Abstract

Long-term potentiation (LTP) is the most prominent model for the molecular and cellular mechanisms of learning and memory. Two main forms of LTP have been distinguished. The N-methyl-d-aspartate-receptor-dependent forms of LTP have been studied most extensively, whereas much less is known about N-methyl-d-aspartate-receptor-independent forms of LTP. This latter type of LTP was first described at the mossy fiber synapses in the hippocampus and subsequently at parallel fiber synapses in the cerebellum as well as at corticothalamic synapses. These presynaptic forms of LTP require a rise in the intraterminal calcium concentration, but the channel through which calcium passes has not been identified. By using pharmacological tools as well as genetic deletion, we demonstrate here that α1E-containing voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCCs) shift the threshold for mossy fiber LTP. The channel is not involved in the expression mechanism, but it contributes to the calcium influx during the induction phase. Indeed, optical recordings directly show the presence and the function of α1E-containing VDCCs at mossy fiber terminals. Hence, a previously undescribed role for α1E-containing VDCCs is suggested by these results.

Repetitive activation of glutamatergic synapses initiates long-lasting changes in synaptic strength. Long-term potentiation (LTP) at the Schaffer collaterals in the CA1 area of the hippocampus is the most studied form of synaptic plasticity and requires the activation of postsynaptic N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) and a rise in postsynaptic calcium (1, 2). In contrast, hippocampal mossy fiber synapses exhibit a form of LTP that is entirely independent of NMDAR activation (3, 4). This has been demonstrated pharmacologically (3, 4) as well as with genetic deletion techniques (5). In addition, mossy fiber LTP can be induced in the presence of ionotropic (refs. 6–9, but see also 10) and metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonists (Refs. 11 and 12, but see also 13), leading to a model in which the induction of mossy fiber LTP depends on a tetanus-induced rise in presynaptic calcium (14). In line with this model, a tetanus in the absence of extracellular calcium fails to induce LTP (9). Once calcium has entered the presynaptic terminal, a calcium–calmodulin complex activates the calcium/calmodulin-sensitive adenylyl cyclase I, which is highly enriched in mossy fiber synapses (15). The activation of adenylyl cylcase I will cause a transient elevation in cAMP (16, 17), which then causes an activation of protein kinase A (15, 18).

Remarkably, none of the blockers for P/Q-(α1A)-, N-(α1B)and L-(α1C/D)-type voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCCs) blocks the induction of mossy fiber LTP, nor are these channels up-regulated after LTP induction (9). The mRNA for α1E subunits, a good candidate for some of the native R-type VDCCs (19), is highly expressed in dentate gyrus granule cells (20–22). Furthermore, the α1E protein has been found at mossy fiber synapses by using a specific antibody for α1E (22).

We therefore tested whether α1E-containing VDCCs are involved in synaptic transmission and plasticity at the mossy fiber synapse. By using pharmacological tools and genetic deletion models (23), we indeed found that the threshold for inducing LTP depends on the activation of α1E-containing VDCCs.

Materials and Methods

Preparation. Hippocampal slices were prepared from Wistar rats and α1E-deficient and wild-type mice (postnatal > 20 d) as described (24, 25). In brief, the animals were anesthetized with halothane and decapitated, and the brains were removed. Tissue blocks containing the subicular area and hippocampus were mounted on a microslicer (DTK-10.0, Dosaka, Kyoto) in a chamber filled with ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mM) NaCl, 50; sucrose, 150; NaHCO3, 25; KCl, 2.5; NaH2PO4, 1; CaCl2, 0.5; MgSO4, 7; glucose, 10; and saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2, pH 7.4. Transverse slices were cut at 300- to 500-μm thickness and heated to 35°C for 30 min. Slices were then cooled to room temperature and transferred to ACSF containing (in mM) NaCl, 119; NaHCO3, 26; glucose, 10; KCl, 2.5; CaCl2, 2.5; MgSO4, 1.3; and NaH2PO4, 1. In experiments with nickel, phosphates were omitted, and MgSO4 was substituted by MgCl2. Chemicals were obtained from Sigma. All ACSF was equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The slices were stored in a submerged chamber where they were held for 1–7 h before being transferred to the recording chamber, where they were perfused with ACSF at a rate of 3–4 ml/min.

Electrophysiology. Field potential recordings were performed with patch pipettes filled with Hepes-buffered external solution placed in stratum lucidum. Low-resistance patch pipettes were placed in the granule cell layer or in the hilus region to stimulate mossy fibers. The frequency of stimulation was 0.05 Hz. Tetanic stimulation was 25 Hz with different pulse numbers. One of the group 2 metabotropic glutamate receptor agonists (2S,2′R,3′R)-2-(2′,3′-dicarboxycyclopropyl)glycine (DCG-IV) (1–2 μM) or (2S,1′S,2′S)-2-(carboxycyclopropyl)-glycine (L-CCG-I) (10 μM) was applied at the end of each experiment to verify that the signal was generated by mossy fiber synapses (26). Because of the large posttetanic potentiation at mossy fiber synapses, the initial one to three data points following the tetanus are off the displayed scale in some of the figures. Average values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Drugs used were 2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoylbenzo[f]quinoxaline, D(-)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid, DCG-IV, L-CCG-I, NiCl2, and CdCl2, which were obtained from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, U.K.). ω-AgaTx IVA, ω-CgTx GVIA, and SNX-482 were obtained from Peptides International or Bachem Biochemica. Cytochrome c (0.1 mg/ml) and BSA (0.1%) were added to solutions containing toxins.

Fluorescence Measurements. Mossy fibers consisting of granule cell axons were locally labeled with a pressure stream of the low-affinity calcium indicator magnesium green AM (Molecular Probes). Recordings were started 3–7 h after slices were labeled. Mossy fibers were stimulated extracellularly, and epifluorescence was measured with a single photodiode from a spot a few hundred μm away from the loading site. The signals from the photodiode were digitized by data acquisition hardware (PCI-6036E National Instruments, Austin, TX) at 5 kHz and captured with IGOR PRO software (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). The change in fluorescence intensity (ΔF) relative to the initial baseline of fluorescence (F) was calculated (ΔF/F).

Results

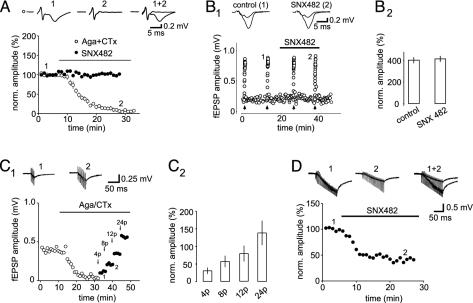

Effects of VDCC Blockers on Mossy Fiber Transmission. We initially tested the effects of different VDCC blockers on synaptic transmission at mossy fiber synapses. In agreement with a previous publication (9), the P/Q-type VDCC blocker ω-AgaTx IVA depressed mossy fiber synaptic transmision almost completetly by 95 ± 1% (n = 6), whereas the N-type VDCC blocker ω-CgTx GVIA reduced the field excitatory postsynaptic potentials by 45 ± 4% (n = 8). Combined application of both blockers completely blocked synaptic transmission at mossy fiber synapses (n = 8; Fig. 1 A and C).

Fig. 1.

α1E-Containing VDCCs do not participate in basal synaptic transmission but can contribute to release upon repetitive activation. (A) Combined application of ω-AgaTx IVA and ω-CgTx GVIA (1 μM) completely blocked synaptic transmission from mossy fibers. In contrast, addition of SNX-482 (500 nM) had no effect on basal synaptic transmission. Traces were taken from a representative experiment at time points indicated in the graph. (B1) F induced by switching the stimulation frequency from 0.05 to 1 Hz (arrows) is also unaffected by SNX-482, as shown in the example experiment and in the summary bar diagram (B2). Note that baseline synaptic transmission was not affected by SNX-482. (C1) Combined and continuous application of ω-AgaTx IVA (1 μM) and ω-CgTx GVIA (1 μM) completely blocked synaptic transmission. However, increasing the number of stimuli to 4, 8, 12, and 24 pulses (at 25 Hz, arrows) could restore synaptic transmission. (C2) Summary plot for five experiments is shown. Values are normalized to the field excitatory postsynaptic potential (fEPSP) amplitude upon single shock stimulation. (D) In the presence of ω-AgaTx IVA and ω-CgTx GVIA, the restored synaptic transmission was substantially reduced by SNX-482 (500 nM). Stimulation artifacts were truncated.

The mRNA for α1E is highly abundant in dentate gyrus granule cells (20–22), and a recent report suggested that “R-type VDCCs” contribute to excitatory synaptic transmission in the hippocampus (27). The toxin SNX-482, isolated from tarantula Histerocrates gigas venom, is a very potent and highly specific blocker for α1E-containing VDCCs (28). Different concentrations of this antagonist (200, 500, and 1,000 nM), however, had no effect on basal synaptic transmission. Fig. 1 A shows an averaged time course for several such experiments using 500 nM SNX-482 (n = 7). We also tested the effect of the antagonist on frequency facilitation (FF) and paired pulse facilitation (PPF), phenomena particularly pronounced at mossy fiber synapses. There were no detectable effects of SNX-482 on both forms of short-term plasticity (PPF of 260 ± 40% versus 260 ± 30% in control and SNX-482, respectively; Fig. 1 B1 and B2 for FF).

Interestingly, when mossy fiber transmission was completely blocked by the combined and continuous application of saturating concentrations of ω-AgaTx IVA (1 μM) and ω-CgTx GVIA (1 μM), repetitive stimulation with an unchanged stimulus strength restored transmission (Fig. 1C). The same result was obtained with high concentrations of ω-ConusTx-MVIIC (3 μM), which is a highly potent, but nonspecific, antagonist for P/Q- and N-type VDCCs (n = 3). The restored potentials were blocked by Cd2+ (n = 5) and also by 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (n = 3), demonstrating a role of VDCCs and glutamate receptors in their generation. Furthermore, the remaining potentials were partially inhibited by SNX-482 (54.1 ± 2.7%, n = 7; Fig. 1D), suggesting the involvement of α1E-containing VDCCs. Thus, the results so far suggest that α1E-containing VDCCs do not contribute to basal synaptic transmission; however, they can cause release of glutamate from mossy fiber synapses when repetitively activated.

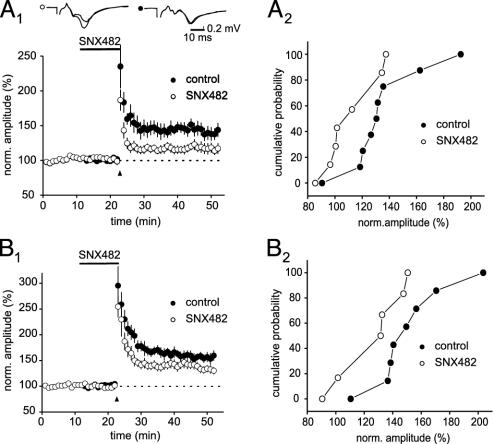

α1E-Containing VDCCs Control the Induction of Mossy Fiber LTP. Mossy fiber synaptic transmission is exquisitely sensitive to repetitive stimulation. We found that only 12 stimuli at 25 Hz already caused a clear long-lasting enhancement of synaptic strength (140 ± 9%, n = 8; Fig. 2A). Application of the α1E-containing VDCC blocker SNX-482, however, antagonized LTP under these conditions (116 ± 7% of control, P < 0.05, n = 7; Fig. 2 A). Increasing the stimulus number to 25 pulses within the train increased the magnitude of LTP to 156 ± 9% (n = 7). SNX-482 also significantly inhibited this stronger LTP, but it was less effective than with lower stimulus numbers (132 ± 7%, P < 0.05, n = 6; Fig. 2B). Further increasing the stimulus numbers within a train to 50 or 125 pulses at 25 Hz led to slightly more LTP than with 25 pulses (170 ± 10%, n = 5 and 190 ± 15%, n = 8). Following these strong tetani, mossy fiber LTP was no longer dependent on α1E-containing VDCCs. LTP was not significantly different in the presence or absence of SNX-482 (175 ± 20%, n = 4 for 50 pulses and 198 ± 19% for 125 pulses, respectively; n = 6).

Fig. 2.

Block of α1E-containing VDCCs reduces LTP induced by weak tetanic stimulation. LTP elicited with 12 pulses at 25 Hz is strongly reduced by SNX-482. The drug was applied for 12 min (10 min before and 2 min after the tetanus) and then washed out. Example traces are shown above from representative experiments; stimulation artifacts are truncated (A1). (B1) LTP induced by an increased stimulus number of 25 pulses is still significantly reduced by SNX-482. In A2 and B2, the data are graphically summarized with cumulative probability plots.

Nickel is thought to be a very potent antagonist of α1E-containing (20) and T-type VDCCs. α1E-Containing VDCCs have recently been found in dentate gyrus granule neurons, in which the so-called R-type VDCCs were highly sensitive to nickel (29); therefore, we also tested the effects of nickel on mossy fiber synaptic transmission. In line with the data obtained with SNX-482, we could not find any effect of nickel (tested up to 200 μM) on basal synaptic transmission (Figs. 3 and 4) or on PPF (240 ± 10% to 250 ± 10%) or FF (630 ± 30% versus 600 ± 25%) (n = 5 each). Next, we repeated the experiments, in which we repetitively stimulated mossy fiber synapses in the presence of ω-AgaTx IVA (1 μM) and ω-CgTx GVIA (1 μM). As expected, nickel also reduced the restored potentials (43.4 ± 8%, n = 5). Most important, nickel blocked mossy fiber LTP when induced with low stimulus numbers (114 ± 8% of control, P < 0.05, n = 6; Fig. 3A). In turn, LTP could be restored in the presence of nickel when using strong tetani (210 ± 30%, n = 5; Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Nickel reduces mossy fiber LTP induced by weak, but not by strong, stimuli. Application of 100 μM nickel reduced mossy fiber LTP when induced with a weak tetanus. Summary data for n = 6 (nickel) and n = 8 (control) experiments are depicted in the graph in A. The example traces are taken at the time points indicated by the numbers. (B) Strong tetanic stimulation (125 pulses) elicited LTP, which was not antagonized by the block of α1E-containing VDCCs with 100 μM nickel. The graph summarizes n = 5 (nickel) and n = 8 (control) experiments.

Fig. 4.

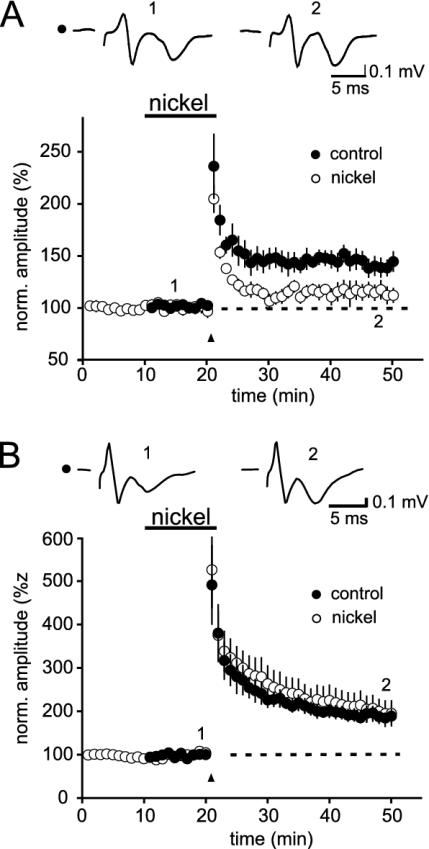

α1E-Containing VDCCs are not involved in the expression of mossy fiber LTP. (A) Mossy fiber LTP was induced by a tetanic stimulation. Once LTP had stabilized, nickel was applied. Note that there was no effect of nickel on the already established LTP. (B) Application of 50 μM forskolin for 10 min caused a strong enhancement of synaptic transmission. However, the forskolin-induced increase was not affected by nickel or SNX-482 (B2). Note that nickel had no effect on baseline transmission (B1).

To elucidate whether α1E-containing VDCCs are involved in the induction or the expression of mossy fiber LTP, we conducted two types of experiments. First, we induced mossy fiber LTP. Once LTP became stable, we antagonized α1E-containing VDCCs (Fig. 4A). No effect on already established LTP could be seen following the application of nickel. Second, we directly activated adenylyl cyclase by using forskolin. Brief application of 50 μM forskolin caused a strong enhancement in synaptic transmission (Fig. 4 B1 and B2). However, neither nickel nor SNX-482 had any effect on the forskolin-induced enhancement (Fig. 4 B1 and B2). Therefore, two lines of evidence pointed to an involvement of α1E-containing VDCCs in the induction, rather than the expression mechanism, of mossy fiber LTP.

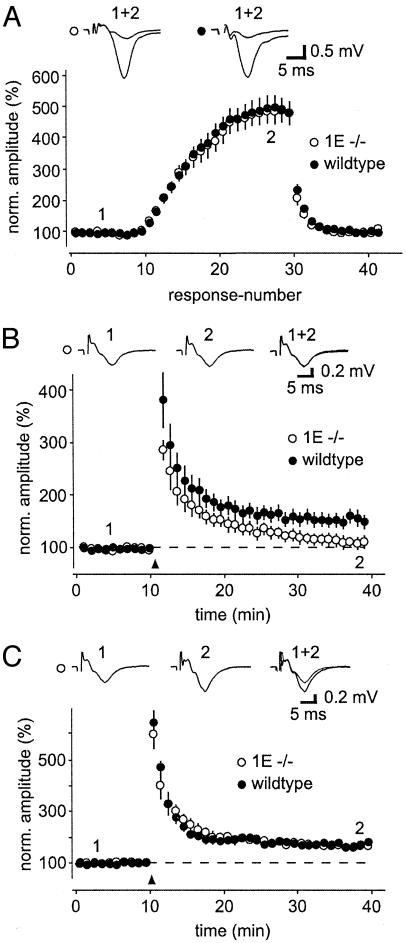

Next, we tested mossy fiber synaptic transmission and LTP in α1E-knockout (KO) mice (23). Initial experiments found no change in FF in α1E-KO mice. Changing the stimulus frequency from 0.05 to 1 Hz increased transmission to ≈500% of control in wild-type and α1E-KO mice (n = 11 and 9, respectively; Fig. 5A). PPF (40-ms interstimulus intervals), another form of short-term plasticity, was also not affected by the deletion of the α1E gene (wild type: 249 ± 19%, n = 10; α1E-KO: 245 ± 35%, n = 6; P = 0.46). We then tested mossy fiber LTP in wild-type and α1E-KO mice, and we found that the induction of mossy fiber LTP was less sensitive to repetitive stimulation in wild-type mice than in rats. We had to use a stimulus of 50 pulses (at 25 Hz) to get reliable LTP. In agreement with our pharmacological approaches, mossy fiber LTP was significantly reduced in the α1E-KO mice (155 ± 14% versus 112 ± 12%, n = 5; Fig. 5B). However, LTP could be rescued by applying a stronger tetanus (3 × 125 pulses at 25 Hz; Fig. 5C), again in accordance with our pharmacological data. Finally, forskolin-induced enhancement was not different between wild-type and α1E-KO mice (240 ± 8.5% in wild-type mice versus 249 ± 20% in α1E-KO mice; n = 4 and 3, respectively).

Fig. 5.

Mossy fiber LTP is impaired in α1E-KO mice. (A) F was not affected in α1E-KO mice. Mossy fiber synaptic transmission was elicited by a 0.05-Hz stimulation frequency, whereas FF was induced by 20 pulses at 1 Hz. (B) Mossy fiber LTP was induced in the presence of 2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid by 50 pulses at 25 Hz (n = 5). Note that LTP is blocked in the α1E-KO mice (n = 5). (C) When a very strong tetanus (3 × 125 pulses at 25 Hz) was given, mossy fiber LTP was no longer dependent on α1E-containing VDCCs (n = 4 each). Representative traces in B and C are from the same experiment (α1E-KO mice), in which 50 pulses failed to give LTP, whereas a strong tetanus caused LTP.

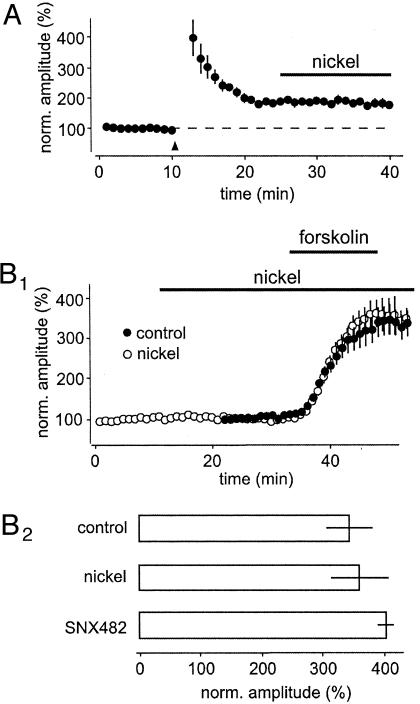

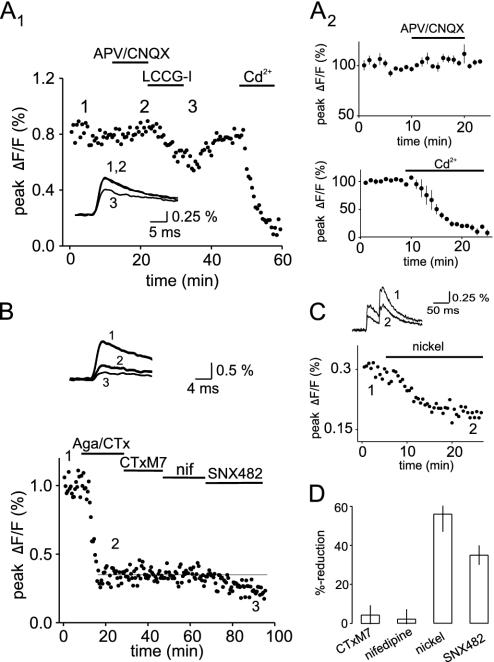

α1E-Containing VDCCs Contribute to Ca2+ Transients at the Mossy Fibers. Finally, to demonstrate the functional existence of α1E-containing VDCCs at mossy fiber terminals, we made use of an optical method to record Ca2+ transients in mossy fibers (30, 31). Mossy fibers were locally labeled with a pressure stream of the low-affinity calcium indicator magnesium green AM. Mossy fiber stimulation resulted in fast Ca2+ transients, which were insensitive to blockers of ionotropic glutamate receptors, but were reduced by group 2 metabotropic glutamate receptor agonists like L-CCG-I (n = 5) or DCG-IV (n = 5) (32) and blocked by cadmium (n = 3; Fig. 6A). These control experiments confirmed that we were indeed selectively recording from mossy fibers. Combined application of the P/Q- and N-type VDCC blockers in saturating concentrations (both at 1 μM) caused a clear reduction of the Ca2+ transients. However, these experiments revealed a residual component of the Ca2+ transients that was very substantial and contributed 34 ± 2% of the total signal (n = 7; Fig. 6B). To be certain that the remaining Ca2+ transient was not due to an incomplete block of P/Q- and N-type VDCCs, we additionally applied the highly potent, but nonspecific, antagonist ω-ConusTx-MVIIC (1 μM), which blocks P/Q- as well as N-type VDCCs. As shown in Fig. 6B, this treatment had no further effect on the Ca2+ transients (4.3 ± 5%, n = 4). Application of nifedipine (10 μM), an L-type VDCC blocker, also failed to have any effect on the remaining Ca2+ transient (2.2 ± 5%, n = 4). However, application of SNX-482 or nickel resulted in a substantial reduction of the residual Ca2+ transients (35 ± 5%, n = 6, and 56 ± 9%, n = 5; Fig. 6 C and D).

Fig. 6.

Calcium imaging reveals a remaining transient that is insensitive to blockers of P/Q-, N- and L-type calcium channels. (A1) Shown is a representative experiment demonstrating the selective recording from mossy fibers. Application of 2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (60 μM) and 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (30 μM) has no influence on the magnitude of the transient, excluding a postsynaptic contribution to the signal. Addition of the group 2 metabotropic-glutamate receptor agonist L-CCG-I (10 μM) reversibly reduces the transient, indicating its mossy fiber origin. Cadmium (200 μM) completely abolishes the calcium transient. Summary graphs for n = 5 and n = 3 experiments are depicted in A2.(B) Application of ω-AgaTx IVA and ω-CgTx GVIA in high concentrations of 1 μM strongly reduces the calcium transient, but a clear residual component could be seen. Further addition of ω-CgTx MVIIC and nifedipine did not influence this remaining component. However, the residual transient was reduced by SNX-482. Sample traces are taken at the indicated time points. (C) The experiment demonstrates the reduction of the residual transient with 100 μM nickel. Values are normalized to the transient amplitude in the presence of ω-AgaTx IVA and ω-CgTx GVIA (1 μM). (D) The bar diagram summarizes the reduction of the residual transient (in ω-AgaTx IVA and ω-CgTx GVIA) for ω-CgTx MVIIC, nifedipine, nickel, and SNX-482.

Discussion

Many excitatory synapses in the central nervous system undergo activity-dependent, long-lasting changes in synaptic strength, referred to as long-term depression or long-term potentiation. Both processes may underlie certain forms of memory. Most forms of LTP require the postsynaptic activation of NMDAR and the subsequent rise in intracellular calcium (1, 2). By contrast, LTP at mossy fiber synapses is completely independent of NMDAR activation (3–5). Furthermore, mossy fiber LTP is thought to be initiated and expressed presynaptically (8, 9, 17). Calcium is also required for this presynaptic form of LTP, because mossy fiber LTP cannot be induced in the absence of extracellular calcium (9). However, the ion channels through which calcium enters the presynaptic terminal have not been conclusively identified. We find that pharmacological blockade or genetic deletion of α1E-containing VDCCs causes an increase in the threshold for inducing mossy fiber LTP, although α1E-containing VDCCs are not absolutely required for this presynaptic form of LTP.

Role of α1E-Containing VDCCs in Synaptic Transmission at Mossy Fiber Synapses. We have found, in agreement with a recent publication (9), that ω-CgTx GVIA caused a strong and robust, but incomplete, block of mossy fiber synaptic transmission. The effect of ω-AgaTx IVA was even more pronounced, almost completely blocking synaptic transmission at the mossy fiber synapses. Combined application of both antagonists completely blocked mossy fiber transmission. In contrast, we tested SNX-482 at 200 and 500 nM and even up to 1 μM and could not find any effect on basal synaptic transmission. Nickel, which is assumed to block α1E-containing VDCCs as well, also had no effect on baseline synaptic transmission in our study. This result is in contrast to a recent study (27), which found that R-type calcium channels contribute to excitatory transmission in the rat hippocampus. We do not have an obvious explanation for the difference. Noteworthy, however, is the finding that PPF and FF were also not affected in the α1E-KO mice in the present study.

Interestingly, when synaptic transmission was completely blocked by the combined application of ω-AgaTx IVA and ω-CgTx GVIA, transmission could be restored by short, repetitive stimulation (Fig. 1C). It had been a long-held assumption that the used toxins act irreversibly. However, several publications reported that removal of ω-AgaTx IVA caused a recovery of P/Q-type VDCCs and that the recovery speeds up with very strong repetitive depolarizing pulses, e.g., +150 mV (33–35). We therefore applied the toxins continuously during these experiments and used only weak stimulation. In addition, the restored potentials were also found in the presence of ω-ConusTx-MVIIC. Most important, the recovered potentials in the presence of ω-AgaTx IVA and ω-CgTx GVIA were sensitive to SNX-482 and nickel, suggesting a role of α1E-containing VDCCs in mossy fiber transmission during sustained stimulation.

A Role for α1E-Containing VDCCs in Mossy Fiber LTP. Mossy fibers are exquisitely sensitive to repetitive stimulation. We have found that only 12 pulses at 25 Hz induced reliable and substantial LTP (Figs. 2 and 3A). Increasing the pulse numbers within the tetanus further increased the magnitude of mossy fiber LTP. In the presence of SNX-482, mossy fiber LTP could still be evoked; however, stronger tetani were necessary. By contrast, when mossy fibers were stimulated with fewer pulse numbers, LTP was effectively blocked. The same results could be obtained with nickel as well as with the α1E-KO mice, further supporting a role of α1E-containing VDCCs in mossy fiber LTP. α1E-VDCCs are therefore not an absolute requirement for mossy fiber LTP, but they do cause a substantial decrease in the threshold for inducing LTP. Recently, “natural stimuli” had been applied to mossy fiber synapses to study the impact of single granule cells onto the CA3 network (36); however, mossy fiber LTP had not been studied by using “physiological spike trains.” Evidently, dentate gyrus granule cells do not fire high-frequency action potentials for sustained periods of time (37, 38) during behavioral tasks, and it will therefore be of interest to study the contribution of α1E-containing VDCCs to mossy fiber LTP induced by physiological spike trains.

Are α1E-containing VDCCs involved in the induction of mossy fiber LTP or are they selectively up-regulated during LTP? If the expression of mossy fiber LTP were caused by a selective up-regulation of α1E-containing VDCCs, one might expect that α1E-containing VDCCs would contribute to synaptic transmission after LTP induction. However, we have found that LTP, once expressed, was not affected by blockade of the channel. Furthermore, neither application of SNX-482 or nickel, nor the deletion of the α1E-gene, had any impact on forskolin-induced enhancement of synaptic transmission. All lines of evidence clearly support the model that α1E-containing VDCCs are involved in the induction, rather than the expression mechanism, of LTP.

Ca2+ Channels at Mossy Fiber Terminals. What kind of evidence exists that α1E-containing VDCCs actually do exist at the mossy fiber synapse? First, Northern blot analysis and in situ hybridization have shown that the mRNA is highly abundant in dentate gyrus granule cells (20–22). In line with this result, R-type calcium currents have been identified in hippocampal granule cells of the dentate gyrus, which were highly sensitive to nickel and also inhibited by SNX-482 (29). Third, the distribution of α1E-containing VDCCs has been elucidated by using specific antibodies for α1E (22). The authors found an intense staining for α1E- in stratum lucidum of CA3, the termination zone for mossy fiber synapses (22). Calbindin immunoreactivity is also intense in stratum lucidum, where it has been shown to be localized in mossy fiber terminals. A comparison of the α1E-immunoreactivity with calbindin immunoreactivity suggests that the staining with the α1E antibody is likely to represent staining of mossy fiber axons and terminals. Third, we used an optical method to measure the calcium influx into mossy fibers (30). We have found that there was a substantial proportion of the calcium transients not blocked by antagonists for P/Q-, N-, and L-type VDCCs (Fig. 6). In contrast, the residual calcium transient was significantly reduced by nickel as well as SNX-482. Our data are in line with a recent report,∥ in which single mossy fiber boutons were imaged and SNX-482-sensitive calcium channels were found.

Conclusion

We report evidence that α1E-containing VDCCs are involved in the induction of mossy fiber LTP, although this channel does not contribute to basal synaptic transmission. This suggests a functional separation where P/Q- and N-type VDCCs are responsible for vesicle release during basal synaptic transmission, whereas Ca2+ ions passing through α1E-containing VDCCs can access the key molecules for mossy fiber LTP, e.g., adenylyl cyclase I. Mice lacking Cav2.3 (α1E) have abnormal nociceptive behavior and an abnormal emotional state (39). Especially interesting is the fact that these mice are also severely impaired in hippocampus-dependent spatial memory tasks, despite normal synaptic plasticity in area CA1 (40). It will also be of interest to study the effects of α1E-containing VDCCs in synaptic transmission and plasticity at other synapses as well. Interestingly, plasticity at the parallel fiber synapses in the cerebellum shows great similarity to LTP at the hippocampal mossy fiber synapse (41). Imaging of calcium transients in parallel fibers revealed that substantial calcium enters the terminals through non-P/Q- and non-N-type VDCCs (42).

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Gundlfinger for critical reading of the manuscript. R.A.N. is a member of the Keck Center for Integrative Neuroscience and the Silvio Conte Center for Neuroscience Research and is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and Bristol-Myers Squibb. D.S. is supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Emmy Noether Program, SFB618).

Abbreviations: LTP, long-term potentiation; NMDAR, N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor; VDCC, voltage-dependent calcium channel; L-CCG-I, (2S,1′S,2′S)-2-(carboxycyclopropyl)glycine; DCG-IV, (2S,2′R,3′R)-2-(2′,3′-dicarboxycyclopropyl)glycine; FF, frequency facilitation; PPF, paired pulse facilitation.

Footnotes

Yawo, H., Tokunaga, T., Miyazaki, K., Minami, H., Ishizuka, T., Yanagawa, Y. & Obata, K., Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting, Nov. 2–7, 2002, Orlando, FL, abstr. 115.4.

References

- 1.Bliss, T. V. & Collingridge, G. L. (1993) Nature 361, 31-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malenka, R. C. & Nicoll, R. A. (1999) Science 285, 1870-1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris, E. W. & Cotman, C. W. (1986) Neurosci. Lett. 70, 132-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zalutsky, R. A. & Nicoll, R. A. (1990) Science 248, 1619-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakazawa, K., Quirk, M. C., Chitwood, R. A., Watanabe, M., Yeckel, M. F., Sun, L. D., Kato, A., Carr, C. A., Johnston, D., Wilson, M. A., et al. (2002) Science 297, 211-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito, I. & Sugiyama, H. (1991) NeuroReport 2, 333-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tong, G., Malenka, R. C. & Nicoll, R. A. (1996) Neuron 16, 1147-1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weisskopf, M. G. & Nicoll, R. A. (1995) Nature 376, 256-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castillo, P. E., Weisskopf, M. G. & Nicoll, R. A. (1994) Neuron 12, 261-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bortolotto, Z. A., Clarke, V. R., Delany, C. M., Parry, M. C., Smolders, I., Vignes, M., Ho, K. H., Miu, P., Brinton, B. T., Fantaske, R., et al. (1999) Nature 402, 297-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsia, A. Y., Salin, P. A., Castillo, P. E., Aiba, A., Abeliovich, A., Tonegawa, S. & Nicoll, R. A. (1995) Neuropharmacology 34, 1567-1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mellor, J. & Nicoll, R. A. (2001) Nat. Neurosci. 4, 125-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeckel, M. F., Kapur, A. & Johnston, D. (1999) Nat. Neurosci. 2, 625-633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicoll, R. A. & Malenka, R. C. (1995) Nature 377, 115-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang, H. & Storm, D. R. (2003) Mol. Pharmacol. 63, 463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weisskopf, M. G., Castillo, P. E., Zalutsky, R. A. & Nicoll, R. A. (1994) Science 265, 1878-1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang, Y. Y., Li, X. C. & Kandel, E. R. (1994) Cell 79, 69-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villacres, E. C., Wong, S. T., Chavkin, C. & Storm, D. R. (1998) J. Neurosci. 18, 3186-3194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith, S. M., Piedras-Rentera, E. S., Namkung, Y., Shin, H. S. & Tsien, R. W. (1999) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 868, 175-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soong, T. W., Stea, A., Hodson, C. D., Dubel, S. J., Vincent, S. R. & Snutch, T. P. (1993) Science 260, 1133-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yokoyama, C. T., Westenbroek, R. E., Hell, J. W., Soong, T. W., Snutch, T. P. & Catterall, W. A. (1995) J. Neurosci. 15, 6419-6432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Day, N. C., Shaw, P. J., McCormack, A. L., Craig, P. J., Smith, W., Beattie, R., Williams, T. L., Ellis, S. B., Ince, P. G., Harpold, M. M., et al. (1996) Neuroscience 71, 1013-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson, S. M., Toth, P. T., Oh, S. B., Gillard, S. E., Volsen, S., Ren, D., Philipson, L. H., Lee, E. C., Fletcher, C. F., Tessarollo, L., et al. (2000) J. Neurosci. 20, 8566-8571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmitz, D., Mellor, J. & Nicoll, R. A. (2001) Science 291, 1972-1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geiger, J. R. & Jonas, P. (2000) Neuron 28, 927-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamiya, H., Shinozaki, H. & Yamamoto, C. (1996) J. Physiol. 493, 447-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gasparini, S., Kasyanov, A. M., Pietrobon, D., Voronin, L. L. & Cherubini, E. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 8715-8721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newcomb, R., Szoke, B., Palma, A., Wang, G., Chen, X., Hopkins, W., Cong, R., Miller, J., Urge, L., Tarczy-Hornoch, K., et al. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 15353-15362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sochivko, D., Pereverzev, A., Smyth, N., Gissel, C., Schneider, T. & Beck, H. (2002) J. Physiol. 542, 699-710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Regehr, W. G. & Tank, D. W. (1991) J. Neurosci. Methods 37, 111-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Regehr, W. G., Delaney, K. R. & Tank, D. W. (1994) J. Neurosci. 14, 523-537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamiya, H. & Ozawa, S. (1999) J. Physiol. 518, 497-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mintz, I. M. & Bean, B. P. (1993) Neuropharmacology 32, 1161-1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sather, W. A., Tanabe, T., Zhang, J. F., Mori, Y., Adams, M. E. & Tsien, R. W. (1993) Neuron 11, 291-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Randall, A. D. & Tsien, R. W. (1997) Neuropharmacology 36, 879-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henze, D. A., Wittner, L. & Buzsaki, G. (2002) Nat. Neurosci. 5, 790-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jung, M. W. & McNaughton, B. L. (1993) Hippocampus 3, 165-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiebe, S. P. & Staubli, U. V. (1999) J. Neurosci. 19, 10562-10574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saegusa, H., Kurihara, T., Zong, S., Minowa, O., Kazuno, A., Han, W., Matsuda, Y., Yamanaka, H., Osanai, M., Noda, T., et al. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 6132-6137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kubota, M., Murakoshi, T., Saegusa, H., Kazuno, A., Zong, S., Hu, Q., Noda, T. & Tanabe, T. (2001) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 282, 242-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salin, P. A., Malenka, R. C. & Nicoll, R. A. (1996) Neuron 16, 797-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mintz, I. M., Sabatini, B. L. & Regehr, W. G. (1995) Neuron 15, 675-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]