Abstract

MYCN amplification is associated with poor prognosis in neuroblastoma disease. To improve our understanding of the influence of the MYCN amplicon and its corresponding expression, we investigated the 2p expression pattern of MYCN amplified (n = 13) and nonamplified (n = 4) cell lines and corresponding primary tumors (n = 3) using the comparative expressed sequence hybridization technique. All but one MYCN amplified cell line displayed overexpression at 2p. Expression peaks were observed frequently at 2pter and less frequently at 2p24 (MYCN locus), 2p23.3–23.2, and/or 2p23.1. Importantly, cell lines and two corresponding primary tumors displayed expression peaks at similar loci. No significant 2p24 expression level was observed for those cell lines displaying a low amplification rate (n = 3) by comparative genomic hybridization. Only the cell lines with an enhanced peak at 2p23.2–23.3 displayed coamplification of the ALK gene (2p23.2), reported to be associated with unfavorable prognosis. Finally, two of four cell lines without MYCN amplification, both derived from patients with poor outcome, also showed an expression peak at 2p23.2. These data indicate that, besides MYCN, other genes proximal and distal to MYCN are highly expressed in neuroblastoma. The prognostic significance of expression peaks at 2p23.2–23.3, independent of MYCN and ALK status, remains to be investigated.

Neuroblastoma (NB) represents the most common extracranial solid tumor in children. As amplification of the MYCN gene (germ line position 2p24.3) readily identifies high-risk patients, the status of the MYCN gene is used for therapy stratification.1,2 Although MYCN status is used to guide therapy, the underlying biological mechanism resulting in aggressive cell behavior is still under discussion. One reason might rely on the composition and/or the organization of the amplicon, which can frequently be complex and not be restricted to the MYCN locus, but involve flanking and/or physically unrelated regions contributing to the aggressive phenotype of the disease. Finally, the correlation between MYCN copy number and MYCN expression has been rarely addressed.

The amplified MYCN sequences can be present in the form of double minutes or homogeneously staining regions (hsr). The size of the MYCN amplicon can extend anywhere from 350 kb to 8 Mb in length,3,4,5 demonstrating the great variability of amplicon sizes and the number of coamplified genes in NB. A frequently coamplified gene is DDXI (mapping position 2p24), belonging to a family of genes that encode DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box proteins, implicated in a number of cellular processes, eg, in posttranscriptional and translational gene regulation. Thus, high levels of DDXI expression resulting from genomic amplification may trigger distinct pathways. A number of studies focused on the copy number and/or expression of this gene to determine its prognostic implication. However, controversial findings were found on this subject.6,7,8,9,10 Moreover, contradictory publications were reported for the prognostic value of ID2 (inhibitor of DNA-binding/differentiation) (germ line position 2p25.1) expression.11,12,13 The function of NAG (neuroblastoma amplified gene), coamplified in 20 to 56%,8,14,15,16 is not known. Finally, coamplification of the ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase) gene is reported to occur rarely and is observed only in cases with poor outcome.17

In the last 2 years, array comparative genomic hybridization (CGH)5,18,19 and expression profiling20,21,22,23,24have increasingly been used to identify new genes involved in NB disease. However, published data are difficult to compare with each other for two main reasons. The various platforms contain non-equally distributed genes. A good demonstration has been given by Michels and colleagues dissecting the 2p amplicon of the cell line IMR-32 by the use of four different platforms consisting of Affymetrix 10K SNP chip, bacterial artificial chromosome array CGH, combined subtractive cDNA cloning, and Agilent Human Genome CGH MicroArray 44A oligonucleotide chips.18 The data generated illustrated that only the combination of various platforms identified all genes involved in the amplicon formation. Mosse and coauthors, using bacterial artificial chromosome clones with ∼1 Mb resolution, even claimed that the dissection of the MYCN amplicon was not feasible due to the low clone density in the 2p region.25 Moreover, recently used oligonucleotide arrays (eg, Affymetrix U95Av2), with a resolution at the kilobase level, have been shown to cover only 36% of the genes mapping at 2p24–25.26 Finally, the application of different software programs used for the complex microarray expression data analyses may additionally affect the output of the results.27 Another technique to assess the expression of genes can be performed by comparative expressed sequence hybridization (CESH), a simple, fast, and inexpensive assay that allows the identification of transcriptional activity at cytogenetically defined locations.28 Analogous to the CGH assay, differentially labeled amplified cDNAs derived from a test and a reference sample are cohybridized to normal human metaphase spreads. As normal chromosomes are used as targets to visualize the comparatively hybridized cDNAs, it can be assumed that all genes are represented in a nonbiased form. Included are miRNA gene loci and repeat sequences, which are usually missing on microarrays. One restriction of the CGH technique is limited resolution. Deletions need to be at least 10 to 12 Mb to fall within the detection limits of CGH when fixed threshold values of 0.8 are applied.29 However, the sensitivity of the technique is improved for detection of amplified regions. Although the current opinion states that the detection limit of amplified regions is 2 Mb, Joos and coworkers showed that CGH can detect an amplified region as small as 100 kb as long as the copy number has increased by at least 20.30 Concordant results were found by simulation analysis.31 Moreover, the sensitivity of the CGH is related to the size of the amplicon, decreasing with decreasing size.32 Finally, the sensitivity of the CGH technique can be improved by applying statistical thresholds.33 The amount of the data generated by CESH is much smaller than that generated by microarray analyses and the evaluation of the CESH data can be performed in one day. Moreover, CESH requires only nanogram quantities of RNA, and the method was already successfully applied to small biopsy samples, as reported by Lu and coauthors.34 CESH has also been applied successfully in different studies and shown to be suitable for tumor classification of rhabdomyosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, prostate cancer, and Wilms’ tumors with favorable histology.34 Furthermore, CESH analysis revealed differential gene expression in morphological breast cancer subtypes.35 Finally, the technique was used to predict the clinical behavior of patients with Wilms’ tumor.36 Therefore, we took advantage of this novel analytical tool to investigate the chromosomal 2p expression profiles of NB-derived cell lines and corresponding primary tumors to improve our understanding of NB with (MNA) and without (non-MNA) MYCN amplification and the resulting changes in affected cells. Furthermore, we correlated the 2p chromosomal expression with the corresponding genetic status of the cell lines, verified by CGH.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Patient Samples

In total, we investigated 17 well characterized NB cell lines that were derived from 17 patients. We included also five primary NB tumors samples from which the cell lines STA-NB-3, -4, -7, -11, and -15 were generated. Clinical parameters and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) data are presented in Table 1. The MYCN and/or 1p status of the cell lines STA-NB-3, -7, -8, -9, -10, -11, -12, -13, -15, and Vi-856 had been described previously.37,38 Moreover, the relative expression level and status of MYCN, NAG, DDX1, TEM8, and MEIS1 for three STA-NB cell lines were reported.15 Finally, we tested cell lines other than NB, including Ewing’s tumor (STA-ET-6), Wilms’ tumor (STA-WT-3), osteosarcoma (STA-OS-2), and breast carcinoma (ZR-75.1) cell lines. The clinical and cytogenetic data of these cell lines have been reported previously.39,40,41 STA-NB, STA-ET, STA-WT, and STA-OS cell lines were established in the laboratory of Dr. Ambros. The NB cell lines Vi-856 and LAN-1 and the breast carcinoma cell line ZR-75.1 were kindly provided by Dr. O. Majdic (Institute of Immunology, Vienna, Austria), by Dr. R. Seeger (Children’s Hospital, Los Angeles, CA) and by Dr. J. Moscow (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD), respectively. SK-N-SH was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. All cell lines were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin to 70 to 80% confluence for RNA, DNA, and protein extractions. As it is very difficult to obtain sufficient RNA from NB precursor cells, we used total RNA from pooled leukocytes from healthy donors as a reference sample.

Table 1.

Clinical, FISH, CGH, and CESH Data of 17 Human Neuroblastoma Cell Lines and Corresponding Primary Tumors

| Samples | Sex | Age* | Stage | Clinical status | FISH

|

CGH

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MYCN amplified | ALK amplified | Losses <−3δ | Over-represented regions >+3δ | |||||

| MNA | ||||||||

| STA-NB-1.1 | F | 3,5 y | 3 | DOD | + | −† | 2p21-pter | |

| PT STA-NB-3 | F | 13 m | 2 | DOD | + | n.d. | 2p14-pter,2q34–37 | |

| STA-NB-3 | + | − | 2p13–16.1,2p16.3- pter, 2q36–37 | |||||

| PT STA-NB-4 | M | 6 m | 4 | NED | + | n.d. | 2p21-pter, 2q33–34 | |

| STA-NB-4 | + | − | 2p22-pter | |||||

| STA-NB-5 | M | 6 m | 4s/4 | DOD | + | − | 2p21-pter | |

| PT STA-NB-7 | M | 18 m | 3 | NED | + | n.d. | 2p22-pter | |

| STA-NB-7 | + | n.d. | 2p23-pter | |||||

| STA-NB-8 | F | 28 m | 4 | DOD | + | − | 2p22-pter | |

| STA-NB-9 | F | 3 m | 4 | NED | + | − | 2p22-pter | |

| STA-NB-10 | M | 18 m | 3 | DOD | + | − | 2p16-pter | |

| PT STA-NB-11 | M | 36 m | 4 | NED | + | n.d. | 2p22-pter, 2q22 | |

| STA-NB-11 | + | − | 2p21-pter | |||||

| STA-NB-13 | M | 6 m | 4s/4 | NED | + | − | 2p12-2q14 | 2p14-pter,2q24–34, 2q36 |

| PT STA-NB-15 | M | 11 m | 4 | DOD | + | + | 2p21–24 | |

| STA-NB-15 | + | + | 2p16-pter,2q11–14 | |||||

| LAN-1 | M | ? | 4 | + | − | 2p13-pter,2q24-q37 | ||

| Vi-856 | F | ? | 4 | DOD | + | + | 2p12-pter,2q12-q37 | |

| Non-MNA | ||||||||

| STA-NB-2 | M | 18 m | 4 | NED | − | − | no | |

| STA-NB-6 | M | 4 m | 3 | NED | − | − | no | |

| STA-NB-12 | M | 8,5 y | 4 | DOD | − | − | no | |

| SK-N-SH | F | 4 y | 4 | DOD | −† | −† | 2p16-pter | |

(table continues)

Table 1A.

Continued

| CGH

|

CESH

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| CGH peak | Overexpressed regions>+3δ | CESH peak>+3δ | Underexpressed regions (CESH ratio <−3δ) |

| 2p24.3–24.2 | 2pter | 2pter | 2p22–2q14.1,2q23–24 |

| 2p25.1 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 2p25.2–25.1 | 2p23-pter | 2pter | 2p13–16,2q12–14.1,2q22–24,2q31–33 |

| 2p24.1 | 2p23-pter | 2p24.3 | 2p13–16,2q21–23,2q32–33 |

| 2p24.3–24.2 | 2p23-pter | 2p24.3 | 2q12–14.1,2q32–33 |

| 2p24.2–2p24.1 | 2p22-pter | ||

| 2p24 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 2p24.3–24.2 | 2p22-pter | 2pter, 2p23.1 | 2p13–15,2q13–14,2q22–24,2q32–33 |

| 2p24.3–24.2 | 2pter | 2pter | 2q12–13 |

| 2p24.3–24.2 | 2p13,2q14–24,2q32–33 | ||

| 2p25.2–25.1 | 2p23-pter | 2pter-2p24 | 2q11.2–14.2 |

| 2p24.3–25.1 | 2p23–25 | 2p25.1 | |

| 2p25.1 | 2p22-pter | 2p24 | 2p11.2,2p13–21,2q11.2–37 |

| 2p24.3–24.2 | 2p24-pter | 2pter | 2p13–2q14,2q36 |

| 2p22.3 | 2p22.3–23 | 2p23.2 | 2p13–14, 2q22–24,2q31–33,2q35–36 |

| 2p23 | 2p22-pter | 2p23.2 | 2q22–24,2q32.3–33 |

| 2p24.3–24.2 | 2p23–25.2 | 2p24.3 | none |

| 2p24.3-24.2 | 2p16-pter | 2q22–24 | |

| no | no | no | 2q11.2,2q13–14,2q21.3–34 |

| no | no | no | 2p12–16,2q22–24,2q32 |

| no | 2pter, 2p23 | 2pter, 2p23.2 | 2p14–15,2q12–13,2q36–37 |

| 2p23 | 2p23.2 | 2q32–33 | |

F, female; M, male; DOD, disease-associated death; NED, no evidence of disease; PT, primary tumor.

Age in months (m) or years (y).

Gain.

FISH

The status of MYCN, ALK, 2pter, and/or D2Z in the various cell lines and one primary tumor sample was investigated by double-color FISH on interphase nuclei and/or metaphase spreads. The bacterial artificial chromosome clones RP11–355H10, RP11–1299G23, 08–103-1, and RP11–328L16 were purchased from Dr. M. Rocchi (Resources for Molecular Cytogenetics, University of Bari, Italy), and D2Z was obtained from Qbiogene (Heidelberg, Germany). Detection of digoxigenin- or biotin-labeled hybridized probes was visualized with two antibody steps as already described using mouse anti-biotin and sheep anti-dig fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated primary antibodies and rabbit anti-sheep fluorescein isothiocyanate and rabbit anti-mouse tetramethylrhodamine B isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibodies (DAKO, Denmark).42 Moreover, we performed FISH with the indicated probes on normal metaphase spreads to designate their chromosomal loci on chromosomes with 400 to 500 banding resolutions.

CGH

To determine the genomic status of chromosome 2, we performed CGH experiments as described previously.43 DNA extraction was performed according standard protocols. Digoxigenin- (tumor DNA) and biotin-labeled (reference DNA) hybridized DNA were detected as described for FISH.

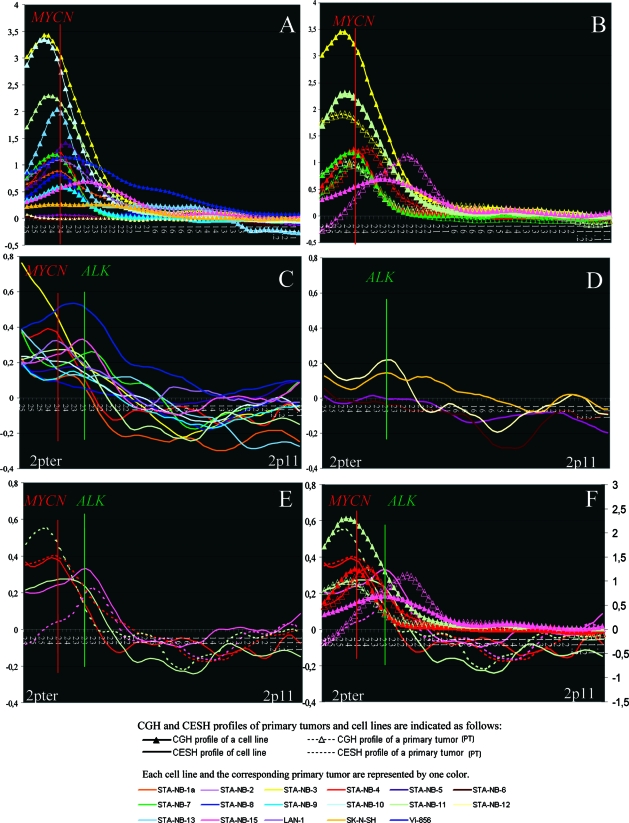

CGH profiles were calculated through the ISIS software developed for DNA copy number evaluation (MetaSystems Hard & Software Gmbh, Altlussheim, Germany). Amplifications or gains were scored if the average green to red ratio value was above a +3δ threshold level. Chromosomal regions showing ratio values below −3δ were interpreted as losses. To determine the level of DNA amplification in NB cell lines, we imported the normalized CGH data into the Excel spreadsheet (see Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

A–F: The 2p loci (from 2pter to 2p11) and the transformed fluorescence ratios are displayed on the x and y axis, respectively. Each curve represents the global genomic pattern or expression profile for 2p of one test sample. A and B: 2p CGH profiles of all 17 NB cell lines with and without MYCN amplification (A) and of five MYCN amplified corresponding primary NB tumors (B). C–E: 2p CESH profiles of 13 MYCN amplified NB cell lines (C), four non-MYCN amplified NB cell lines (D), and three corresponding MYCN amplified primary tumors (E). F: Summary of CGH and CESH 2p profiles of primary tumors and corresponding cell lines. Transformed normalized CESH and CGH ratios are displayed on the left and right x axis, respectively.

RNA Extraction

Total RNA was isolated by phenol-chloroform extraction (Trizol, Invitrogen, Life Technologies, CA) or by using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, GmbH, Hilden, Germany). DNase treatment was performed using either RNase-free DNase I (Ambion, Austin, TX) after Trizol RNA extraction or RNase-free DNase Set (Qiagen GmbH) during RNA isolation step. RNA quality and integrity was controlled by agarose gel electrophoresis (1%).

CESH

The CESH technique was performed mainly as described.28 2.5 to 5 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed by the use of anchored oligo(dT) primer (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, UK) and M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Life Technologies). cDNA was amplified by DOP-PCR (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturers recommendations. The amplified cDNA products of test samples were labeled with Spectrum Green-dUTP (Vysis, Invitrogen) or dig-11-dUTP (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), and reference cDNA with Alexa Fluor 568–5-dUTP (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) or bio-16-dUTP (Roche Diagnostics). The nick translation procedure was optimized to obtain fragments 200 to 600 bp long. Differentially labeled test and control probes were cohybridized in the presence of Cot-1 DNA (Roche Diagnostics) to normal metaphase spreads for 24 to 48 hours. Detection of hybridized dig- or bio-dUTP cDNAs was visualized as for FISH. Counterstaining was performed by applying mounting medium Vectashield with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Digitized images were acquired with a fluorescence microscope (Axioplan 2, Zeiss, Germany) equipped with an Imac CCD S30 camera. For each metaphase all three fluorochrome images were taken by using the appropriate fluorescence filter sets. Image processing was performed using ISIS CGH software with slight modifications (MetaSystems Hard & Software Gmbh, Altlussheim, Germany). Chromosomes were identified by using the banding pattern of 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole-stained chromosomes. Spectrum Green or fluorescein isothiocyanate and Alexa Fluor or tetramethylrhodamine B isothiocyanate (tumor and normal cDNA, respectively) fluorescence intensities were measured for each defined locus. For each sample, the mean fluorescence ratios were obtained from at least eight metaphases. Mean fluorescence ratios exceeding +3δ were indicative of overexpression and below −3δ of low or absent expression of the respective chromosomal region of the test sample. Self-self hybridization assay pairing differentially labeled cDNA from a single donor did not show differential expression using these limits (data not shown). To compare the data of different CESH experiments, average profiles were calculated through the ISIS software using intern symmetric ratio values, according to the formula: RN = R − 1 for R ≥ 1 and RN = 1 − 1/R for r < 1 (R = direct ratio values, RN = normalized ratio values). The obtained values were termed transformed ratio values.

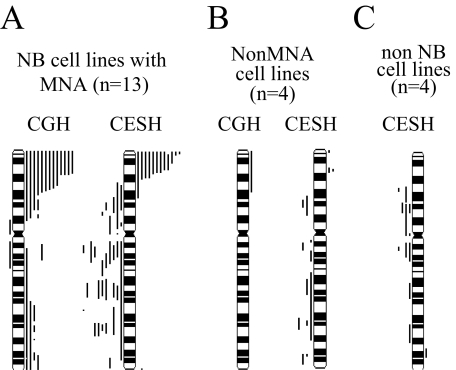

CESH Data Presentation

The software distinguished 163 chromosomal regions for whole chromosome 2, 64 chromosomal regions for the short, and 99 regions for the long arm. For each defined locus, a mean normalized value (ratio between NB cDNA versus leukocyte cDNA) was obtained. In a first step we presented the over- and underexpressed 2p regions on an ideogram similarly to the widely used CGH ideograms showing gained/amplified and lost chromosomal regions, using ±3δ as threshold limits (see Figure 1). In a second step, we imported the transformed ratio values into the spreadsheet to visualize the differential expression levels obtained from the various samples (see Figures 2 and 5).

Figure 1.

A and B: Summary of CGH and CESH results on 2p. A: CGH results of 13 NB cell lines with MYCN amplification (left) and the corresponding 2p expression profiles (right). B: Four NB cell lines without MYCN amplification (left) and corresponding 2p expression profiles (right). C: Summary of CESH results in four non-NB cell lines: Ewing’s tumor, Wilms’ tumor, osteosarcoma, and breast carcinoma cell lines. Bars on the right side of the ideogram represent significant gained or overexpressed regions (normalized ratio values >3δ). Bars on the left side of the ideogram represent significant under-represented or underexpressed chromosomal regions (normalized ratio values <−3δ).

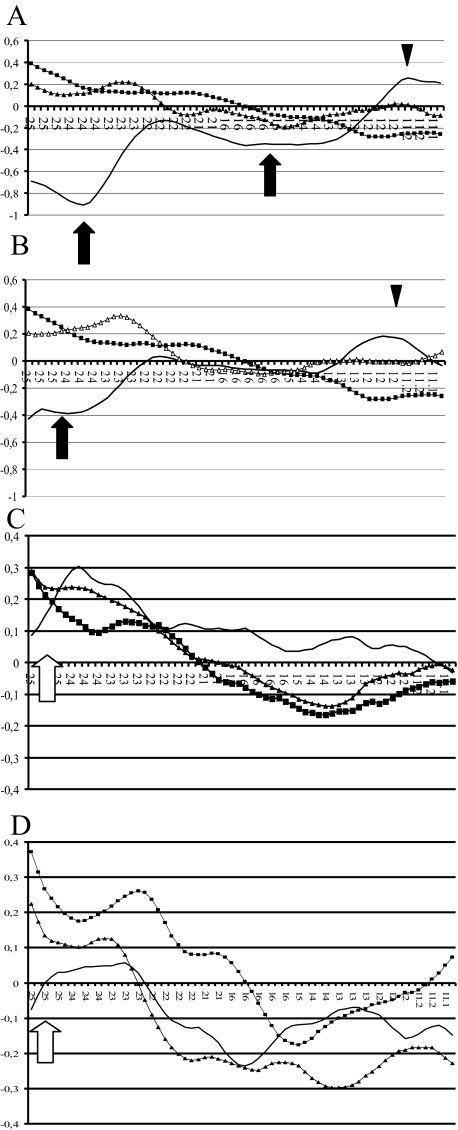

Figure 5.

2p CESH profiles pairing NB cell lines. On the x axes are displayed the 2p loci (from 2pter to 2p11) and on the y axes the transformed fluorescence ratios. A: ▪, STA-NB-13 versus leukocytes; ▴, STA-NB-12 versus leukocytes; —, STA-NB-12 versus STA-NB-13. B: ▪, STA-NB-13 versus leukocytes; ▴, STA-NB-15 versus leukocytes; —, STA-NB-15 versus STA-NB-13. C: ▪, STA-NB-9 versus leukocytes; ▴, STA-NB-10 versus leukocytes; —, STA-NB-10 versus STA-NB-9. D: ▪, STA-NB-7 versus leukocytes; ▴, STA-NB-1.1 versus leukocytes; —, STA-NB-1.1 versus STA-NB-7. We used directly labeled (Spectrum Green-dUTP and Alexa Fluor-dUTP) cDNAs in all CESH experiments except two. The CESH experiments pairing the NB cell line STA-NB-13 with STA-NB-12 (A) or STA-NB-15 (B), respectively, were performed with indirectly labeled (bio-16-dUTP and dig-11 dUTP) cDNAs (A and B).

Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RQ-PCR)

To validate CESH data, we quantified MYCN and ALK expression levels of NB cell lines by RQ-PCR. Singleplex PCR reactions were prepared in a total volume of 25 μl containing 6 μl of cDNA with 100 ng of deoxynucleotide triphosphate. Additionally, 12.5 μl of TaqMan Universal Master Mix (2X concentration, including ROX-reference dye; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), primers and hydrolysis probe (as indicated in Table 2) were added to the PCR reactions. Amplification was performed for a total of 50 cycles using the ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detector System (Applied Biosystems). After an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 10 minutes, each cycle consisted of denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds and annealing and primer extension at 60°C for 60 seconds. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate, and appropriate negative controls were included in each assay. Strict precautions were undertaken to prevent contamination of PCR reactions with exogenous products. Moreover, a digestion step with uracil-DNA-glycosylase was performed to eliminate any potential contaminating PCR product. To assess differences in the extent of RNA degradation and variations in the efficiency of RNA extraction and reverse transcription, an endogenous sequence (β2 microglobulin) was quantified in parallel by real-time PCR.

Table 2.

Primer and Probe Combinations for RQ-PCR Detection of the Targeted Genes

| Target | Amplicon length | Oligonucleotide sequences | Concentration (nmol/L) | Nucleotide position | GenBank Acc. No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MYCN | 144 bp | F: 5′-ACCACAAGGCCCTCAGTACCT-3′ (exon2) | 900 | 2368–2388 | M13241 |

| (RNA)1 | P: 5′-ACTGTGGAGAAGCGGCGTTCCTCCT-3′ (exon3) | 200 | 5095–5119 | ||

| R: 5′-GTGGTGACAGCCTTGGTGTTG-3′ (exon3) | 900 | 5121–5140 | |||

| ALK | 164 bp | F: 5′-ATGACCGACTACAACCCCAACTAC-3′ | 900 | 4176–4199 | U62540 |

| (RNA) | P: 5′-TGGCAAGACCTCCTCCATCAGTG-3′ | 200 | 4208–4230 | ||

| R: 5′-CTTGGGTCGTTGGGGATTC-3′ | 900 | 4321–4339 | |||

| B2MG | 82 bp | F: 5′-TGAGTATGCCTGCCGTGTGA-3′ (exon2) | 300 | 343–362 | M17987 |

| (RNA)2 | P: 5′-CCATGTGACTTTGTCACAGCCCAAGATAGTT-3′ (exon2) | 200 | 364–394 | ||

| R: 5′-TGATGCTGCTTACATGTCTCGAT-3′ (exon3) | 300 | 1018–1040 |

F, forward primer; R, reverse primer; P, probe

MYCN RNA primers span two exons and an intermediate intron of 2628 bp in length.

B2MG RNA primers span two exons and an intermediate intron of 616 bp in length.

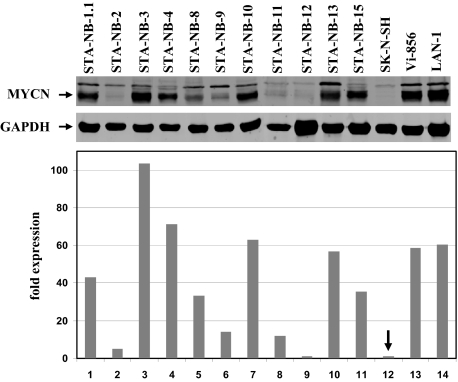

Western Blot Analyses

MYCN protein expression from whole-cell extracts was assessed by Western blot analysis according to the manufacture’s instructions (LI-COR, Biosciences). Visualization and quantification of the protein extracts were done using the Odyssey infrared imaging system. The primary antibodies used were mouse monoclonal anti-N-MYC (NCM II 100, ab16898, Abcam) and anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Santa Cruz). Secondary antibodies were purchased from the company.

Statistical Analysis

The Spearman correlation test was used to assess the correlation between RQ-PCR and CESH data. Linear regression analysis was used to analyze the correlation between the normalized CESH and CGH ratios, and unadjusted P values were calculated for each region. Because of the high number of multiple comparisons (a total of 1196 regions) a high number of false significant results were expected. The multivariate permutation method was used to control the type I error rate at 5%. The reference distribution of the smallest P value was obtained by randomization of the sample labels in the DNA copy number data set and was used to calculate P values that were adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Results

CGH Results of NB Cell Lines and Corresponding Primary Tumors

The CGH results from 17 NB cell lines focusing on chromosome 2 are summarized in Table 1 and Figures 1 and 2, A and B. All MYCN-amplified (MNA) cell lines (n = 13) displayed fluorescence levels above +3δ at 2p23–25 (Figure 1A, left). Gain of 2q material was found in four cell lines, and loss of 2p12–2q12 sequences was observed only in one cell line (STA-NB-13). Gain of 2p material was found in one of four non-MYCN-amplified (non-MNA) NB cell lines (SK-N-SH) (Figure 1B, left).

A detailed presentation of the positions and the heights of the CGH peaks obtained in the 13 MNA NB cell lines are given in Figure 2A. A simple amplification pattern restricted to 2p24 can be noted for eight of 13 NB cell lines. Three other cell lines exhibited a simple amplification pattern at 2p25.1, and two cell lines (STA-NB-15 and Vi-856) showed a more complex amplification pattern encompassing regions proximal to the MYCN locus (Figure 2A).

To confirm that the 2p CGH profiles of the cell lines reflect the genomic status of the primary tumors and are not derived from an atypical subclone arising during cell culture condition, we further investigated the 2p CGH pattern of five corresponding primary tumors. All five tumors displayed CGH peaks similar to those obtained in the corresponding cell lines, as illustrated in Figure 2B. CGH peaks centered near or at the MYCN locus were observed in only two tumors. Both corresponding cell lines STA-NB-4 and STA-NB-7 exhibited, similar to the primary tumors, a CGH peak at 2p24 (a slight shift can be noted for the corresponding primary tumor of the cell line STA-NB-4). CGH peaks distal to MYCN were observed only in these tumors where the corresponding cell lines STA-NB-3 and STA-NB-11 also displayed this pattern. The lower CGH peaks observed in the primary tumors compared to those from the corresponding cell lines are assumed to result from contamination with normal cells. Finally, the primary tumor of STA-NB-15 displayed, similar to the corresponding cell line, a CGH peak proximal to MYCN. However, the CGH peak of the primary tumor was found to be situated at 2p22.3 and not at 2p23.3. Moreover, the 2p profiles were divergent at the 2pter regions. Conventional cytogenetic and FISH analyses using ALK, MYCN and 2pter as probes demonstrated that all cells from the cell line STA-NB-15 displayed two hsrs formed of amplified MYCN and ALK sequences. One hsr was situated at 2p23, and the insertion of this aberration resulted in deletion of 2p25-pter. The other hsr was located at 20q. Moreover, the majority of the cells exhibited a gained derivative chromosome 1 harboring 2p24-pter material (der(1)t(1;2)(p13;p24)). Thus, these cells did not show loss of 2pter material. In contrast, the primary tumor probably displayed loss of 2pter material, as negative fluorescence ratio values were obtained for this region by CGH (Figure 2, B and F). However, the cells exhibited identical hsrs as the corresponding cell line. These findings revealed that a subclone emerged during cell culturing, displaying, besides both hsrs, gain of a derivative chromosome 1, harboring 2p24–25 material. It remains to be determined whether the different 2pter copy number has an influence on the CGH peak locus. In summary, three of five primary tumors displayed totally overlapping peaks, and two tumors had a slightly shifted CGH peak when compared with the corresponding cell line.

CESH Results Obtained in NB Cell Lines and Corresponding Primary Tumors

Figure 1 illustrates the relative over- and underexpressed regions of chromosome 2 in MYCN-amplified (Figure 1A, right side) and nonamplified NB cell lines (Figure 1B, right side). Moreover, the differentially expressed regions for each cell line are described in Table 1. Significantly overexpressed regions at 2p were found in all NB cell lines with MNA, except one, and in two of four non-MNA NB cell lines. Eleven of 13 and 10 of 13 of the cell lines with MNA showed relative overexpression at 2pter and 2p24, respectively. None of the non-MNA cells displayed overexpression at 2p24; however, overexpression was observed at 2p25 (one of four) and at 2p23 (two of four).

None of the NB cell lines displayed a relative overexpression at 2q, except one at 2qter. On the contrary, in the case of cell lines with MNA, underexpressed regions were observed at 2q12–13 and 2q22–24 in seven of 13 and 2q32.3–33 in six of 13 (Figure 1A). The same underexpressed regions with altered frequency were found in non-MNA cells. To visualize the relative expression levels obtained in NB samples at defined 2p loci, we performed detailed CESH analyses (Figure 2).

Detailed Analysis of 2p CESH Results Obtained in MYCN-Amplified NB Cell Lines and Corresponding Primary Tumors

A summary of the 2p CESH profiles in MNA NB cell lines is depicted in Figure 2C. Although the NB cell lines displayed MYCN amplification, only two cell lines (STA-NB-4 and LAN-1) displayed their highest transcript levels near or at 2p24.3, the germ line position of MYCN. Altogether, the 2p expression profiles were quite complex in most instances; however, we tried to categorize the most frequent patterns. We observed four different expression patterns for the 2pter to 2p23 chromosomal region: 1) enhanced expression peak at diverse chromosomal loci, eg, 2pter (STA-NB-3 and -13), 2p24.3 (eg, LAN-1), and 2p23.3–2p23.2 (Vi-856, STA-NB-15); 2) CESH profiles exhibiting two expression peaks (eg, STA-NB-7 showed an expression peak at 2pter and 2p23.1); 3) CESH profiles showing a plateau of expression at 2p23–25 (eg, STA-NB-5); and 4) absence of significant expression at the MYCN locus (STA-NB-1.1, STA-NB-8, and STA-NB-9). The overexpressed regions and positions of the CESH peaks are summarized in Table 1.

2p CESH Results Obtained in NB Cell Lines Without MYCN Amplification

Only two of four NB cell lines without MNA (SK-N-SH and STA-NB-12) reached significant 2p transcript levels at 2pter (n = 1) and 2p23 (n = 2), respectively (Figures 1B and 2D; Table 1).

2p CESH Profiles of Primary Tumors and Corresponding Cell Lines

The CESH profiles of three primary tumors all displayed a CESH peak, one centered at the MYCN locus, one distal, and one proximal to the MYCN locus, thus demonstrating the existence of an individual 2p expression pattern (Figure 2E). This expression pattern is retained in two of three corresponding cell lines, indicating that the 2p expression profile of the primary tumors matched with the expression profile of the corresponding cell line. The CESH profiles of the primary tumor and the corresponding cell line STA-NB-11 did not match perfectly, as the tumor showed a distinct expression peak at 2p25, whereas the cell line exhibited a relatively flat curve with an expression maximum at 2p24. Thus, we can deduce that the distinctly enhanced expression peaks observed in two cell lines might mirror the situation in vivo.

2p CESH Results Obtained in Cell Lines Other Than NB

None of the non-neuroblastoma cell lines displayed significantly overexpressed 2p transcript levels using ±3δ SD limits. In contrast, the chromosomal region 2p13–14 was underexpressed in STA-OS-2, STA-WT-3, and ZR-75–1. Significantly overexpressed regions at 2q (2q21.3 and 2q35–36) were noted only in STA-ET-6. Moreover, STA-ET-6, STA-WT-3, and ZR-75–1 displayed underexpression at the chromosomal region 2q13 (Figure 1C).

FISH

Gene amplifications often result in an increased expression level of the corresponding amplified gene. Therefore, we checked the genomic status of the ALK gene (germ line position 2p23.2) in all NB cell lines. FISH results are presented in Table 1. Interestingly, only the two cell lines with highest transcript levels at 2p23.2–23.3, STA-NB-15 and Vi-856, showed coamplification of the ALK gene. Two other cell lines, STA-NB-1 and SK-N-SH, had gain of the ALK gene (three ALK copies in a diploid cell with only two long arms of chromosome 2). The remaining 13 NB cell lines displayed normal ALK copy numbers in relation to the ploidy level and chromosome 2q copy number, as we found two, three, and four ALK copies in di-, tri-, and tetraploid cells, respectively. Moreover, we tested whether the corresponding primary tumor of the cell line STA-NB-15 displayed ALK amplification. FISH confirmed the presence of ALK-amplified sequences. We assume that all other primary tumors do not harbor ALK amplification, as their CGH profiles did not display a peak at the ALK locus. To independently confirm the results obtained with CESH, we used three different approaches.

Validation of CESH Data by Real-Time Quantitative PCR

The first approach to validate our results was to quantify the MYCN and ALK expression levels by the use of RQ-PCR. Figure 3 illustrates the correlation between RQ-PCR expression levels of MYCN and ALK and the CESH fluorescence ratios at 2p24.3 and 2p23.2. All four NB cell lines lacking MYCN amplification displayed low MYCN expression levels by RQ-PCR and low CESH ratios at 2p24 in CESH. (It should be noted that smaller RQ-PCR values indicate relatively high expression levels.) STA-NB-12 reached a higher expression level (0.113) than all other non-MNA cell lines, presumably because of the CESH peak at 2p23 (Figure 2D). More or less uniform RQ-PCR values were observed within the MNA group. In CESH, the majority of the MNA samples exhibited similar values as well. Only three cell lines (STA-NB-3, -4 and Vi-856) displayed high CESH values, and in one case (Vi-856) the enhanced values resulted probably from the expression peak situated proximal to the MYCN locus. Thus, it is absolutely necessary to look at the curve of the expression profile, to interpret a value at a defined locus. Finally, three cell lines did not reach significant expression levels in CESH, although RQ-PCR revealed high to medium MYCN transcript levels. Whereas the highest relative ALK expression levels were observed in cell lines displaying ALK amplification, the differential expression level was marginal for one cell line in comparison to non-ALK-amplified cell lines.

Figure 3.

Correlation between RQ-PCR with CESH data. x axis, transformed fluorescence ratios (CESH data); y axis, normalized Ct values (RQ-PCR data). ♦, MNA NB cell lines; ⋄, non-MNA NB cell lines; ▴, coamplified ALK NB cell lines; ▪, non-NB cell lines.

In summary, RQ-PCR confirmed the CESH data, as for MYCN and ALK the relative expression levels reached good correlation coefficients for both methods (P < 0.0371 and P < 0.0243, respectively). An even higher correlation coefficient was observed including CESH and RQ-PCR data for non-NB cell lines (P < 0.0025 and P < 0.0054, respectively).

Western Blot Analysis

We investigated the MYCN protein expression levels in a number of cell lines (Figure 4). As expected, all three non-MNA cell lines expressed very low MYCN protein levels. Moreover, lower protein expression levels in comparison to other MNA cell lines were observed in those cell lines displaying no significant expression levels at 2p24 in CESH. Interestingly, STA-NB-3 and STA-NB-4 displayed the highest levels, in accordance with the CESH data. Only one cell line showed low protein expression, although displaying MYCN transcript levels in RQ-PCR and CESH.

Figure 4.

Immunoblot of expression of MYCN and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in the NB cell lines and protein quantification. All values normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase are presented as fold expression in relation to SK-N-SH (arrow).

Validation of CESH Data by Using NB Cell Lines as Reference

The NB cell lines displayed differential expression levels at 2p23-pter using cDNA from leukocytes as a reference. Focusing on the 2pter region, for instance, we observed three distinct expression levels (Figure 2C). To prove that these differential expression levels can be reproduced, we performed further CESH assays using NB cell lines as reference instead of leukocytes. This is important because terminal chromosomal regions are not included in CGH analyses. Chromosome 2p expression profiles of these experiments are presented in Table 3 and Figure 5. The 2p CESH profiles using the NB cell line STA-NB-13 as reference showed 1) the appearance of significant underexpressed regions at 2p23-pter and 2p13–21 in the non-MNA cell line STA-NB-12 (used as test sample) (Figure 5A, black arrows) as well as underexpressed regions at 2p23.3-pter in STA-NB-15 (used as test sample) (Figure 5B, black arrow) and 2) the appearance of significant overexpressed regions. STA-NB-12 and STA-NB-15 cell lines did not show significant transcript levels at 2p11 and 2p12, respectively, when paired with cDNA from leukocytes. However, when cDNA from STA-NB-13 was used as a reference (the cell line displayed loss or under-representation of 2p12–2q12 chromosomal material, Table 1), both cell lines reached significant transcript levels at these regions (black arrowheads, Figure 5, A and B). The disappearance of significant overexpressed regions was also observed. Pairing NB cell lines exhibiting similar 2pter expression levels (STA-NB-1.1, -7, -9, and -10) resulted in loss of differential expression of this region (Figure 5, C and D, white arrow), indicating that the 2pter expression levels observed in CESH experiments using cDNA from leukocytes are indeed specific. Remarkably, STA-NB-10 (used as test sample) still showed significant transcript levels at 2p22-p25.1 when paired with STA-NB-9 (used as reference sample).

Table 3.

Chromosome 2p Expression Profiles Pairing Various NB Cell Lines

| Reference sample | Test sample | Overexpressed regions (CESH ratio>+3δ) | Underexpressed regions (CESH ratio<−3δ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| STA-NB-13 | STA-NB-12 | 2p11,2q13–21.1 | 2p13–21,2p23-pter,2q34–36 |

| STA-NB-13 | STA-NB-15 | 2p11.2–12 | 2p23.3-pter |

| STA-NB-9 | STA-NB-10 | 2p22.3–25.1 | |

| STA-NB-7 | STA-NB-1 | 2p16,2q11–12,2q31,2q33 |

In fact, the hybridization pattern obtained in the cell line STA-NB-12 paired with leukocytes looks, at first glance, quite divergent from the expression profile when paired with the cell line STA-NB-13 (Figure 5A). As already mentioned, STA-NB-12 displays higher CESH values at 2p24, most likely due to the enhanced transcription activity at 2p23. Moreover, comparing the hybridization pattern of the three experiments, we observed that the labeling was not optimal in the assay pairing STA-NB-13 with leukocytes. The RQ-PCR and Western blot data support the interpretation that STA-NB-13 should display a higher value. Finally, the use of two antibody steps in the CESH experiment of pairing the cell lines dramatically increased their differential expression levels at 2p24. In summary, the results of these experiments, pairing various NB cell lines, confirmed the transcript levels at 2p obtained from CESH assays using leukocyte cDNA as a reference (Figure 2, C and D), indicating that the 2pter expression levels have to be included in CESH analyses.

Correlation of CGH with CESH Data

We compared the CGH and CESH peaks to identify whether they overlapped. We indicated the loci in bold where the CGH and CESH peaks matched (Table 1). Only four of 17 NB cell lines and one primary tumor displayed a CGH and CESH peak at the same locus. Figure 2F illustrates the CGH and CESH profiles of three primary tumors and their corresponding cell lines. All three tumors displayed a distinct expression peak, one peak centered at the MYCN locus (red curves), one distal (green curves), and one proximal to the MYCN locus (pink curves). However, the CGH peaks of the primary tumors, from which the cell lines STA-NB-4 and STA-NB-15 were generated, showed a slight shift from the other CGH and CESH curves.

Linear regression analysis, performed exclusively on cell lines, revealed a positive correlation between CESH and CGH data in all 2p regions, even though this correlation did not reach statistical significance (adjusted P value >5%). One may argue that, due to the small sample size and the large number of multiple comparisons, the power to find significant correlations is limited. On the other hand the lack of significant correlation may indicate the presence of non-equally transcribed genes composing the amplicon.

Discussion

Interestingly, only two of 13 MNA cell lines (STA-NB-4 and LAN-1) displayed a CESH peak at 2p24, the germ line position of MYCN. The other cell lines with MNA showed either distinct expression peaks proximal or distal to the MYCN locus, or an expression plateau in this region. In contrast, the CGH peaks were clustered frequently at 2p24 and less frequently at 2p25.1, and two cell lines displayed complex CGH profiles. Thus, we have evidence that not all genes constituting the MYCN amplicon are equally transcribed and that genes other than MYCN reach even higher transcript levels in some cases.

The prognostic impact of MNA, which is associated with poor prognosis, has been valid for more than two decades. In contrast, controversial findings have been reported for the prognostic value of MYCN expression and/or protein level.44,45,46,47,48 Tumors with amplified MYCN sequences usually show increased MYCN transcript or protein levels. However, some MNA tumors and cell lines reported and in this study were shown to express low MYCN transcript and/or protein levels.15,26,49,50,51 We cannot exclude that the MYCN expression levels in some MNA tumors are directly attributed to the corresponding copy number. In fact, the terminus MNA is usually applied to tumors harboring at least four times the reference copy on the same chromosome.52Thus, tumors displaying low (10 to 20) or high (>100) MYCN copy number are equally considered. Moreover, the assessment of the correct copy number in cells measured by interphase FISH may be in some instances difficult, due to variable copy numbers. In our study all NB cell lines reaching not significant expression levels at 2p24 in CESH (STA-NB-1.1, -8, -9, Figure 2C) harbored a low amplification rate as indicated by CGH (Figure 2A) and lower MYCN protein expression levels in comparison to mostly all other MNA cell lines. Conversely, elevated MYCN expression levels were observed also in NB tumors lacking MYCN amplification and were found to be associated with favorable outcome.48 This phenomenon was explained by experiments showing that forced MYCN expression reduced the viability of non-MNA NB cells by inducing apoptosis and enhancing favorable NB gene expression. Interestingly, comparing the MYCN protein levels of non-MNA cell lines, the highest level was reached in the cell line derived from a patient with favorable outcome. Therefore, the transcription regulator MYCN may have distinct roles in different subsets of NB, driving either cellular proliferation or apoptosis. The question remains as to whether coamplified or gained genes have regulatory effects on the MYCN transcript or protein levels.

Only a few studies performed a detailed analysis of the 2p amplicon constitution using high resolution array CGH.4,5,14,53 A number of highly coamplified regions that were discontinuous regarding the MYCN locus and located at varying distances from MYCN were described, demonstrating the unique constitution of the MYCN amplicon.4,5,14,53 Interestingly, only one group of researchers found high-level amplification of two genes (SNTG2 and TPO) situated at 936 kb and 1.4 Mb, respectively, from 2pter, occurring in one of 10 MNA samples.5 In contrast, array expression studies from two independent groups reported the frequent occurrence of elevated expression levels of the genes SH3YL1,26 ACP1,49 and RPS726,49 situated at 208 kb, 250 kb, and 3.6 Mb, respectively, from 2pter, thus confirming our data. Finally, RPS7 and SH3YL1 were not only found to be frequently highly expressed in MNA tumors, but elevated expression levels were observed, although less frequently, in non-MNA NB samples.26

The report combining genomic and expression microarray data of the 2p amplicon rarely detected highly expressed genes at 2pter (the coamplified genes in vicinity of 2pter were also found to be overexpressed).5 However, concordant results were observed concerning the regions mostly involved in amplicon formation encompassed 2pter-2p23.1 and the elevated expression of genes other than MYCN in eight of 10 MNA tumors. Interestingly, the expression levels of the coamplified genes were even higher than the MYCN gene itself in seven of 10 cases. ALK amplification was also observed in one of 10 MNA tumors.

Lamant and coworkers54 consistently found ALK transcripts and ALK protein in all primary NB samples investigated. However, the authors did not observe a correlation between prognosis and the level of ALK expression in a cohort of 24 NBs, probably because of missing ALK amplified samples in their study.54 Other groups demonstrated that amplification of the ALK gene leads to overexpression of the ALK protein and to constitutively activated ALK kinase.17,55 The suppression of activated ALK in NB-39-nu ALK amplified cells by RNA interference significantly reduced the phosphorylation of ShcC, mitogen-activated protein kinases, and Akt, inducing rapid apoptosis of the cells.17 Recent data revealed that in every cohort at least one of 10 MNA samples displayed coamplification of the ALK gene.5,14,56 Moreover, ALK amplification was identified in samples derived from patients with poor prognosis,17,55 which is in line with our data (Table 1).

Two non-MNA NB cell lines, SK-N-SH and STA-NB-12, reached significant expression levels at 2pter and/or 2p23. SK-N-SH displays gain of the ALK gene; thus it is likely that this aberration resulted in an elevated 2p23 expression level. STA-NB-12 presents no gain of the ALK gene, but it remains to be determined whether gained genes other than ALK, below the resolution of the CGH technique, are responsible for the 2p expression pattern. In fact, gained 2p regions were frequently found in non-MNA tumors by SNP array analysis.56 On the other hand, enhanced expression of a gene that is independent of copy number could also occur. Interestingly, SLC30A3, situated at 2 Mb distal from the ALK gene, was observed to be highly expressed, although none was amplified or gained, in two of 10 MNA tumors.5

We are aware that it is unacceptable to draw conclusions on the prognostic impact of the expression patterns obtained from cell lines. However, we have shown that the CESH peaks of cell lines substantially overlapped with those obtained in primary tumors. Therefore, we assume that enhanced expression peaks obtained from cell lines can be extrapolated to the in vivo situation. Considering the CESH expression peaks and clinical data, we observe that all samples with expression peaks at 2p23.2 derived from patients with unfavorable outcome.

The combination of CGH and CESH data presented for the first time in this form enabled us to visualize chromosomal regions with increased transcription activity, including the 2pter region; to determine the expression levels of different regions; and to speculate whether CESH peaks at 2p23.2–23.3 may have prognostic implications in high-risk neuroblastoma patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Renate Panzer, Stephan Grünert, and Heinrich Kovar for helpful discussions, and Marion Zavadil for proofreading.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Peter F. Ambros, Ph.D., Assoc. Prof., Children’s Cancer Research Institute, St. Anna Kinderkrebsforschung, Kinderspitalgasse 6, A-1090 Vienna, Austria. E-mail: peter.ambros@ccri.at.

Supported by St. Anna Kinderkrebsforschung.

References

- Seeger RC, Brodeur GM, Sather H, Dalton A, Siegel SE, Wong KY, Hammond D. Association of multiple copies of the N-myc oncogene with rapid progression of neuroblastomas. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1111–1116. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198510313131802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur GM, Seeger RC, Schwab M, Varmus HE, Bishop JM. Amplification of N-myc in untreated human neuroblastomas correlates with advanced disease stage. Science. 1984;224:1121–1124. doi: 10.1126/science.6719137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama K, Kanda N, Yamada M, Tadokoro K, Matsunaga T, Nishi Y. Megabase-scale analysis of the origin of N-myc amplicons in human neuroblastomas. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:187–193. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beheshti B, Braude I, Marrano P, Thorner P, Zielenska M, Squire JA. Chromosomal localization of DNA amplifications in neuroblastoma tumors using cDNA microarray comparative genomic hybridization. Neoplasia. 2003;5:53–62. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(03)80017-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lastowska M, Viprey V, Santibanez-Koref M, Wappler I, Peters H, Cullinane C, Roberts P, Hall AG, Tweddle DA, Pearson ADJ, Lewis I, Burchill SA, Jackson MS. Identification of candidate genes involved in neuroblastoma progression by combining genomic and expression microarrays with survival data. Oncogene. 2007;26:7432–7444. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Preter K, Speleman F, Combaret V, Lunec J, Board J, Pearson A, De Paepe A, Van Roy N, Laureys G, Vandesompele J. No evidence for correlation of DDX1 gene amplification with improved survival probability in patients with MYCN-amplified neuroblastomas. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3167–3170. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George RE, Kenyon R, McGuckin AG, Kohl N, Kogner P, Christiansen H, Pearson ADJ, Lunec J. Analysis of candidate gene co-amplification with MYCN in neuroblastoma. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:2037–2042. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko S, Ohira M, Nakamura Y, Isogai E, Nakagawara A, Kaneko M. Relationship of DDX1 and NAG gene amplification/overexpression to the prognosis of patients with MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2007;133:185–192. doi: 10.1007/s00432-006-0156-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire JA, Thorner PS, Weitzman S, Maggi JD, Dirks P, Doyle J, Hale M, Godbout R. Co-amplification of MYCN and a DEAD box gene (DDX1) in primary neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 1995;10:1417–1422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber A, Imisch P, Bergmann E, Christiansen H. Coamplification of DDX1 correlates with an improved survival probability in children with MYCN-amplified human neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2681–2690. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasorella A, Boldrini R, Dominici C, Donfrancesco A, Yokota Y, Inserra A, Iavarone A. Id2 is critical for cellular proliferation and is the oncogenic effector of N-myc in human neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandesompele J, Edsjo A, De Preter K, Axelson H, Speleman F, Pahlman S. ID2 expression in neuroblastoma does not correlate to MYCN levels and lacks prognostic value. Oncogene. 2003;22:456–460. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer S, Yu AL, Omura-Minamisawa M, Batova A, Diccianni MB. Expression profiles and clinical relationships of ID2. CDKN1B, and CDKN2A in primary neuroblastoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2004;41:297–308. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen QR, Bilke S, Wei JS, Whiteford CC, Cenacchi N, Krasnoselsky AL, Greer BT, Son CG, Westermann F, Berthold F, Schwab M, Catchpoole D, Khan J. cDNA array-CGH profiling identifies genomic alterations specific to stage and MYCN-amplification in neuroblastoma. BMC Genomics. 2004;5:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-5-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Preter K, Pattyn F, Berx G, Strumane K, Menten B, Van Roy F, De Paepe A, Speleman F, Vandesompele J. Combined subtractive cDNA cloning and array CGH: an efficient approach for identification of overexpressed genes in DNA amplicons. BMC Genomics. 2004;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DK, Board JR, Lu X, Pearson ADJ, Kenyon RM, Lunec J. The neuroblastoma amplified gene. NAG: genomic structure and characterisation of the 73 kb transcript predominantly expressed in neuroblastoma. Gene. 2003;307:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00459-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osajima-Hakomori Y, Miyake I, Ohira M, Nakagawara A, Nakagawa A, Sakai R. Biological role of anaplastic lymphoma kinase in neuroblastoma. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:213–222. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62966-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michels E, Vandesompele J, Hoebeeck J, Menten B, De Preter K, Laureys G, Van Roy N, Speleman F. Genome wide measurement of DNA copy number changes in neuroblastoma: dissecting amplicons and mapping losses, gains and breakpoints. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2006;115:273–282. doi: 10.1159/000095924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosse YP, Greshock J, Weber BL, Maris JM. Measurement and relevance of neuroblastoma DNA copy number changes in the post-genome era. Cancer Lett. 2005;228:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Preter K, Vandesompele J, Heimann P, Yigit N, Beckman S, Schramm A, Eggert A, Stallings R, Benoit Y, Renard M, Paepe A, Laureys G, Pahlman S, Speleman F. Human fetal neuroblast and neuroblastoma transcriptome analysis confirms neuroblast origin and highlights neuroblastoma candidate genes. Genome Biology. 2006;7:R84. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-9-r84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm A, Schulte JH, Klein-Hitpass L, Havers W, Sieverts H, Berwanger B, Christiansen H, Warnat P, Brors B, Eils J, Eils R, Eggert A. Prediction of clinical outcome and biological characterization of neuroblastoma by expression profiling. Oncogene. 2005;24:7902–7912. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte JH, Schramm A, Klein-Hitpass L, Klenk M, Wessels H, Hauffa BP, Eils J, Eils R, Brodeur GM, Schweigerer L, Havers W, Eggert A. Microarray analysis reveals differential gene expression patterns and regulation of single target genes contributing to the opposing phenotype of TrkA- and TrkB-expressing neuroblastomas. Oncogene. 2005;24:165–177. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takita J, Ishii M, Tsutsumi S, Tanaka Y, Kato K, Toyoda Y, Hanada R, Yamamoto K, Hayashi Y, Aburatani H. Gene expression profiling and identification of novel prognostic marker genes in neuroblastoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2004;40:120–132. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei JS, Greer BT, Westermann F, Steinberg SM, Son CG, Chen QR, Whiteford CC, Bilke S, Krasnoselsky AL, Cenacchi N, Catchpoole D, Berthold F, Schwab M, Khan J. Prediction of clinical outcome using gene expression profiling and artificial neural networks for patients with neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6883–6891. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosse YP, Greshock J, Margolin A, Naylor T, Cole K, Khazi D, Hii G, Winter C, Shahzad S, Asziz MU, Biegel JA, Weber BL, Maris JM. High-resolution detection and mapping of genomic DNA alterations in neuroblastoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005;43:390–403. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Diskin S, Rappaport E, Attiyeh E, Mosse Y, Shue D, Seiser E, Jagannathan J, Shusterman S, Bansal M, Khazi D, Winter C, Okawa E, Grant G, Cnaan A, Zhao H, Cheung N-K, Gerald W, London W, Matthay KK, Brodeur GM, Maris JM. Integrative genomics identifies distinct molecular classes of neuroblastoma and shows that multiple genes are targeted by regional alterations in DNA copy number. Cancer Res. 2006;62:6050–6062. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman R, Carey V, Huber W, Irizarry R, Dudoit S. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor. Springer; 2005:1–473. [Google Scholar]

- Lu YJ, Williamson D, Clark J, Wang R, Tiffin N, Skelton L, Gordon T, Williams R, Allan B, Jackman A, Cooper C, Pritchard-Jones K, Shipley J. Comparative expressed sequence hybridization to chromosomes for tumor classification and identification of genomic regions of differential gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9197–9202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161272798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentz M, Plesch A, Stilgenbauer S, Dohner H, Lichter P. Minimal sizes of deletions detected by comparative genomic hybridization. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1998;21:172–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joos S, Scherthan H, Speicher MR, Schlegel J, Cremer T, Lichter P. Detection of amplified DNA sequences by reverse chromosome painting using genomic tumor DNA as probe. Hum Genet. 1993;90:584–589. doi: 10.1007/BF00202475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper J, Rutovitz D, Sudar D, Kallioniemi A, Kallioniemi OP, Waldman FM, Gray JW, Pinkel D. Computer image analysis of comparative genomic hybridization. Cytometry. 1995;19:10–26. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990190104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parente F, Gaudray P, Carle GF, Turc-Carel C. Experimental assessment of the detection limit of genomic amplification by comparative genomic hybridization CGH. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1997;78:65–68. doi: 10.1159/000134632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff M, Gerdes T, Maahr J, Rose H, Bentz M, Dohner H, Lundsteen C. Deletions below 10 megabasepairs are detected in comparative genomic hybridization by standard reference intervals. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1999;25:410–413. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(199908)25:4<410::aid-gcc17>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu YJ, Williamson D, Wang R, Summersgill B, Rodriguez S, Rogers S, Pritchard-Jones K, Campbell C, Shipley J. Expression profiling targeting chromosomes for tumor classification and prediction of clinical behavior. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;38:207–214. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanden Bempt I, Vanhentenrijk V, Drijkoningen M, Wolf-Peeters CD. Comparative expressed sequence hybridization reveals differential gene expression in morphological breast cancer subtypes. J Pathol. 2006;208:486–494. doi: 10.1002/path.1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu YJ, Hing S, Williams R, Pinkerton R, Shipley J, Pritchard-Jones K. Chromosome 1q expression profiling and relapse in Wilms’ tumour. Lancet. 2002;360:385–386. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09596-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros IM, Rumpler S, Luegmayr A, Hattinger CM, Strehl S, Kovar H, Gadner H, Ambros PF. Neuroblastoma cells can actively eliminate supernumerary MYCN gene copies by micronucleus formation: sign of tumour cell revertance? Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:2043–2049. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narath R, Ambros IM, Kowalska A, Bozsaky E, Boukamp P, Ambros PF. Induction of senescence in MYCN amplified neuroblastoma cell lines by hydroxyurea. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006 doi: 10.1002/gcc.20393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattinger CM, Rumpler S, Strehl S, Ambros IM, Zoubek A, Potschger U, Gadner H, Ambros PF. Prognostic impact of deletions at 1p36 and numerical aberrations in Ewing tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1999;24:243–254. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(199903)24:3<243::aid-gcc10>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock C, Kager L, Fink FM, Gadner H, Ambros PF. Chromosomal regions involved in the pathogenesis of osteosarcomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;28:329–336. doi: 10.1002/1098-2264(200007)28:3<329::aid-gcc11>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock C, Ambros IM, Lion T, Zoubek A, Amann G, Gadner H, Ambros PF. Genetic changes of two Wilms tumors with anaplasia and a review of the literature suggesting a marker profile for therapy resistance. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2002;135:128–138. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(01)00647-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock C, Ambros IM, Lion T, Haas OA, Zoubek A, Gadner H, Ambros PF. Detection of numerical and structural chromosome abnormalities in pediatric germ cell tumors by means of interphase cytogenetics. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1994;11:40–50. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870110107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallioniemi OP, Kallioniemi A, Piper J, Isola J, Waldman FM, Gray JW, Pinkel D. Optimizing comparative genomic hybridization for analysis of DNA sequence copy number changes in solid tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1994;10:231–243. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870100403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordow SB, Norris MD, Haber PS, Marshall GM, Haber M. Prognostic significance of MYCN oncogene expression in childhood neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3286–3294. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.10.3286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan HL, Gallie BL, DeBoer G, Haddad G, Ikegaki N, Dimitroulakos J, Yeger H, Ling V. MYCN protein expression as a predictor of neuroblastoma prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:1699–1706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn SL, London WB, Huang D, Katzenstein HM, Salwen HR, Reinhart T, Madafiglio J, Marshall GM, Norris MD, Haber M. MYCN expression is not prognostic of adverse outcome in advanced-stage neuroblastoma with nonamplified MYCN. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3604–3613. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.21.3604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiyama E, Hiyama K, Yokoyama T, Ishii T. Immunohistochemical analysis of N-myc protein expression in neuroblastoma: correlation with prognosis of patients. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26:838–843. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(91)90151-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang XX, Zhao H, Kung B, Kim DY, Hicks SL, Cohn SL, Cheung N-K, Seeger RC, Evans AE, Ikegaki N. The MYCN enigma: significance of MYCN expression in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2826–2833. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alaminos M, Mora J, Cheung N-KV, Smith A, Qin J, Chen L, Gerald WL. Genome-wide analysis of gene expression associated with MYCN in human neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4538–4546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga T, Shirasawa H, Hishiki T, Yoshida H, Kouchi K, Ohtsuka Y, Kawamura K, Etoh T, Ohnuma N. Enhanced expression of N-myc messenger RNA in neuroblastomas found by mass screening. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:3199–3204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitz T, Wei T, Valentine MB, Vanin EF, Grenet J, Valentine VA, Behm FG, Look AT, Lahti JM, Kidd VJ. Caspase 8 is deleted or silenced preferentially in childhood neuroblastomas with amplification of MYCN. Nat Med. 2000;6:529–535. doi: 10.1038/75007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros PF, Ambros IM. Pathology and biology guidelines for resectable and unresectable neuroblastic tumors and bone marrow examination guidelines. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001;37:492–504. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallings RL, Nair P, Maris JM, Catchpoole D, McDermott M, O’Meara A, Breatnach F. High-resolution analysis of chromosomal breakpoints and genomic instability identifies PTPRD as a candidate tumor suppressor gene in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3673–3680. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamant L, Pulford K, Bischof D, Morris SW, Mason DY, Delsol G, Mariame B. Expression of the ALK tyrosine kinase gene in neuroblastoma. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1711–1721. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65042-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake I, Hakomori Y, Shinohara A, Gamou T, Saito M, Iwamatsu A, Sakai R. Activation of anaplastic lymphoma kinase is responsible for hyperphosphorylation of ShcC in neuroblastoma cell lines. Oncogene. 2002;21:5823–5834. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George RE, Attiyeh EF, Li S, Moreau LA, Neuberg D, Li C, Fox EA, Meyerson M, Diller L, Fortina P, Look AT, Maris JM. Genome-wide analysis of neuroblastomas using high-density single nucleotide polymorphism arrays. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]