Abstract

Guard cell chloroplasts are unable to perform significant photosynthetic CO2 fixation via Rubisco. Therefore, guard cells depend on carbon supply from adjacent cells even during the light period. Due to their reversible turgor changes, this import cannot be mediated by plasmodesmata. Nevertheless, guard cells of several plants were shown to use extracellular sugars or to accumulate sucrose as an osmoticum that drives water influx to increase stomatal aperture. This paper describes the first localization of a guard cell-specific Arabidopsis sugar transporter involved in carbon acquisition of these symplastically isolated cells. Expression of the AtSTP1 H+-monosacharide symporter gene in guard cells was demonstrated by in situ hybridization and by immunolocalization with an AtSTP1-specific antiserum. Additional RNase protection analyses revealed a strong increase of AtSTP1 expression in the dark and a transient, diurnally regulated increase during the photoperiod around midday. This transient increase in AtSTP1 expression correlates in time with the described guard cell-specific accumulation of sucrose. Our data suggest a function of AtSTP1 in monosaccharide import into guard cells during the night and a possible role in osmoregulation during the day.

The main purpose of guard cells is the minimization of water loss and the simultaneous optimization of CO2 uptake. This regulation of stomatal conductance is triggered by several environmental stimuli, such as light, humidity, temperature, or CO2 concentration. Changes in guard cell water potential and subsequent influx or efflux of water modulate shape and aperture of the guard cells (MacRobbie, 1998). This unique property depends on their symplastic isolation, which is mediated by a lack of functional plasmodesmata in mature guard cells (Palevitz and Hepler, 1985).

Analyses of the products obtained after 14CO2-labeling of guard cells identified 14C-labeled malate, the primary fixation product of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase, but hardly any Calvin cycle metabolites (Willmer and Dittrich, 1974; Raschke and Dittrich, 1977). This was shown to result from an extremely low activity of Rubisco and other Calvin cycle enzymes in guard cell chloroplasts (Willmer and Dittrich, 1974; Raschke and Dittrich, 1977; Outlaw et al., 1979, 1982; Reckmann et al., 1990).

Due to this lack of significant photosynthetic CO2 fixation and of functional plasmodesmata, guard cells depend on carbohydrate import from the apoplast. It was observed very early that guard cells are able to incorporate externally supplied Glc or Suc (Pallas, 1964; Dittrich and Raschke, 1977), and a correlation between transpiration and apoplastic as well as cytosolic Suc concentrations was shown for broad bean (Vicia faba) guard cells (Lu et al., 1995). Pulse labeling of intact broad bean leaves with 14CO2 (Lu et al., 1997) showed that 14C-labeled Suc identified in guard cells resulted from fixation products synthesized in and secreted from the palisade parenchyma. However, the identity of the transported molecules (Glc, Fru, or Suc) had not been determined. The first detailed analyses of guard cell-specific sugar transport (Ritte et al., 1999) identified and characterized a monosaccharide-H+ symporter activity in pea (Pisum sativum). Moreover, in the same paper, the existence of an additional Suc transporter was shown to be very likely.

Sugars imported into guard cells are necessary for the formation of starch. During stomatal opening, starch molecules are degraded to phosphoenolpyruvate and eventually into malate, a counter ion for accumulated K+ (Willmer and Dittrich, 1974; Raschke and Dittrich, 1977; Outlaw and Manchester, 1979; Schnabl et al., 1982; Tarczynski and Outlaw, 1990). More than a century ago (Kohl, 1886) it was postulated that sugars accumulating in guard cells might also be used as osmotica themselves and thus directly influence stomatal aperture. However, due to the extensive analyses of potassium ions as guard cell osmoticum (Assmann, 1993; Maathuis et al., 1997; MacRobbie, 1998; Dietrich et al., 2001), this suggested role of sugars has almost been forgotten. Nevertheless, several authors reported Suc accumulation in guard cells of different plant species (Reddy and Rama Das, 1986; Poffenroth et al., 1992; Talbott and Zeiger, 1993; Lu et al., 1997), and Talbott and Zeiger (1996, 1998) provided evidence that K+ and Suc are used as osmotica at different day times. Their data suggested that Suc replaces K+ as the primary guard cell osmoticum around midday (Talbott and Zeiger, 1996, 1998).

The AtSTP1 gene from Arabidopsis was the first cloned gene of a higher plant plasma membrane transporter (Sauer et al., 1990). In contrast to the extensive functional analyses of the AtSTP1 protein (Sauer et al., 1990; Boorer et al., 1994; Stolz et al., 1994), surprisingly little is known about the localization of the AtSTP1 protein in planta and about its physiological properties. Northern analyses suggested strong expression of AtSTP1 in leaves (Sauer et al., 1990), but in these experiments, cross reactions of the AtSTP1 probe with mRNAs from other AtSTP genes that were identified since then (Büttner and Sauer, 2000) could not be excluded. In addition, seedlings of an Atstp1 T-DNA insertion line have reduced sensitivity to toxic concentrations of d-Gal and d-Man (Shearson et al., 2000), but the precise site of AtSTP1 expression remained obscure.

This paper demonstrates that the AtSTP1 monosaccharide-H+ symporter gene (Sauer et al., 1990) is strongly expressed in guard cells and that this expression is strongly regulated. This is the first carbohydrate transporter gene shown to be expressed in guard cells. Circadian changes in AtSTP1 expression during the day and its modulation by light suggest two independent physiological functions of AtSTP1 in carbohydrate acquisition of guard cells. An Atstp1 T-DNA insertion line is analyzed.

RESULTS

Localization in Guard Cells of AtSTP1 mRNA by in Situ Hybridization and of AtSTP1 Protein by Immunohistochemistry

Northern analyses suggested a strong expression of AtSTP1 in leaves (Sauer et al., 1990), but at that time, cross reactions of the probe with mRNAs of other, only recently identified AtSTP gene family members (Büttner and Sauer, 2000) could not be excluded. In a recent paper by Shearson and coworkers (2003), this expression was confirmed by independently performed northern blots and by analyses of AtSTP1-promoter:luciferase plants. This paper clearly showed that AtSTP1 is strongly expressed in leaves of Arabidopsis seedlings and in leaf and stem tissue of mature Arabidopsis plants. The strong AtSTP1 expression in roots of Arabidopsis seedlings deduced from transport studies with an Atstp1 T-DNA insertion mutant (Shearson et al., 2000) has not been confirmed by these analyses.

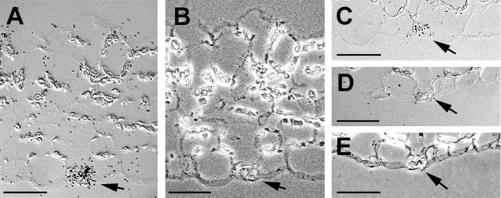

For a detailed analysis of this observed AtSTP1 expression in leaf and stem tissue (Sauer et al., 1990; Shearson et al., 2003) on the cellular level, in situ hybridizations were performed with radiolabeled AtSTP1 sense or antisense mRNA. In cross sections of rosette leaves (Fig. 1, A–D) or cotyledons (Fig. 1C) treated with a radiolabeled antisense probe, signals were observed only in guard cells. No signals were obtained in any other cell type or in sections treated with the sense probe (Fig. 1, D and E).

Figure 1.

Localization of AtSTP1 mRNA in guard cells of Arabidopsis leaves and seedlings by in situ hybridization. A, Cross section through a rosette leaf hybridized to AtSTP1 antisense RNA and photographed with differential interference contrast for optimal visualization of the hybridization signals. Accumulation of label is seen in the guard cell in the lower epidermis. B, Same section as in A photographed with phase contrast for better visualization of the guard cell and the epidermal cell walls. C, Cross section through a cotyledon hybridized to AtSTP1 antisense RNA and photographed with differential interference contrast. Accumulation of label is seen in the guard cell in the lower epidermis. D, Cross section through a rosette leaf hybridized to AtSTP1 sense RNA and photographed with differential interference contrast. No accumulation of label is seen in the guard cells. E, Same section as in D photographed with phase contrast. Guard cells are marked with an arrow. All space bars = 25 μm.

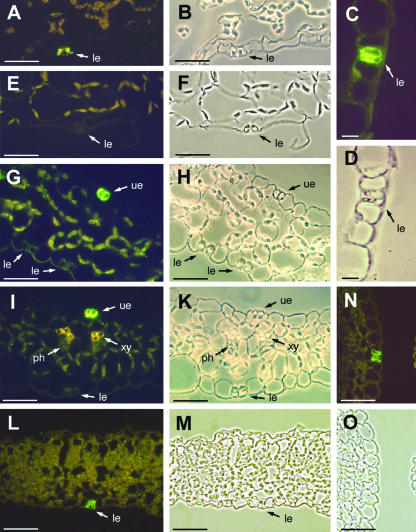

This result was confirmed by immunohistochemical analyses of AtSTP1 localization (Fig. 2) using anti-AtSTP1 antiserum from rabbits immunized with recombinant AtSTP1 protein (Stolz et al., 1994). Binding of anti-AtSTP1 antibodies was visualized by indirect immunofluorescence with anti-rabbit IgG decorated with FITC-isomer 1-conjugate. AtSTP1-specific and FITC-IgG-dependent fluorescence was confined to guard cells of various Arabidopsis tissues, such as rosette leaves (Fig. 2, A–D), sepals (Fig. 2, G–K), cotyledons (Fig. 2, L and M), ovaries (Fig. 2, N and O), or stems (data not shown). The fluorescence is clearly visible and specific for this single cell type. No fluorescence was detected in leaves, when the second antibody was omitted (data not shown) or when an antiserum was used that had been raised against the pollen-specific AtSTP2 protein and not against AtSTP1 (Fig. 2, E and F; Truernit et al., 1999).

Figure 2.

Immunolocalization of AtSTP1 protein in guard cells from different Arabidopsis tissues. A, Cross section through a rosette leaf stained with anti-AtSTP1 antiserum/fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). B, Same section as in A photographed under white light. C, Guard cell from an Arabidopsis rosette leaf stained with anti-AtSTP1 antiserum/FITC shown at higher magnification. D, Same section as in C photographed under white light. E, Cross section through a rosette leaf treated with an anti-AtSTP2 control serum antiserum/FITC. F, Same section as in E photographed under white light. G, Cross section through a sepal stained with anti-AtSTP1 antiserum/FITC. H, Same section as in G photographed under white light. I, Cross section through a sepal stained with anti-AtSTP1 antiserum/FITC. K, Same section as in I photographed under white light. L, Cross section through a 4-d-old cotyledon showing anti-AtSTP1 antiserum/FITC-specific labeling only in the guard cells. M, Same section as in L photographed under white light. N, Cross section through the ovary stained with anti-AtSTP1 antiserum/FITC. O, Same section as in N photographed under white light. Arrows show guard cells of the lower (le) or upper epidermis (ue), the xylem (xy) and the phloem (ph). Scale bars = 10 μm in C and D; all other scale bars = 25 μm.

Immunohistochemical analyses with sepals revealed a clear difference in the amount of AtSTP1 protein found in guard cells of the upper (inner) and the lower (outer) epidermis (Fig. 2, G–K). Reproducibly stronger AtSTP1-specific fluorescence was detected in guard cells of the upper epidermis (facing the petals) than in guard cells of the lower epidermis.

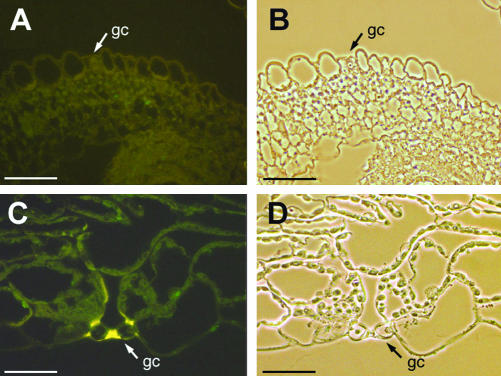

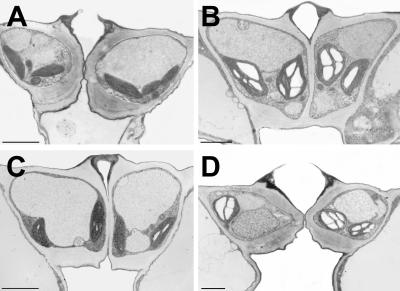

AtSTP1 Protein Is Absent from Guard Cells of Atstp1 Knockout Plants

We analyzed thin sections of the above-mentioned Atstp1 mutant (Shearson et al., 2000) for the presence or absence of AtSTP1 protein using the identical antibodies and the same technique as described above. Figure 3 shows that the AtSTP1 protein is absent from guard cells of the Atstp1 mutant plants. This result confirms the disruption of the AtSTP1 gene in the mutant line. It also confirms the data obtained by in situ hybridization in Figure 1 and the specificity of the antibody used for the immunohistochemical localization of ASTP1 in Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Lack of AtSTP1 protein in Atstp1 knockout plants. Sections were prepared from T-DNA-tagged Atstp1-knockout plants and treated with anti-AtSTP1 antiserum and FITC-conjugated second antiserum simultaneously with the sections presented in Figure 2. A, Cross section through the ovary of an Atstp1 mutant plant treated with an anti-AtSTP2 control serum antiserum/FITC. No green FITC-fluorescence is seen in the guard cells. The yellow color results from phenolics deposited in the guard cell wall. B, Same section as in A photographed under white light. C, Cross section through the cotyledon of an stp1 mutant plant stained with anti-AtSTP1 antiserum/FITC. No green FITC fluorescence is detected in the guard cells. D, Same section as in C photographed under white light. Arrows show guard cells (gc). All scale bars = 25 μm.

AtSTP1 Expression Is Induced/Derepressed in the Absence of Light and Is Transiently Increased at Midday

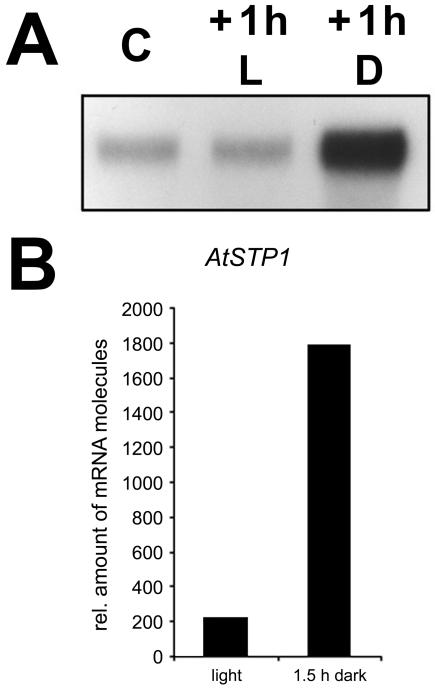

Guard cell chloroplasts contain only marginal amounts of Calvin cycle enzymes. This allows the light-dependent formation of ATP, but little or no photosynthetic CO2 fixation. Thus, AtSTP1 may import monosaccharides for guard cell metabolism, and an increased expression of AtSTP1 might be expected in the dark, when light-dependent ATP formation is zero. Therefore, we isolated total RNA from rosette leaves harvested at different times of the day and analyzed AtSTP1 mRNA levels. In Figure 4, one of three independently performed RNase protection analyses is presented. In all experiments, AtSTP1 mRNA levels increased significantly after dusk. During the night, AtSTP1 mRNA levels decreased slightly reaching a minimal level in the morning after the end of the dark phase.

Figure 4.

Diurnal changes of AtSTP1 expression in rosette leaves. RNase protection analyses (10 μg total RNA per lane) were performed with total RNA isolated at the indicated time points from Arabidopsis plants grown in a growth chamber under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark regime (three independent experiments). Gels were exposed to x-ray films (one typical autoradiogram is shown) and counts in AtSTP1 mRNA bands were quantified with a phosphor imager. The relative amounts of AtSTP1 mRNA determined in three experiments are presented (mean ± sd).

A less strong, but reproducible increase in AtSTP1 mRNA was also observed at midday (Fig. 4). This increased expression extended toward late afternoon and disappeared before dusk. The time course of this increase correlates well with the time of maximal Suc accumulation in guard cells described, e.g. for broad bean (Talbott and Zeiger, 1996). Recent high-density microarray analyses of more than 8,000 Arabidopsis genes for potential circadian clock regulation identified 453 cycling genes (Harmer et al., 2000). One of these genes was AtSTP1, which showed a 2.5-fold induction of mRNA levels peaking 8 h after subjective dawn. Both level and time of this circadian AtSTP1 induction correlate perfectly with the observed increase of AtSTP1 expression around midday (Fig. 4), suggesting that this peak results from circadian clock regulation.

In contrast, the observed increase of AtSTP1 mRNA levels at the onset of the dark period (Fig. 4) was not seen in these microarray analyses (Harmer et al., 2000), suggesting that this enhanced expression is not due to diurnal regulation. Further RNase protection analyses (Fig. 5A) support this conclusion and demonstrate that these changes are due to a rapid induction of AtSTP1 expression in the absence of light. Dark incubation of Arabidopsis plants for 1 h during the photoperiod caused a strong increase in AtSTP1 mRNA levels similar to that seen at the end of the photoperiod in Figure 4. AtSTP1 mRNA levels in control plants kept for 1 h in light showed no change.

Figure 5.

Dark induction of AtSTP1 gene expression. A, RNase protection analyses (8 μg per lane) were performed with total RNA isolated from rosette leaves of plants grown under the conditions described in Figure 4. C, Control leaves were harvested in the early afternoon. At this time several plants were put in the dark. Rosette leaves were harvested 1 h later from plants kept in the light (+1 h L) or put in the dark (+1 h D). B, Quantitative RT-PCR on mRNA from enriched guard cells. Plants were darkened for 1.5 h in the early afternoon while controls were kept illuminated. As in A, AtSTP1 expression was strongly induced (9-fold) upon darkening.

To confirm that the observed induction/derepression results from AtSTP1 gene expression in guard cells and not from other cells of the leaf, a quantitative reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR was performed with a LightCycler using mRNAs from guard cell-enriched preparations (Becker et al., 1993). This analysis (Fig. 5B) showed that mRNA preparations obtained from strongly enriched, intact guard cells of dark-treated plants (1.5 h) had about 9-fold increased AtSTP1 mRNA levels compared with guard cells from plants grown under constant light. This corresponds perfectly with the described induction/derepression at the end of the light phase in Figure 5 confirming that enhanced AtSTP1 expression is restricted to guard cells.

Lack of AtSTP1 Does Not Cause a Detectable Change in Guard Cell Phenotype

A lack of a monosaccharide transporter in the plasma of the guard cells might cause phenotypic changes due to the suboptimal or missing supply of organic carbon. This might result in the inability to perform volume changes or to respond to environmental stimuli. However, number, size, and morphology of guard cells in Atstp1 mutants were the same as in AtSTP1 wild-type (WT) plants. Moreover, mutant plants grew equally well under all conditions tested, and detached mutant leaves showed no altered water loss compared with detached leaves from WT plants (data not shown).

Reduced import of carbohydrates might also influence the starch content of the guard cells. Therefore, rosette leaves were harvested from Arabidopsis WT and mutant plants at the end of the dark phase and at the end of the light phase. Sections of fixed and embedded tissue were analyzed for starch granules in guard cells under the electron microscope. Figure 6 demonstrates that guard cell chloroplasts of both lines contained large amounts of starch at the end of the 8-h light period and little or no starch at the end of the 16-h dark phase. The variation in starch content of individual guard cells of WT or mutant plants at the end of the dark phase (no starch or tiny starch granules) was absolutely comparable. This suggests that carbon import into Arabidopsis guard is mediated not only by the exclusive transport activity of AtSTP1.

Figure 6.

Accumulation of starch in guard cells of Arabidopsis WT and AtSTP1 mutant plants. Rosette leaves were harvested from Arabidopsis Atstp1 mutant plants (A and B) or from WT plants (C and D) either at the end of the dark phase (A and C) or at the end of the 8-h-light phase (B and D). Leaf sections were fixed, embedded, and sectioned for electron microscopic analyses. Space bars = 2 μm.

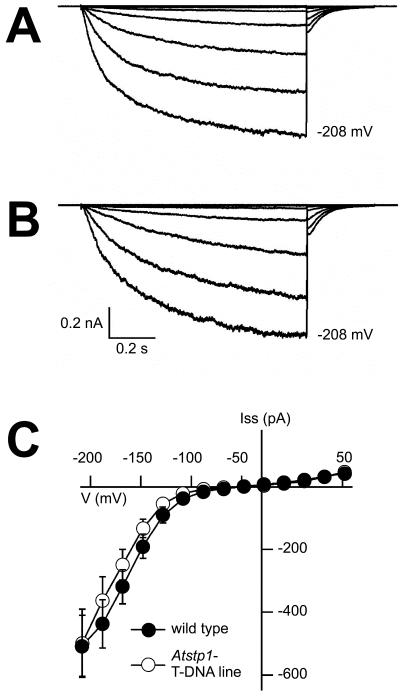

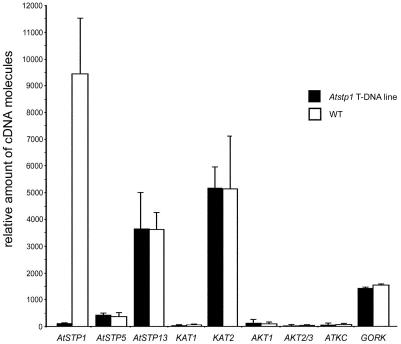

The lack of phenotypic differences between WT and Atstp1-mutant plants might result from a compensation of this genetic defect, e.g. by up-regulation of another member of the AtSTP gene family or of a K+ channel gene. Alternatively, the transport rates of already present sugar transporters or K+ channels could be increased. Therefore, K+ currents across the plasma membrane of guard cell protoplasts from WT and mutant plants (Fig. 7) and the potential induction of K+ channel genes or of AtSTP genes (Fig. 8) known to be expressed in guard cells were analyzed (AtSTP5 and AtSTP13; M. Büttner and N. Sauer, unpublished data).

Figure 7.

Electrophysiological analyses of macroscopic K+ currents in Arabidopsis guard cell protoplasts. Voltage- and time-dependent properties of inward K+ currents in guard cell protoplasts from an AtSTP1 WT plant (A) and from the Atstp1 T-DNA insertion mutant (B). Voltage pulses were applied to the protoplasts in the whole-cell configuration starting from a holding potential –48 mV in 20-mV decrements from +52 to –208 mV. Pipette solution contained 150 mm potassium gluconate, 2 mm MgCl2, 10 mm EGTA, 2 mm Mg-ATP, and 10 mm HEPES/Tris (pH 7.4). External solution contained 30 mm potassium gluconate, 1 mm CaCl2, and 10 mm MES/Tris (pH 5.6). C, Voltage dependence of inward K+ currents in guard cell protoplasts from WT (n = 13) and AtSTP1 knockout plants (n = 14). Current amplitudes were sampled at the end of 1-s pulses to voltages in the range from +52 to –208 mV. External solution contained 20 mm CaCl2, 30 mm potassium gluconate, and 10 mm MES/Tris (pH 5.6). Data points represent means ± se.

Figure 8.

Loss of AtSTP1 is not compensated by enhanced expression of AtSTP5, AtSTP13, or a K+ channel gene. Amounts of cDNA molecules in guard cell protoplasts were determined by quantitative RT-PCR on WT and the Atstp1 T-DNA insertion mutant (mean ± sd).

The observed inward K+ currents were identical in protoplasts isolated from leaves of WT and mutant plants (Fig. 7), which indicates that the lack of AtSTP1 is not compensated by an increased potassium influx into guard cells of the Atstp1 mutant. This was supported by quantitative PCR analyses with mRNAs obtained from guard cell protoplasts of AtSTP1 WT and Atstp1 mutant plants. Analyses of Arabidopsis guard cell K+ channels (Szyroki et al., 2001) revealed no differences in the mRNA levels of the analyzed channels (Fig. 8). In parallel, the relative mRNA levels of AtSTP5 and AtSTP13 were determined, which also turned out to be unchanged in WT and mutant lines (Fig. 8). These data suggest that none of the analyzed candidate genes is up-regulated in response to the knockout mutation in the AtSTP1 gene. However, it cannot be excluded that Glc transport by AtSTP5 and/or AtSTP13 is enhanced by an increased stability of these proteins or by altered translation rates for the corresponding mRNAs.

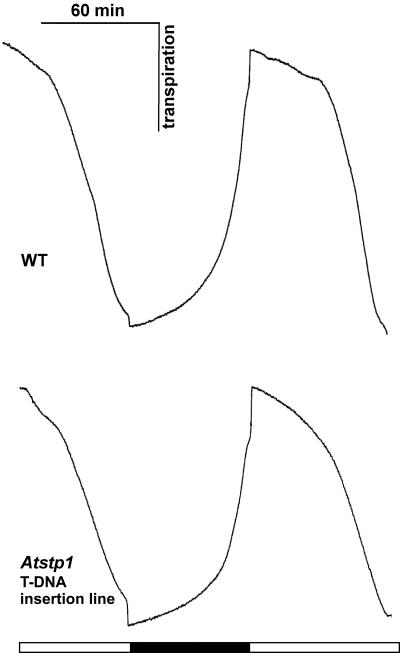

Eventually, stomatal movement and photosynthesis were followed by measuring water loss and CO2 assimilation with infrared gas analyzers (Hedrich et al., 2001) to examine the possibility that a loss of AtSTP1 affects guard cell performance. However, in AtSTP1 WT and in Atstp1 mutant plants, the observed transpiration was comparable (Fig. 9). Predarkened leaves opened and closed their stomata identically in response to light and darkness under ambient CO2 (300 μL L–1). Neither the amplitude nor the rate of stomatal movement was significantly altered in mutant plants. CO2-uptake rates were also comparable in mutant and WT plants (data not shown). Thus, the lack of AtSTP1 does not seem to result in a modification of stomatal properties.

Figure 9.

Gas exchange measurements with AtSTP1 WT and Atstp1 mutant plants. Transpiration of 8-week-old rosette leaves from Arabidopsis plants grown in a climate chamber under short-day conditions (8 h). Leaves from AtSTP1 WT (top panel) and Atstp knockout plants (bottom panel) were incubated in 300 μL L–1 CO2 and alternating light and dark conditions for stomatal opening and closure. Black box, Darkness; white box, light (700 μmol photons m–2 s–1; representative results of four independent experiments are given).

DISCUSSION

It is known that guard cells can import Glc from the apoplast and that this transport can be inhibited by other monosaccharides, such as Man or Fru (Ritte et al., 1999). Glc transport is energy dependent, enhanced in the presence of fusicoccin, an activator of plasma membrane H+-ATPases (Marrè, 1979), and inhibited by uncouplers. Our present paper provides evidence that in Arabidopsis, the H+-monosaccharide symporter AtSTP1 is responsible at least for part of this transport. Moreover, it shows that guard cell-specific AtSTP1 expression is strongly regulated by the diurnal clock and by light and that AtSTP1 expression varies between guard cells from both sides of a leaf. Analysis of an Atstp1 T-DNA insertion mutant showed that AtSTP1 protein and mRNA are in fact absent in guard cells of this line. However, phenotypic alterations could not be detected in mutant plants and guard cells.

Our analyses revealed an interesting regulation of AtSTP1 expression in guard cells with AtSTP1 transcript levels being significantly increased at the beginning of the dark phase (Fig. 4). This enhanced expression is due to dark induction or light repression of AtSTP1 and is also observed after a 1-h dark treatment of WT plants during the day (Fig. 5). The induction does not result from an increased AtSTP1 expression in other leaf cells, because it is also seen in strongly enriched preparations of intact guard cells (Fig. 5B; Becker et al., 1993). This suggests an increased import of carbohydrates into guard cells after the end of the photoperiod. This is surprising, because guard cell chloroplasts are packed with starch at this time (Fig. 6). Starch is known to be converted to malate, which acts as counter ion to K+ imported in the light during stomatal opening (Schnabl et al., 1982; Outlaw and Tarczynski, 1984) and might therefore be stored for the start of the next photoperiod. However, our results demonstrate that more or less all starch is metabolized during the dark phase in both AtSTP1 WT and mutant plants (Fig. 6). This suggests that the primary role of starch in guard cells is to drive the energy supply of the guard cells in the dark. Induction of AtSTP1 after sunset may support this carbon metabolism with carbohydrates imported from the apoplast. Alternatively, AtSTP1 may act as a retrieval transporter to avoid loss of Glc released from the apoplast during starch breakdown in the night.

The observation that Arabidopsis guard cells are practically free of starch in the morning makes it necessary to rethink the generally accepted model of starch breakdown for malate formation (Schnabl et al., 1982; Outlaw and Tarczynski, 1984). Our data suggest that malate might rather be formed from sugars imported by AtSTP1 or another guard cell monosaccharide transporter (AtSTP5 or AtSTP13). Alternatively, carbohydrates might be imported as Suc. Transport analyses performed by Ritte et al. (1999) on guard cells from broad bean with radiolabeled Suc provided evidence that these cells may possess Suc transport proteins. Recent analyses from our lab support this observation, because AtSUC2 mRNA (Sauer and Stolz, 1994) was shown to be present in guard cells by RT-PCR performed on guard cell-specific RNA preparations (P. Ache, R. Hedrich, and N. Sauer, unpublished data). Moreover, the AtSUC3 Suc transporter gene (Meyer et al., 2000) also seems to be expressed in Arabidopsis guard cells, because plants expressing the green fluorescent protein under the control of the AtSUC3-promoter show strong fluorescence in these cells (S. Meyer, C. Lauterbach, and N. Sauer, unpublished data). Finally, Arabidopsis may use Cl– as counter ion for K+ rather than malate. This has been shown for broad bean, where Cl– ions replace malate as counter ion depending on the growth conditions (Talbott and Zeiger, 1998).

The transient increase in AtSTP1 expression around the mid-point of the photoperiod is unlikely to reflect an increased demand of carbohydrates for ATP synthesis. Photophosphorylation is maximal at this time of the day. The increase in AtSTP1 expression may rather reflect an increased demand of carbon for the production of organic compounds, e.g. Suc. It is known that at this time of the day, guard cells start to replace K+, their major osmoticum during the morning hours (Raschke et al., 1988; Hedrich and Becker, 1994), by Suc (Lu et al., 1995; Talbott and Zeiger, 1996, 1998). Moreover, a clear correlation between Suc concentration and guard cell aperture in the afternoon has been shown (Talbott and Zeiger, 1996). Guard cell content of Glc or Fru did not change significantly over the course of the light period (Talbott and Zeiger, 1996), suggesting a rapid conversion of most of the imported monosaccharide into Suc.

AtSTP1 protein and AtSTP1 mRNA were localized in guard cells of different leaf types and of stems (Figs. 1 and 2). In sepals, higher levels of AtSTP1 protein were found reproducibly in the upper (facing the petals) than in the lower epidermis. Sometimes, but far less reproducibly and less obviously, we found also slight differences in the amount of AtSTP1 protein between the upper and lower epidermis of rosette leaves. In that case, however, the amount of AtSTP1 protein was higher in the guard cells of the lower epidermis. These differences in AtSTP1 expression between the upper and the lower epidermis layers may result from differences in the light intensity on both sides of the respective leaves. The upper epidermis of rosette leaves and the lower epidermis of the sepals in a budding flower are exposed to direct sunlight, and AtSTP1 expression may be repressed to some extent. Alternatively, the observed differences in the amount of AtSTP1 protein might be a measure for differences in the guard cell activities on both sides of these leaves.

We were not able to identify phenotypic differences between AtSTP1 WT and Atstp1 mutant plants with respect to their stomatal aperture, their water loss from detached leaves, or their growth and development. Atstp1 mutant plants were previously shown to be less sensitive to monosaccharides, such as Man or Gal, which inhibit germination and seedling development in WT Arabidopsis (Shearson et al., 2000). This reduced uptake capacity of mutant seedlings for radiolabeled monosaccharides can certainly not be explained by the lack of AtSTP1 protein in guard cells of cotyledons. Obviously, it cannot be excluded that besides the strong expression of the AtSTP1 gene in guard cells that can be visualized by the techniques used in this paper, there may be an additional, but weaker AtSTP1 expression in other cell types of Arabidopsis, e.g. in certain cells of the roots (Shearson et al., 2000). All attempts to identify AtSTP1 protein or AtSTP1 mRNA in roots by immunolocalization or in situ hybridization failed (data not shown). This observation is in perfect agreement with recent analyses of AtSTP1-promoter:luciferase plants (Shearson et al., 2003) showing strong AtSTP1 expression only in the leaves. In contrast to earlier reports (Shearson et al., 2000) AtSTP1 expression in roots of Arabidopsis seedlings was extremely weak (Shearson et al., 2003).

The lack of a detectable Atstp1 mutant phenotype in guard cells, in leaf development, or in plant growth (not shown) is not due to the enhanced expression of one of the other guard cell-specific AtSTP genes (Fig. 8; M. Büttner and N. Sauer, unpublished data). Moreover, we were not able to observe complementation of the midday induction of AtSTP1 (Fig. 4) by an increased inflow of K+ ions (Fig. 7) or by enhanced expression of a K+ channel gene (Fig. 8), which might replace the possibly lacking osmoticum Suc by K+.

Our data clearly support a physiological function of AtSTP1 in guard cells of all epidermis layers. However, the lack of detectible phenotypic differences between mutant and WT plants suggests that other transporters (or channels) can compensate this defect in Atstp1 plants. Therefore, the generation of multiple knockout plants will be necessary to get an answer to this question.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Growth Conditions

If not otherwise indicated, plants of Arabidopsis ecotype Wassilewskija and plants of the corresponding Atstp1 mutant line (Shearson et al., 2000) were grown in potting soil in the greenhouse or on agar medium in plastic containers under a 8-h-light/16-h-dark regime at 22°C and 60% relative humidity.

Immunohistochemical Techniques

The anti-AtSTP1 antiserum used in this paper has been described (Stolz et al., 1994). Crude antiserum was purified according to the procedure of Sauer and Stadler (1993).

Semithin sections (3–6 μm) were prepared from methacrylate embedded Arabidopsis tissue, treated with affinity-purified anti-AtSTP1 antiserum, and stained with anti-rabbit IgG-FITC-isomer 1-conjugate as published (Stadler and Sauer, 1996).

In Situ Hybridization with AtSTP1 Antisense Probes

For generation of radiolabeled AtSTP1 sense and antisense RNA probes, a 1,600-bp HindIII fragment of the AtSTP1 cDNA clone pHEX313H (Stolz et al., 1994) was cloned in both orientations into HindIII-digested pBluescript II SK– (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). 35S-labeled antisense and sense RNAs were synthesized with T7 RNA polymerase from the BamHI-linearized constructs.

For preparation of tissue sections, Arabidopsis tissue was fixed in 3.7% (v/v) formaldehyde, 50% (v/v) ethanol, and 10% (v/v) acetic acid at room temperature for 1 h and embedded in methacrylate as described (Stadler et al., 1996). Sections were hybridized and washed as published (Truernit et al., 1999).

RNA Isolation and RNase Protection Analyses

Arabidopsis tissue was collected, and RNA was isolated as described previously (Sauer et al., 1990). RNase protection analyses were performed as published (Ratcliffe et al., 1990; Gahrtz et al., 1996). For generation of the AtSTP1 antisense RNA probe, a 161-bp HincII/SacI fragment (bp 209–370) of the AtSTP1 cDNA clone pTF414A (Sauer et al., 1990) was cloned into pBluescript II SK– (Stratagene). 35S-labeled antisense RNA was synthesized with T3 RNA polymerase from the HincII-linearized construct yielding a 178-bp probe. The hybridizing portion of this probe was 164 bp long.

RNAs isolated from eight tissue samples withdrawn during a photoperiod were separated on 10% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels, and the counts per AtSTP1 band were determined with a phosphor imager. Counts of each time points were expressed as percentage of the whole day and used to determine the relative expression levels.

Quantitative RT-PCR

For RT-PCR experiments, guard cell protoplasts were isolated as described below. Poly(A+) RNA was purified, first-strand cDNA was prepared, and PCR was performed in a LightCycler (Roche Diagnostics, Basel) as described (Szyroki et al., 2001). The K+ channel-specific primers were identical to those used by Szyroki et al. (2001). For AtSTP1, we used the primers STP1LC2fwd (5′-GCA GCT TGC ATA GGG-3′) and STP1LC2rev (5′-TCT CAA GCG CAT TCC-3′); for AtSTP5, the primers STP15LCfwd (5′-AGC CGA ACT GTT TAT-3′) and STP15LCrev (5′-AAG AAG CGA ACC AAG-3′); and for AtSTP13, the primers STP13LC2fwd (5′-CCG TCG CTT TAC AGA-3′) and STP13LC2rev (5′-ACG CCA AGG ATA ATG-3′).

The GenBank accession numbers for K+ channels are as given by Szyroki et al. (2001), the Munich Information Center for Protein Sequences numbers for AtSTPs are as follows: AtSTP1, At1g11260; AtSTP5, At1g34580; and AtSTP13, At5g26340. All quantifications were normalized to 10.000 molecules of the actin 2/8 gene fragments of 435 bp amplified by ACT2/8fwd (5′-GGT GAT GGT GTG TCT-3′) and ACT2/8rev (5′-ACT GAG CAC AAT GTT AC-3′). Fragment lengths are: AtSTP1 = 400 bp, AtSTP5 = 208 bp, and AtSTP13 = 334 bp.

Isolation of Guard Cells and Protoplast Isolation

Enriched guard cell fractions were isolated from Arabidopsis leaves by the Blendor method described by Becker et al. (1993). Where indicated, guard cell protoplasts were isolated from this enriched fraction as described (Hedrich et al., 1990). The enzyme solution contained 0.8% (w/v) cellulase (Onozuka R-10), 0.1% (w/v) pectolyase, 0.5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin, 0.5% (w/v) polyvenylpyrrolidone, 1 mm CaCl2, and 8 mm MES/Tris, pH 5.6. The osmolarity of the enzyme solution was adjusted to 540 mosmol kg–1 using d-sorbitol.

Patch-Clamp Recordings

Measurements were performed as described (Szyroki et al., 2001). Pipette solutions (cytoplasmic side) contained: 150 mm potassium-gluconate, 2 mm MgCl2, 10 mm EGTA, 2 mm Mg-ATP, and 10 mm HEPES/Tris (pH 7.4). The standard external solutions contained: 30 mm potassium-gluconate, 1 mm CaCl2, and 10 mm MES/Tris (pH 5.6). Osmolarity of the solutions was adjusted to 540 mosmol kg–1 using d-sorbitol. Data were digitized (ITC-16, Instrutech, Elmont, NY), stored on hard disc, and analyzed using PULSE and PULSEFIT software (HEKA Elektronik, Lambrecht, Germany) and IGOR Pro software (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR).

Gas Exchange Measurements

Transpiration and CO2 exchange were determined as previously described (Hedrich et al., 2001; Szyroki et al., 2001) using an infrared gas analyzer in the differential mode (Binos, Leypold-Heraeus, Hanau, Germany).

Electron Microscopic Analyses

Arabidopsis plants were grown under short day conditions (8 h light/16 h dark), and rosette leaves were harvested from plants at different developmental stages either at the end of the dark phase or at the end of the light phase. For primary fixation, sections were incubated for 3 h at room temperature in 50 mm cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2, containing 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and 2.0% (v/v) formaldehyde. All further treatments and electron microscopic analyses were performed as described (Meyer et al., 2000).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.103.024240.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant nos. Sa382/5 and Sa382/8 to N.S. and grant no. Bu973/4 to M.B.).

References

- Assmann SM (1993) Signal transduction in guard cells. Annu Rev Cell Biol 9: 345–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker D, Zeilinger C, Lohse G, Depta H, Hedrich R (1993) Identification and biochemical characterization of the plasma-membrane proton ATPase in guard cells of Vicia faba L. Planta 190: 44–50 [Google Scholar]

- Boorer KJ, Loo DDF, Wright EM (1994) Steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetics of the H+/hexose cotransporter (STP1) from Arabidopsis thaliana expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Biol Chem 269: 20417–20424 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büttner M, Sauer N (2000) Monosaccharide transporters in plants: structure, function and physiology. Biochim Biophys Acta 1465: 263–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich P, Sanders D, Hedrich R (2001) The role of ion channels in light-dependent stomatal opening. J Exp Bot 52: 1959–1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittrich P, Raschke K (1977) Uptake and metabolism of carbohydrates by epidermal tissue. Planta 134: 83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahrtz M, Schmelzer E, Stolz J, Sauer N (1996) Expression of the PmSUC1 sucrose carrier gene from Plantago major L. is induced during seed development. Plant J 9: 93–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer SL, Hogenesch JB, Straume M, Chang H-S, Han B, Zhu T, Wang X, Kreps JA, Kay SA (2000) Orchestrated transcription of key pathways in Arabidopsis by the circadian clock. Science 290: 2110–2113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich R, Becker D (1994) Green circuits: the potential of plant specific ion channels. Plant Mol Biol 26: 1637–1650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich R, Busch H, Raschke K (1990) Ca2+ and nucleotide dependent regulation of voltage dependent anion channels in the plasma membrane of guard cells. EMBO J 9: 3889–3892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich R, Neimanis S, Savchenko G, Felle HH, Kaiser WM, Heber U (2001) Changes in apoplastic pH and membrane potential in leaves in relation to stomatal responses to CO2, malate, abscisic acid or interruption of water supply. Planta 213: 594–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl FG (1886) Die Transpiration der Pflanzen und ihre Einwirkung auf die Ausbildung pflanzlicher Gewebe. Harald Bruhn, Braunschweig, Germany

- Lu P, Outlaw WH Jr, Smith BG, Freed GA (1997) A new mechanism for the regulation of stomatal aperture size in intact leaves: accumulation of mesophyll-derived sucrose in the guard-cell wall of Vicia faba. Plant Physiol 114: 109–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P, Zhang SQ, Outlaw WH Jr, Riddle KA (1995) Sucrose: a solute that accumulates in the guard-cell apoplast and guard-cell symplast of open stomata. FEBS Lett 362: 180–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maathuis FJ, Ichida AM, Sanders D, Schroeder JI (1997) Of higher plant K+ channels. Plant Physiol 114: 1141–1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacRobbie EA (1998) Signal transduction and ion channels in guard cells. Philos Trans R Soc Lond 353: 1475–1488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrè E (1979) Fusicoccin: a tool in plant physiology. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 30: 273–288 [Google Scholar]

- Meyer S, Melzer M, Truernit E, Hümmer C, Besenbeck R, Stadler R, Sauer N (2000) AtSUC3, a gene encoding a new Arabidopsis sucrose transporter, is expressed in cells adjacent to the vascular tissue and in a carpel cell layer. Plant J 24: 869–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outlaw WH Jr, Manchester J (1979) Guard cell starch concentration quantitatively related to stomatal aperture. Plant Physiol 64: 79–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outlaw WH Jr, Manchester J, Dicamelli CA, Randall DD, Rapp BR, Veith GM (1979) Photosynthetic carbon reduction pathway is absent in chloroplasts of Vicia faba guard cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 76: 6371–6375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outlaw WH Jr, Tarczynski MC (1984) Guard cell starch biosynthesis is regulated by effectors of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. Plant Physiol 74: 424–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outlaw WH Jr, Tarczynski MC, Anderson LC (1982) Taxonomic survey for the presence of ribulose-1, 5-bisphosphate carboxylase activity in guard cells. Plant Physiol 70: 1218–1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palevitz BA, Hepler PK (1985) Changes in dye coupling of stomatal cells of Allium cepa and Commelina demonstrated by microinjection of Lucifer yellow. Planta 164: 473–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallas JE (1964) Guard cell starch retention and accumulation in the dark. Bot Gaz 125: 102–107 [Google Scholar]

- Poffenroth M, Green DB, Tallman G (1992) Sugar concentrations in guard cells of Vicia faba illuminated with red or blue light: analysis by high performance liquid chromatography. Plant Physiol 98: 1460–1471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raschke K, Dittrich P (1977) [14C]Carbon-dioxide fixation by isolated leaf epidermis with stomata closed or open. Planta 134: 69–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raschke K, Hedrich R, Reckmann U, Schroeder JI (1988) Exploring biophysical and biochemical components of the osmotic motor that drives stomatal movement. Bot Acta 4: 283–294 [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe PJ, Jones RW, Philips RE, Nicholls LG, Bell JI (1990) Oxygen-dependent modulation of erythropoietin mRNA levels in isolated rat kidney studied by RNase protection. J Exp Med 172: 657–660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reckmann U, Scheibe R, Raschke K (1990) Rubisco activity in guard cells compared with the solute requirement for stomatal opening. Plant Physiol 92: 246–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy AR, Rama Das VS (1986) Stomatal movement and sucrose uptake by guard cell protoplasts of Commelina benghalensis L. Plant Cell Physiol 27: 1565–1570 [Google Scholar]

- Ritte G, Rosenfeld J, Rohrig K, Raschke K (1999) Rates of sugar uptake by guard cell protoplasts of Pisum sativum L. related to the solute requirement for stomatal opening. Plant Physiol 121: 647–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer N, Friedländer K, Gräml-Wicke U (1990) Primary structure, genomic organization and heterologous expression of a glucose transporter from Arabidopsis thaliana. EMBO J 9: 3045–3050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer N, Stadler R (1993) A sink specific H+/monosaccharide cotransporter from Nicotiana tabacum: cloning and heterologous expression in baker's yeast. Plant J 4: 601–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer N, Stolz J (1994) SUC1 and SUC2: two sucrose transporters from Arabidopsis thaliana. Expression and characterization in baker's yeast and identification of the histidine tagged protein. Plant J 6: 67–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabl H, Elbert C, Krämer G (1982) The regulation of strach-malate balances during volume changes of guard cell protoplasts. J Exp Bot 33: 996–1003 [Google Scholar]

- Shearson SM, Alford HL, Forbes SM, Wallace G, Smith SM (2003) Roles of cell-wall invertases and monosaccharide transporters in the growth and development of Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot 54: 525–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearson SM, Hemmann G, Wallace G, Forbes S, Germain V, Stadler R, Bechtold N, Sauer N, Smith SM (2000) Monosaccharide/proton symporter AtSTP1 plays a major role in uptake and response of Arabidopsis seeds and seedlings to sugars. Plant J 24: 849–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler R, Brandner J, Schulz A, Gahrtz M, Sauer N (1996) Phloem loading by the PmSUC2 sucrose carrier from Plantago major occurs into companion cells. Plant Cell 7: 1545–1554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler R, Sauer N (1996) The Arabidopsis thaliana AtSUC2 gene is specifically expressed in companion cells. Bot Acta 109: 299–306 [Google Scholar]

- Stolz J, Stadler R, Opekarová M, Sauer N (1994) Functional reconstitution of the solubilized Arabidopsis thaliana STP1 monosaccharide-H+ symporter in lipid vesicles and purification of the histidine tagged protein from transgenic Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Plant J 6: 225–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szyroki A, Ivashikina N, Dietrich P, Roelfsma MRG, Ache P, Reintanz B, Deeken R, Godde M, Felle H, Steinmeyer R et al. (2001) KAT1 is not essential for stomatal opening. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 2917–2921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbott TD, Zeiger E (1993) Sugar and organic acid accumulation in guard cells of Vicia faba in response to red and blue light. Plant Physiol 102: 1163–1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbott TD, Zeiger E (1996) Central roles for potassium and sucrose in guard-cell osmoregulation. Plant Physiol 111: 1051–1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbott TD, Zeiger E (1998) The role of sucrose in guard cell osmoregulation. J Exp Bot 49: 329–337 [Google Scholar]

- Tarczynski MC, Outlaw WH Jr (1990) Partial characterization of guard-cell phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase: kinetic datum collection in real time from single-cell activities. Arch Biochem Biophys 280: 153–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truernit E, Stadler R, Baier K, Sauer N (1999) A male gametophyte-specific monosaccharide transporter in Arabidopsis. Plant J 17: 191–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmer CM, Dittrich P (1974) Carbon dioxide fixation by epidermal and mesophyll tissue of Tulipa and Commelina. Planta 117: 123–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]