Abstract

Potential repair by cell grafting or mobilizing endogenous cells holds particular attraction in heart disease, where the meager capacity for cardiomyocyte proliferation likely contributes to the irreversibility of heart failure. Whether cardiac progenitors exist in adult myocardium itself is unanswered, as is the question whether undifferentiated cardiac precursor cells merely fuse with preexisting myocytes. Here we report the existence of adult heart-derived cardiac progenitor cells expressing stem cell antigen-1. Initially, the cells express neither cardiac structural genes nor Nkx2.5 but differentiate in vitro in response to 5′-azacytidine, in part depending on Bmpr1a, a receptor for bone morphogenetic proteins. Given intravenously after ischemia/reperfusion, cardiac stem cell antigen 1 cells home to injured myocardium. By using a Cre/Lox donor/recipient pair (αMHC-Cre/R26R), differentiation was shown to occur roughly equally, with and without fusion to host cells.

Cardiomyocytes can be formed, at least ex vivo, from diverse adult pluripotent cells (1–5). Apart from therapeutic implications and obviating ethical concerns aroused by embryonic stem cell lines, adult cardiac progenitor cells might provide an explanation distinct from cell cycle reentry, for the reported rare occurrence of cycling ventricular muscle cells (6). However, recent publications suggest the failure of certain stem cells' specification into neurons, skeletal muscle, and myocardium in vivo (7, 8) and recommend greater conservatism in evaluating claims of adult stem cell plasticity, for cogent reasons (9–11).

The rarity of cardiogenic conversion by endogenous hematopoietic cells (2, 12), requirements for intracardiac injection (3), or mobilization by cytokines (13), uncertain proof for myocytes of host origin in transplanted human hearts (14), and the confounding possibility of cell fusion after grafting in vivo (15, 16) highlight unsettled issues surrounding stem cell plasticity in heart disease. For donor cell types already in clinical studies, the predominant in vivo effect of bone marrow or endothelial progenitor cells may be neoangiogenesis, not cardiac specification (17, 18), and skeletal myoblasts, despite integration and survival, are confounded by arrhythmias, perhaps reflecting lack of transdifferentiation (19). These obstacles underscore the need to seek cardiac progenitor cells beyond the few known sources.

Materials and Methods

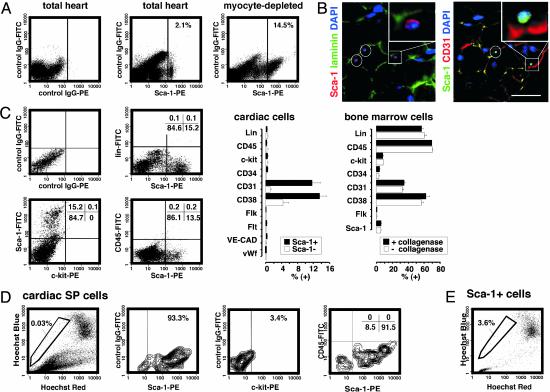

Flow Cytometry and Magnetic Enrichment. A “total” cardiac population was isolated from 6- to 12-wk-old C57BL/6 mice by coronary perfusion with 0.025% collagenase, as for viable adult mouse cardiomyocytes (20). More typically, a “myocyte-depleted” population was prepared, incubating minced myocardium in 0.1% collagenase (30 min, 37°C), lethal to most adult mouse cardiomyocytes (20). Cells were then filtered through 70-μm mesh. Bone marrow cells (21) were compared, with or without collagenase and filtration. Cells were labeled with stem cell antigen 1 (Sca-1)-phycoerythrin (PE), Sca-1-FITC, c-kit-PE; CD4-, CD8-, B220-, Gr-1-, Mac-1-, TER-119-, CD45-, CD31-, CD38-, and Flk-1-FITC; vascular endothelial-cadherin-biotin; von Willebrand factor-biotin (all Pharmingen); and Flt-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). CD45-PE (Pharmingen) was used for bone marrow cells. Biotinylated antibodies were detected with streptavidin-PE or streptavidin-FITC, Flt-1 with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma), and nonviable cells with propidium iodide. Flow cytometry was performed with an EPICS XL-MCL (Beckman Coulter) except as noted. Gates were established by nonspecific Ig binding in each experiment.

Cells labeled with Sca-1-biotin (Pharmingen) were incubated with antibiotin microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) and purified by five to six cycles of magnetic selection (22). Sorted populations were reanalyzed by flow cytometry, and the purity of Sca-1+ cells was confirmed before use.

Gene Expression. RT-PCR primers are available on request. Samples were treated with DNase and assayed in the log-linear range. For expression profiling, RNA was isolated from 5,000 Sca-1+ cells and 5,000 adult cardiomyocytes (Alliance for Cell Signaling, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center) by using the TriPure Isolation Kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis) and underwent two rounds of amplification. Expression profiling was performed by using Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) MG U74Av2 arrays, an Agilent (Palo Alto, CA) GeneArray Scanner, Affymetrix microarray suite, Ver. 5.0, and dchip 1.2 (W. Wong, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA).

Cell Culture. Newly isolated cardiac Sca-1+ cells were grown in 35-mm dishes coated with 200 μg/ml fibronectin (Sigma) by using Medium-199/10% FBS, for 3 d (5% CO2, 37°C). To induce differentiation, cells were cultured in medium containing 2% FBS and 3 μM 5-azacytidine (5-aza; 3 d) (1) or 1% DMSO (1 wk) (23). Cells were photographed by using Zeiss Axioplan 2.

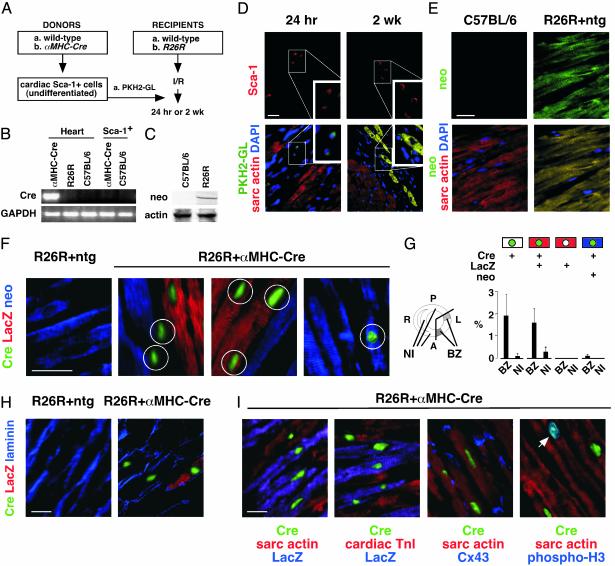

Myocardial Infarction and Cell Delivery. Cell grafting was performed with PKH2-GL dye-labeled cells (24) or a Cre/Lox [α-myosin heavy chain (MHC)-Cre/Rosa26 Cre reporter (R26R)] donor/recipient pair (25, 26). The R26R reporter line, bearing Cre-dependent LacZ behind a loxP-flanked neomycin phosphotransferase (neo) stop signal, is transcribed ubiquitously without mosaicism (26), and αMHC-Cre mediates efficient recombination at this locus even in early myocardium (25). Ischemia/reperfusion injury was performed in chronically instrumented closed-chest R26R mice with an implantable occluder (27). Four to 5 d after instrumentation, the left anterior descending coronary artery was occluded for 1 h and reperfused for 6 h. Newly isolated Sca-1+ cells (106) from αMHC-Cre mice or wild-type littermates were then injected in 100 μl of PBS via the right jugular vein. Mice were killed 2 wk later, with comparable survival (62%) in each group.

Histology and Western Blot. Alexa Fluors for antibody conjugation were from Molecular Probes. To localize Sca-1 plus laminin, Alexa Fluor 495-mouse anti-Sca-1 (Pharmingen) was used with rabbit antilaminin (Sigma) then with FITC-goat anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma). To localize Sca-1 plus CD31, Alexa Fluor 495-mouse anti-CD31 (Pharmingen) was used with FITC-Sca-1. To test homing (dye-labeled cells 24 h after i.v. delivery) and stable engraftment to the heart (dye-labeled cells at 2 wk), >120,000 cells were sampled for each condition. Expression of R26R without recombination was assessed by using rabbit antibody to neo (NPTII; Agdia, Elkhart, IN). To detect LacZ activation by Cre+ donor cells, myocytes were stained by using mouse anti-β-galactosidase (Sigma) then Texas red-goat anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes), and with FITC-mouse antisarcomeric α-actin (Sigma) or rabbit antilaminin (Sigma) then FITC-goat anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma). To elucidate the prevalence of fusion more precisely, myocardium was triply stained for Cre, neo, and LacZ by using Alexa Fluor 488-mouse anti-Cre (Babco, Richmond, CA); rabbit antibody to neo or laminin, and Alexa Fluor 647-goat anti-rabbit IgG; and Alexa Fluor 594- or 647-mouse anti-β-galactosidase (Fig. 4 F, H, and I). Mouse antibodies to sarcomeric α-actin and cardiac troponin I were conjugated with Alexa Fluor 594 and mouse anticonnexin-43 (Sigma) with Alexa Fluor 647. Mitotic phosphorylation of histone H3 was detected by using rabbit antibody to the serine-10 phosphoepitope (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) then Alexa Fluor 647-goat anti-rabbit IgG. Irrelevant mouse and rabbit antibodies conjugated with each fluor were the negative controls. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Immunostaining was visualized by confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM 510). Western blotting for neo was performed by using antibody to neo vs. total actin and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Fig. 4.

Homing, differentiation, and fusion of donor cardiac Sca-1+ cells in host myocardium. Diagram of the dye-labeling (A) and Cre/Lox (B) donor/recipient strategies. (B) RT-PCR analysis showing lack of Cre expression in newly isolated cardiac Sca-1+ cells from αMHC-Cre mice. (C) Western blot showing expression of neo in R26R mice. (D) Homing of dye-labeled cardiac Sca-1+ cells at 24 h (Left) and engraftment at 2 wk (Right). (E) Neo (FITC; yellow in merged image) was ubiquitously expressed in R26R adult ventricular myocardium. (D and E) Identical fields are shown, Upper and Lower. Cardiomyocytes were identified by sarcomeric α-actin (Texas red) and nuclei with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. (F–I) Animals were analyzed by confocal microscopy 2 wk after ischemia-reperfusion injury and infusion of ScaI+ cells. (F) Neo (blue) was ubiquitously expressed in adult ventricular myocardium of R26R mice. Grafted Sca-1+ cells from αMHC-Cre mice activate cardiomyocyte-specific Cre, and recombination of R26R. Cre protein (green) was localized to nuclei. Three phenotypes resulted. Unfused donor-derived cells express neither neo nor LacZ (circled in column 2). Fusion with host R26R myocardium typically results in LacZ+ muscle cells (red; circled in column 3). Fused cells without recombination were detected very rarely (circled in column 4). (G) Mean ± SE for donor-derived myocytes with (Cre+ LacZ+ neo–; Cre+ LacZ– neo+) and without (Cre+ LacZ– neo–) fusion after grafting. BZ, infarct border zone in anterolateral (A, L) myocardium; NI, noninfarcted control regions; P, posterior wall; R, right ventricle, interventricular septum. (H) Delineation of Cre+ cells by laminin. (I) All Cre+ cells coexpressed sarcomeric α-actin, cardiac troponin I, and Cx43. Mitotic phosphorylation of histone H3 2 wk after grafting was seen almost exclusively in donor-derived Cre+ myocytes. Arrow, Cre+ phospho-H3+ cardiomyocyte nuclei (blue-green in merged image). (Bar = 20 μm.) ntg, nontransgenic.

Statistical Analysis. Data (mean ± SE) were analyzed by ANOVA and Scheffé's test, by using a significance level of P < 0.05.

Results

Isolation of Sca-1+ Cells from Adult Mouse Myocardium. In adult mouse hearts, cardiomyocytes comprise 20–30% of the total population, the remainder including fibroblasts, vascular smooth muscle, and endothelium (28). We isolated a “myocyte-depleted” fraction of adult cardiac cells using collagenase under conditions lethal for most adult ventricular myocytes, then analyzed the cells by flow cytometry for stem cell markers including Sca-1 and c-kit. Approximately 14–17% of the cells expressed Sca-1 (increased 7-fold, compared with total cardiac cells; Fig. 1A). As in skeletal muscle (29), cardiac Sca-1+ cells were small interstitial cells adjacent to the basal lamina, typically coexpressing platelet–endothelial cell adhesion molecules (CD31) and in proximity with endothelial Sca-1– CD31+ cells (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Isolation of Sca-1+ cells from adult mouse myocardium. (A) Sca-1 was analyzed by flow cytometry (MoFlo, Cytomation, Ft. Collins, CO), by using IgG2a + 2b-FITC as the control. (B) Immunostaining of adult mouse myocardium for Sca-1, laminin, and CD31. Yellow-orange in the merged images denotes colocalization. Representative cells are highlighted in white and shown at higher magnification (Insets). (Bar = 15 μm.) (C) Cells were labeled with Sca-1 plus the indicated markers (EPICS XL-MCL, Beckman Coulter). Values in the bar graph denote prevalence in the myocyte-depleted population, e.g., 12% are Sca-1+CD31+. Bone marrow cells ± collagenase are shown (Right). (D) Cardiac SP cells were identified with Hoechst 33342 (MoFlo, Cytomation). Labeling with Sca-1 vs. c-kit and CD45 is shown as contour plots. (E) Enrichment for SP cells in the cardiac Sca-1+ population.

Cardiac Sca-1+ cells lacked blood cell lineage markers (CD4, CD8, B220, Gr-1, Mac-1, and TER119), c-kit, Flt-1, Flk-1, vascular endothelial-cadherin, von Willebrand factor, and hematopoietic stem cell markers CD45 and -34 (Fig. 1C). These features argue against a hematopoietic progenitor cell, endothelial progenitor cell, or mature endothelial phenotype. Levels of markers in bone marrow cells were not diminished by collagenase (Fig. 1C Right), excluding spurious effects of enzymatic digestion. Most cardiac Sca-1+ cells express CD31 or its receptor CD38, implicated in cell–cell binding (Fig. 1 B and C). Conversely, only 1 in 150,000 peripheral blood cells had this phenotype (Sca-1+, lin–, CD45–, CD31+ CD38+; not shown).

By efflux of Hoechst dye 33342, 0.03% of cardiac cells possess the properties of side population (SP) cells (Fig. 1D), which are enriched for long-term self renewal in other tissues; their prevalence even in bone marrow is only 0.05% (2, 21, 29). Cardiac SP cells are >93% Sca-1+, differ from marrow SP cells by typically lacking CD45 and c-kit (Fig. 1D), and are enriched 100-fold in the Sca-1+ population (Fig. 1E).

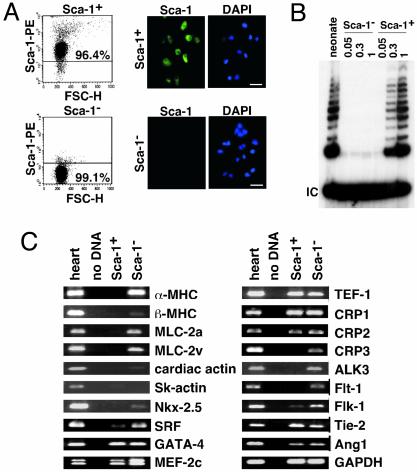

Cardiac Sca-1+ Cells Express Most Cardiogenic Transcription Factors but Not Cardiac Structural Genes. By magnetic separation, we isolated a Sca-1+ fraction (>96% pure, after five or more rounds) and Sca-1– fraction (>99% pure, even in the flow-through; Fig. 2A). Telomerase reverse transcriptase is associated with self-renewal potential, down-regulated in adult myocardium, and sufficient to prolong cardiomyocyte cycling (30). By a telomeric repeat amplification protocol (30), we detected telomerase activity only in Sca-1+ cells from adult heart but not in Sca-1– cells, at levels similar to neonatal myocardium (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Purification and culture of cardiac Sca-1+ cells. Purity of cardiac Sca-1+ and -1– cells after magnetic enrichment. (A Left) Flow cytometry. FSC-H, forward-angle light scatter. (Right) Immunostaining. (B) Telomerase activity (30) was detected in cardiac Sca-1+ cells but not Sca-1– cells. Numbers above each lane indicate the amount of adult lysate, relative to neonatal mouse heart (“neonate”). (C) RT-PCR analysis of cardiac Sca-1+ and -1– cells vs. adult mouse heart. (Bar in A = 5 μm).

By RT-PCR (Fig. 2C), Sca-1+ cells express none of the following cardiac genes: α- and βMHC, atrial and ventricular myosin light chain-2 (MLC-2a, -2v); cardiac and skeletal α-actin; and muscle LIM protein/cysteine-rich protein-3. Most were detected in Sca-1– cells, consistent with the presence of some myocytes in the starting “myocyte-depleted” fraction. Sca-1+ cells did not express Nkx2.5 and had minimal levels of SRF. However, other cardiogenic transcription factors were expressed (GATA-4, MEF-2C, and TEF-1), as in marrow stromal cells with cardiogenic potential (1). Consistent with the lack of Flt-1 and Flk-1 by flow cytometry (Fig. 1C), little or no expression was seen by RT-PCR (Fig. 2C). Sca-1– cells did express Tie-2 and angiopoietin-1 (Ang1), ostensibly vascular markers found also in marrow SP cells (2).

Microarray profiling (Table 1) was concordant with these results, extending the cardiac structural genes that are not expressed in cardiac Sca-1+ cells, and adding Bop and popeye-3 as cardiogenic transcription factors that are absent. Neither CD45, CD34, c-kit, nor Flt-1 was detected, nor the hematopoietic stem cell transcription factors Lmo2, GATA2, and Tal1/Scl. Adult cardiac Sca-1+ cells were enriched, as expected, for diverse cell cycle mediators, growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines. Sca-1+ cells also express multiple transcriptional repressors (DNA methyltransferase-1, histone deacetylase-1, the Notch effector Hes1, and Groucho-binding proteins runx1 and -2), as found in adult and embryonic stem cells (31). Absence of Oct-4 and UTF-1, by microarray profiling, was confirmed by RT-PCR.

Table 1. Expression profiling of adult cardiac Sca-1+ cells vs. cardiomyocytes.

| Transcripts detected in purified adult cardiac myocytes but not cardiac Sca-1+ cells* |

| Sarcomeric proteins: Acta1, Actc1, Mybpc3, Myhca, Myhcb, Mylc, Mylc2a, Mylpc, Myom1, Myom2, Tncc, Tnni3, Tnnt1 |

| Transcription factors: Bop, Csrp3, Nkx2-5, Pop 3 |

| Growth factors: Fgf1 |

| Metabolism: Acas2, Adss1, Art1, Ckmt2, Ckmm, Cox6a2, Cox7a1, Cox8b, Crat, Cyp4b1, Fabp3, Facl2, Mb, Pgam2, Pygm, Slc2a4 |

| Ion transport: Atp1a2, Cacna1s, Casq2, Kcnq1, Kcnj8, Ryr2 |

| Other: Cdh13, Ldb3, Nppb, Sgca, Sgog |

| Transcripts detected in cardiac Sca-1+ cells but not purified adult cardiac myocytes† |

| Growth factors, cytokines, receptors: Adm, Bmp1, Csf1, Crlf1, Fgfr1, Figf, Frzb, Fzd2, Inhba, Inhbb, Igf1, Igfbp2, Igfbp4, Il4ra, Il6, Pdgfra, Sfrp1, Scya2, Scya7, Scya9, Scyb5, Sdf1, Tgfb2, Tnfrsf6, Vegfc, Wisp1, Wisp2 |

| Transcription factors: Aebp1, Csrp, Csrp2, Dnmt1, Edr2, Foxc2, Hey1, Hdac1, Madh7, Ndn, Nmyc1, Odz3, Pias3, runx1, runx2, Tcf21, Twist, ZBP-99 |

| Cell cycle: Cdc2a, Cks1, Ccnb1-rs1, Ccnc, Ccne2, Prim2, Mki67, MCM7, Rab6kifl, Rev3l, Rrm1, Tyms, Top2a |

| Adhesion, recognition: Anxa1, Npnt, Nid2, Ptx3, Tm4sf6, Vcam1 |

| Signal transduction: Borg4, Cask, Ect2, Eif1a, Lasp1, Map3k6, Map3k8, Pscd3, Sphk1, Stk6, Stk18, Tc101, Wrch1 |

| Extracellular matrix: Adam9, Mmp3, Col1a1, Col1a2, Col3a1, Col4a5, Col5a, Col5a2, Col8a1, Lox, Spp1, Timp, Tnc |

Two hundred seventy-five transcripts were detected in adult cardiac myocytes but not adult cardiac Sca-1+ cells, of which relevant transcripts with an 8-fold or more change in signal intensity are shown. Others include 35 ESTs, 37 RIKEN cDNAs, and 11 unannotated mRNAs.

Eight hundred sixteen transcripts were detected in adult cardiac Sca-1+ cells but not adult heart, of which relevant transcripts with an 8-fold or more change in signal intensity are shown. Others include 116 ESTs, 154 RIKEN cDNAs, and 28 unannotated mRNAs.

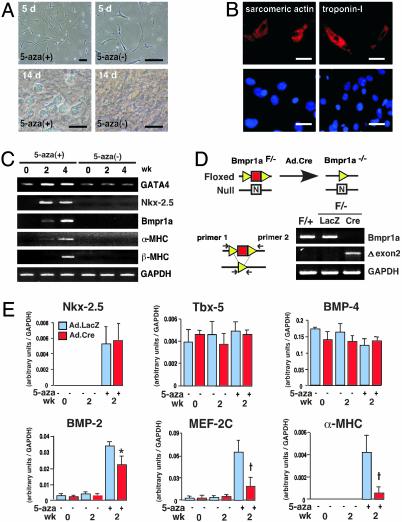

In Vitro Differentiation of Cardiac Sca-1+ Cells. The cytosine analog 5-aza can induce cardiac differentiation by marrow stromal cells (1), suggesting its possible utility here. Cells treated with 3 μM of 5-aza for 3 d, starting 3 d after plating, gradually developed multicellular spherical structures (Fig. 3A), then flattened after 2 wk. Immunostaining at 4 wk confirmed the induction of sarcomeric α-actin (4.6 ± 1.2%) and cardiac troponin-I (2.8 ± 0.9%) in treated cells (Fig. 3B) but not untreated ones (not shown). Nkx-2.5, αMHC, βMHC, and type 1A receptor for bone morphogenetic proteins (Bmpr1a) that are involved in heart development (25), were highly induced by 5-aza (Fig. 3C); all but βMHC were apparent at 2 wk. None was expressed in the absence of 5-aza or in cells treated with 1% DMSO (not shown).

Fig. 3.

In vitro differentiation of cardiac Sca-1+ cells is induced by 5-aza and depends on a BMP receptor. (A) Phase-contrast microscopy. (B) Induction of sarcomeric α-actin and cardiac troponin I by using 5-aza, shown by immunostaining (4 wk). Differentiated cells (red) are found in the monolayer with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). (C) Induction of Nkx-2.5, Bmpr1a, and cardiac MHC genes using 5-aza, shown by RT-PCR. (D) Cartoon of the floxed and null Bmpr1a alleles at exon 2. (Bottom Right) Excision of exon 2 after viral delivery of Cre, shown by PCR. (E) Cardiac Sca-1+ cells from Bmpr1aF/– mice were subjected to viral gene transfer, differentiated with 5-aza, and analyzed by quantitative real-time-PCR. White, β-gal; black, Cre. *, P < 0.05; †, P < 0.01; n = 6. [Bars = 20 μm (A) and 10 μm (B).]

Although myocyte-restricted deletion of Bmpr1a disrupts cardiac organogenesis, lethality at gastrulation in homozygous-null mice obscures the gene's role in cardiac specification (25), and differing mechanisms mediate cardiac fate, depending on the progenitors examined (4, 23). Therefore, Sca-1+ cells from Bmpr1aF/– hearts (containing one loxP-flanked and one null allele) were exposed to adenovirus encoding LacZ vs. Cre (Fig. 3D). Disruption of Bmpr1a by Cre was confirmed by PCR (Fig. 3D) and differentiation was compared by using quantitative real-time PCR (Fig. 3E). Neither Tbx5 nor BMP-4 required 5-aza for expression, and their expression was unchanged in the absence of Bmpr1a. By contrast, deletion of Bmpr1a significantly impaired the induction of BMP-2, MEF-2C, and, especially, α-MHC. Of the genes investigated, only Nkx-2.5 was induced by 5-aza yet unaffected by disruption of Bmpr1a.

A Cre/Lox Donor/Reporter System Demonstrates Homing, Differentiation, and Fusion of Cardiac Sca-1+ Cells in Injured Myocardium. In proof-of-concept studies to explore the feasibility of homing and stable engraftment to the heart, we labeled cardiac Sca-1+ cells with the membrane dye PKH2-GL and injected cells i.v. after ischemia/reperfusion injury (Fig. 4 A and D). Donor cells were detected in myocardium within 24 h by epifluorescence microscopy (mean, 0.8 ± 0.05% of total left ventricular cells) but were absent from the infarct itself; uninfarcted regions, lung, liver, kidney, and control mice received Sca-1+ cells without infarction. As with marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (32, 33), cardiac Sca-1+ cells were also detected in the spleen (not shown). Persistence of the grafted cells in myocardium at 2 wk (“engraftment”) was confirmed in 10 of 14 mice (5.1 ± 1.1%, suggesting proliferation in the interim) and induction of sarcomeric α-actin confirmed in >60% of dye-labeled cells. Donor-derived sarcomeric actin-positive cells were abundant in the infarct border zone (18.1 ± 4.4%) but there were 200-fold fewer after injecting Sca-1– cells (0.08 ± 0.002%).

Next, we used a Cre/Lox donor/recipient pair as a more conclusive genetic tag of cell identity and a means to test the issue of cell fusion (Fig. 4 A–C and E–I). Here, differentiation of donor cells is reflected by induction of αMHC-Cre and fusion between donor and host cells by activation of LacZ. αMHC is a late but stringent criterion of cardiac differentiation, and no promiscuous expression is seen with αMHC-Cre (25, 34). Newly isolated cardiac ScaI+ cells from αMHC-Cre mice do not express Cre (Fig. 4B), as anticipated from their lack of endogenous αMHC (Figs. 2C and 3C). To monitor R26R expression in adult hearts, we first stained for neo, which provides the LoxP-flanked “stop” signal upstream from LacZ and should be present in all R26R cells lacking Cre. R26R mice express neo by Western blotting, wild-type C57BL/6 mice do not express neo, and R26R mice stain homogenously for neo throughout myocardium even in the infarct border zone (Fig. 4 C and E).

Two weeks after injury and infusion of undifferentiated αMHC-Cre Sca-1+ cells, nuclear-localized Cre protein was detected specifically in the infarct border zone (Fig. 4 F–I). The prevalence of Cre+ nuclei in the left ventricle was ≈3% (n = 3; 75,000 sampled), engraftment 150-fold greater than reported for endogenous marrow-derived SP cells (35). Cre+ cells were localized almost exclusively to anterolateral myocardium, and the region was subjected to infarction (Fig. 4G). Coexpression of Cre and LacZ was readily apparent in half the Cre+ cells, as evidence of chimerism (Fig. 4G). Injection of nontransgenic cardiac Sca-1+ cells lacking αMHC-Cre did not produce Cre protein or activate LacZ (Fig. 4F Left). By immunostaining for LacZ plus sarcomeric α-actin or laminin, LacZ activation was confined to myocytes (Fig. 4 F and H, and data not shown).

We do not know whether fusion precedes differentiation or vice versa. However, roughly half the cells expressing αMHC-Cre did not express LacZ (Fig. 4 F–I). These Cre+LacZ– cells could indicate differentiation autonomous of fusion (bona fide cardiopoiesis) or, alternatively, fused cells with incomplete penetrance for recombination. By triple staining for neo plus LacZ and Cre, fused cells without recombination were identifiable sporadically but minute in prevalence and did not contribute significantly to the Cre+ population (Fig. 4F Right). Regardless of the presence or absence of fusion, all donor-derived differentiated (Cre+) cells expressed sarcomeric α-actin, cardiac troponin I, and connexin-43 (Fig. 4I).

Assayed 2 wk after cell grafting, 5% of Cre+ sarcomeric actin+ cells (41/816) stained for the serine-10 phosphorylation of histone H3, a marker of mitotic Cdc2 activity (30), vs. only 0.00004% of Cre– cardiomyocytes (1/24,000; Fig. 4I).

Discussion

The inexorability of heart failure has prompted studies of interventions to supplant cardiac muscle cell number. A foundation for such efforts is to know what cells can be coaxed into a cardiac fate and how this transition is governed. By using cardiac-specific Cre to denote donor cell identity and differentiation in situ, we provide genetic evidence that cardiac muscle progenitors can be isolated from the adult heart. However, the frequent occurrence of LacZ+ chimeric cells, in vivo in the absence of selection pressure, provides a further cautionary note in the interpretation of adult cell plasticity (15, 16). Cell fusion is typical of skeletal muscle myoblasts forming myotubes, but binucleation in postnatal ventricular myocytes occurs by uncoupling karyokinesis from cytokinesis. Cardiac cell fusion does not occur ordinarily, and diffusion through gap junctions does not occur for molecules the size of Cre or LacZ protein.

Distinct from hematopoietic stem cells (based on CD45, CD34, c-kit, Lmo2, GATA2, and Tal1/Scl) and endothelial progenitor cells (based on CD45, CD34, Flk-1, and Flt-1), cardiogenic Sca-1+ cells perhaps best resemble the highly myogenic cells in skeletal muscle that are Sca-1+ but CD45–, CD34–, and c-kit– (22); these differ from muscle “satellite” cells (Sca-1–, CD34+) (11), muscle-derived hematopoietic stem cells (CD45+) (22), and multipotential muscle cells (Sca-1+, CD34+) (36). Conceptually, the presence of Tie-2, Ang-1, and CD31 in the absence of all of the markers above might denote a primitive hemangioblast or its precursor. Surface labeling like that of cardiac Sca-1+ cells also was reported for multipotent adult progenitor cells from bone marrow, but these home to normal liver and lung, lack mesoderm transcription factors, and express minimal Sca-1 (33). Our data concur with the finding of SP cells in adult mouse myocardium that lack CD45 and hematopoietic potential (37). In vitro, cardiac myogenesis by heart-derived Sca-1+ cells depends at least in part on Bmpr1a, which may signify a useful pathway to promote their differentiation into cardiac muscle in vivo.

Because we used αMHC-Cre expression as the definitive marker of donor cell identity, we confine our analysis here to donor-derived cardiomyocytes. Alternative lineage markers, clonal studies, and other methods will be needed to pinpoint the cells' fates and origin. If progenitor cells are assumed conservatively to be just a small proportion of the Sca-1+ cells, even minute subpopulations like SP cells could be essential to the phenotype observed. Knowledge of the cells' source and migration during development could also be instrumental to resolving a seeming paradox: although isolated from the heart, exogenous cardiac Sca-1+ cells are not recruited there in the absence of injury.

Adult ventricular myocytes are refractory to cell cycle reentry for reasons that include their lack of telomerase activity (30). Cardiac Sca-1+ cells offer auspicious properties for cardiac repair, including high levels of telomerase, homing to injured myocardium, and dependence on the well defined BMP pathway. We emphasize the incompleteness of myocardial repair as executed by all endogenous mechanisms collectively, including whatever progenitors exist intrinsic and extrinsic to the heart. Although endogenous Sca-1+ cells are present in the heart, engrafted ones accounted for virtually all of the cycling myocytes 14 d after infarction. Thus, there exists both need and opportunity to augment cardiac Sca-1+ cell number or function.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Goodell, R. Schwartz, D. Chang, M. Majesky, and K. Hirschi for suggestions, and M. Mancini and the Baylor Integrated Microscopy Core for confocal microscopy. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants (to M.D.S. and M.L.E.) and the M. D. Anderson Foundation Professorship (to M.D.S.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: Bmpr1a, type IA receptor for bone morphogenetic proteins; MHC, myosin heavy chain; neo, neomycin phosphotransferase; R26R, Rosa26 Cre reporter; Sca-1, stem cell antigen 1; SP, side population; 5-aza, 5-azacytidine.

References

- 1.Makino, S., Fukuda, K., Miyoshi, S., Konishi, F., Kodama, H., Pan, J., Sano, M., Takahashi, T., Hori, S., Abe, H., et al. (1999) J. Clin. Invest. 103, 697–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson, K. A., Majka, S. M., Wang, H., Pocius, J., Hartley, C. J., Majesky, M. W., Entman, M. L., Michael, L. H., Hirschi, K. K. & Goodell, M. A. (2001) J. Clin. Invest. 107, 1395–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orlic, D., Kajstura, J., Chimenti, S., Jakoniuk, I., Anderson, S. M., Li, B., Pickel, J., McKay, R., Nadal-Ginard, B., Bodine, D. M., et al. (2001) Nature 410, 701–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Condorelli, G., Borello, U., De Angelis, L., Latronico, M., Sirabella, D., Coletta, M., Galli, R., Balconi, G., Follenzi, A., Frati, G., et al. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 10733–10738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badorff, C., Brandes, R. P., Popp, R., Rupp, S., Urbich, C., Aicher, A., Fleming, I., Busse, R., Zeiher, A. M. & Dimmeler, S. (2003) Circulation 107, 1024–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beltrami, A. P., Urbanek, K., Kajstura, J., Yan, S. M., Finato, N., Bussani, R., Nadal-Ginard, B., Silvestri, F., Leri, A., Beltrami, C. A., et al. (2001) N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 1750–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castro, R. F., Jackson, K. A., Goodell, M. A., Robertson, C. S., Liu, H. & Shine, H. D. (2002) Science 297, 1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagers, A. J., Sherwood, R. I., Christensen, J. L. & Weissman, I. L. (2002) Science 297, 2256–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson, D. J., Gage, F. H. & Weissman, I. L. (2001) Nat. Med. 7, 393–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blau, H. M., Brazelton, T. R. & Weimann, J. M. (2001) Cell 105, 829–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seale, P., Asakura, A. & Rudnicki, M. A. (2001) Dev. Cell 1, 333–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamihata, H., Matsubara, H., Nishiue, T., Fujiyama, S., Tsutsumi, Y., Ozono, R., Masaki, H., Mori, Y., Iba, O., Tateishi, E., et al. (2001) Circulation 104, 1046–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orlic, D., Kajstura, J., Chimenti, S., Limana, F., Jakoniuk, I., Quaini, F., Nadal-Ginard, B., Bodine, D. M., Leri, A. & Anversa, P. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 10344–10349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glaser, R., Lu, M. M., Narula, N. & Epstein, J. A. (2002) Circulation 106, 17–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vassilopoulos, G., Wang, P. R. & Russell, D. W. (2003) Nature 422, 901–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang, X., Willenbring, H., Akkari, Y., Torimaru, Y., Foster, M., Al-Dhalimy, M., Lagasse, E., Finegold, M., Olson, S. & Grompe, M. (2003) Nature 422, 897–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strauer, B. E., Brehm, M., Zeus, T., Kostering, M., Hernandez, A., Sorg, R. V., Kogler, G. & Wernet, P. (2002) Circulation 106, 1913–1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Assmus, B., Schachinger, V., Teupe, C., Britten, M., Lehmann, R., Dobert, N., Grunwald, F., Aicher, A., Urbich, C., Martin, H., et al. (2002) Circulation 106, 3009–3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menasché, P., Hagege, A. A., Vilquin, J.-T., Desnos, M., Abergel, E., Pouzet, B., Bel, A., Saratenau, S., Scorsin, M., Schwartz, K., et al. (2003) J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 41, 1078–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou, Y. Y., Wang, S. Q., Zhu, W. Z., Chruscinski, A., Kobilka, B. K., Ziman, B., Wang, S., Lakatta, E. G., Cheng, H. & Xiao, R. P. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. 279, H429–H436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodell, M. A., Brose, K., Paradis, G., Conner, A. S. & Mulligan, R. C. (1996) J. Exp. Med. 183, 1797–1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKinney-Freeman, S. L., Jackson, K. A., Camargo, F. D., Ferrari, G., Mavilio, F. & Goodell, M. A. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 1341–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monzen, K., Shiojima, I., Hiroi, Y., Kudoh, S., Oka, T., Takimoto, E., Hayashi, D., Hosoda, T., Habara-Ohkubo, A., Nakaoka, T., et al. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 7096–7105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murohara, T., Ikeda, H., Duan, J., Shintani, S., Sasaki, K., Eguchi, H., Onitsuka, I., Matsui, K. & Imaizumi, T. (2000) J. Clin. Invest. 105, 1527–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaussin, V., Van De Putte, T., Mishina, Y., Hanks, M. C., Zwijsen, A., Huylebroeck, D., Behringer, R. R. & Schneider, M. D. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 2878–2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soriano, P. (1999) Nat. Genet. 21, 70–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nossuli, T. O., Lakshminarayanan, V., Baumgarten, G., Taffet, G. E., Ballantyne, C. M., Michael, L. H. & Entman, M. L. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. 278, H1049–H1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soonpaa, M. H., Kim, K. K., Pajak, L., Franklin, M. & Field, L. J. (1996) Am. J. Physiol. 271, H2183–H2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asakura, A., Seale, P., Girgis-Gabardo, A. & Rudnicki, M. A. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 159, 123–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oh, H., Taffet, G. E., Youker, K. A., Entman, M. L., Overbeek, P. A., Michael, L. H. & Schneider, M. D. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 10308–10313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramalho-Santos, M., Yoon, S. J., Matsuzaki, Y., Mulligan, R. C. & Melton, D. A. (2002) Science 298, 597–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toma, C., Pittenger, M. F., Cahill, K. S., Byrne, B. J. & Kessler, P. D. (2002) Circulation 105, 93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang, Y., Jahagirdar, B. N., Reinhardt, R. L., Schwartz, R. E., Keene, C. D., Ortiz-Gonzalez, X. R., Reyes, M., Lenvik, T., Lund, T., Blackstad, M., et al. (2002) Nature 418, 41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agah, R., Frenkel, P. A., French, B. A., Michael, L. H., Overbeek, P. A. & Schneider, M. D. (1997) J. Clin. Invest. 100, 169–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jackson, K. A., Mi, T. & Goodell, M. A. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 14482–14486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torrente, Y., Tremblay, J. P., Pisati, F., Belicchi, M., Rossi, B., Sironi, M., Fortunato, F., El Fahime, M., D'Angelo, M. G., Caron, N. J., et al. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 152, 335–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asakura, A. & Rudnicki, M. A. (2002) Exp. Hematol. 30, 1339–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]