Abstract

The recognition of antigen by membrane immunoglobulin M (mIgM) results in a complex series of signaling events in the cytoplasm leading to gene activation. Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK), a member of the Tec family of tyrosine kinases, is essential for the full repertoire of IgM signals to be transduced. We examined the ability of BTK to regulate the nuclear factor (NF)-κB/Rel family of transcription factors, as the activation of these factors is required for a B cell response to mIgM. We found greatly diminished IgM- but not CD40-mediated NF-κB/Rel nuclear translocation and DNA binding in B cells from X-linked immunodeficient (xid) mice that harbor an R28C mutation in btk, a mutation that produces a functionally inactive kinase. The defect was due, in part, to a failure to fully degrade the inhibitory protein of NF-κB, IκBα. Using a BTK-deficient variant of DT40 chicken B cells, we found that expression of wild-type or gain-of-function mutant BTK, but not the R28C mutant, reconstituted NF-κB activity. Thus, BTK is essential for activation of NF-κB via the B cell receptor.

Keywords: X-linked immunodeficiency, CD40, B cell receptor, B cell activation, transcription factor

Introduction

Mutation of the gene encoding Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) causes X-linked immunodeficiency (xid) in mice and X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA) in humans 1 2 2a. XLA patients exhibit a block in early B cell maturation that prevents development of antibody-producing cells 3. btk mutation in mice reduces peripheral B cells to <50% of wild-type levels and renders them unresponsive to T-independent type II antigens without preventing responses to T-independent type I or T-dependent antigens 4. Xid mice also have low serum IgM and IgG3 and no peritoneal CD5+ B-1a cells 4. Different mutations spanning the human btk gene result in XLA, whereas in mice, a single missense mutation of BTK, R28C, results in x-linked immunodeficiency. This led to speculation that the severity of the human phenotype was due to the location of the mutation in the btk gene. Further experimentation showed that disruption of the btk gene in mice also produced the xid phenotype 5 6. Conversely, patients with the single basepair mutation producing the R28C amino acid replacement retained the severity of the human disease 7. Together, these data showed that the xid mutation renders mice deficient in essential BTK functions and that the B cell requirement for BTK differs between the murine and human species.

Expression of BTK is limited to B, mast, and myeloid cells. BTK, like other members of the Tec family of cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases, is similar to the Src family kinases in that it contains Src homology (SH)1, SH2, and SH3 domains. However, Tec family members lack the NH2-terminal myristylation site and COOH-terminal negative regulatory site found in the Src family kinases. In addition, they have a unique region, termed the Tec homology domain, and an NH2-terminal pleckstrin homology (PH) domain (for review see reference 8). BTK is expressed continuously from the late pro-B stage up to the plasma cell stage 9. Loss of BTK function disrupts signaling through the IL-5R, CD38, IL-10R, FcεRI, and B cell receptor for antigen (BCR) pathways 10 11 12 13 14 15. In mature B cells, BTK is tyrosine phosphorylated upon membrane IgM receptor cross-linking 16 17. In fibroblasts, ectopic expression of Lyn leads to transphosphorylation of BTK at Tyr-551 18. The kinase responsible for this phosphorylation in B cells has not been identified. Phosphorylation at Tyr-551 leads to BTK autophosphorylation at Tyr-223, membrane localization, and increased kinase activity 19. The PH domain of BTK has a high affinity for phosphoinositide phospholipids, in particular phosphatidylinositol (PI)-3,4,5-triphosphate (PtdIns-3,4,5-P3) 20. PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 binding is necessary for the activation-dependent membrane localization of BTK 18 21. In addition, several proteins have been reported to bind BTK: transcription factor II-I (TFII-I [BAP-135]), protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP), Ewing's sarcoma protein (EWS), cbl, SAM68 (Src-associated in mitosis 68 kD), SLP-65 (SH2 domain–containing linker protein 65 kD; BLNK [B cell linker protein]), and vav 22 23 24 25 26 27. BTK is critical for the activation of phospholipase (PLC)-γ2, leading to intracellular calcium release, extracellular calcium influx, and PKC activation 28 29 30.

Wild-type B cells enter cell cycle upon antigen cross-linking of the BCR, whereas xid, or btk −/−, cells undergo apoptosis. Although IgM cross-linking of xid B cells does not lead to proliferation, some IgM-mediated signals are successfully transmitted, resulting in upregulation of MHC class II and tyrosine phosphorylation of multiple proteins 29 31. Further downstream, uncharacterized BTK-dependent pathways lead to Bcl-xL 32 and cyclin induction 33. This suggested that IgM-mediated transcription factor activation is compromised in xid B cells.

In primary splenic B cells, IgM cross-linking or CD40 ligation leads to nuclear translocation and DNA binding of the NF-κB/Rel family of transcription factors 34 35 36. Phenotypic analysis of mice deficient in individual NF-κB/Rel family members has demonstrated the essential role of these transcription factors in CD40, LPS, and IgM receptor pathways leading to B cell proliferation. In particular, B cells from mice deficient in NF-κB members c-rel or p65 have decreased responses to antigen cross-linking 37 38. C-rel −/− B cells also failed to respond to CD40 ligation (not determined in p65 −/− mice). Recently, an examination of B cells in mice expressing a transdominant form of IκBα revealed xid-like defects, including a lack of proliferation in response to anti-IgM 39. The CD40 transduction of NF-κB activation has been well characterized 40 41 42. There is less information about the molecular signaling events connecting the BCR to NF-κB activation.

Recently, several of the events proximal to NF-κB activation have been elucidated (for review see reference 43). In wild-type resting cells, NF-κB/Rel factors are sequestered in the cytoplasm by members of the inhibitory κB (IκB) family of proteins. Activation of IκB kinases results in serine/threonine phosphorylation, subsequent ubiquitination, and the proteolytic degradation of IκB. The nuclear localization sequence of the NF-κB/Rel proteins is then exposed, and the factors localize to the nucleus.

As BTK and NF-κB are both essential for normal B cell function, we asked whether BTK might be involved in NF-κB activation. We compared wild-type and xid murine B cells with respect to BCR-mediated induction of NF-κB DNA binding, nuclear translocation, transcript induction, and IκB degradation. Reconstitution experiments in the BTK-deficient variant of the chicken B cell line DT40 allowed us to determine the effect of wild-type and mutant BTK proteins on NF-κB activation.

Materials and Methods

Preparation and Activation of Splenic Murine B Cells.

A BALB/cAnN-xid colony was generated from original breeding pairs derived from BALB/cAnN-xid mice provided by Dr. C. Hansen (National Institutes of Health Genetic Resource Center, Bethesda, MD) and maintained at Tufts University. BALB/cByJ mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Splenic B cells were isolated from >8-wk-old mice by complement-mediated T cell lysis as previously described 44. This procedure was modified by addition of a Lympholyte-M Ficoll (Cedarlane) gradient step after treatment with Tris-ammonium chloride–BSA to remove residual RBCs in the lymphocyte populations. Cell populations were 90–99% splenic B cells, as tested by FACS® analysis for CD45 (B220) expression.

Cells were pelleted and resuspended for culture at 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies) containing 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.0, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin sulfate, and 50 mM 2-ME (called complete medium below). In all assays, cells were left untreated or treated for 4 h with 10 μg/ml F(ab′)2 goat anti–mouse IgM, μ chain specific (Jackson ImmunoResearch), hybridoma supernatant CD8/CD40L 45 protein at a final dilution of 1:2, or PMA (Sigma-Aldrich) and ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) at a final concentration of 30 nM and 1 mM, respectively. (Preliminary time course experiments demonstrated maximal translocation of nuclear c-rel after stimulation for 4 h.) In some experiments, cells were assayed for early signs of apoptosis after B cell stimulation for 4 h, as described 46.

Cell Lines and Constructs.

DT40 wild-type and BTK-deficient chicken B cell lines were generated by Dr. T. Kurosaki (Kansai University, Kansai, Japan) and provided by Dr. J. Ravetch (The Rockefeller University, New York, NY). The cells were maintained in culture at a density of <5 × 105 cells/ml in complete medium, with the addition of 1% heat-inactivated chicken serum. These cells were stimulated (in the absence of chicken serum) with 10 μg/ml mouse monoclonal anti–chicken IgM, M4 (generated by Dr. M. Cooper, University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL and obtained from Dr. E. Clark, Washington University, St. Louis, MO), or 30 nM PMA (Sigma-Aldrich) in combination with 1 μM ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). WEHI231 and T220 cell lines were cultured in complete medium.

The pGD-BTK construct was provided by Dr. G. Cheng (University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA). R28C (xid) and E41K (gain-of-function) basepair mutations were generated in the murine btk gene by standard PCR mutagenesis and checked by sequence analysis at the Tufts University Sequencing Facility. The wild-type and mutant btk cDNAs were excised from the pGD vector by XhoI and NotI digestion and inserted into EcoRI-linearized pBabeApuro vector, which was donated by Dr. T. Kurosaki 47.

The luciferase reporter constructs, containing three NF-κB DNA binding sites or lacking these sites, were provided by Dr. S. Ghosh (Yale University, New Haven, CT). A pRLTK construct (Promega) served as an internal control in the luciferase experiments.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays.

4 × 107 cells were stimulated, as described above, and nuclear extracts were prepared as previously described 48. The κB site used as a probe in this assay is a 70-bp fragment excised from a plasmid containing the H2K MHC gene promoter 49. The fragment was labeled with γ-[32P]dATP (Dupont) by T4 polynucleotide kinase. 5 μg of nuclear protein or the equivalent of 4 × 106 cells was incubated with 10,000 cpm of the NF-κB probe. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed as described 48.

[35S]Methionine/Cysteine Pulse–Chase Experiments.

For each treatment, 2 × 107 splenic B cells were cultured in 2 ml of cysteine- and methionine-free RPMI (BioWhittaker), containing 10% dialyzed FCS (JRH Bioscience), for 2 h at 37°C. These cysteine- and methionine-deprived cells were then incubated for an additional 2 h with 60 μCi/ml 35S-labeled cysteine and methionine at 37°C. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in 2 ml of 10% FCS, complete medium and cultured for 0 or 1 h at 37°C, with or without F(ab′)2 goat anti–mouse IgM (described above). After treatment, the cells were lysed in 1 ml TNTE buffer 50 for a minimum of 0.5 h. Nuclear and membrane debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 16,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant lysate was precleared by incubation with Sepharose A beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and 28 μg of whole rabbit IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) for 45 min at 4°C. These precleared lysates were incubated overnight with Sepharose A beads and 60 μg of anti-IκBα antibody (SC-371; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The IκBα-bound beads were washed four times with lysis buffer at 4°C. 100 μl of l% SDS-TNTE lysis buffer was added to the washed beads, and samples were boiled for 5 min. 900 μl of TNTE lysis buffer was added, the beads were pelleted, and the IκBα-containing lysate was transferred to a new tube. To reduce the background, the IκBα immunoprecipitation was repeated. The beads were washed four times with lysis buffer, and 50 μl of 2× Laemmli buffer was added to the pelleted beads. The samples were then electrophoresed on 10% SDS-PAGE for 3 h at 30 mA. The gel was fixed for 10 min with a 10% acetic acid/50% methanol solution. After multiple washes in water, the gel was placed in a 1 M salicylic acid/1% glycerol solution for 30 min, rinsed quickly with water, and dried at 50°C for 2 h. The dried gel was exposed in a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) overnight. Densitometry analysis was carried out using the Bio-Rad Imaging Densitometer and Multi-Analysis Software (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Western Blot Analysis.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared from wild-type and xid B cells as previously described 48. During this lysis procedure, the buffer A supernatant was saved, as it contained the cytoplasmic proteins. Whole cell extracts were prepared by lysis of 107 cells in 1× Laemmli buffer. Samples from equivalent micrograms or cell numbers were electrophoresed on 10% SDS-PAGE for 3 h at 30 mA. Proteins were transferred to immobilon P membranes (Millipore). The membranes were blocked with 5% milk/0.1%BSA–DPBS for 45 min at room temperature. Membranes that were to be stained with anti-BTK serum were blocked with 5% BSA in TBST (containing 0.1% BSA and 0.1% Tween). The membranes were incubated for 1.5 h at room temperature with anti–c-rel at 1:500 dilution (SC-071; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-IκBα at 1:1,000 dilution (SC-371; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti–SP-1 at 1:500 dilution (SC-420; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti–β-actin at 1:2,500 dilution (Sigma-Aldrich), or rabbit anti–murine BTK (amino acids 182–191) at 1:1,000 dilution. After multiple washes, the membranes were incubated with secondary horseradish peroxidase–goat anti–rabbit or anti–mouse IgG (Boehringer Mannheim) for 45 min at room temperature and then exposed to ECL chemiluminescence reagent (Dupont).

DT40 Transfection and Dual Luciferase Assays.

A total of 30 or 50 μg of DNA was used to transfect 107 DT40 cells. Transfection was conducted by electroporation (330 V, 250 μF). The cells were cultured for 16–24 h at 40°C and stimulated as described above. The dual luciferase assay was performed using the Promega dual-luciferase assay kit as described in the manufacturer's instruction manual.

Northern Blot Analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from 3 × 107 splenic B cells per treatment using the guanidium thiocyanate method. In brief, 10 μg of RNA was electrophoresed on a 1% agarose, 2.2 M formaldehyde gel and transferred to nitrocellulose overnight, and the blot was baked for 2 h at 80°C. The blot was hybridized with a α-[32P]dCTP end-labeled c-rel cDNA, washed, and exposed to film for 1 wk at −70°C 49. This 1.8-kb c-rel fragment was isolated from pEVRF2-c-rel using BAMH1 and HindIII.

Reverse Transcriptase PCR Analysis.

cDNA was generated from 1 μg of total RNA (isolated as described above) using the Superscript Preamplification System (oligo dT was used as the primer; GIBCO BRL). 1 μl of cDNA was used in a standard PCR reaction using primers specific for c-rel (5′ primer: GCT CCA AAT ACT GCA GAA TTA AGG; 3′ primer: CGT GCA GAT ATC TAA AAT CCA TAG) or GαS (5′ primer: AAT GAA ACC ATT GTG GCC GCC ATG AGC; 3′ primer: GAA GAC ACG GCG GAT GTT CTC AGT GTC). The conditions for the PCR reaction were 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 54°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, and 1 cycle of 72°C for 15 min.

Results

Reduced DNA Binding and Nuclear Translocation of NF-κB/Rel Transcription Factors in IgM- but not CD40-stimulated XID B Cells.

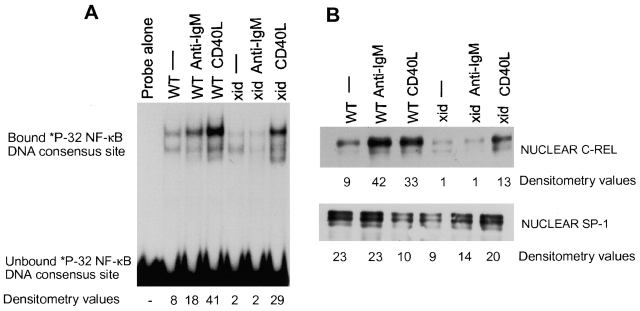

EMSAs showed that xid, btk-mutated B cells did not induce DNA binding of NF-κB/Rel transcription factors after treatment for 4 h with F(ab′)2 anti-IgM (Fig. 1 A). Stimulation with anti-IgM increased tyrosine phosphorylation levels in both wild-type and xid B cells, indicating that the xid BCR transduced some signals (data not shown). We failed to find any differences in mitochondrial membrane potential (early sign of apoptosis) between wild-type and xid B cells at this time. This suggests that the failure to activate NF-κB is unlikely to be a consequence of the apoptosis of xid B cells. In contrast to IgM cross-linking, CD40 ligation led to an increase of DNA binding activity in both wild-type and xid B cells (Fig. 1 A).

Figure 1.

NF-κB/Rel DNA binding and translocation is decreased in anti-IgM–activated, btk-mutated, xid B cells. (A) Splenic B cells from wild-type and xid mice were cultured for 4 h in medium, F(ab′)2 anti-IgM (10 μg/ml), or CD40 ligand (1:2 dilution), cells were harvested, nuclear extracts prepared, and EMSAs performed as described in Materials and Methods. This figure represents one of three experiments. Densitometry was performed on the upper band of the gel shift. Addition of a cold competitor (100-fold excess) demonstrated the specificity of NF-κB binding (data not shown), as shown previously 49. (B) Western analysis of nuclear c-rel expression (top panel) was conducted using 20 μg of extract prepared from wild-type or xid splenic B cells treated as described in A. Transcription factor SP-1 served as a nuclear loading control (bottom panel). Densitometry was performed. After normalization to the loading control, it was determined that anti-IgM treatment induced nuclear c-rel 4.8-fold in wild-type and 0.75-fold in xid B cells. This figure represents one of five experiments.

Next, we asked if the lack of NF-κB DNA binding activity in IgM-activated xid B cells was due to reduced nuclear NF-κB protein. We chose to analyze c-rel, as it is required for B cell proliferation in response to anti-IgM 37. Western blot analysis showed that IgM- but not CD40-induced levels of nuclear c-rel were drastically reduced in xid B cells (Fig. 1 B, top panel). Basal nuclear c-rel in xid B cells was consistently less than that seen in wild-type cells. Although CD40-mediated NF-κB/Rel DNA binding and c-rel nuclear translocation in xid B cells was slightly lower than that in wild-type B cells, the fold inductions were similar (Fig. 1A and Fig. B). These initial studies suggested that BTK plays some role, direct or indirect, in NF-κB activation.

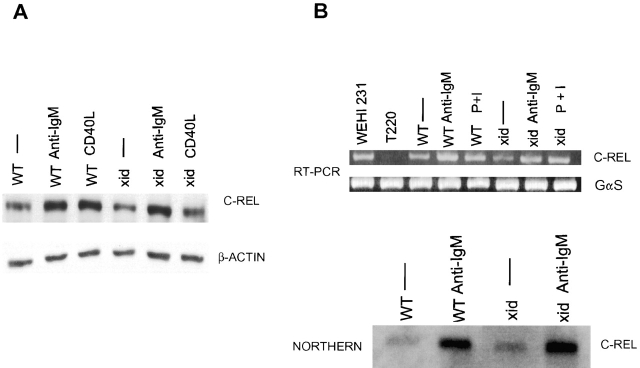

Normal Induction of c-rel Transcript and Normal Cytoplasmic Protein Levels in xid B Cells.

The lack of IgM-mediated NF-κB translocation and DNA binding in xid B cells could be due to diminished amounts of total NF-κB protein. Western blot analysis showed that the amounts of c-rel were similar in wild-type and xid B cells under various conditions (Fig. 2 A). In addition, we found that the level of c-rel mRNA increased normally after anti-IgM stimulation of wild-type or xid B cells (Fig. 2 B, top panel, reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR and bottom panel, Northern blot analysis). This finding suggests that BCR-induced c-rel transcription is not dependent on NF-κB, though it is known that in vitro overexpression of c-rel can increase constitutive activity of the c-rel promoter 51. Given the adequate amounts of cellular c-rel transcript and protein, it was likely that there was a failure to translocate cytoplasmic c-rel protein to the nucleus upon IgM cross-linking.

Figure 2.

Anti-IgM induces normal c-rel transcript levels, and amounts of c-rel in xid B cells are normal. (A) Wild-type and xid B splenic cells were cultured for 4 h in medium, F(ab′)2 anti-IgM (10 μg/ml), or CD40 ligand (1:2 dilution), and whole cell extracts were prepared. C-rel Western blot analysis was performed using extracts prepared from 5 × 105 cells. β-actin served as a loading control. (B) Wild-type and xid splenic B cells were cultured for 4 h in medium, F(ab′)2 anti-IgM (10 μg/ml), or PMA and ionomycin (30 nM and 1 μM, respectively), and total RNA was prepared. RT-PCR (top panel) analysis was conducted using primers specific for c-rel (or GαS, which served as a loading control). RNA samples from WEHI231 and T220 cells served as positive and negative controls, respectively, for this assay. Northern analysis (bottom panel) was conducted using 10 μg of each sample. Equal loading was determined by ethidium bromide staining of 18S and 28S ribosomal bands (data not shown). These figures represent one of three experiments.

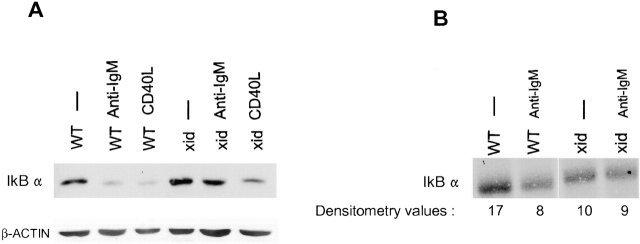

Inefficient Degradation of IκBα in xid B Cells.

In resting cells, NF-κB/Rel transcription factors are sequestered in the cytoplasm by IκB. There are three isoforms of IκB: α, β, and ε 52. We chose to study IκBα, a well characterized member of the inhibitory family. In wild-type splenic B cells, IκBα levels decreased after treatment for 4 h with anti-IgM or CD40 ligand stimulation (Fig. 3 A). In xid B cells, although the level of IκBα decreased in response to CD40 ligation, it did not decrease after anti-IgM cross-linking. The IκBβ protein behaved in a similar fashion (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Diminished IκBα degradation in anti-IgM–activated xid B cells. (A) Western blot analysis of IκBα expression (top panel) was performed with 25 μg of cytoplasmic extracts prepared from wild-type or xid splenic B cells cultured for 4 h in medium, F(ab′)2 anti-IgM (10 μg/ml), or CD40 ligand (1:2 dilution). β-actin served as a loading control (bottom panel). This figure represents one of three experiments. (B) Wild-type and xid splenic B cells were cultured with 35S-labeled cysteine and methionine, and the experiment was carried out as described (see text). Mean densitometry values from three independent experiments (shown as percent decrease in 35S-labeled IκBα ± SD) were: wild-type, 55.7 ± 15.1 and xid, 19.0 ± 7.4.

The most plausible explanation for maintenance of IκBα protein levels in xid B cells despite IgM stimulation is that the existing IκBα is not fully degraded. This possibility was examined by 35S pulse–chase experiments. Wild-type and xid splenic B cells were cultured with 35S-labeled cysteine and methionine, and the experiment carried was out as described in Materials and Methods. These 35S-labeled cells were then cultured for 1 h with or without F(ab′)2 anti-IgM. (We chose to stimulate cells for 1 h because we were unable to maintain primary B cells under these labeling conditions for longer times.) The cells were lysed, lysates precleared, 35S-labeled IκBα immunoprecipitated (twice), and the immunoprecipitates electrophoresed on SDS-PAGE. After IgM activation, wild-type B cells showed a 53% decrease in the level of labeled IκBα. In contrast, xid B cells consistently retained IκBα, as only a 10% decrease was detected (Fig. 3 B). These data show that xid B cells failed to fully degrade IκBα downstream of IgM cross-linking.

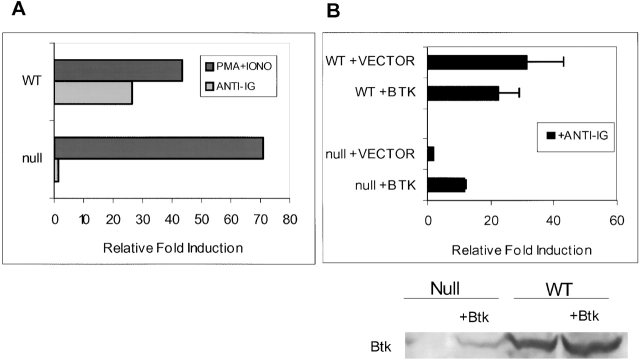

Reconstitution of IgM-mediated NF-κB Activity in DT40 BTK-deficient Cells.

DT40, the chicken B cell line, has been a crucial tool in the delineation of the signal transduction events after antigen receptor cross-linking 29 53 54. We used DT40 cells to further investigate the role of BTK in NF-κB activation. NF-κB–dependent luciferase reporter activity increased 25-fold after 4-h treatment of wild-type DT40 cells with anti-IgM (Fig. 4 A). The same luciferase reporter construct, but lacking the three NF-κB sites, was not induced under the same conditions (data not shown). BTK-deficient DT40 B cells failed to induce NF-κB activity after IgM stimulation (Fig. 4 A). Like wild-type cells, an increase of total protein tyrosine phosphorylation was detected after anti-IgM cross-linking of BTK-deficient DT40 cells. In BTK-deficient DT40 cells, NF-κB–dependent luciferase activity was induced by the pharmacological reagents phorbol ester and ionomycin. Expression of BTK in BTK-deficient cells restored the ability of membrane IgM to activate NF-κB (Fig. 4 B). Western blot analysis demonstrated that BTK protein was expressed in BTK-deficient cells in these assays (Fig. 4 B).

Figure 4.

Reconstitution of IgM-mediated NF-κB activity in BTK-deficient DT40 cells by ectopic expression of wild-type (WT) BTK. (A) Transient transfections of WT and BTK-deficient DT40 cells were conducted with NF-κB–driven luciferase reporter and pRLTK constructs, the latter serving as an internal transfection control for the assay. Cells were cultured for 16 h and then stimulated for 4 h with medium, M4 anti-chicken IgM (10 μg/m; light bars), or PMA and ionomycin (30 nM and 1 mM, respectively; dark bars). Cells were lysed and assayed as described in Materials and Methods. For each sample, luciferase activity was normalized to the pRLTK internal control. The graph shows the fold induction of luciferase activity relative to the luciferase activity detected in the lysates of cells cultured in medium only (= 1). This figure is representative of five experiments. (B) 10 μg of wild-type BTK or vector (pApuro) was transiently transfected together with reporter and internal control constructs as described above (A). Null + Vector lane shows background activity levels. PMA and ionomycin treatment of these cells resulted in similar induction (data not shown). Western blot analysis for detection of BTK expression was performed using lysates (equivalent of 2.5 × 106 cells) from this assay. The anti-BTK antibody recognizes both mouse and chicken BTK protein. The reactivity of this antibody for the different BTK species is not known, and the fraction of cells transfected was not determined the expression levels in wild-type and transfected cells cannot be compared. The fold induction values are the mean of three experiments ± SD.

The xid Mutation Diminishes the Ability of Ectopic BTK to Induce NF-κB Activation.

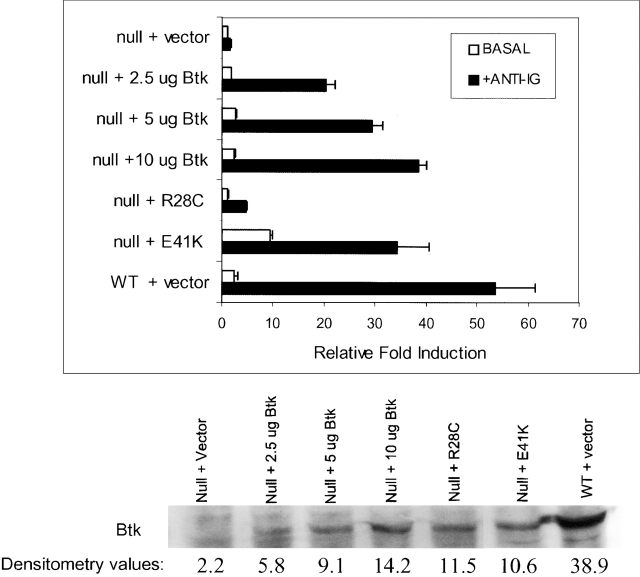

BTK is similar to Src kinases in that it contains SH1, SH2, and SH3 domains. In addition, it also contains a proline-rich and a unique region (together called the Tec homology domain) and a PH domain. The PH domain has high affinity for phosphoinositide phospholipids 20 and is required for membrane localization of the kinase. The R28C (xid) mutation of the PH domain decreases the affinity of BTK for phospholipids and other ligands 20 55. The E41K (gain-of-function) mutation in the BTK PH region increases affinity for PtdIns-3,4,5-P2 56 and results in constitutive membrane association and activity 57. Using ectopic expression of BTK in BTK-deficient DT40 cells, we asked how mutations of the BTK PH domain affected DT40 IgM–mediated NF-κB activity. In these assays, we found that it was necessary to use higher amounts of mutant DNA constructs to express mutant BTK at levels comparable to wild type. It is possible that the mutant proteins are unstable, though we have not examined this. We find that the basal NF-κB activity increased ninefold when the E41K (gain-of-function) mutant was expressed (Fig. 5). No change in basal activity was detected when a similar level of the R28C (xid) mutant was expressed. When comparable amounts of wild-type and mutant proteins were expressed, wild-type BTK allowed a 29-fold increase in NF-κB activity. The increase in reporter activity with the gain-of-function and xid mutants were 34- and 5-fold, respectively.

Figure 5.

The xid (R28C) mutation decreases BTK-dependent NF-κB activation. Transient transfections of BTK-deficient DT40 cells were conducted using 30 μg of vector (pApuro), 2.5, 5, or 10 μg of wild-type BTK, or 30 μg of BTK mutants, R28C, and E41K along with the NF-κB–driven luciferase reporter construct and the pRLTK internal control. Vector DNA was added when necessary to allow for equivalent micrograms of DNA to be transfected. Cells were cultured for 16 h and then stimulated for 4 h with medium, M4 anti-chicken IgM (10 μg/ml; black bars), or PMA and ionomycin (30 nM and 1 mM, respectively). Cells were lysed and assayed as described in Materials and Methods. For each sample, luciferase activity was normalized to the pRLTK internal control. The graph shows the fold induction of luciferase activity relative to the luciferase activity detected in the lysates from unstimulated BTK-deficient cells transfected with vector (= 1). The fold induction values are the mean of three experiments ± SD. PMA and ionomycin treatment of all cells resulted in similar fold induction values (data not shown). Western analysis for detection of BTK expression was performed using lysates (equivalent of 2.5 × 106 cells) from this assay. The anti-BTK antibody recognizes both mouse and chicken BTK protein. Densitometry analysis was performed (see Results). This figure represents one of three Western blots.

Discussion

NF-κB/Rel Function Is Essential for B Cell Activation.

NF-kB/Rel function is essential for B cell activation. Our studies with murine B cells suggested that BTK function was required for induced degradation of IκB and subsequent NF-κB translocation and DNA binding (Fig. 1 and Fig. 3). Mice deficient in individual NF-κB/Rel family members and mice expressing a transdominant form of IκBα demonstrate the importance of these transcription factors in both CD40- and IgM-mediated B cell activation and proliferation 34 35 36 39. In particular, expression of a transdominant form of IκBα produced a phenotype strikingly similar to that of xid mice.

Schauer et al. 58 showed that IgM cross-linking of a B cell line, WEHI231, failed to activate NF-κB, leading to apoptosis. When CD40 ligand was used in combination with anti-IgM, these cells activated NF-κB and, in turn, blocked apoptosis 58. Thus, NF-κB proteins serve as “survival” factors, most likely due to their role in the initiation of specific transcription of genes that mediate survival. Previously, we showed that in contrast to wild-type cells, there is no induction of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL in IgM-activated xid B cells 32. NF-κB is essential for expression of Bcl-xL 59. Thus, in xid B cells, it may be the loss of NF-κB activity that renders the B cells susceptible to apoptosis after IgM cross-linking. It is doubtful that it is solely the loss of induced Bcl-xL that is responsible for the xid phenotype, because xid mice expressing a Bcl-xL transgene do not correct the total xid phenotype 60.

BTK Function in Developing versus Mature B Cells.

In comparison with circulating, mature B cells in wild-type mice, the B cells in xid mice express lower levels of surface IgD and higher levels of surface IgM 61. This observation suggests that xid B cells are in a transitional stage of B cell development en route to full maturity 62. Thus, the bulk of ex vivo B cells from wild-type and xid mice are at different stages of maturity, making direct comparison of their biochemistry problematic. To distinguish between an indirect, developmental role and a direct role for BTK in NF-κB activation, we turned our analysis to the transformed chicken B cell line DT40. The BTK-deficient variant of DT40 cells was generated previously by homologous recombination 29. These cells, like xid B cells, exhibit a defect in calcium signaling after IgM receptor cross-linking 29 63. We found that BTK-deficient DT40 cells lacked NF-κB activity after IgM cross-linking, corroborating our findings with xid B cells. Expression of BTK in BTK-deficient DT40 cells restored IgM-mediated NF-κB activation (Fig. 4 B). We conclude that BTK function in mature B cells is essential for BCR-induced NF-κB activation.

The Effect of BTK PH Domain Mutations on NF-κB Activation.

The R28C mutation is known to lower the ability of BTK to interact with and activate TFII-I and to mobilize calcium. In particular, this mutation dramatically reduces the affinity of BTK for the phosphoinositide phospholipid PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 20. Recombinant BTK PH fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP) localized to the cell membrane, as did the E41K, gain-of-function PH–GFP. The R28C, xid PH–GFP, failed to localize to the membrane 56. Related work by Gupta et al. showed that decreasing the levels of PIP3, by inhibition of PI-3 kinase or membrane SH2 domain–containing inositol 5′-phosphatase (SHIP) expression, led to inhibition of BTK membrane localization and activity 21. This block in BTK activity could be overcome when recombinant BTK was targeted to the membrane. Collectively, these data show that membrane localization of BTK is essential for normal function. We now show that expression of the E41K mutant BTK in BTK-deficient DT40 cells increased basal NF-κB activity ninefold and with anti-IgM cross-linking 34-fold (Fig. 5). In contrast, the equivalent BTK protein expression of the R28C mutant had no effect on basal activity, and with anti-Ig cross-linking only a fivefold increase in NF-κB activity was detected. These results are consistent with previous work showing that an intact PH domain is essential for BTK to function, in this case to activate NF-κB.

The Role of BTK in IgM Signaling.

Many studies have identified roles for BTK in important signal transduction events downstream of IgM that ultimately lead to cell cycle entry and proliferation, e.g., PLC-γ2 activation, calcium mobilization, IP3 generation, cyclin activation, and Bcl-xL upregulation 29 30 32 33 64 65. This study identifies another downstream event controlled by BTK, NF-κB/IκB activation. Studies of NF-κB activation in other pathways, such as CD40, TNF, and IL-1, have linked IκB and NF-κB regulation to a signaling cascade that includes the IκB kinases mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 (MEKK1) and NF-κB–inducing kinase (NIK) and TNF receptor–associated factors (TRAFs) 42 66 67 68. Previous studies have shown that IκB is degraded and NF-κB activated as a consequence of IgM signaling, but little else is known 43. Our laboratory is currently focusing on elucidating the molecules that link BTK with IκB.

Signals Transduced by mIgM and CD40.

There are many events common to CD40 and mIgM ligation, as both lead to activation of activator protein (AP)-1, NF-κB, nuclear factor and activator of transcription (NF-AT), and signal tranducers and activators of transcription (STATs), expression of Bcl-xL, and entry into cell cycle 32 36 69. Yet some differences are clear. These receptors exhibit differential regulation of Fas, CD5, CD23, and mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases 70 71 72. In addition, PKC is necessary for IgM- but not CD40-induced activation of NF-κB 36. Related work by Sen and colleagues has shown differential PKC and calcium requirements for individual NF-κB family members downstream of the BCR 73 74. In this study, we show that in the absence of BTK, NF-κB can be activated by CD40 ligation but not by IgM cross-linking (Fig. 1). This suggests that after IgM cross-linking, BTK, which is necessary for the phosphorylation of PLC-γ2 29, is in turn responsible for the activation of PKC and calcium mobilization and the activation of NF-κB.

Data from Bendall et al. showed that expression of a transdominant IκBα blocked IgM- but not LPS-mediated NF-κB activation 39. This study and others 75 suggest that the several B cell activators—CD40 ligand, antigen, and LPS—differentially regulate individual IκB family members. In the cytoplasm of resting cells, IκB family members interact with different NF-κB dimers 66 76. Whether CD40 (BTK-independent) and mIgM (BTK-dependent) receptors activate different IκB kinases ultimately leading to distinct gene transcription through activation of different NF-κB dimers will be the subject of future studies. Understanding the specific control of NF-κB activation could provide clues to the differential physiological outcomes of these B cell activation pathways.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Nancy Rice for expert technical advice, Simon Anderson for experimental contributions, Allen Parmelee for FACScan™ assistance, Dr. Genhong Cheng for the BTK plasmid, Mike Berne for sequencing analysis, and Drs. Robert Berland, Paul McLean, Amy Yee, and Naomi Rosenberg for excellent experimental advice.

This work was partially supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants AI15803 (to H.H. Wortis) and AI41035 (to R. Sen). U. Bajpai received partial support from NIH training grant AI07077.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: BCR, B cell receptor for antigen; BTK, Bruton's tyrosine kinase; EMSAs, electrophoretic mobility shift assays; GFP, green fluorescent protein; mIgM, membrane IgM; NF-κB, nuclear factor κB; PH, pleckstrin homology; PKC, protein kinase C; PLC-γ2, phospholipase Cγ2; SH, Src homology; xid, X-linked immunodeficiency; XLA, X-linked agammaglobulinemia.

References

- Tsukada S., Saffran D.C., Rawlings D.J., Parolini O., Allen R.C., Klisak I., Sparkes R.S., Kubagawa H., Mohandas T., Quan S. Deficient expression of a B cell cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase in human X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Cell. 1993;72:279–290. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90667-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings D.J., Saffran D.C., Tsukada S., Largaespada D.A., Grimaldi J.C., Cohen L., Mohr R.N., Bazan J.F., Howard M., Copeland N.G. Mutation of unique region of Bruton's tyrosine kinase in immunodeficient XID mice. Science. 1993;261:358–361. doi: 10.1126/science.8332901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J.D., Sideras P., Smith C.I., Vorechovsky I., Chapman V., Paul W.E. Colocalization of X-linked agammaglobulinemia and X-linked immunodeficiency genes. Science. 1993;261:355–358. doi: 10.1126/science.8332900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley M.E., Parolini O., Rohrer J., Campana D. X-linked agammaglobulinemianew approaches to old questions based on the identification of the defective gene. Immunol. Rev. 1994;138:5–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1994.tb00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings D.J., Witte O.N. Bruton's tyrosine kinase is a key regulator in B-cell development. Immunol. Rev. 1994;138:105–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1994.tb00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan W.N., Alt F.W., Gerstein R.M., Malynn B.A., Larsson I., Rathbun G., Davidson L., Muller S., Kantor A.B., Herzenberg L.A. Defective B cell development and function in Btk-deficient mice. Immunity. 1995;3:283–299. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90114-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerner J.D., Appleby M.W., Mohr R.N., Chien S., Rawlings D.J., Maliszewski C.R., Witte O.N., Perlmutter R.M. Impaired expansion of mouse B cell progenitors lacking Btk. Immunity. 1995;3:301–312. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vihinen M., Belohradsky B.H., Haire R.N., Holinski-Feder E., Kwan S.P., Lappalainen I., Lehvaslaiho H., Lester T., Meindl A., Ochs H.D. BTKbase, mutation database for X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA) Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:166–171. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.1.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings D.J., Witte O.N. The Btk subfamily of cytoplasmic tyrosine kinasesstructure, regulation and function. Semin. Immunol. 1995;7:237–246. doi: 10.1006/smim.1995.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Weers M., Verschuren M.C., Kraakman M.E., Mensink R.G., Schuurman R.K., van Dongen J.J., Hendriks R.W. The Bruton's tyrosine kinase gene is expressed throughout B cell differentiation, from early precursor B cell stages preceding immunoglobulin gene rearrangement up to mature B cell stages. Eur. J. Immunol. 1993;23:3109–3114. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830231210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike M., Kikuchi Y., Tominaga A., Takaki S., Akagi K., Miyazaki J., Yamamura K., Takatsu K. Defective IL-5-receptor-mediated signaling in B cells of X-linked immunodeficient mice. Int. Immunol. 1995;7:21–30. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go N.F., Castle B.E., Barrett R., Kastelein R., Dang W., Mosmann T.R., Moore K.W., Howard M. Interleukin 10, a novel B cell stimulatory factorunresponsiveness of X chromosome-linked immunodeficiency B cells. J. Exp. Med. 1990;172:1625–1631. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.6.1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Argumedo L., Lund F.E., Heath A.W., Solvason N., Wu W.W., Grimaldi J.C., Parkhouse R.M., Howard M. CD38 unresponsiveness of xid B cells implicates Bruton's tyrosine kinase (btk) as a regular of CD38 induced signal transduction. Int. Immunol. 1995;7:163–170. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata D., Kawakami Y., Inagaki N., Lantz C.S., Kitamura T., Khan W.N., Maeda-Yamamoto M., Miura T., Han W., Hartman S.E. Involvement of Bruton's tyrosine kinase in FcεRI-dependent mast cell degranulation and cytokine production. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187:1235–1247. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setoguchi R., Kinashi T., Sagara H., Hirosawa K., Takatsu K. Defective degranulation and calcium mobilization of bone-marrow derived mast cells from Xid and Btk-deficient mice. Immunol. Lett. 1998;64:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(98)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bona C., Mond J.J., Paul W.E. Synergistic genetic defect in B-lymphocyte function. I. Defective responses to B-cell stimulants and their genetic basis. J. Exp. Med. 1980;151:224–234. doi: 10.1084/jem.151.1.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Weers M., Brouns G.S., Hinshelwood S., Kinnon C., Schuurman R.K., Hendriks R.W., Borst J. B-cell antigen receptor stimulation activates the human Bruton's tyrosine kinase, which is deficient in X-linked agammaglobulinemia. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:23857–23860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki Y., Isselbacher K.J., Pillai S. Bruton tyrosine kinase is tyrosine phosphorylated and activated in pre-B lymphocytes and receptor-ligated B cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:10606–10609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings D.J., Scharenberg A.M., Park H., Wahl M.I., Lin S., Kato R.M., Fluckiger A.C., Witte O.N., Kinet J.P. Activation of BTK by a phosphorylation mechanism initiated by SRC family kinases. Science. 1996;271:822–825. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H., Wahl M.I., Afar D.E., Turck C.W., Rawlings D.J., Tam C., Scharenberg A.M., Kinet J.P., Witte O.N. Regulation of Btk function by a major autophosphorylation site within the SH3 domain. Immunity. 1996;4:515–525. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salim K., Bottomley M.J., Querfurth E., Zvelebil M.J., Gout I., Scaife R., Margolis R.L., Gigg R., Smith C.I., Driscoll P.C. Distinct specificity in the recognition of phosphoinositides by the pleckstrin homology domains of dynamin and Bruton's tyrosine kinase. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1996;15:6241–6250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N., Scharenberg A.M., Fruman D.A., Cantley L.C., Kinet J.P., Long E.O. The SH2 domain-containing inositol 5′-phosphatase (SHIP) recruits the p85 subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase during FcgammaRIIb1-mediated inhibition of B cell receptor signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:7489–7494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Desiderio S. BAP-135, a target for Bruton's tyrosine kinase in response to B cell receptor engagement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:604–609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes F., Hausser A., Storz P., Truckenmüller L., Link G., Kawakami T., Pfizenmaier K. Bruton's tyrosine kinase (Btk) associates with protein kinase C mu. FEBS Lett. 1999;461:68–72. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01424-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba Y., Nonoyama S., Matsushita M., Yamadori T., Hashimoto S., Imai K., Arai S., Kunikata T., Kurimoto M., Kurosaki T. Involvement of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein in B-cell cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase pathway. Blood. 1999;93:2003–2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinamard R., Fougereau M., Seckinger P. The SH3 domain of Bruton's tyrosine kinase interacts with Vav, Sam68 and EWS. Scand. J. Immunol. 1997;45:587–595. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1997.d01-447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cory G.O., Lovering R.C., Hinshelwood S., MacCarthy-Morrogh L., Levinsky R.J., Kinnon C. The protein product of the c-cbl protooncogene is phosphorylated after B cell receptor stimulation and binds the SH3 domain of Bruton's tyrosine kinase. J. Exp. Med. 1995;182:611–615. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto S., Iwamatsu A., Ishiai M., Okawa K., Yamadori T., Matsushita M., Baba Y., Kishimoto T., Kurosaki T., Tsukada S. Identification of the SH2 domain binding protein of Bruton's tyrosine kinase as BLNK—functional significance of Btk-SH2 domain in B-cell antigen receptor-coupled calcium signaling. Blood. 1999;94:2357–2364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluckiger A.C., Li Z., Kato R.M., Wahl M.I., Ochs H.D., Longnecker R., Kinet J.P., Witte O.N., Scharenberg A.M., Rawlings D.J. Btk/Tec kinases regulate sustained increases in intracellular Ca2+ following B-cell receptor activation. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1998;17:1973–1985. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takata M., Kurosaki T. A role for Bruton's tyrosine kinase in B cell antigen receptor-mediated activation of phospholipase C-gamma 2. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:31–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharenberg A.M., El-Hillal O., Fruman D.A., Beitz L.O., Li Z., Lin S., Gout I., Cantley L.C., Rawlings D.J., Kinet J.P. Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PtdIns-3,4,5-P3)/Tec kinase-dependent calcium signaling pathwaya target for SHIP-mediated inhibitory signals. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1998;17:1961–1972. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawrylowicz C.M., Keeler K.D., Klaus G.G. Activation and proliferation signals in mouse B cells. I. A comparison of the capacity of anti-Ig antibodies or phorbol myristic acetate to activate B cells from CBA/N or normal mice into G1. Eur. J. Immunol. 1984;14:244–250. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830140308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J.S., Teutsch M., Dong Z., Wortis H.H. An essential role for Bruton's [corrected] tyrosine kinase in the regulation of B-cell apoptosis [published erratum appears in Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996. 93:15522] Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:10966–10971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brorson K., Brunswick M., Ezhevsky S., Wei D.G., Berg R., Scott D., Stein K.E. xid affects events leading to B cell cycle entry. J. Immunol. 1997;159:135–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.L., Chiles T.C., Sen R.J., Rothstein T.L. Inducible nuclear expression of NF-kappa B in primary B cells stimulated through the surface Ig receptor. J. Immunol. 1991;146:1685–1691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis D.A., Sen R., Rice N., Rothstein T.L. Receptor-specific induction of NF-kappaB components in primary B cells. Int. Immunol. 1998;10:285–293. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis D.A., Karras J.G., Ke X.Y., Sen R., Rothstein T.L. Induction of the transcription factors NF-kappa B, AP-1 and NF-AT during B cell stimulation through the CD40 receptor. Int. Immunol. 1995;7:151–161. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontgen F., Grumont R.J., Strasser A., Metcalf D., Li R., Tarlinton D., Gerondakis S. Mice lacking the c-rel proto-oncogene exhibit defects in lymphocyte proliferation, humoral immunity, and interleukin-2 expression. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1965–1977. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.16.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi T.S., Takahashi T., Taguchi O., Azuma T., Obata Y. NF-kappa B RelA-deficient lymphocytesnormal development of T cells and B cells, impaired production of IgA and IgG1 and reduced proliferative responses. J. Exp. Med. 1997;185:953–961. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.5.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendall H.H., Sikes M.L., Ballard D.W., Oltz E.M. An intact NF-kappa B signaling pathway is required for maintenance of mature B cell subsets. Mol. Immunol. 1999;36:187–195. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(99)00031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland C.L., Krebs D.L., Gold M.R. An 11-amino acid sequence in the cytoplasmic domain of CD40 is sufficient for activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase, activation of MAPKAP kinase-2, phosphorylation of I kappa B alpha, and protection of WEHI-231 cells from anti-IgM-induced growth arrest. J. Immunol. 1999;162:4720–4730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaka Y., Calderhead D.M., Manning E.M., Hambor J.E., Black A., Geleziunas R., Marcu K.B., Noelle R.J. Activation and regulation of the IkappaB kinase in human B cells by CD40 signaling. Eur. J. Immunol. 1999;29:1353–1362. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199904)29:04<1353::AID-IMMU1353>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsing Y., Hostager B.S., Bishop G.A. Characterization of CD40 signaling determinants regulating nuclear factor-kappa B activation in B lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 1997;159:4898–4906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerondakis S., Grumont R., Rourke I., Grossmann M. The regulation and roles of Rel/NF-kappa B transcription factors during lymphocyte activation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1998;10:353–359. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80175-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teutsch M., Higer M., Wang D., Wortis H.W. Induction of CD5 on B and T cells is suppressed by cyclosporin A, FK- 520 and rapamycin. Int. Immunol. 1995;7:381–392. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane P.J., Brocker T. Developmental regulation of dendritic cell function. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1999;11:308–313. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit P.X., Lecoeur H., Zorn E., Dauguet C., Mignotte B., Gougeon M.L. Alterations in mitochondrial structure and function are early events of dexamethasone-induced thymocyte apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 1995;130:157–167. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takata M., Sabe H., Hata A., Inazu T., Homma Y., Nukada T., Yamamura H., Kurosaki T. Tyrosine kinases Lyn and Syk regulate B cell receptor-coupled Ca2+ mobilization through distinct pathways. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1994;13:1341–1349. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berland R., Wortis H.H. An NFAT-dependent enhancer is necessary for anti-IgM-mediated induction of murine CD5 expression in primary splenic B cells. J. Immunol. 1998;161:277–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauxion F., Jamieson C., Yoshida M., Arai K., Sen R. Comparison of constitutive and inducible transcriptional enhancement mediated by kappa B-related sequencesmodulation of activity in B cells by human T-cell leukemia virus type I tax gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:2141–2145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice N.R., Ernst M.K. In vivo control of NF-kappa B activation by I kappa B alpha. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1993;12:4685–4695. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06157.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumont R.J., Richardson I.B., Gaff C., Gerondakis S. rel/NF-kappa B nuclear complexes that bind kB sites in the murine c-rel promoter are required for constitutive c-rel transcription in B-cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1993;4:731–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside S.T., Israel A. I kappa B proteinsstructure, function and regulation. Semin. Cancer Biol. 1997;8:75–82. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1997.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.L., Forman M.S., Kurosaki T., Pure E. Syk is required for BCR-mediated activation of p90Rsk, but not p70S6k, via a mitogen-activated protein kinase-independent pathway in B cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:18200–18208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.18200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidorenko S.P., Law C.L., Klaus S.J., Chandran K.A., Takata M., Kurosaki T., Clark E.A. Protein kinase C mu (PKC mu) associates with the B cell antigen receptor complex and regulates lymphocyte signaling. Immunity. 1996;5:353–363. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novina C.D., Kumar S., Bajpai U., Cheriyath V., Zhang K., Pillai S., Wortis H.H., Roy A.L. Regulation of nuclear localization and transcriptional activity of TFII-I by Bruton's tyrosine kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:5014–5024. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.5014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnai P., Rother K.I., Balla T. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent membrane association of the Bruton's tyrosine kinase pleckstrin homology domain visualized in single living cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:10983–10989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Rawlings D.J., Park H., Kato R.M., Witte O.N., Satterthwaite A.B. Constitutive membrane association potentiates activation of Bruton tyrosine kinase. Oncogene. 1997;15:1375–1383. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer S.L., Wang Z., Sonenshein G.E., Rothstein T.L. Maintenance of nuclear factor-kappa B/Rel and c-myc expression during CD40 ligand rescue of WEHI 231 early B cells from receptor-mediated apoptosis through modulation of I kappa B proteins. J. Immunol. 1996;157:81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.H., Dadgostar H., Cheng Q., Shu J., Cheng G. NF-kappaB-mediated up-regulation of Bcl-x and Bfl-1/A1 is required for CD40 survival signaling in B lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:9136–9141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solvason N., Wu W.W., Kabra N., Lund-Johansen F., Roncarolo M.G., Behrens T.W., Grillot D.A., Nunez G., Lees E., Howard M. Transgene expression of bcl-xL permits anti-immunoglobulin (Ig)-induced proliferation in xid B cells. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187:1081–1091. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaus G.G., Holman M., Johnson-Leger C., Elgueta-Karstegl C., Atkins C. A re-evaluation of the effects of X-linked immunodeficiency (xid) mutation on B cell differentiation and function in the mouse. Eur. J. Immunol. 1997;27:2749–2756. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cariappa A., Kim T.J., Pillai S. Accelerated emigration of B lymphocytes in the Xid mouse. J. Immunol. 1999;162:4417–4423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsberg M.L., Brunswick M., Yamada H., Lees A., Inman J., June C.H., Mond J.J. Biochemical analysis of the immune B cell defect in xid mice. J. Immunol. 1991;147:3774–3779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings D.J. Bruton's tyrosine kinase controls a sustained calcium signal essential for B lineage development and function. Clin. Immunol. 1999;91:243–253. doi: 10.1006/clim.1999.4732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaki T. Molecular mechanisms in B cell antigen receptor signaling. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1997;9:309–318. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilker R., Freuler F., Pulfer R., Di Padova F., Eder J. All three IkappaB isoforms and most Rel family members are stably associated with the IkappaB kinase 1/2 complex. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;259:253–261. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz J.L., Baltimore D. NF-kappaB activation by a signaling complex containing TRAF2, TANK and TBK1, a novel IKK-related kinase. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1999;18:6694–6704. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiba H., Nakano H., Nishinaka S., Shindo M., Kobata T., Atsuta M., Morimoto C., Ware C.F., Malinin N.L., Wallach D. CD27, a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, activates NF-kappaB and stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase via TRAF2, TRAF5, and NF-kappaB-inducing kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:13353–13358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karras J.G., Wang Z., Huo L., Frank D.A., Rothstein T.L. Induction of STAT protein signaling through the CD40 receptor in B lymphocytesdistinct STAT activation following surface Ig and CD40 receptor engagement. J. Immunol. 1997;159:4350–4355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foote L.C., Schneider T.J., Fischer G.M., Wang J.K., Rasmussen B., Campbell K.A., Lynch D.H., Ju S.T., Marshak-Rothstein A., Rothstein T.L. Intracellular signaling for inducible antigen receptor-mediated Fas resistance in B cells. J. Immunol. 1996;157:1878–1885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata N., Kawasome H., Terada N., Gerwins P., Johnson G.L., Gelfand E.W. Differential activation and regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases through the antigen receptor and CD40 in human B cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 1999;29:2999–3008. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199909)29:09<2999::AID-IMMU2999>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wortis H.H., Teutsch M., Higer M., Zheng J., Parker D.C. B-cell activation by crosslinking of surface IgM or ligation of CD40 involves alternative signal pathways and results in different B-cell phenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:3348–3352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataraman L., Wang W., Sen R. Differential regulation of c-Rel translocation in activated B and T cells. J. Immunol. 1996;157:1149–1155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataraman L., Burakoff S.J., Sen R. FK506 inhibits antigen receptor-mediated induction of c-rel in B and T lymphoid cells. J. Exp. Med. 1995;181:1091–1099. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S.C., Wortis H.H., Stavnezer J. The ability of CD40L, but not lipopolysaccharide, to initiate immunoglobulin switching to immunoglobulin G1 is explained by differential induction of NF-kappaB/Rel proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:5523–5532. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside S.T., Epinat J.C., Rice N.R., Israel A. I kappa B epsilon, a novel member of the I kappa B family, controls RelA and cRel NF-kappa B activity. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1997;16:1413–1426. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]