Abstract

After injury or infection, neutrophils rapidly migrate from the circulation into tissues by means of an orderly progression of adhesion receptor engagements. Neutrophils have been previously considered to use selectins exclusively to roll on vessels before an adhesion step mediated by the β2 integrins, lymphocyte function–associated antigen (LFA)-1, and Mac-1. Here we use LFA-1−/− mice, function blocking monoclonal antibodies, and intravital microscopy to investigate the roles of LFA-1, Mac-1, and α4 integrins in neutrophil recruitment in vivo. For the first time, we show that LFA-1 makes a contribution to neutrophil rolling by stabilizing the transient attachment or tethering phase of rolling. In contrast, Mac-1 does not appear to be important for either rolling or firm adhesion, but instead contributes to emigration from the vessel. Blocking Mac-1 in the presence of LFA-1 significantly reduces emigration, suggesting cooperation between these two integrins. Low levels of α4β1 integrin can be detected on neutrophils from LFA-1+/+ and −/− mice. These cells make use of α4β1 during the rolling phase, particularly in the absence of LFA-1. Thus LFA-1 and α4β1, together with the selectins, are involved in the rolling phase of neutrophil recruitment, and, in turn, affect the later stages of the transmigration event.

Keywords: LFA-1, integrin, rolling, neutrophils, inflammation

Introduction

Neutrophils are the first arrivals at sites of inflammation, responding actively to signals produced by the vasculature early in an immune response 1. To migrate from the circulation across postcapillary venules and into tissues, neutrophils and other leukocytes make use of selectin and integrin adhesion receptors in a sequence of several overlapping steps. The current model is that neutrophil velocity is decreased through the selectins, enabling them to roll along the vessel wall. Endothelial cell–bound factors, such as platelet-activating factor or chemokines, then cause activation of neutrophil CD18 (β2) integrins. Using their activated integrins, neutrophils flatten and move along the endothelium before migrating across the blood vessel wall into the surrounding tissue along a gradient of chemotactic factors.

Previously, neutrophils have been thought to express β2 but not β1 (CD29) integrins, although more recently α4 integrins have been identified on these leukocytes (for a review, see reference 2). However, it is the two main β2 integrins, lymphocyte function–associated antigen (LFA)-1 (CD11a/CD18) and Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18), which neutrophils are reported to utilize in models of inflammation in human 3 4, rabbit 5, rat 6, and mouse (for a review, see references 7 and 8). Questions remain as to their individual roles. In one model, Mac-1 was shown to be the predominant β2 integrin used during neutrophil migration into the peritoneum 3 9. In further studies, LFA-1 was identified as the principal neutrophil integrin used during transendothelial migration 5 10. The use of mice deficient in the β2 integrins Mac-1 or LFA-1 has suggested a division of function between these two integrins. LFA-1 is considered chiefly to control transmigration with Mac-1 involved in other neutrophil functions, such as apoptosis, degranulation, and iC3b-mediated phagocytosis 10 11 12 13 14. Confusingly, in studies with the CD18−/− mouse, CD18 integrins were reported to have no role in response to lung or peritoneal inflammation 15. These variable results have been attributed to species differences, the effects of integrin deficiency on circulating leukocyte numbers, and differences in the inflammatory agents and models employed.

We have examined the respective roles of LFA-1, Mac-1, and α4 integrin in neutrophil migration into the inflamed peritoneum. To further define the roles of these three integrins in neutrophil behavior, in this model we have compared the responses of LFA-1−/− mice with their wild-type counterparts in the presence and absence of function blocking mAbs. In addition, intravital microscopy has been used to further clarify the functions of the individual leukocyte integrins.

Materials and Methods

LFA-1− /− and Littermate+/+ Mice.

LFA-1−/− and +/+ mice were derived and maintained as described previously 16. Sex-matched, 10–14-wk-old mice were used in the experiments. All animal work was performed according to UK Government Home Office Regulations (1986).

Preparation of mAbs and Fab Fragments.

The following purified rat mAbs were used to block integrin function in this study: H68 (LFA-1, CD11a; IgG2a), PS2/3 (α4 integrin, CD49d; IgG2b), and 5C6 (Mac-1, CD11b; IgG2b; reference 9) (obtained from Dr. Siamon Gordon, Oxford University, Oxford, UK). Purified mAbs H68, PS2/3, and 5C6, plus control mAbs PyLT-1 (IgG2b) or YB238 (IgG2a), were prepared by the Imperial Cancer Research Fund Research Monoclonal Antibody Service. Fab fragments were generated as specified by the manufacturer using the ImmunoPure® Fab kit (Pierce Chemical Co.), purified by using a protein G Sepharose column, and tested for purity by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis. All mAb IgGs and Fabs were assessed for denaturation/aggregation by SDS-PAGE and flow cytometry using murine PBLs.

Flow Cytometric Analysis.

Mice were tail bled 4 h after induction of peritonitis. Blood was diluted 1:5 in PBS, 1.5% dextran T500 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and RBCs were sedimented for 30 min. Unsedimented white blood cells were further isolated on Histopaque 1119 (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Lavage and blood cells were centrifuged (500 g for 10 min at 4°C) and resuspended in FACSwash™ (PBS, 0.2% BSA, and 1% normal goat serum). Samples of 0.5–1 × 106 cells were treated for 30 min with 10 μg/ml mAb 2.4G2 (BD PharMingen), in order to block Fcγ II/III receptors. Cells were then stained with the following mAbs at an optimal concentrations (2–10 μg/ml) for 25 min at 4°C followed by three washes in FACSwash™. The following mAbs are unconjugated (Imperial Cancer Research Fund) or directly conjugated/biotinylated (BD PharMingen) and specific for: LFA-1 (H68), Mac-1 (5C6 and M1/70-biotin), L-selectin (Mel-14-biotin), α4 integrin (PS2/3, R1-2-FITC, 9C10-biotin), IgG2b isotype (PyLT-1, A95-1-biotin, A95-1-FITC), and IgG2a isotype (R35-95-biotin, YB238). Unconjugated and biotinylated mAb binding to cells was detected by incubation with FITC-conjugated goat anti–rat IgG (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) or tricolor-streptavidin (1:200; Caltag), respectively. Neutrophils were identified on the basis of subsequent staining with 7/4-PE (Serotec) and/or Gr-1(RB6-8C5-FITC) in conjunction with scatter profiles. After three washes, the cells were resuspended in PBS containing 2% formaldehyde and cell fluorescence was measured on a FACSCalibur™ (Becton Dickinson).

Peritoneal Inflammation.

Peritonitis was induced by intraperitoneal injections of thioglycollate (TG) (3% wt/vol in 0.5-ml sterile saline; Sigma-Aldrich). 4 h later, the mice were euthanized by carbon-dioxide exposure, and peritoneal cavities were lavaged with 5 ml PBS containing 3 mM EDTA and 25 U/ml monoparin (CP Pharmaceuticals). Leukocytes were counted and the proportion of neutrophils determined by mAb 7/4 staining and flow cytometry. Alternatively, leukocytes were stained with Turk's solution (0.01% crystal violet in 3% acetic acid) and neutrophils were counted. In peritonitis and intravital experiments, either 100 μg of purified Fab (all intravital experiments) or 130 μg of intact mAb diluted in PBS was injected intravenously into the tail vein 15 min before the TG injection. Over the course of the 4-h experiment, this amount of mAb fully saturated the circulating neutrophils and, where tested, the lavage neutrophils (data not shown).

Intravital Microscopic Studies.

4 h after TG injection, the mesenteric vascular bed was prepared for microscopy 17. Mice were anesthetized with diazepam (60 mg/kg subcutaneously) and hypnorm™ (0.7 mg/kg fentanyl citrate and 20 mg/kg fluanisone, intramuscularly). Cautery incisions were made along the abdominal region and the mesentery vascular bed was exteriorized and placed on a viewing plexiglass stage. The preparation was mounted on a Zeiss Axioskop “FS” (original magnification: 40×) to observe the microcirculation and transilluminated with a 12-V, 100-W halogen light source. Mesenteries were superfused with bicarbonate-buffered solution (g/liter: 7.71 NaCl, 0.25 KCl, 0.14 MgSO4, 1.51 NaHCO3, and 0.22 CaCl2, pH 7.4, at 37°C, gassed with 5% CO2/95% N2) at a rate of 2 ml/min. A Hitachi CCD color camera (KPC571) acquired images which were displayed on a Sony Trinitron color video monitor (PVM 1440QM) and recorded on a Sony super VHS video cassette recorder (SVO-9500 MDP) for subsequent offline analysis. A video time-date generator (FOR.A video timer, VTG-33) projected the time, date, and stopwatch function onto the monitor.

Wall shear rate (SR) was calculated by the Newtonian definition: SR = 8,000× (Vmean/diameter) and expressed in s−1. One to three randomly selected postcapillary venules (diameter between 20–40 μm; length of at least 100 μm) were observed for each mouse. White blood cell velocity in millimeters per second was calculated from time taken for a leukocyte to roll along 100 mm of vessel wall. Cell flux was calculated by counting, in the vessel, the number of white blood cells passing through a theoretical 90° plane in a 5-min period. Data are expressed as cells per min. Cell adhesion for each vessel was quantified by counting the number of adherent neutrophils in a 100-μm length. Leukocytes stationary for at least 30 s were defined as adherent. Leukocyte emigration from the microcirculation into the tissue was measured by counting the number of leukocytes that had emigrated up to 50 mm away from the wall per 100 μm-vessel segment.

Statistics.

Statistics were calculated on original values by using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Bonferroni test for intergroup comparisons. The alternate Student's t test was used when two groups were analyzed. In all cases a threshold value of P < 0.05 was considered as the minimum level of significance.

Results and Discussion

Neutrophil Migration into the Peritoneum After an Inflammatory Stimulus.

To assess the role of LFA-1 in neutrophil migration to extravascular sites in response to an inflammatory stimulus, LFA-1−/− and +/+ mice were compared using the TG-induced peritonitis model. Mice were killed at 0, 4, 10, 16, and 24 h after injection and neutrophil emigration into the peritoneal cavity was quantified. The migration of neutrophils was evident at 4 h, and reached a maximal level at 16 h which was maintained until 24 h (data not shown). At the 4-h time point, 50% fewer neutrophils migrated in the LFA-1−/− mouse compared with the LFA-1+/+ (Fig. 1). As circulating blood neutrophils were in higher concentration in the LFA-1−/− mice (4.4 ± 0.5 × 106 cells per milliliter (n = 9) as compared with 0.8 ± 0.1 × 106 cells per milliliter (n = 12) in the LFA-1+/+ mice), this represents an ∼10-fold greater efficiency of migration by the wild-type LFA-1 neutrophils. This finding is in agreement with previous studies in mouse 10, rat 6, and rabbit 5, in which a function blocking LFA-1 mAb substantially inhibited neutrophil migration. Other studies making use of LFA-1−/− mice also report similar results 11 12 13 14.

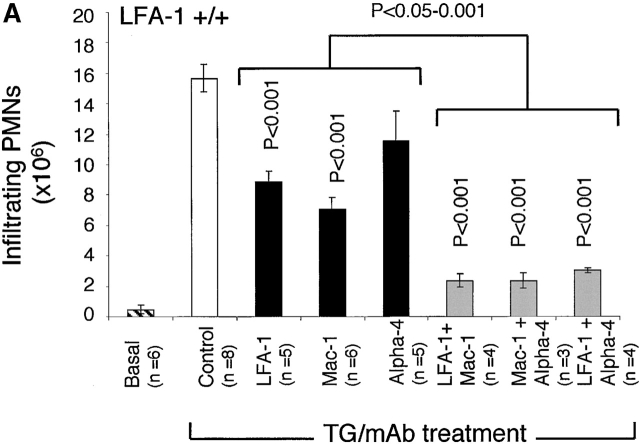

Figure 1.

The migration of neutrophils at 4 h after TG treatment into the peritoneum of LFA-1+/+ and −/− mice in the presence of mAbs specific for LFA-1, Mac-1, and α4 integrins either singly or in combination. For LFA-1+/+ mice, anti–LFA-1 and anti–Mac-1 mAbs, when administered alone, significantly inhibit neutrophil migration. All mAb pairs were significantly effective in inhibiting migration compared with the control. In addition, all pairs of mAbs block significantly more than single mAbs (P < 0.001), indicating that α4 integrin cooperates with LFA-1 and Mac-1 in the migration of LFA-1+/+ neutrophils. For LFA-1−/− mice, only anti-α4 integrin inhibits neutrophil migration as a single mAb and does not inhibit more significantly when in combination with anti–Mac-1 mAb (α4 versus α4/Mac-1 mAbs; P > 0.05). These data are representative of three complete experiments which utilized 3–10 mice per condition per experiment. Data are reported as mean ± SEM.

Integrins Involved in Neutrophil Transmigration in LFA-1− /− Versus LFA-1+ /+ Mice.

To investigate which integrins have a role in the migration of neutrophils into the peritoneum, LFA-1−/− and +/+ mice were injected intravenously with anti–LFA-1, Mac-1, or α4 integrin mAb 15 min before the injection of TG into the peritoneal cavity. In LFA-1+/+ mice, the anti–LFA-1 and the anti–Mac-1 mAbs significantly inhibited neutrophil migration (Fig. 1 A). The effect of the α4 mAb was less pronounced. When the mAbs were tested in pairs, each combination caused a further decrease in neutrophil emigration compared with the single mAbs. This suggests that all three integrins cooperate in the movement of neutrophils from the circulation to the final destination of the peritoneum, with LFA-1 and Mac-1 having dominant roles.

As expected, anti–LFA-1 mAb was ineffective at preventing the migration of neutrophils in LFA-1−/− mice in response to the TG injection (Fig. 1 B). Surprisingly, anti–Mac-1 alone was also ineffective in blocking migration. However, anti-α4 mAb significantly blocked migration. There was no further significant difference between α4 mAb alone or when coinjected with anti–Mac-1 mAb (P > 0.05). Similar results were obtained in both LFA-1+/+ and −/− mice with Fab fragments (data not shown). These results suggest that, while normal neutrophils make use of Mac-1, LFA-1, and α4 integrin to access the peritoneal environment, the LFA-1–deficient neutrophils emigrate using α4 integrin with a less significant role for Mac-1.

Phenotypic Characteristics of LFA-1− /− and +/+ Neutrophils in the Circulation and Peritoneum.

Since the LFA-1−/− neutrophils were able to migrate into sites of inflammation by making use of α4 integrin, it was of interest to compare the expression of this integrin, as well as Mac-1, on both LFA-1+/+ and −/− neutrophils. We also wished to determine whether integrin expression was altered between circulating and emigrated neutrophils. As expected, expression of the β2 integrin LFA-1 was absent on neutrophils from LFA-1−/− mice (data not shown). The levels of Mac-1 were similar on peripheral blood neutrophils both before (Fig. 2 A) and after TG stimulation (data not shown). However, expression of Mac-1 was increased on peritoneal neutrophils compared with peripheral blood neutrophils and this upregulation occurred to a greater degree in LFA-1–deficient mice. As neutrophils with this higher level of expression of Mac-1 are not represented in the circulating pool at 4 h after TG, Mac-1 must be upregulated after contact with the endothelium or subendothelial tissue matrix. This increase in Mac-1 expression does not account for the lack of blocking effect of anti–Mac-1 mAb on LFA-1−/− neutrophil migration (Fig. 1) as levels of injected mAbs were saturating on both circulating and peritoneal lavage neutrophils (n = 2 experiments; data not shown).

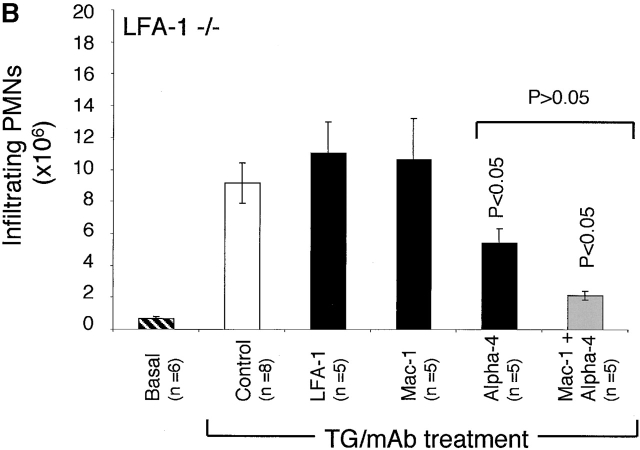

Figure 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of LFA-1+/+ and −/− neutrophils in the circulation and after extravasation into the peritoneum. Expression of (A) Mac-1 detected with mAb M1/70 biotin and (B) α4 integrin detected with mAb 9C10-biotin. Geometric means of the major peak are shown in the top right hand corner. Data are representative of five experiments with blood and lavage cells pooled from five and two mice, respectively.

α4 integrin was expressed on circulating neutrophils, with no further increase on lavage neutrophils (Fig. 2 B). Detection of α4 integrin with three specific mAbs paired with matched isotype controls and with prior blocking of FcR (Materials and Methods), gives confidence that the neutrophils under study do express this class of integrin. Positive staining with α4 and β1 mAbs, but not β7- nor α4β7-specific mAbs indicated that the α4 integrin expressed by neutrophils was α4β1 rather than α4β7 (data not shown). Unlike Mac-1 expression there was no discernible difference in expression of α4β1 on the lavage cells of LFA-1+/+ and −/− mice (Fig. 2 B). A subset comprising ∼10% of neutrophils expressed higher levels of α4β1. These cells may represent less mature bone marrow–derived neutrophils 18 as characteristic mAb staining and scatter properties distinguished these cells from monocytes (intermediate mAb Gr-1 expression) and eosinophils (no mAb Gr-1 staining and distinctive high side scatter; data not shown). The expression of α4 integrin by neutrophils has been controversial because flow cytometric studies have suggested that, unlike other leukocytes, neutrophils express only β2 integrins. However, recent studies in rodents (for a review, see reference 2) and now functional studies in humans 4 have provided evidence for α4 integrin expression and use by neutrophils.

The Use of Intravital Microscopy to Examine LFA-1+ /+ and LFA-1− /− Neutrophils in Response to TG Treatment.

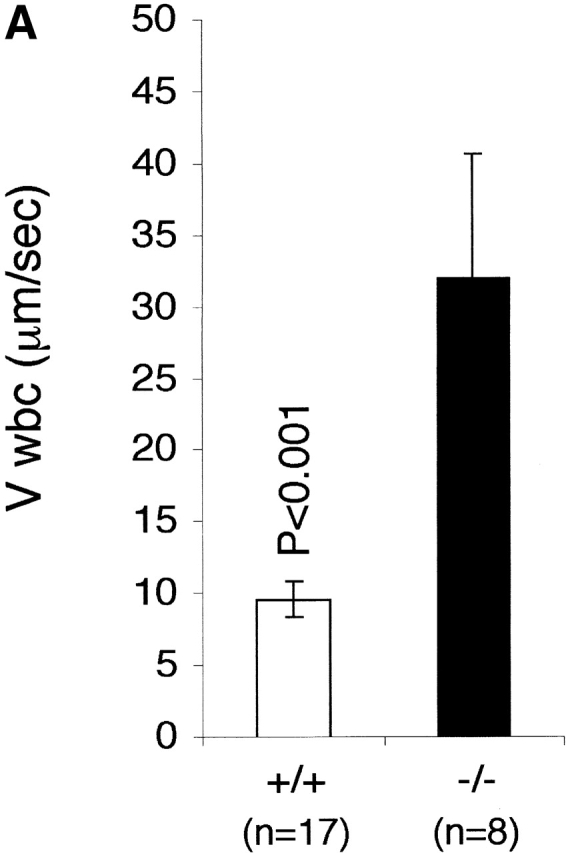

Leukocytes migrate across the postcapillary venules of the mesentery after introduction of a stimulant into the peritoneum. Intravital microscopy was used to investigate whether the absence of LFA-1 had any effect on the rolling of the leukocytes along the mesenteric venules. Additionally, it allowed assessment of the importance of LFA-1 in adhesion to, as well as emigration from, the mesenteric venules. In LFA-1+/+ mice, the leukocytes rolled with a velocity of 9.7 ± 1.2 μm/s after 4 h of exposure to TG (Fig. 3 A). For the LFA-1−/− mice, the velocity of leukocyte rolling was significantly increased to 32.1 ± 8.9 μm/s, indicating that LFA-1 participates in rolling along the mesenteric vessels after an inflammatory stimulus. Histology of stimulated mesenteric vessels showed the rolling cells to be neutrophils (unpublished data). The velocity of neutrophil rolling is dependent not only on the activity of adhesion receptors on both the leukocyte and the endothelium, but also on the diameter of the postcapillary venules and the SR at the vessel wall. The velocity increase observed could be attributed to adhesion receptor expression as there was no significant difference in these two parameters in LFA-1−/− and +/+ vessels (Table ).

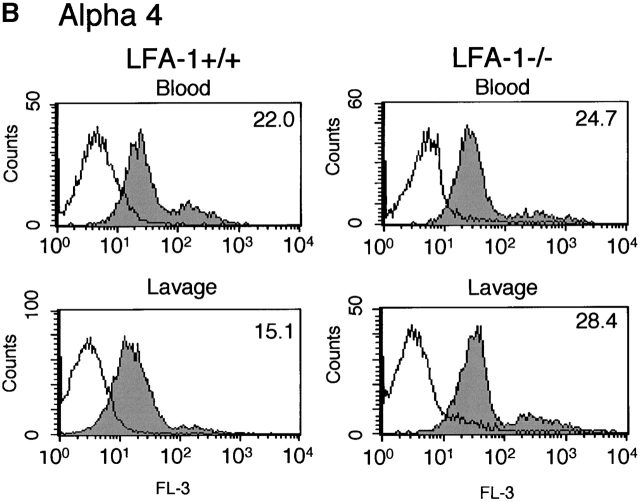

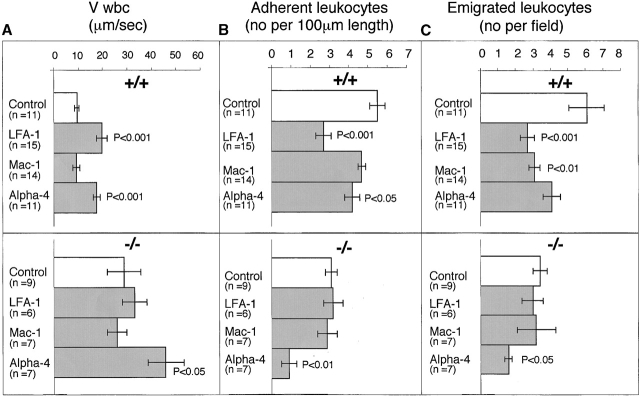

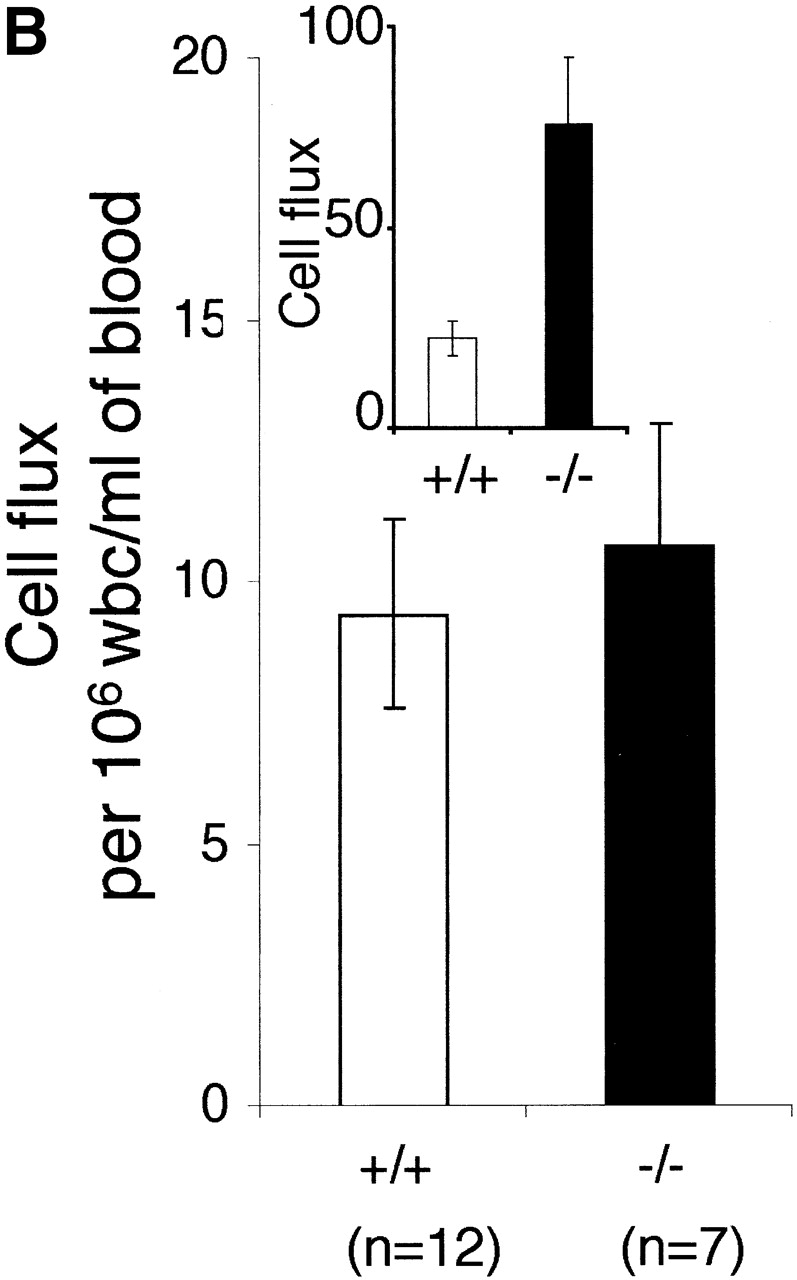

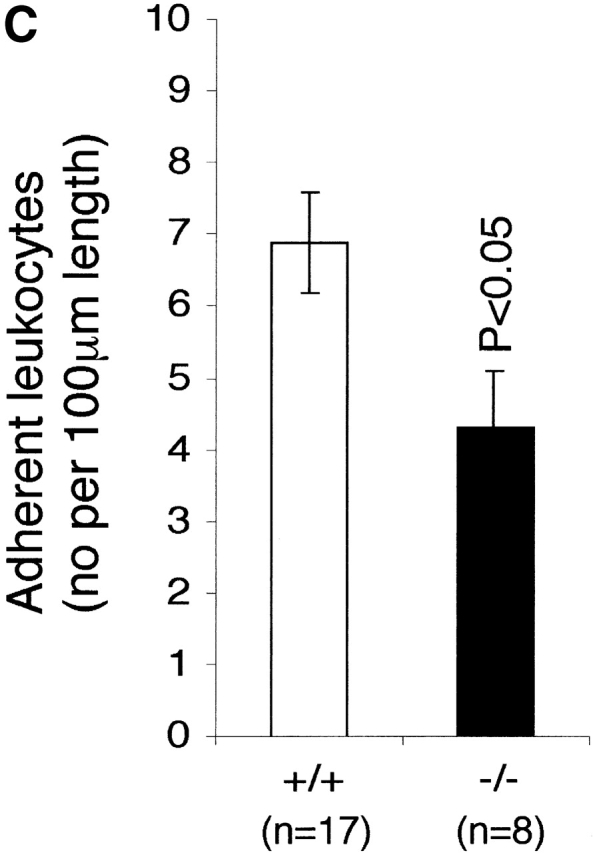

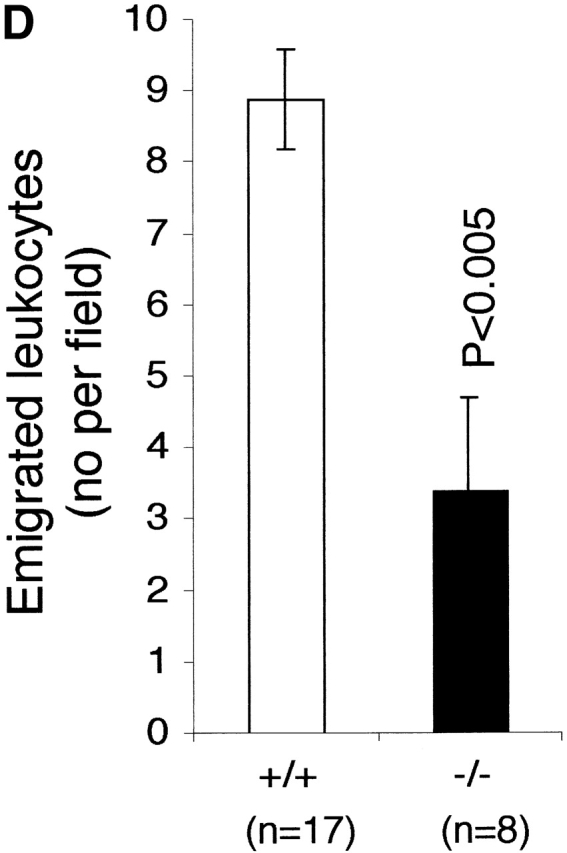

Figure 3.

The effect of LFA-1 deficiency on neutrophil rolling, adhesion, and transmigration as detected by intravital microscopy. A comparison in LFA-1+/+ and −/− mice of leukocyte (A) velocity (VWBC); (B) integrated cell flux (i.e., cell flux per 106 leukocytes per milliliter of blood). Inset, basic cell flux (cells per min); (C) cell adhesion; (D) emigrated leukocytes per field (“field” represents cells within 50-μm distance from a 100-μm segment of vessel). The neutrophils from LFA-1−/− mice have a higher velocity than those from LFA-1+/+ mice indicating a role for LFA-1 in neutrophil rolling. Because LFA-1 does not alter the cell flux (frequency of contact with endothelium), it must be decreasing the velocity by transiently stabilizing the rolling cells. A lack of LFA-1 is also reflected in lower adhesion per 100-μm length of mesenteric vessel and decreased emigration from the vasculature by the LFA-1−/− as compared with LFA-1+/+ neutrophils. Data are reported as mean ± SEM.

Table 1.

Parameters Analyzed for Mesenteric Postcapillary Venules of LFA-1+/+ and LFA-1−/− Mice

| Parameter | LFA-1+/+ mice | LFA-1−/− mice |

|---|---|---|

| No. of mice | 17 | 8 |

| No. of venules | 35 | 17 |

| Venule diameter | 28.8 ± 0.8 μm | 29.6 ± 1.1 μm |

| Wall shear rate | 269 ± 27 s−1 | 287 ± 22 s−1 |

The number of mice used for LFA-1+/+ and LFA-1−/− groups is indicated, and the hemodynamic parameters of the venules studied after TG treatment are reported as mean ± SEM.

Most previous reports have restricted the role of LFA-1 to mediating firm adhesion and this is the first indication that it can participate in vivo in the rolling event. The velocity of the rolling leukocyte will be influenced by changes in either the “on” or “off” rate of binding to the endothelium. To further define where LFA-1 was affecting the rolling velocity, we investigated the “cell flux “or frequency of neutrophil encounter with the endothelium and observed a substantially larger number of leukocytes transiently adhering to endothelium in the LFA-1−/− compared with the LFA-1+/+ mice (Fig. 3 B, inset). However, when the increased numbers of leukocytes circulating in the LFA-1−/− mice were taken into account (Fig. 3, legend), the frequency of encounter with endothelium per 106 leukocytes per milliliter was not significantly different between LFA-1+/+ and −/− mice (Fig. 3 B). Considered together, these observations indicate that the lack of LFA-1 did not significantly affect the on or attachment phase of the rolling interaction. However, in the absence of LFA-1, the stability of the brief attachment or tethering phase of rolling was compromised resulting in a faster off rate.

These results suggest that during the rolling phase of the interaction with endothelium, LFA-1 may operate together with the selectins. We confirmed that expression levels ofL-selectin on LFA-1+/+ and − /− neutrophils were similar, indicating that the effect on rolling was not indirectly caused by loss of L-selectin, but was due to the absence of LFA-1 (data not shown). In another in vivo study, β2 integrin ligand, intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, cooperated with L- and P-selectin in leukocyte rolling, supporting the idea that β2 integrin is needed for optimal rolling–mediated by these two selectins 19. In contrast, two studies which have analyzed LFA-1 in the form of LFA-1–expressing K562 cells 20 or glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked LFA-1 I domain 21 show that this integrin can mediate rolling on isolated ICAM-1 under shear conditions in vitro. This suggests that LFA-1 can act as an independent rolling receptor in some contexts. However, the findings here suggest that under in vivo conditions, in the presence of other receptors involved in rolling such as the selectins, LFA-1 has a cooperative role in providing transient stability for the rolling cells.

Marked differences were observed between the LFA-1+/+ and −/− mice at each step of the recruitment pathway. The increase in neutrophil rolling velocity had an impact on adhesion to and transmigration across mesenteric vessels, as both were reduced in LFA-1−/− mice compared with the LFA-1+/+ mice. The numbers of neutrophils adhering to (4.3 ± 0.8 vs. 6.9 ± 0.7) and emigrating from (3.4 ± 1.3 vs. 8.9 ± 0.7) the vessels of LFA-1−/− versus +/+ mice were lower (Fig. 3c and Fig. d). The overall conclusion using intravital microscopy is that the absence of LFA-1 considerably increases the neutrophil rolling velocity along the postcapillary venules after an inflammatory stimulus which, in turn, reduces both cell adhesion to and emigration from the venules.

Effect of Anti-Integrin mAbs on Neutrophil Velocity Using Intravital Microscopy.

We next utilized function blocking Abs to examine the involvement of LFA-1, as well as Mac-1 and α4β1 in neutrophil rolling, adhesion, and transmigration. Investigation of LFA-1+/+ mice showed that the LFA-1 mAb significantly increased the velocity of neutrophil rolling (19.9 ± 2.3 vs. 9.6 ± 1.0 μm/s) as did the α4 mAb (17.7 ± 1.5 vs. 9.6 ± 1.0 μm/s) (Fig. 4 A). When the LFA-1−/− mice were similarly treated with mAbs to the individual leukocyte integrins, the velocity was increased significantly only by the α4 mAb (46.0 ± 7.4 vs. 29.0 ± 6.8 mm/s). Together these results indicate that both LFA-1 and α4 integrin participate in the rolling velocity of neutrophils on the mesenteric vessels after TG stimulation. It appears that two pathways are in place with LFA-1+/+ neutrophils making use of LFA-1 and α4β1 whereas, LFA-1−/− neutrophils are relying only on α4β1. Mac-1 has no part in this stage of the response to TG.

Figure 4.

The effect of mAbs specific for LFA-1, Mac-1, and α4 integrin on neutrophil rolling, adhesion, and migration in LFA-1+/+ and −/− mice. For LFA-1+/+ mice, anti–LFA-1 mAb significantly affected all three stages of rolling, adhesion, and emigration and anti-α4 mAb had significant impact on cell rolling and adhesion. Anti–Mac-1 mAb significantly affected the emigration step in LFA-1+/+ but not LFA-1−/− mice. In LFA-1−/− mice, only the α4 mAb significantly affects all three steps of rolling velocity, adhesion, and emigration. Data are reported as mean ± SEM.

This role for α4 integrins in neutrophil rolling is a new observation, but their participation in rolling and adhesion of eosinophils and other leukocytes has been well documented. The α4 integrins can mediate rolling of lymphocytes on the high endothelial venules of mucosal lymph nodes 22, of eosinophils on mesenteric vessels 23, and of murine hematopoietic progenitor cells on bone marrow microvessels 24. In fact, primary lymphocytes can use α4 integrin to roll on ligand, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, which indicates that α4 integrin can act independently of the selectins as a rolling receptor 22 25. In this context, the topological association of L-selectin and α4 integrin with neutrophil microvilli, compared with the restriction of LFA-1 to the neutrophil cell body, may have some bearing on their individual functions in the rolling phenomenon 22.

Effect of Anti-Integrin mAbs on Neutrophil Adherence Using Intravital Microscopy.

mAbs that increased the velocity of rolling also decreased the number of adherent leukocytes (Fig. 4 B). For the LFA-1+/+ mice, the anti–LFA-1 mAb (2.7 ± 0.4 vs. 5.5 ± 0.4) and α4 mAb (4.2 ± 0.4 vs. 5.5 ± 0.4) both decreased adhesion to the TG-stimulated venule. Only the α4 mAb decreased the adhesion of the LFA-1−/− leukocytes (0.9 ± 0.4 vs. 3.1 ± 0.3). Another study investigating neutrophil adherence under physiological SRs in vitro showed that they can adhere via α4 integrin independently of β2 integrins 26. Our results imply that where these integrins influence the velocity of rolling of the neutrophils, they also have impact on the firm adhesion to the same vasculature. A precedent for this conclusion comes from a shear flow model, in which, with subsecond timing, the chemokine stromal cell–derived factor 1 initiates α4 integrin–mediated T lymphocyte rolling along vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, and this rolling is then converted to arrest and firm adhesion 25. Since the process of leukocyte emigration is sequential, an effect on rolling would be expected to impact upon adhesion and ultimately transmigration.

Effect of Anti-Integrin mAbs on Neutrophil Emigration Using Intravital Microscopy.

Next the effect of blocking mAbs was tested on the emigration of leukocytes within a 50-μm distance per 100-μm length of vessel. For the LFA-1+/+ leukocytes, LFA-1 mAb-inhibited migration as was expected (2.7 ± 0.4 vs. 6.1 ± 1.0), but for the first time, mAb specific for the second β2 integrin, Mac-1, also showed a significant effect (3.1 ± 0.3 vs. 6. 1± 1.0; Fig. 4 C). The α4 mAb was the only mAb to significantly affect the numbers of emigrating cells in the LFA-1−/− mice (1.6 ± 0.2 vs. 3.4 ± 0.4).

Thus, we show that Mac-1 does cooperate with LFA-1 in the transmigration process, but the results challenge previous theories concerning where Mac-1 engagement occurs. In vitro studies measuring neutrophil adhesion to ICAM-1 under shear flow have suggested that cooperation occurs between LFA-1 and Mac-1 and that transient adhesion by LFA-1 promotes stable longer-lasting Mac-1–mediated adhesion 14 27 28. In this study, anti–Mac-1 mAb does not affect the phases of rolling or adhesion, but is effective at the level of emigration and consequently in the overall movement of neutrophils into the peritoneum (Fig. 1). We reasoned that the Mac-1 mAb could either be affecting transmigration across the mesenteric vessel or blocking a postendothelial event such as migration within the tissue extracellular matrix. If the second option were correct, then it would be expected that leukocytes would accumulate perivascularly in the presence of the mAb. Comparison of the video recordings of control versus Mac-1 mAb-treated preparations revealed no difference in the concentration of leukocytes in the immediate perivascular location (data not shown). Therefore, these results suggest a role for Mac-1 in the migration of leukocytes specifically across the endothelium itself. Interestingly, Mac-1 does not have the same impact on the α4-mediated emigration of LFA-1−/− neutrophils, suggesting that α4β1 can accomplish all the steps of the adhesion and transmigration process for LFA-1−/− neutrophils. Neutrophils from Mac-1−/− mice have enhanced migratory properties 10 13 14 in terms of their movement into inflammatory sites. Why their properties differ from neutrophils treated with anti–Mac-1 mAb is unclear.

In the inflammatory model used in this study we have shown that neutrophil LFA-1 can participate in rolling interactions with ligand on mesenteric vessels. This first stage then dictates the rest of the transmigration event. The fact that α4β1 is the principal integrin used by the LFA-1−/− neutrophils to extravasate highlights the fact that neutrophils basically have two integrin-based pathways available for exiting the circulation and migrating across the endothelium. In some situations, LFA-1 can suppress α4 integrin activity through an integrin “cross-talk” mechanism. This cross-talk does not feature here, as α4β1 contributes to the migratory response of LFA-1+/+ neutrophils, in combination with the other β2 integrins LFA-1 and Mac-1. The α4β1-mediated mechanism is not as efficient as that provided by LFA-1/Mac-1 as ∼10-fold fewer neutrophils are seen to transmigrate early in the inflammatory response.

Intravital microscopy studies have identified previously a key role for L-selectin in neutrophil rolling on inflamed endothelium 29 with integrin engagement occurring only at a later stage after leukocyte activation. Here we suggest that the two processes are integrated, with LFA-1 acting earlier in the process, performing the task of providing stability to the selectin tether and slowing the velocity of the rolling neutrophil. Klaus Ley and colleagues 30 have suggested that this is a progressive event with increasing numbers of integrins engaged over time leading to leukocyte arrest and firm adhesion. In summary, the findings of this study indicate that the receptor repertoire controlling neutrophil rolling interactions with the inflamed endothelium is broader than considered previously 1 and includes LFA-1 and the α4β1 integrins, further blurring the distinctions in function between the different classes of adhesion receptors.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues Caetano Reis e Sousa, Mike Owen, Josie Hobbs, Matthew Robinson, and Kiki Tanousis for their very helpful comments on this manuscript. We are grateful to Gill Hutchinson and Julie Bee for their expert technical assistance and Dave Ferguson for his help with the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

R.B. Henderson and L.H.K. Lim contributed equally to this work.

References

- Albelda S.M., Smith C.W., Ward P.A. Adhesion molecules and inflammatory injury. FASEB J. 1994;8:504–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston B., Kubes P. The α4-integrinan alternative pathway for neutrophil recruitment? Immunol. Today. 1999;20:545–550. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01544-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J.X., Issekutz A.C. Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) is the predominant β2 (CD18) integrin mediating human neutrophil migration through synovial and dermal fibroblast barriers. Immunology. 1996;88:463–470. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibbotson G.C., Doig C., Kaur J., Gill V., Ostrovsky L., Fairhead T., Kubes P. Functional α4-integrina newly identified pathway of neutrophil recruitment in critically ill septic patients. Nat. Med. 2001;7:465–470. doi: 10.1038/86539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter J., James T.J., Howat D., Shock A., Andrew D., De Baetselier P., Blackford J., Wilkinson J.M., Higgs G., Hughes B. The in vivo and in vitro effects of antibodies against rabbit β2-integrins. J. Immunol. 1994;153:3724–3733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issekutz A.C., Issekutz T.B. The contribution of LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18) and MAC-1 (CD11b/CD18) to the in vivo migration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes to inflammatory reactions in the rat. Immunology. 1992;76:655–661. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley K., Tedder T.F. Leukocyte interactions with vascular endothelium. New insights into selectin-mediated attachment and rolling. J. Immunol. 1995;155:525–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plow E.F., Zhang L. A MAC-1 attackintegrin functions directly challenged in knockout mice. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:1145–1146. doi: 10.1172/JCI119267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen H., Gordon S. Monoclonal antibody to the murine type 3 complement receptor inhibits adhesion of myelomonocytic cells in vitro and inflammatory cell recruitment in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 1987;166:1685–1701. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.6.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H., Smith C.W., Perrard J., Bullard D., Tang L., Shappell S.B., Entman M.L., Beaudet A.L., Ballantyne C.M. LFA-1 is sufficient in mediating neutrophil emigration in Mac-1-deficient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:1340–1350. doi: 10.1172/JCI119293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmits R., Kundig T.M., Baker D.M., Shumaker G., Simard J.J., Duncan G., Wakeham A., Shahinian A., van der Heiden A., Bachmann M.F. LFA-1–deficient mice show normal CTL responses to virus but fail to reject immunogenic tumor. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:1415–1426. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew D.P., Spellberg J.P., Takimoto H., Schmits R., Mak T.W., Zukowski M.M. Transendothelial migration and trafficking of leukocytes in LFA-1-deficient mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 1998;28:1959–1969. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199806)28:06<1959::AID-IMMU1959>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coxon A., Rieu P., Barkalow F.J., Askari S., Sharpe A.H., von Andrian U.H., Arnaout M.A., Mayadas T.N. A novel role for the β2 integrin CD11b/CD18 in neutrophil apoptosisa homeostatic mechanism in inflammation. Immunity. 1996;5:653–666. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z.M., Babensee J.E., Simon S.I., Lu H., Perrard J.L., Bullard D.C., Dai X.Y., Bromley S.K., Dustin M.L., Entman M.L. Relative contribution of LFA-1 and Mac-1 to neutrophil adhesion and migration. J. Immunol. 1999;163:5029–5038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizgerd J.P., Kubo H., Kutkoski G.J., Bhagwan S.D., Scharffetter-Kochanek K., Beaudet A.L., Doerschuk C.M. Neutrophil emigration in the skin, lungs, and peritoneumdifferent requirements for CD11/CD18 revealed by CD18-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:1357–1364. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin-Rufenach C., Otto F., Mathies M., Westermann J., Owen M.J., Hamann A., Hogg N. Lymphocyte migration in lymphocyte function-associated antigen (LFA)-1–deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:1467–1478. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.9.1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim L.H., Solito E., Russo-Marie F., Flower R.J., Perretti M. Promoting detachment of neutrophils adherent to murine postcapillary venules to control inflammationeffect of lipocortin 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:14535–14539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund-Johansen F., Terstappen L.W. Differential surface expression of cell adhesion molecules during granulocyte maturation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1993;54:47–55. doi: 10.1002/jlb.54.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeber D.A., Campbell M.A., Basit A., Ley K., Tedder T.F. Optimal selectin-mediated rolling of leukocytes during inflammation in vivo requires intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:7562–7567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigal A., Bleijs D.A., Grabovsky V., van Vliet S.J., Dwir O., Figdor C.G., van Kooyk Y., Alon R. The LFA-1 integrin supports rolling adhesions on ICAM-1 under physiological shear flow in a permissive cellular environment. J. Immunol. 2000;165:442–452. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knorr R., Dustin M.L. The lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 I domain is a transient binding module for intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 and ICAM-3 in hydrodynamic flow. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:719–730. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.5.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin C., Bargatze R.F., Campbell J.J., von Andrian U.H., Szabo M.C., Hasslen S.R., Nelson R.D., Berg E.L., Erlandsen S.L., Butcher E.C. α4 integrins mediate lymphocyte attachment and rolling under physiologic flow. Cell. 1995;80:413–422. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90491-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriramarao P., von Andrian U.H., Butcher E.C., Bourdon M.A., Broide D.H. L-selectin and very late antigen-4 integrin promote eosinophil rolling at physiological shear rates in vivo. J. Immunol. 1994;153:4238–4246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazo I.B., Gutierrez-Ramos J.C., Frenette P.S., Hynes R.O., Wagner D.D., von Andrian U.H. Hematopoietic progenitor cell rolling in bone marrow microvesselsparallel contributions by endothelial selectins and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1. J. Exp. Med. 1998;188:465–474. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.3.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabovsky V., Feigelson S., Chen C., Bleijs D.A., Peled A., Cinamon G., Baleux F., Arenzana-Seisdedos F., Lapidot T., van Kooyk Y. Subsecond induction of α4 integrin clustering by immobilized chemokines stimulates leukocyte tethering and rolling on endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 under flow conditions. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:495–506. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt P.H., Elliott J.F., Kubes P. Neutrophils can adhere via α4β1-integrin under flow conditions. Blood. 1997;89:3837–3846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neelamegham S., Taylor A.D., Burns A.R., Smith C.W., Simon S.I. Hydrodynamic shear shows distinct roles for LFA-1 and Mac-1 in neutrophil adhesion to intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Blood. 1998;92:1626–1638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentzen E.R., Neelamegham S., Kansas G.S., Benanti J.A., McIntire L.V., Smith C.W., Simon S.I. Sequential binding of CD11a/CD18 and CD11b/CD18 defines neutrophil capture and stable adhesion to intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Blood. 2000;95:911–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Andrian U.H., Hansell P., Chambers J.D., Berger E.M., Torres Filho I., Butcher E.C., Arfors K.E. L-selectin function is required for β2-integrin-mediated neutrophil adhesion at physiological shear rates in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;263:H1034–H1044. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.4.H1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel E.J., Dunne J.L., Ley K. Leukocyte arrest during cytokine-dependent inflammation in vivo. J. Immunol. 2000;164:3301–3308. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]