Abstract

Ssk1p of Candida albicans is a putative response regulator protein of the Hog1 two-component signal transduction system. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the phosphorylation state of Ssk1p determines whether genes that promote the adaptation of cells to osmotic stress are activated. We have previously shown that C. albicans SSK1 does not complement the ssk1 mutant of S. cerevisiae and that the ssk1 mutant of C. albicans is not sensitive to sorbitol. In this study, we show that the C. albicans ssk1 mutant is sensitive to several oxidants, including hydrogen peroxide, t-butyl hydroperoxide, menadione, and potassium superoxide when each is incorporated in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) agar medium. We used DNA microarrays to identify genes whose regulation is affected by the ssk1 mutation. RNA from mutant cells (strain CSSK21) grown in YPD medium for 3 h at 30°C was reverse transcribed and then compared with similarly prepared RNA from wild-type cells (CAF2). We observed seven genes from mutant cells that were consistently up regulated (three-fold or greater compared to CAF2). In S. cerevisiae, three (AHP1, HSP12, and PYC2) of the seven genes that were up regulated provide cells with an adaptation function in response to oxidative stress; another gene (GPH1) is regulated under stress conditions by Hog1p. Three other genes that are up regulated encode a cell surface protein (FLO1), a mannosyl transferase (MNN4-4), and a putative two-component histidine kinase (CHK1) that regulates cell wall biosynthesis in C. albicans. Of the down-regulated genes, ALS1 is a known cell adhesin in C. albicans. Verification of the microarray data was obtained by reverse transcription-PCR for HSP12, AHP1, CHK1, PYC2, GPH1, ALS1, MNN4-4, and FLO1. To further determine the function of Ssk1p in the Hog1p signal transduction pathway in C. albicans, we used Western blot analysis to measure phosphorylation of Hog1p in the ssk1 mutant of C. albicans when grown under either osmotic or oxidative stress. We observed that Hog1p was phosphorylated in the ssk1 mutant of C. albicans when grown in a hyperosmotic medium but was not phosphorylated in the ssk1 mutant when the latter was grown in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. These data indicate that C. albicans utilizes the Ssk1p response regulator protein to adapt cells to oxidative stress, while its role in the adaptation to osmotic stress is less certain. Further, SSK1 appears to have a regulatory function in some aspects of cell wall biosynthesis. Thus, the functions of C. albicans SSK1 differ from those of S. cerevisiae SSK1.

Candidiasis is among the most common nosocomial diseases in the United States, occurring in ∼8 to 10% of high-risk patients (7, 8, 50). The disease has a high attributable mortality, most often because detection of the organism occurs late in the course of the disease or because therapy fails. Treatment with amphotericin B invariably results in toxicity to the patient, often necessitating withdrawal of the drug. The popularity of certain of the azole antifungals has been tempered by the development of resistance, especially among the nonalbicans species of Candida, such as Candida glabrata, Candida krusei, and Candida dubliniensis (18).

The virulence of Candida albicans appears to be multifactorial and includes the requirement for yeast-hyphal transition (morphogenesis), which is probably needed for invasion (9, 32), although direct persorption of yeast cells by mucosal cells has also been observed to precede blood-borne invasion (17). Virulence is also dependent upon the expression of cell surface adhesins that promote host cell recognition, as well as extracellular enzymes, such as phospholipases and proteases (9, 32).

While much is known about the virulence factors of C. albicans, its adaptation to stress conditions in the host, for example, oxidative stress following phagocytosis, is less understood. On the other hand, considerable effort has been devoted to characterizing the role of neutrophils (polymorphonuclear leukocytes [PMNs]) and macrophages, whose oxidative activities in protection against candidiasis are well known (43, 45-49, 52, 53). The importance of these cells in protection is reflected in the increased susceptibility of patients to candidiasis due to either defects in neutrophil function or reduction in their total number (neutropenia) (8). In vitro killing of C. albicans is increased if neutrophils are activated or if the organism is opsonized (46, 48). Wysong et al. (53) have demonstrated that a respiratory burst by neutrophils is Ca2+ dependent only if hyphae are opsonized. Neutrophil killing is less efficient in vitro if cell wall mannan is included in assays, but the active component of mannan that inhibits phagocytic killing is unknown (52). Reactive oxygen species (ROS), which appear to be candicidal alone or in combination, include hydrogen peroxide, superoxides, hydroxy radicals, and peroxynitrites (47). Nonoxidative components include defensins, small peptides with a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity, and other proteins associated with specific granules of neutrophils (48). Survival of the organism following phagocytosis by PMNs can occur, but the mechanism(s) that promotes its escape from oxidative killing is unknown.

One of the most important ways in which prokaryotes and lower eukaryotes, such as yeasts and other fungi, adapt to stress conditions is through two-component signal transduction (2, 5, 9, 10, 26, 28, 32). For example, the HOG (hyperosmotic glycerol) MAP kinase two-component signal pathway regulates growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae when cells are confronted with high-osmotic conditions (23, 37). The HOG MAP kinase pathway consists of a sensor, a transmembrane histidine kinase (Sln1p), a phosphohistidine intermediate protein (Ypd1p), and a cytoplasmic response regulator protein (Ssk1p). The phosphorylation state of Ssk1p determines whether the HOG MAP kinase pathway is activated, and glycerol synthesis is induced to adapt cells to osmotic stress. In S. cerevisiae, ssk1 mutants are deficient in growth on high-osmotic media, but the C. albicans SSK1 gene does not complement that mutant, indicating that perhaps the SSK1 of C. albicans is functionally divergent (14). In C. albicans, two-component homologues of the HOG pathway (SLN1, YPD1, SSK1, and HOG1) have been identified, and strains with SLN1, SSK1, and HOG1 deleted are defective in morphogenesis and are attenuated or avirulent (2, 3, 9, 14-16, 31, 54). Other histidine kinases found in C. albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus have been characterized, and their functions in morphogenesis, virulence, phenotypic switching, and cell wall biosynthesis have been established (1, 9-13, 31, 38, 40, 44, 54). However, the SLN1 and SSK1 mutants of C. albicans are only partially sensitive to hyperosmotic conditions (15, 31). Therefore, in this study we determined the sensitivity of the ssk1 mutant to a variety of stress conditions and inhibitors, including antifungal drugs; ROS, such as H2O2; and heat shock. We show that C. albicans SSK1 contributes to the adaptation of cells to oxidant stress. Also, microarray data support a role for SSK1 in the expression of cell wall structural or enzymatic proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and culture conditions.

The following C. albicans strains were used in this study: CAF2 (Δura3::imm434/URA3) (21), CSSK21 (Δura3::imm434/Δura3::imm434 Δssk1::hisG/Δssk1::hisG-URA3-hisG) (15), and CSSK23 (Δura3::imm434/Δura3::imm434 Δssk1::hisG SSK1::URA3-hisG) (15). Strains with genes deleted were constructed by the “urablaster” procedure (21) and have been described previously (15). All strains were maintained as frozen stocks and then cultured on YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% glucose, and 2% peptone) agar prior to use.

H2O2 and drug sensitivity assay.

The sensitivities of C. albicans strains CAF2, CSSK21, and CSSK23 (a gene-reconstituted strain) to oxidants were assayed by spotting dilutions of 5 × 101 to 5 × 105 cells (each in a total volume of 5 μl) from an overnight culture of yeast cells grown in YPD broth at 30°C onto YPD agar plates containing H2O2, menadione, t-butyl hydroperoxide, and KO2. The growth of each strain was examined after 48 h. The sensitivities of CSSK21, CSSK23, and CAF2 to antifungal drugs (miconazole, amphotericin B, nikkomycin Z, and caspofungin), calcofluor white, and caffeine were also evaluated.

Heat shock experiments.

Heat shock experiments were performed as described by others (33, 34). Exponentially grown cells were diluted to 104 to 107 per ml in phosphate-buffered saline-Tween buffer (0.05 M Tris, pH 7.5). At each dilution CAF2, CSSK21, and CSSK23 cells were incubated at either 30 or 42°C for 30 min; subsequently, dilutions were plated on YPD agar and cultured at 37°C. The number of CFU was then determined for each strain after 48 h of incubation.

Microarray analysis.

The C. albicans strains CAF2 and CSSK21 were inoculated into YPD medium and grown to a final concentration of 107 cells/ml, transferred to fresh YPD medium, grown at 30°C for 3 h to a constant optical density, and harvested by centrifugation. Total RNA was isolated according to the standard protocols (39, 41). Microarray analysis was repeated three times, each with different RNA extracts of cells; 1 mg of total RNA from each sample was used for poly(A) selection with an Oligotex kit from Qiagen (Chatsworth, Calif.).

Protocols and material source information for the microarray experiments were obtained from http://www.microarrays.org. DNA microarrays were fabricated at the University of California at San Francisco by spotting C. albicans (strain 5314) open reading frames (ORFs) that were derived from PCR products onto glass slides. Approximately 6,000 ORFs were screened. Four micrograms of mRNA from each strain was used for cDNA synthesis in the presence of amino-allyl dUTP. cDNA was then labeled with Cy5. For each experiment, 4 μg of reference mRNA (REF) derived from pooled CAF2 cells grown under a variety if growth conditions (D. Inglis and M. Lorenz, unpublished data) was labeled with Cy3. The Cy3- and Cy5-labeled samples were hybridized to the array in 50% formamide, 3× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), 0.4 μg of poly(A) DNA/μl, and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at 44°C. The microarrays were scanned with a GenePix 4000 microarray scanner (Axon Instruments Inc., Foster City, Calif.). Genes were assigned to the resulting microarray image with GenePix Pro version 3.0 software. Data were uploaded to the database program NOMAD (available at http://derislab.ucsf.edu/), which also normalized the data over the entire array. To analyze the mutant (CSSK21)/wild-type (CAF2) ratio, the values for cssk1/REF were divided by the values for CAF2/REF. The normalized ratios were filtered, and a self-organizing map for genes was created using the Cluster software program (19). The hierarchical cluster was viewed with TreeView (19). We used a ≥3-fold increase in the gene expression of strain CSSK21 to identify up-regulated genes compared to CAF2. Up-regulated genes were ≥4-fold in two experiments, 4-fold in three experiments, 3-fold in four experiments, and 3-fold in three experiments.

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted as described above from strains CAF2, CSSK21, and CSSK23 grown in YPD broth at 30°C for 3 h. Primers for all PCR amplifications are indicated in Table 1. Actin expression served as an internal control. RT-PCR was performed by using the Qiagen one-step PCR kit; 1 μg of total RNA was used for each PCR. All PCR products were resolved on 1% agarose gels, which were then scanned using an Alpha Imager 2000 (Alpha Innotech Corp.), imported as TIFF files, and evaluated for differential expression.

TABLE 1.

Primer sequences for RT-PCR experiments

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| HSP12 5′ | AGAGTCAATTTCTCTAGTAGAGGT |

| HSP12 3′ | AACTCCACTCACGTATTCAGCA |

| FLO1 5′ | AGTGCATTATTTGCTGCTACC |

| FLO1 3′ | AGCATGACAAGCATCATTATGA |

| MNN4-4 5′ | AGTTGAAAATCCAAGTGAAGGATACGG |

| MNN4-4 3′ | CAAAATCATGGAATCTTGTCAACGATCTC |

| CHK1 5′ | TCCCCAAATGCCTGAAATGGAC |

| CHK1 3′ | GCTACGATCACGGGTAACCAAC |

| AHP1 5′ | ATGTCATTTAAAGAAGGTTCC |

| AHP1 3′ | CTTGGCTAAAACAGCATCAAT |

| PYC2 5′ | GAAGGTGATGATATTGAAGAT |

| PYC2 3′ | GACCAACATAGAATCATAATG |

| ALS1 5′ | CAGGATACCCAACTTGGAAT |

| ALS1 3′ | CCAGTATTCAGTAGTAGTGA |

| GPH1 5′ | GGATTATCTTACCCCATCAACT |

| GPH1 3′ | GTCATTTGGATACAACACTGA |

| STL1 5′ | AGAACCACAACTGCTGGATTA |

| STL1 3′ | AGCTTCAGCAACAATAGCATC |

| ACTIN 5′ | GACGGTGAAGAAGTTGCTGC |

| ACTIN 3′ | CAAACCTAAATCAGCTGGTC |

Phosphorylation of Hog1p assay.

Yeast strains (CAF2 [SSK1 Ura+], CSSK21 [ssk1 Ura+ mutant], and CSSK23 [Ura3+; SSK1 reconstituted]) were grown in YPD medium supplemented with 20 mg of uridine/ml at 37°C. Overnight cultures were suspended in prewarmed YPD medium to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.05, and experiments were performed when the cultures reached an optical density at 600 nm of ∼1.0. Under these conditions, the culture was challenged with 1.5 M NaCl or 10 mM hydrogen peroxide (final concentrations). Samples were taken after the addition of each stimulus at different times (0 to 60 min), and cell extracts were obtained using glass beads in a fast-prep cell breaker as previously indicated (2, 30). Similar amounts of proteins, as determined by absorbance at 280 nm and SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis-Coomasie Blue staining, were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nylon membranes (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) following standard procedures (2). The blots were first probed with an ScHog1p polyclonal antibody (anti-ScHog1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Subsequently, the blots were stripped and reacted with a phospho-p38 MAP kinase (Thr180/Tyr182) 28B10 monoclonal antibody (anti-TGYP; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). Blots with anti-ScHog1p or anti-TGYP were developed according to the conditions recommended by the manufacturer using the Hybond ECL kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

RESULTS

Sensitivity of the ssk1 mutant of C. albicans to inhibitors and heat shock.

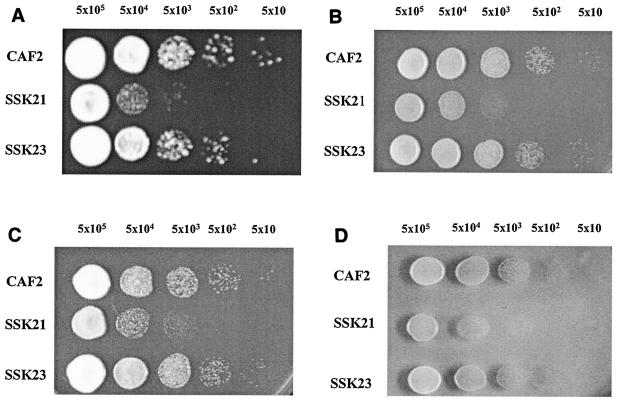

The reference strain CAF2 (SSK1 URA3), the mutant strain CSSK21 (ssk1 URA3), and the reconstituted strain CSSK23 (SSK1 URA3) were incubated at 30°C for 48 h on YPD agar containing 0 to 8 mM H2O2 and 0 to 1.0 mM menadione (which generates superoxide), t-butyl hydroperoxide, or KO2. We found that, compared to CAF2 and CSSK23, strain CSSK21 was sensitive to H2O2 at concentrations as low as 5 mM, as well as 0.1 mM menadione, t-butyl hydroperoxide, or KO2 (Fig. 1). The inhibition of CSSK21 was also observed by incubating cells with the same concentrations of oxidants described above for 1 h and then culturing the cells on YPD agar (data not shown). No differences between the sensitivities of strain CSSK21 and those of strains CSSK23 and CAF2 were observed with amphotericin B, miconazole, nikkomycin Z, calcoflour white, caspofungin, or caffeine (data not shown). Heat shock experiments were conducted with CAF2, CSSK21, and CSSK23. We observed that only the viability of the ssk1 mutant strain (CSSK21) was reduced when cells were incubated at 42°C for 30 min and then cultured at 37°C. The reduction in growth was >2 log units in CSSK21 (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Growth of CAF2 (wt), SSK21 (ssk1/ssk1), and SSK23 (ssk1/SSK1) at 30°C for 48 h on YPD agar containing (A) 0.1 mM menadione, (B) 1.0 mM KO2, (C) 1 mM t-butyl hydroperoxide, and (D) 5 mM H2O2. Five microliters of cell dilutions (5 × 105 to 5 × 101 cells) was spotted on YPD agar containing each compound.

Gene array studies.

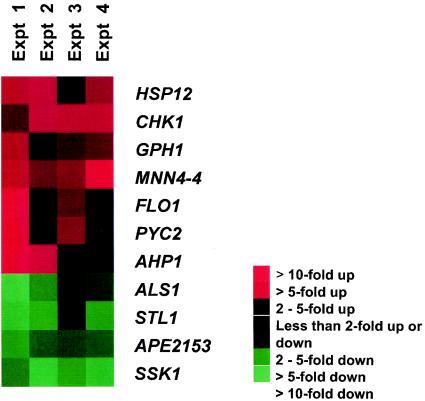

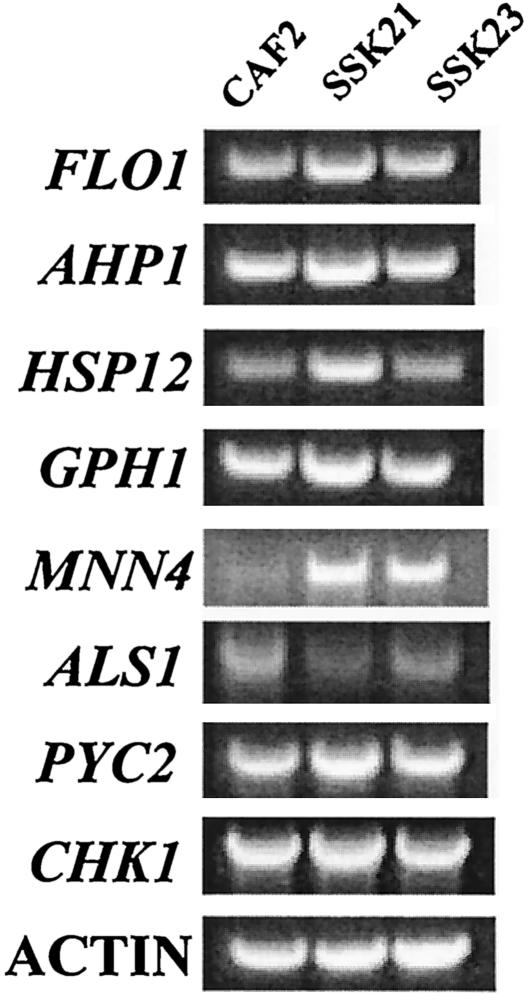

In order to determine the effect of the SSK1 deletion on gene expression, we performed DNA microarray analysis experiments using RNA preparations of the ssk1 mutant and wild-type cells (CAF2). Cells of each strain were grown at 30°C for 3 h in YPD broth, and RNA was isolated, reverse transcribed, and hybridized to SC5314 DNA ORFs. Analysis was done with a total of four RNA preparations from four cell preparations. The genes with the greatest amount of up regulation appear red, and those most down regulated appear green. A total of seven genes were up regulated at least three- to fourfold for all experiments with the ssk1 mutant (Fig. 2 and Table 2). Annotation of the up-regulated genes was performed using the Saccharomyces genome database (www.yeastgenome.org) or, when possible, the C. albicans genolist.pasteur.fr/CandidaDB website. We determined that three of the seven genes that were up regulated provide stress adaptation functions in S. cerevisiae. Those genes included AHP1 (4.89-fold), HSP12 (3.8-fold), and PYC2 (3.6-fold). A fourth up-regulated gene (GPH1) encodes a glycogen phosphorylase, which is regulated via the Hog1p pathway during osmotic shock (3.2-fold) (51). The three other up-regulated genes, CHK1 (4.37-fold), FLO1 (4.4-fold), and MNN4-4 (4.44-fold), either encode cell wall biosynthetic enzymes (MNN4-4), regulate cell wall biosynthesis (CHK1) (27), or encode a cell surface protein (FLO1). As for the genes encoding a cell wall function, we observed that ALS1 is down regulated (0.35-fold) (Fig. 2 and Table 2). The genes, whose expression was altered in strain CSSK21 were subjected to RT-PCR from similarly grown cells and compared to CAF2 and CSSK23 (Fig. 3). Actin was used as an internal loading control. Compared to CAF2 and CSSK23, we observed that expression levels of HSP12, AHP1, MNN-4, and FLO1 were greater in strain CSSK21, while ALS1 was down regulated. Levels of PYC2, CHK1, and GPH1 were slightly but consistently higher than those of CAF2 and CSSK23. By Northern analysis, the up regulation of GPH1 and PYC2 in the mutant was more readily noted (data not shown). As expected, SSK1 was weakly detected in mutant cells, while differences among strains were not apparent by RT-PCR for STL1 and APE2153 (not shown). RT-PCR was also done with SSK23, the gene-reconstituted strain (Fig. 3). Expression in SSK23 was either similar to that in CAF2 cells or, in the case of MNN4, up regulated, as with strain SSK21.

FIG. 2.

Microarray analysis of genes up (red) and down (green) regulated in strain SSK21 compared to wild-type (CAF2) cells. A total of four microarray experiments (Expt) were done.

TABLE 2.

Summary of microarray data showing the up-regulated and down-regulated genes of the ssk1 mutant.

| Gene name | Stanford name | Average median ratioa | Descriptionb |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSP12 | orf6.1668 | 3.81 (8) | Heat shock protein; oxidative stress (12kDa) |

| CHK1 | orf6.7978 | 4.37 (19) | Histidine kinase |

| GPH1 | orf6.7947 | 3.22 (12) | Glycogen phosphorylase regulated by Hog1p |

| MNN4-4 | orf6.4127 | 4.44 (11) | Mannosyl transferase; multiple-gene family member |

| FLO1 | orf6.3288 | 4.40 (4) | Flocculin; cell surface protein |

| PYC2 | orf6.2989 | 3.61 (4) | Pyruvate carboxylase; NADPH regeneration |

| AHP1 | orf6.6590 | 4.89 (4) | Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase |

| ALS1 | orf6.2112c | 0.35 (8) | Agglutinin-like cell surface protein |

| STL1 | orf6.1416 | 0.50 (12) | Hexose transporter of the major facilitator family |

| SSK1 | orf6.7978 | 0.16 (4) | Response regulator, two-component phosphorelay |

The number of spots used for calculating the average median ratio is in parentheses.

Putative gene function(s) in S. cerevisiae or C. albicans.

Partial ORF sequence.

FIG. 3.

RT-PCR of selected genes in CAF2, SSK23, and SSK21. For each experiment, β-actin was used as an internal control. RT-PCR gels were scanned, and the images were stored as TIFF files. A representative RT-PCR analysis is shown. Results were similar for three analyses of each gene.

Phosphorylation of Hog1p.

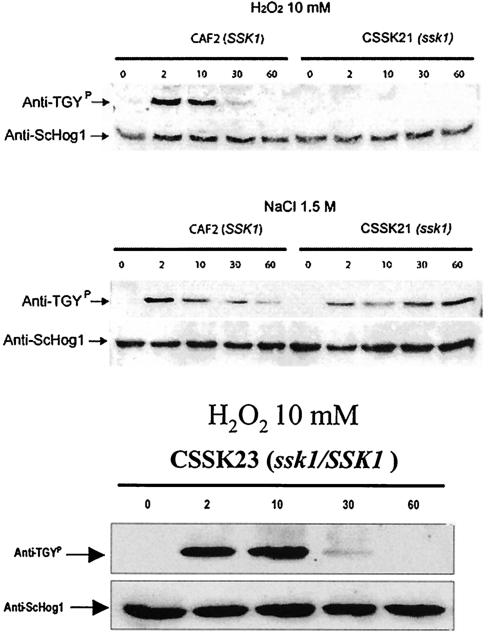

In S. cerevisiae, phosphorylation of Hog1p by Ssk1p is critical in the adaptation of cells to osmotic stress. Thus, we were interested in the relationship of Ssk1p to Hog1p in C. albicans under conditions of osmotic or oxidative stress. Previously, it was shown that strain CSSK21 is insensitive to 1.0 M sorbitol and 2 mM H2O2 (15). To determine the relationship of Ssk1p and Hog1p, we used Western blot analysis with an antibody that recognizes phosphorylated Hog1p (anti-TGYP) (Fig. 4) (2). Cells of strains CAF2 and CSSK21 were grown in the presence or absence of 10 mM H2O2 or 1.5 M NaCl for 0 to 60 min. Extracts of cells at each time point were prepared, electrophoresed, transferred to nitrocellulose filters, and reacted with anti-ScHog1p, an antibody that recognizes both the S. cerevisiae and C. albicans Hog1p proteins regardless of the phosphorylation state. A reactive band of 38 kDa was observed in both types of stress treatments and in both CAF2 and CSSK21 at all time points (Fig. 4A). The specificity of the antibody was shown in previous studies, since a hog1 mutant of C. albicans lacked this reactive protein (2). Subsequently, the Western blot was stripped (with 2% SDS at 70°C, then with 62.5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8; 20°C], and finally with 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol) and reacted with anti-TGYP, which recognizes the phosphorylated Hog1p (Fig. 4A). In CAF2, Hog1p was phosphorylated within 2 min in cells treated with either NaCl or H2O2. By 10 min, the signal decreased in wild-type cells treated with NaCl, but the signal remained strongly positive in cells treated with H2O2 at 10 min; subsequently, the phosphorylation signal decreased in both treatments. No phosphorylation of Hog1p was observed in the SSK21 mutant treated with H2O2 (Fig. 4A, top), but phosphorylation of Hog1p did occur in the ssk1 mutant exposed to NaCl. Thus, SSK1 is required for phosphorylation of Hog1p in cells exposed to H2O2 but is not required for cells grown in high concentrations of NaCl. Interestingly, the temporal phosphorylation of Hog1p in the CSSK21 mutant grown in 1.5 M NaCl remains strongly positive after 60 min, but not in cells of CAF2. The phosphorylation of CSSK23 was also studied under the same conditions (Fig. 4B). The introduction of SSK1 in this strain restored Hog1p phosphorylation when the cells were oxidatively stressed. We did not examine the phosphorylation of Hog1p in cells stressed with NaCl, since that signal was already apparent in the ssk1 mutant (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis. (A) Strains CAF2 (SSK1) and CSSK21 (ssk1) were grown in either 10 mM H2O2 (upper blots) or 1.5 M sodium chloride (lower blots). At the indicated times (in minutes, above the lanes), samples were obtained and Western blots were performed using either an anti-S. cerevisiae Hog1p antibody (lower reactive band) or an anti-TGY antibody (upper band) that recognizes the phosphorylated p38 protein of mammalian cells (Hog1p is a homologue of this protein). (B) Phosphorylation of Hog1p in SSK23 cells that were oxidant stressed as described for panel A. Restoration of the phosphorylation is observed in the SSK1 gene-reconstituted strain.

DISCUSSION

The adaptation of bacteria, archaea, lower eukaryotes, and higher plants, but not human cells, to stress conditions is regulated through two-component signal transduction (5, 26, 37, 42). The Hog1 pathway of S. cerevisiae is the most studied of the two-component systems in fungi (23, 37). In C. albicans, homologues of the HOG pathway are found (Sln1p, Ypd1p, and Ssk1p), but the Sln1p and Ssk1p proteins seem to have minor roles in adapting cells to osmostress, as SLN1 and SSK1 mutants are only partially sensitive (15, 31). Likewise, C. albicans SSK1 does not complement the ssk1 mutant of S. cerevisiae (14). Recent data suggest that the Hog1p MAP kinase is essential for adaptation of C. albicans to oxidative stress due to ROS, such as oxidants (menadione, hydrogen peroxide, and KO2), and UV light (2). It follows that the two-component proteins that regulate the phosphorylation of Hog1p may also be involved in the adaptation of cells to oxidant stress. Since adaptation to high-osmotic conditions appears to be a minor function (if any) of the C. albicans Ssk1p, our preliminary experiments focused upon the sensitivity of strain CSSK21 (ssk1/ssk1) to other stress conditions. We tested a variety of antifungal compounds and oxidants in order to assess the sensitivity of the mutant strain. Strain CSSK21 was not sensitive to nikkomycin Z, miconazole, amphotericin B, caffeine, caspofungin, or calcofluor white. However, the strain was sensitive to hydrogen peroxide at a concentration of 5 mM and to other oxidants, which explains why in previous studies carried out using ≤2 mM H2O2, no effect was observed (15).

The sensitivity of CSSK21 to peroxide stress was supported by microarray data. Three of the seven genes that were up regulated threefold or greater in strain CSSK21 are among those whose functions in S. cerevisiae are associated partially or totally with adaptation to stress conditions, including oxidative stress. AHP1 of S. cerevisiae encodes one of several oxidoreductases whose function is to maintain cells in a reduced state (redox potential) during oxidative metabolism (22, 36). The oxidoreductases are small, heat-stable proteins that contain two conserved cysteine residues in their active sites and are of two types, the thioredoxins and glutathione-glutaredoxins (22, 36). While they are highly conserved with overlapping functions, differences exist between the two types of oxidoreductases. For example, the thioredoxins utilize NADPH as an H donor, while the glutaredoxins use reduced glutathione (22). Importantly, the expression of thioredoxin-related genes, such as AHP1, is regulated by the transcription factors YAP-1p and Skn7p (22). The latter transcription factor is a response regulator two-component signal protein in S. cerevisiae. Thus, a consequence of cell growth and oxidative metabolism in S. cerevisiae is the generation of ROS that are highly toxic to cells unless proteins such as Ahp1p are produced. While the oxidoreductases of C. albicans have not been characterized, it would appear that C. albicans processes oxidative stress in a manner that is somewhat different from the S. cerevisiae process (20). The organism also produces an adaptive response that protects it from lethal effects of a subsequent challenge (24). In addition to AHP1, HSP12, and PYC2, up regulation of GPH1 (glycogen synthesis) was observed; Gph1p is regulated by Hog1p in osmotically stressed cells (51). Recent data also point to an increase in trehalose production during oxidative stress (4), although our array analysis did not indicate changes in the expression of genes involved in trehalose biosynthesis. Finally, CSSK1 appears to regulate the expression of certain cell wall proteins (Mnn4p, Als1p1, and Flo1p [25, 35]) and a two-component histidine kinase, CHK1, that regulates cell wall synthesis (27). Up regulation of MNN4 in S. cerevisiae during stress responses has been demonstrated (35). The array data for up-regulated genes obtained with the ssk1 mutant were verified by RT-PCR. Importantly, expression of the adhesin ALS1 (25) is down regulated. This observation is correlated with a previous study that showed a reduced adherence to human esophageal cells by the ssk1 mutant of C. albicans (6, 29).

The relationship of Ssk1p and Hog1p was established through Western blot assays. We used anti-ScHog1p antibody to identify in Western blotting the C. albicans Hog1p. Following exposure of the wild type (CAF2) and the ssk1 mutant to hydrogen peroxide, phosphorylation of Hog1p, as determined using the anti-TGY antibody, occurred only in CAF2 cells (2). Thus, Ssk1p is used for phosphorylation of Hog1p, at least in peroxide-stressed cells. On the other hand, Hog1p is phosphorylated in both wild-type and ssk1 mutant cells in the presence of 1.5 M NaCl. Thus, it would appear that in C. albicans, Ssk1p may or may not interact with Hog1p during osmotic stress; however, other proteins carry out this activity in the absence of Ssk1p.

In summary, Ssk1p in C. albicans represents at least one of the signal proteins that adapt cells to peroxide stress. This activity appears to be at least partially mediated through the HOG MAP kinase pathway. Importantly, we show that Ssk1p is not essential for adaptation to osmotic stress, unlike S. cerevisiae Ssk1p, which is essential. We have recently determined that the ssk1 mutant is also more readily killed by human PMNs (unpublished data), suggesting that its avirulence in a murine model of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis may in part be associated with this phenotype (15). Down regulation of ALS1 in the cssk1 mutant also suggests a reason for its reduced adherence to human esophageal cells (6, 29). Since two-component signal proteins are found only in fungi, prokaryotic organisms, and plants, they may be suitable as targets for the development of new antifungals (5, 26). Among the fungal pathogens of humans, other histidine kinases have been identified in A. fumigatus (FOS1) (30) and C. albicans (COS1/NIK1 and CHK1), and mutants of each are attenuated or avirulent (54). Importantly, while strains with single genes deleted are still viable, deletions of both sln1 and a second histidine kinase gene (cos1/nik1) are lethal (54). Thus, an anti-two-component drug should be relatively broad spectrum in its activity and fungicidal.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIAID AI47047 and NIAID AI 43465) to R.C. The research was also supported by grant BIO-0729 and a grant from the Grupo Estratégico de la Communidad de Madrid to J.P. The microarray work in the Johnson laboratory was supported by NIH grant R01AI49187.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alex, L. A., C. Korch, C. P. Selitrennikof, and M. I. Simon. 1998. COS1, a two-component histidine kinase that is involved in hyphal development in the opportunistic pathogen, Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7069-7073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso-Monge, R., F. Navarro-García, E. Roman, A. I. Negredo, B. Eisman, C. Nombela, and J. Pla. 2003. The Hog1 MAP kinase is essential in the oxidative stress response and chlamydospore formation in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 2:351-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alonso-Monge, R., F. Navarro-García, G. Molero, R. Diez-Orejas, M. Gustin, J. Pla, M. Sánchez, and C. Nombela. 1999. Role of mitogen-activated protein kinase Hog1p in morphogenesis and virulence of Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 181:3058-3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvarez-Peral, F. J., O. Zaragoza, Y. Pedreño, and J.-C. Argüelles. 2002. Protective role of trehalose during severe oxidative stress caused by hydrogen peroxide and the adaptive oxidative stress response in Candida albicans. Microbiology 148:2599-2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrett, J. F., and J. A. Hoch. 1998. Two-component signal transduction as a target for microbial anti-infective therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1529-1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernhardt, J., D. Herman, M. Sheridan, and R. Calderone. 2001. Adherence and invasion studies of Candida albicans strains utilizing in vitro models of esophageal candidiasis. J. Infect. Dis. 184:1170-1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black, C. A., F. M. Eyers, A. Russel, M. L. Dunkley, R. L. Clancy, and K. W. Beagley. 1998. Acute neutropenia decreases inflammation associated with murine vaginal candidiasis but has no effect on the course of infection. Infect. Immun. 66:1273-1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodey, C. A., M. Buckley, Y. S. Sathe, and E. J. Freirich. 1986. Quantitative relationship between circulating leukocytes and infections in patients with acute leukemia. Ann. Intern. Med. 64:328-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calderone, R. A., and W. A. Fonzi. 2001. Virulence factors of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol. 9:327-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calera, J. A., and R. A. Calderone. 1999. Histidine kinase, two-component signal transduction proteins of Candidia albicans and the pathogenesis of candidosis. Mycoses 42(Suppl.):49-53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calera, J. A., G. Cho, and R. A. Calderone. 1998. Identification of a putative histidine kinase two-component phosphorelay gene (CaCHK1) in Candida albicans. Yeast 14:665-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calera, J. A., and R. A. Calderone. 1999. Flocculation of hyphae is associated with a deletion in the putative CaHK1 two-component histidine kinase gene from Candida albicans. Microbiology 145:1431-1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calera, J. A. X.-J. Zhao, M. Sheridan, and R. A. Calderone. 1999. Avirulence of Candida albicans CaHK1 mutants in a murine model of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis. Infect. Immun. 67:4280-4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calera, J. A., and R. A. Calderone. 1999. Identification of a putative response regulator, two-component phosphorelay gene (CaSSK1) from Candida albicans. Yeast 15:1243-1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calera, J. A., X.-J. Zhao, and R. A. Calderone. 2000. Defective hyphal formation and avirulence caused by a deletion of the CSSK1 response regulator gene in Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 68:518-525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calera, J. A., D. Herman, and R. A. Calderone. 2000. Identification of YPD1, a gene of Candida albicans which encodes a two-component phospho-histidine intermediate protein. Yeast 16:1053-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cole, G. T., K. R. Seshan, K. T. Lynn, and M. Franco. 1993. Gastrointestinal candidiasis: histopathology of Candida-host interactions in a murine model. Mycol. Res. 97:385-408. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cowen, L. E., A. Nantel, M. S. Whiteway, D. Y. Thomas, D. C. Tessler, L. M. Kohn, and J. B. Anderson. 2002. Population genomics of drug resistance on Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:9284-9289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisen, M. B., P. T. Spellman, P. O. Brown, and D. Botstein. 1998. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:14863-14868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enjalbert, B., A. Nantel, and M. Whiteway. 2003. Stress-induced gene expression in Candida albicans: absence of a general stress response. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:1460-1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fonzi, W. A., and M. Y. Irwin. 1993. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics 134:717-728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grant, C. M. 2001. Role of the glutathione/glutaredoxin and thioredoxin systems in yeast growth and response to stress conditions. Mol. Microbiol. 39:533-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hohmann, S. 2002. Osmotic stress signaling and osmoadaptation in yeasts. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:300-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jamieson, D. J., W. S. S Duncan, and E. C. Terriere. 1996. Analysis of the adaptive oxidative response of Candida albicans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 138:83-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kapteyn, J. C., L. L. Hoyer, J. E. Hecht, W. H. Muller, A. Andel, A. J. Verkleij, M. Makarow, H. Van Den Ende, and F. M. Klis. 2000. The cell wall architecture of Candida albicans wild-type cells and cell wall-deficient mutants. Mol. Microbiol. 35:601-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koretke, K. K., A. N. Lupas, P. V. Warren, M. Rosenberg, and J. R. Brown. 2000. Evolution of two-component signal transduction. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17:1956-1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruppa, M., T. Goins, D. Williams, D. Li, N. Chauhan, P. Singh, J. Cutler, and R. Calderone. 2003. FEMS Yeast Res. 3:289-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lengeler, K. B., R. C. Davidson, C. D'Souza, T. Harashima, W.-C. Shen, P. Wang, X. Pan, M. Waugh, and J. Heitman. 2000. Signal transduction cascades regulating fungal development and virulence. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:746-785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li, D., J. Bernhardt, and R. Calderone. 2002. Temporal expression of the Candida albicans genes CHK1 and CSSK1: adherence and morphogenesis in a model of reconstituted human esophageal epithelial candidiasis. Infect. Immun. 70:1558-1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin, H., J. M. Rodriguez-Pachon, C. Ruiz, C. Nombela, and M. Molina. 2000. Regulatory mechanisms for modulation of signalling through the cell integrity Slt2-mediated pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 275:1511-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagahashi, S., T. Mio, N. Ono, T. Yamada-Okabe, M. Arisawa, H. Bussey, and H. Yamada-Okabe. 1998. Isolation of CaSLN1 and CaNIK1, the genes for osmosensing histidine kinase homologues, from the pathogenic fungus, Candida albicans. Microbiology 144:425-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Navarro-Garcia, F., M. Sanchez, C. Nombela, and J. Pla. 2001. Virulence genes in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25:245-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Navarro-Garcia, F., R. Alonso-Monge, H. Rico, J. Pla, R. Sentandreu, and C. Nombela. 1998. A role for the MAP kinase gene MKC1 in cell wall construction and morphological transitions in Candida albicans. Microbiology 144:411-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Navarro-Garcia, F., M. Sanchez, J. Pla, and C. Nombela. 1995. Functional characterisitics of the MKC1 gene of Candida albicans, which encodes a mitogen-activated protein kinase homolog related to cell integrity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:2197-2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Odami, T., Y.-I. Shimma, X.-H. Wang, and Y. Jigami. 1997. Mannosyl phosphate transfer to cell wall mannan is regulated by the transcriptional level of the MNN4 gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 420:186-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park, S. G., M.-K. Cha, W. Jeong, and I.-H. Kim. 2000. Distinct physiological functions of thiol peroxidase isoenzymes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 275:5723-5732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Posas, F., S. M. Wurgler-Murphy, T. Maeda, E. A. Witten, T. C. Thai, and H. Saito. 1996. Yeast HOG1 MAP kinase cascade is regulated by a multistep phosphorelay mechanism in the SLN1-YPD1-SSK1 two-component osmosensor. Cell 86:865-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pott, G. B., T. K. Miller, J. A. Bartlett, J. S. Palas, and C. P. Selitrennikoff. 2000. The isolation of FOS-1, a gene encoding a putative two-component histidine kinase from Aspergillus fumigatus. Fungal Genet. Biol. 31:55-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 40.Selitrennikoff, C. P., L. Alex, T. K. Miller, K. V. Clemons, M. I. Simon, and D. A. Stevens. 2001. COS-1, a putative two-component histidine kinase of Candida albicans, is an in vivo virulence factor. Med. Mycol. 39:69-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherman, F., G. R. Fink, and J. B. Hicks. 1986. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 42.Singh, K. K. 2000. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sln1p-Ssk1p two-component system mediates response to oxidative stress in an oxidant-specific fashion. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 29:1043-1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smail, E. H., B. N. Cronstein, T. Meshulam, A. L. Esposito, R. W. Ruggeri, and R. D. Diamond. 1992. In vitro, Candida albicans releases the immune modulator adenosine and a second, high molecular weight agent that blocks neutrophil killing. J. Immunol. 148:3588-3595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Srikantha, T., L. Tsai, K. Daniels, L. Enger, K. Highley, and D. R. Soll. 1998. The two-component hybrid kinase regulator CaNIK1 of Candida albicans. Microbiology 144:2715-2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stein, D. K., S. E. Malawista, G. Van Blaricom, D. Wysong, and R. D. Diamond. 1995. Cytoplasts generate oxidants but require added neutrophil granule constituents for fungicidal activity against Candida albicans hyphae. J. Infect. Dis. 172:511-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stevenhagen, A., and R. van Furth. 1993. Interferon-gamma activates the oxidative killing of Candida albicans by human granulocytes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 91:170-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vasquez-Torres, A., J. Jones-Carson, and E. Balish. 1996. Peroxynitrite contributes to the candidacidal activity of nitric oxide-producing macrophages. Infect. Immun. 64:3127-3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vecchiarelli, A., C. Monari, F. Baldelli, D. Pietrella, C. Retini, C. Tascini, D. Francisci, and F. Bistoni. 1995. Beneficial effect of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on fungicidal activity of polymorphonuclear leukocytes from patients with AIDS. J. Infect. Dis. 171:1448-1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Voganatsi, A., A. Panyutich, K. T. Miyasaki, and R. K. Murthy. 2001. Mechanism of extracellular release of neutrophil calprotectin complex. J. Leukoc. Biol. 70:130-134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wenzel, R. P. 1995. Nosocomial candidiasis: risk factors and attributable mortality. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20:1531-1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wohler Sunnarborg, S., S. P Miller, I. Unnikrishnan, and D. C. LaPorte. 2001. Expression of the yeast glycogen phosphorylase gene is regulated by stress-response elements and by the HOG MAP kinase pathway. Yeast 18:1505-1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wright, C. D., J. U. Bowie, G. R. Gray, and R. D. Nelson. 1983. Candidacidal activity of myeloperoxidase: mechanisms of inhibitory influence of soluble cell wall mannan. Infect. Immun. 42:76-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wysong, D. R., C. A. Lyman, and R. D. Diamond. 1989. Independence of neutrophil respiratory burst oxidant generation from the early cytosolic calcium response after stimulation with unopsonized Candida albicans hyphae. Infect. Immun. 57:1499-1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamada-Okabe, T., T. Mio, T. Ono, Y. Kashima, M. Arisawa, and Y. Yamada-Okabe. 1999. Roles of three histidine kinase genes in hyphal development and virulence of the pathogenic fungus, Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 181:7243-7247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]