Abstract

T helper (Th) lymphocytes can develop memory for the expression of particular cytokines, like IL-4 or IL-10, in that reexpression of those cytokines is independent of the original costimulatory signal IL-4 and depends only on T cell receptor stimulation. Here, we show that in the course of Th2 cell differentiation in vitro, IL-4 memory is established during primary activation of naïve Th cells, whereas the establishment of IL-10 memory requires repetitive stimulation of the Th cell with IL-4 and T cell receptor. Likewise, established IL-10 memory, maintained in the absence of further IL-4 signals, was observed in individual IL-10-producing cells generated from in vivo antigen-experienced CD62Llow Th cells and isolated by using the newly developed cytometric cytokine secretion assay for IL-10. In naïve Th cells undergoing primary activation, the induction of both IL-4 and IL-10 memory requires DNA synthesis, but reexpression of the cytokine genes can occur throughout cell cycle. In in vitro polarized Th2 cell populations, Th cells with IL-4 or IL-10 memory do not differ in proliferative behavior. Populations of Th cells isolated from polarized Th2 cultures according to expression of IL-4 or IL-10 also do not differ in proliferative behavior. Their proliferation mainly depends on IL-2. Thus, effector memory Th lymphocytes with memory for IL-4 or IL-10 expression are not intrinsically impaired in their proliferative potential and can play an essential role in reactive immunological memory and its regulation.

Interleukin (IL)-4 drives naïve CD4+ T cells to initiate the T helper (Th) 2 developmental program associated with transient secretion of IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13 (1). Th2 cells develop memory for the expression of Th2 cytokines. Whereas the initial expression of IL-4 and IL-10 in primary activated Th cells depends on T cell receptor (TCR) signaling and costimulation with IL-4, reexpression of Th2 cytokines in antigen (Ag)-experienced cells depends only on TCR signaling (2, 3). Little is known, however, about the induction and subsequent fidelity of IL-4 and IL-10 memory in individual cells. Several groups have shown that the induction of memory for effector cytokines, like IFN-γ, IL-4, or IL-10, depends on entry of a naïve Th cell into the S phase of the first cell cycle upon primary activation (4–6) and that drugs interfering with DNA methylation and chromatin rearrangement also interfere with the induction of cytokine memory (4, 7). In Ag-experienced Th cells with memory for particular cytokine genes, these genes are epigenetically marked by demethylation, histone acetylation, and opening of chromatin (3). Moreover, up-regulation of the transcription factor GATA-3 is a critical characteristic of Th cells with IL-4 memory (8). It is still not clear in molecular detail how epigenetic modification and enhanced expression of key transcription factors are connected to establish IL-4 memory (3, 9), whereas for IL-10 memory, not even epigenetic modifications have been demonstrated so far (10). Here, we have compared the induction of IL-4 and IL-10 memory on the level of individual cells in terms of the requirement for IL-4 costimulation and the fidelity of reexpression, both in naïve Th cells undergoing primary activation in vitro and Ag-experienced Th cells isolated ex vivo.

IL-4 signals transmitted via signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (Stat6) drive not only Th2 differentiation but also proliferation of Th2 cells (11). This occurs at least in part because of an IL-4/Stat6-dependent induction of the transcriptional repressor growth factor independent-1 (Gfi-1), which in conjunction with GATA-3 increases the expansion of Th2 populations by promoting proliferation and reducing apoptosis (12). In contrast, in CD4+ bulk cultures containing predominantly IL-10-producing cells, a low proliferative activity has been reported (13, 14). This may be caused by low stimulatory activity of the Ag-presenting cells (APCs) as a consequence of their exposure to IL-10 (15–17). Alternatively, the impaired proliferation of these IL-10-producing cells could be an intrinsic part of their differentiation (18, 19). Here, we have determined the proliferation of individual IL-4- or IL-10-producing and nonproducing cells by two approaches. First, we determined the proliferative history of Th2 cells with IL-4 or IL-10 memory. Second, we adapted the cytometric IL-4 secretion assay (20–22) to the isolation of cells with IL-10 memory. We then compared proliferation of Th cell populations separated according to secretion of IL-4 or IL-10.

Materials and Methods

Mice. Mice transgenic for the ovalbumin (OVA)323–339-specific DO11.10 α/β TCR (OVA-TCR) (23) were from D. Loh (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis) and were maintained on the BALB/c background under specific pathogen-free conditions.

Separation of Naïve CD62Lhigh and in Vivo Ag-Experienced CD62Llow CD4+ T Cells. DO11.10 splenocytes were stained with anti-CD4 FITC (GK1.5; American Type Culture Collection) and MultiSort anti-FITC microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). CD4+ cells were isolated by magnetic cell sorting (MACS) with the MidiMACS system. After release of the MultiSort beads, CD4+ cells were stained with anti-CD62L microbeads and separated into CD62Lhigh and CD62Llow fractions. CD62Lhigh CD4+ cells were purified to >99%, as determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis after staining with anti-CD62L phycoerythrin (PE) (MEL-14; American Type Culture Collection). T cells were labeled with 5- and 6-carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Molecular Probes) as described (5).

T Cell Activation, Phenotype Differentiation, and Cell-Cycle Inhibition. Cell cultures were set up with 2 × 106 cells per ml in complete RPMI medium 1640 (cRPMI; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), containing 10% FCS (Sigma), 10 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 units/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin, and 0.3 mg/ml Gln (GIBCO/BRL). OVA323–339 (Neosystem, Strasbourg, France) was used at 0.3–0.5 μM. CD90-depleted splenocytes were used as APCs for DO11.10 T cells at a 5:1 ratio. For phenotype differentiation, IL-12 (1 ng/ml; gift from M. Gately, Hoffmann–La Roche, Nutley, NJ) and/or IL-4 (20–30 ng/ml; supernatant of IL-4 cDNA-transfected P3-X63 Ag8.653) plus anti-IL-12 (C17.8; 5 μg/ml; BD Biosciences) and anti-IFN-γ (AN18.17.24; 5 μg/ml; BD Biosciences) were added where indicated. Cell cultures were split on day 2 or 3. Human IL-2 (50 units/ml; Hoffmann–La Roche) or anti-IL-2 (JES6-5H4; 10 μg/ml; BD Biosciences), anti-IL-4 (11B11; 5–10 μg/ml; American Type Culture Collection), and anti-IL-10 (JES5-2A5; 5–10 μg/ml; BD Biosciences) were used where indicated. Cell-cycle progression was inhibited by supplement of mycophenolic acid (1 μM; Sigma) or paclitaxel (200 nM; ICN). Daily, the cells were counted and FACS-analyzed for CFSE vs. propidium iodide staining to determine the survival rate, which was ≈50% of the originally seeded cells after 3 days with or without inhibitors. Further, expression of activation markers (CD69, CD25, CD44, and CD62L) was analyzed daily by FACS and was found to be very similar in all cultures (data not shown).

Identification of Live IL-4- or IL-10-Secreting Cells with the Cytometric Cytokine Secretion Assay. Th2-primed DO11.10 T cells from CD62Lhigh or CD62Llow origin were activated either with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (10 ng/ml) and ionomycin (1 μg/ml; Sigma) at 2 × 106 cells per ml or with OVA323–339 (0.5 μM) plus erythrocyte-lysed irradiated (3,000 rad) BALB/c splenocytes at 1:4 ratio in cRPMI. Neutralizing mAbs to IL-4, IL-12, and IFN-γ were added. After 2.5 h (IL-4 assay) or 3.5 h (IL-10 assay) of stimulation with PMA/ionomycin or after 4–4.5 h of antigenic stimulation, cells were washed twice in ice-cold PBS with 0.5% BSA (PBS/BSA). Ice-cold cells were labeled for 5 min at 4°C with an IL-4- or IL-10-specific high-affinity capture matrix, i.e., bispecific Ab-Ab conjugates of an anti-CD45 mAb (30-F11) with either an anti-IL-4 mAb (BVD6-24G2) or an anti-IL-10 mAb (JES5-2A5 or JES5-16E3; 30–50 μg/ml; Miltenyi Biotec). At this point, small cell samples were taken for low control (cells kept on ice in PBS/BSA) and high control [cells incubated with recombinant IL-4 (0.3 μg/ml) or IL-10 (0.5–1 μg/ml); Pepro Tech]. Controls were washed after 10 min and kept on ice. The remaining cells were transferred to 37°C warm cRPMI at 2 × 105 cells per ml and placed in a 37°C water bath. After 20 min (IL-4 assay) or 30 min (IL-10 assay) with gentle mixing every 10 min, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS/BSA. Matrix-captured IL-4 or IL-10 was detected with anti-IL-4 (BVD4-1D11) or anti-IL-10 (JES5-16E3 or JES5-2A5) coupled to PE (3–5 μg/ml; Miltenyi Biotec) for 10 min on ice. Controls were stained the same. For FACS analysis, controls and small cell samples from the IL-4 and IL-10 secretion assays were stained with anti-CD4 FITC and anti-OVA-TCR Cy5 (KJ1-26). Immediately before FACS analysis, propidium iodide (0.3 μg/ml; Sigma) was added to stain dead cells. Samples were analyzed on a FACSCalibur by using cellquest software (BD Biosciences). Analysis gates were set on live lymphocytes by forward and side scatter and exclusion of propidium iodide-binding particles.

Sorting of Live IL-4- or IL-10-Secreting and Nonsecreting Cells. The cells, on the surface of which secreted IL-4 or IL-10 was labeled with PE anti-IL-4 or anti-IL-10, were incubated with anti-PE microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) at 1:5 dilution for 15 min at 10°C. Cells were washed and passed over a “mock” LS MACS column (Miltenyi Biotec) not inserted into the magnetic field to remove cells that bound nonspecifically to the column. IL-4+ or IL-10+ cells were obtained by two consecutive passes over LS columns in a MidiMACS magnet. IL-4– or IL-10– fractions were again incubated with anti-PE beads at 1:3 dilution, washed, and applied on a LS column to which a 25-gauge needle was attached to restrict the flow rate, yielding highly purified IL-4– or IL-10– cells. Purity was controlled by FACS after staining for CD4 and OVA-TCR. Sorted cells were labeled with CFSE and maintained in cRPMI with human IL-2 and neutralizing mAbs to IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, and IFN-γ. Where indicated, murine IL-4 and mAbs to IL-10, IL-12, and IFN-γ were used.

FACS Analysis of Intracellular Cytokines and DNA. T cells were restimulated either with OVA323–339 plus BALB/c splenocytes at 5 × 106 cells per ml or with PMA/ionomycin at 2 × 106 cells per ml in cRPMI. Unless otherwise indicated, brefeldin A (5 μg/ml; Sigma) was added after 2 h. After 4–5 h of restimulation, cells were washed, fixed with 2% formaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature, and stained for CD4 or OVA-TCR and for intracellular cytokines as described (24). To costain intracellular cytokines and DNA, freshly fixed cells were incubated with RNase A (100 μg/ml; Sigma) at 1 × 106 cells per ml in PBS/BSA for 1 h in a 37°C water bath. After washing in PBS/BSA, cells were stained for OVA-TCR and intracellular cytokines using digoxigenized anti-cytokine mAbs followed by anti-digoxigenin Fab (Roche Applied Science) coupled to Cy5. Some minutes before FACS analysis, DNA was stained with propidium iodide (40 μg/ml).

Results

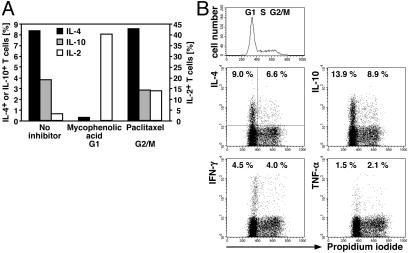

Induction of IL-4 and IL-10 Memory Is Cell Cycle-Dependent. To address the proliferation and cell-cycle requirements for the induction of memory for IL-4 and IL-10 expression, we activated CFSE-labeled naïve DO11.10 T cells under Th2 conditions with or without cell-cycle inhibitors. After 3 days, cells were restimulated for cytokine analysis. The transgenic T cells maintained without inhibitor had divided up to five times as was evident from the stepwise decrease in CFSE labeling intensity, whereas the cells maintained with an inhibitor had not divided (data not shown). In accordance with our earlier observation using l-mimosine as inhibitor (5), we found that the induction of IL-4 and IL-10 memory in naïve Th cells undergoing primary activation was completely blocked also by mycophenolic acid (Fig. 1A), i.e., by drugs blocking DNA synthesis and entry of the activated T cell into the S phase of the first cell cycle. Paclitaxel, which blocks at a later stage of that first cell cycle, did not significantly inhibit the induction of cytokine memory. This result could reflect either the necessity of epigenetic modifications of cytokine genes for memory expression or restriction of memory expression to late phases of the cell cycle.

Fig. 1.

Induction of IL-4 and IL-10 memory, but not memory expression of IL-4 and IL-10, is cell cycle-dependent. (A) Sorted naïve CD62Lhigh CD4+ DO11.10 cells were labeled with CFSE and activated with OVA323–339, APCs, IL-4, anti-IL-12, and anti-IFN-γ in the presence or absence of drugs arresting cell-cycle progression either early, in G1 phase (mycophenolic acid), or late, in G2/M phase (paclitaxel). After 3 days, cells were restimulated with PMA/ionomycin for 5 h, fixed, and stained for OVA-TCR (KJ1-26) and intracellular cytokines. The indicated frequencies of cytokine+ cells among OVA-TCR+ cells are corrected for the values obtained in the respective isotype control stainings. Frequencies of IL-10+ cells among T cells inhibited with mycophenolic acid were below the detection limit of 0.2%. (B) CD62Lhigh CD4+ DO11.10 cells were stimulated with OVA323–339, APCs, IL-4, and IL-12. On day 4, cells were restimulated with PMA/ionomycin, fixed, RNase A-treated, and stained for intracellular cytokines with fluorescent mAbs and for DNA content with propidium iodide. Analysis gates were set on OVA-TCR+ cells. The frequencies of cytokine+ T cells among cells in G1 phase or in S and G2/M phase are given. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

Memory Expression of IL-4 and IL-10 Is Independent of Cell-Cycle Phase. To analyze the correlation between cell cycling and cytokine expression, we performed direct costainings of cytokines and DNA content in individual cells that had been primed in the presence of IL-4 and IL-12 and restimulated on day 4, when the vast majority of the transgenic T cells had divided several times as judged by loss of CFSE (data not shown). The DNA staining allowed clear classification of the cell-cycle phases (Fig. 1B Upper). We observed substantial production of IL-4, IL-10, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor α in Th cells in G1, S, and G2/M phase (Fig. 1B Lower). The frequencies of cytokine+ cells were not significantly different in the various cell-cycle phases. Thus, in Th cells that have divided several times, cytokine expression is not restricted to particular phases of the cell cycle.

Separation of IL-4- or IL-10-Secreting and Nonsecreting T Cells. To test the stability of IL-4 and IL-10 memory, we established the cytometric cytokine secretion assay for murine IL-10. This requires precise knowledge of the kinetics of cytokine production, which we determined in 6-day IL-4-primed cells, restimulated either with PMA/ionomycin or OVA323–339 and APCs. Both restimulation protocols yielded a largely similar pattern of cytokine production with similar kinetics, with a slight delay after antigenic restimulation. With PMA/ionomycin, we observed the highest frequencies of cytokine+ T cells after 3–4 h (Fig. 2A) and with OVA323–339 after 4–6 h (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Separation of IL-4- or IL-10-secreting and nonsecreting T cells. (A and B) Kinetics of cytokine production after restimulation. DO11.10 T cells were stimulated with OVA323–339, APCs, and IL-4. On day 6, cytokine production kinetics were determined after restimulation with PMA/ionomycin (A) or OVA323–339 and fresh BALB/c splenocytes (B). At the time points indicated, cell samples were fixed (without any addition of brefeldin A beforehand) and stained for intracellular cytokines. The staining background of the isotype controls at the indicated time points of restimulation has been subtracted from the respective frequencies of cytokine+ cells among OVA-TCR+ cells. (C) Cytometric cytokine secretion assays for IL-4 and IL-10. CD62Lhigh CD4+ DO11.10 cells were activated with OVA323–339, APCs, IL-4, anti-IL-12, and anti-IFN-γ for 5 days before their separation according to IL-4 secretion. For the IL-10 assay, CD4+ DO11.10 cells were stimulated alike for 7 days. Then, cells were reactivated with PMA/ionomycin for 2.5 h (IL-4 assay) or 3.5 h (IL-10 assay). Upon labeling with the respective capture matrices, IL-4- or IL-10-secreting cells were identified after a secretion period at 37°C of 20 min (IL-4 assay) or 30 min (IL-10 assay) (Top Center). The frequencies of IL-4- or IL-10-producing cells were determined in parallel by intracellular staining of the same cell populations after 4–5 h of restimulation with PMA/ionomycin (Top Left and Right). Samples of the capture matrix-labeled cells were either incubated with recombinant IL-4 or IL-10 to control the homogeneous labeling with the respective capture matrices (high control; Middle Left and Right) or were put immediately in ice-cold medium to prevent secretion (low control; Bottom Left and Right). The cytokine+ and cytokine– cells were separated by MACS (Middle and Bottom Center).

For the cytometric cytokine secretion assay (20–22), 5- to 7-day Th2-polarized cells were reactivated to stimulate cytokine reexpression and labeled with bispecific Ab–Ab conjugates consisting of anti-CD45 and anti-IL-4 or anti-IL-10 to generate a high-affinity capture matrix for IL-4 or IL-10. The secreted cytokines, retained on the surface of the secreting cell, were then detected by fluorochrome-labeled cytokine-specific mAbs and specific magnetic particles. The frequencies of cells positive for secreted IL-4 (11.7%; Fig. 2C Top Center) or IL-10 (21.5%) were similar to the frequencies of IL-4- or IL-10-producing cells found by intracellular staining (12.1% IL-4+ and 22.9% IL-10+ cells; Fig. 2C Top Left and Right). Exogenous loading of the capture matrices with recombinant IL-4 or IL-10 showed that all cells were homogeneously labeled with the respective matrix and thus had the capacity to capture IL-4 or IL-10 (Fig. 2C, high control). When the cells were put in ice-cold medium instead of 37°C medium, almost no IL-4- or IL-10-secreting cells were detected (Fig. 2C, low control). By MACS, cytokine-secreting and nonsecreting cells were purified to ≥97% (Fig. 2C Middle and Bottom Center).

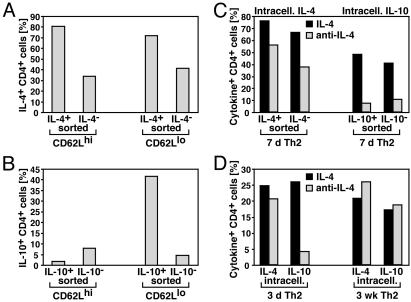

Stability of IL-4 and IL-10 Memory in Naïve and Ag-Experienced T Cells. We used the cytokine secretion assay to compare the stability of IL-4 and IL-10 memory in T cells in which cytokine expression had been induced only recently in vitro, with cells in which memory for cytokine expression had been established in vivo. For this, naïve CD62Lhigh cells and Ag-experienced CD62Llow cells were stimulated under Th2 conditions. After restimulation on days 6–7, IL-4- or IL-10-secreting and nonsecreting T cells were sorted as in Fig. 2C, maintained with mAbs to IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, and IFN-γ for 6–7 days and then restimulated for intracellular cytokine cytometry. Of the sorted IL-4+ cells (purity 95–97%) 72–81% reexpressed IL-4 after 6 days of culture with anti-IL-4 (Fig. 3A). Of the sorted IL-4– cells (purity 99%) 34–42% expressed IL-4 under the same conditions. No differences in IL-4 memory were observed between T cells from CD62Lhigh or CD62Llow origin. Of IL-10+ cells (purity 93%) from CD62Lhigh origin, only 2% reexpressed IL-10 after culture in anti-IL-4 and anti-IL-10, indicating that stable IL-10 memory had not yet been established (Fig. 3B). This was different for IL-10+ cells (purity 86%) from CD62Llow origin; 42% of those cells reexpressed IL-10 after culture without IL-4 and IL-10. Of the IL-10– fraction (purity 98%), only 4% expressed IL-10. Thus, in IL-10+ cells generated from in vivo Ag-experienced T cells, IL-10 memory was maintained for at least 7 days in the presence of mAbs to IL-4 and IL-10, and sorted IL-10– T cells stably remained IL-10– under these conditions.

Fig. 3.

In recently induced cytokine-producing cells, IL-10 but not IL-4 memory is largely IL-4-dependent. (A and B) Sorted naïve CD62Lhigh and in vivo Ag-experienced CD62Llow CD4+ DO11.10 cells were stimulated with OVA323– 339, APCs, IL-4, anti-IL-12, and anti-IFN-γ. After 6–7 days, cells were restimulated, and IL-4-secreting (A) or IL-10-secreting (B) and nonsecreting T cells were sorted as in Fig. 2C. Sorted cells were maintained in medium with IL-2 and mAbs to IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, and IFN-γ. After 6–7 days, production of IL-4 (A) and IL-10 (B) was analyzed by intracellular cytometry after 4 h of restimulation with PMA/ionomycin. The frequencies of IL-4+ or IL-10+ cells among CD4+ cells are indicated. Results are representative of three independent experiments for IL-4 and two of three independent experiments for IL-10. In the third experiment, IL-10 memory in T cells from CD62Llow origin was less stable, as only 13.2% of the sorted IL-10+ cells maintained IL-10 production as compared with 0.8% of the sorted IL-10– cells. (C and D) CD62Lhigh CD4+ DO11.10 cells were stimulated with OVA323–339, APCs, IL-4, anti-IL-12, and anti-IFN-γ. (C) After 7 days, cells were restimulated, and IL-4- or IL-10-secreting and nonsecreting T cells were sorted as in Fig. 2C. Sorted cells were split, and half were maintained with IL-4 and mAbs to IL-10, IL-12, and IFN-γ (IL-4; black bars), whereas the other half received IL-2 and mAbs to IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, and IFN-γ (anti-IL-4; gray bars). After 7 days, production of IL-4 or IL-10 was analyzed by intracellular cytometry after 4 h of restimulation with PMA/ionomycin. (D) After 3 days and ≈3 weeks with two Th2-polarizing stimulations, cells were split, restimulated, and expanded for another week in IL-4 and anti-IL-4 as in C. The frequencies of IL-4+ and IL-10+ cells among CD4+ cells are indicated.

Establishment of IL-10 Memory Depends on Repetitive Costimulation with IL-4. We tested whether the neutralization of IL-4 in the maintenance culture was responsible for the observed lack of stable IL-10 memory in sorted IL-10+ cells from naïve origin. For this, we activated naïve cells under Th2 conditions. After 7 days, we sorted IL-4- or IL-10-secreting T cells as in Fig. 2C. One-half of the sorted cells was maintained with IL-4 and mAbs to IL-10, IL-12, and IFN-γ, whereas the other half received IL-2 and mAbs to IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, and IFN-γ. Another 7 days later, cytokine production was analyzed. When sorted IL-4+ cells (purity 96%) were maintained with anti-IL-4 or IL-4, 56–76% reexpressed IL-4 (Fig. 3C). Thus, already in recently induced IL-4+ cells, IL-4 memory is largely IL-4 independent. In contrast, when sorted IL-10+ cells (purity 95%) were maintained with anti-IL-4, only 7% reexpressed IL-10 a week later, as compared with 48% after maintenance with IL-4 (Fig. 3C). This shows that the capacity to express IL-10 of recently induced IL-10+ cells depends largely on continuous IL-4 signals.

We wondered whether the stability of IL-10 memory in in vivo Ag-experienced CD62Llow T cells (Fig. 3B) may be caused by a history of repetitive stimulations under IL-10-inducing conditions. We tested this for T cells stimulated in vitro repeatedly and maintained for a longer time. In Th cells primed with IL-4 for 3 days, restimulation and further culture in IL-4 increased the frequency of IL-10+ T cells >6-fold compared with cells restimulated and expanded in anti-IL-4 (Fig. 3D). In contrast, in Th2 cells differentiated with IL-4 for ≈3 weeks, the frequencies of IL-10+ T cells were virtually identical after culture in IL-4 or anti-IL-4. Thus, in long-term differentiated, but not in recently induced, Th2 cells, IL-10 memory is independent of further IL-4 signals. As expected, the frequencies of IL-4+ T cells were very similar in Th2 cells upon culture in IL-4 or anti-IL-4, after 3 days and after 3 weeks (Fig. 3D), confirming the IL-4 independence of IL-4 memory already shortly after the initial polarizing activation (25).

Proliferation of T Cells in Relation to Their Cytokine Memory. To test whether the proliferation of individual T cells is related to their capacity to produce cytokines, we labeled 6-day Th2-polarized cells with CFSE and restimulated with Ag. On the following 2–6 days, cell samples were reactivated for cytokine cytometry. We analyzed T cells that did or did not coexpress IL-4 and IL-10 (regions 1–4 in Fig. 4A Upper) for their proliferative history (Fig. 4A Lower). Individual generations of proliferating T cells were clearly distinguishable. Cells with or without the capacity to express IL-4 and/or IL-10 upon restimulation had proliferated to the same degree. The same was found for T cells that did or did not express IL-2 in combination with either IL-4 or IL-10 (data not shown). Thus, the proliferation of a Th2-primed cell in vitro is independent of its individual cytokine memory, under conditions of constant cocultivation.

Fig. 4.

Similar proliferation of IL-4- or IL-10-producing and nonproducing T cells. (A) The proliferation of a Th2-primed cell is independent of its cytokine memory. CD62Lhigh CD4+ DO11.10 cells were activated with OVA323–339, APCs, IL-4, anti-IL-12, and anti-IFN-γ. On day 6, cells were labeled with CFSE and restimulated with OVA323–339, APCs, anti-IL-12, and anti-IFN-γ. On the following 2–6 days, cell samples were reactivated with PMA/ionomycin for 5 h and stained intracellularly for IL-4 vs. IL-10. Analysis gates were set on OVA-TCR+ cells that did or did not coexpress IL-4 and IL-10 (Upper). The CFSE proliferation profiles of the four subpopulations are shown (Lower). (B) Similar proliferation of sorted IL-4- or IL-10-producing and nonproducing T cells. CD4+ DO11.10 cells that had been activated as in A for 5–7 days were sorted into IL-4- or IL-10-secreting and nonsecreting cells (Fig. 2C), labeled with CFSE, and maintained with IL-2 and mAbs to IL-4, IL-12, and IFN-γ for 5 days. Daily, the proliferation of the sorted IL-4 or IL-10 positive (bold line) and negative (thin line) T cells was analyzed. Analysis gates were set on OVA-TCR+ cells. Note the ≈1.5-fold weaker initial CFSE labeling of the sorted IL-4– cells compared with the IL-4+ cells (upper left), which likely accounts for the slightly lower CFSE intensities of the IL-4– cells at the later time points. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

Proliferation of Isolated IL-4- or IL-10-Producing and Nonproducing T Cells. IL-4- or IL-10-secreting and nonsecreting cells separated from 5- to 7-day Th2-polarized cultures (purity ≥97%; Fig. 2C) were labeled with CFSE and maintained in culture with IL-2 and mAbs to IL-4, IL-12, and IFN-γ for 5 days. Proliferation was analyzed daily (Fig. 4B). Cells of all four sorted populations started to divide during the first 2 days of culture and continued to proliferate until day 5. At all time points analyzed, the sorted IL-4+ and IL-4– T cells and the sorted IL-10+ and IL-10– T cells proliferated virtually identically. Also, the increases in cell numbers of the sorted populations were comparable. T cell proliferation depended on IL-2, because neutralization of IL-2 with mAbs inhibited proliferation completely (data not shown). IL-10 memory in the sorted IL-10+ T cells, which were derived from total CD4+ cells including the CD62Llow cells, was maintained throughout the proliferation analysis; upon restimulation on day 6, 30% of the sorted IL-10+ cells reexpressed IL-10 as compared with only 2.5% of the sorted IL-10– cells (data not shown). Thus, neither expression of IL-4 nor of IL-10 by an individual T cell directly influences the proliferation of the very same cell in vitro, nor is it linked to a distinct program of hyper- or hypoproliferation.

Discussion

Here, we have analyzed memory of Th lymphocytes for expression of IL-10, a key player in the regulation of immune responses (10) and a hallmark of T regulatory 1 (Tr1) cells (13, 14, 26–29). Despite its physiological relevance, little is known about the transcriptional control of the IL-10 gene and the memory of Th cells to express it.

Induction of IL-10 Memory Requires DNA Synthesis. Drugs inhibiting progression of naïve Th cells into the S phase of the first cell cycle inhibited efficiently the induction of memory for IL-4 and also for IL-10 (Fig. 1 A and ref. 5). This might have reflected a restriction of cytokine production to certain cell-cycle phases. Here, we show that in Th cells that have divided several times, production of effector cytokines, including IL-10, is not restricted to particular cell-cycle phases. This strengthens the argument for a requirement of DNA synthesis-dependent epigenetic modifications of either the cytokine genes or genes controlling their expression in the induction of memory for effector cytokines (3–7). Thereupon, memory expression of the cytokine genes would be independent of the original inducing signal(s), e.g., IL-4, and depend only on TCR signals.

Establishment of IL-10 Memory Requires Extended Costimulation with IL-4. In sorted IL-4+ cells derived from naïve T cells activated in vitro in the presence of IL-4 for 3–7 days, IL-4 memory can be readily observed as 60–80% of the cells reexpress IL-4 (Fig. 3 and ref. 25). In contrast, in IL-10+ cells isolated from the same T cell cultures, stable IL-10 memory has not yet been established. Upon culture in the absence of the inducing signal IL-4, <10% of the cells reexpress IL-10. However, when naïve Th cells were stimulated for several rounds in the presence of IL-4 in vitro, or when they had been activated in vivo, i.e., CD62Llow cells, ≈50% of the cells reexpressed IL-10 independent of IL-4 costimulation. This suggests a requirement of repetitive costimulation with IL-4 for the establishment of IL-10 memory.

It is remarkable that also the primary expression of IL-10 occurs late after activation of naïve T cells compared with expression of IL-2 and IFN-γ, for reasons unknown (21, 30). Whereas for IL-4 expression, GATA-3 is a critical transcription factor, expression of which is up-regulated by IL-4 (8) and then maintained by autoactivation (22); the transcriptional control of the IL-10 gene is less well understood (10). IL-4 is a potent IL-10 inductor (31), even in Th1 cells at certain stages of their differentiation (32). To some extent, ectopic GATA-3 enhances IL-10 gene expression (22). At the IL-4 gene locus, GATA-3 is sufficient to induce chromatin remodeling, probably a molecular prerequisite of IL-4 memory in T cells (3, 9, 22). The present observation that the establishment of IL-10 memory occurs later in T cell differentiation than that of IL-4 memory, and requires prolonged IL-4 costimulation, suggests that not only up-regulation of GATA-3 but also a more tardy up-regulation of other IL-4/Stat6-dependent factor(s) may be involved in establishing IL-10 memory. Alternatively, it could be speculated that IL-10 memory may require higher GATA-3 concentrations than IL-4 memory. However, in 4-week differentiated Th2 populations, weekly restimulated in the presence of IL-4, GATA-3 expression was only ≈2-fold higher than in 1-week differentiated Th2 populations, as determined by real-time PCR (U. Niesner and A. Radbruch, unpublished results). This is in line with the mathematical model of GATA-3 expression predicting only one stable state of high-level expression (33).

In Vivo Activated Th Cells Show IL-10 Memory in Vitro. In contrast to IL-10+ T cells from naïve origin, those from in vivo Ag-experienced CD62Llow origin reexpress IL-10 also in the absence of IL-4 costimulation, i.e., they have already established IL-10 memory. This was the case in two of three experiments, showing that this is not necessarily so. The analysis of Th cells from IL-4-deficient mice has revealed that IL-4, although being important, nevertheless is not absolutely required for IL-10 induction in vivo, pointing to the existence of alternative pathways (34). Thus, it is conceivable that costimulation by factors other than IL-4, e.g., ICOS or CD46, could also induce IL-10 expression (14, 24, 27–29, 35). The observed variability in vivo may argue in favor of a population of Th cells with a history of repetitive stimulations under IL-10-inducing conditions. Part of the in vivo Ag-experienced cells may thus be comparable to the repeatedly in vitro stimulated naïve T cells, for which we have shown here the establishment of IL-10 memory by repetitive IL-4 costimulation.

IL-10 Memory Is Not Linked to Hypoproliferation. Both IL-4 and IL-10 are known regulators of immune reactions, also by virtue of regulating proliferation (9, 10). Whereas for IL-4, proliferation of T cells is enhanced via Stat6 signaling and Gfi-1 induction (11, 12), for IL-10 a direct impact on T cell proliferation has not yet been demonstrated clearly (13, 14, 18, 19), although it is clear that IL-10 down-regulates T cell proliferation indirectly via APC inhibition (15–17). Here, we show that the proliferation of Th2-polarized cells in vitro is independent of their individual memory to produce IL-2, IL-4, or IL-10, as cells with or without these cytokine memories all proliferated similarly. In these mixed cultures, transeffects could not be excluded. However, populations of sorted IL-4+ or IL-10+ T cells also proliferated and expanded alike and like populations of cells not having this cytokine memory. It could be argued that IL-10+ cells from polarized Th2 cultures may proliferate differently from those existing in vivo. Here, however, also the IL-10+ cells from in vivo Ag-experienced cells showed the same proliferative behavior as the IL-10– cells of the same culture. Addition or neutralization of IL-4 did not affect the proliferation of the sorted IL-4 or IL-10 positive vs. negative T cells generated from either CD62Lhigh or CD62Llow CD4+ cells (data not shown). It should be noted that those cells in vivo with IL-10 memory presumably include the regulatory cells of the Tr1 type (13, 14, 26–29) expressing only IL-10 or IL-10 plus IFN-γ (30, 32, 35), but also Th cells coexpressing IL-10 and IL-4. Accordingly, in sorted and expanded IL-10+ T cells from CD62Llow origin, IL-10 expression was modestly positively associated with expression of IFN-γ and of IL-4 (data not shown). With human CD4+ T cell clones and resting T cells, a direct inhibitory effect of recombinant IL-10 on IL-2 production and T cell proliferation has been observed (18, 19). Here, when IL-2 was neutralized in cultures of Th cells sorted according to expression of IL-4 or IL-10, proliferation was impaired in all cultures, regardless of the cytokine memory of the cells (data not shown).

It has been shown that, in vivo, memory Th cells exist that do not have memory for particular cytokines (36). These “central memory” T cells would convey remarkable functional flexibility to immunological recall responses, especially, if they proliferated more efficiently than T cells with cytokine memory, the “effector memory” T cells. Recent data seem to indicate that Th cells with IFN-γ memory do not expand well in vivo, compared with their negative counterpart, when isolated by the cytokine secretion assay and adoptively transferred (37). It is certainly possible that cells with cytokine memory die due to activation-induced cell death (38, 39). The present finding that in vivo Ag-experienced Th cells with IL-4 or IL-10 memory have the same proliferative capacity as those cells without such a memory, and that this memory, at least for part of the IL-10 memory cells, is likely to reflect repetitive stimulations under IL-10-inducing conditions, argues against the idea that those effector memory Th cells with memory for the expression of particular cytokines do not constitute an essential component of reactive immunological memory.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Siemer, S. Höher, T. Geske, and M. Steinbach for expert technical help, and U. Niesner and H.-D. Chang for helpful discussions. This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant SFB 421, Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung Grant BEO/21/11340, and the Senatsverwaltung für Wissenschaft of Berlin. M.L. was a fellow of the Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes and is now a fellow of the Ernst Schering Research Foundation.

Abbreviations: Ag, antigen; APC, Ag-presenting cell; CFSE, 5- and 6-carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; MACS, magnetic cell sorting; OVA, ovalbumin; PE, phycoerythrin; PMA, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate; TCR, T cell receptor; Th, T helper.

References

- 1.Mosmann, T. R. & Coffman, R. L. (1989) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 7, 145–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang, H., Hu-Li, J., Chen, H., Ben-Sasson, S. Z. & Paul, W. E. (1997) J. Immunol. 159, 3731–3738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Löhning, M., Richter, A. & Radbruch, A. (2002) Adv. Immunol. 80, 115–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bird, J. J., Brown, D. R., Mullen, A. C., Moskowitz, N. H., Mahowald, M. A., Sider, J. R., Gajewski, T. F., Wang, C. R. & Reiner, S. L. (1998) Immunity 9, 229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richter, A., Löhning, M. & Radbruch, A. (1999) J. Exp. Med. 190, 1439–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ben-Sasson, S. Z., Gerstel, R., Hu-Li, J. & Paul, W. E. (2001) J. Immunol. 166, 112–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young, H. A., Ghosh, P., Ye, J., Lederer, J., Lichtman, A., Gerard, J. R., Penix, L., Wilson, C. B., Melvin, A. J., McGurn, M. E., et al. (1994) J. Immunol. 153, 3603–3610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng, W. & Flavell, R. A. (1997) Cell 89, 587–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy, K. M. & Reiner, S. L. (2002) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 933–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore, K. W., de Waal Malefyt, R., Coffman, R. L. & O'Garra, A. (2001) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19, 683–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu, J., Guo, L., Watson, C. J., Hu-Li, J. & Paul, W. E. (2001) J. Immunol. 166, 7276–7281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu, J., Guo, L., Min, B., Watson, C. J., Hu-Li, J., Young, H. A., Tsichlis, P. N. & Paul, W. E. (2002) Immunity 16, 733–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groux, H., O'Garra, A., Bigler, M., Rouleau, M., Antonenko, S., de Vries, J. E. & Roncarolo, M. G. (1997) Nature 389, 737–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jonuleit, H., Schmitt, E., Schuler, G., Knop, J. & Enk, A. H. (2000) J. Exp. Med. 192, 1213–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Waal Malefyt, R., Haanen, J., Spits, H., Roncarolo, M. G., te Velde, A., Figdor, C., Johnson, K., Kastelein, R., Yssel, H. & de Vries, J. E. (1991) J. Exp. Med. 174, 915–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiorentino, D. F., Zlotnik, A., Vieira, P., Mosmann, T. R., Howard, M., Moore, K. W. & O'Garra, A. (1991) J. Immunol. 146, 3444–3451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ding, L., Linsley, P. S., Huang, L. Y., Germain, R. N. & Shevach, E. M. (1993) J. Immunol. 151, 1224–1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taga, K., Mostowski, H. & Tosato, G. (1993) Blood 81, 2964–2971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Waal Malefyt, R., Yssel, H. & de Vries, J. E. (1993) J. Immunol. 150, 4754–4765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manz, R., Assenmacher, M., Pfluger, E., Miltenyi, S. & Radbruch, A. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 1921–1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Assenmacher, M., Löhning, M., Scheffold, A., Manz, R. A., Schmitz, J. & Radbruch, A. (1998) Eur. J. Immunol. 28, 1534–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ouyang, W., Löhning, M., Gao, Z., Assenmacher, M., Ranganath, S., Radbruch, A. & Murphy, K. M. (2000) Immunity 12, 27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy, K. M., Heimberger, A. B. & Loh, D. Y. (1990) Science 250, 1720–1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Löhning, M., Hutloff, A., Kallinich, T., Mages, H. W., Bonhagen, K., Radbruch, A., Hamelmann, E. & Kroczek, R. A. (2003) J. Exp. Med. 197, 181–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu-Li, J., Pannetier, C., Guo, L., Löhning, M., Gu, H., Watson, C., Assenmacher, M., Radbruch, A. & Paul, W. E. (2001) Immunity 14, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asseman, C., Mauze, S., Leach, M. W., Coffman, R. L. & Powrie, F. (1999) J. Exp. Med. 190, 995–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barrat, F. J., Cua, D. J., Boonstra, A., Richards, D. F., Crain, C., Savelkoul, H. F., de Waal Malefyt, R., Coffman, R. L., Hawrylowicz, C. M. & O'Garra, A. (2002) J. Exp. Med. 195, 603–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levings, M. K., Sangregorio, R., Galbiati, F., Squadrone, S., de Waal Malefyt, R. & Roncarolo, M. G. (2001) J. Immunol. 166, 5530–5539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kemper, C., Chan, A. C., Green, J. M., Brett, K. A., Murphy, K. M. & Atkinson, J. P. (2003) Nature 421, 388–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Assenmacher, M., Schmitz, J. & Radbruch, A. (1994) Eur. J. Immunol. 24, 1097–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mendel, I. & Shevach, E. M. (2002) Eur. J. Immunol. 32, 3216–3224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Assenmacher, M., Löhning, M., Scheffold, A., Richter, A., Miltenyi, S., Schmitz, J. & Radbruch, A. (1998) J. Immunol. 161, 2825–2832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Höfer, T., Nathansen, H., Löhning, M., Radbruch, A. & Heinrich, R. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 9364–9368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kopf, M., Le Gros, G., Bachmann, M., Lamers, M. C., Bluethmann, H. & Köhler, G. (1993) Nature 362, 245–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jankovic, D., Kullberg, M. C., Hieny, S., Caspar, P., Collazo, C. M. & Sher, A. (2002) Immunity 16, 429–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sallusto, F., Lenig, D., Förster, R., Lipp, M. & Lanzavecchia, A. (1999) Nature 401, 708–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu, C. Y., Kirman, J. R., Rotte, M. J., Davey, D. F., Perfetto, S. P., Rhee, E. G., Freidag, B. L., Hill, B. J., Douek, D. C. & Seder, R. A. (2002) Nat. Immunol. 3, 852–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayashi, N., Liu, D., Min, B., Ben-Sasson, S. Z. & Paul, W. E. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 6187–6191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Refaeli, Y., Van Parijs, L., Alexander, S. I. & Abbas, A. K. (2002) J. Exp. Med. 196, 999–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]