Abstract

Purpose

Methamphetamine (MA) has become the leading drug of abuse in northern Thailand over the past several years, particularly among youth. The current qualitative study examines factors associated with MA initiation.

Methods

Between March 2002 and January 2003, 48 in-depth interviews with young MA users were conducted in advance of a randomized, MA harm reduction, peer outreach intervention trial. The interviews were conducted in Chiang Mai city and the surrounding district. Data were inductively analyzed using the constant comparative method common to grounded theory methods. Atlas-ti was used for data management.

Results

Participants were 57% male and had a median age of 20 years (range: 15–31). A culture of MA ubiquity characterized participants’ initiation stories. Drug ubiquity encompassed three elements: the extent of MA use within peer networks; the availability of MA; and exposure to MA prior to initiation. All participants were introduced to MA by people close to them, most often by their friends. Internal reasons for trying MA were curiosity, a way to lose weight or enhance hard work, and a way to “forget life’s problems.” With the prevalence of MA use among participants’ peers, initiation was characterized as inevitable.

Conclusions

Initiation was characterized as ubiquitous in terms of peer networks’ use and availability. Due to the prevalent norm of MA use, these data indicate that interventions targeting social networks and young Thais prior to MA initiation are needed.

Keywords: methamphetamine, qualitative, youth, Thailand

Introduction

Thailand has experienced a marked rise in methamphetamine (MA) use since the early 1990s, with estimated numbers of MA users increasing from 850,000 in 1999 to more than 2.5 million in 2002 [1]. Treatment admissions for MA also rose substantially in Thailand, from 0.4% of all admissions in 1993 to 51.5% in 2002 [2] with adolescents comprising 60% of new MA-related admissions. Until relatively recently, heroin, marijuana, and alcohol were the principal substances abused in Thailand [1]. MA first appeared in Thailand in the 1960s and was primarily used by laborers to enhance performance in physically demanding professions, such as fishing and truck driving [3]. Accordingly, MA was referred to as ya-khayan, “diligence drug” [4]. Over time, MA use expanded from this realm to that of Thai youth, escalating during the rapid economic expansion of the early 1990s [2]. At this time, MA was renamed to its current name, yaba, meaning “crazy drug.” [4].

MA is a synthetic central nervous system stimulant which releases high levels of dopamine, thereby enhancing mood [5]. Long-term use can result in dopamine reduction, which can result in severe mood disorders as well as paranoia, violent behavior, depression, psychosis, and cardiopulmonary damage [5].

In Thailand, MA use is frequently referred to as an epidemic among youth and young adults [4, 6–8]. In a large school- and community-based study of 13–18 year olds (N=2,311) in Bangkok, 37% of students had used MA at least once in their lifetime [9]. In a large sample of MA admissions to Thanyarak Hospital, 60% were between 15 and 19 years old [2]. In a study of vocational students (N=1,175) in Northern Thailand, 29% reported having ever used MA [8].

Throughout the world, drug initiation largely occurs in adolescence and is the result of a confluence of individual and environmental factors, the latter of which are social, economic, and cultural in nature [9–12]. Numerous studies have documented the impact of peer influence on adolescent experimentation and continued use of illicit substances [9–12]. Adolescence is a developmental stage which is often characterized by a shift in social influence from parents to peers which occurs on a continuum. This brief article examines factors associated with methamphetamine initiation among older adolescent and young adult drug users in Northern Thailand.

Methods

Formative research was conducted in Chiang Mai, Thailand by the Chiang Mai University Research Institute for Health Science in collaboration with the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health. This research was in advance of a randomized HIV risk reduction randomized trial targeting young MA users and their network members. In-depth interviews with MA users (n=48) were collected between February, 2002 and May, 2003. Interviews were conducted in a private location at the recruitment or study site by seven interviewers who had received an in-depth, two-week training by the study’s first and second author. Long-term training occurred during weekly study meetings where interviews were discussed and interviewing techniques were reviewed.

Study sample

Targeted sampling was used to recruit the study sample, which is a purposive and systematic but flexible method for sampling hidden and uncounted populations [13]. We sampled individuals to obtain representation on three domains: current versus former MA use; urban versus rural living; and gender. Recruitment and sampling occurred through outreach in the provincial drug treatment center, rural health centers, organizations targeting youth, and rural villages located throughout Chiang Mai province. Participants were recruited from the following: 52% from the Northern Thai Drug Treatment Center, 27% from organizations in Chiang Mai City; and 21% from rural villages.

Selection of recruitment sites were based on our previous relationships with such entities as the Northern Drug Treatment Center, recommendations from our key informants who were former MA using young adults, and staff contact with organizations that served youth in Chiang Mai. During recruitment, study staff regularly frequented recruitment venues and by way of staff introduction, approached potential study participants. Flyers regarding the study were posted at each site.

Eligibility criteria were being between the ages of 15 and 29 years old and having use MA within the past year. None of the individuals approached for interview refused to participate. Prior to participating, respondents completed informed consent procedures in Thai. Respondents received a project t-shirt and snack. The study was approved by the Thai Ministry of Public Health Ethical Committee, the Human Experiment Committee of Chiang Mai University, and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Committee on Human Research.

Data collection

The semi-structured interview guide consisted of questions addressing a variety of topics, including: family history; drug use patterns and influences; sexual behaviors; drug cessation history; and history of drug treatment. In-depth interviews, ranging from forty-five minutes to one and a half hours, were conducted in Thai and tape recorded. The recordings were transcribed in Thai and then translated into English. Translations were reviewed for language accuracy by project staff who were fluent in both languages.

Data analysis

Two qualitative researchers, the study’s first two authors, analyzed the data thematically in a multi-step process using the constant comparative method that is central to grounded theory [14]. Initially, five interviews were chosen for open coding, a process of reading small segments of text at a time and making notations in the margins regarding content or analytic thought. The coders met and compared and agreed upon a synthesized coding list which was used to code the next five interviews after which the code list was further refined and used to code the remaining interviews. Additionally, analytic memos were written throughout the coding process to reflect on themes within and across interviews. Data were entered into Atlas–ti version 4.2, a qualitative data management program, to organize project coding and memos.

Results

Sociodemographics and drug use

Respondents (N=48) were 57% male and had a median age of 20 years (range: 15–31). Seventy percent of participants reported that they were not currently using MA. The remaining participants reported weekly MA smoking. Respondents reported having used MA a median of 3.5 years and 30% reported having used other drugs, primarily glue and alcohol, prior to MA use

Qualitative Themes

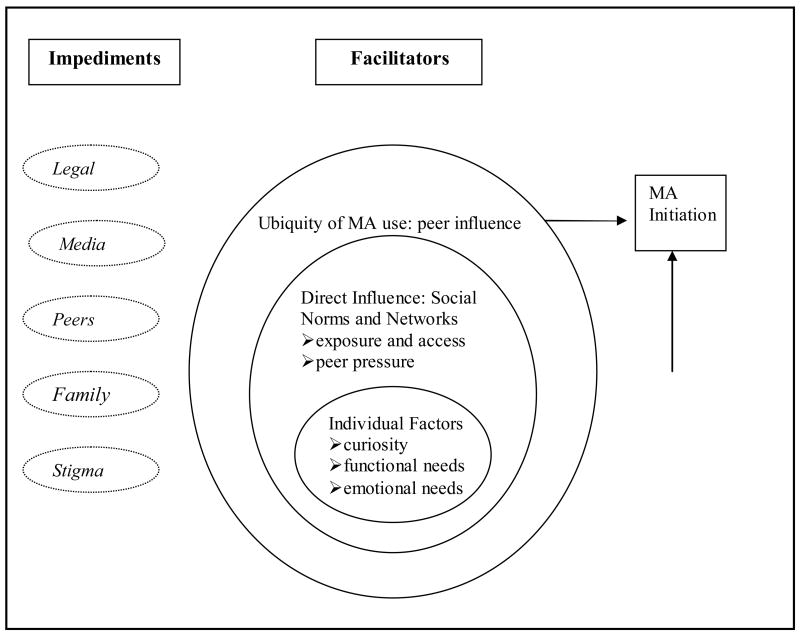

Figure 1 displays the impeding [not discussed] and facilitating factors in MA initiation that were reported by study respondents. Facilitating factors occurred at both distal and proximal levels. Distal factors included: the broader context of being an adolescent and the shifting influence of parents and peers; the ubiquity of MA among Thai youth, where MA was perceived as normative; and the negative portrayal of MA in the media. Proximal influences included exposure to MA by peers, peer pressure, and easy access to MA through peer networks. Individual-level factors, which are influenced by the pervasiveness and availability of MA, included curiosity, functional needs (e.g., weight loss), and emotional needs.

Figure 1.

Impeding and Facilitating Factors in Yaba Initiation among Thai Youth

Ubiquity of MA

Prior to MA initiation, awareness of the extent of MA use was high and therefore perceived as normative. The ubiquity of MA was an underlying theme in both distal and proximal aspects of respondents’ lives and encompassed three elements: pre-use awareness of drugs; the ease of accessibility/availability of drugs; and the extent of drug use within participants’ social networks. For initiation, MA ubiquity functioned as a contextual level within which individuals were influenced directly and indirectly. The ubiquity of MA’s impact on initiation was undeniable and was created by both impeding factors, such as extensive media attention on MA seizures and related arrests, and facilitating factors, such as friends’ use.

Direct Influence: Social Norms and Networks

Exposure and access

Exposure and access to MA by individuals within their social sphere created the perception of MA use as normative. Ninety percent of respondents described witnessing MA use by their peers prior to their first use. Exposure to MA use contributed to respondents’ perception that using MA was a usual behavior among teens. “I had seen it. I just would like to try. I am a teenager.” [Male, age 23]

By far, peers were the most common group of people who played a role in both exposing and initiating respondents. Explicit or inexplicit peer pressure was mentioned by the majority of participants. Peer networks functioned as a pressure to initiate, whether explicitly or implicitly, creating social norms around MA use as acceptable and almost expected, and modeling use such that most respondents had been exposed to friends’ using prior to their own first use. A 17 year old man reported having seen his friends use MA more than 20 times. When asked why he used it the first time, he said, “Because they were my friends, I could not keep saying no. If I said no again, that could damage our relationship.”

Among those with MA use within their close group of friends, over half of respondents described feeling indirect pressure to use MA in order to belong. They felt that they would not be fully accepted among their friends unless they also used MA, as expressed by this 19 year old male, “I just wanted to get along with my friends and to socialize with them.” Although the number of times that people were exposed to MA varied, the common theme was that over the course of time, people finally tried it. Several respondents talked about initial hesitation about using MA, but ultimately started using due to the synergy of frequent exposure and the degree to which MA was a part of their social networks.

I was a very good student. I never missed my class. But when I came to Poly, I had heard people talk about it since my first year. I saw people using it for two years without touching it. But when I was in the third year, my friend said that it helped us work. I had many reports to hand in, so I used it. [Female, age 21]

At first I didn’t know how to play [use MA] - just watched friends... for about a year. I had seen the others for 4–5 times without touching it. One day I stole one fourth of a pill to try. It was fun. I got along with everyone. [Female, age 18]

Peer Pressure

Peer pressure was the largest facilitating factor in MA initiation and existed on a continuum from implicit encouragement to explicit verbal persuasion. Although respondents had friends that did not use MA, the implicit and explicit pressure in favor of MA from their friends and broader peer groups had more of an influence. Peer pressure manifested in many forms of persuasion, including social isolation by the very fact that respondents did not “join in.” While not always effective at first, pressure to initiate resulted in decisions to try MA.

At that time a friend of mine was in his own group and he kept asking me to try it. I never did. Then before graduating he said ‘let’s try it and then you will know what it is like’. I said ok because we would soon be graduating… I didn’t want to try because people said it was not a good thing and I agreed. But my friends persuaded me.. and it was all around me. It’s like they all stayed together and used together, except me. So it seemed like I was a stranger in my group. [Male, age 18]

Pressure to use MA also took the form of being offered MA in payment for outstanding debts or just as a gift.

I lent him money because he told me he had a debt and a creditor would come to attack him. After a long time, I asked him for payment of the debt. He told me that he had no money, but sent me an orange tablet. At that time, I did not know what it was. He told me that it was yaba. I was alarmed and asked, ‘why do you give me?’ He answered that he gave me to try. [Male, age 21]

Respondents described their friends taking an active role in initiating them, including being taught how to use the drug or using strategies to convince others to try.

A friend got it from a 10th grade student. We went into the restroom and he asked if I knew it and if I wanted to try. He showed me how to use it and I just did what he did.” [Female, age 24]

There was a degree of emotional manipulation in persuading friends to try MA mentioned by several participants. “My friend gave the drug to me and said if I didn’t take it I wasn’t his friend. And I loved my friend so much and didn’t want to disappoint him, so I took it.” [Male, age 19]

Individual Factors

Curiosity

Seven participants mentioned “curiosity” as the reason for trying MA, resulting from consistent exposure to the drug. In response to asking why she wanted to try it, a 17 year old said, “I thought I am only alive once and I wanted to know what it was like.” The mere availability of MA peaked participants’ interest in trying it.

Before I first tried it, I hadn’t seen anyone using it before. So why did you want to try it? A friend of mine left a tablet with me so I asked him what it was and he replied yaba. So I just tried it. [Male, age 18]

Among those who had used other types of drugs before MA, the curiosity about trying MA was even less consequential. They described their interest in trying MA as simply a continuation of their interest in trying anything that seemed like it might be fun.

It’s normal for me. I liked this sort of thing already so when someone offered it to me and it’s free, then I tried it. Firstly, it’s free and then a friend offered it so I tried. Just took it! [Female, age 17]

In many instances, satisfying curiosity about MA by using the first time occurred with little thought of continued use. However, consistent exposure to MA in respondents’ immediate social circles often resulted in consistent opportunities to use the drug again. Persistent opportunities to use MA with peers were a large factor in continued use. “They gave it to me once in a while – sometimes they would give it to me daily for three to four days – they would come and ask me to join.” [Male, age 17]

Functional needs

Seven respondents described MA initiation as serving a specific purpose such as enhancing productivity at work or school or personal gains such as losing weight. Several male participants received MA for the first time at work by a work colleague. As one 21 year old said, “I was energetic and industrious. It kicks in within five seconds. I felt like I wanted to work, work non stop. At lunch break I didn’t want to stop or take a break.” Another participant expressed described a similar scenario.

I felt I could work more and could earn more as well. For example, when we delivered cement powder, we got 400 Baht [$10.25 USD] for one trailer that contained about 520 packages. If we didn’t take yaba we would be able to deliver only one or two trailers. But when we took yaba, we felt the time pass faster, we became diligent, we didn’t feel hungry or tired. Thus we could deliver more than two trailers and sometimes we could earn 1000 Baht [$25.64 USD] each. We invested only 80 Baht [$2.05 USD] for one pill of yaba and we shared it, so we each paid half. However, our intake increased while we still earned the same amount of money as we couldn’t deliver more than four or five trailers a day. [Male, age 28]

Another role that required great productivity was that of school. Many initiated MA in response to challenges with school responsibilities and difficulty achieving academic goals. Upon taking the drug, respondents often experienced the desired surge in energy and productivity. A 20 year old woman’s statement typified the desired result and effect of MA use for school, “I had just entered a new boarding school at age 13. I was worried about my grades so I asked someone to give me yaba to help me study.” The decision to use MA for practical reasons was often influenced by another person’s suggestion or by having witnessed others successfully using the drug for these reasons.

Some respondents also described trying MA in order to lose weight, yet this was a relatively rare response. The number of participants who talked about this being a reason for initiation did not differ by gender.

My friend at college told me that the drug could help me to lose my weight. That time my weight was above 80 kilograms. He did not persuade me to use drug for this purpose, but I myself wanted to try. [Male, age 21]

Emotional Needs

MA was also reputed to assist in coping with emotional challenges, primarily derived from family strife. Over 20% of the sample discussed unhappy family relationships and trouble within steady relationships as the emotional precursor to MA initiation. MA was a viable coping mechanism in response to stress, emotional voids, or interpersonal conflicts. A 17 year old male discussed initiating MA after his parents separated. In response to how it made him feel, he said, “all troubles are gone and easily solved.” Others’ comments reflect similar sentiments.

My parents quarreled quite often. They quarreled, when my mother knew my father had another woman then she divorced him. So I separated from the family… When I took yaba, it make me feel relaxed, I didn’t worry about my family anymore. [Male, age 18]

Discussion

In this study, we explored influences on MA initiation among young adults in Chiang Mai, Thailand. We found that initiation was influenced by a range of social and individual level factors that often occurred in tandem, within a context of extensive exposure to MA through a variety of sources. Peer influence was the overriding influencing factor on initiation, as found in numerous other studies [10–12, 15]. Decisions to try MA occurred in a context of the drugs’ ubiquity. The results indicate to a number of points of intervention, detailed below.

In participants’ immediate environment, social networks and related norms functioned as vehicles of exposure and access to MA, resulting in tacit or explicit peer pressure that supported initiation. Peer pressure resulted both implicitly from normative behaviors within peer groups, as well as explicitly, through verbal pressure. One of the key mechanisms by which a person feels connected to their social environment is that of “belonging.” A “sense of belonging” is the value a person places on connecting to and identifying with a group [16]. Belonging to a group engenders feelings of being important to others and trusting that members’ needs will be met through their mutual commitment [17]. MA was inextricably tied to participants’ social life as it was portrayed as a necessity for group membership.

Adolescence is a developmental period in which parental influence is largely replaced by that of peers, particularly regarding drug use [11, 12, 18]. This is not to diminish the important of parental support and its potential mediating role in preventing drug abuse. But rather to underscore the need for harnessing peer influence in the prevention of drug initiation. In our study, MA was used to escape family strife. Twenty percent of participants attributed, in part, MA initiation to discordance with their parents, pointing to the need for enhancing communication between parents and their children and providing healthy outlets for teens to deal with their emotions around difficult family relationships.

Due to the large role of peer influence during adolescence, it is important to comment upon its potential for influencing positive and protective health behaviors, not just its role in promoting risk. Harnessing peer pressure and social influence into vehicles for risk reduction can have far-reaching positive influence on youth and young adults and has been shown to be successful interventions in risk reduction among drug users [19, 20]. As mentioned, the current study was a part of formative data collection in advance of a randomized peer outreach intervention trial that aimed to intervene upon social influence in the promotion of HIV prevention and health seeking behaviors among young MA users. The study’s results informed the intervention content in several ways. First, emphasizing the importance of not using MA in front of friends who do not use MA. Secondly, the importance of teaching and modeling communication skills about drug use, the needs that it fulfills, and ways to reduce risk. Lastly, the formative work underscored the need to discuss and brainstorm effective communication techniques with parents. Another intervention implication is the potential effectiveness of interventions that target both MA users and their families.

Depending on individuals’ specific situation or needs, the drug was seen as a panacea for physical and emotional deficits, including being overweight, needing energy, or dealing with intense emotions. MA, as with many mood altering substances, filled deficiencies in participants’ lives. Although results have been mixed, several studies have found a significant relationship between low self-esteem and adolescent substance abuse [21, 22]. Self-esteem is an important leverage point that could mitigate the effects of peer influence on drug initiation, particularly in the context of extensive drug availability.

The most effective intervention in the abatement of MA initiation could truly be reducing supply in Thailand. The nature of such interdiction is complicated and beyond the scope of this paper. The recent government efforts to diminish the supply and consumption of MA in Thailand, the 2003 year long “war on drugs,” resulted in numerous human rights violations and a temporary reduction in both consumption and supply [23, 24]. Given the relatively easy production of MA in small spaces with readily available chemical precursors, supply reduction is a major challenge. Within a context of heightened drug availability, these findings strongly point to the need to intervene at the peer level by reshaping social norms around drug initiation as well as the importance of targeting underlying factors that shape vulnerability to drug initiation.

There are several limitations to the current study. The sample was not randomly selected and therefore generalizability is limited. Over half of participants were in drug treatment and close to 80% were not currently using MA, which could have influenced their thoughts about initiation. Given such high rates of drug cessation and treatment, the sample could be more representative of heavier users that the general population of MA users. Due to ethical issues in recruiting minors who smoke MA, we were unable to interview young a large number of MA users, those under 18, who would have initiated more recently and possibly subject to less recall bias. As our sample was specifically selected based on having used MA, no inferences can be drawn about the trajectory of initiating various drugs over time. The current study did not aim to validate the gateway theory, which is the most widely tested and debated theory of sequential drug use over time [10–12]. Over two-thirds of participants reported having used alcohol and marijuana prior to MA use, a typical progression that has been previously documented in similarly aged samples [2, 10, 25–28]. Lastly, all participants had previously used MA, limiting our ability to explore protective factors from initiation among youth with similar exposures. Much could be learned from future research with adolescents exposed to friends who use drugs but do not initiate drug use.

This study is one of the first to qualitatively explore spheres of influence on MA initiation among a sample of youth. Results demonstrate the degree of exposure to and the extent of pressure that participants felt in experimenting with MA. Methamphetamine filled numerous voids and needs in participants’ lives – providing them with a sense of belonging, a source of energy, a way of fitting in. The ubiquity of MA in participants’ distal and proximal social environments provides both challenges and many possible points of intervention. As such, results lend support for interventions that focus on individual factors such as self esteem as well as social factors such as social norms.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Drug Abuse (DA14702). We thank all of the participants who shared their stories and our staff.

Footnotes

Institution Work Should Be Attributed: Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Office of the Narcotics Control Board of T. Thailand Narcotics Annual Report. 2002. Report No.: 1-03-2545.

- 2.Verachai V, Dechongkit S, Patarakorn A, et al. Drug addicts treatment for ten years in Thanyarak Hospital (1989–1998) Journal of Medical Association of Thaialnd. 2001;84(1):24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poshyachinda V. Drug injecting and HIV infection among the population of drug abusers in Asia. Bulletin of Narcotics. 1993;45(1):77–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farrell M, Mardsen J. Methamphetamine: drug use and psychoses becomes a major public health issue in the Asia Pacific Region. Addiction. 2002;97:771–772. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anglin MD, Burke C, Perrochet B, et al. History of the methamphetamine problem. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32(2):137–141. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Razak MH, Jittiwutikarn J, Suriyanon V, et al. HIV prevalence and risks among injection and noninjection drug users in northern Thailand: need for comprehensive HIV prevention programs. 2003;33(2):259–266. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306010-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melbye K, Khamboonruang C, Kunawararak P, et al. Lifetime correlates associated with amphetamine use among northern Thai men attending STD and HIV anonymous test sites. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;68(3):245–253. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sattah MV, Supawitkul S, Dondero TJ, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for methamphetamine use in northern Thai youth: results of an audio-computer-assisted self-interviewing survey with urine testing. Addiction. 2002;97(7):801–808. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruangkanchanasetr S, Plitponkarnpim A, Hetrakul P, Kongsakon R. Youth risk behavior survey: Bangkok, Thailand. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;36:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kandel DB, Yamaguchi K, Chen K. Stages of progression in drug involvement from adolescence to adulthood: Further evidence for the Gateway theory. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1992;53(5):447–457. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stenbacka M. Initiation into intravenous drug abuse. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1990;85(5):459–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb05481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamaguchi K, Kandel DB. Patterns of drug use from adolescence to young adulthood: II. Sequences of progression. American Journal of Public Health. 1984;74(7):668–672. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.7.668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watters JK. A Street-based outreach model of AIDS prevention for intravenous drug users; preliminary evaluation. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1994:411–471. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kandel DB. Stages in adolescent involvement in drug use. Science. 1975;190:912–914. doi: 10.1126/science.1188374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagerty BMK, Patusky K. Developing a measure of sense of belonging. Nursing Research. 1995;44(1):9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMillan DG, Chavis DM. Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology. 1986;14(1):6–26. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pomery EA, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, et al. Families and risk: prospective analyses of familial and social influences on adolescent substance use. J Fam Psychol. 2005;19(4):560–570. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Latkin CA, Sherman SG, Knowlton A. HIV prevention among drug users: Outcome of a network-oriented peer outreach intervention. Health Psychology. 2003;22(4):332–339. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.4.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broadhead RS, Heckathorn DD, Weakliem DL, et al. Harnessing peer networks as an instrument for AIDS prevention: results from a peer-driven intervention. 1998;113 (Suppl 1):42–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dielman TE, Shope JT, Butchart AT, et al. A covariance structure model test of antecedents of adolescent alcohol misuse and a prevention effort. Journal of Drug Education. 1989;19(4):337–61. doi: 10.2190/5H81-YKY1-BV7V-1DA5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young M, Werch CE, Bakema D. Area specific self–esteem scales and substance use among elementary and middle school children. Journal of School Health. 1989;59(6):251–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1989.tb04716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vongchak T, Kawichai S, Sherman S, et al. The Influence of Thailand’s 2003 ‘War on Drugs’ Policy on Self-Reported Drug Use Among Injection Drug Users in Chang Mai, Thailand. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2005;16:115–121. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherman SG, Aramrattana A, Celentano DD, Beyrer C, Pizer H. Public Health and Human Rights. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; Researching the effects of the Thai drug “war on drugs:” Public health research in a human rights crisis. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golub A, Johnson BD. Variation in youthful risks of progression from alcohol and tobacco to marijuana and to hard drugs across generations. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(2):225–232. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donovan JE, Jessor R, Jessor L. Problem drinking in adolescence and young adulthood. A follow-up study. Journal on the Study of Alcohol. 1983;44(1):109–197. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1983.44.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu A, Kilmarx P, Jenkins RA, et al. Sexual initiation, substance use, and sexual behavior and knowledge among vocational students in northern Thailand. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2006;32(3):126–35. doi: 10.1363/3212606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brecht ML, Greenwell L, Anglin MD. Substance use pathways to methamphetamine use among treated users. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(1):24–38. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]