Abstract

Background and purpose:

Cholecystokinin is known to exert stimulant actions on intestinal motility via activation of type 1 cholecystokinin receptors (CCK1). However, the role played by cholecystokinin 2 (CCK2) receptors in the regulation of gut motility remains undetermined. This study was designed to examine the influence of CCK2 receptors on the contractile activity of human distal colon.

Experimental approach:

The effects of compounds acting on CCK2 receptors were assessed in vitro on motor activity of longitudinal smooth muscle, under basal conditions as well as in the presence of KCl-induced contractions or transmural electrical stimulation.

Key results:

Cholecystokinin octapeptide sulphate induced concentration-dependent contractions which were enhanced by GV150013 (CCK2 receptor antagonist; +57% at 0.01 μM). These effects were unaffected by tetrodotoxin. The enhancing actions of GV150013 on contractions evoked by cholecystokinin octapeptide sulphate were unaffected by Nω-propyl-L-arginine (NPA, neuronal nitric oxide synthase inhibitor), while they were prevented by Nω-nitro-L-arginine methylester (L-NAME, non-selective nitric oxide synthase inhibitor). In the presence of KCl-induced contractions, cholecystokinin octapeptide sulphate elicited concentration-dependent relaxations (-36%), which were unaffected by NPA, but were counteracted by GV150013 or L-NAME. The application of electrical stimuli evoked phasic contractions which were enhanced by GV150013 (+41 % at 0.01 μM).

Conclusions and implications:

CCK2 receptors mediate inhibitory actions of cholecystokinin on motor activity of human distal colon. It is suggested that CCK2 receptors exert their modulating actions through a nitric oxide pathway, independent of the activity of the neuronal nitric oxide synthase isoform.

Keywords: cholecystokinin, CCK2 receptors, human colon, intestinal motility, nitric oxide

Introduction

Cholecystokinin (CCK) regulates a variety of physiological functions acting as a neuropeptide in the central nervous system (CNS) and as both hormone and neurotransmitter in the gastrointestinal tract (Crawley and Corwin, 1994; Miyasaka and Funakoshi, 2003). Several studies, based on functional, pharmacological and molecular approaches, have indicated that the regulatory actions of CCK are mediated by two receptor subtypes, designated as CCK1 and CCK2. CCK1 receptors are mainly located in the gut and in few areas of the CNS. CCK2 receptors are widely expressed in the CNS as well as in the digestive tract, where they are mainly located in the stomach, but can also be found throughout the small and large intestines (Noble et al., 1999; Miyasaka and Funakoshi, 2003).

CCK and its related peptides have been implicated in the pathophysiology of functional digestive diseases, such as irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia. Previous studies suggested that either an altered release of CCK or abnormal responses to this peptide could contribute to symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (Sjolund et al., 1996; Chey et al., 2001). In particular, CCK may take part in the development of digestive symptoms, such as abdominal discomfort, pain and altered sensations to luminal stress (Chua and Keeling, 2006). On this basis, the pharmacological modulation of CCK pathways might be useful for treatment of symptoms associated with functional digestive disorders (Herranz, 2003).

In the gastrointestinal tract, CCK1 receptors have been localized in the smooth muscle and myenteric neurons as well as abdominal afferent nerves (Sternini et al., 1999), and they appear to be mainly involved in the control of gut motility and visceral sensation (Noble et al., 1999; Varga et al., 2004). The main functions regulated by CCK2 receptors in the digestive system include the stimulation of acid secretion from parietal cells (Kulaksiz et al., 2000; Ochi et al., 2005) and the release of histamine from enterochromaffin-like cells in the stomach (Waldum et al., 2002), but it has been suggested that these receptors might also contribute to the control of gut motor functions (Dal Forno et al., 1992; Giralt and Vergara, 1999).

CCK actions on intestinal motility can vary in nature, depending on the species and gut region examined. In general, direct effects of CCK on smooth muscle are thought to result in contractile responses, whereas neurally mediated actions can evoke either contractile or relaxant activity, depending on the transmitter being released (Varga et al., 2004). Studies in guinea pigs showed that CCK can stimulate intestinal motor activity through recruitment of CCK1 receptors located on smooth muscle or myenteric nerve pathways (Dal Forno et al., 1992; Fornai et al., 2007). In addition, following the development of non-peptidic CCK2 receptor antagonists (Herranz, 2003), in vivo studies with canine or rat models suggested the involvement of these receptors in the inhibitory control of gut motor functions (Vergara et al., 1996; Giralt and Vergara, 1999) and, more recently, Fornai et al. (2007) observed that CCK inhibits the motility of isolated guinea-pig colon via activation of CCK2 receptors leading to nitric oxide (NO) release from myenteric nerves.

When considering the effects of CCK on human gut, current evidence indicates that CCK induces contractions of colon and that these stimulant actions are mediated by CCK1 receptors located on smooth muscle (D'Amato et al., 1991; Morton et al., 2002a). However, the possible involvement of CCK2 receptors in the control of human bowel motility has not been previously demonstrated. Accordingly, the present study was designed to investigate the in vitro effects of compounds acting at CCK2 receptors on both spontaneous and stimulated human colonic motility.

Methods

Tissue excision and preparation

Colonic specimens were obtained from patients undergoing surgery for uncomplicated neoplastic conditions. Patients not older than 60 years, without history of gastrointestinal inflammatory diseases, digestive functional disorders, abdominal surgery or intestinal obstruction, were selected. Samples consisted of whole wall sections of distal colon from a macroscopically normal region taken at a distance of at least 10 cm from any visible lesion. Care was taken to verify the absence of alterations by histological examination. Portions of tissue were fixed in cold 4% paraformaldehyde, diluted in phosphate-buffered saline, for routine histology. The remaining parts of colonic tissues were placed into pre-oxygenated Krebs solution and transported on ice to laboratory. Longitudinal muscle strips of approximately 3 mm width and 20 mm length were prepared as described previously (Fornai et al., 2005). Informed patient consent was obtained before surgery, and the experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of our University Hospital.

Recording of longitudinal muscle contractile activity

The contractile activity of colonic longitudinal smooth muscle was recorded as described previously by Fornai et al. (2005). Preparations were set up in 10-ml organ baths containing Krebs solution at 37°C, bubbled with 95% O2+5% CO2. Preparations were connected to isotonic transducers (Basile, Comerio, Italy), under a constant load of 1 g, and allowed to equilibrate for at least 30 min. Krebs solution had the following composition (mM): NaCl 113, KCl 4.7, CaCl2 2.5, KH2PO4 1.2, MgSO4 1.2, NaHCO3 25, glucose 11.5 (pH 7.4±0.1). Longitudinal muscle activity was recorded by polygraphs (Basile, Comerio, Italy). Transmural electrical stimulation was delivered by a BM-ST6 stimulator (Biomedica Mangoni, Pisa, Italy). Stimuli were applied as 10-s single trains of square wave pulses (0.5 ms, 30 mA) at 10 Hz. The interval between successive periods of electrical stimulation was about 30 min. Each preparation was repeatedly challenged with electrical stimulations, and experiments started when reproducible responses were obtained (usually after 2–3 stimulations).

In the first set of experiments, the effects of CCK octapeptide sulphate (CCK-8S) were evaluated on spontaneous motor activity of colonic preparations. For this purpose, non-cumulative concentration–response curves were constructed for CCK-8S (0.001–1 μM) on basal contractility of longitudinal muscle. In the second set, the effect of CCK-8S (0.1 μM) was examined on spontaneous colonic activity after incubation with increasing concentrations of the selective CCK2 receptor antagonist GV150013 (0.001–0.1 μM).

To investigate whether CCK2 receptors regulate colonic motility at neural and/or muscular level, the effects of CCK-8S and its interaction with GV150013 (0.01 μM) were also assessed after blockade of myenteric nerves. For this purpose, colonic tissues were maintained in Krebs solution containing tetrodotoxin (1 μM). In addition, to evaluate the involvement of NO in the effects mediated by CCK2 receptors, CCK-8S was assayed on colonic preparations maintained in Krebs solution containing the non-selective NO synthase (NOS) inhibitor Nω-nitro-L-arginine methylester (L-NAME, 100 μM) or the selective neuronal NOS (nNOS) inhibitor Nω-propyl-L-arginine (NPA, 0.1 μM). In a separate group of experiments, colonic preparations were pre-contracted with KCl (60 mM). Under these conditions, the effect of CCK-8S was assessed either alone or in the presence of GV150013 (0.01 μM), NPA (0.1 μM) or L-NAME (100 μM). In the final set of experiments, the effects of GV150013 were assayed on contractile responses induced by electrical stimulation, applied as reported above.

In all experiments, CCK-8S was added to the organ bath solution at 20-min intervals, and the exposure time never exceeded 2 min, to avoid desensitization. The CCK2 antagonist was added to the bathing fluid 25 min before the application of CCK-8S or electrical stimulation. Concentration–response curves were obtained from distinct preparations obtained from the same patient.

Statistical analysis

Results are given as mean±standard error of mean (s.e.m.). The significance of differences was evaluated on raw data, before percentage normalization, by analysis of variance for repeated measures or unpaired data, followed by post hoc analysis with Dunnett or Student–Newman–Keuls test, as appropriate. P<0.05 was considered significant. Colonic preparations included in each test group were obtained from distinct patients and therefore the number of experiments refers also to the number of patients assigned to each group. EC50 values were interpolated from concentration–response curves and variability was expressed as 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Calculations were performed using commercial software (GraphPad Prism, version 3.0 from GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Drugs and reagents

Human CCK octapeptide sulphate, L-NAME (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO, USA); tetrodotoxin, NPA (Tocris Cookson, Bristol, UK); devazepide (kindly provided by Merck Sharp and Dohme, UK); GV150013 [N-(+)-[1-adamant-1-ylmethyl)-2,4-dioxo-5-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-1,5-benzodiazepin-3-yl]-N phenylurea] (kindly provided by Glaxo-Wellcome, Verona, Italy). CCK-8S was dissolved in physiological saline. GV150013 was dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide and further dilutions were made with saline solution. Dimethyl sulphoxide concentration in organ bath never exceeded 0.5%.

Results

Before performing experiments on colonic contractions, care was taken to verify the presence of CCK receptors in the experimental model. By means of the reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, evidence was obtained that mRNAs coding for both CCK1 and CCK2 receptors were expressed in preparations of human colon longitudinal muscle (data not shown).

Studies on CCK-8S-induced motor activity

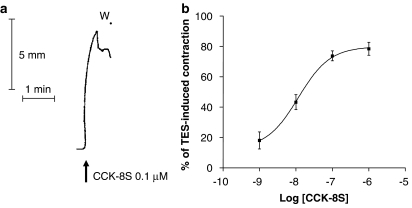

During the equilibration period, colonic preparations developed a spontaneous motor activity which appeared low in amplitude and, in most cases, remained stable throughout the experimental period. The application of CCK-8S (0.001–1 μM) to the bathing fluid induced contractions of longitudinal smooth muscle (Figure 1a). The construction of concentration–response curves for the contractile responses elicited by CCK-8S provided an estimate of the maximal effect, equivalent to 78.4±4.3% of electrically-evoked contraction, at the concentration of 1 μM, with a mean EC50 value of 11.7 nM (95% CI 3–49 nM) (Figure 1b). The stimulant actions of CCK-8S on colonic contractions were not modified by tetrodotoxin (1 μM) (Figure 2c), but they were significantly reduced by the CCK1 receptor antagonist devazepide (0.01–1 μM) (data not shown), consistently with the notion that CCK1 receptors mediate direct effects of CCK on human colonic smooth muscle (D'Amato et al., 1991).

Figure 1.

(a) Representative tracing showing the effect of CCK-8S (0.1 μM) on the contractile activity of longitudinal smooth muscle isolated from distal colon. (b) Effects of increasing concentrations of CCK-8S (0.001–1 μM) on the motor activity of longitudinal smooth muscle. CCK-induced contractions were expressed as % of the contraction induced by transmural electrical stimulation (TES). Each point represents the mean of 6–8 experiments±s.e.m. (vertical bars). CCK-8S, CCK octapeptide sulphate.

Figure 2.

(a) Representative tracings showing the effects of GV150013 (0.01 μM) on contractions evoked by CCK-8S (0.1 μM). (b) Effects of increasing concentrations of GV150013 (0.001–0.1 μM) on the contractile responses elicited by CCK-8S (0.1 μM). (c) Representative trace recordings showing the effects of CCK-8S (0.1 μM), in the absence or in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1 μM), on colonic longitudinal smooth muscle, and the effects of GV150013 (0.01 μM) on the contractile responses induced by CCK-8S in the presence of TTX. (d) Effects of TTX or TTX plus GV150013 on CCK-8S-induced contractions. Each column represents the mean of 6–8 experiments±s.e.m. (vertical bars). *P<0.05, significant difference vs CCK-8S alone. CCK-8S, CCK octapeptide sulphate; W, wash.

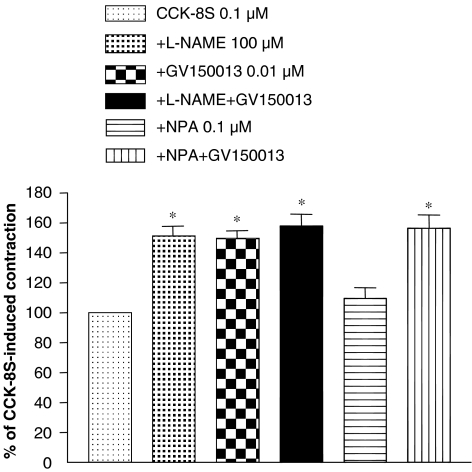

The incubation of colonic tissues with GV150013 (0.001–0.1 μM) did not affect the spontaneous motor activity (data not shown). However, in the presence of GV150013, CCK-8S-evoked contractions were enhanced in a concentration-dependent fashion (Figures 2a and b). In addition, the enhancing effect of GV150013 (0.01 μM) on the motor responses evoked by CCK-8S (0.1 μM) was unaffected when colonic preparations were incubated with tetrodotoxin (1 μM) (Figures 2c and d). In colonic tissues maintained in Krebs solution containing the non-selective NOS inhibitor L-NAME (100 μM), contractions induced by CCK-8S (0.1 μM) were significantly increased. Under these conditions, the enhancing effects of GV150013 (0.01 μM) no longer occurred. By contrast, the selective nNOS inhibitor NPA (0.1 μM) did not influence the CCK-8S-evoked contractions and, in the presence of NPA, GV150013 was still able to enhance the motor responses elicited by CCK-8S (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effects of L-NAME (100 μM), GV150013 (0.01 μM), L-NAME plus GV150013, NPA (0.1 μM) or NPA plus GV150013 on the contractile responses evoked by CCK-8S (0.1 μM) in longitudinal smooth muscle preparations isolated from human distal colon. Each column represents the mean of seven to eight experiments±s.e.m. (vertical bars). *P<0.05, significant difference vs CCK-8S alone. CCK-8S, CCK octapeptide sulphate; L-NAME, Nω-nitro-L-arginine methylester; NPA, Nω-propyl-L-arginine.

Studies on tissues precontracted with KCl

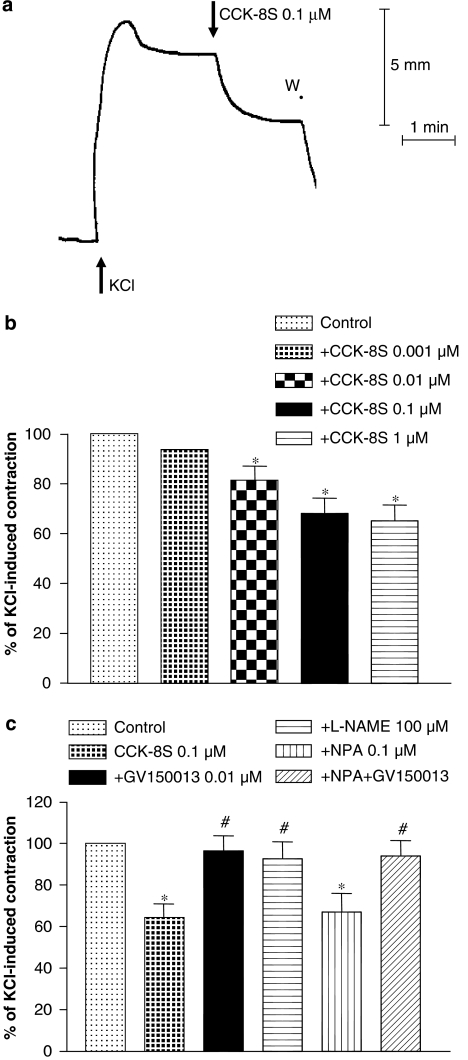

The exposure of colonic preparations to KCl (60 mM) induced a fast phasic contraction followed by a period of sustained contraction which, in most cases, remained stable for at least 5 min (Figure 4a). The amplitude of the sustained contractions was equivalent to 85.5±6.4% of contractile responses evoked by electrical stimulation. Under these conditions, CCK-8S (0.001–1 μM) elicited concentration-dependent relaxations of smooth muscle (Figures 4a and b). Preincubation of colonic tissues with GV150013 (0.01 μM) did not alter contractions evoked by KCl (data not shown). However, the relaxant responses evoked by CCK-8S were completely prevented by GV150013 (Figure 4c). The relaxant effects induced by CCK-8S were counteracted by L-NAME (100 μM), but not by NPA (0.1 μM) (Figure 4c). Moreover, in the presence of NPA, the blunting effect of GV150013 on CCK-8S-induced relaxations was unaffected (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

(a) Representative tracing showing the effect of CCK-8S (0.1 μM) on the motor activity of human colonic longitudinal smooth muscle pre-contracted with KCl (60 mm). (b) Effects of increasing concentrations of CCK-8S (0.001–1 μM) on KCl-induced contractions. (c) Effects of GV150013 (0.01 μM), L-NAME (100 μM), NPA (0.1 μM) or NPA plus GV150013 on the relaxant effects of CCK-8S in colonic preparations pre-contracted with KCl. Each column represents the mean of seven to eight experiments±s.e.m. (vertical bars). *P<0.05, significant difference vs control. #P<0.05, significant difference vs CCK-8S. CCK-8S, CCK octapeptide sulphate; L-NAME, Nω-nitro-L-arginine methylester; NPA, Nω-propyl-L-arginine; W, wash.

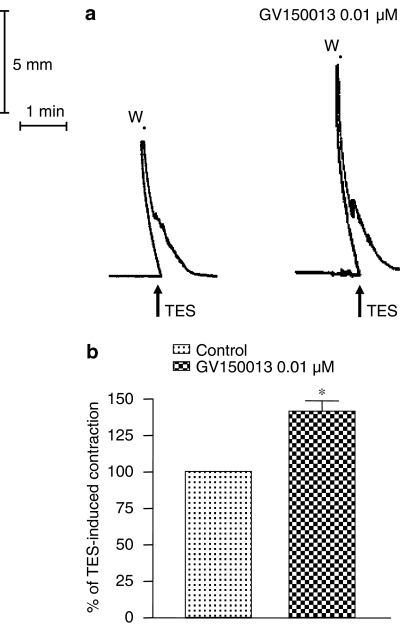

Studies on electrically-evoked contractions

The application of electrical stimulation to colonic preparations evoked reproducible phasic contractions (Figure 5a), which were prevented by tetrodotoxin (1 μM) (data not shown). The contractile responses elicited by electrical stimulation were significantly enhanced by GV150013 (0.01 μM) (Figures 5a and b).

Figure 5.

(a) Representative tracings showing the effects of transmural electrical stimulation (TES, 1 ms, 30 mA, 10 Hz, 100 pulses) on the motor activity of human colonic longitudinal smooth muscle, either alone or in the presence of GV150013 (0.01 μM). (b) Effects of GV150013 (0.01 μM) on the contractile responses induced by TES. Each column represents the mean of eight experiments±s.e.m. (vertical bars). *P<0.05, significant difference vs control.

Discussion

In recent years, a number of studies have evaluated the effects of CCK receptor ligands on gastrointestinal motor functions, as these agents might represent novel pharmacological tools for the management of symptoms associated with functional digestive disorders (Varga et al., 2004; Galligan and Vanner, 2005). In view of these premises, the present study was performed to characterize the role played by CCK2 receptors in the control of motor activity in human distal colon. Before addressing this issue, we confirmed the findings of previous reports indicating that both CCK1 and CCK2 receptors are expressed in the muscular compartment of human colon (Rettenbacher and Reubi, 2001; Morton et al., 2002b), and that CCK analogues are able to induce tetrodotoxin-insensitive colonic contractions, which can be counteracted by selective CCK1 receptor antagonists (D'Amato et al., 1991; Morton et al., 2002a).

After verification of previous available information, in the present study a series of functional experiments was designed to assay the effects of compounds acting at CCK2 receptors on the contractile activity of human colon. The results showed that CCK-8S elicited contractile responses that were enhanced by GV150013, either in the absence or in the presence of tetrodotoxin, thus suggesting that CCK2 receptors mediate inhibitory effects that do not seem to involve the recruitment of neural pathways. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first evidence demonstrating inhibitory effects mediated by CCK2 receptors on human colonic longitudinal smooth muscle, as previous studies have reported excitatory effects mediated by CCK1 receptors in this tissue. Morton et al. (2002a) examined the effects of a CCK2 receptor antagonist, JB93182, on human colon in vitro, and observed that this compound did not influence CCK-8S-induced contractions. However, Morton et al. (2002a) performed their experiments on preparations of circular smooth muscle, which were isolated from the ascending colon and connected to isometric force transducers. These experimental variables are not directly comparable with those adopted in our study with longitudinal smooth muscle isolated from descending colon and connected to isotonic transducers.

The present experiments showed that the enhancing effect of GV150013 on motor responses evoked by CCK-8S were still evident in the presence of NPA, but not L-NAME. These findings allow us to hypothesize that CCK2 receptors mediated their inhibitory actions in the distal colon through the release of NO, which did not appear to be generated by the nNOS isoform. To clarify this mechanism further, CCK-8S was tested on colonic preparations maintained under sustained contraction with KCl. In this setting, CCK-8S elicited concentration-dependent relaxations, which were antagonized by GV150013 or L-NAME, but not by NPA, thus providing further evidence that CCK2 receptors can modulate human colonic motility via NO release, independent of nNOS activity.

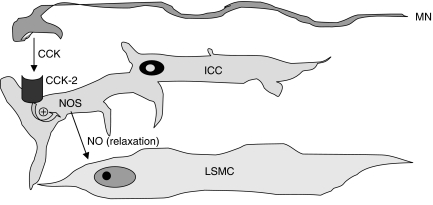

The existence of NO pathways regulated by CCK2 receptors in the muscular compartment of human colon has not been previously demonstrated and represents a major novel finding of the present study. Consistent with this proposal, previous reports indicated that NOS is expressed in digestive smooth muscle cells of rabbits and humans and that smooth muscle represents a major source of NO at enteric level (Jin et al., 1996; Teng et al., 1998). Other investigations demonstrated that NOS is expressed in interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) of mouse colon (Vannucchi et al., 2002), and there is evidence to suggest that ICC contribute significantly to the NO-dependent modulation of canine colonic motility (Publicover et al., 1993). A more recent study indicated also that the administration of L-NAME to normal rats caused an increase in colonic motility, whereas in transgenic rats lacking ICC this effect no longer occurred, suggesting that NO is involved in the regulatory actions exerted by ICC on colonic motility (Takahashi et al., 2005). These observations, together with the fact that CCK2 receptors have been found expressed mostly in ICC of human colon (Rettenbacher and Reubi, 2001), support the view that the inhibitory actions mediated by CCK2 receptors on colonic motility, as shown in the present study, might be driven by NO release from enteric cells, which are likely to correspond to ICC (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram summarizing the proposed modulating actions exerted by the CCK2 receptor subtype on the motor activity of human colonic longitudinal smooth muscle. CCK2 receptors are localized on ICC and are activated by neurally released CCK. CCK2 receptors then stimulate NOS activity, with subsequent NO release and relaxation of smooth muscle cells. CCK, cholecystokinin; ICC, interstitial cell of Cajal; LSMC, longitudinal smooth muscle cell; MN, myenteric neuron; NO, nitric oxide; NOS, nitric oxide synthase.

An important point to consider is the cellular source(s) of CCK-related peptides responsible for the recruitment of CCK receptor pathways. Indeed, at gastrointestinal level CCK can be produced and released by endocrine I cells in the duodenal wall or by intramural peptidergic neurons located within myenteric plexus of small intestine and colon (Liddle, 1997; Rehfeld, 2004; Varga et al., 2004). In the present study, an attempt was made to verify whether CCK2 receptors of distal colon can be activated by CCK of neuronal origin. For this purpose, a subset of experiments was performed on colonic preparations subjected to electrical stimulation to elicit contractile events mediated by the release of neural transmitters. Since, in our hands, electrical stimulation evoked tetrodotoxin-sensitive contractile responses, which were enhanced by GV150013, it can be suggested that CCK2 receptors involved in the inhibitory control of colonic motility are likely to interact mainly with CCK-like peptides released from enteric nerves (Figure 6).

In conclusion, the present results indicate that CCK2 receptors mediate inhibitory actions of CCK on motor functions of human distal colon. In particular, CCK seems to act via CCK2 receptors to induce relaxant responses mediated by recruitment of NO-dependent pathways. In view of these findings, the isolated human distal colon can be regarded as a suitable model to assay the intestinal motor effects of novel drugs designed to interact with CCK2 receptors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Massimo D'Amato (Rotta Research Laboratorium S.p.A., Monza, Italy) for his expert and critical review of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CCK

cholecystokinin

- CCK1

cholecystokinin 1 receptor subtype

- CCK2

cholecystokinin 2 receptor subtype

- CNS

central nervous system

- GV150013

N-(+)-[1-adamant-1-ylmethyl)-2,4-dioxo-5-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-1,5-benzodiazepin-3-yl]-N phenylurea

- ICC

interstitial cells of Cajal

- L-NAME

Nω-nitro-L-arginine methylester

- nNOS

neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- NPA

Nω-propyl-L-arginine

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest

References

- Chey WY, Jin HO, Lee MH, Sun SW, Lee KY. Colonic motility abnormalities in patients with irritable bowel syndrome exhibiting abdominal pain and diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1499–1506. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua ASB, Keeling PWN. Cholecystokinin hyperresponsiveness in functional dyspepsia. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2688–2693. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i17.2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley JN, Corwin RL. Biological actions of cholecystokinin. Peptides. 1994;15:731–755. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(94)90104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Forno G, Pietra C, Urciuoli M, Van Amsterdam FT, Toson G, Gaviraghi G, et al. Evidence for two cholecystokinin receptors mediating the contraction of the guinea pig isolated ileum longitudinal muscle myenteric plexus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;261:1056–1063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amato M, Stanford IF, Bennett A. Studies of three non-peptide cholecystokinin antagonists (devazepide, lorglumide and loxiglumide) in human isolated alimentary muscle and guinea-pig ileum. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;102:391–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornai M, Blandizzi C, Colucci R, Antonioli L, Bernardini N, Segnani C, et al. Role of cyclooxygenase 1 and 2 in the modulation of neuromuscular functions in the distal colon of humans and mice. Gut. 2005;54:608–616. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.053322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornai M, Colucci R, Antonioli L, Baschiera F, Ghisu N, Tuccori M, et al. CCK2 receptors mediate inhibitory effects of cholecystokinin on the motor activity of guinea-pig distal colon. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;557:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galligan JJ, Vanner S. Basic and clinical pharmacology of new motility promoting agents. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:643–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giralt M, Vergara P. Both afferent and efferent nerves are implicated in cholecystokinin motor actions in the small intestine of the rat. Regul Pept. 1999;81:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(99)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herranz R. Cholecystokinin antagonists: pharmacological and therapeutic potential. Med Res Rev. 2003;23:559–605. doi: 10.1002/med.10042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin JG, Murthy KS, Grider JR, Makholuf GM. Stoichiometry of neurally induced VIP release, NO formation, and relaxation in rabbit gastric muscle. Am J Physiol. 1996;34:G357–G369. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.271.2.G357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulaksiz H, Arnold R, Goke B, Maronde E, Meyer M, Fahrenholz F, et al. Expression and cell-specific localization of the cholecystokinin B/gastrin receptor in the human stomach. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;299:289–298. doi: 10.1007/s004419900114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle RA. Cholecystokinin cells. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:221–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyasaka K, Funakoshi A. Cholecystokinin and cholecystokinin receptors. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s005350300000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton MF, Harper EA, Tavares IA, Shankley NP. Pharmacological evidence for putative CCK(1) receptor heterogeneity in human colon smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 2002b;136:873–882. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton MF, Welsh NJ, Tavares IA, Shankley NP. Pharmacological characterization of cholecystokinin receptors mediating contraction of human gallbladder and ascending colon. Regul Pept. 2002a;105:59–64. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(01)00383-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble F, Wank SA, Crawley JN, Bradwejn J, Seroogy KB, Hamon M, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XXI. Structure, distribution, and functions of cholecystokinin receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:745–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochi Y, Horie S, Maruyama T, Watanabe K, Yano S. Necessity of intracellular cyclic AMP in inducing gastric acid secretion via muscarinic M3 and cholecystokinin2 receptors on parietal cells in isolated mouse stomach. Life Sci. 2005;77:2040–2050. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Publicover NG, Hammond EM, Sanders KM. Amplification of nitric oxide signalling by interstitial cells isolated from canine colon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2087–2091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehfeld JF. Clinical endocrinology and metabolism. Cholecystokinin. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;18:569–586. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettenbacher M, Reubi JC. Localization and characterization of neuropeptide receptors in human colon. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2001;364:291–304. doi: 10.1007/s002100100454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjolund K, Ekman R, Lindgren S, Eehfeld JF. Disturbed motilin and cholecystokinin release in irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:1110–1114. doi: 10.3109/00365529609036895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternini C, Wong H, Pham T, De Giorgio R, Miller LJ, Kunts SM, et al. Expression of cholecystokinin A receptors in neurons innervating the rat stomach and intestine. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1136–1146. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70399-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi A, Takeshi T, Kaneko H, Hatori R, Ishige T, Suzuki M, et al. In vivo recording of colonic motility in conscious rats with deficiency of interstitial cells of Cajal, with special reference to the effects of nitric oxide on colonic motility. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1043–1048. doi: 10.1007/s00535-005-1688-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng BQ, Murthy KS, Kuemmerle JF, Grider JR, Sase K, Michel T, et al. Expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in human and rabbit gastrointestinal smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;38:G342–G351. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.2.G342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucchi MG, Corsani L, Bani D, Faussone-Pellegrini MS. Myenteric neurons and interstitial cells of Cajal of mouse colon express several nitric oxide synthase isoforms. Neurosci Lett. 2002;326:191–195. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga G, Balint A, Burghardt B, D'Amato M. Involvement of endogenous CCK and CCK-1 receptors in colonic motor function. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:1275–1284. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara P, Woskowska Z, Cipris S, Fox-Threlkeld JE, Daniel EE. Mechanisms of action of cholecystokinin in the canine gastrointestinal tract: role of vasoactive intestinal peptide and nitric oxide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;279:306–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldum HL, Kleveland PM, Sandvik AK, Brenna E, Syversen U, Bakke I, et al. The cellular localization of the cholecystokinin 2 (gastrin) receptor in the stomach. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;91:359–362. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2002.910613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]