Abstract

Mast cells were depleted in the peritoneal cavity of WBB6F1-tg/tg mice that did not express a transcription factor, MITF. When acute bacterial peritonitis was induced in WBB6F1-+/+, WBB6F1-W/W v, and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice, the proportion of surviving WBB6F1-+/+ mice was significantly higher than that of surviving WBB6F1-W/W v or WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. The poor survival of WBB6F1-W/W v and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice was attributed to the deficient influx of neutrophils into the peritoneal cavity. The injection of cultured mast cells (CMCs) derived from WBB6F1-+/+ mice normalized the neutrophil influx and reduced survival rate in WBB6F1-W/W v mice, but not in WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. This was not attributable to a defect of neutrophils because injection of TNF-α increased the neutrophil influx and survival rate in both WBB6F1-W/W v and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. Although WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs injection normalized the number of mast cells in both the peritoneal cavity and mesentery of WBB6F1-W/W v mice, it normalized the number of mast cells only in the peritoneal cavity of WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. Mast cells within the mesentery or mast cells in the vicinity of blood vessels appeared to play an important role against the acute bacterial peritonitis. WBB6F1-tg/tg mice may be useful for studying the effect of anatomical distribution of mast cells on their antiseptic function.

Keywords: mast cell, innate immunity, MITF, acute bacterial peritonitis, TNF-α

Introduction

The mouse mi locus encodes a transcription factor belonging to the basic-helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper family (hereafter, microphthalmia transcription factor [MITF]*) (1, 2). The mutant mi allele produces an abnormal MITF, in which 1 out of 4 consecutive arginines is deleted in the basic domain (hereafter, mi-MITF) (1, 3, 4). The mi-MITF is defective in DNA binding, nuclear translocation and transactivation of target genes (5–13). On the other hand, the mutant tg allele is a transgene insertion mutation in the 5′ flanking region of the MITF gene (1, 14). Although the coding region of the MITF gene was normal in C57BL/6 (B6)-tg/tg mice, no significant amount of MITF was detected in cultured mast cells (CMCs) derived from the spleen of B6-tg/tg mice (15).

Both B6-mi/mi and B6-tg/tg mice show microphthalmia, lack of melanocytes, and decrease of skin mast cells (16). B6-mi/mi mice show osteopetrosis, but B6-tg/tg mice do not (17). Most B6-mi/mi mice die on weaning due to the failure of teeth eruption caused by the osteopetrosis, whereas most B6-tg/tg mice survived to adulthood. The number of mast cells in skin tissues was comparable between B6-mi/mi and B6-tg/tg mice (one third that of B6-+/+ mice; reference 18). However, the decrease of heparin content in skin mast cells was observed only in B6-mi/mi mice (19).

Although mast cells develop before birth in the skin tissue of normal B6-+/+ mice, they develop after weaning in tissues other than the skin of B6-+/+ mice (20). As adult B6-tg/tg mice were easily obtained, we attempted to investigate development of mast cells in tissues other than the skin of B6-tg/tg mice. We found the lack of mast cells in the peritoneal cavity of adult B6-tg/tg mice.

Involvement of mast cells in the innate immunity has been studied using WBB6F1-W/W v mice (21, 22). When acute bacterial peritonitis was induced, the proportion of surviving WBB6F1-W/W v mice was significantly lower than that of WBB6F1-+/+ mice (21, 22). The prior intraperitoneal transplantation of CMCs derived from WBB6F1-+/+ mice normalized the reduced proportion of surviving WBB6F1-W/W v mice (21, 22). In the present study, we examined whether comparable results were obtained in WBB6F1-tg/tg mice, which lacked peritoneal mast cells as WBB6F1-W/W v mice. Although the proportion of surviving WBB6F1-tg/tg mice was reduced as WBB6F1-W/W v mice, the reduced survival rate was not normalized by the prior transplantation of WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs. We investigated the mechanism of this unexpected result and found that the anatomical distribution of the transplanted CMCs was different between WBB6F1-tg/tg and WBB6F1-W/W v mice.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

The original stock of B6-Mi wh/+ mice was purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. The B6-mi ew/+ and B6-mi ce/+ mice were given by Dr. M.L. Lamoreux (Texas A&M University, College Station, TX). The original stock of VGA-9-tg/tg mice, in which the mouse vasopressin-Escherichia coli β-galactosidase transgene was integrated at the 5′ flanking region of the MITF gene (1), was given by H. Arnheiter (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). B6-Mi wh/+, B6-mi ew/+, and B6-mi ce/+ mice were maintained by consecutive backcrosses to our own inbred B6 colony (more than 18 generations at the time of the present experiment). Homozygous mice were produced by crosses between female and male heterozygotes of each genotype, and selected by their white coat color. The VGA-9-tg/tg mice were maintained by repeated backcrosses to our own inbred B6 and WB colonies more than 12 generations. B6-tg/+ mice were crossed together, and WB-tg/+ mice were crossed to B6-tg/+ mice. The resulting B6-tg/tg and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice were selected by their white coat color. WBB6F1- W/W v and WBB6F1-+/+ mice were purchased from the Japan SLC.

Estimation of Mast Cell Numbers in the Peritoneal Cavity and Tissues.

To harvest peritoneal cells, 2 ml of Tyrode's buffer (23) containing 0.1% gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich) was injected into the peritoneal cavity, and the abdomen was massaged gently for 30 s. The peritoneal cavity was carefully opened, and the fluid containing peritoneal cells was aspirated with a Pasteur pipette. After centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended with the Tyrode's buffer (1.0 ml), and was divided into two parts. One part (0.8 ml) was used for the direct counting of mast cells as described by Gilbert and Ornstein (24). The cell suspension was centrifuged again, suspended in the Tyrode's buffer (0.1 ml), and diluted with 0.4 ml saline containing 0.1% EDTA-Na (solution A). Then 0.45 ml of a solution containing 0.076% cetylpyridinium chloride, 0.7% lanthanum chloride-6H2O, 0.9% NaCl, 0.21% Tween 20 (Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.143% alcian blue 8GX (Eastman Kodak Co.; solution B) were added to the cell suspension. After 1 min of gentle agitation, 0.05 ml of 1 N HCl (solution C) was added, and the mixture was gently agitated. The cell suspension was centrifuged, resuspended in 0.05 ml of the mixture of the Tyrode's buffer and solutions A, B, and C (Tyrode:A:B:C = 2:8:9:1). After 20 min, alcian blue–positive cells were counted with a standard hemocytometer. Numbers of mast cells per mouse were calculated.

Another part (0.2 ml) of the peritoneal cell suspension was centrifuged at 600 rpm for 5 min with a Cytospin 2 centrifuge (Shandon) to attach cells to a microscope slide. The cytospin preparations were fixed in Carnoy's solution, and stained with alcian blue and nuclear fast red. Proportion of alcian blue-positive cells in 1,000 nucleated peritoneal cells was determined.

Mast cell numbers in the mesentery, glandular stomach, spleen, and lung were estimated as described previously (18, 20, 25).

CMCs.

PWM-stimulated spleen cell–conditioned medium (PWM-SCM) was prepared according to the method described by Nakahata et al. (26). Mice of B6-+/+, B6-tg/tg, and WBB6F1-+/+ were used to obtain CMCs. Mice were killed by decapitation after ether anesthesia, and spleens were removed. Spleen cells were cultured in α-MEM (ICN Biomedicals) supplemented with 10% PWM-SCM and 10% FCS (Nippon Bio-supp Center). Half of the medium was replaced every 7 d. More than 95% of cells were CMCs 4 wk after the initiation of the culture.

Intraperitoneal Injection of CMCs.

CMCs (1.0 × 106) derived from B6-+/+, B6-tg/tg, or WBB6F1-+/+ mice were suspended in 0.5 ml of α-MEM, and were injected into the peritoneal cavity of the recipient mice. At the intervals indicated, peritoneal cells were harvested as described above. Proportions of mast cells in 1,000 peritoneal cells were determined as mentioned above.

Caecal Ligation and Puncture.

Caecal ligation and puncture (CLP) was performed as described previously by Echtenacher et al. (21) with slight modifications. In brief, the mice were anesthetized by sevofrane (Maruishi Pharmaceuticals). A 1-cm midline incision on the anterior abdominal wall was made. The cecum was exposed and filled with feces by squeezing stool back from the ascending colon. The cecum was 50% ligated below the ileocecal valve and then punctured using a 0.65 mm needle followed by gentle squeezing of the cecum. Mice were examined every day for survival rate.

Neutrophil Counts in Peritoneal Exudates.

Peritoneal exudates were collected from mice and total cell numbers were counted. The cytospin preparation of peritoneal cells was made as described previously. The cells were stained with May-Grunwald-Giemsa. Proportions of neutrophils in peritoneal cells were determined. Then the number of neutrophils was calculated.

Injection of TNF-α.

Acute bacterial peritonitis was induced by CLP in WBB6F1-tg/tg and WBB6F1-W/W v mice. Immediately after CLP, a single intraperitoneal injection of murine TNF-α (PeproTech; reference 21) or control diluents (0.5 ml PBS per mouse) was done. Numbers of neutrophils were counted 3 h after CLP. Survival rate was also determined.

Intravenous Injection.

CMCs (1.0 × 106) derived from WBB6F1-+/+ mice were suspended in 0.2 ml of α-MEM, and were injected into the tail vein of the recipient mice. Proportions of mast cells in 1,000 peritoneal cells and number of mast cells in the mesentery, glandular stomach, and spleen were determined 5 wk after the injection.

Mast Cell Staining with Berberine Sulfate.

The cytospin preparation of peritoneal cells was made as described previously. After fixation with Carnoy's fluid, the cells were stained with berberine sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich), as described by Enerback (27).

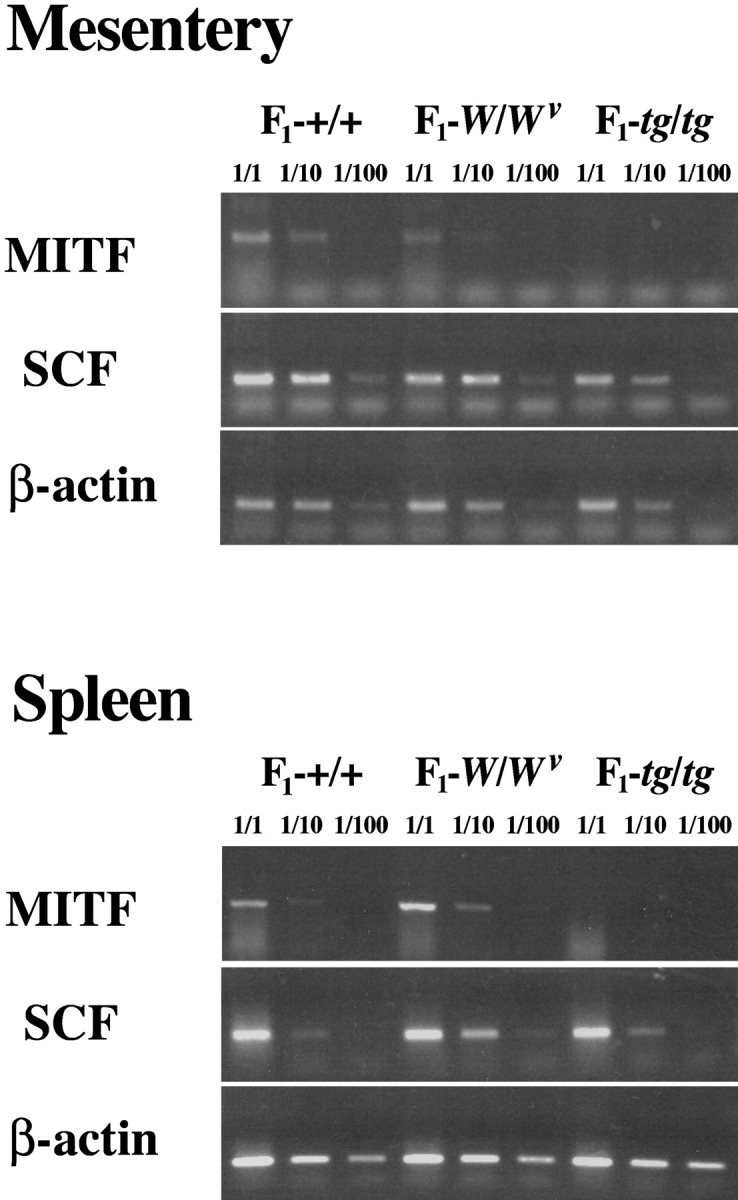

Semiquantitative RT-PCR Analysis.

4 μg of total RNAs were extracted from the mesentery and spleen of WBB6F1-+/+, WBB6F1-W/W v, and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. The extracted RNAs were subjected to reverse transcription by Superscript (Invitrogen Corp.), and the single strand cDNAs were obtained. 1, 0.1, or 0.01 μl of the reaction mixture was added to 25 μl of PCR mixture containing 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) and 25 pmol of each of the primers. PCR was performed to amplify the fragment of the MITF, stem cell factor (SCF), and β-actin genes using the following primers; 5′-ACAGAGTCTGAAGCAAGAGCA and 5′-GGTGATGGTACCGTCCGTGAG for MITF, 5′-AAGACTCGGGCCTACAATGGACAGCCATGG and 5′-CAATGTTGATACGTCCACAA-TTAC for SCF, and 5′-TAAAGACCTCTATGCCAACAC and 5′-CTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCACAT for β-actin.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analysis of most data was performed using the Student's t test. Statistical analysis of the survival rate was done using the log rank test.

Results

Mast Cell Deficiency of tg/tg Mice.

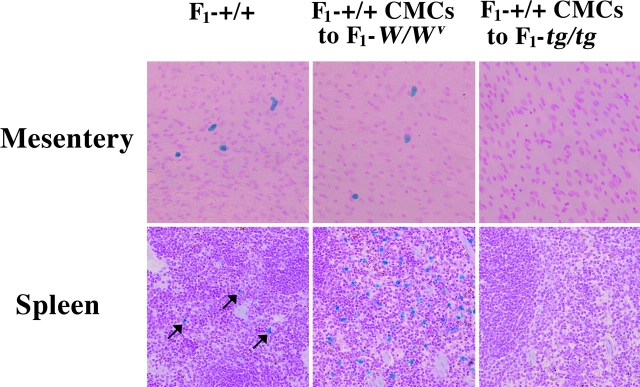

The number of mast cells was examined at various ages in the peritoneal cavity and glandular stomach of B6-+/+ and B6-tg/tg mice. In B6-+/+ mice, mast cells appeared in the peritoneal cavity 6 wk after birth and in the glandular stomach 4 wk after birth (Fig. 1) . The number of mast cells increased thereafter. On the other hand, in B6-tg/tg mice, no detectable number of mast cells appeared in either peritoneal cavity or glandular stomach at any ages examined (Fig. 1). We also examined whether mast cells appeared in spleens and lungs of B6-tg/tg mice at 10 wk of age. Mast cells were not detectable in histological sections of lungs and spleens of B6-tg/tg mice (unpublished data).

Figure 1.

The number of mast cells in the peritoneal cavity (A) and glandular stomach (B) of B6-+/+ and B6-tg/tg mice. The number of mast cells was examined at various times after birth. At each time point, the mean values of 6 to 8 mice were plotted with bars indicating SE.

We further investigated the mast cell deficiency in the peritoneal cavity of other MITF mutants. The number of peritoneal mast cells shown in Fig. 1 was obtained by the direct counting of peritoneal cells with the hemocytometer. In addition to the direct counting, another method was used to identify mast cells more precisely. Cytospin preparations of peritoneal cell suspensions were made, and proportions of mast cells in 1,000 nucleated peritoneal cells were counted. A few mast cells were recognized in the cytospin preparations of peritoneal cells obtained from B6-tg/tg, B6-mi ew/miew, B6-mi ce/mice, and B6-Mi wh/Miwh mice, but the mean number of mast cells did not exceed 0.1 per 1,000 nucleated peritoneal cells in each mutant mouse (Table I). The results obtained by these two methods were consistent and showed the apparent deficiency of mast cells in the peritoneal cavity of B6-mi ew/miew, B6-mi ce/mice, and B6-Mi wh/Miwh mice as in the case of B6-tg/tg mice (Table I).

Table I.

Mast Cell Deficiency in the Peritoneal Cavity of Various MITF Mutant Mice of B6 Strain Estimated by Two Methods

| Direct count

|

Proportion in cytospin preparation |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Micea | No. of mice |

No. of mast cells/ mouse (× 103)b |

No. of mast cells/ 103 peritoneal cellsc |

| B6-+/+ | 8 | 20.0 ± 2.5 | 29.5 ± 2.8 |

| B6-tg/tg | 9 | NDd | <0.1 |

| B6-miew/miew | 8 | NDd | <0.1 |

| B6-mice/mice | 10 | NDd | <0.1 |

| B6-Miwh/Miwh | 8 | NDd | <0.1 |

The number of mast cells was examined at 10 wk of age.

After harvesting peritoneal cells, cells were divided into two parts. One part was stained with alcian blue in suspension, and the positive cells were counted with a hemocytometer. Mean and SE are shown.

Cytospin preparation was made from another part and was stained with alcian blue and nuclear fast red. Proportion of alcian blue-positive cells to 103 nucleated peritoneal cells was determined. Mean and SE are shown.

Not detectable.

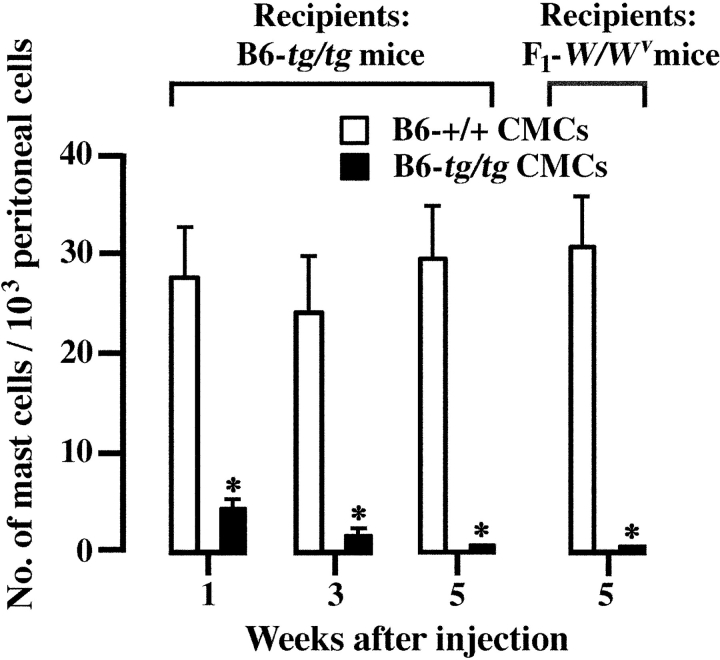

We injected B6-+/+ or B6-tg/tg CMCs into the peritoneal cavity of B6-tg/tg mice. At various weeks after injection, we examined the proportions of mast cells in 1,000 nucleated peritoneal cells. The B6-+/+ CMCs survived 5 wk after the injection, but B6-tg/tg CMCs did not (Fig. 2) . We also used WBB6F1-W/W v mice as recipients because they are used as a standard of mast cell–deficient animals (28, 29). B6-tg/tg CMCs did not survive in the peritoneal cavity of WBB6F1-W/W v mice, either (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Survival of transplanted CMCs in the peritoneal cavity of B6-tg/tg and WBB6F1-W/W v mice. B6-+/+ or B6-tg/tg CMCs (1.0 × 106) were injected into the peritoneal cavity of the recipient mice. At 1, 3, or 5 wk after the injection, the proportion of mast cells in 1,000 nucleated peritoneal cells was determined. The mean values of five mice were shown with bars indicating SE. In some cases, SE was too small to be shown by bars. *P < 0.01 by t test when compared with the value obtained after the injection of B6-+/+ CMCs.

Mortality from Acute Bacterial Peritonitis.

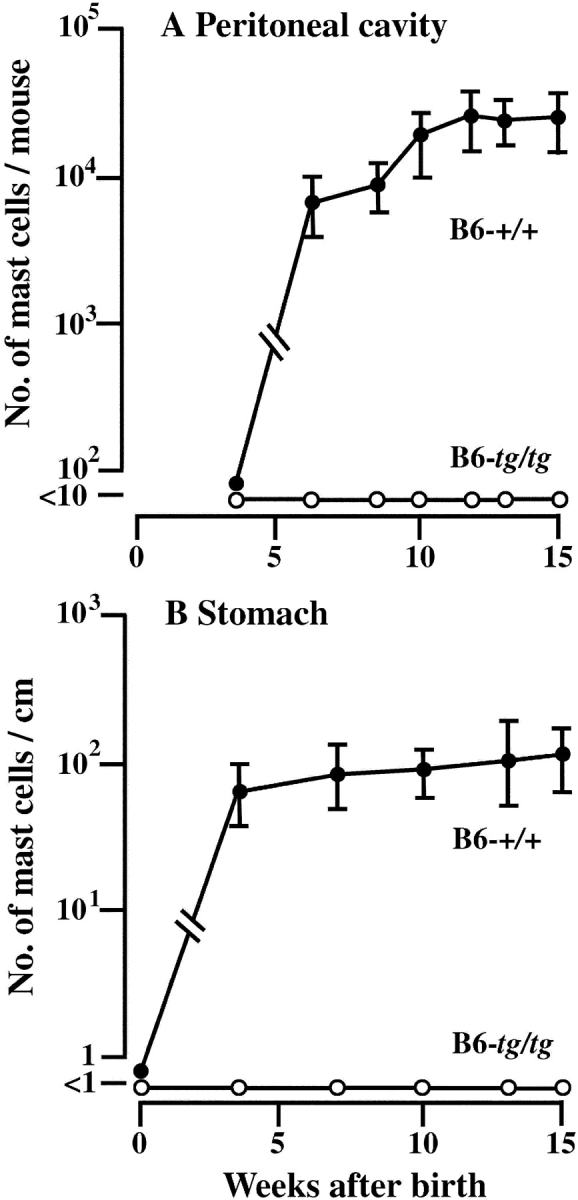

As mast cell deficiency was observed in the peritoneal cavity of B6-tg/tg mice, we induced the acute bacterial peritonitis by CLP and compared the survival rate between B6-tg/tg and B6-+/+ mice. The proportion of surviving B6-tg/tg mice was significantly lower than that of surviving B6-+/+ mice (Fig. 3) . Then we investigated the effect of the prior transplantation of B6-+/+ CMCs because Echtenacher et al. (21) reported that the reduced survival rate of WBB6F1-W/W v mice after CLP is normalized by the prior transplantation of WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs. Unexpectedly, the prior transplantation of B6-+/+ CMCs (2.0 × 106) did not increase the survival rate of B6-tg/tg mice after CLP (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of +/+ CMC injection on the survival of B6-tg/tg mice. Peritonitis was induced by CLP in B6-+/+ mice, B6-tg/tg mice, and B6-tg/tg mice which received the prior intraperitoneal injection of B6-+/+ CMCs 5 wk before CLP. Number of mice is shown in parentheses. The proportion of survival was compared by log rank test.

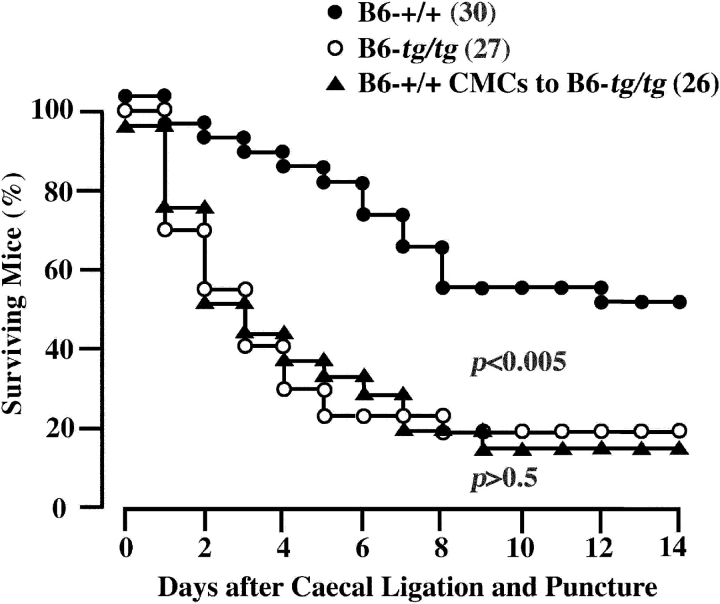

There was a possibility that the difference of mouse genetic background (B6 versus WBB6F1) may cause this unexpected result. We produced WBB6F1-tg/tg mice, and induced the acute bacterial peritonitis in intact WBB6F1-tg/tg mice and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice which had received the prior transplantation of WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs. As a control, we also induced the bacterial peritonitis in intact WBB6F1-W/W v mice and WBB6F1-W/W v mice which had received the prior tansplantation of WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs. WBB6F1-W/W v mice gave a comparable result that had been reported by Echtenacher et al. (21; Fig. 4 A). In contrast, the result obtained by WBB6F1-tg/tg mice was consistent with the result of B6-tg/tg mice (compare Figs. 3 and 4 B).

Figure 4.

Effect of injection of WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs on survival of WBB6F1-W/W v and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. Peritonitis was induced by CLP. (A) Proportions of surviving WBB6F1-+/+ mice, WBB6F1-W/W v mice, and WBB6F1-W/W v mice that had received the prior intraperitoneal injection of WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs 5 wk before CLP. (B) Proportions of surviving WBB6F1-+/+ mice, WBB6F1-tg/tg mice, and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice that had received the prior intraperitoneal injection of WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs 5 wk before CLP. The number of mice is shown in parentheses. The proportion of survival was compared by log rank test.

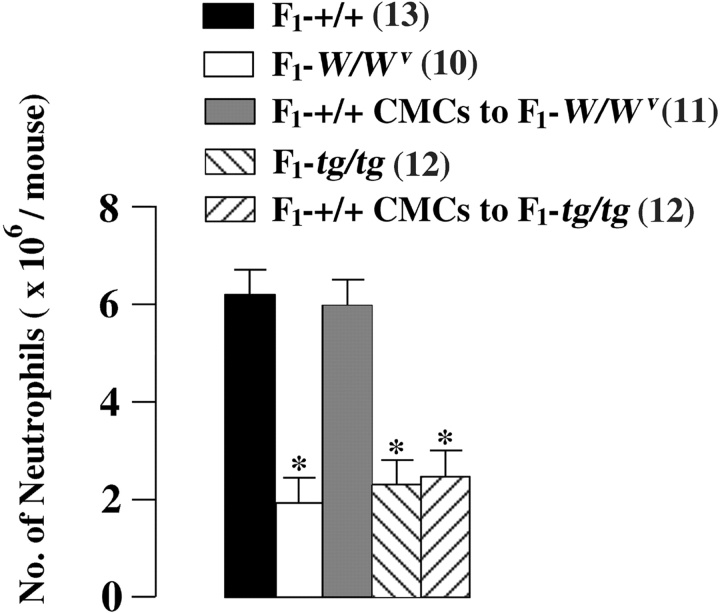

The number of neutrophils was counted in the peritoneal cavity of WBB6F1-+/+, WBB6F1-W/W v, and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice 3 h after CLP. The number of neutrophils was significantly lower in the peritoneal cavity of WBB6F1-W/W v mice and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice than in the peritoneal cavity of WBB6F1-+/+ mice (Fig. 5) . The prior transplantation of WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs normalized the neutrophil response in WBB6F1-W/W v mice but not in WBB6F1-tg/tg mice (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Number of infiltrating neutrophils in the peritoneal cavity of WBB6F1-+/+ mice, WBB6F1-W/W v, mice, and WBB6F1-W/W v mice that had received the prior intraperitoneal injection of WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs 5 wk before CLP, WBB6F1-tg/tg mice and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice that had received the prior intraperitoneal injection of WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs 5 wk before CLP. Numbers of mice are shown in parentheses. *P < 0.01 by t test, when compared with the value observed in WBB6F1-+/+ mice.

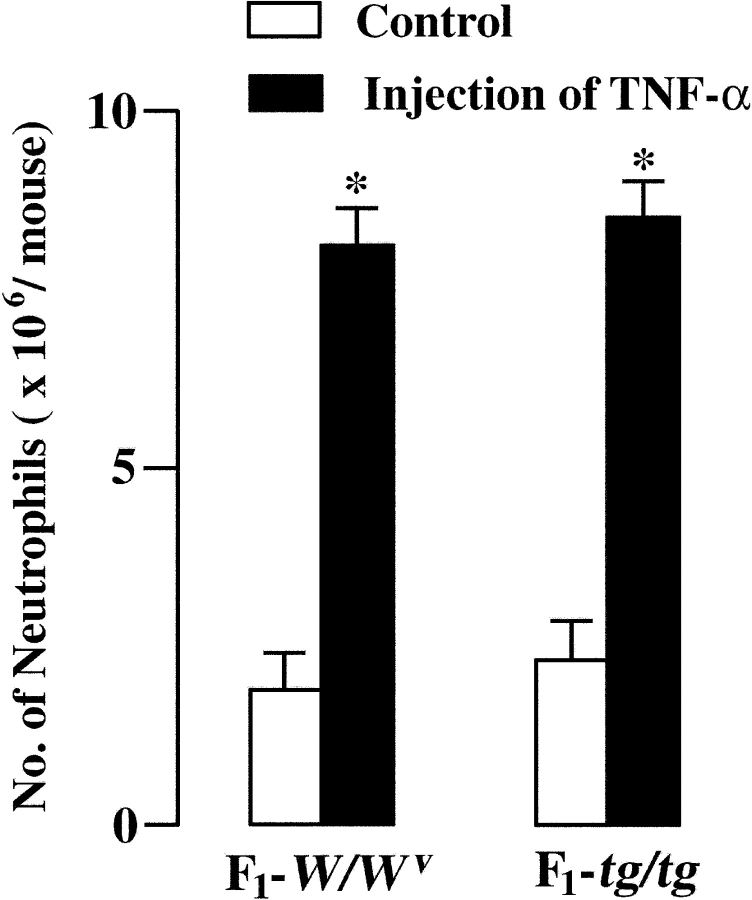

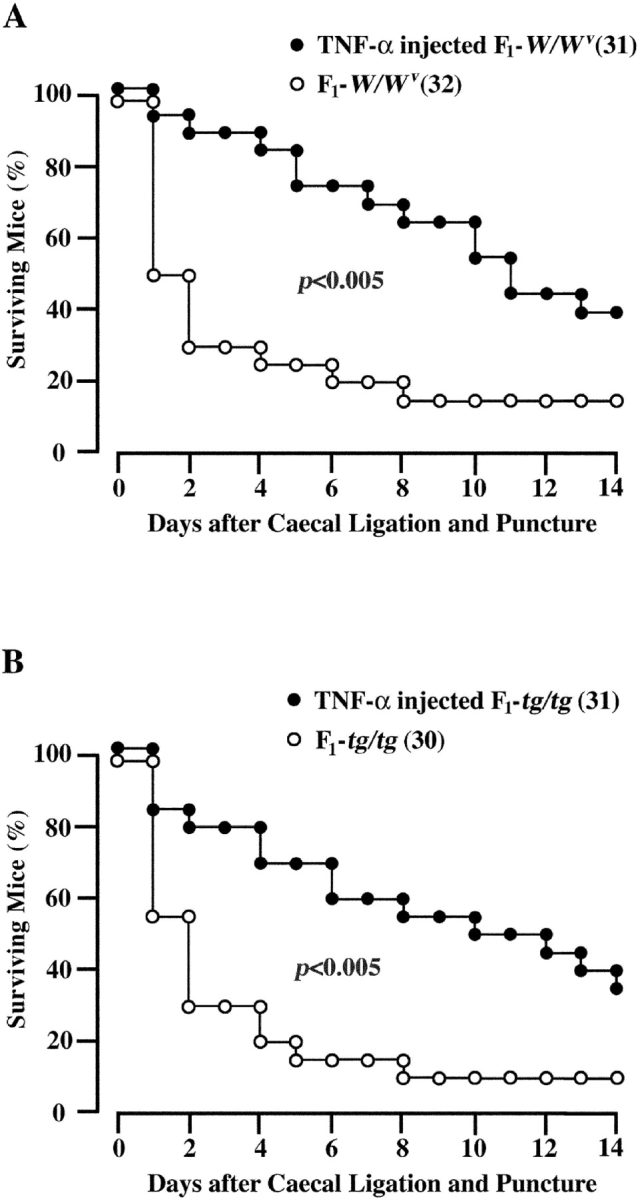

There was a possibility that the migration activity of neutrophils of WBB6F1-tg/tg mice was defective. The effect of intraperitoneal injection of TNF-α on the number of infiltrating neutrophils was compared between WBB6F1-W/W v and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. TNF-α was injected intraperitoneally immediately after CLP. The number of infiltrating neutrophils after CLP was increased by the intraperitoneal injection of TNF-α not only in WBB6F1-W/W v mice but also in WBB6F1-tg/tg mice (Fig. 6) . The values of both mice were comparable. The survival rate was also increased by the injection of TNF-α in both WBB6F1-W/W v (Fig. 7 A) and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice (Fig. 7 B).

Figure 6.

Effect of TNF-α injection on the number of infiltrating neutrophils in the peritoneal cavity of WBB6F1-W/W v and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. Mice received TNF-α injection immediately after CLP and the number of neutrophils was counted 3 h after CLP. Mean ± SE of 5 to 7 mice are shown. *P < 0.01 by t test when compared with the value of control mice of the same genotype.

Figure 7.

Effect of TNF-α injection on the proportions of surviving WBB6F1-W/W v (A) and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice (B). The experimental condition was same as the experiment shown in Fig. 6. Numbers of mice are shown in parentheses. The proportion of survival was compared by log rank test.

Different Effect of CMC Transplantation between tg/tg and W/Wv Mice.

Presence of mast cells in the peritoneal cavity of B6-tg/tg mice 5 wk after intraperitoneal transplantation of B6-+/+ CMCs was shown in Fig. 2.

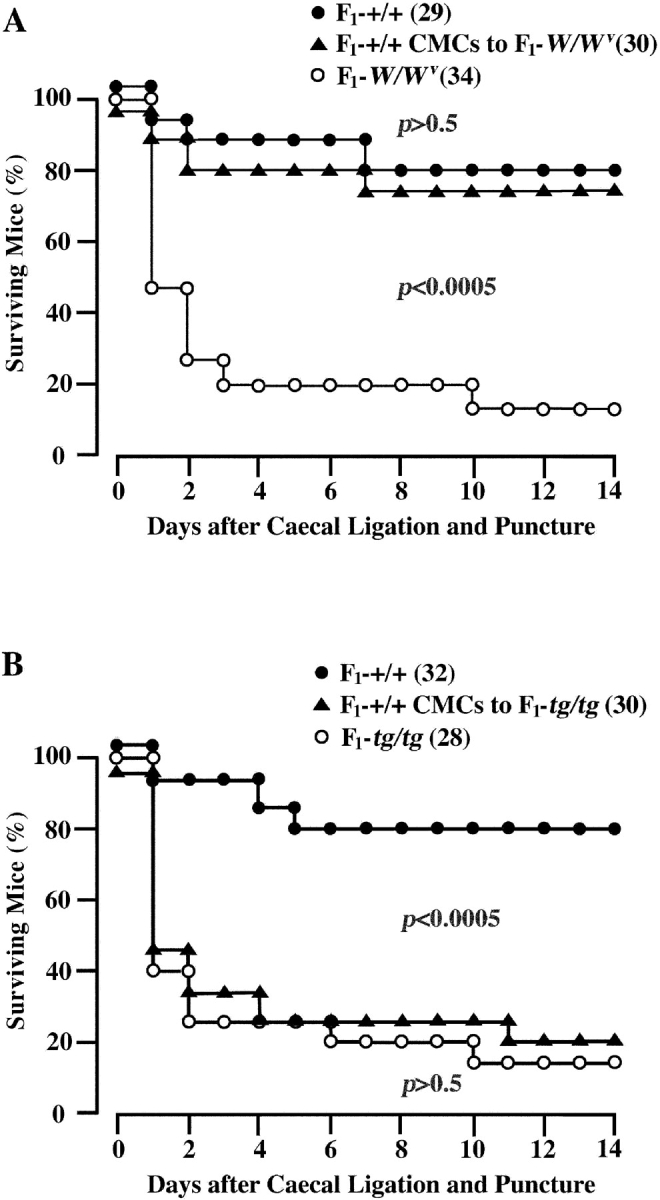

The prior intraperitoneal transplantation of WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs normalized the neutrophil response and survival rate of WBB6F1-W/W v mice, but did not affect the neutrophil response and survival rate of WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. There was a possibility that the intraperitoneal transplantation of WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs had different effects between WBB6F1-W/W v and WBB6F1-tg/tg recipients. We compared the effect of the intraperitoneal transplantation between WBB6F1-W/W v and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. The number of mast cells in the peritoneal cavity was comparable between WBB6F1-W/W v and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice (Table II). Although WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs were not stained with berberine sulfate before the transplantation, mast cells recovered from the peritoneal cavity of either WBB6F1-W/W v or WBB6F1-tg/tg mice were stained with berberine sulfate (unpublished data), suggesting the content of heparin (27). The number of mast cells in the stretch preparation of the mesentery of WBB6F1-W/W v mice was normalized by the intraperitoneal transplantation of WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs (Table II and Fig. 8) . However, the same procedure did not result in development of mast cells in the mesentery of WBB6F1-tg/tg mice (Table II and Fig. 8).

Table II.

Number of Mast Cells in the Peritoneal Cavity and Mesentery of WBB6F1-W/Wv and WBB6F1-tg/tg Mice 5 wk after Intraperitoneal Injection of 106 WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs

| No. of mast cellsa

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Miceb | Peritoneal cavity (no./103 peritoneal cells)c |

Mesentery (no./mm2)d |

| F1-+/+ mice (8) | 31.0 ± 4.4 | 10.4 ± 2.8 |

| F1-W/W v mice (8) | <0.1 | NDe |

| F1-W/W

v mice that received F1-+/+ CMCs (8) |

35.8 ± 4.2 | 11.4 ± 1.8 |

| F1-tg/tg mice (11) | <0.1 | NDe |

| F1-tg/tg mice that received F1-+/+ CMCs (8) |

36.1 ± 5.6 | NDe |

Mean and SE are shown.

Number of mice is shown in parentheses.

Cytospin preparation was made from harvested peritoneal cells and was stained with alcian blue and nuclear fast red. Proportion of alcian blue-positive cells to 103 nucleated peritoneal cells was determined.

Number of mast cells per mm2 of stretched mesentery.

Not detectable.

Figure 8.

Nonappearance of mast cells in the mesentery and spleen of a WBB6F1-tg/tg mouse 5 wk after intraperitoneal transplantation of WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs. The mesentery and spleen of an intact WBB6F1-+/+ mouse and those of a WBB6F1-W/W v mouse which had received the intraperitoneal transplantation of WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs are also shown. Arrows in the spleen section of the WBB6F1-+/+ mouse show mast cells. The number of mast cells in the spleen of the WBB6F1-W/W v mouse was remarkably larger than that observed in the intact WBB6F1-+/+ mouse. Mast cells were stained with alcian blue and nuclear fast red. Original magnification, ×200.

Intraperitoneal transplantation of WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs resulted in development of mast cells in the mesentery of WBB6F1-W/W v mice but not in the mesentery of WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. Next, WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs were transplanted intravenously into WBB6F1-W/W v and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. As already reported, mast cells appeared in the peritoneal cavity, mesentery, stomach, and spleen of WBB6F1-W/W v mice (25), but did not in the corresponding tissues of WBB6F1-tg/tg mice (Table III and Fig. 8).

Table III.

Number of Mast Cells 5 wk after Intravenous Injection of 106 WBB6F1-+/+ CMCsc

| No. of mast cellsa

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donors | Recipientsb | Peritoneal cavity |

Mesenteryd | Stomache | Spleenf |

| F1-+/+ | F1-W/Wv (9) | 5.0 ± 1.0 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 178 ± 10 | 41 ± 3 |

| F1-+/+ | F1-tg/tg (9) | <0.1g | NDh | NDh | NDh |

Mean and SE are shown.

Number of recipients is shown in parentheses.

Cytospin preparation was made from harvested peritoneal cells and was stained with alcian blue and nuclear fast red. Proportion of alcian blue-positive cells to 103 nucleated peritoneal cells was determined.

Number of mast cells per mm2 of stretched mesentery.

Number of mast cells per cm of stomach section.

Number of mast cells per mm2 of spleen section.

P < 0.01 by t test when compared to the value of WBB6F1-W/W v mice which received WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs.

Not detectable.

The deficient development of mast cells in the mesentery was confirmed in B6-tg/tg mice after intraperitoneal transplantation of B6-+/+ CMCs (Table IV). Since there is a possibility that the transgene insertion in the tg allele affects the mi gene as well as neighboring genes which may function in the mesentery, we also transplanted B6-+/+ CMCs into the peritoneal cavity of B6-mi ew/miew mice. Although the phenotype of B6-mi ew/miew mice is not distinguishable from that of B6-tg/tg mice, the mi ew allele encodes mutant MITF with a large deletion of the basic domain (30). In spite of the difference, the intraperitoneal injection of B6-+/+ CMCs gave similar results in both B6-tg/tg and B6-mi ew/miew mice. Mast cells appeared in the peritoneal cavity but did not in the mesentery (Table IV).

Table IV.

Number of Mast Cells in the Peritoneal Cavity and Mesentery of B6-tg/tg and B6-miew/miew Mice 5 wk after Intraperitoneal Injection of 106 B6-+/+ CMCs

| No. of mast cellsa

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Miceb | Peritoneal cavity (no./103 peritoneal cells)c |

Mesentery (no./mm2)d |

| B6-+/+ Mice (8)e | 29.5 ± 2.8 | 8.4 ± 1.4 |

| B6-tg/tg mice (9)e | <0.1 | NDf |

| B6-tg/tg mice that received B6-+/+ CMCs (12)g |

29.7 ± 2.9 | NDf |

| B6-miew/miew mice (8)e | <0.1 | NDf |

| B6-miew/miew mice that received B6-+/+ CMCs (8) |

30.5 ± 2.8 | NDf |

Mean and SE are shown.

Number of mice is shown in parentheses.

Cytospin preparation was made from harvested peritoneal cells and was stained with alcian blue and nuclear fast red. Proportion of alcian blue-positive cells to 103 nucleated peritoneal cells was determined.

Number of mast cells per mm2 of stretched mesentery.

Data of the same mice are shown in Table I.

Not detectable.

Data of the same mice are shown in Fig. 2.

There is a possibility that tissues of mice of tg/tg genotype have a defect in microenvironment that is necessary for the migration and settlement of normal CMCs. First, we examined whether MITF was expressed in the mesentery and spleen of WBB6F1-+/+, WBB6F1-W/W v, and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. The expression of MITF mRNA was detectable in the mesentery and spleen of intact WBB6F1-+/+ and WBB6F1-W/W v mice, but did not in those tissues of intact WBB6F1-tg/tg mice (Fig. 9) . As the defect of WBB6F1-tg/tg mice was somewhat reminiscent of the defect of WBB6F1-Sl/Sl d mice that do not produce a ligand of c-kit receptor tyrosine kinase (SCF; references 31–34), we next examined the expression of SCF in the mesentery and spleen of intact WBB6F1-+/+, WBB6F1-W/W v, and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. In contrast to our expectation, the amount of SCF mRNA was comparable among tissues of all the WBB6F1-+/+, WBB6F1-W/W v, and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Expression levels of MITF and SCF mRNAs in the mesentery and spleen of intact WBB6F1-+/+, WBB6F1-W/W v, and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. Semiquantitative RT-PCR was done to compare the expression levels of MITF, SCF, and β-actin mRNAs. RNA extracted from the mesentery and spleen of intact WBB6F1-+/+, WBB6F1-W/W v, and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice were subjected to RT-PCR.

Discussion

Mast cells were practically absent in the peritoneal cavity of B6-tg/tg, B6-mi ew/miew, B6-mi ce/mice, and B6-Mi wh/Miwh mice. Since mast cells develop in the peritoneal cavity 6 wk after birth even in B6-+/+ mice and since most of B6-mi/mi mice die on weaning (4 wk after birth), it is rather difficult to evaluate mast cell number in the peritoneal cavity of B6-mi/mi mice. However, mast cells are probably absent in the peritoneal cavity of B6-mi/mi mice as well, because all examined phenotypes of B6-mi/mi mice were the most severe among all MITF mutant mice (11, 17, 30, 35, 36). The mi and Mi wh mutant alleles encode MITFs with deletion or alteration of a single amino acid at the basic domain (4). The mi ew and mi ce mutant alleles encode MITFs with large deletion in the basic and zipper domains, respectively (4, 36). All tg, mi ew, and mi ce are null mutations, whereas the mi is an inhibitory mutation (11, 30, 36). The Mi wh showed decreased but detectable transcription activities on some genes and also significant inhibitory effects on transcription of other genes (35, 37). In spite of different structural and functional abnormalities of each mutant MITF, depletion of peritoneal mast cells was common among all MITF homozygous mutants examined. Tissues other than the skin of all MITF mutant mice also lacked mast cells. In contrast, mast cells were present in the skin tissue of all MITF mutants (30, 35–37). Probably, the skin is an exceptional tissue for development of mast cells. In fact, mast cells develop before birth only in the skin tissue (20). Depletion of mast cells in the peritoneal cavity appeared suitable for investigation of the mechanisms of development of mast cells.

The peritoneal cavity is also suitable for examining the involvement of mast cells in the innate immunity (21, 22). The reduced survival rate of WBB6F1-W/W v mice after CLP was normalized by the intraperitoneal transplantation of WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs. WBB6F1-tg/tg mice also lacked peritoneal mast cells and showed the reduced survival rate after CLP. In contrast to WBB6F1-W/W v mice, however, the survival rate of WBB6F1-tg/tg mice was not normalized by the prior transplantation of WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs. We examined the effect of the transplantation between WBB6F1-W/W v and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice, and found that anatomical distribution of mast cells was different between them. Mast cell number was normalized in the peritoneal cavity of both WBB6F1-W/W v and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. Mast cells did appear in the mesentery of WBB6F1-W/W v mice, but did not in the mesentery of WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. Mast cells within tissues or mast cells in the vicinity of blood vessels appeared to play an important role against the acute bacterial peritonitis induced by CLP.

Intraperitoneally transplanted CMCs of WBB6F1-+/+ mouse origin invaded from the peritoneal cavity to the mesentery of WBB6F1-W/W v mice but did not invade to the mesentery of WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. Intravenously transplanted WBB6F1-+/+ CMCs invaded and settled in tissues of WBB6F1-W/W v mice, but did not in tissues of WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. There is a possibility that the tissues of WBB6F1-tg/tg mice have a defect in microenvironment that is necessary for the migration and settlement of normal CMCs. MITF was expressed in the mesentery and spleen of WBB6F1-+/+ and WBB6F1-W/W v mice but did not in those of WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. If MITF is involved in the transcription of microenvironmental factor(s) that play significant roles for the migration and settlement of normal CMCs, the absence of MITF may result in such a microenvironmental defect in tissues of WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. We expected the deficient expression of SCF in the mesentery and spleen of WBB6F1-tg/tg mice, but the amount of SCF mRNA was comparable among the tissues of WBB6F1-+/+, WBB6F1-W/W v, and WBB6F1-tg/tg mice. The microenvironmental defect of WBB6F1-tg/tg mice might be attributable to the deficient transcription of factor(s) other than SCF. Such factor(s) remain to be identified.

Taken together, WBB6F1-tg/tg mice appeared useful for studying the effect of anatomical distribution of mast cells on their antiseptic function.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. H. Arnheiter for VGA-9-tg/tg mice, and Dr. M.L. Lamoreux for B6-mi ew/mivit and B6-mi ce/mivit mice. We also thank Mr. M. Kohara, Ms. T. Sawamura, and Ms. K. Hashimoto for technical assistance.

This work is supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: B6, C57BL/6; CLP, caecal ligation and puncture; CMC, cultured mast cell; MITF, microphthalmia transcription factor; SCF, stem cell factor.

References

- 1.Hodgkinson, C.A., K.J. Moore, A. Nakayama, E. Steingrimsson, N.G. Copeland, N.A. Jenkins, and H. Arnheiter. 1993. Mutations at the mouse microphthalmia locus are associated with defects in a gene encoding a novel basic-helix-loop-helix-zipper protein. Cell. 74:395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes, J.J., J.B. Lingrel, J.M. Krakowsky, and K.P. Anderson. 1993. A helix-loop-helix transcription factor-like gene is located at the mi locus. J. Biol. Chem. 268:20687–20690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hemesath, T.J., E. Steingrimsson, G. McGill, M.J. Hansen, J. Vaught, C.A. Hodgkinson, H. Arnheiter, N.G. Copeland, N.A. Jenkins, and D.E. Fisher. 1994. Microphthalmia, a critical factor in melanocyte development, defines a discrete transcription factor family. Genes Dev. 8:2770–2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steingrimsson, E., K.J. Moore, M.L. Lamoreux, A.R. Ferre-D'Amare, S.K. Burley, D.C. Zimring, L.C. Skow, C.A. Hodgkinson, H. Arnheiter, N.G. Copeland, and N. Jenkins. 1994. Molecular basis of mouse microphthalmia (mi) mutations helps explain their developmental and phenotypic consequences. Nat. Genet. 8:256–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morii, E., K. Takebayashi, H. Motohashi, M. Yamamoto, S. Nomura, and Y. Kitamura. 1994. Loss of DNA binding ability of the transcription factor encoded by the mutant mi locus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 205:1299–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takebayashi, K., K. Chida, I. Tsukamoto, E. Morii, H. Munakata, H. Arnheiter, T. Kuroki, Y. Kitamura, and S. Nomura. 1996. The recessive phenotype displayed by a dominant negative microphthalmia-associated transcription factor mutant is a result of impaired nucleation potential. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:1203–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morii, E., T. Tsujimura, T. Jippo, K. Hashimoto, K. Takebayashi, K. Tsujino, S. Nomura, M. Yamamoto, and Y. Kitamura. 1996. Regulation of mouse mast cell protease 6 gene expression by transcription factor encoded by the mi locus. Blood. 88:2488–2494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jippo, T., E. Morii, K. Tsujino, T. Tsujimura, Y.-M. Lee, D.-K. Kim, H. Matsuda, H.-M. Kim, and Y. Kitamura. 1997. Involvement of transcription factor encoded by the mouse mi locus (MITF) in expression of p75 receptor of nerve growth factor in cultured mast cells of mice. Blood. 90:2601–2608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morii, E., T. Jippo, T. Tsujimura, K. Hashimoto, D.-K. Kim, Y.-M. Lee, H. Ogihara, K. Tsujino, H.-M. Kim, and Y. Kitamura. 1997. Abnormal expression of mouse mast cell protease 5 gene in cultured mast cells derived from mutant mi/mi mice. Blood. 90:3057–3066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ito, A., E. Morii, E. Maeyama, T. Jippo, D.-K. Kim, Y.-M. Lee, H. Ogihara, K. Hashimoto, Y. Kitamura, and H. Nojima. 1998. Systematic method to obtain novel genes that are regulated by mi transcription factor (MITF): impaired expression of granzyme B and tryptophan hydroxylase in mi/mi cultured mast cells. Blood. 91:3210–3221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito, A., E. Morii, D.-K. Kim, T.R. Kataoka, T. Jippo, K. Maeyama, H. Nojima, and Y. Kitamura. 1999. Inhibitory effect of the transcription factor encoded by the mi mutant allele in cultured mast cells of mice. Blood. 93:1189–1196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jippo, T., Y.-M. Lee, Y. Katsu, K. Tsujino, E. Morii, D.-K. Kim, H.-M. Kim, and Y. Kitamura. 1999. Deficient transcription of mouse mast cell protease 4 gene in mutant mice of mi/mi genotype. Blood. 93:1942–1950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ge, Y., T. Jippo, Y.M. Lee, S. Adachi, and Y. Kitamura. 2001. Independent influence of strain difference and mi transcription factor on the expression of mouse mast cell chymases. Am. J. Pathol. 158:281–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tachibana, M., Y. Hara, D. Vyas, D. Hodgkinson, J. Fex, K. Grundfast, and H. Arnheiter. 1992. Cochlear disorder associated with melanocyte anomaly in mice with a transgenic insertional mutation. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 3:433–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsujimura, T., K. Hashimoto, E. Morii, G.T. Muhammad, K. Tsujino, T. Kondo, Y. Kanakura, and Y. Kitamura. 1997. Involvement of transcription factor encoded by the mouse mi locus (MITF) in apoptosis of cultured mast cells induced by removal of interleukin-3. Am. J. Pathol. 151:1043–1051. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silvers, W.K. 1979. The Coat Colors of Mice: A Model for Mammalian Gene Action and Inter Action. Springer-Verlag, New York, NY. 332 pp.

- 17.Steingrimsson, E., L. Tessarollo, B. Pathak, L. Hou, H. Arnheiter, N.G. Copeland, and N.A. Jenkins. 2002. Mitf and Tfe3, two members of the Mitf-Tfe family of bHLH-Zip transcription factors, have important but functionally redundant roles in osteoclast development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:4477–4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morii, E., H. Ogihara, K. Oboki, C. Sawa, T. Sakuma, S. Nomura, J.D. Esko, H. Handa, and Y. Kitamura. 2001. Inhibitory effect of the mi transcription factor encoded by the mutant mi allele on GA binding protein-mediated transcript expression in mouse mast cells. Blood. 97:3032–3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasugai, T., K. Oguri, T. Jippo-Kanemoto, M. Morimoto, A. Yamatodani, K. Yoshida, Y. Ebi, K. Isozaki, H. Tei, T. Tsujimura, et al. 1993. Deficient differentiation of mast cells in the skin of mi/mi mice. Usefulness of in situ hybridization for evaluation of mast cell phenotype. Am. J. Pathol. 143:1337–1347. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitamura, Y., M. Shimada, and S. Go. 1979. Presence of mast cell precursors in fetal liver of mice. Dev. Biol. 70:510–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Echtenacher, B., D.N. Mannel, and L. Hultner. 1996. Critical protective role of mast cells in a model of acute septic peritonitis. Nature. 381:75–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malaviya, R., T. Ikeda, E. Ross, and S.N. Abraham. 1996. Mast cell modulation of neutrophil influx and bacterial clearance at sites of infection through TNF-α. Nature. 381:77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yurt, R.W., R.W. Leid, K.F. Austen, and J.E. Silbert. 1977. Native heparin from rat peritoneal mast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 252:518–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilbert, H.S., and L. Ornstein. 1975. Basophil counting with a new staining method using alcian blue. Blood. 46:279–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakano, T., T. Sonoda, C. Hayashi, A. Yamatodani, Y. Kanakura, T. Yamamura, H. Asai, T. Yonezawa, Y. Kitamura, and S.J. Galli. 1985. Fate of bone marrow-derived cultured mast cells after intracutaneous, intraperitoneal, and i.v. transfer into genetically mast cell deficient W/W v mice: evidence that cultured mast cells can give rise to both connective tissue type and mucosal mast cells. J. Exp. Med. 162:1025–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakahata, T., S.S. Spicer, J.R. Cantey, and M. Ogawa. 1982. Clonal assay of mouse mast cell colonies in methylcellulose culture. Blood. 60:352–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Enerbech, L. 1974. Berberine sulfate binding to mast cell polyanions: a cytofluorometric method for the quantitation of heparin. Histochemistry. 42:301–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitamura, Y., S. Go, and K. Hatanaka. 1978. Decrease of mast cells in W/W v mice and their increase by bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 52:447–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galli, S.J., and Y. Kitamura. 1987. Animal model of human disease: genetically mast cell-defficient W/W v and Sl/Sl d mice. Their value for the analysis of the roles of mast cells in biologic responses in vivo. Am. J. Pathol. 127:191–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morii, E., H. Ogihara, K. Oboki, T.R. Kataoka, K. Maeyama, D.E. Fisher, M.L. Lamoreux, and Y. Kitamura. 2001. Effect of a large deletion of the basic domain of mi transcription factor on differentiation of mast cells. Blood. 98:2577–2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams, D.E., J. Eisenman, A. Baied, C. Rauch, K.V. Ness, C.J. March, J.S. Park, U. Martin, D.Y. Mochizuki, H.S. Boswell, et al. 1990. Identification of ligand for the c-kit proto-oncogene. Cell. 63:167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franagan, J.G., and P. Lader. 1990. A cell surface molecule altered in steel mutant fibroblast. Cell. 63:185–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zsebo, K.M., D.A. Williams, E.N. Geissler, V.C. Broudy, F.H. Martin, H.L. Atkins, R.Y. Hsu, N.C. Birkett, K.H. Okino, D.C. Murdock, et al. 1990. Stem cell factor is encoded at the Sl locus of the mouse and is the ligand for the c-kit tyrosine kinase receptor. Cell. 63:213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang, E., K. Nocka, D.R. Beider, T.Y. Chu, J. Buck, H.W. Lahm, D. Wellner, P. Leder, and P. Besmer. 1990. The hematopoietic growth factor KL is encoded by the Sl locus and is the ligand of the c-kit receptor, the gene product of the W locus. Cell. 63:225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim, D.-K., E. Morii, H. Ogihara, Y.-M. Lee, T. Jippo, S. Adachi, K. Maeyama, H.-M. Kim, and Y. Kitamura. 1999. Different effect of various mutant MITF encoded by mi, Mi or, or Mi wh allele on phenotype of murine mast cells. Blood. 93:4179–4186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morii, E., H. Ogihara, D.-K. Kim, A. Ito, K. Oboki, Y.-M. Lee, T. Jippo, S. Nomura, K. Maeyama, M.L. Lamoreux, and Y. Kitamura. 2001. Importance of leucine zipper domain of mi transcription factor (MITF) for differentiation of mast cells demonstrated using mi ce/mice mutant mice of which MITF lacks the zipper domain. Blood. 97:2038–2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kataoka, T.R., E. Morii, K. Oboki, T. Jippo, K. Maeyama, and Y. Kitamura. 2002. Dual abnormal effects of mutant MITF encoded by Miwh allele on mouse mast cells: decreased but recognizable transactivation and inhibition of transactivation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 297:111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]