Abstract

The molecular evolution of dotA, which is related to the virulence of Legionella pneumophila, was investigated by comparing the sequences of 15 reference strains (serogroups 1 to 15). It was found that dotA has a complex mosaic structure. The whole dotA gene of Legionella pneumophila subsp. pneumophila serogroups 2, 6, and 12 has been transferred from Legionella pneumophila subsp. fraseri. A discrepancy was found between the trees inferred from the nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of dotA, which suggests that multiple hits, resulting in synonymous substitutions, have occurred. Gene phylogenies inferred from three different segments (the 5′-end region, the central, large periplasmic domain, and the 3′-end region) showed impressively dissimilar topologies. This was concordant with the sequence polymorphisms, indicating that each region has experienced an independent evolutionary history, and was evident even within the same domain of each strain. For example, the PP2 domain was found to have a heterogeneous structure, which led us hypothesize that the dotA gene of L. pneumophila may have originated from two or more different sources. Comparisons of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions demonstrated that the PP2 domain has been under strong selective pressure with respect to amino acid change. Split decomposition analysis also supported the intragenic recombination of dotA. Multiple recombinational exchange within the dotA gene, encoding an integral cytoplasmic membrane protein that is secreted, probably provided increased fitness in certain environmental niches, such as within a particular biofilm community or species of amoebae.

The dotA gene encodes an integral cytoplasmic membrane protein (DotA) of Legionella pneumophila (29), the causative agent of Legionnaires' disease (13). DotA has eight hydrophobic transmembrane domains (29) and is related to the virulence of L. pneumophila (4, 41). It is known to prevent phagosome-lysosome fusion in macrophages (28, 42). The dotA gene is a component of the pathogenicity island, which contains the 24 dot/icm genes on two unlinked 22-kb regions on the L. pneumophila chromosome (30, 40). The Dot (defect in organelle trafficking)/Icm (intracellular multiplication) transporter is known to be a type IV secretion system (31). Moreover, L. pneumophila mutants defective in the Dot/Icm transporter system cannot replicate within macrophages or amoebae (2, 20, 28, 40).

Recently, it was reported that DotA is secreted extracellularly (24). In addition, there is significant similarity between the amino acid sequence of DotA and that of TraY of plasmid ColIb-P9 in Shigella sonnei (18, 32, 43).

As a component of a type IV transporter, TraY is involved in the conjugal transfer of the plasmid. The similarity between the Dot/Icm proteins of L. pneumophila and the Tra/Trb proteins in the ColIb-P9 plasmid of S. sonnei suggests that the dot/icm genes may have originated from such a plasmid (32). In addition, sequence homologies of the Dot/Icm system with the chromosomal sequences of Coxiella burnetii (32, 44) have also been found. C. burnetii is an intracellular pathogen which causes Q fever and is evolutionarily close to L. pneumophila. The IncI1 plasmid conjugation system of S. sonnei might have been transferred into an unknown common ancestor of Legionella and Coxiella (18). These findings suggest that the evolutionary origin of the dot/icm genes in L. pneumophila is complicated.

In a previous study, the possibility that horizontal gene transfer or intraspecies recombination had occurred in L. pneumophila was raised (17) on the basis of analysis of partial dotA sequences (360 bp). Ninety-six strains of L. pneumophila were classified into six subgroups (four subgroups in Legionella pneumophila subsp. pneumophila and two subgroups in Legionella pneumophila subsp. fraseri) on the basis of both rpoB and dotA gene sequences. However, the phylogenetic relationships between the subgroups generated from the dotA sequences differed dramatically from those for the housekeeping rpoB sequences. A similar result was mentioned in the report of Bumbaugh et al. (6), in which they compared dotA and mip gene sequences. However, the results obtained were insufficient to elucidate the molecular origin or evolution of dotA in L. pneumophila. Thus, we undertook this study to find definite evidence for horizontal gene transfer or intraspecies recombination of dotA by comparing nearly whole dotA sequences from all serogroups (SGs).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

L. pneumophila strains.

Fifteen L. pneumophila reference strains, representing SGs 1 to 15, were used in this study (Table 1). Of these, SGs 4, 5, and 15 belonged to L. pneumophila subsp. fraseri, and the rest belonged to L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila (5, 17). In the cases of SG 1 (ATCC 33152), SG 3 (ATCC 33155), SG 7 (ATCC 33823), and SG 12 (ATCC 43290), we used the dotA sequences of Bumbaugh et al. (6), as indicated in Table 1. The dotA DNA sequences determined in this study were submitted to GenBank, and the accession numbers of the 15 reference strains are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Reference strains of L. pneumophila used in this study

| Subspecies | Serogroup | Subgroupa | Strain | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila | 1 | P-I | ATCC 33152 (Philadelphia 1) | AF078136b |

| L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila | 2 | P-III | ATCC 33154 (Togus 1) | AY194414 |

| L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila | 3 | P-II | ATCC 33155 (Bloomington 2) | AF078138b |

| L. pneumophila subsp. fraseri | 4 | F-II | ATCC 33156 (Los Angeles 1) | AY194415 |

| L. pneumophila subsp. fraseri | 5 | F-I | ATCC 33216 (Dallas 1E) | AY194416 |

| L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila | 6 | P-III | ATCC 33215 (Chicago 2) | AY194417 |

| L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila | 7 | ATCC 33823 (Chicago 8) | AF078142b | |

| L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila | 8 | ATCC 35096 (Concord 3) | AY194418 | |

| L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila | 9 | P-I | ATCC 35289 (IN-23-G1-C2) | AY194419 |

| L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila | 10 | P-II | ATCC 43283 (Leiden 1) | AY194420 |

| L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila | 11 | ATCC 43130 (797-PA-H) | AY194421 | |

| L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila | 12 | P-III | ATCC 43290 (570-CO-H) | AF078147b |

| L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila | 13 | ATCC 43736 (82A3105) | AY194422 | |

| L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila | 14 | P-IV | ATCC 43703 (1169-MN-H) | AY194423 |

| L. pneumophila subsp. fraseri | 15 | F-II | ATCC 35251 (Lansing 3) | AY194424 |

dotA amplification and sequencing.

DNA was extracted using the bead beater-phenol extraction method, as previously described (17). To amplify nearly the whole dotA gene, two primer sets (1F-DL2 and DL1-DL4) were used (Table 2). PCRs were performed using 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 50 to 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. Template DNA (ca. 50 ng) and 20 pmol of each primer were added to a PCR mixture tube (AccuPower PCR PreMix; Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea), which contained 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 250 μM, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 40 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and gel loading dye. The final volume was adjusted to 20 μl with distilled water. The amplified PCR products were detected on 1.5% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide and were purified for sequencing by using a QIAEX II gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

TABLE 2.

Primers and their sequences used in this study

| Primer | Sequence | Locationc | Applicationd |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1F | 5′-TAG CTA TTA CGG TCC TCC-3′ | 11-28 | A, S |

| 1R | 5′-CCG GAT CAT TAT TAA CC-3′ | 1056-1072 | A, S |

| DL1a | 5′-TTG ATT TGG TGA AAC TCA ATG G-3′ | 1412-1433 | A, S |

| DL2a | 5′-CAA TCA AAA TCC TGG TGC TTC-3′ | 1821-1841 | A, S |

| DL3 | 5′-TGG GCA GGA GTG TAT GCT-3′ | 2764-2781 | A, S |

| DL4 | 5′-TTC GGG AGG TGG TGT ACT-3′ | 3178-3195 | A, S |

| 5Fbb | 5′-TCA ACA ATT CCA TGA TGG T-3′ | 1718-1736 | A, S |

| DL4bb | 5′-GGT ATA AAT TAA GAT GGA G-3′ | 2790-2808 | A, S |

| 2F | 5′-GGT TAT TGT ATG ATG CAG G-3′ | 357-376 | S |

| 3F | 5′-GTC AAG AAG CAA AGC GAT-3′ | 718-735 | S |

| 4F | 5′-GCY ATT GCC AAR CAG CA-3′ | 1120-1137 | S |

| 5F | 5′-CCG GGA ATA AAA CCG TT-3′ | 1753-1769 | S |

| 6F | 5′-CTG GTA CTT TGT GGT TAA-3′ | 2105-2122 | S |

| 7F | 5′-TTC TCT GAT GAT AAT AGG-3′ | 2442-2459 | S |

Primer set used by Ko et al. (17).

Primers used for amplification and sequencing of L. pneumophila subsp. fraseri (SGs 4, 5, and 15).

Locations in the aligned data set of nucleotide sequences.

A, amplification; S, sequencing.

Cycle sequencing was performed using an Applied Biosystems model 377 automated sequencer and a BigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom). For the sequencing reaction, 30 ng of purified PCR products, 2.5 pmol of primer, and 4 μl of BigDye terminator RR mix (no. 4303153; Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems) were mixed and adjusted to a final volume of 10 μl with distilled water. The reaction was run with 5% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide for 30 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 5 s at 50°C, and 4 min at 60°C.

Sequence alignment.

Raw sequences were analyzed and concatenated by DNASTAR (Madison, Wis.). Multiple alignments were accomplished with amino acid sequences inferred by using CLUSTAL X (39). Amino acid sequences were deduced with the MegAlign program of DNASTAR. Based on the alignments of deduced amino acid sequences, an aligned data set of nucleotide sequences was obtained.

Sequence analysis.

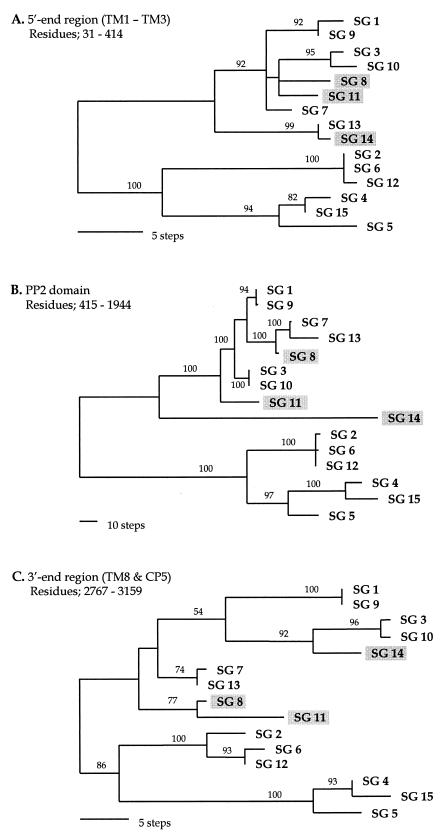

Phylogenetic trees were inferred from amino acid and nucleotide sequences by using the parsimony methods in PAUP (version 4; Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Mass.) and the midpoint rooting option. Phylogenies were evaluated from nucleotide sequences in three partitioned regions of dotA, respectively. The first part specified the 5′-end region (residues 31 to 414), which corresponds to a region from the first to the third transmembrane domain (TM1 to TM3). The second part corresponded to the second periplasmic domain (PP2; residues 415 to 1944), and the third included the 3′-end region (residues 2767 to 3159), which spans TM8 and the fifth cytoplasmic domain (CP5) (see Fig. 1 and 2). The branch supporting values were evaluated with 500 bootstrap replications (12, 15).

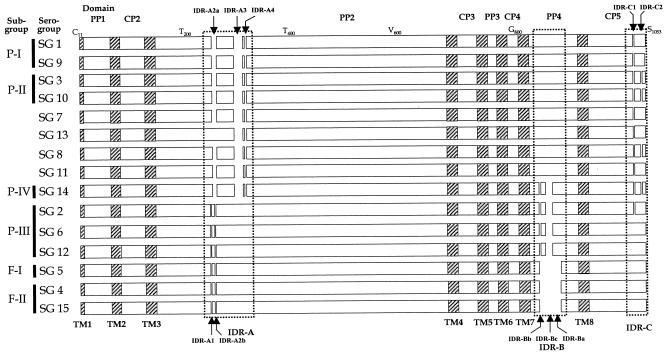

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the deduced DotA amino acid sequences of the 15 reference strains of L. pneumophila. Alignment gaps are shown as open spaces (1 in IDR-A1, 9 in IDR-A2, 19 in IDR-A3, 1 in IDR-A4, 28 in IDR-B, and 1 each in IDR-C1 and IDR-C2). Subgroups (17) are given on the left of each SG. Deduced amino acids given at the top are those of SG 1 (ATCC 33152) after multiple alignment. TM1 to TM8, eight transmembrane domains; PP1 to PP4, four periplasmic domains; CP2 to CP5, four cytoplasmic domains; IDR, insertion-deletion regions. The first cytoplasmic domain (CP1) at the 5′ end was excluded in this study because it corresponded to the position of primer 1F.

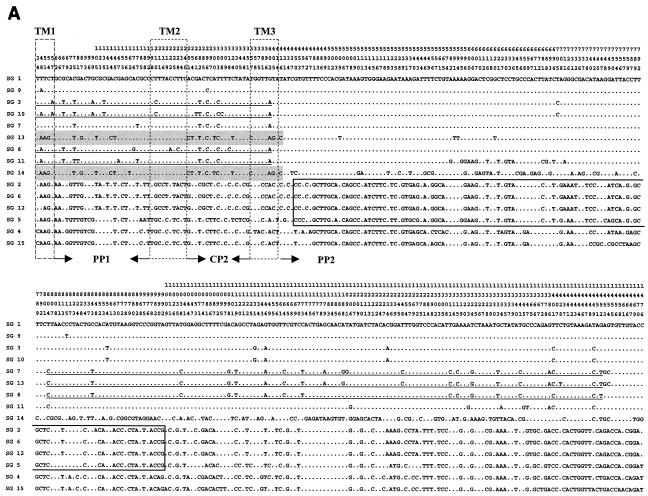

FIG. 2.

Polymorphic sites within the dotA gene of L. pneumophila. The nucleotides at each of the polymorphic sites in dotA from SG 1 (ATCC 33152) are shown. Nucleotides shared with SG 1 are indicated by dots. A total of 2,304 nucleotide sites are the same in all sequences, and there are 180 gaps (not shown). The position of each polymorphic site within dotA is given above the sequences; the numbers are to be read downward (e.g., the first is position 34). Shaded regions, nucleotide sequences shared with SG 14; underlined regions, nucleotide sequences shared with SG 8. Sequence regions of SG 5 shared with subgroup P-III (SGs, 2, 6, and 12) are boxed.

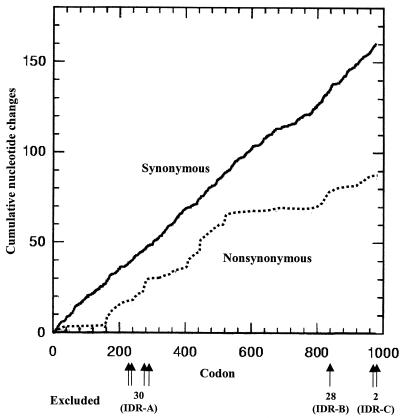

To investigate the effect of recombination on the evolutionary relationships among the SGs of L. pneumophila, a split decomposition tree was generated using the SPLITSTREE program (version 3.1) (16). Nucleotide substitution in dotA was analyzed by measuring the ratio of the number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (dS) to the number of nonsynonymous substitutions per nonsynonymous site (dN); these were calculated by using the SNAP program based on the method of Nei and Gojobori (25) and incorporated the statistics developed by Ota and Nei (26). This analysis was applied to all dotA sequences and to sequences of the TM, CP, and PP domains, as well as to those of the PP2 domain. Alignment gaps were excluded from the analysis.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The dotA sequences determined in this study have been submitted to GenBank under accession numbers AY194414 to AY194424.

RESULTS

dotA sequences.

Nearly whole dotA sequences were determined from all SGs of L. pneumophila in this study. Only 30 and 36 nucleotides at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, could not be included in the analysis due to the positions of primers and sequence ambiguity. From multiple alignment, we obtained 3,129 nucleotide and 1,043 deduced amino acid data sets of aligned dotA sequences including gaps.

The locations of the eight TM domains and gaps are indicated in Fig. 1. Three insertion-deletion regions, IDR-A (IDR-A1, -A2a, -A2b, -A3, and -A4), IDR-B (IDR-Ba, -Bb, and -Bc), and IDR-C (IDR-C1 and -C2), were found in the PP2, PP4, and CP5 domains, respectively. Strains belonging to the same subgroup, which had been previously classified from partial rpoB and dotA sequences (17), showed identical IDR patterns, except for SG 2 in P-III (Fig. 1). Figure 2 shows polymorphisms in the nucleotide sequence, excluding gaps (180 bp) in the aligned data set. The nucleotide polymorphism in the whole of the aligned sequences was 21.87% (645 of 2,949 nucleotides). Various levels of nucleotide sequence polymorphisms were observed in each domain (in the eight TM domains, 10.23% [48 of 469 nucleotides]; in the four CP domains, 19.65% [135 of 687 nucleotides]; and in the four PP domains, 25.77% [462 of 1,793 nucleotides]). However, the sequence polymorphism level of the amino acids was 18.64% (183 of 983 amino acids).

Heterogeneous similarity patterns of sequence polymorphisms and identities were observed in different regions of dotA in SG 14, SG 8, and SG 15. The sequence of a region (from the 5′ end to bp 416, including the TM1, PP1, TM2, CP2, and TM3 domains) of SG 14 was very similar (99.4% similarity) to the same region of SG 13 (Fig. 2A, shading). Another two regions, i.e., the region from bp 2529 to 2682 and the region from bp 2810 to the 3′ end of the SG14 sequence, were similar to those of SGs 2, 6, and 12 and to those of SGs 3 and 10 (Fig. 2B, shading), respectively. However, the dotA sequence of SG 14 in the other regions showed distinct nucleotide polymorphisms (Fig. 2).

The dotA sequence of SG 8 also showed a heterogeneous similarity in different regions. Its sequence from TM1 to TM3 (from the 5′ end to residue 402) was very similar (97.9 to 98.5%) to the corresponding sequences of SGs 3, 10, and 11 (Fig. 2A, underlining). However, SG 8 also showed a high sequence homology (99.1 to 99.4%) with SGs 7 and 13 in the PP2 domains (residues 804 to 1341) and had a sequence similarity of 97.7% with SG 11 in the CP5 domain (residues 2857 to 3117).

The SG 5 strain, which belongs to L. pneumophila subsp. fraseri, showed a dotA PP2 domain sequence (from residue 450 to 1035) similar (98.1 to 98.3%) to those of the L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila strains representing SGs 2, 6, and 12 (Fig. 2A, box). However, it also had sequences similar to those of the SG 4 and 15 strains, which are strains of L. pneumophila subsp. fraseri, in the other regions.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Phylogenetic relationships of L. pneumophila, inferred from almost-complete dotA nucleotide sequences and the deduced amino acid sequences, are shown in Fig. 3. Four subgroups (P-I to P-IV) of L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila and two subgroups (F-I and F-II) of L. pneumophila subsp. fraseri, which were defined in a previous report (17), also occurred in trees based on the full dotA sequences. Although incongruence exists in the positions of SGs 3 and 10, the two phylogenies from the nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences were similar. The clade of SGs 3 and 10, which was designated subgroup P-II, clustered with SGs 1 and 9 of subgroup P-I in the amino acid tree (Fig. 3B) but not in the nucleotide tree (Fig. 3A). Other incongruences, such as that in the position of SG 11 and that of the relationships among strains of subgroup P-III, also appeared in the two trees.

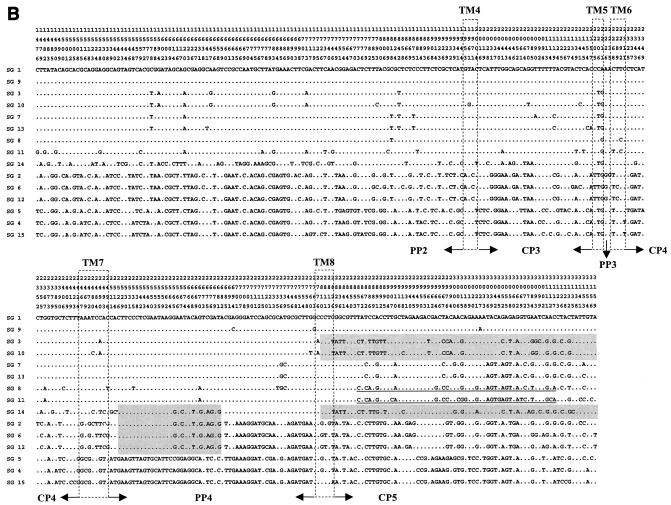

FIG. 3.

The most parsimonious trees inferred from nearly complete dotA sequences. (A) Tree from the nucleotide sequences, which required 975 steps; CI = 0.834; RI = 0.918. (B) Tree from deduced amino acids, which required 281 steps; CI = 0.904; RI = 0.950. The midpoint rooting method was used to root the trees. Subgroups (17) are indicated by dotted vertical lines on the right. Branch lengths are proportional to changes in the nucleotides or amino acids. Branches supported by values higher than 50% in the bootstrap analysis (500 replications) are indicated.

Phylogenetic trees constructed with the sequences of three different regions (the 5′-end region, the PP2 domain, and the 3′-end region) showed significantly different topologies (Fig. 4). First, the positions of SG 14 in the different trees were dramatically different. SG14 clustered with SG 13 in the tree based on the 5′-end region sequence, which was supported robustly by bootstrap analysis (99%) (Fig. 4A). However, it did not group with any other strain in the PP2 domain tree (Fig. 4B), and it grouped with SGs 3 and 10 in the 3′-end region tree (bootstrap supporting value, 92%) (Fig. 4C). Second, the positions of SG 8 in the different trees were also inconsistent. Although SG 8 was grouped with SGs 3, 10, and 11 in the tree of the 5′-end region despite a low bootstrap supporting value (Fig. 4A), it had a close relationship with SGs 7 and 13 in the PP2 domain tree, with complete support by bootstrap analysis (100%) (Fig. 4B), and it clustered only with SG 11 in the 3′-end region tree (bootstrap supporting value, 77%) (Fig. 4C). SG 11 did not cluster with any other strains in the PP2 domain tree (Fig. 4B), while it had a close relationship with SG 8 in the trees of the 5′- and 3′-end regions (Fig. 4A and C). These incongruent positions of different dotA regions were almost identical to the alignment patterns in sequence comparisons (Fig. 1 and 2).

FIG. 4.

Gene phylogenies inferred from three regions of the dotA gene. These trees were constructed from nucleotide sequences by parsimony analysis. (A) One of the six most parsimonious trees (87 steps) inferred from the 5′-end regions corresponding to TM1 to TM3 (residues 31 to 414); CI = 0.851; RI = 0.930. (B) The unique parsimonious tree (531 steps) constructed from the PP2 domain of residues 415 to 1944; CI = 0.887; RI = 0.948. (C) One of the four most parsimonious trees from the 3′-end regions, corresponding to the TM8 and CP5 domains (residues 2767 to 3159); CI = 0.748; RI = 0.845. The branch lengths are proportional to changes in the nucleotides. The numbers on the branches are the percentages of support from bootstrap analysis (500 replications). The three strains that have different positions in the three phylogenies are shaded.

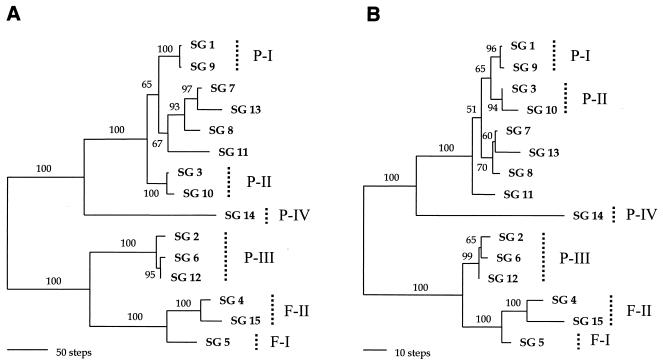

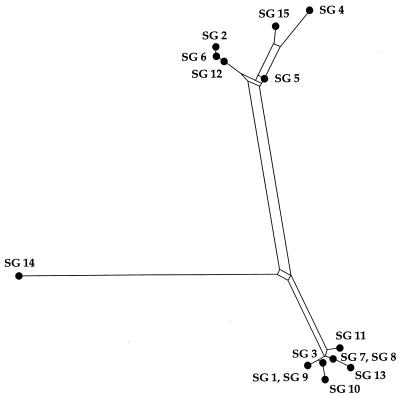

To examine how the recombination of dotA can affect the phylogenetic relationships among the serogroups, split decomposition analysis (3) was performed. The fit parameter of the split graph was 0.81, and the split graph showed evidence of a network-like evolution, consistent with recombination (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Split graph showing the relationships among the 15 reference strains of L. pneumophila. The split graph was generated by using SPLITSTREE, version 3.1 (16), from the pairwise distances of the sequences of the dotA gene based on the Kimura two-parameter model. The fit value was 0.81, indicating that the phylogenetic signal in the data was represented moderately well by the split graph. The network indicates the lack of a treelike relationship between the dotA sequences. All branch lengths are drawn to scale.

Heterogeneity of nucleotide substitutions.

The degree of selective constraint on the deduced amino acid sequence can be inferred from the dS/dN ratio. The overall dS/dN ratio for dotA was much larger than 1 (dS/dN = 9.65). However, the ratio differed for the different domains. The ratios of the CP and PP domains decreased to 3.37 and 1.45, respectively. Moreover, the ratio of the PP2 domains was much smaller than 1 (0.49) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Ratio of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (dS) to nonsynonymous substitutions per nonsynonymous site (dN)

| Region | dS | dN | dS/dN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole gene | 0.33 | 0.04 | 9.65 |

| TM domainsa | 0.22 | <0.01 | 33.84 |

| CP domainsb | 0.17 | 0.05 | 3.37 |

| PP domainsc | 0.15 | 0.11 | 1.45 |

| PP2 domain | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.49 |

Eight putative transmembrane domains.

Four cytoplasmic domains (CP2, CP3, CP4, and CP5).

Four periplasmic domains (PP1, PP2, PP3, and PP4).

Cumulative increases in synonymous and nonsynonymous changes through dotA were plotted against the codon numbers. The number of synonymous substitutions increased linearly, while the number of nonsynonymous substitutions did not (Fig. 6). The rate of increase in nonsynonymous changes was lower than the rate of increase in synonymous changes in most regions. However, the number of nonsynonymous substitutions increased dramatically in a region of the PP2 domains (from amino acid residue 160 to 520) (Fig. 6). The low dS/dN ratio (<1) of the PP2 domains might be caused by this abrupt increase in nonsynonymous changes.

FIG. 6.

Cumulative increases in synonymous (solid line) and nonsynonymous (dotted line) substitutions in dotA sequences. This graph was generated by using the SNAP program, obtained from an Internet website (http://www.mlst.net). In this analysis, all alignment gaps (30 in IDR-A, 28 in IDR-B, and 2 in IDR-C) were excluded; positions and numbers of codons are indicated below the x axis. The y axis indicates the cumulative number of nucleotides causing synonymous or nonsynonymous amino acid changes.

DISCUSSION

Our comparison of the almost-complete dotA sequences of L. pneumophila showed extensive polymorphism. Although great sequence divergence in dotA was reported previously (6, 17), an unexpected and marked heterogeneity of dotA in several strains was newly observed in this study. Although strains of SGs 2, 6, and 12 belong to L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila (subgroup P-III), they were found to be closely related to strains of L. pneumophila subsp. fraseri. This is consistent with the result of a previous study using partial dotA sequences (17). The close relatedness of strains of L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila to strains of L. pneumophila subsp. fraseri by whole dotA sequence analysis may indicate that a segment including the total dotA gene might have been transferred from L. pneumophila subsp. fraseri to one subgroup (P-III) of L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila. However, genes other than dotA in the pathogenicity islands of subgroup P-III do not show a close relationship to the corresponding genes of L. pneumophila subsp. fraseri (unpublished data). In this respect, it is plausible that a partial segment, including the dotA gene within the pathogenicity islands, might have been transferred among the subgroups of L. pneumophila.

Discrepancy between trees based on nucleotide and amino acid sequences (Fig. 3) may suggest that several synonymous mutations have occurred at the same sites. Multiple hits at a single site, which cause a saturation of base substitution, can prevent one from inferring true evolutionary events. Such multiple hits may result in synonymous substitutions in the genes encoding functional proteins, which may obscure phylogenetic relationships (27). Considering the consistency and retention indices (CI and RI, respectively) of nucleotide and deduced amino acid data sets (Fig. 3), loss of phylogenetic signals in the nucleotide data set may be related to such multiple hits (34). The slight divergence of the deduced amino acid sequences of SGs 7, 8, 11, and 13, SGs 1 and 9 (subgroup P-I), and SGs 3 and 10 (subgroup P-II) may indicate that their divergence is recent. Also, the differentiation of serogroups within subgroup P-III may be recent, which suggests that the factors determining the serogroup of L. pneumophila may be a restricted to a gene product (33) that seldom varies.

The phylogenetic positions of SGs 8, 11, and 14 did not coincide in the tree constructed with the sequences of different regions (Fig. 4). Sequence comparisons also indicated quite different similarities depending on the regions compared (Fig. 1 and 2). This inconsistency can be explained by intragenic recombination among the strains of L. pneumophila. In other words, the dotA gene of L. pneumophila may have a mosaic structure composed of segments with different histories, as has demonstrated for intimins of pathogenic Escherichia coli (21). The result of network-like phylogeny by split decomposition analysis (Fig. 5) also supports the notion of intragenic recombination events in dotA. Because this analysis does not make an a priori assumption of a tree-like process of sequence divergence, conflicting phylogenetic signals in the data, such as evidence of recombination, will generate an interconnected network rather than a tree (1, 9, 35, 37).

There are good examples of bacterial genes composed of diverse segments with different histories; i.e., intimin in pathogenic E. coli (21, 38), the leukotoxin operon in Pasteurella species (8), the capsular biosynthetic locus and penicillin-binding protein in Streptococcus pneumoniae (7, 11), and the outer membrane protein (ompA) in Chlamydia species (22). Genes that exhibit such mosaic structures mainly encode proteins that either are extracellularly secreted, are exposed on the cell surface, or act as virulence factors (19). The mosaicism of dotA was suspected in a previous study, which used a portion of the dotA sequence (17), and this was supported by a report that DotA is a secretory protein (24). In addition, L. pneumophila has been reported to be naturally transformable (23, 36), and its competence makes it possible to exchange portions of genes naturally (14, 23).

Comparison of synonymous and nonsynonymous mutations has also shown that dotA does not have a homogeneous structure. A dS/dN ratio that exceeds 1 means that there is negative selection for amino acid change. On the other hand, a dS/dN ratio less than 1 indicates positive selection for amino acid substitution (10, 26). The highest dS/dN ratio of the TM domains in dotA of L. pneumophila (33.84) indicates that it is under a strong negative selective constraint. However, that of the PP domains was close to 1, and the ratio was lower than 1 in the PP2 domain. This means that the periplasmic regions in dotA are under strong positive pressure for amino acid change, or relaxed selective constraint. Interestingly, the PP2 domain shares little similarity with TraY of plasmid ColIb-P9 in spite of the overall similarity between dotA and traY (18, 43). This suggests that the PP2 domain has evolved in a different manner from the other regions of dotA. Thus, dotA is believed to have a mosaic structure due to transfer from two or more origins and to have experienced an extremely complicated evolutionary history even within a single domain.

In addition, individual domains within dotA have heterogeneous structures. In a region within the PP2 domain, the sequence of SG 5 of L. pneumophila subsp. fraseri was similar to those of SGs 2, 6, and 12 of L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila (Fig. 2). The sequence of the PP2 domain in SG 8 (residues 804 to 1452) was very similar to those of SGs 7 and 13, while they were clearly different in other regions (Fig. 2). Moreover, nonsynonymous substitutions did not increase linearly after amino acid residue 520 in the PP2 domain (Fig. 6). Therefore, it must be the case that the dotA gene of L. pneumophila has been exposed to high recombinational pressure.

DotA, as mentioned above, is a secreted protein, which is assembled into a ring-shaped structure with a central channel. It has been hypothesized that the conserved TM domains of DotA play an important role in assembly that is necessary for secretion (24). The heterogeneous characteristics of the PP2 domain sequences may affect the structure of DotA. However, little is known about the secretion of DotA, though the high rate of amino acid change and frequent recombination events in the PP2 domain may be related to the secretion mechanism.

In conclusion, this study shows that the dotA gene of L. pneumophila has a complex mosaic structure produced by multiple intragenic recombinations. The PP2 domain, the largest periplasmic domain of DotA, exhibits the highest variability and shows a strong positive selection for amino acid substitution. Amino acid substitutions of the virulence gene can affect the fate of intracellular pathogens. DotA affects the ability of L. pneumophila to prevent phagolysosome fusion and to survive within macrophages (4). Thus, the rapid evolution of dotA via multiple recombination and frequent nonsynonymous mutations has provided L. pneumophila with increased fitness in certain environmental niches, such as within a particular biofilm community or species of amoebae, by generating novel antigenic variations at surface-exposed sites.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant of the Korea Health 21 R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Seoul, Republic of Korea (01-PJ10-PG6-01GM03-0002), and in part by the BK21 project for Medicine, Dentistry, and Pharmacy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alber, D., M. Oberkõtter, S. Suerbaum, H. Claus, M. Frosch, and U. Vogel. 2001. Genetic diversity of Neisseria lactamia strains from epidemiologically defined carriers. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1710-1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews, H. L., J. P. Vogel, and R. R. Isberg. 1998. Identification of linked Legionella pneumophila gene essential for intracellular growth and evasion of the endocytic pathway. Infect. Immun. 66:950-958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandelt, H. J., and A. W. Dress. 1992. Split decomposition: a new and useful approach to phylogenetic analysis of distance data. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1:242-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger, K. H., J. J. Merriam, and R. R. Isberg. 1994. Altered intracellular targeting properties associated with mutations in the Legionella pneumophila dotA gene. Mol. Microbiol. 14:809-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner, D. J., A. G. Steigerwalt, P. Epple, W. F. Bibb, R. M. McKinney, R. W. Starnes, J. M. Colville, R. K. Selander, P. H. Edelstein, and C. Wayne Moss. 1988. Legionella pneumophila serogroup Lansing 3 isolated from a patient with fatal pneumonia, and descriptions of L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila subsp. nov., L. pneumophila subsp. fraseri subsp. nov., and L. pneumophila subsp. pascullei subsp. nov. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:1695-1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bumbaugh, A. C., E. A. McGraw, K. I. Page, R. K. Selander, and T. S. Whittam. 2002. Sequence polymorphism of dotA and mip alleles mediating invasion and intracellular replication of Legionella pneumophila. Curr. Microbiol. 44:314-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffey, T. J., M. C. Enright, M. Daniels, J. K. Morona, R. Morona, W. Hryneiwicz, J. C. Paton, and B. G. Spratt. 1998. Recombinational exchange at the capsular polysaccharide biosynthetic locus leads to frequent serotype changes among natural isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 27:73-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies, R. L., S. Campbell, and T. S. Whittam. 2002. Mosaic structure and molecular evolution of the leukotoxin operon (ltkCABD) in Mannheimia (Pasteurella) haemolytica, Manheimia glucosida, and Pasteurella trehalosi. J. Bacteriol. 184:266-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derrick, J. P., R. Urwin, J. Suker, I. M. Feavers, and M. C. J. Maiden. 1999. Structural and evolutionary inference from molecular variation in Neisseria porins. Infect. Immun. 67:2406-2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dingle, K. E., F. M. Colles, D. R. A. Wareing, R. Ure, A. J. Fox, F. E. Bolton, H. J. Bootsma, R. J. L. Willems, R. Urwin, and M. C. J. Maiden. 2001. Multilocus sequence typing system for Camplylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:14-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enright, M. C., and B. G. Spratt. 1999. Extensive variation in the ddl gene of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae results from a hitchhiking effect driven by the penicillin-binding protein 2b gene. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16:1687-1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felsenstein, J. 1985. Confidence limits in phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fraser, D. D., D. L. Tsai, W. Orenstein, W. E. Parkin, H. J. Beecham, R. G. Sharrar, J. Harris, G. F. Mallison, S. M. Martin, J. E. McDade, C. C. Shepard, and P. S. Brachman. 1977. Legionnaires' disease: description of an epidemic of pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 297:1189-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Håvarstein, L. S., R. Hakenbeck, and P. Gaustad. 1997. Natural competence in the genus Streptococcus: evidence that streptococci can change pherotype by interspecies recombinational exchanges. J. Bacteriol. 179:6589-6594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hillis, D. M., and J. J. Bull. 1993. An empirical test of bootstrapping as a method for assessing confidence in phylogenetic analysis. Syst. Biol. 42:182-192. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huson, D. H. 1998. SplitsTree: a program for analyzing and visualizing evolutionary data. Bioinformatics 14:68-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ko, K. S., H. K. Lee, M.-Y. Park, M.-S. Park, K.-H. Lee, S.-Y. Woo, Y.-J. Yun, and Y.-H. Kook. 2002. Population genetic structure of Legionella pneumophila inferred from RNA polymerase gene (rpoB) and DotA gene (dotA) sequences. J. Bacteriol. 184:2123-2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komano, T., T. Yoshida, K. Narahara, and N. Furuya. 2000. The transfer region of IncI1 plasmid R64: similarities between R64 tra and Legionella icm/dot genes. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1348-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, J., H. Ochman, E. A. Groisman, E. F. Boyd, F. Solomon, K. Nelson, and R. K. Selander. 1995. Relationship between evolutionary rate and cellular location among the Inv/Spa invasion proteins of Salmonella enterica. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:7252-7256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matthews, M., and C. R. Roy. 2000. Identification and subcellular localization of the Legionella pneumophila IcmX protein: a factor essential for establishment of a replicative organelle in eukaryotic host cells. Infect. Immun. 68:3971-3982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGraw, E. A., J. L. Robert. R. K. Selander, and T. S. Whittams. 1999. Molecular evolution and mosaic structure of α, β, and γ intimins of pathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16:12-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Millman, K., L. S. Tavaré, and D. Dean. 2001. Recombination in the ompA gene but not the omcB gene of Chlamydia contributes to serovar-specific differences in tissue tropism, immune surveillance, and persistence of the organism. J. Bacteriol. 183:5997-6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mintz, C. S. 1999. Gene transfer in Legionella pneumophila. Microbes Infect. 1:1203-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagai, H., and C. R. Roy. 2001. The DotA protein from Legionella pneumophila is secreted by a novel process that requires the Dot/Icm transporter. EMBO J. 20:5962-5970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nei, M., and T. Gojobori. 1986. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 3:418-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ota, T., and M. Nei. 1994. Variance and covariance of the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions per site. Mol. Biol. Evol. 11:613-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Page, R. D. M., and E. C. Holmes. 1998. Molecular evolution: a phylogenetic approach. Blackwell Science, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 28.Roy, C. R., and R. R. Isberg. 1997. Topology of Legionella pneumophila DotA: an inner membrane protein required for replication in macrophages. Infect. Immun. 65:571-578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roy, C. R., K. H. Berger, and R. R. Isberg. 1998. Legionella pneumophila DotA protein is required for early phagosome trafficking decisions that occur within minutes of bacterial uptake. Mol. Microbiol. 28:663-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Segal, G., M. Purcell, and H. A. Shuman. 1998. Host cell killing and bacterial conjugation require overlapping sets of genes within a 22-kb region of the Legionella pneumophila genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:1669-1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Segal, G., J. J. Russo, and H. A. Shuman. 1999. Relationships between a new type IV secretion system and the icm/dot virulence system of Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Microbiol. 34:799-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Segal, G., and H. A. Shuman. 1999. Possible origin of the Legionella pneumophila virulence genes and their relation to Coxiella burnetii. Mol. Microbiol. 33:669-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Selander, R. K., R. M. McKinney, T. S. Whittam, W. F. Bibb, D. J. Brenner, F. S. Nolte, and P. E. Pattison. 1985. Genetic structure of populations of Legionella pneumophila. J. Bacteriol. 163:1021-1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siebert, D. J. 1992. Tree statistics, p. 72-88. In P. L. Forey, C. J. Humphries, I. J. Kitching, R. W. Scotland, D. J. Siebert, and D. M. Williams (ed.), Cladistics: a practical course in systematics. Clarendon Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 35.Smith, N. H., E. C. Holmes, G. M. Donovan, G. A. Carpenter, and B. G. Spratt. 1999. Networks and groups within the genus Neisseria: analysis of argF, recA, rho, and 16S rRNA sequences from human Neisseria species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16:773-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stone, B. J., and Y. A. Kwaik. 1999. Natural competence for DNA transformation by Legionella pneumophila and its association with expression of type IV pili. J. Bacteriol. 181:1395-1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suerbaum, S., M. Lohrengel, A. Sonnevend, F. Ruberg, and M. Kist. 2001. Allelic diversity and recombination in Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 183:2553-2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tarr, C. L., and T. S. Whittam. 2002. Molecular evolution of the intimin gene in O111 clones of pathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:479-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The Clustal X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vogel, J. P., H. L. Andrew. S. K. Wong, and R. R. Isberg. 1998. Conjugation transfer by the virulence system of Legionella pneumophila. Science 279:873-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vogel, J. P., and R. R. Isberg. 1998. Cell biology of Legionella pneumophila. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:30-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiater, L. A., K. K. Dunn, F. R. Maxfield, and H. A. Shuman. 1998. Early events in phagosome establishment are required for intracellular survival of Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 66:4450-4460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilkins, B. M., and A. T. Thomas. 2000. DNA-independent transport of plasmid primase protein between bacteria by the I1 conjugation system. Mol. Microbiol. 38:650-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Willems, H., C. Jäger, and G. Baljer. 1998. Physical and genetic map of the obligate intracellular bacterium Coxiella burnetii. J. Bacteriol. 180:3816-3822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]