Abstract

Antagonist peptides inhibit T cell responses by an unknown mechanism. By coexpressing two independent T cell receptors (TCRs) on a single T cell hybridoma, we addressed the question of whether antagonist ligands induce a dominant-negative signal that inhibits the function of a second, independent TCR. The two receptors, Vα2Vβ5 and Vα2Vβ10, restricted by H-2Kb and specific for the octameric peptides SIINFEKL and SSIEFARL, respectively, were coexpressed on the same cell. Agonist stimulation demonstrated that the two receptors behaved independently with regard to antigen-induced TCR downregulation and intracellular biochemical signaling. The exposure of one TCR (Vα2Vβ5) to antagonist peptides could not inhibit a second independent TCR (Vα2Vβ10) from responding to its antigen. Thus, our data clearly demonstrate that these antagonist ligands do not generate a dominant-negative signal which affects the responsiveness of the entire cell. In addition, a kinetic analysis showed that even 12 h after engagement with their cognate antigen and 10 h after reaching a steady-state of TCR internalization, T cells were fully inhibited by the addition of antagonist peptides. The window of susceptibility to antagonist ligands correlated exactly with the time required for the responding T cells to commit to interleukin 2 production. The data support a model where antagonist ligands can competitively inhibit antigenic peptides from productively engaging the TCR. This competitive inhibition is effective during the entire commitment period, where sustained TCR engagement is essential for full T cell activation.

Keywords: T cell receptor antagonist, T cell activation, T cell commitment

Tcell activation depends on the specific recognition of peptides presented in the binding groove of MHC molecules (1, 2). The binding of the peptide/MHC ligand to the TCR leads to the tyrosine phosphorylation of TCR-associated proteins, recruitment of kinases and adapters, and activation of intracellular signaling pathways (3–6). Interestingly, T cells can differentially respond to subtle changes in either the MHC or peptide ligand. Substitutions in TCR contact residues can give rise to antagonist ligands that do not elicit any measurable T cell effector functions, but are able to diminish or even abrogate the response to the nominal antigen when both the agonist and antagonist are simultaneously displayed on APCs (7–11).

Various models have been proposed to explain the mechanistic basis for the differential response to antagonist ligands by the same TCR and its translation into altered signaling and T cell activation (12–16). First, a quantitative model has been put forward which proposes that TCR antagonism is due to the fact that antagonist ligands interact nonproductively with the TCR, and competitively inhibit antigenic ligands from productively engaging the TCR. This competition might disturb the formation of necessary signaling oligomers (7, 12, 17–19). This model is supported by studies showing that several antagonist ligands fail to induce TCR-dependent signaling events such as the generation of sustained Ca2+ flux and turnover of the inositol phosphates (7, 9, 17, 20–22) as well as exhibit lower affinities and faster off-rate kinetics for the TCR than antigenic ligands (23–25).

In contrast, various qualitative models have been proposed where antagonist ligands induce a TCR-mediated differential (8, 9, 16, 21, 26–28) or even negative signal (13, 14, 29, 30). One model attributes the induction of a negative signal to an inappropriate conformational change induced by antagonist ligands (14, 31). In contrast, another model proposes that quantitative differences in TCR/ ligand binding translate into a negative intracellular signal (29). Studies of positive selection of immature thymocytes by antagonist ligands in fetal thymic organ culture have shown that these ligands are in fact capable of delivering a signal through the TCR (32–34). Moreover, several groups have demonstrated that altered peptide ligands, with partial agonist or with even pure antagonist properties, were able to initiate some but not all of the early biochemical events associated with TCR signaling (26–28). Although these experiments provided evidence for the induction of differential signaling events induced by partial agonist and antagonist ligands, they were not able to distinguish whether the observed inhibitory effect was due to an induced negative signal or to incomplete activation based on the faster TCR dissociation from the antagonist/MHC complex (24, 25).

In the present study, we have addressed the mechanism of antagonism induced by antagonist ligands using T cell hybridomas coexpressing two independent TCRs. If antagonist ligands induced signals with negative regulatory characteristics, then stimulation through one receptor should be inhibitable by antagonizing the other. Our data clearly demonstrate that the antagonist ligands we examined do not generate such an intracellular dominant-negative signal which inhibits the stimulation of a second independent TCR. The two TCRs, expressed on the same cell, behaved independently with regard to antigen-induced TCR internalization as well as intracellular biochemical signaling. Interestingly, the T cell hybridoma could be inhibited by antagonist peptides far beyond the time point of maximal antigen-induced TCR internalization. The fact that the window of sensitivity to antagonist peptides correlated exactly with the time required for the cells to commit to activation supports a competitive model to explain TCR antagonism.

Materials and Methods

DNA Constructs.

The OVA-TCR-1 (OT-I) is comprised of rearranged TCR α (Vα2-Jα26) and TCR β (Vβ5-Dβ2-Jβ2.6) chains and is derived from the Kb-restricted, OVA257-264-specific CTL clone, 149.42 (35). The cDNA encoding the TCR α chain was cloned into the G418 resistant retroviral vector, LXSN (36– 38). Similarly, the OT-I TCR β chain was cloned into the puromycin resistant retroviral vector, LXSP (39). The TCR β chain (Vβ10-Dβ2-Jβ2.5), when paired with the OT-I Vα2 chain, confers specificity for the Herpes simplex viral peptide, SSIEFARL (40). The Vβ10 cDNA was cloned into LXSP as well. The cDNAs encoding CD8α and CD8β were kindly provided by P. Cosson (University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland). The CD8α cDNA was cloned into the retroviral vector LXSHD, which expresses a histidinol resistance gene, while the CD8β cDNA was similarly cloned into the retroviral vector LXSH, containing a hygromycin resistance gene. LXSHD and LXSH were provided by A. Kazlauskas (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA).

Cells.

The TCR-α−/β− T hybridoma, 58, has been described previously (41). The 58CD8α/β cells were generated by sequentially infecting the original cell line 58 with supernatants containing viruses encoding CD8α and CD8β. Subsequently, the TCR α and β chains were transfected by retroviral infection of 58CD8α/β to obtain cell lines expressing a single TCR (Vα2Vβ5 or Vα2Vβ10). Similarly, retroviral infection and cell sorting was used to generate a cell line coexpressing two TCRs (Vα2Vβ5 and Vα2Vβ10). The P1.32Kb cell line, directed from the cell line P815 by transfection of a DNA construct encoding the MHC class I molecule Kb (42), was used for peptide presentation. All cells were grown in IMDM supplemented with 1.5% heat inactivated FCS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol. The indicator cell line HT-2 (43) was grown in IMDM containing 5% FCS with the addition of 250 U/ml recombinant IL-2. The ecotropic packaging cell line Bosc23 was purchased from American Type Culture Collection and grown in IMDM containing 10% FCS.

Transfection and Infection.

Bosc23 packaging cell line was transfected as described previously (44). The supernatant containing retroviral particles was used to infect the 58 T cell hybridoma. Briefly, 5 × 105 58 cells were resuspended in 100 μl IMDM, and 1 ml retroviral supernatant containing 40 μg DEAE-dextran was added. After 6–12 h, 5 ml of fresh IMDM and the appropriate selective drug was added (1 mg/ml G418 [GIBCO BRL], 3 μg/ml puromycin [Sigma Chemie], 2 mM histidinol [Sigma Chemie], or 0.5 mg/ml hygromycin [Calbiochem]). The surviving cells were analyzed after 5–7 d and sorted for surface expression by FACS®. In all experiments at least two independently generated T cell hybridoma lines were compared, and similar results were obtained. Transfected cells were always maintained in medium containing the selective drugs.

Peptides.

The peptides were synthesized at the Basel Institute for Immunology using FastMocTM chemistry on 430A peptide synthesizer (Applied Biosystems). The amino acid sequences were the following: SIINFEKL (Vα2Vβ5-specific antigen), EIINFEKL (Vα2Vβ5-specific antagonist E1), SIINFEPL (Vα2Vβ5-specific antagonist P7), SIIKFEKL (the control peptide K4), and SSIEFARL (Vα2Vβ10-specific antigen).

Antibodies.

The anti-Vβ5 mAb, MR9-4 (44), anti-CD3ε mAb, 2C11 (45), and anti-ζ mAb, H146-968 (46), were purified from culture supernatants using protein G (Pharmacia). The anti-Vα2.1–specific mAb, B20.1 (47), the anti-Vβ10 mAb, B21.5 (48), and the anti-Kb mAb, AF6-88.5 (49), were purchased from PharMingen. The anti-phosphotyrosine mAb, 4G10, was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology. To detect bound anti-ζ antibodies in Western blots, we used goat anti–rabbit antibodies labeled with horseradish peroxidase (HRPO)1 from Southern Biotechnology Associates. The blocking anti-Kb mAb, provided by J. Bluestone, was purified from culture supernatants using protein A (50).

Quantitation of TCR Surface Expression.

To calculate the relative amount of the two TCRs (Vα2Vβ5 and Vα2Vβ10) coexpressed on the same hybridoma cell, the expression of each TCR β chain (measured by staining with the appropriate anti-Vβ mAb) was normalized to the total amount of TCR expressed on the surface (measured by staining with an anti-Vα2 mAb). The ratio of Vβ5/Vα2 or Vβ10/Vα2 staining on cells expressing a single TCR was taken as 100%. On the surface of the hybridomas expressing two TCRs, Vα2Vβ5 and Vα2Vβ10 heterodimers accounted for 60 and 40% of the surface TCRs, respectively.

Stimulation Assays.

90 μl containing 5 × 104 P1.32Kb cells was plated in flat-bottomed 96-well plates and incubated with 10 μl peptide for 4 h at 37°C. 8 × 104 T hybridoma cells in 100 μl medium were subsequently added. After a further 25 h of incubation at 37°C, the supernatant was harvested and assayed for IL-2.

Antagonism Assays.

P1.32Kb cells were first loaded for 4 h at 37°C with the indicated amount of agonist peptide and unbound peptide was removed by washing. Peptide loaded cells (5 × 104/ 90 μl) were plated in flat-bottom 96-well plates. 10 μl of antagonist peptides, or 10 μl of control peptide or medium alone was added and the cultures were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. 8 × 106 T hybridoma cells in 100 μl were then added and incubated for 25– 27 h at 37°C. The supernatant was harvested and analyzed for the presence of IL-2.

IL-2 Assay.

IL-2 content was determined by incubating 2 × 103 HT-2 cells per well in round-bottom 96-well plates with serial dilutions of culture supernatant for 24 h. Alamar blue substrate (Alamar Biosciences) was then added and IL-2 titer was determined by comparison to a standard curve generated using recombinant murine IL-2 (PharMingen) using SOFTmaxPro version 1.1 software.

FACS® Analysis of TCR Downregulation.

The stimulation of the T cell hybridomas was carried out in parallel and under the same conditions as the antagonism assays mentioned above. To ensure conjugate formation, cells were centrifuged briefly. Similar results were obtained with round- or flat-bottom 96-well plates. After 3 h of stimulation at 37°C, cells were washed once in PBS containing 1% FCS and 0.05% azide, and stained with saturating amounts of PE-conjugated anti-Vα2.1 mAb (B20.1) and, in the case of the double TCR expressing cells, with biotinylated anti-Vβ5 (MR9-4) or anti-Vβ10 (B21.5) mAbs. For the anti-Vβ10 mAb, streptavidin-APC (PharMingen) was used as a second step labeling reagent. The P1.32Kb cells were excluded by staining with anti-Kb FITC labeled mAb (AF6-88.6). Dead cells were excluded by staining with 0.5 μg/ml propidium iodide (Molecular Probes). Results were analyzed using CellQuest version 3.1 software.

Tyrosine Phosphorylation Assays.

For antigen presentation, the cell line P1.32Kb was loaded either with medium alone or with antigenic peptides, 10 μM SSIEFARL or 1 μM SIINFEKL, in a 24-well plate overnight (7.5 × 105 cells/well in 1 ml 1.5% FCS IMDM). 107 responding T cell hybridomas were then added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Cells were harvested and cell pellets were lysed for 20 min in 1 ml of 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM Tris-NCl, pH 7.4, and 150 mM NaCl. To prevent degradation, the lysis buffer was supplemented with 10 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM orthovanadate, and 100 μM pervanadate (made from a fresh stock solution of 10 nM orthovanadate and 15 mM H2O2). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Vβ5, anti-Vβ10 mAbs, or anti-CD3ε, respectively, and resolved by SDS-PAGE as described previously (51). Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose and the membrane was blocked with 1% BSA/TBS 0.1% NP-40 (BSA stock solution; Pierce) for 20 min at room temperature. Blots were probed with 1 μg/ml of the biotinylated antiphosphotyrosine mAb, 4G10 (Upstate Biotechnology) for 1 h at room temperature in 1% BSA/TBS 0.1% NP-40. Bound 4G10 antibodies were visualized with streptavidin-HRPO (1:50,000; Southern Biotechnology Associates) and an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Pierce).

Anti-ζ Blot.

After phosphotyrosine detection, HRPO was inactivated by incubating the nitrocellulose membranes with 3% H2O2/H2O for 15 min at room temperature. Subsequently nonspecific binding was blocked with 5% milk/PBS 0.1% NP-40 (nonfat dry milk; BioRad) for 20 min at room temperature. Blots were probed with 100 ng/ml biotinylated anti-ζ mAb H146-968 for 1 h at room temperature. Bound anti-ζ antibodies were visualized with goat anti–hamster HRPO (1:50,000; Southern Biotechnology Associates) and an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Pierce).

Results

Antagonism in Vα2Vβ5 (OT-I) TCR Expressing T Cell Hybridomas.

To investigate the mechanism of TCR antagonism, we took advantage of the T cell hybridoma line, 58CDα/βTCR-α−/β−, which expresses the coreceptor CD8 but no endogenous TCR (41; see Materials and Methods). Using retroviral vectors, we transduced the cDNAs encoding the Vα2Vβ5 TCR, which is known as OT-I. This TCR specifically recognizes the ovalbumin peptide, SIINFEKL, bound to the MHC class I molecule Kb (9). Two antagonist peptides, E1 and P7, differing by only one residue from the antigenic peptide, have been described for this TCR (32). Optimal activation of the Vα2Vβ5 expressing hybridomas, measured by the secretion of IL-2 or IL-3 and TCR internalization, required high expression of both CD8α and CD8β, (52; and data not shown).

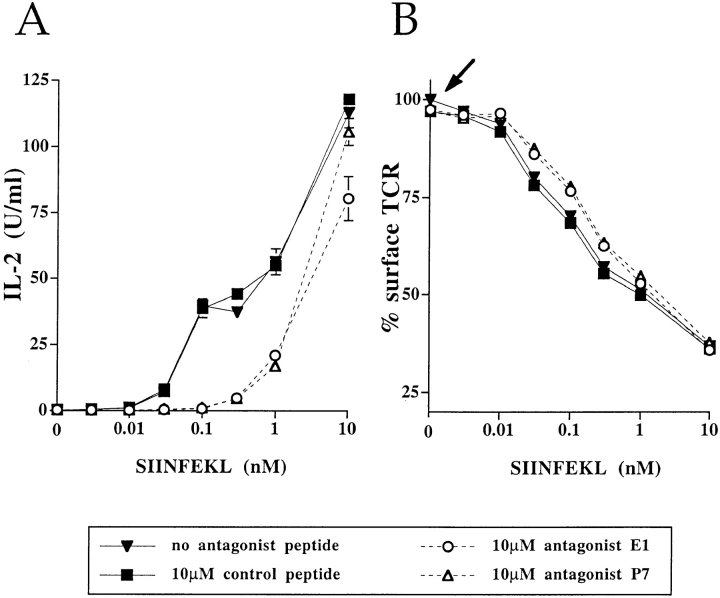

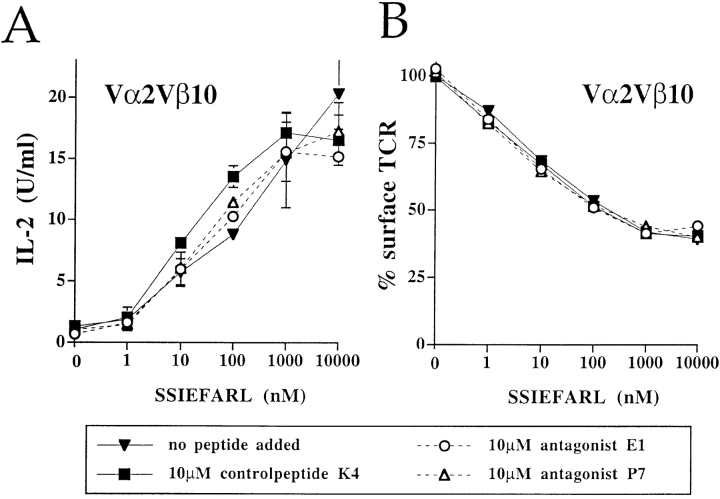

The agonist peptide was prepulsed onto the APC to ensure antigen binding as previously described for conventional antagonism assays (9). Antagonism was observed with similar characteristics described for T cell clones (Fig. 1). The Vα2Vβ5 expressing cells responded to the antigenic peptide SIINFEKL by secreting IL-2 and IL-3 in an antigen dose-dependent fashion and the presence of the antagonist peptides, E1 and P7, inhibited IL-2 and IL-3 production at suboptimal SIINFEKL concentrations (Fig. 1 A [IL-3 data not shown]). This inhibition of the response was specific for the antagonist peptides since a control MHC Kb-binding peptide, K4, neither inhibited nor potentiated the IL-2 response elicited by the peptide SIINFEKL alone (Fig. 1 A).

Figure 1.

TCR antagonism in 58CD8α/β T cell hybridomas expressing the Vα2Vβ5 (OT-I) TCR. T cell hybridomas were stimulated with their antigen, SIINFEKL, and the effect of the antagonist (E1, P7) and control (K4) peptides on IL-2 response (A) and TCR downregulation (B) was measured. The arrow highlights the data showing that, in the absence of SIINFEKL, neither the antagonists E1 and P7, nor the control peptide K4 induced TCR internalization. The IL-2 response (A) was determined after 25 h of stimulation, while the TCR downregulation (B) was analyzed after 3 h. Data are expressed as mean of triplicates in A or of duplicates in B. This experiment is representative of eight separate experiments.

Functionally triggered TCRs are internalized shortly after stimulation. Thus, downregulation of TCRs after exposure to the antigenic peptide, SIINFEKL, was used as a measure for productive TCR engagement (53, 54). As shown in Fig. 1 B, up to 75% of Vα2Vβ5 TCRs were downregulated in a dose-dependent fashion after 3 h of antigen exposure. Neither antagonist peptides alone nor the control peptide K4 affected TCR expression (Fig. 1 B, see arrow). However, both antagonist peptides, E1 and P7, modestly inhibited (by 10%) TCR downregulation induced by the antigen, SIINFEKL. Although the reversal of TCR internalization correlated with the inhibition of IL-2 secretion (Fig. 1, A and B), the effect on IL-2 secretion was more pronounced. Surprisingly, the number of internalized TCRs did not necessarily correlate with the amount of secreted IL-2. This was particularly evident when the response to 1 nM SIINFEKL was antagonized by 10 μM E1 or P7 (compare A and B in Fig. 1 and in Fig. 5). Under these conditions, TCR downregulation was not inhibited, although a significant decrease in IL-2 secretion was observed. These results suggest that in this system there is no strict correlation between the inhibition of antigen- induced TCR internalization and the effect on the IL-2 response.

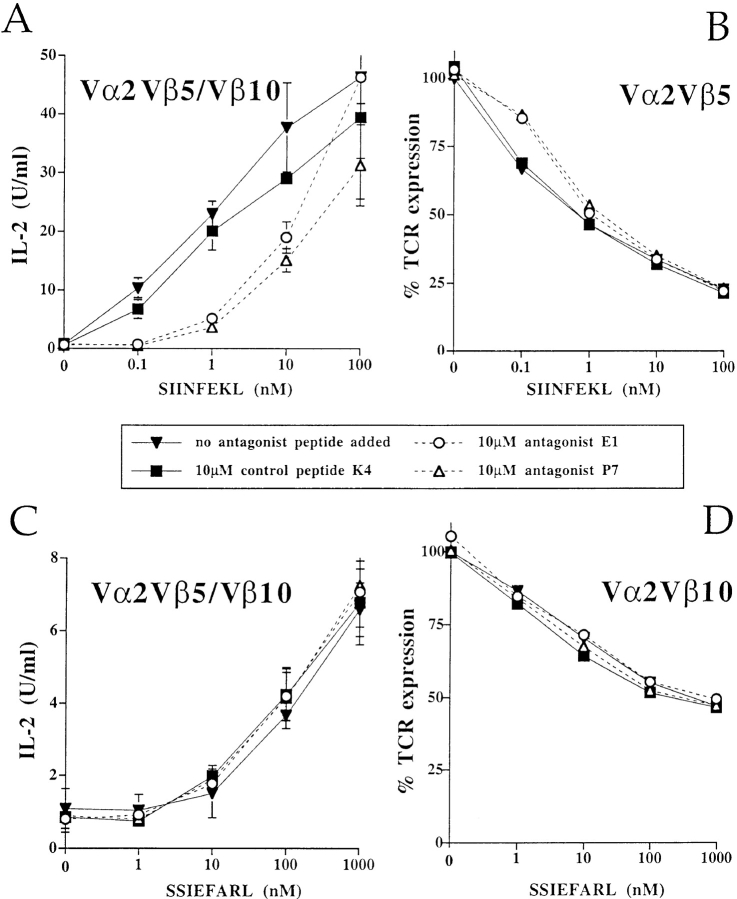

Figure 5.

Engagement of one TCR with antagonist peptides does not inhibit the activation through a second independent TCR. Analyzing cells simultaneously expressing both Vα2Vβ5 and Vα2Vβ10 TCRs on the cell surface, the Vα2Vβ5-specific antagonist peptides, E1 and P7, inhibited the IL-2 production (A) and the TCR downregulation (B) induced by the Vα2Vβ5-specific antigenic peptide, SIINFEKL. However, the Vα2Vβ5-specific antagonists, E1 and P7, did not inhibit the IL-2 response (C), nor the TCR downregulation (D) induced by the Vα2Vβ10-specific antigen, SSIEFARL. The IL-2 response (A and C) and TCR downregulation (B and D) were assayed in the same experiment. The data are representative of six separate experiments.

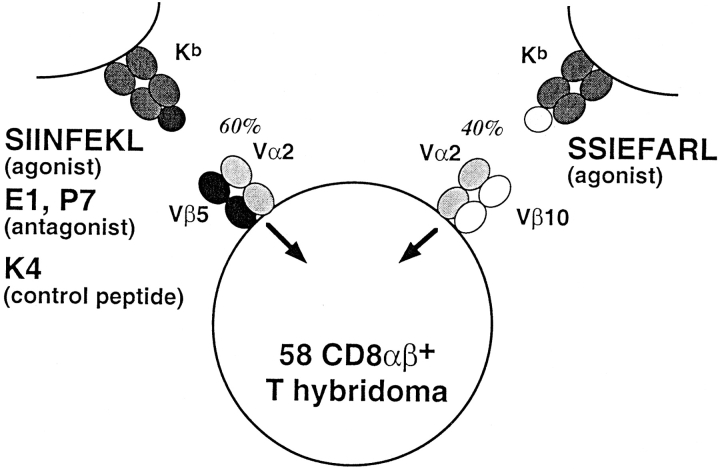

Expression of Two TCRs Which Share a Common TCR α Chain on the Same Cell.

To test the hypothesis that antagonist ligands induce intracellular, dominant-negative signals, we generated a T cell hybridoma line expressing two TCRs, which could be independently activated. This experimental design was used to determine whether positive signals derived from an antigen-stimulated TCR could be blocked by putative inhibitory signals generated by a second, antagonized TCR (Fig. 2). One receptor is the Vα2Vβ5 TCR, which is specific for the antigenic peptide, SIINFEKL, and which can be antagonized by the altered peptides, E1 and P7 (32; Fig. 1). The Vα2 chain is also present in the second receptor but is paired instead with a Vβ10 chain. This second TCR is specific for a Herpes simplex viral peptide, SSIEFARL, also presented by Kb (40).

Figure 2.

Coexpression of two peptide-specific TCRs on the surface of the same cell. One receptor is the Vα2Vβ5 TCR which is specific for the ovalbumin peptide, SIINFEKL, presented by Kb. This TCR can be antagonized by the altered peptide ligands, E1 or P7. The K4 peptide represents a control for peptide specificity since it has the similar binding affinity to Kb but is not recognized by the Vα2Vβ5 TCR. The second receptor is the Vα2Vβ10 TCR and is specific for the Herpes simplex viral peptide, SSIEFARL, bound to Kb. Both receptors were coexpressed on the T cell hybridoma line 58CD8α/β.

Since the two receptors differ only in their TCR β chains, no hybrid receptors of unknown specificities can be formed and the two receptors can easily be followed with Vβ-specific antibodies. Therefore, all observed effects can be clearly attributed to the respective receptor.

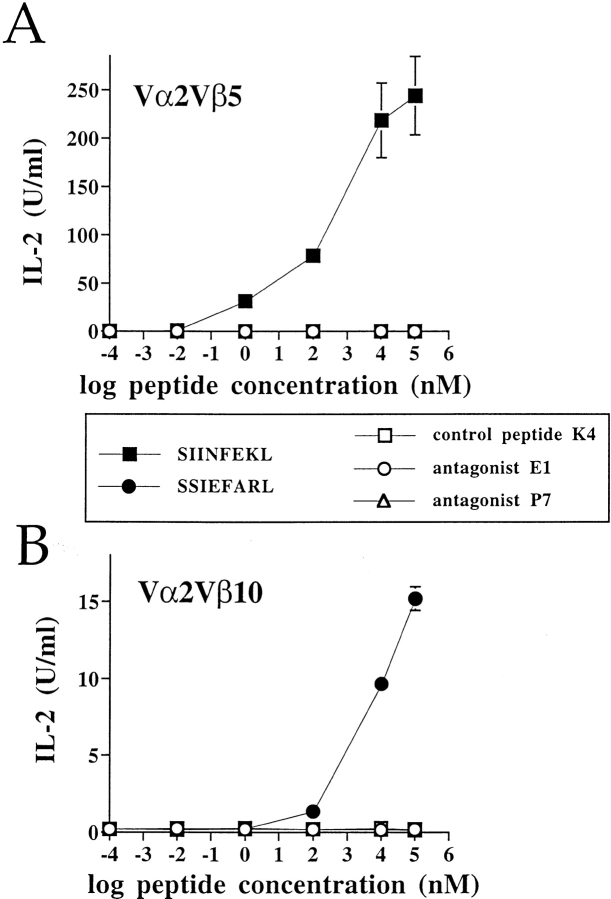

Both Agonists, SIINFEKL and SSIEFARL, and the Antagonists, E1 and P7, Are TCR Specific.

First, we determined whether the two receptors, which have a common TCR α chain, are specific for their respective antigenic peptides. T cell hybridomas expressing only one type of TCR, either Vα2Vβ5 or Vα2Vβ10, were analyzed for their IL-2 response in stimulation assays. As shown in Fig. 3 A, Vα2Vβ5 expressing cells responded only to the antigen, SIINFEKL, while Vα2Vβ10 expressing cells were stimulated only by the peptide SSIEFARL (Fig. 3 B). Neither of these TCRs was stimulated by the antagonist peptides, E1 and P7, or by the control peptide, K4 (Fig. 3, A and B). Moreover, TCR internalization completely correlated with the IL-2 responsiveness (data not shown).

Figure 3.

The two TCRs are distinctly specific for their cognate antigenic peptides. The TCRs, Vα2Vβ5 (A) and Vα2Vβ10 (B), were expressed separately on the cell line 58CD8α/β and tested for their responsiveness to various peptide analogues in stimulation assays by measuring the IL-2 production. After 25 h of stimulation, supernatants were harvested and analyzed for IL-2. This experiment is representative of two independent experiments.

A reduced IL-2 response to SSIEFARL compared to SIINFEKL (Fig. 3) was observed. However, this difference could not be attributed either to different TCR expression levels or to differences in the ability of these antigens to bind Kb. The binding affinities of the peptides to Kb, indirectly measured by their abilities to stabilize Kb expression on RMA-S cells, were equivalent (data not shown). The lower IL-2 response, induced by the SSIEFARL peptide, was likely due to weak interactions of the Vα2Vβ10 TCR with this peptide/MHC complex. Nevertheless, the IL-2 production in response to SSIEFARL demonstrated that the Vα2Vβ10 TCR was functional.

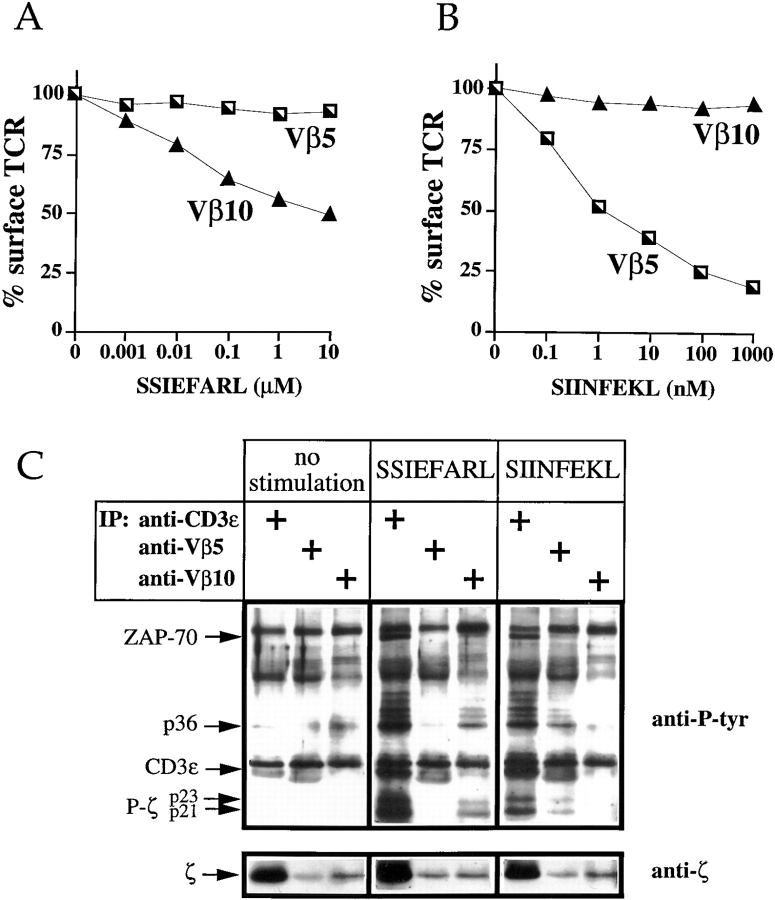

To determine if the Vα2Vβ5-specific antagonists, E1 and P7, could antagonize the Vα2Vβ10 TCR directly, cells expressing only the Vα2Vβ10 receptor were stimulated with the cognate antigen, SSIEFARL, in the presence of the Vα2Vβ5-specific antagonist peptides, E1 and P7, or the control peptide, K4. None of the peptides inhibited the IL-2 response to SSIEFARL (Fig. 4 A) or the downregulation of the Vα2Vβ10 receptor (Fig. 4 B). These results showed that the antagonists of the Vα2Vβ5 TCR did not cross-react with the Vα2Vβ10 receptor.

Figure 4.

The Vα2Vβ5-specific antagonist peptides E1 and P7 do not antagonize the response of the Vα2Vβ10 TCR to the Herpes simplex viral peptide, SSIEFARL. Vα2Vβ10 58CD8α/β hybridomas were stimulated with various concentrations of SSIEFARL in the presence of the Vα2Vβ5-specific antagonists, E1 and P7, or control peptide, K4. The IL-2 response (A) and antigen-induced TCR internalization (B) were measured in the same experiment and are representative of two independent experiments.

Antagonists of SIINFEKL Act Locally and in Cis.

Having confirmed the specificity of the two TCRs expressed on separate hybridomas, both receptors were expressed on the same cell. Two-color FACS® analysis with anti-Vβ antibodies was used to calculate that Vα2Vβ5 and Vα2Vβ10 comprised 60 and 40% of the surface TCRs, respectively (data not shown). Stimulation of the double TCR expressing cells with either the Vα2Vβ5- or Vα2Vβ10-specific antigen resulted in a low but reproducible IL-2 response (Fig. 5, A and C). Thus, both TCRs were functional when expressed at the surface of the same cell. An antagonist assay was performed by stimulating the dual expressing hybridoma cells with the Vα2Vβ5 antigen SIINFEKL, in the presence of the Vα2Vβ5-specific antagonists E1 or P7. Both antagonist peptides, but not the control peptide K4, inhibited IL-2 expression in the dual TCR expressing cells (Fig. 5 A). Additionally, the antigen-induced TCR internalization of Vα2Vβ5 receptor was slightly inhibited in the presence of the antagonists E1 and P7 similar to what was observed previously (Fig. 5 B and Fig. 1 B).

To test the hypothesis that antagonist ligands deliver a negative, trans-acting signal, the double receptor expressing cells were stimulated with the Vα2Vβ10-specific antigen, SSIEFARL, in the presence of the Vα2Vβ5-specific antagonist peptides E1 or P7. The IL-2 response to SSIEFARL, mediated by the Vα2Vβ10 TCR was unaffected in the presence of the Vα2Vβ5-specific antagonist peptides E1 or P7 (Fig. 5 C). Furthermore, the Vα2Vβ5-specific antagonists did not reverse the downregulation of the Vα2Vβ10 TCR (Fig. 5 D).

The results clearly show that antagonizing one TCR did not inhibit the stimulation through a second, independent TCR. Apparently, these antagonist ligands do not induce a dominant-negative signal that acts in trans.

Antigen-engaged TCRs Function Independently in Their Proximal Signaling Pathways.

Since the antagonized Vα2Vβ5 TCR did not interfere with the response of the stimulated Vα2Vβ10 TCR, we investigated the functional independence of the two receptors. To find out if both receptors function independently, both TCRs were monitored for antigen-induced TCR internalization. The stimulation with the Vα2Vβ5-specific antigen, SIINFEKL, resulted in downregulation of the Vα2Vβ5 TCR but not of the Vα2Vβ10 TCR (Fig. 6 A). Similarly, in response to the Vα2Vβ10-specific antigen, SSIEFARL, the Vα2Vβ10 receptor was downregulated, while no internalization of the Vα2Vβ5 receptor was detectable (Fig. 6 B). Similar results were obtained when various cell populations expressing different ratios of the two TCRs were used (not shown), supporting the observations of Valitutti et al. examining T cell clones with disparate expression of the two TCRs (53).

Figure 6.

Antigen-engaged TCRs behave independently with regard to antigen-induced TCR internalization and biochemical signaling. The double TCR expressing hybridomas were stimulated with the Vα2Vβ5-specific antigen, SIINFEKL (A), and the Vα2Vβ10-specific antigen, SSIEFARL (B). TCR downregulation of both receptors was analyzed. The data are representative of three independent assays. To study the induction of TCR-associated phosphoproteins (C), P1.32Kb APC were pulsed overnight with medium alone (no stimulation) or with the antigenic peptides, 10 μM SSIEFARL or 1 μM SIINFEKL. 107 double TCR expressing cells, Vα2Vβ5/Vβ10 58CD8α/β, were stimulated for 45 min at 37°C. Proteins in cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Vβ5 mAb (MR9-4), anti-Vβ10 mAb (B21.6), or anti-CD3ε mAb (2C11), respectively, separated on a 12% polyacrylamide gel, and transferred to nitrocellulose. The blot was probed with the anti-phosphotyrosine mAb, 4G10, and then with the anti-ζ mAb, H146-968. The arrows on the left identify the major tyrosine-phosphorylated species.

To address whether two different TCRs expressed on the surface of the same cell also behave independently in regard to biochemical signaling, T cell hybridomas expressing the two TCRs were incubated with unpulsed APCs or APCs pulsed with either the Vα2Vβ10-specific antigen, SSIEFARL, or the Vα2Vβ5-specific antigen, SIINFEKL. From cell lysates, both TCRs were either immunoprecipitated with an anti-CD3ε mAb, or independently retrieved using anti-Vβ5– or anti-Vβ10–specific mAbs. Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and blotted for the presence of phosphorylated tyrosine residues. Only low background phosphorylation of TCR-associated proteins was observed in T cell hybridomas exposed to unpulsed APCs (Fig. 6 C, lanes 1–3). In contrast, incubation with APCs pulsed with 10 μM SSIEFARL induced a strong phosphorylation of various proteins which coimmunoprecipitated with the TCR. In anti-CD3ε and anti-Vβ10 immunoprecipitates, tyrosine-phosphorylated isoforms of ζ (p21 and p23), CD3ε, ZAP-70, and a 36-kD phosphoprotein, most probably LAT, were observed (Fig. 6 C, lanes 4 and 6). To test for the phosphorylation of unstimulated bystander TCRs, the Vα2Vβ5 complex was immunoprecipitated from lysates of cells which had been stimulated with the Vα2Vβ10-specific antigen, SSIEFARL. There was no detectable induction of phosphorylation of any protein species precipitated with the Vα2Vβ5 TCR complex (Fig. 6 C, lane 5). Similar results were obtained with the reverse experiment. In stimulations with 1 μM of the Vα2Vβ5-specific antigen, SIINFEKL, only anti-CD3ε and anti-Vβ5 immunoprecipitates showed the induction of phospho-ζ (p21 and p23), CD3ε, ZAP-70, and the 36-kD phosphoprotein (Fig. 6 C, lanes 7 and 8). Immunoprecipitation of the bystander TCR, Vα2Vβ10, did not coprecipitate any of the same phosphorylated proteins (Fig. 6 C, lane 9). As the subsequent decoration of the same blot with anti-ζ showed, both anti-Vβ–specific antibodies immunoprecipitated similar amounts of ζ. The anti-CD3ε mAb was sixfold more efficient in coprecipitating ζ than both Vβ-specific mAb (Fig. 6 C, bottom).

To determine the sensitivity of detection, the eluate of cells stimulated with 10 μM antigenic peptide was serially diluted (twofold) to determine the detection limits of the phosphoproteins (data not shown). These experiments showed that as little as 5% of the phosphorylated ζ (shown in Fig. 6 C, lane 4) could be detected. Thus, the biochemical activation of bystander TCRs is very limited, if it occurs at all. The combined results demonstrate that the two TCRs expressed on the same cell are biochemically and functionally independent.

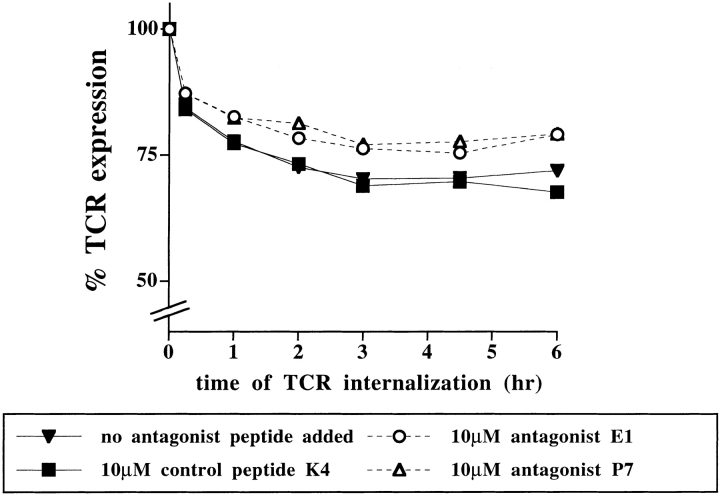

The Antagonists E1 and P7 Do Not Alter the Kinetics of TCR Internalization.

Since antagonist ligands do not induce a dominant-negative signal, antagonist peptides may outcompete agonist peptides for interaction with the TCR. As shown in Fig. 1 B antagonist ligands only slightly inhibited the antigen-induced TCR downregulation. In fact, the extent of TCR internalization in the presence of antagonist peptides did not reflect the profound inhibition of IL-2 secretion observed (Fig. 1). To assess whether antagonist peptides perturb T cell stimulation by affecting the kinetics of agonist-induced TCR downregulation, we monitored TCR internalization over time (Fig. 7). Antagonist peptides affected the extent but not the kinetics of antigen- induced TCR internalization. The full extent of TCR downregulation was reached after 2–3 h of sustained antigen exposure.

Figure 7.

The kinetics of antigen-induced TCR internalization are unaltered in the presence of antagonist ligands. P1.32Kb APCs were pulsed for 4 h at 37°C with 100 pM antigenic peptide SIINFEKL. Unbound peptides were removed and the cells were incubated for 1 h with 10 μM antagonist peptides E1 or P7, or 10 μM control peptide K4, or medium alone (no peptide added). The responders, hybridomas expressing the Vα2Vβ5 TCR, were added at various time points. T cell–APC conjugates were formed by centrifugation and all samples were harvested and stained at the same time. TCR surface expression was detected by PE- labeled anti-Vα2 (B20.1) and expressed as percentage of mean channel fluorescence of the unstimulated cells. The data are representative of four experiments.

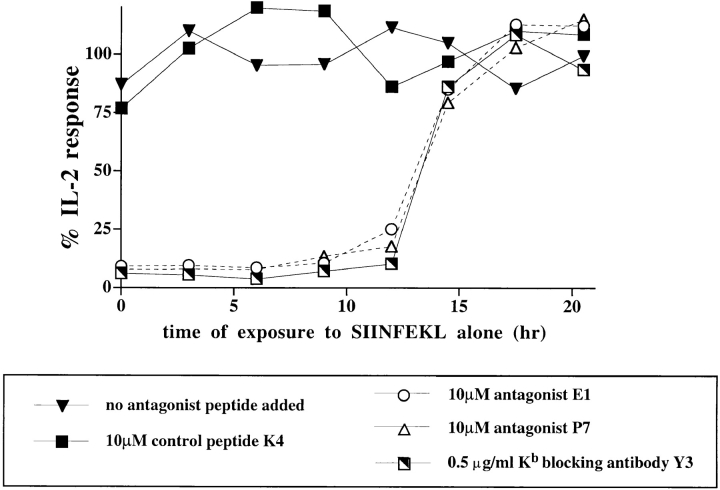

Susceptibility to Antagonism Parallels the Time of Commitment to T Cell Activation.

To better understand the events that led to antagonism, the time period when cells are sensitive to antagonist ligands was determined. T cell hybridomas, expressing the single TCR, Vα2Vβ5, were stimulated with the antigenic peptide, SIINFEKL, and antagonist peptides were added at various time points thereafter. The addition of antagonist peptides could fully inhibit the IL-2 response up to 12 h after addition of the antigen, SIINFEKL (Fig. 8). This effect was peptide-specific as the control peptide, K4, did not abrogate the IL-2 response.

Figure 8.

Susceptibility to antagonist ligands corresponds to the time of commitment. Vα2Vβ5 58CD8α/β cells were stimulated with P1.32Kb cells which had been prepulsed with 100 pM SIINFEKL peptide for 4 h at 37°C. At various time points after the initiation of the stimulation, antagonist peptides E1 or P7, control peptide K4, anti-Kb blocking antibody Y3, or medium alone were added, and the cells were resuspended. After 25 h of culture, the supernatant was harvested and assayed for IL-2 production. For more convenience, the kinetic analysis was carried out in two parts separated by 12 h. The mean of secreted IL-2 obtained in the samples where no antagonist peptides were added was set as 100%. The data are representative of four independent experiments.

To determine whether the time period during which T cells are susceptible to antagonist ligands overlapped with the time period required for T cell commitment, the Kb-specific antibody, Y3, was used to specifically block the interaction of the Vα2Vβ5 TCR with the SIINFEKL/Kb complex. The time required for sustained TCR engagement, determined using the blocking antibody, Y3, correlated exactly with the period of susceptibility to antagonist peptides (Fig. 8). The cells were irreversibly committed to IL-2 secretion only after 12 h of continuous exposure to the antigen ligand, in the absence of antagonist peptides or blocking mAbs.

Thus, antagonist ligands were able to inhibit cellular responses long after the responding T cell had interacted with its cognate antigen and achieved a reduced steady-state level of TCR expression. The T cell was fully sensitive to the inhibitory effects of antagonist ligands until it did not require further engagement with the antigen/MHC complex and was irreversibly committed to respond.

Discussion

T cell antagonism has been implicated as a potentially important mechanism in T cell activation, thymic development, escape from an antiviral immune response, and autoimmunity. Although the actual mechanism by which antagonists exert their effect is still unresolved, various models seek to explain the paradox of how the recognition of altered peptide/MHC ligands leads to altered T cell responses. Quantitative models postulate that antagonist ligands inhibit T cell responses by competing for TCR engagement with the antigenic peptide. Due to their lower affinity and faster off-rate kinetics of TCR binding (23– 25), antagonists are ineffective in initiating downstream signaling pathways but nevertheless reduce the rate of successful TCR engagements by the antigenic peptide (7, 12, 17, 19, 54, 55). In contrast, qualitative models characterize antagonists as ligands capable of delivering differential (8, 9, 16, 21, 26–28) or even negative signals to the T cell which subsequently inhibit T cell activation (13, 14, 31).

By coexpressing two TCRs of independent specificity on the same cell (Fig. 2), we were able to directly address the issue of whether a dominant-negative signal is induced by antagonist ligands. If antagonist peptides generate an intracellular dominant-negative signal, downstream from the site of TCR engagement, then antagonist ligands would be expected to inhibit the ability of a second, independent TCR to induce a cellular response. Our experimental system clearly shows that in cells expressing two TCRs, activation through one TCR is not inhibitable by engaging a second TCR with antagonist ligand (Fig. 5 C). These results are supported by the following observations, that (a) the antigenic peptide for the Vα2Vβ10 TCR, SSIEFARL, is a weak agonist (whose weak stimulatory capacity is definitely not due to weak MHC binding affinity as determined by RMA-S stabilization, data not shown). Therefore, a weak stimulation through Vα2Vβ10 should have been easily inhibitable by a putative negative signal through the Vα2Vβ5 TCR; (b) the ratio of the two TCRs expressed on the same cell favored the signals through the antagonized TCR since Vα2Vβ5, recognizing the antagonist, represented 60% of the TCR on the cell surface; and (c) all peptides were presented on the same APCs (agonist was loaded first to ensure its binding to Kb), therefore even a putative negative signal with only short-range efficacy should have been detected.

The fact that we observed no functional interference between different TCRs expressed on the same cell and no bystander TCR downregulation upon antigenic stimulation (Fig. 6, A and B) suggests that these two TCRs function independently, supporting the findings of Valitutti et al. on T cell clones (53). This is further supported by the biochemical data in hybridomas expressing two TCRs. Phosphorylated ζ and recruited phospho-ZAP-70 were only coprecipitated from TCRs engaged with their respective antigen (Fig. 6 C). These experiments argue that the phosphorylation of engaged TCRs does not spread to unengaged TCRs. It remains possible that individual cells expressing two different TCRs are intrinsically able to engage only one type of TCR. However, the simultaneous exposure of the cells to both antigenic peptides, the Vα2Vβ5-specific SIINFEKL and the Vα2Vβ10-specific SSIEFARL, presented on the same APC, induced concomitant internalization of both TCRs, indicating that both TCRs are functional on the same cell (data not shown).

Taken together, our data indicate that these antagonist ligands do not act by generating dominant-negative signals which inhibit the response of the entire cell. Therefore, we favor a quantitative model to explain TCR antagonism. Antagonist ligands have faster off-rate kinetics for TCR engagement than agonist ligands (23–25). Thus, antagonist ligands engage the TCR for a longer time than null peptides, but not long enough to induce the full signaling cascade for activation, as first suggested by the kinetic proofreading model of McKeithan (18). Although this ineffective engagement does not lead to full activation, it does generate differential biochemical signals reflected by the differential phosphorylation patterns of ζ (p21 > p23; reference 28). However, as the data from our experimental system have shown, these differential signals did not represent an intracellular, negative signal per se. As a consequence of ineffective TCR engagement, antagonist ligands prevent agonist ligands from serially engaging and triggering enough TCRs to reach the critical threshold for activation (53). This competition for TCR engagement can be observed in the inhibition of TCR downregulation in the presence of antagonist ligands (19; Fig. 1 B and Fig. 5 B). Furthermore, the quantitative mechanism of antagonist action also explains the observation that T cell responses are less efficiently inhibited when antagonists and agonist peptides are presented on different APCs (9; data not shown). Conditions which reduce the direct competition between agonist and antagonist ligands reduce the efficiency of TCR antagonism. Antagonist ligands may also influence the reorganization of TCRs which may be required for full activation (55–57).

Although our data indicate that these antagonist ligands do not induce an intracellular negative signal, downstream from TCR engagement, there are potentially some limitations to the interpretation of our results. It is possible that for some unknown reason, the Vα2Vβ10 receptor could not be inhibited. In this regard, the Vα2Vβ10 TCR induced a strong degree of tyrosine phosphorylation but relatively little IL-2 secretion. This is somewhat surprising with regard to previously published data where a strong correlation between the degree of tyrosine phosphorylation and the extent of the functional responses was observed (26, 27, 58, 59). Whether this indicates that the Vα2Vβ10 receptor is intrinsically incapable of responding to a negative signal is difficult to know. A reciprocal study using antagonists for the Vα2Vβ10 TCR and agonist ligands for the Vα2Vβ5 receptor would have been informative, but antagonists for SSIEFARL (ligand for the Vα2Vβ10 receptor) have not been identified. It is also possible that antagonist peptides deliver negative signals which only inhibit other identical TCRs. If these putative negative signals are cis-limited, then we would not have been able to detect them using a second, independent receptor.

It is also theoretically possible that antagonist ligands generate dysfunctional TCRs, e.g., by inducing a conformation that disables the receptor from further activation. However, preexposure to antagonist peptides for 4 h alone did not render the Vα2Vβ5 expressing hybridomas cells unresponsive to further antigenic stimulation (data not shown), which is in accord with the findings of Preckel et al. for CD8+ T cell clones (19). Moreover, since the signaling capacity of a second independent TCR was unaffected, it is also unlikely that antagonist peptides alter T cell responses by consuming limited amounts of signaling intermediates.

There are two reports of antagonists that can inhibit T cell responses when present at substoichiometric ratios relative to the antigenic peptide (10, 11). These types of antagonist peptides may not function by competition and conceivably could deliver a negative signal to the responding T cell. Thus, there may be different classes of antagonist peptides that act through different mechanisms. One class that was studied here must be present in molar excess to exert an inhibitory effect and uses a competitive mechanism to inhibit T cell responses. Other classes of TCR antagonists, which are effective at substoichiometric ratios, may work by a dominant-negative mechanism.

Our data also show that neither the extent of inhibition (Fig. 1 B) nor the kinetics (Fig. 7) of TCR internalization fully accounted for the inhibition of IL-2 response in our experimental system. In fact, these data demonstrate that antagonist peptides can fully exert their inhibitory effect well after the initial phase of TCR downregulation, at a stage where there is no further net loss of surface TCRs (Fig. 8). Furthermore, the blocking studies with the anti-Kb antibody, Y3, demonstrated that the time window of susceptibility to antagonism correlated exactly with the time of commitment.

Previous studies have already pointed out the importance of a sustained signal for T cell commitment (60–62). Depending upon the amount of available antigen, the type of APC, the number of adhesion and costimulatory molecules present on the APC, and the state of differentiation of the responding cell, the length of time required for T cell commitment varied (63). For the Vα2Vβ5 expressing T cell hybridoma, 12 h of continuous engagement with the agonist ligand was required for a commitment to IL-2 secretion. On the other hand, internalization of TCRs reached a steady-state after 2–3 h of antigen exposure (Fig. 7). After this point there may be continued TCR downregulation, but there is no further net loss of TCR from the cell surface. These data suggest that antagonist peptides competitively inhibit agonist ligands from productively engaging TCR during the entire commitment period. Therefore, it is conceivable that small changes in the rate of TCR engagement, integrated over time, may have a significant impact on the final outcome of T cell activation.

Nevertheless, antagonist as well as partial agonist ligands induce biochemical signals, which are different from the signaling events generated by antigenic ligand used over a broad range of concentrations (28). Altered peptide ligands have been shown to induce altered phosphorylation of the ζ chain without stable phosphorylation of CD3ε and ZAP-70 (26–28). That partial agonists induce differential biochemical signaling events as well as a long lived anergy in CD4+ T cell clones (20, 26, 64) has led some investigators to postulate that altered peptide ligands generate qualitatively different signals (26). In principle, the anergic state could result from the consumption of limiting signaling intermediates or from an imbalanced expression of transcription factors (65). Since T cell hybridomas, which are not IL-2 dependent for their proliferation, were used in these studies, we could not directly address this issue. Nevertheless, our experiments suggest that the inhibition of IL-2 production, a feature which characterizes most anergic T cells, is not mediated by a negative signal.

In summary, the data are consistent with the idea that the antagonist ligands studied here do not deliver negative signals, but rather compete with antigenic ligands for TCR engagement. This competition can effectively inhibit T cell responses by reducing the rate of TCR engagement throughout the entire commitment period.

Acknowledgments

We thank Claerwen Jones for providing the Vβ10 cDNA, P. Cosson for the cDNAs encoding CD8α and CD8β, I. Luescher for the APC line, and J. Bluestone for the anti-Kb mAb, Y3. We are grateful to A. Pickert and M. Dessing for cell sorting and B. Pfeiffer for photography. We also thank J. Bluestone for valuable discussion, and M. Bachmann, J. Bluestone, H. Jacobs, and T. Goebel for reviewing the manuscript.

Abbreviation used in this paper

- HRPO

horseradish peroxidase

Footnotes

The Basel Institute for Immunology was founded and is supported by F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland.

References

- 1.Garcia KC, Degano M, Stanfield RL, Brunmark A, Jackson MR, Peterson PA, Teyton L, Wilson IA. An αβ T cell receptor structure at 2.5 Å and its orientation in the TCR–MHC complex. Science. 1996;274:209–219. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5285.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garboczi DN, Ghosh P, Utz U, Fan QR, Biddison WE, Wiley DC. Structure of the complex between human T-cell receptor, viral peptide and HLA-A2. Nature. 1996;384:134–141. doi: 10.1038/384134a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perlmutter RM, Levin SD, Appleby MW, Anderson SJ, Alberola-Ila J. Regulation of lymphocyte function by protein phosphorylation. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:451–499. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan AC, Desai DM, Weiss A. The role of protein tyrosine kinases and protein tyrosine phosphatases in T cell antigen receptor signal transduction. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:555–592. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wange RL, Samelson LE. Complex complexes: signaling at the TCR. Immunity. 1996;5:197–205. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80315-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cantrell D. T cell antigen receptor signal transduction pathways. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:259–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De-Magistris MT, Alexander J, Coggeshall M, Altman A, Gaeta FC, Grey HM, Sette A. Antigen analog-major histocompatibility complexes act as antagonists of the T cell receptor. Cell. 1992;68:625–634. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90139-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Racioppi L, Ronchese F, Matis LA, Germain RN. Peptide–major histocompatibility complex class II complexes with mixed agonist/antagonist properties provide evidence for ligand-related differences in T cell receptor–dependent intracellular signaling. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1047–1060. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jameson SC, Carbone FR, Bevan MJ. Clone-specific T cell receptor antagonists of major histocompatibility complex class I–restricted cytotoxic T cells. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1541–1550. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klenerman P, Rowland-Jones S, McAdam S, Edwards J, Daenke S, Lalloo D, Koppe B, Rosenberg W, Boyd D, Edwards A, et al. Cytotoxic T-cell activity antagonized by naturally occurring HIV-1 Gag variants. Nature. 1994;369:403–407. doi: 10.1038/369403a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertoletti A, Sette A, Chisari FV, Penna A, Levrero M, De-Carli M, Fiaccadori F, Ferrari C. Natural variants of cytotoxic epitopes are T-cell receptor antagonists for antiviral cytotoxic T cells. Nature. 1994;369:407–410. doi: 10.1038/369407a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sette A, Alexander J, Ruppert J, Snoke K, Franco A, Ishioka G, Grey HM. Antigen analogs/MHC complexes as specific T cell receptor antagonists. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:413–431. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.002213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jameson SC, Bevan MJ. T cell receptor antagonists and partial agonists. Immunity. 1995;2:1–11. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janeway CA., Jr Ligands for the T-cell receptor: hard times for avidity models. Immunol Today. 1995;16:223–225. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80163-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kersh GJ, Allen PM. Review: essential flexibility in the T-cell recognition of antigen. Nature. 1996;380:495–498. doi: 10.1038/380495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madrenas J, Germain RN. Variant TCR ligands: new insights into the molecular basis of antigen- dependent signal transduction and T-cell activation. Semin Immunol. 1996;8:83–101. doi: 10.1006/smim.1996.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruppert J, Alexander J, Snoke K, Coggeshall M, Herbert E, McKenzie D, Grey HM, Sette A. Effect of T-cell receptor antagonism on interaction between T cells and antigen-presenting cells and on T-cell signaling events. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2671–2675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKeithan TW. Kinetic proofreading in T-cell receptor signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5042–5046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Preckel T, Grimm R, Martin S, Weltzien H. Altered hapten ligands antagonize trinitrophenyl-specific cytotoxic T cells and block internalization of hapten-specific receptors. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1803–1813. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.10.1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sloan-Lancaster J, Evavold BD, Allen PM. Induction of T-cell anergy by altered T-cell–receptor ligand on live antigen-presenting cells. Nature. 1993;363:156–159. doi: 10.1038/363156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sloan-Lancaster J, Steinberg TH, Allen PM. Selective activation of the calcium signaling pathway by altered peptide ligands. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1525–1530. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bachmann MF, Mariathasan S, Bouchard D, Speiser DE, Ohashi PS. Four types of Ca2+ signals in naive CD8+cytotoxic T cells after stimulation with T cell agonists, partial agonists and antagonists. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:3414–3419. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsui K, Boniface JJ, Steffner P, Reay PA, Davis MM. Kinetics of T-cell receptor binding to peptide/ I-Ek complexes: correlation of the dissociation rate with T-cell responsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12862–12866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alam S, Travers P, Wung J, Nasholds W, Redpath S, Jameson S, Gascoigne N. T-cell–receptor affinity and thymocyte positive selection. Nature. 1996;381:616–620. doi: 10.1038/381616a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyons D, Lieberman S, Hampl J, Boniface J, Chien Y, Berg L, Davis M. A TCR binds to antagonist ligands with lower affinities and faster dissociation rates than to agonists. Immunity. 1996;5:53–61. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sloan-Lancaster J, Shaw AS, Rothbard JB, Allen PM. Partial T cell signaling: altered phospho-zeta and lack of zap70 recruitment in APL-induced T cell anergy. Cell. 1994;79:913–922. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madrenas J, Wange RL, Wang JL, Isakov N, Samelson LE, Germain RN. Zeta phosphorylation without ZAP-70 activation induced by TCR antagonists or partial agonists. Science. 1995;267:515–518. doi: 10.1126/science.7824949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reis e Sousa CR, Levine E, Germain R. Partial signaling by CD8+T cells in response to antagonist ligands. J Exp Med. 1996;184:149–157. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rabinowitz JD, Beeson C, Lyons DS, Davis MM, McConnell HM. Kinetic discrimination in T-cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1401–1405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Racioppi L, Matarese G, D'Oro U, De Pascale M, Masci AM, Fontana S, Zappacosta S. The role of CD4-Lck in T-cell receptor antagonism: evidence for negative signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10360–10365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoon S, Dianzani U, Bottomly K, Janeway CJ. Both high and low avidity antibodies to the T cell receptor can have agonist or antagonist activity. Immunity. 1994;1:563–569. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hogquist KA, Jameson SC, Heath WR, Howard JL, Bevan MJ, Carbone FR. T cell receptor antagonist peptides induce positive selection. Cell. 1994;76:17–27. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jameson SC, Hogquist KA, Bevan MJ. Specificity and flexibility in thymic selection. Nature. 1994;369:750–752. doi: 10.1038/369750a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hogquist KA, Jameson SC, Bevan MJ. Strong agonist ligands for the T cell receptor do not mediate positive selection of functional CD8+T cells. Immunity. 1995;3:79–86. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelly J, Sterry S, Cose S, Turner S, Fecondo J, Rodda S, Fink P, Carbone F. Identification of conserved T cell receptor CDR3 residues contacting known exposed peptide side chains from a major histocompatibility complex class I-bound determinant. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:3318–3326. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830231239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller AD, Rosman GJ. Improved retroviral vectors for gene transfer and expression. Biotechniques. 1989;7:980–990. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgenstern JP, Land H. Advanced mammalian gene transfer: high titre retroviral vectors with multiple drug selection markers and a complementary helper-free packaging cell line. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3587–3596. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.12.3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mullen CA, Kilstrup M, Blaese RM. Transfer of the bacterial gene for cytosine deaminase to mammalian cells confers lethal sensitivity to 5-fluorocytosine: a negative selection system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:33–37. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bäckström BT, Milia E, Peter A, Jaureguiberry B, Baldari CT, Palmer E. A motif within the T cell receptor alpha chain constant region connecting peptide domain controls antigen responsiveness. Immunity. 1996;5:437–447. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80500-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turner SJ, Cose SC, Carbone FR. TCR alpha-chain usage can determine antigen-selected TCR beta-chain repertoire diversity. J Immunol. 1996;157:4979–4985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Letourneur F, Malissen B. Derivation of a T cell hybridoma variant deprived of functional T cell receptor alpha and beta chain transcripts reveals a nonfunctional alpha-mRNA of BW5147 origin. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:2269–2274. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830191214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wallny HJ, Rotzschke O, Falk K, Hammerling G, Rammensee HG. Gene transfer experiments imply instructive role of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules in cellular peptide processing. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:655–659. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watson J. Continuous proliferation of murine antigen-specific helper T lymphocytes in culture. J Exp Med. 1979;150:1510–1519. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.6.1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bill J, Kanagawa O, Linten J, Utsunomiya Y, Palmer E. Class I and class II MHC gene products differentially affect the fate of V beta 5 bearing thymocytes. J Mol Cell Immunol. 1990;4:269–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leo O, Foo M, Sachs DH, Samelson LE, Bluestone JA. Identification of a monoclonal antibody specific for a murine T3 polypeptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1374–1378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rozdzial MM, Kubo RT, Turner SL, Finkel TH. Developmental regulation of the TCR zeta-chain. Differential expression and tyrosine phosphorylation of the TCR zeta-chain in resting immature and mature T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1994;153:1563–1580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pircher H, Rebai N, Groettrup M, Gregoire C, Speiser DE, Happ MP, Palmer E, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H, Malissen B. Preferential positive selection of V alpha 2+ CD8+T cells in mouse strains expressing both H-2k and T cell receptor V alpha a haplotypes: determination with a V alpha 2–specific monoclonal antibody. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:399–404. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Necker A, Rebai N, Matthes M, Jouvin-Marche E, Cazenave PA, Swarnworawong P, Palmer E, MacDonald HR, Malissen B. Monoclonal antibodies raised against engineered soluble mouse T cell receptors and specific for V alpha 8–, V beta 2– or V beta 10–bearing T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:3035–3040. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830211220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Loken MR, Stall AM. Flow cytometry as an analytical and preparative tool in immunology. J Immunol Methods. 1982;50:R85–R112. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(82)90161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones B, Janeway CA., Jr Cooperative interaction of B lymphocytes with antigen-specific helper T lymphocytes is MHC restricted. Nature. 1981;292:547–549. doi: 10.1038/292547a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bolliger L, Johansson B, Palmer E. The short extracellular domain of the T cell receptor zeta chain is involved in assembly and signal transduction. Mol Immunol. 1997;34:819–827. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(97)00122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Renard V, Romero P, Vivier E, Malissen B, Luescher IF. CD8 beta increases CD8 coreceptor function and participation in TCR-ligand binding. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2439–2444. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Valitutti S, Muller S, Cella M, Padovan E, Lanzavecchia A. Serial triggering of many T-cell receptors by a few peptide–MHC complexes. Nature. 1995;375:148–151. doi: 10.1038/375148a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Viola A, Linkert S, Lanzavecchia A. A T cell receptor (TCR) antagonist competitively inhibits serial TCR triggering by low-affinity ligands, but does not affect triggering by high-affinity anti-CD3 antibodies. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:3080–3083. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bachmann MF, Salzmann M, Oxenius A, Ohashi PS. Formation of T cell receptor dimers/trimers as a crucial step for T cell activation. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2571–2579. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199808)28:08<2571::AID-IMMU2571>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jacobs H. Pre-TCR/CD3 and TCR/CD3 complexes: decamers with differential signalling properties? . Immunol Today. 1997;18:565–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Monks CR, Freiberg BA, Kupfer H, Sciaky N, Kupfer A. Three-dimensional segregation of supramolecular activation clusters in T cells. Nature. 1998;395:82–86. doi: 10.1038/25764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.La Face DM, Couture C, Anderson K, Shih G, Alexander J, Sette A, Mustelin T, Altman A, Grey HM. Differential T cell signaling induced by antagonist peptide–MHC complexes and the associated phenotypic responses. J Immunol. 1997;158:2057–2064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hemmer B, Stefanova I, Vergelli M, Germain RN, Maring R. Relationships among TCR ligand potency, thresholds for effector function elicitation, and the quality of early signaling events in human T cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:5807–5814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cantrell DA, Smith KA. The interleukin-2 T-cell system: a new cell growth model. Science. 1984;224:1312–1316. doi: 10.1126/science.6427923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weiss A, Shields R, Newton M, Manger B, Imboden J. Ligand-receptor interactions required for commitment to the activation of the interleukin 2 gene. J Immunol. 1987;138:2169–2176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Crabtree GR. Contingent genetic regulatory events in T lymphocyte activation. Science. 1989;243:355–361. doi: 10.1126/science.2783497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Iezzi G K.Karjalainen, and A. Lanzavecchia. The duration of antigenic stimulation determines the fate of naive and effector T cells. Immunity. 1998;8:89–95. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80461-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ryan KR, Evavold BD. Persistence of peptide-induced CD4+T cell anergy in vitro. J Exp Med. 1998;187:89–96. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith JA, Bluestone JA. T cell inactivation and cytokine deviation promoted by anti-CD3 mAbs. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:648–654. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]