Abstract

Now implement it

Three months after the interim report from Sir John Tooke’s independent inquiry into Modernising Medical Careers (MMC) in the United Kingdom1,2,3 comes the final report.4,5,6

The interim report was well received—87% of respondents to consultation either agreed or strongly agreed with the original 45 recommendations. Some of these have been slightly tweaked in the final report and two new ones have been added—the creation of a new oversight body for postgraduate medical education and training, and exploration of ways to legally offset or compensate for the effects of the European Working Time Directive.

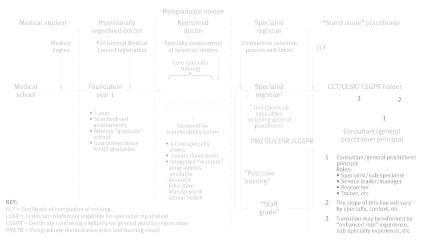

For practising doctors the final report’s recommendations for the structure of postgraduate training will matter most (see figure). Sir John recommends abandoning run through training for something that seems familiar, beginning with a one year post that resembles the pre-registration house officer of old, followed by three years of core specialist training as a registered doctor—a post that resembles the old senior house officer grade.

Postgraduate training: recommendations of the inquiry

The report argues for the uncoupling of current foundation years 1 and 2 (FY1 and 2), which would allow universities to guarantee a first medical job to their graduates (currently, European Union medical graduates requiring provisional registration can legitimately compete for FY1 positions). The current FY2 year would be bundled in with current specialist training years 1 and 2 to make up three years of core specialist training. The report rates the change as “entirely consistent” with the principles of training that has a broad based beginning and flexibility, which got mysteriously subverted7 somewhere between the chief medical officer’s 2002 consultation document Unfinished Business: proposals for reform of the senior house officer grade and the first MMC report a year later.

Entry to higher specialist training from core specialist training would entail assessments administered several times a year by national assessment centres, initially introduced on a trial basis for highly competitive specialties. Shortlisting for structured interviews for higher specialist training posts would take into account assessment scores, answers to specialty specific questions, and structured CVs.

Successful completion of higher specialist training would lead to a certificate of completion of training “confirming readiness for independent practice in that specialty at consultant level.” The interim report had two discrete positions after completion of training—“specialist” and “consultant”—separated by “optional higher specialist exams”. This was understandably interpreted as covert support for a subconsultant grade. Despite some fancy footwork, the final report doesn’t banish that suspicion entirely.

The length of training for general practice would be extended to five years—three years of core training plus two years as a general practitioner specialist registrar—bringing it in line with training in other developed European countries.

The interim report laid many of the problems besetting MMC—including unclear lines of responsibility and overemphasis on workforce imperatives—at the door of the Department of Health. Sir John now redresses the balance by proposing that the chief medical officer is made the senior responsible officer for medical education and the medical profession’s reference point regarding postgraduate medical education and training.

The chief medical officer would also liaise closely with a completely new body, NHS: Medical Education England (NHS:MEE), the functions of which would include defining the principles underpinning postgraduate medical education and training and holding the ring fenced budget for these in England. The new body is given a part to play in more than a third of the final report’s recommendations.

The mismatch between numbers of applicants and available training posts—one of the main causes of juniors’ pain in 2007—is beyond the report’s remit. Last year there were 32 649 applicants for 23 247 specialist training posts in the UK. Figure 4.17 of the interim report shows that the oversupply of applicants (9402) almost equals the number of applicants with highly skilled migrant programme visas (10 014). This scheme, however, is the business of the Home Office and the Treasury, and the Treasury is presumably happy to use an oversupply of applicants to keep down the pressure for salary increases. When the Department of Health tried unilaterally to impose additional conditions to the scheme, it was swatted down by the appeal court for its pains.8 The best that the report can do is to call for “a coherent model of medical workforce supply within which apparently conflicting policies on self-sufficiency and open-borders/overproduction should be publicly disclosed and reconciled.”

What are the chances that all 47 of the final report’s recommendations will be implemented? The executive summary concludes that strong agreement with the interim report provided “a compelling mandate for the implementation of the proposals.” But will the government agree? Governments have long found the best way to defuse a row is to appoint a suitably qualified member of the great and the good to conduct an inquiry. Nothing need actually change once the hoohah has blown over.

At the same time as Sir John was putting the finishing touches to his report, the House of Commons select committee on health was taking evidence on MMC—from many of the same people Sir John had interviewed. Worryingly, it heard that the secretary of state for health and chief medical officer had recently defended the concept of run through training and were going to retain it.9 It seems unlikely that the select committee’s final recommendations will be identical to Sir John’s. And Lord Darzi’s broader review of the National Health Service may also consider medical careers.

Before any other body’s recommendations about postgraduate medical education and training are implemented, they must be shown to be superior to those that have emerged from Sir John’s meticulous review of the topic, conducted with an urgency that befits its importance to doctors and patients alike.

Competing interests: TD’s wife is a consultant who qualified in the European Economic Area and was shortlisted and interviewed for specialty training posts at the London Deanery.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; not externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Tooke J. Aspiring to excellence: findings and recommendations of the independent inquiry into Modernising Medical Careers. Interim report. MMC Inquiry, 2007. www.mmcinquiry.org.uk

- 2.Eaton L. Tooke inquiry calls for major overhaul of specialist training. BMJ 2007;335:737 doi: 10.1136/bmj.39363.596273.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delamothe T. Modernising Medical Careers laid bare. BMJ 2007;335:733-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tooke J. Aspiring to excellence: final report of the independent inquiry into Modernising Medical Careers. London: MMC Inquiry, 2008. www.mmcinquiry.org.uk

- 5. Kmietowicz Z. Tooke report wants government to step back from medical education. BMJ 2008;336; doi: 10.1136/bmj.39455.498600.4E [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delamothe T. The BMJ interview: Sir John Tooke 2008. www.bmj.com/audio/index.dtl

- 7.Madden GBP, Madden AP. Has Modernising Medical Careers lost its way? BMJ 2007;335:426-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dyer C. Foreign doctors win high court challenge over training places. BMJ 2007;335:1009; doi: 10.1136/bmj.39398.720012.DB [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crockard A, Heard S, Hilborne J, Wilson I, Mehta R, Johnston M. House of Commons select committee on health. Uncorrected transcript of oral evidence. To be published as HC 25-iii. www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200708/cmselect/cmhealth/uc25-iii/uc2502.htm