Summary

A “HFPK3” peptide containing the 23 residues of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) fusion peptide (HFP) plus three non-native C-terminal lysines was studied in dodecylphosphocholine (DPC) micelles with 2D 1H NMR spectroscopy. The HFP is at the N-terminus of the gp41 fusion protein and plays an important role in fusing viral and target cell membranes which is a critical step in viral infection. Unlike HFP, HFPK3 is monomeric in detergent-free buffered aqueous solution which may be a useful property for functional and structural studies. Hα chemical shifts indicated that DPC-associated HFPK3 was predominantly helical from I4 to L12. In addition to the highest-intensity crosspeaks used for the first chemical shift assignment (denoted I), there were additional crosspeaks whose intensities were ~10% of those used for assignment I. A second assignment (II) for residues G5 to L12 as well as a few other residues was derived from these lower-intensity crosspeaks. Relative to the I shifts, the II shifts were different by 0.01–0.23 ppm with the largest differences observed for HN. Comparison of the shifts of DPC-associated HFPK3 with those of detergent-associated HFP and HFP derivatives provided information about peptide structures and locations in micelles.

Keywords: DPC, fusion peptide, HIV, NMR, structural heterogeneity, cryoprobe, SDS

Introduction

The HIV gp41 protein catalyzes fusion between viral and host cell membranes and contains an N-terminal fusion peptide (HFP) of ~20 residues which plays an essential role in fusion [1–3]. Peptides containing the HFP sequence fuse unilamellar lipid vesicles, and there is a good correlation between the mutation/fusion activity relationships of HFP-induced vesicle fusion and gp41-catalyzed membrane fusion [4–10]. The HFP is therefore thought to be a useful model fusion system.

This paper considers a HFP derivative in dodecylphosphocholine (DPC) micelles. The micelles serve as a membrane mimetic with which membrane-associated peptides can be studied by liquid-state NMR. A perdeuterated DPC-d38 micelle contains 50–60 detergent molecules with ~20 kD mass and reorients rapidly in aqueous solution such that a large fraction of the proton resonances of an associated peptide can be resolved [11, 12]. Because lipid molecules with phosphocholine headgroups represent half of the total lipid in HIV host cell membranes, DPC may be a reasonable detergent choice for HFP studies [13, 14]. DPC has also been used for NMR studies of other peptides [15–20]. Observed structures include helices on the micelle surface and helices which traverse the micelle.

Previous NMR and simulation studies of detergent-associated peptides containing the HFP sequence provided evidence for helical structure over some of the residues but there were differences among the studies about the specific helical regions and about the location of the peptide in the micelle [21]. As one example, HFP comprising the first 23 residues of gp41 has been studied in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and DPC detergent micelles [22–24]. In SDS, helical structure was reported from I4 to G16 followed by a β turn, while in DPC, helical structure was reported from I4 to M19 with no β turn. For a SDS-associated “HFP51” which contained residues 5–55 of gp41, helical structure was detected from F8 to G13 and from V28 to Q41 [25]. For a SDS-associated “HFP30” which contained a non-native proline followed by the first thirty residues of gp41 and an eight-residue non-native polar sequence, an uninterrupted helix was detected from I4 to M19 with some helical structure from G20 to A22 [26]. The remaining residues were motionally disordered. The HFP30 study was distinct in that the peptide contained U-13C, 15N labeling and so in addition to Hα shifts and NOEs, there were additional structural constraints from 13C shifts and from 3JHNHα and residual dipolar couplings.

There has been some controversy about the location of the HFP in micelles. Simulation studies have supported an amphipathic helix on the micelle surface with more hydrophobic sidechains in the micelle interior and less hydrophobic Ala and Gly residues on the micelle surface [27, 28]. However, there were slow amide proton exchange rates with water protons for residues between Ile-4 and Ala-15 which suggested that these residues were not exposed to water and that their ~18 Å length may reside within the central ~30 Å diameter hydrophobic core of the micelle [22, 23, 26, 28, 29].

For HFP in aqueous solution at pH 3, liquid-state NMR data were consistent with predominantly unstructured peptide, while in organic solvents, both helical and β strand conformations have been observed [30, 31]. A variety of biophysical techniques other than liquid-state NMR have been applied to study membrane-associated HFP and show helical conformation as well as β strand conformation which is associated with formation of HFP oligomers or aggregates [1, 32–35].

This paper investigates DPC-associated HFP derivatives using 2D COSY, TOCSY, and NOESY spectra. There was selective 13CO labeling in the peptide and 13C spectra were recorded to obtain additional information. As part of the work, a sensitivity comparison was made between spectra obtained with a conventional probe and with a cryoprobe. The two HFP derivatives are denoted HFPK3 (AVGIGALFLGFLGAAGSTMGARSKKK) and HFPK3W (AVGIGALFLGFLGAAGSTMGARSKKKW) and contained 23 N-terminal residues of the HIV gp41 fusion protein (LAV1a strain) and three non-native lysines to increase aqueous solubility. For HFPK3W, there was an additional non-native tryptophan for concentration determination using 280 nm absorbance.

HFPK3 and HFPK3W were studied in part because they are monomeric in buffered neutral solution without detergent and differ from HFP, which aggregates under these conditions [36]. These derivatives are thus reasonable model systems to study membrane- or detergent-induced peptide self-association. Lysine-containing HFPs have also been used to synthesize C-terminal cross-linked HFPs which mimic the expected topology of fusion peptides in the trimeric gp41 protein [37–43]. These cross-linked HFPs induce vesicle fusion with a rate which is 5–40 times higher than that of non-cross-linked peptides. One of the motivations for the present study was to assess whether future studies on detergent-associated cross-linked peptides can be done with unlabeled peptide or whether it will be necessary to incorporate U-13C, 15N labeling.

Materials and Methods

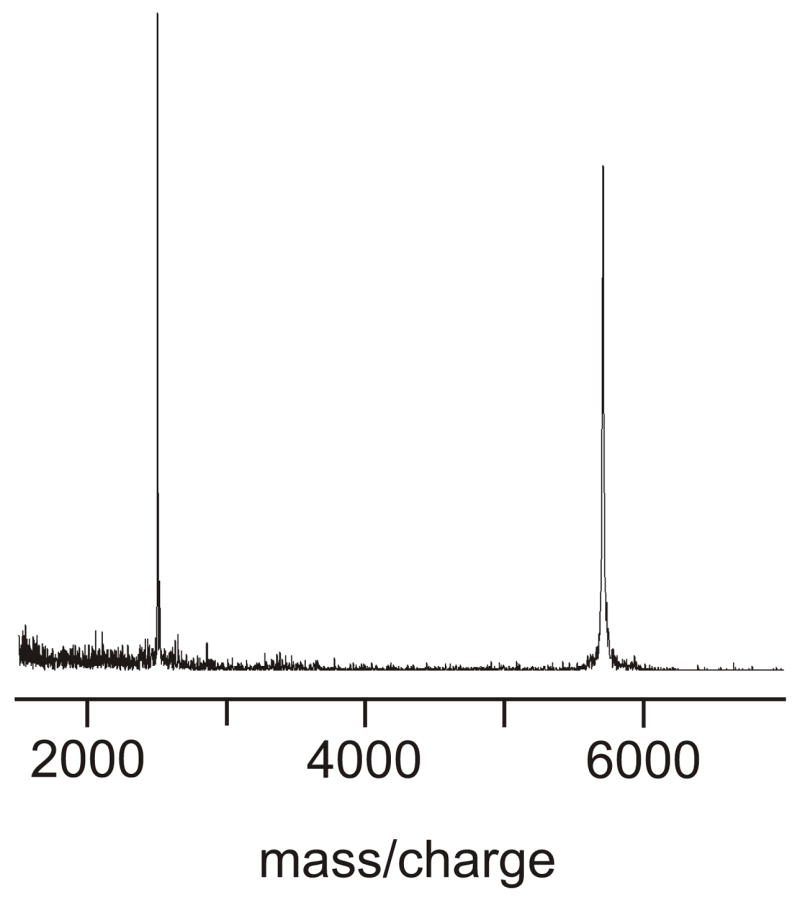

Peptides were synthesized as C-terminal amides on a solid-phase peptide synthesizer (ABI, Foster City, CA) using FMOC chemistry and acetic anhydride capping and were purified by reversed-phase HPLC. Fig. 1 displays a mass spectrum of purified HFPK3 which indicated that any impurity peaks were <5% of the main mass peak. HFPK3 contained selective 13CO labeling at F8, L9, and G10, and HFPK3W contained a 13CO label at F8 and a 15N label at L9.

Figure 1.

MALDI mass spectrum of HFPK3 with internal bovine insulin reference (mass 5733 D). The experimental HFPK3 mass is 2511 D and the expected HFPK3 mass is 2512 D.

Sample preparation began with vortexing dry DPC-d38 (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) in 5 mM pH 7 HEPES-d18 buffer containing 0.2 mM 3-(trimethylsilyl)-1-propanesulfonic acid, sodium salt (DSS), 0.03% NaN3 preservative, and 10% D2O. Lyophilized peptide was then dissolved in the detergent solution and the pH was adjusted to 7.0. Four samples were prepared: “sample 1” contained ~2 mM HFPK3W and ~100 mM DPC; “sample 2” contained ~2 mM HFPK3W and ~200 mM DPC; “sample 3” contained ~3 mM HFPK3 and ~300 mM DPC; and “sample 4” was sample 3 with added DPC and contained ~3 mM HFPK3 and ~700 mM DPC.

A Varian Inova 600 MHz spectrometer with a conventional probe was used to obtain DQ-COSY, TOCSY and NOESY spectra of sample 1, TOCSY and NOESY spectra of sample 3, and a NOESY spectrum of sample 4. A Bruker Avance-AQS 700 MHz spectrometer with a cryoprobe was used to obtain a NOESY spectrum of sample 2. The sample temperatures were 40 °C. The TOCSY mixing time was 90 ms. The NOESY pulse programs used on samples 1 and 2 were identical and contained in sequence: (1) z-gradient scrambling (6 ms); (2) water presaturation (1.3 s); (3) π/2-pulse; (4) variable length time (t1); (5) π/2-pulse; (6) longitudinal mixing time (τ) with a z-gradient pulse (5 ms) in the middle of water saturation pulses; and (7) π/2-pulse initiated acquisition. At 600 MHz, π/2-pulses were 7.40 μsec and 720 values of t1 were acquired with a 143 μsec increment, τ was 70 or 150 ms, and 1024 complex t2 points were acquired with a 125 μsec increment. At 700 MHz, π/2-pulses were 12.45 μsec, 720 values of t1 were sampled with 102 μsec increment, τ was 70 msec, and 951 complex t2 points were acquired with 102 μsec increment. For the NOESY spectra of sample 3 and 4, π/2-pulses were 6.44 μsec, 800 values of t1 were sampled with 125 μsec increment, τ was 150 msec, and 1024 complex t2 points were acquired with a 125 μsec increment. Effects of water were reduced by means of a WET sequence during τ [44, 45]. All NOESY spectra had 96 transients per t1 value, and scans were summed with a 32-fold phase cycle.

All 2D FIDs were converted to NMRPipe format for processing and analysis [46]. Data sets were zero-filled to produce 0.003 ppm/point digital resolution in each dimension. In t2, the NOESY FIDs were Lorentzian narrowed by 20 Hz and Gaussian broadened by 20 Hz while in t1 they were narrowed by 5 Hz and broadened by 10 Hz and then modified with a sine+60° window. Third-order polynomial baseline correction was applied in each dimension.

The 13C spectra of samples 3 and 4 were recorded on a 500 MHz Varian UnityPlus spectrometer at 25 °C. The sequence used a 6 μsec 76° 13C pulse, 1.3 s acquisition of 35124 complex points with 1H decoupling, and a 5 s recycle delay. The spectrum of sample 3 was the sum of 12200 scans and was referenced to DSS at 0 ppm.

The simulated annealing function of the CNS program was used to calculate structures based on the intensities of unambiguous NOESY crosspeaks [47]. Internuclear distances were related to intensities using either the W27 sidechain HN1-HC2 or the G5 Hα1-Hα2 crosspeaks.

A more detailed description of methods to obtain 1H NMR spectra, make 1H chemical shift assignments, and derive peptide structure has been given in two recent papers from the Veglia and Ramamoorthy groups [48, 49].

Results

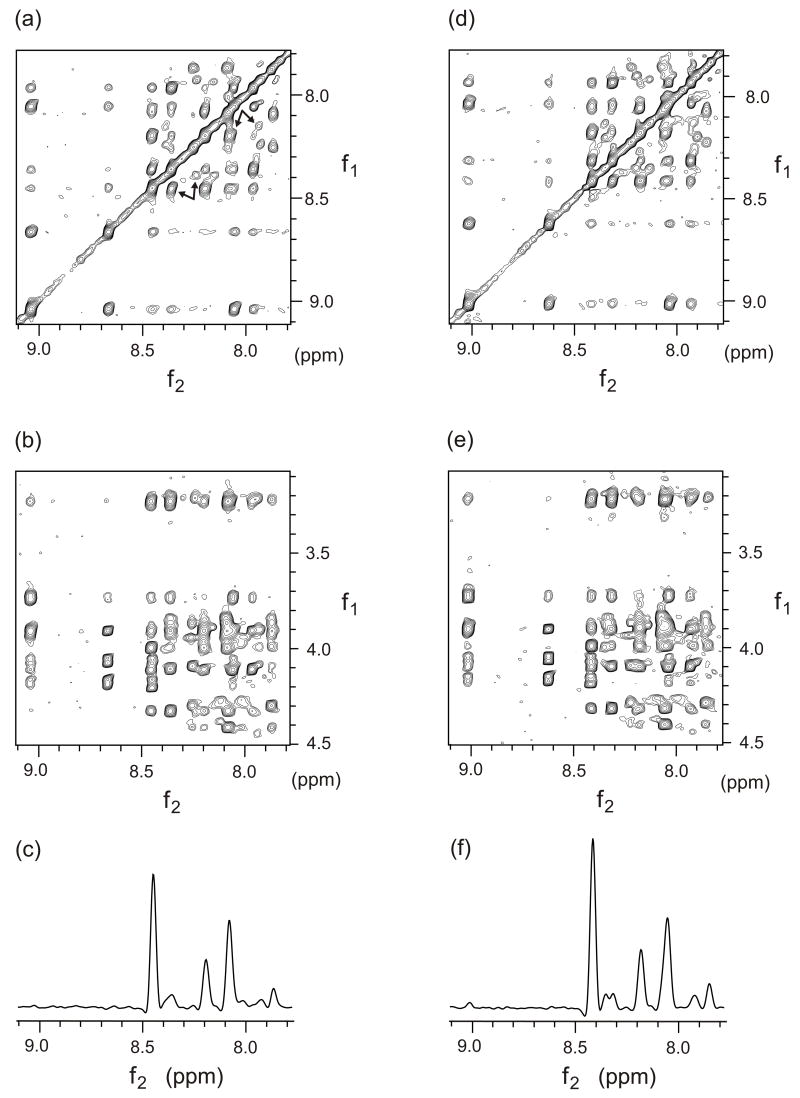

Fig. 2 displays sections of NOESY spectra of sample 3 and sample 4 taken on a 600 MHz instrument with a conventional probe. Both samples had [HFPK3] = 3 mM and [DPC] = 300 (sample 3) or 700 mM (sample 4). The spectra were similar except that the chemical shifts of sample 4 were often 0.02–0.04 ppm lower than the analogous shifts of sample 3. A chemical shift assignment (denoted I) is given in Table 1. Shifts listed under assignment I corresponded to the most intense crosspeaks in the NOESY spectrum of sample 3 except for the shifts of the R, K, and W residues which were based on the much stronger crosspeaks in the DQ-COSY spectrum of sample 1 and the TOCSY spectrum of sample 3. J-splitting was observed for the Hα of G3, G5, G13, and G16. For all but five nuclei, the chemical shift variation among samples 1, 2, and 3 was ≤ 0.02 ppm, and the variation for four of the remaining five nuclei was 0.03–0.04 ppm. Only the L9 HN shift varied more, ranging from 8.54 ppm in sample 1 to 8.45 ppm in sample 3. Shifts were constant for a given sample for at least one month.

Figure 2.

NOESY spectra of HFPK3 in DPC micelles which were recorded at 600 MHz using a conventional probe and a 150 msec mixing time. Spectra a–c were obtained using sample 3 ([HFPK3] = 3 mm, [DPC] = 300 mM) and spectra d–f were obtained using sample 4 ([HFPK3] = 3 mm, [DPC] = 700 mM) and the spectra from the two samples are similar. In spectrum a, a set of paired arrows points to HN/HN crosspeaks with f1 ≈ 8.2 ppm that are assigned to G10/F11 (stronger intensity/assignment I) and G10′/F11′ (weaker intensity/assignment II). Another set of paired arrows points to peaks with f1 ≈ 8.4 ppm that are assigned to L9/F8 (stronger intensity/assignment I) and L9′/F8′ (weaker intensity/assignment II). Spectra c and f are slices through spectra b and e, respectively, f1 = 3.99 ppm. The peaks in spectrum f are assigned to Hα/HN crosspeaks of L9/G5 at (9.01 ppm); L9/L9 (8.41 ppm); L9′/L9′ (8.35 ppm); L9/F8 (8.31 ppm); L9/G10 (8.18 ppm); L9/A6, F11, L12 (8.05 ppm); L12′/F11′ (7.92 ppm); L12′/L12′ (7.84 ppm).

Table 1.

Assignment I of DPC-associated HFPK3 (residues 1–26) and HFPK3W (residue 27)

| HN | Hα | Hβ | Hγ | Hδ | Hε/Hring | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ala-1 | 4.14 | 1.51 | ||||

| Val-2 | 8.10 | 4.21 | 2.13 | 0.99 | ||

| Gly-3 | 8.45 | 4.05, 4.08

4.16, 4.19 |

||||

| Ile-4 | 8.66 | 3.91 | 1.93 | CH2: 1.31, 1.61

CH3: 0.95 |

0.92 | |

| Gly-5 | 9.04 | 3.72, 3.75

3.90, 3.93 |

||||

| Ala-6 | 8.06 | 4.12 | 1.47 | |||

| Leu-7 | 7.96 | 4.11 | 1.62, 1.87 | 1.68 | 0.87, 0.91 | |

| Phe-8 | 8.36 | 4.33 | 3.23 | 7.11, 7.17, 7.21 | ||

| Leu-9 | 8.45 | 4.00 | 1.60, 1.88 | 1.91 | 0.94, 0.95 | |

| Gly-10 | 8.20 | 3.91 | ||||

| Phe-11 | 8.08 | 4.41 | 3.23 | 7.11, 7.17, 7.21 | ||

| Leu-12 | 8.09 | 3.87 | 1.50, 1.74 | 1.69 | 0.79, 1.19 | |

| Gly-13 | 8.10 | 3.84, 3.87

3.90, 3.93 |

||||

| Ala-14 | 7.87 | 4.30 | 1.45 | |||

| Ala-15 | 8.25 | 4.09 | 1.29 | |||

| Gly-16 | 8.36 | 3.84, 3.87

3.91, 3.93 |

||||

| Ser-17 | 8.02 | 4.41 | 3.94, 3.99 | |||

| Thr-18 | 7.99 | 4.29 | 1.43 | |||

| Met-19 | 8.11 | 4.38 | 2.08, 2.11 | 2.57, 2.63 | ||

| Gly-20 | 8.26 | 3.94 | ||||

| Ala-21 | 8.02 | 4.27 | 1.25 | |||

| Arg-22 | 8.12 | 4.30 | 1.82, 1.94 | 1.69 | 3.22 | |

| Ser-23 | 4.40 | 3.87, 3.91 | ||||

| Lys | 7.89 | 4.14 | 1.80 | 1.40 | 1.69 | 3.00 |

| Lys | 7.87 | 4.32 | 1.87, 1.77 | 1.40 | 1.69 | 3.00 |

| Lys | 8.12 | 4.28 | 1.87, 1.81 | 1.40 | 1.69 | 3.00 |

| Trp-27 | 8.05 | 4.29 | 3.21, 3.30 |

NH 10.43, 2H 7.28

4–7H 7.11, 7.45, 7.62 |

There were minimal or no inter-residue NOE connectivities for the shifts of A1, T18, W27, and the three lysines, and the shifts were primarily assigned by similarity to characteristic shifts for these residues.

Relative to the 70 ms NOESY spectrum of HFPK3W (sample 1) at 600 MHz without cryoprobe, there was on average 2.0 times higher signal-to-noise in the 700 MHz spectrum of sample 2 with cryoprobe. An improvement of ~ (7/6)3/2 ~ 1.25 might be expected from the difference in magnetic fields. The improvement varied among different regions of the spectra with an average improvement of 1.8 in the HN/HN region and 2.5 in the Hβ/HN region. Relative to the 600 MHz NOESY spectrum of sample 1 with τ = 70 ms, only three new crosspeaks were observed in the 600 MHz spectrum of sample 1 with τ = 150 ms, and these new crosspeaks were also observed in the 700 MHz spectrum of sample 2 with τ = 70 ms.

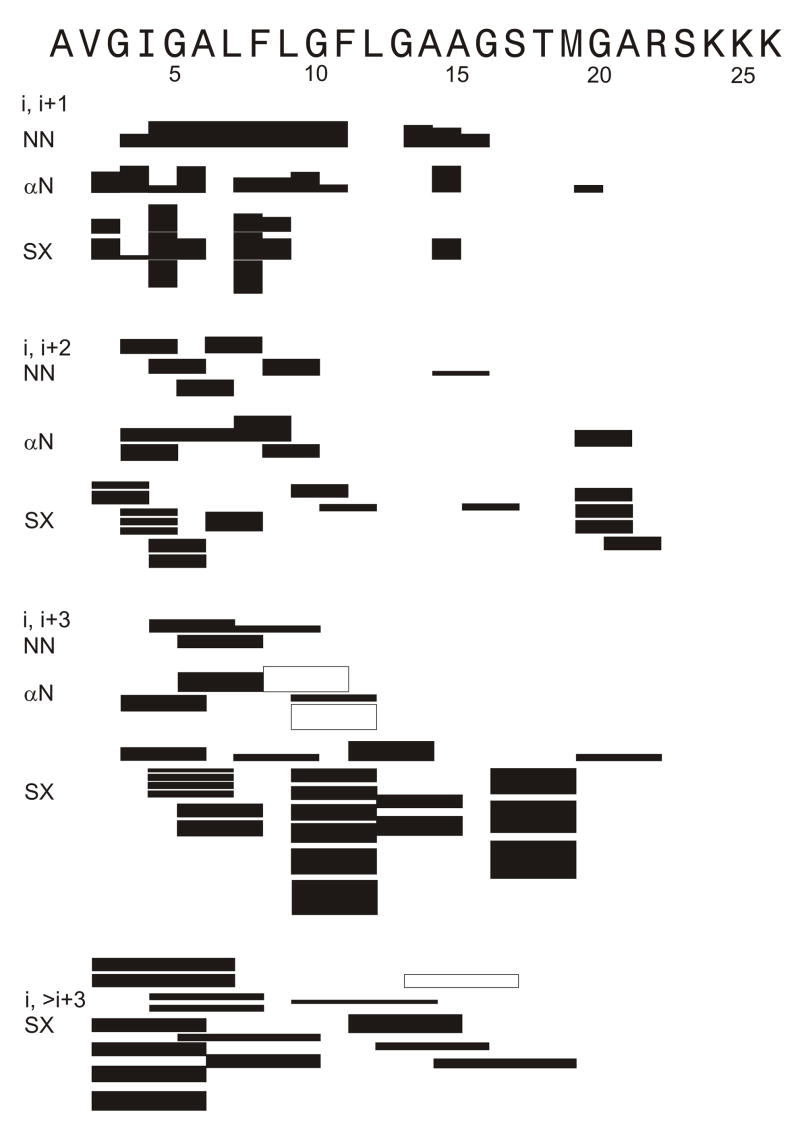

The largest number of NOE crosspeaks was observed in the spectra of samples 3 and 4 which contained the highest peptide concentration and for which WET water suppression was used. The NOE connectivities are graphically displayed in Fig. 3. A subset of these connectivities was observed in the spectra of sample 1 and sample 2.

Figure 3.

Inter-residue NOE connectivities of assignment I shifts. Filled bars have unambiguous assignment and hollow bars have ambiguous assignment. Peak intensity is indicated by line thickness. The “SX” designation refers to any connectivity other than HN-HN or Hα-HN connectivity. Most SX connectivities were between sidechain protons of the two residues. The displayed connectivities were observed for sample 3 and a similar pattern was observed for sample 4. Subsets of these connectivities were observed in the spectra of sample 1 and sample 2.

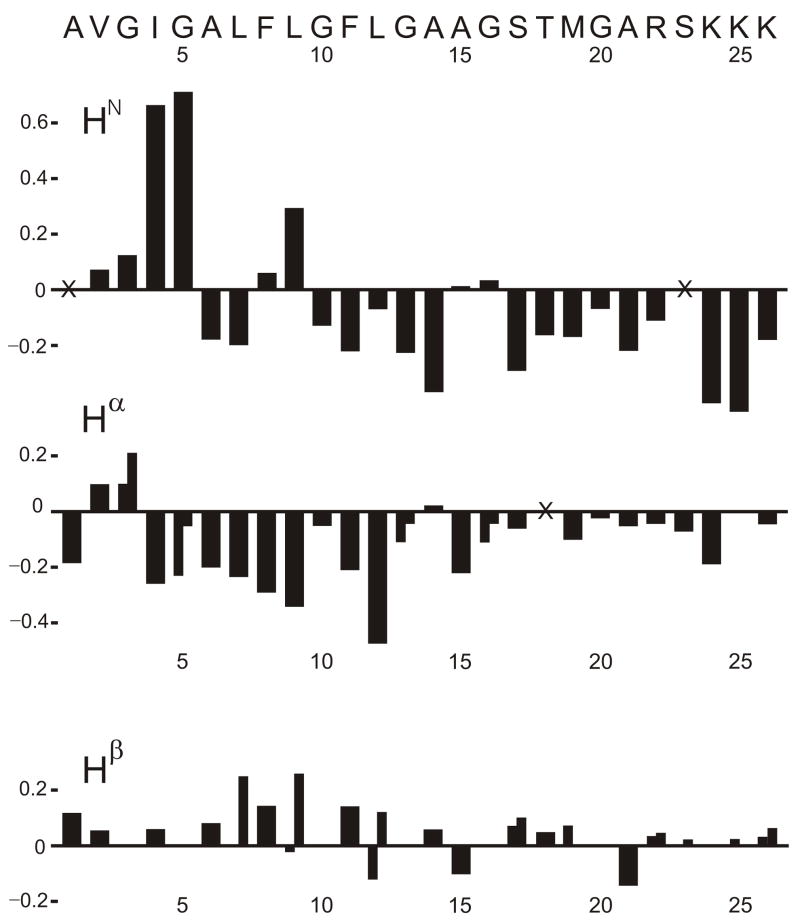

Fig. 4 displays the secondary shift differences between assignment I peaks in Table 1 and random coil shifts and the generally negative Hα and HN secondary shifts indicate helical structure [50, 51]. A TALOS program comparison of sequential triplets of experimental Hα chemical shifts with shifts from a database of assigned proteins of known structure yielded right-handed helical conformation for V2, G5-A15 and G20-R22 [52]. Beta or diverse conformations were predicted for G3, I4, and G16, and no predictions were made for other residues because of lack of assignment certainty for the T18, K24, K25, and K26 residues. Simulated annealing did not yield a well-defined structure which was likely due to the small number of unambiguous Δi ≥ 3 backbone NOE connectivities.

Figure 4.

Secondary chemical shifts in ppm units. With cases of two Hα or two Hβ shifts, the line for each secondary shift is drawn with half-width. Unassigned nuclei are denoted by the × symbol. Blank space at a given nucleus denotes either a nucleus that does not exist (e.g. Gly Hβ) or zero difference from the random coil shift. As noted in Table 1, there is ambiguity in the assignment of individual sets of lysine crosspeaks to specific lysine residues. In this figure, the secondary shifts for the lysine residues have the order given in Table 1.

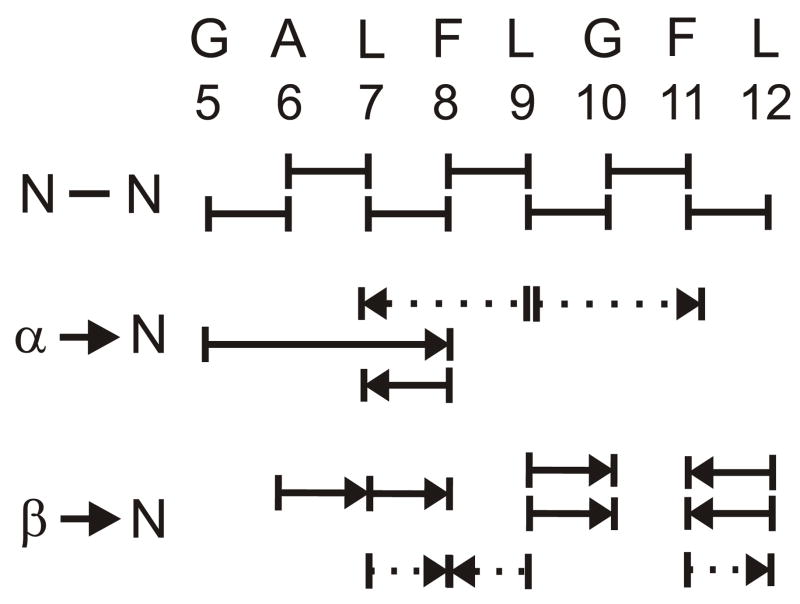

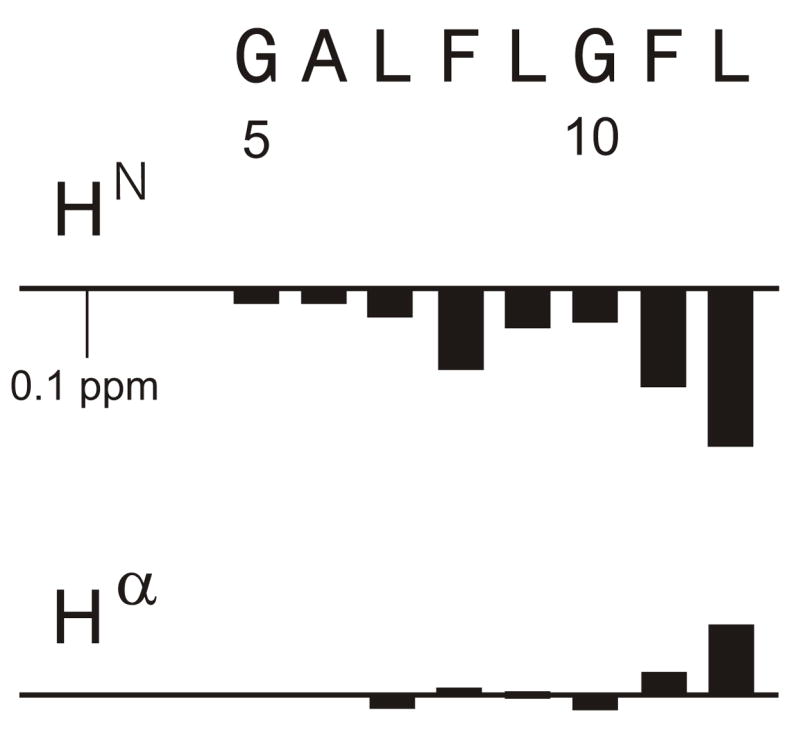

In addition to the strongest crosspeaks used for assignment I and the weaker crosspeaks due to longer range connectivities within this assignment, there were additional weaker crosspeaks in the spectra of all samples. Many of these crosspeaks appeared to be due an alternate peptide structure as evidenced by NOE connectivities between the shifts of these peaks and lack of connectivities with the shifts of assignment I. Table 2 lists “assignment II” for crosspeaks whose intensities were ~10% of those of assignment I and which had contiguous inter-residue connectivities between G5 and L12 (cf. Fig. 5). For the other residues, shifts were assigned by proximity to shifts in assignment I or, for M19, by its characteristic crosspeak pattern. Some of the crosspeaks which led to assignment II are highlighted in Fig. 2. Fig. 6 displays some of the shift differences between the II and I assignments. The HN nuclei exhibited the largest shift differences, which were all negative, while Hα nuclei had both positive and negative differences. Sidechain nuclei exhibited the smallest differences.

Table 2.

Assignments II and III of DPC-associated HFPK3

| HN | Hα | Hβ | Hγ | Hδ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assignment II | |||||

| Ala-1 | 8.17 | 4.25 | 1.36 | ||

| Gly-5 | 9.02 | ||||

| Ala-6 | 8.04 | 3.89 | 1.45 | ||

| Leu-7 | 7.92 | 4.09 | 1.60, 1.85 | 1.66 | 0.86, 0.90 |

| Phe-8 | 8.28 | 4.33 | 3.22 | ||

| Leu-9 | 8.39 | 4.00 | 1.55, 1.85 | 1.91 | 0.92 |

| Gly-10 | 8.15 | 3.89 | |||

| Phe-11 | 7.94 | 4.44 | 3.22 | ||

| Leu-12 | 7.86 | 3.98 | 1.55 | 0.82 | |

| Ala-14 | 7.82 | 4.32 | 1.42 | ||

| Met-19 | 2.19 | 2.92, 2.98 | |||

| Met-19 | 2.31 | 2.93, 2.99 | |||

| Ala-21 | 4.32 | 1.23 | |||

| Ser | 7.76 | 4.52 | 3.90, 3.94 | ||

|

| |||||

| Assignment III | |||||

| Leu-7 | 7.94 | ||||

| Phe-8 | 8.30 | 4.33 | 3.22 | ||

| Leu-9 | 8.41 | ||||

Figure 5.

Inter-residue NOE connectivities of assignment II. Hα/HN and Hβ/HN connectivities are denoted as arrows with the Hα or Hβ residue at the base of the arrow and the HN residue at the point of the arrow. Connectivities with unambiguous assignment are denoted as solid lines, and connectivities with ambiguous assignment are denoted as dotted lines.

Figure 6.

Assignment II – assignment I chemical shift differences for residues G5-L12.

“Assignment III” was made for L7 to L9 and was based on crosspeaks whose intensities were ~5% of those of assignment I and on three inter-residue NOE connectivities. HN chemical shifts of assignment III were closer to those of assignment I than were the HN shifts of assignment II. The combination of assignments I, II, and III accounted for all of the significant crosspeaks in the NMR spectra.

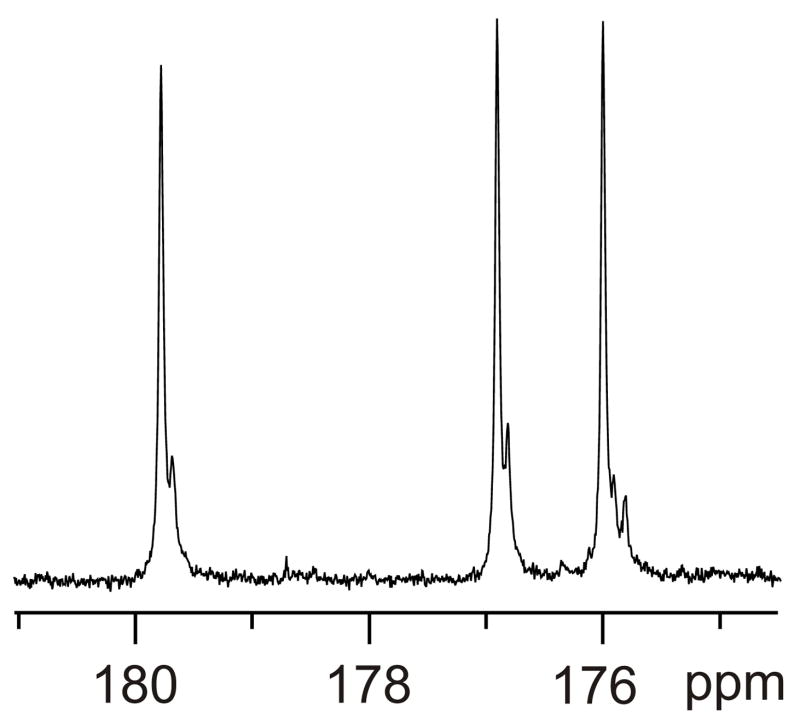

Sample 3 had 13CO labels at F8, L9, and G10, and Fig. 7 displays the CO region of the 13C spectrum of this sample. There are three major peaks at 179.9, 177.1, and 176.2 ppm, which are assigned to L9, F8, and G10, respectively. This assignment is based on: (1) residue-type characteristic shifts; (2) the ~177 ppm F8 13CO shift observed in the filtered solid-state NMR spectrum of a frozen solution sample containing F8 13CO and L9 15N-labeled HFPK3 (2 mM) and DPC (200 mM) at −80 °C; and (3) the 180.45, 177.36, and 176.48 ppm L9, F8, and G10 13CO shifts reported for SDS-associated HFP30 [26, 36, 51]. In Fig. 7, each of the F8 and L9 residues has a smaller peak ~0.09 ppm upfield of the major peak and the G10 residue has two smaller peaks ~0.09 and 0.19 ppm upfield of the major peak. The spectrum of sample 4 was similar except for an additional small peak 0.19 ppm upfield of the main L9 peak. There was general consistency between the minor:major intensity ratios in the 13C spectra and the (assignment II + III)/(assignment I) intensity ratios in the 2D 1H spectra.

Figure 7.

13C spectrum of sample 3 which had 13CO labels at F8, L9, and G10.

For samples 1–4, the peptide:DPC mol ratio was ≤ 0.02 and corresponded to ≤ 1 peptide/micelle. When a fifth sample was made which contained peptide:DPC ~ 0.1 (5 peptides/micelle), the lines were broad (~ 0.1 ppm full-width at half-maximum). This broadening is consistent with peptide aggregation and with detection of β structure in circular dichroism spectra at this peptide:detergent ratio [53]. Sharp NMR signals (~ 0.03 ppm) could be recovered upon addition of DPC to achieve peptide:detergent ~ 0.02 which suggests that aggregation is reversible and that the aggregates contain a small number of peptide molecules.

Discussion

The assignment I shifts of the first twelve residues exhibited abundant backbone NOE connectivity with ten unambiguous Δi = 2 crosspeaks and six unambiguous Δi = 3 crosspeaks. The I4-L12 Hα shifts were all consistent with helical conformation but the presence of both Δi = 2 and Δi = 3 backbone NOEs was consistent with a variety of secondary structures and may provide some basis for why simulated annealing did not result in a well-defined conformation [54]. There were many fewer backbone NOEs for residues C-terminal of L12 which indicates a higher degree of motion in the C-terminal part of the peptide. In the COSY and TOCSY spectra, weaker intensities were likewise observed for residues C-terminal of G16. These observations support a model of more-defined structure in the N-terminal region and less-defined structure in the C-terminal region. This model is consistent with stronger interaction of the apolar N-terminal region with the micelle and with weaker interaction of the more polar C-terminal region with the micelle.

Relative to previous studies of detergent-associated HFP, the smaller number of NOEs seen with HFPK3 and HFPK3W may be due to the three non-native C-terminal lysines which inhibit peptide aggregation in aqueous solution. These residues may similarly solubilize the C-terminal segment of the DPC-associated peptide and the increased motion may reduce NOE intensity. The relatively sparse NOE data for HFPK3 suggest that structure determination of detergent-associated lysine-rich cross-linked HFPs will require U-13C, 15N labeling and structural constraints other than NOEs.

It is interesting to compare backbone chemical shift assignment I in Table 1 with the three previously published assignments. When the same referencing is used for DPC-associated HFPK3 and DPC-associated HFP, the HN shifts of residues G3-R22 of the HFP sample are on average +0.12 ppm higher than the corresponding shifts of the HFPK3 sample [24, 55]. A similar comparison of the Hα shifts yields HFP shifts which are +0.05 ppm higher. The different average offsets for different nuclei suggest that this is not a referencing problem. Because the HFP and HFPK3 shifts are reported at 298 and 313 K, respectively, there may be some temperature component to the offsets. However, temperature dependences of shifts reported in the literature would predict smaller offsets than those observed between the HFP and HFPK3 assignments [56]. After the +0.12 ppm and +0.05 ppm offsets are removed for HN and Hα, the average magnitude of difference 〈|δHFP –δHFPK3|〉 between the two assignments is 0.03 ppm.

Although the SDS-associated HFP and HFP30 shifts were obtained at 293 and 298 K, respectively, there were no systematic offsets between assignment I of residues L7-A21 and the corresponding assignments of the SDS-associated HFP constructs. Comparison of assignment I and the assignment of SDS-associated HFP yielded an average magnitude of difference for both HN and Hα shifts of 0.06 ppm while for the HFP30 construct, the variation was only 0.03 ppm [22, 26]. For G3 to A6, the Hα shifts agreed to within 0.1 ppm among the three assignments but the HN shifts of the SDS samples were substantially smaller (up to 0.64 ppm) than the HN shifts of assignment I. The HN assignment of the two SDS-associated peptides agreed to within 0.1 ppm over this residue range. For residue V2, there was large variation among the three assignments for both HN and Hα (up to 0.68 and 0.16 ppm, respectively).

The chemical shift information may be related to structural features. We first compare DPC-associated HFPK3 assignment I with SDS-associated HFP30 because there are the greatest structural data for the latter sample. For the two samples, there is 0.02 ppm average magnitude variation of the I4-A21 Hα shifts. These shifts are sensitive to local conformation and the small shift variation among the two samples is consistent with very similar conformations over I4-A21, i.e. a single helix from I4-M19 and some helical structure at G20 and A21. This structure contrasts with the helix-turn-helix motif observed for the DPC-associated influenza fusion peptide and demonstrates that there is significant variation of helical structures of fusion peptides from different viruses [18]. There is 0.05 ppm average magnitude variation of L7-A21 HN shifts. These shifts are sensitive to local conformation as well as hydrogen bonding and the small shift variation among the two samples suggests that the two samples have similar conformations as well as hydrogen bond partners over these residues. These results also correlate with the similar 1H/15N HSQC spectra obtained for HFP30 in SDS and DPC [26].

For the G3-A6 HN shifts, there are differences as large as 0.64 ppm between the HFPK3 and HFP30 samples. This observation may be explained by different hydrogen bonding environments for these nuclei because they are at the N-terminus of a helix. The G3-A6 HN shifts for SDS-associated HFP and HFP30 agree to within 0.1 ppm and the G3-A6 HN shifts for DPC-associated HFP and HFPK3 agree to within 0.1 ppm if the previously discussed 0.12 ppm offset is removed. These data suggest a significant detergent effect on HN shifts in this region. While all samples had pH ~ 7, the SDS-associated HFP30 and DPC-associated HFPK3 were buffered while the SDS- and DPC-associated HFP samples were not buffered. These data suggest that buffer does not play a large role in the HN chemical shifts.

The chemical shift comparison also provides information about fusion peptide location in micelles which relates to the important question of peptide location in membranes. The insertion angle and depth of the peptide are parameters which are believed to relate to fusion peptide activity [8, 57, 58]. Two models for the peptide location in the micelle are a surface-associated amphipathic helix and a helix whose I4 to A15 region resides within the hydrophobic micellar interior [22, 23, 26, 28]. The similarity of the backbone shifts of SDS-associated HFP30 and DPC-associated HFPK3 argues in favor of the same micelle orientation for the two peptides. In particular, the helical L7-A14 residues of SDS-associated HFP30 are posited to be in the hydrophobic micelle interior and there would likely be shift changes in our DPC-associated HFPK3 sample if some of these residues were in the aqueous headgroup region as would be expected for a surface orientation. It is possible that the systematic shift difference between DPC-associated HFP and DPC-associated HFPK3 is partially due to different locations in the micelle. We note that there have been conflicting results about HFP location in membranes in other experimental and computational studies [8, 59–61].

As discussed above, the G3-A6 HN are likely not part of intra-peptide hydrogen bonds and their shifts are thus more sensitive to the local environment. The G3-A6 HN shifts are different for DPC- and SDS-associated peptides and could reasonably be correlated to the location of these residues near the different headgroups of the two detergents. This result is consistent with other data in the HFP30 study [26].

A distinguishing feature of the current fusion peptide study is the observation of additional crosspeaks which led to assignments II and III. There were inter-residue NOE connectivities between assignment I shifts, between assignment II shifts, and between assignment III shifts, but there are no connectivities between shifts from different assignments. This observation suggests that there are three distinct peptide species.

It is noted that alternate crosspeaks and assignments have been observed for other peptides associated with detergent or membranes [62–65]. In some studies, it was observed that increased detergent concentration resulted in smaller ratios of alternate to primary crosspeak intensities [66–68]. However, in the present study, assignment II:assignment I ratios of ~0.1 were observed for [HFPK3] = 3 mM and either [DPC] = 300 mM (sample 3) or [DPC] = 700 mM (sample 4) as well as for [HFPK3W] = 2 mM, [DPC] = 100 mM (sample 1) or [HFPK3W] = 2 mM, [DPC] = 200 mM (sample 2). The assignment II crosspeaks of DPC-associated HFPK3 are probably also too large to be ascribed to a peptide impurity (cf. Fig. 1). Sample degradation is another possibility but seems unlikely because: (1) the samples contained 0.03% NaN3 preservative; (2) the assignment II/assignment I crosspeak intensity ratio of ~0.1 was observed for several samples; and (3) assignment II shifts were observed across the length of the peptide. Assignment II could be due to a peptide population with oxidized M19, but NMR studies of other peptides have shown that methionine oxidation only affects shifts of nearby residues [69, 70]. The crosspeaks might also be due to peptide not bound to DPC but this seems unlikely because [unbound HFPK3]/[bound HFPK3] ~ 0.001 as calculated using [HFPK3], [DPC], and the published HFP/DPC association constant [24]. In addition, unbound HFPK3 likely has a different conformation than DPC-associated HFPK3 with corresponding large changes in chemical shifts [22, 30]. By contrast, the differences between assignment I and II shifts are ~0.05 ppm with larger differences for HN than for Hα. Differences of this order-of-magnitude could be associated with different helical curvatures for the assignment I and II species [71]. Alternatively, the two species could have different micelle locations. It is intriguing that the shift differences in Fig. 6 oscillate with the approximate period of an α helix. This might be expected when comparing the residues of a peptide which traverses the micelle and those of a peptide on the micelle surface. In the former species, all residues would be in the hydrophobic micellar interior, while in the latter species, there could be α helical alternation of residues between the hydrophobic interior and the aqueous headgroup region. Crosspeaks were not observed between the shifts of different assignments which suggests that the characteristic exchange times between the species are longer than the NOESY exchange times of ~100 ms.

The line broadening observed with high HFPK3:DPC ratio may be due to formation of aggregates and recovery of sharp signals with detergent addition may reflect conversion to helical monomers. The reversibility suggests that the aggregates are small which correlates with: (1) the trimeric association state of gp41; (2) data on small aggregate size in membrane-associated HFPs; and (3) functional and modeling studies suggesting that fusion is most efficiently mediated by small fusion protein and fusion peptide aggregates [10, 36, 72–74].

In summary, 1H chemical shift assignment of the DPC-associated HFPK3 fusion peptide derivative yielded chemical shifts similar to those of other detergent-associated fusion peptide derivatives and were particularly close to those of the SDS-associated HFP30 peptide. This similarity suggests comparable helical conformation and micelle location for the two peptides. The main shift differences between the two peptides occurred for G3-A6 HN and are consistent with the proximity of these nuclei to the micellar headgroup region. In addition to the assignment I shifts corresponding to the most intense peaks in the spectra, there was a set of assignment II shifts which corresponded to less intense peaks. The magnitudes of the differences between assignment II and assignment I shifts were typically 0.05 ppm and HN exhibited the largest differences. The two assignments may correspond to different peptide helical curvatures or to different peptide locations in the micelle.

Acknowledgments

Peptides were prepared by Jun Yang, the mass spectrum was taken by Wei Qiang, and sample 1 spectra were obtained by Vamshi Cotla and Aizhuo Liu. The sample 2 spectrum was obtained with the assistance of Larry Clos and John SantaLucia. The WET-NOESY pulse sequence was recommended by Daniel Holmes. The research was supported by NIH R01 AI47153 and by the state of Michigan.

Abbreviations

- COSY

correlation spectroscopy

- DPC

dodecylphosphocholine

- DQ-COSY

double-quantum filtered correlation spectroscopy

- DSS

3-(trimethylsilyl)-1-propanesulfonic acid, sodium salt

- HEPES

N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid

- HFP

HIV fusion peptide

- HFPK3

HIV fusion peptide plus three lysines

- HFPK3W

HIV fusion peptide plus three lysines and a tryptophan

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- NOESY

nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- TOCSY

total correlation spectroscopy

- WET

water suppression enhanced through T1 effects

- 2D

two-dimensional

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Durell SR, Martin I, Ruysschaert JM, Shai Y, Blumenthal R. What studies of fusion peptides tell us about viral envelope glycoprotein-mediated membrane fusion. Mol Membr Biol. 1997;14:97–112. doi: 10.3109/09687689709048170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nieva JL, Agirre A. Are fusion peptides a good model to study viral cell fusion? Biochim Biophys Acta-Biomembr. 2003;1614:104–115. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epand RM. Fusion peptides and the mechanism of viral fusion. Biochim Biophys Acta-Biomembranes. 2003;1614:116–121. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00169-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freed EO, Delwart EL, Buchschacher GL, Jr, Panganiban AT. A mutation in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein gp41 dominantly interferes with fusion and infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:70–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mobley PW, Curtain CC, Kirkpatrick A, Rostamkhani M, Waring AJ, Gordon LM. The amino-terminal peptide of HIV-1 glycoprotein-41 lyses human erythrocytes and CD4+ lymphocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1139:251–256. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(92)90098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaal H, Klein M, Gehrmann P, Adams O, Scheid A. Requirement of N-terminal amino acid residues of gp41 for human immunodeficiency virus type 1-mediated cell fusion. J Virol. 1995;69:3308–3314. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3308-3314.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delahunty MD, Rhee I, Freed EO, Bonifacino JS. Mutational analysis of the fusion peptide of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1: identification of critical glycine residues. Virology. 1996;218:94–102. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin I, Schaal H, Scheid A, Ruysschaert JM. Lipid membrane fusion induced by the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 N-terminal extremity is determined by its orientation in the lipid bilayer. J Virol. 1996;70:298–304. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.298-304.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira FB, Goni FM, Muga A, Nieva JL. Permeabilization and fusion of uncharged lipid vesicles induced by the HIV-1 fusion peptide adopting an extended conformation: dose and sequence effects. Biophys J. 1997;73:1977–1986. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78228-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pritsker M, Rucker J, Hoffman TL, Doms RW, Shai Y. Effect of nonpolar substitutions of the conserved Phe11 in the fusion peptide of HIV-1 gp41 on its function, structure, and organization in membranes. Biochemistry. 1999;38:11359–11371. doi: 10.1021/bi990232e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lauterwein J, Bosch C, Brown LR, Wuthrich K. Physicochemical studies of the protein-lipid interactions in melittin-containing micelles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;556:244–264. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(79)90046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tieleman DP, van der Spoel D, Berendsen HJC. Molecular dynamics simulations of dodecylphosphocholine micelles at three different aggregate sizes: Micellar structure and chain relaxation. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104:6380–6388. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aloia RC, Tian H, Jensen FC. Lipid composition and fluidity of the human immunodeficiency virus envelope and host cell plasma membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5181–5185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brugger B, Glass B, Haberkant P, Leibrecht I, Wieland FT, Krasslich HG. The HIV lipidome: A raft with an unusual composition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2641–2646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511136103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keire DA, Fletcher TG. The conformation of substance P in lipid environments. Biophys J. 1996;70:1716–1727. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79734-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gesell J, Zasloff M, Opella SJ. Two-dimensional 1H NMR experiments show that the 23-residue magainin antibiotic peptide is an α-helix in dodecylphosphocholine micelles, sodium dodecylsulfate micelles, and trifluoroethanol/water solution. J Biomol NMR. 1997;9:127–135. doi: 10.1023/a:1018698002314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schibli DJ, Montelaro RC, Vogel HJ. The membrane-proximal tryptophan-rich region of the HIV glycoprotein, gp41, forms a well-defined helix in dodecylphosphocholine micelles. Biochemistry. 2001;40:9570–9578. doi: 10.1021/bi010640u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han X, Bushweller JH, Cafiso DS, Tamm LK. Membrane structure and fusion-triggering conformational change of the fusion domain from influenza hemagglutinin. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:715–720. doi: 10.1038/90434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Syvitski RT, Burton I, Mattatall NR, Douglas SE, Jakeman DL. Structural characterization of the antimicrobial peptide pleurocidin from winter flounder. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7282–7293. doi: 10.1021/bi0504005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buffy JJ, Buck-Koehntop BA, Porcelli F, Traasethl NJ, Thomas DD, Veglia G. Defining the intramembrane binding mechanism of sarcolipin to calcium ATPase using solution NMR spectroscopy. J Mol Biol. 2006;358:420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vidal P, Chaloin L, Heitz A, Van Mau N, Mery J, Divita G, Heitz F. Interactions of primary amphipathic vector peptides with membranes. Conformational consequences and influence on cellular localization. J Membr Biol. 1998;162:259–264. doi: 10.1007/s002329900363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang DK, Cheng SF, Chien WJ. The amino-terminal fusion domain peptide of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 inserts into the sodium dodecyl sulfate micelle primarily as a helix with a conserved glycine at the micelle-water interface. J Virol. 1997;71:6593–6602. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6593-6602.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang DK, Cheng SF. Determination of the equilibrium micelle-inserting position of the fusion peptide of gp41 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 at amino acid resolution by exchange broadening of amide proton resonances. J Biomol NMR. 1998;12:549–552. doi: 10.1023/a:1008399304450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morris KF, Gao XF, Wong TC. The interactions of the HIV gp41 fusion peptides with zwitterionic membrane mimics determined by NMR spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta-Biomembr. 2004;1667:67–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang DK, Cheng SF, Trivedi VD. Biophysical characterization of the structure of the amino-terminal region of gp41 of HIV-1. Implications on viral fusion mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5299–5309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaroniec CP, Kaufman JD, Stahl SJ, Viard M, Blumenthal R, Wingfield PT, Bax A. Structure and dynamics of micelle-associated human immunodeficiency virus gp41 fusion domain. Biochemistry. 2005;44:16167–16180. doi: 10.1021/bi051672a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gordon LM, Mobley PW, Lee W, Eskandari S, Kaznessis YN, Sherman MA, Waring AJ. Conformational mapping of the N-terminal peptide of HIV-1 gp41 in lipid detergent and aqueous environments using 13C-enhanced Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1012–1030. doi: 10.1110/ps.03407704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langham A, Kaznessis Y. Simulation of the N-terminus of HIV-1 glycoprotein 41000 fusion peptide in micelles. J Pept Sci. 2005;11:215–224. doi: 10.1002/psc.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacKerell AD. Molecular dynamics simulation analysis of a sodium dodecyl sulfate micelle in aqueous solution: Decreased fluidity of the micelle hydrocarbon interior. J Phys Chem. 1995;99:1846–1855. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang DK, Chien WJ, Cheng SF. The FLG motif in the N-terminal region of glucoprotein 41 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 adopts a type-I beta turn in aqueous solution and serves as the initiation site for helix formation. Eur J Biochem. 1997;247:896–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanyalkar M, Srivastava S, Saran A, Coutinho E. Conformational study of fragments of envelope proteins (gp120: 254–274 and gp41: 519–541) of HIV-1 by NMR and MD simulations. J Pept Sci. 2004;10:363–380. doi: 10.1002/psc.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rafalski M, Lear JD, DeGrado WF. Phospholipid interactions of synthetic peptides representing the N-terminus of HIV gp41. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7917–7922. doi: 10.1021/bi00486a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peisajovich SG, Epand RF, Pritsker M, Shai Y, Epand RM. The polar region consecutive to the HIV fusion peptide participates in membrane fusion. Biochemistry. 2000;39:1826–1833. doi: 10.1021/bi991887i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saez-Cirion A, Nieva JL. Conformational transitions of membrane-bound HIV-1 fusion peptide. Biochim Biophys Acta-Biomembr. 2002;1564:57–65. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00400-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang J, Weliky DP. Solid state nuclear magnetic resonance evidence for parallel and antiparallel strand arrangements in the membrane-associated HIV-1 fusion peptide. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11879–11890. doi: 10.1021/bi0348157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang J, Prorok M, Castellino FJ, Weliky DP. Oligomeric β-structure of the membrane-bound HIV-1 fusion peptide formed from soluble monomers. Biophys J. 2004;87:1951–1963. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.028530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan K, Liu J, Wang J, Shen S, Lu M. Atomic structure of a thermostable subdomain of HIV-1 gp41. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12303–12308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weissenhorn W, Dessen A, Harrison SC, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature. 1997;387:426–430. doi: 10.1038/387426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan DC, Fass D, Berger JM, Kim PS. Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell. 1997;89:263–273. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caffrey M, Cai M, Kaufman J, Stahl SJ, Wingfield PT, Covell DG, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM. Three-dimensional solution structure of the 44 kDa ectodomain of SIV gp41. EMBO J. 1998;17:4572–4584. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang ZN, Mueser TC, Kaufman J, Stahl SJ, Wingfield PT, Hyde CC. The crystal structure of the SIV gp41 ectodomain at 1.47 Å resolution. J Struct Biol. 1999;126:131–144. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang R, Yang J, Weliky DP. Synthesis, enhanced fusogenicity, and solid state NMR measurements of cross-linked HIV-1 fusion peptides. Biochemistry. 2003;42:3527–3535. doi: 10.1021/bi027052g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang R, Prorok M, Castellino FJ, Weliky DP. A trimeric HIV-1 fusion peptide construct which does not self-associate in aqueous solution and which has 15-fold higher membrane fusion rate. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:14722–14723. doi: 10.1021/ja045612o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ogg RJ, Kingsley PB, Taylor JS. WET, a T1-insensitive and B1-insensitive water-suppression method for in-vivo localized 1H NMR spectroscopy. J Magn Reson B. 1994;104:1–10. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1994.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smallcombe SH, Patt SL, Keifer PA. WET solvent suppression and its applications to LC NMR and high-resolution NMR spectroscopy. J Magn Reson A. 1995;117:295–303. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystall D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Porcelli F, Buck B, Lee DK, Hallock KJ, Ramamoorthy A, Veglia G. Structure and orientation of pardaxin determined by NMR experiments in model membranes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45815–45823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405454200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Porcelli F, Buck-Koehntop BA, Thennarasu S, Ramamoorthy A, Veglia G. Structures of the dimeric and monomeric variants of magainin antimicrobial peptides (MSI-78 and MSI-594) in micelles and bilayers, determined by NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2006;45:5793–5799. doi: 10.1021/bi0601813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wishart DS, Bigam CG, Holm A, Hodges RS, Sykes BD. 1H, 13C and 15N random coil NMR chemical shifts of the common amino acids.I. Investigations of nearest-neighbor effects. J Biomol NMR. 1995;5:67–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00227471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang HY, Neal S, Wishart DS. RefDB: A database of uniformly referenced protein chemical shifts. J Biomol NMR. 2003;25:173–195. doi: 10.1023/a:1022836027055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gordon LM, Curtain CC, Zhong YC, Kirkpatrick A, Mobley PW, Waring AJ. The amino-terminal peptide of HIV-1 glycoprotein 41 interacts with human erythrocyte membranes: peptide conformation, orientation and aggregation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1139:257–274. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(92)90099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dyson HJ, Rance M, Houghten RA, Wright PE, Lerner RA. Folding of immunogenic peptide-fragments of proteins in water solution II. The nascent helix. J Mol Biol. 1988;201:201–217. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90447-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wishart DS, Bigam CG, Yao J, Abildgaard F, Dyson HJ, Oldfield E, Markley JL, Sykes BD. 1H, 13C and 15N chemical shift referencing in biomolecular NMR. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:135–140. doi: 10.1007/BF00211777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baxter NJ, Williamson MP. Temperature dependence of 1H chemical shifts in proteins. J Biomolec NMR. 1997;9:359–369. doi: 10.1023/a:1018334207887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peuvot J, Schanck A, Lins L, Brasseur R. Are the fusion processes involved in birth, life and death of the cell depending on tilted insertion of peptides into membranes? J Theor Biol. 1999;198:173–81. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1999.0908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bradshaw JP, Darkes MJ, Harroun TA, Katsaras J, Epand RM. Oblique membrane insertion of viral fusion peptide probed by neutron diffraction. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6581–6585. doi: 10.1021/bi000224u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kamath S, Wong TC. Membrane structure of the human immunodeficiency virus gp41 fusion domain by molecular dynamics simulation. Biophys J. 2002;83:135–143. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75155-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maddox MW, Longo ML. Conformational partitioning of the fusion peptide of HIV-1 gp41 and its structural analogs in bilayer membranes. Biophys J. 2002;83:3088–3096. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75313-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wasniewski CM, Parkanzky PD, Bodner ML, Weliky DP. Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance studies of HIV and influenza fusion peptide orientations in membrane bilayers using stacked glass plate samples. Chem Phys Lipids. 2004;132:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Henry GD, Sykes BD. Assignment of amide 1H and 15N NMR resonances in detergent-solubilized M13 coat protein: A model for the coat protein dimer. Biochemistry. 1992;31:5284–5297. doi: 10.1021/bi00138a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang GS, Sparrow JT, Cushley RJ. The helix-hinge-helix structural motif in human apolipoprotein A-I determined by NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1997;36:13657–13666. doi: 10.1021/bi971151q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.MacRaild CA, Howlett GJ, Gooley PR. The structure and interactions of human apolipoprotein C-II in dodecyl phosphocholine. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8084–8093. doi: 10.1021/bi049817l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Buffy JJ, Traaseth NJ, Mascioni A, Gor’kov PL, Chekmenev EY, Brey WW, Veglia G. Two-dimensional solid-state NMR reveals two topologies of sarcolipin in oriented lipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10939–10946. doi: 10.1021/bi060728d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van de Ven FJM, van Os JWM, Aelen JMA, Wymenga SS, Remerowski ML, Konings RNH, Hilbers CW. Assignment of 1H, 15N, and backbone 13C resonances in detergent-solubilized M13 coat protein via multinuclear multidimensional NMR: A model for the coat protein monomer. Biochemistry. 1993;32:8322–8328. doi: 10.1021/bi00083a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McDonnell PA, Opella SJ. Effect of detergent concentration on multidimensional solution NMR spectra of membrane proteins in micelles. J Magn Reson B. 1993;102:120–125. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hinton JF, Washburn AM. Species heterogeneity of Gly-11 Gramicidin A incorporated into sodium dodecyl sulfate micelles. Biophys J. 1995;69:435–438. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79916-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Johansson J, Szyperski T, Curstedt T, Wuthrich K. The NMR structure of the pulmonary surfactant-associated polypeptide Sp-C in an apolar solvent contains a valyl-rich α-helix. Biochemistry. 1994;33:6015–6023. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kurutz JW, Lee KYC. NMR structure of lung surfactant peptide SP-B11–25. Biochemistry. 2002;41:9627–9636. doi: 10.1021/bi016077x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chou JJ, Kaufman JD, Stahl SJ, Wingfield PT, Bax A. Micelle-induced curvature in a water-insoluble HIV-1 Env peptide revealed by NMR dipolar coupling measurement in stretched polyacrylamide gel. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:2450–2451. doi: 10.1021/ja017875d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Munoz-Barroso I, Durell S, Sakaguchi K, Appella E, Blumenthal R. Dilation of the human immunodeficiency virus-1 envelope glycoprotein fusion pore revealed by the inhibitory action of a synthetic peptide from gp41. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:315–323. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.2.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eckert DM, Kim PS. Mechanisms of viral membrane fusion and its inhibition. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:777–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bodner ML, Gabrys CM, Parkanzky PD, Yang J, Duskin CA, Weliky DP. Temperature dependence and resonance assignment of 13C NMR spectra of selectively and uniformly labeled fusion peptides associated with membranes. Magn Reson Chem. 2004;42:187–194. doi: 10.1002/mrc.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]