Abstract

Asthma is caused by memory Th2 cells that often arise early in life and persist after repeated encounters with allergen. Although much is known regarding how Th2 cells develop, there is little information about the molecules that regulate memory Th2 cells after they have formed. Here we show that the costimulatory molecule OX40 is expressed on memory CD4 cells. In already sensitized animals, blocking OX40–OX40L interactions at the time of inhalation of aerosolized antigen suppressed memory effector accumulation in lung draining lymph nodes and lung, and prevented eosinophilia, airway hyperreactivity, mucus secretion, and Th2 cyto-kine production. Demonstrating that OX40 signals directly regulate memory T cells, antigen-experienced OX40-deficient T cells were found to divide initially but could not survive and accumulate in large numbers after antigen rechallenge. Thus, OX40–OX40L interactions are pivotal to the efficiency of recall responses regulated by memory Th2 cells.

Keywords: OX40, asthma, memory T cells, Th2, allergy

Introduction

Memory Th2 cells secreting the cytokines IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13 are the major driving force behind allergic asthma and these CD4 cells are thought in many cases to arise early in life during infancy (1, 2). Although the immunological mechanisms that result in the development of Th2 cells are fairly well characterized, there is a lack of knowledge regarding how an already formed memory Th2 cell is regulated. Hence, it is not clear if there are certain molecular interactions that could be targeted to either suppress ongoing lung inflammation or to prevent the reoccurrence of asthmatic symptoms when airborne allergens are repeatedly encountered.

Apart from TCR signals that arise from peptide/MHC recognition, the most likely sources of positive signals that could affect longevity and/or reactivity of memory T cells are membrane bound costimulatory molecules of the Ig and TNFR superfamilies. Although there is abundant data on the requirement of members of these families in controlling priming of naive T cells and hence dictating the development of memory Th2 cells, there is little data on whether they can influence reactivity or persistence of a memory T cell once it has been generated. In fact several groups postulated that memory T cells are less dependent, or independent, of costimulation, largely based on negative data obtained from analyses of the Ig family member CD28 (3–8).

In contrast to CD28, it has become clear in the past few years that a number of additional receptors exist that could be crucial to a T cell response. Most significantly, recent data on OX40 (CD134), a member of the TNFR family, has shown that it is a major regulator of antiapoptotic proteins such as Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 and strongly promotes the survival of antigen-activated primary CD4 T cells (9–11). OX40 is not constitutively expressed on naive T cells but is induced in a primary immune response 24–48 h after recognition of antigen (9, 12–14). OX40L, a member of the TNF family, is also inducible (9, 14, 15) being expressed on activated B cells (15, 16), dendritic cells (17), and macrophage-like cells (18). The importance of OX40 costimulation in priming naive T cells has been demonstrated in a variety of basic and disease-related systems using OX40- and OX40L-deficient animals, and in blocking studies (10, 11, 18–27). However, to date no studies have addressed whether OX40–OX40L interactions contribute to the maintenance and functionality of antigen-specific memory T cells.

OX40 is down-regulated to low levels after the effector phase of primary T cell responses, and antigen-primed CD4 T cells can rapidly up-regulate its expression upon reencounter with antigen (9). Similarly, an anergic T cell, which also represents an antigen-experienced cell, albeit functionally hyporesponsive, can also express OX40 at low levels and be receptive to OX40 engagement resulting in enhanced functionality (28). These observations suggest that, similar to naive T cells, OX40 may play an important role in a range of memory T cell activities, including survival and effector function. Hence, OX40 may be an attractive target for suppressing already formed memory Th2 cells that mediate allergic asthma.

In the present study we demonstrate that some CD4 cells in an already sensitized animal express OX40 and that costimulation through this molecule is critical for all aspects of lung inflammation driven by these memory Th2 cells. These studies directly show that the recall response of memory T cells is not costimulation independent, and can be controlled by OX40 signals. They also suggest that targeting OX40–OX40L interactions may be useful therapeutically for the modulation of ongoing chronic inflammation in allergic disorders.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

The studies reported here conform to the principles outlined by the animal Welfare Act and the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of animals in biomedical research. 6–8-wk-old female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. OT-II TCR transgenic mice, originally generated by Barnden et al. (29), were a gift from Dr. W. Heath, and used as a source of Vβ5/Vα2 CD4+ T cells responsive to peptide 323–339 of OVA. OX40-deficient OT-II TCR transgenic mice were generated in house by crossing OT-II mice with OX40−/− mice.

Induction of Allergic Airway Inflammation.

The protocol for induction of pulmonary inflammation via antigen sensitization and aerosol challenge has been described previously (22). Briefly, groups of 4 C57BL/6 mice were sensitized by i.p. injection of 20 μg OVA protein (chicken egg albumin; Sigma-Aldrich), adsorbed to 2 mg aluminum hydroxide (Alum; Pierce Chemical Co.) in PBS on day 0. Unsensitized (naive) mice received 2 mg Alum in PBS. On day 25 or later, mice were challenged via the airways with OVA (5 mg/ml in 15 ml of PBS) for 30 min, once a day for four consecutive days, by ultrasonic nebulization (22). To block OX40–OX40L interaction, mice were injected i.p. with 200 μg of rat anti–mouse-OX40L blocking mAb (RM134L, rat IgG2bκ; reference 30) or isotype control antibody IgG2b; given on the indicated days in PBS, 30 min before OVA challenge.

Analysis of the Asthma Phenotype.

Airway hyperreactivity (AHR)*was measured in vivo 1–3 h after the last aerosolized OVA exposure by recording respiratory curves by whole-body plethysmography (Buxco Technologies) in response to inhaled methacholine (MCh; 1.25–10 mg/ml; Aldrich Chemical) as described (22). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cytology, lung histopathology, OVA-specific and total IgE and lung cytokine profiles obtained by ELISA were determined as described (22). All data unless otherwise stated were collected 24 h after the final antigen challenge.

Stimulation of Lung, Peribronchial Lymph Node, and Spleen Cells In Vitro.

Peribronchial lymph nodes (PBLNs) and spleens were collected at the time of lung harvest. Lavaged lungs were digested with HBSS (GIBCO BRL) supplemented with 3 mg/ml collagenase (Type V; Boehringer), 0.1 mg/ml Dnase (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 100 U/ml penicillin (Invitrogen) for 60 min at 37°C. After lysing RBCs with ACK lysis buffer, PBLN, spleen, and lung cells were resuspended in RPMI-1640 medium (GIBCO BRL) supplemented with 10% FCS (Omega Scientific), 1% l-glutamine (Invitrogen), 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich). Splenocytes (2 × 105 cells/well), lung cells (8 × 105 cells/well), or PBLN cells (2 × 105 cells/well) were plated in round-bottomed 96-well microtiter plates in 200 μl with increasing concentrations of OVA (10–100 μg/ml) for 72 h at 37°C. After 56 h, 1 μCi of 3H-thymidine (ICN Biomedicals) was added to each well. The cells were harvested 16 h later, and thymidine incorporation measured using a Betaplate scintillation counter. Each in vitro stimulation was performed in quadruplicates. Supernatants were harvested after 40 h for cytokine analysis.

Generation and Adoptive Transfer of OVA-specific Th2 Cells.

Lymph node and spleen cells from wild-type (OX40+/+) OT-II mice or OT-II OX40-deficient (OX40−/−) mice were pooled and CD4 cells isolated as described previously (9). The purity of CD4+ T cells was confirmed to be >98% by FACS® analysis. To generate memory Th2 cells, naive T cells (106 cells/ml) were cultured in two ways: with plate-bound αCD3 (3 μg/ml) and soluble αCD28 (10 μg/ml), or with 2 × 106/ml syngeneic splenic APCs and 0.1 μM OVA peptide, plus IL-2 (5 ng/ml), IL-4 (20 ng/ml), αIFN-γ (10 μg/ml), and αIL-12 (10 μg/ml), for 3 d at 37°C. At the end of this culture, cells were removed, washed, and then cultured for another 3–6 d without further stimulation.

In some cases, primed T cells were labeled with CFSE (5- and 6-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester C-1157; Molecular Probes) and 2 × 106 were injected into the tail vain of naive C57BL/6 mice in 200 μl. 1 d after transfer of cells, mice were challenged with inhaled OVA (5 mg/ml in 15 ml PBS) for 30 min daily for 2 consecutive days. Animals were killed for analyses 1 d later. Control mice received inhaled PBS only. In vivo cell division and T cell accumulation were assessed by tracking transferred T cells by flow cytometry based on coexpression of CFSE and Vα2.

At the end of the primary culture, an aliquot of primed T cells were retained to determine proliferation, survival, and cytokine production in recall responses in vitro. 5 × 105 CD4 T cells/ml were recultured with 2 × 106/ml syngeneic splenic APCs and OVA peptide. IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IFN-γ levels from cell supernatants were determined by ELISA at 40 h. Proliferation was measured in triplicate by the incorporation of 3H-thymidine (1 μCi/well; ICN Pharmaceuticals) during the last 12 h of culture. T cell survival was determined by trypan blue exclusion.

Flow Cytometry Analysis.

Cells were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD4, PE-conjugated anti-OX40, Cychrome-conjugated anti-CD44, or PE-conjugated anti-Vα2 at 4°C for 30 min. Immunostained cells were analyzed on a FACScan™ flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) using the CELLQuest™ software.

Results

OX40 Is Expressed on Memory Th2 Cells.

Characteristic features of allergic asthma are produced when mice are sensitized with OVA, and subsequently challenged several weeks later by inhalation of OVA (1, 22). Using OX40-deficient mice, we previously showed the importance of OX40 in controlling initial development of asthma symptoms (22). However, as these mice are defective in generating a primary T cell response (10, 11), no conclusions could be drawn regarding any requirement for OX40 in the secondary response of the memory T cell that ultimately induces lung inflammation.

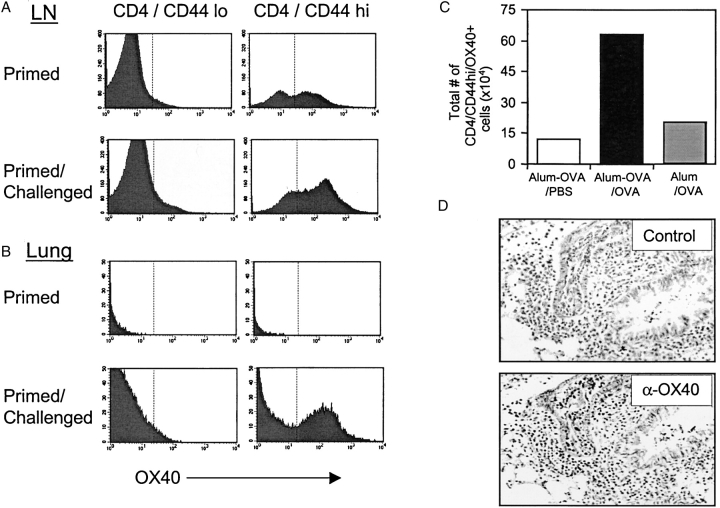

We initially looked to see if memory CD4 cells express OX40. By staining T cells from mice primed 4 wk prior with OVA in alum, we visualized a significant number of CD44hi memory CD4 cells in lymph nodes that expressed OX40 at low/moderate levels. In contrast, as shown previously (9), CD44lo naive CD4 cells did not express OX40 without antigen exposure (Fig. 1 A). Unimmunized mice also contained a proportion of CD44hi CD4 cells that expressed OX40 at low levels (unpublished data), suggesting that OX40 can be readily available to some memory T cells. OX40 levels were up-regulated on responding CD44hi memory T cells in lung draining lymph nodes after challenge with aerosolized antigen (Fig. 1 A), and the absolute number of OX40 positive CD44hi CD4 cells increased markedly (Fig. 1 C, and see below). As this large increase in the number of OX40-expressing CD44hi cells was not seen in unprimed mice challenged with aerosolized antigen, the latter directly reflects the response of memory T cells and accumulation of memory effector cells.

Figure 1.

OX40 is expressed on memory and memory effector T cells. Groups of four C57BL/6 mice were immunized i.p. with OVA adsorbed to alum (primed). 25 d later mice were challenged by inhalation of nebulized OVA on 4 consecutive days (primed/challenged). (A) Peribronchial lymph nodes or (B) lungs were examined for expression of OX40 on CD4/CD44lo or CD4/CD44hi T cells. (C) Total numbers of OX40 positive CD4/CD44hi T cells (mean of 4 mice) were quantitated in lymph nodes from primed mice challenged with PBS (Alum-OVA/PBS), primed mice challenged with OVA (Alum-OVA/OVA), or unprimed mice challenged with OVA (Alum/OVA). (D) Lung sections were prepared 24 h after the last aerosol challenge and were stained with isotype matched control Ig (top) or anti-OX40 (bottom). A brown reaction product indicates OX40 staining. Similar results were seen in three experiments.

Few CD4 cells were present in the lungs of primed but unchallenged mice, and OX40 was not detected on either CD44hi or CD44lo cells (Fig. 1 B). However, after antigen challenge, a large number of OX40-expressing CD4/CD44hi cells were seen in the lung (Fig. 1 B, and see below). Analysis of lung sections revealed the presence of OX40+ cells in peribronchial and perivascular areas, sites previously shown to contain the majority of antigen-responding memory effector T cells (Fig. 1 D). These data show that OX40 is expressed on memory/memory effector T cells and suggest that it is available to play a role during the secondary response that occurs after reencounter with antigen.

Preventing OX40/OX40L Interaction Impairs Development of Airway Hyperreactivity and Eosinophilia.

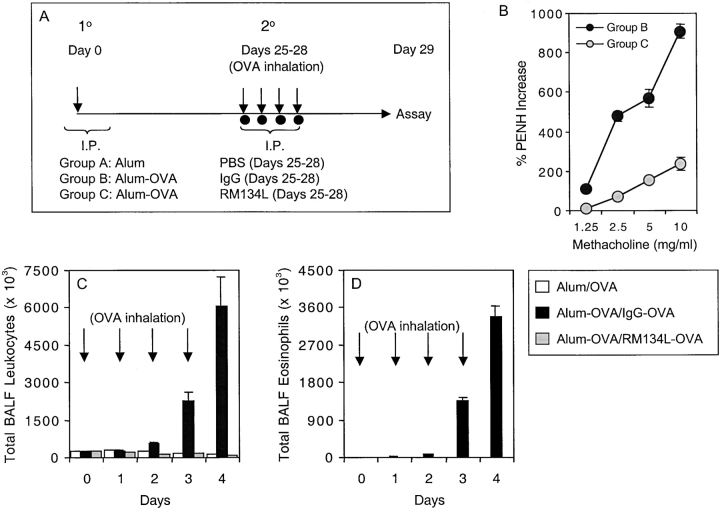

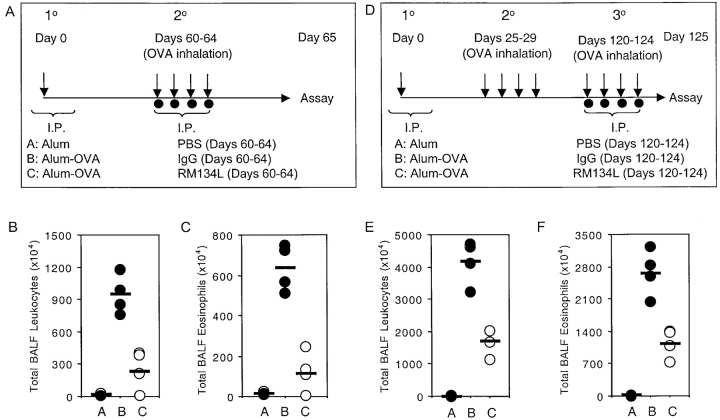

To examine the contribution of OX40/OX40L interactions to lung inflammation, we administered a blocking anti-OX40L mAb to OVA-sensitized mice at the time of rechallenge with aerosolized antigen (Fig. 2 A). OVA-immunized mice treated with the isotype control developed increases in AHR whereas administration of anti-OX40L dramatically reduced the degree of AHR (Fig. 2 B). Sensitized mice treated with control Ab during aerosol challenge (Alum-OVA/IgG-OVA) responded with an increase in the total number of cells in BAL (Fig. 2 C), which was evident as early as 48 h and was mostly eosinophils (Fig. 2 D). In striking contrast, administration of anti-OX40L during the challenge period (Alum-OVA/RM134L-OVA) virtually eliminated the increase in total leukocytes (Fig. 2 C) and eosinophils (Fig. 2 D). As no cell infiltration was seen in unprimed but challenged animals, this directly shows that OX40/OX40L interactions were essential to the recall response.

Figure 2.

Anti-OX40L suppresses memory T cell induced AHR and airway inflammation. (A) Experimental protocol for anti-OX40L administration. Unprimed control mice were injected i.p. with alum alone (Alum), while primed mice were sensitized with OVA adsorbed to alum (Alum-OVA). 25 d later, all mice were challenged with aerosolized OVA on 4 consecutive days (days 25–28; indicated by arrows). Either PBS (Group A: Alum/OVA), or control IgG (Group B: Alum-OVA/IgG-OVA) or anti-OX40L (Group C: Alum-OVA/RM134L-OVA) were administered i.p. on each challenge day. (B) 1–3 h after the last aerosol challenge, individual mice were assessed for AHR. Results are the mean percent change in Penh levels above baseline (saline-induced AHR), after exposure to increasing concentrations of inhaled methacholine. Values are calculated from four mice in each group per experiment. Similar results were seen in three experiments. (C) Total leukocyte numbers were enumerated in BAL at different times (0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 d) after exposure to aerosolized OVA (indicated by arrows). (D) Total numbers of eosinophils were calculated from differential stained BAL cytospins. Results are the mean number of cells ± SEM from two separate experiments with four mice per group in each experiment.

Blocking OX40/OX40L Interactions Inhibits the Development of Airway Tissue Eosinophilia, Goblet–Cell Hyperplasia, and Mucus Production.

To support the findings from lung lavages we conducted histological evaluations on lung sections. Mice receiving control Ab developed inflammatory lesions, characterized by a predominance of eosinophils and lymphocytes (Fig. 3, A and C) , together with hyperplasia of the mucus-secreting bronchial epithelial cells (Fig. 3 A). In contrast, lungs from anti-OX40L treated animals had almost normal bronchial epithelium, and a minimum of infiltrating cells around the bronchioles and blood vessels (Fig. 3, B and C). Many PAS+ (mucus-secreting) cells were detected in the airway of mice that were sensitized and challenged and received the control Ab (Fig. 3, D and F), whereas treatment with anti-OX40L markedly reduced the number of PAS+ cells (Fig. 3, E and F).

Figure 3.

Anti-OX40L inhibits lung infiltration, goblet cell hyperplasia, mucus, serum IgE, and BAL Th2 cytokine production. Groups of mice were immunized and challenged as described in Fig. 2. 24 h after the final OVA aerosol challenge, lung tissue was stained with H&E (×100) for quantitation of inflammatory infiltrates (A and B) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS, ×200; purple-red staining) to highlight the mucus-secreting cells (D and E), in sensitized and challenged animals receiving control Ig (A and D) or anti-OX40L (B and E). Sections were graded for inflammation severity (C) and mucus production (F) with groups A (white bars), B (black bars), and C (gray bars) corresponding to those described in Fig. 2. Results are the mean score ± SEM from four separate experiments with four mice per group in each experiment. 24 h after the final OVA aerosol challenge, sera were analyzed for OVA-specific IgE (G), and BAL were assessed for IL-4 (H), IL-5 (I), IL-9 (J), and IL-13 (K). Results are the mean values ± SEM from two separate experiments with four mice per group in each experiment.

Allergen-induced IgE and Th2 Cytokine Production Are Impaired in Anti-OX40L–treated Mice.

As an indirect test of whether OX40 signals were controlling the memory Th2 response driving the asthmatic reaction, we measured cytokine levels in the BAL and production of the Th2-associated antibody IgE in the serum. Treatment with anti-OX40L prevented the increase in IgE that resulted from the recall response (Fig. 3 G) and all Th2 cytokines (Fig. 3, H–K) associated with the secondary response. IFN-γ was either not present or at only low levels in all groups (unpublished data), suggesting that there was not a switch to a Th1 response.

OX40 Signals Control Memory Effector T Cell Accumulation in Secondary Lymphoid Organs.

To determine whether functional antigen-reactive T cells were present in mice where OX40 signals were blocked, OVA-specific proliferation and production of Th2 cytokines was measured in vitro. Strong responses were seen in lung cell cultures from OVA-primed and challenged mice but not in unprimed challenged mice (Fig. 4, A and B , compare grp B and grp A), again reflecting the memory effector response and that a functional primary response did not result from exposure to airborne antigen alone. Those animals treated with anti-OX40L during the recall response showed little or no OVA-specific T cell reactivity in the lungs (Fig. 4, A and B, grp C). To test whether recall responses were absent at other sites, spleen and lung draining lymph nodes were examined. Greatly reduced OVA-reactivity was found in secondary lymphoid organs after anti-OX40L treatment (Fig. 4, C and D). These results suggest that the effect of OX40/OX40L blockade is not tissue specific, but, rather, that OX40 signaling is critical for the development of functional memory effector cells after memory T cells reencounter antigen.

Figure 4.

OX40 signals control memory T cell responses in secondary lymphoid organs. Mice were immunized and challenged as in Fig. 2. (A–D) 1 d after the last OVA challenge, lung (A and B), and lymph node cells (C and D) were cultured in medium alone or in the presence of increasing doses of OVA (10, 50, 100 μg/ml). (A and C) Proliferation at 72 h with 10 μg/ml OVA. (B and D) IL-5 production (Group A: Alum/OVA; Group B: Alum-OVA/IgG-OVA; Group C: Alum-OVA/RM134L-OVA). Results are the mean ± SEM from quadruplicate cultures and are representative of three experiments. Similar results were obtained for IL-13. (E–G) Peribronchial lymph node (E), lung (F), and BAL (G) cells from unimmunized and challenged mice (⋄), or OVA-immunized and challenged mice treated with control Ab (•) vs. anti-OX40L Ab (O), were harvested before (day 0) or on the indicated days after the first OVA challenge. T cells were stained for CD4 and OX40. The total numbers of OX40+ CD4 T cells were calculated from four mice in each group after gating on viable CD4+ T cells. Similar results were seen in three experiments. (H and I) Total leukocyte (H) and eosinophil (I) numbers in BAL recovered from mice given anti-OX40L throughout the aerosol challenge (day 0), or 1, 2, or 3 d after the initial aerosol. Results are the mean ± SEM from one experiment with four mice per group.

As OX40 is only present on antigen-responding or antigen-experienced T cells, we tracked the accumulation of OX40-expressing CD4 cells over time. As shown in Fig. 4 (and Fig. 1), before antigen challenge, only a low number of T cells expressed OX40. After OVA challenge, an large increase was observed in the number of CD4+OX40+ cells in the bronchial LN (Fig. 4 E), lung (Fig. 4 F), and BAL (Fig. 4 G) in primed and challenged mice, far greater than in unprimed challenged mice, reflecting the population of responding memory effector T cells. The number of OX40+ cells in the LN peaked at day 1, whereas the number in the BAL rose progressively from day 2 over the 4-d aerosol exposure. This suggests that the initial memory T cell response developed in the secondary lymphoid organs, and within 24 h the T cells started to migrate to the lung. This correlates with other published data (31). Significantly, treatment of mice with anti-OX40L reduced the number of CD4+OX40+ cells visualized in the LN at the peak of response at day 1, and subsequently. Consequently, few activated OX40+ T cells were then observed in the lung and BAL. These results suggest that OX40/OX40L interactions are required early in the response of a memory T cell and control the ability to expand in numbers and survive in order to form a large population of memory effector T cells.

As further evidence for this, we performed kinetic blocking experiments where mice received anti-OX40L 1, 2, or 3 d after the initial aerosol (Fig. 4, H and I). Although delaying anti-OX40L treatment by 1 or 2 d reduced the response by 50% and 30%, the most dramatic effect was seen when OX40/OX40L interactions were inhibited at the time of initial encounter with recall antigen.

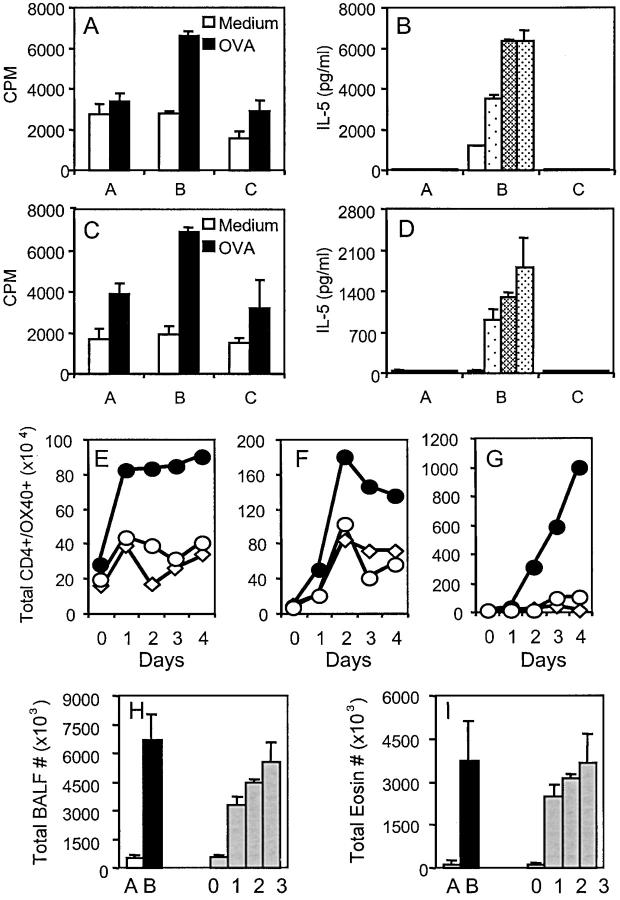

Primed OX40-deficient OVA-specific Th2 Cells Do Not Survive Efficiently in Recall Responses.

To further investigate the requirement for OX40 in recall responses of antigen-primed Th2 cells, OVA-specific OX40-deficient CD4 cells were produced by crossing OX40-knockout mice to OT-II TCR transgenic mice. Naive CD4 cells from wild-type (OX40+/+) or OX40-deficient (OX40−/−) OT-II mice were cultured in vitro with peptide and APCs under Th2 (IL-4, anti-IL-12, and anti-IFN-γ) polarizing conditions for a time period that allows primary T cell expansion and contraction to proceed normally. Previous data have shown that such in vitro–stimulated cells mimic in vivo generated memory cells (32, 33) and can also be used in adoptive transfer experiments to directly induce lung inflammation (34, 35).

Restimulation of primed OX40+/+ Th2 cells in vitro with OX40L-sufficient APCs resulted in proliferation, expansion, survival, and production of Th2 cytokines (Fig. 5) . Primed OX40−/− T cells secreted Th2 cytokines normally, suggesting that there is not a role for OX40 in this T cell activity, and OX40−/− T cells also initially proliferated comparably with wt T cells. However, far fewer T cells survived in the secondary response in the absence of OX40 signals, which was also reflected in weak proliferation late in culture (Fig. 5, A and B).

Figure 5.

Primed OX40−/− T cells do not survive efficiently in recall responses in vitro. OVA-specific Th2 memory cells were generated in vitro from wild-type (OX40+/+, closed symbols) or OX40-deficient (OX40−/−, open symbols) OT-II TCR transgenic mice as described in Materials and Methods. Primed T cells were restimulated with OVA peptide and APCs and proliferation (A) and survival (B) measured over 6 d. Cytokine production (C) was measured at 40 h. Data are means ± SEM from triplicate cultures, and representative of two separate experiments. Similar results were obtained if naive T cells were stimulated with antigen or anti-CD3 in primary cultures.

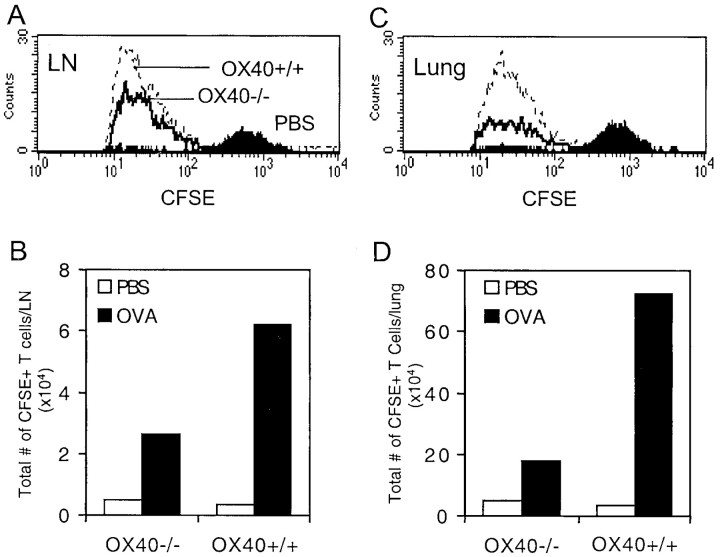

To determine if a similar requirement for OX40 was apparent in vivo during a recall response to aerosolized antigen, in vitro–primed T cells were labeled with CFSE, adoptively transferred into naive recipients, and then these mice were challenged intranasally with OVA (Fig. 6) . Challenge with PBS did not result in division (Fig. 6, A and C) or expansion (Fig. 6, B and D) of either OX40+/+ or OX40−/− T cells in draining lymph nodes or lung. Challenge with OVA resulted in pronounced division of all OX40+/+ T cells and accumulation in numbers was observed in lymph nodes and particularly evident in the lung. Correlating with the in vitro data, recovered OX40−/− T cells displayed the same division profile as their wt counterparts (Fig. 6, A and C), but in total approximately fourfold fewer accumulated at the end of the antigen challenge period (Fig. 6, B and D). This directly mimicked the data obtained by tracking OX40-expressing T cells after OX40L blockade (Fig. 4, E–G). This shows that OX40 signals regulate the number of memory effector T cells that are generated after memory T cells reencounter antigen.

Figure 6.

Primed OX40−/− T cells do not accumulate efficiently in recall responses in vivo. OVA-specific Th2 memory cells were generated in vitro as in Fig. 5, from wild-type (OX40+/+) or OX40-deficient (OX40−/−) OT-II TCR transgenic mice. Primed T cells were labeled with CFSE and injected i.v. into naive C57BL/6 mice. Recipient mice were subsequently exposed to inhaled OVA or PBS on two consecutive days. 1 d after the last OVA challenge, peribronchial lymph node (A and B) and lung (C and D) were analyzed by flow cytometry for division (A and C) and accumulation (B and D) of transferred CFSE/Vα2 positive CD4 T cells. Data are representative of two separate experiments.

Primed OX40-deficient OVA-specific Th2 Cells Do Not Efficiently Promote Lung Inflammation.

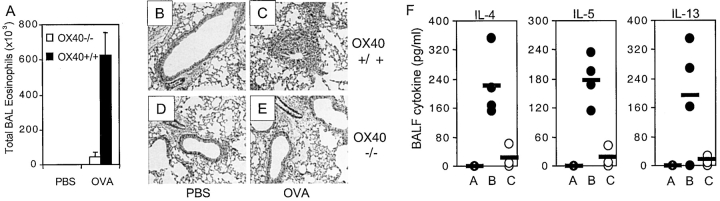

To correlate a lack of expansion/survival of memory effector cells with reduced lung inflammation, eosinophilia, lung histology, and Th2 cytokines were analyzed after adoptive transfer of primed OX40−/− OT-II Th2 cells (Fig. 7) . Transfer of wild-type cells followed by repeated intranasal OVA challenge induced profound inflammation accompanied by production of Th2 cytokines in BAL (Fig. 7, A, C, and F). In contrast, mice receiving OX40-deficient cells showed only a small increase in the total numbers of eosinophils recovered from the BAL (Fig. 7 A), relatively normal lung histology (compare Fig. 7 E to 7 C), and reduced Th2 cytokines (Fig. 7 F). These results clearly show that OX40 expressed on a memory Th2 cell is required for lung inflammation.

Figure 7.

Primed OX40-deficient T cells cannot induce pronounced airway inflammation. OVA-specific Th2 memory cells were generated in vitro as in Fig. 5, from wild-type (OX40+/+) or OX40-deficient (OX40−/−) OT-II TCR transgenic mice. Primed T cells were injected i.v. into naive C57BL/6 mice. Recipient mice were subsequently exposed to aerosolized OVA or PBS on two consecutive days. (A) Eosinophil numbers in BAL 24 h after the last OVA challenge. Results are mean ± SEM from four mice per group. (B–E) H&E stained lungs from mice receiving wild-type (B and C) or OX40-deficient T cells (D and E) after challenge with PBS (B and D) or OVA (C and E). (F) IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 levels in BAL from mice with wt T cells challenged with PBS (Grp A), wt T cells challenged with OVA (Grp B), OX40−/− T cells challenged with OVA (Grp C). Similar results were seen in three separate experiments.

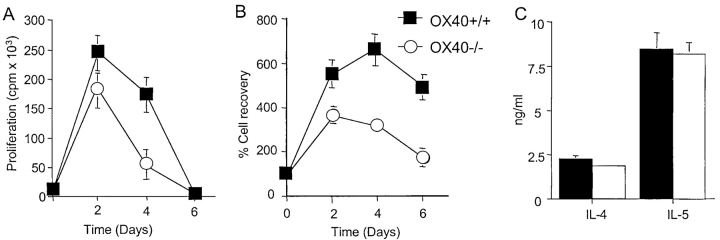

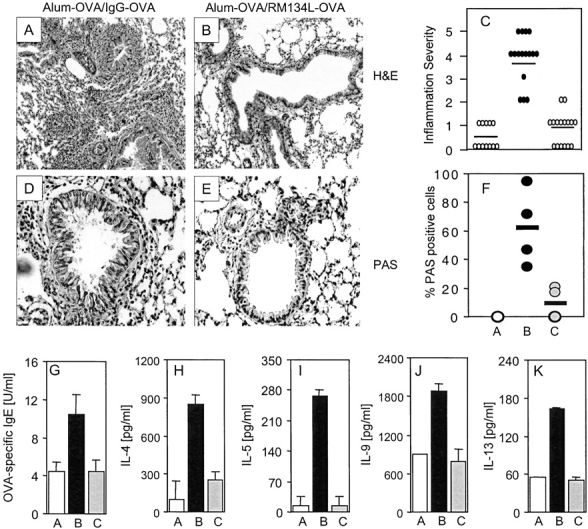

OX40/OX40L Interactions Control both Late Secondary and Tertiary Recall Responses to Inhaled Antigen.

As our initial studies addressed the role of OX40 signals in the recall response of what can been termed early memory T cells, persisting 4 wk after primary immunization, we determined whether OX40/OX40L interactions were also critical to the response of memory T cells that persist for longer periods of time and survive following a secondary response. In one set of experiments, mice were primed for 8 wk and anti-OX40L administered during the secondary response to aerosolized antigen (Fig. 8 A). Again, blocking OX40 signals strongly inhibited all aspects of lung inflammation, including total leukocyte (Fig. 8 B) and eosinophil (Fig. 8 C) infiltration, and production of Th2 cytokines (unpublished data). In further experiments, mice were primed for 4 wk, challenged with aerosolized antigen in a secondary response without blocking OX40L, rested for 13 wk, and then challenged again but with anti-OX40L blockade (Fig. 8 D). Inhibiting OX40 signals during this tertiary response again strongly inhibited lung inflammation (Fig. 8, E and F), with a greater than 50% reduction in cellular infiltration. As no lung inflammation was observed in unsensitized control mice that were repeatedly exposed to aerosolized antigen, ruling out any primary response (Fig. 8, E and F, grp A), these data demonstrate that blocking OX40/OX40L interactions severely limits the recall response of memory Th2 populations that can persist for extended periods of time.

Figure 8.

OX40/OX40L interactions control both late secondary and tertiary recall responses to inhaled antigen. (A) Immunization protocol for secondary response of late memory T cells. Unprimed control mice were injected i.p. with alum alone (Alum), while primed mice were sensitized with OVA adsorbed to alum (Alum-OVA). 60 d later, all mice were challenged with aerosolized OVA on 4 consecutive days (days 60–64; indicated by arrows). Either PBS (Group A: Alum/OVA), or control IgG (Group B: Alum-OVA/IgG-OVA) or anti-OX40L (Group C: Alum-OVA/RM134L-OVA) were administered i.p. on each challenge day (indicated by filled symbols). (D) Immunization protocol for tertiary response of late memory T cells. Unprimed control mice were injected i.p. with alum alone (Alum), while primed mice were sensitized with OVA adsorbed to alum (Alum-OVA). On days 25–29 all mice were challenged in a secondary response with aerosolized OVA. 91 d later (day 120), all mice were challenged in a tertiary response with aerosolized OVA on 4 consecutive days (days 120–124; indicated by arrows). Either PBS (Group A: Alum/OVA), or control IgG (Group B: Alum-OVA/IgG-OVA) or anti-OX40L (Group C: Alum-OVA/RM134L-OVA) were administered i.p. on each challenge day (indicated by filled symbols). 1 d after the last challenge mice were killed and airway eosinophilia and Th2 cytokine production determined. Total leukocyte (B and E) and eosinophil (C and F) numbers were enumerated in BAL from mice in protocol A (B and C) and protocol D (E and F) respectively. Analysis of Th2 cytokines showed the same profile as cell infiltration (unpublished data). Individual responses of four mice in each group are shown.

Discussion

Previous work has demonstrated that OX40 and OX40L control the development of a number of primary T cell responses (9–11, 18–27) but no data has been presented regarding a role for these interactions in the recall response of memory T cells. We now show the absolute importance of OX40–OX40L interactions in antigen-specific memory that mediates allergic lung inflammation. We demonstrate that exposure of sensitized animals to antigen via the airways is accompanied by large increases in the number of OX40-expressing memory/memory effector Th2 cells, both in the lungs and in secondary lymphoid organs, which was closely associated with eosinophilia and the development of airway hyperresponsiveness. Strikingly, preventing OX40–OX40L interactions during the recall response inhibited the ensuing Th2 response and the associated asthmatic symptoms. These results provide the first in vivo evidence that memory T cells, like naive T cells, can require costimulation through OX40, and indicate that OX40–OX40L interactions are potential targets for modulating peripheral acute phase inflammatory responses.

Our recent data show that OX40 principally functions by suppressing T cell death and does so by maintaining high levels of antiapoptotic proteins such as Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 (11) and inhibiting expression or activity of proapoptotic proteins such as Bad and Bim (unpublished data). This conclusion has been reinforced by in vivo studies where agonist antibodies directed to OX40 on a responding naive CD4 cell enhanced primary T cell expansion and survival, and in so doing promoted the development of greater numbers of memory T cells (10, 36). The data here now complement these studies and show that OX40 can act in the response of a memory Th2 cell in an analogous manner and dictate the expansion and persistence of antigen-specific memory effector T cells during recall lung inflammation.

Analysis of BAL and dispersed lung showed that anti-OX40L reduced the absolute numbers of activated (OX40+) memory effector T cells, potentially consistent with the idea that OX40 could be involved in memory T cell recruitment. However, low numbers of activated OX40+ T cells were also observed in secondary lymphoid organs, along with reduced antigen-specific activity, supporting the notion that preventing OX40/OX40L interactions did not simply block T cells from entering the lung. Other studies of lung inflammation have suggested that memory T cells do not proliferate in the lung in response to intranasal antigen challenge, but proliferate in the lymph nodes (37). Moreover, prior reports show that T cell emergence in the lung is only appreciable 24–48 h after antigen reexposure (31), consistent with the idea that expansion and survival signals are required to generate a large pathogenic population. Our kinetic blocking data showing maximal inhibition only when OX40/OX40L interactions are absent at the time of initial antigen challenge support this, along with the idea that OX40 signals are required early (0–48 h) and most likely provided in the secondary lymphoid organs. Further in line with the idea that OX40 signals dictate the subsequent generation or survival of memory effector T cells after antigen reactivation, primed OX40-deficient Th2 cells were found capable of proliferating initially in the recall response, but did not subsequently accumulate in high numbers.

Previous studies of memory T cells have largely concluded that they had a reduced requirement for costimulatory signals and hence may not be susceptible to interventions that target such membrane bound molecules (38). For example, blocking B7–CD28 interactions during secondary responses to the nematode parasites Heligmosomoides polygyrus (7) and Nippostrongylus brasiliensis (8), or immunogenic anti-mouse IgD antibody treatment (6), failed to inhibit memory Th2 responses, whereas blocking CD28 at the time of priming was suppressive (6–8). These and other observations therefore implied that activation of memory Th2 cells may be costimulation, or at least B7/CD28, independent. However, in light of our data on OX40, rather than becoming costimulation independent, T cells may shift after antigen exposure to being more reliant on other molecules. Recent studies from Gonzalo et al. (39) on an inducible Ig family member, ICOS, also support this idea. These latter data in another variant of the asthma model showed that blocking B7RP-1–ICOS interactions effectively inhibited most asthmatic symptoms at the time of allergen exposure, producing an overall result similar to our data with OX40. Furthermore, this report showed that ICOS was active at a time when CD28 was not a major factor. Unlike OX40, it has been proposed that ICOS may primarily regulate cytokine production (40) rather than T cell survival, and therefore it is an intriguing idea that both of these molecules act in concert but dictate distinct phases during the Th2 recall response.

In summary, our experiments show a critical role for OX40/OX40L interactions in the recall response to inhaled antigen, for the subsequent activation and recruitment of memory effector CD4 T cells into the airway, and for the induction of morphological changes to the airways that are reminiscent of human asthma. As CD4+ T cells have been shown to play a critical role in both initiation and maintenance of allergic pulmonary responses, our results have important ramifications for the development of therapeutic strategies in which anti-OX40L antibodies, alone or in combination with other therapies, can be used in clinical situations where memory Th2 cells have been implicated. Importantly, this approach has a distinct advantage of blocking the production of several Th2 cytokines simultaneously rather than suppressing the activity of a single cytokine, and may profoundly affect the ability to continue to mount a Th2 response.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an award from the Sandler Program for Asthma Research, and National Institutes of Health grant AI50498, to M. Croft. This is publication # 515 from the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: AHR, airway hyperreactivity; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; PBLN, peribronchial LN.

References

- 1.Wills-Karp, M. 1999. Immunologic basis of antigen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17:255–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Umetsu, D.T., J.J. McIntire, O. Akbari, C. Macaubas, and R.H. DeKruyff. 2002. Asthma: an apidemic of dysregulated immunity. Nat. Immunol. 3:715–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Croft, M., L.M. Bradley, and S.L. Swain. 1994. Naive versus memory CD4 T cell response to antigen. Memory cells are less dependent on accessory cell costimulation and can respond to many antigen-presenting cell types including resting B cells. J. Immunol. 152:2675–2685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byrne, J.A., J.L. Butler, and M.D. Cooper. 1988. Differential activation requirements for virgin and memory T cells. J. Immunol. 141:3249–3257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luqman, M., and K. Bottomly. Activation requirements for CD4+ T cells differing in CD45R expression. J. Immunol. 149:2300–2306. [PubMed]

- 6.Lu, P., X.D. Zhou, S.J. Chen, M. Moorman, A. Schoneveld, S. Morris, F.D. Finkelman, P. Linsley, E. Claasen, and W.C. Gause. 1995. Requirement of CTLA-4 counter receptors for IL-4 but not IL-10 elevations during a primary systemic in vivo immune response. J. Immunol. 154:1078–1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gause, W.C., P. Lu, X.D. Zhou, S.J. Chen, K.B. Madden, S.C. Morris, P.S. Linsley, F.D. Finkelman, and J.F. Urban. 1996. H. polygyrus: B7-independence of the secondary type 2 response. Exp. Parasitol. 84:264–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris, N.L., R.J. Peach, and F. Ronchese. 1999. CTLA4-Ig inhibits optimal T helper 2 cell development but not protective immunity or memory response to Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gramaglia, I., A.D. Weinberg, M. Lemon, and M. Croft. 1998. OX40 ligand: a potent costimulatory molecule for sustaining primary CD4 T cell responses. J. Immunol. 161:6510–6517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gramaglia, I., A. Jember, S.D. Pippig, A.D. Weinberg, N. Killeen, and M. Croft. 2000. The OX40 costimulatory receptor determines the development of CD4 memory by regulating primary clonal expansion. J. Immunol. 165:3043–3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers, P.R., J. Song, I. Gramaglia, N. Killeen, and M. Croft. 2001. OX40 promotes Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 expression and is essential for long-term survival of CD4 T cells. Immunity. 15:445–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mallett, S., S. Fossum, and A.N. Barclay. 1990. Characterization of the MRC OX40 antigen of activated CD4 positive T lymphocytes–a molecule related to nerve growth factor receptor. EMBO J. 9:1063–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calderhead, D.M., J.E. Buhlmann, A.J. van den Eertwegh, E. Claassen, R.J. Noelle, and H.P. Fell. 1993. Cloning of mouse Ox40: a T cell activation marker that may mediate T–B cell interactions. J. Immunol. 151:5261–5271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baum, P.R., R.B. Gayle, F. Ramsdell, S. Srinivasan, R.A. Sorensen, M.L. Watson, M.F. Seldin, E. Baker, G.R. Sutherland, K.N. Clifford, et al. 1994. Molecular characterization of murine and human OX40/OX40 ligand systems: identification of a human OX40 ligand as the HTLV-1-regulated protein gp34. EMBO J. 13:3992–4001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Shamkhani, A., S. Mallett, M.H. Brown, W. James, and A.N. Barclay. 1997. Affinity and kinetics of the interaction between soluble trimeric OX40 ligand, a member of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily, and its receptor OX40 on activated T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 272:5275–5282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stuber, E., M. Neurath, D. Calderhead, H.P. Fell, and W. Strober. 1995. Cross-linking of OX40 ligand, a member of the TNF/NGF cytokine family, induces proliferation and differentiation in murine splenic B cells. Immunity. 2:507–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohshima, Y., Y. Tanaka, H. Tozawa, Y. Takahashi, C. Maliszewski, and G. Delespesse. 1997. Expression and function of OX40 ligand on human dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 159:3838–3848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinberg, A.D., K.W. Wegmann, C. Funatake, and R.H. Whitham. 1999. Blocking OX-40/OX-40 ligand interaction in vitro and in vivo leads to decreased T cell function and amelioration of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 162:1818–1826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kopf, M., C. Ruedl, N. Schmitz, A. Gallimore, K. Lefrang, B. Ecabert, B. Odermatt, and M.F. Bachmann. 1999. OX40-deficient mice are defective in Th cell proliferation but are competent in generating B cell and CTL Responses after virus infection. Immunity. 11:699–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen, A.I., A.J. McAdam, J.E. Buhlmann, S. Scott, M.L. Lupher, E.A. Greenfield, P.R. Baum, W.C. Fanslow, D.M. Calderhead, G.J. Freeman, and A.H. Sharpe. 1999. Ox40-ligand has a critical costimulatory role in dendritic cell:T cell interactions. Immunity. 11:689–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murata, K., N. Ishii, H. Takano, S. Miura, L.C. Ndhlovu, M. Nose, T. Noda, and K. Sugamura. 2000. Impairment of antigen-presenting cell function in mice lacking expression of OX40 ligand. J. Exp. Med. 191:365–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jember, A.G., R. Zuberi, F.T. Liu, and M. Croft. 2001. Development of allergic inflammation in a murine model of asthma is dependent on the costimulatory receptor OX40. J. Exp. Med. 193:387–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akiba, H., Y. Miyahira, M. Atsuta, K. Takeda, C. Nohara, T. Futagawa, H. Matsuda, T. Aoki, H. Yagita, and K. Okumura. 2000. Critical contribution of OX40 ligand to T helper cell type 2 differentiation in experimental leishmaniasis. J. Exp. Med. 191:375–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsukada, N., H. Akiba, T. Kobata, Y. Aizawa, H. Yagita, and K. Okumura. 2000. Blockade of CD134 (OX40)-CD134L interaction ameliorates lethal acute graft-versus-host disease in a murine model of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 95:2434–2439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins, L.M., S.A. McDonald, N. Whittle, N. Crockett, J.G. Shields, and T.T. MacDonald. 1999. Regulation of T cell activation in vitro and in vivo by targeting the OX40-OX40 ligand interaction: amelioration of ongoing inflammatory bowel disease with an OX40-IgG fusion protein, but not with an OX40 ligand-IgG fusion protein. J. Immunol. 162:486–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshioka, T., A. Nakajima, H. Akiba, T. Ishiwata, G. Asano, S. Yoshino, H. Yagita, and K. Okumura. 2000. Contribution of OX40/OX40 ligand interaction to the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:2815–2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nohara, C., H. Akiba, A. Nakajima, A. Inoue, C.S. Koh, H. Ohshima, H. Yagita, Y. Mizuno, and K. Okumura. 2001. Amelioration of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with anti-OX40 ligand monoclonal antibody: a critical role for OX40 ligand in migration, but not development, of pathogenic T cells. J. Immunol. 166:2108–2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bansal-Pakala, P., A.G. Jember, and M. Croft. 2001. Signaling through OX40 (CD134) breaks peripheral T-cell tolerance. Nat. Med. 7:907–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnden, M.J., J. Allison, W.R. Heath, and F.R. Carbone. 1998. Defective TCR expression in transgenic mice constructed using cDNA-based alpha- and beta-chain genes under the control of heterologous regulatory elements. Immunol. Cell Biol. 76:34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akiba, H., H. Oshima, K. Takeda, M. Atsuta, H. Nakano, A. Nakajima, C. Nohara, H. Yagita, and K. Okumura. 1999. CD28-independent costimulation of T cells by OX40 ligand and CD70 on activated B cells. J. Immunol. 162:7058–7066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaminuma, O., H. Fujimura, K. Fushimi, A. Nakata, A. Sakai, S. Chishima, K. Ogawa, M. Kikuchi, H. Kikkawa, K. Akiyama, and A. Mori. 2001. Dynamics of antigen-specific helper T cells at the initiation of airway eosinophilic inflammation. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:2669–2679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu, H., G. Huston, D. Duso, N. Lepak, E. Roman, and S.L. Swain. 2001. CD4(+) T cell effectors can become memory cells with high efficiency and without further division. Nat. Immunol. 2:705–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harbertson, J., E. Biederman, K.E. Bennet, R.M. Kondrack, and L.M. Bradley. 2002. Withdrawal of stimulation may initiate the transition of effector to memory CD4 cells. J. Immunol. 168:1095–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohn, L., R.J. Homer, A. Marinov, J. Rankin, and K. Bottomly. 1997. Induction of airway mucus production By T helper 2 (Th2) cells: a critical role for interleukin 4 in cell recruitment but not mucus production. J. Exp. Med. 186:1737–1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hansen, G., G. Berry, R.H. DeKruyff, and D.T. Umetsu. 1999. Allergen-specific Th1 cells fail to counterbalance Th2 cell-induced airway hyperreactivity but cause severe airway inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 103:175–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maxwell, J.R., A. Weinberg, R.A. Prell, and A.T. Vella. 2000. Danger and OX40 receptor signaling synergize to enhance memory T cell survival by inhibiting peripheral deletion. J. Immunol. 164:107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harris, N.L., V. Watt, F. Ronchese, and G. Le Gros. 2002. Differential T cell function and fate in lymph node and nonlymphoid tissues. J. Exp. Med. 195:317–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Croft, M. Activation of naive, memory and effector T cells. 1994. Curr Opin. Immunol. 6:431–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonzalo, J.A. J. Tian, T. Delaney, J. Corcoran, J.B. Rottman, J. Lora, A. Al-garawi, R. Kroczek, J.C. Gutierrez-Ramos, and A.J. Coyle. 2001. ICOS is critical for T helper cell-mediated lung mucosal inflammatory responses. Nat. Immunol. 2:597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coyle, A.J., S. Lehar, C. Lloyd, J. Tian, T. Delaney, S. Manning, T. Nguyen, T. Burwell, H. Schneider, J.A. Gonzalo, et al. 2000. The CD28-related molecule ICOS is required for effective T cell-dependent immune responses. Immunity. 13:95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]