Abstract

Type I interferons (IFNs) are cytokines exhibiting antiviral and antitumor effects, including multiple activities on immune cells. However, the importance of these cytokines in the early events leading to the generation of an immune response is still unclear. Here, we have investigated the effects of type I IFNs on freshly isolated granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)–treated human monocytes in terms of dendritic cell (DC) differentiation and activity in vitro and in severe combined immunodeficiency mice reconstituted with human peripheral blood leukocytes (hu-PBL-SCID) mice. Type I IFNs induced a surprisingly rapid maturation of monocytes into short-lived tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)–expressing DCs endowed with potent functional activities, superior with respect to the interleukin (IL)-4/GM-CSF treatment, as shown by FACS® analyses, mixed leukocyte reaction assays with allogeneic PBLs, and lymphocyte proliferation responses to HIV-1–pulsed autologous DCs. Type I IFN induced IL-15 production and strongly promoted a T helper cell type 1 response. Notably, injection of IFN-treated HIV-1–pulsed DCs in SCID mice reconstituted with autologous PBLs resulted in the generation of a potent primary immune response, as evaluated by the detection of human antibodies to various HIV-1 antigens. These results provide a rationale for using type I IFNs as vaccine adjuvants and support the concept that a natural alliance between these cytokines and monocytes/DCs represents an important early mechanism for connecting innate and adaptive immunity.

Keywords: interferon, dendritic cell maturation and activation, monocytes, SCID mice, immunity

Introduction

Understanding the mechanisms involved in the initiation of the immune response is a crucial issue in immunology with important implications for vaccine development. Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent antigen-presenting cells playing a pivotal role in the induction of the immune response 1 2 3. DCs are derived from hematopoietic progenitor cells 1 2, and are considered the “sentinels” of the immune system 3. Immature DCs are generally located in peripheral tissues, in sites where they can optimally survey for incoming pathogens. The interaction of DCs with pathogens leads to migration to secondary lymphoid organs where they can initiate a specific T cell response. This complex process is associated with differentiation and functional activation of DCs 2 3. Recently, improved methods for the in vitro generation of large numbers of DCs from peripheral blood monocytes have been established, thus allowing a more precise characterization of the events leading to maturation and activation of DCs under well-defined experimental conditions. Of interest, recent results indicate that DC maturation can occur directly from monocytes during transendothelial migration 4. However, the in vivo relevance of monocyte differentiation into DCs remains unclear. Likewise, the early mechanisms and factors naturally involved in the regulation of differentiation, activation, and survival of DCs from monocytes under physiological conditions or in response to infections are still largely unknown.

Type I IFNs are cytokines spontaneously expressed at low levels under normal physiological conditions 5, whose expression is highly enhanced soon after cell exposure to viruses or other stimuli 6. Because of their potent direct antiviral activity, which is combined with stimulatory effects on NK cells, type I IFNs are considered important mediators of the innate immunity 7. Recently, it has been reported that the so-called “natural IFN-producing cells” (IPCs), whose nature had remained elusive for many years, are represented by CD4+CD11c− type 2 DC precursors (pDC2s) 8, also defined as plasmacytoid monocytes 9, which produce unusually high amounts of type I IFN after microbial challenge.

Originally considered as simple antiviral substances, type I IFNs (especially IFN-α) have recently been reconsidered as important cytokines for the generation of a protective T cell–mediated immune response to virus infections and tumor growth 10. In particular, an ensemble of data obtained in different model systems has pointed out the importance of type I IFN in enhancing antibody production 11 and supporting the proliferation, functional activity, and survival of certain T cell subsets 12 13 14 15 16. Although scattered data suggesting a promoting effect of type I IFN on DC maturation have recently been reported 17 18 19, the role of the IFN system in the differentiation, functional activities, and survival of DCs has remained unclear.

In this study, we have investigated whether type I IFNs can represent an early and important player regulating the differentiation and activation of DCs from monocytes cultured in the presence of GM-CSF. We report that type I IFNs rapidly induce the differentiation of monocytes into DCs endowed with potent functional activities both in vitro and in vivo, by using the chimeric model of SCID mice reconstituted with human PBLs 20. DCs generated in the presence of type I IFN spontaneously produced considerable amounts of IL-15 and induced a Th1-biased immune response. Remarkably, DCs generated in the presence of IFN and pulsed with inactivated HIV-1 were capable of inducing a potent primary immune response in hu-PBL-SCID mice, as revealed by the appearance of high levels of human antibodies against a wide spectrum of HIV-1 proteins. On the whole, these results demonstrate that type I IFNs are powerful factors responsible for the rapid differentiation of monocytes into DCs endowed with potent functional activities, supporting the concept that a natural alliance between these cytokines and monocytes/DCs represents an important mechanism for regulating innate and adaptive immunity.

Materials and Methods

Cell Separation and Culture.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained from heparinized blood of normal donors by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation (Seromed). Monocytes were obtained either by 2 h adhesion in 25–75-cm2 flasks (Costar), or by standard Percoll density gradient centrifugation. In the majority of the experiments, monocytes were further enriched by depleting contaminating cells using negative immunoselection by anti–mouse Ig–conjugated magnetic beads (Dynal), incubating the cells for 30 min at 4°C with azide-free antibodies (0.5 μg/106 cells) to human CD3, CD19, and CD56 antigens (BD PharMingen). After this procedure, the resulting cell population was represented by >98% CD14+ monocytes, as assessed by flow cytometry. Blood-derived monocytes were plated at the concentration of 1–2 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 (GIBCO BRL) supplemented with 10% FCS. The following cytokines were added alone or in combination: GM-CSF (500 U/ml), IL-4 (1,000 U/ml; R&D Systems), and type I IFN (500–1,000 U/ml). In the majority of the experiments illustrated in this paper, we used consensus IFN (CIFN, specific activity of 109 U/mg protein) 21 provided by Amgen. CIFN is a synthetic type I IFN produced from recombinant DNA, whose sequence is based on a consensus derived from the amino acid sequences of the most common types of human IFN-α. In a series of experiments, IFN-α2b (PeproTech) and IFN-β (Serono) were also used. All of the IFN preparations used in this study were shown to be free of any detectable LPS contamination. After 3 and 6 d of culture, nonadherent and loosely adherent cells were collected and used for subsequent analysis. To assess terminal maturation, cells were cultured for an additional 2 d in the presence of the appropriate cytokine combination and LPS (1 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich).

Immunophenotypic Analysis.

Cells were washed and resuspended in PBS containing 1% human serum and incubated with a series of fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs to human antigens for 30 min at 4°C. The following mAbs were used for immunofluorescent staining: anti-CD14, CD11c, CD54, CD80, HLA-DR, CD95 (Fas) (Becton Dickinson), CD1a, CD40, CD86, Fas-L (NOK-1), (BD PharMingen), and CD83 (Immunotech). Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Data was collected and analyzed by using a FACSort™ (Becton Dickinson) flow cytometer, and data analysis were performed by CELLQuest™ software (Becton Dickinson). Cells were electronically gated according to light scatter properties in order to exclude cell debris and contaminating lymphocytes.

MLR.

Monocyte-depleted PBLs were seeded into 96-well plates (Costar) at 105 cells/well. Purified allogeneic DCs (5 × 103) were added to each well in triplicate. After 5 d, 1 mCi of [methyl-3H]thymidine (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) was added to each well and incubation was continued for an additional 18 h. Cells were finally collected by a Mach II Mcell (Tomtec) harvester and thymidine uptake was quantitated by liquid scintillation counting on a 1205 Betaplate (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

ELISA for IFN-γ and Other Cytokines.

Commercial ELISAs (R&D Systems) were used to quantitate human IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-12, and IL-15. ELISAs were performed in triplicate, and laboratory standards were included on each plate. Assay sensitivity was as follows: IFN-γ (3 pg/ml), IL-4 (10 pg/ml), IL-12 (0.5 pg/ml), and IL-15 (1 pg/ml).

Reverse Transcription PCR.

The mRNA from DCs was extracted by RNAzol B and processed as described previously 22. Transcripts were detected by amplifying the retrotranscribed RNA with specific primer pairs for IL-1β (sense, CTTCATCTTTGAAGAAGAACCTATCTTCTT; antisense, AATTTTTGGGATCTACACTCTCCAGCTGTA), TNF-α (sense, ATGAGCACTGAAAGCATGATCCGG; antisense, GCAATGAT-CCCAAAGTAGACCTGCCC), IL-12 p40 (sense, CCAAGAACTTGCAGCTGAAGA; sense, TGGGTCTATTCCGTTGTGTC), IL-15 (sense, CTCGTCTAGAGCCAACTGGGTGAATGTAATAAG; antisense, TACTTACTCGAGGAATCAATTGCAATCAAGAAGTG), and IL-18 (sense, TCTGACTGTAGAGATAATGC; antisense, GAACAGTGAACATTATAGATC). Primer sequences for TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) and TRAIL receptors (R1, R2, R3, and R4) are reported elsewhere 23. The samples were amplified for 30–35 cycles at the following conditions: 94°C for 40 s, 62°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 40 s. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was run in parallel to normalize the levels of human RNA in all the samples. All RT-PCR and products were in the linear range of amplification.

Apoptosis Detection.

Apoptosis was detected by staining with ApoAlert™ Annexin V-green fluorescent protein (GFP) (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACSort™ (Becton Dickinson).

DC-mediated Killing of Human Tumor Cells and Evaluation of the Functional Significance of TRAIL Expression.

Monocytes were cultured in the presence of IFN/GM-CSF for 5 d, washed, and resuspended in complete medium. DCs were then incubated for 12 h with human CD4+ Jurkat cells as targets (E/T ratio of 4:1). As a positive control for susceptibility of Jurkat cells to TRAIL-induced death, 0.1 μg/ml of soluble (s)TRAIL, and 2 μg/ml of enhancer antibody (Alexis) were added to target cells. In parallel cultures, 1 μg/ml TRAIL-R2/Fc (Alexis) was added to DC effector cells 15 min before adding tumor cells in order to specifically inhibit TRAIL-mediated killing. Apoptotic cell death of Jurkat cells was evaluated by flow cytometry using Annexin V-GFP (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.) and CD11c-PE (Becton Dickinson) staining. Cells were gated according to light scatter characteristics and absence of CD11c expression.

Induction of Primary Response to HIV-1 Antigens and Proliferation Assay.

HIV-1 SF162 strain was inactivated by aldrithiol (AT)-2 following a procedure recently described by Rossio et al. 24 and stored at −140°C until use. PBLs (4 × 106) were stimulated with 106 autologous DCs generated by treatment with either IFN/GM-CSF or IL-4/GM-CSF for 3 d and pulsed with AT-2–inactivated HIV-1 (40 ng of p24) for 2 h at 37°C. PBLs were restimulated 7 d later with inactivated virus–pulsed DCs. Proliferation assay was performed as follows: 5 × 103 HIV-1–pulsed DCs were added to 105 autologous PBLs into triplicate wells. After 6 d, 1 mCi of [methyl-3H]thymidine (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) was added to each well and incubation was continued for an additional 18 h. Cells were collected and thymidine uptake was quantitated as described above.

Enzyme-linked Immunospot Assay.

Enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay (Euroclone) was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, 96-well plastic plates (Maxisorp Nunc) were coated with capture anti–IFN-γ antibodies and blocked with 2% BSA. 10-fold dilutions (from 105 to 102) of PBLs from primary cultures were restimulated overnight with DCs pulsed with inactivated HIV-1, added to triplicate wells, and incubated for 18 h. After cell removal, plates were incubated with an anti–IFN-γ detection biotinylated antibody and streptavidin-conjugated alkaline phosphatase. Then, substrate solution was added and the frequency of IFN-γ–producing cells was evaluated by enumerating single spots on an inverted microscope.

Hu-PBL-SCID Mouse Model.

CB17 scid/scid female mice (Harlan) were used at 4 wk of age and kept under specific pathogen-free conditions. SCID mice were housed in microisolator cages and all food, water, and bedding were autoclaved before use. Hu-PBLs were obtained from the peripheral blood of healthy donors. All donors were screened for HIV-1 and hepatitis before donation. The hu-PBLs were obtained by Ficoll-Paque density gradient centrifugation. 20 × 106 cells were resuspended in 0.5 ml RPMI 1640 medium and injected intraperitoneally into the recipient mice. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1.5 × 106 autologous DCs, pulsed for 2 h at 37°C with AT-2–inactivated HIV-1 (40 ng of p24). 7 d later, mice were given a boost dose of AT-2–inactivated HIV-pulsed DCs. At days 7 and 14, sera from hu-PBL-SCID mice were assayed for the presence of human anti-HIV antibodies.

ELISA for Human Igs.

An ELISA system was used to quantitate human total Igs, IgM, IgG1, and IgG4 Igs in the sera of the chimeras by using anti–human total Ig and anti-IgM from Cappel-Cooper Biomedical, anti-IgG1, or anti-IgG4 (BD PharMingen). All ELISAs were performed in duplicate, and laboratory standards were included on each plate. Sera from nonreconstituted SCID mice were used as negative controls of all the ELISA determinations. ELISA for detection of specific anti-HIV antibodies was performed using a specific peptide (i.e., ERYLKDQQLLGIWGCSGKLIC) corresponding to amino acids 591–611 of the HIV-1 gp41 protein 25. Synthetic peptides were immobilized on Dynatec (Dynal) microtiter plates by an overnight incubation at 4°C. Serially diluted mouse sera were added and incubated for 90 min at room temperature. Finally, binding was revealed by reading A490 values after incubation with substrate chromogen. Values represent mean adsorbence value of each individual serum tested in duplicate. The cut-off value was calculated as mean adsorbence value of all the control sera plus 0.100 A. Sera showing A490 values higher than this threshold were considered positive for anti-HIV antibodies.

Western Blot.

Pooled sera from hu-PBL-SCID mice infected with HIV-1–pulsed DCs were assayed by Western blot (HIV Western blot kit; Cambridge Biotech). In brief, individual nitrocellulose strips were incubated overnight with different mouse serum samples (diluted 1:20) or with a human positive control serum (diluted 1:1,000). Visualization of the human Igs specifically bound to HIV-1 proteins was obtained by incubation with substrate chromogen after the addition of biotin-conjugated goat anti–human IgG and streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase.

Results

Characterization of DCs Differentiated from Monocytes in the Presence of Type I IFN and GM-CSF.

In a first set of experiments, we verified whether the addition of type I IFN together with GM-CSF to blood-derived monocytes could result in differentiation towards the DC phenotype compared with the effects achievable after the standard treatment with GM-CSF and IL-4, currently used for obtaining immature DCs from monocytes 2 26. In response to IFN/GM-CSF treatment, adherent monocytes rapidly became floating nonadherent cells within 3 d. The loss of adherence was associated with cellular aggregation, and large cell clusters were detected in the IFN/GM-CSF–treated cultures, while a large part of IL-4/GM-CSF–treated cells were still firmly adherent to the plastic surface. After 3 and 6 d of culture, cells treated with either IFN/GM-CSF or IL-4/GM-CSF were analyzed for the expression of surface markers associated with DC differentiation as well as of the monocytic marker CD14. Fig. 1 A illustrates the mean fluorescence values of a series of selected markers upon treatment of monocytes with either IFN/GM-CSF or IL-4/GM-CSF. The upregulation of costimulatory molecules (CD80, CD86, and CD40) was consistently higher in IFN/GM-CSF–treated cells than in cultures treated with IL-4/GM-CSF as early as 3 d after cytokine treatment. As shown in Fig. 1 B, the optimal enhancing effects on the expression of costimulatory molecules were observed with IFN doses ranging from 500 to 1,000 U/ml, while 100 U/ml of IFN did not result in any significant difference compared with cultures treated with GM-CSF alone (data not shown). Comparable enhancing effects on DC phenotype were observed using three different preparations of type I IFNs (i.e., CIFN, IFN-α2b, and IFN-β) added in conjunction with GM-CSF to blood-derived monocytes for 3 d of culture (Fig. 1 C).

Figure 1.

Upregulation of CD80, CD86, and CD40 expression in DCs generated in the presence of type I IFN and GM-CSF. (A) Comparison with the effects induced by IL-4/GM-CSF at 3 and 6 d of culture. Freshly isolated monocytes were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were treated with GM-CSF (500 U/ml) and with 1,000 U/ml of either CIFN or IL-4. At 3 and 6 d, cell phenotype was evaluated by FACS® analysis. Each bar is representative of four separate experiments. (B) Effects of different doses of type I IFN. Freshly isolated monocytes were isolated, cultured with cytokines, and analyzed for antigen expression on day 3, as described in Materials and Methods. Representative data from one out of three experiments are shown. (C) Effects of various preparations of type I IFN. Cultures were treated with 500 U/ml of GM-CSF and 1,000 U/ml of type I IFN, as indicated. FACS® analysis was performed on day 3.

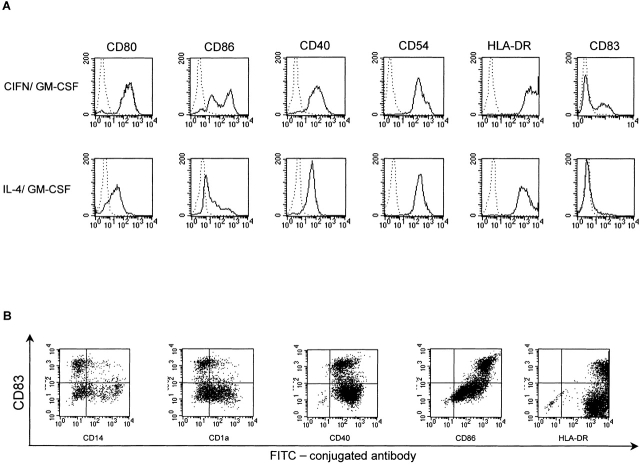

Fig. 2 A shows the comparison of the representative FACS® profiles obtained at 3 d of cytokine treatment. Notably, cultures treated with IFN showed not only a marked upregulation of costimulatory molecules and HLA-DR antigen, but also a clear-cut induction of the expression of the CD83 antigen (30–40% of positive cells), which is considered as a marker of mature/activated DCs. On the contrary, this marker was expressed only by a strict minority of IL-4/GM-CSF–cultured DCs (2–5%). As shown in Fig. 2 B, CD83+ cells constituted a discrete population, largely CD14−CD1a−. Moreover, further characterization demonstrated that CD83 was consistently associated with high levels of CD86 and HLA-DR expression (Fig. 2 B). These data suggested that IFN treatment not only induced an upregulation of costimulatory molecules, but also promoted the appearance of partially activated CD83+ DCs. The irreversible commitment of IFN-treated cultures to undergo an advanced maturation process was suggested by the finding that, upon cytokine removal, these cells retained a DC phenotype without adhering to the plastic surface, whereas IL-4/GM-CSF–treated cells reacquired the macrophage features and readily readhered to culture plates within 3 d, unless preventively stimulated to terminally differentiate by LPS (data not shown). IFN/GM-CSF–treated cells proved to be fully susceptible to undergo activation/terminal differentiation after LPS treatment, as revealed by the enhanced expression of accessory molecules (data not shown) as well as by a massive CD83 induction (Fig. 3 A).

Figure 2.

Phenotype of monocyte-derived DCs after 3 d of cytokine treatment. (A) Representative dot histogram FACS® profiles. Dotted lines represent the staining with isotype-matched control antibodies. (B) Dot plot FACS® analysis of DCs generated in the presence CIFN/GM-CSF for 3 d. Cells were double stained with an antibody to CD83 in conjunction with a panel of antibodies to characterize the CD83+ DC population.

Figure 3.

Induction of terminal maturation and cytokine expression in DCs activated with LPS. (A) Dot histogram FACS® profiles showing CD83 expression upon LPS stimulation. Monocytes were cultured with the cytokine combinations for 5 d before performing FACS® analysis. LPS (1 μg/ml) was added on day 3. (B) RT-PCR analysis of cytokine mRNA expression in DCs generated in the presence of either CIFN/GM-CSF or IL-4/GM-CSF activated or not by LPS. Cultures were treated as described for A. RNAs were extracted on day 5 and RT-PCR was performed as described in Materials and Methods. (C) Secretion of IL-15 and bioactive IL-12 p70 in DC supernatants. Cell supernatants were collected at the time of RNA extraction (B), and ELISAs were performed as described previously.

DCs produce a series of cytokines implicated in the initiation of the immune response, especially when activated by mutual interaction with T cells or by encounter with viral pathogens and bacterial products. Thus, it was of interest to evaluate whether IFN/GM-CSF–cultured DCs exhibited any specific pattern of cytokine expression compared with cells cultured in the presence of IL-4/GM-CSF. Comparative RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 3 B) showed that IFN/GM-CSF DCs expressed high levels of mRNA for IL-1β. Notably, induction of IL-15 expression was selectively detected in cultures treated with IFN/GM-CSF. As IL-15 expression is tightly regulated at the translational level, it was of interest to determine whether detectable levels of the cytokine could be revealed in the supernatants of IFN-treated cultures. As illustrated in Fig. 3 C, remarkable levels of IL-15 were secreted in response to the IFN/GM-CSF treatment. The cytokine expression pattern observed in IFN-treated cultures resembled that observed in LPS-stimulated DCs. At the mRNA level, similar IL-12 p40 transcript levels were usually detected in response to LPS stimulation of both IFN/GM-CSF– and IL-4/GM-CSF–cultured DCs. As type I IFN pretreatment had been shown to differentially affect the LPS-stimulated production of IL-12 p40 subunit and the bioactive p70 heterodimer 27, we also assessed the production of the bioactive form of IL-12 at the protein level. As shown in Fig. 3 C, comparable levels of IL-12 (p70) were detected by ELISA in supernatants from both types of LPS-stimulated DCs.

DC differentiation from monocytes treated with type I IFN (500–1,000 U/ml) and GM-CSF was reproducibly characterized by a decrease in the number of DCs recovered after 6 d of culture. We then evaluated the percentage of Annexin V-GFP+ cells at 3 and 5 d after cytokine treatments. On day 3, DC cultures generated in the presence of either IFN/GM-CSF or IL-4/GM-CSF both exhibited low levels of Annexin V-GFP+ cells (i.e., ∼7–12%). Notably, 40% of the IFN/GM-CSF DCs were stained with Annexin V-GFP on day 5, revealing an intrinsic attitude of a considerable portion of these cells to undergo apoptosis (Fig. 4 A). In contrast, only a small fraction (∼10%) of cells treated with IL-4/GM-CSF were stained with Annexin V-GFP at this time point. Thus, it was of interest to investigate whether IFN could induce the expression of genes involved in apoptotic pathways. As assessed by FACS® analysis, both types of DC cultures expressed comparable Fas levels, whereas FasL expression was not detected (Fig. 3 B). The expression of the novel apoptosis-inducing molecule TRAIL, which has recently been shown to be induced by both IFN-α and IFN-γ 23 28 and its receptors was evaluated by RT-PCR analysis. Comparative RT-PCR analysis revealed a significant induction of TRAIL expression in IFN/GM-CSF DCs, which was virtually absent in standard IL-4/GM-CSF DCs unless activated by LPS treatment (Fig. 4 C). Both TRAIL and the functionally active TRAIL receptors (R1 and R2) were upregulated in response to LPS treatment.

Figure 4.

Enhanced apoptosis and induction of TRAIL expression in DCs generated with CIFN (1,000 U/ml) and GM-CSF (500 U/ml). (A) Dot histogram profiles showing Annexin V-GFP staining of apoptotic cells in DCs generated in the presence of either CIFN/GM-CSF or IL-4/GM-CSF cultures, analyzed after 5 d of cytokine treatment. (B) FACS® profiles of Fas and FasL expression in monocyte-derived DCs. Dotted lines represent the staining with isotype-matched control antibodies. Cells were analyzed on day 5 of culture. (C) RT-PCR analysis of TRAIL and TRAIL receptors in DCs treated or not with LPS. Monocytes were cultured with the cytokine combinations for 5 d before performing RNA extraction. LPS (1 μg/ml) was added on day 3. RT-PCR was performed as described in Materials and Methods. (D) DC-mediated killing of Jurkat cells and evaluation of the functional significance of TRAIL expression. Monocytes were cultured in the presence of IFN/GM-CSF for 5 d, washed, and resuspended in complete medium. Jurkat cells were cultured for 12 h in complete medium alone or in the presence of sTRAIL or IFN/GM-CSF DCs (E/T ratio 4:1). To evaluate the TRAIL involvement in the DC-mediated induction of apoptosis in target cells, in some cultures TRAIL-R2/Fc was added to DC effector cells 15 min before the addition of Jurkat cells. Phosphatidylserine externalization was monitored by Annexin V-GFP binding on gated Jurkat cells, as described in Materials and Methods. The percentage of Annexin V-GFP+ cells is indicated for each condition. Similar results were obtained in two additional experiments.

The possible function of TRAIL expression on DCs generated in the presence of IFN/GM-CSF was evaluated by experiments of DC-mediated killing of human Jurkat cells, which are susceptible to TRAIL-induced cell death. As shown in Fig. 4 D, DCs generated in the presence of IFN/GM-CSF were capable of inducing apoptotic cell death in a remarkable percentage of Jurkat cells. The involvement to TRAIL expression on DCs in the induction of apoptosis in target cells was revealed by the finding that apoptotic cell death of Jurkat cells was inhibited by the soluble inhibitor TRAIL-R2/Fc (Fig. 4 D).

Functional Activities of DCs Generated from IFN/GM-CSF–treated Monocytes in Vitro and in the Hu-PBL-SCID Mouse Model

Enhanced Allostimulatory Properties of DCs Generated in the Presence of IFN/GM-CSF.

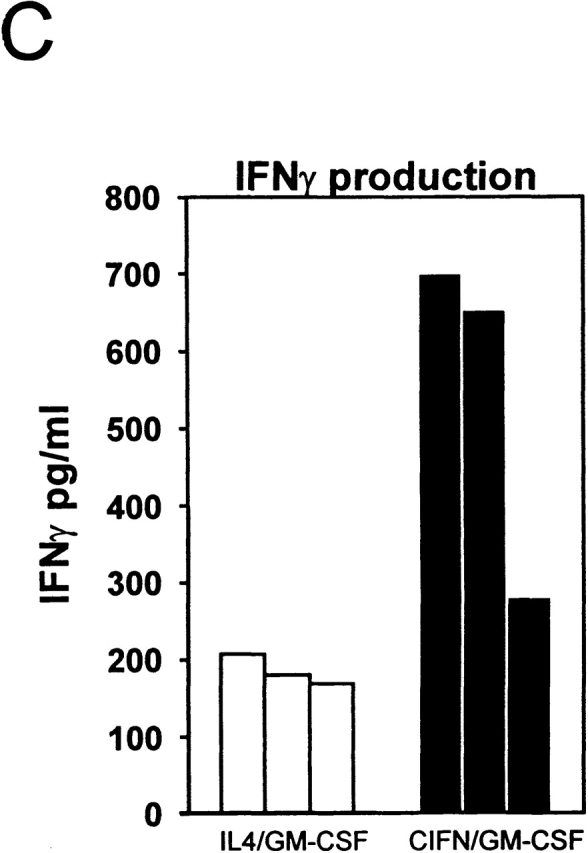

Next, we performed a series of functional experiments aimed at comparing the ability of DCs generated from monocytes treated with IFN/GM-CSF to stimulate allogeneic MLRs and to induce IFN-γ production by allogeneic PBLs with respect to DCs obtained after IL-4/GM-CSF stimulation. In a first set of experiments, we evaluated the proliferative response of monocyte-depleted PBLs when cocultured with different numbers of allogeneic DCs generated in the presence of either IFN/GM-CSF or IL-4/GM-CSF. As shown in Fig. 5 A, at all the stimulator/responder ratios, DCs obtained in the presence of GM-CSF and CIFN (1,000 U/ml) showed a stronger capability to simulate the proliferation of allogeneic lymphocytes than IL-4/GM-CSF DCs. In subsequent experiments, a stimulator/responder ratio of 1:20 was generally used. As illustrated in Fig. 5 B, a strong proliferative response, as evaluated by [3H]thymidine incorporation assay, was observed in MLR experiments using IFN/GM-CSF DCs. In contrast, DCs generated from the same donor in the presence of 100 U/ml IFN elicited a poor proliferative response. This was not unexpected, as DCs generated with 100 U/ml IFN exhibited very low levels of costimulatory molecules, as determined by flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 1 B). A specific feature of MLRs generated with DCs developed in the presence of type I IFNs was the considerable IFN-γ production, which was definitively higher than that found in the corresponding cocultures using DCs generated by the IL-4/GM-CSF addition (Fig. 5 C), suggesting a prominent capability of IFN/GM-CSF DCs to promote a Th1 response.

Figure 5.

MLR assays with DCs generated in the presence of either CIFN/GM-CSF or IL-4/GM-CSF. (A) Effects of different numbers of DCs generated in the presence of either IFN/GM-CSF or IL-4/GM-CSF on the proliferative response of allogeneic monocyte–depleted PBLs. Monocyte-depleted PBLs were seeded into 96-well plates at 105 cells/well. Different numbers of purified allogeneic DCs, generated in the presence of either CIFN/GM-CSF or IL-4/GM-CSF for 3 d as indicated in Materials and Methods, were added to each well. After 5 d, thymidine incorporation was determined as described in Materials and Methods. (B) DCs generated in the presence of 1,000 U/ml of CIFN together with GM-CSF exhibit a potent allostimulatory capacity, whereas GM-CSF–treated cells obtained in the presence of 100 U/ml of IFN were poor stimulators in the MLR assay. Allogeneic PBLs were stimulated by DCs (at a stimulator/responder ratio of 1:20) previously cultured for 3 d with IFN/GM-CSF or IL-4/GM-CSF, and lymphocyte proliferation was measured as described in Materials and Methods. (C) IFN-γ production in the supernatants from MLRs. PBLs from three different donors were stimulated with allogeneic DCs generated by culturing the cells in the presence of either CIFN/GM-CSF or IL-4/GM-CSF for 3 d (stimulator/responder ratio of 1:20). IFN-γ production in the supernatants from MLRs was tested at the time of performing the lymphocyte proliferation assay (B). Each bar represents the value obtained with PBLs from different donors.

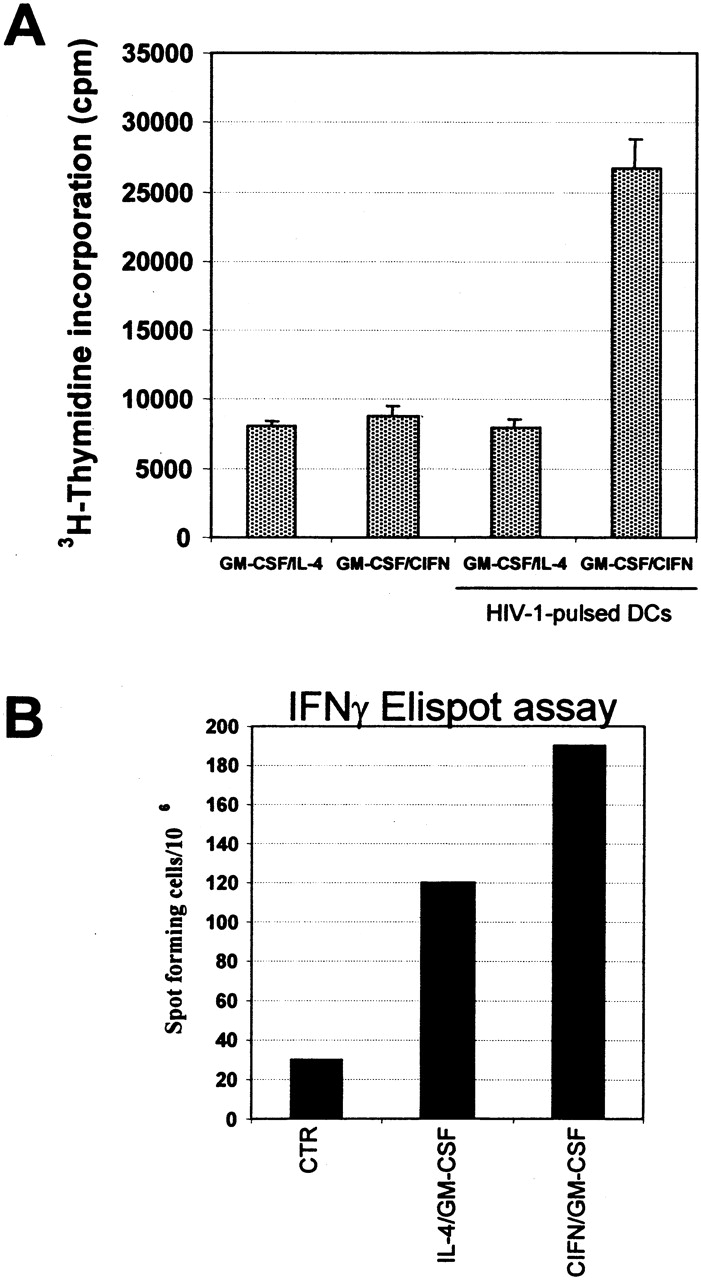

Primary Response to HIV Antigens Elicited by IFN/GM-CSF DCs In Vitro: Comparison with the Activity of DCs Generated in the Presence of IL-4/GM-CSF.

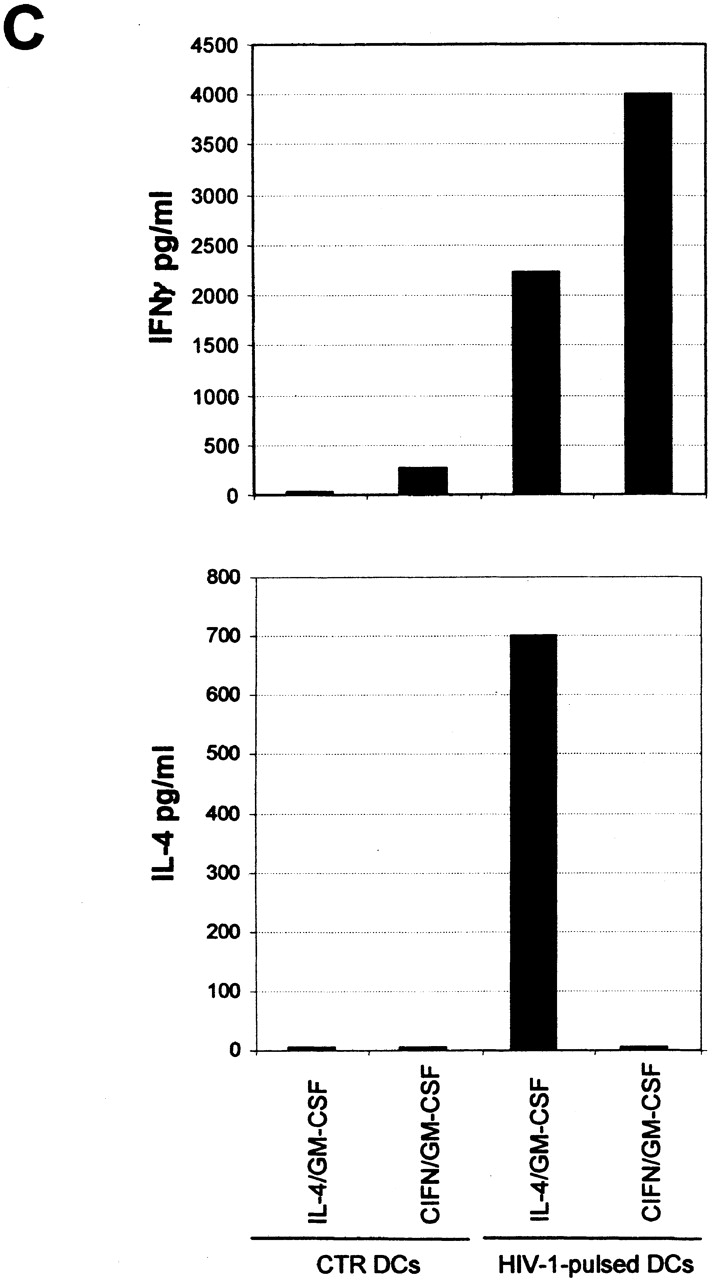

We then evaluated the ability of DCs generated in the presence of either IFN/GM-CSF or IL-4/GM-CSF to initiate a primary response in autologous PBLs by using inactivated HIV-1 as an immunogen. To inactivate HIV, we followed a recently described procedure consisting in the use of 2,2′-dithiodipyridine (AT-2), which inactivates HIV by selectively disrupting the p7 nucleocapsid (NC) protein, leaving intact the conformation and fusogenic activity of the gp120 HIV-1 protein 24. Autologous PBLs were stimulated with DCs pulsed with AT-2–inactivated HIV-1. We evaluated the priming activity of DCs generated in the presence of either IFN/GM-CSF or IL-4/GM-CSF for 3 d, pulsed with inactivated HIV-1 and cocultivated with autologous PBLs. Virus-pulsed IFN/GM-CSF DCs not only proved to be better stimulators of [3H]thymidine uptake by autologous PBLs than IL-4/GM-CSF cells (Fig. 6 A), but also induced a stronger Th1-oriented response. In fact, the ELISPOT analysis showed a higher number of IFN-γ–producing cells in primary cultures stimulated with IFN/GM-CSF DCs compared with cultures stimulated with IL-4/GM-CSF DCs (Fig. 6 B), consistent with the detection of higher levels of IFN-γ in culture supernatants (Fig. 6 C). Notably, little or no secretion of IL-4 was detected in cultures stimulated with virus-pulsed IFN/GM-CSF DCs, whereas considerable amounts of this cytokine were found in the supernatants of cultures exposed to IL-4/GM-CSF DCs (Fig. 6 C).

Figure 6.

In vitro induction of a primary immune response to HIV-1 antigens in PBLs cocultivated with autologous DCs pulsed with inactivated HIV-1. (A) DCs were generated by standard treatment of freshly isolated monocytes with either CIFN/GM-CSF or IL-4/GM-CSF for 3 d as described in Materials and Methods. PBLs were stimulated on day 0 and restimulated on day 7 with the autologous DCs pulsed with AT-2–inactivated HIV-1 at a stimulator/responder ratio of 1:4. Control cultures were incubated with unpulsed autologous DCs. Exogenous IL-2 (25 U/ml) was added every 4 d. At day 14, the cultures were restimulated with DCs pulsed with AT-2–inactivated HIV-1, and after 24 h [3H]thymidine was added. Cells were harvested after an 18-h incubation. (B) The frequency of IFN-γ–producing cells was determined by enumeration of single IFN-γ–producing cells by ELISPOT, using cells harvested at 24 h after the third stimulation with virus-pulsed DCs. PBLs stimulated with PHA (2 μg/ml) were used as control (CTR). (C) Evaluation of IL-4 and IFN-γ production in the supernatants of primary cultures stimulated three times with autologous DCs. Supernatants from the cell samples described in A were tested for cytokine production by ELISAs.

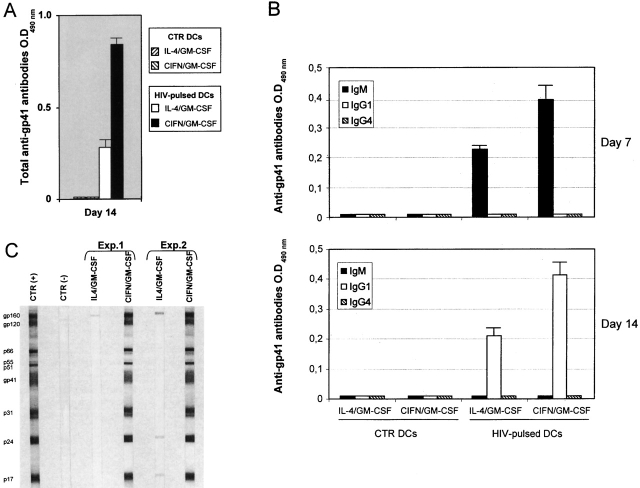

Primary Antibody Response to HIV Antigens Elicited by IFN/GM-CSF DCs in the Hu-PBL-SCID Mouse Model: Comparison with the Activity of DCs Generated in the Presence of IL-4/GM-CSF.

The strong response elicited in vitro by DCs pulsed with AT-2–inactivated HIV prompted us to evaluate whether these cells could also favor an in vivo primary immunization and antibody response in SCID mice reconstituted with human PBLs. Recent data have suggested that a human primary immune response can be generated in hu-PBL-SCID mice 29 30 31 32, especially when the chimeras are injected with antigen-pulsed DCs 31. Thus, hu-PBL-SCID mice were immunized with donor autologous DCs, pulsed for 2 h with AT-2–inactivated HIV SF162. A boost dose was given 7 d later. At day 14, mouse sera were collected and assayed for the presence of anti-HIV antibodies. ELISA studies revealed the presence of high levels of anti-gp41 antibodies in hu-PBL-SCID mice immunized with HIV-1–pulsed DCs. Hu-PBL-SCID mice immunized with DCs generated in the presence of IFN/GM-CSF showed higher levels of anti-HIV antibodies than the xenochimeras injected with DCs obtained after IL-4/GM-CSF treatment (Fig. 7 A). At day 7, anti–HIV-1 antibodies were shown to belong mainly to the IgM isotype (Fig. 7 B). At day 14, antibodies belonging to the IgG1 isotype were detected especially in mice immunized with IFN/GM-CSF–cultured DCs, thus suggesting a Th1-biased response (Fig. 7 B). As the ELISAs used in the experiments described above only detected antibodies to specific epitopes of the HIV-1 gp41 protein, it was important to evaluate the total spectrum of human antibodies against HIV-1 proteins by performing Western blot analysis with pooled sera from hu-PBL-SCID mice injected with virus-pulsed DCs. Remarkably, sera from hu-PBL-SCID mice immunized with virus-pulsed DCs generated in the presence of IFN were capable of recognizing virtually all the HIV-1 proteins detectable by Western blot analysis using a human positive control serum (Fig. 7 C). Notably, sera from immunized xenochimeras showing high levels of anti-gp 41 antibodies effectively neutralized HIV-1 infection of activated human PBLs in vitro (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Potent in vivo primary antibody response to HIV-1 in hu-PBL-SCID mice immunized with autologous DCs generated in the presence of CIFN/GM-CSF and pulsed with inactivated HIV-1. (A) Human anti–HIV-1/gp41 antibodies (total Ig) in sera from hu-PBL-SCID mice immunized and boosted (7 d later) with 1.5 × 106 DCs pulsed (2 h at 37°C) with AT-2–inactivated HIV-1. Each bar represents the mean of values obtained in two distinct experiments (eight mice in total). CTR, sera from mice reconstituted with hu-PBLs and injected with DCs generated in the presence of IFN/GM-CSF, not pulsed with HIV-1. (B) Characterization of the Ig isotype of anti-gp41 antibodies in sera from immunized and control hu-PBL-SCID mice. (C) Western blot analysis of antibodies against HIV-1 proteins using pooled sera from immunized hu-PBL-SCID mice. Sera from three mice for each group were pooled. Results from two different experiments (Exp.) are shown. Western blot analysis was performed as described in Materials and Methods. CTR(−), sera from mice reconstituted with hu-PBLs and injected with DCs generated in the presence of IFN/GM-CSF, not pulsed with HIV-1; CTR(+), positive human serum.

Discussion

In this study, we have reported that type I IFNs induce a rapid differentiation of freshly isolated GM-CSF–treated human monocytes into short-lived DCs endowed with potent functional activities both in vitro and in vivo, using the hu-PBL-SCID mouse model. The comparison of DCs generated in the presence of IFN/GM-CSF with those obtained after the standard IL-4/GM-CSF treatment revealed that type I IFN was definitively superior in inducing a rapid and stable differentiation process and in conferring to DCs a full functional activity to trigger a potent primary human immune response both in vitro and in hu-PBL-SCID mice. In particular, IFN induced an early detachment of monocytes from culture plates, paralleled by rapid acquisition of high levels of CD40, CD54, CD80, CD86, and HLA-DR molecules within 3 d, whereas IL-4/GM-CSF–treated monocytes required at least 6 d to fully acquire the immature DC phenotype. Of interest, a remarkable percentage of CD83-expressing DCs was observed in IFN-treated cultures, but not in IL-4–stimulated cells. Notably, an upregulation of CD83 expression by type I IFN has been reported, under very different experimental conditions, by Luft et al. using DCs generated from CD34+ progenitor cells 17 and recently by Radvanyi et al. 19. However, the novel finding concerning the CD83 induction by IFN reported in our study consists in the fact that the expression of this marker was acquired as early as 3 d after cytokine treatment, without any further treatment such as TNF 19 or LPS. We also found that CD83 expression was invariably associated with higher levels of HLA-DR and CD86. Notably, the fact that IFN/GM-CSF–treated cells had acquired a final commitment towards mature DC phenotype was suggested by the finding that upon cytokine removal, IFN/GM-CSF–treated cultures retained the DC phenotype, without adhering to the flask surface, whereas IL-4/GM-CSF–treated DCs reacquired the macrophage characteristics and readily readhered to culture flasks within 3 d, unless preventively stimulated to terminally differentiate. Of interest, the rapid differentiation observed in our IFN-treated cultures is reminiscent of an in vitro transendothelial trafficking model, in which immature DCs arose from monocytes within 2 d 4.

In all of the experimental conditions reported in this study, the maturation effects induced by type I IFN proved to be superior to those achieved by the IL-4/GM-CSF combination, as evaluated by FACS® analysis of antigen expression as well as by both MLR assays with allogeneic PBLs, and lymphocyte proliferation responses to autologous antigen-pulsed DCs. Three different preparations of type I IFNs (CIFN, IFN-α2b, and IFN-β) exhibited comparable effects, emphasizing the general involvement of these prototypic cytokines in the process of DC maturation/activation from monocytes.

In this study, we have also reported that type I IFN induces IL-15 mRNA expression and IL-15 secretion in GM-CSF–treated DC cultures. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report showing IL-15 induction by type I IFN in monocyte-derived DCs. Notably, Zhang et al. 33 had shown that type I IFN can induce IL-15 production in mouse macrophages. IL-15 is a recently identified pleiotropic cytokine produced by a wide variety of cells and tissues. This cytokine has been shown to act as a chemoattractant for T cells 34, favoring APC–T cell interaction and enhancing the generation of cytotoxic T cells 35. IL-15 increases IFN-γ production by NK and activated T cells 36 and strongly synergizes with IL-12 for IFN-γ production by upregulating IL-12Rβ1 expression on CD4+ T cells 37. IL-15 mRNA has recently been shown to be restricted to the CD83+ fraction of monocyte-derived DCs at late stages of DC culture 38. In fact, DC activation is generally needed to induce IL-15 mRNA expression in IL-4/GM-CSF–cultured DCs. At the protein level, IL-15 production by DCs has been reported to be low, unless triggered by phagocytic activity or cellular interactions 38. In light of all this and of the recently considered involvement of IL-15 33 in the in vivo expansion and survival of CD8+ memory T cells in mice exposed to type I IFN 12, we may assume that IL-15 secretion induced by type I IFN in DCs can represent an important event in the adjuvant activity of IFN for the proliferation and persistence of memory T cells in response to viral infections. Of interest, IFN-treated DCs induced a strong Th1-biased response, as evaluated by the overall cytokine production in allogeneic MLR assays as well as in proliferation assays with HIV-1–pulsed DCs. In particular, DCs generated in the presence of IFN/GM-CSF showed a potent ability to take up, process, and present inactivated HIV-1 to autologous T lymphocytes in vitro, which was clearly superior to that observed using DCs cultured with IL-4/GM-CSF. On the basis of these in vitro results, we decided to evaluate the capability of HIV-1–pulsed DCs generated in the presence of either IFN/GM-CSF or IL-4/GM-CSF to elicit a primary human immune response in vivo, by using SCID mice reconstituted with autologous PBLs. The hu-PBL-SCID mouse model 20 has been widely used for a variety of studies on pathogenesis 39 40 41 and therapy 25 of viral infections, especially using HIV-1. However, the generation of a primary human immune response in the chimeras has only been reported in a very few studies 29 30 31 32. We postulated, however, that an efficient immune response could be elicited in hu-PBL-SCID mice provided that appropriate antigen presentation could occur in vivo as a result of transfusion of autologous antigen–pulsed DCs at early times after reconstitution with hu-PBLs. Remarkably, we found that immunization of hu-PBL-SCID mice with IFN/GM-CSF–cultured autologous DCs pulsed with AT-2–inactivated HIV-1 resulted in the generation of potent primary immune response towards HIV-1, as evaluated by the detection of specific human antibodies against the whole spectrum of viral proteins (Fig. 7). At 7 d after immunization, human antibodies proved to be mostly IgM, whereas HIV-1–specific IgG1 antibodies were detected at 2 wk, suggesting a Th1-like response. This may reflect the DC capability of promoting both the generation of IgM response by naive B cells 42 and IL-10–independent IgG1 isotype switching 43. Notably, the antibodies detected in the sera of mice injected with DCs generated in the presence of IFN had a potent neutralizing activity in vitro against HIV-1. The levels of human antibodies to HIV-1 were consistently higher in hu-PBL-SCID mice injected with DCs generated in the presence of type I IFN compared with those detected in the xenochimeras transplanted with the corresponding virus-pulsed DCs developed in the presence of IL-4.

Intriguingly, even though DCs generated in the presence of IFN showed an enhanced functional activity both in vitro (persisting for at least 6 d) and in vivo (in the hu-PBL-SCID mouse model), a considerable percentage of the IFN-treated cells underwent apoptosis at 5 d of culture. Comparative RT-PCR analysis revealed a marked induction of TRAIL expression in IFN/GM-CSF–treated DCs. Notably, both TRAIL and functionally active receptors TRAIL-R1 and R2 were upregulated in response to LPS treatment. Of interest, the TRAIL expression in DCs generated in the presence of IFN/GM-CSF proved to be functionally important in inducing apoptosis of target cells (Fig. 4 D). In addition to IL-15 induction and CD83 upregulation, TRAIL upregulation represents an additional intriguing similarity with the effects induced by LPS in DCs. We speculate that some common signal transduction pathways can be induced by both IFN and LPS, leading to DC maturation. Considerable amounts of IFN (500 U/ml) were secreted after LPS stimulation of IL-4/GM-CSF–cultured DCs. Further studies are needed to clarify whether the IFN secreted by DCs in response to LPS can play some role in the terminal maturation of DCs.

Our results suggest the following scenario of events, with potential new implications for vaccine research. As DCs are the key players in the induction of the immune response, a rapid availability of mature DCs at specific sites is of crucial importance for an effective immune control against infections. Large amounts of type I IFN are locally produced by specific cell types, such as natural IFN-producing cell (NIPC)/pDC2 8 9, thus favoring DC development from monocytes. Locally produced type I IFN might protect T cells from antigen-induced apoptosis 14 15 and induce IL-15 production by DCs, thus favoring the proliferation of certain T cell subsets 12 33. Likewise, type I IFN can also inhibit antigen-induced apoptosis of B cells 44, thus promoting survival of antibody producing cells and enhancing humoral immune response. The IFN-induced upregulation of TRAIL expression may play a dual role: to induce a suicide of activated DCs, as suggested by apoptosis induction, and to induce apoptosis of virus-infected or tumor cells, which have been reported to be susceptible to TRAIL-induced apoptosis (23; Fig. 4 D). Both of these events might be beneficial for an efficient self-controlling host immune response against infections, and the IFN-mediated apoptosis of DCs may represent a natural feedback mechanism to limit Th1 response, thus avoiding subsequent tissue injury. However, the induction of TRAIL-mediated apoptosis of virus-infected or tumor cells by DC generated by IFN exposure may also enhance specific immunity. In fact, DCs have been shown to take up apoptotic bodies from dying cells and cross-prime cytotoxic CD8+ T cells 45. Thus, the IFN/DC-mediated apoptosis of virus-infected or tumor cells may favor the direct priming of the CD8+ T cell response against viral or tumor antigens.

There are several important implications and perspectives stemming from the results described above. Viruses or other stimuli capable of inducing type I IFN (such as poly-I:C or LPS) and CD40L, which also induce IFN production by IL-4/GM-CSF monocyte-derived DCs (our unpublished observations), are the strongest inducers of maturation/activation of DCs. On the basis of the results described above, it is reasonable to assume that the activation of the IFN system can represent the early important mechanism involved in the maturation/induction of DCs in response to virus infection and possibly to other invading pathogens or tumors.

Type I IFNs are the most used cytokines in patients with viral and neoplastic diseases, even though the in vivo mechanisms underlying the considerable clinical response are still poorly understood. Notably, the current clinical use of these cytokines does not yet imply the rationale of their use as vaccine adjuvants. The results of this study, together with an ensemble of data recently obtained by several groups 10 46, indicate that type I IFNs can represent powerful natural adjuvants for the development of novel vaccination strategies against virus infections and tumors. Finally, in addition to these practical perspectives for vaccine development, the elucidation of the self-controlling mechanism underlying the “alliance” between DCs and type I IFN represents a crucial step in understanding the basis of the early immune response to infection and underlines the importance of these cytokines as the natural bridge system connecting innate and adaptive immunity.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Ferrantini, D. Tough, D. Mosier, T. Tüting, A Mantovani, and I. Gresser for helpful comments and discussion. We are grateful to Cinzia Gasparrini and Anna Ferrigno for excellent secretarial assistance.

This work was supported in part by the European Community (contract B104-CT98-0466), the Italian Association for Cancer Research, and the “Italian Project on AIDS” (Istituto Superiore di Sanità–Ministry of Health contract 10A/L, 1999).

Footnotes

S.M. Santini and C. Lapenta contributed equally to this work.

Abbreviations used in this paper: AT, aldrithiol; CIFN, consensus IFN; DC, dendritic cell; ELISPOT, enzyme-linked immunospot; GFP, green fluorescent protein; hu, human; RT, reverse transcription; s, soluble; TRAIL, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand.

References

- Steinman R.M. The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1991;9:271–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella M., Sallusto F., Lanzavecchia A. Origin, maturation, and antigen-presenting function of dendritic cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1997;9:10–16. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banchereau J., Steinman R.M. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph G.J., Beaulieu S., Lebecque S., Steinman R.M., Muller W.A. Differentiation of monocytes into dendritic cells in a model of transendothelial trafficking. Science. 1998;282:480–483. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5388.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belardelli F., Vignaux F., Proietti E., Gresser I. Injection of mice with antibody to interferon renders peritoneal macrophages permissive for vesicular stomatitis virus and encephalomyocarditis virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:602–606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.2.602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belardelli F. Role of interferons and other cytokines in the regulation of the immune response. APMIS (Acta. Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. Scand.) 1995;103:161–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1995.tb01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biron C.A., Nguyen K.B., Pien G.C., Cousens L.P., Salazar-Mather T.P. Natural killer cells in antiviral defensefunction and regulation by innate cytokines. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1999;17:189–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegal F.P., Kadowaki N., Shodell M., Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P.A., Shah K., Ho S., Antonenko S., Liu Y.J. The nature of the principal type I interferon-producing cells in human blood. Science. 1999;284:1835–1837. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella M., Jarrossay D., Facchetti F., Alebardi O., Nakajima H., Lanzavecchia A., Colonna M. Plasmacytoid monocytes migrate to inflamed lymph nodes and produce large amounts of type I interferon. Nat. Med. 1999;5:919–923. doi: 10.1038/11360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belardelli F., Gresser I. The neglected role of type I interferon in the T cell responseimplications for its clinical use. Immunol. Today. 1996;17:369–372. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)10027-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelman F.D., Svetic A., Gresser I., Snapper C., Holmes J., Trotta P.P., Katona I.M., Gause W.C. Regulation by interferon α of immunoglobulin isotype selection and lymphokine production in mice. J. Exp. Med. 1991;174:1179–1188. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tough D.F., Borrow P., Sprent J. Induction of bystander T cell proliferation by viruses and type I interferon in vivo . Science. 1996;272:1947–1950. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S., Zhang X., Tough D.F., Sprent J. Type I interferon-mediated stimulation of T cells by CpG DNA. J. Exp. Med. 1998;188:2335–2342. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrack P., Kappler J., Mitchell T. Type I interferons keep activated T cells alive. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:521–530. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.3.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matikainen S., Sareneva T., Ronni T., Lehtonen A., Koskinen P.J., Julkunen I. Interferon-α activates multiple STAT proteins and upregulates proliferation-associated IL-2Rα, c-myc, and pim-1 genes in human T cells. Blood. 1999;93:1980–1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belardelli F., Ferrantini M., Santini S.M., Baccarini S., Proietti E., Colombo M.P., Sprent J., Tough D.F. Induction of in vivo proliferation of long-lived CD44hi CD8+ T cells after injection of tumor cells expressing IFN-α into syngeneic mice. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5795–5802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luft T., Pang K.C., Thomas E., Hertzog P., Hart D.N.J., Trapani J., Cebon J. Type I IFNs enhance the terminal differentiation of dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 1998;161:1947–1953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette R.L., Hsu N.C., Kiertscher S.M., Park A.N., Tran L., Roth M.D., Gaspy J.A. Interferon-α and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor differentiate peripheral blood monocytes into potent antigen-presenting cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1998;64:358–367. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radvanyi L.G., Banerjee A., Weir M., Messner H. Low levels of interferon-alpha induce CD86 (B7.2) expression and accelerate dendritic cell maturation from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Scand. J. Immunol. 1999;50:499–509. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosier D.E., Gulizia R.J., Baird S.M., Wilson D.B. Transfer of a functional human immune system to mice with severe combined immunodeficiency. Nature. 1988;335:256–259. doi: 10.1038/335256a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alton K., Stabinsky Y., Richards R., Ferguson B., Goldstein L., Altrock B., Miller L., Stebbings N. Production, characterization and biological effects of recombinant DNA derived human IFN-α and IFN-γ analogs. In: De Maeyer E., Schellenkens H., editors. The Biology of the Interferon System. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1983. pp. 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Rizza P., Santini S.M., Logozzi M., Lapenta C., Sestili P., Gherardi G., Lande R., Spada M., Parlato S., Belardelli F., Fais S. T-cell dysfunction in hu-PBL-SCID mice infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) shortly after reconstitutionin vivo effects of HIV on highly activated human immune cells. J. Virol. 1996;70:7958–7964. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7958-7964.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith T.S., Wiley S.R., Kubin M.Z., Sedger L.M., Maliszewski C.R., Fanger N.A. Monocyte-mediated tumoricidal activity via the tumor necrosis factor–related cytokine, TRAIL. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:1343–1354. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.8.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossio J.L., Esser M.T., Suryanarayana K., Schneider D.K., Bess J.W., Jr., Vasquez G.M., Wiltrout T.A., Chertova E., Grimes M.K., Sattentau Q. Inactivation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity with preservation of conformational and functional integrity of virion surface proteins. J. Virol. 1998;72:7992–8001. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7992-8001.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapenta C., Santini S.M., Proietti E., Rizza P., Logozzi M., Spada M., Parlato S., Fais S., Pitha P.M., Belardelli F. Type I interferon is a powerful inhibitor of in vivo HIV-1 infection and preserves human CD4+ T cells from virus-induced depletion in SCID mice transplanted with human cells. Virology. 1999;263:78–88. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallusto F., Lanzavecchia A. Efficient presentation of soluble antigen by cultured human dendritic cells is maintained by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus interleukin 4 and downregulated by tumor necrosis factor alpha. J. Exp. Med. 1994;179:1109–1118. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann P., Rubio M., Nakajima T., Delespesse G., Sarfati M. IFN-alpha priming of human monocytes differentially regulates gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria-induced IL-10 release and selectively enhances IL-12p70, CD80, and MHC class I expression. J. Immunol. 1998;161:2011–2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanger N.A., Maliszewski C.R., Schooley K., Griffith T.S. Human dendritic cells mediate cellular apoptosis via tumor necrosis factor–related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) J. Exp. Med. 1999;190:1155–1164. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.8.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker W., Brewer J.M., Alexander J. Lipid vesicle-entrapped influenza A antigen modulates the influenza A-specific human antibody response in immune reconstituted SCID-human mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 1996;26:1664–1667. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker W., Roberts C.W., Brewer J.M., Alexander J. Antibody responses to Toxoplasma gondii antigen in human peripheral blood lymphocyte-reconstituted severe-combined immunodeficient mice reproduce the immunological status of the lymphocyte donor. Eur. J. Immunol. 1995;25:1426–1430. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M.A., Brams P. High titer, prostate specific antigen-specific human IgG production by hu-PBL-SCID mice immunized with antigen-mouse IgG2a complex-pulsed autologous dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 1998;161:5772–5780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delhem N., Hadida F., Gorochov G., Carpentier F., de Cavel J.P., Andreani J.F., Autran B., Cesbron J.Y. Primary Th1 cell immunization against HIVgp160 in SCID-hu mice coengrafted with peripheral blood lymphocytes and skin. J. Immunol. 1998;161:2060–2069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Sun S., Hwang I., Tough D.F., Sprent J. Potent and selective stimulation of memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells in vivo by IL-15. Immunity. 1998;8:591–599. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80564-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson P.C., Liew F.Y. Chemoattraction of human blood T lymphocytes by interleukin-15. J. Exp. Med. 1995;181:1255–1259. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuniyoshi J.S., Kuniyoshi C.J., Lim A.M., Wang F.Y., Bade E.R., Lau R., Thomas E.K., Weber J.S. Dendritic cell secretion of IL-15 is induced by recombinant huCD40LT and augments the stimulation of antigen-specific cytolytic T cells. Cell. Immunol. 1999;193:48–58. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1999.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borger P., Kauffman H.F., Postma D.S., Esselink M.T., Vellenga E. Interleukin-15 differentially enhances the expression of interferon-gamma and interleukin-4 in activated human (CD4+) T lymphocytes. Immunology. 1999;96:207–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00679.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avice M.N., Demeure C.E., Delespesse G., Rubio M., Armant M., Sarfati M. IL-15 promotes IL-12 production by human monocytes via T cell-dependent contact and may contribute to IL-12-mediated IFN-gamma secretion by CD4+ T cells in the absence of TCR ligation. J. Immunol. 1998;161:3408–3415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonuleit H., Wiedemann K., Muller G., Degwert J., Hoppe U., Knop J., Enk A.H. Induction of IL-15 messenger RNA and protein in human blood-derived dendritic cellsa role for IL-15 in attraction of T cells. J. Immunol. 1997;158:2610–2615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosier D.E., Gulizia R.J., Baird S.M., Wilson D.B., Spector D.H., Spector S.A. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of human PBL-SCID mice. Science. 1991;25:791–794. doi: 10.1126/science.1990441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosier D.E., Gulizia R.J., MacIsaac P.D., Torbett B.E., Levy J.A. Rapid loss of CD4+ T cells in human-PBL-SCID mice by noncytopathic HIV isolates. Science. 1993;260:689–692. doi: 10.1126/science.8097595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fais S., Lapenta C., Santini S.M., Spada M., Parlato S., Logozzi M., Rizza P., Belardelli F. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains R5 and X4 induce different pathogenic effects in hu-PBL-SCID mice, depending on the state of activation/differentiation of human target cells at the time of primary infection. J. Virol. 1999;73:6453–6459. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6453-6459.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B., Massacrier C., Vanbervliet B., Fayette J., Briere F., Banchereau J., Caux C. Critical role of IL-12 in dendritic cell-induced differentiation of naive B lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 1998;161:2223–2231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B., Barthelemy C., Durand I., Liu Y.J., Caux C., Briere F. Toward a role of dendritic cells in the germinal center reactiontriggering of B cell proliferation and isotype switching. J. Immunol. 1999;162:3428–3436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su L., David M. Inhibition of B cell receptor-mediated apoptosis by IFN. J. Immunol. 1999;162:6317–6321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert M.L., Sauter B., Bhardwaj N. Dendritic cells acquire antigen from apoptotic cells and induce class I-restricted CTLs. Nature. 1998;392:86–89. doi: 10.1038/32183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrantini M., Belardelli F. Gene therapy of cancer with interferonlessons from tumor models and perspectives for clinical applications. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2000;In press doi: 10.1006/scbi.2000.0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]