Abstract

The function of the intraepithelial lymphocyte (IEL) network of T cell receptor (TCR) γδ+ (Vγ5+) dendritic epidermal T cells (DETC) was evaluated by examining several mouse strains genetically deficient in γδ T cells (δ−/− mice), and in δ−/− mice reconstituted with DETC or with different γδ cell subpopulations. NOD.δ−/− and FVB.δ−/− mice spontaneously developed localized, chronic dermatitis, whereas interestingly, the commonly used C57BL/6.δ−/− strain did not. Genetic analyses indicated a single autosomal recessive gene controlled the dermatitis susceptibility of NOD.δ−/− mice. Furthermore, allergic and irritant contact dermatitis reactions were exaggerated in FVB.δ−/−, but not in C57BL/6.δ−/− mice. Neither spontaneous nor augmented irritant dermatitis was observed in FVB.β−/− δ−/− mice lacking all T cells, indicating that αβ T cell–mediated inflammation is the target for γδ-mediated down-regulation. Reconstitution studies demonstrated that both spontaneous and augmented irritant dermatitis in FVB.δ−/− mice were down-regulated by Vγ5+ DETC, but not by epidermal T cells expressing other γδ TCRs. This study demonstrates that functional impairment at an epithelial interface can be specifically attributed to absence of the local TCR-γδ+ IEL subset and suggests that systemic inflammatory reactions may more generally be subject to substantial regulation by local IELs.

Keywords: dermatitis, TCR γδ, mast cells, NOD, FVB

Introduction

Although adaptive immune responses to pathogens are triggered by exquisitely specific antigen receptors on responding, systemic T and B cells, the resulting effector mechanisms that eliminate the pathogen are typically not antigen specific, and can result in considerable damage to host tissues in which the pathogen and/or its products occur. Furthermore, adaptive immune responses are also frequently provoked by relatively innocuous environmental antigens that gain access to the body at epithelial interfaces with the environment, e.g., the skin, the genitourinary and the gastrointestinal tracts. Such allergic and inflammatory responses are a major cause of human disease.

One mechanism for controlling adaptive immune responses to such antigens is the induction of regulatory αβ+ T cells that enter the systemic circulation, and upon reencountering antigen, secrete cytokines (e.g., IL-10) that down-regulate potentially tissue-damaging inflammatory responses initiated by antigen-specific effector T cells (1–7). Additionally, immunoregulatory functions have been demonstrated for systemic TCR-γδ+ cells that, in many mammals including mice and humans, constitute a minor population of circulating T cells (8–10). In sum, the systemic circulation harbors subsets of cells that can provoke inflammation, and those that can suppress it.

In addition to recirculating T cells, some T cells are constitutively resident within epithelia. By virtue of the large surface area of epithelia, such intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs)*, including those in the human gut, may be among the most abundant T cell subsets. One conspicuous IEL repertoire is composed of dendritic epidermal T cells (DETC) that populate the skin of all normal mice. Most DETC express an identical Vγ5/Vδ1 TCR (11–13). The same Vγ5/Vδ1 TCR is expressed early in gestation (∼E14-E17) on a small fraction of fetal thymocytes that can reconstitute the skin of DETC-deficient (e.g., nude) mouse recipients (12, 14, 15). Furthermore, Vγ5/Vδ1+ T cells in adult mice are apparently restricted to the skin, as such cells are not present in lymph nodes, spleen and blood, or in other epithelial sites (e.g., gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary tract, lungs) that are by contrast populated by their own distinctive subsets of γδ+ IELs (12, 16–18).

IELs have been variously proposed to interact with epithelial cells, activated T cells, and antigen presenting cells (19–22). A very recent study has provided evidence in three different mouse models of skin cancer that γδ cells, including DETCs can function as antiepithelial tumor effector cells (23). This complements other studies demonstrating that human intestinal γδ+ IELs will kill human bowel carcinomas and other intestinal epithelial cell lines (24, 25), and that there is enhanced formation of chemically induced colorectal carcinomas in δ−/− mice (26). In addition to protecting epithelial tissues from disruption by transformed or infected epithelial cells, it has been hypothesized that γδ+ IELs might likewise protect epithelial tissues from damage or disruption by systemic, proinflammatory infiltrates. Indeed, data from a variety of studies are consistent with the possibility that resident γδ+ IELs in the skin or the gut locally down-regulate inflammatory responses to allergens or pathogens initiated by conventional αβ T cells (27–32). However, in none of those earlier studies did the experimental design critically test the hypothesis that the subset of γδ+ cells normally present in a particular site (e.g., Vγ5+ DETC in the skin) may be a critical, nonredundant regulator of a spectrum of physiological inflammatory reactions occurring within its immediate confines, i.e., that purified Vγ5+ DETC down-regulate different types of cutaneous inflammatory reactions, while other γδ+ cells do not.

To test this hypothesis, we have used several different genetic strains of δ–/– mice to examine the physiological consequences of cutaneous IEL (DETC) deficiency. The results demonstrate that some, but not other strains of δ−/− mice spontaneously develop localized chronic dermatitis. The pathology is driven by αβ T cells, since mice lacking both αβ T cells and γδ cells are asymptomatic. Consistent with this, TCR-δ−/− mice displaying spontaneous dermatitis also show augmented allergic and irritant contact dermatitis reactions. Adoptive transfer experiments in which susceptible FVB.δ−/− mice received either Vγ5+ cells (that selectively reconstitute DETC) or other subpopulations of γδ cells, showed that Vγ5+ DETC are necessary and sufficient to down-regulate both spontaneous and irritant contact dermatitis. In sum, these studies demonstrate that a local γδ IEL subset can contribute a general and nonredundant role in regulating the inflammatory infiltration of tissue provoked by conventional αβ T cells. In addition, because of its strain-dependence, and because it shares several characteristics of atopic dermatitis, a common, but incompletely understood human skin disease, the experimental approach described may provide a novel animal model for studying the genetic control of inflammatory pathology.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

TCR.δ−/−, and TCR.β−/− C57BL/6 mice (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were backcrossed to FVB (Taconic) and nonobese diabetic (NOD/LtJ; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) mice, 11 and 14 generations, respectively. FVB.β−/−δ−/− mice were produced by first crossing FVB.β−/− (N11) with FVB.δ−/− (N11) mice to obtain double-heterozygotes, and then intercrossing these animals to obtain the double-knockouts. For genetic studies, using both sexes in each strain, NOD.δ−/− mice were mated with C57BL/6.δ−/− mice to produce both (NOD × C57BL/6)F1.δ−/− and (C57BL/6 × NOD)F1.δ–/– offspring. F1.δ−/− mice were subsequently intercrossed to produce F2.δ–/– offspring, and were backcrossed to NOD.δ−/− mice (again using both sexes) to produce (F1 × NOD)BC.δ−/− and (NOD × F1)BC.δ–/– animals. Mice were kept in filter-topped cages with sterilized food and water, and autoclaved corncob bedding, changed at least once weekly. Repeat testing of these mice failed to identify known bacterial pathogens, mites, or pinworms on the skin.

Contact Dermatitis.

To induce allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), mice were sensitized on day 0 by epicutaneous application to razor-shaved abdominal skin of 25 μl of 0.5% DNFB in a mixture of acetone:olive oil (4:1). On day 5, after measuring baseline ear thickness with an engineer's micrometer, mice were challenged by applying 10 μl of 0.2% DNFB in acetone:olive oil to each side of each ear. Ears were remeasured 24 h after challenge; data are expressed as the ear swelling response above baseline (i.e., ear thickness 24 h after challenge minus ear thickness immediately before challenge) ±1 SE of the mean (SE).

For adoptive transfer of ACD reactivity, groups of immune lymph node cell donor mice (either FVB or FVB.δ−/−) were sensitized by application of 25 μl of 0.5% DNFB to the shaved abdomen and 3 μl to each paw, the tip of the jaw, and each side of each ear. 5 d later, single cell suspensions were prepared from the draining lymph nodes (cervical, axillary, inguinal, and femoral) of each group of donors. Groups of normal adult FVB recipient mice were injected intravenously with graded numbers of DNFB-immune lymph node cells; 2 h later, after measuring baseline each thickness, recipient ears were challenged with 0.2% DNFB. Ears were remeasured 24 h later, and the ear swelling response above baseline calculated.

For irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) assays, after measuring baseline ear thickness, 20 nmol tetradecanoylphorbol acetate (TPA) (in 10 μl acetone) were applied to each side of each ear of adult mice. Ears were remeasured 24 h after challenge (and in indicated experiments, again at 6 d after challenge), and mean ear swelling responses above baseline calculated as above. In one study (indicated in the text and legend to Fig. 5 B) TPA was reapplied to the ears weekly for a total of three applications.

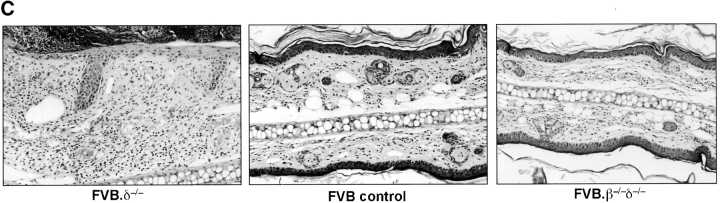

Figure 5.

Reconstitution with Vγ5+ E17 fetal thymocytes (DETC precursors) is sufficient to prevent spontaneous dermatitis in FVB.δ−/− mice. (A) Baseline ear thickness of 10-wk-old FVB mice (n = 4–5 mice per group; data expressed as mean ±SE): unreconstituted FVB.δ−/− mice (positive controls); normal FVB.δ+ mice (negative controls); FVB.δ−/− mice inoculated (intraperitoneally) as 1–3 d old neonates either with flow cytometry-purified (98% pure) Vγ5+ E17 fetal thymocytes (8 × 104 105 cells), or with flow cytometry-purified Vγ5– E17 fetal thymocytes (2 × 106 cells). (B) Flow cytometric analysis of epidermal cell suspensions individually prepared from the ears of these same mice. n = 4–5 mice per group. Data is expressed as the mean percentage (±SE) of epidermal cells which stained as Vγ5+ DETC (F536+ GL3+; black bars), as Vγ5− γδ T cells (F536+ GL3+; white bars), or as αβ T cells (CD3+ GL3−; hatched bars). nd, non-detected. (C) Flow cytometric analyses of epidermal cell suspensions prepared from the ears of a representative from each of the above four groups of mice. Numbers in lower right-hand corners of the quadrants of the contour plots indicate percentages of live cells within those quadrants.

Flow Cytometry.

To sort fetal thymocytes, a single cell suspension was prepared in Hank's balanced salt solution from thymi obtained from E17 FVB fetuses obtained after timed matings. Red blood cells and dead cells were removed by Lympholyte M (Accurate) density gradient centrifugation. Thymocytes were then blocked with normal hamster IgG and anti-FcR (2.4G2; BD PharMingen), stained with anti-Vγ5 (FITC-F536; BD PharMingen), or isotype-matched control, and sorted into Vγ5+ and Vγ5– populations on a FACSVantage™ (Becton Dickinson) using CellQUEST™ software.

To analyze epidermal T cell populations, separate epidermal cell suspensions were prepared as described from both ears of individual animals (13). After overnight culture to allow reexpression of trypsin-sensitive epitopes, epidermal cells were blocked with normal hamster IgG plus anti-FcR (2.4G2), and stained with hamster mAbs to CD3 (FITC-2C11; BD PharMingen), TCR-δ (Biotin-GL3 or FITC-GL3; BD PharMingen) and Vγ5 (Biotin-F536; BD PharMingen). Biotinylated antibodies were visualized with phycoerythrin-streptavidin. Isotype-matched control antibodies were used at the same concentrations as test antibodies. Analysis was performed with a FACScan™ (Becton Dickinson) with electronic gates set on live cells by a combination of forward and side light scatter and propidium iodide exclusion. A minimum of 104 live events was collected per sample and data were analyzed with CellQUEST™ software.

To analyze adult lymph node cells, aliquots from a single cell suspension of PLN (axillary and inguinal) cells from 8-wk-old FVB.β−/− donors were blocked with normal hamster IgG and anti-FcR, and then stained with either FITC-F536, FITC-GL3, or isotype-matched control antibody. FACScan™ analysis as described immediately above documented that the suspension contained ∼15% γδ+ (GL3+) T cells, but no detectable Vγ5+ cells.

Statistical Analysis.

Comparisons between datasets were made using a standard Student's two-tailed t test (33), unless otherwise specified. Chi-square analysis (34) was used to compare the phenotypic presence of ear crusting after irritant challenge between groups of mice, and to compare baseline ear thickness in different groups of mice (e.g., males versus females) using as a cutoff ≥5 SD above the average means for “resistant” B6.δ−/− and F1.δ−/− mice. In all cases, P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Strain-dependent Development of Spontaneous, Localized, Chronic Dermatitis in δ−/− Mice.

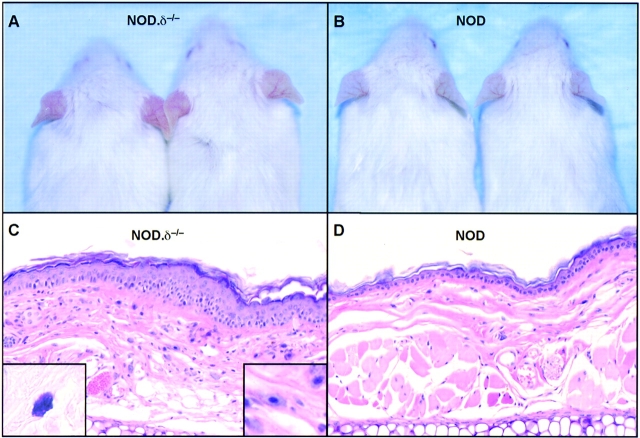

δ−/− mice on C57BL/6, FVB, or NOD backgrounds were examined for evidence of a cutaneous phenotype. Unmanipulated NOD.δ−/− mice developed a spontaneous cutaneous inflammation of the ears, manifested by erythema, edema, and pruritus, evident by 5–6 wk of age and becoming more obvious with age. This was not observed in any normal NOD controls (Fig. 1 A and B). In contrast to the normal histology of NOD ear skin, NOD.δ−/− ear skin showed histopathologic features typical of chronic dermatitis; a thickened epidermis with mild intercellular edema, scattered intraepidermal mononuclear inflammatory cells, and a thickened dermis with dilated blood vessels, mononuclear inflammatory cells, occasional eosinophils, and strikingly increased numbers of mast cells (Fig. 1 C and D). Micrometer measurements confirmed markedly increased baseline ear thickness (Fig. 1 E). Histopathologic evaluation of kidney, liver, spleen, small and large intestine, lung, and abdominal and back skin revealed no evidence of inflammation and no obvious differences between 12-wk-old NOD.δ−/− mice and NOD controls.

Figure 1.

Spontaneous dermatitis in the ears of unmanipulated δ−/− mice is strain dependent. (A) 12-wk-old NOD.δ−/− mice exhibit spontaneous ear erythema, while (B) age-matched NOD controls mice do not. (C) H&E stained section (original magnification: 200×) of a 12-wk NOD.δ−/− ear shows histologic features of chronic dermatitis, including increased numbers of mast cells (shown in left inset, Giemsa stain, Original magnification: 400×; and right inset, H&E stain. Original magnification: 400×). (D) H&E section of uninflamed ear of 12-wk-old NOD control mouse. (E) Increased baseline ear thickness of unmanipulated 12-wk-old NOD.δ−/− and FVB.δ−/− mice compared with age-matched NOD and FVB controls contrasts with the indistinguishable baseline ear thickness measured in 12-wk-old C57BL/6.δ−/− and C57BL/6 control mice (n = 12–18 mice per group). Data expressed as mean ±SE.

Highly significant, but less dramatic differences in baseline ear thickness also developed spontaneously in FVB.δ−/− mice relative to age-matched FVB controls (Fig. 1 E); this was paralleled by qualitatively similar, albeit less intense, histologic differences as described for NOD.δ−/− mice (data not shown). Such changes developed in FVB.δ−/− mice in the absence of overt clinical signs of spontaneous dermatitis, i.e., pruritus or erythema. In marked contrast, C57BL/6.δ−/− mice observed over a 6-mo period developed neither clinical nor histologic evidence of spontaneous dermatitis nor increased baseline ear thickness relative to age-matched C57BL/6 controls, thereby confirming an earlier study which reported no obvious phenotype in unmanipulated C57BL/6.δ−/− mice (30). Thus, the spontaneous development of localized chronic dermatitis in δ−/− mice is strikingly strain dependent.

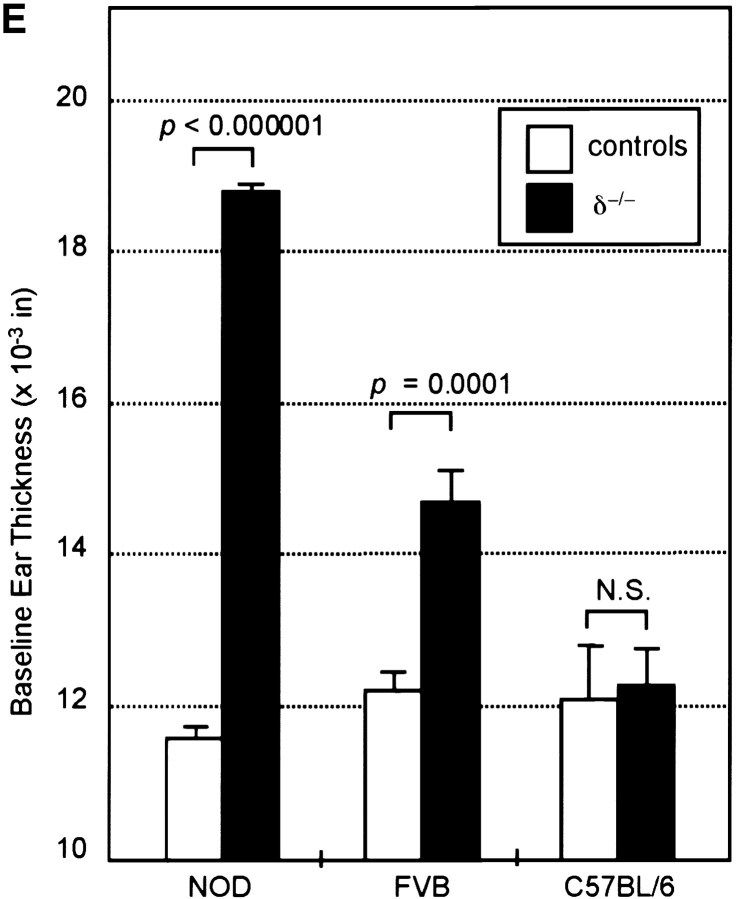

To understand better the genetics governing the susceptibility to spontaneous dermatitis, NOD.δ−/− mice and C57BL/6.δ−/− mice were mated to produce F1.δ−/− offspring. F1.δ−/− mice were subsequently intercrossed to produce F2.δ−/− offspring, while others were backcrossed to NOD.δ−/− mice to produce (F1 × NOD) and (NOD × F1) BC.δ−/− animals. Ear-thickness, as a manifestation of spontaneous dermatitis, was then examined in large numbers of these mice (Fig. 2) . The data have been segregated by sex, and show that baseline ear thickness in males tends to be higher than age-matched female counterparts (an expected finding given their larger size). Despite some variance observed in NOD.δ−/− mice, the mean ear thickness at 8–12 wk of age was markedly greater than age- and sex-matched C57B/6.δ−/− mice housed under identical conditions (Student's t test, unequal variance: P < 10−25), confirming the strain-dependent differences originally seen in smaller groups of animals (Fig. 1 E). F1.δ−/− progeny displayed no clinical signs of spontaneous dermatitis, and their baseline ear thickness was indistinguishable from that seen in age- and sex-matched C57BL/6.δ−/− mice. These results indicate that either the NOD background contributes recessive alleles that permit augmented cutaneous inflammation in the absence of γδ cells, and/or the C57BL/6 background contributes dominant alleles that overcome the effects of γδ cell deficiency.

Figure 2.

Spontaneous cutaneous inflammation in crosses of susceptible NOD.δ−/− with resistant C57BL/6 δ−/− mice. NOD.δ−/− and C57BL/6.δ−/− mice were bred to produce F1, F2, and (F1 × NOD) backcross (BC) offspring. Each symbol represents an individual animal, and data is shown separately for females (F) and males (M) of each group. Mean baseline ear thickness ±SD is given for each group of animals.

Such an inheritance pattern is consistent with both the F2 and BC data shown in Fig. 2. To identify susceptible (“NOD-like”) mice, increased baseline ear thickness was defined as ≥5 SDs above the average means for “resistant” B6.δ−/− and F1.δ−/− mice; i.e., F2 and BC females with an ear thickness of >14.0, and F2 and BC males with an ear thickness >15.5 were classified as susceptible. Using these criteria, 24.5% (41/167) of the F2 mice could be classified as NOD-like, while 42% (99/235) of the BC mice have the NOD-like phenotype. The incidence of spontaneous dermatitis of 25% in F2 mice and 42% in BC animals is consistent with the possibility that a single autosomal recessive gene is primarily responsible for the susceptibility of NOD.δ−/− mice. In such a case, the expected frequency of the phenotype in the F2 population is 25% and in the backcross population is 50%. Preliminary results examining F1, F2, and BC offspring from mating of C57BL/6.δ−/− and FVB.δ−/− mice are likewise consistent with a single autosomal recessive gene controlling the susceptibility to spontaneous dermatitis in FVB.δ−/− mice (data not shown).

Further analysis of crosses between NOD.δ−/− and C57BL6.δ−/− mice revealed that among F2.δ−/− mice, 32% (26/80) of females and 17% (15/87) of males were NOD-like. Among BC.δ−/− mice, 48% (55/114) of females and 36% (44/121) of males were NOD-like. These differences between the male and female incidences of the susceptible phenotype were not statistically significant. Likewise, the frequency of phenotypically susceptible mice was similar in groups of BC animals segregated according to the sex of the NOD parent (data not shown). In sum, there was no statistically significant evidence for sex-linked genes affecting the development of spontaneous dermatitis.

Strain-dependent Increases in Allergic and Irritant Contact Dermatitis Reactions in δ−/− Mice.

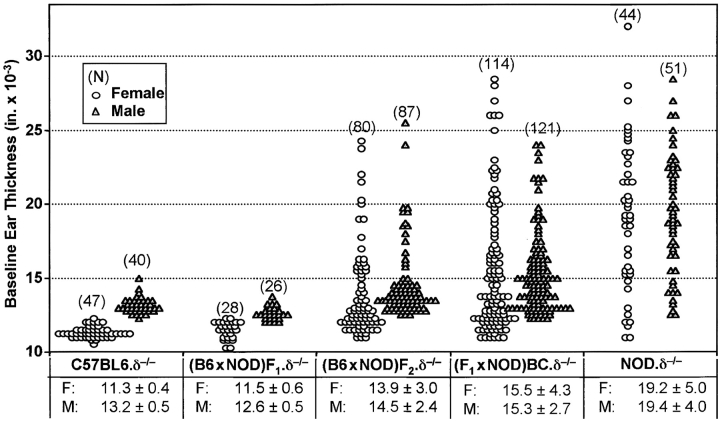

FVB.δ−/− and C57BL/6.δ−/− mice, as well as their respective TCR-δ+ controls, were next compared for their ACD responses to the allergen 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB). 24 h after DNFB challenge, sensitized FVB.δ−/− mice showed strikingly augmented ear swelling (measured as increase above baseline thickness) compared with sensitized, and challenged FVB mice. In contrast, responses of C57BL/6.δ−/− mice were indistinguishable from C57BL/6 controls (Fig. 3 A). Such enhanced ACD reactions in FVB.δ−/− mice were not restricted to DNFB; ear swelling in mice sensitized and challenged with the chemically unrelated allergen dimethyl-benzanthracene (DMBA) was also significantly greater than in FVB controls (data not shown).

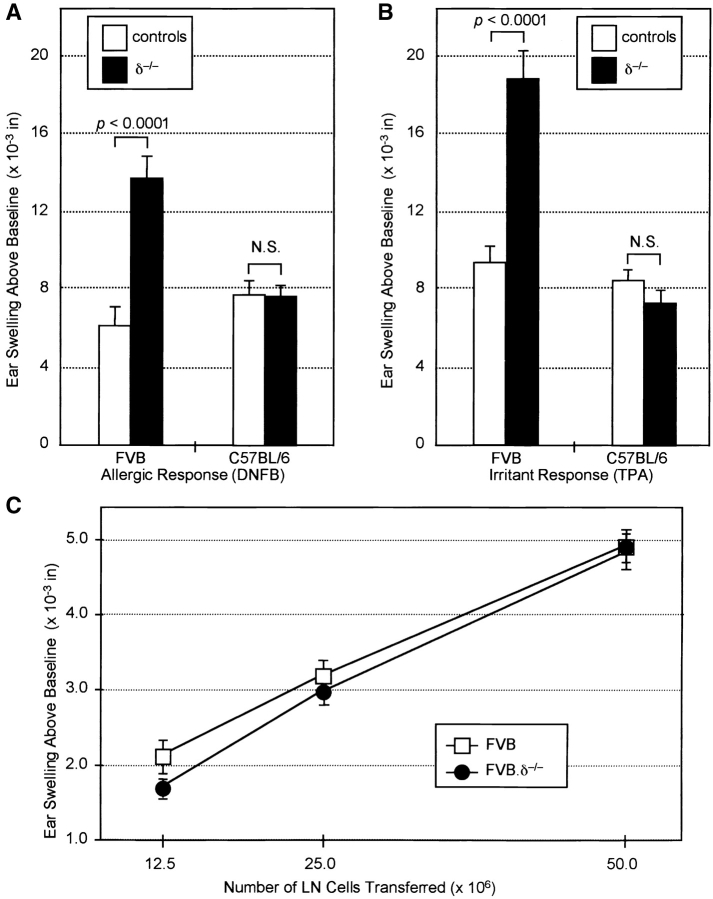

Figure 3.

Increased allergic and irritant contact dermatitis reactions in δ−/− versus wild-type mice are dependent on genetic background. (A) ACD responses 24 h after DNFB challenge of DNFB-immune control and δ−/− FVB and C57BL/6 mice (n = 10–20 mice per group; data expressed as mean ±SE). Ear swelling above baseline in FVB.δ–/– mice was more than twice that in FVB control mice (P < 0.0001), while responses of C57BL/6.δ−/− and control mice were indistinguishable. N.S., no significant difference. (B) Irritant contact dermatitis responses 24 h after TPA challenge of FVB and C57BL6 δ−/− and control mice. n = 10–15 mice per group; data expressed as mean ±SE. Ear swelling above baseline of FVB.δ−/− mice was nearly twice that of FVB mice (P < 0.0001), while equivalent responses were seen in C57BL/6.δ−/− and C57BL/6 mice. (C) Adoptive transfer of graded numbers of lymph node cells from DNFB-sensitized FVB.δ−/− or FVB donors to naive adult FVB recipients results in equivalent ear swelling responses 24 h after DNFB challenge.

ACD involves two distinct phases (35): during initiation, naive T cells in draining lymph nodes undergo antigen-driven clonal expansion and differentiate into effector cells; during elicitation, after reexposure to allergen, small numbers of antigen-specific effector T cells accumulate at sites of allergen reapplication where their triggering initiates a proinflammatory cascade (including increased vascular permeability; influx of other inflammatory cells and associated tissue swelling; and epidermal cell injury and proliferation). To distinguish whether γδ cells regulate ACD initiation and/or elicitation, draining lymph node cells from DNFB-immunized FVB or FVB.δ−/− donors were compared for their capacity to transfer anti-DNFB reactivity to nonsensitized adult FVB recipients. Cell yields from the draining lymph nodes of each strain were equivalent (∼20 × 106 cells per donor), and the dose–responses of cells from normal and δ−/− mice were indistinguishable (Fig. 3 C). Thus, during ACD initiation, similar numbers and/or activities of antigen-specific effector T cells are generated in δ−/− and control mice. Since γδ cells do not inhibit the initiation phase of ACD reactions, their more likely target is the elicitation phase.

Irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) reactions develop with delayed kinetics and histopathologic changes similar to ACD reactions. However, unlike ACD, ICD can be elicited in all individuals upon first exposure to sufficient concentrations of the irritant. Since ICD reactions do not require effector T cells specific for the offending chemical, they have only an elicitation phase. Thus, ICD provides an additional means by which to test whether γδ cells regulate elicitation events. FVB.δ−/− mice and C57BL/6.δ−/− mice, along with counterpart TCR-δ+ controls, were challenged with TPA, the active agent in the irritant croton oil, and the resulting ICD reactions compared by measuring the increase in ear thickness above baseline 24 h postchallenge. Again, irritant reactions to TPA were markedly increased in FVB.δ−/− mice (Fig. 3 B), providing further evidence that γδ cells down-regulate contact dermatitis elicitation events. Although the contact dermatitis responses were quantitated using the conventional measurement of ear swelling above baseline (i.e., baseline ear thickness has been subtracted), it is possible that the preexisting low-grade spontaneous dermatitis of FVB.δ−/− mice may have contributed to the augmented allergic and irritant responses; indeed other studies have shown that preexisting dermatitis predisposes such sites to enhanced irritant and ACD upon subsequent challenge (36–38).

In contrast to the enhanced ICD reactions to TPA observed in FVB.δ−/− mice, TPA challenge of C57BL/6.δ−/− mice resulted in ear swelling responses indistinguishable from those measured in C57BL/6 animals (Fig. 3 B), demonstrating that γδ cell down-regulation of contact dermatitis to irritants is also genetically controlled. Collectively, the failure of TCR-δ−/− mice on the C57BL/6 background to exhibit consistent differences from their wild-type counterparts with regard to either spontaneous or chemically induced contact dermatitis reactions, suggests that the conventional use of the C57BL/6 background for analysis of the TCR-δ−/− phenotype may have substantially underestimated the nonredundant roles that can be played by γδ cells in vivo (22).

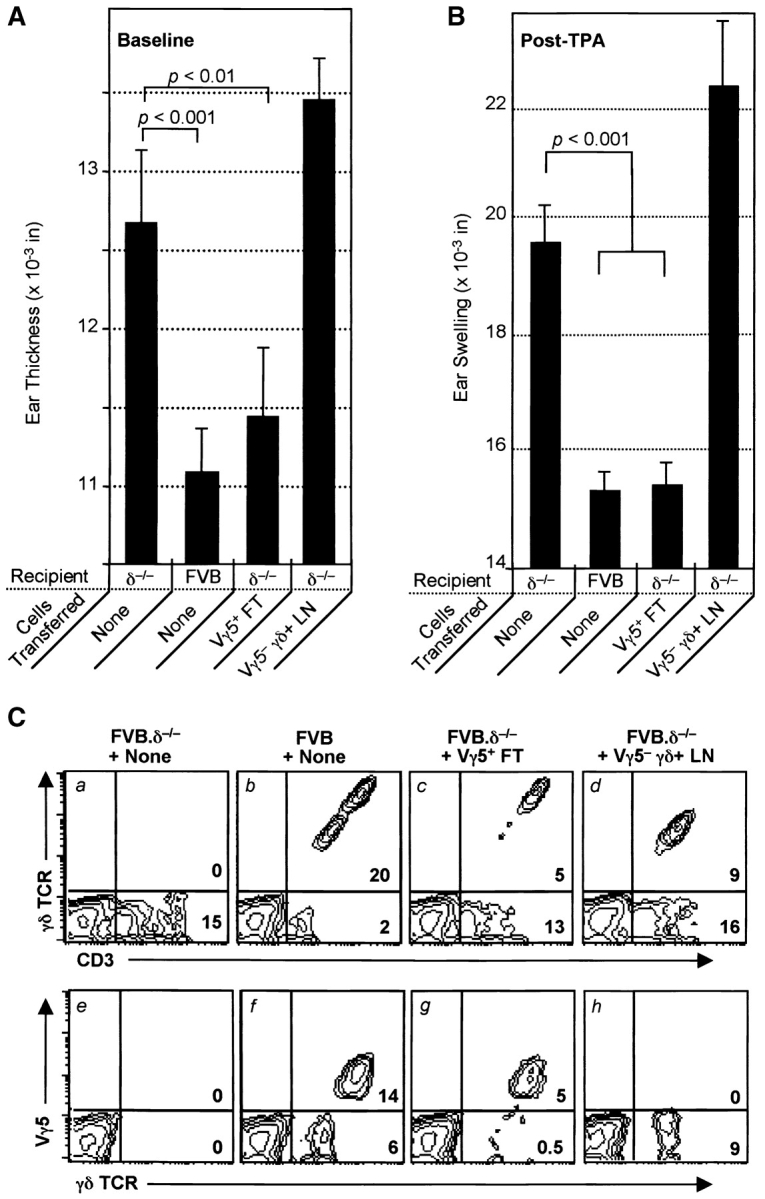

Spontaneous and Augmented Irritant Dermatitis Responses in δ− /− Mice Require αβ T Cells.

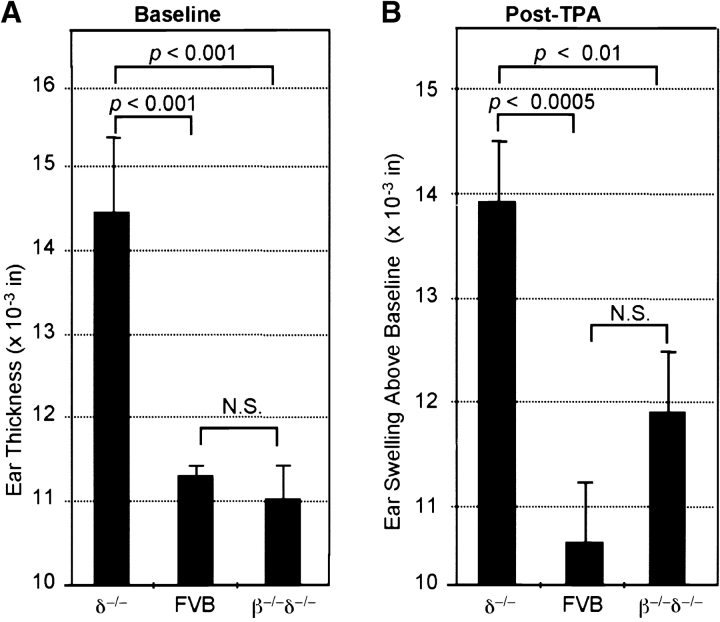

To investigate whether αβ T cells might directly or indirectly be targets of the antiinflammatory effects of γδ cells, FVB mice deficient in both in γδ and αβ T cells (FVB.β−/−δ−/−, backcrossed 11 generations onto the FVB background) were compared with FVB.δ–/– mice and FVB controls (Fig. 4) . Increased baseline ear thickness (spontaneous dermatitis) was again seen in FVB.δ−/− mice; in contrast, the baseline ear thickness of FVB.β−/−δ−/− mice was indistinguishable from controls, clearly indicating that αβ T cells are required for the development of spontaneous inflammation which occurs in the absence of γδ cells (Fig. 4 A). Similarly, while augmented irritant responses after TPA challenge were again seen in FVB.δ−/− mice, the irritant response in FVB.β−/−δ−/− mice was not significantly different from that of controls (Fig. 4 B). These data demonstrate that augmented ICD responses observed in the absence of γδ cells also depend, at least in part, on the presence of αβ T cells. These results seen 24 h after TPA challenge were confirmed and extended by analysis of these same groups of mice several days later. 6 d after TPA challenge, the ears of all FVB.δ−/− ears demonstrated histologic features of subacute dermatitis; variable amounts of scale-crust overlying a thickened epidermis with intraepidermal edema and intraepidermal mononuclear inflammatory cells, and a markedly thickened dermis containing a prominent infiltrate of mononuclear inflammatory cells and mast cells (Fig. 4 C). In contrast, ears of representative FVB and FVB.β−/−δ−/− mice exhibited equivalent, and much less striking, evidence of inflammation. Furthermore, as shown in Table I, 6 d after TPA challenge, 89% (16/18) of the ears of FVB.δ−/− mice showed visible scale-crust formation (another clinical sign of severe dermatitis), whereas 0/20 ears of control mice, and only 17% (3/18) ears of β−/−δ−/− mice developed scale-crust (χ2 analysis: P < 0.001 for FVB.δ−/− versus controls; no significant difference for FVB.β−/−δ−/− versus controls). Moreover, in 7/18 FVB.δ−/− ears, the severity of scale-crust formation was greater than that seen in any FVB.β−/−δ−/− mice. These findings demonstrate that αβ T cells are responsible for the development of the spontaneous dermatitis responses of FVB.δ−/− mice, and contribute to their enhanced irritant responses. In sum, the data suggest that a major function of γδ cells in genetically susceptible strains is to down-regulate local inflammatory responses provoked by αβ T cells.

Figure 4.

Increased baseline ear thickness (spontaneous dermatitis) and augmented irritant contact dermatitis responses to TPA in FVB.δ−/− mice are dependent on the presence of αβ T cells. (A) Baseline ear thickness is higher in 10-wk-old FVB.δ−/− mice than in FVB controls; however, age-matched FVB.β−/−δ−/− mice (deficient in both αβ+ and γδ+ T cells) exhibit no difference in baseline ear thickness relative to control FVB mice (n = 10 mice per group; data expressed as mean ±SE). (B) Irritant contact reactions of the same mice 24 h after challenge with TPA. As in Fig. 2 B, irritant reactions (shown as ear swelling above baseline) are significantly greater in FVB.δ−/− mice than in FVB controls; however, ear swelling in FVB.β−/−δ−/− mice is not significantly different from that in FVB controls. (C) 6 d after TPA challenge, FVB.δ−/− ears demonstrate histologic features of subacute dermatitis, while ears of representative FVB controls and FVB.β−/−δ−/− mice exhibit equivalent, and much less striking, evidence of inflammation (H&E, original magnification: 200×).

Table I.

Crusting Response Observed in FVB.δ2/− Mice 6 d after TPA Challenge Is Dependent on the Presence of αβ T Cells

| Crusting indexb

|

Total with crusting | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na | Strain | 0 | + | ++ | +++ | |

| 18 | FVB.δ2/− | 2 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 16c |

| 20 | FVB.δ1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0c , d |

| 18 | FVB.β2/−δ2/− | 15 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3d |

N = number of ears.

Crusting index: 0, no crusting; +, crusting at ear tip; ++, crusting of 25–75% of ear; +++, crusting of ≥75% of ear.

P < 0.01, chi-square analysis for presence of crusting in FVB.δ−/− versus FVB controls or FVB.β−/−δ−/−.

No significant difference for FVB controls versus FVB.β−/−δ−/−.

Vγ5+ DETCs Are Necessary and Sufficient for Down-Regulation of Dermatitis.

A key question was whether selective reconstitution of δ–/– animals with Vγ5+ DETC would restore normal regulation of cutaneous inflammation. Prior studies had shown that the E14–17 fetal thymus contains Vγ5+ DETC precursors which upon adoptive transfer reconstitute Vγ5+ DETC in the skin of DETC-deficient (i.e., nude) recipients (12, 14, 15). Accordingly, one group of 1–3 d-old FVB.δ−/− mice was inoculated (intraperitoneally) with two fetal thymus equivalents (8 × 104) of flow cytometry-sorted (>98% pure) Vγ5+ E17 fetal thymocytes; a second group received 2 × 106 (two fetal thymus-equivalents) of sorted Vγ5– E17 fetal thymocytes; a third group was left as unreconstituted FVB.δ−/− controls. 10 wk later, spontaneous inflammation in these groups and in age-matched FVB controls was assessed blind by measuring baseline ear thickness (Fig. 5 A). Immediately thereafter, cell suspensions prepared by trypsinization of epidermal sheets from the ears of individual mice were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the phenotype(s) of the T cells present within the epidermis. Fig. 5 B shows the mean percentage ±SE of Vγ5+ (F536+), γδ+ (GL3+), and αβ+ cells (the number of CD3+, i.e., 2C11+, cells minus the number of GL3+ cells) for each group of animals, while Fig. 5 C shows flow cytometry contour plots from a representative animal from each group.

Baseline ear thickness of FVB.δ−/− mice reconstituted with sorted Vγ5+ cells was indistinguishable from that measured in FVB controls, and significantly less than unreconstituted FVB.δ−/− mice (Fig. 5 A). Fig. 5 B and C show that cell suspensions prepared from the spontaneously inflamed ears of FVB.δ−/− mice were, as expected, devoid of γδ cells, but contained significant numbers of presumably proinflammatory, infiltrating αβ T cells (i.e., CD3+ γδ−), while the noninflamed ears of control mice contained T cells which were overwhelmingly Vγ5+, with small, but measurable numbers of Vγ5− γδ+ cells and rare αβ+ cells. The γδ cells isolated from the clinically noninflamed ears of FVB.δ−/− mice inoculated as newborns with sorted Vγ5+ fetal thymocytes were exclusively Vγ5+ DETC and were present in proportions indistinguishable from control mice. Thus, prototypic Vγ5+ DETC are clearly sufficient to restore wild-type (antiinflammatory) function to FVB.δ−/− skin. The increased baseline ear thickness measured in recipients of Vγ5– fetal thymocytes was similar to that in uninjected FVB.δ−/− mice (Fig. 5 A). However, because the ears of mice receiving Vγ5– fetal thymocytes were only minimally reconstituted with Vγ5− γδ+ T cells (0.15 vs. 1.5% present in normal FVB mice; Fig. 5 C, h versus f), this experimental group did not allow one to conclude that Vγ5− γδ+ cells could not also function as antiinflammatory cells within the skin, were they to be present in substantial numbers.

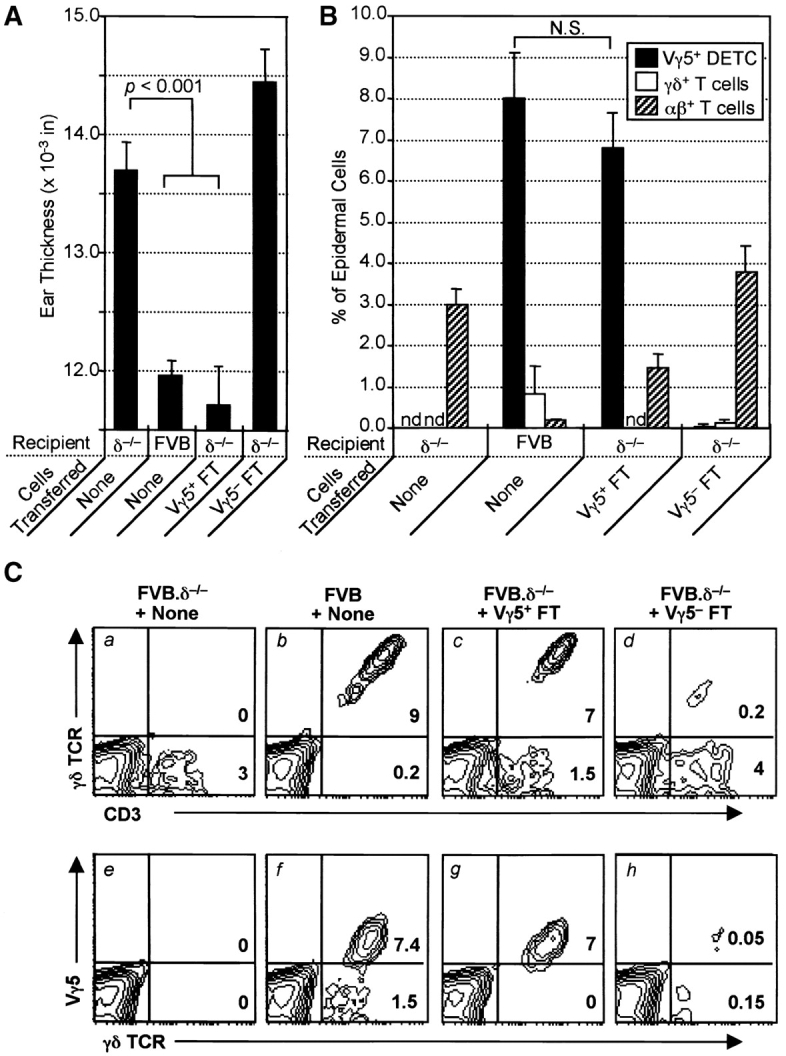

To address this question, an experimental approach was adopted that built on previous studies showing that the skin of experimentally manipulated mice can be repopulated by Vγ5− γδ+cells, including those expressing TCRs expressed by γδ cells found in PLNs or spleen (13, 39, 40). Therefore, selective reconstitution of FVB.δ−/− mice was again undertaken, this time including a group of newborn FVB.δ−/− mice inoculated with 1.5 × 106 Vγ5− γδ+ cells obtained from adult FVB.β–/– donor PLNs, as well as a group again reconstituted with Vγ5+ E17 fetal thymocytes. 10 wk later, after blind measurements of baseline ear thickness (Fig. 6 A), all mice were challenged once a week with the irritant TPA, and repeat measurements taken 24 h after the third challenge (Fig. 6 B). Subsequently, epidermal cell suspensions from the ears of individual mice were again analyzed by flow cytometry for their proportions of γδ+ cells, CD3+ γδ− (i.e., αβ) cells, and Vγ5+ cells (i.e., prototypic DETCs) (Fig. 6 C).

Figure 6.

Reconstitution withVγ5+ E17 fetal thymocytes (DETC precursors), but not Vγ5− adult peripheral lymph node γδ cells, down-regulates both spontaneous and irritant dermatitis in FVB.δ−/− mice. (A) Baseline ear thickness and (B) irritant ear swelling reactions 24 h after three weekly applications of TPA in groups of 10-wk-old FVB mice (n = 4–5 mice per group; data expressed as mean ±SE): unreconstituted FVB.δ−/− mice (positive controls); normal FVB.δ+ mice (negative controls); FVB.δ–/– mice reconstituted as 1–3-d-old neonates with either 8 × 104 flow cytometry-purified (98% pure) Vγ5+ fetal thymocytes from E17 FVB δ+ donors, or 107 peripheral lymph node cells (determined by flow cytometry to contain 1.5 × 106 Vγ5− γδ cells) obtained from 8-wk-old FVB.β−/− donors. (C) Flow cytometric analyses of epidermal cell suspensions prepared from the ears of a representative from each of the above four groups of mice. Numbers in lower right-hand corners of the quadrants of the contour plots indicate percentages of live cells within those quadrants.

Unreconstituted FVB TCR-δ−/− mice once again exhibited both spontaneous inflammation and augmented ICD reactions after TPA challenge compared with FVB mice (Fig. 6 A and B). Fig. 6 C (a and e versus b and f) shows that even in FVB mice repetitively challenged with TPA, >90% of epidermal T cells are γδ cells, the majority of which are Vγ5+. In contrast, unreconstituted FVB.δ−/− ear epidermis contained no γδ cells, but was infiltrated with large numbers of αβ cells. Since these analyses were performed after serial TPA challenge, it is likely that some of these epidermal αβ cells were nonresident, proinflammatory αβ T cells recruited into the ears as part of the spontaneous dermatitis in unmanipulated FVB.δ−/− mice, while others migrated in as part of the ICD response to TPA. In this experiment, the proportion of Vγ5+ DETC in the ears of FVB.δ−/− mice injected with sorted Vγ5+ fetal thymocytes was only ∼36% of that seen in normal mice (Fig. 6 C, g versus f). Nonetheless, such prototypic DETC-reconstituted FVB.δ−/− mice displayed baseline ear thickness and ICD responses to TPA indistinguishable from controls and significantly less than unreconstituted FVB.δ−/− mice (Fig. 6 A and B). In contrast, FVB.δ−/− mice injected at birth with Vγ5− γδ cells exhibited both spontaneous ear inflammation and augmented ICD reactions essentially the same as those measured in unreconstituted FVB.δ−/− mice (Fig. 6 A and B). The failure of these Vγ5− cells to restore normal function to the skin of FVB.δ−/− mice could not on this occasion be explained by their inability to repopulate the skin, since the epidermis of such animals contained at least as many Vγ5−γδ+ cells as were present in normal FVB mice (Fig. 6 C, h versus f). In sum, each of two reconstitution studies of genetically deficient mice have demonstrated that prototypic Vγ5+ DETC down-regulate αβ T cell–provoked cutaneous inflammation. Moreover, in one experiment where it was possible to populate the skin with substantial numbers of γδ cells bearing non-DETC TCRs, such down-regulation of αβ T cell–provoked local inflammation was not seen. Together, these data provide functional evidence for the importance both of DETC and of the TCR that they express.

Discussion

Previous studies have documented that mice deficient in all γδ cells may exhibit defective down-regulation of inflammation induced experimentally in various tissues, including epithelial interfaces with the external environment: e.g., localized graft-versus-host disease in the skin (30); parasitic infection of the gastrointestinal track (32); and pharmacologic (41), ozone or bacterial challenge of the airway (42). In two of these models, some restoration of normal function was achieved by providing unpurified populations of cells containing the cells typically found in that epithelial site (30, 32); however, since the reconstituting populations were heterogeneous, no conclusions could be reached regarding which γδ cell subset(s) were responsible for this down-regulation. This study thus represents a novel demonstration that a local functional impairment at an epithelial interface can be attributed to the specific absence of the local γδ cell subset constitutively resident within that tissue. As such, the results provide evidence that IELs indeed can exert local, nonredundant control of systemic inflammation at the critical interface of the organism with its external environment. Such regulation of inflammation by locally resident γδ cells may act in concert with recirculating γδ cells, which also have been demonstrated to influence the development of inflammation in different disease models (8–10). Furthermore, when considered together with the capacity of DETC to suppress the growth of carcinomas (23), this study suggests that DETC may have a general capacity to preserve epithelial integrity, whether from local epithelial cell damage, or from the disruptive effects of systemic infiltration. An analogous function may be shown by other IEL subsets, including those in the gut, where IELs have likewise been implicated both in the killing of transformed epithelial cells (24–26), and in the prevention of inflammatory bowel disease (43).

This paper is consistent with several previous studies which have reported that DETC can down-regulate particular cutaneous inflammatory responses (27–31). However, the experimental designs used in each of those studies did not permit the conclusion that the Vγ5+ DETC normal resident in murine epidermis can display a unique, nonredundant, capacity to down-regulate the αβ T cell–dependent components of both spontaneous and chemically induced contact dermatitis. For example, Bigby et al. (28) reported that the capacities of several strains of mice to express ACD reactions after sensitization and challenge was related to the different ratios of Langerhans cells to Thy-1+ DETC in normal skin of those different strains; however, the correlative nature of this study precluded definitive assignment of a down-regulatory role to Vγ5+ DETC.

Likewise, Sullivan et al. (27), documented a diminished capacity to be sensitized to the allergen DNFB in mice previously injected with DNBS-conjugated Thy-1+ DETC, while similar down-regulation of ACD was not seen in recipients of haptenated Langerhans cells or haptenated keratinocytes. Nonetheless, this study also did not show that such down-regulatory capacity was unique to DETC as opposed to other subsets of γδ cells. Moreover, the lack of evidence that prototypic Vγ5/Vδ1+ DETC migrate from the skin of adult mice to the draining lymph nodes or the systemic circulation (12) raises some questions about the biological relevance of this study as well as another (29) in which the experimental design involved intravenous transfer to normal adult recipients of a subset of γδ cells whose distribution in adult mice is apparently restricted to the skin.

Like this report, two previous studies have used δ−/− mice to investigate the role of γδ cells in cutaneous inflammatory responses. A report showing that C57BL/6.δ−/− mice displayed augmented ACD reactions to DNFB compared with wild-type controls (31) appears a priori to conflict with our failure in this study to show consistent differences between C57BL/6.δ−/− and control mice in their ACD responses to DNFB. However, while the studies reported in the present study compared inbred δ−/− to inbred control mice, the controls used by Weigmann et al. for comparison to inbred C57BL/6.δ−/− mice were (129 × C57BL/6)F1 animals. Given the recognized differences in the magnitude of ACD responses in different mouse strains (28), it is possible that genetic disparity, rather than the presence or absence of γδ cells, was responsible for some or all of the differences in ACD responses reported in that study.

Second, Shiohara and colleagues reported that C57BL/6.δ−/− mice failed to down-regulate the intraepidermal component of cutaneous graft-versus-host disease after reinjection into the footpad of cloned, MHC class II autoreactive CD4+ αβ cells; in contrast, intraepidermal “resistance” was seen in the footpads of C57BL/6.δ−/− mice previously injected with unpurified fetal thymocytes from control, δ+ E14–16 fetal donors (30). The apparent contrast between this phenotype obtained for C57BL/6.δ−/− mice and the lack of phenotype of C57BL/6.δ−/− mice shown here regarding spontaneous or chemically induced dermatitis, may reflect the very powerful proinflammatory stimulus adopted by Shiohara and colleagues. This notwithstanding, the two studies are highly consistent in attributing immunoregulatory function to DETC. Nevertheless, the present studies substantially extend those of Shiohara et al. by showing that among the various populations of cells present in the E14–17 fetal thymus, Vγ5+ DETC precursors are sufficient for down-regulating a variety of cutaneous inflammatory responses, including those physiologic responses that occur spontaneously. By contrast, at least some other subpopulations of γδ cells, such as those present in the PLNs, are unable to mediate such local down-regulation, despite their ability to enter the skin in substantial numbers.

The functional importance of DETC that is revealed in this study provides a powerful complement to one previous and two more recent molecular genetic studies suggesting that the stable establishment of DETC repertoires in vivo depends on the IELs expressing a particular type of TCR (13, 44, 45). For example, in Vγ5−/− mice, congenitally unable to express the canonical Vγ5/Vδ1 DETC receptor, a substantial fraction of the “substitute” DETC that develop utilize a novel Vγ1/Vδ1 chain pairing to encode a TCR reactive to a DETC-specific clonotypic antibody (13).

The spontaneous, localized, cutaneous inflammation that develops in some, but not other strains of δ−/− mice has several similarities to the dermatitis previously reported to develop in the NC/Nga mouse (46–48), which has been proposed as a relevant mouse model for human atopic dermatitis, a common, chronic, and incompletely understood inflammatory skin disease with a broad socioeconomic impact throughout the world (49). Shared features of the animal model described in the present studies with human atopic dermatitis include genetic predisposition (50–55); histopathology (56) dependence on αβ T cells (57); localization to areas of skin also commonly exposed to environmental irritants and/or allergens (58); and increased expression of contact dermatitis (59). Additional studies evaluating IgE levels and the effects of environmental manipulation on the development of the dermatitis, as well as more detailed genetic analyses (see below) will be required to clarify other similarities and/or differences between the present model, the NC/NGA model, and human atopic dermatitis. To date, no evidence has correlated human atopic dermatitis to either a numerical or functional deficiency in γδ cells; furthermore, human skin clearly is not obviously populated with a precise phenotypic homologue of the Vγ5+ DETC found in murine skin (60). On the other hand, recent analysis of normal human skin has revealed that cutaneous γδ T cells demonstrate a restricted TCR-γδ repertoire distinct from that of peripheral blood γδ T cells (61), and it is conceivable that such human cutaneous γδ cells represent functional equivalents of murine intracutaneous Vγ5+ regulatory cells. Importantly, the work presented here focuses attention on the potential for local resident cells to control the magnitude of tissue inflammation by systemic cells in a unique and nonredundant fashion.

These studies have not definitively addressed several longstanding questions in the arena of cutaneous γδ cell immunobiology, including the relevant mechanism(s) by which these cells exert their down-regulatory effects in the skin. Do DETC down-regulate αβ-dependent inflammatory responses via direct effects on such T cells or a subset thereof (e.g., Th2 or Th1), or via indirect effects, for example on the keratinocytes with which they are in intimate contact, on other cells normally resident in the skin (e.g., mast cells), or on cells recruited into the skin in response to inflammatory stimuli (e.g., monocyte/macrophages)? Likewise, do DETC down-regulate inflammation by elaborating antiinflammatory cytokines, by directly killing infiltrating cells, and/or by rendering the local tissue resistant to inflammatory cells? One strategy to address these latter possibilities will be to compare chemical induced and/or spontaneous dermatitis in NOD.δ−/− and/or FVB.δ−/− mice with similar mice reconstituted as newborns with Vγ5+ fetal thymocytes from donors genetically deficient in specific molecules known or suspected to be produced by DETC (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-10, TGF-β, Fas-L, granzymes, perforin) (20–22). Moreover, a recent large scale description of genes expressed by murine gut IELs (62) has identified other candidate molecules that may be responsible for immunoregulation by IELs, including DETC; such molecules include prothymosin β4 (63) and monoclonal nonspecific suppressor factor (64).

Finally, the results presented herein represent the first demonstration of a strain-dependent, spontaneous phenotype developing in an antigen receptor knockout mouse. Genetic differences between C57BL/6 mice and FVB or NOD mice render the former strain phenotypically resistant, and the latter strains phenotypically susceptible to the increased cutaneous inflammation that results from γδ cell (DETC) deficiency. Such resistance of C57BL/6.δ−/− mice could mean that they lack the necessary cell(s) and/or factor(s) required to initiate and/or express spontaneous dermatitis in the absence of γδ cells (while NOD and FVB mice possess such cells/factors). Alternatively, C57BL/6 mice, but not either FVB or NOD mice, possess additional cell(s)/factor(s) that can down-regulate the initiation and/or expression of spontaneous inflammation in the absence of γδ cells. The initial genetic analyses of such differences presented in this study are consistent with a single autosomal gene being primarily responsible for controlling such resistance/susceptibility. Genome-wide microsatellite mapping studies are underway to determine the actual number and identity of relevant modifier loci in NOD.δ−/− and FVB.δ−/− mice. These studies should reveal whether the loci controlling spontaneous dermatitis in susceptible δ−/− mice are similar to any of the loci previously linked to susceptibility either to atopic dermatitis in humans (50–55) and/or to the “atopic-like” dermatitis seen in other mouse models (48, 65–68). Likewise, it will be useful to compare the loci controlling spontaneous dermatitis in NOD.δ−/− and FVB.δ−/− mice with those regulating susceptibility of NOD mice to autoimmunity (69, 70). In conclusion, additional studies aimed at understanding the genetic, regulatory, and effector mechanisms which govern the actions of a skin-specific subset of γδ cells in mice, are likely to provide insights into the complex local regulation of the wide variety of inflammatory diseases which can affect the epithelial interfaces (i.e., skin, respiratory, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary tracts) of many species, including humans.

Acknowledgments

All mice used in this study were bred and maintained in an AALAC-accredited facility and handled according to approved protocols. We thank Stephanie Donaldson for assistance with mouse breeding.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (to R.E. Tigelaar, A.C. Hayday, and M. Girardi), the Dermatology Foundation (to M. Girardi), the Wellcome Trust (to A.C. Hayday), and utilized core laboratory facilities of the Yale Skin Diseases Research Core Center. Mouse breeding program supported by NIH DK5 3015 (A. Hayday and C.A. Janeway).

L. Geng's current address is Dana Farber Cancer Center, Harvard University School of Medicine, Boston, MA 02115.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: ACD, allergic contact dermatitis; DETC, dendritic epidermal T cell; IEL, intraepithelial lymphocyte; TPA, tetradecanoylphorbol acetate.

References

- 1.Mason, D., and F. Powrie. 1998. Control of immune pathology by regulatory T cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 10:649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacDonald, T.T. 1998. T cell immunity to oral allergens. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 10:620–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asserman, C., S. Mauze, M.W. Leach, R.L. Coffman, and F. Powrie. 1999. An essential role for interleukin 10 in the function of regulatory T cells that inhibit intestinal inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 190:995–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonuleit, H., E. Schmitt, M. Stassen, A. Tuettenberg, J. Knop, and A.H. Enk. 2001. Identification and functional characterization of human CD4+CD25+ T cells with regulatory properties isolated from peripheral blood. J. Exp. Med. 193:1285–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suri-Payer, E., and H. Cantor. 2001. Differential cytokine requirements for regulation of autoimmune gastritis and colitis by CD4+CD25+ T cells. J. Autoimmun. 16:115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taams, L.S., J. Smith, M.H. Rustin, M. Salmon, L.W. Poulter, and A.N. Akbar. 2001. Human anergic/suppressive CD4+CD25+ T cells” a highly differentiated and apoptosis-prone population. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:1123–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salomon, B., and J.A. Bluestone. 2001. Complexities of CD28/B7:CTLA-4 costimulatory pathways in autoimmunity and transplantation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:225–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huber, S.A., D. Graveline, M.K. Newell, W.K. Born, and R.L. O'Brien. 2000. Vγ1+ T cells suppress and Vγ4+ T cells promote susceptibility to coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis in mice. J. Immunol. 165:4174–4181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egan, P.J., and S.R. Carding. 2000. Downmodulation of the inflammatory response to bacterial infection by γδ T cells cytotoxic for activated macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 191:2145–2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Brien, R.L., M. Lahn, W.K. Born, and S.A. Huber. 2001. T cell receptor and function co-segregate in γ-δ T cell subsets. Chem. Immunol. 79:1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asarnow, D.M., W.A. Kuziel, M. Bonyhadi, R.E. Tigelaar, P.W. Tucker, and J.P. Allison. 1988. Limited diversity of γδ antigen receptor genes of Thy-1+ dendritic epidermal cells. Cell. 55:837–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tigelaar, R.E., and J.M. Lewis. 1995. Immunobiology of mouse dendritic epidermal T cells: a decade later, some answers, but still more questions. J. Invest. Dermatol. 105:43S–49S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mallick-Wood, C.A., J.M. Lewis, L.I. Richie, I. Rosewell, M.J. Owen, R.E. Tigelaar, and A.C. Hayday. 1998. Conservation of T cell receptor conformation in epidermal γδ cells with disrupted primary Vγ gene usage. Science. 279:1729–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Havran, W.L., and J.P. Allison. 1990. Origin of Thy-1+ dendritic epidermal cells of adult mice from fetal thymic precursors. Nature. 344:68–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Payer, E., A. Elbe, and G. Stingl. 1991. Circulating CD3+/T cell receptor Vγ3+ fetal murine thymocytes home to the skin and give rise to proliferating dendritic epidermal T cells. J. Immunol. 146:2536–2543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kyes, S., E. Carew, S.R. Carding, C.A. Janeway, Jr., and A. Hayday. 1989. Diversity in T-cell receptor γ gene usage in intestinal epithelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 86:5527–5531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itohara, S., A.G. Farr, J.J. Lafaille, M. Bonneville, Y. Takagaki, W. Haas, S. Tonegawa. 1990. Homing of a γδ thymocyte subset with homogeneous T-cell receptors to mucosal epithelia. Nature. 343:754–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayes, S.M., A. Sirr, S. Jacob, G.K. Sim, and A. Augustin. 1996. Role of IL-7 in the shaping of the pulmonary γδ T cell repertoire. J. Immunol. 156:2723–2729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janeway, C.A., Jr., B. Jones, and A. Hayday. 1988. Specificity and function of T cells bearing γ/δ receptors. Immunol. Today. 9:73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Born, W., C. Cady, J. Jones-Carson, A. Mukasa, M. Lahn, and R. O' Brien. 1999. Immunoregulatory functions of γδ T cells. Adv. Immunol. 71:77–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Havran, W.L. 1999. A role for epithelial γδ T cells in tissue repair. Immunol. Res. 21:63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayday, A.C. 2000. γδ cells: a right time and a right place for a conserved third way of protection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:975–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girardi, M., D. Oppenheim, J. Lewis, R. Filler, R.E. Tigelaar, and A.C. Hayday. 2001. The regulation of squamous cell carcinoma development by γδ T cells. Science. 294:605–609. 11567106 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Groh, V., A. Steinle, S. Bauer, and T. Spies. 1998. Recognition of stress-induced MHC molecules by intestinal epithelial γδ T cells. Science. 279:1737–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Groh, V., A.R. Rhinehart, H. Sechrist, S. Bauer, and T. Spies. 1999. Broad tumor-associated expression and recognition by tumor-derived γδ T cells of MICA and MICB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:6879–6884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuda, S., S. Kudoh, and S. Katayama. 2001. Enhanced formation of azoxymethane-induced colorectal carcinoma in γδ T lymphocyte-deficient mice. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 92:880–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sullivan, S., P.R. Bergstresser, R.E. Tigelaar, and J.W. Streilein. 1986. Induction and regulation of contact hypersensitivity by resident, bone marrow-derived, dendritic epidermal cells: Langerhans cells and Thy-1+ epidermal cells. J. Immunol. 137:2460–2467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bigby, M., T. Kwan, and M.S. Sy. 1987. Ratio of Langerhans cells to Thy-1+ dendritic epidermal cells in murine epidermis influences the intensity of contact hypersensitivity. J. Inv. Dermatol. 89:495–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Welsh, E.A., and M.L. Kripke. 1990. Murine Thy-1+ dendritic epidermal cells induce immunologic tolerance in vivo. J. Immunol. 144:883–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shiohara, T., N. Moriya, J. Hayakawa, S. Itohara, and H. Ishikawa. 1996. Resistance to cutaneous graft-vs.-host disease is not induced in T cell receptor δ gene-mutant mice. J. Exp. Med. 183:1483–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weigmann, B., J. Schwing, H. Huber, R. Ross, H. Mossmann, J. Knop, and A.B. Reske-Kunz. 1997. Diminished contact hypersensitivity response in IL-4 deficient mice at a late phase of the elicitation reaction. Scand. J. Immunol. 45:308–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts, S.J., A.L. Smith, A.B. West, L. Wen, R.C. Findly, M.J. Owen, and A.C. Hayday. 1996. T-cell αβ+ and γδ+ deficient mice display abnormal but distinct phenotypes toward a natural, widespread infection of the intestinal epithelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93:11774–11779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Sokal, R.R., and F.J. Rohlf. 1981. Biometry, 2nd ed. W.H. Freeman and Company, New York. 1–859.

- 34.Sokal, R.R., and F.J. Rohlf. 1981. Biometry, 2nd ed. W.H. Freeman and Company, New York. 1–859.

- 35.Bour, H., M. Krasteva, and J.-F. Nicolas. 1997. Allergic Contact Dermatitis. Skin Immune System, 2nd ed. J.D. Bos, editor. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. 509–522.

- 36.Arlette, J.P., and M.J. Fritzler. 1984. Reduced skin threshold to irritation in the presence of allergic contact dermatitis in the guinea pig. Contact Dermatitis. 11:31–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McLelland, J., J. Shuster, and J.N. Matthews. 1991. ‘Irritants’ increase the response to an allergen in allergic contact dermatitis. Arch. Dermatol. 127:1016–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hindsen, M., and M. Bruze. 1998. The significance of previous contact dermatitis for elicitation of contact allergy to nickel. Acta Derm. Venereol. 78:367–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferrick, D.A., S.R. Sambhara, W. Ballhausen, A. Iwamoto, H. Pircher, C.L. Walker, W.M. Yokoyama, R.G. Miller, and T.W. Mak. 1989. T cell function and expression are dramatically altered in T cell receptor Vγ1.1Jγ4Cγ4 transgenic mice. Cell. 57:483–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonneville, M., S. Itohara, E.G. Krecko, P. Mombaerts, I. Ishida, M. Katsuki, A. Berns, A.G. Farr, C.A. Janeway, and S. Tonegawa. 1990. Transgenic mice demonstrate that epithelial homing of γ/δ T cells is determined by cell lineages independent of T cell receptor specificity. J. Exp. Med. 171:1015–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lahn, M., A. Kanehiro, K. Takeda, A. Joetham, J. Schwarze, G. Kohler, R. O'Brien, E.W. Gelfand, W. Born, and A. Kanehio. 1999. Negative regulation of airway responsiveness that is dependent on γδ T cells and independent of αβ T cells. Nat. Med. 5:1150–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.King, D.P., D.M. Hyde, K.A. Jackson, D.M. Novosad, T.N. Ellis, L. Putney, M.Y. Stovall, L.S. Van Winkle, B.L. Beaman, and D.A. Ferrick. 1999. Cutting edge: protective response to pulmonary injury requires γδ T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 162:5033–5036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poussier, P., T. Ning, J. Chen, D. Banerjee, and M. Julius. 2000. Intestinal inflammation observed in IL-2R/IL-2 mutant mice is associated with impaired intestinal T lymphopoiesis. Gastroenterology. 118:880–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hara, H., K. Kishihara, G. Matsuzaki, H. Takimoto, T. Tsukiyama, R.E. Tigelaar, and K. Nomoto. 2000. Development of dendritic epidermal T cells with a skewed diversity of γδ TCRs in Vδ1-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 165:3695–3705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrero, I., A. Wilson, F. Beermann, W. Held, and H.R. MacDonald. 2001. T cell receptor specificity is critical for the development of epidermal γδ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 194:1473–1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsuda, H., N. Watanabe, G.P. Geba, J. Sperl, M. Tsudzuki, J. Hiroi, M. Matsumoto, H. Ushio, S. Saito, P.W. Askenase, and C. Ra. 1997. Development of atopic dermatitis-like skin lesion with IgE hyperproduction in NC/Nga. Int. Immunol. 9:461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vestergaard, C., H. Yoneyama, M. Murai, K. Nakamura, K. Tamaki, Y. Terashima, T. Imai, O. Yoshie, T. Irimura, H. Mizutani, and K. Matsushima. 1999. Overproduction of Th2-specific chemokines in NC/Nga mice exhibiting atopic dermatitis–like lesions. J. Clin. Invest. 104:1097–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kohara, Y., K. Tanabe, K. Matsuoka, N. Kanda, H. Matsuda, H. Karasuyama, and H. Yonekawa. 2001. A major determinant quantitative-trait locus responsible for atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions in NC/Nga mice is located on Chromosome 9. Immunogenetics. 53:15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boguniewicz, M., and D.Y.M. Leung. 2000. Atopic Dermatitis. Allergic Skin Disease. D.Y.M. Leung and M.W. Greaves, editors. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York. 125–169.

- 50.Diepgen, T.L., and M. Blettner. 1996. Analysis of familial aggregation of atopic eczema and other atopic diseases by odds ration regression analysis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 106:977–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawashima, T., E. Noguchi, T. Arinami, K. Yamakawa-Kobayashi, H. Nakagawa, F. Otsuka, and H. Hamaguchi. 1998. Linkage and association of an interleukin 4 gene polymorphism with atopic dermatitis in Japanese families. J. Med. Genet. 35:502–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Forrest, S., K. Dunn, K. Elliott, E. Fitzpatrick, J. Fullerton, M. McCarthy, J. Brown, D. Hill, and R. Williamson. 1999. Identifying genes predisposing to atopic eczema. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 104:1066–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Folster-Holst, R., H.W. Moises, L. Yang, W. Fritsch, J. Weissenbach, and E. Christophers. 1998. Linkage between atopy and the IgE high-affinity receptor gene at 11q13 in atopic dermatitis families. Hum. Genet. 102:236–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beyer, K., R. Nickel, L. Freidhoff, B. Bjorksten, S.K. Huang, K.C. Barnes, S. MacDonald, J. Forster, F. Zepp, V. Wahn, T.H. Beaty, D.G. Marsh, and U. Wahn. 2000. Association and linkage of atopic dermatitis with chromosome 13q12-14 and 5q31-33 markers. J. Invest. Dermatol. 115:906–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cookson, W.O., B. Ubhi, R. Lawrence, G.R. Abecasis, A.J. Walley, H.E. Cox, R. Coleman, N.I. Leaves, R.C. Trembath, M.F. Moffatt, and J.I. Harper. 2001. Genetic linkage of childhood atopic dermatitis to psoriasis susceptibility loci. Nat. Genet. 27:372–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mihm, M.C., N.A. Soter, H.F. Dvorak, and J.F. Austen. 1976. The structure of normal skin and the morphology of atopic eczema. J. Invest. Dermatol. 67:305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leung, D.Y.M., A.K. Bhan, E.E. Schneeberger, and R.S. Geha. 1983. Characterization of the mononuclear cell infiltrate in atopic dermatitis using monoclonal antibodies. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 71:47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hanifin, J.M., and G. Raika. 1980. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermatol. Venereol. 92:44–47. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nassif, A., S.C. Chan, F.J. Storrs, and J.M. Hanifin. 1994. Abnormal skin irritancy in atopic dermatitis and in atopy without dermatitis. Arch. Dermatol. 130:1402–1407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Foster, C.A., and A. Elbe. 1997. Lymphocyte subpopulations of the skin. Skin Immune System, 2nd ed. J.D. Bos, editor. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. 85–108.

- 61.Holtmeier, W., M. Pfander, A. Hennemann, T.M. Zollner, R. Kaufmann, and W.F. Caspary. 2001. The TCR-δ repertoire in normal human skin is restricted and distinct from the TCR-δ repertoire in the peripheral blood. J. Invest. Dermatol. 116:275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shires, J., E. Theodoridis, and A.C. Hayday. 2001. Biological insights into murine TCR γδ1 and TCR αβ1 intraepithelial lymphocytes provided by the serial analysis of gene expression. Immunity. 15:419–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Young, J.D., A.J. Lawrence, A.G. MacLean, B.P. Leung, I.B. McInnes, B. Canas, D.J.C. Pappin, and R.D. Stevenson. 1999. Thymosin β4 sulfoxide is an anti-inflammatory agent generated by monocytes in the presence of glucocorticoids. Nat. Med. 5:1424–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nakamura, M., R.M. Xavier, T. Tsunematsu, and Y. Tanigawa. 1995. Molecular cloning and characterization of a cDNA encoding nonspecific suppressor factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:3463–3467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Natori, K., M. Tamari, O. Watanabe, Y. Onouchi, Y. Shiomoto, S. Kubo, and Y. Nakamura. 1999. Mapping of a gene responsible for dermatitis in NOA (Naruto Research Institute Otsuka Atrichia) mice, an animal model of allergic dermatitis. J. Hum. Genet. 44:372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Watanabe, O., M. Tamari, K. Natori, Y. Onouchi, Y. Shiomoto, I. Hiraoka, and Y. Nakamura. 2001. Loci on murine chromosomes 7 and 13 that modify the phenotype of the NOA mouse, an animal model of atopic dermatitis. J. Hum. Genet. 46:221–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Daser, A., K. Koetz, N. Bätjer, M. Jung, F. Rüschendorf, M. Goltz, H. Ellerbrok, H. Renz, J. Walter, and M. Paulsen. 2000. Genetics of atopy in a mouse model: polymorphism of the IL-5 receptor a chain. Immunogenetics. 51:632–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barton, D., H. HogenEsche, and F. Weih. 2000. Mice lacking the transcription factor RelB develop T cell-dependent skin lesions similar to human atopic dermatitis. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:2323–2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yui, M.A., K. Muralidharan, B. Moreno-Altamirano, G. Perrin, K. Chestnut, and E.K. Wakeland. 1996. Production of congenic mouse strains carrying NOD-derived diabetogenic genetic intervals: an approach for the genetic dissection of complex traits. Mamm. Genome. 7:331–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McDuffie, M. 1998. Genetics of autoimmune diabetes in animal models. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 10:704–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]