Abstract

Among several different types of phospholipase A2 (PLA2), cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2)α and group IIA (IIA) secretory PLA2 (sPLA2) have been studied intensively. To determine the discrete roles of cPLA2α in platelets, we generated two sets of genetically engineered mice (cPLA2α−/−/sPLA2-IIA−/− and cPLA2α−/−/sPLA2-IIA+/+) and compared their platelet function with their respective wild-type C57BL/6J mice (cPLA2α+/+/sPLA2-IIA−/−) and C3H/HeN (cPLA2α+/+/sPLA2-IIA+/+). We found that cPLA2α is needed for the production of the vast majority of thromboxane (TX)A2 with collagen stimulation of platelets. In cPLA2α-deficient mice, however, platelet aggregation in vitro is only fractionally decreased because small amounts of TX produced by redundant phospholipase enzymes sufficiently preserve aggregation. In comparison, adenosine triphosphate activation of platelets appears wholly independent of cPLA2α and sPLA2-IIA for aggregation or the production of TX, indicating that these phospholipases are specifically linked to collagen receptors. However, the lack of high levels of TX limiting vasoconstriction explains the in vivo effects seen: increased bleeding times and protection from thromboembolism. Thus, cPLA2α plays a discrete role in the collagen-stimulated production of TX and its inhibition has a therapeutic potential against thromboembolism, with potentially limited bleeding expected.

Keywords: knockout mice, platelet aggregation, bleeding, thromboembolism, thromboxane

Introduction

Platelets are required for hemostasis but also contribute in the pathogenesis of thrombotic and inflammatory diseases. A discrete therapeutic change in their properties is needed to maintain safety. Lipid mediators generated from phospholipid membranes, platelet-activating factor, or eicosanoids derived from released arachidonic acid (AA)*are thought to play an important role in their activation (1–4). The inhibition of an AA modifying enzyme, cyclooxygenase, by aspirin continues to be the single most successful therapy at preventing thrombotic disease (5). Thromboxane (TX)A2 has been most clearly linked to function with the reports of genetic defects causing bleeding tendencies (6–8). There are potentially multiple classes of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) that may be involved in AA release: group IIA (IIA) secretory PLA2 (sPLA2), cytosolic PLA2s (cPLA2s), group V sPLA2, calcium-independent PLA2s, and group X sPLA2 (9–13). As well as through the sequential action of phospholipase C (PLC), diglyceride lipase, and monoglyceride lipase, AA can be generated from phosphatidylinositol. However, cPLA2α, acting primarily on phosphatidylcholine, is thought to be the main enzyme involved in AA release on the activation of platelets. The discovery of paralogues, β and γ forms of this enzyme, in addition to the previously cloned cPLA2α form, has added further complexity (14–16).

Platelet exposure to matrix components such as collagen necessitates a rapid response. In a complex multistage process platelets change shape, degranulate, and then aggregate (17). The binding of platelets to collagen has been reported to involve at least two receptors. Initial binding is to an integrin, α2β1, which can bind at high sheer rates and is reported to activate AA release by PLA2 enzymes. In vivo, this binding is likely followed by the subsequent binding of collagen to glycoprotein VI (18). Other platelet activators, thrombin, TXA2, ADP, and platelet-activating factor, act through G protein–coupled receptors on the surface of platelets. The blocking of G protein signaling may effectively inhibit platelet aggregation induced by collagen interfering with the accelerating effects of TXA2 and ADP released after collagen binding and signaling.

The study of the enzymes involved in AA release is restricted by the unavailability of highly specific inhibitors to the various PLA2s. Mice lacking both cPLA2α (engineered) and sPLA2-IIA (spontaneous) were previously generated to study the role of cPLA2α in vivo (19, 20). Backcrossing these mice into the C3H/HeN mice with a working sPLA2-IIA gene creates a strain with only the cPLA2α gene inactivated. Both strains of mice were generated in our laboratory and studied to question the specific role of cPLA2α in platelet activation. In vitro studies were conducted with the simultaneous measurement of degranulation by ATP release and platelet aggregation through impedance allowing the evaluation of the continuous effects of the loss of these enzymes (21, 22). Bleeding times and a thromboembolism model were used to study the effects in vivo.

Our results support a key role for cPLA2α in the production of TXA2 in platelets but suggest a basic redundancy in its production from other mechanisms. We also found that ADP or TXA2 activation of platelets appears independent of cPLA2α and likely leads to the involvement of other PLA2s. In vivo studies suggest that a specific cPLA2α inhibitor, in addition to an antiallergic/antiinflammatory effect and a growth suppression effect on intestinal polyp (19, 20, 23–31), will therefore have an antivasoconstrictive effect by dramatically reducing the amount of TXA2 produced.

Materials and Methods

Reagents.

1 mg/ml equine type I collagen, 1 mM ADP, ATP standard, and Chrono-lume reagent, a bioluminescent luciferase mixture, were purchased from Chrono-log Co. Before use, U46619, a TX receptor agonist in methyl acetate, was evaporated and diluted in PBS (Cayman Chemical). SQ29548, a highly specific TXA2 receptor antagonist, was dissolved in ethanol for storage and then evaporated and diluted in PBS just before experiments were performed (Cayman Chemical). Indomethacin (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate before use. 12(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (HETE) was purchased from Cayman Chemical.

Mice.

Inbred mice were purchased from Central Laboratories for Experimental Animals Japan. As previously described (19), the cPLA2α gene was disrupted by replacing part of an internal exon with a PGK-neo cassette. The mice generated (F2 of C57BL/6J and 129/Ola) were cPLA2α−/− and were also discovered to be congenitally defective in sPLA2-IIA due to a frameshift mutation in the sPLA2-IIA gene (32, 33). These mice were backcrossed to the C3H/HeN strain, which were gene sequenced to ensure the presence of a functional sPLA2-IIA gene. Eighth and ninth generation backcrossed C3H/HeN mice were used. Twelfth generation backcrossed C57BL/6J mice were also used in the experiments. All mice were genotyped by a PCR method as previously described (19).

In Vitro Platelet Responses.

20–48-wk-old littermate backcrossed mice matched for sex were studied in pairs (cPLA2α+/+, cPLA2α−/−) to exclude any potential bias. Mice were anesthetized with 25 mg/kg pentobarbital and 25 mg/kg ketamine, and ∼1 ml of whole blood was immediately collected in 0.35% (wt/vol) sodium citrate after cardiac puncture. After 30 min, 100 μl whole blood was diluted with 800 μl normal saline and 100 μl Chromo-lume reagent. Aggregation as measured by change in impedance and ATP release from dense granules were monitored continuously by luminometry (Chrono-Log Co.). To allow for comparison between the experiments, aggregation/impedance was adjusted to measure a set change in resistance by changing the baseline and height of a standard impulse. A 2-nM dose of ATP was added at the end of each measurement to standardize ATP. If the baseline measurement of ATP indicated the presence of marked platelet degranulation during cardiac puncture, the experiment was terminated. Continuous measurements were made electronically at every 25 ms, but summarized to the second for analysis. Reagents were added only after 2 min of a flat baseline in both measurements and the ATP level was <0.1 nM.

TXA2 Assay.

After 9 min of reaction, 100 μl of the aliquot was placed on ice. Samples were then spun at 1,000 g for 5 min and the supernatant was frozen at −70°C until analysis. For each mouse, 50 μl of the sample was saved to measure the baseline levels before stimulus. TXB2, a nonenzymic hydrolyzed product of TXA2, was measured by an enzyme immunoassay kit (Cayman Chemical).

12-HETE Assay.

Quantification of 12-HETE was performed by reversed phase HPLC (system GOLD; Beckman Coulter) using a solvent of acetonitrile/methanol/water/acetic acid, 350:150:250:1 (2, 34). Flow rate was 1 ml/min and eluent was monitored at 235 nm. Blood was collected from incisions on femoral vessels of anesthetized mice (25 mg/kg pentobarbital and 25 mg/kg ketamine). After 30 min of incubation at room temperature to allow clotting, serum samples were collected by centrifugation at 500 g for 5 min. Samples were extracted with ethylacetate after acidification to a pH of ∼5.0 with 0.5 vol of 0.1% formic acid, dried on a centrifuge concentrator, dissolved in the HPLC solvent, and analyzed. To normalize the extraction rate, 0.5 nmol 12(S)-HETE was added to selected samples before extraction and the difference of the area was calculated.

Bleeding Time.

Adult mice were restrained in the upright position and the tail was cut 2–3 mm from the tip. The tail was then immersed in saline at 37°C and the bleeding time was defined as the time point at which all visible signs of bleeding from the incision had stopped, or at 10 min (35). Because of a significant difference between males and females in knockout C3H/HeN, only females were used in later studies. 10 mg/kg indomethacin was injected intraperitoneally 1 h before the bleeding times were tested in age-matched female mice.

Thromboembolism Test.

In mice anesthetized with 80 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital, a collagen–ADP mixture (4 ml/kg of a saline-based solution containing 250 mg/ml collagen and 200 μM ADP) was injected into the jugular vein. Survival was evaluated 1 h after injection (36, 37). The dose was pretested to ensure 100% killing of wild-type mice (38). One pair of mice were killed and intubated 2 min after injection. 4% formalin in PBS was injected into the lung, and then the heart and lung were dissected together and placed in 10% formalin in PBS. Serial sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for examination. A blindfolded investigator counted 20 areas at 400× for each mouse to determine the percentage of clotted vessels.

Statistics.

All values are expressed as mean ± SD unless stated otherwise. Two-tailed t tests were used to test the significance on continuous data and multiple regression was used to calculate the P-values on nominal data and in multivariable analysis (Quattro Pro).

Results

Degranulation and Aggregation to Collagen.

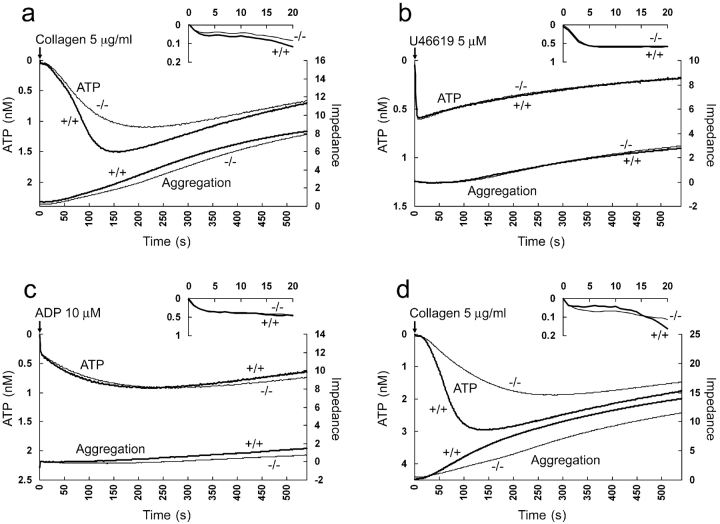

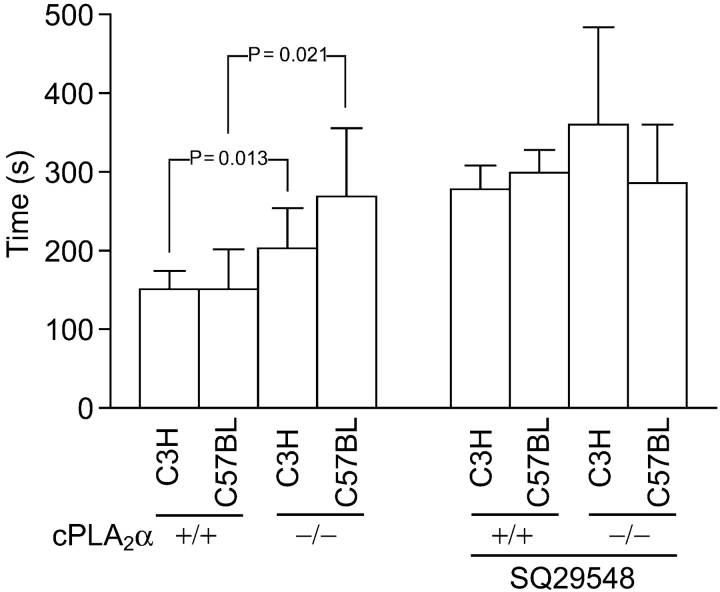

C3H/HeN cPLA2α−/− sPLA2-IIA+/+ mice show a delay in degranulation as measured by ATP release in response to collagen (Fig. 1 a). This accompanies a more concave impedance curve, indicating a slowing in the acceleration phase of platelet aggregation. Aggregation achieved at 9 min was preserved in cPLA2α−/− platelets. The time to achieve peak ATP release (Fig. 2 , left, P = 0.013) and the time to reach 50% of aggregation achieved within 9 min (Fig. 1 a; cPLA2α+/+, 227 ± 43.7 s vs. cPLA2α−/−, 268 ± 42.8 s; P = 0.042) is significantly delayed. Focusing on the first 20 s of the reaction, it appears that the loss of cPLA2α starts to have an effect on the rate of degranulation at about the 20-s mark (Fig. 1 a). Compared to the changes in response to collagen, the reaction to U46619, a TX agonist, and ADP, both of which work through G protein–mediated receptors, appears to be unchanged (Fig. 1, b and c). C57BL/6J cPLA2α+/+ sPLA2-IIA−/− mice appear to have the same shaped curve as C3H/HeN cPLA2α+/+ sPLA2-IIA+/+ mice (Fig. 1 d). C57BL/6J cPLA2α−/− sPLA2-IIA−/− mice also show a significant delay in the degranulation peak (Fig. 2), and a more concave aggregation curve. The times to reach 50% of aggregation were as follows: cPLA2α+/+ sPLA2-IIA−/−, 178 ± 14.6 s versus cPLA2α−/− sPLA2-IIA−/−, 255 ± 67.0 s; P = 0.021. An indirect comparison of the changes between C3H/HeN and C57BL/6J mice using time to peak ATP can be attempted. There is an indication of an additional step delay due to the additional loss of sPLA2 when compared with cPLA2α loss alone (Fig. 1, a and d, and Fig. 2). The effect of other factors cannot fully be excluded due to the differences in the mouse strains used.

Figure 1.

Effect of cPLA2α on platelet activation. ATP release (left axis) as monitored by luciferase activity is seen on the top of each graph. The first 20 s of the reaction is magnified above. Platelet aggregation (right axis) as measured by impedance is at the bottom. In each case, averaged data from wild-type littermates (+/+) are paired with sex-matched cPLA2α-deficient mice (−/−). (a) C3H/HeN mice platelet reaction to collagen (n = 9). (b) C3H/HeN reaction to U46619 (n = 7). (c) C3H/HeN reaction to ADP (n = 6). (d) C57BL/6J reaction to collagen (n = 4).

Figure 2.

Time to peak ATP after collagen. The mean of individual times to maximum ATP level of each mouse is used in Figs. 1 and 4 plotted by strain, cPLA2α status, and TXA2 antagonist, SQ29548. Error bars are SD above the mean and P-values stand for significant differences.

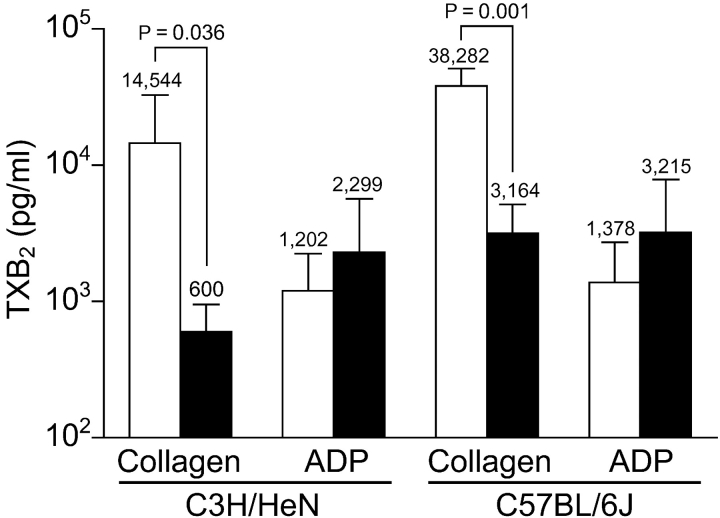

TX Levels.

Compared to the small difference in degranulation and aggregation in vitro (Figs. 1 and 2), there is a marked, significant decrease in the amount of TXB2 production as detected after collagen activation between cPLA2α+/+ and cPLA2α−/− mice in both C3H/HeN and C57BL/6J strains (Fig. 3) . The absolute difference in the C57BL/6J mice is larger (3.5 vs. 1.4 ng/ml), which is consistent with the ATP and aggregation curves. With the increase in TXA2 upon stimulation, it is also clear that a limited amount of AA is being released in both strains of cPLA2α−/− mice, indicating the presence of another PLA2 or an alternative AA-generating pathway. In accord with the aggregation and degranulation data (Fig. 1), there is little difference in TXB2 production in response to ADP between C3H/HeN wild-type and cPLA2α-deficient mice, suggesting a cPLA2α-independent mechanism for TXA2 production with ADP as a stimulus. Similarly in C57BL/6J platelets stimulated with ADP, there was little difference in ATP release and aggregation (unpublished data), and TXB2. Therefore, an AA-releasing mechanism, possibly another PLA2(s) or PLC–diglyceride lipase system independent of both cPLA2α and sPLA2-IIA, is present in platelets upon the stimulation of G protein–coupled receptor ligands.

Figure 3.

TXB2 produced after platelet stimulation. Mean change in TXB2 levels of mice pairs in Fig. 1. Open columns, cPLA2α+/+ mice; shaded columns, cPLA2α−/− mice. Because of the log scale, actual mean is given above the columns, error bars are SD above the mean, and P-values stand for significant differences.

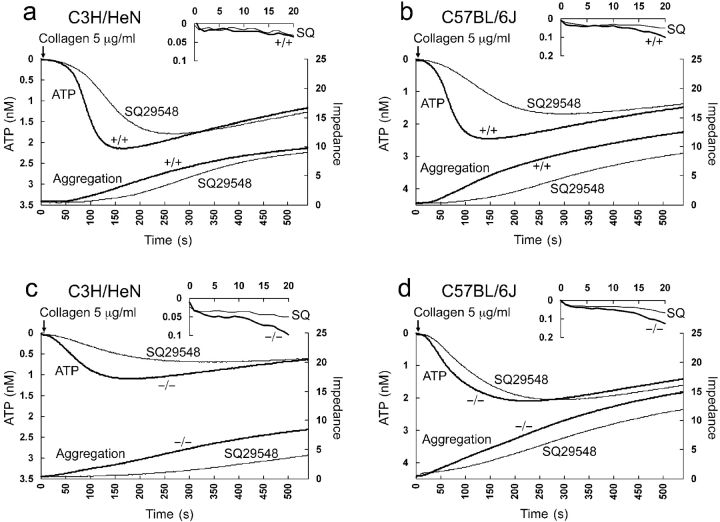

Effect of a Specific TX Antagonist.

To confirm the presence of additional specific TXA2 activity generated by cPLA2α/sPLA2-IIA, a specific TXA2 receptor antagonist, SQ29548, was used (39). Platelet activation appears both TXA2-dependent and -independent, as SQ29548 was unable to completely block activation in all cases (Fig. 4) . Upon examining the TXA2-dependent component, the results on C3H/HeN cPLA2 −/− sPLA2-IIA+/+ mice and C57BL/6J cPLA2 −/− sPLA2-IIA−/− in Fig. 4, c and d, confirm the presence of an alternative redundant enzyme(s) because a persistent inhibiting effect is seen in both mouse strains. In addition, SQ29548 inhibited degranulation and aggregation slightly more in the C57BL/6J mice, where the sPLA2-IIA enzyme activity is missing, than in the C3H/HeN mice (Fig. 4, compare a and c, and b and d). A hint of the additional effect of sPLA2-IIA is also seen when all the times to peak ATP results are graphed (Fig. 2). There appears to be a stepwise delay as successive enzymes are lost or TXA2 activity is blocked. Statistically, however, multiple regression of the factors that influence time to peak ATP demonstrates an independent significant effect of the loss of cPLA2α and the inhibitor SQ29548. The effect of the mice strain (the loss of sPLA2-IIA) did not reach statistical significance. Therefore, in these studies we can only conclude that cPLA2α−/− platelets have an alternative AA-generating mechanism to cPLA2α and sPLA2-IIA. However, it is interesting to see that as expected, the effect of the inhibitor is smaller in the C57BL/6J strain with only a possible delay in the initiation of the reaction seen (Fig. 4, c and d). There is also a suggestion that the inhibitor effect of SQ29548 occurs earlier than at 20 s when compared with the effect of the loss of cPLA2α as seen in Fig. 1.

Figure 4.

Effect of a TXA2 receptor antagonist, SQ29548, on platelet activation. ATP release (left axis) as monitored by luciferase activity is seen on the top of each graph. The first 20 s of the reaction is magnified above. Platelet aggregation (right axis) as measured by impedance is at the bottom. In each case, responses to collagen are compared with and without SQ29548 from pooled data from wild-type (+/+) or cPLA2α-deficient mice (−/−). (a) C3H/HeN cPLA2α+/+ mice (n = 3), (b) C57BL/6J cPLA2α+/+ mice (n = 3), (c) C3H/HeN cPLA2α−/− mice (n = 2), and (d) C57BL/6J cPLA2α−/− mice (n = 2).

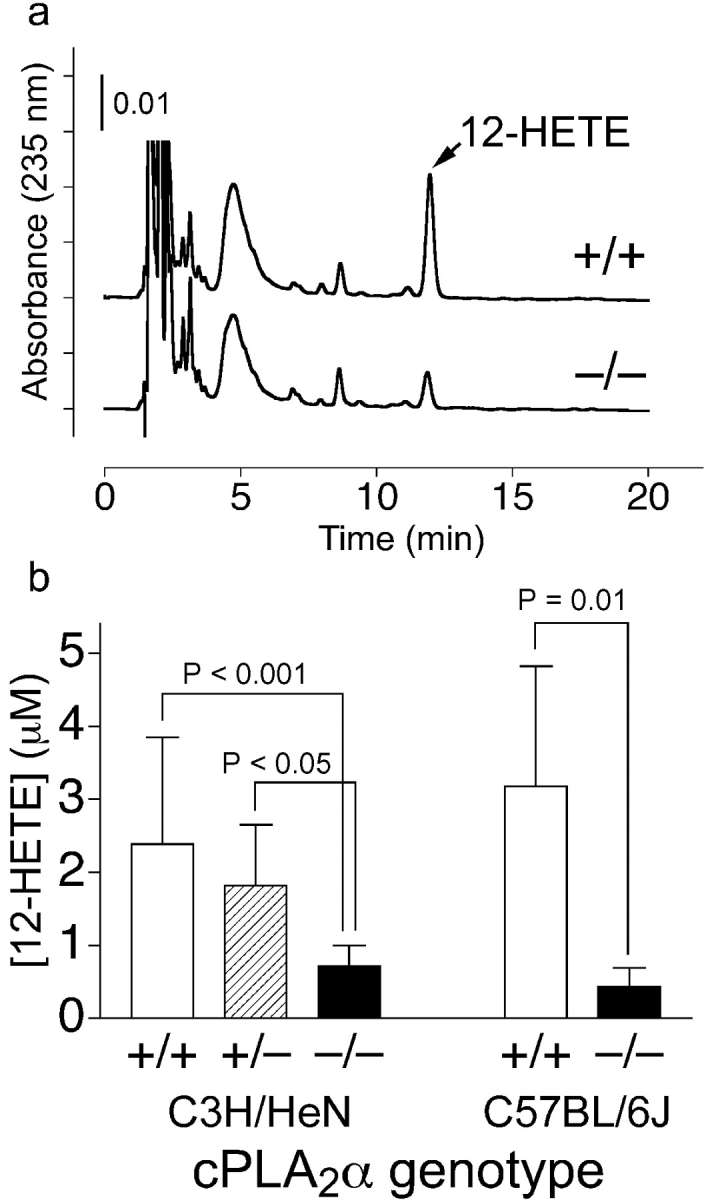

Serum 12-HETE Levels.

Next, we determined the contribution of cPLA2α on the production of 12-HETE, another AA metabolite. As shown in Fig. 5 a, elution of 12-HETE was observed at 11.9 min on HPLC analysis. The absorbance spectrum was indistinguishable from authentic 12(S)-HETE, and coelution was also observed when they were mixed (not depicted). As shown in Fig. 5 b, the calculated concentration of 12-HETE in serum from C3H/HeN cPLA2α−/− adult female mice was 0.72 ± 0.28 μM (n = 14), significantly lower than cPLA2α+/+ (2.4 ± 1.5 μM; n = 13; P < 0.001) and cPLA2α+/− (1.8 ± 0.83 μM; n = 15; P < 0.05). A similar significant difference was observed for C57BL/6J adult male mice: cPLA2α+/+ (3.2 ± 1.6 μM; n = 6) versus cPLA2α−/− (0.44 ± 0.25 μM; n = 6; P = 0.01; Fig. 5 b).

Figure 5.

Serum 12-HETE content. (a) Representative HPLC chart. +/+, a cPLA2α+/+ mouse (3.6 μM); −/−; a cPLA2α−/− mouse (1.0 μM). (b) Mean levels of 12-HETE in serum. Open columns, cPLA2α+/+ mice; hatched column, cPLA2α+/− mice; shaded columns, cPLA2α−/− mice. Error bars are SD above the mean and P-values stand for significant differences.

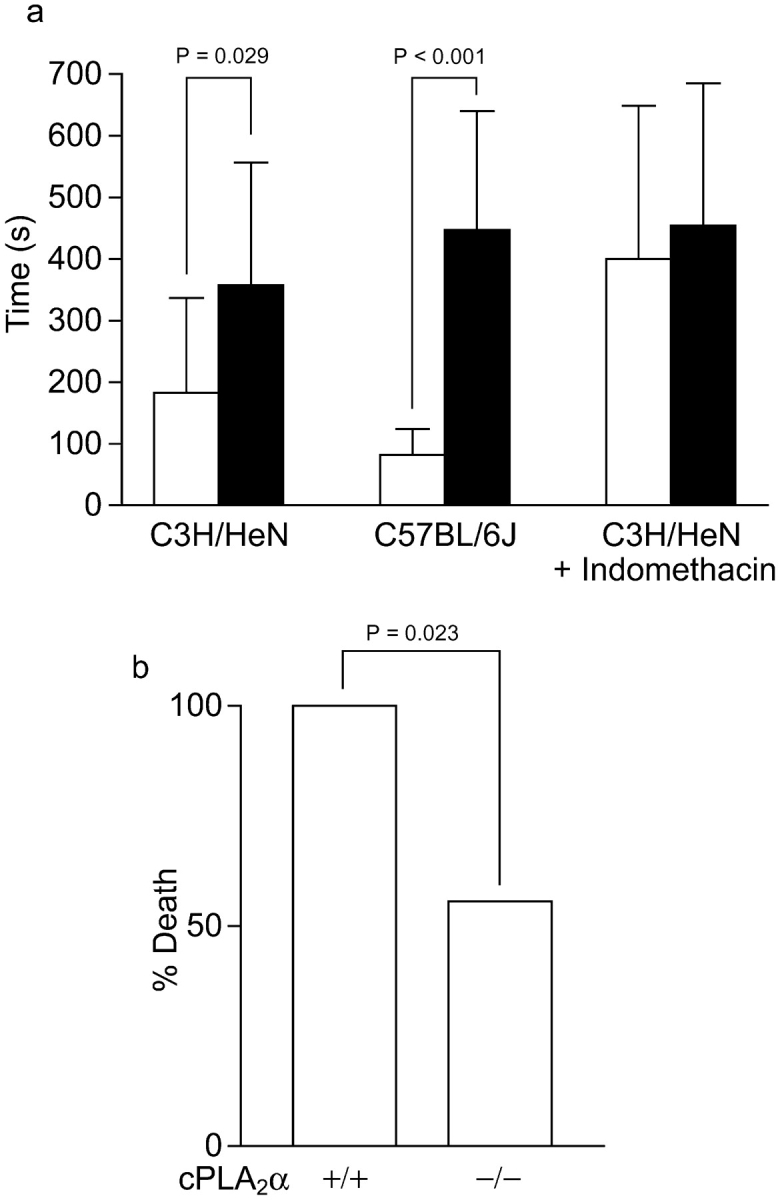

Marked Changes in Bleeding Time.

Compared to the in vitro aggregation results, the differences in bleeding time correlate with TXB2 levels. Bleeding times in both C3H/HeN and C57BL/6J mice were significantly increased (Fig. 6 a). However, because of a marked difference between male and female mice (unpublished data), only female mice were used for comparison between strains and interventions. Bleeding times, like the in vitro aggregation results, show that the cPLA2α−/− C57BL/6J mice have longer bleeding times than C3H/HeN females and cyclooxygenase inhibition with indomethacin leads to a similar increase in bleeding time.

Figure 6.

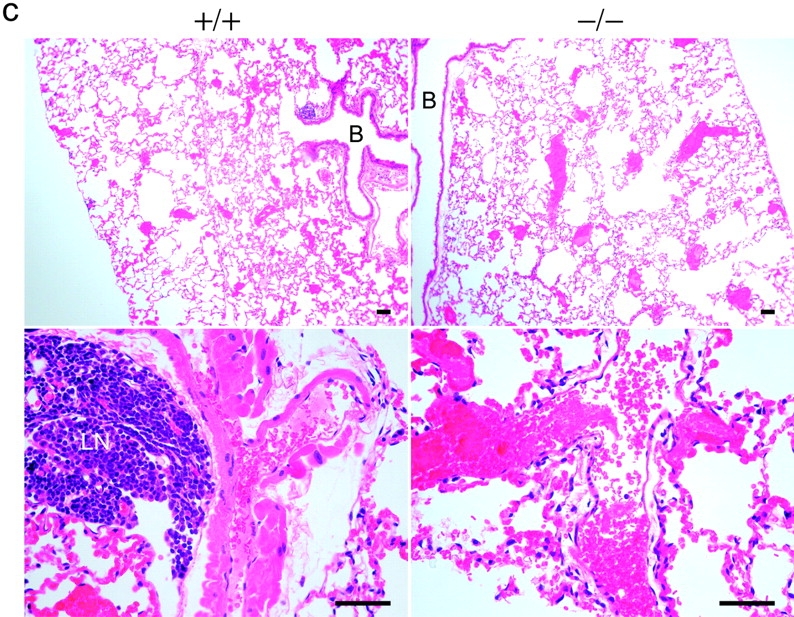

In vivo effects of cPLA2α. (a) Bleeding time. Open columns, cPLA2α+/+ female mice; shaded columns, cPLA2α−/− female mice. C3H/HeN mice (cPLA2α+/+, n = 15; cPLA2α−/−, n = 10), C57BL/6J (cPLA2α+/+, n = 7, wild-type nonlittermates; cPLA2α−/−, n = 7), and C3H/HeN mice treated with indomethacin (six mice in each group stratified by bleeding time). Error bars are SD above the mean and P-values for significant differences between cPLA2α+/+ and cPLA2α−/− are shown in each case. (b) Death in thromboembolism test of C3H/HeN littermate mice matched for sex and eight or ninth generation backcrossed. (c) Lung histology of cPLA2α−/− and cPLA2α+/+ hematoxylin and eosin stain. In cPLA2α−/− mice at a low magnification (top) there are multiple platelet clots seen, causing red blood cell congestion in small and medium vessels. At a higher magnification (bottom), draining veins can be seen with platelet clots. In cPLA2α+/+ mice at a low magnification (top), smaller vessels appear to be clotted. At a higher magnification a muscular artery is seen with platelet clots. B, bronchi; LN, lymph node. Bars, 100 μM.

Protective Effect of cPLA2α Loss on Thromboembolism.

In the thromboembolism test there was an increase in survival that is significant in cPLA2α−/− mice (Fig. 6 b). After the dissection of the heart and lungs together, the cPLA2α−/− lungs were of a much darker red than the cPLA2α+/+, suggesting increased vasoconstriction in the presence of cPLA2α. However, both were engorged with blood compared with normal lungs due to clots. Blinded counts show an equal percent of clotted vessels in the wild type and knockout (cPLA2α+/+, 76% vs. cPLA2α−/−, 82%). The percentage is similar to previous studies (37). In cPLA2α+/+ mice, small vessels were mostly clotted with evidence of arterial constriction and platelet clots in large arteries (Fig. 6 c, top and bottom right). In cPLA2α−/− mice, perhaps because of the lack of TXA2-induced arterial constriction, platelet clots were allowed to reach larger collecting veins (Fig. 6 c, top and bottom left). The large number of platelet clots seen in knockout mice indicates that platelets are able to aggregate well, as suggested by the in vitro studies. The collection of clots in the venous side of the pulmonary system in mice lacking cPLA2α appears to be more forgiving than clotting of the arterial side of the pulmonary artery system, which explains the reduction in mortality.

Discussion

By using platelets of two sets of genetically engineered mice, we found that cPLA2α plays a critical role in TXA2 production but a relatively redundant autocrine role in platelet aggregation due to an alternative AA-releasing mechanism. The lack of cPLA2α leads to a dramatic loss of TXA2 production from collagen-activated mouse platelets in vitro. This loss contrasts to a small but significant delay in ATP release and a small but significant loss in the acceleration of platelet aggregation. The TXA2 results, however, correlate well with a marked increase in bleeding time in mice lacking cPLA2α. This discrepancy is best explained if the vasoconstrictive effect of TXA2 is considered. The test of bleeding time transects large veins and arteries in the mice tail. The veins, in particular, could be seen bleeding profusely in some cPLA2α−/− males where the diameter of the tail is considerably larger than that of the female, whereas in cPLA2α−/− mice bleeding could stop abruptly at 60–90 s due to vasoconstriction. The need for more vasoconstriction normally induced by TXA2 would help explain the difference in bleeding time between the cPLA2α−/− C3H/HeN males (large diameter vessels) and females (smaller diameter vessels; unpublished data). This explanation fits well with the biological effects of TXA2 inhibition with aspirin. Acute vascular syndromes are being prevented but with well-preserved aggregation at low intermittent dosing, i.e., inhibiting much, but not all, of the TXA2. Small amounts of TXA2 might be required early by platelets to activate themselves effectively, whereas the larger amounts produced mostly by cPLA2α are intended for vasoconstriction. All of the current results support a dual function for TXA2 and a discrete role for cPLA2α in mouse platelets. (a) There are low levels of TXA2 in both strains of knockout mice and therefore relatively well-preserved aggregation. (b) ADP, TXA2 (Fig. 1, b and c, and Fig. 3), and probably other G protein–coupled receptor ligands, independent of cPLA2α, stimulate TXA2 production, suggesting a redundant source of low level AA release. (c) In both strains of mice, a specific TXA2 antagonist appeared to extend the delay in aggregation in proportion to the level of TXA2 expected to be generated and also appeared to have an earlier effect. (d) There is a stepwise increase in bleeding times due to the blocking of successive enzyme loss between cPLA2α−/− and cPLA2α−/−/sPLA2-IIA−/− mice, similar to the in vitro aggregation pattern. (e) During thromboembolism, the preservation of the ability to form platelet clots in cPLA2α−/− mice with decreased lethality is probably due to the modification of vascular effects.

These results suggest that although cPLA2α is responsible for the vast majority of TXA2 production in activated platelets after collagen stimulation, there are redundant enzymes in platelets that can maintain basic platelet aggregation with relatively small amounts of TXA2. The loss of this baseline autocrine TXA2 effect leads to a more profound loss of platelet function. At least two independent mechanisms of TXA2 production are apparent in mouse platelets with different PLA2 enzymes, production levels and physiological effects. Additional support for this is the log fold difference in the dose of TXA2 agonist required for smooth muscle contraction and platelet activation, even though the TXA2 receptors appear to be the same (40, 41). There is mounting evidence for the dual role, an intracellular role and an intercellular/extracellular role, for any given lipid mediator (42). The cPLA2α enzyme appears to play a critical part in generating lipid mediators for extracellular roles in platelets. It is also possible that platelets can utilize AA provided by serum lipids and neighboring cells.

The loss of cPLA2α also appears to be important in the release of AA needed to produce other lipid mediators that may augment platelet aggregation/TXA2 production (2). The loss of 12-HETE production evident in mice without cPLA2α provides another mechanism by which the absence of cPLA2α could act. The amount of 12-HETE dependence on cPLA2α during aggregation may also apply to 12-lipoxygenase activity in other cell types and could contribute to the antiatherosclerosis/antiangiogenesis effect of cPLA2α inhibition (43–46).

The delay in α granule release, as reflected in ATP, associates with and precedes the delay in aggregation and therefore may play a mechanistic role. There appears to be a more generalized delay in degranulation in cells missing cPLA2α (25, 26). The delay in degranulation is not present with a TX agonist or ADP and is reproduced with a specific antagonist, which suggests that a reduction in the pace of the reaction is the only explanation needed for the delay in ATP release in these studies.

Rather than representative data, electronic summarized graphs are chosen in our experiments to block out the multiple factors that can influence platelet studies in mice. Variations in activation and platelet numbers during cardiac puncture cannot be easily standardized. As an alternative to the current approach, dilution of whole blood to a standard platelet count would add the variation caused by the dilution of plasma factors. During preliminary studies on third generation mice, small differences in platelet response were seen. Therefore, steps such as blocking for age and sex were used to decrease all other possible sources of variation. The presence of similar results in both strains of mice and the complimentary findings with the use of a specific antagonist to TXA2 validates the approach. In vitro platelet data must, however, be viewed with some skepticism (47). In mice where careful controlled collection of blood is difficult, special care to correlate in vitro and in vivo experiments is needed. Although the use of different strains of mice help strengthen the generalization of the results, the comparisons between the two strains have to be carefully interpreted. The base levels of TXA2 and ATP levels between C3H/HeN and C57BL/6J in response to collagen are different. Without a C57BL/6J mouse with a functional sPLA2-IIA as a control, conclusions on the role of this enzyme in platelets cannot be certain. The addition, however, of studies using the C57BL/6J does show that sPLA2-IIA is not the only alternative AA-generating enzyme to cPLA2α in platelets.

Previous platelet studies with engineered mice put these new findings in context. Mice with Gαq deficiency have severe loss of platelet functions with little evidence for redundant processes for this key protein (48). In knocking out P2Y1, an ADP receptor, evidence was found for a second, partially redundant receptor that was recently cloned (36, 49, 50). The surprise finding, the disruption of CD39, which is an ATP diphosphohydrolase, was an inhibition of platelet aggregation (51). AA released by PLA2s may also be acted upon by 12-lipoxygenase to form 12-HETE. Knockout studies suggest that this might be a factor that plays a unique role in ADP-stimulated platelets (2). In TXA2 receptor knockout mice, findings very consistent with the current results were found (1). The bleeding times were also prolonged with the loss of TXA2 receptor, which contrasted with human receptor deficiency. However, the test for bleeding time in humans and that used in mice is very different. The vasoconstriction caused by TXA2 may have a significant effect on the bleeding times measured on mice tails compared to the human tests where aggregation in small skin vessels is tested. A delay in collagen activation compared to ADP activation was noted similarly to our paper. The current, more sensitive studies confirm a delay in the initiation of aggregation but also suggest that a stepwise loss of TXA2 has effects on aggregation, with the complete loss of all TXA2 having a more pronounced effect on aggregation. The current results cannot be directly compared with those of the TXA2 receptor knockout because of different methodologies. It cannot be excluded, however, that an additional mechanism, which is TXA2 receptor independent, is present. Studies involving multiple knockouts and specific inhibitors are needed to take the entire process apart.

The use of specific inhibitors to intracellular signaling proteins and knockout studies has provided some insights into how cPLA2α might be regulated in platelets. First, G protein–coupled receptors to ADP, thrombin and TXA2, appear to work through Gq proteins and activate PLC βs (48, 52, 53). Second, the recently cloned glycoprotein VI appears to require coactivation of the integrin α2β1 to initiate a reaction. That reaction involves lyn and fyn Src family kinases that affect p72 Syk, leading to a pathway through SLP-76 to PLCγ2 (17, 54–57). Third, the signaling though α2β1 involves actin polymerization and probably involves the activation of an Src kinase leading to a mitogen-activated protein kinase–dependent cPLA2 activation (58–61). Therefore, platelet activation appears to involve at least three different pathways that interact with one another. cPLA2α activation would appear to be related to the pathway through integrin α2β1 and an alternative mechanism, most likely another PLA2(s), through G protein–coupled receptors (ADP or TXA2, etc.). The picture that emerges is that platelet activation is a complex multichanneled process involving multiple surface receptors and intracellular signaling pathways that mostly behave in vivo with increasing intensity. The loss of any particular protein may thus have a broad or distinct effect depending on its unique placement in a complex scheme.

Although these results in mouse platelets provide insights into human platelet function, in vivo use of specific inhibitors of cPLA2α (62) and sPLA2-IIA are needed to confirm these results in humans.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. T. Yokomizo and S. Ishii, and members of the laboratory for discussion.

This work is supported in part by a grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, and grants from Uehara Memorial Foundation and Yamanouchi Foundation of Metabolic Disorders.

D.A. Wong's present address is University of Chicago, 5841 S. Maryland Ave., MC0930, Chicago, IL 60637.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: IIA, group IIA; AA, arachidonic acid; cPLA2, cytosolic phospholipase A2; HETE, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; PLA2, phospholipase A2; PLC, phospholipase C; sPLA2, secretory PLA2; TX, thromboxane.

References

- 1.Thomas, D.W., R.B. Mannon, P.J. Mannon, A. Latour, J.A. Oliver, M. Hoffman, O. Smithies, B.H. Koller, and T.M. Coffman. 1998. Coagulation defects and altered hemodynamic responses in mice lacking receptors for thromboxane A2. J. Clin. Invest. 102:1994–2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson, E.N., L.F. Brass, and C.D. Funk. 1998. Increased platelet sensitivity to ADP in mice lacking platelet-type 12-lipoxygenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:3100–3105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Austin, S.C., and C.D. Funk. 1999. Insight into prostaglandin, leukotriene, and other eicosanoid functions using mice with targeted gene disruptions. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 58:231–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serhan, C.N., J.Z. Haeggstrom, and C.C. Leslie. 1996. Lipid mediator networks in cell signaling: update and impact of cytokines. FASEB J. 10:1147–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patrono, C., B. Coller, J.E. Dalen, G.A. FitzGerald, V. Fuster, M. Gent, J. Hirsh, and G. Roth. 2001. Platelet-active drugs: the relationships among dose, effectiveness, and side effects. Chest. 119:39S–63S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao, A.K. 1998. Congenital disorders of platelet function: disorders of signal transduction and secretion. Am. J. Med. Sci. 316:69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuse, I., A. Hattori, M. Mito, W. Higuchi, K. Yahata, A. Shibata, and Y. Aizawa. 1996. Pathogenetic analysis of five cases with a platelet disorder characterized by the absence of thromboxane A2 (TXA2)-induced platelet aggregation in spite of normal TXA2 binding activity. Thromb. Haemost. 76:1080–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitsui, T., S. Yokoyama, Y. Shimizu, M. Katsuura, K. Akiba, and K. Hayasaka. 1997. Defective signal transduction through the thromboxane A2 receptor in a patient with a mild bleeding disorder: deficiency of the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate formation despite normal G-protein activation. Thromb. Haemost. 77:991–995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaminade, B., F. Le Balle, O. Fourcade, M. Nauze, C. Delagebeaudeuf, A. Gassama-Diagne, M.F. Simon, J. Fauvel, and H. Chap. 1999. New developments in phospholipase A2. Lipids. 34:S49–S55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dennis, E.A. 2000. Phospholipase A2 in eicosanoid generation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 161:S32–S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Six, D.A., and E.A. Dennis. 2000. The expanding superfamily of phospholipase A2 enzymes: classification and characterization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1488:1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murakami, M., Y. Nakatani, H. Kuwata, and I. Kudo. 2000. Cellular components that functionally interact with signaling phospholipase A2s. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1488:159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leslie, C.C. 1997. Properties and regulation of cytosolic phospholipase A2. J. Biol. Chem. 272:16709–16712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Underwood, K.W., C. Song, R.W. Kriz, X.J. Chang, J.L. Knopf, and L.L. Lin. 1998. A novel calcium-independent phospholipase A2, cPLA2-γ, that is prenylated and contains homology to cPLA2. J. Biol. Chem. 273:21926–21932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pickard, R.T., B.A. Strifler, R.M. Kramer, and J.D. Sharp. 1999. Molecular cloning of two new human paralogs of 85-kDa cytosolic phospholipase A2. J. Biol. Chem. 274:8823–8831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song, C., X.J. Chang, K.M. Bean, M.S. Proia, J.L. Knopf, and R.W. Kriz. 1999. Molecular characterization of cytosolic phospholipase A2-β. J. Biol. Chem. 274:17063–17067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alberio, L., and G.L. Dale. 1999. Review article: platelet-collagen interactions: membrane receptors and intracellular signalling pathways. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 29:1066–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jandrot-Perrus, M., S. Busfield, A.H. Lagrue, X. Xiong, N. Debili, T. Chickering, J.P. Le Couedic, A. Goodearl, B. Dussault, C. Fraser, et al. 2000. Cloning, characterization, and functional studies of human and mouse glycoprotein VI: a platelet-specific collagen receptor from the immunoglobulin superfamily. Blood. 96:1798–1807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uozumi, N., K. Kume, T. Nagase, N. Nakatani, S. Ishii, F. Tashiro, Y. Komagata, K. Maki, K. Ikuta, Y. Ouchi, et al. 1997. Role of cytosolic phospholipase A2 in allergic response and parturition. Nature. 390:618–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonventre, J.V., Z. Huang, M.R. Taheri, E. O'Leary, E. Li, M.A. Moskowitz, and A. Sapirstein. 1997. Reduced fertility and postischaemic brain injury in mice deficient in cytosolic phospholipase A2. Nature. 390:622–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Novak, E.K., M.P. McGarry, and R.T. Swank. 1985. Correction of symptoms of platelet storage pool deficiency in animal models for Chediak-Higashi syndrome and Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome. Blood. 66:1196–1201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swank, R.T., M. Reddington, O. Howlett, and E.K. Novak. 1991. Platelet storage pool deficiency associated with inherited abnormalities of the inner ear in the mouse pigment mutants muted and mocha. Blood. 78:2036–2044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sapirstein, A., and J.V. Bonventre. 2000. Specific physiological roles of cytosolic phospholipase A2 as defined by gene knockouts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1488:139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klivenyi, P., M.F. Beal, R.J. Ferrante, O.A. Andreassen, M. Wermer, M.R. Chin, and J.V. Bonventre. 1998. Mice deficient in group IV cytosolic phospholipase A2 are resistant to MPTP neurotoxicity. J. Neurochem. 71:2634–2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujishima, H., R.O. Sanchez Mejia, C.O. Bingham III, B.K. Lam, A. Sapirstein, J.V. Bonventre, K.F. Austen, and J.P. Arm. 1999. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 is essential for both the immediate and the delayed phases of eicosanoid generation in mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:4803–4807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakatani, N., N. Uozumi, K. Kume, M. Murakami, I. Kudo, and T. Shimizu. 2000. Role of cytosolic phospholipase A2 in the production of lipid mediators and histamine release in mouse bone-marrow-derived mast cells. Biochem. J. 352:311–317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagase, T., N. Uozumi, S. Ishii, K. Kume, T. Izumi, Y. Ouchi, and T. Shimizu. 2000. Acute lung injury by sepsis and acid aspiration: a key role for cytosolic phospholipase A2. Nat. Immunol. 1:42–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shindou, H., S. Ishii, N. Uozumi, and T. Shimizu. 2000. Roles of cytosolic phospholipase A2 and platelet-activating factor receptor in the Ca-induced biosynthesis of PAF. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 271:812–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takaku, K., M. Sonoshita, N. Sasaki, N. Uozumi, Y. Doi, T. Shimizu, and M.M. Taketo. 2000. Suppression of intestinal polyposis in Apc Δ 716 knockout mice by an additional mutation in the cytosolic phospholipase A2 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 275:34013–34016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong, K.H., J.C. Bonventre, E. O'Leary, J.V. Bonventre, and E.S. Lander. 2001. Deletion of cytosolic phospholipase A2 suppresses ApcMin-induced tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:3935–3939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Downey, P., A. Sapirstein, E. O'Leary, T.X. Sun, D. Brown, and J.V. Bonventre. 2001. Renal concentrating defect in mice lacking group IV cytosolic phospholipase A2. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 280:F607–F618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacPhee, M., K.P. Chepenik, R.A. Liddell, K.K. Nelson, L.D. Siracusa, and A.M. Buchberg. 1995. The secretory phospholipase A2 gene is a candidate for the Mom1 locus, a major modifier of ApcMin-induced intestinal neoplasia. Cell. 81:957–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kennedy, B.P., P. Payette, J. Mudgett, P. Vadas, W. Pruzanski, M. Kwan, C. Tang, D.E. Rancourt, and W.A. Cromlish. 1995. A natural disruption of the secretory group II phospholipase A2 gene in inbred mouse strains. J. Biol. Chem. 270:22378–22385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Funk, C.D., H. Gunne, H. Steiner, T. Izumi, and B. Samuelsson. 1989. Native and mutant 5-lipoxygenase expression in a baculovirus/insect cell system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 86:2592–2596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dejana, E., A. Callioni, A. Quintana, and G. de Gaetano. 1979. Bleeding time in laboratory animals. II - A comparison of different assay conditions in rats. Thromb. Res. 15:191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fabre, J.E., M. Nguyen, A. Latour, J.A. Keifer, L.P. Audoly, T.M. Coffman, and B.H. Koller. 1999. Decreased platelet aggregation, increased bleeding time and resistance to thromboembolism in P2Y1-deficient mice. Nat. Med. 5:1199–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gresele, P., C. Corona, P. Alberti, and G.G. Nenci. 1990. Picotamide protects mice from death in a pulmonary embolism model by a mechanism independent from thromboxane suppression. Thromb. Haemost. 64:80–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DiMinno, G., and M.J. Silver. 1983. Mouse antithrombotic assay: a simple method for the evaluation of antithrombotic agents in vivo. Potentiation of antithrombotic activity by ethyl alcohol. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 225:57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogletree, M.L., D.N. Harris, R. Greenberg, M.F. Haslanger, and M. Nakane. 1985. Pharmacological actions of SQ 29,548, a novel selective thromboxane antagonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 234:435–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Armstrong, R.A., and N.H. Wilson. 1995. Aspects of the thromboxane receptor system. Gen. Pharmacol. 26:463–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kattelman, E.J., D.L. Venton, and G.C. Le Breton. 1986. Characterization of U46619 binding in unactivated, intact human platelets and determination of binding site affinities of four TXA2/PGH2 receptor antagonists (13-APA, BM 13.177, ONO 3708 and SQ 29,548). Thromb. Res. 41:471–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Devchand, P.R., H. Keller, J.M. Peters, M. Vazquez, F.J. Gonzalez, and W. Wahli. 1996. The PPARα-leukotriene B4 pathway to inflammation control. Nature. 384:39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cyrus, T., J.L. Witztum, D.J. Rader, R. Tangirala, S. Fazio, M.F. Linton, and C.D. Funk. 1999. Disruption of the 12/15-lipoxygenase gene diminishes atherosclerosis in apo E-deficient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 103:1597–1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.George, J., A. Afek, A. Shaish, H. Levkovitz, N. Bloom, T. Cyrus, L. Zhao, C.D. Funk, E. Sigal, and D. Harats. 2001. 12/15-Lipoxygenase gene disruption attenuates atherogenesis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Circulation. 104:1646–1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Honn, K.V., D.G. Tang, X. Gao, I.A. Butovich, B. Liu, J. Timar, and W. Hagmann. 1994. 12-Lipoxygenases and 12(S)-HETE: role in cancer metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 13:365–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nie, D., K. Tang, C. Diglio, and K.V. Honn. 2000. Eicosanoid regulation of angiogenesis: role of endothelial arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase. Blood. 95:2304–2311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Escolar, G., and J.G. White. 2000. Changes in glycoprotein expression after platelet activation: differences between in vitro and in vivo studies. Thromb. Haemost. 83:371–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Offermanns, S., C.F. Toombs, Y.H. Hu, and M.I. Simon. 1997. Defective platelet activation in Gαq-deficient mice. Nature. 389:183–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leon, C., B. Hechler, M. Freund, A. Eckly, C. Vial, P. Ohlmann, A. Dierich, M. LeMeur, J.P. Cazenave, and C. Gachet. 1999. Defective platelet aggregation and increased resistance to thrombosis in purinergic P2Y1 receptor-null mice. J. Clin. Invest. 104:1731–1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hollopeter, G., H.M. Jantzen, D. Vincent, G. Li, L. England, V. Ramakrishnan, R.B. Yang, P. Nurden, A. Nurden, D. Julius, et al. 2001. Identification of the platelet ADP receptor targeted by antithrombotic drugs. Nature. 409:202–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Enjyoji, K., J. Sevigny, Y. Lin, P.S. Frenette, P.D. Christie, J.S. Esch II, M. Imai, J.M. Edelberg, H. Rayburn, M. Lech, et al. 1999. Targeted disruption of cd39/ATP diphosphohydrolase results in disordered hemostasis and thromboregulation. Nat. Med. 5:1010–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Daniel, J.L., C. Dangelmaier, J. Jin, Y.B. Kim, and S.P. Kunapuli. 1999. Role of intracellular signaling events in ADP-induced platelet aggregation. Thromb. Haemost. 82:1322–1326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jin, J., J.L. Daniel, and S.P. Kunapuli. 1998. Molecular basis for ADP-induced platelet activation. II. The P2Y1 receptor mediates ADP-induced intracellular calcium mobilization and shape change in platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 273:2030–2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Watson, S.P. 1999. Collagen receptor signaling in platelets and megakaryocytes. Thromb. Haemost. 82:365–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Judd, B.A., P.S. Myung, L. Leng, A. Obergfell, W.S. Pear, S.J. Shattil, and G.A. Koretzky. 2000. Hematopoietic reconstitution of SLP-76 corrects hemostasis and platelet signaling through αIIbβ3 and collagen receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:12056–12061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Briddon, S.J., and S.P. Watson. 1999. Evidence for the involvement of p59fyn and p53/56lyn in collagen receptor signalling in human platelets. Biochem. J. 338:203–209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Keely, P.J., and L.V. Parise. 1996. The α2β1 integrin is a necessary co-receptor for collagen-induced activation of Syk and the subsequent phosphorylation of phospholipase Cγ2 in platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 271:26668–26676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carroll, R.C., X.F. Wang, F. Lanza, B. Steiner, and W.C. Kouns. 1997. Blocking platelet aggregation inhibits thromboxane A2 formation by low dose agonists but does not inhibit phosphorylation and activation of cytosolic phospholipase A2. Thromb. Res. 88:109–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Borsch-Haubold, A.G., R.M. Kramer, and S.P. Watson. 1997. Phosphorylation and activation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 by 38-kDa mitogen-activated protein kinase in collagen-stimulated human platelets. Eur. J. Biochem. 245:751–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Inoue, K., Y. Ozaki, K. Satoh, Y. Wu, Y. Yatomi, Y. Shin, and T. Morita. 1999. Signal transduction pathways mediated by glycoprotein Ia/IIa in human platelets: comparison with those of glycoprotein VI. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 256:114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Suzuki-Inoue, K., Y. Ozaki, M. Kainoh, Y. Shin, Y. Wu, Y. Yatomi, T. Ohmori, T. Tanaka, K. Satoh, and T. Morita. 2001. Rhodocytin induces platelet aggregation by interacting with glycoprotein Ia/IIa (GPIa/IIa, Integrin α2β1). Involvement of GPIa/IIa-associated src and protein tyrosine phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 276:1643–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seno, K., T. Okuno, K. Nishi, Y. Murakami, F. Watanabe, T. Matsuura, M. Wada, Y. Fujii, M. Yamada, T. Ogawa, et al. 2000. Pyrrolidine inhibitors of human cytosolic phospholipase A2. J. Med. Chem. 43:1041–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]