Abstract

Background and purpose:

Inhibition of HERG channels prolongs the ventricular action potential and the QT interval with the risk of torsade de pointes arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Many drugs induce greater inhibition of HERG channels when the cell membrane is depolarized frequently. The dependence of inhibition on the pulsing rate may yield different IC50 values at different frequencies and thus affect the quantification of HERG channel block. We systematically compared the kinetics of HERG channel inhibition and recovery from block by 8 blockers at different frequencies.

Experimental approach:

HERG channels were expressed heterologously in Xenopus oocytes and currents were measured with the two-electrode voltage clamp technique.

Key results:

Frequency-dependent block was observed for amiodarone, cisapride, droperidol and haloperidol (group 1) whereas bepridil, domperidone, E-4031 and terfenadine (group 2) induced similar pulse-dependent block at all frequencies. With the group 1 compounds, HERG channels recovered from block in the presence of drug (recovery being voltage-dependent). No substantial recovery from block was observed with the second group of compounds. Washing out of bepridil, domperidone, E-4031 and terfenadine was substantially augmented by frequent pulsing. Mutation D540K in the HERG channel (which exhibits reopening at negative voltages) facilitated recovery from block by these compounds at −140 mV.

Conclusion and implications:

Drug molecules dissociate at different rates from open and closed HERG channels (‘use-dependent' dissociation). Our data suggest that apparently ‘trapped' drugs (group 2) dissociated from the open channel state whereas group 1 compounds dissociated from open and resting states.

Keywords: HERG, drug trapping, use-dependent block, HERG channel blocker

Introduction

The human ether-a-go-go-related gene (HERG) encodes a delayed rectifier K+ channel that plays a pivotal role during the repolarization phase of the cardiac action potential (Sanguinetti et al., 1995; Trudeau et al., 1995; Tseng, 2001; Vandenberg et al., 2001). Mutations in HERG leading to partial or complete loss of function prolong the ventricular action potential and may cause the dominantly inherited long QT syndrome with the risk of life-threatening torsade de pointes (TdP) arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death (Curran et al., 1995; Keating and Sanguinetti, 2001; Sanguinetti and Mitcheson, 2005). TdP is more often caused by drug-induced HERG channel inhibition. HERG channel block is a key factor in the pro-arrhythmic liability of a wide range of chemically diverse drugs (Redfern et al., 2003; Sanguinetti and Mitcheson, 2005). Several drugs have been withdrawn from the market or have had their use restricted because of this effect (Redfern et al., 2003; De Bruin et al., 2005). The apparent link between HERG channel block and ventricular arrhythmias has prompted extensive screening studies during drug development. The risk that a drug will induce LQT has been assessed by recording action potentials in single myocardial cells and multicellular myocardial preparations, and ECG measurements of the QT prolongation in animals (Fermini and Fossa, 2003; Recanatini et al., 2005; http://www.fda.gov/cber/gdlins/iche14qtc.htm).

An important indicator for possible arrhythmogenic liability of a given compound is the inhibition of HERG currents in heterologous expression systems. This inhibition is conventionally quantified as the concentration of half-maximal inhibition (IC50). Many HERG channel blockers exhibit a use-dependent action indicating that drug binds to open and/or inactivated channels with higher affinities than to resting channels. The level of channel block depends therefore not only on the drug concentration, but also on the pulse protocol (Kirsch et al., 2004). Also, the degree of block is considerably temperature-dependent (Kirsch et al., 2004). These factors may account for the considerable discrepancies between the IC50 values measured in different laboratories (Pearlstein et al., 2003; Kirsch et al., 2004).

Verapamil (Waldegger et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 1999), amitriptyline (Jo et al., 2000), nifekalant (Kushida et al., 2002) and trifluoperazine (Choi et al., 2005) inhibit HERG more strongly at higher frequencies. HERG channel block by the antifungal miconazole (Kikuchi et al., 2005) or dofetilide (Tsujimae et al., 2004) is facilitated by pulsing, but in a frequency-independent manner. Previous studies suggested that ‘lack of frequency dependence' could be caused by ultraslow recovery of HERG channels from block (see Tsujimae et al., 2004; Kikucki et al., 2005).

Here, we systematically analyse ‘use-dependent' block and recovery from block of HERG channels with eight known inhibitors. Four ‘group 1' compounds – amiodarone, haloperidol, droperidol and cisapride – inhibited the currents in a frequency-dependent manner and the HERG channels completely recovered from block within 1.5 to 3 min. HERG inhibition by E-4031, bepridil, domperidone and terfenadine occurred with similar kinetics at all pulse frequencies (frequency-independent block) and the channels exhibited no significant recovery at rest.

Washout of E-4031, bepridil, domperidone and terfenadine (group 2 compounds) was accelerated substantially by repetitive stimulation. Thus in addition to use-dependent binding, our data suggest the ‘use-dependent dissociation' of these drugs.

Materials and methods

Molecular biology

Preparation of stage V–VI oocytes from Xenopus laevis (NASCO, Fort Atkinson, WI, USA), synthesis of capped runoff complementary ribonucleic acid (cRNA) transcripts from linearized complementary deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA) templates and injection of cRNA were performed as described in detail by Grabner et al. (1996). cDNAs of HERG (accession number NP_000229) were kindly provided by Dr Sanguinetti (University of Utah, UT, USA).

Voltage clamp analysis

Currents through HERG channels were studied 1–2 days after microinjection of the cRNA using the two-microelectrode voltage clamp technique. The bath solution contained 96 mM sodium chloride, 2 mM potassium chloride (KCl), 1 mM magnesium chloride (MgCl2), 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.5, titrated with NaOH), 1.8 mM CaCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Taufkirchen, Germany). The D540K mutant channel was studied in low chloride solution: 96 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulphonic acid sodium salt, 2 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulphonic acid potassium salt, 1 mM CaCl2, 5 mM HEPES and 1 mM MgCl2 adjusted to pH 7.6 with methanesulphonic acid.

Voltage-recording and current-injecting microelectrodes were filled with 3 M KCl, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) and had resistances between 0.3 and 2 MΩ. Endogeneous currents (estimated in oocytes injected with water) did not exceed 0.15 μA. Currents >3 μA were discarded to minimize voltage clamp errors. A precondition for all measurements was the achievement of stable peak current amplitudes over periods of 10 min after an initial runup. All drugs were applied by means of a new perfusion system enabling solution exchange within about 100 ms (Baburin et al., 2006).

The pClamp software package version 8.0 (Axon Instruments Inc., Union City, CA, USA) was used for data acquisition. Microcal Origin 7.0 was employed for analysis and curve fitting.

Estimation of half-maximal inhibition of HERG channels

None of the compounds induced significant resting state block. The amount of inhibition during 3 min preincubation was either absent or very small (<10%). Use-dependent HERG channel block was estimated as peak tail current inhibition. The tail currents were measured at −40 mV, after a step to +20 mV. The concentration–inhibition curves were fitted using the Hill equation

where IC50 is the concentration at which HERG inhibition is half-maximal, C is the applied drug concentration, A is the fraction of HERG current that is not blocked and nH is the Hill coefficient.

Data analysis

Data points represent means±s.e. from at least three oocytes from ⩾2 batches; statistical significance of differences was defined as P<0.05 in Student's unpaired t-test.

Drugs

The studied compounds (amiodarone, bepridil, cisapride, domperidone, droperidol, E-4031, haloperidol and terfenadine (provided by the Novartis Institute for Biomedical Research, Vienna, Austria, Innovative Screening Technologies)) were dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) to prepare a 10 mM stock and stored at −20°C. Drug stocks were diluted to the required concentration in extracellular solution on the day of each experiment. The maximal DMSO concentration in the bath (0.1%) did not affect HERG currents.

Results

We investigated inhibition of HERG channels by eight known blockers during pulse trains as described in Figure 1 (see inset in Figure 1b). The voltage protocol was designed to simulate voltage changes during a cardiac action potential with a 300 ms depolarization to +20 mV (analogous to plateau phase), a repolarization for 300 ms to −40 mV (inducing a tail current) and a final step to the holding potential. The +20 mV depolarization rapidly inactivates HERG channels, thereby limiting the amount of outward current. During the repolarization to −40 mV, the previously activated channels open due to rapid recovery from inactivation. The resulting tail current amplitudes were taken as a measure of block development during a pulse train. The kinetics of peak tail current inhibition are given in pulse numbers.

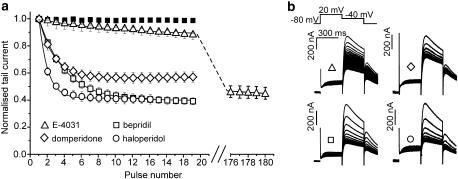

Figure 1.

Different kinetics of human ether-a-go-go-related gene (HERG) channel inhibition. (a) The development of channel inhibition by haloperidol (3 μM), bepridil (3 μM), compound E-4031 (3 μM) and domperidone (3 μM) during repetitive stimulation at a frequency of 0.3 Hz. Pulse trains were applied after a 3 min equilibration period in drug without stimulation. HERG currents were evoked by a repolarizing step to −40 mV after a 300 ms conditioning pulse to 20 mV (see inset in b). Peak HERG tail currents are plotted vs pulse number during a train. Steady-state inhibition by E-4031 was achieved after 180 pulses (see interrupted x axis) whereas steady-state block by haloperidol occurred within five pulses. (b) Representative currents illustrating the difference on rates. Ultra-slow inhibition of HERG current by E-4031 is illustrated by plotting every 10th current.

Different kinetics of HERG channel inhibition during 0.3 Hz trains of pulses by haloperidol, bepridil, domperidone and E-4031 are illustrated in Figure 1. Peak currents decayed either very slowly reaching steady-state inhibition within 180 pulses (E-4031), or rapidly within five pulses (haloperidol).

Effects of pulse frequency on HERG channel inhibition

In general, state-dependent drug action would predict enhanced HERG current inhibition during repetitive pulsing and increase of frequency is expected to deepen channel block. Indeed, Figure 2a shows stronger HERG channel inhibition by amiodarone (10 μM) at increasing frequencies (from 0.1 to 1 Hz) (see also Kiehn et al., 1999). Development of block is illustrated by plotting peak current values against pulse number at different frequencies (0.03–1 Hz, Figure 2b). Frequency-dependent inhibition was observed for cisapride (3 μM, Figure 2c; see also Walker et al., 1999), haloperidol (3 μM, Figure 2c; see also Suessbrich et al., 1997) and droperidol (2 μM, Figure 2c) (see ‘frequency-dependent drugs', Table 1, for steady-state inhibitions at different frequencies).

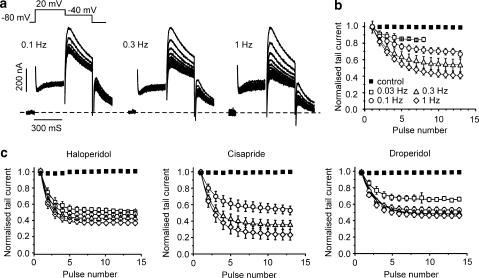

Figure 2.

Frequency-dependent human ether-a-go-go-related gene channel inhibition. (a) Representative current traces during pulse trains of indicated frequencies in the presence of amiodarone (10 μM). The voltage protocol is shown in the inset (top left). Normalized peak current values are plotted against pulse number for (b) amiodarone (10 μM) and (c) haloperidol (3 μM), cisapride (3 μM) and droperidol (2 μM). Lines represent fit to single exponential functions (Ipeak=A exp(−N/Nconst)+Iss). The steepness parameters Nconst and steady-state levels are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Rate and steady-state level of HERG channel inhibition at different frequencies (see Figures 2, 3 and 4)

| Compound | Frequency (Hz) | Rate of block (in no. of pulses) | Steady state |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amiodarone | 0.03 (n=4) | 1.45±0.25 | 0.84±0.01 |

| (10 μM) | 0.1 (n=5) | 2.56±0.23 | 0.69±0.04 |

| 0.3 (n=4) | 2.74±0.27 | 0.52±0.08 | |

| 1.0 (n=4) | 3.44±0.54 | 0.46±0.08* | |

| Haloperidol (3 μM) | 0.03 (n=3) | 1.58±0.37 | 0.50±0.08 |

| 0.1 (n=4) | 1.24±0.18 | 0.48±0.02 | |

| 0.3 (n=4) | 1.19±0.25 | 0.44±0.02 | |

| 1.0 (n=5) | 1.20±0.33 | 0.39±0.02* | |

| Cisapride (3 μM) | 0.1 (n=5) | 2.49±0.53 | 0.53±0.06 |

| 0.3 (n=4) | 1.59±0.17 | 0.37±0.06 | |

| 1.0 (n=5) | 2.05±0.38 | 0.23±0.06* | |

| Droperidol (2 μM) | 0.03 (n=6) | 2.14±0.50 | 0.66±0.25 |

| 0.1 (n=6) | 1.47±0.27 | 0.54±0.03 | |

| 0.3 (n=8) | 1.46±0.13 | 0.50±0.23 | |

| 1.0 (n=7) | 1.48±0.23 | 0.47±0.03* | |

| Bepridil (3 μM) | 0.1 (n=3) | 1.92±0.20 | 0.43±0.02 |

| 0.3 (n=3) | 3.13±0.28 | 0.40±0.02 | |

| 1.0 (n=3) | 3.16±0.31 | 0.36±0.04 | |

| E-4031 (10 μM) | 0.03 (n=3) | 29.49±6.68 | 0.25±0.05 |

| 0.1 (n=3) | 60.66±3.33 | 0.12±0.02 | |

| 1.0 (n=3) | 34.12±0.74 | 0.25±0.01 | |

| Domperidone | 0.1 (n=3) | 2.06±0.26 | 0.59±0.05 |

| (3 μM) | 0.3 (n=3) | 1.75±0.6 | 0.57±0.04 |

| 1.0 (n=3) | 1.88±0.12 | 0.49±0.03 | |

| Terfenadine (1 μM) | 0.1 (n=6) | 34.12±9.88 | 0.32±0.06 |

| 0.3 (n=4) | 28.9±5.78 | 0.42±0.02 | |

| 1.0 (n=4) | 17.53±0.31 | 0.36±0.02 |

Indicates statistically significant (P<0.05) differences between steady-state inhibition at low (0.03 or 0.1 Hz) and high (1 Hz) frequency.

A different pattern was observed for domperidone (3 μM). Figure 3a shows that over a 10-fold range of stimulation frequency (from 0.1 to 1 Hz), current inhibition remained identical. This is confirmed by the superimposed peak current decays during trains of different frequencies (Figure 3b). Bepridil (3 μM, Figure 3c), E-4031 (10 μM, Figure 3c; see also Ishii et al., 2003) and terfenadine (1 μM, Figure 3c; see also Suessbrich et al., 1996) all inhibited HERG currents to a similar extent and with similar kinetics at all frequencies (see ‘frequency-independent' blockers, Table 1).

Figure 3.

Frequency-independent human ether-a-go-go-related gene channel inhibition. (a) Representative current traces during pulse trains of indicated frequencies in the presence of domperidone (3 μM). The voltage protocol is the same as in Figure 2. Normalized peak current values are plotted vs pulse number for (b) domperidone; (c) bepridil (3 μM), E-4031 (10 μM, every 10th pulse is shown) and terfenadine (1 μM, every 10th current is shown). Lines represent fits to single exponential functions (Ipeak=A·exp(−N/Nconst)+Iss). The steepness parameters Nconst and steady-state levels are given in Table 1.

Recovery from block at rest

Gradual decay of HERG currents during a pulse train is traditionally considered to reflect the equilibration between state-dependent drug binding during depolarization and recovery at rest. To elucidate the kinetic fingerprints of the two groups (Figure 2 vs Figure 3) in more detail, we investigated the recovery processes over longer periods (Figure 4).

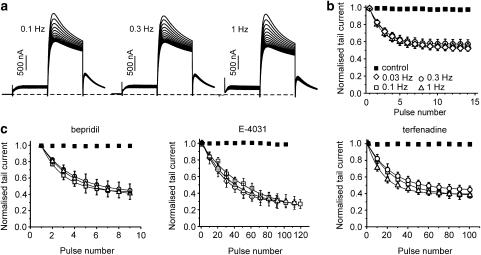

Figure 4.

Recovery of human ether-a-go-go-related gene channel from block at rest. Channel block was induced by 1 Hz pulse trains (see inset and Figure 1). Ten conditioning pulses were applied to reach steady-state inhibition by amiodarone, cisapride, haloperidol, droperidole, domperidone, bepridil. A total of 100 pulses were required for E-4031 and terfenadine. Single test pulses were applied after a 330 s rest at −80 mV. All experiments were performed in the continued presence of drug. (a) Recovery from block by 10 μM amiodarone. Superimposed current traces were elicited by the 10th pulse of the conditioning train (0 s) and a single test pulse after a 330 s rest at −80 mV. (b) Lack of recovery from block by 3 μM bepridil. Superimposed traces of the current during the 10th pulse and the test pulse after the 330 s rest period at −80 mV. (c) Recovery after 330 s from block by amiodarone (n=7), cisapride (n=9), haloperidol (n=7), droperidol (n=6), domperidone (n=3), bepridil (n=3), E-4031 (n=3) and terfenadine (n=3).

Channel block was induced by applying 1 Hz conditioning trains of different length until steady state was reached (see Figure 1). HERG currents were subsequently measured after a 330 s rest period. HERG channels recovered completely from block by amiodarone, haloperidol, droperidol and cisapride. Minor recovery was observed in the presence of E-4031 (11±0.9%), bepridil (4.3±0.5%), domperidone (15±1.2%) and terfenadine (2±0.3%), (Figure 4c).

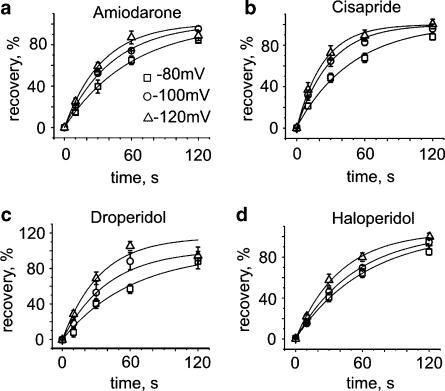

Recovery with group 1 compounds was analysed in more detail. Test pulses were applied after rest periods of 10, 30, 60, 120, 210 or 330 s at different holding potentials (Figure 5). Recovery from block was monoexponential and accelerated at more negative voltages. Amiodarone, droperidol and haloperidol dissociated with similar kinetics, while cisapride dissociated somewhat faster. The time constants at −80, −100 and −120 mV are given in Table 2.

Figure 5.

Recovery from human ether-a-go-go-related gene channel block at different holding potentials. Recovery (normalized to maximum current amplitude in drug, see a and b) plotted vs recovery time. Solid lines are mono-exponential fits for recovery (a) in 10 μM amiodarone, (b) in 3 μM cisapride, (c) in 2 μM droperidol and (d) in 3 μM haloperidol at −80, −100 and −120 mV. The time constants (τrecovery) are given in Table 2. A rest period of 5 min was introduced between each recovery protocol.

Table 2.

Time constant of recovery (s) at different holding potentials

| Holding potential (mV) | Amiodarone (10 μm) | Cisapride (3 μm) | Droperidol (2 μm) | Haloperidol (3 μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −80 | 66.4±2.8 s (n=7) | 50.7±4.2 s (n=9) | 61.5±5.6 s (n=6) | 66.4±6.1 s (n=7) |

| −100 | 46.8±3.58 s* (n=3) | 29.3±2.5 s* (n=5) | 35.8±5.1 s* (n=4) | 54.7±2.6 s* (n=5) |

| −120 | 34.3±2.1 s* (n=3) | 24.3±3.4 s* (n=6) | 26.0±2.5 s* (n=5) | 40.9±3.2 s* (n=4) |

Indicates statistically significant (P<0.05) differences compared to the respective time constant at −80 mV.

Channel activation accelerates recovery from block during ‘washout'

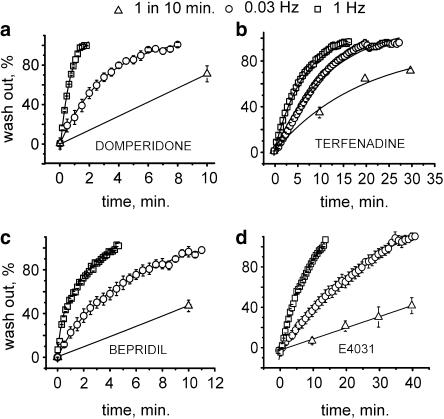

Steady-state inhibition during a pulse train reflects a balance between drug binding during channel opening and dissociation. For amiodarone, haloperidol, cisapride and droperidol, the steady state of HERG inhibition results from open channel block and subsequent recovery during the interpulse period at rest. Such a scenario is, however, unlikely for domperidone, bepridil, E-4031 and terfenadine. The lack of recovery between the individual pulses during a 0.1 Hz train suggests that the steady-state inhibition (Figure 3, Table 1) is due to drug dissociation from open channels.

We analysed whether frequent channel activation (opening) would accelerate recovery in drug-free solution during washout. Higher frequency pulsing (1 Hz) induced faster restoration of HERG currents than lower frequency pulsing (0.03 Hz). Typical experiments are illustrated in Figure 6. Repetitive activation at 1 Hz induced complete recovery during 2 min of washout of domperidone, 5 min with bepridil, 15 min with E-4031 and 17 min with terfenadine. Lower frequency stimulation (0.03 Hz) induced slower recovery during washout. If the channels were not activated (that is, remained in the closed state) we observed very slow recovery in drug-free solution (Figure 6).

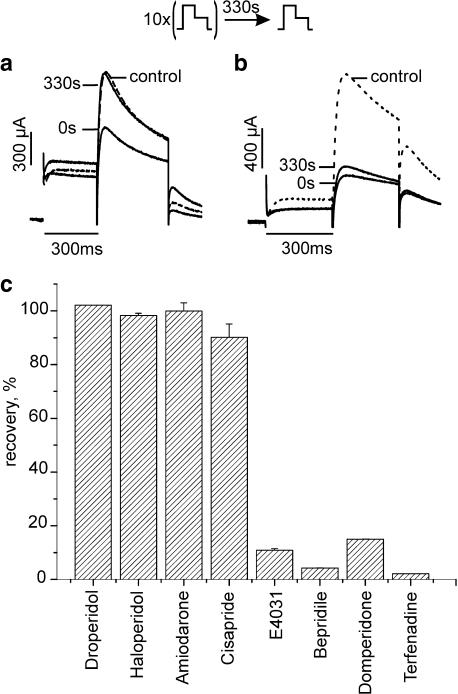

Figure 6.

Repetitive stimulation accelerates washout of group 2 compounds. (a–d) Washout at a holding potential of −80 mV during infrequent pulsing (test pulses applied with an interval of 10 min), during 0.03 Hz pulsing and frequent stimulation at 1 Hz. Peak currents were normalized to the control (the tail current amplitude before application of drug).

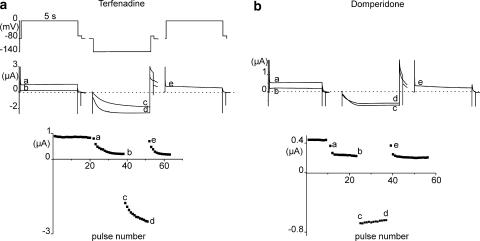

Mutation D540K enables dissociation of group 2 compounds at strong hyperpolarizations

HERG channels with the D540K mutation reopen in response to membrane hyperpolarization (Mitcheson et al., 2000). The unique gating behaviour of this mutant allows drugs that are otherwise trapped inside the central cavity to leave the reopened channel at negative potentials. To study the recovery from block by group 2 compounds, we used the voltage protocol shown at the top of Figure 7a. Voltage pulses to 0 mV (5 s duration) were repeatedly applied at 15 s intervals. After 20 depolarizing pulses to 0 mV, 20 hyperpolarizing pulses to −140 mV (5 s duration, 15 s interval) were applied in the presence of terfenadine or domperidone (Figure 7), followed by a depolarizing pulse to 0 mV to estimate recovery from block. The percentage of recovery was estimated as x=(e−b)/(a−b) × 100. The percentages of recovery were 86.5±7.3% (n=4) for terfenadine and 93.3±4.0% (n=4) for domperidone. Similar recovery levels (current traces are not shown) were observed for E-4031 (62.7±9.3%, n=4) and bepridil (68.3±10.5%, n=3).

Figure 7.

Onset and recovery from block of the human ether-a-go-go-related gene (HERG) channel mutant D540 K by 3 μM terfenadine (a) and 10 μM domperidone (b). Channel block induced by repetitive pulsing to 0 mV (20 pulses after 3 min of equilibration without pulsing) is recovered from repetitive pulsing to −140 mV. Top: voltage protocol (5 s pulses to 0 or −140 mV, applied at 15 s intervals). Middle: Representative current traces. Labels a, b: superimposed 1st and 20th traces during the train of depolarizing pulses to 0 mV. Labels c and d: 1st and 20th traces during the train of hyperpolarizing pulses to −140 mV. Label e: 1st trace after recovery. Bottom: Plot of peak outward HERG current against pulse number.

Discussion and conclusions

In the present study, we analysed the recovery kinetics of HERG after ‘use-dependent' inhibition by eight channel blockers. Amiodarone, cisapride, haloperidol and droperidol exhibited frequency-dependent block of HERG channels (Figure 2, Table 1). These drugs inhibited HERG channels more efficiently at higher stimulation frequencies. No enhancement of channel inhibition at higher frequencies was observed for bepridil, terfenadine, E-4031 and domperidone (Figure 3, Table 1). Kikuchi et al. (2005) described a similar kinetic phenotype of HERG inhibition by miconazole, with ultra-slow recovery at rest. Our data clearly show that pulse-dependent but frequency-independent HERG inhibition by bepridil, terfenadine, E-4031 and domperidone also results from ultra-slow recovery (Figure 4). These findings are in line with the hypothesis that some drug molecules (that is, group 2 compounds) are trapped by channel shutting (Armstrong, 1971; Carmeliet, 1992; Mitcheson et al., 2000). Frequent depolarizations during washout or reopening at strong hyperpolarization (mutant D540K) allowed the trapped drug molecules to leave the channel (Figures 6 and 7).

Different onset kinetics of ‘use-dependent' HERG inhibition

We observed remarkably different kinetics for development of block during pulse trains under comparable experimental conditions (that is, at drug concentrations inducing between 40 and 60% of current inhibition at the same frequency, Figure 1). Under these conditions, steady-state HERG inhibition by haloperidol and domperidone developed within 4–5 pulses, by amiodarone within 10–12 pulses, but with compound E-4031 only after more than 120 pulses. Similar steady-state levels of channel block and different kinetics point towards drug-specific rates of association and dissociation.

Evidence for drug dissociation from the open state

Several lines of evidence support the hypothesis that bepridil, domperidone, E-4031, terfenadine as well as miconazole (Kikuchi et al., 2005) fail to recover at rest but are able to dissociate from the open state. First, pulse-dependent HERG channel inhibition by miconazole (Kikuchi et al., 2005), bepridil (Figure 3), terfenadine (Figure 3; Suessbrich et al., 1996), E-4031 (Figure 3; Ishii et al., 2003) and domperidone (Figure 3) reaches similar steady-state levels at different train frequencies. If the equilibration between channel blocking and unblocking is not affected by drug dissociation at rest (see Figure 4 illustrating negligible recovery within 330 s; see also Ishii et al., 2003), then these compounds must dissociate from open HERG channels. In other words, steady-state inhibition in Figure 3 is likely to reflect the equilibrium between binding to, and dissociation from, open channels.

More evidence for open-state dissociation comes from the acceleration of washout by repetitive pulsing. Negligible recovery during washout occurred when the channels remained exclusively in the closed channel conformation (Figure 6). Channel unblocking was facilitated by repetitive pulsing at 0.03 Hz, and to a larger extent, at 1 Hz.

The data of Kamiya et al. (2006) suggest that E-4031 and bepridil are trapped inside the pore when the activation gate is shut. Reopening at negative voltages (in their study at −160 mV) allowed both compounds to dissociate. Here, we obtained similar results for terfenadine and domperidone (Figure 7) and confirmed previous findings of Kamiya et al. (2006) for bepridil and E-4031 (traces not shown).

Resting state dissociation of ‘frequency-dependent' blockers

Group 1 compounds dissociate from closed HERG channels. This is evident from Figures 4 and 5, which show recovery in the presence of drug at rest. Recovery was gradually accelerated by hyperpolarization (Table 2).

In general, group 1 compounds have two possibilities to leave the closed channel. In one scenario, the drug exits the channel only when the channel flickers to an open conformation. This scenario is unlikely. Stronger hyperpolarization decreases the probability of channel flickering to an open conformation. Figure 5 shows, however, facilitation of channel unblocking at more hyperpolarized voltages.

In a second scenario, channel closure does not completely trap the drug (‘foot in the door' mechanism; Armstrong, 1971) but it presents a barrier that the drug must pass before dissociation. Our data support such a hypothesis, in which (presumably bulky) gate structures create a barrier resulting in pronounced voltage dependence of drug dissociation. In other words, larger voltage drops across the closed channel gates apparently ease the release of the charged group 1 compounds from the closed HERG channel state.

Drug trapping

Kamiya et al. (2006) suggest that gating structures may trap drug molecules during channel closure. Ultra-slow recovery from block at rest has been observed previously in cardiac myocytes for IKr block by methanesulphonanilides (dofetilide, MK-499; Carmeliet, 1992). More direct evidence for drug trapping was provided by Mitcheson et al. (2000), using the HERG mutant D540K, which reopens during pronounced hyperpolarization, thereby accelerating recovery from block. Similar observations were made for propafenone (Witchel et al., 2004). Interestingly, even strong hyperpolarizations do not facilitate recovery of frequency-independent blockers from wild-type channels (for example, bepridil and E-4031; Kamiya et al., 2006).

A significant acceleration of the washout of these compounds by repetitive stimulation as described for bepridil, terfenadine, E-4031 and domperidone in the present study supports the view that trapped drugs may leave the open channel at depolarized voltages. At the moment it is not clear why some drugs are unable to leave the closed channel state but other compounds dissociate. Hence, similar residues were found to be crucial for binding of cisapride and terfenadine (Sanguinetti and Mitcheson, 2005). Cisapride belongs, however, to the group of frequency-dependent blockers, while terfenadine dissociates with ultra-slow kinetics resulting in frequency-independent block (Table 1).

We calculated several descriptors related to size, volume, lipophilicity and accessible surface (data not shown). Irrespective of the descriptor, amiodarone and terfenadine always were similar in values. No trend that would allow to group the compounds into trapped/non-trapped on basis of one of the descriptors could be observed. However, the group of compounds tested is by far too small and structurally too heterogeneous to draw quantitative conclusions. A study using a systematically modified set of compounds is currently in progress.

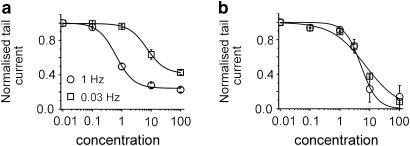

Impact on IC50 estimation

Four compounds (amiodarone, cisapride, haloperidol and droperidol) were found to block HERG channels in a frequency-dependent manner and four others (bepridil, terfenadine, E-4031 and domperidone) inhibited the currents to a similar degree and with similar kinetics at all frequencies. Figure 8 illustrates the consequences for quantification of drug/channel interactions. Amiodarone belongs to group 1 (frequency-dependent) and domperidone to group 2 (frequency-independent). The concentration/inhibition curves for both compounds were measured with pulse trains of either 0.03 or 0.3 Hz. The IC50 values of HERG current inhibition for amiodarone were 7.2±2.05 μM at 0.03 Hz and 1.1±0.65 μM at 0.3 Hz. The IC50 values for domperidone were similar at both frequencies (≈5 μM). Thus, among other factors such as temperature and pulse pattern (Kirsch et al., 2004), the frequency of membrane depolarization may or may not affect the estimation of IC50 values.

Figure 8.

Concentration/inhibition curves for the frequency-dependent inhibitor amiodarone (a) and the frequency-independent inhibitor domperidone (b). Human ether-a-go-go-related gene currents were evoked by either 0.03 or 1 Hz trains. Steady-state values of peak tail current are plotted against drug concentration. The IC50 values for amiodarone were 7.17±2.05 μM, nH=1.4, (0.03 Hz) and 1.08±0.65 μM, nH=1.43 (0.3 Hz). The corresponding values for domperidone were 4.6±1.4 μM, nH=2.29 (0.03 Hz) and 5.6±0.4 μM, nH=1.47 (0.3 Hz).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF P15914-B05) and a research grant from NOVARTIS AG. We thank MC Sanguinetti for providing the HERG clone and mutant D540K. We thank G Ecker for quantitative structure–activity relationship analysis of drug structures.

Abbreviations

- cDNA

complementary deoxyribonucleic acid

- cRNA

complementary ribonucleic acid

- HERG

human ether-a-go-go related gene

- KMes

2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulphonic acid potassium salt

- LQTS

long QT syndrome

- NaMes

2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulphonic acid sodium salt

- nH

Hill coefficient

- QSAR

quantitative structure–activity relationship

- TdP

torsade de pointes

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Armstrong CM. Interaction of tetraethylammonium ion derivatives with the potassium channels of giant axon. J Gen Physiol. 1971;58:413–437. doi: 10.1085/jgp.58.4.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baburin I, Beyl S, Hering S. Automated fast perfusion of Xenopus oocytes for drug screening. Pflügers Arch. 2006;453:117–123. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0125-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet E. Voltage- and time-dependent block of the delayed K+ current in cardiac myocytes by dofetilide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;262:809–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SY, Koh YS, Jo SH. Inhibition of human ether-a-go-go-related gene K+ channel and IKr of guinea pig cardiomyocytes by antipsychotic drug trifluoperazine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:888–895. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.080853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran ME, Splawski I, Timothy KW, Vincent GM, Green ED, Keating MT. A molecular basis for cardiac arrhythmia: HERG mutations cause long QT syndrome. Cell. 1995;80:795–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bruin ML, Pettersson M, Meyboom RH, Hoes AW, Leufkens HG. Anti-HERG activity and the risk of drug-induced arrhythmias and sudden death. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:590–597. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fermini B, Fossa AA. The impact of drug-induced QT interval prolongation on drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:439–447. doi: 10.1038/nrd1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabner M, Wang Z, Hering S, Striessnig J, Glossmann H. Transfer of 1,4-dihydropyridine sensitivity from L-type to class A (BI) calcium channels. Neuron. 1996;16:207–218. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii K, Nagai M, Takahashi M, Endoh M. Dissociation of E-4031 from the HERG channel caused by mutations of an amino acid results in greater block at high stimulation frequency. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:651–659. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00774-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo SH, Youm JB, Lee CO, Earm YE, Ho WK. Blockade of the HERG human cardiac K+ channel by the antidepressant drug amitriptyline. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:1474–1480. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya K, Niwa R, Mitcheson JS, Sanguinetti MC. Molecular determinants of HERG channel block. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1709–1716. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.020990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating MT, Sanguinetti MC. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias. Cell. 2001;104:569–580. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehn J, Thomas D, Karle CA, Schols W, Kubler W. Inhibitory effects of the class III antiarrhythmic drug amiodarone on cloned HERG potassium channels. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1999;359:212–219. doi: 10.1007/pl00005344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi K, Nagatomo T, Abe H, Kawakami K, Duff HJ, Makielski JC, et al. Blockade of HERG cardiac K+ current by antifungal drug miconazole. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;144:840–848. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch GE, Trepakova ES, Brimecombe JC, Sidach SS, Erickson HD, Kochan MC, et al. Variability in the measurement of HERG potassium channel inhibition: effects of temperature and stimulus pattern. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2004;50:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushida S, Ogura T, Komuro I, Nakaya H. Inhibitory effect of the class III antiarrhythmic drug nifekalant on HERG channels: mode of action. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;457:19–27. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02666-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitcheson JS, Chen J, Lin M, Culberson C, Sanguinetti MC. A structural basis for drug-induced long QT syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12329–12333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.210244497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlstein R, Vaz R, Rampe D. Understanding the structure-activity relationship of the human ether-a-go-go-related gene cardiac K+ channel. A model for bad behavior. J Med Chem. 2003;46:2017–2022. doi: 10.1021/jm0205651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recanatini M, Poluzzi E, Masetti M, Cavalli A, De Ponti F. QT prolongation through HERG K+ channel blockade: current knowledge and strategies for the early prediction during drug development. Med Res Rev. 2005;25:133–166. doi: 10.1002/med.20019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfern WS, Carlsson L, Davis AS, Lynch WG, Mackenzie I, Palethorpe S, et al. Relationships between preclinical cardiac electrophysiology, clinical QT interval prolongation and torsade de pointes for a broad range of drugs: evidence for a provisional safety margin in drug development. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;58:32–45. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00846-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti MC, Jiang C, Curran ME, Keating MT. A mechanistic link between an inherited and an acquired cardiac arrhythmia: HERG encodes the IKr potassium channel. Cell. 1995;81:299–307. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti MC, Mitcheson JS. Predicting drug-HERG channel interactions that cause acquired long QT syndrome. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suessbrich H, Waldegger S, Lang F, Busch AE. Blockade of HERG channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes by the histamine receptor antagonists terfenadine and astemizole. FEBS Lett. 1996;385:77–80. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suessbrich H, Schönherr R, Heinemann SH, Attali B, Lang F, Busch AE. The inhibitory effect of the antipsychotic drug haloperidol on HERG potassium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:968–974. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudeau MC, Warmke JW, Ganetzky B, Robertson GA. HERG, a human inward rectifier in the voltage-gated potassium channel family. Science. 1995;269:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.7604285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng GN. IKr: the HERG channel. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:835–849. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimae K, Suzuki S, Yamada M, Kurachi Y. Comparison of kinetic properties of quinidine and dofetilide block of HERG channels. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;493:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg JI, Walker BD, Campbell TJ. HERG K+ channels: friend and foe. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:240–246. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01662-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldegger S, Niemeyer G, Morike K, Wagner CA, Suessbrich H, Busch AE, et al. Effect of verapamil enantiomers and metabolites on cardiac K+ channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Cell Physiol Biochem. 1999;9:81–89. doi: 10.1159/000016304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker BD, Singleton CB, Bursill JA, Wyse KR, Valenzuela SM, Qiu MR, et al. Inhibition of the human ether-a-go-go-related gene (HERG) potassium channel by cisapride: affinity for open and inactivated states. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:444–450. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witchel HJ, Dempsey CE, Sessions RB, Perry M, Milnes JT, Hancox JC, et al. The low-potency, voltage-dependent HERG blocker propafenone--molecular determinants and drug trapping. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:1201–1212. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.001743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Zhou Z, Gong Q, Makielski JC, January CT. Mechanism of block and identification of the verapamil binding domain to HERG potassium channels. Circ Res. 1999;84:989–998. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.9.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]