Abstract

Vascular damage induced by trauma, inflammation, or infection results in an alteration of the endothelium from a nonactivated to a procoagulant, vasoconstrictive, and proinflammatory state, and can lead to life-threatening complications. Here we report that activation of the contact system by Salmonella leads to massive infiltration of red blood cells and fibrin deposition in the lungs of infected rats. These pulmonary lesions were prevented when the infected animals were treated with H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-chloromethylketone, an inhibitor of coagulation factor XII and plasma kallikrein, suggesting that inhibition of contact system activation could be used therapeutically in severe infectious disease.

Keywords: bradykinin, factor XII, high molecular weight kininogen, plasma kallikrein, protease inhibitor

Introduction

Hemostasis is a sensitive and tightly regulated process, involving vascular endothelium and blood cells as well as factors of the coagulation and fibrinolytic cascades. During infection, inflammatory mediators of the microbe and/or host may induce life-threatening complications by modulating the equilibrium between the procoagulant and anticoagulant status of the host 1. The activation of the intrinsic pathway of coagulation, also termed contact system, during infection is thought to contribute to the severity of the disease (for a review, see reference 2). The contact system belongs to the typical serine proteinase–triggered cascades, which are initiated by limited proteolysis 3. Upon activation, the system is involved in the regulation of different proinflammatory and defense mechanisms 4. In severe infections, low levels of contact factors (factor [F] XII and H-kininogen [HK]) correlate with a fatal outcome of the disease 5. Most strains of Salmonella typhimurium bacteria can express so-called thin, aggregative fimbriae (for simplicity, referred to as fimbriae in the following text) on their surface, whereas very similar structures in Escherichia coli are designated curli 6 7 8. These fibrous proteins interact with several host proteins such as contact system factors, fibrinogen, fibronectin, laminin, major histocompatibility complex class I antigens, and plasminogen 9 10 11 12. Recently, it was shown that curli organelles from E. coli trigger the induction of cytokines IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α in peripheral blood monocytes, suggesting a possible role for these organelles in the initiation of proinflammatory reactions during E. coli sepsis 13. The assembly of contact system factors on the surface of fimbriae-expressing bacteria leads to the release of the inflammatory mediator bradykinin. Furthermore, the binding of contact factors and fibrinogen to fimbriae results in the depletion of these proteins in plasma and causes a hypocoagulatory state 9. These mechanisms should contribute to symptoms of severe Salmonella and E. coli infections, i.e., plasma leakage into the extravascular space, hypovolemic hypotension, and formation of microthrombi.

Extraintestinal salmonellosis is most common among immunosuppressed, debilitated patients with underlying diseases such as AIDS, leukemia, lymphoma, inflammatory bowel disease, schistosomiasis, and macrophage dysfunction 14. The most frequent isolates from patients with extraintestinal salmonellosis are the fimbriae-expressing strains S. typhimurium and Salmonella enteritidis 7 8 15 16 17. In this investigation, we show that inhibition of the contact system downregulates inflammatory reactions and coagulation disorders induced by fimbriae-expressing S. typhimurium.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions.

The S. typhimurium SR-11 X4666 strain (SR11B) was used. The CsgA and CsgB mutant strains (SR-11 X4666, csgA::Tn1731; SR-11 X4666, csgB::Tn1721) were produced by transposon mutagenesis 18. Bacteria were grown on colonization factor antigen agar 19 at 37°C overnight, washed, and resuspended in 0.15 M NaCl, 0.03 M NaH2PO4, pH 7.2, containing: 0.02% (wt/vol) NaN3 and 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween (buffer A); 13 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.4 (buffer B); 15 mM Hepes, 135 mM NaCl, 50 μM ZnCl2, pH 7.4 (buffer C); or 0.15 M NaCl, 4 mM KCl, and 2 mM CaCl2, pH 6.0 (buffer D).

Sources of Proteins.

Coagulation factors F VII, F IX, F X, F XI, F XII, prothrombin, and von Willebrand factor, were from Haematologic Technologies Inc. F V, HK, and plasma kallikrein (PK) were from Enzymes Research Laboratories Ltd., and fibrinogen was from Sigma-Aldrich. Proteins were iodinated by the chloramin-T method of Fraker and Speck 20. The H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-chloromethylketone (CMK) peptide was from Bachem Feinchemikalien AG.

Plasma.

Blood samples were drawn from healthy volunteers in Vacutainer tubes (Becton Dickinson) containing 1:9 vol, 129 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.4, or in tubes (Terumo) containing sodium heparin (1,500 USP units sodium heparin/10 ml). Drawn blood was pooled and centrifuged at 2,500 g for 15 min. The pellet was removed and plasma samples were stored at −20°C.

Binding Assays.

Bacteria resuspended in buffer A were adjusted to a final count of 2 × 109 cells/ml. Binding assays were performed as described previously 9. In brief, 200 μl of cell suspensions was incubated with 25 μl (8 × 105 cpm/ml) radioactively labeled protein for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were washed with 1 ml buffer A, followed by a centrifugation step (1,500 g, 15 min). The supernatant was removed and the radioactivity in the pellet was counted. Binding was expressed as the percentage of bound versus total radioactivity.

Clotting Assays.

The clotting time was measured in a coagulometer (Amelung). 30 μl of bacteria suspended in buffer B (0.1 –2 × 1010 cells/ml) was incubated with 100 μl human citrate–treated plasma for 1 min (activated partial thromboplastin time [aPTT]) or 2 min (prothrombin [PT]) at 37°C. Clotting was initiated by the addition of 100 μl Platelin LS (aPTT kit; Organon Teknica) for 200 s at 37°C followed by the addition of 100 μl 25 mM CaCl2 (aPTT) or 200 μl Tromboplastin-XS with calcium (PT; Sigma-Aldrich). Alternatively, 0.5 ml citrate-treated plasma was preincubated with 0.5 ml of a solution containing 1010 bacteria/ml in the presence or absence of 50 μg/ml H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK (final concentration). After incubation for 15 min at room temperature, bacteria were removed by centrifugation (2,500 g, 10 min), and the resulting supernatants were analyzed as described above.

Chromogenic Substrate Assay.

SR11B bacteria were washed and adjusted to 2 × 1010 bacteria/ml in buffer C. Equal volumes (0.5 ml) of bacteria and citrate-treated plasma were incubated for 15 min at room temperature in the presence or absence of 50 μg/ml H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK (final concentration). The samples were then washed three times in buffer C and resuspended in 0.25 ml of a buffer containing 1 mM of the chromogenic substrate S-2302 (H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-pNA·2HCl specific for F XII and PK) or S-2238 (H-D-Phe-Pip-Arg-pNA·2HCl specific for thrombin). Both substrates were from Chromogenix. After incubation for 30 min at room temperature, the bacteria were centrifuged at 8,000 g for 2 min and the absorbance of the supernatants at 405 nm was measured.

Determination of Bradykinin.

Bacteria were washed and adjusted to 2 × 1010 cells/ml in buffer C. Equal volumes (0.5 ml) of bacteria and fresh heparin-treated plasma were incubated for 15 min at room temperature in the presence or absence of 100 μg/ml H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK (final concentration). The samples were then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 1 min and resuspended in the same buffer, followed by three washing steps, and finally resuspended in 0.25 ml. After 15 min of incubation at room temperature, the bacteria were removed by centrifugation (10,000 rpm, 1 min) and the bradykinin concentration in the reaction mixture was quantified by the Markit-A kit (Dainippon Pharmaceutical Co.) as described 21.

Animal Experiments.

Adult Wistar rats, weighing 250–275 g, were anesthetized with equal parts of fluanison/fentanyl (10/0.2 mg/ml Hypnorm; Janssen Pharmaceutica) and midazolam (5 mg/ml Dormicum; Hoffman-La Roche) diluted 1:1 with sterile water (0.2 ml/100 g body wt intramuscularly). The trachea was cannulated to facilitate spontaneous breathing. Catheters were placed in the left jugular vein for intravenous administration of bacterial suspensions, and in the right carotid artery for systemic blood pressure recordings. Rats were given an intravenous injection of 250 μl of a bacterial suspension containing 2 × 1010 cells/ml in buffer D. Alternatively, 100 μl of a solution containing 4 mg/ml H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK in buffer D was intravenously injected into rats and after 10 min, 350 μl of a mixture containing 400 μg peptide and 5 × 109 bacteria was administrated via the same route. 30 min after injection of bacteria, blood samples were taken by puncture of the heart. Thereafter, rats were killed by an overdose of anesthesia and the lungs were removed. The animal experiments were approved by the regional ethical committee for animal experimentation.

Histochemistry.

After killing, lungs were rapidly removed by surgery and fixed at 4°C for 24 h in buffered 4% formalin (pH 7.4; Kebo). Tissues were dehydrated and imbedded in paraffin (Histolab Products AB), cut into 4-μm sections, and mounted. After removal of the paraffin, tissues were stained with Mayers hematoxylin (Histolab Products AB) and eosin (Surgipath Medical Industries, Inc.).

Scanning Electron Microscopy.

Clots or lung tissue were fixed in 2% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde, 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, and 0.1 M sucrose, pH 7.2, for 2 h at 4°C, and subsequently washed with 0.15 M cacodylate, pH 7.2. Clots and tissue samples were postfixed with 1% (wt/vol) osmium tetroxide and 0.15 M sodium cacodylate, pH 7.2, for 1 h at 4°C, washed, and stored in cacodylate buffer. Before scanning electron microscopy, samples were dehydrated with an ascending ethanol series from 50 to 100% ethanol (10 min per step). They were then subjected to critical-point drying in liquid carbon dioxide with 100% ethanol as the intermediate solvent, mounted on aluminum holders, sputtered with 50 nm palladium/gold, and examined in a Jeol JSM-350 scanning electron microscope.

Statistics.

Results are expressed as mean values ± SD unless otherwise stated. Differences between groups concerning bradykinin release, hemorrhagic lung lesions, and fibrin deposition were analyzed by the one-tailed test for differences between means. The following a priori null hypotheses were tested: H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK treatment does not alter bradykinin release from human plasma, or does not prevent hemorrhagic lesions and fibrin deposition in rat lungs induced by Salmonella. The null hypothesis was rejected and statistical significance was assumed when P < 0.05.

Results

Coagulation Factors Bind to Fimbriated Salmonella.

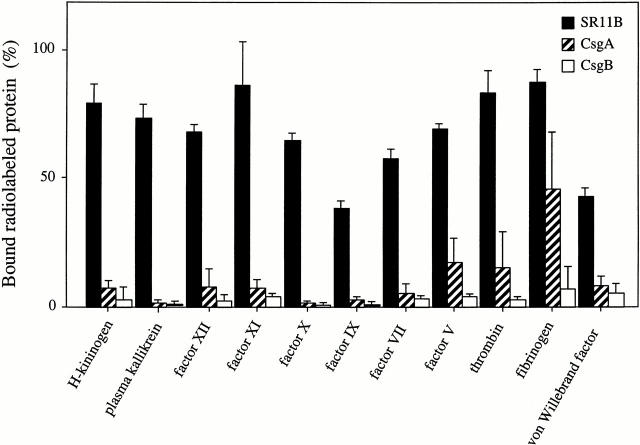

To explore a potential role for fimbriated bacteria in coagulation disorders and inflammation, we assessed the binding of various radiolabeled coagulation factors to S. typhimurium, strain SR11B. The isogenic mutant strains CsgA and CsgB that do not express fimbriae were used as controls. Fig. 1 shows that all tested factors had affinity for SR11B bacteria, whereas, with the exception of fibrinogen binding to CsgA bacteria, the mutant strains did not bind the various proteins. The interactions between SR11B bacteria and coagulation factors were not dependent on phospholipids; however, the binding was slightly increased when a buffer containing ZnCl2 (50 μM) was used (data not shown). After incubation of SR11B bacteria with plasma and careful washing, all coagulation factors could also be eluted from the bacterial surface and detected by Western blot analysis. In addition, after plasma incubation and washing, serine proteinase activity associated with the bacterial cell surface was increased as measured by specific chromogenic substrates (data not shown).

Figure 1.

The binding of radiolabeled coagulation factors to fimbriated Salmonella. 125I-labeled HK, PK, F XII, F XI, F X, F IX, F VII, F V, prothrombin, fibrinogen, or von Willebrand factor was incubated with suspensions of S. typhimurium strains SR11B, CsgA, or CsgB. Binding is expressed as the percentage of bound vs. total radioactivity. Data represent means ± SD of three experiments, each done in duplicate.

Fimbriated Bacteria Interfere with the Activation of the Intrinsic but Not the Extrinsic Pathway of Coagulation.

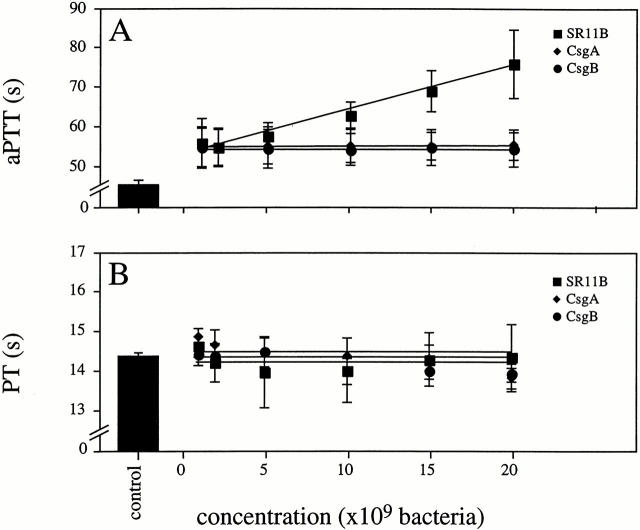

Based on the findings described above, it was investigated whether the interaction between SR11B bacteria and coagulation factors influenced the clotting properties of normal human plasma. Therefore, we tested the effect of SR11B on clot formation by measuring the aPTT and the PT. Fig. 2 A shows that the addition of SR11B bacteria to plasma prolonged clotting by the intrinsic pathway (aPTT) in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas the extrinsic pathway (PT) was not effected (Fig. 2 B). The ability of SR11B bacteria to attenuate the intrinsic pathway is due to absorption of contact factors and other coagulation factors such as F XII by fimbriae leading to a hypocoagulatory state, as described previously 9. The mutant strains CsgA and CsgB did not influence the clotting ability of plasma, neither of the intrinsic nor extrinsic pathway. The results demonstrate that the binding of coagulation factors to SR11B is mediated by fimbriae, resulting in impaired clot formation via the intrinsic pathway of coagulation.

Figure 2.

Effects of Salmonella on the clotting time. Normal human plasma was incubated with increasing concentrations of strains SR11B (▪), CsgA (♦), CsgB (•), or buffer alone (control) for 60 s. Clotting was initiated by adding kaolin and CaCl2 (A), or tissue factor (B). Data represent means ± SD of three experiments, each done in duplicate.

The Release of Bradykinin by Salmonella Is Blocked by an Inhibitor of F XII and PK.

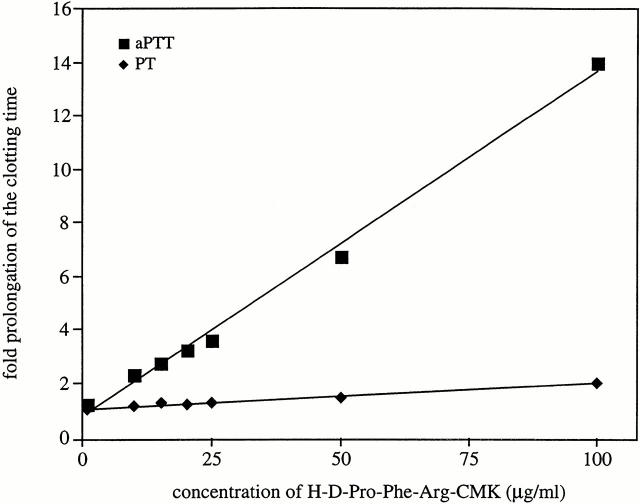

The synthetic peptide H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK is an inhibitor of F XII and PK 22 23, and when added to human plasma it caused an up to 14-fold prolongation of the aPTT, but had almost no influence on the PT (Fig. 3). The results emphasize its specificity for F XII/PK and the intrinsic pathway of coagulation.

Figure 3.

The effects of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK on the clotting time. Normal human plasma was incubated with increasing concentrations of the synthetic peptide H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK (1–100 μg/ml final concentration) for 60 s. Clotting was initiated by adding kaolin and CaCl2 (▪), or tissue factor (♦), and the clotting times are given as time-fold prolongation.

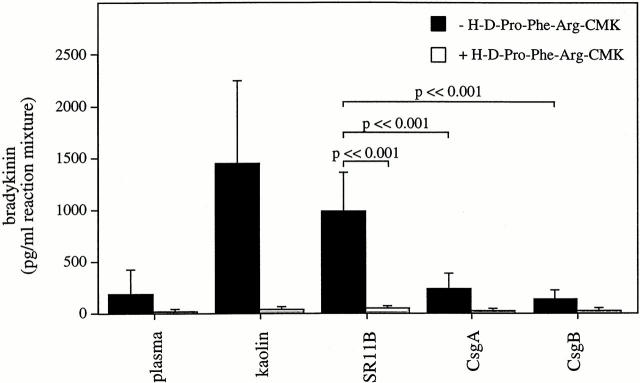

It was then tested whether the peptide could interfere with the bradykinin release induced by fimbriated Salmonella. Fig. 4 shows that such bacteria generate large amounts of bradykinin when added to human plasma, a release that was completely blocked in the presence of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK. Also, the effect of kaolin, a potent activator of the contact system, was blocked by the F XII/PK inhibitor. The mutant strains had no or only minor influence on bradykinin generation, and incubations with plasma alone or plasma plus the inhibitor served as additional controls (Fig. 4). In summary, the data demonstrate that fimbriated Salmonella in plasma activates the proinflammatory pathway of the contact system, i.e., kinin generation, and that this activation can be blocked by a specific inhibitor of F XII and PK.

Figure 4.

The ex vivo effects of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK on the generation of bradykinin by kaolin and Salmonella. Human plasma samples, in the absence or presence of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK (100 μg/ml final concentration), were incubated with kaolin or with strains SR11B, CsgA, or CsgB for 15 min. Plasma was removed by centrifugation and kaolin or bacteria were resuspended as described in Materials and Methods. After 15 min of incubation, the amount of bradykinin present in the reaction mixture was measured by a competitive ELISA. As a control, plasma was incubated in the absence of kaolin and bacteria. Data represent means ± SD of three experiments. P values between SR11B and CsgA or CsgB are indicated in the figure.

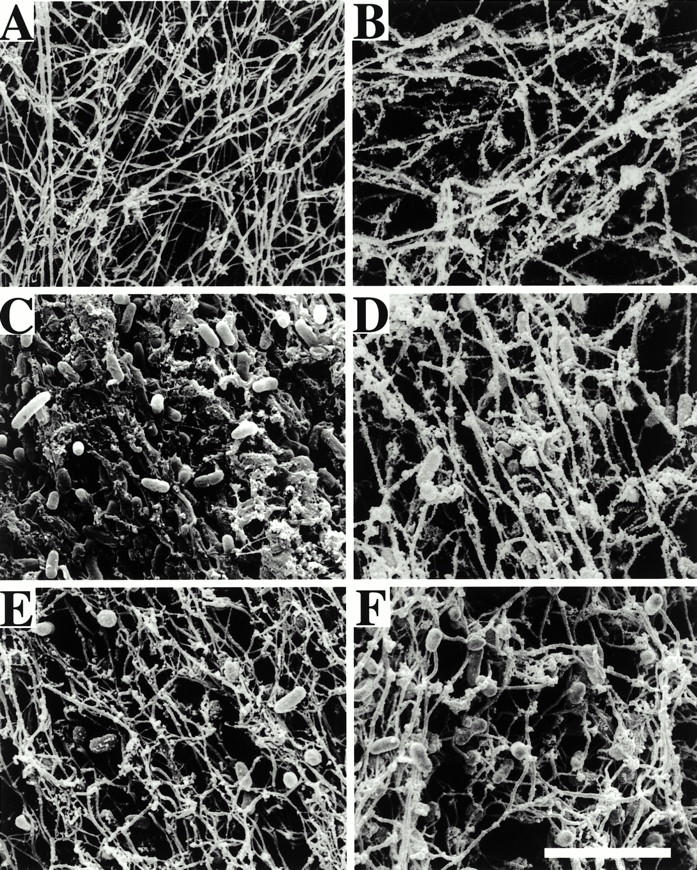

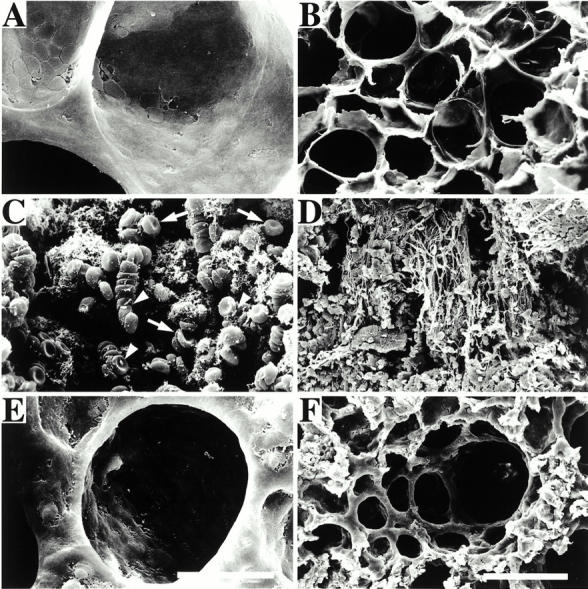

Electron Microscopical and Functional Analysis of Clots Formed in the Absence or Presence of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK.

To further investigate the ability of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK to interfere with the activation of the contact system by fimbriated bacteria, we studied the influence of the inhibitor on clot formation by scanning electron microscopy. As this method allows for analyzing surface topography in a three-dimensional way at high resolution, it appeared to be a suitable tool to visualize alterations in fibrin fibril architecture in clots formed in the presence or absence of bacteria. Clots induced in plasma by kaolin are built by long, polymerized fibrin fibrils forming an intact network (Fig. 5 A). The addition of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK to plasma did not influence this general architecture, but the clotting time was drastically prolonged (Fig. 5 B). Upon incubation of plasma with SR11B bacteria, the clot morphology changed. Bacteria were incorporated into the clot, the length and diameter of the fibrin fibrils were shortened, and an intact network was not established (Fig. 5 C). These findings are in line with previously reported data and are due to the absorption and activation of coagulation factors on the bacterial surface, resulting in an impaired clotting ability and hypocoagulative state 9. In contrast, the fibrin fibrils and network formation appeared to be normal when SR11B bacteria were added to plasma treated with H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK, although some bacteria were found adhering to the fibers (Fig. 5 D). The mutant strains CsgA (Fig. 5E and Fig. F) and CsgB (not shown) had no influence on the clot morphology.

Figure 5.

Scanning electron micrographs of clots from human plasma formed in the presence or absence of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK. Representative electron micrographs show clots formed in human plasma incubated with strains SR11B (C and D) and CsgA (E and F), in the absence (A, C, and E) or presence (B, D, and F) of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK. Plasma samples without bacteria served as controls (A and B). Scale bar, 5 μm.

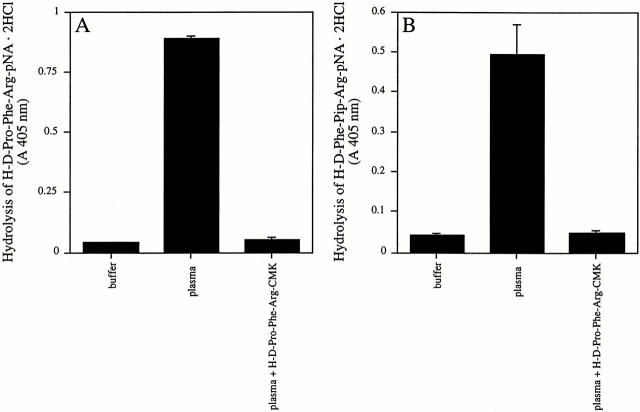

To investigate if the contact activation at the surface of SR11B influences other surface-bound coagulation factors, chromogenic substrates specific for F XII/PK or thrombin amidolytic activity were used. When SR11B bacteria were incubated with human plasma in the absence of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK, enhanced activity for F XII/PK was associated with bacterial surface compared with the control (Fig. 6 A). Similar results were obtained when the activity of thrombin was investigated (Fig. 6 B). However, no hydrolysis of the substrates for F XII/PK and thrombin was found when plasma was treated with H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK (Fig. 6A and Fig. B). Thus, the differences in the morphology of clots obtained from plasma incubated with SR11B bacteria in the absence or presence of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK can be explained by the contact system–triggered activation of the coagulation cascade on the bacterial surface leading to an activation of thrombin, probably followed by a degradation of bacterially bound fibrinogen.

Figure 6.

The activation of coagulation factors bound to SR11B bacteria in the absence or presence of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK. SR11B bacteria were preincubated with plasma in the absence or presence of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK (50 μg/ml final concentration) for 15 min at room temperature. As a control, bacteria were incubated with buffer alone. Bacteria were washed as described in Materials and Methods and resuspended in a buffer containing the chromogenic substrate H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-pNA·2HCl specific for F XII/PK (A) or H-D-Phe-Pip-Arg-pNA·2HCl specific for thrombin (B). After 30 min, bacteria were removed and the absorbance at 405 nm was determined.

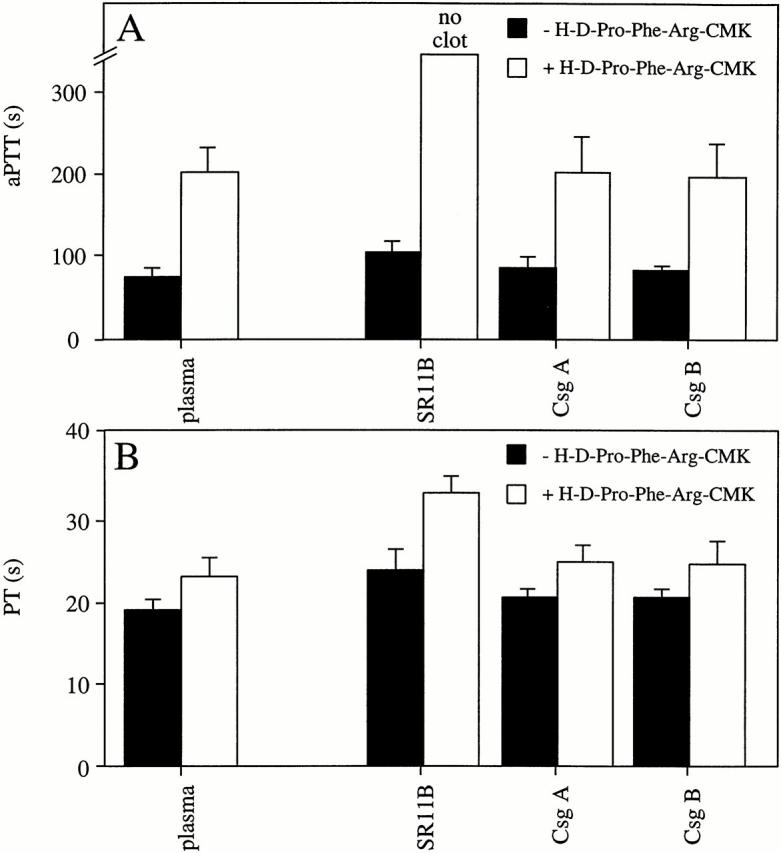

The effect of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK was also reflected in the clotting ability of plasma samples that had been treated with fimbriated bacteria. In these experiments, the assay was modified such that plasma in the absence or presence of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK was incubated with bacteria for 15 min, followed by a centrifugation step to remove the bacteria. This manipulation results in more extended clotting times compared with the experiments described above because the longer incubation time (15 min compared with 1 min) allows plasma proteins to adhere to the bacterial surface. The binding and subsequent depletion of various coagulation factors additionally disturb normal clotting of plasma 9. Bacteria were removed and the resulting supernatants were analyzed in the aPTT and PT tests. Incubation of plasma with buffer alone served as the control, and a concentration of the inhibitor was chosen (50 μg/ml) that induced an increase of ∼120 s of the aPTT compared with untreated plasma (Fig. 7 A). The absorption of plasma with SR11B bacteria led to a prolongation of the aPTT of ∼30 s. However, when H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK was first added to plasma followed by absorption, clot formation was completely blocked. In the absence of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK, the PT clotting time of plasma samples preabsorbed with SR11B bacteria was not prolonged for >5 s compared with untreated plasma (Fig. 7 B). Moreover, in the PT test the addition of the inhibitor to plasma followed by treatment with SR11B did not block fibrin clotting, though the clotting time was prolonged (32.6 ± 2.0 vs. 22.6 ± 2.2 s in plasma incubated with H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK). Plasma samples preabsorbed by CsgA or CsgB bacteria were not affected in either the aPTT or the PT test. Taken together, electron microscopical analysis and clotting assays suggest that the disturbances of normal clotting induced by fimbriated bacteria are overcome by H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK, as formation of bacteria containing fibrin deposits due to contact activation on the bacterial surface is abolished. The data also show that fimbriated bacteria fail to block the extrinsic pathway of coagulation and that this pathway remains functional in plasma, in the presence of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK.

Figure 7.

The effects of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK on the clotting of plasma preabsorbed with bacteria. Human plasma samples, in the absence or presence of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK (50 μg/ml final concentration), were incubated with strains SR11B, CsgA, or CsgB for 15 min. Bacteria were separated from plasma by centrifugation and the resulting supernatants were analyzed by the aPTT (A) or the PT (B) test. Data represent means ± SD of three experiments, each done in duplicate.

H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK Prevents Lung Damage in Rats Infected with Fimbriated Salmonella Bacteria.

In a series of experiments, a single bolus of SR11B bacteria was injected intravenously into anesthetized rats. Half of the animals were treated with H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK, and rats injected with vehicle alone served as controls. After injections, the blood pressure was monitored in two animals of each group. Within 30 min after infection, the blood pressure dropped 55 mmHg in both rats infected with SR11B, whereas the decline was 25 and 35 mmHg, respectively, in the two infected rats treated with the inhibitor. No significant differences of bradykinin levels were found in blood plasma samples from infected and control animals (data not shown). This is explained by the fact that kinins are rapidly metabolized by different peptidases such as kininase I, kininase II (also known as angiotensin 1–converting enzyme), and neutral endopeptidase, resulting in a half-life of bradykinin of ∼10 s in rats 24.

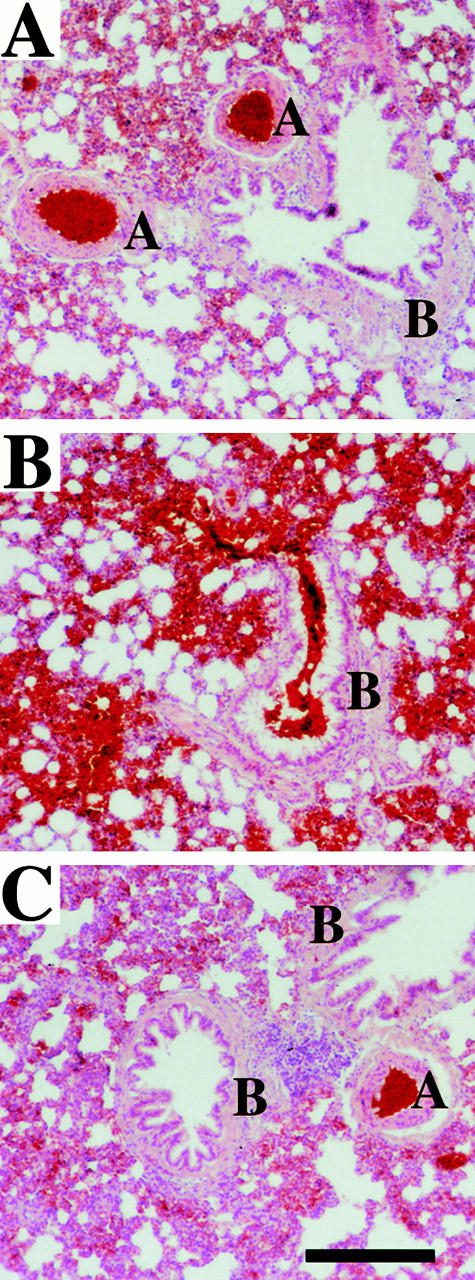

The extent of lung damage was analyzed by histochemical staining and light microscopy of tissue sections from infected and noninfected animals. Fig. 8 A depicts the intact alveolar architecture of an untreated control animal. Infection with SR11B gave rise to widespread hemorrhages and massive erythrocyte infiltration of lung parenchyma and bronchioles (Fig. 8 B); lesions were much less prominent in infected animals treated with H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK (Fig. 8 C). Thus, the ratio between damaged and undamaged tissue areas, quantified and summarized in Table , shows significantly less damage in the lungs of rats treated with H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK compared with nontreated animals.

Figure 8.

The histological analysis of rat lungs. Formalin-fixed sections of rat lungs were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The figure shows representative sections of lungs from an uninfected rat (A), a rat infected with SR11B bacteria (B), and a rat infected with SR11B bacteria and treated with H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK (C). Pulmonary arteries (A) and bronchioles (B) are indicated. Scale bar, 25 μm.

Table 1.

Hemorrhagic Lesions in Rat Lungs

| Animal | Buffer | SR11B | SR11B +H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | |

| 1 | 3.5 | 41.6 | 6.6 |

| 2 | 4.0 | 16.5 | 11.7 |

| 3 | 8.1 | 26.9 | 11.8 |

| 4 | 6.8 | 60.7 | 14.0 |

Eight rats were infected with SR11B bacteria, from which four were treated with H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK. Noninfected animals injected with buffer alone served as controls and four animals in each group were analyzed. The ratio of hemorrhagic area versus total area was determined by light microscopy in six randomly chosen lung tissue sections from each animal. Hemorrhagic lesions in control animals, considered as background, occur upon removal and preparation of lung tissue. The P value for the difference between lesions induced by SR11B in the absence or presence of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK is <0.001.

Lung tissue sections were analyzed by scanning electron microscopy, and representative samples from uninfected rats are shown in Fig. 9A and Fig. B. Micrographs of lungs from infected rats reveal that, in addition to the findings described above, the alveolar system exhibits extensive fibrin deposition (Fig. 9 C). Furthermore, bacteria are seen either incorporated in the fibrin network or adhering to erythrocytes (Fig. 9 D). These lesions were not found in the lungs of rats treated with H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK (Fig. 9E and Fig. F). Alveolar swelling was clearly less pronounced, but still also present in the treated rats. Table shows that administration of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK significantly reduces fibrin deposition and bacterial tissue invasion in all animals tested. Thus, the in vivo data suggest that activation of the contact system by fimbriated bacteria induces extravascular leakage, bleeding, and fibrin deposition in the lung. The results also demonstrate that these effects can be prevented by an F XII/PK inhibitor.

Figure 9.

Scanning electron microscopy of rat lungs. The figure shows micrographs of glutaraldehyde-fixed lungs from an uninfected rat (A and B), a rat infected with SR11B bacteria (C and D), and a rat infected with SR11B bacteria and treated with H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK (E and F). Arrows point to erythrocytes and arrowheads to bacteria adhering to erythrocytes. Bars, 10 μm (A, C, and E) and 100 μm (B, D, and F).

Table 2.

Quantification of Fibrin Deposition in Rat Lungs

| Animal | Control | SR11B | SR11B +H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | |

| 1 | 2.3 | 87.7 | 18.2 |

| 2 | 3.1 | 60.1 | 19.1 |

| 3 | 3.4 | 71.8 | 19.9 |

| 4 | 2.1 | 87.1 | 23.1 |

Eight rats were infected with SR11B bacteria, from which four were treated with buffer or H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK. Noninfected animals injected with buffer alone served as controls and four animals in each group were analyzed. The ratio of the area containing fibrin deposition versus total area was determined by electron microscopy in six randomly chosen lung tissue sections from each animal. Fibrin deposition in vessels was not subtracted. The P value for the difference in fibrin deposition induced by SR11B in the absence or presence of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK is <0.001.

Discussion

The lung is a common site for primary and secondary infections 25. Pleuropulmonary complications also contribute significantly to the morbidity and mortality of serious and generalized infections such as sepsis. Lung infections caused by Salmonella are rare, except in immunocompromised individuals 26. However, the experimental approach used here makes it possible to investigate the effect of contact system activation by bacteria in lung tissue. Intravenous injection targets the bacteria to the lungs, and previous work has demonstrated that fimbriated Salmonella efficiently activates the contact system 9. Finally, the access to well-defined isogenic Salmonella mutants devoid of contact system–activating fimbriae facilitated the design of distinct control experiments.

Bradykinin is a primary mediator of inflammation, inducing pain, vasodilatation, and increased vascular permeability 27. Previous work has shown that the contact system is assembled and activated not only at the surface of fimbriated Salmonella. Strains of E. coli and Streptococcus pyogenes expressing fibrous surface proteins also have this capacity 9 11 28 29. Moreover, our ongoing work shows that Staphylococcus aureus, yet another important human pathogen, efficiently activates the contact system, emphasizing that this mechanism represents a common and important virulence determinant. It is likely that contact system activation adds selective advantages to the bacteria. A local release of bradykinin will cause leakage of plasma into the infectious focus and provide growing bacteria with nutrients. An increased vascular permeability should also facilitate the dissemination of the infection. Moreover, a hypocoagulative state in the infectious focus will also avoid entrapment of bacteria in a fibrin network.

In relation to this investigation, a massive release of bradykinin in the lungs leading to a damaged vascular barrier is fully compatible with the lesion observed in rats injected with fimbriated Salmonella. This assumption is further substantiated by the finding that the administration of a specific inhibitor of the contact system blocked pulmonary plasma leakage and blood cell infiltration. In addition, the pronounced effect of H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-CMK suggests that synthetic inhibitors based on this structure could be used to treat serious complications in infectious diseases. Such small synthetic molecules have major advantages. First, they do not interfere with the extrinsic tissue factor–driven coagulation pathway, and should therefore not aggravate bleeding disorders often associated with severe infections. Second, when bound to negatively charged surfaces, PK in complex with HK and F XII are protected from their physiological inhibitor, C1 inhibitor 30 31 32. Our initial experiments also indicate that C1 inhibitor fails to block the activation of PK and F XII bound to bacterial surfaces. Similar findings were obtained by studying the interaction between plasmin and different bacterial species, showing that the plasmin absorbed by S. pyogenes and Borrelia burgdorferi is protected from inhibition by α2-plasmin inhibitor 33 34. The administration of peptide derivatives specifically interfering with activated F XII and PK, therefore, represents a novel and potentially interesting approach in the treatment of severe complications of infections caused by bacteria capable of activating the contact system. At a time when microbial resistance to antibiotics is becoming a rapidly increasing medical problem, therapeutic strategies focused primarily on significant pathophysiological mechanisms have clear advantages compared with antibiotic therapy. Such treatment is also often initiated too late and without clinical effect in cases of acute and severe infectious diseases.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank U. Palmertz for performing animal experiments and N. Svitacheva for assistance with histological preparations.

This work was supported in part by Active Biotech AB, Åke Wibergs Stiftelse, Alfred Österlunds Stiftelse, Anna-Greta Crafoords Stiftelse för Rheumatologisk Forskning, Crafoordska Stiftelsen, the Foundation for Strategic Research, Göran Gustafsson Foundation for Research in Natural Sciences and Medicine, Greta och Johan Kocks Stiftelser, Konung Gustaf V's 80-årsfond, Kungl. Fysiografiska Sällskapet in Lund, the Medical Faculty of Lund University, the Swedish Medical Research Council (projects 7480, 13413, and 4342), and Tore Nilsons Stiftelse. K. Persson is supported by The Infection and Vaccinology program at the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research.

Footnotes

K. Persson and M. Mörgelin contributed equally to this work.

Abbreviations used in this paper: aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; F, factor; HK, H-kininogen; PK, plasma kallikrein; PT, prothrombin.

References

- Cicala C., Cirino G. Linkage between inflammation and coagulationan update on the molecular basis of the crosstalk. Life Sci. 1998;62:1817–1824. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)01167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pixley R.A., Colman R.W. The kallikrein-kinin system in sepsis syndrome. In: Farmer S.G., editor. Handbook of ImmunopharmacologyThe Kinin System. Academic Press; New York: 1997. pp. 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan A.P., Joseph K., Shibayama Y., Reddigari S., Ghebrehiwet B., Silverberg M. The intrinsic coagulation/kinin-forming cascadeassembly in plasma and cell surfaces in inflammation. Adv. Immunol. 1997;66:225–272. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60599-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman R.W., Schmaier A.H. Contact systema vascular biology modulator with anticoagulant, profibrinolytic, antiadhesive, and proinflammatory attributes. Blood. 1997;90:3819–3843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pixley R.A., Zellis S., Bankes P., DeLa Cadena R.A., Page J.D., Scott C.F., Kappelmayer J., Wyshock E.G., Kelly J.J., Colman R.W. Prognostic value of assessing contact system activation and factor V in systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Crit. Care Med. 1995;23:41–51. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199501000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsén A., Jonsson A., Normark S. Fibronectin binding mediated by a novel class of surface organelles on Escherichia coli . Nature. 1989;338:652–655. doi: 10.1038/338652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukupolvi S., Lorenz R.G., Gordon J.I., Bian Z., Pfeifer J.D., Normark S.J., Rhen M. Expression of thin aggregative fimbriae promotes interaction of Salmonella typhimurium SR-11 with mouse small intestinal epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 1997;65:5320–5325. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5320-5325.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinson S.K., Emödy L., Müller K.H., Trust T.J., Kay W.W. Purification and characterization of thin, aggregative fimbriae from Salmonella enteritidis . J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:4773–4781. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.15.4773-4781.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herwald H., Mörgelin M., Olsén A., Rhen M., Dahlbäck B., Müller-Esterl W., Björck L. Activation of the contact-phase system on bacterial surfaces—a clue to serious complications in infectious diseases. Nat. Med. 1998;4:298–302. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinson S.K., Doig P.C., Doran J.L., Clouthier S., Trust T.J., Kay W.W. Thin, aggregative fimbriae mediate binding of Salmonella enteritidis to fibronectin. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:12–18. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.1.12-18.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Nasr A.B., Olsén A., Sjöbring U., Müller-Esterl W., Björck L. Assembly of human contact phase factors and release of bradykinin at the surface of curli-expressing Escherichia coli . Mol. Microbiol. 1996;20:927–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsén A., Wick M.J., Mörgelin M., Björck L. Curli, fibrous surface proteins of Escherichia coli, interact with major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:944–999. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.944-949.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian Z., Brauner A., Li Y., Normark S. Expression of and cytokine activation by Escherichia coli curli fibers in human sepsis. J. Infect. Dis. 2000;181:602–612. doi: 10.1086/315233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg M.B., Rubin R.H. The spectrum of Salmonella infection. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 1988;2:571–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galofre J., Moreno A., Mensa J., Miro J.M., Gatell J.M., Almela M., Claramonte X., Lozano L., Trilla A., Mallolas J. Analysis of factors influencing the outcome and development of septic metastasis or relapse in Salmonella bacteremia . Clin. Infect. Dis. 1994;18:873–878. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.6.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantasia M., Filetici E., Arena S., Mariotti S. Serotype and phage type distribution of salmonellas from human and non-human sources in Italy in the period 1973–1995. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1998;14:701–710. doi: 10.1023/a:1007434001440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez M., de Diego I., Mendoza M.C. Extraintestinal salmonellosis in a general hospital (1991 to 1996)relationships between Salmonella genomic groups and clinical presentations. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1998;36:3291–3296. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3291-3296.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubben D., Schmitt R. Tn1721 derivatives for transposon mutagenesis, restriction mapping and nucleotide sequence analysis. Gene. 1986;41:145–152. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D.G., Evans D.J.J., Tjoa W. Hemagglutination of human group A erythrocytes by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from adults with diarrheacorrelation with colonization factor. Infect. Immun. 1977;18:330–337. doi: 10.1128/iai.18.2.330-337.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraker P.J., Speck S.C.J. Protein and cell membrane iodinations with a sparingly soluble chloroamide, 1,3,4,6-tetrachloro-3a,6a-diphrenylglycoluril. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1978;80:849–857. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(78)91322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott C.F., Whitaker E.J., Hammond B.F., Colman R.W. Purification and characterization of a potent 70-kDa thiol lysyl-proteinase (Lys-gingivain) from Porphyromonas gingivalis that cleaves kininogens and fibrinogen. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:7935–7942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghebrehiwet B., Randazzo B.P., Dunn J.T., Silverberg M., Kaplan A.P. Mechanisms of activation of the classical pathway of complement by Hageman factor fragment. J. Clin. Invest. 1983;71:1450–1456. doi: 10.1172/JCI110898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tans G., Janssen-Claessen T., Rosing J., Griffin J.H. Studies on the effect of serine protease inhibitors on activated contact factors. Application in amidolytic assays for factor XIIa, plasma kallikrein and factor XIa. Eur. J. Biochem. 1987;164:637–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb11174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decarie A., Raymond P., Gervais N., Couture R., Adam A. Serum interspecies differences in metabolic pathways of bradykinin and [des-Arg9]BKinfluence of enalaprilat. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:H1340–H1347. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.4.H1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler A.P., Bernard G.R. Treating patients with severe sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;340:207–214. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901213400307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casado J.L., Navas E., Frutos B., Moreno A., Martin P., Hermida J.M., Guerrero A. Salmonella lung involvement in patients with HIV infection. Chest. 1997;112:1197–1201. doi: 10.1378/chest.112.5.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhoola K.D., Figueroa C.D., Worthy K. Bioregulation of kininskallikreins, kininogens, and kininases. Pharmacol. Rev. 1992;44:1–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Nasr A.B., Herwald H., Müller-Esterl W., Björck L. Human kininogens interact with M protein, a bacterial surface protein and virulence determinant. Biochem. J. 1995;305:173–180. doi: 10.1042/bj3050173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Nasr A.B., Herwald H., Renné T., Müller-Esterl W., Björck L. Absorption of kininogen from human plasma by Streptococcus pyogenes is followed by the release of bradykinin. Biochem. J. 1997;326:657–660. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapira M., Scott C.F., Colman R.W. Protection of human plasma from inactivation by C1 inhibitor and other protease inhibitors. The role of high molecular weight kininogen. Biochemistry. 1981;20:2738–2743. doi: 10.1021/bi00513a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapira M., Scott C.F., James A., Silver L.D., Kueppers F., James H.L., Colman R.W. High molecular weight kininogen or its light chain protects human plasma kallikrein from inactivation by plasma protease inhibitors. Biochemistry. 1982;21:567–572. doi: 10.1021/bi00532a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pixley R.A., Schmaier A., Colman R.W. Effect of negatively charged activating compounds on inactivation of factor XIIa by Cl inhibitor. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1987;256:490–498. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(87)90606-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lottenberg R., Broder C.C., Boyle M.D. Identification of a specific receptor for plasmin on a group A streptococcus. Infect. Immun. 1987;55:1914–1918. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.8.1914-1918.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs H., Wallich R., Simon M.M., Kramer M.D. The outer surface protein A of the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi is a plasmin(ogen) receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:12594–12598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]