Abstract

Transcription antitermination in the rRNA operons of Escherichia coli requires a unique nucleic acid sequence that serves as a signal for modification of the elongating RNA polymerase, making it resistant to Rho-dependent termination. We examined the antitermination ability of RNA polymerase elongation complexes that had initiated at three different heat shock promoters, dnaK, groE, and clpB, and then transcribed the antitermination sequence to read through a Rho-dependent terminator. Terminator bypass comparable to that seen with σ70 promoters was obtained. Lack of or inversion of the sequence abolished terminator readthrough. We conclude that RNA polymerase that uses σ32 to initiate transcription can adopt a conformation similar to that of σ70-containing RNA polymerase, enabling it to interact with auxiliary modifying proteins and bypass Rho-dependent terminators.

Regulatory studies of gene expression have traditionally concentrated on transcription initiation, but the processes of elongation, termination, and antitermination have become increasingly important aspects of gene regulation to address (2, 3, 15, 17). In particular, transcription antitermination (modification of the transcription apparatus so that terminators can be bypassed) presents an interesting regulatory mechanism. Transcription and translation are coupled for most operons of Escherichia coli. However, when translation is arrested or untranslated regions of RNA are synthesized early termination of transcription often results, causing a dramatic decrease in downstream gene expression, a phenomenon known as polarity (17). Untranslated regions of RNA frequently permit access by the transcription termination protein, Rho, leading to premature termination of transcription and release of RNA polymerase from the transcript (for a review, see reference 17). The transcripts of rRNA operons are not translated and contain Rho-dependent termination sites but are not subject to polarity (1, 5, 14). The absence of polarity and the synthesis of stoichiometric amounts of all three rRNA subunits are accounted for by a specific type of transcription antitermination (4, 10).

Rho-dependent terminator suppression in the rRNA operons is mediated by special antiterminator sequences that occur once in the leader region and again in the spacer region between the 16S and 23S genes (4, 8, 10, 18). These sequences can effectively suppress a variety of Rho-dependent terminators both in vivo and in vitro (10, 20). An important part of the rRNA antiterminator is the sequence GCTCTTTAACAA, called boxA (4). Host proteins NusA, NusB, NusE (ribosomal protein S10), and NusG are thought to be involved, and additional cellular proteins such as ribosomal protein S4 are also required for efficient terminator readthrough (20, 22). Several of these host factors interact directly with RNA polymerase, rendering it resistant to Rho-dependent termination (11-13, 22). Exactly how they accomplish this task is not known.

A further unanswered question is whether the nature of the σ subunit associated with RNA polymerase affects antitermination. For example, if a particular σ factor did not cycle off after initiation, RNA polymerase might not be able to recruit other factors necessary for the alteration of its transcription properties. When cells are subjected to stresses such as rapid heat or osmotic changes, selective groups of proteins are rapidly and transiently induced to protect the cell or help it adapt to the new environment. The heat shock response results when RNA polymerase associates with an alternative σ factor, σ32, which directs core RNA polymerase to distinct promoters (7, 23). The consensus sequences of heat shock gene promoters differ considerably from those of σ70-dependent promoters. There is no evidence that these promoters undergo cross-recognition (a mechanism which provides heat shock genes with regulation distinct from that of most of cellular proteins) (7, 25) either in vivo and in vitro. In the present study, we tested whether the antitermination properties of RNA polymerase are altered as a result of initiation at heat shock promoters. It is particularly interesting that all rRNA operon P1 promoters have interdigitated heat shock promoters. Both the σ70-dependent and σ32-dependent promoters initiated RNA transcription at the same nucleotide (16).

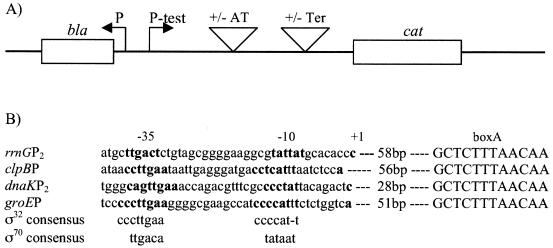

To measure the terminator readthrough properties of RNA polymerase molecules initiated at these promoters, we used gene fusion plasmids to construct an antitermination assay system (Fig. 1A). Each promoter sequence and its position relative to the boxA feature of the antiterminator sequence are shown in Fig. 1B, and their relevant structures with respect to promoters, antiterminators, and terminators are listed in Table 1. Plasmid pSL100 was used as the parental plasmid for all constructs. Its structure and those of pSL102 and pSL103 (containing rrnGP2 [the σ70 promoter]) have been detailed by Li et al. (10). A fragment containing the groEP heat shock promoter was obtained from plasmid pDC440 (7) by digestion with TaqI and HpaI. The isolated fragment was ligated into pSL102 and pSL103 digested with ClaI to yield pSGE102 and pSGE103, respectively. The heat shock promoter from the clpB gene was amplified from plasmid pClpB (21) by PCR with a 5′ BglII site and a 3′ ClaI site and used to replace the rrnGP2 fragment of pSL102 and pSL103, resulting in pSCB102 and pSCB103, respectively. The heat shock promoter from the dnaK gene was cloned from pDC403 (7).

FIG. 1.

Gene fusion plasmid antitermination assay system and sequences of test promoters. (A) A reporter gene, CM acetyltransferase (cat), was placed down stream of a Rho-dependent terminator, Ter. Open boxes represent the cat gene and the bla gene (encoding β-lactamase). Large inverted triangles show the insertion points for the antiterminator (AT) and a Rho-dependent terminator (Ter) sequences. P-test, insertion point of the test promoter transcribing the cat gene. Terminator readthrough was determined by analysis of the level of the cat gene mRNA transcript normalized to the level of bla gene transcript. (B) Sequences of the rrnGP2 and heat shock promoters clpBP, dnaKP2, and groEP and their relative distances to the rrnG boxA antiterminator. Promoter recognition sites and the start of transcription are indicated by −35, −10, and +1 (sequences in boldface characters). Numbers (in base pairs) indicate the distances between the start of transcription and the boxA sequence in nucleotides.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid designation | Elements in multicloning site

|

Reference or source | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Promoter | Antiterminator | Terminator | ||

| pSL102 | rrnGP2 | Li et al. (10) | ||

| pSL103 | rrnGP2 | 16S← | Li et al. (10) | |

| pSLW114 | rrnGP2 | AT | This work | |

| pSLW115 | rrnGP2 | AT | 16S← | This work |

| pSLW126 | rrnGP2 | ATInv | This work | |

| pSLW127 | rrnGP2 | ATInv | 16S← | This work |

| pSGE102 | groEP | This work | ||

| pSGE103 | groEP | 16S← | This work | |

| pSGE114 | groEP | AT | This work | |

| pSGE115 | groEP | AT | 16S← | This work |

| pSGE126 | groEP | ATInv | This work | |

| pSGE127 | groEP | ATInv | 16S← | This work |

| pSCB102 | clpBP | This work | ||

| pSCB103 | clpBP | 16S← | This work | |

| pSCB114 | clpBP | AT | This work | |

| pSCB115 | clpBP | AT | 16S← | This work |

| pSCB126 | clpBP | ATInv | This work | |

| pSCB127 | clpBP | ATInv | 16S← | This work |

| pSDK102 | dnaKP2 | This work | ||

| pSDK103 | dnaKP2 | 16S← | This work | |

| pSDK114 | dnaKP2 | AT | This work | |

| pSDK115 | dnaKP2 | AT | 16S← | This work |

A promoter containing HpaII and HinPI fragments was inserted into the ClaI sites of pSL100 and pSL101 (10) to yield pSDK102 and pSDK103, respectively. rrn antitermination sequences were obtained (using 5′ and 3′ BamHI primers) from the pRATT1 plasmid (20). The amplified fragment was digested with BamHI and purified. This antiterminator-containing fragment was then ligated into previously constructed plasmids (except pSDK102 and pSDK103) digested with BamHI. The antiterminator sequence was inserted in either the correct or an inverse orientation. The source of antitermination rrnG leader sequences for pSDK114 and pSDK115 was pSL104 (10), which was cleaved with BglII and TaqI and inserted into pSL102 and pSL103 (10). The Rho-dependent terminator sequence (16S←) used was a HindIII 16S fragment from the rrnB operon inserted into pSL100 in the backwards orientation to yield pSL103. In this orientation, the fragment fortuitously contains a strong Rho-dependent terminator (10).

The sequences of promoters and the orientation of the antiterminator sequence were verified by DNA sequencing using a Perkin-Elmer Prism sequencer (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, Mass). E. coli strain MC1009 [Δ(lacIPOZY) galU galK Δ(ara-leu) rpsL srl::Tn10 recA spoT relA] (20) was the host strain for all plasmids used in this study. Strains harboring test plasmids were used to inoculate 6 ml of Luria broth supplemented with 1% glucose and 100 μg of ampicillin/ml from overnight cultures in the same medium and incubated with shaking at 37°C. When the culture density reached an optical density at 600 nm of 1.0, cells were harvested by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge. The cell pellets were then frozen in a dry ice-ethanol bath and kept at −80°C. RNA isolation was done using an RNeasy RNA isolation kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer's protocol. The concentration of total RNA was measured using absorbance at 260 nm and kept at −80°C until further analysis was performed. Two end-labeled oligonucleotide probes were used to quantitate mRNA levels: (i) a chloramphenicol (CM) acetyltransferase (cat) probe (5′-TGCCATTGGGATATATCAACGGTGG-3′) (located at nucleotides 26 to 50 of the cat gene encoding sequence and used to measure cat gene expression) and (ii) β-lactamase (bla) probe (5′-GGGAATAAGGCGACACGGAAATG-3′) (located at nucleotides 13 to 36 of the bla gene encoding sequence and used to quantitate the level of bla gene expression). This measurement serves as an internal control to correct for variations in sample preparation and plasmid copy number (9). Slot blot analyses were carried out in triplicate for each sample of 5 μg of denatured total RNA by the method described by Zellars and Squires (24).

The rRNA antiterminator sequence can promote terminator readthrough by RNA polymerase initiated from heat shock promoters.

Previous studies showed that the E. coli rRNA leader region antiterminator sequence is able to promote transcription readthrough of Rho-dependent terminators when transcription is initiated from unrelated σ70 promoters such as rrnGP2, Ptac, and Plac (10). Similarly, the lambda nutR antitermination sequence is functional with galactose operon promoters (8). Alternative σ factors, such as those used in responding to heat shock or stationary-phase conditions, differ dramatically in size from σ70 and have widely differing DNA sequence recognition properties (7). It is thus possible that the overall architecture and properties of RNA polymerase initiated at such promoters differ substantially from RNA polymerase molecules that initiate with σ70. If the elongating polymerase configuration were changed or the alternative σ factor were not to cycle off the polymerase, such differences could lead to alterations in response to, or interaction with, other cellular factors during transcription. We tested the well-defined dnaK, groE, and clpB heat shock promoters (7, 21) to see whether RNA polymerase that initiates at σ32 promoters can recognize the rRNA antiterminator.

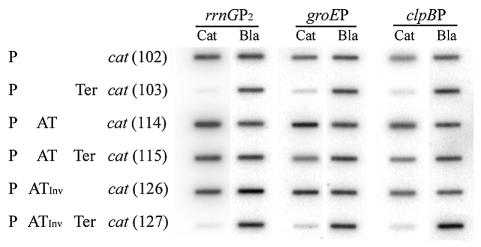

Preliminary experiments revealed that CM resistance levels of the strains carrying the assay plasmids were increased in the presence of the antiterminator. Quantitative slot blot analyses were then carried out to measure terminator readthrough activity in conjunction with the different promoters and the antiterminator sequence. The measured cat mRNA levels were normalized to the bla (β-lactamase gene) mRNA (also carried on the plasmid) to compensate for any difference in plasmid copy numbers and total RNA amounts recovered (9). The results showed that when the rRNA antiterminator sequence was placed between the promoter and the Rho-dependent terminator, terminator readthrough was observed with all promoters tested (Fig. 2 and Table 2). The presence of the antiterminator sequence resulted in 61, 42, 29, and 58% terminator readthrough (P+AT+T mRNA level; Table 2) compared to that seen with constructs without the terminator (P+AT) for the rrnG, groE, clpB, and dnaK promoters, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Slot blot analysis of cat and bla mRNA levels. The specific transcripts were measured from total RNA extracted from cells harboring the indicated plasmids. Slot blot membranes hybridized with radiolabeled cat and bla probes were exposed on a Phosphorimager and scanned with a Storm Scanner (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Inc., Piscataway, N.J.) for quantitation. P, promoter; Ter, Rho-dependent terminator; AT, rrnG antiterminator sequence; ATInv, rrnG antiterminator sequence in reverse orientation; cat, gene encoding CM acetyltransferase. Numbers in parentheses indicate designated plasmid numbers (Table 1).

TABLE 2.

Terminator readthrough analysis of σ32 promoters

|

cat/bla ratioa

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Promoter (P) | Termination (P+T) | AT effect (P+AT) | AT RT (P+AT+T) | ATInv effect (P+ATInv) | ATInv RT (P+ATInv+T) | |

| rrnGP2 | ||||||

| mRNA | 100 | 1 | 209 | 127 (61) | 118 | 1 (1) |

| CMr | 100 | 3 | 100 | 67 (67) | 100 | 3 (3) |

| groEP | ||||||

| mRNA | 100 | 4 | 307 | 129 (42) | 191 | 2 (1) |

| CMr | 100 | 12 | 200 | 80 (40) | 394 | 12 (3) |

| clpBP | ||||||

| mRNA | 100 | 4 | 146 | 42 (29) | 121 | 4 (3) |

| CMr | 100 | 10 | 100 | 40 (40) | 140 | 0 (0) |

| dnaKP2 | ||||||

| mRNA | 100 | 6 | 173 | 100 (58) | NDb | ND |

Levels of cat expression are shown as ratios of percentages relative to each of the promoter-only (P) constructs. The numbers in parentheses indicate AT or ATInv sequence terminator readthrough activities (in percentages) relative to an AT effect (P+AT) or to an ATInv effect (P+ATInv), respectively. The mRNA transcript data were obtained from scanned slot blot analysis (Fig. 2). CMr data were obtained by plating cells harboring test plasmids on Luria agar media with various concentrations of CM. The level of CM resistance was determined as the maximum concentration of CM at which cells could grow. Data shown are the averages of the results of at least three independent experiments. P, promoter; AT, antiterminator sequence; ATInv, AT in the reverse orientation; T, Rho-dependent terminator.

ND, not done.

The antitermination activity was dependent on the antiterminator sequence characteristics. Lack of (P+T) or inversion of (P+ATInv+T) the sequence decreased terminator readthrough to the basal level (1 to 4% of readthrough without terminator) (Table 2). The antiterminator sequence, whether in the forward or reverse orientation, also increased the measured cat expression of both σ70 and σ32 promoters by as much as threefold in mRNA level and fourfold in CMr level (groE; Table 2). This result was obtained with constructs lacking the terminator. Increased message stability or facilitation of translation (thus increasing mRNA lifetime) could account for the increased level of messages in the presence of the antiterminator sequence. The overall promoter activity and terminator readthrough were higher with the rrnG promoter than with the heat shock promoters we tested. The cat mRNA level (expressed as a cat/bla ratio) from the rrnGP2 promoter was 10- to 12-fold higher than those from heat shock promoters (before normalization to 100% for each promoter). This result is in agreement with previous measurements of the relative strength of rRNA operon versus those of other promoters (particularly heat shock promoters) (6, 19).

Our results show that the rrn operon antiterminator sequence can promote transcriptional antitermination of RNA polymerase molecules initiated from σ32-dependent promoters. Because the models for modification of RNA polymerase to a terminator-resistant state all involve the addition of new proteins factors, it is of interest to examine under which circumstances these modifications can take place (22). Why might RNA polymerase molecules initiated at σ32 promoters be refractive to such modifications? A smaller sigma factor may result in subtle conformation changes in RNA polymerase that in turn are unfavorable for adding modification proteins. Information as to when or even whether or not σ32 cycles off of RNA polymerase is not available. If σ32 were to change the conformation of or interfere with proper binding sites for the modification proteins, then terminator readthrough would not occur. Our findings suggest that the ability of RNA polymerase to interact with host antitermination factors is not affected by putative conformational changes in its structure that might result from an altered initiation status or association with alternative σ factors. We conclude that the initiation status of RNA polymerase is not a crucial parameter for transcriptional antitermination occurring 30 to 60 nucleotides downstream of the initiation region.

Acknowledgments

S. Kustu posed the question that prompted this study: does the rRNA-AT system function with other sigma factors? We appreciate her input and interest. We are grateful to C. Cerami and K. Eisinger for the construction of plasmids pSDK102, pSDK103, pSDK114, and pSDK115. We also thank C. A. Gross for the gift of pDC440 and pDC403 and M. J. Casadaban for strain MC1009. We thank A. L. Sonenshein for critically reading the manuscript. We thank the Tufts Core Facility in the Physiology Department for oligonucleotide preparation and DNA sequencing.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM 024751 to C.L.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aksoy, S., C. L. Squires, and C. Squires. 1984. Evidence for antitermination in Escherichia coli RRNA transcription. J. Bacteriol. 159:260-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Artsimovitch, I., and R. Landick. 2002. The transcriptional regulator RfaH stimulates RNA chain synthesis after recruitment to elongation complexes by the exposed nontemplate DNA strand. Cell 109:193-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bar-Nahum, G., and E. Nudler. 2001. Isolation and characterization of σ70-retaining transcription elongation complexes from Escherichia coli. Cell 106:443-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg, K. L., C. Squires, and C. L. Squires. 1989. Ribosomal RNA operon anti-termination. Function of leader and spacer region box B-box A sequences and their conservation in diverse micro-organisms. J. Mol. Biol. 209:345-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brewster, J. M., and E. A. Morgan. 1981. Tn9 and IS1 inserts in a ribosomal ribonucleic acid operon of Escherichia coli are incompletely polar. J. Bacteriol. 148:897-903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bujard, H., M. Brenner, U. Deuschle, W. Kammerer, and R. Knaus. 1987. Structure-function relationship of Escherichia coli promoters, p. 95-103. In W. S. Resnikoff et al. (ed.), RNA polymerase and the regulation of transcription. Elsevier, New York, N.Y.

- 7.Cowing, D. W., J. C. Bardwell, E. A. Craig, C. Woolford, R. W. Hendrix, and C. A. Gross. 1985. Consensus sequence for Escherichia coli heat shock gene promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:2679-2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Crombrugghe, B., M. Mudryj, R. DiLauro, and M. Gottesman. 1979. Specificity of the bacteriophage lambda N gene product (pN): nut sequences are necessary and sufficient for antitermination by pN. Cell 18:1145-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klotsky, R. A., and I. Schwartz. 1987. Measurement of cat expression from growth-rate-regulated promoters employing beta-lactamase activity as an indicator of plasmid copy number. Gene 55:141-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li, S. C., C. L. Squires, and C. Squires. 1984. Antitermination of E. coli rRNA transcription is caused by a control region segment containing lambda nut-like sequences. Cell 38:851-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mah, T. F., K. Kuznedelov, A. Mushegian, K. Severinov, and J. Greenblatt. 2000. The alpha subunit of E. coli RNA polymerase activates RNA binding by NusA. Genes Dev. 14:2664-2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mason, S. W., and J. Greenblatt. 1991. Assembly of transcription elongation complexes containing the N protein of phage lambda and the Escherichia coli elongation factors NusA, NusB, NusG, and S10. Genes Dev. 5:1504-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mason, S. W., J. Li, and J. Greenblatt. 1992. Direct interaction between two Escherichia coli transcription antitermination factors, NusB and ribosomal protein S10. J. Mol. Biol. 223:55-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgan, E. A. 1980. Insertions of Tn 10 into an E. coli ribosomal RNA operon are incompletely polar. Cell 21:257-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mukhopadhyay, J., A. N. Kapanidis, V. Mekler, E. Kortkhonjia, Y. W. Ebright, and R. H. Ebright. 2001. Translocation of σ70 with RNA polymerase during transcription: fluorescence resonance energy transfer assay for movement relative to DNA. Cell 106:453-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newlands, J. T., T. Gaal, J. Mecsas, and R. L. Gourse. 1993. Transcription of the Escherichia coli rrnB P1 promoter by the heat shock RNA polymerase (Eσ32) in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 175:661-668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nudler, E., and M. E. Gottesman. 2002. Transcription termination and anti-termination in E. coli. Genes Cells 7:755-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfeiffer, T., and R. K. Hartmann. 1997. Role of the spacer boxA of Escherichia coli ribosomal RNA operons in efficient 23 S rRNA synthesis in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 265:385-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross, W., S. E. Alyar, J. Salomom, and R. L. Gourse. 1998. Escherichia coli promoters with UP elements of different strengths: modular structure of bacterial promoters. J. Bacteriol. 180:5375-5383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Squires, C. L., J. Greenblatt, J. Li, and C. Condon. 1993. Ribosomal RNA antitermination in vitro: requirement for Nus factors and one or more unidentified cellular components. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:970-974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Squires, C. L., S. Pedersen, B. M. Ross, and C. Squires. 1991. ClpB is the Escherichia coli heat shock protein F84.1. J. Bacteriol. 173:4254-4262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torres, M., C. Condon, J. M. Balada, C. Squires, and C. L. Squires. 2001. Ribosomal protein S4 is a transcription factor with properties remarkably similar to NusA, a protein involved in both non-ribosomal and ribosomal RNA antitermination. EMBO J. 20:3811-3820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yura, T., H. Nagai, and H. Mori. 1993. Regulation of the heat-shock response in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47:321-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zellars, M., and C. L. Squires. 1999. Antiterminator-dependent modulation of transcription elongation rates by NusB and NusG. Mol. Microbiol. 32:1296-1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou, Y.-N., N. Kusukawa, J. W. Erickson, C. A. Gross, and T. Yura. 1988. Isolation and characterization of Escherichia coli mutants that lack the heat shock sigma factor σ32. J. Bacteriol. 170:3640-3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]