Abstract

Context: The constellation of endocrine patterns accompanying menopausal depression remains incompletely characterized.

Objective: Our objective was to test the hypothesis that the amplitude or phase (timing) of melatonin circadian rhythms differs in menopausal depressed patients (DP) vs. normal controls women (NC).

Design: We measured plasma melatonin every 30 min from 1800–1000 h in dim light (<30 lux) or dark, serum gonadotropins and steroids (1800 and 0600 h), and mood (Hamilton and Beck depression ratings).

Setting: The study was conducted at a university hospital.

Participants and Setting: Twenty-nine (18 NC, 11 DP) peri- or postmenopausal women participated.

Main Outcome Measures: We measured plasma melatonin (onset, offset, synthesis offset, duration, peak concentration, and area under the curve) and mood.

Results: Multi- and univariate analyses of covariance showed that melatonin offset time was delayed (P = 0.045) and plasma melatonin was elevated in DP compared with NC (P = 0.044) across time intervals. Multiple regression analyses showed that years past menopause predicted melatonin duration and that melatonin duration, body mass index, years past menopause, FSH level, and sleep end time were significant predictors of baseline Hamilton (P = 0.0003) and Beck (P = 0.00004) depression scores.

Conclusions: Increased melatonin secretion that is phase delayed into the morning characterized menopausal DP vs. NC. Years past menopause, FSH, sleep end time, and body mass index may modulate effects of altered melatonin secretion in menopausal depression.

The exact roles endocrine levels play in menopausal depression remain largely unexplained. This study reveals that depressed, peri- and postmenopausal women have increased melatonin secretion that is phase-delayed into the morning. Other factors may also modulate this secretion, including years past menopause, sleep end time, FSH level and body mass index.

Currently, 35 million women in the United States are postmenopausal. Over 1.5 million women enter menopause each year, according to the World Health Organization’s Technical Report. Depression is the number one ranked disease worldwide in women (1). The investigation of endocrine changes during menopause may clarify the role of reproductive hormones in precipitating or alleviating depressive mood changes during menopause and at other times, e.g. at puberty, during the menstrual cycle, with the use of oral contraceptives, or during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Similar to other species, the onset of human menopause associated with ovarian failure and oocyte depletion is accompanied by hypothalamic-pituitary insensitivity to estrogen, suggesting central nervous system involvement (2). Moreover, this decrease in estrogen sensitivity may contribute to changes in mood and sleep during the menopausal transition.

Estrogen and progesterone regulate and stabilize circadian systems in animals. Decreased sensitivity to estrogen in the hypothalamus at menopause thereby may culminate in circadian rhythm disturbances. Aging also is associated with loss of this regularity and stability (2). Elderly women show a greater range of circadian rhythm phases and amplitudes (3). A large laboratory study revealed no age-related increase in circadian phase dispersion but suggested age-related changes in circadian temporal organization (4).

Melatonin is one of the best markers of the circadian system in humans, when light conditions are controlled. Salivary melatonin acrophase measured in constant routine conditions occurred earlier in 10 healthy post- vs. premenopausal women (5). In studies of melatonin in mood disorders, several investigators reported lower levels of melatonin in depressed patients (DP) compared with normal controls (NC) (6,7,8,9). In contrast, in studies of depressive disorders related to the reproductive cycle, melatonin levels were higher or had a delayed offset (10,11,12,13,14,15,16) in DP compared with NC. Using urinary melatonin measures in a study of postmenopausal women controlled for age, ethnicity, season, and medications, Tuunainen et al. (13) reported significant associations between delayed offset of urinary 6-sulfatoxymelatonin excretion, a major melatonin metabolite, and current major depression as well as between later 6-sulfatoxymelatonin acrophase and lifetime major depression.

Interpreting the results of many studies of menopausal depression is hindered by a lack of hormonal measures and structured interview-based assessments of mood using diagnostic criteria. More rigorous studies that use these measures support an association between a major depressive episode (MDE) and menopause; Schmidt et al. (17) found the risk for onset of depression was 14 times higher for the 24 months surrounding women’s final menses than for a 31-yr premenopausal time period. The timing of the depressions, occurring in the context of recently elevated FSH levels, suggested an endocrine mechanism related to the perimenopause (estradiol withdrawal and recent onset of prolonged hypogonadism) was involved in the pathophysiology of perimenopausal depression. In an 8-yr study, Freeman et al. (18) reported depression probability was 4-fold greater during the menopausal transition than during the premenopausal phase. Entering menopause doubled the risk of being diagnosed with a depressive disorder and was associated with increased FSH and LH and greater variability of estradiol and FSH. Cohen et al. (19) found menopausal women were twice as likely to experience significant depressive symptoms as premenopausal women during 3 yr of follow-up. Major mood disorders occurred in 9.5% of premenopausal and 16.6% of perimenopausal women. In toto, these studies using rigorous diagnostic criteria suggest increased vulnerability for a MDE during the menopausal transition.

The primary aim of the present study was to test the hypothesis that abnormal amplitude or phase of melatonin circadian rhythms characterizes peri- or postmenopausal DP compared with NC women. Based on preliminary findings from patients with Premenstrual dysphoric disorder or a postpartum MDE, we predicted that morning melatonin secretion in particular would be increased and its offset time phase delayed (shifted later). A secondary aim was to assess the role of menopause-related factors such as reproductive hormone levels, years past menopause, sleep indices, and body mass index (BMI) as modulators of depressed mood and melatonin secretion. It was beyond the scope of this study to determine causes or treatment effects on changes in melatonin or whether they were antecedent or a consequence of menopausal depression.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

To minimize the marked hormonal variation of the perimenopause (20), NC women were postmenopausal, without menses for at least 1 yr, verified by FSH higher than 40 mIU/ml. Due to the increased risks for depression, particularly during the perimenopause, DP were peri- or postmenopausal women who met DSM-IV criteria for a MDE (21). Subjects had a history and physical examination and laboratory tests for a chemistry panel, thyroid indices, complete blood count, urinalysis, and urine toxicology screen. They had a normal PAP smear and mammogram within the last year, were nonsmokers without significant medical illness, off medication that would interfere with the melatonin measures, and off hormone replacement therapy for at least 3 months. Patients with bipolar illness were excluded. DP were off antidepressant medication for at least 2 wk (4 wk for fluoxetine) before entering the study. NC subjects had no personal history of psychiatric illness. DP and NC subjects were without alcohol abuse within the last year.

Mood assessments

All subjects underwent a structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID) to confirm diagnoses. To document mood symptoms, NC (for 4 wk) and DP (for at least 2 wk) completed daily ratings for symptoms of depression. For study inclusion, DP had mean scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) of at least 14 and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) of at least 10 for 2 wk. NC subjects had no clinically significant mood changes during the month, and mean HDRS ratings of 8 or less, and BDI ratings of 5 or less. Subjects also completed daily sleep, activity, and light exposure logs and Horne and Ostberg (H-O) (22) ratings for morningness and eveningness.

Research admissions

Subjects were admitted to the General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) of the University of California, San Diego, Medical Center. The first night was an adaptation to the sleep laboratory in which oximetry and periodic leg movements were recorded to rule out sleep disorders. On the second night, polysomnographic recordings were obtained. On the third night, serial blood samples for melatonin were collected every 30 min from 1800–1000 h. Serum samples for estradiol, progesterone, FSH, and LH were drawn at 1800 and 0600 h. Subjects were at bed rest in a single room with double doors and heavy drapery over the windows to block extraneous light from 1700–1000 h. Light panels within the room kept daytime light exposure relatively dim (<30 lux). We considered this light intensity too dim to substantially suppress melatonin in undilated pupils, disrupt sleep, or shift circadian rhythms yet not so dim that it might serve as a dark pulse. Subjects slept in the dark. Nurses or sleep technicians entered the room only when necessary (recorded by infrared camera or telecom), using a pen-size dim red flashlight. During sleep times on nights of frequent blood sampling, GCRC nurses threaded the iv catheter through a porthole in the wall and drew samples from an adjoining room to minimize sleep disturbances.

The University of California, San Diego, Institutional Review Board, approved the protocol. All subjects gave written informed consent after the procedures had been explained fully.

Assays are described below and in previously published methods (4,23,24). Plasma concentrations of melatonin were measured by RIA with kits manufactured by IBL Immuno-Biological Laboratories, Hamburg, Germany. The assay has an intraassay coefficient of variation of approximately 8% with an interassay coefficient of variation of approximately 15%. The standard range is from 12.9–1290 pmol/liter with an assay sensitivity of 10.8 pmol/liter.

Analyses

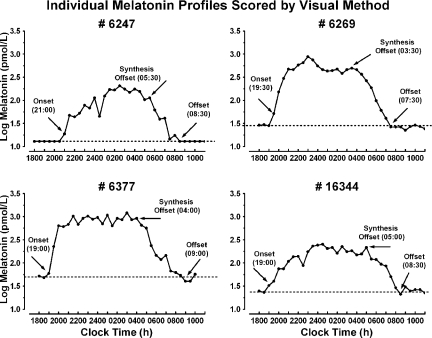

Because there is no universally accepted method for determining melatonin timing parameters, we compared threshold (25,26,27), pharmacokinetic (28), curve-fitting (29), and a visual inspection method, which defined onset as the time of the first elevated point when the slope (dy/dt) of the log-transformed melatonin concentration curve became steeply positive for at least three consecutive time points relative to the slope of the points immediately preceding it, standard offset as the first time when the slope of the descending log-transformed melatonin curve approached zero for at least three consecutive time points, and synthesis offset based on Lewy et al. (30), as the first time after the melatonin peak when the slope of the descending log-transformed melatonin curve became steeply negative for three consecutive time points. We elected to use visual inspection in subsequent data analyses because it yielded the most reliable and accurate estimates of melatonin timing parameters. For all estimates, we used the median of three visual inspection values derived from independent raters, blinded to each subject’s group. Cross-correlation analyses showed visual inspection yielded inter-rater reliabilities ranging from r = 0.913–0.999 for melatonin onset, from r = 0.801–0.925 for melatonin offset, and from r = 0.816–0.930 for synthesis offset. Figure 1 illustrates four examples of individual melatonin profiles scored by visual inspection.

Figure 1.

Sample individual log-transformed melatonin profiles scored for onset, synthesis offset, and standard offset/return to baseline using visual inspection. The dashed horizontal line represents the average of baseline values before melatonin onset.

The standard duration was defined as the difference in hours between onset and standard offset, whereas synthesis duration was defined as the difference in hours between onset and synthesis offset. We also defined the peak concentration as the single highest concentration during the nocturnal secretory episode, and area under the curve (AUC) as the integrated melatonin concentration (pmol/liter·h) from onset to standard offset.

Plasma melatonin timing and quantitative measures were analyzed with multivariate analyses of covariance (MANCOVA), followed by univariate analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) on individual variables of interest. For repeated-measures (e.g. time × diagnosis) analyses, two-factor mixed ANCOVA was used with the Geisser-Greenhouse correction for sphericity of repeated measures. Pearson correlations were calculated to assess relationships of melatonin measures to estradiol, progesterone, FSH, and LH and to covariates of interest. For some analyses, covariates were added when we found the covariate was significantly related to variables of interest. Shapiro-Wilk tests showed some variables (e.g. BMI, years past menopause, and serum FSH concentrations) were not normally distributed. These distributions were normalized by log-transformation for subsequent analyses. After preliminary analyses showed BMI, years past menopause, and H-O score were significantly correlated with mood measures and H-O score was significantly related to sleep end time (P < 0.05; sleep end time determined by polysomnographic recording on the second night in GCRC), we assessed the joint relationship of these variables to mood by calculating the multiple regression of these variables on HDRS and BDI scores, using the backward entry method, setting P = 0.100 for elimination of variables from the model.

Results

Subject characteristics

Twenty-nine menopausal women (18 NC and 11 DP) who met screening criteria were studied: 23 Caucasian, four Hispanic, one Native-American, and one multiethnic (Table 1). Ten of the 11 DP reported a prior history of MDE, from two to six previous episodes, ranging in duration from 2 wk to 8 yr. In our sample, episode frequency and duration were not significantly correlated either with age when cycle irregularity started or with age of menopause (all P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Clinical demographics of menopausal women, NC vs. DP

| Mean age ± sd | BMI ± sd | History of hormone replacement

|

Personal history of depressive illness (n) | Family history of psychiatric illness (n) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estrogen (n) | Progesterone (n) | Prempro (n) | |||||

| NC (n = 18) | 56.7 ± 7.3 | 27.0 ± 4.9 | 27.80% (5/18) | 16.70% (3/18) | 11.10% (2/18) | 0.0% (0/18) | 11.1% (2/18) |

| DP (n = 11) | 53.5 ± 3.5 | 29.0 ± 5.8 | 45.50% (5/11) | 27.30% (3/11) | 18.80% (2/11) | 100.0% (11/11) | 81.8% (9/11) |

| P | 0.187 | 0.332 | 0.346 | 0.494 | 0.592 | 0.0001 | 0.001 |

Including age as a covariate in statistical tests of outcome variables did not alter the analysis outcomes. The large differences between NC and DP in personal history of depression occurred because we excluded from study NC subjects with positive personal histories.

On the H-O scale, NC subjects had higher morningness scores than DP (F1,27 = 5.17; P = 0.031). Furthermore, DP subjects were more often moderately evening or neither types (eight of 11 = 72.7%), whereas NC subjects were more often definitely or moderately morning types (12 of 18 = 66.7%; χ2 = 6.36; P = 0.048). Higher H-O score (greater morningness) was associated with earlier plasma melatonin onset (r26 = −0.395; P = 0.025) and earlier sleep end time (r26 = −0.463; P = 0.013). When we controlled for log years past menopause and log BMI, sleep end time was correlated with HDRS score (partial r22 = 0.460; P = 0.024): earlier risers had lower HDRS scores (less depressed mood) than later risers. Thus, higher H-O score (more morning type) was associated with earlier sleep end time and lower depression ratings. Sleep end time was somewhat earlier in NC vs. DP, but not significantly so (F1,25 = 2.51; P = 0.126) when we controlled for log years past menopause and log BMI (Table 2).

Table 2.

H-O score, sleep end time, melatonin onset, synthesis offset, standard offset/return to baseline (clock time), synthesis duration, standard duration, peak, and AUC in NC vs. DP

| H-O score | Sleep end time (h:min) | Onset (h:min) | Synthesis offset (h:min) | Offset (h:min) | Synthesis duration (h) | Standard duration (h) | Peak (pmol/liter) | AUC (pmol/liter·h) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC (n = 18) | 62.2 ± 7.9 | 06:11 ± 1:01 | 19:50 ± 1:25 | 05:00 ± 2:13 | 08:48 ± 1:08 | 9.17 ± 1.75 | 12.97 ± 1.24 | 342.0 ± 205.8 | 3954 ± 2182 |

| DP (n = 11) | 54.6 ± 10.1 | 06:41 ± 0:32 | 20:16 ± 1:25 | 05:55 ± 1:23 | 09:16 ± 1:16 | 9.64 ± 1.72 | 13.00 ± 1.22 | 574.4 ± 472.0 | 7364 ± 5751 |

| P | 0.031 | 0.126 | 0.409 | 0.181 | 0.045 | 0.398 | 0.509 | 0.026 | 0.015 |

Results are presented as mean ± sd. Statistical tests were performed using log BMI and log years past menopause as covariates. Table means are presented without adjustment for covariates.

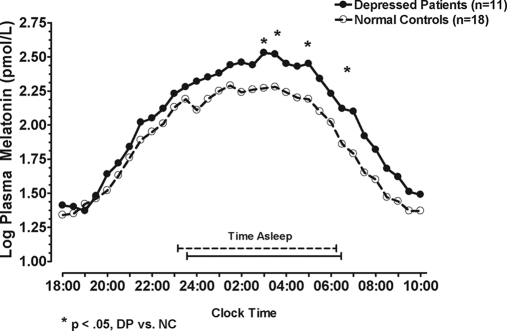

Plasma melatonin concentration

With log years past menopause and log BMI as covariates, a univariate repeated-measures ANCOVA showed log-transformed plasma melatonin levels were higher in DP than in NC from 1800–1000 h (F1,25 = 3.16; P = 0.044, one-tailed); the time × diagnosis interaction was not significant (P > 0.05) (Fig. 2). Analyses on peak and AUC measures showed a marginally significant omnibus MANCOVA (P = 0.098) when log BMI was applied as a covariate. Univariate ANCOVA showed DP exceeded NC in melatonin peak (F1,26 = 5.55; P = 0.026) and melatonin AUC (F1,26 = 6.79; P = 0.015) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Mean melatonin concentrations from 1800–1000 h in NC and DP. Statistical tests were performed with covariates (log years past menopause and log BMI). Plotted values are presented without covariate adjustment. *, Time points where DP melatonin concentration was significantly greater than NC (P < 0.05).

Plasma melatonin timing (onset, standard offset, and duration)

Analyses on melatonin timing parameters showed a nonsignificant overall MANCOVA for the diagnosis effect (P > 0.05) when log years past menopause and log BMI were included as covariates. Because our a priori hypothesis, based on preliminary data from menopausal, postpartum, and menstrual cycle women, was that DP would have a delayed melatonin offset time and longer duration, we examined the univariate ANCOVA, which showed melatonin offset occurred later in DP than in NC (0916 vs. 0848 h; F1,25 = 3.14; P = 0.045, one-tailed); melatonin onset times and durations of DP and NC did not differ significantly (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

Melatonin synthesis variables

Melatonin synthesis offset, including duration and AUC, were not significantly different between DP and NC (P > 0.05). The Shapiro-Wilk test showed synthesis offset and duration measures were nonnormally distributed. Therefore, data were log-transformed to normalize the distributions, and the MANCOVA was repeated. As with the untransformed data, the overall MANCOVA was nonsignificant (Table 2).

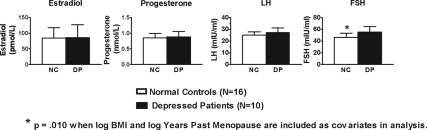

Reproductive hormones

Estradiol, progesterone, FSH, and LH values appear in Fig. 3 (means of 1800- and 0600 -h values). Univariate ANCOVA showed serum FSH was greater in DP than NC (F1,22 = 8.02; P = 0.010) with log years past menopause and log BMI as covariates in the analysis. The NC and DP did not differ significantly in serum estradiol, progesterone, and LH levels (all P > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Mean (± se) of estrogen, progesterone, LH, and FSH in menopausal NC and DP. Statistical tests were performed with covariates (log years past menopause and log BMI). Plotted values are presented without covariate adjustment.

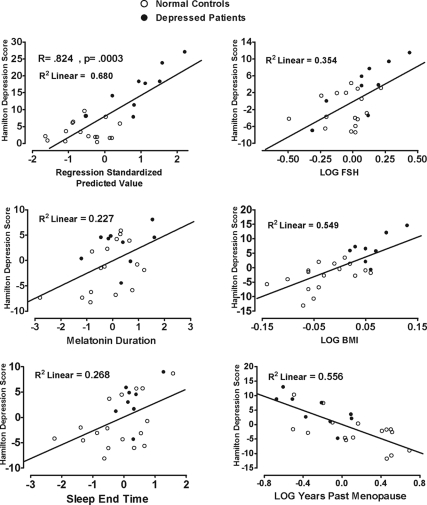

Predicting magnitude of mood disturbance from melatonin timing, reproductive hormone, demographic, and sleep parameters

In light of the analyses showing BMI, years past menopause, and H-O score were significantly correlated with mood measures (P < 0.05), and H-O score was significantly related to sleep end time, we assessed the joint contribution of these variables to mood by determining their multiple regression on HDRS and BDI scores. After removing one extreme outlier (whose values deviated from the regression line by approximately 3 sd from the dependent variable mean), the analysis showed scores on the HDRS (R = 0.824; P = 0.0003) and BDI (R = 0.864; P = 0.00004) were highly predictable from plasma melatonin standard duration, log-transformed BMI, log-transformed years past menopause, log-transformed FSH, and sleep end time. The model revealed significant contributions to HDRS score of melatonin duration (partial r = 0.477; P = 0.029), log FSH (partial r = 0.595; P = 0.004), log BMI (partial r = 0.741; P = 0.0001), log years past menopause (partial r = −0.745; P = 0.0001) and sleep end time (partial r = 0.518; P = 0.016); all P values are two-tailed. In combination, these variables accounted for 59.5% of the variance in HDRS scores (with R2 adjusted for number of predictor variables). Scattergrams representing the partial correlation relationships for each of these variables to HDRS score are presented in Fig. 4. Notably, melatonin onset, offset, synthesis offset, and synthesis duration did not contribute significantly to prediction; nor did estradiol, progesterone, and LH (all P > 0.10).

Figure 4.

Relationship of BMI, FSH, sleep end time, years past menopause, and melatonin duration to baseline HDRS score in NC (○) and DP (•) combined. Each scatter graph shows the partial correlation between a predictor variable and HDRS score when controlled for all other predictor variables. Scales are regression standardized for each variable.

The regression of the predictor variables (log BMI, log FSH, log years past menopause, and sleep end time) on melatonin measures showed melatonin variables were not significantly correlated with the other predictor variables, with one exception: melatonin standard duration was positively correlated with log years past menopause (r = 0.591; P = 0.004). Thus, plasma standard melatonin duration increased with years past menopause.

Discussion

In summary, plasma melatonin samples obtained from menopausal DP in the light-controlled environment of the GCRC showed increased melatonin secretion and delayed morning offset compared with NC women.

Melatonin secretion begins before sleep onset and declines near sleep offset. Higher melatonin levels or delayed offset in DP might be caused by long sleep duration or by a long interval of darkness, possibly from a long time in bed in women who may be trying to compensate for sleep disturbances (31,32). Poor sleep at night also could induce more naps, which alter the phase of melatonin and increase daytime secretion (23,33). Consistent with the role of increased melatonin duration in photoperiodic regulation of mammalian seasonality, the duration of melatonin secretion, especially delayed offset, may be causal in the occurrence of menopausal MDE or may be secondary to them. Depression may increase and contribute to longer sleep in postmenopausal women (34). Supporting an etiological role of delayed melatonin offset in depression are data emphasizing therapeutic effects of interventions that make melatonin offset earlier: early morning bright light and propranolol (35,36).

Several hypothetical mechanisms could explain pathological increases in the amplitude and/or duration of melatonin secretion. In order of priority, we think the most likely explanation in our sample is decreased light exposure, for which we have preliminary evidence (10). Long nights, sometimes caused by nocturnal awakenings in dim light, sleeping during the day caused by nocturnal awakenings, or reduced daylight, especially morning daylight, could increase the amplitude or duration of melatonin secretion. Compared with complete darkness, low levels of light at night lengthen the duration of nocturnal activity in hamsters (37). This increased activity time reflects a longer duration of melatonin secretion (longer biological night) and altered coupling of circadian oscillators comprising the circadian pacemaker (37,38). Additional explanations that we were not able to test in this study include possible genetic predisposition, altered neurotransmitter or receptor function regulating the melatonin-generating system (e.g. serotonin, its precursor, or norepinephrine, its synthesis regulator), and increased amplitude of the underlying circadian pacemaker.

Our melatonin findings in menopausal DP are similar to those of patients with seasonal affective disorder, whose atypical depressive symptoms occur in association with increased melatonin duration during the winter months (11). The findings also are consistent with our recent observations in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder, in whom melatonin duration increases in the late luteal phase, when they are symptomatic, compared with the follicular phase, when they are asymptomatic (unpublished data). Treatments that reduce morning melatonin secretion in particular, such as morning bright light, may improve mood in DP by reducing melatonin secretion at a critical interval and shifting its timing with respect to sleep. In support of this hypothesis, in postmenopausal women, morning illumination was associated with better mood and sleep, particularly for subjects whose body clocks were delayed (39). In the present study, increased depressive ratings on the HDRS were associated with increased melatonin duration, higher H-O scale eveningness scores, and a trend for later sleep end time. In contrast, women who were morning types tended to have earlier sleep onset and offset times and, as a result, were more likely to have more morning light exposure, decreased morning melatonin secretion duration, and less depressed mood. Our current findings in menopausal DP are in contrast to other patients with a MDE who have early morning awakening and whose circadian rhythms are shifted earlier.

Although our data suggest menopausal depression is related to parameters of melatonin secretion, endocrine, sleep, and body mass indices also may modulate depression vulnerability. Our finding of elevated FSH levels in menopausal DP compared with NC, and the substantial correlation between log FSH levels and scores on standard measures of objective (interview-based) and subjective assessments of depression (HDRS and BDI, respectively) parallels the findings from Freeman et al. (18) in which increased FSH levels also were associated with higher depression ratings. Our results also document the substantial contributions of BMI, sleep end time, and years past menopause to HDRS score and melatonin duration, and the importance of using these variables as covariates in analyses in future studies. The contribution of BMI to depression severity also is reported in recent studies showing an association between obesity and depression, especially in women (40). Despite the absence of a difference in chronological age between NC and DP, DP may be more aged biologically than NC, possibly due to experiencing more stress in their lives, because stress may lead to premature aging in humans.

The strengths of this study include careful diagnostic assessments of depression using interview-based assessments by trained mental health professionals, circadian sampling of plasma melatonin, and inclusion of endocrine and sleep measures as modulating variables. The limitations of this study include a relatively small sample size, drawn from a heterogeneous population (in terms of age and years past menopause) in a cross-sectional design. Because blood was sampled only from 1800–1000 h in some subjects, accurate estimations of melatonin onsets or offsets occurring outside of this range could not be made in these cases.

Our findings suggest directions for future research into the endocrine contributions to menopausal and other depressive disorders related to the reproductive cycle in women.

Acknowledgments

Daniel F. Kripke, M.D., provided valuable scientific consultation and Alan Turken provided valuable technical support in performing biochemical assays.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant MH-59919, National Institutes of Health Clinical Research Center Grant M01-RR-00827, and Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center and Veterans Affairs Merit Review (R.H.).

Results from this work were presented in part at the 88th Annual Meeting of The Endocrine Society, Boston, MA, 2006.

Disclosure Information: All authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online November 6, 2007

Abbreviations: ANCOVA, Analyses of covariance; AUC, area under the curve; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BMI, body mass index; DP, depressed patients; GCRC, General Clinical Research Center; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; H-O, Horne and Ostberg; MANCOVA, multivariate analyses of covariance; MDE, major depressive episode; NC, normal controls.

References

- Stoppe G, Doren M 2002 Critical appraisal of effects of estrogen replacement therapy on symptoms of depressed mood. Arch Women Ment Health 5:39–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise PM, Krajnak KM, Kashon ML 1996 Menopause: the aging of multiple pacemakers. Science 273:67–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngstedt SD, Kripke DF, Elliott JA 1997 Distribution of melatonin circadian phase among the elderly. San Francisco: Association of Professional Sleep Societies [Google Scholar]

- Kripke DF, Youngstedt SD, Elliott JA, Tuunainen A, Rex KM, Hauger RL, Marler MR 2005 Circadian phase in adults of contrasting ages. Chronobiol Int 22:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters JF, Hampton SM, Ferns GA, Skene DJ 2005 Effect of menopause on melatonin and alertness rhythms investigated in constant routine conditions. Chronobiol Int 22:859–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck-Friis J, Kjellman BF, Aperia B, Unden F, von Rosen D, Ljunggren JG, Wetterberg L 1985 Serum melatonin in relation to clinical variables in patients with major depressive disorder and a hypothesis of a low melatonin syndrome. Acta Psychiatr Scand 71:319–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claustrat B, Chazot G, Brun J, Jordan D, Sassolas G 1984 A chronobiological study of melatonin and cortisol secretion in depressed subjects: plasma melatonin, a biochemical marker in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 19:1215–1228 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendlewicz J, Linkowski P, Branchey L, Weinberg U, Weitzman ED, Branchey M 1979 Abnormal 24 hour pattern of melatonin secretion in depression. Lancet 2:1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair NP, Hariharasubramanian N, Pilapil C 1984 Circadian rhythm of plasma melatonin in endogenous depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 8:715–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry BL, Meliska CJ, Martinez LF, Basavaraj N, Zirpoli GG, Sorenson D, Maurer EL, Lopez A, Markova K, Gamst A, Wolfson T, Hauger R, Kripke DF 2004 Menopause: neuroendocrine changes and hormone replacement therapy. J Am Med Womens Assoc 59:135–145 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehr TA, Duncan Jr WC, Sher L, Aeschbach D, Schwartz PJ, Turner EH, Postolache TT, Rosenthal NE 2001 A circadian signal of change of season in patients with seasonal affective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58:1108–1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaicher W, Speck E, Imhof MH, Gruber DM, Schneeberger C, Sator MO, Huber JC 2000 Melatonin in postmenopausal females. Arch Gynecol Obstet 263:116–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuunainen A, Kripke DF, Elliott JA, Assmus JD, Rex KM, Klauber MR, Langer RD 2002 Depression and endogenous melatonin in postmenopausal women. J Affect Disord 69:149–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kripke DF, Youngstedt SD, Rex KM, Klauber MR, Elliott JA 2003 Melatonin excretion with affect disorders over age 60. Psychiatry Res 118:47–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekula LK, Lucke JF, Heist EK, Czambel RK, Rubin RT 1997 Neuroendocrine aspects of primary endogenous depression. XV. Mathematical modeling of nocturnal melatonin secretion in major depressives and normal controls. Psychiatry Res 69:143–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou JN, Liu RY, van Heerikhuize J, Hofman MA, Swaab DF 2003 Alterations in the circadian rhythm of salivary melatonin begin during middle-age. J Pineal Res 34:11–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt PJ, Haq N, Rubinow DR 2004 A longitudinal evaluation of the relationship between reproductive status and mood in perimenopausal women. Am J Psychiatry 161:2238–2244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Nelson DB 2006 Associations of hormones and menopausal status with depressed mood in women with no history of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63:375–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LS, Soares CN, Vitonis AF, Otto MW, Harlow BL 2006 Risk for new onset of depression during the menopausal transition: the Harvard study of moods and cycles. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63:385–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro N, Brown JR, Adel T, Skurnick JH 1996 Characterization of reproductive hormonal dynamics in the perimenopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81:1495–1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1994 American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association [Google Scholar]

- Horne JA, Ostberg O 1976 A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int J Chronobiol 4:97–110 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon IY, Kripke DF, Elliott JA, Langer RD 2004 Naps and circadian rhythms in postmenopausal women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 59:844–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DC, Hopper BR, Lasley BL, Yen SS 1976 A simple method for the assay of eight steroids in small volumes of plasma. Steroids 28:179–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewy AJ, Sack RL, Singer CM 1985 Immediate and delayed effects of bright light on human melatonin production: shifting “dawn” and “dusk” shifts the dim light melatonin onset (DLMO). Ann NY Acad Sci 453:253–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry BL, Berga SL, Kripke DF, Klauber MR, Laughlin GA, Yen SS, Gillin JC 1990 Altered waveform of plasma nocturnal melatonin secretion in premenstrual depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 47:1139–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klerman EB, Gershengorn HB, Duffy JF, Kronauer RE 2002 Comparisons of the variability of three markers of the human circadian pacemaker. J Biol Rhythms 17:181–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamst A, Wolfson T, Parry B 2004 Local polynomial regression modeling of human plasma melatonin levels. J Biol Rhythms 19:164–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straume M, Frasier-Cadoret SG, Johnson ML 1991 Least squares analysis of fluorescence data. In: Lakowicz JR, ed. Topics in fluorescence spectroscopy. New York: Plenum; 117–240 [Google Scholar]

- Lewy AJ, Cutler NL, Sack RL 1999 The endogenous melatonin profile as a marker for circadian phase position. J Biol Rhythms 14:227–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehr TA 1998 Effect of seasonal changes in daylength on human neuroendocrine function. Horm Res 49:118–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehr TA 1999 The impact of changes in nightlength (scotoperiod) on human sleep. In: Turek FW, Zee PC, eds. Regulation of sleep and circadian rhythms. New York: Marcel Dekker; 263–285 [Google Scholar]

- Cajochen C, Knoblauch V, Renz C, Kräuchi A, Wirz-Justice A 2002 Multiple napping enhances daytime melatonin levels in constant dim light. Chronobiol Int 19:963–1000 [Google Scholar]

- Kripke DF, Brunner RL, Freeman R, Hendrix S, Jackson RD, Masaki K, Carter RA 2001 Sleep complaints of postmenopausal women. Clin J Women’s Health 1:244–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terman JS, Terman M, Lo ES, Cooper TB 2001 Circadian time of morning light administration and therapeutic response in winter depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58:69–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlager DS 1994 Early-morning administration of short-acting β-blockers for treatment of winter depression. Am J Psychiatry 151:1383–1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman MR, Elliott JA, Evans JA 2003 Plasticity of hamster circadian entrainment patterns depends on light intensity. Chronobiol Int 20:233–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman MR, Elliott JA 2004 Dim nocturnal illumination alters coupling of circadian pacemakers in Siberian hamsters, Phodopus sungorus. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol 190:631–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngstedt SD, Leung A, Kripke DF, Langer RD 2004 Association of morning illumination and window covering with mood and sleep among post-menopausal women. Sleep Biol Rhythms 2:174–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre RS, Konarski JZ, Wilkins K, Soczynska JK, Kennedy SH 2006 Obesity in bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: results from a national community health survey on mental health and well-being. Can J Psychiatry 51:274–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]