Abstract

The contribution of accessory toxins to the acute inflammatory response to Vibrio cholerae was assessed in a murine pulmonary model. Intranasal administration of an El Tor O1 V. cholerae strain deleted of cholera toxin genes (ctxAB) caused diffuse pneumonia characterized by infiltration of PMNs, tissue damage, and hemorrhage. By contrast, the ctxAB mutant with an additional deletion in the actin-cross-linking repeats-in-toxin (RTX) toxin gene (rtxA) caused a less severe pathology and decreased serum levels of proinflammatory molecules interleukin (IL)-6 and murine macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-2. These data suggest that the RTX toxin contributes to the severity of acute inflammatory responses. Deletions within the genes for either hemagglutinin/protease (hapA) or hemolysin (hlyA) did not significantly affect virulence in this model. Compound deletion of ctxAB, hlyA, hapA, and rtxA created strain KFV101, which colonized the lung but induced pulmonary disease with limited inflammation and significantly reduced serum titers of IL-6 and MIP-2. 100% of mice inoculated with KFV101 survive, compared with 20% of mice inoculated with the ctxAB mutant. Thus, the reduced virulence of KFV101 makes it a prototype for multi-toxin deleted vaccine strains that could be used for protection against V. cholerae without the adverse effects of the accessory cholera toxins.

Keywords: Vibrio cholerae, inflammation, RTX toxin, hemolysin, hemagglutinin/protease

Introduction

Vibrio cholerae is the classic example of a noninvasive enteric pathogen that induces a highly secretory diarrhea in the absence of an inflammatory response (1, 2). Of diagnostic and clinical significance, there is a paucity of anatomic pathology in the intestines of patients with cholera (3). Indeed, death of cholera victims is primarily caused by secondary dehydration due to massive intestinal fluid loss, not intestinal damage or septicemia. The virulence factor predominantly responsible for this watery diarrhea is cholera toxin (CT),* a powerful enterotoxin encoded by the ctxA and ctxB genes carried on the transmissible prophage CTXΦ (4, 5).

“Nontoxigenic” variants of V. cholerae that do not carry the integrated CTXΦ prophage also cause disease, including sporadic outbreaks of watery diarrhea and isolated incidences of extraintestinal infections, septicemia, and inflammatory enterocolitis (2, 6–8). In clinical trials of live attenuated vaccine strains, it was shown that lactoferrin, a physiological marker for the presence of neutrophils, was present at higher titers in the stool of human volunteers given the CT-deficient vaccine strain compared with volunteers given the CT-producing control strains (9). These results suggest that V. cholerae strains that do not produce CT induce a more inflammatory diarrhea, rather than the noninflammatory disease associated with CT-producing strains.

The development of inflammatory diarrhea in the absence of CT may be due to loss of immunomodulatory signaling by CT (10). CT has been shown in vitro to block production of proinflammatory cytokines TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-12 by LPS-stimulated monocytes and dendritic cells (11, 12). Thus, in addition to stimulating fluid secretion through activation of adenylate cyclase activity (4), CT suppresses induction of inflammation during V. cholerae infection.

In vitro studies have identified cytotoxic factors other than CT secreted by V. cholerae that may cause tissue damage that, in turn, could contribute to induction of proinflammatory responses. These “accessory toxins” of V. cholerae include the repeats-in-toxin (RTX) toxin, which causes cell rounding and increased permeability through paracellular tight junctions due to covalent cross-linking of actin monomers leading to depolymerization of actin stress fibers (13–15); hemagglutinin/protease (HAP), which degrades occludin in paracellular tight junctions leading to separation of paracellular tight junctions and desquamation of tissue (16–20); and, hemolysin, which causes necrosis of intestinal epithelial cells, growth of mildly acidic vacuoles, and hemolysis depending upon the cell type and toxin concentration (21–27). The contribution of these cytotoxins to the stimulation of the proinflammatory response in vivo has not been previously examined, in part due to insufficient animal models for such studies.

Although studies using infant mice and adult rabbits are well documented, V. cholerae is rapidly cleared from the intestine of adult mice (28, 29). Hence, in vivo studies of the acute immunobiological responses to V. cholerae infection have not been feasible. Studies of Shigella flexneri, the causative agent of bacillary dysentery, have been similarly hampered by the lack of a mouse intestinal infection model. Surprisingly, the mouse lung was shown to be a suitable substitute for evaluation of local and systemic immune responses to S. flexneri challenge (30–32). This model is based on the premise that the bronchial tree is composed of a mucosal lining with relevant characteristics similar to the intestine including simple cubodial to columnar epithelial cells, lymphoid aggregates (bronchiole associated lymphoid tissue [BALT]) similar to Peyer's patches, and the presence of several varieties of antigen-presenting cells (32).

Using this murine pulmonary model for dysentery, V. cholerae was tested for its ability to cause disease when inoculated intranasally. A CT-negative strain of V. cholerae was found to be highly infectious to the pulmonary system leading to a diffuse pneumonia. The production of proinflammatory signal molecules IL-6 and murine macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2) and the severity of disease correlated with the specific repertoire of extracellular toxins expressed by the infecting V. cholerae strain.

Materials and Methods

Construction of Plasmids pCWΔrtxA and pCWΔhlyA.

Gene sequences upstream of rtxA and 87 bp of rtxA was amplified from V. cholerae El Tor N16961 by PCR using primers 3399 (5′-CGATTACCGCTGATGATACTTAA) and 4319B (5′-AGTGACTCGAATGGCTACAATGTTGTTGTTTCC). The amplified product was cloned into pCR2.1 using the TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). The insert was then excised by EcoRI digestion and moved into the EcoRI site of pWL80, which has the 3.8-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment of rtxA cloned in pBluescriptII (14). The resulting gene fusion removed codons for amino acid (aa) 30 to aa 2634 from the rtxA gene with sufficient flanking sequences for recombination. The fused gene was moved to the polylinker of sucrose counter-selectable plasmid pWM91 (33) to create pCWΔrtxA.

A 3.3-kb DNA segment including the entire hlyA gene and flanking DNA was amplified from N16961 by PCR using primers hlyA6215 (5′-TTTCTTGCAGTAGCATCATATCGATA) and hlyA2980 (5′-AATCTGTGATCCGCTGTGAATTTTCAA). The amplified product was cloned into pCR2.1 using the TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). The resulting plasmid was digested with NruI and SnaBI and was relegated to delete codons for aa 8 to 595 of the hlyA gene. The resulting ΔhlyA fragment was moved to the polylinker of sucrose counter-selectable plasmid pWM91 (33) to create pCWΔhlyA.

Bacterial Strains.

All strains are derived from the streptomycin-resistant isolate of the V. cholerae O1 El Tor Inaba strain P27459, originally isolated in Bangladesh in 1979 (34). V. cholerae P4 (a.k.a. SM44) has an engineered mutation replacing the ctxA and ctxB genes on the integrated CTXΦ prophage in P27459 with a gene for kanamycin resistance (35). P4 was further genetically engineered to generate unmarked internal deletions in the genes for the RTX toxin (rtxA), HAP (hapA), and hemolysin (hlyA). Protocols for sacB-counterselection in V. cholerae has been described previously (36). Briefly, plasmids pCWΔrtxA (this study), pCWΔhlyA (this study), and pCVDΔhapSal (36) were transferred to P4 by conjugation from SM10λpir and cointegrants were selected by growth on kanamycin and ampicillin. Loss of the sacB gene due to resolution of the cointegrant in the absence of antibiotic selection was selected on 6% sucrose plates. Reversion to either wild-type or deleted gene arrangements were distinguished by PCR analysis and by assaying for loss of cell rounding, proteolytic, or hemolytic activities.

Inoculation of Mouse Lungs.

Prior to inoculation into mice, bacterial cultures were grown in 5 ml Luria broth with 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 50 μg/ml kanamycin at 30°C overnight with shaking. The bacteria were pelleted, washed twice with PBS, and adjusted to the desired CFU/ml based on empirical observation that an A600 of 0.5 contains 109 CFU V. cholerae per ml. The actual CFU/ml was determined by plating dilutions of the inocula.

All animal procedures were performed as directed by ACUC approved protocols at Harvard Medical School or Northwestern University Medical School. 5–7-wk-old female specific pathogen free BALB/c mice (Taconic or Harlan Laboratories) were injected intraperitoneal with 6 mg/kg ketamine and 1.25 mg/kg xylazine combined in 50 μl PBS. When the mice were anesthetized, 20 μl PBS (mock infection) or 20 μl of bacterial suspension was delivered by pipette to the left external nares. The mouse was held upright for 30–60 s after inoculation to assure aspiration. Inoculation groups were staggered by 1 h to enable processing of all animals at ∼24 h after infection.

Physical Examination.

Mice were examined before euthanasia for clinical signs of disease and were scored on a scale of 1 (worst) to 5 (best) for scruffiness (1 = not groomed; 5 = clean fur), mobility (1 = sitting upright and won't move even when prodded; 5 = normal, active and eating), ocular character (1 = both eyes closed, 5 = normal, both eyes open and bright), breath rate (1 = slow and labored; 5 = normal rapid, shallow breaths), and appearance of lung after removal (1 = both lobes red and hemorrhagic, 5 = pink and healthy). The total health rating is the mean of the scores for the five criteria.

Euthanasia and Collection of Tissues.

At 24 h after infection, mice were killed by CO2 asphyxiation and then exsanguinated by cardiac puncture. The lungs and heart were removed with the trachea intact. One lobe of the lung was clamped at the bronchial bifurcation and the caudate lobe was removed. The remaining lobe was injected with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS through a needle inserted into the trachea.

Bacterial Colonization and Quantification of TNFα, IL-6, and MIP-2.

The excised caudate lobe of lung was weighed and then homogenized in 5 ml Luria broth using an electric tissue tearor. The homogenate was serially diluted and plated for V. cholerae CFU counts. 1 ml of the undiluted homogenate was frozen on dry ice and stored at –80°C. Blood collected by cardiac puncture was set at room temperature for 2 h to allow blood to clot. The serum was separated by centrifugation at 4,000 g, removed from clot, and stored at –20°C. The concentrations of TNFα in the undiluted lung homogenate and the serum titer of IL-6 and MIP-2 were determined by ELISA (R&D Systems).

Histopathology.

Lungs preserved in paraformaldehyde were embedded, sliced, mounted, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H/E) at the Histology Core Facility of Beth Israel Deaconness Hospital (Boston, MA). Slides were scored by a veterinary pathologist on a scale of 0 (no lesion) to 4 (severe) for degree of pneumonia, degree of histopathology to the large airways and alveoli, presence or absence of PMNs, macrophages, and type II pneumocytes, and degree of perivascular edema. The composite score is the sum of values for the seven criteria (maximum 28).

Data Analysis.

Mice that died before 24 h of infection were eliminated from further analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using the Microsoft Excel Data Analysis Package t test assuming unequal variances. P values < 0.05 were determined to be statistically significant.

Results

Analysis of P4 (ctxAB::km) in a Mouse Model.

As an initial test of the murine pulmonary cholera model, five mice were inoculated intranasally with a sublethal dosage of V. cholerae El Tor O1 strain P4, a derivative of the clinical isolate P27459 with a kanamycin-cassette replacing ctxA and ctxB to eliminate production of CT (35). Three mice were given 20 μl PBS as a sham infection control. After 24 h, the mice were killed and evaluated (Table I and Fig. 1) .

Table I.

Initial Demonstration of Colonization and Stimulation of Proinflammatory Cytokines and Chemokines after Intranasal Infection of Mice with Nontoxigenic V. cholerae

| P4 (ctxAB::km) | Sham treated | |

|---|---|---|

| Initial inoculum | 2.3 × 107

CFU in 20 μl |

20 μl PBS buffer |

| Mice surviving to 24 h | 4/4 | 3/3 |

| CFU recovered from lung | 2,300–23,300 CFU/100 mg |

0 |

| Health rating | 1.9 ± 0.5a | 5.0 ± 0.0 |

| Severity of pneumonia | 13.5 ± 4.4a | 2.0 ± 3.5 |

| TNFα (pg/100 mg lung) | 1,000 ± 520 (range 570–1,800)a |

<25 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml serum) | 3,400 ± 2,700 (range 830–6,600)a |

<37 |

| MIP-2 (pg/ml serum) | 2,100 ± 2,600 (range 230–5,032)a |

<120 |

Significantly different from sham-treated mice at P < 0.05.

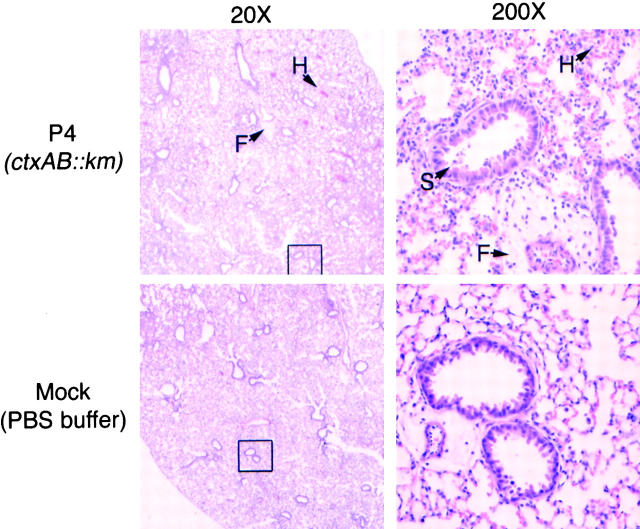

Figure 1.

V. cholerae induced pneumonia in BALB/c mice. H/E staining of lung sections from mice inoculated with P4 (top) or with control buffer (bottom). Figures at right are at 10× magnification of boxed section at the left. Notable features are marked including fibrin (F), hemorrhage (H), and epithelial cell sloughing (S).

The V. cholerae P4-inoculated mice exhibited decreased activity, ocular discharge, malaise, heavy and labored breathing, and ungroomed hair coat resulting in a low overall health score. The lungs were mottled and dark red and V. cholerae was culturable from the lung tissue. TNFα was released to the local tissue and serum concentrations of IL-6 and MIP-2 were elevated. Histologic examination of the lungs revealed moderate diffuse or multifocal bronchiolar and alveolar pneumonia (Fig. 1). The predominant inflammatory cells present were PMNs with some activated alveolar macrophages. In addition to the bronchiolar pneumonia, the lungs showed evidence of alveolar hemorrhage, septal necrosis, accumulation of fibrous proteinaceous material suspected to be eosinophilic fibrin, and moderate to severe perivascular edema. Examination of the bronchiolar epithelial lining demonstrated sloughing indicative of injury and death of the epithelial barrier of the large airways. The cytoplasm:nuclear ratio of these cells was altered suggesting action of cytotoxins on these cells.

These observations are contrasted to those of the sham-treated mice, which were physically active with normal health scores. The levels of TNFα, IL-6, and MIP-2 were below detection limits (Table I). The pulmonary histology did show some debris and slight focal hemorrhage, most likely due to aspiration of PBS under anesthesia (Fig. 1).

These data demonstrate that V. cholerae can colonize the lungs of adult immunocompetent mice and cause histologic changes to the epithelial surfaces. The infection is inflammatory in nature as evidence by the influx of PMNs and stimulation of proinflammatory molecules.

Comparison of Strains Deleted in Accessory Toxin Genes.

In a second series of experiments, the affect of accessory toxins to the development of inflammation was assessed compared with the ctxAB mutant strain P4 and sham-inoculated controls (Table II and Fig. 2) .

Table II.

Contribution of Accessory Toxins to Stimulation of Proinflammatory Molecules and Pathogenesis

| Sham treated |

P4 (ctxAB::km) |

KFV105 (P4ΔrtxA) |

KFV70 (P4ΔhapA) |

KFV103 (P4ΔhlyA) |

KFV101 (P4ΔhapAΔhlyAΔrtxA) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial inoculum (in 20 μl) | PBS buffer | 4.7 × 107 | 3.8 × 107 | 3.8 × 107 | 4.2 × 107 | 4.0 × 107 |

| Mice surviving to 24 h | 3/3 | 4/7 | 4/4 | 2/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| CFU recovered/100 mg lung (range × 103) |

0 | 7.9–37 | 2.7–110 | 9.2–71 | 4.5–5,560 | 1.5–220 |

| Health rating (scale 1 to 5) | 4.7 ± 0.5a | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.6a | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 4.0 ± 0.4a , b |

| Severity of pneumonia (scale 0 to 28) |

2.0 ± 1.7a | 13.0 ± 2.0 | 13.7 ± 2.5 | 16.0 ± 0.0 | 15.0 ± 3.2 | 16.8 ± 4.0 |

| TNFα (pg/100 mg lung) | <25 | 1,100 ± 600 | 940 ± 50 | 760 ± 210 | 1,100 ± 820 | 930 ± 190 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml serum) | <37 | 7,000 ± 4,500 | 730 ± 200a | 4,500 ± 4,200 | 2,600c | 250 ± 160a , b |

| MIP-2 (pg/ml serum) | <120 | range 2,400–64,000 |

range 230–1,200a |

range 63,00–70,00 |

range 2,300–25,000 |

<120a , b |

Value is significantly different from value for P4 (P < 0.05).

Value is significantly different from value for KFV105 (P < 0.05).

IL-6 assayed for only one mouse as other samples were insufficient after MIP-2 test.

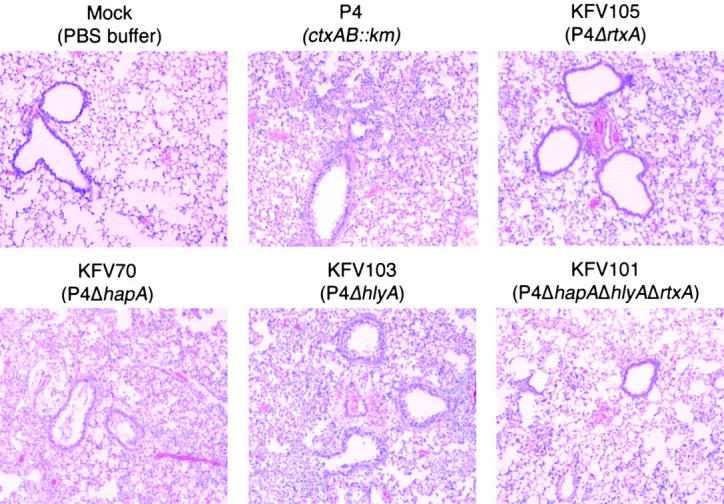

Figure 2.

Loss of specific cytotoxins affects acute pathology of pulmonary disease. Lung sections from mice intranasally inoculated with P4 and four isogenic mutants were selected for areas demonstrating epithelial lined bronchioles and alveolar air spaces. Note increase numbers of inflammatory cells in the alveoli of the exposed tissue of KFV70 (ΔhapA) KFV103 (ΔhlyA), when compared with the KFV105 (ΔrtxA), KFV101 (ΔhapA, ΔhlyA, ΔrtxA), and sham-treated samples (H/E, 100×).

Four mice were inoculated with KFV105, a derivative of P4 bearing an in-frame deletion that removes 7.8 kb of the rtxA gene and eliminates the RTX toxin-associated cell rounding activity. By comparison to P4, infection of mice with KFV105 resulted in a significantly improved clinical score and decreased serum titers of IL-6 and MIP-2. The CFU of KFV105 recovered from the lung was slightly lower than for P4 suggesting a minor defect in colonization or more rapid clearance by the immune system; however, differences in the CFU recovered were not statistically significant (P = 0.22). The pathology of the lung showed a moderate, multi-focal pneumonia, rather than the severe, diffuse pneumonia observed for the P4-infected mice. However, the overall severity score increased slightly due to more evidence of perivascular edema and recruitment of macrophages and type II pneumocytes. Thus, loss of the RTX toxin rendered V. cholerae less pathogenic, but not avirulent or noninflammatory, in this mouse model.

Four mice were inoculated with a derivative of P4 bearing an internal deletion in the gene for HAP. Among all the deletion mutants tested, this is the only group in which all four mice failed to survive to 24 h. The remaining two mice were in poor health with very high titers of IL-6 and MIP-2 and an overall severity score that exceeded that observed for P4. In particular, injury to cells lining the large airway is more severe than noted for P4-infected mice. These data suggest that loss of this protease may have altered the course of infection to be more lethal, although none of the measured values were significantly different from the P4 group, in part due to lack of samples.

Four mice were inoculated with a derivative of P4 bearing an internal deletion in the gene for hemolysin. Mice in this group were heavily colonized and in poor health at 24 h. Sampling of blood and testing of serum from this group was difficult as the blood was often thickened. Evaluation of the lung pathology revealed a dense pneumonia characterized by consolidation, pleuritis, and sloughing in the major airways indicative of a more severe pneumonia as compared with the P4 control group.

These results demonstrated that the RTX toxin is the only one of the three toxins that significantly contributed to the enhancement of inflammation as demonstrated by improved pathology and decreased titers of proinflammatory molecules MIP-2 and IL-6 when the rtxA gene is deleted. The apparent worsening of pathology due to deletion of hapA or hlyA may reflect antiinflammatory action by these toxins or an alteration in the delivery of other toxins to specific tissues and thus a loss of the coordinated modulation of the immune system.

A Multi-toxin Mutant Has Significantly Decreased Virulence.

The additive effects of these toxins to disease was demonstrated by an improved health score and decreased serum titers of IL-6 and MIP-2 when a multi-toxin mutant strain KFV101, with deletions in ctxAB, rtxA, hapA, and hlyA, was assessed. These data are statistically significant when compared with P4 and to other mutants deleted of any single toxin, most notably the rtxA deletion KFV105 (Table II and Fig. 2).

The lungs of these mice were relatively clear compared with other samples although this is not reflected in the severity score. A breakdown of the severity score revealed that the increase in score is due primarily to high values for PMNs in alveolar spaces and type II pneumocytes suggesting that the immune systems in these mice are responding to the infection before the onset of dense pneumonia.

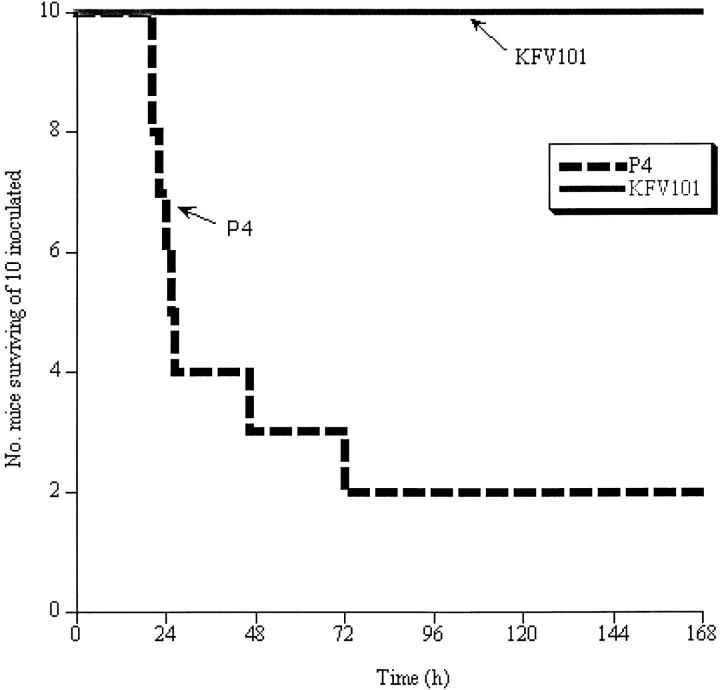

The overall improvement in the pathology suggested that mice infected with the multi-toxin mutant might successfully clear the infection and survive the bacterial challenge. To test this, 10 mice were inoculated with either P4 or KFV101 and the mice were monitored for seven days. 80% of mice in the P4 group died within 3 d, while all 10 mice inoculated with KFV101 survived 7 d (Fig. 3) . The KFV101-infected mice originally showed signs of infection but gradually returned to normal activity after 1 to 2 d. Most strikingly, the two survivors challenged with P4 showed weight loss to an average of 12.1 g (or a loss of ∼33% body weight) while the KFV101 survivors maintained a weight of 18–20 g. These data show that mice can survive a challenge of KFV101 that is lethal when the extracellular toxins are produced.

Figure 3.

Mice challenge with multi-toxin deleted strain KFV101 survive. 10 mice were inoculated with either 2 × 107 P4 (dashed line) or KFV101 (solid line) and mice were followed for 7 d. The time of death was noted for each mouse as indicated in graph. Surviving mice were killed after 7 d.

Dissemination of Disease.

The magnitude of hemorrhage and the diffuse nature of the pneumonia in P4-infected mice suggest that bacteria may have transversed the epithelial barriers and invaded adjacent tissues. To test this possibility, a total of nine mice each were infected with either P4 or KFV101 in two different experiments, one terminated at 24 h and the other at 18 h. Of six survivors in the P4 group, five had disseminated infections as indicated by recovery of kanamycin and streptomycin resistant V. cholerae from the liver and spleen. By contrast, KFV101 never led to a disseminated infection in the first two experiments. An additional seven mice were inoculated with a fivefold higher dose of KFV101 and dissemination was charted. Of five mice that were colonized in the lung at 24 h, four developed disseminated infections. Thus, the accessory toxins may contribute to septicemia at lower dosages but they are not absolutely essential for dissemination.

Discussion

Innate immune responses to V. cholerae infection have not been intensely studied in part due to the absence of a murine model for pathogenesis. The suckling mouse model has proven useful for the study of bacterial colonization and regulation of virulence factors (37). However, these 5–6-d-old mice do not have immune systems sufficiently developed for study of immunomodulation. Adult germ-free mouse models have been useful for evaluation of immunogenic potential of oral V. cholerae vaccine strains even though colonization may not occur (38), yet neither of these models is applicable for study of acute inflammatory responses. In this study, we report the use of a novel mouse model conceptually adapted from the studies of S. flexneri (30–32) and technically based on previous studies with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (39). We have demonstrated that V. cholerae can infect the lung of BALB/c mice leading to the development of inflammation.

The identity of the “reactogenicity factor” of V. cholerae vaccine strains has been elusive. Indeed, determination of this factor was identified by the National Institute of Health in 1996 as one of the top priorities for enteric disease research (40) and improvement of available vaccines has been recommended by the World Health Organization (41). Using this in vivo model, we suggest that the “reactogenicity” factor is likely a trio of factors consisting of HAP, hemolysin, and the RTX toxin. Genetic manipulation resulting in the loss of these cytotoxins led to a change of the course of the disease, particularly in the pathology. Most prominently, these studies revealed that the RTX toxin is a key factor in the stimulation of the proinflammatory mediators IL-6 and MIP-2. Although compound deletion of rtxA and ctxAB did not generate an avirulent strain, the decrease in serum levels of IL-6 and MIP-2 and improvement in the clinical signs of disease compared with the single ctxAB deletion strain are the first observations linking the RTX toxin to pathogenesis in vivo. By contrast, histopathologic evidence indicates that V. cholerae strains deleted of hlyA or hapA in addition to deletion of ctxAB are potentially more virulent than the parent strain. Conversely, absence of these toxins in addition to the RTX toxin led to improved pathology and decreased serum titers of IL-6 and MIP-2 suggesting these toxin somehow work in concert.

These results predict that deletion of the genes for a single accessory toxin would not subvert cholera vaccine reactogenicity. This prediction is supported by results from human vaccine trials. Double mutants lacking ctx genes in combination with hlyA (42), hapA (43), or rtxA (44) have been tested in phase I vaccine trials and each double mutant retained some virulence. The data presented here on KFV101, deleted of ctxAB, hlyA, hapA, and rtxA, would suggest that the use of a multi-toxin knockout vaccine strain might prevent the clinical side effects of the current candidate vaccine strains.

It is notable that the strain P4 is frequently used as a source of kanamycin-resistant CTXΦ phage particles indicating it produces the CTXΦ phage assembly proteins Zot and Ace, which have also been proposed as accessory toxins that could contribute to reactogenicity. In a separate experiment, Bang-1, a CTXΦ core deletion strain derived from P27459 (45), was found to have no significant difference in the course of disease compared with P4 suggesting that loss of the proteins Zot and Ace does not reduce or increase virulence of V. cholerae in this model.

The combination of in vitro and in vivo results would suggest that the enhancement of the proinflammatory response by these accessory toxins is due to increased tissue damage when the toxin are expressed. However, further experimentation is required to characterize the mouse pulmonary model of cholera and to more thoroughly investigate the roles of the RTX toxin, HAP, and hemolysin in pathogenesis and in the induction of the proinflammatory immune response. The advantage of this model is that it is suitable for use in studies of cholera infection in a broad range of commercially available knockout mice including mice deficient in production of IL-6, MIP-2, IL-1β, and various Toll-like and cytokine receptors implicated in the innate immune response to bacterial infections. In addition, the observations reported here suggest that this model could be applied as an initial screen for the prediction of proinflammatory potential of putative vaccine strains before initiation of more succinct studies in the well established, but more expensive, rabbit model for intestinal cholera disease or before launching phase I human clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Engman for his critical review of the manuscript.

This project was funded by National Institutes of Health grant AI018045 to J.J. Mekalanos and a Biomedical Research Support Program Award to K.J. Fullner from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. K.J. Fullner was also supported for early parts of this project by a National Institutes of Health post-doctoral fellowship AI010395 and J.C. Boucher was funded by fellowship BOUCHE01F0 from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: CT, cholera toxin; HAP, hemagglutinin/protease; H/E, hematoxylin and eosin; MIP, murine macrophage inflammatory protein; RTX, repeats-in-toxin.

References

- 1.Farthing, M.J.G. 1997. Acute diarrhea: pathophysiology. Diarrheal Disease, Vol. 38. M. Gracey and J.A. Walker-Smith, editors. Vevey/Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, PA. 55–73.

- 2.Mandell, G.L., J.E. Bennett, and R. Dolin. 1995. Principles and Practices of Infectious Diseases. Vol. 2. Churchill Livingstone, New York, NY. 2803 pp.

- 3.Sun, S.C., B.T. Schaeffer, and V.M. Reyes. 1971. Human Vibrio cholerae: a histologic review of 117 cases in the Philippines. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health. 2:73–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lencer, W.I. 2001. Microbes and microbial toxins: Paradigms for microbial-mucosal interactions: V. Cholera: invasion of the intestinal epithelial barrier by a stably folded protein toxin. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 280:G781–G786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waldor, M.K., and J.J. Mekalanos. 1996. Lysogenic conversion by a filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin. Science. 272:1910–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blake, P.A., R.E. Weaver, and D.G. Hollis. 1980. Disease of humans (other than cholera) caused by vibrios. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 34:341–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ninin, E., N. Caroff, E. Kouri, E. Espaze, H. Richet, M.L. Quilici, and J.M. Fournier. 2000. Nontoxigenic Vibrio cholerae O1 bacteremia: case report and review. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19:488–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathan, M.M., G. Chandy, and V.I. Mathan. 1995. Ultrastructural changes in the upper small intestinal mucosa in patients with cholera. Gastroenterology. 109:422–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silva, T.M.J., M.A. Schuleupner, C.O. Tacket, T.S. Steiner, J.B. Kaper, R. Edelman, and R.L. Guerrant. 1996. New evidence for an inflammatory component in diarrhea caused by selected new, live attenuated cholerae vaccines and by El Tor and O139 Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 64:2362–2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams, N.A., T.R. Hirst, and T.O. Nashar. 1999. Immune modulation by the cholera-like enterotoxins: from adjuvant to therapeutic. Immunol. Today. 20:95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cong, Y., A.O. Oliver, and C.O. Elson. 2001. Effects of cholera toxin on macrophage production of co-stimulatory cytokines. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gagliardi, M.C., F. Sallusto, M. Marinaro, A. Langenkamp, A. Lanzavecchia, and M.T. De Magistris. 2000. Cholera toxin induces maturation of human dendritic cells and licences them for Th2 priming. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:2394–2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fullner, K.J., W.I. Lencer, and J.J. Mekalanos. 2001. Vibrio cholerae-induced cellular responses of polarized T84 intestinal epithelial cells dependent of production of cholera toxin and the RTX toxin. Infect. Immun. 69:6310–6317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin, W., K.J. Fullner, R. Clayton, J.A. Sexton, M.B. Rogers, K.E. Calia, S.B. Calderwood, C. Fraser, and J.J. Mekalanos. 1999. Identification of a Vibrio cholerae RTX toxin gene cluster that is tightly linked to the cholera toxin prophage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:1071–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fullner, K.J., and J.J. Mekalanos. 2000. In vivo covalent crosslinking of actin by the RTX toxin of Vibrio cholerae. EMBO J. 19:5315–5323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burnet, F.M. 1949. Ovomucin as a substrate for the mucinolytic enzymes of V. cholerae filtrates. Aust. J. Exp. Biol. Med. Sci. 27:245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finkelstein, R.A., M. Boesman-Finkelstein, and P. Holt. 1983. Vibrio cholerae hemagglutinin/lectin/protease hydrolyzes fibronectin and ovomucin: F.M. Burnet revisited. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 80:1092–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mel, S.F., K.J. Fullner, S. Wimer-Mackin, W.I. Lencer, and J.J. Mekalanos. 2000. Association of protease activity in Vibrio cholerae vaccine strains with decreases in transcellular epithelial resistance of polarized T84 intestinal cells. Infect. Immun. 68:6487–6492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu, Z., P. Nybom, T. Sudqvist, and K.-E. Magnusson. 1998. Endogenous nitric oxide in MDCK-I cells modulates the Vibrio cholerae haemagglutinin/protease (HA/P)-mediated cytoxicity. Microb. Pathog. 24:321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu, Z., P. Nybom, and K.-E. Magnusson. 2000. Distinct effects of the Vibrio cholerae haemagglutinin/protease on the structure and localization of the tight junction-associated proteins occludin and ZO-1. Cell. Microbiol. 2:11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alm, R.A., G. Mayrhofer, I. Kotlarski, and P.A. Manning. 1991. Amino-terminal domain of the El Tor haemolysin of Vibrio cholerae O1 is expressed in classical strains and is cytotoxic. Vaccine. 9:588–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coelho, A., J.R.C. Andrade, A.C.P. Vicente, and V.J. DiRita. 2000. Cytotoxic cell vacuolating activity from Vibrio cholerae hemolysin. Infect. Immun. 68:1700–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Figueroa-Arredondo, P., J.E. Heuser, N.S. Akopyants, J.H. Morisaki, S. Giono-Cerezo, F. Enriquez-Rincon, and D.E. Berg. 2001. Cell vacuolation caused by Vibrio cholerae hemolysin. Infect. Immun. 69:1613–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldberg, S.L., and J.R. Murphy. 1984. Molecular cloning of the hemolysin determinant from Vibrio cholerae El Tor. J. Bacteriol. 160:239–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manning, P.A., M.H. Brown, and M.W. Heuzenroeder. 1984. Cloning of the structural gene (hly) for the haemolysin of Vibrio cholerae El Tor strain 017. Gene. 31:225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitra, R., P. Figueroa, A.K. Mukhopadhyay, T. Shimada, Y. Takeda, D.E. Berg, and G.B. Nair. 2000. Cell vacuolation, a manifestation of the El Tor hemolysin of Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 68:1928–1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zitzer, A., T.M. Wassenaar, I. Walev, and S. Bhakdi. 1997. Potent membrane-permeabilizing and cytocidal action of Vibrio cholerae cytolysin on human intestinal cells. Infect. Immun. 65:1293–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knop, J., and D. Rowley. 1975. Antibacterial mechanisms in the intestine. Elimination of V. cholerae from the gastrointestinal tract of adult mice. Aust. J. Exp. Biol. Med. Sci. 53:137–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knop, J., and D. Rowley. 1975. Protection against cholera. A bactericidal mechanism on the mucosal surface of the small intestine of mice. Aust. J. Exp. Biol. Med. Sci. 53:155–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phalipon, A., M. Kaufmann, P. Michetti, J.M. Cavaillon, M. Huerre, P. Sansonetti, and J.P. Kraehenbuhl. 1995. Monoclonal immunoglobulin A antibody directed against serotype-specific epitope of Shigella flexneri lipopolysaccharide protects against murine experimental shigellosis. J. Exp. Med. 182:769–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sansonetti, P.J., A. Phalipon, J. Arondel, K. Thirumalai, S. Banerjee, S. Akira, K. Takeda, and A. Zychlinsky. 2000. Caspase-1 activation of IL-1β and IL-18 are essential for Shigella flexneri-induced inflammation. Immunity. 12:581–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van de Verg, L.L., C.P. Mallett, H.H. Collins, T. Larsen, C. Hammack, and T.L. Hale. 1995. Antibody and cytokine responses in a mouse pulmonary model of Shigella flexneri serotype 2a infection. Infect. Immun. 63:1947–1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Metcalf, W.M., W. Jiang, L.L. Daniels, S.-K. Kim, A. Haldimann, and B.L. Wanner. 1996. Conditionally replicative and conjugative plasmids carrying lacZα for cloning, mutagenesis, and allele replacement in bacteria. Plasmid. 35:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mekalanos, J.J. 1983. Duplication and amplification of toxin genes in Vibrio cholerae Cell. 35:271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldberg, I., and J.J. Mekalanos. 1986. Cloning of the Vibrio cholerae recA gene and construction of a Vibrio cholerae recA mutant. J. Bacteriol. 165:715–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fullner, K.J., and J.J. Mekalanos. 1999. Genetic characterization of a new type IV pilus gene cluster found in both classical and El Tor biotypes of Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 67:1393–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klose, K.E. 2000. The suckling mouse model of cholera. Trends Microbiol. 8:189–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crean, T.I., M. John, S.B. Calderwood, and E.T. Ryan. 2000. Optimizing the germfree mouse model for in vivo evaluation of oral Vibrio cholerae vaccine and vector strains. Infect. Immun. 68:977–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu, H., M. Hanes, C.E. Chrisp, J.C. Boucher, and V. Deretic. 1998. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: pulmonary clearance of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and inflammation in a mouse model of repeated respiratory challenge. Infect. Immun. 66:280–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Enteric Diseases Program Review (Executive Summary). 1996. http://www.niaid.nih.gov/dmid/enteric/execsum.htm. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

- 41.WHO. 2001. Cholera Vaccines: WHO position paper. Wkly. Epid. Rep. 76:117–124. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tacket, C.O., G. Losonsky, J.P. Nataro, S.J. Cryz, R. Edelman, A. Fasano, J. Michalski, J.B. Kaper, and M.M. Levine. 1993. Safety and immunogenicity of live oral cholera vaccine candidate CVD110, a ΔctxA Δzot, Δace derivative of El Tor Ogawa Vibrio cholerae. J. Infect. Dis. 168:1536–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benítez, J.A., L. García, A. Silva, H. García, R. Fando, B. Cedré, A. Pérez, J. Campos, B.L. Rodríguez, J.L. Pérez, et al. 1999. Preliminary assessment of the safety and immunogenicity of a new CTXΦ-negative, hemagglutinin/protease-defective El Tor strain as a cholera vaccine candidate. Infect. Immun. 67:539–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor, D.N., K.P. Killeen, D.C. Hack, J.R. Kenner, T.S. Coster, D.T. Beattie, J. Ezzell, T. Hyman, A. Trofa, M.H. Sjogren, et al. 1994. Development of a live, oral, attenuated vaccine against El Tor cholera. J. Infect. Dis. 170:1518–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pearson, G.D., A. Woods, S.L. Chiang, and J.J. Mekalanos. 1993. CTX genetic element encodes a site-specific recombination system and an intestinal colonization factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 90:3750–3754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]