Abstract

Recent studies suggest that DNA polymerase η (polη) and DNA polymerase ι (polι) are involved in somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin variable genes. To test the role of polι in generating mutations in an animal model, we first characterized the biochemical properties of murine polι. Like its human counterpart, murine polι is extremely error-prone when catalyzing synthesis on a variety of DNA templates in vitro. Interestingly, when filling in a 1 base-pair gap, DNA synthesis and subsequent strand displacement was greatest in the presence of both pols ι and η. Genomic sequence analysis of Poli led to the serendipitous discovery that 129-derived strains of mice have a nonsense codon mutation in exon 2 that abrogates production of polι. Analysis of hypermutation in variable genes from 129/SvJ (Poli −/−) and C57BL/6J (Poli +/+) mice revealed that the overall frequency and spectrum of mutation were normal in polι-deficient mice. Thus, either polι does not participate in hypermutation, or its role is nonessential and can be readily assumed by another low-fidelity polymerase.

Keywords: genomic organization, immunoglobulin variable genes, DNA polymerase η, cytosine deamination, base excision repair

Introduction

The recent discovery of the Y-family of DNA polymerases (1) has provoked much investigation of their biochemical properties when they replicate damaged and undamaged DNA templates (2–5). One of the better characterized members of this large family is polη. Both Saccharomyces cerevisiae and human orthologs of polη can efficiently synthesize past various types of DNA damage (6–9), because their active sites are more accessible to solvents than that of a high fidelity polymerase (10). Humans with defects in their POLH gene are afflicted with the xeroderma pigmentosum variant (XP-V) phenotype, which is characterized by an increased sensitivity to ultraviolet light and sunlight-induced skin cancers (11). Thus, polη has an important biological role in protecting us from the deleterious effects of sunlight. Furthermore, as a result of its nonrestrictive catalytic site, polη misincorporates nucleotides on undamaged templates (12–14). Polη has been implicated in somatic hypermutation of antibodies, as immunoglobulin variable (V) genes from XP-V patients have an altered spectrum of mutations (15, 16), which is consistent with the types of mutations generated by polη in vitro (17, 18).

In addition to polη, humans possess three other Y-family polymerases, pols ι, κ, and Rev1, with polι being the most closely related to polη (19). Human polι has a limited ability to replicate past DNA lesions in vitro, suggesting that it is not as efficient as polη in translesion synthesis (20, 21). However, unlike polη, polι possesses a 5′ dRP lyase activity and may participate in a specialized form of base excision repair (22). Perhaps the most striking property of polι in vitro is its infidelity when replicating undamaged DNA. It is most error-prone when copying template T, where the enzyme misincorporates dGMP by 3- to 10-fold over the correct Watson and Crick base, dAMP (22–26). The biological function of polι remains unknown, and no human disease or repair-related deficiency has been directly linked to mutations in the POLI gene. Because of its extreme low-fidelity in copying undamaged DNA, polι is a good candidate for introducing mutations into V genes (23, 27). Indeed, during the course of our studies, Faili et al. (28) reported that a human Burkitt lymphoma cell line (BL2), with a homozygous deletion of both POLI alleles, is deficient in somatic hypermutation. As the first step toward understanding the biological function of polι in a whole-animal system, we assayed the frequency and pattern of mutations in V regions from the heavy chain locus in polι-deficient mice and compared them to similar data from polι-proficient mice.

Materials and Methods

Overexpression and Purification of Mouse Polι and Polη.

Cloning of the full-length mouse Poli cDNA in plasmid pJM297, has been described previously (19). An ∼2.8-kb NcoI to PsiI fragment from pJM297 was subcloned into the baculovirus expression vector pJM296 (23) that had been digested with NcoI and SmaI, to create the GST-Poli fusion construct, pJM306. GST-tagged mouse polι was overexpressed in SF9 insect cells infected with pJM306-derived baculovirus, and subsequently purified by Glutathione-agarose affinity chromatography and hydroxylapatite chromatography as previously described for the GST-tagged human polι (23). Histidine-tagged murine polη was overproduced and purified as described previously (29).

DNA Templates.

The synthetic oligonucleotides used as primers or templates in the in vitro replication assays were synthesized by Loftstrand Laboratories using standard techniques and were gel-purified before use. The sequence of each oligonucleotide is given in the legend of each figure. Primers were 5′-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (5000 Ci/mmol; 1 Ci = 37 GBq; Amersham Biosciences) using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Invitrogen).

Replication Reactions.

Radiolabeled primer-template DNAs were prepared by annealing the 5′-32P labeled primer to the unlabeled template DNA at a molar ratio of 1:1.5. For gapped templates, a second unlabeled oligonucleotide was also annealed to the template in a ratio of 1:2. Standard replication reactions (10 μl) contained 40 mM Tris•HCl pH 8.0, 5 mM MgCl2, 100 μM of each ultrapure dNTP (Amersham Biosciences), 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 250 μg/ml BSA, 2.5% glycerol, 10 nM 5′-[32P] primer-template DNA, and 3 nM GST-Polι. Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 30 min (unless noted otherwise), and reactions were terminated by the addition of 10 μl of 95% formamide/10 mM EDTA containing 0.1% xylene cyanol and 0.1% Bromophenol blue. Samples were heated to 100°C for 5 min and 5 μl of the reaction mixture was added to 20% polyacrylamide/7 M urea gels and separated by electrophoresis. Replication products were subsequently visualized by PhosphorImager analysis (FujiFilm Software Inc.).

Identification and Genomic Sequence of a Mouse Polι BAC Clone.

A BAC clone, 12337 (Incyte Genomics), containing ∼100 to 120 kb of DNA encompassing the mouse Poli genomic region was isolated by screening a BAC clone library using a mouse Poli EST (GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession no. AA162008) as a probe. The 12337 BAC clone was then subjected to random “shotgun” sequencing (NHGRI, NIH, Bethesda, MD). An approximate 36 kb DNA sequence of the mouse genome encompassing Poli has been deposited in GenBank and assigned the accession nos. AF489425 and AF489426.

PCR Genotyping of Murine Poli Codon 27.

To identify mutant or wild-type alleles of codon 27, an 88-bp fragment of mouse Poli exon 2 was amplified from mouse genomic DNA using the following forward (5′CAGTTTGCAGTCAAGGGCC) and reverse (5′TCGACCTGGGCATAAAAGC) primers. PCR amplifications were performed in a 20 μl reaction using AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (PE Biosystems) and 100–200 ng of genomic DNA with standard reaction conditions as suggested by the manufacturer. The reaction was performed for 45 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 57°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. A 10 μl aliquot from the completed PCR reaction was then treated with TaqI and incubated at 65°C for 1 h. The TaqI-treated and untreated portions of the PCR reaction were separated on a 6% polycrylamide gel (Invitrogen), and stained with ethidium bromide. Genomic DNAs from various strains of mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (C57BL/6J, 129/J, 129/SvJ, 129/ReJ); Novagen (BALB/c, ICR Swiss); or as a generous gift from Gilbertus van der Horst (Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands; 129/Ola).

Testis Extracts and Western Blot Analysis.

Testis tissues from various 129 or C57BL/6 mice were provided as a generous gift by Eric Wawrousek (National Eye Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD) or purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Protein extracts from mouse testis were prepared from frozen whole testes. The testes were thawed on ice in lysis buffer consisting of 9 M urea, 4% Nonidet P-40, 2% biolyte ampholyte 5/8 (Bio-Rad Laboratories), 2% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 1× Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Thawed testes were first minced and additional lysis buffer added to a final ratio of 8 ml to 1 g of tissue. The testis tissue was homogenized three times for 10–15 s on ice using a polytron PT3000 (Brinkmann Instruments) and the homogenate was then centrifuged for 1 h at 100,000 g at 22°C. The supernatant was removed and frozen on dry ice. Total protein concentration was determined by using the Bradford Protein assay dye reagent concentrate (Bio-Rad Laboratories). For Western blot analysis, ∼40 to 50 μg of total protein was subjected to electrophoresis in SDS-10% PAGE gels. Proteins were electro-transferred to an Immobilon P membrane (Millipore) and subsequently probed with a 1:5,000 dilution of polι polyclonal rabbit antibody raised against a 16-mer peptide (AEWERAGAARPSAHRC) corresponding to the very COOH terminus of murine polι that had been conjugated to Keyhole limpet hemocyanin antigen (Covance). Levels of mouse actin were used as protein loading controls and were detected using an anti-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). Mouse polι and actin proteins were subsequently visualized using the CSPD-chemiluminescent “Western Light” chemiluminescent assay (Applied Biosystems).

Mice Used for Hypermutation Studies.

129/SvJ and C57BL/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and used at 3–9 mo of age. Three 129/SvJ mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 100 μg of phenyloxazolone coupled to chicken serum albumin in Ribi adjuvant (Corixa), boosted after 2 mo, and killed 3 days later. 13 C57BL/6J mice were killed without immunization. Peyer's patches from both groups were removed from the small intestine, and cells were stained with phycoerythrin-labeled antibody to B220 (BD Biosciences) and fluorescein-labeled peanut agglutinin (PNA; E-Y Laboratories). B220+PNA+ cells, which are undergoing mutation, were isolated by flow cytometry, and DNA from ∼30,000 cells was prepared.

DNA Sequencing of Immunoglobulin V Genes.

The intron region downstream of rearranged V, diversity, and joining (J) gene segments on the heavy chain locus was sequenced. DNA was amplified using nested 5′ primers for the third framework region of VHJ558 gene segments and 3′ primers for 400 nucleotides downstream of the JH4 gene segment. Primers for the first PCR amplification were: forward 5′AGCCTGACATCTGAGGAC, and reverse 5′TAGTGTGGAACATTCCTCAC. Nested primers for the second amplification were: forward 5′CCGGAATTCCTGACATCTGAGGACTCTGC, and reverse 5′CGCGGATCCGCTGTCACAGAGGTGGTCCTG, with added EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites, respectively. Reaction conditions for the first primer set were 95°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1.5 min, 72°C for 2 min for 30 cycles, and for the second primer set were 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 1.5 min, and 72°C for 1 min for 30 cycles. PCR products were cloned into pBluescript (Stratagene) and sequenced by Lark Technologies (Houston, TX).

Results

Fidelity of Murine Polι Replication on Various DNA Templates.

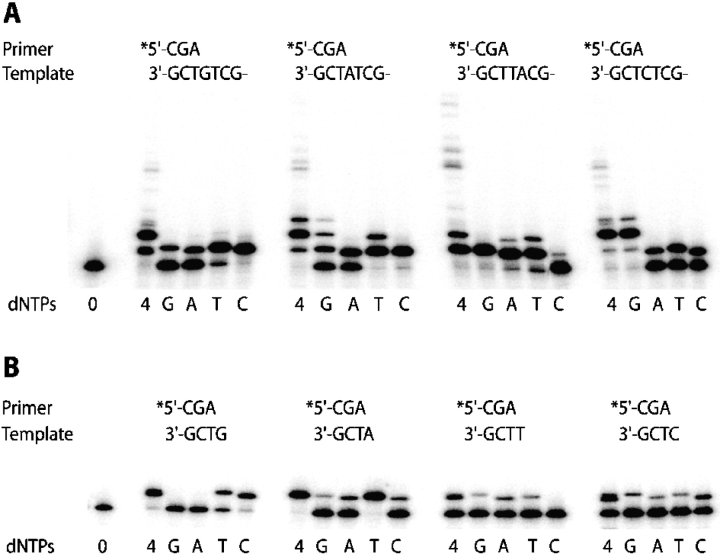

To determine the biochemical properties of murine polι, the enzyme was overproduced and purified as a recombinant GST-tagged protein from baculovirus-infected insect cells. Similar to our studies with human polι (23, 27), murine polι appears to be extremely error-prone. When replicating a recessed template, polι readily misincorporates dNMPs opposite most template bases, but does not put in dCMP opposite T (Fig. 1 A). When replicating the end of a template, murine polι is unable to misincorporate dGMP or dAMP opposite G, yet clearly favors the misincorporation of dCMP opposite template C (Fig. 1 B). Thus, like its well-characterized human ortholog, murine polι exhibits a template-dependent misincorporation pattern in vitro.

Figure 1.

Low-fidelity synthesis by murine polι. (A) Synthesis on a recessed template. The template was a 40 mer with a sequence 5′AGCGTCTTAATCTAAGCYXTCGCTATGTTTTCAAGGATTC where X was either G, A, T or C, and Y was T except when X was T, in which case Y = A. (B) Synthesis at the end of a template. The template was a 22 mer with a sequence 5′XTCGCTATGTTTTCAAGGATTC, where X was either G, A, T, or C. In both sets of experiments the primer for each reaction was a radiolabeled 16-mer with the sequence 5′CTTGAAAACATAGCGA, and the location of the hybridized primer on the respective template is underlined. The immediate local sequence context of each primer/template is given above each group of assays. The extent of murine polι-dependent (mis)incorporation was measured at each template site in the absence of dNTPs (0), all four dNTPs (4), or each individual dNTP.

Strand Displacement by Polι- and Polη during Gap Filling.

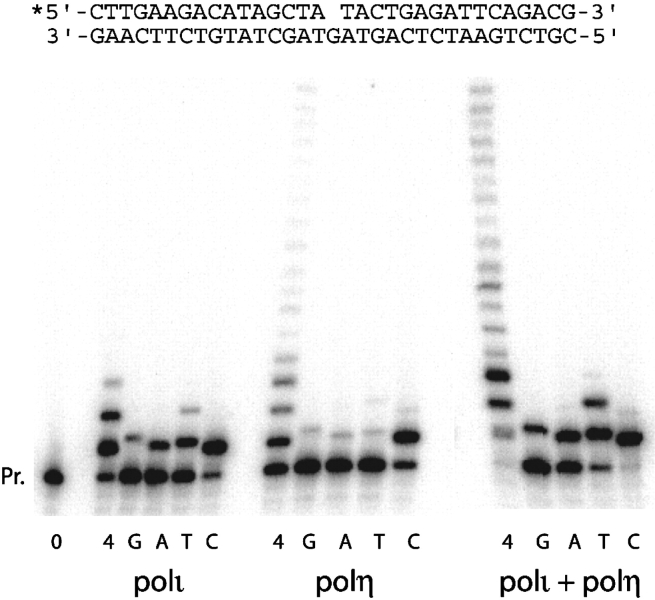

Recent studies suggest that an early event in somatic hypermutation is the deamination of cytosines in DNA (30). It is hypothesized that the resulting uracil moiety gives rise to C→T transitions if copied by a high-fidelity polymerase, or both transitions and transversions if uracil is removed by uracil DNA glycosylase to produce an abasic site which could be copied by an error-prone polymerase (30, 31). Alternatively, the abasic site could be further processed by base excision repair proteins into a single nucleotide gap (5, 32). As polι possesses intrinsic 5′ dRP lyase activity (22) and shows enhanced catalytic activity on gapped substrates (22, 27), it seems reasonable to think that polι might participate in such a pathway. Because polη has previously been implicated as being the A-T mutator in hypermutation (15, 18), we were interested in assaying the efficiency and accuracy of both polymerases in replicating a 1 base-pair gap. The template base chosen for the gap-filling reaction was dG, as such a substrate would be expected to occur through the deamination of the complementary dC. As seen in Fig. 2 , polι is active and error-prone on this substrate. In the presence of all four dNTPs, there is very limited strand displacement with 1–2 bases inserted at the original 1 bp gap. The correct base dCMP is preferentially inserted opposite template G, but dAMP and dTMP are also efficiently misinserted. Under the same conditions, polη is more accurate than polι, with the predominant insertion of the correct base, dCMP, and very little misinsertion of dAMP, dGMP, or dTMP. Both polymerases appear to replicate the 1 bp gap with roughly the same efficiency, but polη is clearly better at strand displacement than polι, and some primers are even fully-extended to the end of the template. When the two polymerases are added together, the major product of the 1 bp gap-filling assay is actually 3 bp long, and there appears to be significantly more strand displacement in the presence of both polymerases than in the presence of either polι or polη alone. Thus, both polι and polη can participate in a 1 bp gap-filling reaction, and their combined actions would lead to significant strand displacement.

Figure 2.

DNA synthesis by murine polι and polη on a 1 bp gapped substrate. The sequence of the gapped substrate is shown above the gel. The extent of murine polι- or polη-dependent (mis)incorporation was measured at each template site in the absence of dNTPs (0), all four dNTPs (4), or each individual dNTP (G, A, T, C). Pr. = radiolabeled primer. Reactions containing polι or polη alone, or together, lasted for 20 min at 37°C. From these experiments, one can see that polι is more error-prone than polη when replicating a template G in a gapped substrate and that when combined, the major products of the 1 bp gap-filling reaction are 3 bp and longer.

Genomic Structure of Murine Poli.

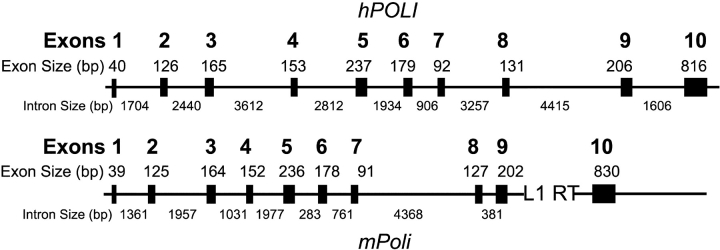

To achieve our initial goal of generating a polι-deficient mouse, we determined the entire genomic structure of the Poli gene located on a 120-kb mouse genomic BAC clone, 12337. The murine Poli gene was compared to the human gene, based on the human genomic sequence (GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession no.: NT_010893). Similar to human POLI, the mouse Poli gene has 10 exons (Fig. 3) . The gene spans a region of ∼23 kb on mouse chromosome 18, band E2, that shares synteny with human chromosome 18. Furthermore, the positions of introns and the sizes of exons are highly conserved between mouse and human genes. Intron 9 of the mouse gene has not been completely sequenced due to the presence of a mouse L1 retrotransposon sequence, which was detected by BLAST homology searches using the sequence of the 5′ and 3′ ends of the intron.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the genomic structure of the human POLI- and mouse Poli genes. Both genes consist of 10 exons (indicated as black boxes). The size of each exon and its intervening intron is given above and below the sequence respectively. The precise distance between exon 9 and 10 of Poli is unknown. However, the 5′ and 3′ ends of intron 9 match perfectly with an L1 retrotransposon which is 6.2 kb long.

129-derived Strains of Mice Have a Nonsense Mutation in Their Poli Gene.

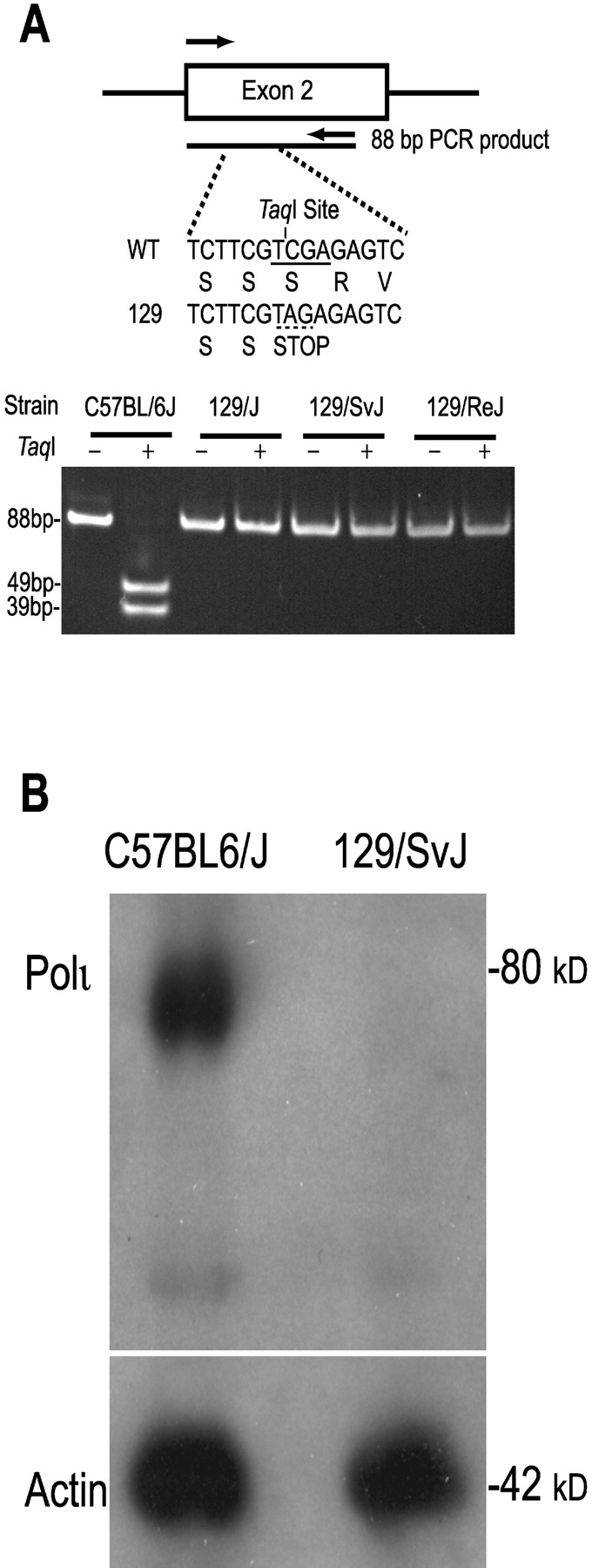

Sequence analysis of the 12337 BAC clone revealed a single nucleotide polymorphism in exon 2 which changed the wild-type Serine 27 codon, TCG, to an amber stop codon, TAG. As the clone came from a 129/SvJ mouse library, we determined if the mutation was present in other 129-derived strains. Fortuitously, the mutation can be easily detected, as it destroys a TaqI restriction site in the wild-type exon 2 (TCGA; wild-type serine codon 27 underlined). Using a PCR-based assay, we were able to genotype mouse strains for the presence or absence of the polymorphism. PCR products encompassing codon 27 from all of the mouse 129 strains analyzed (129/J, 129/SvJ, 129/ReJ, and 129/Ola) were undigested by the TaqI enzyme, indicating that they were homozygous for the nonsense mutation (Fig. 4 A). In contrast, TaqI digestion of the PCR product from C57BL/6J genomic DNA resulted in complete cleavage, showing that this strain is homozygous for the wild-type codon. Genotypic analysis of several other laboratory strains of mice such as BALB/c and ICR Swiss showed that they also had the wild-type codon for Poli (unpublished data).

Figure 4.

(A) PCR genotyping of Poli codon 27. An 88 bp fragment from exon 2 was amplified from genomic DNA. A unique TaqI restriction enzyme site (TCGA) is centrally located within this 88 bp PCR fragment. Substitution of C→A within the Ser27 codon (TCG) changes it to an amber stop codon (TAG) and simultaneously destroys the TaqI site. DNA with a wild-type sequence is cut by TaqI to generate restriction fragments of 39 and 49 bp, while DNA containing the substitution remains uncut. The gel analysis reveals that C57BL/6J has two wild-type alleles, whereas 129/J, 129/SvJ and 129/ReJ contain the amber codon on both alleles. (B) Western analysis of Polι in testis extracts. Testis extracts from C57BL/6J and 129/SvJ mice were separated in a 10% polyacrylamide-SDS gel and transferred to an Immobilon P membrane. The membrane was cut in half, and the top half containing high molecular weight proteins was probed with polyclonal antisera to polι, and the bottom half containing lower weight proteins was probed with polyclonal antisera to β-actin. Cross-reacting proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence. The data shows that while both extracts contain similar levels of β-actin, polι can only be detected in C57BL/6J mice (genotypically Poli +/+) and not in 129/SvJ (genotypically Poli −/−) mice.

In theory, the nonsense mutation should result in a polι protein consisting of just 26 amino acids. This truncation occurs well before any of the conserved polymerase domains of polι and should result in a complete loss of polι activity within the cell. To confirm that the mutation abrogated polι synthesis, the level of polι was analyzed by Western blotting of testis extracts, where polι is normally highly expressed (19, 27). Testis extracts from 129/SvJ and C57BL/6J mice were separated by gel electrophoresis, and polι was detected using an antibody raised against a peptide corresponding to the very COOH terminus of murine polι. This antibody recognizes full-length or mis-spliced variants containing the catalytic domain of polι. As shown in Fig. 4 B, extracts from C57BL/6J mice had significant levels of polι protein, whereas extracts from 129/SvJ mice had no detectable levels of full-length protein. Thus, the S27 nonsense mutation leads to a severe, if not total, deficiency in polι protein in 129 mice.

Hypermutation of Immunoglobulin Genes in the Absence of Polι.

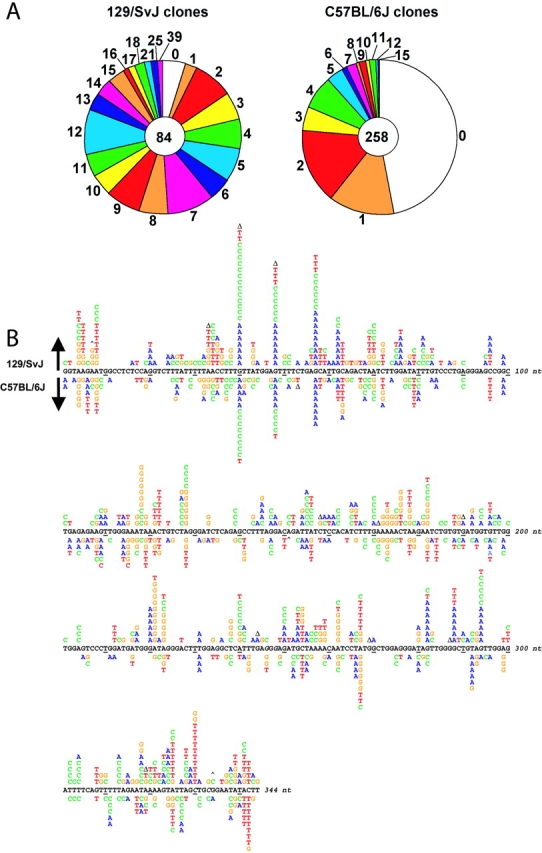

The availability of mice naturally deficient in polι gave us an opportunity to determine if polι is required for somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes. Mutations were identified in the intron region downstream of rearranged V genes on the heavy chain locus from both 129/SvJ and C57BL/6J mice. All the mutations in clones with different V rearrangements were counted, and only unique mutations in clones with the same rearrangements were scored. For 129/SvJ mice, 96% of the clones had mutations (81 out of 84); and for C57BL/6J mice, 53% of the clones were mutated (137 out of 258; Fig. 5 A). The overall frequency of mutation was 2.5% mutations/bp for 129/SvJ clones, and 0.5% mutations/bp for C57BL/6J clones. The frequency was probably higher in the 129/SvJ clones because the mice were inadvertently immunized before sacrifice, whereas the C57BL/6 mice were not immunized. For the 129/SvJ clones, 98% of the mutations were base substitutions (703 out of 715), and the rest were 9 deletions of 1–2 nucleotides, 1 deletion of 30 nucleotides, and 2 insertions of a single base. For the C57BL/6 clones, 99% of the mutations were substitutions (452 out of 454); the rest were a deletion of 1 nucleotide and an insertion of 44 nucleotides. Thus, there were very few insertions or deletions in either strain, with the vast majority of mutations being base substitutions.

Figure 5.

Frequency and location of mutations in the JH4 intron of rearranged V genes. (A) 129/SvJ clones from immunized mice had an overall frequency of 2.5% mutations/bp, and C57BL/6J clones from unimmunized mice had 0.5% mutations/bp. The total number of clones analyzed is shown in the center of each circle. The pie segments represent the proportion of clones that contained the specified number of mutations indicated. (B) The sequence of the 5′ nontranscribed strand from the 129/SvJ germ line is shown; 129/SvJ mutations are above the sequence and C57BL/6J mutations are below. Every tenth base is underlined. Δ, deletion; ^, insertion. Italicized nucleotides 246, 248, 330, and 333 are allelic variations in C57BL/6, which are A, A, T, and T, respectively. Mutations from the wild-type sequence to G are colored orange; A, blue; T, red; and C, green.

The types of base substitutions in the two groups of clones are shown in Table I. For both 129/SvJ and C57BL/6J clones, 56% of the changes were at A and T bases, and 44% were at G and C bases. The percent of individual types of substitutions was very similar between the two groups, with the exception of a decrease of C to T substitutions in the 129/SvJ clones (10%) compared with the C57BL/6 clones (17%), as recorded from the nontranscribed strand (P[χ2] = 0.01). The location of mutations in the intron sequence from both strains is diagrammed in Fig. 5 B. Both strains have mutations at DNA motifs that are associated with increased hypermutability, RGYW and WA (mutable positions are underlined; R = A or G, Y = C or T, W = A or T) (17, 33). For example, mutations at G in RGYW or RGYW-like sequences are seen in nucleotide positions 40, 48, and 57; and mutations at A in WA hotspots are found in positions 8, 267, and 325. The figure shows that the overall distribution of mutations is similar between the two strains.

Table I.

Spectra of Mutations in 129/SvJ and C57BL/6J JH Introns

| Substitution | 129/SvJ (689 mutations) |

C57BL/6J (452 mutations) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | ||

| A to: | G | 15 | 17 |

| T | 11 | 10 | |

| C | 10 | 6 | |

| T to: | C | 9 | 11 |

| A | 6 | 8 | |

| G | 5 | 4 | |

| G to: | A | 13 | 12 |

| T | 5 | 3 | |

| C | 8 | 5 | |

| C to: | T | 10 | 17 |

| A | 3 | 2 | |

| G | 4 | 3 | |

Values have been corrected to represent a sequence with equal amounts of the four nucleotides. All mutations are shown from the nontranscribed strand. Substitutions at four allelic nucleotides have been excluded from the comparison.

Discussion

129-derived Strains of Mice Lack Polι.

Like human polι, murine polι exhibits extremely low-fidelity synthesis when copying a variety of undamaged DNA templates. During the course of our attempts to generate a murine knock-out of Poli, we serendipitously discovered that inbred mice derived from the commonly-used 129 strains have a nonsense mutation at the beginning of the Poli gene. The amber codon replaces the Ser27 codon and results in a truncated protein lacking any catalytic function. Similar mutations producing short products have been identified in the human POLH gene encoding polη from XP-V patients. For example, the XP4BE mutation results in a 27 amino acid product, and the XP30RO mutation yields a 42-amino acid fragment (34). Both of these mutations lead to a severe XP-V phenotype which includes increased UV sensitivity, enhanced UV-induced mutations, and an elevated incidence of UV-induced skin cancers indicating that these mutations result in a loss of polη activity. As the mouse Poli mutation produces a similar truncation, it is likely that there is a severe defect in polι function(s) in 129 mice. Indeed, our inability to detect polι in Western blots of testis extracts from 129 mice supports such a conclusion.

As 129 mice have no detectable levels of polι, are there any phenotypes that can be attributed to this deficiency? The fact that 129 mice are viable suggests that polι is not essential for growth. However, although we did not detect polι protein in tissue extracts, it is possible that there is very limited suppression of the amber nonsense codon during development so as to produce enough protein for viability. Another possibility is that the 129 strain has mutations in other genes that could compensate for the lack of polι. Thus, the nonessential role of polι in development needs to be established genetically in mice with the mutation in a defined wild-type background. Concerning cancers, it has been observed that 129 strains are resistant to gamma radiation-induced thymic lymphomas (35), indicating that certain DNA lesions may be processed more accurately in the absence of polι.

One note of caution should be mentioned: many investigators use 129-derived embryonic stem cells for gene targeting. Although the recombinant mice are back-crossed to wild-type strains, experiments are often performed with F2 crosses that may carry the 129-derived Poli mutation. Indeed, we have analyzed a number of repair-deficient mice generated with 129 embryonic stem cells, and found that they have mixed +/+, +/−, and −/− genotypes for Poli (unpublished data). It is therefore possible that any repair phenotype previously associated with a particular gene knockout may also have been influenced by a deficiency in polι.

Normal V-Gene Hypermutation in Polι-deficient Mice.

Mutations are likely introduced into V genes by error-prone DNA polymerases during repair and/or replication of deaminated cytosines. To test if polι is involved, the frequency and pattern of mutations was studied in 129/SvJ mice. Mutations were examined in the JH4 intron region 3′ of rearranged V genes on the heavy chain locus. This 344-base region contains a high frequency of unselected mutations in clones from both immunized (36, 37) and unimmunized (38, 39) mice, ranging from 0.3% to 1.9% mutations per bp. In this study, clones from 129/SvJ mice had 2.5% mutations per bp, indicating that robust hypermutation can occur in the absence of polι. A normal level of hypermutation in Vκ genes from 129 mice has also been previously reported (38). Furthermore, the types and location of bases changes were similar between polι-deficient and proficient mice.

Based on these observations with the polι-deficient 129 mice, we conclude that either polι does not participate in hypermutation, or that its role is nonessential and can be readily assumed by another low-fidelity polymerase. These results contrast with those of Faili et al., who found that hypermutation does not occur in a human BL2 cell line with a homozygous deletion of POLI (28). Such differences might be due to short-term stimulation of B cells in culture where only polι may be available (40) versus long-term stimulation in mice where other DNA polymerases can substitute for polι in the hypermutation process.

Although polι-deficient mice undergo normal somatic hypermutation, there are experimental results that suggest polι helps to facilitate hypermutation. In polι-deficient BL2-cells, there was a reduction in G•C mutations (28), which suggests that in wild-type cells, polι has access to the site of deaminated cytosines to produce G•C mutations. In polι-deficient mice, there was a normal frequency of hypermutation at G, A, T, and C nucleotides, which is most likely due to synthesis by polη. While polη appears to be more accurate than polι in the gap-filling assay shown in Fig. 2, it is nevertheless a low-fidelity DNA polymerase (13, 41) and could easily generate mutations opposite all 4 base pairs through limited strand displacement. Interestingly, in polη-deficient humans, hypermutation occurs mostly at G•C pairs (15), which is consistent with synthesis by polι at a 1-bp gap and little to no strand displacement (Fig. 2), or replication by polι past an abasic site (24, 42). Finally, a recent study indicates that polι and polη physically interact and colocalize in replication foci in the nucleus (43). As shown here, gap-filling and subsequent strand displacement is most robust when both enzymes are added together, and such activities may result in the introduction of multiple mutations located several base pairs from the initial single nucleotide gap.

Further studies on the precise biological roles of the enigmatic polι are clearly necessary, and it is hoped that the wide availability of 129 strains of mice naturally deficient in polι will facilitate such research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jan Hoeijmakers and Henk Roest for helpful discussions of the phenotypes of the inbred 129 strains of mice; Gilbertus van der Horst for 129/Ola genomic DNA; Eric Wawrousek for kindly providing C57BL/6 and 129/SvJ testis tissues; David Winter and Xianmin Zeng for help with the hypermutation studies; and Alexandra Vaisman for assistance in making Figure 5.

This work was supported by the NIH Intramural research program (J.P. McDonald, E.C. Frank, B.S. Plosky, I.B. Rogozin, R. Woodgate, and P. Gearhart) and from the Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST) from the Japan Science and Technology Corporation (C. Masutani and F. Hanaoka).

Abbreviations used in this paper: pol, DNA polymerase; XP-V, xeroderma pigmentosum variant.

References

- 1.Ohmori, H., E.C. Friedberg, R.P.P. Fuchs, M.F. Goodman, F. Hanaoka, D. Hinkle, T.A. Kunkel, C.W. Lawrence, Z. Livneh, T. Nohmi, et al. 2001. The Y-family of DNA polymerases. Mol. Cell. 8:7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woodgate, R. 1999. A plethora of lesion-replicating DNA polymerases. Genes Dev. 13:2191–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodman, M.F., and B. Tippen. 2000. The expanding polymerase universe. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1:101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedberg, E.C., R. Wagner, and M. Radman. 2002. Specialized DNA polymerases, cellular survival, and the genesis of mutations. Science. 296:1627–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kunkel, T.A., Y.I. Pavlov, and K. Bebenek. 2003. Functions of human DNA polymerases η, κ and ι suggested by their properties, including fidelity with undamaged DNA templates. DNA Repair. 2:135–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson, R.E., S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 1999. Efficient bypass of a thymine-thymine dimer by yeast DNA polymerase, polη. Science. 283:1001–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Washington, M.T., R.E. Johnson, S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 2000. Accuracy of thymine-thymine dimer bypass by Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase η. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:3094–3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masutani, C., R. Kusumoto, S. Iwai, and F. Hanaoka. 2000. Mechanisms of accurate translesion synthesis by human DNA polymerase η. EMBO J. 19:3100–3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan, F., Y. Zhang, D.K. Rajpal, X. Wu, D. Guo, M. Wang, J.S. Taylor, and Z. Wang. 2000. Specificity of DNA lesion bypass by the yeast DNA polymerase η. J. Biol. Chem. 275:8233–8239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trincao, J., R.E. Johnson, C.R. Escalante, S. Prakash, L. Prakash, and A.K. Aggarwal. 2001. Structure of the catalytic core of S. cerevisiae DNA polymerase η. Implications for translesion DNA synthesis. Mol. Cell. 8:417–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cleaver, J.E., and D.M. Carter. 1973. Xeroderma pigmentosum variants: influence of temperature on DNA repair. J. Invest. Dermatol. 60:29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Washington, M.T., R.E. Johnson, S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 1999. Fidelity and processivity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase η. J. Biol. Chem. 274:36835–36838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuda, T., K. Bebenek, C. Masutani, F. Hanaoka, and T.A. Kunkel. 2000. Low fidelity DNA synthesis by human DNA polymerase-η. Nature. 404:1011–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson, R.E., M.T. Washington, S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 2000. Fidelity of human DNA polymerase η. J. Biol. Chem. 275:7447–7450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeng, X., D.B. Winter, C. Kasmer, K.H. Kraemer, A.R. Lehmann, and P.J. Gearhart. 2001. DNA polymerase η is an A-T mutator in somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin variable genes. Nat. Immunol. 2:537–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yavuz, S., A.S. Yavuz, K.H. Kraemer, and P.E. Lipsky. 2002. The role of polymerase η in somatic hypermutation determined by analysis of mutations in a patient with xeroderma pigmentosum variant. J. Immunol. 169:3825–3830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogozin, I.B., Y.I. Pavlov, K. Bebenek, T. Matsuda, and T.A. Kunkel. 2001. Somatic mutation hotspots correlate with DNA polymerase η error spectrum. Nat. Immunol. 2:530–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pavlov, Y.I., I.B. Rogozin, A.P. Galkin, A.Y. Aksenova, F. Hanaoka, C. Rada, and T.A. Kunkel. 2002. Correlation of somatic hypermutation specificity and A-T base pair substitution errors by DNA polymerase η during copying of a mouse immunoglobulin κ light chain transgene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:9954–9959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDonald, J.P., V. Rapic-Otrin, J.A. Epstein, B.C. Broughton, X. Wang, A.R. Lehmann, D.J. Wolgemuth, and R. Woodgate. 1999. Novel human and mouse homologs of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase η. Genomics. 60:20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tissier, A., E.G. Frank, J.P. McDonald, S. Iwai, F. Hanaoka, and R. Woodgate. 2000. Misinsertion and bypass of thymine-thymine dimers by human DNA polymerase ι. EMBO J. 19:5259–5266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaisman, A., E.G. Frank, J.P. McDonald, A. Tissier, and R. Woodgate. 2002. Polι-dependent lesion bypass in vitro. Mutat. Res. 510:9–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bebenek, K., A. Tissier, E.G. Frank, J.P. McDonald, R. Prasad, S.H. Wilson, R. Woodgate, and T.A. Kunkel. 2001. 5′-Deoxyribose phosphate lyase activity of human DNA polymerase ι in vitro. Science. 291:2156–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tissier, A., J.P. McDonald, E.G. Frank, and R. Woodgate. 2000. polι, a remarkably error-prone human DNA polymerase. Genes Dev. 14:1642–1650. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson, R.E., M.T. Washington, L. Haracska, S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 2000. Eukaryotic polymerases ι and ζ act sequentially to bypass DNA lesions. Nature. 406:1015–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang, Y., F. Yuan, X. Wu, and Z. Wang. 2000. Preferential incorporation of G opposite template T by the low-fidelity human DNA polymerase ι. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:7099–7108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaisman, A., A. Tissier, E.G. Frank, M.F. Goodman, and R. Woodgate. 2001. Human DNA polymerase ι promiscuous mismatch extension. J. Biol. Chem. 276:30615–30622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frank, E.G., A. Tissier, J.P. McDonald, V. Rapic-Otrin, X. Zeng, P.J. Gearhart, and R. Woodgate. 2001. Altered nucleotide misinsertion fidelity associated with polι-dependent replication at the end of a DNA template. EMBO J. 20:2914–2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faili, A., S. Aoufouchi, E. Flatter, Q. Gueranger, C.A. Reynaud, and J.C. Weill. 2002. Induction of somatic hypermutation in immunoglobulin genes is dependent on DNA polymerase ι. Nature. 419:944–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamada, A., C. Masutani, S. Iwai, and F. Hanaoka. 2000. Complementation of defective translesion synthesis and UV light sensitivity in xeroderma pigmentosum variant cells by human and mouse DNA polymerase η. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:2473–2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petersen-Mahrt, S.K., R.S. Harris, and M.S. Neuberger. 2002. AID mutates E. coli suggesting a DNA deamination mechanism for antibody diversification. Nature. 418:99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rada, C., G.T. Williams, H. Nilsen, D.E. Barnes, T. Lindahl, and M.S. Neuberger. 2002. Immunoglobulin isotype switching is inhibited and somatic hypermutation perturbed in UNG-deficient mice. Curr. Biol. 12:1748–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gearhart, P.J. 2002. Immunology: the roots of antibody diversity. Nature. 419:29–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogozin, I.B., and N.A. Kolchanov. 1992. Somatic hypermutagenesis in immunoglobulin genes. II. Influence of neighbouring base sequences on mutagenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1171:11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masutani, C., R. Kusumoto, A. Yamada, N. Dohmae, M. Yokoi, M. Yuasa, M. Araki, S. Iwai, K. Takio, and F. Hanaoka. 1999. The XPV (xeroderma pigmentosum variant) gene encodes human DNA polymerase η. Nature. 399:700–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newcomb, E.W., L.E. Diamond, S.R. Sloan, M. Corominas, I. Guerrerro, and A. Pellicer. 1989. Radiation and chemical activation of ras oncogenes in different mouse strains. Environ. Health Perspect. 81:33–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lebecque, S.G., and P.J. Gearhart. 1990. Boundaries of somatic mutation in rearranged immunoglobulin genes: 5′ boundary is near the promoter, and 3′ boundary is approximately 1 kb from V(D)J gene. J. Exp. Med. 172:1717–1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schenten, D., V.L. Gerlach, C. Guo, S. Velasco-Miguel, C.L. Hladik, C.L. White, E.C. Friedberg, K. Rajewsky, and G. Esposito. 2002. DNA polymerase κ deficiency does not affect somatic hypermutation in mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 32:3152–3160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frey, S., B. Bertocci, F. Delbos, L. Quint, J.C. Weill, and C.A. Reynaud. 1998. Mismatch repair deficiency interferes with the accumulation of mutations in chronically stimulated B cells and not with the hypermutation process. Immunity. 9:127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rada, C., M.R. Ehrenstein, M.S. Neuberger, and C. Milstein. 1998. Hot spot focusing of somatic hypermutation in MSH2-deficient mice suggests two stages of mutational targeting. Immunity. 9:135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poltoratsky, V., C.J. Woo, B. Tippin, A. Martin, M.F. Goodman, and M.D. Scharff. 2001. Expression of error-prone polymerases in BL2 cells activated for Ig somatic hypermutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:7976–7981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsuda, T., K. Bebenek, C. Masutani, I.B. Rogozin, F. Hanaoka, and T.A. Kunkel. 2001. Error rate and specificity of human and murine DNA polymerase η. J. Mol. Biol. 312:335–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McDonald, J.P., A. Tissier, E.G. Frank, S. Iwai, F. Hanaoka, and R. Woodgate. 2001. DNA polymerase iota and related Rad30-like enzymes. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 356:53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kannouche, P., A.R. Fernandez de Henestrosa, B. Coull, A. Vidal, C. Gray, D. Zicha, R. Woodgate, and A.R. Lehmann. 2002. Localisation of DNA polymerases η and ι to the replication machinery is tightly co-ordinated in human cells. EMBO J. 21:6246–6256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]