Abstract

Previous studies have shown that induction of autoimmune diabetes by adult thymectomy and split dose irradiation of PVG.RT1u rats can be prevented by their reconstitution with peripheral CD4+CD45RC−TCR-α/β+RT6+ cells and CD4+CD8− thymocytes from normal syngeneic donors. These data provide evidence for the role of regulatory T cells in the prevention of a tissue-specific autoimmune disease but the mode of action of these cells has not been reported previously. In this study, autoimmune thyroiditis was induced in PVG.RT1c rats using a similar protocol of thymectomy and irradiation. Although a cell-mediated mechanism has been implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetes in PVG.RT1u rats, development of thyroiditis is independent of CD8+ T cells and is characterized by high titers of immunoglobulin (Ig)G1 antithyroglobulin antibodies, indicating a major humoral component in the pathogenesis of disease. As with autoimmune diabetes in PVG.RT1u rats, development of thyroiditis was prevented by the transfer of CD4+CD45RC− and CD4+CD8− thymocytes from normal donors but not by CD4+CD45RC+ peripheral T cells. We now show that transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and interleukin (IL)-4 both play essential roles in the mechanism of this protection since administration of monoclonal antibodies that block the biological activity of either of these cytokines abrogates the protective effect of the donor cells in the recipient rats. The prevention of both diabetes and thyroiditis by CD4+CD45RC− peripheral cells and CD4+CD8− thymocytes therefore does not support the view that the mechanism of regulation involves a switch from a T helper cell type 1 (Th1) to a Th2-like response, but rather relies upon a specific suppression of the autoimmune responses involving TGF-β and IL-4. The observation that the same two cytokines were implicated in the protective mechanism, whether thymocytes or peripheral cells were used to prevent autoimmunity, strongly suggests that the regulatory cells from both sources act in the same way and that the thymocytes are programmed in the periphery for their protective role. The implications of this result with respect to immunological homeostasis are discussed.

Keywords: autoimmunity, regulatory T cells, transforming growth factor β, interleukin 4

Rats and mice that are relatively T cell deficient for genetic reasons, or that are made so experimentally, develop a range of tissue-specific autoimmune diseases that can be prevented by the transfer of the appropriate T cell subset from syngeneic, nonlymphopenic donors. These observations demonstrate that self-tolerance is an active process and is not achieved entirely by a combination of deletion of autoreactive T cells intrathymically and of clonal anergy, deletion, or indifference in the periphery (1–5). Studies in this laboratory have shown that insulin- dependent diabetes is induced in a normal strain of laboratory rat by thymectomy at 6 wk of age followed by four equal doses of 250-rad 137Cs γ-irradiation at 2-wk intervals. Rats develop disease over the ensuing 10–12 wk, characterized by infiltration of pancreatic islets and selective destruction of the β cells in virtually all males and 70% of females. Disease is prevented in ∼50% of rats reconstituted shortly after the last irradiation with peripheral CD4+ cells from syngeneic donors. Phenotypic analysis of these cells identified a subset of cells that protected 100% of recipients from diabetes as being CD4+CD45RC−TCR-α/β+RT6+ (6). Some of the cells with this phenotype have been shown to produce IL-4 on activation in vitro (7) and provide B cells with help for secondary antibody responses (8), raising the possibility that the prevention of diabetes involved a switch from a proinflammatory, cell-mediated, Th1 response to a nonpathogenic humoral one. The peripheral T cells that prevented diabetes in these experiments have a memory phenotype, suggesting that they are primed in the periphery to some undefined antigen. However, when CD4+CD8− thymocytes were assayed for their ability to prevent diabetes in this system, it was found that these were much more potent in regulating the disease than were the peripheral memory cells (9). This unexpected finding raised questions about the mechanisms of disease prevention by the cells from the two sources and the developmental relationship between them. To examine these questions, we have studied another lymphopenia-induced autoimmune disease, which unlike the autoimmune diabetes has a strong humoral component.

In studies that originally described the development of autoimmunity in normal rats after thymectomy and irradiation (TxX protocol), autoimmune thyroiditis, characterized by leukocytic infiltration of thyroid glands and the development of high titers of antithyroglobulin (Tg)1 antibodies, was induced in PVG.RT1c strain rats (10, 11). In these same studies it was shown that reconstitution of these lymphopenic rats with splenocytes from normal syngeneic recipients could prevent disease development. However, the phenotype and function of the regulatory T cells that prevent it has not been determined previously. In this study we show that, although thyroiditis in such rats is characterized by a humoral, anti-Tg response, it is the CD4+ CD45RC− subset that is responsible for protection from disease. As noted above, this same subset prevents the cell-mediated diabetes observed in TxX PVG.RT1u rats (6). Further similarities in the mechanisms that prevent the two diseases are shown by the observation that, as with the prevention of diabetes, CD4+CD8− thymocytes are also very potent at preventing autoimmune thyroiditis. Finally, we show that the cytokines IL-4 and TGF-β both play an essential role in the mechanism of protection by both peripheral CD4+CD45RC− T cells and CD4+CD8− thymocytes, strongly suggesting that the same cellular mechanism is involved.

Materials and Methods

Monoclonal Antibodies.

The mouse mAbs used in these studies were as follows: W3/25 (anti–rat CD4; reference 12); OX6 (anti–rat class II MHC; reference 13); OX8 (anti–rat CD8; reference 14); OX12 (anti–rat κ chain; reference 15); OX21 (anti– human C3b inactivator, IgG1; reference 16); OX22 (anti–rat exon C of CD45; references 8, 17); OX32 (anti–rat exon C of CD45, non-competing with OX22; references 17, 18); OX81 (anti–rat IL-4, IgG1; reference 19), 2G.7 (anti–human TGF-β, IgG2a; reference 20); and W6/32 (anti–human class I, IgG2a; reference 21).

Animals and Induction of Thyroiditis.

3–12-wk-old female PVG.RT1c (PVG) rats were obtained from the specific pathogen–free breeding facilities of the Medical Research Council Cellular Immunology Unit (Oxford, UK). Thyroiditis was induced in female PVG rats as has been previously described (11). In brief, 3-wk-old female rats were thymectomized and given four 275-rad doses of 137Cs γ-irradiation at 2-wk intervals starting 1 wk after thymectomy (TxX). Development of thyroiditis was determined histologically and by the development of anti-Tg antibodies. Since the incidence of thyroiditis is higher in females (∼70%) than males (∼50%), female rats were used exclusively for thyroiditis induction.

Isolation of T Cell Subpopulations.

Rat thoracic duct lymphocytes (TDLs) were obtained by cannulation of the duct (22). Cells were collected at 4°C overnight into flasks containing PBS and 20 U/ml heparin. Rat lymphocyte populations were negatively selected from TDLs using a rosetting technique as described elsewhere (23) or using magnetic beads (Dynal). CD4+ T cells were isolated by depletion of B cells and CD8+ T cells using the mAbs OX12, OX8, and OX6. To obtain CD4+CD45RC− T cells, TDLs were depleted using the mAbs OX22, OX32, and OX8. CD4+CD8− thymocytes were purified from thymus of 6-wk-old PVG rats by depletion of CD8+ cells. The purity of all isolated cells was analyzed on a FACScan® (Becton Dickinson) by labeling pre- and postdepletion samples with rabbit anti–mouse FITC. The percentage of contaminated cells was <2%.

CD4+CD45RChigh cells were isolated by positive selection using MACS microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). CD4+ T cells, purified from TDLs by rosette depletion, were labeled with a limiting concentration of OX32 tissue culture supernatant such that only cells expressing the highest levels of CD45RC were labeled by mAb. OX32-labeled cells were in turn labeled with goat anti– mouse Ig microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) and run down a positive selection column. The purity of eluted CD45RChigh cells, as determined by labeling a sample with saturating levels of OX22 mAb and RAM-FITC, was >99.5%.

Detection and Quantitation of Anti-Tg Antibodies in Sera of Rats.

Sera from TxX rats were assayed every 2 wk for anti-Tg antibodies between 4 and 12 wk after the last irradiation by specific ELISA. 96-well microtiter plates were coated overnight with purified rat Tg (20 μg/ml) and blocked for 30 min with 1% BSA in PBS. Sera of individual rats at four fivefold dilutions starting at 1:10 were incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Rat IgG was detected using anti–rat IgG alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Sigma Chemical Co.) for 1 h at room temperature, and different rat Ig isotypes were detected using biotinylated mAbs (1 μg/ml) specific for IgG1 (PharMingen), IgG2a (Serotec Ltd.), and IgG2b (PharMingen) for 1 h at room temperature followed by a 1 h incubation with avidin alkaline phosphatase (Sigma Chemical Co.). Plates were washed three times between each step with 0.05% Tween 20/PBS. The assay was developed using enzyme substrate 4-nitro-phenyl phosphate (5 mg/ml; Sigma Chemical Co.) for 15 min at room temperature before reading the OD at 405 nm. Anti-Tg antibody titers were quantified by comparison with a standard serum pooled from TxX rats with thyroiditis and high anti-Tg antibody titers and expressed as a percentage of this standard. The level of nonspecific binding found in normal PVG serum represented a titer of ∼0.1% in the assay, and therefore only sera with titers >0.3% were considered to contain specific anti-Tg antibodies.

Histological Analysis.

Whole thyroids attached to cricoid cartilage were dissected out and fresh frozen in O.C.T. embedding medium (Sakura Finetek U.S.A. Inc.). 10-μm sections were cut from frozen blocks and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Statistical Analysis.

Incidence of thyroiditis development in two different groups of TxX PVG rats was compared for statistically significant differences using Fisher's exact test for consistency in a 2 × 2 table.

Results

Development of Thyroiditis in TxX Rats Is Associated with a Humoral Th2 Autoimmune Response.

Previous studies have shown that normal rats with no tendency to spontaneously develop autoimmunity will develop organ-specific autoimmunity in a strain-dependent fashion if thymectomized and given four equal doses of γ-irradiation at 2-wk intervals. After thymectomy and irradiation, female PVG rats spontaneously develop autoimmune thyroiditis characterized by extensive infiltration of thyroid glands and development of high titers of anti-Tg antibodies (10, 11). In contrast, similar treatment of PVG.RT1u strain rats, differing from PVG rats only in their MHC haplotype, results in the development of a fatal insulin-dependent diabetes 4–10 wk after the last irradiation at a high incidence in males (6). Studies of the pathogenesis of diabetes in both TxX PVG.RT1u rats and the nonobese diabetic (NOD) mouse strongly implicate a Th1 cell–mediated mechanism, since CD8+ T cells are required for disease development (6, 24) and manipulations that antagonize development of Th1 responses protect NOD mice from disease development (25–27).

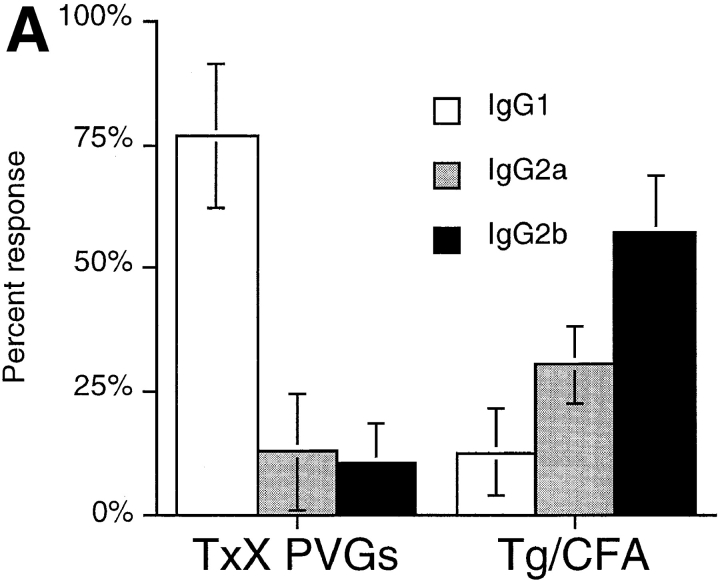

To further characterize the pathogenesis of thyroiditis development in TxX PVG rats, the use of different IgG isotypes in the anti-Tg antibody response was analyzed. In the rat, antibodies of the IgG1 isotype, like those in the mouse, are associated with a Th2 response, whereas IgG2b isotype synthesis, in contrast to that in mice, is indicative of a Th1 response. The IgG2a isotype is not preferentially favored by either Th1 or Th2 reactions (28, 29). Although no anti-Tg IgG of any isotype was detectable in the sera of normal rats (data not shown), sera of TxX rats with thyroiditis consistently contained high titers of anti-Tg IgG of the IgG1 isotype, with little specific IgG2a or IgG2b antibodies (Fig. 1 A). This profile of anti-Tg IgG isotype usage contrasted significantly with that of normal PVG rats immunized with Tg in CFA, an adjuvant known to induce Th1 responses. Normal 12-wk-old PVG rats immunized with Tg (50 μg/rat) in CFA developed anti-Tg IgG of the IgG2b isotype, with little anti-Tg IgG1 (Fig. 1 A).

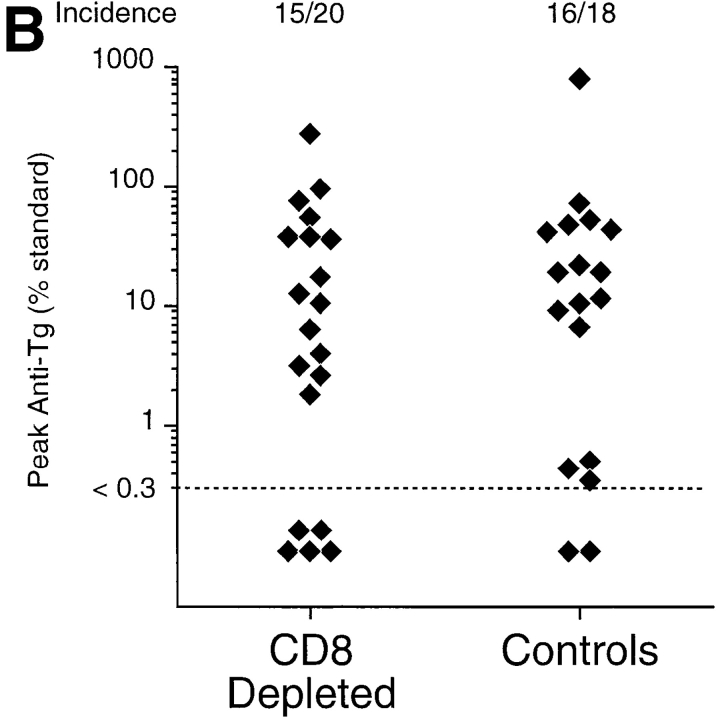

Figure 1.

Thyroiditis in PVG rats after their thymectomy and irradiation develops independently of CD8+ cells and is characterized by a Th2-like anti-Tg IgG response. Female PVG rats were thymectomized at 3 wk of age followed 1 wk later, by four doses of 275 rad 137Cs γ-irradiation at 2-wk intervals. (A) The isotype of anti-Tg IgG antibodies in sera of TxX rats with thyroiditis (n = 25) and normal 12-wk-old female PVG rats immunized with Tg (50 μg/rat) in CFA (n = 5) was determined by specific ELISA. Data are expressed as the mean percentage of the anti-Tg response for each IgG isotype where 100% is the sum of the ODs for individual isotypes above background of normal PVG sera in 1:10 dilutions of an experimental serum. Error bars indicate SD. (B) The requirement for CD8+ cells in the development of thyroiditis in TxX PVG rats was determined by their injection at the time of thymectomy and 7 d later with either the anti-CD8-depleting mAb OX8 (0.5 mg/injection) or PBS as control. Development of anti-Tg IgG responses was monitored between 4 and 12 wk after the last irradiation by specific ELISA. Data represent peak anti-Tg IgG titers expressed as percentage of standard for individual TxX rats. FACS® analysis of splenocytes from OX8-treated rats, 12 wk after the last irradiation, showed that <2% of TCR+ cells were CD8+ (data not shown). Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Because the isotype of anti-Tg IgG antibodies in TxX rats indicated that the pathogenesis involved the activity of Th2 cells, the requirement for CD8+ T cells in the development of thyroiditis was tested. PVG rats were depleted of CD8+ cells by injection, at the time of thymectomy and 1 wk after thymectomy, with purified depleting anti-CD8 mAb OX8 in PBS (0.5 mg/injection). Control rats received injections of PBS alone. Although treated rats were still depleted of TCR+ CD8+ cells 12 wk after their last irradiation (data not shown), they developed thyroiditis at a similar frequency to control rats (Fig. 1 B) (P > 0.24). In principle, it is possible that residual CD8+ cells, whose presence was not readily detectable by FACS® analysis, mediated disease development. However, it is notable that similar depletion of CD8+ cells in PVG.RT1u rats was sufficient to completely prevent diabetes, suggesting that the depletion regime was effective (6).

Reconstitution of TxX PVG Rats with Syngeneic CD4+ CD45RC− Cells Completely Prevents Thyroiditis.

In previous studies of autoimmunity in TxX rats, development of diabetes could be prevented in ∼50% of PVG.RT1u rats by their reconstitution with unfractionated CD4+ T cells from normal syngeneic donors (6). Similarly, thyroiditis development was prevented in TxX PVG rats by their reconstitution with unfractionated splenocytes (30). In the former case, protection from diabetes development was shown to be mediated by the CD4+CD45RC− subset of CD4+ T cells and antagonized by the CD4+CD45RC+ subset. This antagonism explained why unfractionated CD4+ T cells protected only some recipients while, in contrast, all prediabetic rats given the CD4+CD45RC− subset were free of disease. Cells that share this protective CD4+CD45RC− phenotype provide B cells with help for secondary antibody responses (28) and produce IL-4 after activation in vitro (7) and therefore have some of the characteristics of Th2 cells. In principle then, protection from diabetes could have reflected a switch from a cell-mediated to a humoral response toward islet cell autoantigens. In contrast to the cell-mediated mechanisms implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetes, the IgG isotypes of anti-Tg responses in rats with thyroiditis indicate the activity of Th2 cells and this observation calls into question the possible involvement of a Th1 to Th2 switch in preventing these autoimmune diseases. However, the preceding data did not exclude the possibility that different subsets of CD4+ T cells were involved in the prevention of these two diseases. To examine this possibility, a comparison was made of the abilities of CD4+CD45RC− and CD4+CD45RC+ cells to prevent thyroiditis.

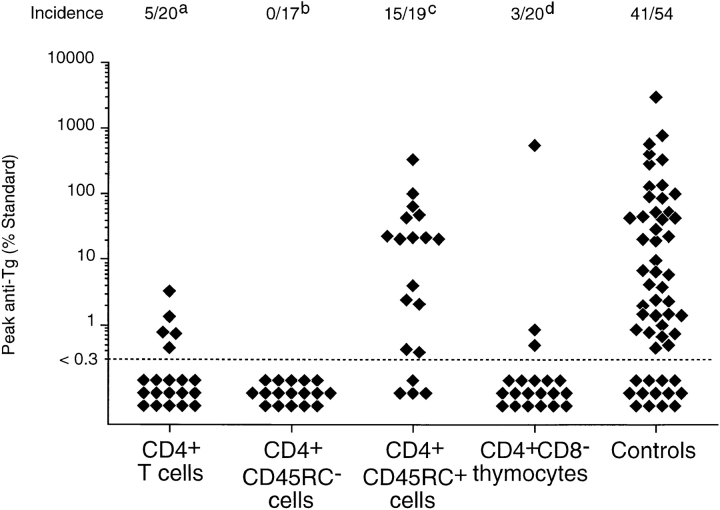

Consistent with previous studies (30), reconstitution of TxX PVG rats with 107 unfractionated CD4+ TDLs shortly after their last irradiation prevented development of thyroiditis in a high proportion of recipients (Fig. 2). Significantly, however, TxX PVG rats reconstituted with 107 CD4+CD45RC+ TDLs shortly after their final irradiation developed thyroiditis at the same frequency as control rats (Fig. 2). In contrast, TxX rats injected with 107 CD4+ CD45RC− TDLs shortly after their final irradiation were completely protected from development of both serological (Fig. 2) and histological (Fig. 3) signs of disease.

Figure 2.

Prevention of thyroiditis development in TxX PVG rats by their reconstitution with either CD4+CD45RC− T cells or CD4+CD8− thymocytes. Unfractionated CD4+ and CD4+CD45RC− cells were purified from TDLs of 12-wk-old normal PVG rats by Dynal bead depletion. CD4+CD45RC+ cells were purified from CD4+ TDLs by positive selection using MACS beads, whereas CD4+CD8− thymocytes were purified from thymus of 6-wk-old rats by depletion of CD8+ cells as described in Materials and Methods. Shortly after their last irradiation, TxX PVG rats were reconstituted with 107 of unfractionated CD4+ cells, CD4+ CD45RC− cells, CD4+CD45RC+ cells, or CD4+CD8− thymocytes, while control rats received no cells. Data represent peak anti-Tg IgG antibody levels in individual TxX rats from groups reconstituted with different T cell subsets. Anti-Tg titers are expressed as percentage of a standard and data are the pool of six independent experiments. Statistics versus controls: a P < 10−4; b P < 1.2 × 10−8; c P > 0.52; d P < 3 × 10−6.

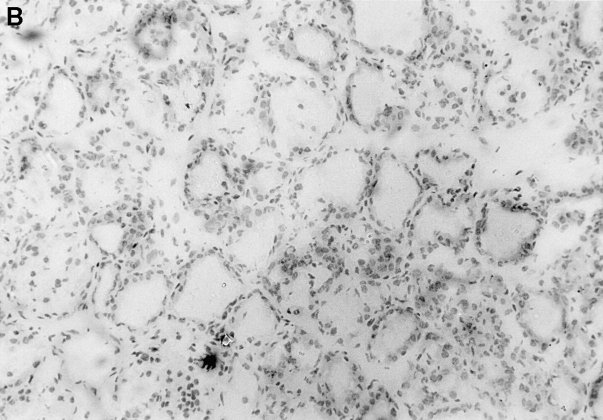

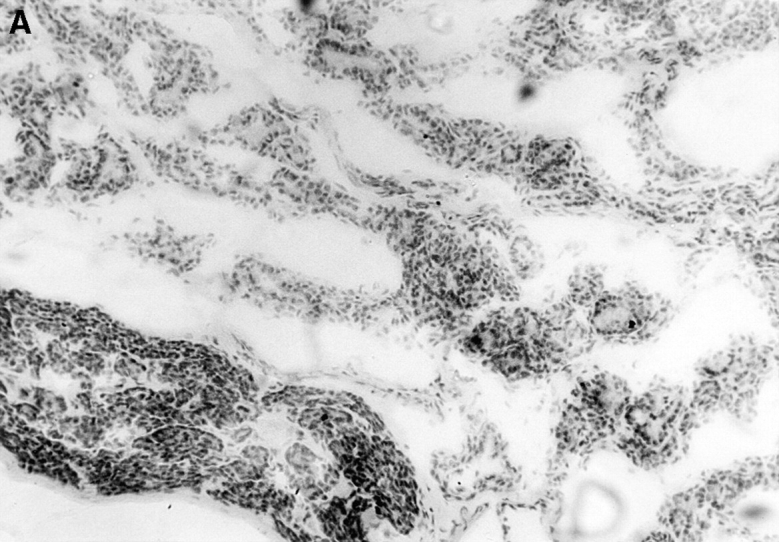

Figure 3.

Immunopathology of the thyroid glands from control TxX rats and those reconstituted with CD4+CD45RC− T cells. In experiments similar to those described in Fig. 2, thyroid glands were taken at the time of peak disease, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Thyroids from control TxX PVG rats (A; original magnification ×200) show extensive mononuclear cell infiltrate and loss of follicular structure. In contrast, thyroid glands from TxX PVG rats reconstituted with 107 CD4+CD45RC− cells shortly after their last irradiation are of normal morphology with no signs of infiltration (B; original magnification ×200). Similarly, thyroids of TxX PVG rats protected by their reconstitution with CD4+CD8− thymocytes were of normal morphology with no signs of infiltration (data not shown).

CD4+CD8− Thymocytes Are a Potent Source of Cells that Prevent Autoimmune Thyroiditis.

Previous studies in this laboratory showed that diabetes could be prevented in a large proportion of TxX PVG.RT1u rats after their reconstitution with CD4+CD8− thymocytes (6). Further experiments indicated that these thymocytes were effective at preventing diabetes at a significantly lower dose than required for peripheral CD4+CD45RC− T cells (9). To determine whether CD4+CD8− thymocytes were equally potent at preventing thyroiditis they were tested for their ability to control onset of this disease at different cell doses. PVG rats, thymectomized at 3 wk of age and given four doses of 275 rad γ-irradiation, were reconstituted shortly after their last irradiation either with purified CD4+CD8− thymocytes at doses of 107, 5 × 106, 106, 5 × 105, or 105 per rat, or with CD4+CD45RC− cells purified from TDLs of 12-wk-old normal donors at doses of 107, 5 × 106, or 106 per rat. In agreement with studies of diabetes in PVG.RT1u rats, most but not all rats reconstituted with 107 CD4+CD8− thymocytes were protected from development of thyroiditis (Fig. 2) and, significantly, these thymocytes were found to be highly potent in controlling the disease. An indistinguishable level of protection was observed in recipients of a range of CD4+CD8− thymocyte doses, between 5 × 105 and 107 cells/rat. Only at doses below 5 × 105 CD4+CD8− thymocytes was protection lost (Fig. 4). In contrast, although recipients of 107 CD4+ CD45RC− cells were protected from disease development, a low incidence of disease was observed in recipients of half that number of CD4+CD45RC− cells, and rats reconstituted with 106 CD4+CD45RC− cells were not protected at all (Fig. 4).

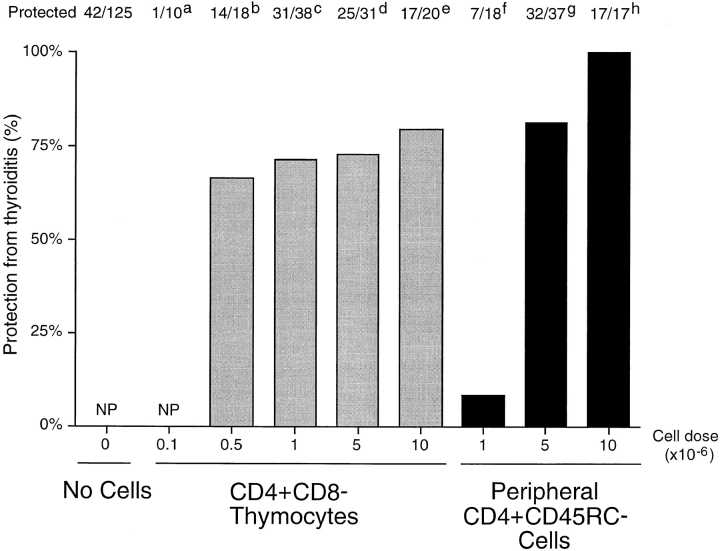

Figure 4.

CD4+CD8− thymocytes are more potent than CD4+ CD45RC− cells at preventing development of thyroiditis in TxX PVG rats. PVG rats were thymectomized at 3 wk of age and given four equal doses of 275-rad 137Cs γ-irradiation at 2-wk intervals starting 1 wk after thymectomy. CD4+CD8− thymocytes were purified from thymus of 6-wk-old PVG rats by depletion of CD8+ cells, and CD4+CD45RC− cells were purified from TDLs of 12-wk-old PVG rats by depletion of CD8+ and CD45RC+ cells. Shortly after their last irradiation, groups of rats were reconstituted either with CD4+CD8− thymocytes at doses of 105, 5 × 105, 106, 5 × 106, or 107 per rat, or with CD4+CD45RC− cells at doses of 106, 5 × 106, or 107 per rat. Development of anti-Tg antibodies was determined between 4 and 12 wk after the final irradiation by specific ELISA. Data are expressed as percentage of rats protected from development of disease, where the incidence of protection in the control group (42 out of 125 control rats failed to develop disease) is considered 0% protection. NP, no protection. Statistics versus controls: a P > 0.11; b P < 0.0046; c P < 1.6 × 10−7; d P < 2.3 × 10−6; e P < 1.8 × 10−5; f P > 0.4; g P < 8 × 10−9; h P < 7 × 10−8.

Prevention of Thyroiditis by Peripheral or Thymic CD4+ T Cells Is Abrogated by Blockade of either TGF-β or IL-4 Activity.

Results from this present and previous studies (6) have established that the regulatory subset of peripheral T cells that prevent autoimmunity in TxX rats are CD4+ CD45RC−RT6+TCR-α/β+, and furthermore, that CD4+ CD8− thymocytes are also a potent source of cells with a similar regulatory capacity. However, the mechanisms by which these different populations prevent autoimmunity and whether the regulatory cells in the thymus and those in the periphery represent the same lineage of cells has not been examined until now. By using mAbs that specifically block the biological activities of TGF-β and IL-4 it was possible to determine the role of these cytokines in the protection of rats from development of thyroiditis following their reconstitution with either CD4+CD45RC− cells or CD4+CD8− thymocytes. Groups of PVG rats, thymectomized neonatally and 1 wk later started on a regime of four 275-rad doses of 137Cs γ-irradiation at 2-wk intervals, were reconstituted shortly after their last irradiation with either 5 × 106 CD4+CD45RC− cells purified from TDLs of normal 12-wk-old PVG rats or with 106 CD4+CD8− thymocytes purified from thymus of normal 6-wk-old syngeneic donors. Control rats received no cells. Groups of rats reconstituted with cells were then treated with either OX81 (2 mg/injection) or 2G.7 (2 mg/injection) mAbs that specifically block the biological activities of rat IL-4 (19) and rat TGF-β (31) respectively, while other groups received isotype-matched negative control mAbs at the same dose. Rats were injected with mAb 1 d before and 1 d after reconstitution and then twice weekly thereafter for 4 wk. This length of treatment was chosen because previous studies had shown that rats are protected from disease development when reconstituted with lymphocytes up to 14 d after the last irradiation. Development of thyroiditis in rats reconstituted 4 wk after the last irradiation was unaffected by the injection of the regulatory T cells (30), suggesting that these cells have, at most, a 4-wk window after the final irradiation in which they can affect disease development.

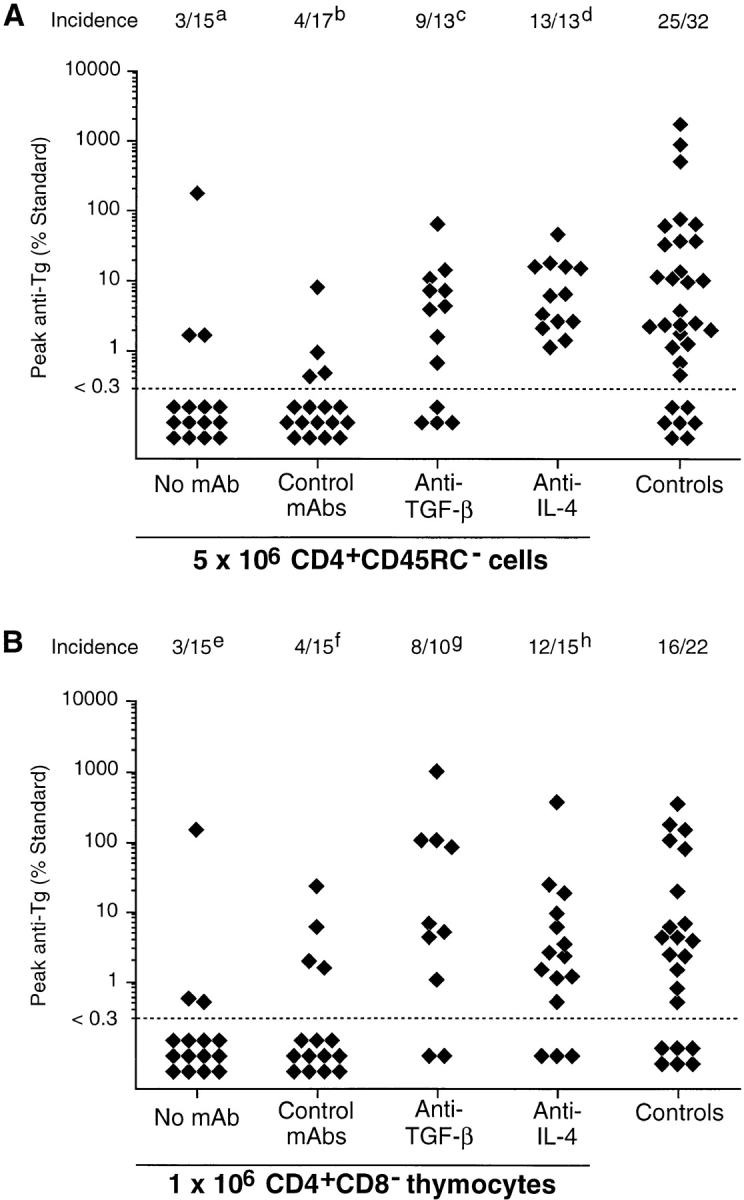

TxX rats reconstituted with a dose of 5 × 106 CD4+ CD45RC− cells and either untreated or treated with isotype-matched negative control mAbs were effectively protected from development of thyroiditis, with only 7 out of 32 rats developing any disease compared with 25 out of 32 controls rats (Fig. 5 A). However, treatment of TxX rats with mAbs specific for either TGF-β or IL-4 after their reconstitution with CD4+CD45RC− cells developed thyroiditis at a frequency comparable with that of control rats (Fig. 5 A). 9 out of 13 TxX rats reconstituted with CD4+CD45RC− cells and treated with anti–TGF-β mAb developed anti-Tg autoantibody responses, whereas all rats similarly reconstituted but treated with anti-IL-4 mAb made anti-Tg IgG. Significantly, although 7 out of 30 rats reconstituted with 106 CD4+CD8− thymocytes were protected from thyroiditis development (Fig. 5 B), rats similarly reconstituted but treated with anti–TGF-β or anti–IL-4 mAbs developed disease at a frequency similar to that of controls. Of those TxX rats reconstituted with 106 CD4+CD8− thymocytes, 8 out of 10 anti–TGF-β mAb-treated rats and 12 out of 15 anti–IL-4 mAb-treated rats developed thyroiditis (Fig. 5 B), compared with an incidence of 16 out of 22 control rats.

Figure 5.

Treatment of TxX rats with neutralizing mAbs against TGF-β or IL-4 abrogates protection from thyroiditis by both CD4+CD45RC− cells and CD4+CD8− thymocytes. Shortly after their last irradiation, groups of TxX PVG rats were injected with either 5 × 106 CD4+CD45RC− cells purified from TDLs of 12-wk-old normal PVG rats or 106 CD4+CD8− thymocytes purified from thymus of 6-wk-old normal PVG rats. Control rats received no cells. Rats reconstituted with cells were treated the day before and the day after cell transfer and then twice weekly for 4 wk with either the anti–TGF-β–neutralizing mAb 2G.7 (mouse IgG2a; 2 mg/injection) or the anti–IL-4–neutralizing mAb OX81 (mouse IgG1; 2 mg/injection). Control rats reconstituted with cells either received no further treatment or were injected with one of the isotype-control mAbs OX21 (mouse IgG1; 2 mg/injection) or W6/32 (mouse IgG2a; 2 mg/injection) specific for human determinants. Data represent peak anti-Tg antibody levels of individual TxX rats reconstituted with either CD4+CD45RC− cells (A) or CD4+CD8− thymocytes (B). Anti-Tg titers are expressed as percentage of standard and data are the pool of five independent experiments. Statistics versus controls: a P < 2.5 × 10−4; b P < 3.1 × 10−4; c P > 0.39; d P > 0.07; e P < 0.0021; f P < 0.008; g P > 0.51; h P > 0.46; versus reconstituted rats treated with control mAb (b and f): c P < 0.016; d P < 2 × 10−5; g P < 0.013; h P < 0.005.

Blockade of IL-4 and TGF-β in TxX Rats Reconstituted with CD4+CD45RC− Cells or CD4+CD8− Thymocytes Does Not Affect the anti-Tg IgG Response.

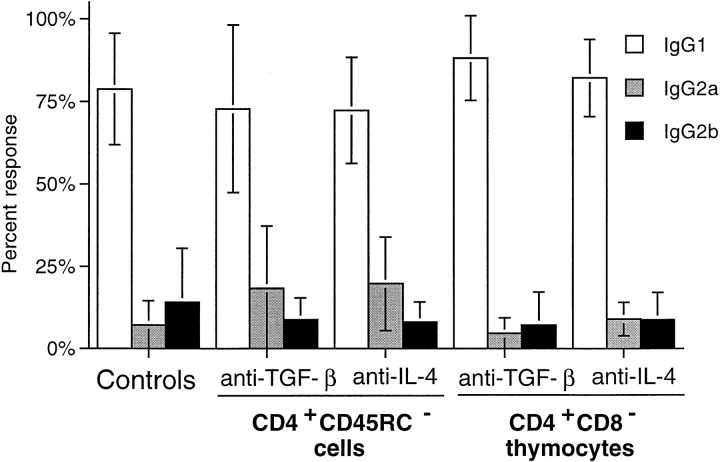

IL-4 has long been known to play a major role in developmental regulation of Th1 and Th2 immune responses, and in vivo blockade of its biological activity during immune responses is therefore likely to affect the balance of Th1/Th2 T cell development. Therefore, it was possible that treatment of TxX rats with cytokine-blocking mAbs was altering the development of disease and consequent involvement of Th1/Th2 T cell subsets to a response type that neither CD4+CD45RC− cells nor CD4+CD8− thymocytes could regulate. To examine this possibility, the IgG isotype of anti-Tg responses in reconstituted TxX rats treated with anti–IL-4 mAb or anti–TGF-β mAb was assessed to determine whether there had been a change in the relative activity of Th2 and Th1 cells in these rats. As the data show, the IgG isotypes in anti-Tg responses of rats reconstituted with either CD4+CD45RC− cells or CD4+CD8− thymocytes and treated with either anti–IL-4 or anti–TGF-β mAbs were the same as those of controls (Fig. 6). Anti-Tg responses of anti-cytokine-treated rats were predominantly of the Th2-associated IgG1 isotype, with little or no IgG2b anti-Tg detectable. Therefore, these data support the view that blockade of either IL-4 or TGF-β with neutralizing mAbs in TxX rats reconstituted with CD4+CD45RC− T cells or those given CD4+CD8− thymocytes abrogates the protection mediated by these populations with no modulation of the disease process itself.

Figure 6.

IgG isotypes of anti-Tg antibodies in TxX rats is not affected by their treatment with anti–IL-4 or anti–TGF-β blocking mAbs. The relative isotype usage of anti-Tg IgG responses was determined for TxX rats reconstituted with CD4+CD45RC− cells but treated with either anti–IL-4 (n = 9) or anti–TGF-β (n = 7) blocking mAbs and those reconstituted with CD4+CD8− thymocytes and treated with either anti-IL-4 (n = 6) or anti-TGF-β (n = 9) blocking mAbs from the experiments described in Fig. 5. The isotype of anti-Tg IgG in sera of control rats (n = 16) from both these series of experiments was similarly determined by specific ELISA. Data are expressed as the mean percentage of the anti-Tg response for a given IgG isotype where 100% is the sum of the ODs for individual isotypes above background of normal PVG sera in 1:10 dilutions of an experimental serum. Error bars indicate SD.

Discussion

There are close similarities between the autoimmune thyroiditis reported here and the insulin-dependent diabetes described in earlier papers from this laboratory. In both cases a tissue-specific autoimmune disease develops after experimentally induced lymphopenia, and the disease can be prevented by the injection of peripheral CD4+CD45RC− T cells or CD4+CD8− thymocytes from normal syngeneic donors (reference 9 and Fig. 2). However, there are significant differences that are informative in determining the mode of action of the regulatory T cells that prevent these diseases.

The diabetes that develops in lymphopenic PVG.RT1u rats has the features of a cell-mediated disease in which CD8+ T cells play an essential role. In contrast, the autoimmune thyroiditis in TxX PVG rats, described in this paper, is characterized by a strong humoral component. CD8+ T cells are not required for the development of this disease (Fig. 1 B) and the anti-Tg IgG antibodies that develop are predominantly of the IgG1 isotype (Fig. 1 A). In principle, this observation could be explained if PVG rats are able to make only a Th2-type immune response to Tg. However, active immunization of PVG rats with Tg/CFA induces anti-Tg antibodies that are mainly IgG2b rather than IgG1 (Fig. 1 A) demonstrating that PVG rats, when appropriately challenged, are able to make an anti-Tg antibody response characteristic of Th1 activity. Despite the fact that the diabetes and thyroiditis that develop in TxX rats have characteristics of Th1 and Th2 autoimmune responses respectively, the same CD4+CD45RC− subset of peripheral T cells was able to completely prevent both diseases (Fig. 2 and reference 6). This observation counters the suggestion that regulatory T cells prevent diabetes in TxX PVG.RT1u rats by inducing a Th1 to Th2 switch in the autoimmune response. Similarly, the suppression of autoantibody synthesis in the TxX PVG rats by the transfer of CD4+CD45RC− T cells is incompatible with such a change in T cell function since the anti-Tg autoantibody in unprotected rats already has the characteristics of a Th2 response. Taken together, the data from the two autoimmune diseases do not support the proposal that the control of autoimmunity involves a change in the balance between Th1 and Th2 responses to an autoantigen (32, 33). Instead, the regulatory T cells that prevent organ-specific autoimmune diseases appear to suppress autoimmune T cells completely. A recent publication draws the same conclusion (34).

The experiments on the relative potency of peripheral CD4+CD45RC− T cells and CD4+CD8− thymocytes in controlling thyroiditis in TxX PVG rats indicated that the latter cells were effective at one-tenth the dose of the peripheral ones (Fig. 4), a result that closely resembles the findings on the control of autoimmune diabetes in PVG.RT1u rats (9). The experiments on the mode of action of these regulatory cells in preventing thyroiditis indicated that both IL-4 and TGF-β are involved in this mechanism (Figs. 5 and 6), and this was true whether peripheral T cells or thymocytes were used to control the disease. This result suggests that the differences in the numbers of protective cells from these two sources, required to control autoimmunity in TxX rats, cannot be explained in terms of differences in the way in which they mediated protection. This conclusion is relevant when considering the nature of the homeostatic mechanism that controls the size of the regulatory T cell population. When CD4+CD8− thymocytes were used to prevent these diseases, they were injected into recipients that were highly deficient in regulatory T cells. Consequently, a homeostatic control mechanism would be expected to permit a relatively large number of thymocyte precursors to differentiate into cells with regulatory function. In contrast, there is evidence (see below) that the mature peripheral CD4+CD45RC− regulatory T cells, which were obtained from normal, healthy donors, represent a population whose frequency has been subject to homeostatic control within these nonlymphopenic animals. It appears that few extra regulatory T cells (T reg) can be recruited from the peripheral T cell pool when donor CD4+ T cells are transferred into TxX recipients. Consequently, peripheral T cells are a less potent source of T reg than are thymocytes that have not been exposed to the homeostatic mechanism that determines the size of the peripheral T reg population.

The intrinsic nature of the homeostatic mechanism is not directly addressed by these experiments but the data are best explained by a process in which the number of thymocytes that develop into peripheral regulatory T cells is determined by the requirement that this number should be just adequate to control the potentially autoreactive T cells that are part of the normal T cell repertoire (6). As with the previous observations on the control of diabetes in TxX rats (9), the data in Fig. 4 show that the percentage of rats protected from autoimmunity by CD4+CD8− thymocytes is very insensitive to the dose of thymocytes used and that the majority of, but not all, rats are protected from thyroiditis by unfractionated CD4+ peripheral T cells. In the experiments on diabetes in TxX rats, we proposed that these findings indicated that there is a delicate balance between the number of autoreactive T cells in the periphery and the number of T reg that control them, with the latter population being in a slight functional excess. This interpretation was supported by the close agreement between the experimental findings and a mathematical model based on this concept (9). The data presented here on autoimmune thyroiditis are also compatible with this interpretation. The most economical explanation of how this balance between the two populations of T cells is achieved is that exposure of regulatory T cell precursors and potentially autoreactive T cells to the specific autoantigen leads to an interaction between them and that this interaction ceases only after the regulatory T cells so generated are sufficient to control the autoreactive T cells. This hypothesis would require the presence of the relevant autoantigen in the periphery to transiently stimulate the autoreactive T cells. Consistent with this proposed mechanism, we have recently shown that peripheral regulatory T cells that prevent thyroiditis are not found in rats whose thyroids have been ablated by 131I treatment in utero (Seddon, B., and D. Mason, manuscript submitted for publication). In summary, the data indicate that the mature CD4+CD8− thymocyte population contains a high frequency of cells that have the potential to differentiate in the periphery into regulatory T cells that prevent organ-specific autoimmunity. In normal animals this differentiation is homeostatically controlled, such that the number of regulatory T cells generated is just sufficient to prevent disease. The generation of regulatory T cells in the periphery from thymic migrants does not take place in the absence of the target autoantigen, so the numerical balance between autoreactive and regulatory T cells is not established. Under such circumstances, the engraftment of the relevant organ leads to its rejection (35).

The immunosuppressive effect of TGF-β has been reported in a number of systems (36–40) and has been implicated in suppression of both cell-mediated responses, as in models of inflammatory bowel disease (41) and humoral autoimmunity induced by mercuric chloride (31). Consequently, the essential role that it plays in the prevention of autoimmune thyroiditis in TxX rats is not unexpected. As TGF-β prevents T cell activation but does not kill activated cells, it appears that T reg suppress but do not eliminate autoreactive T cells. This conclusion is compatible with the observation that such autoreactive cells form part of the normal T cell repertoire, but it raises the question of the value of a mechanism that preserves self-tolerance but also preserves the autoreactive cells. As discussed elsewhere (42), the establishment of self-tolerance by a mechanism that irreversibly silences all potentially autoreactive T cells would virtually completely deplete the T cell repertoire. The implication seems to be that the maintenance of self-tolerance by a dominant regulatory process is required to preserve a T cell repertoire that can react to essentially all foreign MHC-binding peptides. If this is so, then T reg would be required to inhibit autoreactive T cells when these are stimulated by self-antigens but not by foreign ones. This distinction may come about because peripheral autoreactive T cells for self-antigens have low affinity receptors for self-epitopes since T cells with high affinity receptors have been intrathymically clonally deleted. It is notable in this context that there is compelling evidence for the intrathymic expression of many “tissue-specific” autoantigens, including insulin and Tg (43–45) and that polymorphisms in the level of expression influence susceptibility (46).

A deficiency of IL-4 has been implicated in the pathogenesis of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in the NOD mouse (33, 47, 48) but this view is not universally accepted (49). Furthermore, IL-4 plays no essential part in the prevention of inflammatory bowel disease in mice (41), and regulatory T cells that prevent this condition appear not to produce this cytokine in vitro (50). In contrast, in our current experiments the neutralization of IL-4 by specific antibody completely abrogated the protection from autoimmune thyroiditis provided by the transfer of syngeneic CD4+ T cells. Although this result would at first appear to contradict the view that autoimmune thyroiditis is mediated by a humoral Th2 mechanism, it is possible that the requirement for IL-4 by regulatory and autoreactive T cells may occur at different times, even if the same anatomical site is implicated. Support for this comes from the observation that suppression of disease by reconstitution of rats with T cells is only successful up to 2 but not 4 wk after the last irradiation (30), whereas development of anti-Tg antibodies in TxX PVG rats occurs only between 4 and 12 wk after the last irradiation. Despite this finding, we cannot conclude with certainty that there was a deficiency of IL-4 in the rats that developed thyroiditis, since a deficiency in TGF-β would have sufficed to cause the disease. The IgG1 isotype of the anti-Tg antibody in the rats with thyroiditis is compatible with the presence of IL-4, but this antibody isotype is not strictly IL-4–dependent (51). Despite these uncertainties, the experimental data in Figs. 5 and 6 indicate that an anti–IL-4 antibody–induced IL-4 deficiency does result in the development of autoimmune thyroiditis in TxX rats.

Relevant to discussions of the possible functional role of IL-4 in the prevention of autoimmunity, it is significant that mouse T cells activated in the presence of IL-4 secrete high levels of TGF-β during both primary and secondary stimulations (52). This raises the possibility that IL-4 is a growth factor for regulatory T cells, whereas TGF-β acts as the effector cytokine in the suppression of autoimmune responses such that a deficiency of either cytokine will result in breakdown of regulation. Consequently, these data are in accord with those studies that implicate a deficiency of IL-4 in the pathogenesis of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in NOD mice and suggest that it plays an important role in the prevention of organ-specific autoimmune diseases. The failure to show a similar involvement of this cytokine in the prevention of inflammatory bowel disease indicates that regulatory T cells do not necessarily form a functionally homogeneous population.

Footnotes

Thanks go to Liz Darley, Ruth Goddard, Michael Puklavec, and Steve Simmonds for technical assistance. Thanks also to Catarina Amorim, Francisco Ramirez and Leigh Stevens together with other members of the Cellular Immunology Unit for discussion and interest.

Benedict Seddon is supported by the Wellcome Trust.

Abbreviations used in this paper: TDL, thoracic duct lymphocytes; Tg, thyroglobulin; NOD, nonobese diabetic; PVG, PVG.RT1c; T reg, regulatory T cells.

References

- 1.Taguchi O, Nishizuka Y, Sakakura T, Kojima A. Autoimmune oophoritis in thymectomized mice: detection of circulating antibodies against oocytes. Clin Exp Immunol. 1980;40:540–553. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taguchi O, Takahashi T. Administration of anti-interleukin-2 receptor alpha antibody in vivo induces localized autoimmune disease. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1608–1612. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asano M, Toda M, Sakaguchi N, Sakaguchi S. Autoimmune disease as a consequence of developmental abnormality of a T cell subpopulation. J Exp Med. 1996;184:387–396. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonomo A, Kehn P, Shevach E. Post-thymectomy autoimmunity: abnormal T-cell homeostasis. Immunol Today. 1995;16:61–67. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saoudi A, Seddon B, Heath V, Fowell V, Mason D. The physiological role of regulatory T cells in the prevention of autoimmunity: the function of the thymus in the generation of the regulatory T cell subset. Immunol Rev. 1996;149:195–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1996.tb00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fowell D, Mason D. Evidence that the T cell repertoire of normal rats contains cells with the potential to cause diabetes. Characterization of the CD4+T cell subset that inhibits this autoimmune potential. J Exp Med. 1993;177:627–636. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.3.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKnight AJ, Barclay AN, Mason DW. Molecular cloning of rat interleukin 4 cDNA and analysis of the cytokine repertoire of subsets of CD4+T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:1187–1194. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spickett GP, Brandon MR, Mason DW, Williams AF, Woollett GR. MRC OX-22, a monoclonal antibody that labels a new subset of T lymphocytes and reacts with the high molecular weight form of the leukocyte-common antigen. J Exp Med. 1983;158:795–810. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.3.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saoudi A, Seddon B, Fowell D, Mason D. The thymus contains a high frequency of cells that prevent autoimmune diabetes on transfer into pre-diabetic recipients. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2393–2398. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Penhale WJ, Farmer A, McKenna RP, Irvine WJ. Spontaneous thyroiditis in thymectomized and irradiated Wistar rats. Clin Exp Immunol. 1973;15:225–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penhale WJ, Farmer A, Irvine WJ. Thyroiditis in T cell-depleted rats. Influence of strain, radiation dose, adjuvants and antilymphocyte serum. Clin Exp Immunol. 1975;21:362–375. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams AF, Galfre G, Milstein C. Analysis of cell surfaces by xenogeneic myeloma-hybrid antibodies: differentiation antigens of rat lymphocytes. Cell. 1977;12:663–673. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMaster WR, Williams AF. Identification of Ia glycoproteins in rat thymus and purification from rat spleen. Eur J Immunol. 1979;9:426–433. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830090603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brideau RJ, Carter PB, McMaster WR, Mason DW, Williams AF. Two subsets of rat T lymphocytes defined with monoclonal antibodies. Eur J Immunol. 1980;10:609–615. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830100807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunt SV, Fowler MH. A repopulation assay for B and T lymphocyte stem cells employing radiation chimaeras. Cell Tissue Kinet. 1981;14:445–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1981.tb00551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsiung LM, Barclay AN, Brandon MR, Sim E, Porter RR. Purification of human C3b inactivator by monoclonal-antibody affinity chromatography. Biochem J. 1982;203:293–298. doi: 10.1042/bj2030293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCall MN, Shotton DM, Barclay AN. Expression of soluble isoforms of rat CD45. Analysis by electron microscopy and use in epitope mapping of anti-CD45R monoclonal antibodies. Immunology. 1992;76:310–317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woollett GR, Barclay AN, Puklavec M, Williams AF. Molecular and antigenic heterogeneity of the rat leukocyte-common antigen from thymocytes and T and B lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1985;15:168–173. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830150211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramirez F, Fowell DJ, Puklavec M, Simmonds S, Mason D. Glucocorticoids promote a Th2 cytokine response by CD4+T cell in vitro. J Immunol. 1996;156:2406–2412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucas C, Bald LN, Fendly BM, Mora-Worms M, Figari IS, Patzer EJ, Palladino MA. The autocrine production of transforming growth factor-beta 1 during lymphocyte activation. A study with a monoclonal antibody-based ELISA. J Immunol. 1990;145:1415–1422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnstable CJ, Bodmer WF, Brown G, Galfre G, Milstein C, Williams AF, Ziegler A. Production of monoclonal antibodies to group A erythrocytes, HLA and other human cell surface antigens—new tools for genetic analysis. Cell. 1978;14:9–20. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gowans JL, Knight EJ. The route of re-circulation of lymphocytes in the rat. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1964;159:257–282. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1964.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mason, D.W., W.J. Penhale, and J.D. Sedgwick. 1987. Preparation of lymphocyte subpopulations. In Lymphocytes: A Practical Approach. G.G.B. Klaus, editor. IRL Press Ltd., Oxon, England. 35–54.

- 24.Bendelac A, Carnaud C, Boitard C, Bach JF. Syngeneic transfer of autoimmune diabetes from diabetic NOD mice to healthy neonates. Requirement for both L3T4+ and Lyt-2+T cells. J Exp Med. 1987;166:823–832. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.4.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rapoport MJ, Jaramillo A, Zipris D, Lazarus AH, Serreze DV, Leiter EH, Cyopick P, Danska JS, Delovitch TL. Interleukin 4 reverses T cell proliferative unresponsiveness and prevents the onset of diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:87–99. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mueller R, Krahl T, Sarvetnick N. Pancreatic expression of interleukin-4 abrogates insulitis and autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1093–1099. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian J, Clare-Salzler M, Herschenfeld A, Middleton B, Newman D, Mueller R, Arita S, Evans C, Atkinson MA, Mullen Y, et al. Modulating autoimmune responses to GAD inhibits disease progression and prolongs islet graft survival in diabetes-prone mice. Nat Med. 1996;2:1348–1353. doi: 10.1038/nm1296-1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saoudi A, Kuhn J, Huygen K, de-Kozak Y, Velu T, Goldman M, Druet P, Bellon B. TH2 activated cells prevent experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis, a TH1- dependent autoimmune disease. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:3096–3103. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830231208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gracie JA, Bradley JA. Interleukin-12 induces interferon-gamma-dependent switching of IgG alloantibody subclass. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1217–1221. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Penhale WJ, Irvine WJ, Inglis JR, Farmer A. Thyroiditis in T cell-depleted rats: suppression of the autoallergic response by reconstitution with normal lymphoid cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 1976;25:6–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bridoux F, Badou A, Saoudi A, Bernard I, Druet E, Pasquier R, Druet P, Pelletier L. Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)–dependent inhibition of T helper cell 2 (Th2)-induced autoimmunity by self-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II–specific, regulatory CD4+T cell lines. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1769–1775. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.10.1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liblau RS, Singer SM, McDevitt HO. Th1 and Th2 CD4+ T cells in the pathogenesis of organ-specific autoimmune diseases. Immunol Today. 1995;16:34–38. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cameron MJ, Arreaza GA, Zucker P, Chensue SW, Strieter RM, Chakrabarti S, Delovitch TL. IL-4 prevents insulitis and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in nonobese diabetic mice by potentiation of regulatory T helper-2 cell function. J Immunol. 1997;159:4686–4692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Garra A, Steinman L, Gijbels K. CD4+ T-cell subsets in autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:872–883. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eishi Y, McCullagh P. Acquisition of immunological self-recognition by the fetal rat. Immunology. 1988;64:319–323. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shull MM, Ormsby I, Kier AB, Pawlowski S, Diebold RJ, Yin M, Allen R, Sidman C, Proetzel G, Calvin D, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature. 1992;359:693–699. doi: 10.1038/359693a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kulkarni AB, Huh CG, Becker D, Geiser A, Lyght M, Flanders KC, Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Ward JM, Karlsson S. Transforming growth factor beta 1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:770–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller A, Lider O, Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Weiner HL. Suppressor T cells generated by oral tolerization to myelin basic protein suppress both in vitro and in vivo immune responses by the release of transforming growth factor beta after antigen-specific triggering. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:421–425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weiner HL, Friedman A, Miller A, Khoury SJ, al-Sabbagh A, Santos L, Sayegh M, Nussenblatt RB, Trentham DE, Hafler DA. Oral tolerance: immunologic mechanisms and treatment of animal and human organ-specific autoimmune diseases by oral administration of autoantigens. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:809–837. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.004113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han HS, Jun HS, Utsugi T, Yoon JW. A new type of CD4+ suppressor T cell completely prevents spontaneous autoimmune diabetes and recurrent diabetes in syngeneic islet-transplanted NOD mice. J Autoimmun. 1996;9:331–339. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1996.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Powrie F, Carlino J, Leach MW, Mauze S, Coffman RL. A critical role for transforming growth factor-β but not interleukin 4 in the suppression of T helper type 1–mediated colitis by CD45RBlow CD4+T cells. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2669–2674. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mason D. A very high level of cross-reactivity is an essential feature of the T cell receptor. Immunol Today. 1998;19:395–404. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01299-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morahan G, Allison J, Miller JF. Tolerance of class I histocompatibility antigens expressed extrathymically. Nature. 1989;339:622–624. doi: 10.1038/339622a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Antonia SJ, Geiger T, Miller J, Flavell RA. Mechanisms of immune tolerance induction through the thymic expression of a peripheral tissue-specific protein. Int Immunol. 1995;7:715–725. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heath VL, Moore NC, Parnell SM, Mason DW. Intrathymic expression of genes involved in organ specific autoimmune disease. J Autoimmun. 1998;11:309–318. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1998.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vafiadis P, Bennett ST, Todd JA, Nadeau J, Grabs R, Goodyer CG, Wickramasinghe S, Colle E, Polychronakos C. Insulin expression in human thymus is modulated by INS VNTR alleles at the IDDM2 locus. Nat Genet. 1997;15:289–292. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gombert JM, Herbelin A, Tancrede-Bohin E, Dy M, Carnaud C, Bach JF. Early quantitative and functional deficiency of NK1+-like thymocytes in the NOD mouse. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2989–2998. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gombert JM, Herbelin A, Tancrede-Bohin E, Dy M, Chatenoud L, Carnaud C, Bach JF. Early defect of immunoregulatory T cells in autoimmune diabetes. C R Acad Sci III. 1996;319:125–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Katz JD, Benoist C, Mathis D. T helper cell subsets in insulin-dependent diabetes. Science. 1995;268:1185–1188. doi: 10.1126/science.7761837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Groux H, O'Garra A, Bigler M, Rouleau M, Antonenko S, de-Vries JE, Roncarolo MG. A CD4+ T-cell subset inhibits antigen-specific T-cell responses and prevents colitis. Nature. 1997;389:737–742. doi: 10.1038/39614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.von-der-Weid T, Kopf M, Kohler G, Langhorne J. The immune response to Plasmodium chabaudimalaria in interleukin-4-deficient mice. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:2285–2293. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seder RA, Marth T, Sieve MC, Strober W, Letterio JJ, Roberts AB, Kelsall B. Factors involved in the differentiation of TGF-beta-producing cells from naive CD4+ T cells: IL-4 and IFN-gamma have opposing effects, while TGF-beta positively regulates its own production. J Immunol. 1998;160:5719–5728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]