Abstract

PIR-A and PIR-B, paired immunoglobulin-like receptors encoded, respectively, by multiple Pira genes and a single Pirb gene in mice, are relatives of the human natural killer (NK) and Fc receptors. Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies produced against a recombinant PIR protein identified cell surface glycoproteins of ∼85 and ∼120 kD on B cells, granulocytes, and macrophages. A disulfide-linked homodimer associated with the cell surface PIR molecules was identified as the Fc receptor common γ (FcRγc) chain. Whereas PIR-B fibroblast transfectants expressed cell surface molecules of ∼120 kD, PIR-A transfectants expressed the ∼85-kD molecules exclusively intracellularly; PIR-A and FcRγc cotransfectants expressed the PIR-A/ FcRγc complex on their cell surface. Correspondingly, PIR-B was normally expressed on the cell surface of splenocytes from FcRγc−/− mice whereas PIR-A was not. Cell surface levels of PIR molecules on myeloid and B lineage cells increased with cellular differentiation and activation. Dendritic cells, monocytes/macrophages, and mast cells expressed the PIR molecules in varying levels, but T cells and NK cells did not. These experiments define the coordinate cellular expression of PIR-B, an inhibitory receptor, and PIR-A, an activating receptor; demonstrate the requirement of FcRγc chain association for cell surface PIR-A expression; and suggest that the level of FcRγc chain expression could differentially affect the PIR-A/PIR-B equilibrium in different cell lineages.

Keywords: Fc receptor γ chain, activating receptor, inhibitory receptor, dendritic cells, innate immunity

The paired immunoglobulin-like receptors (PIR)1-A and -B have been identified recently in mice on the basis of their homology with the human Fcα receptor (FcαR) (1, 2). PIR-A and PIR-B share sequence similarity with a gene family that includes human FcαR and killer inhibitory receptors (KIR), mouse gp49, bovine Fc receptor for IgG (FcγR), and the recently identified human Ig-like transcripts (ILT)/leukocyte Ig-like receptors (LIR)/monocyte/macrophage Ig-like receptors (MIR) (3–12). The Pira and Pirb genes are located on mouse chromosome 7 in a region syntenic with the human chromosome 19q13 region that contains the FcαR, KIR, and ILT/LIR/MIR genes (1, 4, 5, 9, 11–14). DNA sequences for PIR-A and PIR-B predict type I transmembrane proteins with similar ectodomains (>92% homology) each containing six Ig-like domains. However, PIR-A and PIR-B have distinctive membrane proximal, transmembrane, and cytoplasmic regions. The PIR-B protein, encoded by the Pirb gene (1, 13, 15), has a typical uncharged transmembrane region and a long cytoplasmic tail with multiple candidate immunoreceptor tyrosine–based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs). Recent studies have demonstrated the inhibitory function of the two most membrane-distal ITIM units in the PIR-B cytoplasmic region (16, 17). The PIR-B inhibitory function is mediated through ITIM recruitment of the protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 (16, 17). Conversely, the predicted PIR-A protein has a short cytoplasmic tail and a charged arginine residue in its transmembrane region, suggesting possible association with transmembrane proteins containing immunoreceptor tyrosine–based activation motifs (ITAMs) to form a signal-transducing unit. In addition, the PIR-A receptors, which are encoded by multiple Pira genes, display sequence diversity in their extracellular regions.

In this study, monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies specific for common epitopes on PIR-A and PIR-B molecules were used to characterize these cell surface receptors and the cellular distribution of their expression in normal and Fc receptor common γ chain (FcRγc)–deficient mice. The results indicate an essential role for PIR-A association with the FcRγc for cell surface expression on B lineage, myeloid, and dendritic cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell Preparation.

Bone marrow cells were isolated from the femur by flushing with media, and the erythrocytes lysed in a 0.1 M ammonium chloride buffer solution at pH 7.4. Splenocytes were prepared by splenic disruption, gentle teasing, and density gradient centrifugation over Lympholyte®-M (Accurate Chemistry & Science Corp.). Splenic B cells were enriched by depletion of Mac-1+ macrophages and granulocytes and of CD3+ T cells by a panning method (18). Granulocytes were isolated from peritoneal exudates induced by prior injection of 0.4% (wt/vol) calcium caseinate (Spectrum Quality Products, Inc.).

Preparation of Recombinant PIR Protein.

The PIR extracellular domains EC1 and EC2 were amplified by PCR using Taq DNA polymerase and the PIR-A1 cDNA as the template. The forward primer, 5′-GCACGGATCCCTCCCTAAGCCTATCCTCAGA-3′, corresponds with the 5′ side of the EC1 (the BamHI site is underlined), and the reverse primer 5′-TATCGATAAG CTTGAGACCAGGAGCTCCA-3′, with the 3′ side of the EC2 (the HindIII site being underlined). The ∼570-bp products were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis, digested with BamHI and HindIII, and ligated into the pQE30 expression vector (Qiagen) which was used to transform Escherichia coli, strain M15. The His-tagged PIR-A1 EC1/EC2 protein produced by transformed M15 cells after induction with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was purified on an affinity column (Ni-nitrilo-tri-acetic acid resin; Qiagen), eluted with 8 M urea/0.1 M acetate buffer, pH 4.5, and renatured by dialysis against PBS.

Production of Monoclonal and Polyclonal Antibodies.

Lewis rats were immunized five times at weekly intervals with 50 μg of purified PIR-A1 EC1/EC2 protein. The rats were then boosted with the WEHI3 myeloid cell line (107 cells), which expresses PIR-A and PIR-B transcripts (1), a day before fusion of regional lymph node cells with the Ig nonproducing murine plasmacytoma cell line (Ag8.653) (19). Hybridoma culture supernatants were screened for reactivity with the recombinant protein by ELISA using alkaline phosphatase–labeled goat antibodies specific for rat Ig (Southern Biotechnology Associates). ELISA reactive supernatants were examined for immunofluorescence cell surface reactivity with the PIR+ WEHI3 and PIR− M1 cell lines using PE-labeled goat antibodies specific for rat Ig. Selected hybridoma clones were subcloned by limiting dilution in the presence of rIL-6 (1 U/ml; GIBCO BRL). Ig isotypes of the mAbs were determined with a rat mAb ELISA kit (Zymed Co.). Anti-PIR mAbs purified from culture supernatants by protein-G affinity columns were labeled with PE or biotin. A New Zealand White rabbit was hyperimmunized with the recombinant PIR-A1 EC1/ EC2 protein (50 μg, six times) over a 2-mo period, and the antiserum collected 10 d after the final immunization.

Transfection.

Expression vectors were constructed by digesting the original PIR-A1 and PIR-B cDNAs in the Bluescript phagemid vector with XbaI, filling the recessed 3′ termini with Klenow fragment, redigesting with XhoI, and separation by agarose gel electrophoresis. The separated XbaI (blunt ended)/XhoI fragments, ∼3.4 kb for PIR-A1 and ∼2.7 kb for PIR-B, were excised, purified, and ligated into the pcDNA3 expression vector that was predigested with EcoRV and XhoI and dephosphorylated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase to construct pcDNA3-PIR-A1 and pcDNA3-PIR-B. Since both PIR-A1 and PIR-B cDNAs contained additional ATG sites located upstream of the initiation codon, the 5′ untranslated regions were removed and replaced by Kozak sequence (20). This was accomplished by 67mer complementary oligonucleotides: the forward 5′-AGCT T GCCGCCACC ATGTCCTGCACCTTCACAG CCCTGCTCCGTCTTGGACTGACTCTGAGCCTCTG-3′ and the reverse 5′-GATCCAGAGGCTCAGAGTCAGTC CAAGACGGAGCAGGGCTGTGAAGGTGC AGGACAT- GGTGGCGGCA-3′; italic, underlined, and bold letters correspond with the cohesive ends of HindIII or BamHI, the Kozak sequence, and the signal sequence of both PIR-A1 and PIR-B cDNAs, respectively. The 5′-hydroxyl termini of both oligonucleotides were phosphorylated by T4 polynucleotide kinase, annealed, and ligated into the pcDNA3-PIR-A1 and pcDNA3-PIR-B expression vectors, from which the 100–200-bp HindIII/ BamHI fragments corresponding with the 5′ untranslated region and a part of the signal sequence of PIR-A1 and PIR-B cDNAs had been excised. After confirming the nucleotide sequences of the resultant PIR-A1 and PIR-B expression vectors, the plasmid DNAs were linearized by digesting with PvuI, transfected into LTK fibroblasts with the aid of lipofectin, and stable transfectants selected by Geneticin (G418) exposure.

For cotransfection of a murine FcRγc into the PIR-A1–transfected fibroblasts, the FcRγc expression vector was constructed by ligating the ∼400-bp FcRγc coding sequence from the original pcEXV-3 vector (21) into EcoRI-digested pBluescript II cloning vector. The pBlue-FcRγc construct with a correct orientation was digested with BamHI and XhoI to remove the FcRγc fragment, before ligation into the pcDNA3.1/Hygro(+) expression vector. The resulting expression vector pcDNA3.1/ Hygro-FcRγc was then linearized with AviII and transfected with the aid of Superfect into LTK fibroblasts which had been already transfected with PIR-A1. Stable cotransfectants were selected by Geneticin (G418) and Hygromycin B.

Western Blot Analysis.

B cells and myeloid cells (5 × 107 cells/sample) and PIR-A or PIR-B transfected LTK cells (106) were lysed in 500 μl of lysis buffer (1% NP-40 in 150 mM NaCl/ 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 5 mM EDTA, 20 mM iodoacetamide, 0.1% sodium azide, 20 mM ε-amino-caproic acid, antipain [2 μg/ml], leupeptin [1 μg/ml], soybean trypsin inhibitor [100 μg/ml], aprotinin [2 μg/ml], 1 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl)- benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride, chymostatin [2.5 μg/ml], and pepstatin [1 μg/ml]). A solid-phase immunoisolation technique (SPIT) (22) was used to identify anti-PIR reactive molecules in cell lysates precleared by centrifugation. In brief, 96-well plates were coated with goat antibodies to rat Ig and then with rat anti-PIR or isotype-matched control mAbs before incubation with cell lysates overnight at 4°C. After extensive washing, bound molecules were dissociated by addition of 2% SDS, resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes by electroblotting, incubated sequentially with rabbit anti-PIR antiserum (1:2,000 dilution) and horseradish peroxidase–labeled goat anti–rabbit Ig antibody (0.25 μg/ml; Southern Biotechnology Associates), and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Life Science). In other experiments, blotted membranes were incubated with rabbit antibodies against FcRγc (gift of Drs. Robert P. Kimberly and Jeffery C. Edberg, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL).

Immunoprecipitation of Cell Surface Proteins.

Viable cells (∼3 × 107) were surface labeled with 1 mCi of Na125I by the lactoperoxidase method (23) and solubilized in ∼500 μl of 1% NP-40 or 1% digitonin lysis buffers. After centrifugation, iodinated PIR molecules were isolated by SPIT, separated on SDS-PAGE (8–15% acrylamide) under reducing and nonreducing conditions, and the dried gels exposed to x-ray films (24). Alternatively, isolated PIR molecules were analyzed by nonreducing/reducing diagonal SDS-PAGE (25). In other experiments, cell surface PIR molecules were digested with N-glycanase (Oxford Glycosciences) before SDS-PAGE analysis (24).

Immunofluorescence Analysis.

Cells were incubated with aggregated human IgG to block FcγRs, then stained with PE-labeled anti-PIR mAbs and a combination of FITC-, cychrome (CY)-, allophycocyanin, or biotin-labeled mAbs specific for B220 (CD45R), CD19, CD21, CD23, CD43, or CD5 for B-lineage cells; CD3, CD4, or CD8 for T-lineage cells; Mac-1 (CD11b) or Gr-1 for myeloid lineage cells; DX5 antigen for pan NK cells; CD11c for dendritic cells; and Ter-119 for erythroid lineage cells (PharMingen). Other reagents included FITC-labeled goat anti– mouse μ chain antibody and isotype-matched control mAbs labeled with PE, FITC, CY, or biotin (Southern Biotechnological Associates). Stained cells were analyzed with a FACScan® flow cytometry instrument (Becton Dickinson).

Results

Generation of Monoclonal and Polyclonal Anti-PIR Antibodies.

Recombinant PIR protein containing the two NH2-terminal Ig-like extracellular domains, EC1 and EC2, in the PIR-A1 molecule was produced in E. coli. The PIR-A1 EC1/EC2 recombinant protein was selected to immunize rats because of its sequence identity with PIR-B (1). 1 d before fusion of regional lymph node cells to produce hybridomas, the immunized rats were boosted with viable WEHI3 myeloid cells to enhance the possibility of obtaining antibodies that recognize epitopes on native PIR molecules. 33 hybridoma clones produced antibodies that reacted by ELISA with the recombinant PIR-A1 EC1/EC2 protein. Cell surface immunofluorescence analysis indicated that one of the antibodies, 6C1 (γ1κ), was reactive with PIR-B–transfected LTK fibroblasts and the WEHI3 myeloid cell line (Fig. 1). This mAb was unreactive with mock-transfected LTK fibroblasts and the M1 myeloblastoid cell line that lack PIR-A and PIR-B transcripts. Binding of the 6C1 antibody to the WEHI3 cells was inhibited by the recombinant PIR-A1 EC1/EC2 protein in a dose-dependent manner. The recombinant PIR-A1 EC1/EC2 protein was also used to produce a rabbit antiserum, the specificity of which was indicated by ELISA and by Western blot assays of the native PIR-A and PIR-B proteins described below.

Figure 1.

Cell surface reactivity of the 6C1 anti-PIR mAb. Mouse LTK cells transfected with the empty vector (A), LTK cells transfected with the PIR-B expression vector (B), M1 myeloblastoid cells (C), and WEHI3 myeloid cells (D) were incubated with 6C1 rat anti-PIR mAb (shaded histogram) or an isotype-matched control mAb (open histogram), before developing with PE-labeled goat antibodies to rat Ig. The stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Biochemical Characteristics of the PIR-A and PIR-B Molecules.

When iodinated cell surface proteins on splenocytes, B cell lines, and macrophage cell lines were examined by SDS-PAGE, the anti-PIR antibodies identified two major species of ∼85 and ∼120 kD with minor bands of slightly lower molecular masses (Fig. 2 A). Slightly higher molecular masses were evident under reducing conditions, ∼90 and ∼125 kD, respectively, consistent with predicted intradisulfide linkages of the six Ig-like extracellular domains. N-glycanase treatment reduced their apparent molecular masses by 10–15 kD in keeping with the presence of five to six potential N-linked glycosylation sites in the PIR-A and PIR-B molecules (Fig. 2 B). Two- dimensional electrophoretic analysis under nonreducing and reducing conditions confirmed that the ∼85 and ∼120-kD proteins identified on splenocytes by the anti-PIR antibodies did not exist as covalently linked molecules (not shown). B cells purified from the spleen and granulocytes purified from peritoneal exudates also expressed ∼85 and ∼125-kD molecules (Fig. 2 C). These findings indicate that cell surface PIR molecules are glycoproteins of ∼85 and ∼120 kD, and that both molecular species are expressed by clonal B and myeloid cells.

Figure 2.

Analysis of cell surface and intracellular PIR molecules. Viable splenocytes from normal adult BALB/c mice were radiolabeled with 125I and solubilized in 0.5% NP-40. The cleared membrane lysates were incubated in wells precoated with 6C1 anti-PIR or an isotype-matched control mAb. The bound materials were resolved on SDS-PAGE using 10% acrylamide under nonreducing (not shown) and reducing conditions (A) or digested with or without N-glycanase before SDS-PAGE analysis (B). The same ∼85 and ∼125-kD PIR molecules were observed in splenocytes, purified splenic B cells, and granulocytes (C) as well as the X16C8.5 B cell and WEHI3 macrophage cell lines (D). In contrast, the 85-kD band was identified in PIR-A transfected fibroblasts, while the ∼120-kD band was expressed by the PIR-B transfectants (D). In the experiments shown in C and D, NP-40 lysates of splenocytes, purified B cells, granulocytes, the LTK cells transfected with empty vector or PIR-A1 or PIR-B expression vectors, the X16C8.5 B cell line, and the WEHI3 macrophage cell line were incubated in wells precoated with 6C1 anti-PIR mAb or isotype-matched control mAb (not shown). The bound PIR molecules were separated in SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions, transferred onto membranes, and identified with rabbit anti-PIR antiserum and enzyme-labeled goat anti–rabbit Ig antibody before visualization by enhanced chemiluminescence.

Since the monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies recognize epitopes present on both PIR-A and PIR-B molecules, mouse LTK cells transfected either with PIR-A1 or PIR-B cDNAs were used for discrimination of the PIR molecules. A major band of ∼120 kD, together with a faint band of ∼97 kD, was immunoprecipitated by the 6C1 anti-PIR mAb from lysates of the PIR-B transfectants, and not from lysates of mock transfectants probed by immunoblotting with the rabbit anti-PIR antibodies (Fig. 2 C). Conversely, the anti-PIR mAb precipitated a major band of ∼85 kD and a minor band of ∼70 kD from cell lysates of the PIR-A1 transfectants. The two major bands of 85 and 120 kD were also identified by the 6C1 mAbs and the rabbit anti-PIR antibodies in normal splenocytes, B cell, and myeloid cell lines, all of which express Pira and Pirb transcripts (1). The 6C1 anti-PIR mAb and the rabbit antiserum against recombinant PIR EC1/EC2 protein thus recognize native PIR-A and PIR-B molecules, the major species of which have relative molecular masses of ∼85 and ∼120 kD, respectively.

PIR-A Association with FcRγc.

The PIR-A protein has a short cytoplasmic tail without recognizable functional motifs, but the presence of a charged amino acid, arginine, in the transmembrane region suggested its potential association with another transmembrane protein (1). Inferential evidence in support of this possibility was provided by studies of the cell surface proteins expressed by PIR-A and PIR-B fibroblast transfectants. A major band of ∼120 kD was identified on the cell surface of PIR-B transfected LTK cells by the 6C1 antibodies (not shown), whereas the ∼85 and ∼70-kD molecules expressed by PIR-A1 transfectants (see Fig. 2 C) were identified only intracellularly. Cell surface PIR-A molecules were not identified by the anti-PIR mAb on PIR-A transfectants, thereby implying that PIR-A requires companion molecules, not present in fibroblasts, to reach the cell surface. Accordingly, two-dimensional analysis of the proteins precipitated with the 6C1 anti-PIR antibody from iodinated cell surface proteins on splenocytes revealed an associated homodimer composed of relatively small disulfide-linked subunits (∼10 kD, not shown). Immunoblots of the cell surface PIR complex separated under reducing conditions by SDS-PAGE identified these associated proteins as FcRγc (Fig. 3 B).

Figure 3.

Association of PIR-A with FcRγc. (A) Assessment of cell surface PIR-A expression on LTK fibroblasts transfected with PIR-A alone (left) or with PIR-A and FcRγc (right). Viable cells were incubated with fluorochrome-labeled 6C1 anti-PIR (shaded histogram) or isotype-matched control mAb (open histogram). (B) Assessment of PIR expression in FcRγc-deficient versus normal mice. Splenocytes from FcRγc-deficient (FcRγc−/−) or normal (FcRγc+/+) mice were either radiolabeled with 125I (top) or unlabeled (middle and bottom), lysed in 1% NP-40, and subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with the indicated mAbs. The immunoprecipitated, radiolabeled materials were resolved by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography (top). The materials isolated from unlabeled cells were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto membranes, blotted with rabbit anti-PIR (middle) or anti-FcRγc antibodies (bottom), and visualized by chemiluminescence.

The requirement of FcRγc association for the cell surface expression of PIR-A was examined by fibroblast cotransfection experiments. While PIR-A producing transfectants failed to express this product on the cell surface, fibroblasts cotransfected with the PIR-A and FcRγc constructs expressed readily detectable PIR-A on the cell surface (Fig. 3 A). The apparent requirement of FcRγc for cell surface expression of PIR-A molecules was examined further by the analysis of FcRγc chain–deficient (FcRγc−/−) mice. While splenocytes from the wild-type mice expressed both PIR-A and PIR-B on the cell surface, only the PIR-B was identified on the cell surface of splenocytes in FcRγc−/− mice (Fig. 3 B). This selective impairment of PIR-A cell surface expression in FcRγc−/− mice was not attributable to a lack of PIR-A production, since the 6C1 mAb identified both the 85-kD PIR-A and the 120-kD PIR-B molecules within FcRγc−/− splenocytes. Therefore, these findings indicate that FcRγc chains are required for the cell surface expression of PIR-A molecules.

Immunofluorescence Analysis of the Cellular Distribution of PIR Expression.

When bone marrow cells from adult mice were incubated with the fluorochrome-labeled 6C1 anti-PIR mAb, ∼80% of the nucleated cells were stained. Morphological analysis of isolated PIR+ cells indicated that most were myeloid cells, ranging from immature myeloblasts to mature granulocytes, whereas lymphocytes represented a minor constituent. When differential immunofluorescence analysis for other cell surface differentiation antigens was conducted to further characterize the PIR+ cells, bone marrow cells bearing the Gr-1 and Mac-1 (CD11b, CR3) myelomonocytoid antigens were found to express the PIR antigen at variable levels that correlated with Gr-1 expression levels (Fig. 4, first row). Examination of the morphological features of isolated PIRlo/Gr-1lo and PIRhi/ Gr-1hi fractions confirmed the increase in PIR and Gr-1 expression with progression of granulocyte differentiation. The B-lineage cells in bone marrow expressed PIR at lower levels relative to the myeloid cells, and most of the PIR+ B-lineage cells (CD19+) were IgM+ B cells; pro-B were PIR negative while pre-B cells were found to express PIR at low levels (Fig. 4, second and third rows), indicating a gradual increase in PIR expression as a function of B-lineage differentiation. Bone marrow–derived, IL-3–induced mast cells (c-kit+) also expressed PIR on their cell surface. PIR proteins were not detected on erythroid lineage cells (Ter119+) in the bone marrow. CD3+ thymocytes from newborn and adult BALB/c mice were PIR negative. In striking contrast, thymic dendritic cells (MHC class II+, CD11c+, CD8+, CD3−, CD4−, CD19−, Mac-1−, FcγRII/III−) expressed PIR from relatively low to high levels (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Immunofluorescence analysis of cell surface PIR expression. Bone marrow (BM), spleen (SP), and peritoneal lavage (PEC) cells from adult BALB/c mice were incubated first with aggregated human IgG to block FcγR, then stained with a combination of PE-labeled 6C1 anti-PIR and FITC-, CY-, allophycocyanin-, or biotin-labeled (and CY-labeled streptavidin) mAbs with the following specificity: Mac-1 and Gr-1 for myeloid lineage cells (first row); CD43 and B220 antigens for pro-B/pre-B cell compartment (second row); CD19 and IgM for B lineage cells (third row); CD3 and DX5 for T and NK cells and CD19 or Mac-1 for B cells and macrophages (fourth row); B220, CD21, and CD23 for marginal zone (MZ), follicular (FO), and newly formed (NF) B cells (fifth row); CD19, CD5, and Mac-1 for B1 and B2 subpopulations (sixth row). Staining of cells with light scatter characteristics of myeloid cells or small lymphoid and larger mononuclear cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. In the bottom two rows, B220+ or CD19+ B cells were examined for expression of the indicated cell surface antigens. The cell populations indicated by boxes in contour plots were examined for their expression of PIR molecules (solid line) versus background staining with an isotype-matched control mAb (dashed line). MFI indicates mean fluorescence intensity.

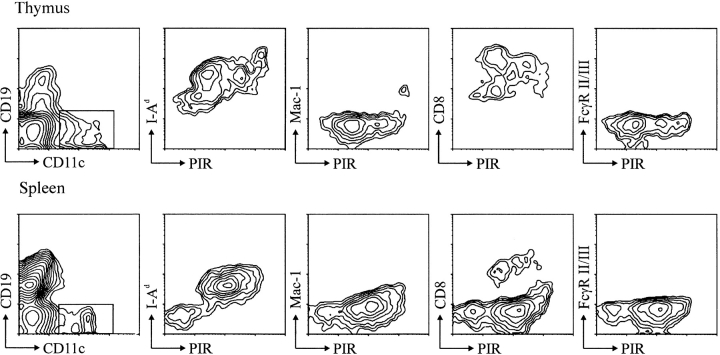

Figure 5.

PIR expression by thymic and splenic dendritic cells. (Top) Thy-1+ T and B220+ B cells were depleted from thymic cell suspensions by complement-mediated lysis, and the remaining cells were stained with the indicated mAbs. The CD11c+/CD19− cells, which comprised ∼1% of the initial MNC population, were analyzed for the expression of PIR and other cell surface markers (MHC I-Ad, Mac-1, CD8, and FcγRII/ III). (Bottom) Splenocytes were stained similarly, and the CD11c+/CD19− cells analyzed for other cell surface antigens.

Splenic B cells and macrophages expressed the PIR antigen on their cell surface, whereas NK cells and T cells did not (Fig. 4, fourth row), results consistent with the expression patterns noted for PIR-A and PIR-B transcripts in these cell types (1). PIR expression was higher on myeloid lineage cells than on splenic B cells, the latter bearing the 6C1-identified PIR molecules in highly variable levels. When subpopulations of splenic B cells were evaluated, the marginal zone B cells (B220+, CD21high, CD23low/−) were found to express higher PIR levels than newly formed (B220+, CD21−, CD23−) and follicular B cells (B220+, CD21med, CD23+) (Fig. 4, fifth row). Moreover, the B1 subpopulations of B cells in peritoneal lavage expressed higher levels of PIR than did the B2 cells (Fig. 4, sixth row). Consistent with this suggestive evidence that B cell activation may enhance PIR expression, cell surface levels of PIR were upregulated by ∼33% after LPS stimulation of splenic B cells, and macrophage PIR expression was similarly enhanced by LPS stimulation. Splenic dendritic cells (MHC class II+, CD11c+, CD19−, Mac-1−, CD8+/−, FcγRII/III−), like thymic dendritic cells, were found to express relatively low to relatively high levels of PIR (Fig. 5).

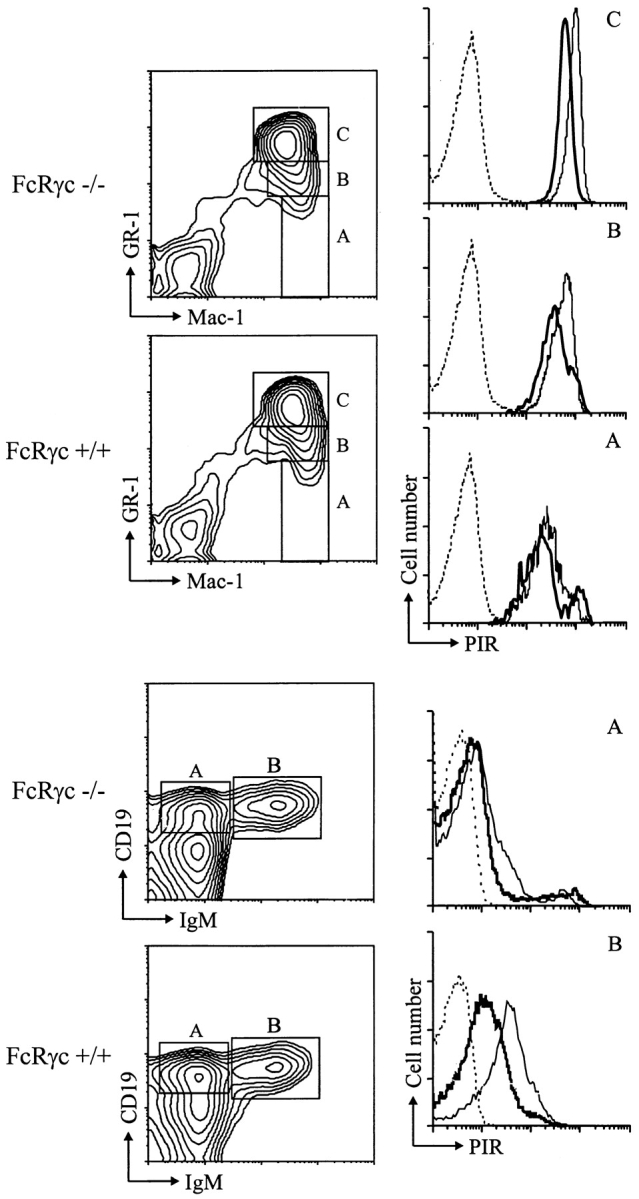

Cell Surface Expression Levels of PIR-B in FcRγc− /− mice.

Since cell surface expression of PIR-A was selectively impaired in FcRγc-deficient mice, PIR-B expression relative to total PIR-A/PIR-B expression could be estimated by immunofluorescence comparison of the cells from FcRγc-deficient and wild-type mice. Cell surface PIR-B expression alone was thereby found to increase in the FcRγc-deficient mice as a function of both myeloid and B lineage differentiation (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

PIR expression in FcRγc-deficient and wild-type mice. Bone marrow cells from FcRγc-deficient (thick line) and wild type mice (thin line) were stained with 6C1 anti-PIR or control (dotted line) mAb, and the stained cells were analyzed as described in the legend for Fig. 4. Only the wild-type mice control staining is illustrated.

Discussion

The monoclonal and polyclonal anti-PIR-A/PIR-B antibodies described here define the cell surface PIR-A and PIR-B receptors as glycoproteins of ∼85 and ∼120 kD, respectively. The ∼120-kD estimate for PIR-B agrees with that obtained using a rabbit antiserum against a p91/ PIR-B cytoplasmic peptide (2). In the present studies, the coordinate or paired expression of PIR-A and PIR-B by B and myeloid cells suggested by transcriptional analysis (1) was confirmed by demonstration of both molecules on representative clonal cell lines. Given the finding of splice variants among PIR-A cDNAs (1), we anticipated considerable size heterogeneity of the PIR-A proteins. Contrary to this expectation, the cell surface PIR-A and PIR-B receptors were relatively homogeneous in size, and the predominant protein species were physically indistinguishable in different cell types (B cells versus macrophages) and cell sources (cell lines versus splenocytes). The products of splice variant PIR-A cDNAs thus appear to comprise only a minor fraction of the total PIR-A pool. The PIR-A and PIR-B cDNA sequences indicate an additional free Cys residue in their ectodomains (1), thus suggesting the possible existence of disulfide-linked dimers of the PIR-A and PIR-B molecules. However, disulfide linkage of these molecules was not evident in either one- or two-dimensional gel electrophoresis analyses. It is still theoretically possible that cell surface PIR-A and PIR-B molecules could form noncovalent associations with functional consequence.

Intriguingly, the anti-PIR mAb recognized the PIR-B cell surface receptor on PIR-B transfectants, whereas PIR-A cell surface molecules could not be detected on PIR-A1 producing transfectants. This finding implied the requirement for additional membrane-bound protein(s) for PIR-A cell surface expression, a possibility that was also suggested by the presence of a charged Arg residue in the transmembrane region of the predicted PIR-A1 protein (1). There are well documented precedents for the noncovalent association of Ig-like receptor chains containing such charged transmembrane regions with another membrane-bound protein for cell surface expression and/or function. These include (a) the association of ligand-binding α chain of several Fc receptors (FcεR, FcγRI, FcγRIII, FcαR) with signal transducing subunits (β, γ, or ζ); (b) the TCR/CD3 complexes; and (c) the killer activating receptor/dendritic associated protein-12 or killer activating receptor associating protein complexes (20, 26–38). In these examples, the associated proteins typically contain ITAMs in their cytoplasmic domains (31, 39–42). Our immunoprecipitation analysis indicated that the ITAM-containing FcRγc is associated with PIR molecules present on the cell surface. The implication that the FcRγc is essential for PIR-A cell surface expression was confirmed in fibroblast cotransfection studies and by the selective expression of PIR-B molecules on B cells and myeloid cells in FcRγc-deficient mice. In studies reported since submission of this manuscript, a cell activation for the PIR-A/FcRγc complex has been demonstrated in rat mast cell line and chicken B cell line transfected with constructs for chimeric proteins containing the PIR-A transmembrane and cytoplasmic regions (43, 44).

The restricted expression of PIR molecules by B and myeloid lineage cells indicated by our immunofluorescence analysis is consistent with previous analyses of PIR-A and PIR-B transcripts (1, 2). Cell surface PIR expression was found to increase as a function of cellular differentiation in both cell lineages, indicating that the PIR family is primarily involved in mature cell function. The levels of PIR-A/ PIR-B expression by splenic B cells were remarkably variable. Examination of the different splenic subpopulations indicated that the expression levels were highest on marginal zone B cells, which appear to be primed cells (45). Correspondingly, the B1 subpopulations of B cells expressed higher PIR levels than did the B2 subpopulation. The suggestion that activated B cells may express higher PIR levels was supported by the observation that LPS stimulation enhanced B cell and myeloid cell expression of the PIR molecules, in keeping with the presence of potential binding sites for the LPS– or IL-6–dependent DNA-binding protein in the promoter region of the Pirb gene (15).

In addition to B cells and myeloid lineage cells, the dendritic cells in the thymus and spleen, defined as MHC class II+ CD11c+ CD8+/− CD4− CD19− Mac-1−, were also found to express the PIR molecules on their surface. This finding suggests that the variable PIR-A molecules and invariant PIR-B molecules could be involved in self/non-self discrimination or antigen presentation. The human Ig-like ILT/LIR/MIR receptors, which share 50–60% sequence similarity with mouse PIR, are also expressed by B cells, monocyte/macrophages, and dendritic cells, but, unlike the murine PIR molecules, these human relatives may also be expressed by NK cells and a subpopulation of T cells (9, 11, 46). Some members of the human ILT/LIR/MIR family have been shown to bind classical or nonclassical MHC class I alleles (10, 46–48). Although the ligand or ligands for the PIR molecules are presently unknown, their pattern of expression on myeloid, lymphoid, and dendritic cells suggests that, like other Ig-like cell surface receptors, they may coligate with other activation/inhibitory systems to modulate inflammatory and immune responses. In this regard, these results suggest that the PIR-A requirement for FcRγc association could result in differential regulation of the PIR-A/PIR-B equilibrium as a function of cellular activation or differentiation pathway.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Peter D. Burrows and Chen-lo Chen for helpful discussion and suggestions, Dr. Suzanne M. Michalek for providing rats, and Marsha Flurry and E. Ann Brookshire for editorial assistance.

This work was supported in part by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants AI42127 (H. Kubagawa), AI39816 (M.D. Cooper) and AI34662 (J.V. Ravetch). M.D. Cooper is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- CY

cychrome

- EC

extracellular domain

- FcαR

Fc receptor for IgA

- FcγR

Fc receptor for IgG

- FcRγc

Fc receptor common γ chain

- ILT

Ig-like transcript

- ITAM

immunoreceptor tyrosine–based activation motif

- ITIM

immunoreceptor tyrosine–based inhibitory motif

- KIR

killer inhibitory receptor

- LIR

leukocyte Ig-like receptor

- MIR

monocyte/macrophage Ig-like receptor

- PIR

paired Ig-like receptor

- SPIT

solid-phase immunoisolation technique

Footnotes

H. Kubagawa and C.-C. Chen contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Kubagawa H, Burrows PD, Cooper MD. A novel pair of immunoglobulin-like receptors expressed by B cells and myeloid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5261–5266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayami K, Fukuta D, Nishikawa Y, Yamashita Y, Inui M, Ohyama Y, Hikida M, Ohmori H, Takai T. Molecular cloning of a novel murine cell-surface glycoprotein homologous to killer cell inhibitory receptors. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7320–7327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maliszewski CR, March CJ, Shoenborn MA, Gimpel S, Shen L. Expression cloning of a human Fc receptor for IgA. J Exp Med. 1990;190:1665–1672. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.6.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colonna M, Samaridis J. Cloning of immunoglobulin-superfamily members associated with HLA-C and HLA-B recognition by human natural killer cells. Science. 1995;268:405–408. doi: 10.1126/science.7716543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagtmann N, Biassoni R, Cantoni C, Verdiani S, Malnati MS, Vitale M, Bottino C, Moretta L, Moretta A, Long EO. Molecular clones of the p58 NK cell receptor reveal immunoglobulin-related molecules with diversity in both the extra- and intracellular domains. Immunity. 1995;2:439–449. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Andrea A, Chang C, Franz-Bacon K, McClanahan T, Phillips JH, Lanier LL. Molecular cloning of NKB1: a natural killer cell receptor for HLA-B allotypes. J Immunol. 1995;155:2306–2310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arm JP, Gurish MF, Reynolds DS, Scott HC, Gartner CS, Austen KF, Katz HR. Molecular cloning of gp49, a cell-surface antigen that is preferentially expressed by mouse mast cell progenitors and is a new member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:15966–15973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang G, Young JR, Tregaskes CA, Sopp P, Howard CJ. Identification of a novel class of mammalian Fcγ receptor. J Immunol. 1995;155:1534–1541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samaridis J, Colonna M. Cloning of novel immunoglobulin superfamily expressed on human myeloid and lymphoid cells: structural evidence for new stimulatory and inhibitory pathways. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:660–665. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cosman D, Fanger N, Borges L, Kubin M, Chin W, Peterson L, Hsu M. A novel immunoglobulin superfamily receptor for cellular and viral MHC class I molecules. Immunity. 1997;7:273–282. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80529-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagtmann N, Rojo S, Eichler E, Mohrenweiser H, Long EO. A new human gene complex encoding the killer cell inhibitory receptors and related monocyte/macrophage receptors. Curr Biol. 1997;7:615–618. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00263-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arm JP, Nwankwo C, Austin KF. Molecular identification of a novel family of human Ig superfamily members that possess immunoreceptor tyrosine–based inhibition motifs and homology to the mouse gp49B1 inhibitory receptor. J Immunol. 1997;159:2342–2349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamashita Y, Fukuta D, Tsuji A, Nagabukuro A, Matsuda Y, Nishikawa Y, Ohyama Y, Ohmori H, Ono M, Takai T. Genomic structures and chromosomal location of p91, a novel murine regulatory receptor family. J Biochem. 1998;123:358–368. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kremer EJ, Kalatzis V, Baker E, Callen DF, Sutherland GR, Maliszewski CR. The gene for the human IgA Fc receptor maps to 19q13. Hum Genet. 1992;89:107–108. doi: 10.1007/BF00207054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alley TL, Cooper MD, Chen M, Kubagawa H. Genomic structure of PIR-B, the inhibitory member of the paired immunoglobulin-like receptor genes in mice. Tissue Antigens. 1998;51:224–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1998.tb03096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bléry M, Kubagawa H, Chen C, Vély F, Cooper MD, Vivier E. The paired Ig-like receptor PIR-B is an inhibitory receptor that recruits the protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2446–2451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maeda A, Kurosaki M, Ono M, Takai T, Kurosaki T. Requirement of SH2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2 for paired immunoglobulin-like receptor B (PIR-B)–mediated inhibitory signal. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1355–1360. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mage MG, McHugh LL, Rothstein TL. Mouse lymphocytes with and without surface immunoglobulin: preparative scale separation in polysytrene tissue culture dishes coated with specifically purified anti-immunoglobulin. J Immunol Methods. 1997;15:47–51. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(77)90016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kearney JF, Radbruch A, Liesegang B, Rajewsky K. A new mouse myeloma cell line that has lost immunoglobulin expression but permits the construction of antibody-secreting hybrid cell line. J Immunol. 1979;123:1548–1550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kozak M. Interpreting cDNA sequences: some insights from studies on translation. Mamm Genome. 1996;7:563–574. doi: 10.1007/s003359900171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurosaki T, Gander I, Ravetch JV. A subunit common to an IgG Fc receptor and the T cell receptor mediates assembly through different interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3837–3841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiyotaki M, Cooper MD, Bertoli LF, Kearney JF, Kubagawa H. Monoclonal anti-Id antibodies react with varying proportions of human B lineage cells. J Immunol. 1987;138:4150–4158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goding JW. Structural studies of murine lymphocyte surface IgD. J Immunol. 1980;124:2082–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monteiro RC, Cooper MD, Kubagawa H. Molecular heterogeneity of Fcα receptors detected by receptor-specific monoclonal antibodies. J Immunol. 1992;148:1764–1770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lassoued K, Nuñez CA, Billips L, Kubagawa H, Monteiro RC, LeBien TW, Cooper MD. Expression of surrogate light chain receptors is restricted to a late stage in pre-B cell differentiation. Cell. 1993;73:73–86. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90161-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blank U, Ra C, Miller L, White K, Metzger H, Kinet J-P. Complete structure and expression in transfected cells of high affinity IgE receptor. Nature. 1989;337:187–189. doi: 10.1038/337187a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ra C, Jouvin M-H, Blank U, Kinet J-P. A macrophage Fcγ receptor and the mast cell receptor for immunoglobulin E share an identical subunit. Nature. 1989;341:752–754. doi: 10.1038/341752a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lanier LL, Yu G, Phillips JH. Co-association of CD3γ with a receptor (CD16) for IgG on human natural killer cells. Nature. 1989;342:803–806. doi: 10.1038/342803a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson P, Caligiuri M, O'Brian C, Manley T, Ritz J, Schlossman S. FcγRIII (CD16) is included in the NK receptor complex expressed by human natural killer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2274–2278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ernst LK, Duchemin A-M, Anderson CL. Association of the high affinity receptor for IgG (FcγRI) with the γ subunit of the IgE receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6023–6027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ravetch JV. Fc receptors: rubor redux. Cell. 1994;78:553–560. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90521-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clevers H, Alarcon B, Wileman T, Terhorst C. The T cell receptor/CD3 complex: a dynamic protein ensemble. Annu Rev Immunol. 1988;6:629–662. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.06.040188.003213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfefferkorn LC, Yeaman GR. Association of IgA-Fc receptors (FcαR) with FcεRIγ2 subunits in U937 cells. J Immunol. 1994;153:3228–3236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morton HC, van den Herik-Oudijk IE, Vossebeld P, Snijders A, Verhoeven AJ, Capel PJA, van de Winkel JGJ. Functional association between the human myeloid IgA Fc receptor (CD89) and FcR γ chain. Molecular basis for CD89/FcR γ chain association. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29781–29787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.50.29781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saito K, Suzuki K, Matsuda H, Okumura K, Ra C. Physical association of Fc receptor γ homodimer with IgA receptor. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;96:1152–1160. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olcese L, Cambiaggi A, Semenzato G, Bottino C, Moretta A, Vivier E. Human killer cell activatory receptors for MHC class I molecules are included in a multimeric complex expressed by natural killer cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:5083–5086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lanier LL, Corliss BC, Wu J, Leong C, Phillips JH. Immunoreceptor DAP12 bearing a tyrosine-based activation motif is involved in activating NK cells. Nature. 1998;391:703–707. doi: 10.1038/35642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mason LH, Willette-Brown J, Anderson SK, Gosselin P, Shores EW, Love PE, Ortaldo JR, McVicar DW. Characterization of an associated 16-kDa tyrosine phosphoprotein required for Ly-49D signal transduction. J Immunol. 1998;160:4148–4152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reth M. Antigen receptor tail clue. Nature. 1989;338:383–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reth M. Antigen receptors on B lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:97–121. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weiss A, Littman DR. Signal transduction by lymphocyte antigen receptors. Cell. 1994;76:263–274. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cambier JC. Antigen and Fc receptor signaling: the awesome power of the immunoreceptor tyrosine–based activation motif (ITAM) J Immunol. 1995;155:3281–3285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maeda A, Kurosaki M, Kurosaki T. Paired immunoglobulin-like receptor (PIR)-A is involved in activating mast cells through its association with Fc receptor γ chain. J Exp Med. 1998;188:991–995. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.5.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamashita Y, Ono M, Takai T. Inhibitory and stimulatory functions of paired Ig-like receptor (PIR) family in RBL-2H3 cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:4042–4047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oliver AM, Martin F, Gartland GL, Carter RH, Kearney JF. Marginal zone B cells exhibit unique activation, proliferative and immunoglobulin secretory responses. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2366–2374. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Colonna M, Navarro F, Bellón T, Llano M, García P, Samaridis J, Angman L, Cella M, López-Botet M. A common inhibitory receptor for major histocompatibility complex class I molecules on human lymphoid and myelomonocytic cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1809–1818. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.11.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borges L, Hsu M, Fanger N, Kubin M, Cosman D. A family of human lymphoid and myeloid Ig-like receptors, some of which binds to MHC class I molecules. J Immunol. 1997;159:5192–5196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Colonna M, Samaridis J, Cella M, Angman L, Allen RL, O'Callaghan CA, Dunbar R, Ogg GS, Cerundolo V, Rolink A. Human myelomonocytic cells express an inhibitory receptor for classical and nonclassical MHC class I molecules. J Immunol. 1998;160:3096–3100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]