Abstract

Previous researchers have comprehensively documented rates of HIV disclosure to family at discrete time periods yet none have taken a dynamic approach to this phenomenon. The purpose of this study is to address the trajectory of HIV serostatus disclosure to family members over time. Time to disclosure was analyzed from data provided by 125 primarily single (48.8%), HIV-positive African American (68%) adult women. Data collection occurred between 2001 and 2006. Results indicated that women were most likely to disclose their HIV status within the first seven years after diagnosis, and mothers and sisters were most likely to be told. Rates of disclosure were not significantly impacted by indicators of disease progression, frequency of contact, physical proximity, or relationship satisfaction. The results of this study are discussed in comparison to previous disclosure research, and clinical implications are provided.

INTRODUCTION

Historically, HIV has been considered a disease of young men who have sex with men (MSM). An examination of recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention1 supports this assertion, as 70% of the cumulative diagnosed cases of HIV occurred in men. However, the number of women who are becoming infected and who are living with HIV, particularly those of minority status, is a matter of significant concern. In 2005, the Centers for Disease Control reported that 29.5% of all newly diagnosed cases of HIV in the United States occurred in women, and that 68% of all cases among women were among African Americans.1

Disclosure in women with HIV

HIV disclosure has been described as “a sensitive issue often causing stress and apprehension due to the uncertainty of how people would react.” 2(p Partners, family members, and friends usually provide security and serve as sources of emotional support. However, the prejudice and stigma which is associated with HIV/AIDS may significantly impact this network of significant relationships. Research with international samples of women has also suggested that the fear of stigma from family and friends significantly impacts decisions about disclosure.3 Existing research regarding HIV disclosure among women has primarily focused on disclosure to sexual partners4–7 and children.8–11 Moreover, there is a lack of research comparing the disclosure processes of HIV positive men and women, and few studies that focus solely on women. Perceived difficulty of disclosing a positive HIV test result to support network members, such as family, may impact some women’s desire to be tested for HIV. Crosby et al.12 reported that women who indicated they would not be tested for HIV were also more likely to report high disclosure difficulty; conversely, women who had large, caring support networks reported less perceived disclosure difficulty. Therefore, a clearer understanding of the context of women’s HIV disclosure to family members also has implications for HIV prevention.

Disclosure to nuclear family

Disclosure to family members has mostly been examined within the context of general patterns of disclosure.12–15 This line of research suggests that women disclose frequently in the first year of their diagnosis, and that family members are typically the initial targets of disclosure. For example, among 322 HIV-positive women, in various stages of disease progression, Sowell and colleagues14 reported that 96% of women had disclosed their HIV status, and that 78% of these disclosures occurred within a week of receiving their diagnosis. Parents (33%) and husbands (24%) were most likely to be the initial targets of disclosure.

In contrast, Simoni and colleagues13 reported that disclosure rates were highest to lovers and friends among an ethnically diverse sample of 65 women. In fact, 87% of lovers and 78% of friends had been informed of the participants’ HIV status, compared to 58% of mothers and 31% of fathers. In terms of HIV-related support, approximately 38% of the women indicated they had discussed concerns with any of the six specified targets. Family members were more likely to provide support than social workers, friends, counselors, physicians, or religious leaders. Reactions to disclosure were generally positive, with mothers, fathers, and friends reported to be emotionally supportive, and rarely angry or withdrawn. In contrast, lovers were more likely to respond with anger and withdrawal.

Possible predictors of disclosure

Understanding disclosure to family members is important because disclosure is imperative for the acquisition of support and this support has been demonstrated to improve the lives of those living with HIV.16–19 One generally accepted theory of HIV disclosure contends that disease progression triggers disclosure.20–22 According to the disease progression theory, individuals disclose their HIV diagnosis as they become increasingly ill because keeping it a secret becomes complicated.20,21 That is, disease progression results in hospitalizations and health deterioration which requires individuals to explain their health condition.21 Furthermore, if death is imminent or individuals fear they will need additional assistance to manage the final stage of their illness, they may disclose as a means of accessing requisite resources.23 More recently, HIV therapies have advanced considerably resulting in individuals failing to exhibit a standard pattern of declining health. In fact, HIV is now considered a chronic yet manageable disease.24–26 HIV/AIDS treatment advances, in particular that of HAART, may play a role in decisions regarding disclosure.

The heuristic utility of the disease progression theory has been substantiated through numerous studies of HIV-positive men.27–30 However, few studies have examined the link between disease progression and disclosure among women with HIV, and the results of this research have been contradictory.8,11,29 Kirshenbaum and Nevid8 reported women who had known their diagnoses longer also had children who were aware of their illness. In contrast, multiple studies conducted by Simoni and colleagues have demonstrated that stage of illness and time since diagnosis were not associated with indicators of disclosure. Furthermore, the relationship between HAART and HIV disclosure has not been thoroughly examined among women. Siegal and colleagues7 compared disclosure to sexual partners among women who had not received highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), and women who were currently receiving this treatment. Although the majority of women had disclosed their HIV status to their primary sexual partners, no significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of reasons for disclosure or reactions to disclosure.

In one recent test of the disease progression theory, a relationship between disease progression and disclosure was not found, suggesting that disease progression may not play a central role in the decision to disclose an HIV diagnosis.31 In this study, it was suggested that individuals are more likely to evaluate the outcome of disclosure to particular family members and to base disclosure decision on the weighting of both positive and negative consequences of such an action. That is, individuals weigh the rewards and costs associated with the need for disclosure to each family member. Until the rewards of disclosure outweigh possible repercussions, disclosure does not occur.

This alternative explanation for HIV disclosure has also found support in the literature.27,32,33 Notably, this research has traditionally been conducted with samples of HIV positive men. These researchers contend that individuals who are HIV-positive contemplate the need for privacy and disclosure in determining whether to disclose an HIV-positive diagnosis. Factors to be deliberated are poorly understood, yet it can be argued that this decision making process may be based on numerous factors related to either the family member or HIV-positive person. Family member characteristics might include the age of the family member at the time of disclosure,6,30 satisfaction with the relationships,13 intimacy with individual,7,22 race/ethnicity, and the role of family member.22,25,27,29 For example, the aforementioned studies have found that, of family members, mothers and sisters are the most likely to be told of an HIV diagnosis. Participant characteristics might include age of the participant at the time of disclosure to a particular family member and race/ethnicity of participant.13,29,34 For example, Simoni and colleagues13 reported that younger women and Latina women who spoke English were more likely to disclose and to seek support for HIV-related concerns than older women, and Latina women who spoke little or no English. Pregnancy status, a characteristic unique to women, has also been highly correlated with disclosure difficulty. Crosby and colleagues12 reported that women who were not currently pregnant were more likely to report greater perceived difficulty with disclosure than pregnant women.

It is interesting to note that previous researchers have comprehensively documented rates of disclosure via point prevalence studies and none have taken an extended perspective of this phenomenon. In addition, many of these studies were conducted in the early 1990s before the introduction of antiretroviral therapies. Thus, an updated and more comprehensive investigation of this phenomenon is warranted. The purpose of this study is to investigate the trajectory of HIV serostatus disclosure by women to specific immediate family members. To this end, the influence of disease progression, family network characteristics, and participant characteristics on rates of disclosure will be investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and recruitment

Participants for this study were 125 HIV-positive women involved in a larger, longitudinal study of the HIV disclosure. The purpose of this study was to document the occurrence and timing of HIV disclosure. These women were recruited primarily from a Children’s Hospital (FACES), an AIDS Clinical Trials Unit (ACTU) associated with a large university, and AIDS Service Organizations (ASOs) throughout a midwestern state. Recruitment began in October of 2001 and continued through March 2004. At the clinics flyers were posted in waiting rooms and attending physicians and medical staff approached potential participants and informed them about the study. ASOs included information about the study in newsletters and posted flyers in waiting rooms. Because of the diversity of recruitment strategies used a refusal to participate rate could not be computed. Eligible participants included HIV positive women who were 18 years of age or older.

Procedures

Participants were interviewed and completed questionnaires once every 6 months for 3 years resulting in seven data collection points. While the parent study involved collecting data longitudinally, the data used in this study were not longitudinal, but rather retrospective data. Participants were interviewed by trained doctoral students about their social network using an adaptation of Barrera’s Arizona Social Support Interview Schedule (ASSIS).35 Participants were asked to whom they would discuss personal issues, receive advice, borrow money, invite to socialize, garner positive feedback, request physical assistance, and experience negative interactions (i.e., argue or fight). In addition, they were asked with whom they had sexual interactions within the past 6 months.

From each structured interview a list of social support network members (those individuals mentioned during the ASSIS interview) was constructed. Demographic information (i.e. age, gender, and ethnicity) of each network member and information including their knowledge of participant’s HIV status, the length of relationship, and the participant’s satisfaction with each relationship was obtained. Then, participants were asked if each individual in their social network, including their immediate family, knew of their diagnosis. If a particular person did have knowledge of the diagnosis, we first probed as to who was the discloser. Because secondhand disclosure can happen easily in families (particularly between parents or siblings), interviewers spent a considerable amount of time probing to determine exactly how the disclosure occurred. Typical responses included, “I did,” “My mother did,” “I don’t know.” If the participant personally disclosed, the month and year of that disclosure was obtained. If the participant was unsure if the network member knew, this was noted and if the network member did not know of the diagnosis, it was recorded as a nondisclosure. Ages at the time of disclosure for both the participant and their network member were calculated for each disclosure.

It should be noted that much of the data reported here is retrospective in nature, and therefore some caution is advisable. However, when the data was collected we understood that such information could be inherently flawed so training procedures for data collection and handling were instituted to minimize error. First, considerable time was given for participants to tell their disclosure story. Given this was a memorable event, such reconstruction of events came easily to most. Interviewers were trained to allow participants the opportunity to recollect the events surrounding their testing and diagnosis. Probes such as, “Where did you get tested?” and “Who was with you when you found out?” were offered. This sufficiently contextualized the event for many. Second, for those who were uncertain as to an exact month but remembered the year, probes such as, “Was it winter, spring, summer or fall?” “Was it before or after Christmas?” were offered to assist with recall. Third, if the person appeared to be obviously guessing or did not know for sure, the interviewer further contextualized the situation by including probes such as, “Where were you?”, “Was it over the phone or in person?”, “How did they respond?” This allowed for the determination if a disclosure actually occurred or if the network member found out through other means (e.g., family member, family friend, gossip, or guessed). If the participant was certain that they had disclosed their status, but couldn’t recall a year, again attempts were made by the interviewer to assist with memory recall. Triggers, such as, “Where were you living at the time?” or “Where were you working?” all assisted with attempts to jog the participant’s memory. In some instances, family members may have found out accidentally (e.g., found medication, overheard phone messages). These instances were not counted as disclosure. For this study, in order to be classified as a disclosure, the participant themselves must have actually disclosed their HIV status to that family member. These procedures netted 339 family members reported by 117 women.

Dependent measure

The dependent variable of interest is the event of disclosure by an individual with HIV of her serostatus to a family member. Time to disclosure to each family member is measured in months from the date of HIV-diagnosis to the date of disclosure of HIV serostatus. Survival analysis is an appropriate statistical methodology for analyzing this data because the data meet all necessary requirements of a clear time origin, a scale for measuring time, and a clear end point.37 Survival analysis provides an estimate of the proportion of the sample that would have been disclosed to at various times. Family members who have not been told of the participant’s HIV status were treated as “censored” data.38 Censored data, however, are not considered missing data. Rather, labeling them censored takes into account that although the participant did not disclose their serostatus to a family member, there is the potential that they could disclose this information to this individual in the future. That is, they remain “at-risk” for disclosure.37

Independent variables

Disease progression

Two variables related to disease progression were measured. First, is whether the participant was diagnosed with HIV pre- or postadvent of HAART. With the 1995 Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the protease inhibitors, “triple combination therapy” was introduced and quickly became the standard of care by 1996. For this analysis, pre-HAART is defined as being diagnosed prior to 1995 and post-HAART is defined as being diagnosed in 1996 and after. Second, length of infection at entry into the study was calculated using date of diagnosis obtained from medical records.

Family characteristics

Demographic information of family members included age at the time of disclosure and race. Current satisfaction with the relationship was measured with one question, “How satisfied are you with your relationship with this person?” Participants responded using a 1–5 Likert-type rating scale ranging from “very satisfied” (1) to “very dissatisfied” (5). Frequency of contact was measured with one question, “How much contact do you have with this person?” Participants responded using a 1–5 rating scale ranging from “daily contact” (1) to “no contact” (6). Proximity was measured with one question, “How far does this person live from you?” Participants responded on a 1–6 rating scale ranging from “live together” (1) to “several states away” (6).

Participant characteristics

The age of the participant at the time of disclosure to each family member and whether there was any reported prior disclosure to other family members were calculated and entered in the analysis. The latter was entered as a time-varying covariate. Mode of transmission was self-reported in the demographic questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

Kaplan-Meier–type cumulative disclosure curves stratified by family member were estimated and the log rank test used to test the equality of the disclosure curves. A multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression model was used to estimate the hazard ratios and standard errors. A shared frailty approach that is a semiparametric random effects model that can account for within group correlation was utilized. The distribution of the baseline hazard function is not specified while the frailties or random effects are gamma distributed with a mean of one and a variance of q which is estimated from the data and is testable. If the null hypothesis (q = 0) is rejected then the correlation is considered significant and cannot be ignored. Thus, the non-independence of one participant providing information regarding several family members is controlled for in the statistical analysis. In this study the frailty is the participant’s degree of willingness to disclose to family members.

RESULTS

Participants were primarily single (i.e., not partnered; 48.8%) women between the ages of 18 and 63 (M = 37.7 years, SD = 9.4), who contracted HIV from unsafe sexual practices (88%). A majority of the women were African American (68%) or Caucasian (25%). At entry into the study, participants had been diagnosed with HIV ranging from 1 month to 19 years (M = 81 months, SD = 48.8). Approximately 41% of these women reported having had some college education or a bachelor’s degree and 2.5% reported having completed some graduate work. More than 78.2% of the participants were unemployed, earning an average monthly income of $1,569 (R = $0–$6,600).

Women who did not report any family members (n = 8) were excluded from the analyses. Of the 117 included participants, 94 reported a mother or stepmother and 74 reported a father or stepfather. These women also reported having 117 brothers or stepbrothers and 148 sisters or stepsisters (Table 1). Family members were primarily African American (mothers, 63.8%; fathers, 68.9%; sisters, 72.3%; brothers, 69.2%). Mothers ranged in age from 34 to 87 (M = 59.5 years, SD = 10.9), fathers from 40 to 91 (M = 61.5 years, SD = 9.5), sisters from 19 to 94 (M = 41 years, SD = 10.2) and brothers from 19 to 66 (M = 38.7 years, SD = 9.3). Of the 433 family members, only 6 individuals were disclosed to after the participant entered into the research study. Of the 93 mothers identified, 13 had been told by someone else, and 1 was deceased. Of the 73 fathers identified, 16 had been told by someone else and none were deceased. Of the siblings, 32 sisters and 29 brothers had been told by someone else.

Table 1.

Number of Participants with a Particular Number of Siblings

| Number of siblings

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Sisters | 51 | 33 | 23 | 9 | 6 | 2 | 1 |

| Brothers | 54 | 44 | 13 | 12 | 1 | 1 | |

| Step or half siblings | 122 | 2 | 1 | ||||

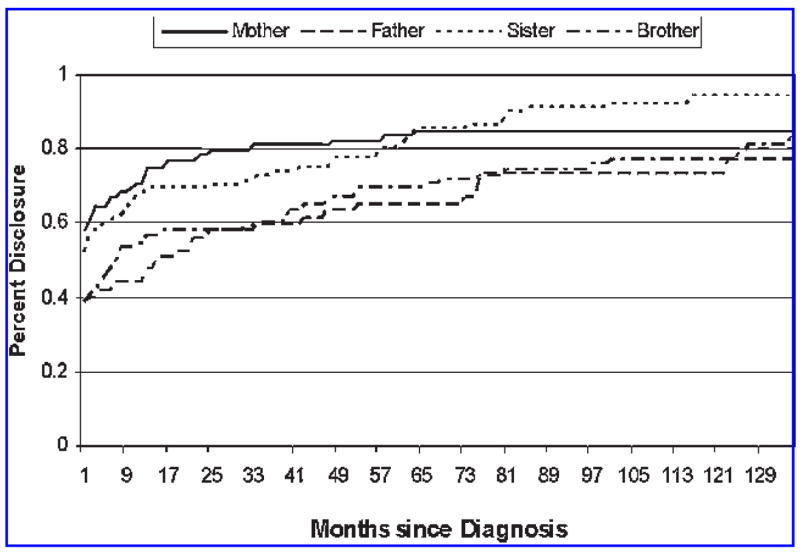

In order to investigate the trajectory of HIV serostatus disclosure to specific immediate family members, data were analyzed separately by family member using Kaplan-Meier cumulative disclosure curves. Of the 339 family members reported by these women, 83.8% had been told about the HIV status of the participant. This included 86.1% of mothers, 73.7% of fathers, 90.4% of sisters, and 79.5% of brothers. These percentages increased when calculated on the 430 family members that include those told by someone else. According to cumulative disclosure proportion analysis,* it would be expected that 67% of mothers would be disclosed to within 0–6 months. In the same time period, it would be expected that approximately 44% of fathers, 62% of sisters or 50% of brothers would be disclosed to regarding HIV status. The mean time to disclosure for mother and sisters was 31 months and 27 months, respectively, 78 months for fathers, and 53 months for brothers. A graphic representation of cumulative disclosure curve for family members is shown in Figure 1.

FIG. 1.

Cumulative disclosure curve for family members.

Family member

In order to investigate the influence of family role in the prediction of HIV disclosure over time, data were analyzed using a Cox proportional hazard regression model. This analysis provides estimates of the hazard rate (relative risk) without having to specify a baseline hazard. In comparison to fathers, sisters and brothers, mothers served as the comparison group. The other family comparison pairs are displayed in Table 2. Within-group correlations are controlled for in all models as in all cases the null hypothesis was rejected that q = 0. The effect of family role (model 1) on the time to disclosure is shown in Table 2. The hazard ratios were statistically significant for comparisons of fathers to mothers (1.72) and sisters (1.66). These ratios indicate that at all time points after HIV diagnosis, mothers have a 72% and sisters have a 66% greater rate of being disclosed to in comparison to fathers. Statistically significant differences were found for the hazard rates of comparisons of sisters to brothers (0.68), and brothers to mothers (1.52). These ratios indicate that brothers have a 32% less rate of being disclosed to in comparison to sisters, while mothers have a 52% greater rate of being disclosed to in comparison to brothers.

Table 2.

Hazard Ratios and Standard Errors of HIV-Serostatus Disclosure to Family Member

| Model number | Family member 1 | Disease model 2 | Family characteristics 3 | Participant characteristics 4 | Combined model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family membera | |||||

| Father vs. mother | 1.72 (0.36)** | 1.73 (0.37)** | 1.32 (0.29) | 1.79 (0.39)** | 1.30 (0.27) |

| Father vs. sister | 1.66 (0.34)* | 1.69 (0.34)** | 0.70 (0.19) | 2.00 (0.42)** | 0.92 (0.23) |

| Father vs. brother | 1.13 (0.24) | 1.14 (0.24) | 0.57 (0.16) | 1.33 (0.29) | 0.75 (0.19) |

| Sister vs. motherb | 1.03 (0.18) | 1.02 (0.18) | 1.87 (0.44)* | 0.89 (0.16) | 1.41 (0.30) |

| Sister vs. brotherb | 0.68 (0.12)* | 0.68 (0.12)* | 0.81 (0.14) | 0.66 (0.12)* | 0.81 (0.13) |

| Brother vs. motherb | 1.52 (0.28)* | 1.51 (0.28)* | 2.31 (0.57)** | 1.34 (0.25) | 1.73 (0.39)* |

| Pre/Post HAART | |||||

| Length of diagnosis | 0.75 (0.22) | ||||

| Race of family memberc | 1.00 (0.01) | ||||

| Age of family member | 1.08 (0.16) | ||||

| Satisfaction with family member | 0.98 (0.01)* | 0.99 (0.01) | |||

| Frequency of contact with family member | 0.99 (0.06) | ||||

| Proximity with family member | 0.97 (0.05) | ||||

| Age of participant | 0.99 (0.01) | ||||

| Prior disclosure | 0.38 (0.06)*** | 0.44 (0.06)*** | |||

| Sample Size | 339 | 339 | 246 | 284 | 273 |

| Model χ2/df | 11.43/3** | 13.90/5* | 13.10/8 | 49.11/5*** | 43.33/5*** |

| Model log-likelihood | −1490.76 | −1489.63 | −1155.41 | −1300.21 | −1296.75 |

| χ2 test of θ (1 df) | 29.33*** | 31.14*** | 0.12 | 2.48* | 0.26 |

The first family member listed serves as the referent group.

Hazard ratios and standard errors were calculated separately based upon dummy coding with father as the referent group.

Other minorities serves as the referent group compared to Africa-American.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

Disease model

The family member model is elaborated upon in model 2 by testing the influence of disease progression on disclosure to family. Whether the participant was diagnosed pre- or post-HAART and the length of diagnosis at entry to the study were entered into the analysis. The hazard ratios among family members remain very similar, and again, statistically significant differences are only found for the hazard ratios between fathers and mothers (1.73), fathers and sisters (1.69), sisters and brothers (0.68), and brothers and mothers (1.51). Neither the timing of the HIV diagnosis (pre-/post-HAART) nor the length of diagnosis significantly influenced the hazard rates. That is to say that at all points in time, being diagnosed before or after HAART did not significantly alter the rate of disclosing one’s HIV-serostatus. Also, how long an individual was diagnosed with HIV at entry to the study did not alter the rate of HIV disclosure.

Family characteristics

Characteristics of the participant’s family network were added to the analysis in model 3, substituting for the disease variables. The hazard rate for only age of the family member was statistically significant. At all points after diagnosis, being one year older as a family member is associated with a lesser risk of disclosure by 2%. Race, satisfaction, frequency of contact, and proximity did not significantly impact the hazard rate. With the addition of the network characteristics, the impact of family role changes. No longer are the hazard rates between fathers and mothers or sisters statistically significant. Instead, results demonstrate that at all time points mothers have an 87% greater rate of being told than sisters, and a 131% greater rate of being told than brothers.

Participant characteristics

In model 4, the network characteristics were removed, and the impact of participant characteristics were assessed. Only prior disclosure to other family members significantly impacted the hazard rate. As the participant moved from having no prior disclosure to having prior disclosure to family members, the rate of disclosure is 62% less. With the addition of participant characteristics, the impact of family role changes again. Statistically significant results were found again in the hazard ratios of father to mother (1.79) and sisters (2.00). In addition, at all points in time since diagnosis, brothers had a 34% less risk to be told than sisters.

Combined model

In the final model, significant factors in both family and participant characteristics were combined with family role. Only the impact of prior disclosure significantly influenced the hazard rates. At all points in time since HIV-diagnosis, prior disclosure to family members is associated with 56% lower rate of being disclosed to, and mothers had a 73% greater rate compared to brothers.

DISCUSSION

Rates of HIV serostatus disclosure to family members have not been examined extensively in samples of women; existing studies have mostly employed point prevalence designs. Therefore, while disclosure proportions at discrete time points are generally understood, accurate longer-term disclosure estimates have not been calculated with female samples. Looking at disclosure proportions in this manner is important because it may provide a better estimate of overall disclosure patterns to family.

Results from this research reveal that within 1 month of diagnosis, 60% of mothers, 40% of fathers, 57% of sisters, and 40% of brothers will receive information about a family member’s HIV status. After 2 years, 80% of mothers, 58% of fathers, 70% of sisters, and 58% of brothers will be told by the infected family member. These rates appear to level off after 7 years. Given the relative stability of these rates, it is expected that little change would occur beyond 12 years. This finding is congruent with finding from studies of MSM38 suggesting a universal aspect to HIV disclosure.

From the data gathered in point prevalence disclosure studies,13,14 researchers have indicated that family members most likely to receive information about HIV status were mothers and sisters in contrast to fathers and brothers. The current assessment of cumulative disclosure curves concurs with previous researchers because, over time, mothers remain the most likely to be recipients of HIV status information. Overall, mothers and sisters tend to be told first and proportions of their knowing remains elevated over other family members across time. This stands in contrast with previous studies of MSM that found only mothers were told first and remained better informed over all family members over time.38 These results are also different from those of Simoni and colleagues13 in which women’s rates of disclosure to mothers and sisters were considerably lower.

One explanation for the greater tendency for female family members to be disclosed to in this study could be attributed to them being viewed as more sympathetic and nurturing. Suh and colleagues39(p asserted that because women are often placed in the role of caretaker they may “adopt patterns of affiliative and caring behaviors that can be termed communal.” Female family members may also be perceived as more motivated than male family members to maintain connections despite life circumstances. Compared to men, women have been found to have a conversational style that tends to foster relationship growth and to place greater emphasis on establishing similarities in experiences.40 Women may also view other women as more readily available or able to provide requisite support than men because of an assumption or perception of shared experiences. In this study, the percentage of sisters who had been disclosed to was slightly greater than that of mothers. In addition, as age of the family member increased, the likelihood of disclosure decreased. The idea of a shared experience would be present for all female family members; however, because sisters would be much closer in age and experience than mothers, women may have a more stable history of sharing important personal information with their sibling.

Results of this study further call into question the explanatory power of the disease progression theory. As argued previously7,11,38 advances in HIV/AIDS treatment may not play a significant role in decisions regarding disclosure. In model 2, being diagnosed with HIV pre- or post-HAART was not a significant factor associated with risks of disclosure for women. Given medical advances it is plausible that those infected may have adapted their disclosure decisions accordingly. It should be noted that there were other indices of disease progression collected for this study but it was not collected retroactively to when these women would have disclosed. Therefore, in this study women’s current medical condition or use of HAART were not included as indicators.

Previous researchers have noted that physical proximity such as coresidency or degree of contact with family may be important predictors of disclosure.38 That is, women who live great distances from their families or have infrequent contact with family may disclose less than those who are in greater contact or live closer. In this study neither proximity nor frequency of contact was important in the disclosure trajectory. One possible explanation for this finding is that advances in personal communication technology, such as the Internet and text messaging, may allow for better communication over space. Additional research is needed to elucidate the role of technology and physical proximity in the disclosure process.

Interpretative caution may be required because of the retrospective nature of these data. Although participants were carefully guided through the disclosure interview process, it is plausible that erroneous data was provided. This might be particularly true for participants diagnosed several years prior to the study. To the best of our knowledge, however, this is the only effort to attempt to capture a very difficult family process occurring at a time of great discrimination, high anxiety and emotion. Thus, while a prospective account would be most desirable, unfortunately, such data will never be available for this time period.

CONCLUSION

HIV infection among U.S. women has increased significantly in the past 20 years. As a result, more women are infected and affected by this disease. The results of this study suggest that women are most likely to disclose their HIV status within the first seven years after diagnosis, and that their female relatives are the most likely targets for disclosure. Interventions that are specifically targeted to women may need to be developed in order to address the obvious gender differences present in patterns of disclosure to family members. This information may be helpful to normalize the disclosure process for women and to assist them with selecting targets for disclosure. Future research should examine how gender and age may differentially influence family members’ responses to disclosure, as well the impact of disclosure on women’s mental and physical health and social support. Clinicians who work with families affected by HIV need to address the gender gaps in disclosure knowledge in order to increase social support in an attempt to reduce any negative emotional impact that disclosure may have on women.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the National institutes of Mental Health (R01MH62293) and supported by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group Grant AI259254. The authors thank the women who participated in the study.

Footnotes

To determine if the proportion hazard assumption was violated, a test of the nonzero slope in a generalized regression of the scaled Schoenfeld residuals on functions of time was run. The null hypothesis of zero slope, and violation of the proportion hazard assumption, was tested both globally and individually for each family member. Both global [χ2(3) = 3.11, p ≥ .05] and individual tests failed to violate the proportion hazard assumption. The null hypothesis was not rejected and the proportion hazard assumption was not violated.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [(Last accessed February 27, 2007)];HIV/AIDS surveillance report: Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and dependent areas. 2005 www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/2005report/pdf/2005SurveillanceReport.pdf.

- 2.Beauregard C, Solomon P. Understanding the experience of HIV/AIDS for women: Implications for occupational therapists. Can J Occup Ther. 2005;72:113–120. doi: 10.1177/000841740507200206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar A, Waterman I, Kumari G, Carter AO. Prevalence and correlates of HIV serostatus disclosure: A prospective study among HIV-infected postparturient women in Barbados. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2006;20:724–730. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciccarone DH, Kanouse DE, Collins RL, et al. Sex without disclosure of positive HIV serostatus in a US probability sample of persons receiving medical care for HIV infection. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:949–954. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duru O, Collins RL, Ciccarone DH, et al. Correlates of sex without serostatus disclosure among a national probability sample of HIV patients. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:495–507. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9089-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollander D. Large proportions of men and women with HIV have sex without telling partners that they are infected. Reprod Health. 2003;35:235–236. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegal K, Lekas H, Schrimshaw EW. Serostatus disclosure to sexual partners by HIV-infected women before and after the advent of HAART. Women Health. 2005;41:63–85. doi: 10.1300/J013v41n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirshenbaum SB, Nevid JS. The specificity of maternal disclosure of HIV/AIDS in relations to children’s adjustment. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14:1–16. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.1.1.24331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Letteney S, LaPorte HH. Deconstructing stigma: Perceptions of HIV-seropositive mothers and their disclosure to children. Soc Work Health Care. 2004;38:105–123. doi: 10.1300/J010v38n03_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mellins CA, Kang E, Leu C, Havens JF, Chesney MA. Longitudinal study of mental health and psychosocial predictors of medical treatment adherence in mothers living with HIV disease. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2003;17:407–416. doi: 10.1089/108729103322277420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simoni JM, Davis ML, Drossman JA, Weinberg BA. Mothers with HIV/AIDS and their children: Disclosure and guardianship issues. Women Health. 2000;31:39–54. doi: 10.1300/J013v31n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crosby R, Bonney EA, Odenal L. Correlates of perceived difficulty in potentially disclosing HIV-positive test results: A study of low-income women attending an urban clinic. Sex Health. 2005;2:103–107. doi: 10.1071/sh04044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simoni JM, Mason HRC, Marks G, Ruiz MS, Reed D, Richardson JL. Women’s self-disclosure of HIV infection: Rates, reasons, and reactions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:474–478. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.3.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sowell RL, Seals BF, Phillips KD, Julious CH. Disclosure of HIV infection: How do women decide to tell? Health Educ Res. 2003;18:32–44. doi: 10.1093/her/18.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gielen AC, Fogarty L, O’Campo P, Anderson J, Keller J, Faden R. Women living with HIV: Disclosure, violence, and social support. J Urban Health. 2000;77:480–491. doi: 10.1007/BF02386755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hays RB, Chauncey S, Tobey LA. The social support networks of gay men with AIDS. J Comm Psych. 1990;18:374–385. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hays RB, Turner H, Coates TJ. Social support, AIDS-related symptoms, and depression among gay men. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:463–469. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.3.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leserman J, Perkins DO, Evans DL. Coping with the threat of AIDS: The role of social support. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;11:1514–1520. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.11.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zich J, Temoshok L. Perceptions of social support in men with AIDS and ARC: Relationships with distress and hardiness. J App Soc Psychol. 1987;17:193–215. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Babcock JH. Involving family and significant others in acute care. In: Aronstein DM, Thompson BJ, editors. HIV and Social Work. Harrington: 1998. pp. 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalichman SE. Understanding AIDS: A Guide for Mental Health Professionals. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hays RB, McKusick L, Pollack L, Hilliard R, Hoff C, Coates TJ. Disclosing HIV seropositivity to significant others. AIDS. 1993;7:425–31. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199303000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holt R, Court P, Vedhara K, Nott KH, Holmes J, Snow MH. The role of disclosure in coping with HIV infection. AIDS Care. 1998;10:49–0. doi: 10.1080/09540129850124578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beaudin CL, Chambre SM. HIV/AIDS as a chronic disease: Emergence from the plague model. Am Behav Sci. 1996;39:684–06. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McReynolds CJ. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease: Shifting focus toward the chronic, long-term illness paradigm for rehabilitation practitioners. J Voc Rehab. 1998;10:231–40. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nokes KM. Revisiting how the chronic illness trajectory framework can be applied for persons living with HIV/AIDS. Sch Inq for Nurs Prac. 1998;12:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marks G, Bundek NI, Richardson JL, Ruiz MS, Maldonado N, Mason HRC. Self-disclosure of HIV infection: Preliminary results from a sample of Hispanic men. Health Psychol. 1992;11:300–306. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.5.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marks G, Richardson JL, Ruiz MS, Maldonado N. HIV-infected men’s practices in notifying past sexual partners of infection risk. Public Health Rep. 1992;107:100–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mason HRC, Marks G, Simoni JM, Ruiz MS, Richarson JL. Culturally sanctioned secrets? Latino men’s nondisclousre of HIV infection to family, friends, and lovers. Health Psych. 1995;14:6–12. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simoni JM, Demas P, Mason HRC, Drossman JA, Davis ML. HIV disclosure among women of African descent: Associations with coping, social support, and psychological adaptation. AIDS Behav. 2000;4:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serovich JM. A test of two HIV disclosure theories. AIDS Educ Prev. 2001;13:355–364. doi: 10.1521/aeap.13.4.355.21424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Derlega VJ, Lovejoy D, Winstead BA. Personal accounts of disclosing and concealing HIV-positive test results: Weighing the benefits and risks. In: Derlega V, Barbee A, editors. HIV Infection and Social Interaction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Derlega VJ, Metts S, Petronio S, Margulis ST. Self-Disclosure. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mason HRC, Simoni JM, Marks G, Johnson CJ, Richardson JL. Missed opportunities? Disclosure of HIV infection and support seeking among HIV+ African-Americans and European-Americans. AIDS Behav. 1997;1:155–162. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barrera M., Jr . Social support in the adjustment of pregnant adolescents: Assessment issues. In: Gottlieb BH, editor. Social Networks and Social Support. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1981. pp. 69–96. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Survival Analysis: Regression Modeling of Time to Event Data. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Serovich JM, Esbensen AJ, Mason TL. HIV disclosure to immediate family: A 20-year perspective. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2005;19:506–517. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suh EJ, Moskowitz DS, Fournier MA, Zuroff DC. Gender and relationships: Influences on agentic and communal behaviors. Pers Relat. 2004;11:41–60. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tannen D. You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men i Conversation. New York: Harper Collins Publishers, Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]