Abstract

Manganese superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) is a critical component of the mitochondrial pathway for detoxification of O2 −, and targeted disruption of this locus leads to embryonic or neonatal lethality in mice. To follow the effects of SOD2 deficiency in cells over a longer time course, we created hematopoietic chimeras in which all blood cells are derived from fetal liver stem cells of Sod2 knockout, heterozygous, or wild-type littermates. Stem cells of each genotype efficiently rescued hematopoiesis and allowed long-term survival of lethally irradiated host animals. Peripheral blood analysis of leukocyte populations revealed no differences in reconstitution kinetics of T cells, B cells, or myeloid cells when comparing Sod2 +/+, Sod2 −/−, and Sod2 +/− fetal liver recipients. However, animals receiving Sod2 −/− cells were persistently anemic, with findings suggestive of a hemolytic process. Loss of SOD2 in erythroid progenitor cells results in enhanced protein oxidative damage, altered membrane deformation, and reduced survival of red cells. Treatment of anemic animals with Euk-8, a catalytic antioxidant with both SOD and catalase activities, significantly corrected this oxidative stress–induced condition. Such therapy may prove useful in treatment of human disorders such as sideroblastic anemia, which SOD2 deficiency most closely resembles.

Keywords: transplantation (fetal liver), oxidative stress, antioxidant, stem cells, SOD2

Introduction

Manganese superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) is a nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein that converts superoxide radicals to H2O2, which is then acted upon by glutathione peroxidase or catalase to yield nontoxic products 1. Similar enzymes have been isolated from the cytoplasm (SOD1 or CuZnSOD) and extracellular fluids (SOD3; reference 2). Together, these enzyme systems are responsible for protecting cells from reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated from endogenous and exogenous sources. Endogenous ROS produced by mitochondria as a by-product of respiration are proposed to be a major causal factor in organismal aging and cellular senescence. Support for this hypothesis comes from studies of model organisms in which increased longevity has been correlated with the enhanced ability to withstand oxidative stress 3 4 5, or with decreased endogenous production of ROS 6 7. Conversely, impairment of an organism's ability to withstand oxidative stress, or increased generation of endogenous ROS, leads to a shortened life span characterized by accelerated aging phenotypes 8 9. The relevance of oxidative stress as a determinant of mammalian longevity is supported by a recent study demonstrating that an oxidative stress–activated signal transduction pathway is linked to apoptosis and regulates life span in mice 10. The possibility of altering longevity through pharmacological intervention to ameliorate ROS-induced damage has also been explored in a recent study in which Caenorhabiditis elegans were treated with a novel class of antioxidants placed directly into the growth medium, resulting in extension of mean life span by >40% 11.

Sod2 knockout mice were originally produced independently on two separate strain backgrounds 12 13, both of which demonstrate a lethal phenotype in which the time of death is dependent on the genetic background. Sod2 −/− animals have pathologic evidence of mitochondrial injury, with corresponding evidence of damage to cardiac muscle and neural tissues as well as metabolic derangement including acidosis and lipid accumulation. A partial rescue of this phenotype has been reported by using the synthetic SOD mimetic manganese 5, 10, 15, 20-tetrakis(4-benzoic acid) porphorin (MnTBAP), although treated animals succumb to neural degeneration within several weeks of birth, presumably because of failure of this agent to cross the blood–brain barrier 14. In addition to early lethality, Sod2 −/− animals have increased oxidative DNA damage and respiratory chain defects in mitochondria 15. Heterozygous animals appear normal, but also show oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA, decreased levels of reduced glutathione, and altered mitochondrial function 16 17. Thus, Sod2-deficient mice demonstrate evidence of increased damage from mitochondrial ROS, but because of the severe and pleiotropic nature of the defect in Sod2 −/− animals, it has not been possible to study the effects of SOD2 deficiency in cells over long periods of time in vivo.

To circumvent this problem, we constructed a transplant system in which Sod2 −/− cells replace host hematopoietic cells and can be maintained for several months in vivo. This system places Sod2-deficient cells in a metabolically normal host animal, allowing for the assessment of cell autonomous phenotypes caused by increased intracellular damage from mitochondrial ROS. This makes possible an assessment of the specific role of mitochondrial antioxidant protective systems on immune and hematopoietic cell reconstitution and function. We report that murine fetal liver stem cells deficient in Sod2 are capable of efficiently rescuing lethally irradiated host animals. However, whereas lymphoid and myeloid engraftment kinetics and durability are identical across all Sod2 fetal liver genotypes (+/+, −/−, and +/−) there is a selective defect in erythroid reconstitution of Sod2 −/− fetal liver recipients. This defect is similar to that seen clinically in hereditary and acquired sideroblastic anemias (SAs), which are believed to involve abnormal oxidation of red cell proteins and which may be caused by defects in mitochondria 18 19.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Donor Cells for Fetal Liver Transplantation.

Heterozygous B6-Sod2 tm1Cje mice 12 were bred in timed matings in order to obtain Sod2 −/−, Sod2 +/−, and Sod2 +/+ littermates at E13.5-16.5 of development to serve as donors for fetal liver cell transplantation. Animals (two females, one male) were placed together for two or three consecutive nights, after which time males were removed. Pregnant females were killed on the 17th morning after the introduction of the male. Embryos were harvested, and fetal livers were dissected. All fetal livers were mechanically dissociated into a single cell suspension by pipetting up and down using an Eppendorf p-1000 pipette in 1 cc of culture medium (RPMI, 7% FCS, glutamine, penicillin-streptomycin, and 10−5 M betamercapto-ethanol). 5% of each sample was used for DNA extraction followed by PCR analysis for genotyping. Knockout (Sod2 −/−) fetuses were often more pale than +/− or +/+ littermates at the time of harvest, but were otherwise indistinguishable. At E13.5-16.5, 15% of genotyped animals were Sod2 −/−, consistent with a previous report of decreased frequency of Sod2 −/− pups at birth on the C57BL/6 background 20. Variations in the time of fertilization do lead to differences in the size and developmental stage of harvested fetuses. However, we have not noted any variation between experiments in the ability of a fixed dose of 106 fetal liver cells to rescue lethally irradiated host animals.

Genotyping at Sod2 Locus Using PCR.

DNA was extracted from fetal liver cell suspensions using a DNA isolation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Gentra Systems). PCR was performed using the following primer pairs: wild-type specific sequence 5′-AGG GCT CAG GTT TGT CCA GAA AAT-3′ and common primer 5′-CGA GGG GCA TCT AGT GGA GAA GT-3′; SOD mutation 5′-TTT GTC CTA CGC ATC GGT AAT GAA-3′ and common primer as above. PCR conditions were: 95°C for 2 min followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72°C of 4 min.

Host Animal Conditioning and Fetal Liver Transplantation.

C57BL/6 mice congenic at the Ly5 locus (B6.SJL-PtprcaPep3b/BoyJ[Ly5.1]) were obtained from the National Cancer Institute and were used as recipients in order to allow for differentiation of host (Ly5.1) versus donor (Ly5.2) hematopoietic cells. Ly5.1 host animals (age 11–15 wk) were subjected to 10.50 cGy (1,050 rad) of gamma irradiation divided into two equal doses 4 h apart on the day of transplant. 106 fetal liver cells, prepared as noted above, were injected intravenously (either into tail vein or infraorbital sinus) into irradiated Ly5.1 congenic recipients. Animals were maintained on chlorinated water for 21 d after irradiation. All experiments were approved by the Animal Use Committee.

Analysis of Fetal Liver Cell Engraftment.

After recovery from transplantation, mice were bled at 3–4 wk and every 4–8 wk thereafter to assess the donor contribution to peripheral T cells, B cells, granulocytes, and macrophages. Transplanted Ly5.1 mice were bled from the ocular venus sinus, and ∼250 μl of blood was collected into 0.5 cc of PBS/EDTA (3 mg/ml EDTA). Samples were then mixed with 0.5 cc of dextran T-500 in PBS (2% dextran) and allowed to sediment for 30 min at 37°C. Leukocytes were recovered in the supernatant and were mixed with one volume of a 1:4 dilution of saline/water to lyse remaining red cells. After 5 min, one volume of 1.9% saline was added, and the samples were spun down to pellet leukocytes. Cells were resuspended in FACS® wash solution (PBS, 3% heat inactivated bovine serum, 0.02% sodium azide) with Fc block (BD PharMingen). After 15 min, the cells were mixed with an equal volume of biotinylated anti–mouse CD45.2 (Ly 5.2) antibody (BD PharMingen). After 30 min, the cells were washed, spun down, and aliquoted into mixtures containing streptavidin R-PE (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc.) and either FITC-labeled CD90.2 for T cells, FITC-labeled CD45RA for B cells, or a combination of FITC-labeled CD11b and FITC-labeled Ly-6G for myeloid cells (all from BD PharMingen). After 30 min, cells were washed and resuspended in FACS® wash solution plus propidium iodide for FACS® analysis on a FACStar™ machine (Becton Dickinson).

Western Blot Analysis of MnSOD, CuZnSOD, and Porin Proteins.

Polyclonal rabbit antisera specific for CuZnSOD and MnSOD (StressGen Biotechnologies) were used to blot whole cell lysate and red cell lysate obtained from fetal liver transplant recipients. Anti-porin antibody was obtained from Calbiochem. Bone marrow from transplanted animals was used as a source of nucleated cells in order to obtain an estimate of the ratio between porin and CuZnSOD and porin and MnSOD. Second stage horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti–rabbit antibody and anti–mouse antibody were obtained from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech.

Protein Oxidation in Red Cells of Transplanted Animals.

Red cell lysate proteins (20 μg protein/reaction) from Sod2 +/+, Sod2 +/−, and Sod2 −/− transplant recipients were reacted with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine to derivatize carbonyl groups formed through protein oxidation using oxyblot reagents (Intergen). Control samples were treated identically, except 2,4-dinitropheylhydrazine was omitted. Proteins were then subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot detection of derivatized residues according to the oxyblot protocol. Samples were normalized for protein concentration and verified by secondary blotting for SOD1.

Therapeutic Trial of EUK-8 in Transplanted Mice.

EUK-8 was provided by Eukarion. EUK-8 powder was resuspended in sterile 5% dextrose at a concentration of 3 mg/ml and passed through a 0.2-micron sterile filter. For the experiment detailed in Fig. 6, mice were transplanted 13 wk before initiation of Euk-8 therapy. Peripheral blood samples were obtained at 4 and 8 wk after transplant to verify reconstitution with donor (Ly5.2)-derived cells. Mice were weighed and bled at 13 wk to determine EUK-8 dosage and to obtain a baseline complete blood count (CBC). Animals received either 30 mg/kg EUK-8 3 d/wk, or vehicle alone via intraperitoneal injection, on the same schedule for a total of 8 wk. Mice were bled again at 4 and 8 wk for hematocrit, reticulocyte count, and blood smear.

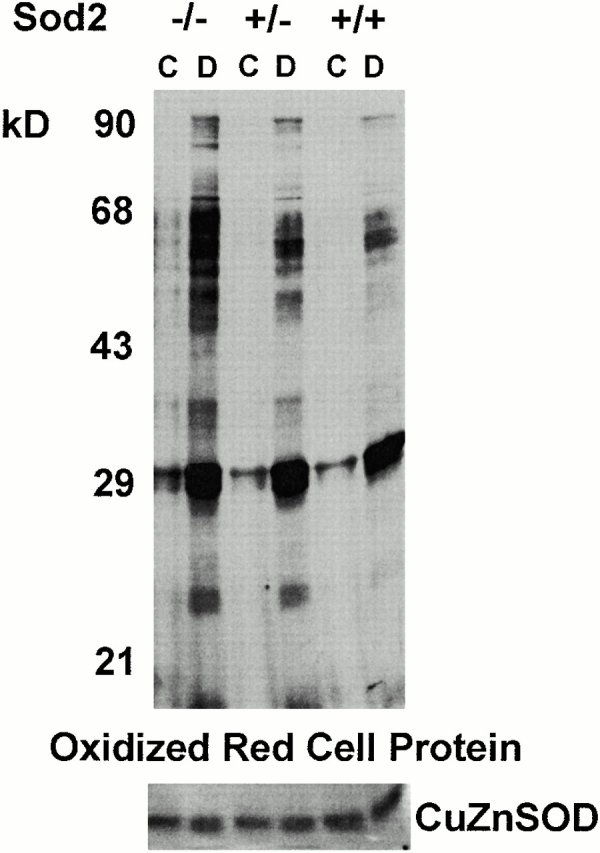

Figure 6.

Comparison of oxidized protein among transplanted RBCs. 20 μg of protein from RBC lysates of Sod2 −/−, Sod2 +/+, and Sod2 +/− fetal liver transplant recipients was reacted with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine to derivatize (D) protein carbonyl groups, which were then detected using an anti-DNP antibody. 20 μg of each protein sample was incubated in reaction buffer alone to serve as a control (C). RBC proteins from Sod2 −/− recipients have higher levels of oxidized protein residues. Secondary blotting using antisera against SOD1 was performed to verify equivalent protein loading (bottom panel).

Measurement of RBC Half-life.

Animals were transplanted 4 mo before RBC labeling to ensure that no residual pretransplant host red cells remained. Animals were bled 5 wk before RBC labeling and demonstrated 100% donor-derived B cells, ∼85% donor-derived T cells, and ∼90% donor-derived myeloid cells. N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)-biotin (E-Z link; Pierce Chemical Co.) was suspended in sterile saline at a concentration of 4 mg/ml and injected intravenously into fetal liver transplant recipients. Animals received a total dose of 30–40 mg/kg of body weight in a volume of 200–250 μl. Animals were first bled ∼36 h after injection, and then at 2–3-d intervals for the first 2 wk, followed by 3–4-d intervals for the third and fourth weeks, then weekly twice more. Care was taken to obtain the smallest amount of blood possible, typically 5–10 μl with each blood sampling. Labeled cells were analyzed by FACS® after staining with streptavidin R-PE. The exponential curve showing both age-dependent and -independent processes was fitted to the equation: A(t) = A 0[1 − (t/T)]e− kt (reference 21), where A(t) is the fraction of labeled RBCs present at time (t), A 0 is the initial fraction of labeled RBCs at t = 0, T is the time of senescent death of RBC (extinction time), and k is the fraction of cells which are removed independent of RBC age (hemolysis). In this experiment, k = 0 for Sod2 +/+ and Sod2 +/− cells, and k = 0.04 for Sod2 −/− cells.

Membrane Deformability.

Cellular deformability was monitored by ektacytometry using a Technicon ektacytometer (Bayer Diagnostics). The osmotic deformability curve was recorded as described previously 22.

Results

Reconstitution and Engraftment Kinetics.

Fetal liver cells for transplantation were generated by crossing Sod2 +/− animals. Initial transplants compared the reconstituting ability of fetal liver cells of each genotype (wild-type, heterozygous, or knockout at the Sod2 locus). Survival was 100% in all groups. Regardless of the genotype of the donor cells, >95% of peripheral blood B cells and >83% of peripheral blood myeloid cells were derived from the donor fetal liver cells at 3 wk after transplant. T cell engraftment was more gradual, with donor T cells first appearing in peripheral blood 3–4 wk after transplant. Donor-derived T cells continued to increase and reached 80–90% of all peripheral blood T cells by 3 mo after transplant. Throughout this experiment, B cell and myeloid engraftment has remained >90% and T cell engraftment >80% up to 1 yr after transplant, with no evidence of a difference in kinetics or duration of engraftment related to donor genotype. Thus, Sod2 −/− hematopoietic stem cells are capable of giving rise to normal numbers of T cells, B cells, and myeloid cells, and can maintain this cellular output for up to 1 yr with no evidence of a decline in graft function.

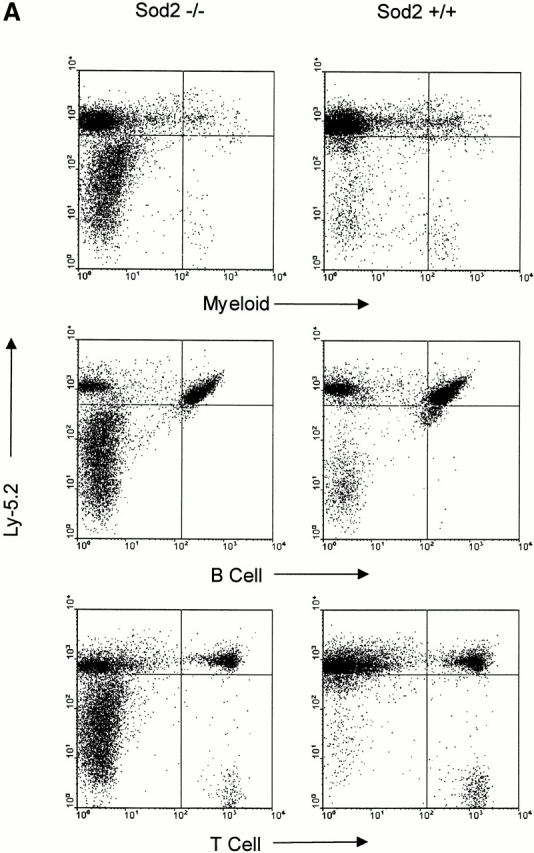

Reconstitution of Spleen, Bone Marrow, and Thymus.

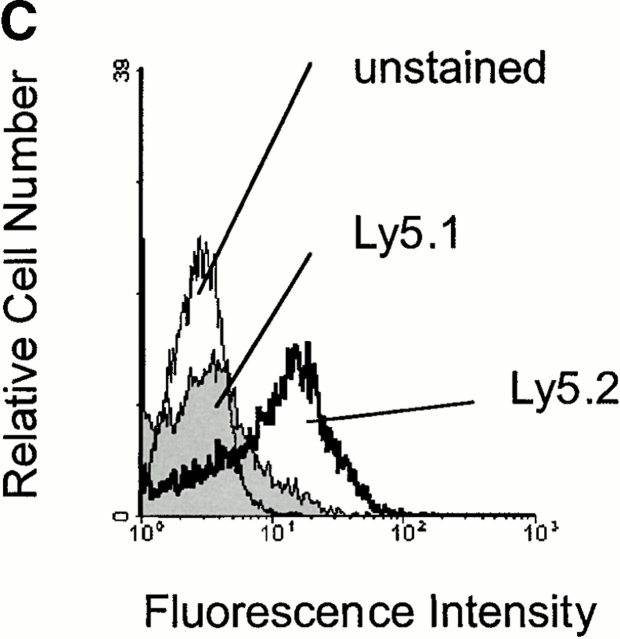

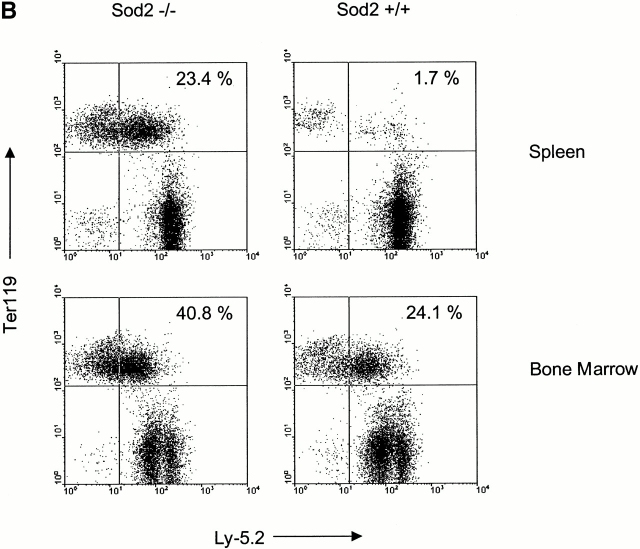

Hematolymphoid tissues from transplanted animals were harvested to investigate in more detail engraftment among recipients of Sod2 −/−, Sod2 +/−, and Sod2 +/+ fetal liver. Recipients of Sod2 −/− cells had larger spleens than animals receiving wild-type or heterozygous cells (4.2 × 108 vs. 2.3 × 108 cells/spleen; P = 0.02). There was no enlargement of the thymus, lymph nodes, or Peyer's patches compared with control transplanted animals. Fig. 1 A shows flow cytometric profiles of representative spleens from transplanted animals in which cells are simultaneously stained for the donor-specific marker CD45.2 (Ly5.2) and for one of the following lineage markers: Ly6G and CD11b for myeloid cells, CD45RA for B cells, and CD90.2 for T cells. Spleens from animals receiving Sod2 −/− cells had a large population of cells which did not stain for markers of B cells, T cells, granulocytes, or macrophages, but which did stain for the erythroid marker Ter119 (Fig. 1 B). These data demonstrated effective reconstitution in all lineages (as expected from the peripheral blood analysis) and revealed a greatly expanded population of erythroid precursors in the spleens of animals transplanted with Sod2 −/− fetal liver cells. This population represented 25–40% of the nucleated cells present in spleens from Sod2 −/− fetal liver recipients, compared with 1–5% of nucleated spleen cells from Sod2 +/+ fetal liver recipients. Splenic red cell precursors (Ter119+) were stained with CD45.2 (Ly5.2 or donor antigen) or CD45.1 (Ly5.1 or host antigen) to demonstrate that erythroid cells were also donor derived (Fig. 1 C). Analysis of the bone marrow revealed additional evidence for increased erythropoiesis in animals which received Sod2 −/− cells, with the Ter119 population representing 40–50% of nucleated marrow cells versus 20–30% of marrow cells in recipients of Sod2 +/+ or Sod2 +/− fetal liver cells (Fig. 1 B). Total marrow cell number in recipients of Sod2 −/− fetal liver was slightly increased compared with recipients of Sod2 +/+ fetal liver (range 1.0–1.25 times Sod2 +/+ cell number). Analysis of the thymus from reconstituted animals revealed no differences in cell number or CD4+ versus CD8+ profile, suggesting that lack of SOD2 does not significantly affect these measures of T cell reconstitution.

Figure 1.

FACS® analysis of hemato-lymphoid tissues from Sod2 −/− and Sod2 +/+ fetal liver recipients. (A) Splenocytes from transplanted animals were costained with antibodies against the donor-derived CD45.2 antigen and markers for myeloid cells (CD11b and Ly-6G), B cells (CD45RA), or T cells (CD90.2). Sod2 −/− fetal liver recipients have a large population of splenocytes that stain weakly for CD45.2 but do not express myeloid or lymphoid markers. (B) Splenocytes and bone marrow cells from recipients of Sod2 +/+ or Sod2 −/− fetal liver cells were costained with CD45.2 and the erythroid marker Ter119. The population shown in Sod2 −/− samples in panel A represents abundant erythroid precursors (23.4% of sample), which are nearly absent from Sod2 +/+ samples (1.7%). Analysis of bone marrow with the same markers reveals that Sod2 −/− recipients have increased erythroid progenitors in this compartment as well. (C) Erythroid lineage cells (Ter119+) from the spleen of a Sod2 −/− fetal liver recipient were co-stained with either FITC–anti-Ly5.1 (host) or FITC–anti-Ly5.2 (donor) to demonstrate that erythroid precursor cells are also donor derived.

Sod2−/− Fetal Liver Recipients Are Anemic.

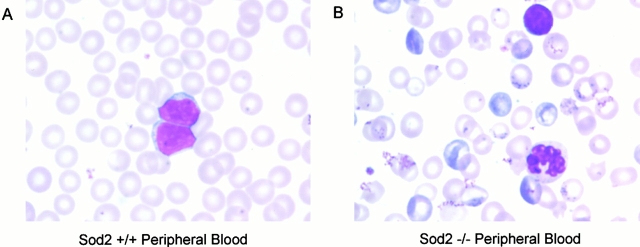

Analysis of peripheral blood and hematolymphoid tissues revealed normal lymphopoiesis and myelopoiesis, but suggested abnormalities restricted to the erythroid lineage. This was substantiated by comparison of CBCs from transplant recipients (obtained 3 mo after transplant) that showed animals reconstituted with Sod2 −/− fetal liver cells were anemic and had elevated circulating reticulocytes (P < 0.001). In addition to hematocrit, several parameters were abnormal in erythrocytes derived from Sod2 −/− fetal liver (Table ). Mature red cells in Sod2 −/− recipients were smaller and possessed less hemoglobin than those in control transplanted animals. Morphologic examination of peripheral blood smears (Fig. 2, Wright-Giemsa stain) suggested a hemolytic process affecting Sod2 −/− red cells. There was a marked reticulocytosis in Sod2 −/− peripheral blood, and variability in RBC size and shape. In addition, Sod2 −/− red cells had a high frequency of basophilic intracellular inclusions that were absent from Sod2 +/+ cells, and which did not appear to be Howell-Jolly bodies. Specific staining for Heinz bodies revealed that Sod2 −/−–derived cells possess more of these inclusions, thought to represent accumulation of oxidized proteins within erythrocytes (data not shown). White blood cell count, differential (not shown), and platelet counts were not statistically different among recipients of Sod2 +/+, Sod2 −/−, or Sod2 +/− fetal liver cells. We did not find consistent morphologic changes in leukocytes or platelets between Sod2 −/− and Sod2 +/+ smears. Together, the examination of peripheral blood from Sod2 −/− fetal liver recipients demonstrated an anemia with evidence of an ongoing hemolytic process.

Table 1.

CBC Comparison between Transplanted Animals

| Sod2+/+ | Sod2−/− | Sod2+/− | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percent hematocrit | 48.1 ± 0.6 | 31.8 ± 1.6 | 48.1 ± 1.2 |

| Percent reticulocyte | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 16 ± 2.8 | 2.6 ± 0.4 |

| Mean corpuscular volume (fl) | 50.1 ± 0.3 | 46.7 ± 1.0 | 48.1 ± 1.3 |

| Red cell count (×106) | 9.6 ± 0.2 | 6.8 ± 0.3 | 9.8 ± 0.3 |

| White cell count (×103) | 12.3 ± 1.7 | 12 ± 2.7 | 9.0 ± 2.6 |

| Platelet count (×103) | 1,075 ± 139 | 1,262 ± 137 | 1,062 ± 103 |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin (pg) | 14.9 ± 0.1 | 13.8 ± 0.4 | 14.5 ± 0.3 |

| Red cell distribution width | 13.2 ± 0.2 | 21.8 ± 0.9 | 13.2 ± 0.3 |

CBC comparisons of Sod2 +/+, Sod2 +/−, and Sod2 −/− fetal liver recipients. CBC was obtained 13 wk after fetal liver transplantation, and 5 wk after the most recent blood sampling for peripheral blood reconstitution assessment. For all parameters tested except MCV, there was no significant difference between Sod2 +/+ and Sod2 +/− fetal liver recipients. Sod2 −/− fetal liver recipients differ from Sod2 +/+ in hematocrit, reticulocyte count, MCV, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, and red cell distribution width.

Figure 2.

Wright-Giemsa stain of peripheral blood smears from transplanted animals. Morphologic comparison of peripheral blood demonstrates marked reticulocytosis and abnormal red cells in Sod2 −/− fetal liver recipients. Many Sod2 −/− RBCs have multiple prominent basophilic inclusions. There are many hypochromic cells, as well as variations in cell size and cell shape. Occasional Howell-Jolley bodies are seen in both the Sod2 +/+ and Sod2 −/− red cells.

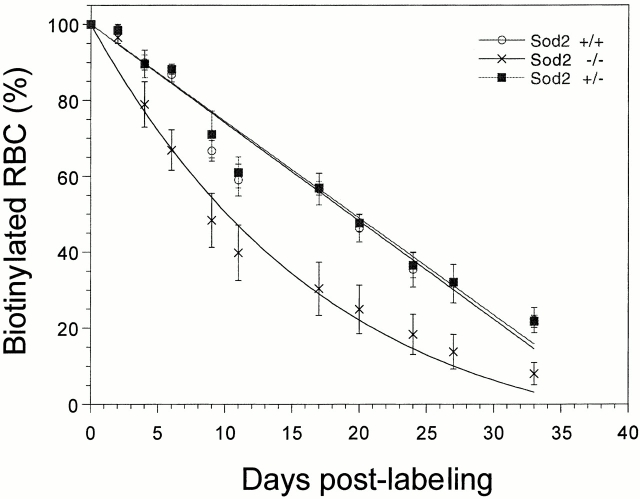

Red Cell Half-life Is Decreased for Cells That Lack SOD2.

The anemia observed in Sod2 −/− fetal liver recipients could be due to increased red cell destruction (hemolysis) or defective red cell maturation (ineffective erythropoiesis) or a combination of both processes. To measure more directly whether the observed anemia was due to decreased production of mature RBCs or increased destruction of RBCs in the circulation, we measured RBC survival in transplanted animals, using direct in vivo biotin labeling 23. RBC survival in Sod2 −/− and control fetal liver recipients was followed for 41 d in a random RBC labeling experiment. The survival curves plotted in Fig. 3 show that RBC removal was nearly linear for Sod2 +/+ and Sod2 +/− fetal liver recipients with a disappearance rate of 2.6% RBCs per day and with an extinction time of ∼40 d. In contrast, in the Sod2 −/− fetal liver recipients, an exponential removal of RBCs was noted, indicating that one component of RBC destruction was independent of RBC age. The time required for loss of 50% of labeled Sod2 +/+ and Sod2 +/− RBCs is 20 d, whereas the time required for loss of 50% of labeled Sod2 −/− RBCs is 10 d.

Figure 3.

Red cell survival curve. In vivo biotin labeling was used to follow red cell survival kinetics over a 6-wk period. Small samples (5 μl) of peripheral blood were collected and stained using streptavidin-PE, followed by FACS® analysis, to determine the fraction of labeled RBCs remaining. Sod2 +/+ and Sod2 +/− RBCs are lost in a linear fashion (2.6% per day) with an extinction time of ∼40 d. Sod2 −/− cells show a similar extinction time, but their removal curve has an exponential component.

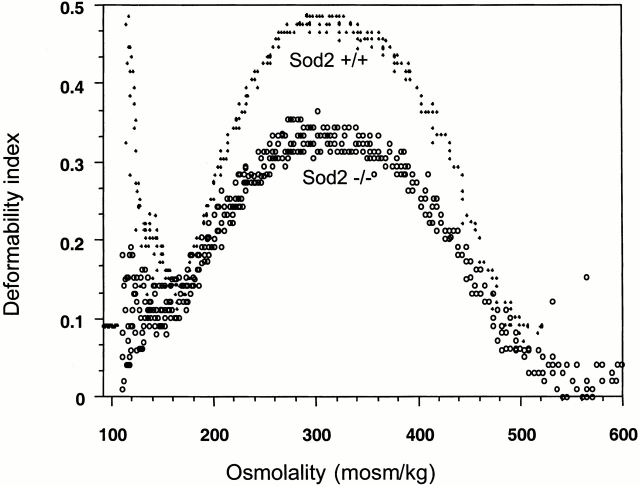

Red cell membrane flexibility is required for RBC function, and alterations in membrane characteristics can affect cell survival 24. Therefore, we determined the osmotic deformability profile of RBCs from fetal liver recipients. The combined curves of three Sod2 +/+ fetal liver recipient and four Sod2 −/− fetal liver recipient mice are shown (Fig. 4). A shift in the curve for Sod2 −/− versus Sod2 +/+ RBCs is apparent, with the Sod2 −/− cells showing reduced deformability under isotonic conditions. In addition to a smaller mean corpuscular volume (MCV), this shift may be due to a change in the mechanical properties of the membrane as indicated by the hypertonic arm of the curve, suggesting an overall increase in membrane stiffness. Altered membrane deformability and decreased red cell survival are both characteristics of the anemia that arises in animals transplanted with Sod2 −/− fetal liver stem cells. This raises the interesting question of how deficiency in a mitochondrial enzyme can shorten the half-life of a cell that does not possess mitochondria.

Figure 4.

Red cell membrane osmotic deformability curve. Osmotic deformability was determined by ektacytometry. The combined curves of red cells from three Sod2 +/+ and four Sod2 −/− fetal liver transplant recipients are shown. Sod2 −/− cells have reduced deformability compared with controls.

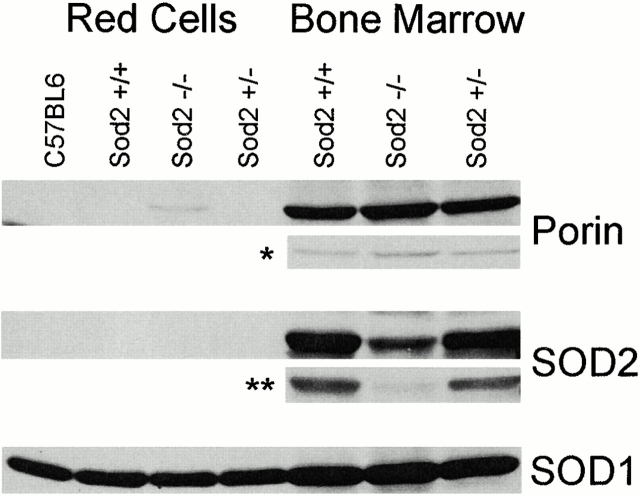

SOD2 Protein Expression and Mitochondrial Distribution in Bone Marrow Cells and Erythrocytes of Transplanted Animals.

To address the role of SOD2 protein deficiency as a cause of anemia, we determined the distribution of SOD2 and mitochondria in RBCs and marrow cells from transplanted animals (Fig. 5). We were unable to detect SOD2 in RBC protein from Sod2 +/+ fetal liver recipients except after prolonged exposure (data not shown), demonstrating that there is very little SOD2 present in RBCs. SOD1, which is known to be abundant in RBCs, was highly and equally expressed in all samples. Examination of nucleated cells revealed that SOD2 was abundant in Sod2 +/+ reconstituted bone marrow. A residual amount of SOD2 was detected in the marrow of Sod2 −/− fetal liver recipients, likely derived from radio-resistant host stromal elements or a small fraction of residual host hematopoietic cells. An intermediate level of SOD2 was detected in the protein fraction from the marrow of Sod2 +/− reconstituted animals. Thus, the expression of SOD2 in bone marrow cells of transplanted animals was reflective of the number of wild-type copies of Sod2 in the transplanted cells and suggests that nearly all marrow cells are donor derived.

Figure 5.

Western blot for expression of SOD1, SOD2, and porin in RBCs and bone marrow. 50 μg of total protein lysate from RBCs or bone marrow cells of transplanted animals was separated on a 12% SDS gel and blotted for protein expression. Red cell lysates contain abundant SOD1, but do not contain detectable amounts of SOD2. The mitochondrial protein porin is present in bone marrow cells, and can be detected in the RBC lysate of Sod2 −/− transplant recipients. In a lighter exposure (*) of bone marrow–derived protein, porin is also more abundant in the sample from Sod2 −/− transplant recipients. SOD2 can be detected in the bone marrow lysates, and with a lighter exposure (**) expression levels can be correlated with the genotype of transplanted cells: Sod2+/+ lysates express the most, Sod2+/− lysates express less, and Sod2−/− lysates have <5% the level of SOD2 protein seen in Sod2+/+ samples. Results shown for porin and SOD2 expression are representative of four separate determinations.

The distribution of mitochondria in bone marrow and RBC samples was tracked through detection of the mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel (porin 31HL; reference 25). Porin was not seen in Sod2 +/+ or Sod2 +/− RBCs. Conversely, porin was detected in Sod2 −/− RBCs. Analysis of bone marrow cell proteins for porin expression shows slightly more porin in Sod2 −/− compared with control fetal liver recipients. This finding suggests that SOD2-deficient cells have increased numbers of mitochondria. Alternatively, the increased porin levels in bone marrow may reflect the increased erythroid precursor frequency we observe in Sod2 −/− fetal liver recipients. In peripheral blood, both the high reticulocyte count and increased numbers of mitochondria per cell may contribute to the porin band detected in Sod2 −/−–derived RBCs.

Sod2−/− Red Cells Possess More Oxidized Protein.

Deficiency of SOD2 has been shown to lead to both structural and functional damage to mitochondria. We reasoned that lack of SOD2 either during erythroid development or in mature RBCs might be accompanied by increased protein oxidation. We used an indirect assay for protein oxidation that measures the amount of protein carbonyl groups formed through the oxidation of amino acid side chains 26. There was a slight increase in protein oxidation of Sod2 +/− red cells compared with Sod2 +/+ red cells, which may be indicative of increased oxidative damage, although this damage is not sufficient to cause a decrease in survival of Sod2 +/− RBCs (Fig. 3). In contrast, RBC proteins from Sod2 −/− recipients demonstrated dramatically higher levels of oxidized protein compared with Sod2 +/− or Sod2 +/+ fetal liver recipients (Fig. 6), supporting the hypothesis that accelerated RBC destruction in these animals is due to increased protein oxidation.

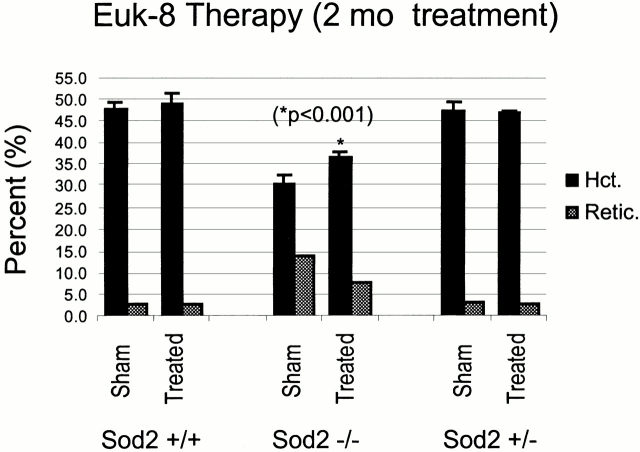

Partial Correction of Anemia Using a Synthetic SOD/Catalase Mimetic.

We reasoned that if protein oxidation is central to the pathogenesis of anemia in recipients of Sod2 −/− fetal liver cells, treatment with antioxidant compounds should ameliorate this condition. Indeed, previous work demonstrates that the antioxidant compound MnTBAP, which has SOD mimetic properties, can partially rescue the phenotype of Sod2 −/− mice 14. EUK-8, a synthetic SOD mimetic that also possesses catalase activity, was tested in our transplant model because prior studies had demonstrated the efficacy of this compound in suppression of ROS-mediated damage in vivo 27 28 and in vitro 29 30. Transplanted animals received Euk-8 or vehicle alone by intraperitoneal injection three times/week for 2 mo. Pretreatment hematocrit and reticulocyte counts were compared with samples obtained after 4 and 8 wk of treatment with EUK-8. Treatment had no effect on the hematocrit or reticulocyte count in recipients of Sod2 +/+ or Sod2 +/− fetal liver cells. After 4 wk of therapy, EUK-8–treated compared with sham-treated Sod2 −/− fetal liver recipients had an increase in their hematocrit from 30.7 to 37.8% (P = 0.01). This increase was maintained after 8 wk of therapy (30.7 vs. 36.7%; P < 0.001), and was accompanied by a corresponding decrease in the reticulocyte count from 14% pretreatment to 8% (P value not significant) after 2 mo of therapy (Fig. 7). These results demonstrate that enhanced protection from oxidative stress using a combined SOD/catalase mimetic can significantly ameliorate the anemia observed in Sod2 −/− fetal liver recipients.

Figure 7.

Partial correction of anemia using Euk-8, a synthetic SOD/catalase. Transplanted animals were divided into two groups that received either Euk-8 at a dose of 30 mg/kg 3 d/wk, or sham injections on the same schedule. Hematocrit (Hct.) and reticulocyte (Retic.) counts were determined after 8 wk of treatment. There was no effect of drug treatment on the hematocrit of animals that received Sod2 +/+ or Sod2 +/− fetal liver cells. Recipients of Sod2 −/− cells showed a significant increase in hematocrit in response to Euk-8 treatment after 8 wk (*P < 0.001) of therapy, and a corresponding decrease in reticulocyte count (P value not significant).

Discussion

Sod2− /− Fetal Liver Stem Cells Have Full Reconstituting Ability.

We studied the effect of chronic intracellular oxidative stress on immune/hematopoietic cells that lack SOD2, the enzyme responsible for detoxifying ROS generated during mitochondrial respiration. In a fetal liver transplant model, we found no obvious differences in radio protection or in long-term reconstituting ability of Sod2 −/− stem cells compared with Sod2 +/+ or Sod2 +/− cells. Further, 1 yr after transplant, there was no indication of bone marrow failure related to the lack of SOD2. To provide a more definitive answer as to whether lack of SOD2 can affect the proliferative potential of murine hematopoietic stem cells, with increasing age and/or under conditions of greater proliferative stress, the use of competitive repopulation assays and secondary transplantation are required.

Although we did not use hemoglobin electrophoretic variants or isozyme markers to quantitate donor-derived erythrocytes in our transplanted animals, several points from our data suggest that erythroid replacement was nearly complete. First, in normal hematopoietic cell reconstitution, myeloid and erythroid differentiation are closely connected, and thus it is likely that the near 100% donor-derived myeloid engraftment we observed is accompanied by a near 100% donor-derived erythroid engraftment 31. Next, when we stained bone marrow and spleen cells for the combination of CD45 and the erythroid-specific marker Ter119, we found Ter119+ nucleated cells that stain weakly (+/dim) for the donor CD45.2 marker (Fig. 1b and Fig. c). However, the analogous (host-derived) Ter119+, CD45.1+/dim population was absent, suggesting that erythroid precursors were of donor origin (Fig. 1 C). Finally, when we analyzed protein derived from bone marrow of transplanted animals for levels of SOD2, only a minimal amount of SOD2 could be detected in recipients of Sod2 −/− fetal liver cells compared with recipients of Sod2 +/+ and Sod2 +/− fetal liver (Fig. 5). Therefore, even in the absence of a donor-specific marker for mature erythrocytes, our data strongly suggest that virtually all red cells are donor derived.

Sod2−/− Stem Cells Produce Defective Erythrocytes.

Sod2 −/− fetal liver recipients were found to be persistently anemic, with erythroid hyperplasia in both the spleen and marrow as measured by the increased percentage of Ter119-positive cells. Anemia was noted as a characteristic of knockout mice of both the Sod2 tm1BCM strain 13 and the Sod2 tm1Cje strain used in this study. In analysis of the anemia, it was found that the bone marrow of Sod2 tm1BCM−/− animals was hypocellular compared with control littermates. Yet, in our transplant model, we found marked erythroid hyperplasia in the bone marrow, with normal or increased total cell numbers. This suggests that the hypocellular marrow found in Sod2 tm1BCM−/− animals is secondary to an environmental defect rather than a stem cell defect. However, when considering the erythroid lineage, defects are evident even when the metabolic environment of the host animal is normal. This clearly demonstrates an intrinsic defect in Sod2 −/− erythroid progenitors. In addition, we show that whereas Sod2 −/− progenitor cells are capable of expansion in both the spleen and marrow in response to anemia, they are only able to partially compensate for loss of red cells. Splenic erythropoiesis is increased in Sod2 −/− fetal liver recipients, but the degree of erythroid hyperplasia observed is less than that seen in other murine anemia models with a similar hematocrit. This discordance between the degree of anemia and the response may result from intrinsic differences in the response of Sod2 −/− stem cells or erythroid progenitors to homeostatic control of hematocrit through erythropoietin and other growth factors. Alternatively, the degree of erythroid hyperplasia possible in our model system may be limited due to irradiation of host tissues (specifically the spleen) before transplantation.

SOD2 deficiency anemia could be due to a defect incorporated into red cells during development that is unmasked upon exposure to oxidative stress in the circulation. The partial pressure of oxygen in the marrow (and spleen) is estimated to be quite low (24–40 mm Hg; reference 32), and therefore these environments may be relatively permissive for SOD2-deficient cells to develop with minimal oxidative damage. We speculate that most of the damage to RBCs occurs in the (arterial) circulation where the partial pressure of oxygen is the highest. In support of this conjecture, we see only a modest increase in total oxidized protein from bone marrow cells of Sod2 −/− reconstituted animals, whereas there is a dramatic increase in oxidized protein in circulating RBCs of the same animals. We have also noted that Sod2 −/− marrow and peripheral blood cells have elevated levels of the mitochondrial protein porin, indicating that these cells have a greater number or mass of mitochondria than found in Sod2 +/+ or Sod2 +/ − cells. The accumulation of abnormal mitochondria in Sod2 −/− red cell precursors and their persistence in circulating reticulocytes may be both necessary and sufficient to explain the observed increase in oxidative damage to Sod2 −/− red cells. In such a model, the mitochondria serve as the locus for ROS production, and those cells maintaining the most mitochondria for the longest period of time in the circulation sustain the most damage. Cells that successfully extrude or degrade their mitochondria rapidly would be relatively spared. This model is in accord with our observed red cell survival data, as some Sod2 −/− cells are removed prematurely whereas other cells have a normal extinction time (Fig. 3). The magnitude of the premature removal effect is most pronounced at the early time points, suggesting a limited window during which young RBCs may accumulate “fatal” oxidative damage.

We have observed two consequences secondary to accumulation of oxidized protein in SOD2-deficient cells: decreased RBC survival and altered RBC membrane deformation. Decreased RBC survival and reduced membrane deformability are common characteristics of a wide range of hemolytic processes. However, protein oxidation, as shown by the increased protein carbonyl content of SOD2-deficient cells, may be a useful marker when applied to the classification of other anemias, and may help to define those conditions most likely to respond to antioxidant therapy.

Characterization of anemia secondary to SOD2 deficiency has the potential to further our understanding of, and therapeutic approach to, a subset of human erythrocyte disorders. Interestingly, there are morphologic similarities between SOD2-deficient RBCs and red cells from patients with SA, particularly the prominence of basophilic inclusions within immature RBCs, and the increased frequency of Heinz bodies. However, there are notable differences between SOD2 deficiency in mice and human SA. In particular, the morphologic abnormalities in human SA involve red cell precursors in the marrow, and patients with SA do not have a prominent reticulocytosis. In our model of SOD2 deficiency, we observe “siderocytes” in the peripheral blood, with very few sideroblasts evident in either the marrow or the erythropoietically active spleen. Despite these differences, the pathogenesis of anemia in both the SOD2-deficient model and in human SA involves mitochondrial dysfunction.

Two types of congenital SA have been shown to involve mitochondrial pathology. In Pearson marrow pancreas syndrome, large deletions are found in mitochondrial DNA 19 33. In X-linked sideroblastic anemia with cerebellar ataxia, the human ABC7 transporter gene, which is involved in the maturation of iron-sulfur cluster-containing proteins, is mutated 18. There is also evidence that acquired SA may be caused by de novo mutations in mitochondrial DNA, specifically in subunit I of cytochrome C oxidase 34. Ultrastructural analysis of RBC precursors in SA reveals deposition of iron within mitochondria 35. Iron accumulation is proposed to occur in dysfunctional mitochondria when Fe3+ cannot be reduced to Fe2+, which is required for heme synthesis 36. A possible unifying feature between these disorders and SOD2 deficiency is an abnormality in mitochondrial iron homeostasis. Abnormal iron homeostasis in Sod2-deficient cells is suggested by the measurement of severely depressed enzymatic activity of several iron-sulfur cluster-containing proteins in mitochondria from tissues of Sod2 −/− mice 15. SA would then be a common morphologic pattern seen as a consequence of the inability of dysfunctional mitochondria (representing many different primary defects) to successfully incorporate iron into heme.

Because of the unambiguous role of increased oxidative stress as the etiologic agent of anemia due to loss of SOD2, we performed a therapeutic trial using a synthetic SOD/catalase mimetic compound. Euk-8 and related compounds have advantages over traditional free radical scavengers such as ascorbate, as they possess catalytic SOD and catalase activities, and thus are able to degrade both superoxide anions and peroxides without being consumed in the reactions 37 38. In our system, we have seen a partial, though highly significant correction of the anemia when using a single dose, route, and frequency of administration of Euk-8. Because none of these parameters has been optimized, it is likely that a more complete correction of the anemia will be possible. If catalytic antioxidant compounds such as Euk-8 prove to be useful in the treatment of human conditions like SA, they have the potential to reduce transfusion requirements and the toxicity associated with iron overloading, and would represent a welcome additional therapeutic.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elaine J. Carlson for technical support. For the materials used in this paper, EUK-8 was kindly provided for this collaboration by Eukarion Inc. (Bedford, MA).

J.S. Friedman was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant HL03748 and the Ellison Medical Foundation, C.J. Epstein by NIH grants AG16998 and AG14694, V.I. Rebel by the American Society of Hematology, S.J. Burakoff by NIH grant PO1CA39542, and F.A. Kuypers by NIH grant DK32094.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: CBC, complete blood count; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SA, sideroblastic anemia; SOD, superoxide dismutase.

References

- Weisiger R.A., Fridovich I. Mitochondrial superoxide simutase. Site of synthesis and intramitochondrial localization. J. Biol. Chem. 1973;248:4793–4796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson L.M., Jonsson J., Edlund T., Marklund S.L. Mice lacking extracellular superoxide dismutase are more sensitive to hyperoxia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:6264–6268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda Y., Honda S. The daf-2 gene network for longevity regulates oxidative stress resistance and Mn-superoxide dismutase gene expression in Caenorhabditis elegans . FASEB J. 1999;13:1385–1393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.J., Seroude L., Benzer S. Extended life-span and stress resistance in the Drosophila mutant methuselah. Science. 1998;282:943–946. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5390.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes T.L., Elia A.J., Dickinson D., Hilliker A.J., Phillips J.P., Boulianne G.L. Extension of Drosophila lifespan by overexpression of human SOD1 in motorneurons. Nat. Genet. 1998;19:171–174. doi: 10.1038/534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal R.S., Ku H.H., Agarwal S. Biochemical correlates of longevity in two closely related rodent species. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;196:7–11. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal R.S., Weindruch R. Oxidative stress, caloric restriction, and aging. Science. 1996;273:59–63. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii N., Fujii M., Hartman P.S., Tsuda M., Yasuda K., Senoo-Matsuda N., Yanase S., Ayusawa D., Suzuki K. A mutation in succinate dehydrogenase cytochrome b causes oxidative stress and ageing in nematodes. Nature. 1998;394:694–697. doi: 10.1038/29331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.W., Choi C.H., Kim M.S., Chung M.H. Oxidative status in senescence-accelerated mice. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 1996;51:B337–B345. doi: 10.1093/gerona/51a.5.b337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliaccio E., Giorgio M., Mele S., Pelicci G., Reboldi P., Pandolfi P.P., Lanfrancone L., Pelicci P.G. The p66shc adaptor protein controls oxidative stress response and life span in mammals. Nature. 1999;402:309–313. doi: 10.1038/46311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melov S., Ravenscroft J., Malik S., Gill M.S., Walker D.W., Clayton P.E., Wallace D.C., Malfroy B., Doctrow S.R., Lithgow G.J. Extension of life-span with superoxide dismutase/Catalase mimetics. Science. 2000;289:1567–1569. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Huang T.T., Carlson E.J., Melov S., Ursell P.C., Olson J.L., Noble L.J., Yoshimura M.P., Berger C., Chan P.H. Dilated cardiomyopathy and neonatal lethality in mutant mice lacking manganese superoxide dismutase. Nat. Genet. 1995;11:376–381. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebovitz R.M., Zhang H., Vogel H., Cartwright J., Jr., Dionne L., Lu N., Huang S., Matzuk M.M. Neurodegeneration, myocardial injury, and perinatal death in mitochondrial superoxide dismutase-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:9782–9787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melov S., Schneider J.A., Day B.J., Hinerfeld D., Coskun P., Mirra S.S., Crapo J.D., Wallace D.C. A novel neurological phenotype in mice lacking mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase. Nat. Genet. 1998;18:159–163. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melov S., Coskun P., Patel M., Tuinstra R., Cottrell B., Jun A.S., Zastawny T.H., Dizdaroglu M., Goodman S.I., Huang T.T. Mitochondrial disease in superoxide dismutase 2 mutant mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:846–851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M.D., Van Remmen H., Conrad C.C., Huang T.T., Epstein C.J., Richardson A. Increased oxidative damage is correlated to altered mitochondrial function in heterozygous manganese superoxide dismutase knockout mice. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:28510–28515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Remmen H., Salvador C., Yang H., Huang T.T., Epstein C.J., Richardson A. Characterization of the antioxidant status of the heterozygous manganese superoxide dismutase knockout mouse. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999;363:91–97. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allikmets R., Raskind W.H., Hutchinson A., Schueck N.D., Dean M., Koeller D.M. Mutation of a putative mitochondrial iron transporter gene (ABC7) in X-linked sideroblastic anemia and ataxia (XLSA/A) Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:743–749. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.5.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotig A., Colonna M., Bonnefont J.P., Blanche S., Fischer A., Saudubray J.M., Munnich A. Mitochondrial DNA deletion in Pearson's marrow/pancreas syndrome. Lancet. 1989;1:902–903. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92897-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T.T., Carlson E.J., Raineri I., Gillespie A.M., Kozy H., Epstein C.J. The use of transgenic and mutant mice to study oxygen free radical metabolism. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1999;893:95–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landaw S. Homeostasis, survival and red cell kineticsmeasurement and imaging of red cell production. In: Hoffman R., Benz E.J.J., Shattil S.J., Furie B., Cohen H.J., editors. Hematology, Basic Principles and Practices. Churchill Livingstone Inc; New York: 1991. pp. 274–283. [Google Scholar]

- Kuypers F.A., Scott M.D., Schott M.A., Lubin B., Chiu D.T. Use of ektacytometry to determine red cell susceptibility to oxidative stress. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1990;116:535–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann-Fezer G., Mysliwietz J., Mortlbauer W., Zeitler H.J., Eberle E., Honle U., Thierfelder S. Biotin labeling as an alternative nonradioactive approach to determination of red cell survival. Ann. Hematol. 1993;67:81–87. doi: 10.1007/BF01788131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart J., Nash G.B. Red cell deformability and haematological disorders. Blood Rev. 1990;4:141–147. doi: 10.1016/0268-960x(90)90041-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkelbach H., Walter G., Morys-Wortmann C., Paetzold G., Hesse D., Zimmermann B., Florke H., Reymann S., Stadtmuller U., Thinnes F.P. Studies on human porin. XII. Eight monoclonal mouse anti-“porin 31HL” antibodies discriminate type 1 and type 2 mammalian porin channels/VDACs in western blotting and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Biochem. Med. Metab. Biol. 1994;52:120–127. doi: 10.1006/bmmb.1994.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura A., Goto S. Analysis of protein carbonyls with 2,4-dinitrophenyl hydrazine and its antibodies by immunoblot in two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. J. Biochem. 1996;119:768–774. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez P.K., Zhuang J., Doctrow S.R., Malfroy B., Benson P.F., Menconi M.J., Fink M.P. EUK-8, a synthetic superoxide dismutase and catalase mimetic, ameliorates acute lung injury in endotoxemic swine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;275:798–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker K., Marcus C.B., Huffman K., Kruk H., Malfroy B., Doctrow S.R. Synthetic combined superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics are protective as a delayed treatment in a rat stroke modela key role for reactive oxygen species in ischemic brain injury. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;284:215–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce A.J., Malfroy B., Baudry M. beta-Amyloid toxicity in organotypic hippocampal culturesprotection by EUK-8, a synthetic catalytic free radical scavenger. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:2312–2316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez P.K., Doctrow S.R., Malfroy B., Fink M.P. Role of oxidant stress and iron delocalization in acidosis-induced intestinal epithelial hyperpermeability. Shock. 1997;8:108–114. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199708000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida N., Aguila H.L., Fleming W.H., Jerabek L., Weissman I.L. Rapid and sustained hematopoietic recovery in lethally irradiated mice transplanted with purified Thy-1.1lo Lin-Sca-1+ hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 1994;83:3758–3779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennathur-Das R., Levitt L. Augmentation of in vitro human marrow erythropoiesis under physiological oxygen tensions is mediated by monocytes and T lymphocytes. Blood. 1987;69:899–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson H.A., Lobel J.S., Kocoshis S.A., Naiman J.L., Windmiller J., Lammi A.T., Hoffman R., Marsh J.C. A new syndrome of refractory sideroblastic anemia with vacuolization of marrow precursors and exocrine pancreatic dysfunction. J. Pediatr. 1979;95:976–984. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(79)80286-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattermann N., Retzlaff S., Wang Y.L., Hofhaus G., Heinisch J., Aul C., Schneider W. Heteroplasmic point mutations of mitochondrial DNA affecting subunit I of cytochrome c oxidase in two patients with acquired idiopathic sideroblastic anemia. Blood. 1997;90:4961–4972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djaldetti M., Bessler H., Mandel E.M., Weiss S., Har-Zahav L., Fishman P. Clinical and ultrastructural observations in primary acquired sideroblastic anemia. Nouv. Rev. Fr. Hematol. 1975;15:637–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattermann N., Aul C., Schneider W. Is acquired idiopathic sideroblastic anemia (AISA) a disorder of mitochondrial DNA? Leukemia. 1993;7:2069–2076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musleh W., Bruce A., Malfroy B., Baudry M. Effects of EUK-8, a synthetic catalytic superoxide scavenger, on hypoxia- and acidosis-induced damage in hippocampal slices. Neuropharmacology. 1994;33:929–934. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianello P., Saliez A., Bufkens X., Pettinger R., Misseleyn D., Hori S., Malfroy B. EUK-134, a synthetic superoxide dismutase and catalase mimetic, protects rat kidneys from ischemia-reperfusion-induced damage. Transplantation. 1996;62:1664–1666. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199612150-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]