Gene regulation in eukaryotic cells is in part mediated through programs of chromatin methylation. On the DNA level, the presence of m5C, mostly at the CpG positions in the vertebrate genomes, allows the recruitment of multisubunit complex(es) consisting of the histone deacetylases and the so-called methyl-CpG-binding domain (MBD) proteins (2). These proteins each contain the MBD motif. Previously, a group of MBD proteins conserved in vertebrates have been identified, and they include MBD1, MBD2, MBD3, MBD4, and MeCP2 (15). In Drosophila melanogaster, an MBD protein, dMBD2/3, has been characterized that shares significant homology with the vertebrate MBD2 and MBD3 (30, 39).

On the other hand, methylation of the histones, in particular at Lys-9 of H3, also plays essential role in the modification of the chromatin structure (20, 42). The Pre-SET and SET domains within a group of histone methyltransferases are responsible for their intrinsic activities of Lys methylation (18). Interestingly, genetic evidence from studies of Neurospora spp. suggests that DNA cytosine methylation is downstream of the H3 methylation (37). Consistent with this, an Arabidopsis CpNpG DNA methyltransferase (CMT3) was shown to interact with the H3 Lys-9-binding protein, HP1, and thus provides a physical link between the sequential events of histone and DNA methylation in the plants (17). A similar event has recently been suggested to exist in the mammals (11).

An MBD motif has been located in the human histone H3K9 methylase SETDB1 (34). This implies that DNA methylation might also be located upstream of histone methylation. The following questions could be asked. How many eukaryotic MBD proteins also contain motifs required for histone modification, in particular the H3K9 methylation? How widespread are these proteins in different species? When the conserved MBD motif was used as the bait for search (1), a total of eleven, three, five, two, and twelve MBD-containing genes were found to exist in the genomes of humans, tunicates (Ciona intestinalis), D. melanogaster, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Arabidopsis thaliana, respectively. The same number of MBD proteins as in humans is found in the mouse genome, each representing the respective human ortholog (32). In contrast, none could be identified in the Archaea, protozoa, and fungus genomes (Table 1). Archaea has been placed as a distinct domain from the bacteria and eukaryotes in evolution, with their metabolic features closer to bacteria and information processing machinery closer to the eukaryotes (4). Quite a few Archaea species have been fully sequenced. Although putative methyltransferases have been proposed in Methanococcus janaschii (5), one of the fully sequenced archaeal species, no MBD protein could be encoded by its genome. Several protozoan genome projects are ongoing as well, and that of the human parasite Plasmodium falciparum has been finished (13). As found in Trypanosoma cruzi (31), DNA methylation has been observed in Plasmodium falciparum (27). However, its genome does not encode any MBD protein. On the other hand, of the two distinct classes of fungi, Saccharomyces cerevisiae lacks methylated cytosines (28), as well as the MBD proteins, whereas Neurospora crassa has well-documented DNA methylation (9) but does not encode MBD proteins. The findings of these genomic analyses of the distribution of MBD proteins are summarized in Table 1. As shown, there is no clear-cut relationship between the genome sizes of different species and the numbers of MBD proteins they encode. Neither do the latter reflect the extents to which the individual genomes are methylated.

TABLE 1.

Classification of MBD proteins found in databasea

| Classification | No. of MBD-containing proteins | No. of proteins in:

|

Genome size (million bases) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | Group II | Group III | |||

| Archaea, fungi, protozoa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Caenorhabditis elegans | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| Drosophila melanogaster | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 180 |

| Ciona intestinalis | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 160 |

| Mus musculus | 11 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2,500 |

| Homo sapiens | 11 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2,900 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 125 |

The conserved sequence of the MBD motif was used as the bait for a BLAST search. The search and collection of related information was performed at the following websites: NCBI (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (www.sanger.ac.uk), Ensembl (http://www.ensembl.org), JGI (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/ciona4/ciona4.home.html), TAIR (http://www.arabidopsis.org), MIPS Neurospora crassa database (http://mips.gsf.de/proj/neurospora), and Plasmodium genome database (http://PlasmoDB.org). The MBD proteins are classified according to their domain architecture as group I (MBD being the only or major motif), group II (MBD, followed by DDT, PHD, and the bromodomain), and group III (MBD consecutively laid with the Pre-SET and the SET domains).

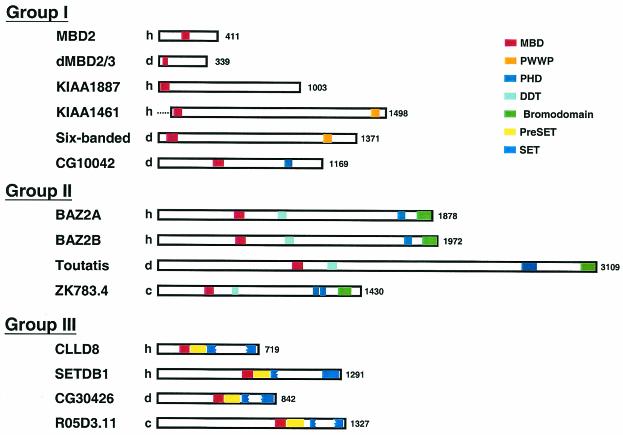

Further analysis of specific modules in the different MBD proteins have implicated their roles in histone modification and/or chromatin remodeling. As shown in Fig. 1, the MBD proteins identified in humans, flies, and worms could be classified into three groups according to their domain and/or motif structures. Within group I, MBD is the only or major well-defined module. Besides the previously identified MBD proteins, two human proteins, KIAA1887 and KIAA1461, and Drosophila SIX-BANDED (SBA) protein and CG10042 belong to this group (Fig. 1 and 2). Specifically, both KIAA1461 polypeptide and SBA contain another domain, PWWP, known to recognize DNA and often existing simultaneously with other chromoatin-association domains (29). The alignment result further suggests that these two proteins, along with KIAA1887, form a subgroup within the family based on the conservation of unique insertion between α1 helix and the hairpin-loop mainly present in these proteins (Fig. 2). The Drosophila protein CG10042 possesses one MBD motif and one plant homeodomain (PHD) finger. PHD is required for activity of the histone acetyltransferases (19). This suggests that CG10042 might transact signals between DNA methylation and histone acetylation.

FIG. 1.

Domain architecture of MBD proteins. The multiple MBD proteins are grouped according to the arrangement of different motifs within their sequences. The different motifs and domains are indicated by colored boxes. MBD, PWWP, bromodomain, PHD, and Pre-SET/SET are described in the text. DDT is a domain conserved in several transcription and chromatin remodeling factors (8). Note that of the five previously identified mammalian MBD proteins (15), only MBD2 is shown here as a representative. h, human; d, Drosophila; c, C. elegans. The accession numbers are as follows: MBD2, AF072242; KIAA1887, NM_052897; KIAA1461, AB040894 (this polypeptide misses a start site); BAZ2A, NM_013449; BAZ2B, NM_013450; CLLD8, AF334407; SETDB1, NM_12432; dMBD2/3, AE003683; six-banded, SD04244; CG10042, AE003695; Toutatis, AF314193; CG30426, AE003465; R05D3.11, NM_066447; and ZK783.4, NM_066272.

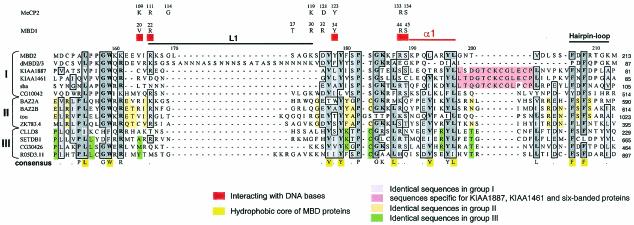

FIG. 2.

Sequence alignment of the MBD motifs. The alignment is constructed by using the Clustal W program and then examined manually, and the sequences are arranged in the order shown in Fig. 1. The numbers above the alignment correspond to the amino acid positions in human MBD2. Identical amino acids are boxed and shaded in dark gray; similar residues are boxed and shaded in light gray. Functionally important residues in the MBD motifs of MBD1 and MeCP2 are shown above the alignment. The definitions of L1, α1, and hairpin-loop indicated on the MBD2 sequence are derived from the study of MBD1 (26).

Within the second group (group II) are proteins containing the MBD, DDT, PHD, and bromodomain consecutively arranged in the same order: the human BAZ2A and BAZ2B, Drosophila TOUTATIS, and C. elegans ZK783.4. The homologous regions among these four proteins extend beyond these motifs, suggesting that these proteins are evolutionarily conserved (data not shown). The bromodomain interacts with acetylated lysine (7). Furthermore, TIP5, a mouse homolog of BAZ2A, was shown to be present in nucleolar remodeling complex, NoRC, which funtions in repressing RNA polymerase I transcription (43). It intereacts with HDAC1 through the PHD and bromodomain containing C terminus. In addition, the MBD of TIP5 does not preferentially bind to methylated oligonucleotide, which is well bound by MBD2 (43). As described in the latter section, however, specific residues possessed by MBD of the group II proteins differ from those present in the well-studied ones such as MBD2. Whether the amino acid variations create DNA sequence context specificity of MBD protein binding to methylated CpG awaits further study. The identification of the group II of MBD proteins suggests that functions mediated through m5C and acetylated histones could be coupled through the same protein(s).

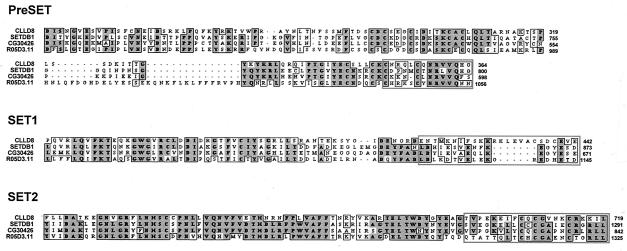

Finally, the last group contains the Pre-SET and the bifurcated SET domains consecutively located C terminal with respect to their MBD domains. Of the four proteins shown in Fig. 1, the coexistence of MBD and the Pre-SET/SET domains has been noted before for CLLD8, which is located in a region deleted in some B-cell chronic lymphocyte leukemia (24) and, as mentioned already, for the histone H3K9 methylase SETDB1 (34). Surprisingly, however, this pattern of coexistence extends into the flies and worms, as exemplied by the identification of Drosophila CG30426 and C. elegans R05D3.11. Sequence alignment of Fig. 3 shows that the Pre-SET and the bifurcated SET sequences (SET1 and SET2) of the group III proteins are highly homologous and that they also extend longer than the previously predicted boundaries of these domains.

FIG. 3.

Sequence alignment of Pre-SET/SET. Note that for either Pre-SET or the bifurcated SET (SET1 and SET2), the homologous sequences extend beyond the boundaries of the previously defined domains (the boxed regions).

The draft genome of the sea squirt, Ciona intestinalis, has been released recently (6). Its unique role in providing substaintial information between the transition from invertebrates to vertebrates is greatly appreciated. Three members of this species were identified to contain an MBD-like motif. Two of them, ci0100150311 and ci0100152686, belong to the group I proteins described above and, interestingly, the latter also appears to be the ortholog of MBD2 and MBD3. The third one, ci0100130152, shares the same domain architecture as the group III members of Fig. 1. Somewhat surprisingly though, no sea squirt protein belongs to group II, suggesting that the species might have chosen a regulatory path different from the rest of the animals and left out the cross talk between the programs of DNA methylation and histone acetylation. Whether this is unique for sea squirts or common in related species awaits further evidence.

The MBD sequences shown in Fig. 2 reveal both similar and unique features, both among themselves and in comparison to the previously defined MBD structures (10, 25, 26, 40). Besides the unique insertion conserved mainly for the subgroup of group I proteins described in the earlier section, the group II and group III MBD proteins possess their distinct features as well. As shown in Fig. 2, the similarity is apparently higher by groups rather than by species: proteins within the same group tend to use identical or homologous residues. The hydrophobic core structure is essentially maintained with few exceptions, such as the residue phenylalanine present in CLLD8 and SETDB1 at the position corresponding to residue W159 of MBD2. Loop 1 (L1) is a critical component in DNA recognition. Many residues within L1 interacting with the DNA backbone are highly conserved among the five previously identified MBD proteins, MBD1 to MBD4 and MeCP2. A few of these residues have been confirmed by mutagenesis experiments to play significant roles in DNA binding. However, L1 is no longer conserved in these other MBD proteins, and their primary sequences vary greatly. In particular, there is a large insertion rich in asparagine (N) in fly dMBD2/3. Despite this divergence, one previous study showed that dMBD2/3Δ, an alternative spliced isoform of dMBD2/3 containing only the N-terminal half of the MBD including the asparagine-rich insertion, is still capable of preferentially recognizing methylated cytosines, albeit with a weak binding affinity (30). Apparently, the MBDs of MBD1, MBD2, MBD3, MBD4, and MeCP2 proteins together form a highly conserved and distinct class of the MBD motifs. On the other hand, how the variations of the primary sequences in the other MBD proteins affect their DNA-binding properties in vivo and whether, like MBD3, they have gained additional functions (33) await further investigations.

Relative to its small genome size, A. thaliana apparently reserves a large family of the MBD proteins (Tables 1 and 2). Interestingly, 10 of the 12 MBD polypeptides contain the MBD motif alone. Furthermore, unlike the animal MBD proteins, the locations of the MBD motifs within the Arabidopsis proteins are highly variable (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

MBD proteins in A. thalianaa

| Gene | Length (amino acids) | Location(s) of MBD | Other features |

|---|---|---|---|

| At4g22745 | 198 | 109-174 | |

| At4g00416 | 163 | 70-137 | |

| At1g15340 | 384 | 9-72 | MDN1 motif |

| At5g59800 | 306 | 111-162, 177-238 | Two MBD domains |

| At5g35330 | 272 | 123-192 | |

| At5g59380 | 225 | 76-146 | |

| At3g15790 | 254 | 9-72 | |

| At3g46580 | 182 | 30-98 | |

| At3g63030 | 186 | 88-153 | |

| BAB11482 | 155 | 58-126 | |

| At1g22310 | 425 | 240-303 | |

| At3g01460 | 2,167 | 263-327 | Two PHD fingers |

Twelve MBD-containing polypeptides found in the genome of A. thaliana are summarized. The location(s) of the MBD motif(s) in each polypeptide is indicated. Two additional domains, MDN1 and PHD, were found in two of these MBD proteins. MDN1 is involved in the assembly and disassembly of multiprotein complexes (41). PHD is described in the text.

Several interesting implications could be inferred from the database analysis described above. First, the occurrence of MBD proteins is more widespread than previously thought. Not only are their numbers greater than those found in humans, flies, and other organisms, but they are also expressed in worms. Flies were assumed to lack m5C, but the identification of dDNMT2 and dMBD2/3 (16, 30, 39) has led to the demonstration of the existence of m5C in the fly genome (14, 23). Thus, the identification of the two C. elegans MBD proteins, one each in group II and III, implies that there may be m5C in the worm genome as well that escaped detection in the previous examination (36). Alternatively, the MBD proteins in worms, as well as in other eukaryotic species, likely carry out functions not requiring m5C.

Second, MBD proteins appear not to be required for gene regulation in some organisms, such as the protozoa and fungi. For the regulation of gene expression, there are at least two control mechanisms involving DNA methylation: one via the coupling of DNA methylation and MBD protein-mediated gene silencing (2) and another via the interplay between DNA methylation and histone methylation (12, 17, 37). It has been proposed that having both of the above-mentioned mechanisms could reinforce epigenetic silencing and create a self-propagating cycle to maintain a long-term transcriptional repression (3, 11). N. crassa is a popular model in the relevant studies, but apparently the former mechanism is missing in this organism due to the lack of MBD proteins. This finding is consistent with, but certainly not the sole explanation for, the observation that DNA methylation is dispensable in Neurospora (9, 21) but essential for the mammals (22). Also, methylation is not preferential at CpG dinucleotides in Neurospora (35) but occurs almost exclusively at CpGs in mammals. Finally, the methylated components in the genome of Neurospora reside mainly in the transposons. These distinct variations place Neurospora in a scenario different from that in mammals with respect to the function of DNA methylation.

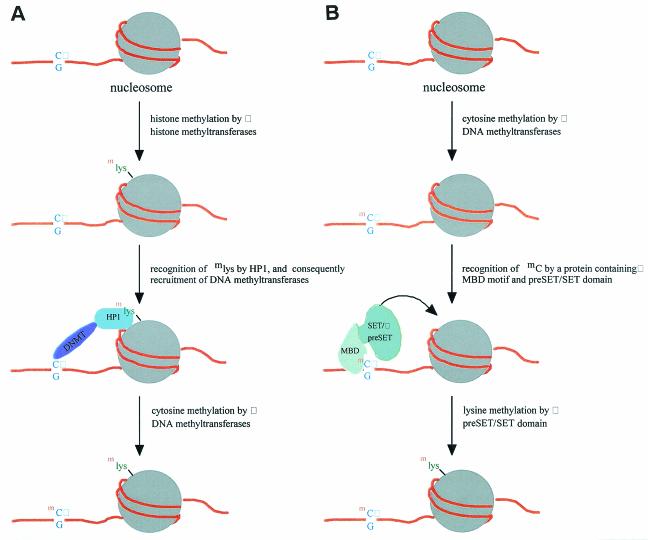

Finally, quite a few MBD proteins also contain modules needed for histone acetylation, histone methylation, or binding to the modified histones. Although MBD proteins have been found to exist and function in multiple-subunit complexes, the existence of the multiple group II and group III MBD proteins suggests that there is a more economic way(s) that nature utilizes to link the functions and processes of DNA methylation and histone modifications. Perhaps more significantly, as mentioned above, both genetic data from fungi studies (37) and biochemical evidence from plant (17) have indicated that along the gene regulation/chromatin methylation pathway, histone (H3) methylation is upstream of DNA methylation (Fig. 4A; see also the reviews in references 3 and 38). However, the existence of the group II and III MBD proteins (Fig. 1) suggests that initiation of histone modification, in particular methylation, by DNA methylation could be a common regulatory pathway utilized in the animal kingdom. Furthermore, this regulation could be accomplished by single MBD protein molecule(s). Specifically, a protein containing both MBD and the Pre-SET/SET could first bind to a DNA region with methylated CpG and later methylate the Lys-9 residue of H3 in the nearby nucleosome(s) (Fig. 4B). It is noteworthy that database mining has detected no Arabidopsis MBD proteins containing the Pre-SET/SET modules and that only one of them contains a motif in connection with histone modification (Table 2), which reflects a fundamental difference of regulatory scenarios between animals and plants.

FIG. 4.

Two scenarios of regulation of chromatin methylation. It is proposed that, unlike plants and fungi (A), DNA methylation could occur upstream of histone methylation through the stepwise functions by a single protein containing both MBD motif and a preSET/SET domain (B).

Acknowledgments

We thank S.-C. Wen for help in the preparation of Fig. 4 and Ai-Ying Chang for typing the manuscript.

This research was supported by the National Research Council, National Health Research Institute, and Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bird, A. 2002. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 16:6-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bird, A. P. 2001. Methylation talk between histones and DNA. Science 294:2113-2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cann, I. K. O., and Y. Ishino. 1999. Archaeal DNA replication: identifying the pieces to solve a puzzle. Genetics 152:1249-1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colot, V., and J.-L. Rossignol. 1999. Eukaryotic DNA methylation as an evolutionary device. Bioessays 21:402-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dehal, P., et al. 2002. The draft genome of Ciona intestinalis: insight into chordate and vertebrate origins. Science 298:2157-2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhalluin, C., J. E. Carlson, L. Zeng, C. He, A. K. Aggarwal, and M.-M. Zhou. 1999. Structure and ligand of a histone acetyltransferase bromodomain. Nature 399:491-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doerks, T., R. Copley, and P. Bork. 2001. DDT: a novel domain in different transcription and chromosome remodeling factors. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26:145-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foss, H. M., C. J. Roberts, K. M. Claeys, and E. U. Selker. 1993. Abnormal chromosome behavior in Neurospora mutants defective in DNA methylation. Science 262:1737-1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Free, A., R. I. D. Wakefield, B. O. Smith, D. T. F. Dryden, P. N. Barlow, and A. P. Bird. 2001. DNA recognition by the methyl-CpG binding domain of MeCP2. J. Biol. Chem. 276:3353-3360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuks, F., P. J. Hurd, R. Deplus, and T. Kouzarides. 2003. The DNA methyltransferases associate with HP1 and the SUV39H1 histone methyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:2305-2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuks, F., P. J. Hurd, D. Wolf, X. Nan, A. P. Bird, and T. Kouzarides. 2003. The methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 links DNA methylation to histone methylation. J. Biol. Chem. 278:4035-4040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardner, M. J., et al. 2002. Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 419:498-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gowher, H., O. Leismann, and A. Jeltsch. 2000. DNA of Drosophila melanogaster contains 5-methylcytosine. EMBO J. 19:6918-6923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hendrich, B., and A. Bird. 1998. Identification and characterization of a family of mammalian methyl-CpG binding proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:6538-6547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hung, M.-S., N. Karthikeyan, B. Huang, H.-C. Koo, J. Kiger, and C.-K. J. Shen. 1999. Drosophila proteins related to vertebrate DNA (5-cytosine) methyltransferases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:11940-11945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson, J. P., A. M. Lindroth, X. Cao, and S. E. Jacobsen. 2002. Control of CpNpG DNA methylation by the KRYPTONITE histone H3 methyltransferase. Nature 416:556-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenuwein, T. 2001. Re-SET-ting heterochromatin by histone methyltransferases. Trends Cell Biol. 11:266-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalkhoven, E., H. Teunissen, A. Houweling, C. P. Verrijzer, and A. Zantema. 2002. The PHD type zinc finger is an integral part of the CBP acetyltransferase domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:1961-1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kouzarides, T. 2002. Histone methylation in transcriptional control. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12:198-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kouzminova, E. A., and E. U. Selker. 2001. dim-2 encodes a DNA methyltransferase responsible for all known cytosine methylation in Neurospora. EMBO. 20:4309-4323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li, E., T. H. Bestor, and R. Jaenisch. 1992. Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell 69:915-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyko, F., B. H. Ramsahoye, and R. Jaenisch. 2000. DNA methylation in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature 408:538-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mabuchi, H., H. Fujii, G. Calin, H. Alder, M. Negrini, L. Rassenti, T. J. Kipps, F. Bullrich, and C. M. Croce. 2001. Cloning and characterization of CLLD6, CLLD7, and CLLD8, novel candidate genes for leukemogenesis at chromosome 13q14, a region commonly deleted in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Res. 61:2870-2877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohki, I., N. Shimotake, N. Fujita, M. Nakao, and M. Shirakawa. 1999. Solution structure of the methyl-CpG-binding domain of the methylation-dependent transcriptional repressor MBD1. EMBO J. 18:6653-6661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohki, I., N. Shimotake, N. Fujita, J.-G. Jee, T. Ikegami, M. Nakao, and M. Shirakawa. 2001. Solution structure of the methyl-CpG binding domain of human MBD1 in complex with methylated DNA. Cell 105:487-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pollack, Y., N. Kogan, and J. Golenser. 1991. Plasmodium falciparum: evidence for a DNA methylation pattern. Exp. Parasitol. 72:339-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Proffitt, J. H., J. R. Davie, D. Swinton, and S. Hattman. 1984. 5-Methylcytosine is not detectable in Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4:985-988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qiu, C., K. Sawada, X. Zhang, and X. Cheng. 2002. The PWWP domain of mammalian DNA methyltransferase Dnmt3b defines a new family of DNA binding folds. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:217-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roder, K., M.-S. Hung, T.-L. Lee, T.-Y. Lin, H. Xiao, K. I. Isobe, J.-L. Junag, and C.-K. J. Shen. 2000. Transcriptional repression by Drosophila methyl-CpG-binding proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:7401-7409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rojas, M. V., and N. Galanti. 1990. DNA methylation in Trypanosoma cruzi. FEBS Lett. 263:113-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roloff, T. C., H. H. Ropers, and U. A. Nuber. 2003. Comparative study of methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins. Genomics 4:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saito, M., and F. Ishikawa. 2002. The mCpG-binding domain of human MBD3 does not bind to mCpG but interacts with NuRD/Mi2 components HDAC1 and MTA2. J. Biol. Chem. 277:35434-35439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schultz, D. C., K. Ayyanathan, D. Negorev, G. G. Maul, and F. J. Rauscher III. 2002. SETDB1: a novel KAP-1-associated histone H3 lysine 9-specific methyltransferase that contributes to HP1-mediated silencing of euchromatic genes by KRAB zinc-finger proteins. Genes Dev. 16:919-932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Selker, E. U., D. Y. Fritz, and M. J. Singer. 1993. Dense nonsymmetrical DNA methylation resulting from repeat-induced point mutation in Neurospora. Science 262:1724-1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simpson, V. J., T. E. Johnson, and R. F. Hammen. 1986. Caenorhabditis elegans DNA does not contain 5-methylcytosine at any time during development or aging. Nucleic Acids Res. 14:6711-6719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamaru, H., and E. U. Selker. 2001. A histone H3 methyltransferase controls DNA methylation in Neurospora crassa. Nature 414:277-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turner, B. M. 2002. Cellular memory and the histone code. Cell 111:285-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tweedie, S., H.-H. Ng, A. L. Barlow, B. M. Turner, B. Hendrich, and A. Bird. 1999. Vestiges of a DNA methylation system in Drosophila melanogaster? Nat. Genet. 23:389-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wakefield, R. I. D., B. O. Smith, A. X. Nan, Free, A. Soteriou, D. Uhrin, A. P. Bird, and P. N. Barlow. 1999. The solution structure of the domain from MeCP2 that binds to methylated DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 291:1055-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whittaker, C. A., and R. O. Hynes. 2002. Distribution and evolution of von Willebrand/integrin A domains: widely dispersed domains with roles in cell adhesion and elsewhere. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:3369-3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang, Y., and D. Reinberg. 2001. Transcription regulation by histone methylation: interplay between different covalent modifications of the core histone tails. Genes Dev. 15:2343-2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou, Y., R. Santoro, and I. Grummt. 2002. The chromatin remodeling complex NoRC targets HDAC1 to the ribosomal gene promoter and represses RNA polymerase I transcription. EMBO J. 21:4632-4640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]