Abstract

Gene-targeted mice were generated with a loxP-neomycin resistance gene (neor) cassette inserted upstream of the Jλ1 region and replacement of the glycine 154 codon in the Cλ1 gene with a serine codon. This insertion dramatically increases Vλ1-Jλ1 recombination. Jλ1 germline transcription levels in pre-B cells and thymus cells are also greatly increased, apparently due to the strong housekeeping phosphoglycerine kinase (PGK) promoter driving the neo gene. In contrast, deletion of the neo gene causes a significant decrease in VJλ1 recombination to levels below those in normal mice. This reduction is due to the loxP site left on the chromosome which reduces the Jλ1 germline transcription in cis. Thus, the correlation between germline transcription and variable (V), diversity (D), and joining (J) recombination is not just an all or none phenomenon. Rather, the transcription efficiency is directly associated with the recombination efficiency. Furthermore, Jλ1 and Vλ1 germline transcription itself is not sufficient to lead to VJ recombination in T cells or early pre-B cells. The findings may suggest that in vivo: (a) locus and cell type–specific transactivators direct the immunoglobulin or T cell receptor loci, respectively, to a “recombination factory” in the nucleus, and (b) transcription complexes deliver V(D)J recombinase to the recombination signal sequences.

Keywords: PGK-neo, immunoglobulin rearrangement, loxP, transcription, B cells

Introduction

The Ig and TCR gene loci are composed of V, D, and J gene segments. During lymphocyte development, these segments somatically recombine to form a functional Ig or TCR gene. This V(D)J recombination is initiated by recombination activating gene (RAG)1/RAG2 proteins and processed by a double strand break repair complex involving DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs), Ku70/80, x-ray repair complementing defective repair in Chinese hamster cells (XRCC4), and DNA ligase IV 1 2. The recombination signal sequences (RSSs) which mediate this lymphocyte-specific recombination are highly conserved in all the antigen receptor gene segments. Given the conserved RSSs and the same recombination mechanism, the cell type– and stage-specific V(D)J recombination events must be regulated by lineage-specific (B versus T cells) and developmental stage–specific (pre- versus mature cells) accessibility mechanisms 3.

The current model for these lineage- and stage-specific accessibilities holds that the chromatin in different antigen receptor loci is opened in the appropriate cell lineage at the appropriate cell stage so that the V(D)J recombination complexes can be loaded and begin functioning 4 5.

The transcriptional enhancers in the Igκ, IgH, and TCR genes have been shown to be essential for V(D)J recombination 6 7 8 9 10 11. Antigen receptor loci generate weak germline transcripts at the time when they are recombined 3 12. For instance, germline transcripts have been observed from Ig heavy chain and κ light chain regions at the same time as their rearrangement 6 13 14 15 16. In a recent paper, the Jλ regions were shown to generate germline transcripts at the small pre-B cell stage when the Igλ genes presumably start to rearrange 17. Even though the germline transcription event is highly correlated with the V(D)J recombination, whether the germline transcription is the cause or a consequence of the chromatin opening is still in debate.

Recent studies have demonstrated that the neomycin resistance gene (neor), when inserted in the JC intron in the Ig heavy chain or κ locus, generally severely inhibits V(D)J recombination 3 9 10 18 19 20. The inhibition had been explained by postulating that the strong phosphoglycerine kinase (PGK) promoter interacts with Ig enhancer binding transactivating proteins and thus prevents V(D)J recombination either by preventing the transcription of sterile (germline) transcripts, preventing chromatin remodeling, preventing the binding of V(D)J recombinase–associated components to the Ig enhancers, or a combination of these 3. The inhibition was clearly due to the PGK-neo gene, as its removal by cre-loxP recombination reduced the inhibition. Unfortunately, the effect of PGK-neo on local germline transcription was not examined in these studies.

We have created knock-in mice in which a loxP-neor cassette was inserted upstream of the Jλ1 region. The targeted allele can be distinguished from the wild-type allele by a serine codon replacing a glycine codon normally present at position 154 of Cλ1. The wild-type Cλ1 gene can be cut by KpnI/Asp718 at this position, but the targeted allele can not. Serine is present in human and chimpanzee λ chains at this position 21. The knock-in mice showed an enormous increase in λ1 B cells which, as we report here, is due to the inserted neo gene driven by the PGK transcriptional promoter.

Materials and Methods

Targeting Vector and Embryonic Stem Clone Screening.

The original DNA construct, J3-C1 knockout, was a gift from Dr. D. Huszar, formerly of GenPharm International (San Jose, CA). In this plasmid, the region from the Jλ3 exon to part of the Cλ1 exon was replaced by a phosphoglycerate kinase promoter–driven puromycin resistance gene (PGK-puro). It was flanked by 4.2 and 4.4 kb of 129S5/SvEvBrd genomic DNA. A PGK promoter–driven thymidine kinase gene (PGK-tk) was located at the 5′ end of the DNA. To make the targeting vector, a 5.3-kb NheI fragment carrying the Jλ3 to Cλ1 region from a BALB/c genomic clone 22 was first subcloned. A NotI-XhoI fragment from the ploxPneo-1 plasmid (a gift of Dr. A. Nagy, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Canada 23) contains a neomycin phosphotransferase (neo) gene, driven by the PGK promoter, terminated by the PGK polyadenylation site, and flanked by two loxP sites. This fragment (loxP-neo) was inserted at the NdeI site, ∼100 bp upstream of the RSS of Jλ1 in such a way that the neo transcription is toward the J1C1 of the Igλ locus. Point mutations were introduced into the Cλ1 constant region, changing a glycine codon (GGT) at position 154 of the λ1 chain to a serine codon (AGC). This mutation disrupts a Kpn1/Asp718 restriction site. The 7.4-kb NheI fragment containing loxP-neo and the altered Cλ1 was then used to replace the NheI fragment containing the PGK-puro in the Jλ3-Cλ1 knockout plasmid to generate the targeting vector (see Fig. 1 A). The linearized targeting vector was electroporated into AB2.2 embryonic stem (ES) cells (purchased from Lexicon company), and G418- and gancyclovir-resistant clones were selected and further screened by Southern blotting. Two independent clones out of 360 were obtained and injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts to make chimeric mice.

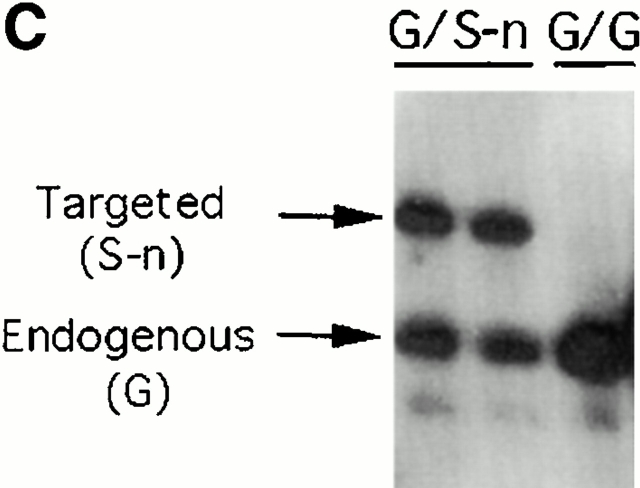

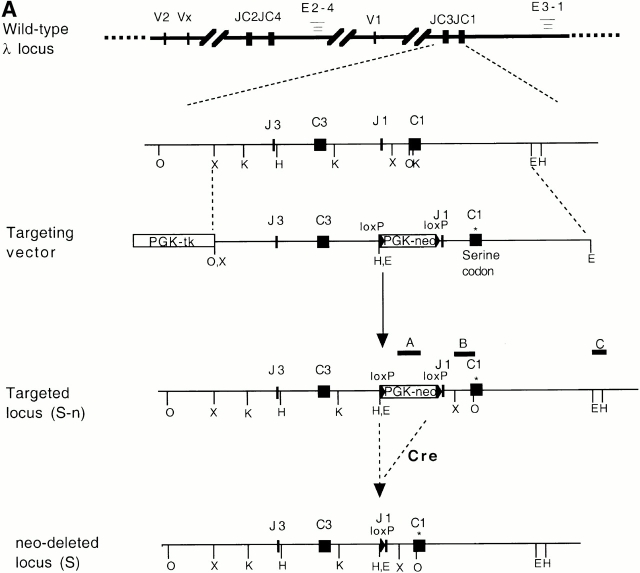

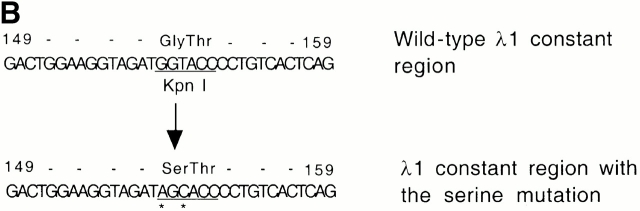

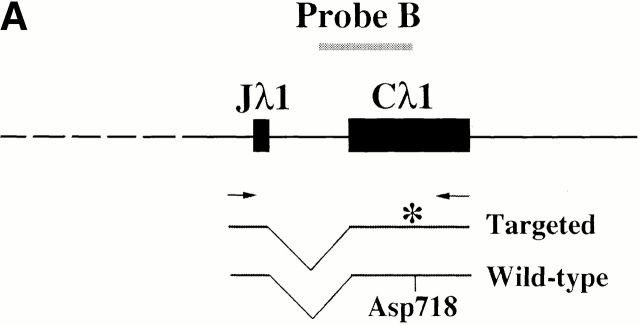

Figure 1.

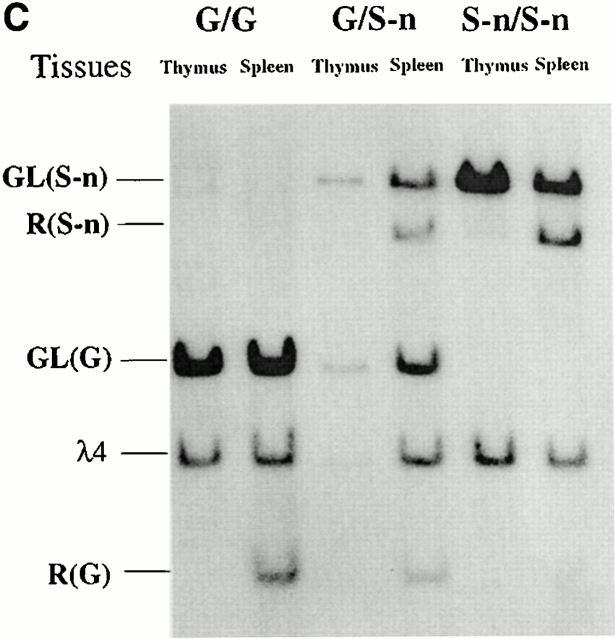

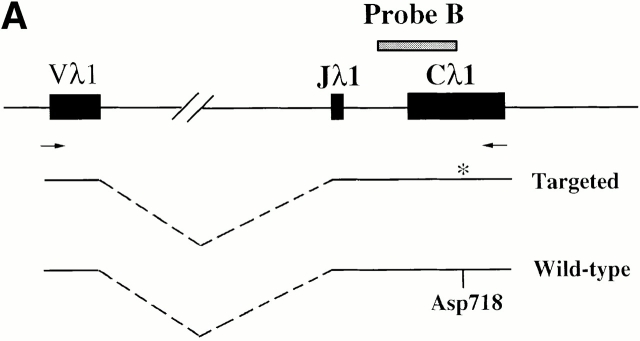

Gene targeting of the Igλ1 locus in ES cells and mice. (A) Strategy for the gene targeting. A general map of the Igλ locus is shown at the top. In the targeting vector, a PGK-neo cassette flanked by two loxP sites (shown as black triangles) was inserted ∼100 bp upstream of Jλ1 RSS region. Two point mutations (*) were introduced into the Cλ1 exon at amino acid position 154 disrupting a KpnI/Asp718 restriction site. Also indicated with black bars (A, B, or C) are probes used in this study. See Materials and Methods for other details. Cre recombinase was introduced by breeding the targeted mice with the Cre transgenic mice. The restriction sites relevant to the figures in this paper are shown as O (XhoI), X (XbaI), H (HindIII), K (KpnI/Asp718), and E (EcoRI). E2-4, and E3-1 are the λ enhancers. (B) The sequences in the Cλ1 region where the point mutations were introduced. A glycine codon (GGT) was replaced by a serine codon (AGC) at position 154. (C) Southern blot with the 3′C1 probe (A, probe C) on the HindIII-Asp718–digested ES cell DNA from two targeted cell clones (G/S-n) and wild-type cells (G/G). The targeted allele (S-n) gives a 8-kb band, whereas the wild-type allele (G) gives a 4.7-kb band. (D) Southern blot carried out with the 3′C1 probe on HindIII-Asp718–digested kidney DNA from κ−/−, λ1 wild-type (G/G), heterozygous-targeted (G/S-n), homozygous-targeted (S-n/S-n), heterozygous-targeted with neo deletion (G/S), and homozygous with neo deletion (S/S) mice. After neo deletion the targeted allele (S) gives a 5.9-kb band.

For the screening of positive ES clones, the manual from Lexicon company was followed. The ES cell DNA was digested by HindIII and Asp718 (Boehringer) and the filters were hybridized with a 3′ Cλ1 probe (see Fig. 1 A, probe C) first (see Fig. 1 C). They were then stripped and rehybridized with a neo probe (see Fig. 1 A, probe A) to confirm the homologous recombination. The DNAs from positive clones were also digested with XhoI and hybridized with a neo probe for further confirmation of correct targeting.

Mutant Mice.

Germline transmitting mice were generated by mating of chimeras with C57BL/6 mice. To generate a κ−/− background, the mice were bred with κ-knockout mice 19 24. To delete the PGK-neo gene, the κ−/−, λ1-targeted mice were bred with a cre transgenic mouse line. The EIIa-cre transgenic mice (gift from Dr. Westphal, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 25) were originally on the FVB background, which has low λ1 expression. They were bred with κ−/−, λ1 wild-type mice first to generate κ−/−, cre transgenic mice with normal λ1 expression. The mice were tested to have normal λ1 expression by serum analysis before breeding with the targeted mice and further verified by FACS® analysis of their spleen cells after the breedings (data not shown). The cre transgene was screened by PCR using primers: 5′ cre1, 5′-GGTTTCCCGCAGAACCTGAAGATG-3′ and 3′ cre1, 5′-CATTCTCCCACCGTCAGTACGTGAG-3′. The κ−/−, cre transgenic, and κ−/−, S-n/S-n mice were bred together to delete the PGK-neo gene. It took two to three breedings to completely eliminate the PGK-neo gene from the germline 25. To analyze the neo-deleted mice, mouse spleens were always bisected. Southern blot analysis of DNA from one-half of each spleen was used to check the efficiency of the PGK-neo deletion, while the other half was used to do the FACS® analysis. The results shown in this paper were all done after complete neo deletion. The mouse designations are S-n and S, for neo containing and neo deleted, respectively.

Southern Blot Analysis.

DNA isolation from mouse tissues was performed as described 24. The genotype of the κ loci was revealed by hybridizing with an EcoRI-XbaI fragment from pκRI/XbaI 19. To determine the genotypes, rearrangement, and expression levels of the λ1 locus, a 1.0-kb BglII-SmaI fragment containing the neo structural gene (neo; Fig. 1 A, probe A) from Tn5 neo, a 1.2-kb XbaI-KpnI fragment (J1XbaI-C1KpnI, probe B) in the Jλ1 to Cλ1 region and a 0.4-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment (3′ Cλ1, probe C), 4 kb downstream of the Cλ1 exon 26, were used. For quantitation of the Southern blotting signals, the filters were scanned on a PhosphorImager and analyzed by ImageQuant v1.2 software (Molecular Dynamics).

Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting.

Bone marrow and spleen tissues were disaggregated using a nylon cell strainer (Becton Dickinson). Red blood cells were then lysed by hypotonic shock. The cell debris was removed by a nylon strainer. Anti-CD16/CD32 monoclonal antibody (clone 2.4G2; BD PharMingen) was first used to block the Fcγ receptors. Cells were then stained (106 cells/staining) in the staining buffer (DMEM, free of serum, with 0.1% BSA) with the respective antibodies. Fluorescence analysis was performed on a FACScan™ (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed by CELLQuest™ software. The cells were gated for lymphocytes by forward and side scatter and a total of 10,000 events were collected for each staining. For preparative cell sorting, the stained cells were sorted using a FACStarPlus™ (Becton Dickinson). Large and small pre-B cells were sorted as B220+IgM−CD25+ distinguished by cell size (forward scatter; reference 17). Pre-B cells were sorted as B220+ and IgM− cells.

For the reverse transcription (RT)-PCR of the thymus RNA in Fig. 6, cells from an Igκ-deficient, λ1 G/S-n mouse thymus were disaggregated as described above. RNA was extracted from these freshly isolated cells. T cell content was verified by staining with anti-CD4, CD8 antibodies. Anti-CD19 antibody staining showed that there were <0.5% B cells, if any, in the thymus sample.

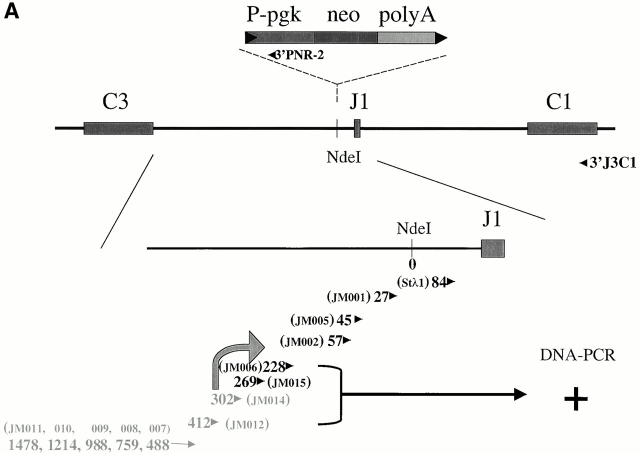

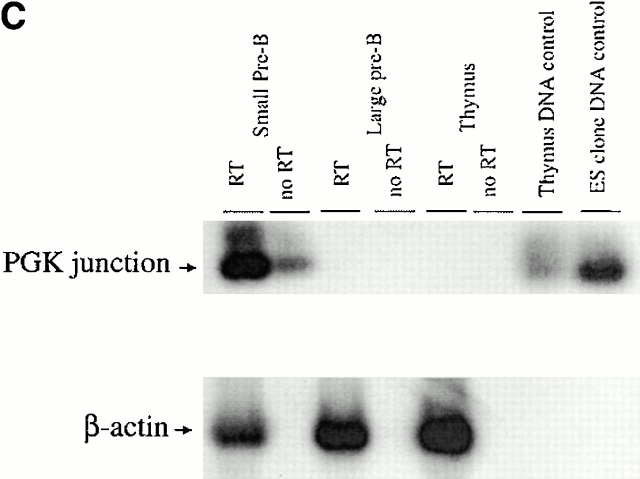

Figure 6.

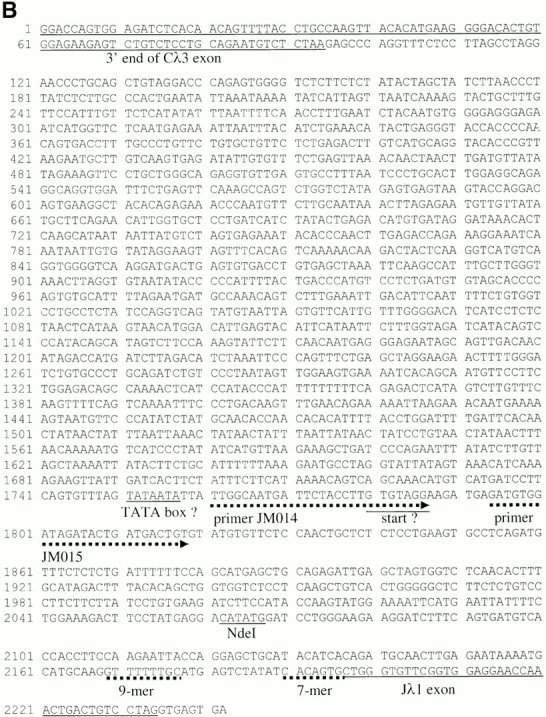

The germline Jλ1 promoter. (A) Map and RT-PCR primers used to identify the endogenous Jλ1 germline transcription initiation site. The endogenous λ1 locus is shown in the top three lanes, with the position of the NdeI site, where PGK-neo is inserted in the targeted S-n allele. The position of each upstream primer used is shown, with the number indicating the distance (in basepairs) between the 5′ end of the primer and the NdeI site. The downstream primer used for RT-PCR was 3′J3C1, located in the Cλ1 exon. The names of the primers are in brackets. The position of the potential initiation site is marked with a black arrow. DNA PCR: four primers tested and found positive in PCR amplification of genomic DNA with the 3′J3C1 downstream primer. The position of the primer used in C, 3′PNR-2, is shown. (B) Sequences 461 to 1,952 between Cλ3 and Jλ1 were not previously sequenced. Exons and nonamer/heptamer are marked by solid and dotted underlines, respectively. The primers JM014 and JM015 are indicated by dotted lines with arrows. The potential TATA box and the transcriptional start site are indicated. (C) RT-PCR to detect germline transcripts from the endogen- ous promoter in the S-n targeted allele. The primers, JM001 and 3′PNR-2 (see A), were used for PCR reactions with cDNA or RNA of the indicated cell types from a G/S-n mouse. The germline transcription products (248 bp) are indicated as “PGK junction.” G/S-n thymus DNA sample and positive ES clone DNA were included as positive PCR controls. β-actin was included as the cDNA quantity control.

The following antibodies were used for staining: Cy-Chrome–conjugated anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), FITC-labeled anti-IgM (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc.), PE-labeled anti-CD25 (PC61), PE-labeled anti-CD4, FITC-labeled anti-CD8, and FITC-labeled anti-CD19 (all from BD PharMingen, unless described otherwise). λ1 B cells were revealed by biotinylated L22.18.2 monoclonal antibodies 24 27 with PE-labeled streptavidin (BD PharMingen) as the secondary reagent. λ2 and λ3 B cells were revealed by FITC-labeled anti-λ2/3 antibody (2B6; references 17 and 28).

RNA Preparation.

Freshly harvested cells were homogenized in 1 ml of STAT-60 containing phenol and guanidinium thiocyanate (Tel-Test). The RNA was extracted, precipitated, and resuspended in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water.

PCR, RT-PCR, and Sequence Analysis.

The sequences of the primers used for these assays are: 5′Nreg, 5′-CGCGAATTCTCAGGCTCCCTGATTGGAGACAAGG-3′; 3′Nreg, 5′-GCGGCAAGCTTTCCCAGCCTCTGTGCTGAATGTTC- TG-3′; Stλ1, 5′-CTTGAGAATAAAATGCATGCAAGG-3′; 3′J3C1, 5′-GACCTAGGAACAGTCAGCACGGG-3′; JM001, 5′-TTTTCTGGAAAGACTTCCTATGAGG-3′; JM005, 5′-TGGAAAATTCATGAATTATTTTCTG-3′; JM002, 5′-CC- ATACCAAGTATGGAAAATTCATG-3′; JM006, 5′-TGC- TCTCTCCTGAAGTGCCTCAGATG-3′; JM015, 5′-GATGTGGATAGATACTGATGACTGTG-3′; JM014, 5′-TTGGCAATGATTCTACCTTGTGTAGG-3′; JM012, 5′-GAATGCCTAGGTATTATAGTAAACATC-3′; JM007, 5′-CCCTATATCATGTTAAGAAAGCTGATCCC-3′; JM008, 5′-CACAGCAATGTTCCTTCTGGAGACAGCC-3′; JM009, 5′-CCTCTCTAACTCATAAGTAACATGGAC-3′; JM010, 5′-CAAGGATGACTGAGTGTGACCTGTGAGC-3′; JM011, 5′-GAGTAAGTACCAGGACAGTGAAGGC-3′; VL1L, 5′-gtttgtgaattatggcctggat-3′; VL1RSS, 5′-GATGTAGCCACCTGTTAAGAAAG-3′; VL1Lin, 5′-TACTCTCT- CTCCTGGCTCTCAGCTC-3′; 3′PNR-2, 5′- CCGTCGACGACCTGCAACCAAGCTA-3′; 5′β-actin, 5′-GTGGGCCGCTCTAGGCACCAA-3′; and 3′β-actin, 5′-CTCTTTGA-TGTCACGCACGATTTC-3′.

The positions of PCR and RT-PCR primers in the λ locus are indicated in Fig. 5 A, 6 A, and 7 A. To distinguish the rearrangements in splenic and sorted λ B cells in various mice, PCR with the primers 5′Nreg and 3′J3C1 were used. The cycling conditions for the reactions were optimized to assure linear amplification. PCR conditions were as follows: 94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min, with 28–35 cycle times. To clone and sequence the VJ junction in S-n/S-n splenic DNA and sorted G/S λ B cell DNA, primer sets 5′Nreg/3′Nreg and 5′Nreg/3′J3C1 were used, respectively. The PCR products were cloned into the pCR-BluntII-TOPO vector and sequenced according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). In the RT reactions, the first strand cDNA was generated by using an oligo-dT primer. To obtain RT-PCR products of germline transcripts of the Jλ locus, primers Stλ1 17 and 3′J3C1 were used in the following PCR condition: 94°C for 20 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 20 s, cycled 30–35 times. All reactions were done in two dilutions. In comparing the transcripts from the targeted and the wild-type alleles, heterozygous mice were used and primers chosen so that the two products only differ by two internal nucleotides. The allele-specific cDNAs were distinguished by subsequent restriction cutting of the wild-type product; it is thus unlikely that the PCR reaction was skewed for one or the other cDNA.

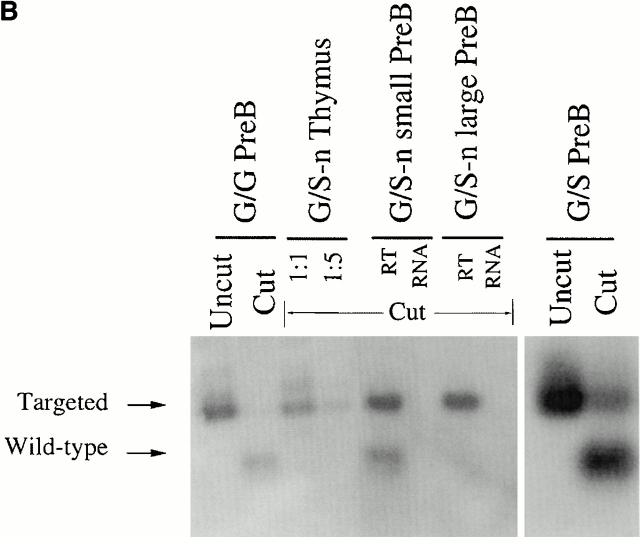

Figure 5.

Germline transcription levels of Jλ1 in κ−/− G/S-n and G/S mice. (A) Schematic structure of the Jλ1 germline transcripts. The germline transcripts are initiated 5′ of the J region and spliced to the C region. Location of primers used for RT-PCR are shown by small arrows. The gray box indicates the probe (see Fig. 1 A, probe B) used in the Southern blot in Fig. 6 B. The PCR product of the wild-type allele contains a KpnI/Asp718 site whereas that of the targeted allele does not. (B) Southern blot of the RT-PCR products of the germline transcripts from the indicated cell stage/lineage. The RT-PCR products were digested by Asp718 (indicated as “Cut”) to distinguish products from the wild-type and targeted alleles. The blots were hybridized with the J1XbaI-C1KpnI probe. Germline transcripts corresponding to the targeted or the wild-type alleles are indicated. The experiments from two dilutions of thymus sample are shown. No amplification products were obtained when reverse transcriptase was omitted from the reaction of all the samples (two are shown as “RNA,” others not shown).

To determine the position of the germline promoter of the Jλ1 region in the wild-type allele, a series of endogenous primers upstream of the Jλ1 exon (JM000s) were used (see Fig. 6 A). They were paired with the 3′J3C1 primer for RT-PCR with pre-B cell RNA from a Igκ knock-out λ1 wild-type mouse. RT-PCR condition: 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min, 30 s, 35 cycles. The efficiencies of these primers were tested in PCR reactions using the same condition with kidney DNA from a wild-type mouse.

To determine transcription from the Jλ1 germline promoter in the targeted allele, RT-PCR was performed with the primers JM001 and 3′PNR-2 (see Fig. 6 A). RT-PCR condition: 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, 35 cycles. The β-actin RT-PCR was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.) with 5′β-actin and 3′β-actin primers.

For all the Asp718 digestions of PCR and RT-PCR products, the G/G samples were always used as the efficient digestion control. Normally, 8 μl PCR product were digested with Asp718 at 37°C overnight. To increase the sensitivity of the assay, after the electrophoresis, the samples were transferred onto a nylon filter and hybridized with the specific radiolabeled probes (see Fig. 1 A).

Results

Targeted Insertion of PGK-Neo Upstream of the Jλ1 Region.

We generated mutant AB2.2 ES cells in which the loxP-flanked PGK-neo cassette was inserted 100 bp upstream of the Jλ1 RSS region (Fig. 1a Fig. b Fig. c). The PGK-neo was inserted in the same transcriptional orientation as the JCλ1 region. Two point mutations were introduced at amino acid position 154 of the Cλ1 gene, changing a glycine codon into a serine codon. The mutations disrupt a KpnI/Asp718 restriction site so that the targeted allele and the wild-type allele can be easily distinguished. Mutant ES cells were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts to create targeted mice containing the serine codon and neo (Fig. 1 D). Germline transmitting mutant mice were further crossed with Igκ knockout mice 19 to result in a homozygous κ-knockout background. In this way only λ light chains were produced, facilitating their analysis, as normally λ+ B cells represent only 5% of the total B cells. The work described here was done with mice with a κ knockout background unless described otherwise. To eliminate PGK-neo by Cre/loxP recombination, EIIa-cre transgenic mice 25 were bred with the serine-targeted mice to generate PGK-neo deleted mice (Fig. 1 D; S/S). The neo targeted allele is named S-n (serine-neo), and after neo deletion it is named S. The wild-type allele is named G (glycine).

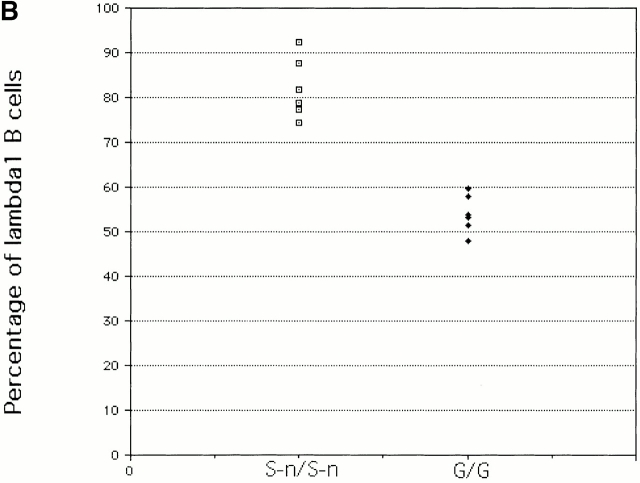

Gene-targeted Mice Have Greatly Increased λ1 B Cell Numbers.

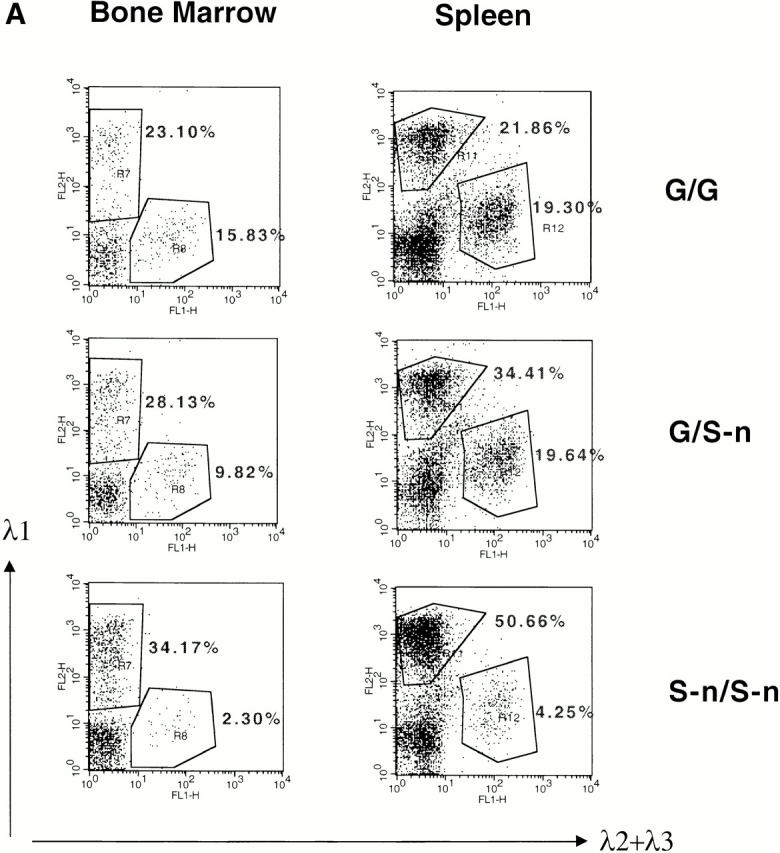

Bone marrow and splenic B cells from κ−/− and λ1 wild-type (G/G), heterozygous (G/S-n), or homozygous (S-n/S-n) mice were analyzed by FACS®. Surprisingly, compared with wild-type mice, the λ1 B cell numbers in the G/S-n heterozygous mice are greatly increased both in bone marrow and spleen (Fig. 2 A). The homozygous S-n/S-n mice have an even greater enhancement (Fig. 2 A). Although in wild-type mice the ratio of λ1 to λ2/3 B cells in the bone marrow and spleen is 1.5 and 1.1, respectively, the ratio in homozygous knock-in mice, λ1 S-n/S-n, is 14.9 and 11.9. Six independent pairs of mice were analyzed by FACS®; the λ1 B cell percentages in S-n/S-n mice increase dramatically in all cases (Fig. 2 B). On average, the λ1 wild-type G/G mice have 54% λ1 B cells, but the mutant S-n/S-n mice have 82%. We also checked the pro-, pre-B cell stages and no difference was found between S-n/ S-n and G/G (data not shown).

Figure 2.

λ1 B cells in bone marrow and spleen of mice with the Neo insertion. (A) Bone marrow and spleen cells from κ−/− G/G, G/S-n, and S-n/S-n mice were double-stained with FITC-conjugated anti-λ2+λ3 antibody and biotin-coupled anti-λ1 antibody (revealed by PE-coupled streptavidin) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Lymphoid cells were gated by forward and side scatter. The numbers indicate the percentages of the particular cell population among all the gated lymphoid cells. (B) The percentages of λ1 B cells among the total splenic B cells in the κ−/− G/G vs. S-n/S-n mice. The results from six independent FACS® analyses are shown. Three littermates as well as three nonlittermates are included. (C) Southern blot with the J1XbaI-C1KpnI probe (see Fig. 1 A, probe B) on EcoRI-Asp718–digested thymus and spleen DNA from κ−/− G/G, G/S-n, and S-n/S-n mice. The germline bands are indicated as “GL” and the rearranged bands are indicated as “R.” The targeted allele and nontargeted allele are indicated as “S-n” and “G”, respectively. The probe cross-reacts with a germline band from the pseudogene JCλ4 and therefore the λ4 band was used as the loading control of the experiment.

In κ wild-type mice with the S-n/S-n λ1 locus (Table ), the κ B cell number seems to be downregulated at the same time as the λ B cell number increases, altering the κ/λ ratio from 20:1 to 8:1. The total lymphocyte number seems also decreased, which may be caused by the less efficient development of λ B cells than κ B cells due to selection. Indeed, in κ knockout mice with wild-type λ locus, where all B cells are λ producing, the total B cell number decreases to ∼50% of normal 29.

Table 1.

λ B Cell Numbers in κ Wild-type Mice

| Genotype | N | Total nucleated cells | Total lymphocytes | κ B cell numbers | λ B cell numbers | N′ | Percentage of κ B cell | Percentage of λ B cell |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G/G | 4 | 80 ± 15.5 | 59.20 ± 16.10 | 37.75 ± 13.85 | 1.86 ± 0.43 | 6 | 63.01 ± 8.41 | 3.38 ± 0.59 |

| G/S-n | − | − | − | − | − | 3 | 53.70 ± 6.86 | 5.30 ± 0.44 |

| S-n/S-n | 4 | 70.5 ± 18.41 | 50.48 ± 18.33 | 22.76 ± 4.27 | 3.45 ± 1.38 | 5 | 50.98 ± 13.59 | 6.55 ± 1.24 |

The splenic cell numbers were determined in G/G, G/S-n, and S-n/S-n mice on the κ wild-type background. “N” stands for the total number of mice in which the total spleen cell numbers were counted. “N′” stands for the total number of mice analyzed, including some in which the total nucleated cell numbers were not determined; thus, N′ is greater than N. The unit of the cell number is 106. The average numbers are followed by the SEM. Total lymphocyte numbers were calculated by forward and side scatter gating in FACS® analysis. κ and λ B cells are determined by double-color fluorescence staining using polyclonal antibodies. The percentages of κ and λ B cells are per total lymphocytes.

High Levels of VJ Recombination in the Targeted Allele.

We next examined whether rearrangement is increased in the targeted allele. As the serine mutation disrupts a KpnI/Asp718 restriction site, the rearranged targeted allele can be distinguished from the wild-type allele by EcoRI and Asp718 double digestion (Fig. 2 C). In the spleen of the λ1 heterozygous G/S-n mouse, there is a twofold stronger rearranged band from the targeted allele than from the wild-type allele. This finding was made in repeated analyses. This effect is further confirmed by semiquantitative PCR of the splenic DNA from a heterozygous mouse (see Fig. 5 B, G/S-n). The PCR analysis shows a much greater difference between the wild-type and targeted band than the Southern blot (∼5×); presumably in the latter, the large band size difference gives a less accurate comparison. The two serine point mutations in the targeted allele are 200 bp away from the downstream PCR primer and are unlikely to have any effect on the PCR reaction. Thus, the high λ1 expression in these B cells is due to the targeted allele in cis. It could be either caused by the PGK-neo insertion or by the serine knock-in mutation in that allele.

As expected, no rearrangement of either the wild-type or the targeted λ1 allele is seen in thymus (Fig. 2 C).

The PGK-Neo Cassette Is the Cause of the Higher VJ Recombination in the Targeted λ1 Locus.

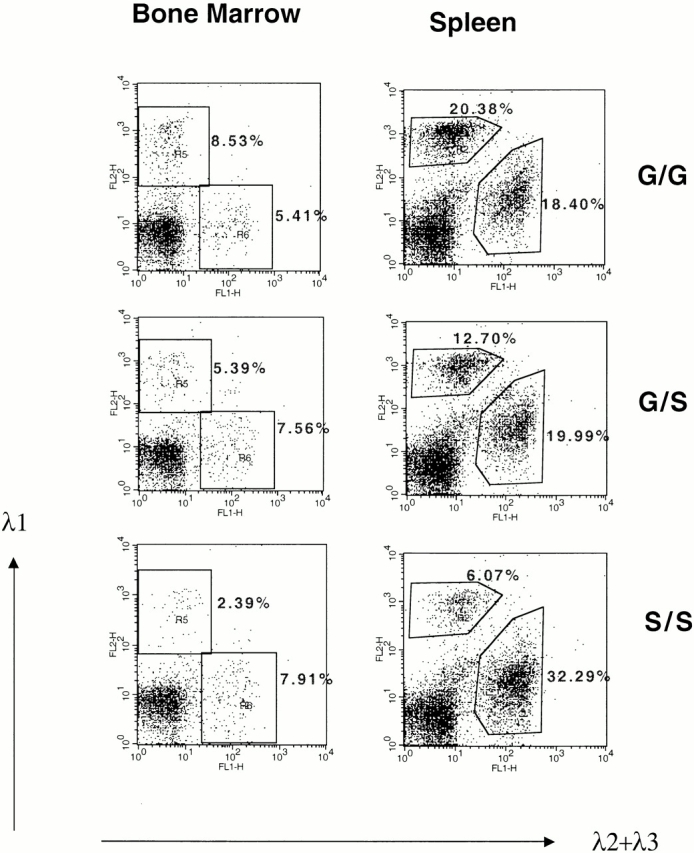

The serine codon mutation, consisting of two single nucleotide changes, is 1.3 kb away from the Jλ1 RSS making it unlikely that it affects VJ recombination. However, the serine codon could affect λ1 B cell receptor activity and therefore λ1 B cell development. On the other hand, PGK-neo, which is located between the Vλ1 and Jλ1 region, could only affect VJ recombination and not λ1 transcription, as PGK-neo will be deleted by VJ recombination. To determine if the PGK-neo leads to the high λ1 expression, the loxP-flanked neo gene was deleted from the germline of targeted mice by breeding with cre transgenic mice (see Materials and Methods). This cre transgene is expressed throughout life in all cells, starting in the early embryo 25. After 2–3 breedings with the cre transgenic mice, the targeted mice had completely lost the PGK-neo cassette from the germline. Southern blotting of the splenic DNA (similar to Fig. 1 D, data not shown) demonstrates that the 8-kb band (S-n, with neo insertion) is replaced by a 5.9-kb band (S, without neo). Flow cytometric analysis of the splenocytes from the cre transgenic offspring shows that the percentage of λ1 B cells is reduced from 63.6% (34.41% λ1/54.05% total B) to 38.8% in G/S versus G/S-n mice and from 92.2 to 15.8% in S/S versus S-n/S-n mice (compare Fig. 3 and Fig. 2 A). Therefore, the PGK-neo gene in the targeted allele greatly increases VJ recombination at that allele. We also note that the percentage of λ1 B cells is reduced after the PGK-neo deletion (S/S) to even lower levels than in wild-type mice (G/G; Fig. 3; see below).

Figure 3.

λ1 B cells in bone marrow and spleen after neo deletion. The analysis was done as in the legend to Fig. 2 A. A representative analysis from κ−/− G/G, G/S, and S/S mice is shown. Spleens were bisected. One half was used to do a Southern blot (similar to Fig. 1 D; data not shown) confirmed that neo was completely deleted. The other half was used for the FACS® analysis.

To check whether the PGK-neo can advance VJ recombination into an earlier B cell stage, we sequenced the Vλ1Jλ1 coding joints from splenic B cells of the S-n/S-n targeted mice (Table ). N region nucleotide addition was found in only 1 of 14 joints, similar to the light chain N addition frequency in λ1 genes of normal mice. The VD and DJ joints of IgH chain genes, which rearrange at the pro-B to early pre-B cell stages, have a high frequency of N additions due to TdT expression 30. Thus, using N additions as a measure of B cell stage, we conclude that PGK-neo cannot drive VJ recombination of λ1 to the early B cell stages at which IgH genes rearrange. As expected from a random sample, only about 1/3 of the rearrangements were in frame (productive; Table ).

Table 2.

VJ Joints of λ1 Light Chain Genes

| Vλ1 region | N region | Jλ1 region | Productivity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGC AAC CAT TTC | C TGG GTG TTC | |||

| 1 | AGC AAC CAT TT– | – ––G GTG TTC | + | |

| 2 | AGC AAC CAT TT– | – –GG GTG TTC | − | |

| 3 | AGC AAC CA– ––– | C TGG GTG TTC | + | |

| 4 | AGC AAC CAT TTC | T | – ––– GTG TTC | − |

| 5 | AGC AAC CAT TT– | – –GG GTG TTC | − | |

| 6 | AGC AAC CAT T–– | – –GG GTG TTC | + | |

| 7 | AGC AAC CAT T–– | – –GG GTG TTC | + | |

| 8 | AGC AAC CAT TT– | – –GG GTG TTC | − | |

| 9 | AGC AAC CAT TT– | – –GG GTG TTC | − | |

| 10 | AGC AAC CAT TTC | – –GG GTG TTC | − | |

| 11 | AGC AAC CAT TTC | – –GG GTG TTC | − | |

| 12 | AGC AAC CAT TT– | – TGG GTG TTC | − | |

| 13 | AGC AAC CAT TT– | – –GG GTG TTC | − | |

| 14 | AGC AAC CAT TT– | – –GG GTG TTC | − |

VJ joints of λ1 light chain genes from the splenic DNA of a κ−/− S-n/S-n mouse. The germline coding end sequences adjacent to the RSSs in the Vλ1 and Jλ1 regions are shown underlined on the top. Each line represents an individual clone. Nucleotides deleted at the coding ends are indicated by dashes. N nucleotides are shown as an underlined italic letter in the middle column. Productivity: the joint results in an in-frame (+) or out-of-frame (−) J region.

The LoxP Site Inhibits VJ Recombination in the Targeted λ1 Locus.

The targeted mice with a complete PGK-neo deletion (S/S) have a lower level of λ1 B cells than the wild-type mice: the S/S mice have only 15.8% λ1 B cells (6.07/38.36% of total B cells) compared with 52.5% λ1 B cells (20.38/38.78%) in the G/G wild-type mice (Fig. 3). This effect is unlikely to be caused by mouse strain polymorphisms, as the mice were bred with κ−/− mice, basically on a C57BL/6 background. Also, among the strains we used, 129 and C57BL/6, the λ1 expression is always close to 55–60% of the total λ B cells 31. However, the decreased λ1 expression from the targeted allele could be caused by the serine codon mutation or by the loxP site left on the chromosome. If serine at position 154 of the Cλ1 region decreases the signaling efficiency of the λ1 B cell receptor, B cell development could be affected, which in turn could reduce the mature λ1 B cell numbers. However, based on the comparison of the percentages of immature λ1 B cells (mainly in the bone marrow) with mature B cells (spleen), the serine substitution does not inhibit the development from the immature to the mature B cell stage. The ratio of λ1/λ2+λ3 in spleen is 75% of that in bone marrow in the G/G mice, and 70% in the S/S mice (Fig. 3, and data not shown). Thus, the S/S λ1 B cells survive as well as the G/G B cells during B cell maturation from the bone marrow to the spleen stage.

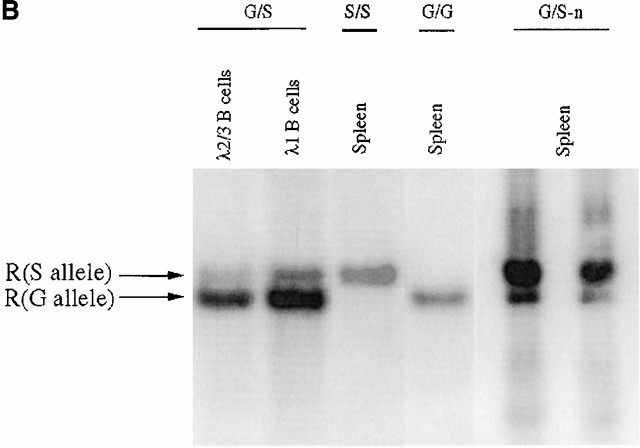

To directly test whether the λ1 deficiency after elimination of PGK-neo was caused by inefficient VJ recombination, we purified λ1 and λ2/λ3 B cells separately from a heterozygous mouse (G/S) spleen by cell sorting. Semiquantitative PCR was employed to amplify the rearranged λ1 genes from each DNA sample (Fig. 4 A). After Asp718 digestion, the wild-type versus targeted rearranged bands can be distinguished (Fig. 4a and Fig. b). The rearranged wild-type λ1 band is four times stronger than the targeted λ1 band in λ2/λ3 B cells, and there is a similar difference in λ1 B cells (Fig. 4 B). We next sequenced the λ1 VJ sequences from λ2/λ3 B cells. All of the sequences (18/18) are nonproductively rearranged (the majority are from the wild-type allele), whereas the sequences from λ1 B cells are all functional (7/7; Table ). The absence of productive λ1 rearrangements in λ2/3 cells has also been found in normal mice 32. It probably indicates that in general, λ1 is rearranged before λ2 or λ3, thus allowing λ2/3 rearrangement mainly if λ1 is nonproductively rearranged. On the other hand, the finding that all seven out of seven λ1 sequences obtained from λ1 B cells of G/S mice were from the wild-type, G, allele further indicates that the wild-type allele is rearranged much more efficiently than the mutant S allele. Also, if the wild-type λ1 allele is nonproductively rearranged, the cell then apparently has a greater chance to rearrange λ2/3 than to rearrange the targeted λ1 gene (S) allele (see also Fig. 3G/S and S/S). The nonproductive λ1 in λ2/3 B cells could not have been selected on the protein level and could thus not be affected by the serine mutation. The levels of the rearranged bands (Fig. 4 B) thus directly reflect the VJ recombination efficiency of the corresponding alleles. Therefore, after removal of PGK-neo, the targeted allele does have reduced λ1 VJ recombination, which could only be caused by the loxP site left on the chromosome.

Figure 4.

VJ rearrangement in the targeted allele without neo. (A) Schematic structure of the λ1 genomic locus and its rearranged DNA product. Location of primers used for PCR are shown by small arrows. The gray box indicates the probe (see Fig. 1 A, probe B) used in the Southern blot in B. The PCR product of the rearranged wild-type allele contains a KpnI/Asp718 site whereas that of the targeted allele does not. (B) Southern blot with the J1XbaI-C1KpnI probe (see Fig. 1 A, probe B) on the rearranged VJλ1 PCR products from DNA of either sorted splenic B cells or total spleen. λ1 and λ2+λ3 B cells were sorted separately from a κ−/− G/S mouse spleen. The spleen DNAs from κ−/− G/G, S/S, and G/S-n mice were included as controls. All the PCR products were digested by Asp718 and the sample from κ−/− G/G was used as the complete digestion control. “R” stands for “rearranged.” The bands were quantitated and gave the following ratios: in G/S mice, the S/G ratio in λ2/3 B cells was 1:4, and in λ1 B cells it was 1:3.8. In G/S-n mice, the S-n/G proportion in total spleen was 5:1. For G/S-n mice either 35, left lane, or 30, right lane, PCR cycles were used. The higher MW bands in spleen are undefined PCR artifacts.

Table 3.

Sequence Analysis of the Rearranged λ1 Gene

| Germline sequences | Productivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vλ1-AAC CAT TTC | ||||

| From λ2/3 B cells | ||||

| 1 | AAC CAT ––– | – –GG GTG TTC GGT | − | |

| 2 | AAC CAT ––– | C TGG GTG TTC GGT | − | |

| 3 | AAC CAT ––– | AG | C TGG GTG TTC GGT | − |

| 4 | AAC CAT TT– | – TGG GTG TTC GGT | − | |

| 5 | AAC CAT TT– | G | – –GG GTG TTC GGT | − |

| 6 | AAC CAT ––– | C TGG GTG TTC GGT | − | |

| 7 | AAC CAT TT– | – –GGGTG TTC GGT | − | |

| 8 | AAC CAT ––– | – –GGGTG TTC GGT | − | |

| 9 | AAC CAT TTC | – –GGGTG TTC GGT | − | |

| 10 | AAC CAT TT– | – –GGGTG TTC GGT | − | |

| 11 | AAC CAT ––– | C TGG GTG TTC GGT | − | |

| 12 | AAC CAT TTC | GAA | – ––G GTG TTC GGT | − |

| 13 | AAC CAT TTC | – ––G GTG TTC GGT | − | |

| 14 | AAC CAT TT– | – –GG GTG TTC GGT | − | |

| 15 | AAC CAT TT– | – –GG GTG TTC GGT | − | |

| 16 | AAC CAT ––– | G | C TGG GTG TTC GGT | − |

| 17 | AAC CAT ––– | – –GG GTG TTC GGT | − | |

| 18 | AAC CAT TT– | – –GG GTG TTC GGT | − | |

| From λ1 B cells | ||||

| 1 | AAC CAT T–– | – –GG GTG TTC GGT | + | |

| 2 | AAC CAT ––– | – TGG GTG TTC GGT | + | |

| 3 | AAC CAT TT– | – ––G GTG TTC GGT | + | |

| 4 | AAC CAT T–– | – –GG GTG TTC GGT | + | |

| 5 | AAC CAT T–– | – –GG GTG TTC GGT | + | |

| 6 | AAC CAT T–– | – –GG GTG TTC GGT | + | |

| 7 | AAC CAT T–– | – –GG GTG TTC GGT | + |

Sequence analysis of the rearranged λ1 gene in either sorted λ1 or sorted λ2+λ3 B cells from a κ−/− G/S mouse. The germline sequences of Vλ1 and Jλ1 coding ends are shown at the top. Independent clones from the sorted B cells are shown below. Nucleotides deleted at the coding ends are indicated by dashes. P (palindromic) elements are shown in italics. N nucleotides are shown as underlined italics. Productivity: + (−), the gene is productively (nonproductively) rearranged.

The Levels of Jλ1 Germline Transcripts Are Correlated with the Efficiency of VJ Recombination in S-n, S, and G Alleles.

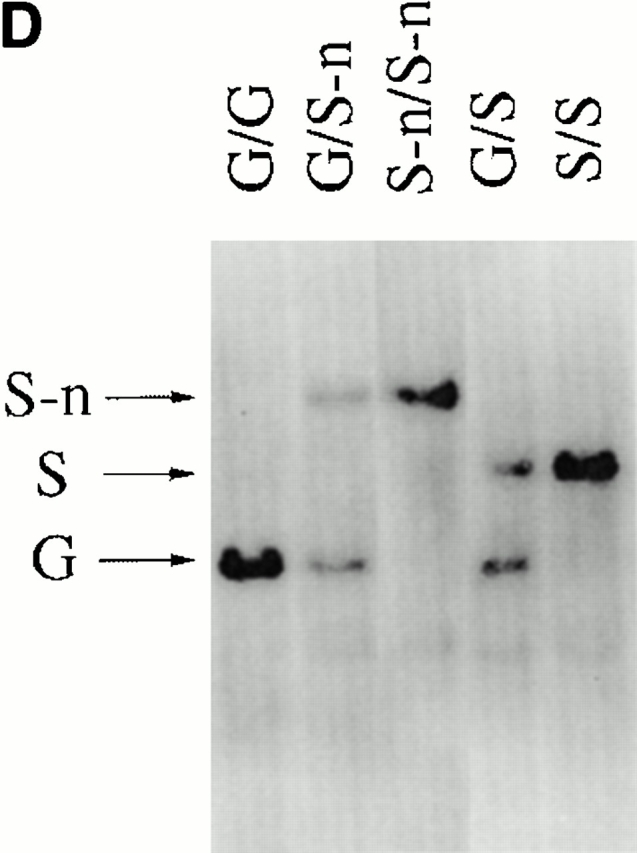

To determine the relationship between VJ recombination efficiencies and germline transcription activity, we measured the levels of Jλ1 germline transcripts in heterozygous mice before and after deletion of PGK-neo and in the wild-type λ1 locus. The Igλ light chain genes normally start to rearrange at the small pre-B cell stage, at which time Jλ germline transcription is found 17. We sorted small pre-B (IgM−B220+CD25+, small) as well as large (less mature) pre-B cells (IgM−B220+CD25+, large) from the bone marrow of two G/S-n heterozygous mice. RT-PCR and restriction digestion were performed to distinguish the germline transcript levels from the two different alleles (Fig. 5). At the small pre-B cell stage, the level of germline transcripts is 1.6 to 5.9 times higher from the targeted allele (S-n) than from the wild-type allele (G). A much greater difference is observed in less mature large pre-B cells. Transcripts from the targeted allele are present at similar levels as in small pre-B cells by semiquantitative estimation relative to β-actin, but no transcripts from the wild-type allele can be found. The absence of germline λ1 transcripts in large pre-B cells of wild-type mice has also been observed by Engel et al. in normal mice 17. In addition, T cells also show high Jλ1 transcription from the targeted allele (Fig. 5 B). The high transcript level from the targeted allele is most likely due to the ubiquitously active strong PGK promoter. However, transcription alone is not sufficient for VJλ1 rearrangement in large pre-B cells (Table ) and T cells (Fig. 2 C; see Discussion).

To compare the expression of the wild-type and targeted alleles after neo deletion we sorted pre-B cells (IgM− B220+) from the heterozygous G/S mouse bone marrow. The germline transcripts from these cells are clearly biased to the wild-type allele (Fig. 5 B). Coincidentally, in these mice, VJ recombination also preferably occurs at the wild-type allele (Fig. 4). Thus, the germline transcript levels exactly parallel the recombination efficiencies from the highest in PGK-neo containing (S-n), through the intermediate in wild-type (G), to the lowest in PGK-neo deleted (S) λ1 alleles.

Mapping of the Germline Jλ1 Promoter.

To understand the relationship between the inserted PGK-neo gene and the germline Jλ1 promoter we determined the position of this promoter. Jλ1 germline transcription was found previously in wild-type mice, but the transcript initiation site was not defined in mice 17. To map the promoter, a series of 13 5′ primers were used that are located 5′ of Jλ1, together with a 3′ primer in Cλ1 to amplify oligo-dT-primed cDNAs from pre-B cells of λ wild-type mice. As shown in Fig. 6 A, primers located up to 269 nucleotides upstream of the NdeI site gave a PCR product, whereas primers located further upstream did not. The most 3′ two of the latter primers were found to amplify a correct sized and sequenced product from genomic DNA; therefore, the lack of cDNAs extending into this region is not due to inefficient primers. Thus, this analysis places the initiation of the germline Jλ1 transcript between primers JM014 and JM015. There is a good candidate for a TATA box just upstream of primer JM014 which would place the transcription start site at about the G located 29 nucleotides 3′ of the putative TATA box (Fig. 6 B). This start site is six nucleotides 5′ of the 3′ end of primer JM014, making the primer overlap too short for stable annealing. Thus, the start of the Jλ1 germline transcript is located 420 nucleotides 5′ of Jλ1 in the untargeted λ locus (Fig. 6 B). In the targeted locus it resides 336 nucleotides 5′ of the inserted PGK-neo gene and 1 kb 5′ of the start of the neo gene transcripts.

Do All Jλ1 Germline Transcripts from the Targeted Allele Initiate from the PGK Promoter?

Jλ1-containing transcripts in thymus and large pre-B cells of G/S-n mice are all from the targeted allele (Fig. 5 B). These transcripts must initiate from the PGK promoter, as none are found that initiate upstream of this promoter in the targeted allele of G/S-n mice (Fig. 6 C). On the other hand, in small pre-B cells, Jλ1-containing transcripts arise from both the targeted and the wild-type allele in G/S-n mice (Fig. 5 B). Interestingly, in these cells transcripts are found that start upstream of the PGK promoter and most likely initiate at the germline Jλ1 promoter. Thus, this promoter is only active in small pre-B cells when the λ enhancers are activated and VJ recombination takes place, even in the presence of PGK-neo.

Discussion

Jλ1 Germline Transcription and VJ Recombination Is Promoted by the PGK-Neo Insertion.

When PGK-neo is inserted in the κ or heavy chain intron, in most cases it causes strong inhibition of V(D)J recombination 3 9 10 18 19 20. A similar phenotype has also been observed in the TCR loci 33. This was postulated to be due to the higher density of CpGs in the coding sequence of the neo gene 18 or to the neo coding region itself 34. Alternatively, it may be due to a squelching effect, in which the PGK promoter interacts with the Ig enhancer at the expense of an Ig promoter/enhancer interaction 9 10. In our experiment, the location of the PGK promoter relative to the germline Jλ1 promoter and the Eλ3-1 enhancer is such that the PGK promoter initiates transcripts that pass through the RSS. Therefore, instead of possibly interfering with the germline transcription of the JC λ1 region, a strong PGK promoter in this case promotes transcription through Jλ1. However, similar to findings by others 35 transcription alone is not sufficient for rearrangement (see below).

The Jλ1 Germline Transcription Is Inhibited by the LoxP Site.

A single remnant loxP site with its short flanking region dramatically inhibits VJ recombination. This is probably a consequence of the severe inhibition of Jλ1 germline transcription by this loxP remnant (Fig. 5). We consider two possible reasons. The remnant loxP site is very rich in CpG dinucleotides. As CpGs are substrates for DNA methylation, methylated CpGs may be involved in inactivating the region, leading to the repression of Jλ1 germline transcription. It has been shown that hypomethylation is correlated with V(D)J recombination activity 36 37 38.

Alternatively, the additional 150 nucleotides of the remnant loxP site might directly interfere with transcription initiation from the Jλ1 promoter. In another study, a loxP remnant was reported to have no effect on VJ recombination in the Igκ locus, nor to affect Jκ germline transcription 39. In that study, the loxP site was located farther away from the Jκ RSS (2 kb). Also, the flanking region of the loxP site was different from ours.

Finally, the loxP site remaining in the “S” mutation may disrupt a Jλ proximal regulatory element similar to the κI/κII sequences which are important for Jκ gene rearrangement 39.

As the cre-loxP system is extensively used to eliminate potential effects of the selectable marker in targeted loci, it is important to consider possible consequences of retaining a loxP site. The loxP flanked marker gene should be placed at a safe distance from any essential control element, and the constitution of the polylinker region should be considered.

The Levels of Jλ1 Germline Transcription Are Highly Correlated with VJ Recombination.

What is the molecular mechanism for the PGK-neo effect? As the PGK promoter is a strong housekeeping promoter, it is presumably active in all cells. Clearly, transcripts from the S-n allele initiating upstream of Jλ1 can be detected in both large pro-, pre-B cells (stages A–C of the Hardy nomenclature 40) and in T cells, where germline transcripts from the wild-type allele are not found (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6). Nevertheless, Jλ1 germline transcription is not sufficient to promote λ1 rearrangement in either T cells or in the early B cell stage (Fig. 2 C). We find no rearranged λ1 band in the thymus from an S-n/ S-n mouse (Fig. 2 C). The Vλ1Jλ1 joints found in the S-n/S-n homozygous targeted mice do not show an increase in N additions (Table ), as would be expected if the rearrangement took place as early as Ig heavy chain gene rearrangement in B cell development when TdT is expressed 41.

The lack of VJλ1 rearrangement in thymus and large preB cells of S-n/S-n mice is not due to lack of Vλ1 germline transcription. Surprisingly, Vλ1 germline transcripts are apparently present in both large pre-B cells and thymus RNA (not shown). We also found Vλ1 germline transcripts in thymus RNA from wild-type mice (data not shown). We consider two possibilities: The germline transcription of Vλ1 might not reflect the same chromatin structure alteration required for V(D)J recombination in the J region. Indeed, a recent study showed an unusual profile of germline transcription, nuclease sensitivity, and methylation of the V regions in the TCR-β locus, suggesting that the V region might use a unique structural conformation to be accessed by the V(D)J recombinase complex 42. Second, the germline transcription of Vλ1 might suggest constitutively open chromatin at that region in B and T cells. Therefore, the V(D)J recombination complex may be able to access Vλ1 region all the time. Thus, the lack of rearrangement of the S-n allele in large pre-B and T cells most likely indicates that rearrangement also requires activation of the λ enhancers by transactivating factors and that this does not occur until the small pre-B stage, when λ1 rearrangement normally takes place. At this stage, the germline Jλ1 promoter is active (Fig. 6) and all other required elements for λ1 rearrangement are functional.

In small pre-B cells, the level of the germline transcripts from the S-n allele is clearly higher than that from the wild-type allele (Fig. 5 B). It is possible that there is a difference in the stability between the endogenous and the PGK-neo inserted transcripts. However, as Ig transcripts, generally, are very stable, there is no reason to expect that the wild-type transcripts would be less stable than the transcripts from the targeted locus. Therefore, the presence of PGK-neo upstream of the Jλ1 RSS most likely causes upregulation of germline transcription. There are at least two possible models how the levels of germline transcription may affect λ1 rearrangement efficiency. In G/S-n mice, the increased germline transcription of the targeted allele compared with the wild-type allele could represent a more completely opened chromatin around the Jλ1 RSS via ATP-dependent remodeling and acetylation of histones 43 44. The more open RSS configuration would be more accessible to limiting quantities of V(D)J recombination components. Conversely, in the neo-deleted mice, in the presence of the CpG-rich loxP remnant, chromatin condensation could persist via the binding of methylated DNA binding proteins and possible recruitment of histone deacetylases 43 45. The chromatin condensation could make the RSS directly inaccessible or prevent transcription from the germline Jλ1 promoter.

Alternatively, the germline transcription complexes themselves could be involved in the upregulation of VJ recombination. In light of the previous findings of inhibition of rearrangement by PGK-neo when inserted into the JC intron and transcribing away from the RSS, our findings would be well explained by an enhancement of V(D)J recombination by transcription through the RSS. Perhaps components of the V(D)J recombinase could be associated with transcription complexes during transcript elongation and be more efficiently deposited at the RSS. It is likely that open chromatin exists in small pre-B cells at both the wild-type and S-n Jλ1 RSSs, as transcripts are seen. However, in an S-n allele with the PGK promoter, transcript initiation occurs at a higher rate allowing more transcription complexes to clear the promoter and possibly to carry V(D)J recombination factors to the RSS during transcript elongation. It would be interesting to turn around the PGK promoter both in the λ and κ loci. Perhaps, no more enhancement of Jλ1 rearrangement would be found, because the PGK initiated transcripts do not pass through this RSS anymore. Further, if directionality is not an issue, κ gene rearrangement may actually be enhanced by transcripts passing through the Jκ RSS in the opposite orientation.

However, to boost rearrangement, the transcripts may have to initiate at an Ig germline promoter. The presence of enhancer elements in PGK-neo may nonspecifically upregulate transcription from the germline Jλ1 promoter when the λ enhancers are active. It appears that there are more transcripts initiating at the PGK promoter than at the germline Jλ1 promoter in small pre-B cells (not shown). However, it is possible that the majority of the transcripts are from small pre-B cells that are unable to rearrange VJλ1.

It is clear that the accessibility to V(D)J recombination is controlled at several levels besides the requirement for the recombinase complex. Every Ig or TCR gene segment has not only its own RSS but also its own germline promoter whose activity is required for V(D)J recombination. RSS strength has been shown to affect the recombination frequencies 46 47 48. Our findings suggest that there is a potential secondary level of control in which the absolute activity of a germline promoter determines the absolute efficiency of recombination. The gene segment carrying a strong promoter will have a greater chance to be rearranged than the one with a weak promoter in the same locus. This, besides RSS quality, may explain the different intrinsic rearrangement efficiencies of different V, (D), and J regions in the Ig and TCR loci.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. B. Bogen, D. Huszar, A. Nagy, and H. Westphal for the gift of reagents and mice. We also thank L. Degenstein for the production of the knock-in mice, J. Auger and M. Wade for help with the FACS®, G. Bozek for excellent technical help, and P. Engler and N. Michael for helpful comments on the paper.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI39535. The FACS®, DNA sequencing, oligonucleotide synthesis, and transgenic facilities are supported by an National Institutes of Health grant to the University of Chicago Cancer Research Center.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: ES, embryonic stem; PGK, phosphoglycerine kinase; RSS, recombination signal sequence; RT, reverse transcription.

References

- Ramsden D., van Gent D., Gellert M. Specificity in V(D)J recombinationnew lessons from biochemistry and genetics. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1997;9:114–120. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grawunder U., West R.B., Lieber M.R. Antigen receptor gene rearrangement. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1998;10:172–180. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80246-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlissel M., Stanhope-Baker P. Accessibility and the developmental regulation of V(D)J recombination. Semin. Immunol. 1997;9:161–170. doi: 10.1006/smim.1997.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alt F.W., Blackwell T.K., Yancopoulos G.D. Development of the primary antibody repertoire. Science. 1987;238:1079–1087. doi: 10.1126/science.3317825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancopoulos G.D., Alt F.W. Developmentally controlled and tissue-specific expression of unrearranged VH gene segments. Cell. 1985;40:271–281. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Young F., Bottaro A., Stewart V., Smith R., Alt F.W. Mutations of the intronic IgH enhancer and its flanking sequences differentially affect the accessibility of the JH locus. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1993;12:4635–4645. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serwe M., Sablitzky F. V(D)J recombination in B cells is impaired but not blocked by targeted deletion of the immunoglobulin heavy chain intron enhancer. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1993;12:2321–2327. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05886.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauzurica P., Krangel M.S. Temporal and lineage-specific control of T cell receptor alpha/delta gene rearrangement by T cell receptor alpha and delta enhancers. J. Exp. Med. 1994;179:1913–1921. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.6.1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman J.R., van der Stoep N., Monroe R., Cogne M., Davidson L., Alt F.W. The Ig(kappa) enhancer influences the ratio of Ig(kappa) versus Ig(lambda) B lymphocytes. Immunity. 1996;5:241–252. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80319-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Davidson L., Alt F., Baltimore D. Deletion of the Igk light chain intronic enhancer/matrix attachment region impairs but does not abolish VkJk rearrangement. Immunity. 1996;4:377–385. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80251-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleckman B.P., Bardon C.G., Ferrini R., Davidson L., Alt F.W. Function of the TCR alpha enhancer in alphabeta and gammadelta T cells. Immunity. 1997;7:505–515. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80372-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz D.G., Oettinger M.A., Schissel M.S. V(D)J recombinationmolecular biology and regulation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1992;10:359–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.002043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessandrini A., Desiderio S.V. Coordination of immunoglobulin DJH transcription and D-to-JH rearrangement by promoter-enhancer approximation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991;11:2096–2107. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.4.2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alt F.W., Rosenberg N., Enea V., Siden E., Baltimore D. Multiple immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene transcripts in Abelson murine leukemia virus-transformed lymphoid cell lines. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1982;2:386–400. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.4.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ness B.G., Weigert M., Coleclough C., Mather E.L., Kelley D.E., Perry R.P. Transcription of the unrearranged mouse C kappa locussequence of the initiation region and comparison of activity with a rearranged V kappa-C kappa gene. Cell. 1981;27:593–602. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90401-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleckman B., Goerman J., Alt F. Accessibility control of antigen-receptor variable-region gene assemblyrole of cis-acting elements. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1996;14:459–481. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel H., Rolink A., Weiss S. B cells are programmed to activate kappa and lambda for rearrangement at consecutive developmental stages. Eur. J. Immunol. 1999;29:2167–2176. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199907)29:07<2167::AID-IMMU2167>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda S., Zou Y., Bluethman H., Kitamura D., Muller U., Rajewsky K. Deletion of the immunoglobulin κ chain intron enhancer abolishes κ chain gene rearrangement in cis not λ gene rearrangement in trans. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1993;12:2329–2336. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05887.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Trounstine M., Kuraha C., Young F., Kuo C., Xu Y., Loring J., Alt F., Huszar D. B cell development in mice that lack one or both immunoglobulin κ light chain genes. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1993;12:821–830. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05722.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y., Gu H., Rajewsky K. Generation of a mouse strain that produces immunoglobulin κ chains with human constant regions. Science. 1993;262:1271–1274. doi: 10.1126/science.8235658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazer J.K., Capra J.D. Immunoglobulinsstructure and function. In: Paul W., editor. Fundamental Immunology. 4th ed. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia, PA: 1999. pp. 47–74. [Google Scholar]

- Miller J., Ogden S., McMullen M., Andres H., Storb U. The order and orientation of mouse lambda genes explain lambda rearrangement patterns. J. Immunol. 1988;141:2497–2502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy A., Moens C., Ivanyi E., Pawling J., Gertsenstein M., Hadjantonakis A.K., Pirity M., Rossant J. Dissecting the role of N-myc in development using a single targeting vector to generate a series of alleles. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:661–664. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.Y., Kurtz B., Huszar D., Storb U. Crossing the SJL λ locus into κ-knockout mice reveals a dysfunction of the λ1-containing immunoglobulin receptor in B cell differentiation. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1994;13:827–834. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakso M., Pichel J., Gorman J., Sauer B., Okamoto Y., Lee E., Alt F., Westphal H. Efficient in vivo manipulation of mouse genomic sequences at the zygote stage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:5860–5865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storb U., Haasch D., Arp B., Sanchez P., Cazenave P., Miller J. Physical linkage of mouse λ genes by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis suggests that the rearrangement process favors proximate target sequences. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1989;9:711–718. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.2.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss S., Lehmann K., Cohn M. Monoclonal antibodies to murine immunoglobulin isotypes. Hybridoma. 1983;2:49–54. doi: 10.1089/hyb.1983.2.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogen B. Monoclonal antibodies specific for variable and constant domains of murine lambda chains. Scand. J. Immunol. 1989;29:273–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1989.tb01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y.R., Takeda S., Rajewsky K. Gene targeting in the Ig kappa locusefficient generation of lambda chain-expressing B cells, independent of gene rearrangements in Ig kappa. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1993;12:811–820. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney A.J. Lack of N regions in fetal and neonatal mouse immunoglobulin V-D-J junctional sequences. J. Exp. Med. 1990;172:1377–1390. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.5.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez P., Drapier A.M., Cohen-Tannoudji M., Colucci E., Babinet C., Cazenave P.A. Compartmentalization of lambda subtype expression in the B cell repertoire of mice with a disrupted or normal C kappa gene segment. Int. Immunol. 1994;6:711–719. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudinot P., Rueff-Juy D., Drapier A., Cazenave P., Sanchez P. Various V-J rearrangement efficiencies shape the mouse lambda B cell repertoire. Eur. J. Immunol. 1995;25:2499–2505. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bories J.C., Demengeot J., Davidson L., Alt F.W. Gene-targeted deletion and replacement mutations of the T-cell receptor beta-chain enhancerthe role of enhancer elements in controlling V(D)J recombination accessibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:7871–7876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artelt P., Grannemann R., Stocking C., Friel J., Bartsch J., Hauser H. The prokaryotic neomycin-resistance-encoding gene acts as a transcriptional silencer in eukaryotic cells. Gene. 1991;99:249–254. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90134-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada A., Mendelsohn M., Alt F. Differential activation of transcription versus recombination of transgenic T cell receptor beta variable region gene segments in B and T lineage cells. J. Exp. Med. 1994;180:261–272. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler P., Haasch D., Pinkert C., Doglio L., Glymour M., Brinster R., Storb U. A strain specific modifier on mouse chromosome 4 controls the methylation of independent transgene loci. Cell. 1991;65:939–947. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90546-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh C.-L., Lieber M.R. CpG methylated minichromosomes become inaccessible for V(D)J recombination after undergoing replication. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1992;11:315–325. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler P., Weng A., Storb U. Influence of CpG methylation and target spacing on V(D)J recombination in a transgenic substrate. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993;13:571–577. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.1.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferradini L., Gu H., De Smet A., Rajewsky K., Reynaud C.A., Weill J.C. Rearrangement-enhancing element upstream of the mouse immunoglobulin kappa chain J cluster. Science. 1996;271:1416–1420. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5254.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy R.R., Carmack C.E., Shinton S.A., Kemp J.D., Hayakawa K. Resolution and characterization of pro-B and pre-pro-B cell stages in normal mouse bone marrow. J. Exp. Med. 1991;173:1213–1225. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.5.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau N.R., Schatz D.G., Rosa M., Baltimore D. Increased frequency of N-region insertion in a murine pre-B-cell line infected with a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase retroviral expression vector. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1987;7:3237–3243. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.9.3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu N., Hempel W.M., Spicuglia S., Verthuy C., Ferrier P. Chromatin remodeling by the T cell receptor (TCR)-β gene enhancer during early T cell developmentimplications for the control of TCR-β locus recombination. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:625–636. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.5.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston R., Narlikar G. ATP-dependent remodeling and acetylation as regulators of chromatin fluidity. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2339–2352. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.18.2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor McMurry M., Krangel M. A role for histone acetylation in the developmental regulation of V(D)J recombination. Science. 2000;287:495–498. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5452.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan X., Ng H., Johnson C., Laherty C., Turner R., Eisenman R., Bird A. Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature. 1998;393:386–389. doi: 10.1038/30764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J., Selsing E., Storb U. Structural alterations in J regions of mouse immunoglobulin lambda genes are associated with differential rearrangement patterns. Nature. 1982;195:428–430. doi: 10.1038/295428a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor A.M., Fanning L.J., Celler J.W., Hicks L.K., Ramsden D.A., Wu G.E. Mouse VH7183 recombination signal sequences mediate recombination more frequently than those of VHJ558. J. Immunol. 1995;155:5268–5272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsden D.A., Wu G.E. Mouse kappa-light-chain recombination signal sequences mediate recombination more frequently than do those of lambda-light chain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:10721–10725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]