was constructed by conventional molecular cloning procedures by using clones isolated from standard cDNA or genomic libraries. That DNA fragment, when inserted in-frame into the FLAG-tag expression plasmid pCMV-Tag2, yielded low expression in HEK 293 cells (data not shown). Subsequently, plasmids with shorter inserts were constructed, and a DNA fragment encoding amino acids 106–2013 of ZAS3, which contained all known structural features of ZAS3, yielded abundant fusion proteins (Fig. 3A). The FLAG-ZAS3 fusion protein was detectable from nuclear but not from cytoplasmic extracts. Similar cellular distribution was observed for a nuclear protein control, histone H1. Previously, ZAS3 antibodies detected signals from the nucleus and cytoplasm (8). The cytosolic signal might be derived from smaller ZAS3 isoforms generated by alternative splicing (22).

Fig. 3.

ZAS3 represses NF-κB-mediated transcription. (A) Expression of recombinant FLAG-ZAS3 proteins in HEK 293 cells. (Upper) Structural domains of recombinant FLAG-ZAS3 protein. NLS, nuclear localization signal. (Lower) Immunoblot analyses of HEK 293 cells transiently transfection with FLAG-ZAS3 expression plasmid or parental plasmid, pCMV-Tag2 (FLAG). N, nuclear extracts; C, cytoplasmic extracts. (B) Reporter gene assays. Plasmids 3×κB-Luc (10 ng) and pCH110 (10 ng) were cotransfected with the control parental vector (pCMV-Tag2; white bar) or indicated amount of FLAG-ZAS3 expression plasmid (black bars) in HEK 293 cells. The normalized luciferase activity of cells cotransfected with the control vector was assigned to 100%. (C) ZAS3 repressed NF-κB-activated transcription. Transient transfection experiments were performed with (+) or without (–) p65 and p50 expression plasmids (10 ng each) in HEK 293 cells. The normalized luciferase activity of cells transfected with p65 and p50 expression plasmids was assigned as 100. (D) ZAS3 repressed a κB-reporter gene in ZAS3–/– cells. Normalized luciferase activity of transfection in 38B9 cells with the reporter gene only was assigned as 1.

Reporter gene assays initially showed that ZAS3 expression reduced the activity of κB-reporter genes in HEK 293 (Fig. 3B) and 38B9 cells (data not shown). Subsequent cotransfection experiments with ZAS3 and NF-κB (p50 and p65) expression constructs showed that ZAS3 repressed NF-κB-mediated transactivation of the κB reporter (Fig. 3C). Significantly, ZAS3 expression also inhibited the κB reporter in ZAS3–/– cells (Fig. 3D), providing a link between ZAS3 deficiency and NF-κB activation.

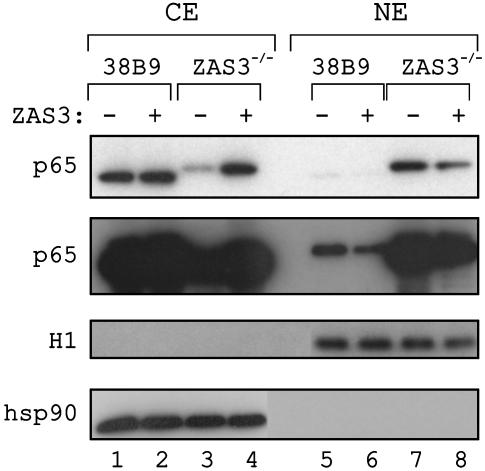

To evaluate how ZAS3 expression represses NF-κB-dependent transactivation, the level of NF-κB in the preB cells was examined after transient transfection with the ZAS3 expression construct by immunoblot analyses. In 38B9 cells, p65 was mainly located in the cytoplasmic extracts and was barely detected from the nuclear extracts (Fig. 4, compare lanes 1 and 5). ZAS3 expression in 38B9 cells reduced the amount of nuclear p65 with a concomitant increase of cytoplasmic p65. On the contrary, p65 was located mainly in the nuclear extracts of ZAS3–/– cells (Fig. 4, compare lanes 3 and 7). Introduction of the ZAS3 expression construct in ZAS3–/– cells resulted in a marked reduction of nuclear p65 and a corresponding increase of cytoplasmic p65. As controls for protein loading and cell fractionation, appropriate signals were observed when immunoblot analyses were performed for a nuclear protein, histone H1, or a cytosolic protein, heat-shock protein hsp90. We conclude that p65 was up-regulated in ZAS3–/– cells, and that ZAS3 activated the nuclear export pathway of p65.

Fig. 4.

ZAS3 inhibits nuclear localization of p65. Immunoblot analysis of 38B9 and ZAS3–/– cells after transient transfection with FLAG-ZAS3 (+) or parental FLAG (–) expression plasmids showed that p65 was localized mainly in the cytoplasmic extracts (CE) of 38B9, but in the nuclear extracts (NE) of ZAS3–/– cells. ZAS3 expression in both cells reduced the amount of nuclear p65 with a concomitant increase of cytoplasmic p65. The second p65 was an overexposure of the first to highlight the reduction of nuclear p65 by ZAS3 expression in 38B9 cells. As controls for protein loading and cell fractionation, immunoblot analyses were also performed with a nuclear protein control, histone H1, and a cytosolic protein control, heat-shock protein 90 (hsp90).

A careful inspection revealed that the gel mobility of p65 from 38B9 cells was slightly faster than that of ZAS3–/– cells, indicating differences in posttranslational modifications. Protein modifications at specific sites, including phosphorylation and acetylation, have been shown to affect DNA binding, IκB association, and transcriptional activity of p65 (24, 25). However, incubation of the samples with shrimp alkaline phosphatases had no effect on the gel mobility of p65 (data not shown), suggesting the difference might not be due to protein phosphorylation. Previously, two such closely migrating p65-antibody reacting species were observed in immunoblot analysis of rat livers, and treatment with calf intestine alkaline phosphatases also did not resolve the difference in their gel mobility (26).

ZAS3 Represses Transcription Independent of p65. Although p65 contains the transactivation domain, the activity of the κB-reporter genes was not directly proportional to the amount of p65. For example, whereas the amount of p65 in LPS-stimulated 38B9 was more than that in ZAS3–/– cells (compare Fig. 2B, lanes 2 and 4), the κB reporters were 5-fold more active in the latter (Fig. 2C). There are several not mutually exclusive possibilities to account for this discrepancy. First, RelB and c-Rel, which also contain transcription activation domains, may mediate κB transcription. However, significant differences of these proteins were not detected in the preB cells (data not shown). Second, NF-κB may have different posttranslational modifications. Recently, it is shown that phosphorylation and acetylation of p65 can increase NF-κB transcriptional activity. Third, ZAS3 may compete for and displace NF-κB from κB sites. ZAS3 may induce transcription less efficiently than NF-κB or may even repress transcription. Members of the ZAS family have been shown to inhibit transcription. ZAS1 negatively regulates the α1(II) collagen gene (27), whereas ZAS2 represses c-myc transcription from the major P2 promoter (28).

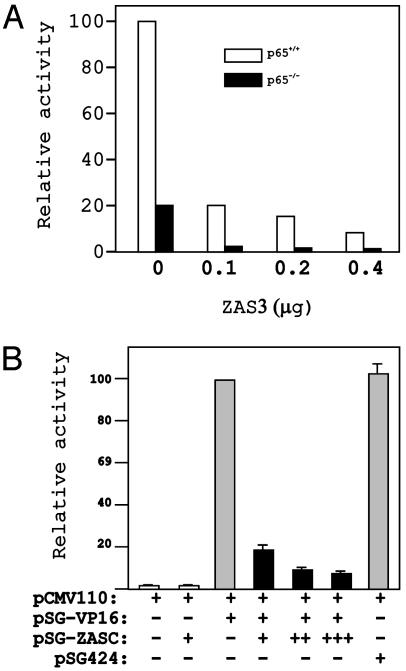

To further elucidate the mechanisms by which ZAS3 regulates κB-mediated transcription, κB-reporter gene assays were performed with p65–/– MEF. The κB-reporter was 5-fold more active in p65+/+ than in p65–/– MEFs, demonstrating the importance of p65 in κB-mediated transactivation (Fig. 5A). Notably, even when p65 was absent, κB-reporter gene activity was still significantly higher than that of a control reporter, which lacked the κB enhancer (data not shown). Therefore, the κB reporter must be driven by transacting factors for the κB-DNA in p65–/– MEFs. Finally, ZAS3 expression repressed κB-reporter genes both in p65+/+ and p65–/– MEF, suggesting that ZAS3 also represses κB-mediated transcription independent of p65.

Fig. 5.

ZAS3 also represses transcription independent of p65. (A) Reporter gene assays. Transient transfection was performed in p65–/– MEFs (black bars) or p65+/+ control MEFs (white bars). Normalized activity of the κB-reporter in p65+/+ MEF transfected with the empty vector is taken as 100. A representative experiment of three is shown here. (B) ZASC inhibits transcription activation of VP16. Cos-7 cells were transiently transfected with pCMV110 (5 μg), and pSG-VP16, pSG-ZASC, or pSG424 expression plasmids, as indicated. The relative chloramphenicol acetyl transferase activity of duplicates is illustrated for each experiment. The amounts of plasmid DNA used are: +,10 μg; ++,15 μg; +++, 20 μg; and –, 0 μg. Activity from cells transfected with pCMV110 and PSG-VP16 was assigned as 100.

ZAS3-dependent transcription was studied by using a heterologous system to differentiate DNA binding from transactivation. Plasmid pSG-ZASC expressed the GAL4 DNA-binding domain fused to the carboxyl one-third of the ZAS3 protein, including an acidic domain. Acidic domains are commonly found in transcription factors and may interact with the basal transcription machinery, transactivators, or adaptor molecules (29). Another plasmid, pSG-VP16, was similar to pSG-ZASC, except that the ZAS3 sequences were replaced with the transactivation domain of VP16. VP16 is a strong transcriptional activator in mammalian cells (30). In this study, expression vectors were cotransfected with a reporter plasmid pCMV110, which contains four copies of GAL4-binding sites upstream of the bacterial chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT) gene, into a monkey kidney cell line, Cos-7. Expression of the CAT reporter was induced ≈50-fold by pSG-VP16 (Fig. 5B). Cotransfection with pSG-ZASC repressed the pSG-VP16-mediated transactivation of pCMV110. As a control, the parental vector, pSG424, containing the GAL4 DNA-binding domain alone did not affect transactivation of pCMV110 by pSG-VP16. The data show that ZAS3 inhibits transactivation of VP16 and suggest that ZAS3 may function as a transcriptional repressor.

Previous studies have implicated ZAS in maintaining normal growth. In Drosophila, expression of shn in cyst cells restricts proliferation and mitosis of neighboring germ cells (31). Similarly, down-regulation of ZAS3 by an antisense construct generally accelerated the growth of cell lines (32). In HeLa cells, ZAS3 deficiency led to anchorage-independent growth and the formation of multinucleated giant cells, in which nuclear division occurred without cell divisions. Gene knockout experiments further show that ZAS2 and -3 are required for thymocyte maturation (15, 33). Several developmental anomalies, including tumorigenesis, polydactyly, and hydronephrosis, were observed in ZAS3–/–RAG2–/– chimeric mice (15). In addition, those mice showed a progressive depletion of CD4+CD8+ double-positive thymocytes, suggesting ZAS3 is important for the survival of T lymphocytes. Similarly, ZAS2 knockout mice were severely depleted of CD4+ and CD8+ single-positive cells, a defect contributed to failed positive selection (33). In addition, ZAS proteins have been implicated in signal transduction. Shn associates with Mad/Smad to modulate decapentaplegic/transforming growth factor β signaling during embryonic development (7). ZAS3 associates with TRAF2 to repress the TNF/NF-κB signal pathway (8). Furthermore, changes in gene expression of ZAS genes have been associated with poor prognosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients (34). We speculate that ZAS3 may have a tumor suppression function.

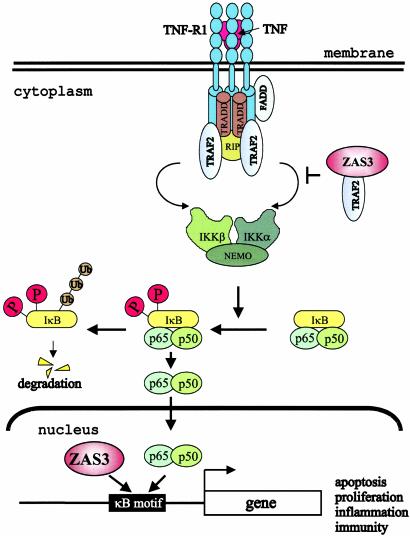

Here, we have shown that the subcellular localization of p65 and hence the major transactivation activity of NF-κB are modulated by ZAS3. A model for ZAS3 to regulate cellular homeostasis is shown in Fig. 6. We propose that, whereas NF-κB activates transcription, ZAS3 mostly represses transcription. In unstimulated cells, ZAS3 is responsible, at least in part, for guarding against aberrant NF-κB-mediated transactivation and does so judiciously via multiple checkpoints: by inhibiting the nuclear localization of p65, by competing for cis-acting κB gene regulatory elements, and by serving as a transcriptional repressor. In conclusion, this study establishes the groundwork for the ZAS family of zinc-finger proteins as governors of NF-κB-mediated cell functions including apoptosis, proliferation, inflammation, and immunity.

Fig. 6.

A model of ZAS3 in inhibiting NF-κB. In the nucleus, ZAS3 interferes with NF-κB-mediated transcription by competing for κB gene regulatory elements and by repressing transcription. In the cytoplasm, ZAS3, most likely a protein isoform, inhibits the nuclear translocation of p65 by association with TRAF2, which blocks the formation of the IKK complex. TRADD, TNF receptor (TNFR)-associated death domain; RIP, receptor-interacting protein; TRAF2, TNFR-associated factor 2; FADD, Fas-associated death domain; IKK, IκB kinase; and NEMO, NF-κB essential modulator.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. D. Guttridge for plasmids 3×κB-Luc, p50 and p65, NF-κB antibodies, and p65–/– and p65+/+ MEFs; Dr. T. Hai (Ohio State University) for HEK 293 cells; Dr. E. Clark (University of Washington, Seattle) for p7×κB; and Dr. M. Ptashne (Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center, New York) for pSG424 and pCMV110. This work was supported in part by a grant from the American Cancer Society, Ohio Division.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: TNF, tumor necrosis factor; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; EMSA, electrophoretic mobility-shift assay; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; IκB, inhibitor κB; IKK, IκB kinase; HEK, human embryonic kidney.

References

- 1.Li, Q. & Verma, I. M. (2002) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 725–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldwin, A. S., Jr. (1996) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 14, 649–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sen, R. & Baltimore, D. (1986) Cell 47, 921–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osborn, L., Kunkel, S. & Nabel, G. J. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 2336–2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu, L. C. (2002) Gene Expr. 10, 137–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu, L. C., Liu, Y., Strandtmann, J., Mak, C. H., Lee, B., Li, Z. & Yu, C. Y. (1996) Genomics 35, 415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Affolter, M., Marty, T., Vigano, M. A. & Jazwinska, A. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 3298–3305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oukka, M., Kim, S. T., Lugo, G., Sun, J., Wu, L. C. & Glimcher, L. H. (2002) Mol. Cell 9, 121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh, H., LeBowitz, J. H., Baldwin, A. S., Jr., & Sharp, P. A. (1988) Cell 52, 415–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu, L. C., Mak, C. H., Dear, N., Boehm, T., Foroni, L. & Rabbitts, T. H. (1993) Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 5067–5073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rattner, A., Korner, M., Walker, M. D. & Citri, Y. (1993) EMBO J. 12, 4261–4267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moerman, A. M., Mao, X., Lucas, M. M. & Barger, S. W. (1999) Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 67, 303–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hjelmsoe, I., Allen, C. E., Cohn, M. A., Tulchinsky, E. M. & Wu, L. C. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 913–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mao, X., Moerman, A. M. & Barger, S. W. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 44911–44919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen, C. E., Muthusamy, N., Weisbrode, S. E., Hong, J. W. & Wu, L. C. (2002) Genes Chromosomes Cancer 35, 287–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berberich, I., Shu, G. L. & Clark, E. A. (1994) J. Immunol. 153, 4357–4366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guttridge, D. C., Albanese, C., Reuther, J. Y., Pestell, R. G. & Baldwin, A. S., Jr. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 5785–5799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadowski, I. & Ptashne, M. (1989) Nucleic Acids Res. 17, 7539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu, J., Sen, R. & Rothstein, T. L. (1993) Mol. Immunol. 30, 479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mann, K. K., Doerre, S., Schlezinger, J. J., Sherr, D. H. & Quadri, S. (2001) Mol. Pharmacol. 59, 302–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staehling-Hampton, K., Laughon, A. S. & Hoffmann, F. M. (1995) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 121, 3393–3403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mak, C. H., Li, Z., Allen, C. E., Liu, Y. & Wu, L. (1998) Immunogenetics 48, 32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hicar, M. D., Robinson, M. L. & Wu, L. C. (2002) Genesis 33, 8–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmitz, M. L., Bacher, S. & Kracht, M. (2001) Trends Biochem. Sci. 26, 186–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen, L. F., Mu, Y. & Greene, W. C. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 6539–6548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helenius, M., Kyrylenko, S., Vehvilainen, P. & Salminen, A. (2001) Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 3, 147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanaka, K., Matsumoto, Y., Nakatani, F., Iwamoto, Y. & Yamada, Y. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 4428–4435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 28.Fukuda, S., Yamasaki, Y., Iwaki, T., Kawasaki, H., Akieda, S., Fukuchi, N., Tahira, T. & Hayashi, K. (2002) J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 131, 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ptashne, M. (1988) Nature 335, 683–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sadowski, I., Ma, J., Triezenberg, S. & Ptashne, M. (1988) Nature 335, 563–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matunis, E., Tran, J., Gonczy, P., Caldwell, K. & DiNardo, S. (1997) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 124, 4383–4391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen, C. E. & Wu, L. C. (2000) Exp. Cell Res. 260, 346–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takagi, T., Harada, J. & Ishii, S. (2001) Nat. Immunol. 2, 1048–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aalto, Y., El Rifa, W., Vilpo, L., Ollila, J., Nagy, B., Vihinen, M., Vilpo, J. & Knuutila, S. (2001) Leukemia 15, 1721–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Molitor, J. A., Walker, W. H., Doerre, S., Ballard, D. W. & Greene, W. C. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 10028–10032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korner, M., Rattner, A., Mauxion, F., Sen, R. & Citri, Y. (1989) Neuron 3, 563–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cauley, K. & Verma, I. M. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 390–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tewari, M., Dobrzanski, P., Mohn, K. L., Cressman, D. E., Hsu, J. C., Bravo, R. & Taub, R. (1992) Mol. Cell. Biol. 12, 2898–2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pomerantz, J. L. & Baltimore, D. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 6694–6704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]