Abstract

Neutrophils are markedly less sensitive to glucocorticoids than T cells, making it difficult to control inflammation in neutrophil-mediated diseases. Development of new antiinflammatory strategies for such diseases would be aided by an understanding of mechanisms underlying differential steroid responsiveness. Two protein isoforms of the human glucocorticoid receptor (GR) exist, GRα and GRβ, which arise from alternative splicing of the GR pre-mRNA primary transcripts. GRβ does not bind glucocorticoids and is an inhibitor of GRα activity. Relative amounts of these two GRs can therefore determine the level of glucocorticoid sensitivity. In this study, human neutrophils and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were studied to determine the relative amounts of each GR isoform.

The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) using immunofluorescence analysis for GRα was 475 ± 62 and 985 ± 107 for PBMCs and neutrophils, respectively. For GRβ, the MFI was 350 ± 60 and 1,389 ± 143 for PBMCs and neutrophils, respectively (P < 0.05). After interleukin (IL)-8 stimulation of neutrophils, there was a statistically significant increase in intensity of GRβ staining to 2,497 ± 140 (P < 0.05). No change in GRα expression was observed. This inversion of the GRα/GRβ ratio in human neutrophils compared with PBMCs was confirmed by quantitative Western analysis. Increased GRβ mRNA expression in neutrophils at baseline, and after IL-8 exposure, was observed using RNA dot blot analysis. Increased levels of GRα/GRβ heterodimers were found in neutrophils as compared with PBMCs using coimmunoprecipitation/Western analysis. Transfection of mouse neutrophils, which do not contain GRβ, resulted in a significant reduction in the rate of cell death when treated with dexamethasone.

We conclude that high constitutive expression of GRβ by human neutrophils may provide a mechanism by which these cells escape glucocorticoid-induced cell death. Moreover, upregulation of this GR by proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-8 further enhances their survival in the presence of glucocorticoids during inflammation.

Keywords: neutrophils, glucocorticoid insensitivity, glucocorticoid receptor, interleukin 8, inflammation

Introduction

Neutrophils have been implicated in the pathogenesis of many diseases, including severe asthma 1 2, psoriasis 3 4, and a variety of collagen-vascular diseases 5 6. These cells are known to be less sensitive to glucocorticoids than other white blood cell types 7. Moreover, glucocorticoid treatment actually inhibits their cell death in vitro 8 9. This is in contrast to T cells, where workers have shown that steroids induce apoptosis 10 11. Thus, use of glucocorticoid therapy in the treatment of neutrophil-associated inflammation is of major clinical concern in terms of disease resolution.

The mechanisms by which human T cell and neutrophil apoptotic responses to glucocorticoids differ are unknown. Glucocorticoid action is mediated through the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), which is found in the cytosol of most human cells 12. As the result of alternative splicing of the GR pre-mRNA, there are two homologous mRNAs and protein isoforms, termed GRα and GRβ. Both mRNAs contain the same first eight exons of the GR gene 13 14 15. The remainder is derived by alternative splicing of the last exon of the GR gene, resulting in either inclusion or exclusion of exon 9α. The two protein isoforms have the same first 727 NH2-terminal amino acids. GRβ differs from GRα only in its COOH terminus with replacement of the last 50 amino acids of GRα with a unique 15 amino acid sequence lacking a steroid binding domain. These differences render GRβ unable to bind glucocorticoids, reduces its binding affinity for DNA recognition sites, abolishes its ability to transactivate glucocorticoid-sensitive genes, and makes it function as a dominant inhibitor of GRα, possibly through formation of antagonistic GRα/GRβ heterodimers 13 16 17 18.

In this study, we confirm that T cells and neutrophils respond differentially to dexamethasone (DEX), the model steroid used. We have also found that IL-8 synergizes with DEX to decrease neutrophil cell death in vitro, and that both of these responses are associated with increases in the ratio of GRβ to GRα. These observations suggest an alternate mode of action of GRs in neutrophils than that observed in PBMCs. On the one hand, glucocorticoids are ineffective at resolving neutrophil-associated inflammation. On the other hand, as glucocorticoids reduce the spontaneous cell death of these cells, neutrophils must be glucocorticoid-sensitive but simply do not react in the same manner as T cells. Therefore, in this study, two different approaches were chosen in an attempt to determine whether shifts in GRβ to GRα levels could account for these different responses to steroids. First, by quantitating the relative levels of GRα and GRβ in human neutrophils, in terms of protein and mRNA levels. Then second, because mouse neutrophils have no GRβ, assessing whether introduction of the GRβ gene into mouse neutrophils changes the effects of glucocorticoids on neutrophil cell death.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of PBMCs.

Heparinized venous blood from normal healthy volunteers was layered on a Ficoll-Paque density gradient (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and centrifuged for 25 min at 400 g at room temperature. The PBMC layer was aspirated, washed, and resuspended in HBSS (GIBCO BRL), then counted. PBMCs were always >95% viable, as determined by a trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich) exclusion assay.

Preparation of Human Neutrophils.

Human neutrophils were isolated from normal healthy individuals using a Percoll (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) density gradient 19. In brief, 4.4 ml of 3.8% (wt/vol) sodium citrate (Fisher Scientific) was added to 40 ml of heparinized venous blood. The blood was then centrifuged at 400 g for 20 min. The plasma layer was then removed, 5 ml of 6% (wt/vol) dextran (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) was then added to the pelleted whole blood, and the total volume was brought up to 50 ml with saline and mixed gently. The cell suspension was then left for 30 min at room temperature to allow the red blood cells to settle. The upper white blood cell layer was removed, centrifuged at 400 g for 10 min, the supernatant discarded, and the pellet resuspended in 2 ml of autologous plasma. The cell suspension was then underlaid first with a 42% (wt/vol), then a 51% (wt/vol) Percoll gradient and centrifuged at 350 g for 10 min. The resulting neutrophil rich layer was carefully removed. Neutrophils were then resuspended in PBS, centrifuged at 350 g for 10 min, and the supernatant discarded. The resulting neutrophil pellet was then resuspended in HBSS.

Preparation of Murine Neutrophils.

For preparation of murine neutrophils, individual BALB/c female mice were given a 1 ml intraperitoneal injection of 4% (wt/vol) Brewer's thioglycollate (DIFCO). After 4 h, the mice were killed by cervical dislocation and the peritoneal cavity washed with cold 1× PBS, 5 mM EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich). The PBS/EDTA cell suspension was harvested with a syringe, pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in 3 ml 1× HBSS. The resulting cell suspension was then layered over a 55/65/81% Percoll gradient and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 20 min. Neutrophils were harvested at the 65/81% interface. Harvested neutrophils were then washed in 1× HBSS, resuspended in RPMI, 10% FCS, and counted.

Preparation of PBMC and Neutrophil Cytospins.

Cells were resuspended at 0.5 × 106 cells/ml in HBSS. 50 μl of each cell suspension was cytospun onto individual microscope slides for 3 min at 300 rpm, air dried, then fixed for 10 min in 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich), and washed in PBS. The cytospins were then washed in PBS, air dried, and stored at −80°C until use.

Immunofluorescence Staining of Neutrophils and PBMCs for GRα and GRβ.

Cytospins of both cell types were incubated for 15 min at room temperature with permeabilizing solution (PBS containing 0.5% [wt/vol] BSA, 0.1% [vol/vol] Tween 20, and 0.1% [wt/vol] saponin [Sigma-Aldrich]). The permeabilizing solution was then tipped off and the cytospins were blocked with a commercial blocking solution (Superblock; Scytek) for 15 min at room temperature. After the incubation period, the blocking solution was aspirated off and discarded. Cytospins were then incubated with affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies to human GRα (Affinity BioReagents, Inc.) or anti-GRβ (preparation and specificity as described in references 13, 20, and 21) and diluted in permeabilizing solution. Purified nonimmune rabbit IgG (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc.) served as the control. The cytospins were then incubated overnight at 4°C. After the incubation period, the cytospins were washed in PBS, 0.1% Tween 20 for 15 min at room temperature with gentle agitation, then incubated with a goat anti–rabbit F(ab′)2 FITC conjugate (Dako) for 30 min at room temperature and washed in PBS, 0.1% Tween 20 for 15 min at room temperature with gentle agitation. Cytospins were then mounted and examined by fluorescence microscopy. Intensity of GR staining was assessed using image analysis software (IPLab Spectrum; Signal Analytics Corporation) and expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI).

Quantitative Western Analysis.

Quantitative Western analysis was performed using specific anti-GRα and GRβ polyclonal antibodies produced in our laboratory as described previously 13. The GRα-directed antibody has been extensively employed in detailed analyses of GRα proteolytic cleavage 20. PBMCs and neutrophils were lysed at 4°C, and 100 μg protein was applied to a 8% precast polyacrylamide-SDS gels (Novex) and electrophoresed in parallel with prestained markers (SeeBlue™; Novex) to estimate molecular weight; increasing concentrations of peptide-BSA conjugate standard (5–25 ng corresponding to 70–360 fmol) were also used for quantitation. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and blocked in 5% nonfat milk for 1 h. Immunoblotting was performed at 4°C overnight using purified GRα- and GRβ-specific polyclonal antibodies at 10 μg/ml. The specificity of these antibodies were described in references 13, 20, and 21. After washing, the blots were incubated at room temperature with peroxidase-conjugated anti–rabbit immunoglobulin antibody (Dako) at 1:4,000 dilution. Blots were washed and exposed to chemiluminescence solution for 1 min. (ECL kit; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), followed by exposure to X-OMAT AR films (Eastman Kodak Co.). Band densities of the standards and the samples developed on the film were scanned and saved on computer disks for densitometry using the NIH image system 1.61 program.

Demonstration of GRα/GRβ Heterodimers by Western Blot Analysis.

3 × 106 PBMCs or neutrophils were lysed in a buffer containing the following protease inhibitors: 0.5 M EDTA, 0.5 mM PMSF, and 10 μg/ml of leupeptin, aprotonin, antipain, and pepstatin (Sigma-Aldrich). The cell lysates were left on ice for 10 min and then centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 rpm. The supernatant was removed and then incubated overnight at 4°C with sepharose beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) covalently linked to a polyclonal antibody that recognized GRα. The beads were then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 30 s. The pelleted beads were then resuspended in loading buffer (0.125 M Tris-HCl [Sigma-Aldrich], 4% [wt/vol] SDS, and 10% [vol/vol] β-mercaptoethanol [Boehringer]).

The beads were then boiled for 5 min and loaded onto a 10% Tris-HCl polyacrylamide mini-gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories) under reducing conditions. The gel was run at 80 V in a running buffer containing the following: 0.3% (wt/vol) Tris-HCl, 1.4% (wt/vol) glycine, and 0.1% (wt/vol) SDS (Boehringer), until the loading dye reached the end of the gel. After the electrophoresis, the protein was transferred to nitrocellulose paper (Bio-Rad Laboratories) at 50 mA for 1 h using a semidry transfer system (BioRad Laboratories). The transfer buffer contained the following: 48 mM Tris-HCl (Sigma-Aldrich), 39 mM glycine, and 20% methanol (Sigma-Aldrich). The nitrocellulose paper was then blocked overnight at 4°C with 5% BSA (wt/vol; Sigma-Aldrich) in 1× dilution buffer (0.2 M Tris-HCl, 0.2% Tween 20, 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8; Sigma-Aldrich). After the incubation period, the membrane was incubated for 2 h at room temperature with an antibody specific to GRβ. The antibody was diluted in PBS containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% (wt/vol) BSA (Sigma-Aldrich). After the incubation period, the membrane was washed in PBS, 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 for 1 h, then incubated for 1 h with an anti–rabbit horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Dako) diluted in 1% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich) in 1× dilution buffer. The membrane was then washed in 1% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich) 1× dilution buffer for 1 h at room temperature, and specific bands were visualized using a commercial chemiluminescence detection system (ECL; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

RNA Dot Blot Analysis.

Total cytoplasmic RNA was isolated from 107 cells (PBMCs or neutrophils) as follows: the cells were cracked in buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 10% glycerol, 50 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, and 0.5 mM EDTA) containing 0.5% NP-40 and 10 mM vanadyl ribonucleoside complex. Nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 1,000 g. RNA was subjected to phenol/chloroform extraction and EtOH precipitation. The RNA was applied to nitrocellulose sheets using vacuum transfer (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and cross-linked at 80°C under vacuum for 2 h. GR RNA was detected by hybridization to 50 base, biotinylated probes. Total GR (GRα plus GRβ) was detected with a probe to exon 9-β: 5′-TTTTAGTCTAATTACACACTCTACACGAAAGACCAAAATTGGTGTATTG-3′. GRα RNA was detected with an oligonucleotide that specifically recognized exon 9-α: 5′-TACCAGAATAGGTTTTTACAAACCTTCGTTATCAATTCCTCTAAAAGTTG-3′.

It was not possible to probe for GRβ mRNA specifically in these studies due to poor specificity of the oligonucleotide probe directed to the exon 8/9β junction, which is the only part of the GRβ mRNA which is not also included in the GRα mRNA. Specificity of the probes was verified by hybridization to GRα and β cDNAs prepared from the expression plasmids Rous sarcoma human (pRSh) GRα and pRSh GRβ. Cross-hybridization of the biotinylated GRα probe to cDNA derived from pRSh GRβ was not noted. After hybridization, the blots were incubated in buffer with streptavidin-linked alkaline phosphatase (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and specific bands were visualized using a chromogenic system comprising 4-nitro blue tetrazolium chloride and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (Boehringer).

Transfection of murine neutrophils with a GRβ containing plasmid neutrophils were transfected with pRSh GRβ that contains the full-length coding region of GRβ under the control of the constitutively active Rous sarcoma virus promoter 18. As a control, a commercially available plasmid vector was used, plasmid green fluorescent protein (pGFP)-C1 (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.). Reversible permeabilization of cells using the pore-forming agent, streptolysin O, was used to enhance uptake of the plasmid 22 23. Streptolysin O (Lee Laboratories) was preactivated with 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT; Bio-Rad Laboratories) for 2 h at room temperature, then added to a transfection medium (TM) consisting of RPMI 1640, 40 μM l-glutamine, and 20 mM Hepes (GIBCO BRL) at a concentration of 20 U/ml with 10 μg of plasmid (pRSh GRβ or pGFP-C; CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.). Freshly isolated murine neutrophils (described above) were then resuspended (4 × 106 cells total) in 200 μl of this streptolysin O/TM/plasmid medium and incubated for 5 min at 37°C. The cells were then resuspended at 106/ml in of RPMI 1640, 40 μM l-glutamine, 20 mM Hepes, and 10% (vol/vol) FCS (GIBCO BRL). Confirmation of GRβ expression of pRSh GRβ transfected cells was confirmed by immunofluorescence (IMF) staining. The method used is described in full earlier; however, the secondary antibody used for this staining was an anti–rabbit Cy3 conjugate (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Transfection efficiency was determined by capturing images of 10 fields per sample, and counting the number of GFP-positive cells. Identification of negative cells was accomplished by nuclear counterstaining with 300 nM 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma-Aldrich). Transfection efficiency was calculated as the average percentage of GFP-positive cells per field.

Evaluation of DEX Effect on pRSh GRβ-transfected Murine Neutrophil Cell Death.

Cells were cultured overnight in 48-well flat-bottomed plates with or without 10−6 M DEX (Sigma-Aldrich). After this incubation period, cells were washed and resuspended in 600 μl of 1× PBS. Each individual sample (n = 7) was divided in two 300-μl aliquots one of which received no treatment as a control the other was stained with propidium iodide (PI; Sigma-Aldrich) at a final concentration of 0.3 μg/ml. PI positivity was determined by flow cytometry (FACScan™; Becton Dickinson) and expressed as percentage of positive cells. Cells were also analyzed via terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end-labeling (TUNEL) to confirm that PI staining corresponded well with TUNEL staining.

Statistical Methods.

Immunofluorescence and the cell death/transfection data were analyzed using the Student's t test.

Results

GR Protein and mRNA Levels in Human Neutrophils.

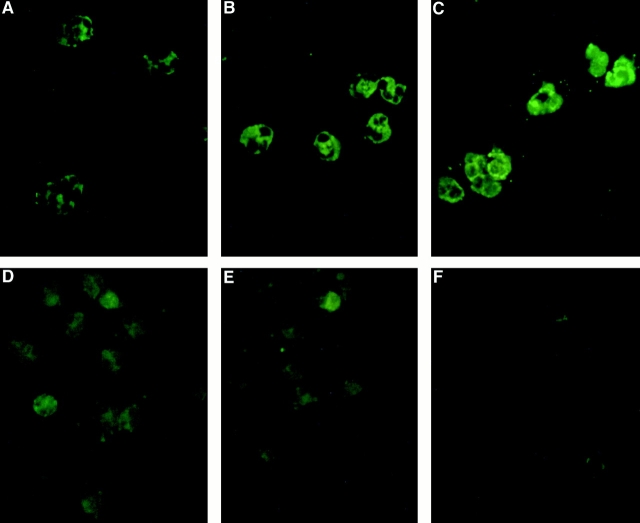

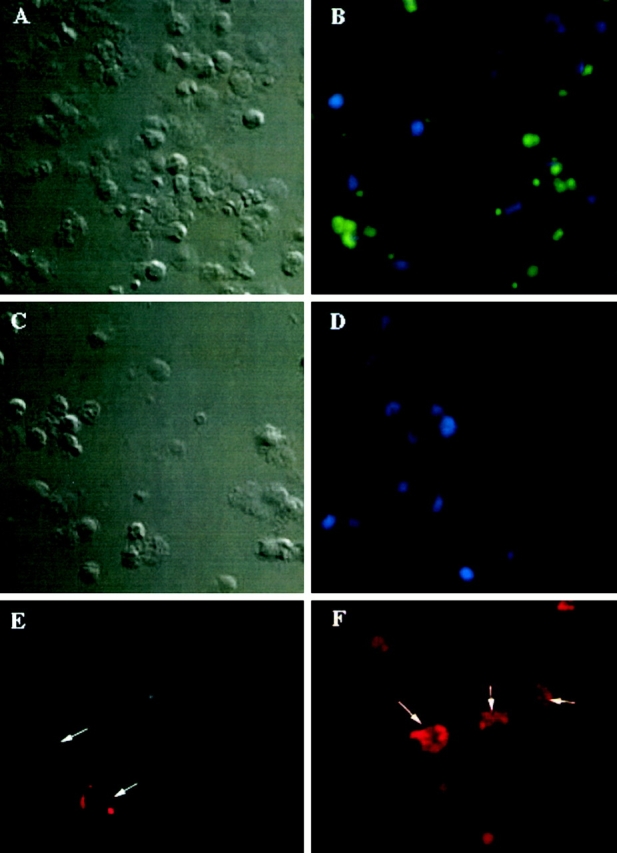

Freshly isolated PBMCs and neutrophils expressed both GR isoforms. By immunofluorescence, the GRs were localized to the cytoplasm of both cell types (Fig. 1), although in some cases a subpopulation of neutrophils did exhibit strong baseline nuclear staining (data not shown). In neutrophils, GRβ immunoreactive protein was expressed at a higher level than GRα (Fig. 1A and Fig. B, respectively). Of interest, when neutrophils were incubated with IL-8, a marked upregulation of GRβ immunoreactivity was observed (Fig. 1 C). Conversely in PBMCs, GRα protein was expressed at a higher level than GRβ (Fig. 1D and Fig. E, respectively).

Figure 1.

Immunofluorescence staining of PBMCs and neutrophils was performed using antibodies specific for either GRα or GRβ. A and B show GRα and GRβ expression in resting neutrophils, respectively. After IL-8 stimulation, GRβ expression was increased as shown in C. In comparison, PBMCs were also stained for GRα and GRβ, which are shown in D and E, respectively. However, these GRs are expressed at a lower level than in neutrophils. F is a negative control consisting of affinity-purified rabbit IgG for the neutrophil staining (×60 objective).

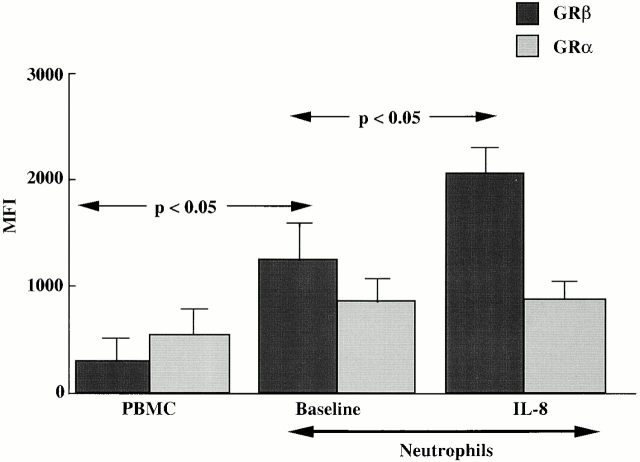

Using image analysis, we were able to quantify the relative intensity of GRβ and GRα staining by MFI (Fig. 2) and confirm our observation of the high expression of GRβ in neutrophils. For PBMCs and neutrophils, the GRα MFIs were 475 ± 62 and 985 ± 107, respectively. In contrast, GRβ MFIs were 350 ± 60 vs. 1,389 ± 143 (P < 0.05) in PBMCs versus neutrophils, respectively. After IL-8 stimulation of neutrophils for 24 h, there was a significant further increase in the intensity of GRβ staining to 2,497 ± 140 (P < 0.05 compared with medium control). However, no change in GRα expression was observed.

Figure 2.

Expression of GRα and GRβ protein in PBMCs and neutrophils. The staining of the two cell types was quantified and expressed as MFI using image analysis software. GRβ expression was significantly higher in neutrophils than PBMCs (P < 0.05). There was also a statistically significant increase in GRβ expression in neutrophils after IL-8 expression (P < 0.05). The mean ± SEM from four separate donors are shown.

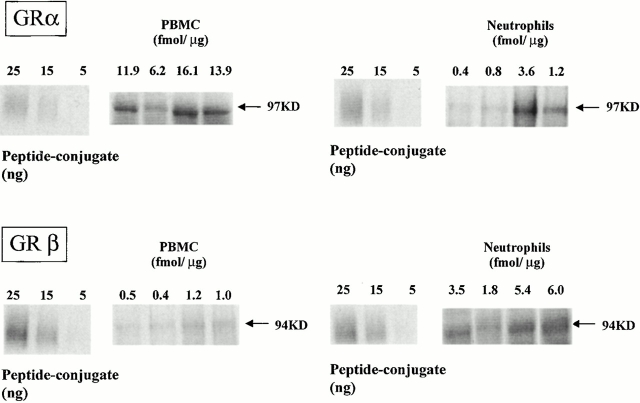

To quantify the absolute amounts of GRα and GRβ contained in the cells, we performed quantitative Western analysis of cell extracts. Immunoreactive GRα and GRβ (Fig. 3), expressed as fmol/μg protein, showed higher concentrations of GRα than GRβ in PBMCs (GRα: 12.0 ± 2.1; GRβ: 0.78 ± 0.2; mean ± SEM). In contrast, GRβ was expressed at higher concentrations than GRα in neutrophils (GRα: 1.6 ± 1.0; GRβ: 4.2 ± 0.9; mean ± SEM). Thus, in keeping with the IMF data, GRβ was expressed at higher level in neutrophils than PBMCs. The relative GRβ/GRα ratio (calculated as mean GRβ/GRα ratio of individual samples) was 73-fold higher in neutrophils (4.4 ± 1.6; mean ± SEM) than PBMCs (0.06 ± 0.007; mean ± SEM). When the two populations of cells were compared, a significant difference was found analyzing the GRα expression (neutrophils versus PBMCs; P = 0.003; t test), as well as the GRβ expression (neutrophils versus PBMCs; P = 0.03; Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test), and the GRβ/GRα ratio (neutrophils versus PBMCs; P = 0.03; Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test).

Figure 3.

Quantitative Western blot analysis for GR in PBMCs and neutrophils. GRβ levels are shown to be much higher than GRα in human neutrophils. In contrast, GRα was found to be the predominant GR in PBMCs. Absolute GR quantities are expressed in fmol/μg of cellular protein and stated above each lane.

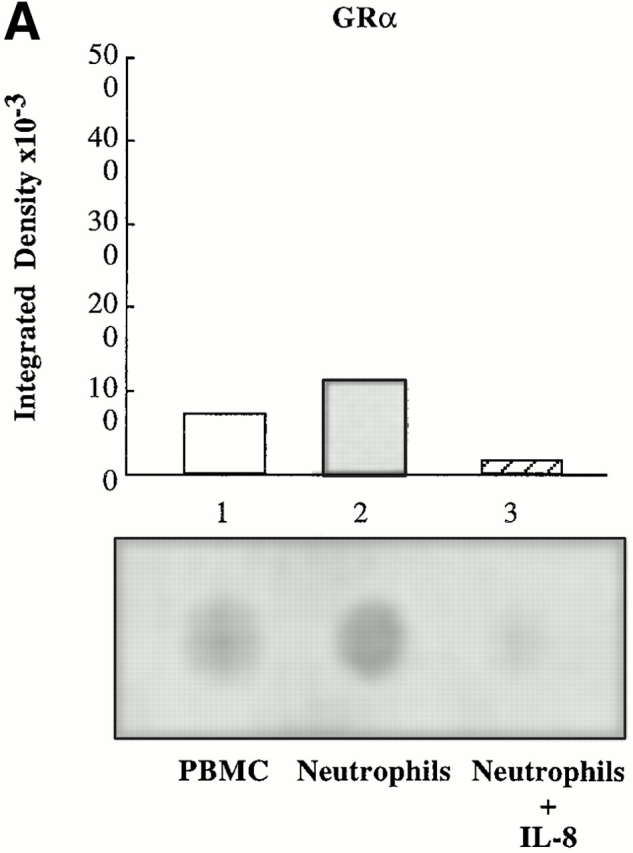

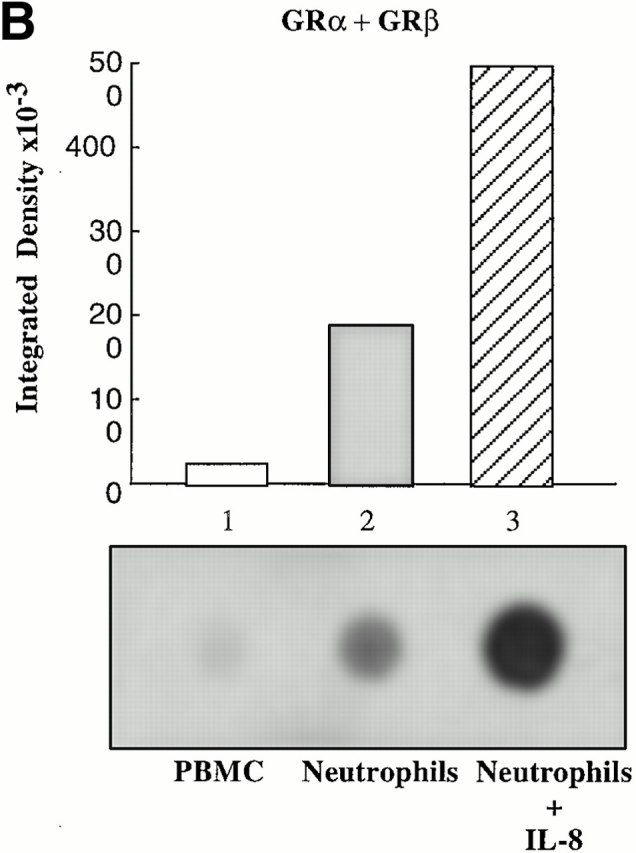

RNA Dot Blot Analysis.

Dot blot analysis of mRNA levels revealed that GRα mRNA in PBMCs was expressed at a higher level than GRβ mRNA (Fig. 4, lane 1). However, in neutrophils, GRβ mRNA was expressed at a greater level than GRα mRNA (Fig. 4, lane 2). After overnight stimulation of neutrophils with IL-8, there was an increase in total GR and GRβ mRNA levels. However, IL-8 reduced GRα mRNA to undetectable levels (Fig. 4, lane 3). Thus, the IL-8–induced increase in total GR in neutrophils can be attributed to increased GRβ.

Figure 4.

RNA dot blot analysis for GR mRNA in PBMCs and neutrophils. (A) RNA dot blot probed for the presence of exon 9α, which is only present in mRNA encoding GRα. Lane 1, cytoplasmic RNA from human PBMC; lane 2, cytoplasmic RNA from human neutrophils; and lane 3, cytoplasmic RNA from human neutrophils preincubated with IL-8. (B) RNA dot blot probed for the presence of exon 9β, which is present in mRNA encoding both GRα and GRβ. Lane 1, cytoplasmic RNA from human PBMCs; lane 2, cytoplasmic RNA from human neutrophils; and lane 3, cytoplasmic RNA from human neutrophils preincubated with IL-8. Relative density of the spots is represented graphically above each blot. These blots are representative of three experiments on three separate donors.

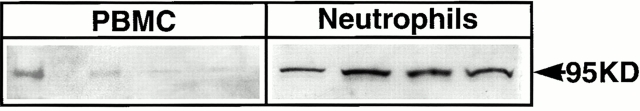

Presence of GRα/GRβ Heterodimers in Neutrophils.

High levels of GRβ may contribute to the formation of GRα/GRβ heterodimers in neutrophils which could antagonize the function of GRα/GRα homodimers 13 17 19. Therefore, we sought to determine the presence of heterodimers in neutrophils. An anti-GRα antibody was used to immunoprecipitate both GRα and complexes containing GRα. The immunoprecipitate was electrophoresed on an agarose gel and then immunoblotted with an antibody specific for GRβ to detect GRα/GRβ heterodimers.

Neutrophils (Fig. 5, lanes 5–8) were found to contain markedly higher levels of GRα/GRβ heterodimers than found in PBMCs (Fig. 5, lane 1–4). Beads alone did not precipitate any GRα or GRβ (data not shown). These data demonstrate that GRα/GRβ heterodimers are present in freshly isolated neutrophils at higher levels than found in PBMCs.

Figure 5.

GRα/GRβ heterodimers are present in neutrophils. The GRα protein in neutrophils and PBMCs were immunoprecipitated with a GRα-specific antibody, then Western blotted with an anti-GRβ–specific antibody. PBMCs showed weak bands indicating low levels of heterodimers (lanes 1–4). In contrast, neutrophils demonstrated strong GRβ staining, indicating a high level of GRα/GRβ heterodimers (lanes 5–8).

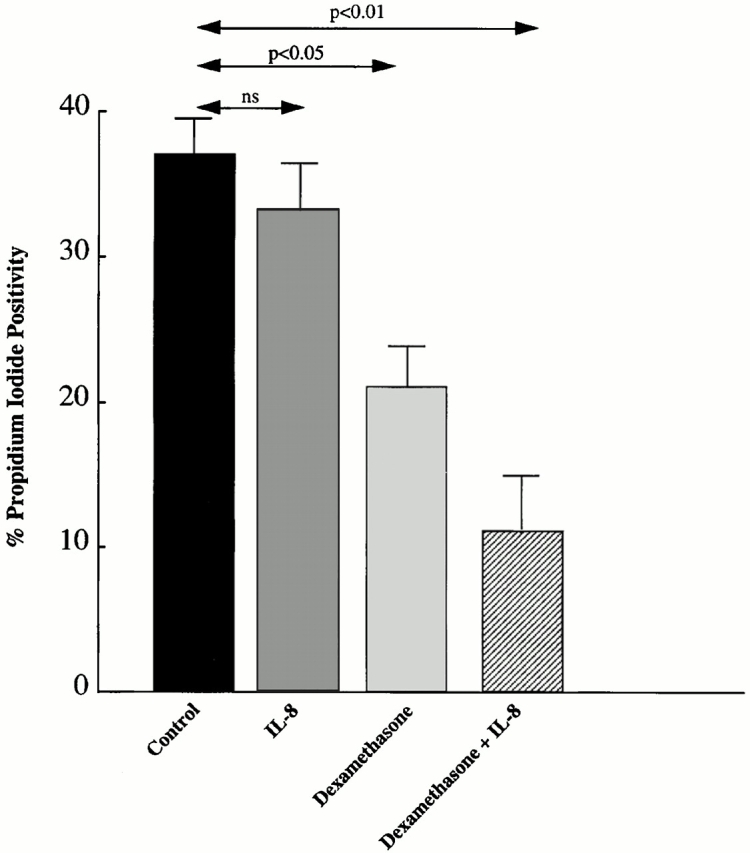

Effect of Dexamethasone and IL-8 on Neutrophil Cell Death.

Given the observation of heterodimer formation between GRα and GRβ in human neutrophils, which could result in antagonism of GR activity, we examined neutrophils for their apoptotic responses to DEX in the presence and absence of IL-8. This analysis was performed using PI to stain dead cells in the population, which correlated well with TUNEL analysis, indicating that the cells had died via apoptosis. No significant reduction in the percentage of PI-positive cells was observed by incubation with IL-8 alone compared with the control (Fig. 6). However, incubation with DEX caused a significant decrease in PI-positive cells compared with the control (P < 0.05). This rescue from cell death was further increased by incubation with IL-8 and DEX together (P < 0.01; Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

The effect of IL-8 and/or DEX on human neutrophil spontaneous cell death. No significant reduction in the percentage of PI-positive cells was observed by incubation with IL-8 alone. However, incubation with DEX showed a significant decrease in PI-positive cells compared with the control. Moreover, this rescue from cell death was further increased by incubation with IL-8 and DEX together.

Transfection of Murine Neutrophils with pRSh GRβ Expression Vector Alters Their Response to DEX.

The association between elevated GRβ and reduced apoptosis in response to DEX raised the question of whether GRβ directly enables neutrophils to reduce their rate of apoptosis in response to DEX. As it is known that mice do not express GRβ, they make an ideal model in which to temporarily cause expression of GRβ to answer this question 24.

Transient expression of human GRβ in primary murine neutrophils required development of a method to efficiently introduce plasmid DNA into the cells. To accomplish this, we relied on transient permeabilization of the cells with streptolysin O, which has been employed in a similar manner by others 22 23. Permeabilization of the neutrophils in the presence of plasmid DNA encoding GFP under control of the CMV immediate early promoter resulted in efficient uptake and expression of the plasmid (Fig. 7). Plasmid transfection efficiency was 63 ± 10% (mean ± SEM) as assessed by measuring the percentage of cells expressing GFP (Fig. 7 B). Cells that had been treated with streptolysin O in the presence of a control plasmid, which did not encode GFP, showed no fluorescence (Fig. 7 D).

Figure 7.

Transfection of mouse neutrophils with either pGFP or pRSh GRβ induces human GRβ protein expression. A (bright field) and B (fluorescence) show mouse neutrophils transfected with pGFP. Positive cells (green fluorescence) are observed in B. Negative cells (blue fluorescence) was visualized by counterstaining with DAPI (see Materials and Methods). Transfection efficiency was 63% in the experiment shown. Transfection efficiency was measured in two additional experiments, and found to vary from 63 to 70%. C (bright field) and D (fluorescence) show mouse neutrophils transfected with pCLeco as a control. Negative cells are observed in D (×40 objective). E are pRSh GRβ mouse neutrophils stained with a negative control antibody (rabbit IgG). Weak background staining is observed. F shows pRSh GRβ transfected neutrophils with many GRβ positively stained cells (×60 objective).

In contrast to the antiapoptotic effect of DEX on human neutrophils, treatment of mouse neutrophils with DEX increased their rate of cell death as measured by PI uptake (see Fig. 8; control pGFP). Unstained cells from each test sample served as a negative control to allow appropriate gating. To examine whether this effect could be due to the lack of GRβ expression in these cells, freshly isolated neutrophils from BALB/c mice were transfected with pRSh GRβ. In these experiments (n = 7), successful transfection was confirmed by demonstrating murine neutrophils to stain positive with anti-GRβ antibody after pRSh GRβ (Fig. 7 F), but not control (Fig. 7 E), plasmid transfection. This difference between the two plasmid treatments was found to be highly significant (P < 0.001) as determined by a paired Student's t test.

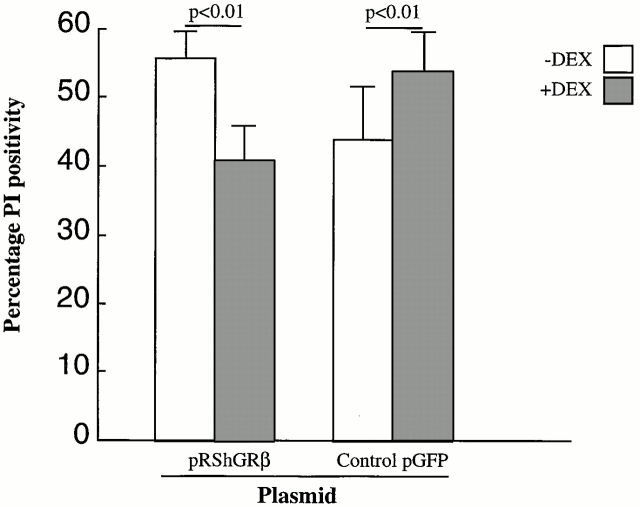

Figure 8.

Effect of pRSh GRβ vs. pGFP transfection on DEX-induced cell death by mouse neutrophils as measured by PI uptake. This shows the change in neutrophil PI positivity after DEX treatment in neutrophils transfected with either pRSh GRβ or control pGFP. Neutrophils transfected with pRSh GRβ showed a decrease in PI positivity as opposed to the control pGFP-treated neutrophils where an increase in PI positivity was observed.

As shown in Fig. 8, treatment of the transfected neutrophils with DEX caused the cells treated with control plasmid pGFP to increase their rate of cell death by 9.4 ± 3.2%, similar to untreated murine neutrophils. However, cells transfected with pRSh GRβ decreased their rate of cell death in response to DEX by 13.7 ± 3.5%.

Discussion

The mechanism by which neutrophils respond differently than T cells to glucocorticoids has not been resolved, although it is generally agreed that the GR must be intimately involved. Kato et al. 25 demonstrated that treatment of neutrophils with DEX significantly inhibited both spontaneous and TNF-α–induced cell death. Moreover, this effect was completely reversed by a GR antagonist, RU 38486, and by cycloheximide. Similarly, Liles et al. 8 demonstrated that glucocorticoid treatment of neutrophils could inhibit cell death by up to 90%. GRβ attenuates GRE-mediated pathways 14 and may therefore provide a natural mechanism for reducing glucocorticoid-induced cell death. The results of our studies confirm that DEX causes a reduction in the rate of spontaneous cell death by neutrophils. In addition, we have made a novel observation that preincubation of neutrophils with IL-8 dramatically enhances the protective effect of DEX.

These studies also illustrate that the ratio of GRβ to GRα is 73-fold greater in neutrophils than in PBMCs (Fig. 3). This reflects differences observed in relative abundance of the mRNAs (Fig. 4). If an activity of GRβ is to attenuate GR binding and activation of GRE in response to DEX, we would expect to find GRα/GRβ heterodimers in neutrophils after incubation with DEX, which were indeed much more abundant in neutrophils than in PBMCs (Fig. 5). Heterodimers have only 15–20% of the transactivating activity of GRα homodimers 13. The rate of cell death in T lymphocytes is thought to be mediated through GRα homodimers acting on GREs of glucocorticoid-sensitive genes 26. If the same mechanism is active in neutrophils, then the net effect of promoter activation via GRα homodimers binding to GRE should be to promote cell death. However, DEX acts contrary to expectations in human neutrophils by promoting cell survival. In our studies, the prosurvival activity of DEX is associated with elevated GRβ in freshly isolated neutrophils, perhaps through formation of GRα/GRβ heterodimers (Fig. 5). When the GRβ to GRα ratio is increased after incubation with IL-8, the prosurvival effect of DEX is increased (Fig. 6).

Although the prosurvival effect of DEX on human neutrophils is associated with elevated levels of GRβ, additional evidence is required to assert that GRβ is functionally responsible for this effect. To properly confirm that GRβ is responsible for the prosurvival effects of DEX on neutrophils, it is useful to examine the effect of DEX on neutrophils which completely lack GRβ. As it is known that mouse cells do not express the GRβ isoform of the GR 24, the mouse makes an ideal model for studying the role of GRβ in neutrophils in response to glucocorticoids. It is known that endogenous steroids such as cortisol can differ in both magnitude and mechanism of action; however, in this study DEX was chosen as the model steroid. Our data indicate that in contrast to human neutrophils, mouse neutrophils increase their rate of cell death in response to DEX (Fig. 8). This indicates that in the absence of GRβ, mouse neutrophils respond to DEX in the same manner as human PBMCs. However, there may be other important differences between human and murine neutrophils, and therefore proof of a functional role for GRβ in neutrophils requires that inducing GRβ expression in mouse neutrophils causes the effect of DEX to switch from promotion of cell death to promotion of cell survival.

To induce GRβ expression in murine neutrophils, we had to develop a method to efficiently transfect this cell type, which has not previously been reported. After extensive screening of lipid-based transfection reagents and conditions for electroporation, we succeeded in transfecting primary murine neutrophils using streptolysin O to transiently permeabilize the cells in the presence of an pGFP expression vector driven by the CMV immediate early promoter. As shown in Fig. 7 B, this technique resulted in ∼63% of the cells expressing GFP, 18 h after transfection.

Inducing GRβ expression in mouse neutrophils via transfection of pRSh GRβ was also successful, as shown in Fig. 7 F. In fact, the observed transfection efficiency may have been somewhat higher due to the greater fluorescence quantum yield of the Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody used to detect GRβ relative to GFP. Induction of human GRβ expression in murine neutrophils did indeed alter the effect of DEX on them from promoting cell death, as in human PBMCs, to promoting cell survival, as in human neutrophils. Therefore, induction of GRβ expression in mouse neutrophils resulted in a steroid insensitivity pattern similar to that of human neutrophils.

Whether GRβ has a functional role in steroid resistance has been a matter of major controversy. Bamberger et al. 14 and Oakley et al. 17 18 have both found that transfecting increasing amounts of GRβ expression vectors into various cell types inhibits the transactivating ability of Grα. The main argument against this isoform having a functional role is its lack of a steroid binding domain. De Lange et al. 27 showed that even in the presence of 10-fold excess of GRβ, GRα was still able to activate transcription from the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter at the same rate. Similarly, Hecht et al. 28 were unable to demonstrate an inhibitory role for GRβ when transfected into COS7 cells. These discrepant results may be explained by the use of different vector systems, differences in cell or tissue specificity, or insufficient GRβ expression due to the transient transfection method used. Work presented in our study further delineates the mode of GRβ action and demonstrates a physiological role for this receptor in neutrophils.

The data presented in this study demonstrate for the first time a role for GR in neutrophils. This observation implies an interaction between this receptor and DEX despite the absence of a glucocorticoid binding domain. One possible explanation of this would be through GRβ complexing with GRα/DEX and exerting a cellular effect via formation of a heterodimer which is distinct from that of the homodimer rather than simply attenuating transcription from GREs. Moreover, as GRβ was found to be the predominant GR isoform in neutrophils, it follows that heterodimer, rather than homodimer, formation would be favored in these cells. Oakley et al. 17 demonstrated that use of a truncated form of GRβ (hGR728T) which lacked the unique 15 amino acids at the COOH terminus does not repress the transcriptional activity of GRα. This final portion of the GRβ is also important in the heterodimerization with GRα. The authors hypothesized that heterodimer formation may reduce the transcriptional activity of GRα by denying access to GREs. An alternative explanation may be that different glucocorticoid-induced signaling pathways (one inducing apoptosis that can be inhibited by GRβ, and one reducing apoptosis that can not be inhibited by GRβ) may be used in cells expressing high levels of GRβ. The first pathway may be GRE dependent and the latter dependent on interaction of GR with other transcription factors like activating protein 1 (AP-1) or nuclear factor (NF)-κB, as the latter mechanism can not be inhibited by GRβ 29.

In conclusion, the elevated GRβ to GRα ratio in freshly isolated neutrophils provides a novel mechanism by which neutrophils escape glucocorticoid-induced cell death in vivo. Moreover, the inflammatory environment in itself may increase neutrophil insensitivity by increasing the ratio of GRβ to GRα, promoting further heterodimer formation. These data suggest that strategies aimed at reducing expression of GRβ in neutrophils may provide a starting point for the development of novel antiinflammatory treatments for neutrophil-associated disease.

Acknowledgments

A special thanks to Peter Henson and his research group at National Jewish Medical and Research Center for their help in preparation of neutrophils and advice on critical experiments in this paper. The authors also wish to thank Maureen Sandoval for her kind assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants HL36577, AR41256, HL37260, and HL34303, General Clinical and Research Center grant MO1 RR00051 from the Division of Research Resources, an American Lung Association Asthma Research Center Grant, and the University of Colorado Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: DEX, dexamethasone; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; pGFP, plasmid green fluorescent protein; PI, propidium iodide; pRSh, plasmid Rous sarcoma (human); TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP-biotin nick end-labeling.

References

- Wenzel S.E., Szefler S.J., Leung D.Y.M., Sloan S.I., Rex M.D., Martin R.J. Bronchoscopic evaluation of severe asthma. Persistent inflammation associated with high dose glucocorticoids. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1997;156:737–743. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.3.9610046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jatakanon A., Uasuf C., Maziak W., Lim S., Chung K.F., Barnes P.J. Neutrophilic inflammation in severe persistent asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1999;160:1532–1539. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.5.9806170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier F., Gross E., Klotz K.N., Ruzicka T. Leukotriene B4 receptors on neutrophils in patients with psoriasis and atopic eczema. Skin Pharmacol. 1989;2:61–67. doi: 10.1159/000210802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coble B.I., Briheim G., Dahlgren C., Molin L. Function of exudate neutrophils from skin in psoriasis. Int. Arch. Allergy Appl. Immunol. 1988;85:398–403. doi: 10.1159/000234541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkebaum G. Use of colony-stimulating factors in the treatment of neutropenia associated with collagen vascular disease. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 1997;4:196–199. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199704030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu P., Connolly M.K., LeBoit P.E. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch. Dermatol. 1994;130:1278–1283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleimer R.P. Effects of glucocorticosteroids on inflammatory cells relevant to their therapeutic applications in asthma. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1990;141:S59–S69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liles W.C., Kiener P.A., Ledbetter J.A., Aruffo A., Klebanoff S.J. Differential expression of Fas (CD95) and Fas ligand on normal human phagocytesimplications for the regulation of apoptosis in neutrophils. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:429–440. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox G., Austin R.C. Dexamethasone-induced suppression of apoptosis in human neutrophils requires continuous stimulation of new protein synthesis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1997;61:224–230. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Baldassarre A., Secchiero P., Grilli A., Celeghini C., Falcieri E., Zauli G. Morphological features of apoptosis in hematopoietic cells belonging to the T-lymphoid and myeloid lineages. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2000;46:153–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negoescu A., Guillermet C., Lorimier P., Brambilla E., Labat-Moleur F. Importance of DNA fragmentation in apoptosis with regard to TUNEL specificity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 1998;52:252–258. doi: 10.1016/S0753-3322(98)80010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom J.W. New insights into the molecular basis of glucocorticoid action. In: Szefler S.J., Leung D.Y.M., editors. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. W.B. Saunders Co; Philadelphia, PA: 1999. pp. 653–670. [Google Scholar]

- de Castro M., Elliot S., Kino T., Bamberger C., Karl M., Webster E., Chrousos G.P. The non-ligand binding beta-isoform of the human glucocorticoid receptor (hGR beta)tissue levels, mechanism of action, and potential physiologic role. Mol. Med. 1996;2:597–607. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamberger C.M., Bamberger A.M., de Castro M., Chrousos G.P. Glucocorticoid receptor beta, a potential endogenous inhibitor of glucocorticoid action in humans. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;95:2435–2441. doi: 10.1172/JCI117943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giguere V., Hollenberg S.M., Rosenfeld M.G., Evans R.M. Functional domains of the human glucocorticoid receptor. Cell. 1986;46:645–652. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90339-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Encio I.J., Detera-Wadleigh S.D. The genomic structure of the human glucocorticoid receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:7182–7188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley R.H., Sar M., Cidlowski J.A. The human glucocorticoid receptor beta isoform. Expression, biochemical properties, and putative function. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:9550–9559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley R.H., Jewell C.M., Yudt M.R., Bofetiado D.M., Cidlowski J.A. The dominant negative activity of the human glucocorticoid receptor beta isoform. Specificity and mechanisms of action. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:27857–27866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala A., Zarini S., Folco G., Murphy R.C., Henson P.M. Differential metabolism of exogenous and endogenous arachidonic acid in human neutrophils. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:28264–28269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modarress K.J., Opoku J., Xu M., Sarlis N.J., Simons S.S., Jr. Steroid-induced conformational changes at ends of the hormone-binding domain in the rat glucocorticoid receptor are independent of agonist versus antagonist activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:23986–23994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung D.Y.M., Hamid Q., Vottero A., Szefler S.J., Surs W., Minshall E., Chrousos G.P., Klemm D.J. Association of glucocorticoid insensitivity with increased expression of glucocorticoid receptor beta. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:1567–1574. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton C.M., Spiller D.G., Pender N., Komorovskaya M., Grzybowski J., Giles R.V., Tidd D.M., Clark R.E. Preclinical studies of streptolysin-O in enhancing antisense oligonucleotide uptake in harvests from chronic myeloid leukemia patients. Leukemia. 1997;11:1435–1441. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller D.G., Tidd D.M. Nuclear delivery of antisense oligodeoxynucleotides through reversible permeabilization of human leukemia cells with streptolysin O. Antisense Res. Dev. 1995;5:13–21. doi: 10.1089/ard.1995.5.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto C., Reichardt H.M., Schutz G. Absence of glucocorticoid receptor-beta in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:26665–26668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T., Takeda Y., Nakada T., Sendo F. Inhibition by dexamethasone of human neutrophil apoptosis in vitro. Nat. Immun. 1995;14:198–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt H.M., Kaestner K.H., Tuckermann J., Kretz O., Wessely O., Bock R., Gass P., Schmid W., Herrlich P., Angel P., Schutz G. DNA binding of the glucocorticoid receptor is not essential for survival. Cell. 1998;93:531–541. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange P., Koper J.W., Huizenga N.A., Brinkmann A.O., de Jong F.H., Karl M., Chrousos G.P., Lamberts S.W. Differential hormone-dependent transcriptional activation and -repression by naturally occurring human glucocorticoid receptor variants. Mol. Endocrinol. 1997;11:1156–1164. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.8.9949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht K., Carlstedt-Duke J., Stierna P., Gustafsson J., Bronnegard M., Wikstrom A.C. Evidence that the beta-isoform of the human glucocorticoid receptor does not act as a physiologically significant repressor. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:26659–26664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogan I.J., Murray I.A., Cerillo G., Needham M., White A., Davis J.R. Interaction of glucocorticoid receptor isoforms with transcription factors AP-1 and NF-kappaBlack of effect of glucocorticoid receptor beta. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 1999;157:95–104. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]