Abstract

Background

The value of re-exploration for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma after the initial diagnosis of unresectability is unclear.

Methods

In this study, we analyzed 33 patients who were re-explored after an initial diagnosis of unresectability.

Results

At the time of reoperation, a resectable tumor was found in 18 patients: therefore, 15 pancreaticoduodenectomies, two total pancreatectomies and one left resection were performed with three vascular resections. Morbidity and mortality rates for the cohort were 6/33 and 1/33, without significant differences between resectable and nonresectable patients. Length of stay, duration of operation, and blood loss were significantly increased in the resection group. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis demonstrated increased median survival for resected patients (1078 days after the initial operation versus 547 days in the group of unresectable patients; p = 0.018). Analysis of the reasons against initial resection showed that, if the patients had been sent to a tertiary referral center for pancreatic surgery, a different decision in favor of resection would probably have been made in 14 out of 33 patients. A review of 10 published reports on reoperation for pancreatic cancer revealed results comparable to our study in terms of low morbidity and mortality as well as a survival benefit.

Conclusions

Reoperation for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma that is initially deemed unresectable can be safely performed in a selected group of patients by experienced surgeons, supporting the concept of patient centralization in pancreatic surgery. Resection at the second operation may confer a survival benefit even when the initial findings preclude a potentially curative approach.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, Reoperation, Second look, Unresectability

Surgical resection is the only curative approach available for patients suffering from pancreatic cancer.1 However, resection rates remain low, not only because advanced disease is present in the majority of patients, but also because nonspecialized centers often have insufficient experience with radical surgery.2–4 Resection rates in tertiary referral centers are increasing due to technical progress, improved perioperative management, increasing emphasis on a more-radical approach, such as resection of tumor-infiltrated portal vein, and improved experience in judging resectability.3,5–8 This holds particularly true for evaluating vascular infiltration, which may preclude resection. In these cases, extensive mobilization and careful dissection are necessary to distinguish accompanying inflammatory adhesions from tumor infiltration of retroperitoneal vessels. However, determination of resectability remains challenging, and thus in selected cases less-experienced surgeons are potentially more prone to mistakenly regard a tumor as unresectable.

Since randomized trials on the value of neoadjuvant therapy have not yet been published, it also remains unclear whether—particularly in younger patients—neoadjuvant treatment (or reoperation after initially palliative chemotherapy) may be beneficial, at least in some patients, and may thus lead to resectability of an initially unresectable tumor.

Reoperation of patients who were deemed unresectable may be a further option to increase resection rates.9–18 The value of re-exploration has only been analyzed by a few groups: 10 studies have addressed this question, with the first study concluding that an “appreciable salvage rate” is feasible on re-evaluation.9 Subsequent studies confirmed these results and demonstrated that a second-look operation can be performed with low morbidity and mortality rates, and that this approach confers a survival benefit for the then resectable patients.10–18 Calculations of statistically significant differences in survival of resected and unresected patients at reoperation are hampered by insufficient power of the individual studies due to small patient groups. However, there is a general trend showing that re-exploration may be an option in carefully selected patients at specialized centers.

In this study, we retrospectively analyzed our single-center experience with a group of patients who had initially been diagnosed as unresectable and who were subsequently referred to us for re-exploration. In addition, a literature review of the available (retrospective) studies was performed to more precisely define the value of re-exploration.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

From our database we identified 33 patients with ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas who had initially been diagnosed as unresectable (at other institutions) but were re-explored in the course of their disease. Patient characteristics, initial procedures, subsequent palliative or neoadjuvant therapies, operative details of the re-exploration, morbidity, and mortality (death within 30 days after surgery) were prospectively recorded. Patients were followed up until February 2007. At the time of analysis, two out of 14 patients in the group of unresectable patients and 11 out of 19 patients in the resection group were alive.

During the second-look operation, resectability was defined using previously reported criteria.1 If resection was impossible, a tumor biopsy was taken from those patients in whom the initially performed palliative operation was sufficient. In the case of an obstruction, a gastroenterostomy, hepaticojejunostomy or a double bypass procedure was performed. In resectable patients, a pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (ppPD) was the standard operation. However, if the tumor involved the pyloric region, a classical PD was carried out. To achieve tumor-free resection margins, a total pancreatectomy had to be performed in two cases. A distal pancreatectomy was performed for one tumor of the tail of the pancreas.

Pancreatic tumors other than ductal pancreatic adenocarcinoma were excluded. The specimens from resectable (at reoperation) patients were classified according to the tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) classification.19

For the preoperative imaging of operable patients, computed tomography of the abdomen or magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography (MRI/MRCP) was the standard.

Statistical Analysis

The Kaplan–Meier method was used for presentation of the survival curve, and differences in survival were evaluated with the log-rank test. A P value of < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Literature Review

A literature search was performed independently by CWM, JK, and JB as described previously.20 The last search was carried out on 30 January 2007. Available manuscripts were cross-searched to identify studies that had not initially been found. The search strategy revealed 10 retrospective studies on re-exploration after initial diagnosis of unresectability. No stratification was performed because only retrospective analyses have been published. Data collection was conducted as previously described.20

RESULTS

In this study, 33 patients (median age 60 years) from our prospectively maintained database who had been re-explored after having initially been defined as unresectable (operation between 2001 and 2005) were included. At the time of the initial operation, an exploratory laparotomy was performed in 51% of the patients, while in the other 49% a bypass operation or a biopsy was carried out (Table 1). The main reason for the definition of unresectability at the initial operation was vascular infiltration (six arterial infiltrations, nine venous infiltrations). In some patients, metastatic disease was present (Table 2). After the first operation, most patients received palliative/neoadjuvant therapy. The types of treatment varied considerably: 13 patients received chemoradiation, 12 patients were treated with chemotherapy, and eight patients received no therapy. There were no standardized treatment protocols for palliative/neoadjuvant therapy, but patients were treated according to local guidelines at the institution where the initial diagnosis had been made.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Unresectable patients (n = 15) | Resectable patients (n = 18) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 60 (41–68) | 61 (33–71) |

| Female | 3 | 4 |

| Male | 12 | 14 |

| Initial operation | ||

| Explorative laparotomy | 4 | 8 |

| Gastroenterostomy | 5 | 0 |

| Double bypass | 3 | 5 |

| Lymph node biopsy | 1 | 0 |

| Resection of abdominal wall tumor | 1 | 0 |

| Laparoscopy | 0 | 2 |

| Hepaticojejunostomy | 1 | 3 |

| Interval between surgeries (median) | 88 days | 101 days |

| Preoperative tumor markers | ||

| CA19-9 (median) | 608 U/l | 117 U/l |

| CEA (median) | 39143 U/l | 136 U/l |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 | 6 |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | 12 | 13 |

Table 2.

Criteria for initial inoperability

| Unresectable patients (n = 15) | Resectable patients (n = 18) | |

|---|---|---|

| Peritoneal metastasis | 4 | 0 |

| Vascular infiltration | 6 | 9 |

| Liver metastasis | 3 | 1 |

| Duodenal infiltration | 1 | 1 |

| Lymph node infiltration | 1 | 4 |

| Other/unknown | 0 | 3 |

Upon referral to our department, all patients presented in adequate general condition (ASA score ≤ 3; American Society of Anesthesiologists). At the second operation, 18 patients were found to have a resectable tumor, while in 15 patients the primary tumor could not be resected. The median time from initial surgery to re-exploration was 88 days in the unresectable group and 101 days in the group of patients in whom a resection could be performed. Except for one patient with a large tumor infiltrating the retroperitoneal vessels, metastatic disease (not detectable in the abdominal CT scan) was present in all the unresectable patients, precluding a surgical resection (Table 4).

Table 4.

Criteria for unresectability at reoperation

| Unresectable patients (n = 15) | |

|---|---|

| Peritoneal metastasis | 6 |

| Liver metastasis | 5 |

| Omental metastasis | 1 |

| Peritoneal and liver metastasis | 2 |

| Retroperitoneal infiltration | 1 |

In the group of patients who were found to be resectable, 15 pancreaticoduodenectomies, two total pancreatectomies and one distal pancreatectomy were performed (Table 3). Portal vein/superior mesenteric vein (SMV) resections had to be carried out in four patients. There was one patient with a liver metastasis at the initial operation (Table 2) who was resected at the second-look surgery. The patient had no liver metastases at the second look and was therefore considered resectable. This patient is alive at 1241 days after the initial surgery. Four out of five patients without neoadjuvant treatment who were resected (Table 1) received adjuvant chemotherapy. One patient refused adjuvant treatment.

Table 5.

Review of studies on re-exploration for pancreatic cancer

| Author | Year | Institution | Patients | Resection rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moosa | 1979 | University of Chicago | 24 | 17/24 (71%) |

| Jones | 1985 | University of Toronto | 50 | N/A |

| Hashimi | 1989 | Bradford Royal Infirmary | 26 | 11/26 (42%) |

| McGuire | 1991 | Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions | 55 | 33/55 (60%) |

| Tyler | 1994 | M.D. Anderson Cancer Center | 19 | 14/19 (74%) |

| Robinson | 1996 | M.D. Anderson Cancer Center | 29 | 29/29 (100%) |

| Johnstone | 1996 | Naval Medical Center, San Diego | 29 | 16/29 (55%) |

| Sohn | 1999 | Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions | 78 | 52/78 (67%) |

| Chao | 2000 | Fox Chase Cancer Center | 40 | 22/40 (55%) |

| Shukla | 2005 | Tata Memorial Hospital, India | 15 | 15/15 (100%) |

| This series | 2007 | University of Heidelberg | 33 | 18/33 (55%) |

Table 3.

Surgical procedures at second operation, morbidity and mortality

| Unresectable patients (n = 15) | Resectable patients (n = 18) | |

|---|---|---|

| Exploration with biopsy | 7 | – |

| Double bypass | 3 | – |

| Gastroenterostomy | 3 | – |

| Hepaticojejunostomy | 2 | – |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | – | 5 |

| Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy | – | 10 |

| Total pancreatectomy | – | 2 |

| Left resection | – | 1 |

| Duration of operation (min; median) | 105 | 440 |

| Blood loss (ml; median) | 100 | 500 |

| Morbidity | 2 | 3 |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 1 | 0 |

| Bilioma | 1 | 0 |

| Wound dehiscence | 0 | 1 |

| Cholangitis | 0 | 1 |

| Lymph fistula | 0 | 1 |

| Mortality | 0 | 1 |

| Length of stay (days; median) | 11 | 12 |

In the group of unresectable patients, bypass procedures were carried out in eight patients, while seven patients underwent exploration with tumor biopsy (Table 3). The postoperative course of the patients was mostly uneventful, with two morbidities in the inoperable group and five in the resected patients (Table 3). One patient who was resected died in the immediate postoperative period (mortality 1/18). The duration of the operation, amount of blood loss, and length of stay were increased in the resection group (Table 3).

Pathology reporting revealed that a T3 tumor was present in most of the cases. Only one patient was found with a T2 tumor. Nine pancreatic specimens (50%) were node positive, with an average of 21.5 harvested lymph nodes. A grade 1 tumor was found in only two patients, whereas a grade 2 tumor was present in nine patients and a grade 3 pancreatic cancer was present in seven patients.

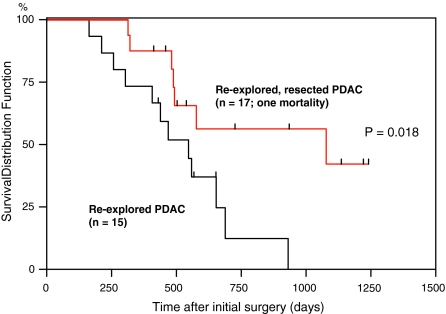

The Kaplan–Meier survival curves revealed a median survival of 439 days for unresectable patients versus 934 days for resected patients (after the second operation). A log-rank test demonstrated that this difference was statistically significant (P = 0.013; data not shown). To better judge the influence of neoadjuvant/palliative treatment on survival, a Kaplan–Meier curve was calculated for the survival after the initial operation. This analysis showed a significantly different median survival of 547 versus 1078 days for unresectable versus resectable patients (P = 0.018; Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve of re-explored patients after initial operation. Comparison of the survival curves of re-explored, resected patients (n = 17; one excluded due to postoperative mortality; red) and re-explored, unresectable patients (n = 15; black). A log-rank test demonstrated significantly increased survival in the resected patients (P = 0.018).

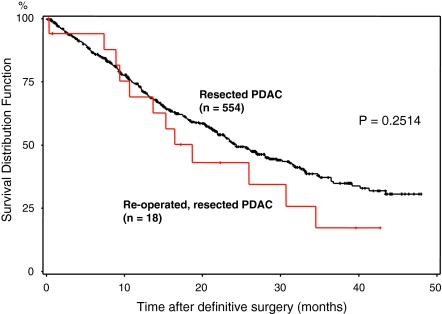

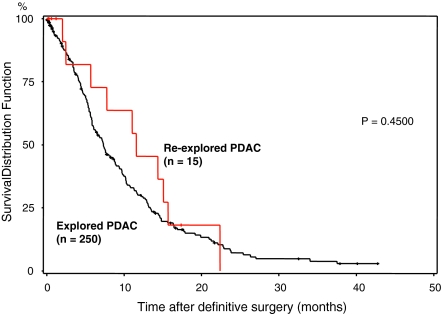

To judge whether resection at reoperation influences the outcome, we compared re-resected (18) and non-re-resected (15) patients with a cohort of 554 patients who were resected at the initial operation at our center and with a cohort of 250 patients who could not be resected. The Kaplan–Meier survival curve followed by a log-rank test revealed no differences in survival (P = 0.2514; Fig. 2) when comparing initially resected patients and patients resected at the second operation. Furthermore, there were also no differences in comparison of the unresectable patients, irrespective of the second surgery (P = 0.45; Fig. 3).

FIG 2.

Survival curves of re-explored, resected patients and 572 primarily resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) patients. Comparison of the survival curves of re-explored, resected patients (n = 18; red) and a control cohort of 572 patients (black) who were initially resected revealed no differences regarding survival (P = 0.2514).

FIG. 3.

Overall survival of re-explored, unresectable patients and 256 unresectable patients. The survival of a control cohort of 256 PDAC patients who were unresectable (n = 265) was compared with re-explored, unresectable patients (n = 15; red), revealing no differences in survival (P = 0.45).

Subsequently, we performed a retrospective review of the causes of initial unresectability. This revealed that only 11 of 33 patients had initially been treated at a high-volume center (defined as hospitals with a case load of >16 pancreatic resections per year7). Except for four cases with metastasized disease, infiltration of local structures was the main reason for initial unresectability. A detailed analysis of these causes of unresectability showed that 14 of 33 patients would probably have been resected if they had initially been referred to our center. In these cases, mainly venous (SMV/PV) infiltration was present, which may not be considered a contraindication for a resection.

Review of Retrospective Studies

Ten studies on the value of re-exploration to potentially achieve resection have been published so far.9–18 In the first study, by Moosa,9 17 patients were re-evaluated after having initially been diagnosed as unresectable. Of these, nine patients underwent total pancreatectomy, while in two patients no tumor was detectable. The survival of the resected cohort was 1.5–6 years, which was higher than the mean survival in the group of patients with inoperable disease (7–12 months). Similar results were reported by Hashimi et al., who performed a second-look operation on 30 patients, revealing that nine were resectable, while in two patients no tumor was found despite several biopsies.11 In the study by Jones and co-authors, preliminary surgery (nonresective) had been carried out before referral in 51% of the patients, leading to the correct diagnosis in only 44% of these.10 However, outcomes for this patient cohort are not specifically described. Two publications from the Johns Hopkins Institutions also extensively describe results obtained in re-exploratory surgery of two patient cohorts (recruited at different time periods: from 1979 to 1990 and from 1991 to 1997). In the first publication,12 the resection rate for pancreatic cancer at re-exploration was 58%, with subsequent mean survival periods of 20.5 months (pancreatic adenocarcinoma) and 33 months (nonpancreatic periampullary malignancies), which were comparable to the cohort of initially resectable patients. Sohn et al. subsequently described results obtained from re-exploration of a second cohort of patients that included all periampullary tumors.16 The resection rate at reoperation was 67%. There was a striking survival difference when comparing the unresectable and the resectable groups (at re-exploration), with a median survival of 7 versus 23 months, respectively. Comparison of the patients who were resected at re-exploration with a control group who had initially been resected revealed significantly increased survival rates in the reoperative group (Kaplan–Meier survival curve generated from the time of initial operation: 20 months in the control group versus 33 months in the reoperative group, P = 0.02). In the study by Tyler et al. from 1994, reoperation rates were comparable with the earlier published studies (14 out of 19 patients who underwent re-laparotomy were resected), as were the (low) complication rates (three out 14 resected patients).13 At the time of median follow-up of 26 months, four of ten patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma were alive, suggesting survival rates comparable to previously published results. Similarly, Johnstone and Sindelar showed a resection rate of 55% at re-exploration and significantly improved disease-specific survival rates in the resected group (P < 0.01) 14. Robinson and co-workers demonstrated an exceptionally high resection rate at reoperation of 100%.15 In a study by Chao and co-workers, a resection rate at the second look operation of 55% was shown.18 Furthermore, they could demonstrate that resection at the second operation led to “a median survival comparable with that of patients who did not undergo previous exploration”. In the most recently published study, by Shukla et al., all patients who were reoperated could be resected.17 Confirming the previously published studies, low morbidity and mortality rates were demonstrated.

DISCUSSION

This single-center experience shows that re-exploration of patients initially deemed unresectable may be an option for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. In concordance with previously published studies (which were all retrospectively conducted), re-exploration can yield resectability rates greater than 50% and can be performed with low morbidity and mortality. However, whether reoperation confers a survival benefit is still a matter of discussion.

Although diagnosis of resectability has been facilitated by the use of multidetector, high-resolution computed-tomography exploration often remains necessary.21,22 Particularly when neoadjuvant therapy has been applied, fibrosis and an inflammatory reaction frequently hamper exact assessment of tumor size and (potential) metastatic disease. A number of studies have demonstrated that both the complication rate and mortality after pancreatic surgery are significantly higher in hospitals that perform few operations.3,7,8 We found that, upon re-exploration, more than half of the tumors were resectable, and that 42% of the patients initially deemed unresectable could have been resected at high-volume centers. These results support the concept that patients with pancreatic cancer should be treated with an interdisciplinary approach at large tertiary referral centers.

Furthermore, resection in a second-look operation was shown to potentially confer a survival benefit, although it remains unclear whether this is due to resection or to favorable tumor biology in the patients in whom a regression of the initially metastasized or infiltrating tumor was achieved. Altogether, there was significantly increased survival in the reoperated group of patients compared with a control cohort of patients who were not reoperated (resected and unresectable). These results suggest that there might be a generally favorable tumor biology in this group of reoperated patients. However, the differences in survival conferred by resection at reoperation confirm the notion that in a subgroup of patients in good condition, re-laparotomy (and potentially resection) should be attempted. Furthermore, reoperated but not resected patients do not fare worse than those who were not resected initially and who were not explored again after chemotherapy or chemoradiation. Therefore, we again conclude that in a selected cohort of patients with a tendency towards remission, re-laparotomy may be a valid option. This holds particularly true when patients have initially been considered unresectable at smaller hospitals with less experience in pancreatic surgery and especially with less experience in judging whether a tumor is resectable. This is supported by many studies on reoperative pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer.12,13,15–17 As stated by Robinson and co-authors, “detailed preoperative imaging and a clearly defined operative plan would have allowed successful resection at the initial operation” in the majority of patients. However, accompanying inflammatory changes allow judgment of resectability only during the surgical procedure itself in many cases. Therefore, not only preoperative assessment but also the extension of resectability criteria (as present in high-volume centers) is a key factor for improving the outcome in patients with pancreatic cancer. We strongly suggest that all patients suffering from pancreatic cancer should be referred to high-volume centers. Furthermore, patients in generally good condition but locally unresectable disease should receive neoadjuvant chemoradiation, preferably within randomized controlled clinical trials.23 However, we do not consider infiltration of the SMV/portal vein (in contrast to superior mesenteric artery (SMA)/celiac trunk involvement) a contraindication for resection. Following the last cycle of chemoradiation, high-resolution CT will allow judging resectability in many cases and in the absence of metastatic disease, surgical exploration remains the only option to determine resectability.

In conclusion, reoperation for pancreatic cancer after initial classification of unresectability revealed resectability in half of patients. Since the majority had received chemotherapy/chemoradiation after the initial operation, the concept of selecting patients by neoadjuvant therapy may be supported. Furthermore, a subgroup analysis revealed that a large number of patients who were initially deemed unresectable at smaller hospitals would have been resectable at a large tertiary referral center, which again promotes the concept of patient centralization in pancreatic surgery. A survival benefit for the resected patients underlines the efficacy of a surgical resection even in a situation in which the initial findings preclude a potentially curative approach.

Acknowledgements

This study was in part supported by a postdoctoral research program grant from the University of Heidelberg awarded to CWM.

References

- 1.Wagner M, Redaelli C, Lietz M, Seiler CA, Friess H, Buchler MW. Curative resection is the single most important factor determining outcome in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg 2004;91:586–94 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Cress RD, Yin D, Clarke L, Bold R, Holly EA. Survival among patients with adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: a population-based study (United States). Cancer Causes Control 2006;17:403–9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.van Heek NT, Kuhlmann KF, Scholten RJ, et al. Hospital volume and mortality after pancreatic resection: a systematic review and an evaluation of intervention in the Netherlands. Ann Surg 2005;242:781–8, discussion 788–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Weitz J, Koch M, Friess H, Buchler MW. Impact of volume and specialization for cancer surgery. Dig Surg 2004;21:253–61 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer of the head of the pancreas. 201 patients. Ann Surg 1995;221:721–31; discussion 731–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Cameron JL, Riall TS, Coleman J, Belcher KA. One thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. Ann Surg 2006;244:10–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1128–37 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, Goodney PP, Wennberg DE, Lucas FL. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 2003;349:2117–27 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Moossa AR. Reoperation for pancreatic cancer. Arch Surg 1979;114:502–4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Jones BA, Langer B, Taylor BR, Girotti M. Periampullary tumors: which ones should be resected? Am J Surg 1985;149:46–52 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Hashimi H, Sabanathan S. Second look operation in managing carcinoma of the pancreas and periampullary region. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1989;168:224–6 [PubMed]

- 12.McGuire GE, Pitt HA, Lillemoe KD, Niederhuber JE, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL. Reoperative surgery for periampullary adenocarcinoma. Arch Surg 1991; 126:1205–1210; discussion 1210–02 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Tyler DS, Evans DB. Reoperative pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 1994;219:211–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Johnstone PA, Sindelar WF. Radical reoperation for advanced pancreatic carcinoma. J Surg Oncol 1996; 61:7–11; discussion 11–3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Robinson EK, Lee JE, Lowy AM, Fenoglio CJ, Pisters PW, Evans DB. Reoperative pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary carcinoma. Am J Surg 1996;172:432–7; discussion 437–8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Sohn TA, Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Pitt HA, Huang JJ, Hruban RH, Yeo CJ. Reexploration for periampullary carcinoma: resectability, perioperative results, pathology, and long-term outcome. Ann Surg 1999;229:393–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Shukla PJ, Qureshi SS, Shrikhande SV, Jagannath P, Desouza LJ. Reoperative pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary carcinoma. ANZ J Surg 2005;75:520–3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Chao C, Hoffman JP, Ross EA, Torosian MH, Eisenberg BL. Pancreatic carcinoma deemed unresectable at exploration may be resected for cure: an institutional experience. Am Surg 2000;66:378–85; discussion 386 [PubMed]

- 19.TNM classification of malignant tumors, 6th edition, ed. L.H. Sobin, C. Wittekind. 2002. New York: Wiley

- 20.Michalski CW, Kleeff J, Wente MN, Diener MK, Buchler MW, Friess H. Systematic review and meta-analysis of standard and extended lymphadenectomy in pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg 2007;94:265–73 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Imamura M, Doi R, Imaizumi T, et al. A randomized multicenter trial comparing resection and radiochemotherapy for resectable locally invasive pancreatic cancer. Surgery 2004;136:1003–11 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Spanknebel K, Conlon KC. Advances in the surgical management of pancreatic cancer. Cancer J 2001;7:312–23 [PubMed]

- 23.Kleeff J, Friess H, Buchler MW. Neoadjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg 2007;94:261–2 [DOI] [PubMed]