Abstract

Thioredoxin (Trx) is a ubiquitous intracellular protein disulfide oxidoreductase with a CXXC active site that can be released by various cell types upon activation. We show here that Trx is chemotactic for monocytes, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and T lymphocytes, both in vitro in the standard micro Boyden chamber migration assay and in vivo in the mouse air pouch model. The potency of the chemotactic action of Trx for all leukocyte populations is in the nanomolar range, comparable with that of known chemokines. However, Trx does not increase intracellular Ca2+ and its activity is not inhibited by pertussis toxin. Thus, the chemotactic action of Trx differs from that of known chemokines in that it is G protein independent. Mutation of the active site cysteines resulted in loss of chemotactic activity, suggesting that the latter is mediated by the enzyme activity of Trx. Trx also accounted for part of the chemotactic activity released by human T lymphotropic virus (HTLV)-1–infected cells, which was inhibited by incubation with anti-Trx antibody. Since Trx production is induced by oxidants, it represents a link between oxidative stress and inflammation that is of particular interest because circulating Trx levels are elevated in inflammatory diseases and HIV infection.

Keywords: chemotaxis, thioredoxin, HTLV-1, migration

Thioredoxin (Trx)1 is a 12-kD, ubiquitous intracellular enzyme with a conserved CXXC active site that forms a disulfide in the oxidized form or a dithiol in the reduced form (1, 2). Trx catalyzes dithiol–disulfide oxidoreductions, and, together with Trx reductase and nicotinamide adenindinucleotide phosphate, is a general protein oxidoreductase and a hydrogen donor for ribonucleotide reductase essential for DNA synthesis (3). In addition, it has intracellular antioxidant activity and, when overexpressed, protects against oxidative stress (4–8).

Trx is secreted by monocytes, lymphocytes, and other normal or neoplastic cells by a leaderless pathway, a property it shares with IL1-β (9–13). Secreted Trx exhibits several cytokine-like activities (8). In particular, Trx secreted by human T lymphotropic virus (HTLV)-1–transformed T cells was originally described as adult T cell leukemia–derived factor and acts as an inducer of the IL-2 receptor (10, 14). Other activities include activation of eosinophil functions, such as cytotoxicity and migration (15, 16), and potentiation of TNF production (17). Clinically, increased Trx levels have been reported in HIV disease (18) and in the synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (19). These data suggested to us that Trx might have chemokine-like activities. We therefore tested the activity of Trx in a standard chemotaxis assay in vitro and in the air pouch model in vivo. The results reported here indicate that Trx is a chemotactic protein with a potency comparable to other known chemokines.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Human recombinant Trx, its C32S/C35S mutant [Trx(SGPS)], and human recombinant glutaredoxin were prepared as previously described (20–22). Goat anti–human Trx neutralizing antibody (23) was from Imco (Sweden). Control antibody (goat antibody against Schistosoma japonicum glutathione S-transferase [GST]) was from Pharmacia. Spirulina Trx was from Sigma Chemical Co.

Miscellaneous Assays.

Human Trx was measured in culture supernatants by ELISA, as previously described (18).

Chemotaxis In Vitro.

Chemotactic activity for human monocytes, PMNs, and T cells was evaluated using 48-well micro Boyden chambers (Neuro Probe, Inc.), as previously described (24, 25). The filters were stained and chemotactic activity was expressed as the average number of cells migrated in five oil immersion fields counted.

Chemotaxis In Vivo.

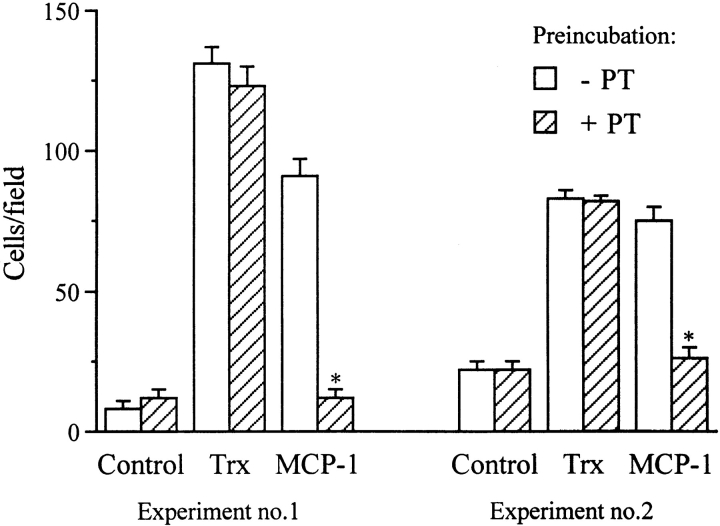

Air pouch formation was induced by injecting 4 ml of air 7 and 3 d before the experiment. Then, 1 μg of Trx was injected into the air pouch in 1 ml of sterile, pyrogen-free saline, containing 0.5% (wt/vol) carboxymethylcellulose (USP grade; Sigma Chemical Co.) to avoid a rapid diffusion of Trx from the site of injection. Control mice were injected with this vehicle. To determine the proportion of different leukocyte subsets, cells from Trx-treated (see Fig. 6, closed symbols) and control mice (see Fig. 6, open symbols) were stained with antibody markers to identify granulocytes, monocyte/macrophages, and lymphocytes. Reagent preparation and staining methods were as previously described (26). Cells from six individual Trx-treated mice (4 h) were analyzed. Six untreated control mice were pooled in order to obtain sufficient cell numbers for analysis. Samples were analyzed on a flow cytometer modified to simultaneously detect 10 fluorochromes (27). Propidium iodide exclusion identified live cells. Granulocytes were identified as GR-1+ (RB6-8C5). Monocyte/ macrophages were identified as GR-1−, CD11b+ (M1/70), F4/80+. Lymphocytes were identified as negative for the above-mentioned markers and confirmed by forward and side scatter characteristics. Animal studies were performed in accordance with Institutional guidelines and approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Figure 6.

Trx-induced leukocyte recruitment in the air pouch in mice. 1 μg of Trx was injected in the air pouch as described in Materials and Methods. Control mice were injected with vehicle only. 4 h later, the cells in the air pouch were recovered, counted, and analyzed by FACS®. ○, mean of seven control mice; •, Trx-treated mice (n = 7).

Intracellular Ca2+ Measurement.

Adherent monocytes or PMNs on coverslips were loaded with FURA-2AM (Sigma Chemical Co.), washed, and incubated at 37°C with the different stimuli. Fluorescence was monitored using an epifluorescence microscope equipped with fluorescence optics and dichroic mirror appropriate for FURA-2 fluorescence. FURA-2 was excited at 350 and 380 nm every second and the emitted fluorescence was filtered between 510 and 530 nm and monitored using a CCD camera (Dage MTI) and a Georgia Instrument Image Analyzer. Regions of interest corresponding to individual cells were identified in each experiment, and average fluorescence was recorded and stored as individual data files. Fluorescence intensity was converted into intracellular free Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i), as previously described (28). Representative experiments are shown as fluorescence tracings of individual cells. Results from several experiments are also summarized as number of responsive cells (when the stimulus-induced increase of [Ca2+]i was twice the SD over the mean of baseline values) or mean Ca2+ increase of responsive cells.

Results

Chemotactic Activity of Trx In Vitro.

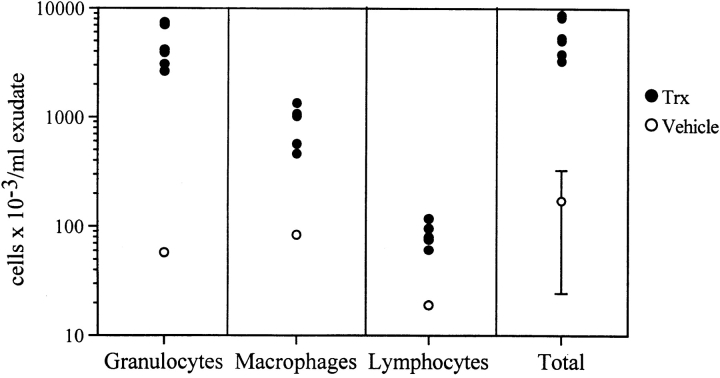

Testing human recombinant Trx for chemotactic activity towards PMNs, monocytes, and T lymphocytes in a standard in vitro chemotaxis assay with micro Boyden chambers (Fig. 1), we found that Trx is chemotactic for all three cell populations. The optimal concentration (0.1–2.5 nM; 1–30 ng/ml) and degree of response are comparable with that of an optimal concentration of a reference chemokine (IL-8 for PMNs, monocyte chemotactic protein [MCP]-1 for monocytes, and RANTES for T cells, respectively). Trx showed the typical bell-shaped dose–response curve reported for all chemokines.

Figure 1.

Chemotactic effect of Trx on human PMNs, monocytes, and T cells. The average number of cells migrated in five oil immersion fields ± SD using different concentrations of human recombinant Trx (•) or boiled (30 min at 100°C) human recombinant Trx (○) are shown. The response to a known chemokine (left panel, IL-8; center panel, MCP-1; right panel, RANTES) is also shown (⋄) as a reference.

To evaluate the possibility that the chemotactic activity of Trx was specific and not due to a contaminant we used different approaches. First, Trx was heat inactivated by boiling, to rule out the possibility that the chemotactic activity might be due to endotoxin, which is heat stable, or to small contaminating peptides. As shown in Fig. 1, boiled Trx was inactive towards all cell populations. Furthermore, a neutralizing anti-Trx antibody, but not a control antibody, neutralized the chemotactic activity of Trx for human monocytes but not the activity of MCP-1 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Chemotactic activity of Trx is inhibited by an anti-Trx antibody. Trx was incubated for 15 min at 37°C with 0.5 μg/ml goat anti– human Trx or a control antibody (anti-GST). Trx was then assayed for chemotactic activity for monocytes at the concentration of 2.5 nM, as described above. Data are mean ± SD of triplicate samples.

To assess whether Trx was indeed chemotactic or if it induced random cell migration, we performed checkerboard experiments using PMNs and monocytes. As shown in Table I, no migration was observed when the same concentration of Trx was added to both the upper and lower chambers, indicating that Trx had a true chemotactic, not chemokinetic, activity.

Table I.

Checkerboard Analysis of the Effect of Trx on Monocyte and PMN Migration

| Monocytes | PMNs | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Below | Above | Above | ||||||||||||

| 0 ng/ml | 3 ng/ml | 30 ng/ml | Below | 0 ng/ml | 3 ng/ml | 30 ng/ml | ||||||||

| 0 ng/ml | 39 ± 4 | ND | ND | 0 ng/ml | 15 ± 4 | ND | ND | |||||||

| 3 ng/ml | 96 ± 5 | 37 ± 4 | 50 ± 4 | 3 ng/ml | 70 ± 4 | 34 ± 4 | 25 ± 4 | |||||||

| 30 ng/ml | 202 ± 9 | 203 ± 6 | 35 ± 2 | 30 ng/ml | 168 ± 9 | 127 ± 6 | 27 ± 4 | |||||||

Different concentrations of Trx were added to the upper and/or the lower compartments of the chemotactic chambers. Results are number of migrated PMNs in five immersion fields and are the mean ± SD of three replicates. ND, not done.

To investigate the role of the protein disulfide oxidoreductase activity, we tested the chemotactic action of Trx from Spirulina algae (which has the same cys-gly-pro-cys [CGPC] active site and enzymatic activity as the mammalian Trx) of a C32S/C35C mutant where the CGPC active site was substituted by a ser-gly-pro-ser [SGPS] sequence, and of human recombinant glutaredoxin. As shown in Fig. 3, Spirulina Trx was chemotactic for PMNs and monocytes at concentrations equivalent to those of human recombinant Trx, whereas glutaredoxin or Trx(SGPS) were inactive.

Figure 3.

Chemotactic activity of Spirulina TRX, Trx(SGPS) mutant, or glutaredoxin on human PMNs and monocytes. The proteins were tested at the indicated concentrations, as described in the legend to Fig. 1. The data show the number of cells migrated in five oil immersion fields using different concentrations of the test protein. Data are mean ± SD of triplicate samples.

Effect of Trx on Intracellular Calcium.

Fig. 4 shows the trace of [Ca2+]i in single monocytes or single PMNs stimulated with MCP-1, IL-8, or Trx. Consistent with previous evidence (28, 29), IL-8 induced a rapid rise in intracellular Ca2+ in PMNs (Fig. 4, C and D) and MCP-1 induced a slower, but nonetheless definitive, increase of Ca2+ in monocytes (Fig. 4, A and B). However, chemotactic concentrations of Trx did not induce any Ca2+ response in either cell population. In several experiments analyzing up to 30 individual cells, we never observed an effect of Trx on intracellular Ca2+ in a concentration range of 1–100 ng/ml (0.083–8.3 nM) (Table II).

Figure 4.

Trx does not increase cytosolic Ca2+ in human monocytes or PMNs. Traces represent levels of [Ca2+]i in single adherent monocytes (A and B) or PMNs (C and D) in response to 30 ng/ml (2.5 nM) Trx (A and C), 25 ng/ml (3 nM) IL-8 (D), or 50 ng/ml (6 nM) MCP-1 (B). Traces are representative of 12–32 cell recordings (7 donors, 3–5 cells per coverslip). Arrows indicate the addition of agents to the bathing medium, which causes a spike in the trace due to exposure to light.

Table II.

Trx Does Not Induce Increase of Ca2+ in Single Monocytes and PMNs

| Responsive cells | Mean Ca2+ increase | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monocytes | % | |||

| Trx 0.83–8.3 nM | 0 | 0 | ||

| MCP-1 3 nM | 82 | 227 ± 81 | ||

| FMLP 100 nM | 100 | 310 ± 41 | ||

| PMNs | ||||

| Trx 0.83–8.3 nM | 0 | 0 | ||

| IL-8 3 nM | 67 | 218 ± 64 | ||

| FMLP 100 nM | 100 | 260 ± 103 |

Data are cumulative of 15–30 cells analyzed. Cells were considered responsive when the stimulus-induced increase of [Ca2+]i was twice the SD over the mean of baseline values. Mean Ca2+ increase is the mean ± SD of values of responsive cells. Data are expressed as percentage above basal [Ca2+]i.

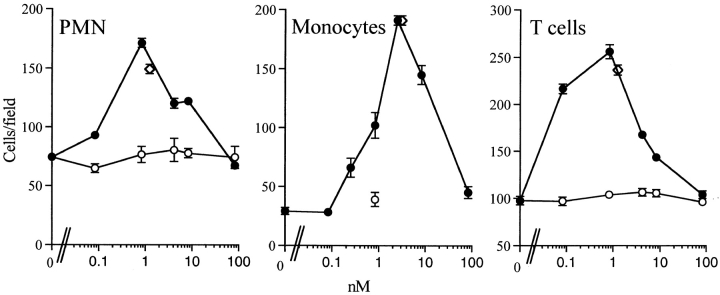

We also studied the effect of the G protein inhibitor, pertussis toxin (PT), on Trx chemotactic activity on monocytes. As shown in Fig. 5, the chemotactic activity of Trx on monocytes was not inhibited by PT, whereas a marked inhibition was observed on MCP-1 activity (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Chemotactic activity of Trx on monocytes is not inhibited by PT. Monocytes were incubated with 1 μg/ml PT for 90 min at 37°C, then washed to remove PT and used for chemotaxis experiments with Trx (30 ng/ml) or MCP-1 (25 ng/ml), as described above. Data from two independent experiments are shown. Data are mean ± SD of triplicate samples. *P < 0.05 versus control by Student's t test.

Chemotactic Activity of Trx In Vivo.

We tested Trx in the murine air pouch model of inflammation (30). 4 h after injection of 1 μg Trx into a pouch (formed by prior subcutaneous injection of air, as described in Materials and Methods), the pouch was washed with medium, and infiltrated cells were counted, stained, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

As shown in Fig. 6, injection of Trx induced a marked infiltration of granulocytes, and, to a lesser extent, monocytes and lymphocytes. Although the absolute response to Trx varied somewhat in different experiments, granulocytes were consistently the most frequent cells in the infiltrate. Infiltration was higher at 4 h than at 24 h (data not shown), consistent with the hypothesis that Trx acts directly as a chemotactic agent and does not cause cell infiltration by inducing other chemokines.

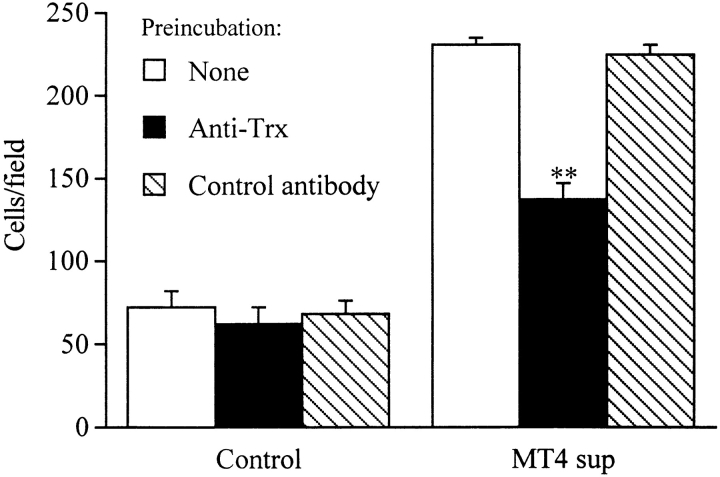

Trx Accounts for the Chemotactic Activity Released by HTLV-1–transformed Cells.

To investigate whether Trx could contribute to the chemotactic activity released by the HTLV-1–transformed MT4 cell line, we studied the effect of an anti-Trx antibody on the chemotactic activity of the MT4 supernatants. As shown in Fig. 7, 50% of the chemotactic activity of the MT4 supernatant was inhibited by an anti–human Trx antibody. The Trx content of the MT4 supernatant, as measured by ELISA, was 6 ng/ml, which is consistent with the potency of Trx as a chemotactic factor.

Figure 7.

Trx is a component of the chemotactic activity for PMNs released by the HTLV-1–transformed cell line MT4. Supernatants from MT4 cells or control media were treated for 15 min at 37°C with goat anti–human Trx (0.5 μg/ml) or a control antibody (anti-GST). Supernatants were then assayed for chemotactic activity on PMNs as described above. **P < 0.05 versus control by Student's t test.

Discussion

Our data show that Trx is a potent chemoattractant for PMNs, monocytes, and T cells. Several lines of evidence suggest that this activity is specific and not due to a contaminant. In particular, chemotactic activity was observed with different Trx preparations, including Trx from algae, it was inactivated by boiling and by an anti-Trx antibody.

Our findings also show that Trx contributes significantly to the chemotactic activity released in HTLV-1–infected cells, that have long been known to secrete Trx (31). In particular, the HTLV-1–transformed MT4 cell line spontaneously releases chemotactic activity for monocytes that is not mediated by TNF, IL-8, or MCP-1 (32). We recently purified a major monocyte chemotactic factor from MT4-conditioned medium that we identified as MIP-1α/LD78 (33) and showed to be active on monocytes but only weakly chemotactic for PMNs (33). We show here that an anti-Trx antibody significantly inhibits the chemotactic activity of MT4 supernatants, an observation that might explain why the known chemokines produced by these cells could not account for all of their chemotactic activity.

As far as the mechanism of the effect of Trx is concerned, we obtained convincing evidences that Trx does not act through a chemokine receptor. First of all, Trx does not induce an increase of intracellular Ca2+, which is observed with all chemokines, whose receptors are coupled to G proteins. Furthermore, chemotactic activity of Trx is not inhibited by PTX. Although chemotactic receptors have been shown to be able to couple with both PTX-sensitive and PTX-insensitive GTP binding proteins (34, 35), only βγ subunits associated with Gαi are responsible for chemotactic receptor-mediated cell migration (36). The finding that Trx chemotactic response is PTX insensitive, along with the lack of effect of Trx on intracellular Ca2+, strongly argue against its direct interaction with a seven-transmembrane domain chemotactic receptor.

In contrast, Trx may initiate signal transduction for chemotaxis by oxidizing and cross-linking appropriate cell surface molecules. Trx is mainly known as a protein disulfide–reducing enzyme; however, it can also act as protein disulfide isomerase in the formation of disulfides during protein folding (1), particularly when in an oxidative environment (37). Thus it is possible that, in an extracellular environment, Trx acts by oxidizing thiols of one or more membrane proteins or catalyzing isomerization reactions. However, since Trx's chemotactic activity is G protein independent, this putative oxidized receptor is likely to differ from any of the known chemokine receptors. In fact, the Trx target could behave like a “sensor”, in a fashion similar to the hemoprotein, which acts as the oxygen sensor in the induction of erythropoietin (38).

Several lines of evidence suggest that the chemotactic activity of Trx is due to its enzymatic action on cell surface protein substrates. First of all, a C32S/C35S mutant of Trx where the cysteines of CXXC active site have been mutated, and that has lost enzyme activity (22), was not chemotactic. Furthermore, glutaredoxin, which differs from Trx in substrate specificity, has no chemotactic activity. In fact, although Trx catalyzes the oxidation/reduction of a wide range of inter- or intra-protein disulfides, the preferred substrates of glutaredoxin are mixed disulfides between proteins and glutathione, and the substrate specificity for disulfides is very different (1, 2, 21). A further support to this hypothesis is the chemotactic activity of Trx from Spirulina. Since algal Trx has only little (∼20%) similarity with human Trx (39), but has the same conserved CGPC active site human Trx, we think it is more likely that Trx may act through its enzymatic activity rather than by binding to a membrane receptor. Consistent with this, various investigators have been unable to identify specific binding sites for Trx on the cell membrane of various cell types (40–43).

Our findings suggest two different hypotheses concerning the pathogenic role of Trx in infection and inflammation. First, the local release of Trx is likely to be important, in concert with other chemokines, in recruiting cells during infection and inflammation. Consistent with this hypothesis, Trx is secreted by IFN-γ– or endotoxin-stimulated macrophages or activated T lymphocytes (12, 44) and has been measured locally in arthritic patients (19). Trx is also an acute-phase protein in that its production by the liver is increased in rats injected with LPS (45). In addition, Trx may also be a major chemoattractant in diseases associated with oxidative stress, such as ischemia/reperfusion, since Trx production is induced by oxidants (46) and Trx is elevated locally in cerebral ischemia or brain injury (47, 48) and open-heart surgery (23). Thus, according to this hypothesis, Trx might function as a signal of oxidative stress that amplifies the cellular response at a site of inflammation.

A second hypothesis on the significance of Trx in disease stems from the observation that Trx levels were found to be elevated (>30 ng/ml plasma) in a proportion of HIV- infected subjects with CD4 T cell counts <200/μl blood (18). Nearly all of the high-Trx subjects died within 18 mo of the Trx measurement, although none had active opportunistic infections or other signs of debilitating disease at the time of measurement. Deaths in an otherwise similar group of HIV-infected subjects with normal Trx levels were minimal during the same period (Nakamura, H., S. de Rosa, M. Roederer, J. Yodoi, A. Holmgren, P. Ghezzi, L.A. Herzenberg, and L.A. Herzenberg, manuscript in preparation).

This survival difference may be directly traceable to the chemoattractant activity of the Trx present in circulation. Intravenous injection of IL-8 has been shown to inhibit PMN accumulation in response to local injection of IL-8 (49). Furthermore, leukocyte migration is impaired in transgenic mice overexpressing human IL-8 or MCP-1 in circulation (50, 51). High levels of circulating Trx may similarly decrease the ability of leukocytes to migrate efficiently to a site of infection, either by counteracting the gradient of local chemoattractants or downregulating the chemokine receptors by desensitization (or both). Consistent with this, PMNs and monocytes from AIDS patients have been shown to be deficient in their ability to migrate (52, 53). Thus, by potentially interfering with chemotaxis, elevated serum Trx levels in HIV patients could contribute to augmented susceptibility to bacterial or viral infections and hence constitute a serious threat to survival in the ensuing months.

The possibility that a chemoattractant acts through its enzymatic activity, rather than through classical receptor binding, opens the way to new strategies aimed at inhibiting its action, using enzyme inhibitors rather than receptor antagonists or antibodies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Guido Poli (DIBIT, San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy) for kindly providing the MT4 supernatant.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- GST

glutathione-S-transferase

- HTLV

human T lymphotropic virus

- MCP

monocyte chemotactic protein

- PT

pertussis toxin

- Trx

thioredoxin

Footnotes

This work was partially supported by the contract “Programma Nazionale di Ricerca e Formazione sui Farmaci (Seconda Fase), Tema I”, granted by the Italian Ministry of University and Scientific and Technological Research; by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant CA42509 (to Leonard A. Herzenberg); and by the Swedish Cancer Society (A. Holmgren). O.M.Z. Howard and H.-F. Dong are funded in part by NCI, NIH contract NO1-CO-56000.

References

- 1.Holmgren A. Thioredoxin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:237–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holmgren A. Thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:13963–13966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmgren A, Bjornstedt M. Thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. Methods Enzymol. 1995;252:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)52023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakamura, H., M. Matsuda, K. Furuke, Y. Kitaoka, S. Iwata, K. Toda, T. Inamoto, Y. Yamaoka, K. Ozawa, and J. Yo. 1994. Adult T cell leukemia-derived factor/human thioredoxin protects endothelial F-2 cell injury caused by activated neutrophils or hydrogen peroxide. Immunol. Lett. 42:75–80. (See published erratum 42:213.) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Sasada T, Iwata S, Sato N, Kitaoka Y, Hirota K, Nakamura K, Nishiyama A, Taniguchi Y, Takabayashi A, Yodoi J. Redox control of resistance to cis-diamminedichloroplatinum (II) (CDDP): protective effect of human thioredoxin against CDDP-induced cytotoxicity. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2268–2276. doi: 10.1172/JCI118668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yodoi J, Tursz T. ADF, a growth-promoting factor derived from adult T cell leukemia and homologous to thioredoxin: involvement in lymphocyte immortalization by HTLV-I and EBV. Adv Cancer Res. 1991;57:381–411. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)61004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yodoi J, Uchiyama T. Diseases associated with HTLV-I: virus, IL-2 receptor dysregulation and redox regulation. Immunol Today. 1992;13:405–411. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90091-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamura H, Nakamura K, Yodoi J. Redox regulation of cellular activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:351–369. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ericson ML, Horling J, Wendel-Hansen V, Holmgren A, Rosen A. Secretion of thioredoxin after in vitro activation of human B cells. Lymphokine Cytokine Res. 1992;11:201–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tagaya, Y., Y. Maeda, A. Mitsui, N. Kondo, H. Matsui, J. Hamuro, N. Brown, K. Arai, T. Yokota, and H. Wakasugi. 1989. ATL-derived factor (ADF), an IL-2 receptor/Tac inducer homologous to thioredoxin; possible involvement of dithiol-reduction in the IL-2 receptor induction. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 8:757–764. (See published erratum 13:2244.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Wakasugi N, Tagaya Y, Wakasugi H, Mitsui A, Maeda M, Yodoi J, Tursz T. Adult T-cell leukemia-derived factor/thioredoxin, predicted by both human T-lymphotrophic virus type-1 and Epstein-Barr virus-transformed lymphocytes, acts as an autocrine growth factor and synergizes with interleukin 1 and interleukin 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8282–8286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubartelli A, Bajetto A, Allavena G, Wollman E, Sitia R. Secretion of thioredoxin by normal and neoplastic cells through a leaderless secretory pathway. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:24161–24164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubartelli A, Bonifaci N, Sitia R. High rates of thioredoxin secretion correlate with growth arrest in hepatoma cells. Cancer Res. 1995;55:675–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teshigawara K, Maeda M, Nishino K, Nikaido T, Uchiyama T, Tsudo M, Wano Y, Yodoi J. Adult T leukemia cells produce a lymphokine that augments interleukin 2 receptor expression. J Mol Cell Immunol. 1985;2:17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hori K, Hirashima M, Ueno M, Matsuda M, Waga S, Tsurufuji S, Yodoi J. Regulation of eosinophil migration by adult T cell leukemia-derived factor. J Immunol. 1993;151:5624–5630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silberstein DS, McDonough S, Minkoff MS, Balcewicz-Sablinsha MK. Human eosinophil cytotoxicity enhancing factor: eosinophil-stimulating and dithiol reductase activities of biosynthetic (recombinant) species with COOH-terminal deletions. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9138–9142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schenk H, Vogt M, Dröge W, Schulze-Osthoff K. Thioredoxin as a potent costimulus of cytokine expression. J Immunol. 1996;156:765–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura H, De Rosa S, Roederer M, Anderson MT, Dubs JG, Yodoi J, Holmgren A, Herzenberg LA. Elevation of plasma thioredoxin levels in HIV-infected individuals. Int Immunol. 1996;8:603–611. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.4.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maurice MM, Nakamura H, van der Voort EA, van Vliet AI, Staal FJ, Tak PP, Breedveld FC, Verweij CL. Evidence for the role of an altered redox state in hyporesponsiveness of synovial T cells in rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol. 1997;158:1458–1465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ren X, Bjornstedt M, Shen B, Ericson ML, Holmgren A. Mutagenesis of structural half-cystine residues in human thioredoxin and effects on the regulation of activity by selenodiglutathione. Biochemistry. 1993;32:9701–9708. doi: 10.1021/bi00088a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holmgren A, Aslund F. Glutaredoxin. Methods Enzymol. 1995;252:283–292. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)52031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallegos A, Gasdaska JR, Taylor CW, Paine-Murrieta GD, Goodman D, Gasdaska PY, Berggren M, Briehl MM, Powis G. Transfection with human thioredoxin increases cell proliferation and a dominant-negative mutant thioredoxin reverses the transformed phenotype of human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5765–5770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakamura H, Vaage J, Valen G, Padilla CA, Bjornstedt M, Holmgren A. Measurements of plasma glutaredoxin and thioredoxin in healthy volunteers and during open-heart surgery. Free Radical Biol Med. 1998;24:1176–1186. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00429-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Falk W, Goodwin RH, Jr, Leonard EJ. A 48-well micro chemotaxis assembly for rapid and accurate measurement of leukocyte migration. J Immunol Methods. 1980;33:239–247. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(80)90211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chertov O, Michiel DF, Xu L, Wang JM, Tani K, Murphy WJ, Longo DL, Taub DD, Oppenheim JJ. Identification of defensin-1, defensin-2, and CAP37/ azurocidin as T-cell chemoattractant proteins released from interleukin-8-stimulated neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2935–2940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson MT, Baumgarth N, Haugland RP, Gerstein RM, Tjioe T, Herzenberg LA. Pairs of violet-light-excited fluorochromes for flow cytometric analysis. Cytometry. 1998;33:435–444. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19981201)33:4<435::aid-cyto7>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roederer M, De Rosa S, Gerstein R, Anderson M, Bigos M, Stovel R, Nozaki T, Parks D, Herzenberg L. 8-color, 10-parameter flow cytometry to elucidate complex leukocyte heterogeneity. Cytometry. 1997;29:328–339. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19971201)29:4<328::aid-cyto10>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bizzarri C, Bertini R, Bossu P, Sozzani S, Mantovani A, Van Damme J, Tagliabue A, Boraschi D. Single-cell analysis of macrophage chemotactic protein-1-regulated cytosolic Ca2+increase in human adherent monocytes. Blood. 1995;86:2388–2394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brandolini L, Bertini R, Bizzarri C, Sergi R, Caselli G, Zhou D, Locati M, Sozzani S. IL-1 beta primes IL-8-activated human neutrophils for elastase release, phospholipase D activity, and calcium flux. J Leukocyte Biol. 1996;59:427–434. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romano M, Faggioni R, Sironi M, Sacco S, Echtenacher B, Di Santo E, Salmona M, Ghezzi P. Carrageenan-induced acute inflammation in the mouse air pouch synovial model. Role of tumor necrosis factor. Mediat Inflamm. 1997;6:1–7. doi: 10.1080/09629359791901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yodoi J, Tursz T. ADF, a growth-promoting factor derived from adult T cell leukemia and homologous to thioredoxin: involvement in lymphocyte immortalization by HTLV-I and EBV. Adv Cancer Res. 1991;57:381–411. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)61004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saggioro D, Wang JM, Sironi M, Luini W, Mantovani A, Chieco-Bianchi L. Chemoattractant(s) in culture supernatants of HTLV-I-infected T-cell lines. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1991;7:571–577. doi: 10.1089/aid.1991.7.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bertini R, Luini W, Sozzani S, Bottazzi B, Ruggiero P, Boraschi D, Saggioro D, Chieco-Bianchi L, Proost P, van Damme J, et al. Identification of MIP-1 alpha/ LD78 as a monocyte chemoattractant released by the HTLV-I-transformed cell line MT4. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1995;11:155–160. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu D, LaRosa GJ, Simon MI. G protein-coupled signal transduction pathways for interleukin-8. Science. 1993;261:101–103. doi: 10.1126/science.8316840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuang Y, Wu Y, Jiang H, Wu D. Selective G protein coupling by C-C chemokine receptors. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3975–3978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.3975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arai H, Tsou CL, Charo IF. Chemotaxis in a lymphocyte cell line transfected with C-C chemokine receptor 2B: evidence that directed migration is mediated by βγ dimers released by activation of Gαi-coupled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14495–14499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Debarbieux L, Beckwith J. The reductive enzyme thioredoxin 1 acts as an oxidant when it is exported to the Escherichia coliperiplasm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10751–10756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldberg MA, Dunning SP, Bunn HE. Regulation of erythropoietin gene: evidence the oxygen sensor is a heme protein. Science. 1988;242:1412–1415. doi: 10.1126/science.2849206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Decottignies P, Schmitter JM, Jacquot JP, Dutka S, Picaud A, Gadal P. Purification, characterization, and complete amino acid sequence of a thioredoxin from a green alga, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. . Arch Biochem Biophys. 1990;280:112–121. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90525-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wollman EE, Kahan A, Fradelizi D. Detection of membrane associated thioredoxin on human cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;230:602–606. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.6015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gasdaska JR, Berggren M, Powis G. Cell growth stimulation by the redox protein thioredoxin occurs by a novel helper mechanism. Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6:1643–1650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Biguet C, Wakasugi N, Mishal Z, Holmgren A, Chouaib S, Tursz T, Wakasugi H. Thioredoxin increases the proliferation of human B-cell lines through a protein kinase C-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28865–28870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sahaf B, Soderberg A, Spyrou G, Barral AM, Pekkari K, Holmgren A, Rosen A. Thioredoxin expression and localization in human cell lines: detection of full-length and truncated species. Exp Cell Res. 1997;236:181–192. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Endoh M, Kunishita T, Tabira T. Thioredoxin from activated macrophages as a trophic factor for central cholinergic neurons in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;192:760–765. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buetler TM. Identification of glutathione S-transferase isozymes and gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase as negative acute-phase proteins in rat liver. Hepatology. 1998;28:1551–1560. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sachi Y, Hirota K, Masutani H, Toda K, Okamoto T, Takigawa M, Yodoi J. Induction of ADF/TRX by oxidative stress in keratinocytes and lymphoid cells. Immunol Lett. 1995;44:189–193. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(95)00213-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tomimoto H, Akiguchi I, Wakita H, Kimura J, Hori K, Yodoi J. Astroglial expression of ATL-derived factor, a human thioredoxin homologue, in the gerbil brain after transient global ischemia. Brain Res. 1993;625:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90130-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lippoldt A, Padilla CA, Gerst H, Andbjer B, Richter E, Holmgren A, Fuxe K. Localization of thioredoxin in the rat brain and functional implications. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6747–6756. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06747.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hechtman DH, Cybulsky MI, Fuchs HJ, Baker JB, Gimbrone MA., Jr Intravascular IL-8. Inhibitor of polymorphonuclear leukocyte accumulation at sites of acute inflammation. J Immunol. 1991;147:883–892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simonet WS, Hughes TM, Nguyen HQ, Trebasky LD, Danilenko DM, Medlock ES. Long-term impaired neutrophil migration in mice overexpressing human interleukin-8. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1310–1319. doi: 10.1172/JCI117450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rutledge BJ, Rayburn H, Rosenberg R, North RJ, Gladue RP, Corless CL, Rollins BJ. High level monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in transgenic mice increases their susceptibility to intracellular pathogens. J Immunol. 1995;155:4838–4843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lazzarin A, Uberti C, Foppa, Galli M, Mantovani A, Poli G, Franzetti F, Novati R. Impairment of polymorphonuclear leucocyte function in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and with lymphadenopathy syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 1986;65:105–111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Poli G, Bottazzi B, Acero R, Bersani L, Rossi V, Introna M, Lazzarin A, Galli M, Mantovani A. Monocyte function in intravenous drug abusers with lymphadenopathy syndrome and in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: selective impairment of chemotaxis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1985;62:136–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]