Abstract

Caspase-9 is critical for cytochrome c (cyto-c)-dependent apoptosis and normal brain development. We determined that this apical protease in the cyto-c pathway for apoptosis resides inside mitochondria in several types of cells, including cardiomyocytes and many neurons. Caspase-9 is released from isolated mitochondria on treatment with Ca2+ or Bax, stimuli implicated in ischemic neuronal cell death that are known to induce cyto-c release from mitochondria. In neuronal cell culture models, apoptosis-inducing agents trigger translocation of caspase-9 from mitochondria to the nucleus, which is inhibitable by Bcl-2. Similarly, in an animal model of transient global cerebral ischemia, caspase-9 release from mitochondria and accumulation in nuclei was observed in hippocampal and other vulnerable neurons exhibiting early postischemic changes preceding apoptosis. Loss of mitochondrial barrier function during neuronal damage from ischemia or other insults therefore may play an important role in making certain caspases available to participate in apoptosis.

Caspases are the principal effectors of apoptosis (1). These cysteine proteases reside in the cytosol of all animal cells as inactive zymogens. Proteolytic processing of these zymogens generates active enzymes and triggers apoptosis. A variety of experimental approaches, including use of cell-permeable peptidyl inhibitors and genetically engineered mice, have demonstrated an important role for caspases in neuronal cell death in vivo after ischemic insults (2, 3).

One of the major pathways for caspase activation involves the participation of mitochondria (4). Release of cytochrome c (cyto-c) from the intermembrane space (IMS) of these organelles occurs on treatment of cells with many apoptotic stimuli. On entry into the cytosol, cyto-c binds the caspase-activating protein Apaf-1, stimulating binding of Apaf-1 to pro-caspase-9 and inducing processing and activation of this caspase (5).

It is assumed that pro-caspase-9 resides in the cytosol of cells, similar to most other caspases. In this report, we provide evidence that, in some types of cells, including cardiomyocytes and many neurons, caspase-9 is located within the IMS of mitochondria. Moreover, caspase release from mitochondria occurs during in vitro apoptosis and during stroke in an animal model. Thus, loss of mitochondrial barrier function is a prerequisite for access of this caspase to its substrates.

METHODS

Antibodies.

Rabbit antisera were generated as described (6), using as immunogens either affinity-purified His6-tagged caspase-9 (0.15 mg per immunization) (7) or a synthetic peptide representing amino acids 112–130 of human pro-caspase-9 (NH2-CRPEIRKPEVLRPETPRPVD-amide) conjugated to maleimide-activated keyhole limpet hemocyanin (0.5 mg per immunization). For affinity purification, a His6-tagged, catalytically inactive Cys287Ala mutant of pro-caspase-9 was expressed from a pET23b plasmid in BL21 cells and was affinity-purified by using Ni–nitrilotriacetic acid resin and FPLC (7, 8). This pro-caspase-9 (C287A) protein was dialyzed into 0.1 M NaHCO3 (pH 8.3) and 0.5 M NaCl, and 20 mg was coupled to 1 g of CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B. Antisera (1:10 in PBS) were passed through a Sepharose-caspase-9 column several times before washing the column with PBS and eluting antibodies in 0.1 M glycine (pH 2.5), followed by pH neutralization with 1 M Tris (pH 9.5).

Paraffin Immunohistochemistry.

Bouin’s—or 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA)—fixed tissue sections (5 μm) were deparaffinized, microwave-heated, and immunostained by using either an avidin-biotin complex reagent (Vector Laboratories) with diaminobenzidine-based colorimetric detection (6) or the Envision-Plus-HRP system (Dako) with a Dako Universal Staining System automated immunostainer. Crude antisera were used at 1:800 or 1:1,500 (vol/vol) dilution. Purified antibody was used at ≈0.1–0.2 μg/ml. For all tissues examined, the immunostaining procedure was performed in parallel by using preimmune serum to verify specificity, or the antiserum was preadsorbed with 5–10 μg/ml of synthetic peptide or recombinant protein immunogen. Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated UTP end labeling (TUNEL) analysis was performed as described (6).

Immunoblotting.

Tissues, cultured cells, or isolated mitochondria were lysed in either 1× Laemmli solution lacking bromophenol blue or in RIPA buffer (0.15 mM NaCl/0.05 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.2/1% Triton X-100/1% sodium deoxycholate/0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) containing protease inhibitors including the caspase inhibitors 100 μM Z-Asp-2.6-dichlorobenzoyloxymethyl-ketone (Bachem) and Z-Val-Ala-Asp-fmk (Calbiochem). Total protein content was quantified by either the Bradford or bicinchoninic acid methods (Pierce). SDS/PAGE and immunoblotting with enhanced chemiluminescence-based detection (Amersham Pharmacia) were performed as described (9).

Immunoelectron Microscopy.

Anesthetized rats were perfused with PBS containing 2% PFA and then were postfixed with PBS containing 2% PFA and 2% glutaraldehyde, followed by incubation in 0.5% osmium tetroxide and 2% uranyl acetate. After dehydration using a graded series of ethanol rinses, tissue specimens were embedded in LR White embedding resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, PA). Ultrathin sections were incubated with crude or purified anti-caspase 9 antibodies, and immunodetection was accomplished by using 10-nm gold-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Amersham Pharmacia) (10). All experiments included controls of preimmune serum, non-immune rabbit IgG, or antigen-preadsorbed anti-caspase-9 antibody. Specimens were visualized and photographed by using a Hitachi-600 electron microscope. Gold particles were counted over a minimum of 50 cells or 50 mitochondria.

Mitochondria.

Rat heart or brain mitochondria were prepared by differential centrifugation or 8.5–16% continuous Percol-gradients, respectively (11, 12). Electron microscopy (EM) analysis confirmed negligible contamination by other organelles. Mitochondria were resuspended (10 mg total protein/ml) in cMRM (10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4/0.25 M sucrose/2 mM KH2P04/5 mM Na-succinate/1 mM ATP/0.08 mM ADP) with or without 5 mM EGTA and were aliquotted (25 μl) for treatment in 50 μl total volume at either 4°C for 20 min with various concentrations of digitonin (0.5–2%) or trypsin (12.5–125 ng/ml) or at 30°C for 45 min with CaCl2 (0.16–150 μM) or recombinant Bax protein (0.3–2 μM) (13). In some cases, mitochondria were sedimented by centrifugation and were placed into hypotonic buffer (50 mM Hepes⋅KOH, pH 6.75) to induce outer membrane rupture (14). Mitochondria were recovered by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min directly or through a 0.3 M sucrose cushion, and the supernatant and pellet fractions were mixed with an equal volume of 2× Laemmli solution or RIPA with protease inhibitors (6, 9). For EM, mitochondria were fixed in PBS containing 2% PFA and 2% glutaraldehyde.

PC12 Cell Cultures.

PC12-Puro and PC12-Bcl-2 cells (15) were maintained in DMEM medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum, 10% equine serum, and 2 μg/ml puromycin. Differentiated cells were obtained by withdrawing growth factors for 7–10 days. Apoptosis was induced by addition to cultures of 150 μM tamoxifen (Sigma) or 3 μM staurosporin. Mitotracker dye 25 nM (Molecular Probes) was added during the final 15 min of culture for immunofluorescence experiments.

Confocal Immunofluorescence Microscopy.

PC12 cells were fixed in 4% PFA in PBS (pH 7.4), were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100, and were subjected to immunostaining using anti-caspase-9 antiserum with FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma) essentially as described (10). Single- and two-color images were prepared by using a Bio-Rad MRC 1024 confocal microscope.

Cerebral Ischemia Model.

A canine model of transient global ischemia induced by cardiac arrest/resuscitation (10 min) was used (16, 17). Postischemic and sham-operated animals were perfused under chloralose anesthesia with PBS containing 4% PFA at 10–30 min and 2, 4, 24, and 48 hr after reperfusion (16, 17). Data are based on results from at least three animals per time point. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with guidelines established by the Institutional Animal Care and use Committee of the George Washington University Medical Center.

RESULTS

Caspase-9 Is Associated with Organelles in Some Types of Cells.

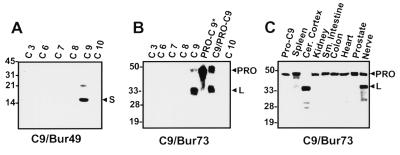

Antisera were generated against caspase-9 by using recombinant caspase-9 or synthetic peptides. Three anti-caspase-9 antisera were generated and determined to react specifically with caspase-9, based on immunoblot experiments in which several recombinant caspases, including caspases-3, -6, -7, -8, -9, and -10, were compared (Fig. 1 A and B; data not shown). The anti-caspase-9 antibodies detected the expected ≈50-kDa proform of the protease in most human and rodent tissues tested. In addition, ≈35- and ≈15-kDa immunoreactive bands corresponding to the processed large and small subunits of caspase-9, respectively, were seen in some tissues, particularly those of nervous system origin (Fig. 1C; data not shown), possibly occurring as a postmortem artifact.

Figure 1.

Characterization of anti-caspase-9 antisera. Antisera were generated in rabbits by using either purified recombinant processed caspase-9 (Bur49) or a synthetic peptide corresponding to amino acids 112–130 of human caspase-9 (Bur 73). (A and B) Immunoblot analysis of recombinant processed caspases-3, -6, -7, -8, -9, and -10 (C3-C10), pro-caspase-9, in which the active site cysteine was mutated to alanine to prevent autoprocessing (PRO-C9*), and a preparation of recombinant C9 containing both unprocessed pro-C9 and processed C9 (C9/PRO-C9) (15 ng protein) (7, 8). Note that antiserum Bur49 reacts primarily with the ≈15-kDa small subunit whereas antiserum Bur73 reacts with the ≈35-kDa large subunit of caspase-9. Both antibodies equally recognize the proform of caspase-9 (data not shown). (C) Tissue lysates were prepared from human autopsy material, were normalized for total protein (100 μg), and were subjected to SDS/PAGE/immunoblot assay by using anti-caspase-9 antiserum Bur73. Most tissues contain the unprocessed ≈50-kDa pro-caspase-9 protein whereas processed caspase-9 was identified in brain and peripheral nerve tissue samples.

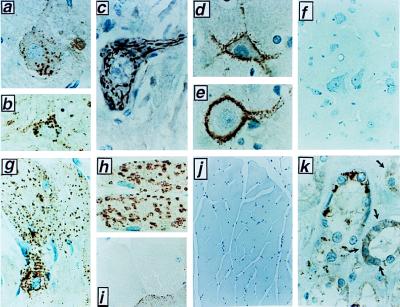

Immunohistochemical analysis of caspase-9 was performed by using these antisera and paraffin-embedded adult human, canine, rat, and mouse tissues. A complete survey of all human tissues was performed; selected animal tissues also were analyzed, yielding similar results. Surprisingly, in only a few tissues, caspase-9 immunoreactivity was localized diffusely throughout the cytosol of cells (e.g., epidermis and distal collecting tubules in the kidney; Fig. 2k). However, in several types of cells, including hepatocytes, skeletal muscle, cardiomyocytes, and most neurons, caspase-9 immunostaining was found in a striking punctate cytosolic distribution, suggestive of organelle association (Fig. 2). The specificity of all immunostaining results was confirmed by comparisons with preimmune sera and use of anti-caspase-9 antisera that had been preabsorbed with either recombinant caspase-9 protein or caspase-9 peptide (Fig. 2 f and i; data not shown). Furthermore, selected results also were verified by immunostaining of tissues from caspase-9 knock-out mice (Fig. 2j).

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical analysis of Caspase-9 in tissues. Selected examples of cells that exhibited an organellar pattern of caspase-9 immunostaining are presented. Results were confirmed by immunostaining with at least two independent anti-caspase-9 antisera [Bur73 (a–c); Bur49 (d–k)]. Controls for nonspecific immunostaining also were performed for all tissues, including use of preimmune serum and antigen-preadsorbed serum, though only two examples are presented here (f and i). a–c demonstrate caspase-9 immunoreactivity in the brain, including large and small striatal neurons (a–b, ×400) and brain stem motorneurons (c, ×1,000). (d and e) caspase-9 immunopositive presynaptic termini synapsing on large cortical neurons that are caspase-9 immunonegative (×1,000). [Immuno-EM analysis indicated that presynaptic mitochondria account for circumferential immunostaining surrounding such cells (data not shown).] (f) Antigen preadsorbed antiserum yields essentially no immunostaining in brain stem (×400). (g) Caspase-9 immunostaining in rat skeletal muscle (×400). Rat heart stained with antibody Bur-49 (h, ×400) or with antibody that had been preadsorbed with caspase 9 recombinant protein (i, ×400). (j) Skeletal muscle (×200) derived from a caspase-9 knock-out mouse, revealing essentially no caspase-9 immunostaining. Age-matched tissue from normal littermates was caspase-9 immunopositive (data not shown). (k) Distal convoluted tubules of rat kidney, revealing a combination of cytosolic (dark arrows) and organellar caspase-9 immunostaining (×1,000).

Caspase-9 Resides Within Mitochondria.

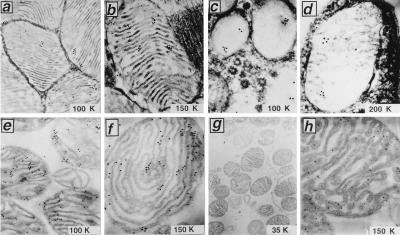

To precisely localize caspase-9, immunogold EM was performed, focusing efforts on heart and brain in which light microscopic results revealed an organellar immunostaining pattern. Immunogold labeling using anti-caspase-9 antisera and postembedding methods revealed immunoreactivity primarily within mitochondria in the heart (Figs. 3 a and b). Counting of gold particles in 10 immunolabeled sections revealed 86% within mitochondria, 11% associated with the surface of these organelles, and 3% overlying other areas of the cells. Negligible immunogold labeling was produced by using preimmune serum or anti-caspase-9 antiserum preadsorbed with specific antigen (data not shown), thus confirming the specificity of these results. Similar results were obtained by immuno-EM analysis of brain (Figs. 3 c and d).

Figure 3.

Immuno-EM analysis of Caspase-9 in rat heart, brain, and isolated mitochondria. Ultrathin sections of heart muscle (a and b) or cerebellum (c and d) were analyzed by using postembedding immunogold methods and anti-caspase-9 antiserum Bur49. Images in c and d represent presynaptic mitochondria. Use of anti-caspase 9 antiserum preadsorbed with recombinant caspase-9 protein resulted in essentially no immunogold staining (data not shown). In e–h, mitochondria were isolated from rat heart and were fixed, embedded, and sectioned for immunogold EM analysis using anti-caspase-9 antisera (e and f) or anti-caspase-9 antiserum preadsorbed with recombinant caspase-9 protein (g) or stained with monoclonal antibody to Hsp60 (h). Identical staining procedures performed by using an irrelevant mouse IgG as a control for Hsp60 produced negligible gold deposits.

In addition to perfused tissues, immunogold EM analysis of caspase-9 also was undertaken by using mitochondria isolated from rat heart (Fig. 3 e and f) and brain (data not shown). Caspase-9 immunolabeling was found within these organelles, primarily within the IMS. Counting of immunogold particles on 42 electron micrographs from five immunostaining experiments demonstrated 90% of particles within the IMS, compared with only 6% within the electron dense matrix and 4% overlying the outer membrane. As an additional control, isolated mitochondria also were immunostained by using an antibody that recognizes Hsp60, a mitochondria-specific molecular chaperone found within the matrix. When using anti-Hsp60 antibody for immunogold labeling, most (92%) particles were found within the matrix or at the border of the matrix and inner membrane (Fig. 3h).

Caspase-9 Exodus from Isolated Mitochondria Is Triggered by Cytochrome c-Releasing Agents.

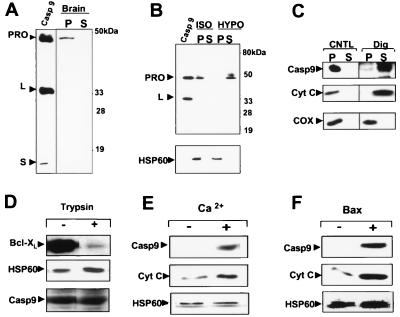

Because caspase-9 is involved in cyto-c-induced apoptotic cell death (5, 18, 19), we next used a number of biochemical approaches to further evaluate the subcellular and submitochondrial location of pro-caspase-9 and its relationship to agents known to cause the release of cyto-c. When soluble cytosolic and organelle-containing membrane fractions were prepared from rat brain or heart by isotonic methods that minimize organelle rupture, most of the pro-caspase-9 was found within the membrane fraction (Fig. 4A; data not shown). Thus, in these tissues in which mitochondrial caspase-9 immunostaining patterns were observed, little pro-caspase-9 appears to reside in the cytosol. This situation, however, differs from results obtained with a variety of tumor cell lines in which pro-caspase-9 resides partly in cytosol (5, 7, 20).

Figure 4.

Pro-caspase-9 release from isolated mitochondria is induced by digitonin, Ca2+, or Bax. (A) Isotonic, detergent-free rat brain homogenates were used to prepare an organelle-containing (P) fraction and a cytosolic supernatant (S) fraction. The P and S fractions (50 μg) were subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-caspase-9 antiserum Bur49. Recombinant caspase-9 (15 ng) was included as a control. Reprobing the same blot with antibodies specific for mitochondrial and cytosolic proteins verified appropriate fractionation (data not shown). (B–F) Mitochondria were isolated from either rat heart or liver, were resuspended in EGTA-containing isotonic buffer (11), were normalized for total protein content and were subjected to various treatments as indicated, then were sedimented by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 4 min to collect the post-mitochondria supernatant (S) or pellet (P) fractions. Samples were analyzed by SDS/PAGE/immunoblotting by using various antibodies with enhanced chemiluminescence-based detection. (B) Mitochondria were incubated in either isotonic (ISO) or hypotonic (HYPO) solution for 20 min at 4°C before preparing S and P fractions for immunoblot analysis with antibodies to caspase-9 and Hsp60. Recombinant caspase-9 was included as a control. (C) Mitochondria were incubated in isotonic solution containing 1% digitonin at 4°C for 20 min and then were sedimented. S and P fractions were analyzed by using antibodies to caspase-9, cyto-c and COX-IV. (D) Mitochondria were incubated at 4°C for 20 min with (+) or without (−) 125 ng/ml trypsin; then, the entire contents were mixed with an equal volume of Laemmli loading solution and were subjected to SDS/PAGE using antibodies specific for caspase-9, cyto-c, or Bcl-XL. (E and F) Mitochondria were treated in the absence of EGTA with either 25 μM CaCl2 or 1.2 μM Bax at 30°C for 45 min and then were sedimented to produce S and P fractions. S fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting for caspase-9 (Top), cyto-c (Middle), or Hsp60, which was negative (data not shown). Immunoblot analysis of pellet fractions using anti-Hsp60 antibody confirmed input of equivalent amounts of mitochondria for all samples (Bottom).

Evidence that pro-caspase-9 was associated specifically with mitochondria came from experiments in which intact mitochondria were isolated from rat heart or liver, were verified by EM and enzyme markers to be >95% pure, and then were subjected to immunoblot analysis. Furthermore, when isolated mitochondria were placed in hypotonic solution under conditions known to selectively rupture the outer membrane leaving the inner membrane intact (14), pro-caspase-9 was liberated into the supernatant while the matrix protein Hsp60 remained in the insoluble pellet (Fig. 4B).

To further confirm that caspase-9 resides within the IMS, differential digitonin extractions were performed. Treatment of isolated mitochondria with low concentrations (<1%) of digitonin is known to selectively solubilize the cholesterol-rich outer membrane of these organelles, leaving the inner membrane mostly intact (14, 21). Digitonin (0.5–1%) released pro-caspase-9 and cyto-c from isolated rat and liver mitochondria whereas the inner membrane protein cytochrome c oxidase (COX-subunit IV) and the matrix protein Hsp60 remained associated largely with the digitonin-extracted pellets (Fig. 4C; data not shown). Protease sensitivity experiments provided further support for the contention that caspase-9 resides within rather than on the surface of mitochondria (Fig. 4D). In contrast, outer membrane proteins such as Bcl-XL were trypsin-digestible under the same conditions.

Cyto-c release from the IMS of isolated mitochondria can be induced in vitro by several agents (4). Previously, it was shown that Ca2+ and the pro-apoptotic protein Bax induce cyto-c release from mitochondria via different mechanisms, with the former involving organellar swelling and outer membrane rupture and the latter occurring through a swelling-independent mechanism (22). We therefore compared the effects of Ca2+ and recombinant purified Bax protein on caspase-9 and cyto-c by using isolated rat heart or liver mitochondria. Ca2+ and Bax induced release of both cyto-c and pro-caspase-9 into the supernatants of isolated mitochondria (Fig. 4 E and F). The kinetics of release of these two proteins were similar. Ca2+-induced release was completely suppressed by cyclosporin A (data not shown). In contrast, Hsp60 was not released into the supernatants of Ca2+ or Bax-treated mitochondria (Fig. 4 E and F; data not shown). Altogether, these studies involving isolated mitochondria argue that pro-caspase-9 is located in the IMS and can be released by stimuli known to trigger exodus of cyto-c from these organelles.

Dynamic Relocalization of Caspase-9 in a Model of Neuronal Cell Death.

We evaluated the localization of caspase-9 in differentiated PC12 cells by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy before and after treatment with the apoptosis-inducing agents staurosporin or tamoxifen. Comparisons were made with transfected PC12 cells that overexpress the anti-apoptosis protein Bcl-2, conferring resistance to cell death (15).

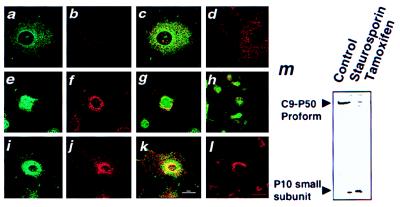

As shown in Fig. 5a, caspase-9 immunoreactivity was localized primarily to punctate cytosolic structures in untreated PC12-Puro and PC12-Bcl-2 cells. Two-color confocal analysis of these cells after culture with a mitochondria-specific rhodamine-like dye demonstrated colocalization of caspase-9 and mitochondria in untreated cells (Fig. 5c). In contrast to untreated PC12-Puro cells, caspase-9 immunofluorescence was found primarily within the nuclei of cells after treatment with the apoptosis-inducing agents staurosporine or tamoxifen, where it no longer colocalized with mitochondria (Fig. 5 e–h). This apparent relocalization of caspase-9 from mitochondria to nucleus was evident within hours, preceding the development of apoptotic features such as nuclear fragmentation and cell shrinkage by at least half a day. Treatment of PC12-Puro cells with staurosporine or tamoxifen also was associated with proteolytic processing of pro-caspase-9 (Fig. 5m). Similar results were obtained by using two other neuronal apoptosis models (e.g., CMS14.1 and NT2 cells).

Figure 5.

Translocation of caspase-9 from mitochondria to nuclei in PC12 cells during apoptosis. PC12-Puro (a–h) or PC12-Bcl-2 (i–l) cells were cultured with 25 nM Mitotracker without (a–d) or with (e–l) addition of 150 μM tamoxifen for 12 (e–h) or 24 hr (i–l). Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with anti-caspase-9 antiserum followed by FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. In some cases, the anti-caspase-9 antiserum was preadsorbed with recombinant caspase-9 protein d and l). Cells were imaged by two-color confocal immunofluorescence microscopy (10) by using filters to selectively reveal FITC-labeled caspase-9 (a, e, and i), Mitotracker (b, f, and j), or both colors (c, d, g, h, k, and l). In m, PC12-Puro cells were cultured with or without 3 μM staurosporine or 150 μM tamoxifen for 12 hr. Cell lysates were prepared, were normalized for total protein content, and were analyzed by SDS/PAGE/immunoblotting by using anti-caspase-9 antiserum Bur49. Note that this antiserum preferentially reacts with the small subunit of the processed protease.

In contrast to PC12-Puro cells, caspase-9 and mitochondria remained colocalized in PC12-Bcl-2 cells after treatment with apoptosis-inducing agents. In these cells, the mitochondria concentrated around the nucleus, but caspase-9 remained associated with these organelles and did not enter the nucleus, as determined by two-color confocal immunofluorescence microscopic analysis of Mitotracker-stained cells (Fig. 5 i–l).

In Vivo Release of Caspase-9 from Mitochondria in Ischemia-Damaged Neurons.

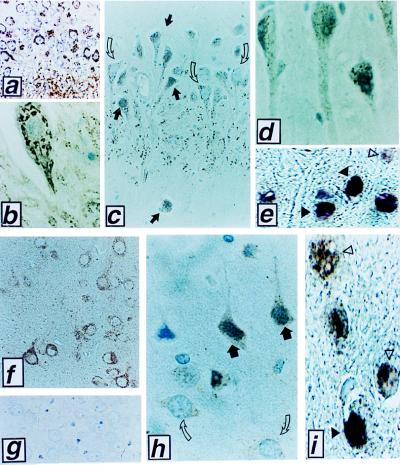

Neurons located within the CA1-CA2 sectors of the hippocampus and some other regions of the brain undergo delayed apoptosis in animal models of transient global cerebral ischemia. We therefore compared the location of caspase-9 immunoreactivity in neurons from these regions of the brain by using tissue sections derived from dogs subjected to 10 min of cardiac arrest followed by resuscitation and 0.5–24 hrs of reperfusion (16, 17). Fig. 6 a–d presents examples of caspase-9 immunostaining in CA1-CA2 sector hippocampal neurons, but similar observations were made in other ischemia-sensitive regions of the brain, such as the thalamus, cerebellum, and cortical layers IV-VI (Fig. 6 f–j; data not shown). Caspase-9 immunostaining was associated with mitochondria in hippocampal and other neurons of sham-operated animals (Fig. 6 a, b, and f). In contrast, after ischemia–reperfusion injury, caspase-9 immunostaining was located diffusely throughout cells or was concentrated over the nuclei of those neurons that developed morphological features of postischemic degeneration (Fig. 6 c, d, and h). Use of preimmune control serum and antigen-preadsorbed serum confirmed the specificity of the caspase-9 immunostaining results (Fig. 6 g; data not shown). Note that sections derived from brain tissues after ischemia contained both morphologically normal neurons that retained punctate cytosolic caspase-9 immunostaining and adjacent degenerating neurons that assumed distorted, sometimes shrunken, shapes and contained condensed chromatin and in which caspase-9 release from mitochondria was evident (Fig. 6 c and h). Nuclei of degenerating neurons were TUNEL-positive (Fig. 6 e and i), consistent with an apoptotic demise. However, caspase-9 release appeared to precede the development of TUNEL-positivity, based on the two-color analysis in which nuclear caspase-9 immunoreactivity was seen in TUNEL-negative neurons undergoing ischemic degeneration (Figs. 6 e and i). Moreover, comparisons of caspase-9 immunostaining and TUNEL-analysis in neurons at earlier times (≈2 hr) after ischemia revealed a larger percentage of neurons with nuclear caspase-9 immunostaining (75–85%) than with TUNEL-positivity (10–25%) in ischemia-damaged cortical foci and hippocampal CA1–2 sectors. In contrast to neurons in the CA1 sector of the hippocampus and other ischemia-sensitive regions, cells in ischemia-resistant regions of the brain such as the CA3 region retained a mitochondrial pattern of caspase-9 immunostaining and did not undergo apoptosis (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Relocalization of caspase-9 in animals subjected to cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Representative photomicrographs are presented of caspase-9 immunostaining results obtained in a canine model of transient global ischemia (16, 17). (a and b) Typical organellar caspase-9 immunostaining is shown in CA1-CA2 sector hippocampal neurons of a sham-operated animal (a, ×150; b, ×1,000); (c) At 2 hr after ischemia/reperfusion in the CA1–2 region of hippocampus, combinations of normal-appearing neurons (open arrows) that retain mitochondrial pattern of caspase-9 immunostaining are seen adjacent to injured neurons (dark arrows) in which caspase-9 immunostaining is diffuse or accumulated around nuclei (×200). (d) At 24 hr, many degenerating neurons contain nuclear caspase-9 (×1,000). (e) These degenerating neurons at 24 hr are mostly TUNEL-positive (black arrows) (×1,000). (f and g) Large cortical neurons of a sham-operated animal immunostained with anti-caspase-9 antiserum without (f) or with (g) prior preabsorption with competing caspase-9 protein (×200). (h) At 2 hr after ischemia/reperfusion, combinations of normal (open arrows) and degenerating (dark arrows) cortical neurons are observed, with caspase 9 immunoreactivity localized diffusely over the cytosol and nuclei of degenerating neurons (×400). (i) At 2 hr after ischemia, most degenerating neurons contain nuclear caspase-9 immunostaining (brown) (open arrows) but are TUNEL-negative. Occasional cells (black arrow) exhibit double labeling with caspase 9 (brown) and TUNEL (purple), with TUNEL-labeling dominating over caspase 9 brown staining (×1,000).

DISCUSSION

The findings reported here indicate the pro-caspase-9 is sequestered within mitochondria in some types of cells. It remains to be determined how pro-caspase-9 enters mitochondria. An N-terminal region of pro-caspase-9 at amino acids 1–11 contains a predicted mitochondrial matrix targeting signal (MDEADRRLLRR) and an apolar signal for intramitochondrial sorting at amino acids 69–77 that can be identified by the program psort (http://www.imcb.osaka-u.ac.jp/nakai/psort.html) as resembling the mitochondrial import leader sequences found within several mitochondrial proteins. Though our analysis of pro-caspase-9 derived from mitochondria revealed no clear evidence based on mobility in SDS/PAGE experiments that the protein undergoes the classical proteolytic processing that removes the N-terminal leader sequence from imported proteins, precedence exists for import of some other leader peptide-containing mitochondrial proteins without cleavage (23). Moreover, although many proteins imported via the classical mitochondrial import pathway enter and reside in the matrix, some are known to undergo subsequent sorting to either the inner membrane or IMS (24). However, analogous to cyto-c, pro-caspase-9 may rely on alternative pathways for its import into the IMS of mitochondria. In this regard, the observation that pro-caspase-9 can reside in either the cytosol or within mitochondria, depending on the cell type, suggests that additional cofactors that may be expressed in a differentiation-specific manner could be involved in controlling the import of pro-caspase-9 into mitochondria. A similar situation apparently exists for pro-caspase-3, in that a small proportion of the total cellular pool of this caspase reportedly enters the IMS of mitochondria through undetermined mechanisms, particularly in neurons (21). However, in contrast to pro-caspase-3, which resides largely in the cytosol of all cells examined throughout the human body (25), the partitioning of pro-caspase-9 to mitochondria is far more striking and appears to entail a nearly complete import of this caspase into the mitochondria, at least in several types of cells.

Previously, it has been suggested that cyto-c release from mitochondria can occur by at least two caspase-independent mechanisms (4, 26). One of these is represented by Ca+2, which stimulates opening of the permeability transition pore in the inner membrane of mitochondria, resulting in osmotic swelling of the matrix, secondary rupture of the outer membrane, and release of proteins stored within the IMS (27). An alternative pathway, however, may involve changes in the permeability of the outer membrane of mitochondria, without the alterations in inner membrane function that produce mitochondrial swelling. In this regard, Bax induces caspase-independent release of cyto-c through a swelling-independent mechanism in vitro (22), presumably as a result of its ability to form pores in membranes or to interact with other channel proteins in mitochondrial membranes (28, 29). Given that pro-caspase-9 release from mitochondria in vitro was inducible by Ca2+ and by Bax under conditions in which swelling-dependent and swelling-independent cyto-c release, respectively, has been observed (22), it seems likely that both mechanisms are capable of liberating this protein from mitochondria. Further analysis, however, is required.

On liberation from mitochondria, caspase-9 appeared to accumulate in nuclei of cells both in vitro in cultured cells and in vivo during cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Of interest, pro-caspase-9 contains two segments rich in basic amino acids resembling nuclear targeting sequences. It is conceivable, therefore, that these candidate nuclear targeting motifs become exposed in the active processed protease, accounting for its accumulation in nuclei. Alternatively, active caspase-9 may piggy-back into nuclei through interactions with other nuclear-targeted proteins.

Caspase-9 is the apical caspase in the cyto-c pathway for apoptosis. This pathway couples mitochondrial damage to caspase activation, thereby acting as a sensor of disturbances in mitochondrial membrane barrier function. Why would it be advantageous to sequester within mitochondria the initiator of this pathway for caspase activation, cyto-c, as well as the effector, pro-caspase-9? One possibility is that sequestration of pro-caspase-9 in mitochondria provides an additional safeguard against inappropriate triggering of apoptosis. Accordingly, if Apaf-1 were to become activated through a cyto-c-independent process, its partner caspase would be unavailable, and, thus, cell death could be avoided. Hints that cyto-c-independent mechanisms of Apaf-1 activation come from the observation that truncation mutants of Apaf-1 lacking the C-terminal WD repeat region reportedly can bind and activate pro-caspase-9 without necessity for cyto-c (20). Intramitochondrial sequestration of pro-caspase-9 might be particularly advantageous for nonreplicating postmitotic cells such as adult neurons and cardiomyocytes, which have little or no regenerative capability. In contrast, other types of cells that are readily replenished through cell division would theoretically have less need for additional safeguards against apoptosis, an idea consistent with our observation of diffuse cytosolic caspase-9 immunostaining in some types of renewable cells and with evidence of cytosolic pro-caspase-9 in many tumor cell lines (5, 7, 20, 30–32).

Our findings of caspase-9 release from mitochondria during stroke may have bearing on strategies for preventing pathological cell death in these ischemic diseases. Small molecule inhibitors of caspases are currently being considered for this purpose, and efforts are underway to determine which particular caspases are the most important drug targets for prevention of cell death (33). Caspase-9 represents an attractive target in its role as the apical caspase in the cyto-c pathway. However, to the extent that release and subsequent activation of caspase-9 occur through mechanisms involving irreversible damage to mitochondria, inhibiting this caspase may be insufficient to rescue ischemia-damaged cells from nonapoptotic cell death. Recent reports of synergistic protection achieved in stroke models by combined use of caspase inhibitory compounds and N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors antagonists that reduce ischemia-associated elevations in cytosolic Ca2+ and mitochondrial damage support this concept (34, 35).

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Snipas, W. P. French, G. Kennedy, X. Xiaokun, and T. Whisenant for technical assistance, G. Shore for advice, R. Flavell for caspase-9 knock-out tissues, T. Brown and E. Smith for manuscript preparation, and the National Institutes of Health for generous support (Grants NS 36821, AG 12282, NS 33376, AG 15402, and NS 34152).

ABBREVIATIONS

- cyto-c

cytochrome c

- IMS

intermembrane space

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated UTP end labeling

- EM

electron microscopy

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

References

- 1.Salvesen G S, Dixit V M. Cell. 1997;91:443–446. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80430-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pettmann B, Henderson C. Neuron. 1998;20:633–647. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergeron L, Yuan J. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;8:55–63. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green D, Reed J. Science. 1998;281:1309–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li P, Nijhawan D, Budihardjo I, Srinivasula S, Ahmad M, Alnemri E, Wang X. Cell. 1997;91:479–489. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krajewski S, Mai J K, Krajewska M, Sikorska M, Mossakowski M J, Reed J C. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6364–6376. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06364.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardone M, Roy N, Stennicke H, Salvesen G, Franke T, Stanbridge E, Frisch S, Reed J. Science. 1998;282:1318–1320. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stennicke H R, Salvesen G S. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25719–25723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krajewski S, Zapata J M, Reed J C. Anal Biochem. 1996;236:221–228. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krajewski S, Tanaka S, Takayama S, Schibler M J, Fenton W, Reed J C. Cancer Res. 1993;53:4701–4714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goping I, Millar D, Shore G. FEBS Lett. 1995;373:45–50. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01010-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polosa P, Attardi G. Meth Enzymol. 1996;264:211–217. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)64021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie Z, Schendel S, Matsuyama S, Reed J C. Biochemistry. 1998;37:6410–6418. doi: 10.1021/bi973052i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pedersen P, Grennawalt J, Reynafarje B, Hullihen J, Decker G, Soper J, Bustamente E. Methods Cell Biol. 1978;20:411–481. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)62030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhong L T, Sarafian T, Kane D J, Charles A C, Mah S P, Edwards R H, Bredesen D E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4533–4537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenthal R, Williams R, Getson P, Bogaert Y, Fiskum G. Stroke. 1992;23:1312–1318. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.9.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, Rosenthal R, Haywood Y, Miljkovic Lolic M, Vanderhoek J, Fiskum G. Stroke. 1998;29:1679–1689. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.8.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuida K, Haydar T F, Kuan C-Y, Gu Y, Taya C, Karasuyama H, Su M S-S, Rakic P, Flavell R A. Cell. 1998;94:325–337. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81476-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hakem R, Hakem A, Duncan G S, Henderson J T, Woo M, Soengas M S, Elia A, de la Pompa J L, Kagi D, Khoo W, et al. Cell. 1998;94:339–352. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81477-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srinivasula S M, Ahmad M, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Alnemri E S. Mol Cell. 1998;1:949–957. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mancini M, Nicholson D, Roy S, Thornberry N, Peterson E, Casciola-Rosen L, Rosen A. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1485–1495. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.6.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jurgensmeier J M, Xie Z, Deveraux Q, Ellerby L, Bredesen D, Reed J C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;5:4997–5002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfanner N. Curr Biol. 1998;8:R262–R265. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ono H, Gruhler A, Stuart R A, Guiard B, Schwarz E, Neupert W. J Biol Chem. 1995;14:16932–16938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krajewska M, Wang H-G, Krajewski S, Zapata J M, Shabaik A, Gascoyne R, Reed J C. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1605–1613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy A, Fiskum G, Beal M. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:231–245. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199903000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernardi P, Broekemeier K M, Pfeiffer D R. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1994;26:509–517. doi: 10.1007/BF00762735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antonsson B, Conti F, Ciavatta A, Montessuit S, Lewis S, Martinou I, Bernasconi L, Bernard A, Mermod J-J, Mazzei G, et al. Science. 1997;277:370–372. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5324.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuyama S, Schendel S, Xie Z, Reed J. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30995–31001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.30995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan G, O’Rourke K, Dixit V M. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5841–5845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu Y, Benedict M, Wu D, Inohara N, Nunez G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4386–4391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deveraux Q, Takahashi R, Salvesen G S, Reed J C. Nature (London) 1997;388:300–303. doi: 10.1038/40901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Villa P, Kaufman S, Earnshaw W. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:388–393. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma J, Endres M, Moskowitz M. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:756–762. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schulz J, Weller M, Matthews R, Heneka M, Groscurth P, Martinou J, Lommatzsch J, Voncoelln R, Wüllner U, Loschmann P, et al. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:847–857. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]