Abstract

In most fungal ascomycetes, mating is controlled by a single locus (MAT). Fungi requiring a partner to mate are heterothallic (self-sterile); those not requiring a partner are homothallic (self-fertile). Structural analyses of MAT sequences from homothallic and heterothallic Cochliobolus species support the hypothesis that heterothallism is ancestral. Homothallic species carry both MAT genes in a single nucleus, usually closely linked or fused, in contrast to heterothallic species, which have alternate MAT genes in different nuclei. The structural organization of MAT from all heterothallic species examined is highly conserved; in contrast, the organization of MAT in each homothallic species is unique. The mechanism of conversion from heterothallism to homothallism is a recombination event between islands of identity in otherwise dissimilar MAT sequences. Expression of a fused MAT gene from a homothallic species confers self-fertility on a MAT-null strain of a heterothallic species, suggesting that MAT alone is sufficient to change reproductive life style.

Which mode of fungal sexual reproduction, heterothallism or homothallism, is derived and what genetic mechanism(s) mediates the change from one to the other? Some authors (1–7) have hypothesized that homothallism arises from heterothallism and others (8–10) have suggested the reverse. To address this issue, we have compared MAT sequences from heterothallic and homothallic species within the ascomycete genus Cochliobolus, using a combination of molecular genetic and phylogenetic methods. Because MAT genes control the reproductive process (7), comparison of their sequences should reflect life history and may reveal mechanisms underlying changes in reproductive mode. Indeed, we have discovered fused MAT genes in homothallic species that provide a snapshot of the genetic link between heterothallism and homothallism.

Alternate sequences at MAT are not alleles in the classic sense because they lack significant sequence similarity and encode different transcriptional regulators (11–14). The term idiomorph is used to describe this unusual genetic organization (3), which is common among all MAT loci from heterothallic ascomycetes investigated to date (7). Because they are dissimilar sequences, idiomorphs do not normally recombine and are inherited uniparentally, as is the mammalian Y chromosome (15–17). In this report, we offer evidence that homothallism is derived from heterothallism and that the vehicle for this change is, in fact, a recombination event between short islands of identity within the idiomorphs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, Media, Crosses, and Transformation.

Cochliobolus heterostrophus heterothallic strains C4 (MAT-2), C5 (MAT-1), CB7 (MAT-1; alb1), and CB12 (MAT-2; alb1) have been described (18). Homothallic strains Cochliobolus luttrellii 14643–1 and Cochliobolus cymbopogonis 88109–1 were provided by J. Alcorn (Department of Primary Industries, Queensland, Australia), Cochliobolus kusanoi Ck2 by T. Tsuda (Kyoto University, Japan), and Cochliobolus homomorphus 13409 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. C. heterostrophus MAT-deletion strain ΔNcoMAT-2 (isolation C4–41.7; MAT-0;hygBR; refs. 19 and 20) was the recipient for heterologous gene expression. Growth conditions, storage of fungal strains (21), and mating (18) and transformation (22) procedures have been described.

DNA Preparation and PCR Primers.

Isolation of fungal DNA (19, 23) and PCR amplification conditions (24) were described previously. Primers used to isolate the homothallic MAT genes included TP2, TP3 (24), AD2 (25), and ho1–ho24 (Fig. 1). Primer sequences are available on request. Primers GPD1 and GPD2, designed by using C. heterostrophus GPD1 (GenBank accession no. X63516) and Cochliobolus lunatus GPD (GenBank accession no. X52718) sequences, generated a fragment of ≈600 bp (440 bp of coding sequence plus two introns). Ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions were amplified with primers ITS4 and ITS5, by using conditions described (26).

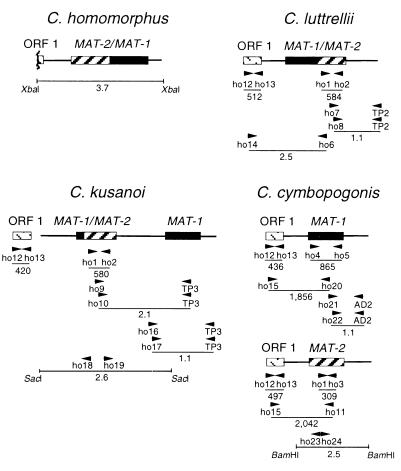

Figure 1.

Strategies to clone MAT genes from homothallic Cochliobolus species, as described in the text. Textures of boxes indicate MAT-1 (black), MAT-2 (hatches), ORF1 (dotted diagonal lines); lines extending from boxes represent sequences flanking idiomorphs. Arrowheads identify locations and 5′ → 3′ direction of PCR primers. Numbers with decimals are in kb, those without are in bp.

Cloning MAT Loci from Homothallic Species.

MAT gene sequences appear to evolve rapidly (27, 28), making them difficult to clone from new species by heterologous hybridization (e.g., only two of the four homothallic Cochliobolus MAT genes hybridized to C. heterostrophus MAT DNA). Thus, a PCR approach was adopted (Fig. 1) and, for each new gene, if necessary, primers were redesigned based on consensus of already acquired MAT sequences.

C. homomorphus. A portion of the C. homomorphus MAT gene, the High Mobility Group (HMG) box (14), cloned originally by using PCR amplification (24), was used to probe a C. homomorphus subgenomic library constructed with an ≈3.7-kb XbaI-digested fraction that hybridized to both C. heterostrophus MAT probes. Sequencing of a positive clone insert revealed an ORF with >70% nucleotide identity to the C. heterostrophus MAT-1 and MAT-2 ORFs.

C. luttrellii. Primers ho1 and ho2, corresponding to conserved MAT-2 regions of heterothallic C. heterostrophus and homothallic C. homomorphus, were used with C. luttrellii DNA as template to amplify a 584-bp fragment with 92% nucleotide identity to C. heterostrophus MAT-2. Sequencing of a 1.1-kb C. luttrellii TAIL-PCR (25) product obtained with primer TP2, MAT-2-specific primer ho7, and nested MAT-2 primer ho8 revealed the 3′ end of MAT-2 and flanking region, which showed 84% identity with the C. heterostrophus 3′ flanks. To clone the 5′ flank, degenerate primers ho12/ho13 corresponding to ORF1 (a gene of unknown function found ≈1 kb 5′ of MAT in heterothallic Cochliobolus spp., homothallic C. homomorphus, and distantly related Alternaria alternata (Fig. 2) (20) were used with C. luttrellii DNA to amplify a 512-bp fragment, confirmed by sequencing to be the C. luttrellii homolog of C. heterostrophus ORF1 (98.4% nucleotide identity). Primer ho14 specific to C. luttrellii ORF1 was then used with MAT-2-specific primer ho6 to amplify a 2.5-kb fragment that, when sequenced, revealed part of ORF1 and MAT-1 fused to MAT-2.

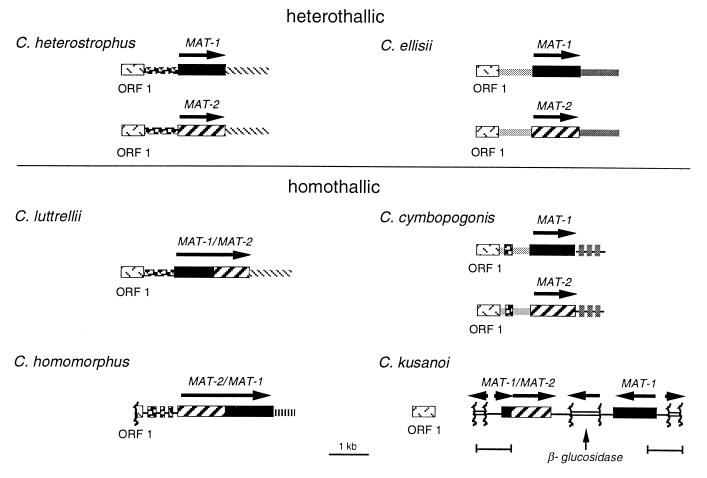

Figure 2.

Organization of MAT in heterothallic and homothallic species. The arrangement is identical in all heterothallic species examined to date, including C. heterostrophus and C. ellisii (shown here), C. carbonum, C. victoriae, C. intermedius, and asexual B. sacchari and A. alternata (not shown, see Fig. 5). Organization of each homothallic locus is unique, as described in the text. Textures of boxes are as in Fig. 1 for MAT-1, MAT-2, and ORF1; gene encoding β-glucosidase (open boxes); all other textures represent noncoding sequences 5′ or 3′ of MAT that are either unique to a particular species or common to more than one. Arrows indicate direction of transcription. Tightly linked to MAT in all species (except C. kusanoi) is a highly conserved ORF (ORF1) that shows similarity to a Saccharomyces cerevisiae ORF (GenBank accession no. U22383) of unknown function. Note that all genes are linked or fused, except that linkage has not yet been detected between the C. cymbopogonis MAT genes (which reside in the same nucleus unlike the heterothallic ones which reside in separate nuclei) or between ORF1 and C. kusanoi MAT.

C. kusanoi. Primers ho1/ho2 amplified a 580-bp fragment of MAT-2 from C. kusanoi. TAIL-PCR primers ho9/TP3 followed by ho10/TP3 amplified a 2.1-kb region 3′ of the MAT-2 fragment. Sequencing revealed that both MAT genes are arranged as shown in Fig. 2. Sequencing of a 1.1-kb TAIL-PCR product amplified with primers ho16/TP3 and ho17/TP3 revealed the 5′ end of MAT-1 and 438 bp of 5′ flank. The 5′ region of the MAT-2 PCR fragment, which could not be amplified by TAIL-PCR, was obtained by using inverse PCR (29, 30). Genomic DNA was digested with SacI (an ≈2.6-kb SacI fragment hybridizes to MAT-2), self-ligated, and used as template with primers ho18/ho19. Sequencing the product revealed the 5′ end of MAT-2 and 2.0 kb of 5′ flank including part of MAT-1 fused to MAT-2. ORF1 primers ho12/ho13 amplified a 420-bp fragment.

C. cymbopogonis. ORF1-primers ho12/ho13 yielded a fragment; however, MAT-2 primers ho1/ho2, which had been successful with C. luttrellii and C. kusanoi, did not work with C. cymbopogonis. Therefore a new MAT-2 primer, ho3, corresponding to conserved MAT-2 sequences of C. heterostrophus, C. luttrellii, C. homomorphus, and C. kusanoi, was used with ho1 to amplify a 309-bp fragment of C. cymbopogonis MAT-2. For MAT-1, primers ho4/ho5, based on MAT-1 sequences of C. heterostrophus, C. luttrellii, C. homomorphus, and C. kusanoi, were successful (fragment = 865 bp). Combinations of C. cymbopogonis ORF1-specific (ho15) and MAT-2 (ho11)- or MAT-1 (ho20)-specific primers revealed two copies of ORF1 (93% nucleotide identity), each linked to one MAT homolog. Sequencing of a 1.1-kb TAIL-PCR product amplified by using primer combinations ho21/AD2 and ho22/AD2 revealed the 3′ end of MAT-1 and 0.8 kb of 3′ flank. Sequencing of a 2.5-kb PCR product amplified by inverse PCR on BamHI-digested genomic DNA using primer pair ho23/ho24 revealed the 3′ end of MAT-2 and 1.1 kb of 3′ flank.

Sequences of C. heterostrophus MAT-1 (GenBank accession no. AF029913) and MAT-2 (GenBank accession no. AF027687), C. carbonum MAT-1 (GenBank accession no. AF032368), C. victoriae MAT-2 (GenBank accession no. AF032369), and C. ellisii MAT-1 (GenBank accession no. AF129746) and MAT-2 (GenBank accession no. AF129747), as well as sequences of all homothallic species reported here [C. luttrelli, C. homomorphus, C. kusanoi, and C. cymbopogonis (GenBank accession nos. AF129740, AF129741, AF129742, and AF129744 and AF129745, respectively)], have been deposited. Sequencing details are available on request.

Expression of C. luttrellii MAT in C. heterostrophus.

A 3.9-kb fragment carrying the entire C. luttrellii MAT-1/2 ORF plus 1.6 kb of 5′ and 0.5 kb of 3′ flanking DNA was amplified from C. luttrellii genomic DNA by using primers LMAT/p1 (5′-CCTCTAGAGGAACTTGGAATCGAACTCGCTTGTGTCTC-3′) and LMAT/p2 (5′-CCTCTAGAGGGACTACAACTGCCAGGAGAAGCCAAGAA3-′), and Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene). Both primers included an XbaI site (italicized). The PCR product was purified (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA), digested with XbaI, and ligated into the XbaI site of pBG, which carries the bar gene for resistance to bialaphos (31), creating pLMATB. C. heterostrophus MAT deletion strain ΔNcoMAT-2 was transformed with pLMATB. Transformants were selected on bialaphos, screened for resistance to hygromycin, and purified by single conidium isolation.

Phylogenetic Analyses.

ITS and GPD sequences were spliced by using CAP2 (32), aligned first with clustal w (33) and then adjusted manually with seqapp (34). The alignment and list of all isolates analyzed are available on request (berbee@unixg.ubc.ca). Gaps were excluded, but all other positions were kept for the analysis. Each data set was initially analyzed by itself. We found 10,940 equally parsimonious trees for the 36 ITS sequences and 42 trees for the 36 GPD sequences in 50 replicated heuristic searches by using the TBR option and random addition of taxa with paup Version 4.0 d61a (35). The Kishino and Hasegawa test (36) indicated that the data sets were not substantially incongruent because the log likelihood of the fit of either the ITS or GPD data to the ITS + GPD trees was not significantly different. We found consensus trees for the ITS, the GPD, and the combined data sets by using 1,000 replicated parsimony searches without branch swapping. All branches receiving 55% or more bootstrap support in either data set were present in trees from both data sets, again indicating congruence between the ITS and GPD data sets. Also, 20 of the 22 nodes in the bootstrap trees received higher support from combined data than from either individual data set. Because the two data sets were substantially congruent, we combined them for further phylogenetic analysis. A maximum-likelihood tree was generated by using paup Version 4.0 d61a and default options. Using this tree, we estimated that 40% of the sites in the alignment were invariable and that, for the variable sites, substitution rates followed a γ-distribution with a shape parameter of 1. Using these estimates for substitution parameters, we found three equally likely trees, with log likelihoods of −8,235. The three trees differed only in the arrangement of near-zero-length branches. To test support for branches, paup was used to perform 500 bootstrap replicated parsimony searches with tree bisection and reconnection. All branches receiving 50% or more bootstrap support were also present in the maximum likelihood tree.

RESULTS

Organization of Homothallic MAT Loci.

The structural organization of the MAT loci of five heterothallic species (C. heterostrophus, C. carbonum, C. victoriae, C. ellisii, and C. intermedius) is highly conserved, with each strain carrying a single MAT gene; two examples are shown in Fig. 2. Furthermore, MAT loci from two asexual species, Bipolaris sacchari (MAT-2 only, GenBank accession no. X95814), a close relative, and A. alternata (both MAT idiomorphs; ref. 37), a distant relative of C. heterostrophus, also have the same organization (data not shown). Together, these species represent most of the major branches of the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5). In contrast, all homothallic species carry both MAT genes in one genome, but the structural organization of each locus is unique (Fig. 2). In two cases (C. luttrellii and C. homomorphus) the genes are fused into a single ORF; the gene order in C. luttrellii (5′ MAT-1/MAT-2 3′) is reversed in C. homomorphus (5′ MAT-2/MAT-1 3′). In the remaining two cases, the genes are not fused. In C. kusanoi, the organization is 5′ MAT-2 3′–3′ MAT-1 5′, and part of the sequence between the genes is similar to a portion of the β-glucosidase gene normally found 3′ of both MAT genes in heterothallic C. heterostrophus (GenBank accession nos. AF029913 and AF027687) (20). To the 5′ of MAT-2 is a perfect inverted repeat of a 561-bp region containing 123 bp of the 5′ end of the MAT-1 ORF fused to the 5′ end of MAT-2 and 145 bp of a different fragment of the β-glucosidase gene, separated from each other by 293 bp. C. cymbopogonis carries both homologs of the heterothallic idiomorphs, but these are not closely linked; PCR reactions using various combinations of MAT-1/MAT-2-specific primers yielded no products, and gel blot analysis provided no evidence for linkage within 30 kb. Thus, the MAT genes have close physical association in three Cochliobolus homothallics but not in the fourth. ORF1, a gene with no apparent mating function (20) in heterothallic C. heterostrophus, is present in all homothallic species; in three of four cases it is ≈1 kb 5′ of the 5′ end of MAT. C. cymbopogonis has two copies of ORF1, each linked to a MAT gene. ORF1 is not closely linked to MAT in C. kusanoi.

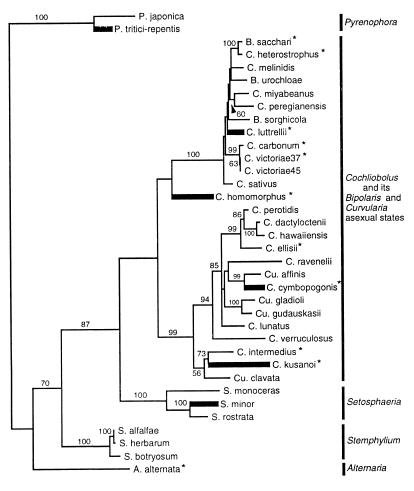

Figure 5.

Maximum likelihood tree generated from combined ITS and GPD sequence data by using paup Version 4.0 d61a (35). Homothallic species (thick lines) are scattered among heterothallic species, indicating their polyphyletic origin. Numbers are percentages (only those over 50 are shown) of times a group was found in 500 parsimony bootstrap replicates. ∗ indicate species from which MAT loci were examined.

Recombination Converts a Heterothallic to a Homothallic Species.

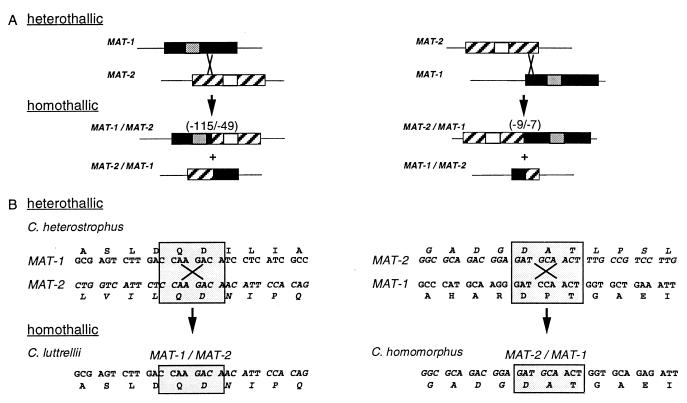

Insight into the genetic mechanism by which one reproductive life style evolves from the other was obtained by comparing MAT sequences from a closely related pair of species, heterothallic C. heterostrophus and homothallic C. luttrellii (Fig. 3). Inspection of the sequence at the MAT fusion junction in C. luttrellii revealed that 345 nt from the 3′ end of the MAT-1 ORF and 147 nt from the 5′ end of the MAT-2 ORF are missing, compared with the C. heterostrophus heterothallic homologs. The deletions are consistent with the hypothesis that a crossover event occurred within the dissimilar C. heterostrophus genes at positions corresponding to the fusion junction (Fig. 3). Inspection of the C. heterostrophus genes reveals 8 bp of sequence identity precisely at the proposed crossover site, which would explain this arrangement. A single crossover within this region would yield two chimeric products, one of which is identical to the fused MAT gene actually found in C. luttrellii (Fig. 3). A similar scenario can be proposed for C. homomorphus; in this case the fused gene is missing 27 nt from the 3′ end of MAT-2 and 21 nt from the 5′ end of MAT-1 compared with the C. heterostrophus MAT genes. Examination of the C. heterostrophus MAT sequences at positions corresponding to the C. homomorphus fusion junction reveals nine bp of identity (with one mismatch) and thus a putative recombination point (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Models for evolution, by recombination events, of fused homothallic MAT genes in C. luttrellii and C. homomorphus from opposite heterothallic MAT genes in C. heterostrophus (the heterothallic progenitor of C. homomorphus is unknown). (A) Misalignment of homologous flanking sequences could bring into register short islands of identity between the largely dissimilar MAT idiomorphs. A homologous recombination event at the point of identity would result in two fused MAT genes, both incomplete with respect to their heterothallic counterparts. If the crossover point were on either side of the DNA binding region (14), one fusion product would have both DNA-binding motifs and one would have neither. The number of amino acids eliminated (C. luttrellii, 115 from the 3′ end of MAT-1, 49 from the 5′ end of MAT-2; C. homomorphus, 9 from the 3′ end of MAT-2, 7 from the 5′ end of MAT-1) depends on the position of the crossover point (compare A Left with A Right). Textures are described in Fig. 1; small boxes within idiomorphs represent DNA-binding motifs; gray, α-box in MAT-1, white, HMG box in MAT-2 (14). (B) Inspection of the actual nucleotide sequences of the C. heterostrophus MAT-1 and MAT-2 genes reveals an 8-bp region of complete identity (shaded box, B Left) and a 9-bp region, with one mismatch (shaded box, B Right), corresponding to the C. luttrellii and C. homomorphus fusion points, respectively. Recombination in the Upper Left box creates precisely the sequence found in the C. luttrellii MAT-1/MAT-2 fused gene (Lower Left box); the left side of the fused sequence is similar to C. heterostrophus MAT-1 and the right side to MAT-2. Recombination in the Upper Right box creates the C. homomorphus MAT-2/MAT-1 fused gene (Lower Right box). Single letters above or below codons are standard amino acid abbreviations.

Conversion of a Heterothallic to a Homothallic Species.

To determine whether MAT genes alone can control reproductive style, the sterile C. heterostrophus MAT-deletion strain ΔNcoMAT-2 was transformed with pLMATB carrying the fused C. luttrellii MAT-1/2 gene. Transformants (barR;hygR) were purified, selfed, and crossed (18) to albino C. heterostrophus MAT-1 and MAT-2 tester strains.

Three transformants were analyzed in detail; all carried the transforming plasmid at ectopic sites. Abundant pseudothecia formed when the transformants were selfed or crossed (Fig. 4 Top and Middle), most of which showed some degree of fertility (1–10% of wild-type ascospore production). Pseudothecia and progeny from selfs were always pigmented, whereas approximately half the pseudothecia and half the progeny from crosses were albino and half of each were pigmented, indicating that heterothallic C. heterostrophus expressing a homothallic MAT gene can both self- and outcross (Fig. 4 Bottom). Thus, the C. luttrellii MAT-1/2 gene alone conferred selfing ability to heterothallic C. heterostrophus without impairing its ability to cross.

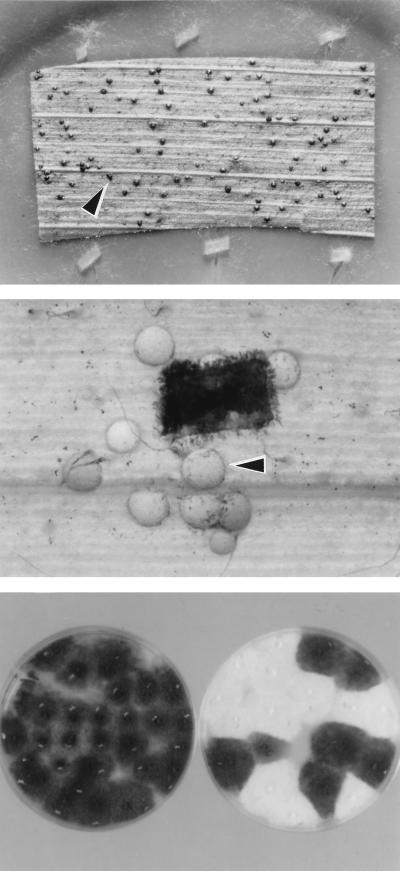

Figure 4.

The C. luttrellii homothallic MAT gene alone confers on heterothallic C. heterostrophus the ability to self and cross. (Top) Plate with a senescent corn leaf as substrate for mating (18) inoculated with C. heterostrophus carrying the fused C. luttrellii MAT gene. Black bodies (arrowhead) are pseudothecia, indicating selfing. (Middle) Part of a mating plate, inoculated first with an albino C. heterostrophus MAT-1 tester strain, followed by inoculum (black rectangle) of a pigmented C. heterostrophus MAT-deletion strain carrying the fused C. luttrellii MAT gene. White pseudothecia (arrowhead) indicate crossing with the albino parent as female, because pseudothecial walls are of maternal origin. (Bottom Left) Progeny of a selfed transformant (Top), demonstrating that pseudothecia from selfed strains yield viable ascospores and that all progeny of a selfed pigmented strain are pigmented. (Bottom Right) Progeny of a cross (Middle), demonstrating that ascospores are viable and that alleles at the color marker Alb1 segregate (1:1).

Phylogenetic Analyses.

To determine whether phylogenetic analyses support a convergent origin for homothallism, we used maximum likelihood and parsimony trees inferred from the ITS and GPD data set. All of the resulting trees (Fig. 5) show that homothallism is polyphyletic. None of the six homothallic species clustered together in any of the 15 most parsimonious trees or in maximum likelihood trees. How strong is the support for keeping the four homothallic species of Cochliobolus separated? To answer this question, we used the Kishino and Hasegawa test as implemented by paup Version 4.0 61a to compare the fit of the data to the maximum likelihood tree (Fig. 5) with the fit to the most likely of the parsimony trees constrained to show the homothallics as a monophyletic group. The log likelihood of the most likely parsimony tree constrained to show a monophyletic origin of homothallism was −8,530, compared with −8,235 for the most likely unconstrained tree. The constrained tree was more than 10 SD worse than the unconstrained tree, a difference significant at P < 0.0001. Thus, phylogenetic evidence clearly supports independent evolution of homothallism in the four homothallic Cochliobolus species.

DISCUSSION

In earlier reports, it was speculated that heterothallic fungal species are ancestral to homothallic species (1–7) and that homothallics may arise by unequal crossover events (2). Our analysis of extant MAT sequences provides direct evidence supporting these hypotheses. Comparison of MAT DNA from a closely related pair of species, one heterothallic, the other homothallic (Figs. 3 and 5), revealed a genetic mechanism that likely explains how a heterothallic species can become homothallic. Both MAT-1 and MAT-2 are truncated in the homothallic C. luttrellii MAT fusion, suggesting an unequal crossover event in the heterothallic MAT progenitor, resulting in the fusion; perusal of MAT ORFs revealed an 8-bp sequence that is identical between the C. heterostrophus genes, precisely where MAT-1 becomes MAT-2 in C. luttrellii (Fig. 3). Although the idiomorphs are largely dissimilar, as little as 8 bp may be enough to promote rare homologous recombination, because as little as 4 bp is sufficient for recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (38). After recombination, one fusion product would be the functional C. luttrellii gene (Fig. 2); the other is predicted to have no mating function because it would lack both DNA-binding domains (14). The recombination point alone suggests heterothallic-to-homothallic evolution. It is difficult to envision a mechanism for the reverse, e.g., that homothallic C. luttrellii MAT, lacking 164 aa, could acquire sequences necessary for two full-length MAT genes, distribute them in separate nuclei, and become heterothallic. Furthermore, all heterothallic Cochliobolus species have the same MAT organization, whereas each homothallic species is unique at MAT. It is unlikely that these different homothallic loci could give rise to the single arrangement found in the diverse collection of heterothallic species that we studied (Fig. 5).

A similar recombination mechanism can be proposed for evolution of homothallic C. homomorphus, despite the fact that a close heterothallic relative is not available (Fig. 5). There is a 9-bp island of identity in the C. heterostrophus MAT sequences, again precisely at the fusion junction (Fig. 3). A crossover at this point, in the hypothetical heterothallic progenitor, would eliminate 16 aa and create the C. homomorphus MAT-2/MAT-1 chimera. Similarly, recombination between as-yet-unidentified regions of identity in the 5′ and 3′ flanks of heterothallic idiomorphs likely gave rise to the MAT gene arrangement in C. kusanoi, although there is no direct evidence for this in the available heterothallic sequences. The scrambled sequences in C. kusanoi suggest multiple recombination events. The mechanism by which C. cymbopogonis arose is difficult to assess until we determine whether the MAT genes are linked.

The hypothesis that homothallism derives from heterothallism is supported by data from heterologous expression studies. The ability of C. heterostrophus carrying C. luttrellii MAT to form fertile reproductive structures when selfed indicates that it has all of the genes needed to be homothallic except the “correct” configuration of the MAT gene itself. The same haploid C. heterostrophus MAT-deletion strain, expressing both C. heterostrophus MAT genes, can produce pseudothecia, but these are barren (20). The single variable in these experiments is MAT, indicating it alone can control differences in reproductive life style. We suggest that a recombination event is necessary to initiate the change from one reproductive mode to the other. Continued alterations in a new homothallic strain could optimize its homothallic fitness.

The organization and origin of homothallic MAT loci have been investigated in certain homothallic members of an unrelated family of fungi, the Sordariaceae. Most, like Cochliobolus, carry both MAT idiomorphs found in heterothallic species (2, 39, 40). An exception is the genus Neurospora, where certain species carry only one (2). All heterothallic and homothallic Neurospora spp. have a MAT-flanking region that distinguishes heterothallic from homothallic species (39). We have not detected such a region flanking Cochliobolus MAT (Fig. 2). Neurospora terricola, one of two homothallic species that carries both MAT genes, has them on the same chromosome, although not closely linked (6). The MAT locus of homothallic Sordaria macrospora contains counterparts of all four MAT genes encoded by the two MAT idiomorphs of heterothallic Neurospora crassa (7); one gene is a mat A/mat a idiomorph fusion that is like N. crassa mat A-3 at the 5′ end and like noncoding mat a idiomorph sequence at the 3′ end (40). Homothallic MAT genes from Neurospora africana (41) and Sordaria macrospora (40) act as mating activators in heterothallic genetic backgrounds, as does the C. luttrellii gene. Because the Sordariaceae genes were not expressed in MAT-deleted heterothallic strains, the ability to promote ascospore formation could not be evaluated, because of the “interference” phenomenon described earlier (7, 19).

The evolutionary origins of the dissimilar MAT idiomorphs of ascomycetes are unknown. It has been suggested (7) that the small pockets of identity in the otherwise unlike heterothallic MAT idiomorphs reflect common ancestry. Conceivably, these pockets are remnants of a series of mutagenic events in a single ancestral gene. The mutations, coupled with recombination suppression, might have led to the highly divergent extant MAT genes that now encode different products (14). A similar scenario has been proposed for evolution of the Y chromosome (15–17).

The importance of combining molecular genetic and phylogenetic approaches to understanding life style evolution cannot be overemphasized. Phylogenetic analysis allowed us, on the one hand, to choose diverse species for demonstrating that MAT is constant in heterothallics, and on the other hand, to pick a pair of closely related species for evaluating lifestyle evolution. The C. luttrellii MAT fusion led to detection of the 8-bp recombination point, the key to understanding events in the change from heterothallism to homothallism. Hypotheses regarding reproductive lifestyle evolution in any fungal group would be strengthened by examination of nucleotide sequences of genes controlling the sexual process. As MAT data are accumulated, we may find that some fungi evolve differently from Cochliobolus. Geiser et al. (10), for example, suggest (based on phylogenetic analyses using β-tubulin and hydrophobin sequences) that heterothallism is the derived state in Aspergillus species. A mechanism underlying evolution in this direction has not been established. Perhaps, in homothallic species that have two complete unfused MAT genes, either could be deleted independently, leaving a strain with a single MAT gene. If the opposite MAT gene were deleted from a different homothallic strain, the population would contain non-selfing pairs that might be capable of crossing with each other.

Although our molecular and phylogenetic data argue that, in nature, homothallism is derived from heterothallism, it is possible that this process can be reversed under laboratory conditions, thus providing a tool that would facilitate genetic analysis of homothallic species. For example, it may be possible to make a homothallic species heterothallic by replacing its MAT gene(s) with individual heterothallic MAT genes, each in a different strain, then crossing the strains. This may not work with the homothallic Neurospora species, which do not conidiate or form female receptive hyphae (41–43). All homothallic Cochliobolus species, however, are able to conidiate, although their ability to form trichogynes or outcross has not been evaluated for lack of genetically marked strains required as testers.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Science Foundation grant to B.G.T. and a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council grant to M.B.; S.H.Y. was supported by a Korean Government Overseas Scholarship.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ITS

internal transcribed spacers

- TAIL

thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR

Footnotes

References

- 1.Perkins D. Genetics. 1987;115:215–216. doi: 10.1093/genetics/115.1.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glass N L, Metzenberg R L, Raju N B. Exp Mycol. 1990;14:274–289. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metzenberg R L, Glass N L. BioEssays. 1990;12:53–59. doi: 10.1002/bies.950120202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nauta M J, Hoekstra R F. Heredity. 1992;68:537–546. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1992.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nauta M J, Hoekstra R F. Heredity. 1992;68:405–410. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1992.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beatty N P, Smith M L, Glass N L. Mycol Res. 1994;98:1309–1316. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coppin E, Debuchy R, Arnaise S, Picard M. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:411–428. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.4.411-428.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wheeler H E. Phytopathology. 1954;44:342–345. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olive L S. Am Nat. 1958;865:233–250. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geiser D M, Frisvad J C, Taylor J W. Mycologia. 1998;90:831–845. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glass N L, Grotelueschen J, Metzenberg R L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4912–4916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.4912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Staben C, Yanofsky C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4917–4921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.4917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Picard M, Debuchy R, Coppin E. Genetics. 1991;128:539–547. doi: 10.1093/genetics/128.3.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turgeon B G, Bohlmann H, Ciuffetti L M, Christiansen S K, Yang G, Schafer W, Yoder O C. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;238:270–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00279556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charlesworth B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:5618–5622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.11.5618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rice W R. Science. 1994;263:230–232. doi: 10.1126/science.8284674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall Graves J A. Philos Trans R Soc London B. 1995;350:305–312. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1995.0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leach J, Lang B R, Yoder O C. J Gen Microbiol. 1982;128:1719–1729. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wirsel S, Turgeon B G, Yoder O C. Curr Genet. 1996;29:241–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wirsel S, Horwitz B, Yamaguchi K, Yoder O C, Turgeon B G. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;259:272–281. doi: 10.1007/s004380050813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoder O C. In: Cochliobolus heterostrophus, Cause of Southern Corn Leaf Blight. Sidhu G S, editor. Vol. 6. San Diego: Academic; 1988. pp. 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turgeon B G, Garber R C, Yoder O C. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:3297–3305. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.9.3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee S B, Taylor J W. In: Isolation of DNA from Fungal Mycelia and Single Spores. Innis M A, Gelfand D H, Sninsky J J, editors. San Diego: Academic; 1990. pp. 282–287. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arie T, Christiansen S K, Yoder O C, Turgeon B G. Fungal Genet Biol. 1997;21:118–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y G, Whittier F. Genomics. 1995;25:674–681. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80010-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White T J, Bruns T, Lee S B. In: Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics. Innis M A, Gelfand D H, Sninsky J J, editors. San Diego: Academic; 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferris P J, Pavlovic C, Fabry S, Goodenough U W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8634–8639. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turgeon B G. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1998;36:115–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.36.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ochman H, Gerber A S, Hartl D L. Genetics. 1988;120:621–624. doi: 10.1093/genetics/120.3.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Triglia T, Peterson M G, Kemp D J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:8186. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.16.8186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Straubinger B, Straubinger E, Wirsel S, Turgeon G, Yoder O. Fungal Genet Newslett. 1992;39:82–83. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang S. Genomics. 1992;14:18–25. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(05)80277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins D G, Sharp P M. Comput Appl Biosci. 1989;5:151–153. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/5.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilbert D G. seqapp. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swofford D L, Siddall M E. Cladistics. 1997;13:153–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.1997.tb00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kishino H, Hasegawa M. J Mol Evol. 1989;29:170–179. doi: 10.1007/BF02100115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshida T, Arie T, Noguchi M, Nomura Y, Yoder O C, Turgeon B G, Yamaguchi I. Ann Phytopathol Soc Jpn. 1998;64:373. (abstr.). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schiestl R H, Petes T D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7585–7589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Randall T A, Metzenberg R L. Genetics. 1995;141:119–136. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poeggeler S, Risch S, Kueck U, Osiewacz H D. Genetics. 1997;147:567–580. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.2.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glass N L, Smith M L. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;244:401–409. doi: 10.1007/BF00286692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Howe H B, Page J E. Neurospora Newslett. 1964;4:7. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raju N B. Can J Bot. 1978;56:754–763. [Google Scholar]