Abstract

We investigated whether Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 mediate gonadotropin subunit transcriptional responses to pulsatile GnRH in normal rat pituitaries. A single pulse of GnRH or vehicle was given to female rats in vivo, pituitaries collected, and phosphorylated JNK and p38 measured. GnRH stimulated an increase in JNK phosphorylation within 5 min, which peaked 15 min after GnRH (3-fold). GnRH also increased p38 phosphorylation 2.3-fold 15 min after stimulus. Rat pituitary cells were given 60-min pulses of GnRH or media plus the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (SP, 20 μm), p38 inhibitor SB203580 (20 μm), or vehicle. In vehicle-treated groups, GnRH pulses increased LHβ and FSHβ primary transcript (PT) levels 3-fold. SP suppressed both basal and GnRH-induced increases in FSHβ PT by half, but the magnitude of responses to GnRH was unchanged. In contrast, SP had no effect on basal LHβ PT but suppressed the stimulatory response to GnRH. SB203580 had no effect on the actions of GnRH on either LH or FSHβ PTs. Lβ-T2 cells were transfected with dominant/negative expression vectors for MAPK kinase (MKK)-4 and/or MKK-7 plus a rat LHβ promoter-luciferase construct. GnRH stimulated a 50-fold increase in LHβ promoter activity, and the combination of MKK-4 and -7 dominant/negatives suppressed the response by 80%. Thus, JNK (but not p38) regulates both LHβ and FSHβ transcription in a differential manner. For LHβ, JNK is essential in mediating responses to pulsatile GnRH. JNK also regulates FSHβ transcription (i.e. maintaining basal expression) but does not play a role in responses to GnRH.

GnRH REGULATES GONADOTROPIN subunit (α, LHβ, and FSHβ) transcription via a number of intracellular signaling pathways, including protein kinase A, protein kinase C (PKC), ERK, and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II (1,2,3,4). GnRH binding to the GnRH receptor (GnRH-R) activates several members of the GTP-associated protein family, including Gq and G11, resulting in activation of phospholipase Cβ, an increase in phosphoinositide turnover, and elevated diaclyglycerol levels, leading to an increase in the activity of PKC (2,5). GnRH-R binding also stimulates an increase in intracellular calcium that is derived from extracellular fluid (via L-type voltage sensitive calcium channels) and from inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-activated intracellular storage pools (2,6).

Recent findings reveal that calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II plays an important role in GnRH transcriptional regulation of all three pituitary gonadotropin subunit (α, LHβ, and FSHβ) genes (4,7). In contrast, published reports by our group and others found that ERK selectively mediates α- and FSHβ transcriptional responses to GnRH but is not involved in LHβ responses (8,9,10). To date, a LHβ-selective pathway for GnRH stimulation has yet to be characterized. Studies conducted in gonadotrope-derived cell lines (αT3 and LβT2 cells) reveal that GnRH activates two other members of the MAPK pathway, Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-1 through -3 and p38 (11,12,13). However, the role played by these two pathways in mediating responses to pulsatile GnRH has yet to be elucidated.

In αT3 cells, GnRH activation of the p38 pathway is mediated via PKC, resulting in an increase in c-Jun and c-Fos expression (12). However, there are few data to suggest a link between GnRH, p38 and regulation of gonadotropin subunit genes. Indeed, studies have shown that p38 does not mediate GnRH stimulation of α-subunit promoter activity in αT3 cells (12) or LHβ protein expression in LβT2 cells (13). Whether p38 plays a role in GnRH actions on gonadotropin subunit transcription in normal rat gonadotropes remains to be determined.

In contrast to GnRH regulation of the ERK and p38 pathways, studies in gonadotrope-derived cell lines reveal that GnRH stimulates phosphorylation of JNK via activation of c-Src and cdc42, independent of PKC (11,14). GnRH-induced activation of JNK stimulates the phosphorylation and expression of c-Jun and expression of activating transcription factor-3 but not c-Fos (15). Other findings suggest that JNK plays some role in GnRH stimulation of α, LHβ, and FSHβ promoter activity (10,11,16); however, the role that JNK plays on the transcriptional regulation of endogenous rodent gonadotropin subunit genes remains unknown.

The purpose of the present study was to investigate whether JNK and p38 are activated in the rat pituitary by GnRH and whether these two members of the MAPK family mediate LHβ and/or FSHβ transcriptional responses to pulsatile GnRH. Based on our findings, we report that both JNK and p38 are activated by GnRH and that JNK (but not p38) regulates LHβ and FSHβ transcription in a differential manner.

Materials and Methods

Rat in vivo studies

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Research Council, Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee. In a preliminary study, we used a GnRH-deficient model (17) (castrate, testosterone-replaced, adult male rats), and gave a single iv injection of GnRH (300 ng) via a jugular cannula and euthanized 5, 15, or 60 min later (controls received a BSA-saline injection; n = 4–5 animals/group). Pituitaries were collected, homogenized in tissue lysis buffer [50 μm HEPES, 100 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 1 μm aprotinin, 1 mm Na orthovanadate (pH 7.5)], protein content measured, and phospho-JNK and phospho-p38 determined by ELISA.

Rat in vitro perifusion studies

For each experiment, pituitaries from 36 adult rats were pooled and dissociated in medium containing 0.35% collagenase, 0.1% hyaluronidase, and 0.01% DNase. After dissociation, the cell suspension was aliquoted into 12 culture wells (5–6 × 106 cells/well) containing 22 mm plastic coverslips coated with Matrigel (Becton Dickinson, Bedford, MA). The cells were cultured for 48 h before beginning each experiment. The in vitro procedure and culture medium constituents have previously been described (7). To allow LHβ mRNA expression in response to pulsatile GnRH, testosterone [at a concentration present on proestrus, 500 pg/ml (18)] was added during the last 24 h of plating and during perifusion. After plating, the coverslips were inserted into custom-made chambers and allowed to equilibrate for 1 h before initiating treatment. The perifusion flow rate was 200 μl/min, and 100 μl pulses were administered over a 10-sec duration via autosyringe pumps. Studies were conducted as four separate experiments (12 chambers per experiment), with all treatment groups represented in each experiment (three chambers/treatment per experiment). Data from each experiment were expressed as percent change vs. vehicle-pulsed controls.

GnRH pulse studies (±JNK or p38 blockers).

Chambers were given pulses of GnRH (peak chamber concentration = 200 pm, medium pulses to controls) every 60 min for 24 h. For JNK blocker studies, cells were perifused with medium containing the JNK-specific inhibitor SP600125 (SP; 20 μm; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) or vehicle [inactive SP isoform (20 μm/0.25% dimethylsulfoxide; Calbiochem)]. For p38 inhibitor studies, cells were treated with medium containing the p38-specific blocker SB203580 (SB; 20 μm; Calbiochem) or vehicle (0.1% dimethylsulfoxide). The SP and SB doses selected were based on previously published reports showing effective suppression of GnRH-induced activation of the JNK or p38 pathways within gonadotrope-derived cell lines (12,15). LH and FSH secretory responses were determined by collecting 10-min perifusate fractions over 60 min after 2 and 22 h (for 24-h studies) of treatment. Cells were recovered 10 min after the last pulse; total RNA extracted with guanidinium thiocyanate; and α, LHβ, and FSHβ primary transcripts (PTs) determined by quantitative RT-PCR.

Transfection studies

Clonal LβT2 gonadotropes were originally obtained from Dr. Pamela Mellon (University of California, San Diego, San Diego, CA) and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic (Gibco, Grand Island, NY). For transfection, cells were plated using phenol red-free DMEM with 5% charcoal-stripped newborn calf serum and 2% l-glutamine at a concentration of 500,000 cells per 20-mm well. The following day, fresh phenol red-free DMEM 5% charcoal-stripped newborn calf serum was applied to cells before transfection with Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). A rat LHβ luciferase reporter construct containing 617 bp upstream of the transcriptional start site has been described previously (9) and was used at a concentration of 0.5 μg/well. Additionally, plasmid expression vectors for dominant-negative (DN) MAPK kinase (MKK)-4 (kindly provided by Dr. Michael Karin, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, CA) and/or MKK7 (kindly provided by Dr. Tse-Hua Tan, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX) have been previously described (19) and were transfected with the rat LHβ luciferase reporter (0.5 or 1.0 μg/well). In all experiments, either the MKK4 parent vector (puc19) or MKK7 parent vector (pcDNA3.1) was added so that total plasmid DNA per well equaled 1.5 μg/well. Approximately 16 h after transfection, cells were treated with either vehicle or 100 nm GnRH for 6 h. Cells were lysed using 1× Promega lysis reagent (Madison, WI) and luciferase activity measured with a TD-20e luminometer (Turner Designs, Mountain View, CA). Protein concentrations of each sample were assayed using a protein assay reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Data are expressed as fold change, compared with vehicle or treatment controls. At least four independent experiments were performed, with triplicate samples in each experiment.

Phospho-JNK and phospho-38 assays

Activated (phosphorylated) JNK and p38 were determined in pituitary cell lysate protein (3 μg per sample for phospho-JNK and 25 μg for phospho-p38 assays) using phospho-JNK and phospho-p38 ELISA kits provided by Assay Designs, Inc. (Ann Arbor, MI). All samples were run within a single assay.

Quantitative RT-PCR

α, LHβ, and FSHβ PT concentrations were determined by quantitative RT-PCR assay, as previously described (20). Primary transcript concentrations were expressed as femtomoles per 100 μg pituitary RNA. Intraassay coefficients of variation are 8.9 (α), 6.7 (LHβ), and 5.0% (FSHβ); interassay coefficients of variation are 22.2 (α), 19.2 (LHβ), and 14.1% (FSHβ). To reduce the effect of interassay variation, all samples from each experiment were run within a single PCR assay.

RIAs

LH and FSH secretory responses were measured in perifusate fractions by RIA, using reagents provided by the National Hormone and Pituitary Program (Torrance, CA). The assays were performed by the University of Virginia Center for Research in Reproduction, Ligand Assay and Analysis Core Facility. The RIA standards were NIDDK RP-3 (for LH) and RP-2 (for FSH). The assay sensitivities were 0.04 ng/tube for LH and 0.8 ng/tube for FSH. The coefficients of variation were 3.6 and 7.9% for the LH assay and 5.2 and 9.8% for FSH (intraassay and interassay, respectively). All samples from each experiment were assayed in a single RIA assay.

Statistical analysis

The data for phospho-JNK/p38, gonadotropin subunit PTs, and rat LH promoter activity were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, with differences between treatment groups determined by Duncan’ multiple range test. LH and FSH secretory data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA, with time and treatment as the primary effects.

Results

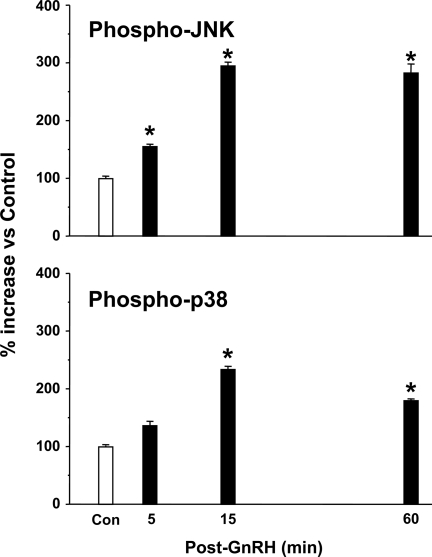

Figure 1 shows the pituitary JNK and p38 activational response to a single pulse of GnRH in GnRH-deficient rats in vivo, as determined by measuring phosphorylated JNK (Fig. 1, upper panel) and phosphorylated p38 (Fig. 1, lower panel). GnRH stimulated a rapid rise in JNK phosphorylation (50% increase vs. vehicle treated controls 5 min after the pulse; P < 0.05). Maximal increases (3-fold) were seen 15 min after the pulse (P < 0.05 vs. control), which was maintained after the 60-min time point. p38 phosphorylation also tended to increase 5 min after GnRH treatment, but peak values were observed 15 min after the GnRH pulse (2.5-fold increase vs. control; P < 0.05) and were maintained through 60 min.

Figure 1.

Pituitary JNK and p38 activation responses to a single pulse of GnRH. Adult male rats received a single pulse of GnRH [300 ng; BSA-saline to controls (Con)] and pituitaries were collected 5–60 min later (n = 4–5/group). Phospho-JNK and phosphor-p38 were determined by ELISA. Data are presented as percent change vs. Con; mean ± sem are shown. *, P < 0.05 vs. Con.

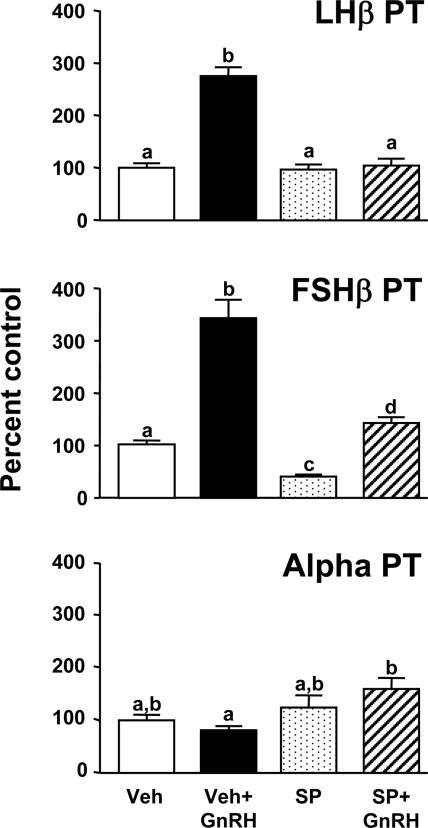

To investigate whether the observed rise in JNK phosphorylation in response to GnRH plays a role in gonadotropin transcriptional regulation, GnRH pulses were given for 24 h in the absence or presence of the JNK-specific inhibitor SP. As shown in Fig 2, GnRH stimulated increases in LHβ (3-fold) and FSHβ (3.5-fold) PT [P < 0.05 vs. vehicle (Veh) controls]. A GnRH-induced increase in α was not observed, but a small increase in α PT was observed in chambers given GnRH pulses+SP vs. GnRH+Veh (P < 0.05). SP suppressed both basal and GnRH-induced increases in FSHβ PT by half (vs. Veh controls; P < 0.05), but the magnitude of responses to GnRH (3.5-fold increase) was unchanged. In contrast, SP had no effect on basal LHβ PT (vs. Veh controls) but completely suppressed the stimulatory response to pulsatile GnRH.

Figure 2.

Gonadotropin subunit transcriptional responses to pulsatile GnRH ± JNK blockade. Cultured rat pituitary cells received pulses of GnRH (200 pm; media pulses to controls; 60-min interval) in the presence of the JNK blocker, SP (20 μm) or Veh for 24 h (n = 5–6/group). After completing the study, pituitary cells were recovered and gonadotropin subunit primary transcript levels determined. Groups marked with different letters are statistically different (P < 0.05).

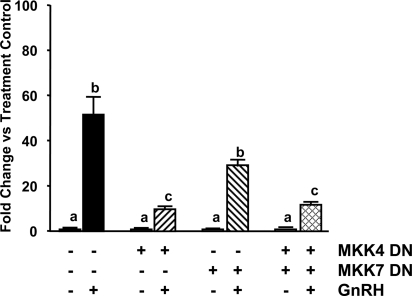

To confirm that the inhibitory effect of SP on LHβ transcriptional responses to GnRH is JNK pathway specific, follow-up studies were conducted using an experimental model in which JNK activation was suppressed by transfecting DN expression vectors for the two upstream activators of JNK (MKK-4 and MKK-7). Gonadotrope-derived Lβ-T2 cells were transiently transfected with a rat LHβ promoter/luciferase construct. Cells were cotransfected with MKK-4 DN or MKK-7 DN or in combination (controls were transfected with an equal amount of the appropriate empty plasmid vector). As shown in Fig. 3, 6 h of GnRH stimulated a 50-fold increase in LHβ promoter activity (P < 0.05 vs. Veh control). Treatment of the cells with MKK-7 DN reduced the LHβ promoter response to GnRH by 45% but did not achieve significance (vs. GnRH+Veh). In contrast, the MKK-4 DN suppressed the stimulatory effect of GnRH on LHβ promoter activity by 80% (P < 0.05 vs. GnRH+Veh). Of interest, the LHβ response to the combination of MKK-4 and MKK-7 DNs was not different from MKK-4 DN alone, suggesting that MKK-4 plays a primary role in GnRH-induced activation of JNK within the gonadotrope. Because the focus of this study was to investigate the role of JNK-mediating responses to pulsatile GnRH, cotransfection studies using MKK DNs and the rat FSHβ promoter were not included.

Figure 3.

Rat LHβ promoter responses to GnRH ± JNK blockade. Lβ-T2 cells were transiently transfected with a rat LHβ promoter-luciferase construct plus expression vectors containing MKK-4 DN, MKK-7 DN, or the combination of both (controls were transfected with an equal amount of parent vector). Sixteen hours after transfection, cells were treated with GnRH (100 nm) or vehicle for 6 h (n = 11–12/group). Upon completion of each experiment, cells were lysed and luciferase activity measured. Data are expressed as fold change vs. treatment controls. Groups marked with different letters are statistically different (P < 0.05).

The effect of SP on gonadotropin secretory responses to pulsatile GnRH after 2 and 22 h of treatment in vitro is shown in Fig. 4. LH (2 and 22 h) and FSH (2 h) release in SP controls were not different from Veh controls and are not shown. GnRH stimulated a pulsatile LH and FSH release pattern that continued over 22 h. LH secretory responses to GnRH alone or in combination with SP were similar. FSH release responses to GnRH were also similar in Veh and SP-treated groups after 2 h. FSH secretion after 22 h (in both control and GnRH-treated groups) was elevated, compared with the initial phase of the study (2-h time point). However, SP inhibited FSH secretion after 22 h (both basal and responses to GnRH; P < 0.05 vs. Veh-treated groups).

Figure 4.

LH and FSH secretion to pulsatile GnRH (media pulses to controls) ± JNK blockade (SP or Veh; see Fig. 2 for details). Ten-minute perifusate fractions were collected after 2 or 22 h of treatment. Arrows indicate the timing of the pulse. LH (2 and 22 h) and FSH (2 h) in SP-treated controls were similar to Veh-treated controls and are not presented. SP significantly suppressed FSH (22 h); Veh vs. SP controls (*, P < 0.05); Veh+GnRH vs. SP+GnRH (**, P < 0.05).

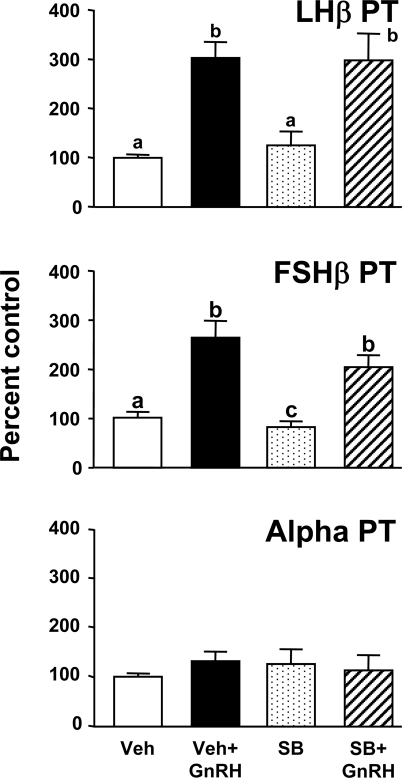

To determine whether GnRH-induced increases in p38 activation play a role in gonadotropin transcriptional regulation, GnRH pulses were given in the absence or presence of the p38-specific inhibitor, SB. Similar to results seen in Fig. 2, pulsatile GnRH stimulated 3-fold increases in both LHβ and FSHβ PT (P < 0.05 vs. Veh controls), but GnRH had no effect on α PT (Fig. 5). SB alone suppressed FSHβ slightly (20% decrease vs. Veh controls; P < 0.05). However, SB had no effect on the stimulatory actions of GnRH on either LHβ or FSHβ PT expression.

Figure 5.

The effect of p38 blockade on gonadotropin subunit transcription in vitro. Rat pituitary cells received pulses of GnRH (200 pm; 60 min interval; media pulses to controls; n = 5–6/group) in the presence of the p38 blocker, SB (20 μm) or Veh for 24 h. After completion, cells were recovered and gonadotropin subunit primary transcript levels determined. Treatment groups marked with different letters are statistically different (P < 0.05).

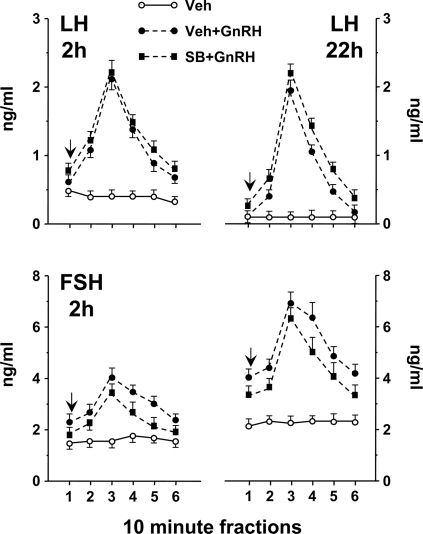

As shown in Fig. 6, GnRH pulses stimulated pulsatile secretion of both LH and FSH. For LH, the magnitude of responses to GnRH was similar after 2 and 22 h of treatment. For FSH, secretion in GnRH-treated groups increased after 22 h vs. the initial 2-h time point. p38 blocker (SB) treatment had no affect on either LH or FSH release, in contrast to results seen for JNK blockade on FSH (Fig. 4).

Figure 6.

Gonadotropin (LH and FSH) release to GnRH pulses (media pulses to controls) ± SB or Veh (see Fig. 5 for experimental details). Ten-minute fractions were collected after 2 and 22 h of treatment. LH and FSH in SB-treated controls were similar to Veh-treated controls and are not presented. Arrows indicate the timing of the pulse.

Discussion

The present study showed that a single pulse of GnRH stimulated phosphorylation of both JNK and p38 in vivo in the rat pituitary, with a similar time course to previous reports for gonadotrope-derived cell lines (12,13,16). Of particular significance, this study is the first to examine the role of JNK and p38 in the regulation of endogenous LHβ and FSHβ transcription by pulsatile GnRH in primary rodent pituitary cells. The results showed that the JNK pathway plays an essential role in regulating both the rat LHβ and FSHβ genes. However, JNK showed differential actions on these two gonadotropin subunit genes. For LHβ, JNK is a critical player in mediating responses to pulsatile GnRH but does not influence basal transcriptional activity. In contrast, blocking the JNK pathway reduced basal FSHβ PT, but the magnitude of responses to pulsatile GnRH remained unchanged.

At the secretory level, JNK blockade (SP) had no effect on either LH (after 2 or 22 h) or FSH (2 h) release. However, after 22 h, FSH secretion declined in both control and GnRH-treated groups, but responses to pulsatile GnRH were maintained. Interestingly, the pattern of FSH secretory responses to SP ± GnRH near the end (22 h) of the experiment was similar to that seen for FSHβ PT (i.e. a significant decrease in both basal and GnRH-induced stimulation, yet the magnitude of responses to GnRH was maintained). This suggests that ongoing basal transcription of FSHβ relates to both basal FSH secretion and responses to GnRH. Prior work showed that pituitary storage capacity of both LH and FSH in the rat is quite high, and significant decreases in pituitary content is not seen unless the GnRH stimulus is maintained for an extended period of time [e.g. after GnRH-induced gonadotropin surges on proestrus or after several hours of rapid frequency (e.g. 7.5-min interval)/high-amplitude pulses (21,22)]. It appears unlikely that the reduction in FSH release in the presence of the JNK blocker (SP) is due to a cytotoxic effect over time, because LH secretion [both basal (not shown) and responses to GnRH] were not reduced. Also, FSH secretion after 22 h in SP-treated cells was similar to responses seen in Veh and SP-treated groups after 2 h of treatment. Thus, the effect of SP on FSH after 22 h may represent a loss in the enhancement seen in other treatment groups (also seen in Fig. 6), rather than inhibition of secretion. These findings suggest that the JNK pathway may play a role in GnRH receptor activation/FSH secretion coupling over time.

The role of potential mediators of GnRH-R signaling has been investigated primarily using gonadotrope-derived cell lines (αT3 and LβT2 cells). Several studies have shown that alterations in intracellular calcium and PKC play a role in gonadotropin subunit transcription (23,24,25). Other reports demonstrated that the ERK pathway mediates α, FSHβ, and GnRH-R transcriptional responses to GnRH (15,16,26) but not LHβ (8,9,10). These later findings conflict with investigations showing that ERK does play a role in LHβ transcriptional responses to GnRH in some cell lines (11,27). Although the explanation for the different results are unclear, cell type, experimental treatment paradigms, and gene products measured (i.e. transfected promoter constructs of various sizes vs. endogenous genes) are likely factors.

Prior studies have examined the potential role played by the JNK pathway in mediating GnRH signaling in αT3 and LβT2 cells. Roberson and colleagues (15) showed that JNK cooperates with ERK to mediate human α-subunit transcriptional responses to GnRH. Other findings reveal that GnRH stimulates the ovine FSHβ promoter via the JNK pathway (16). Yokoi et al. (10) found that JNK mediates GnRH-induced stimulation of the rat LHβ promoter and that activation of c-Jun plays a role. Results also indicated that various components of the JNK activational cascade (including c-Src, CDC42, Rac, and SEK) are involved in the GnRH signal transduction pathway (11,16). In the present study using primary pituitary cells, the JNK-specific blocker (SP) completely suppressed the LHβ transcriptional response to pulsatile GnRH. This response was confirmed and extended by showing that DNs of the two primary upstream activators of JNK 1–3 (MKK-4 and MKK-7) suppress rat LHβ promoter stimulation by GnRH in Lβ-T2 cells. Of interest, these results suggest that MKK-4 is a major mediator of GnRH actions on the JNK pathway within the gonadotrope because the decrease in GnRH-induced stimulation of LHβ promoter activity in the presence of MKK-4 DN alone was similar to the combination of MKK-4 and MKK-7 DNs. In contrast to results seen for SP, DN treatment did not completely block the LHβ stimulatory response to GnRH. This difference may be due to the experimental models or end product measured. Similar partial LHβ promoter responses were seen by Harris et al. (11), using various transiently transfected JNK pathway DNs (i.e. c-Src, CDC42, Rac, and SEK).

The downstream mediator(s) of GnRH/JNK actions on rat LHβ transcription remain to be elucidated. GnRH-induced activation of JNK stimulates an increase in total and activated c-Jun in gonadotrope-derived cell lines (15), and transfecting a c-Jun DN suppressed GnRH stimulation of rat LHβ promoter activity (10). That same group described a region of the rat promoter (−95 to −86 bp) that contains 75% homology to the consensus activator protein-1 site and postulated that c-Jun might mediate JNK signaling via actions at this site. Another potential mediator of JNK actions is early growth response protein (Egr)-1 because JNK activation stimulates Egr-1 expression in the prostate (28). Binding sites for Egr-1 and other critical transcription factors (i.e. steroidogenic factor-1, pituitary homeobox-1) (28,29) are present in the proximal GnRH response element of the rat LHβ promoter. Rapid frequency GnRH pulses, the optimal signal pattern for LHβ transcription, was more effective than slower frequency pulses in stimulating Egr-1 mRNA, protein expression, and protein migration to the nucleus (27,30). Furthermore, we reported that pulsatile GnRH stimulates an increase in Egr-1 PT and mRNA, an effect that is completely suppressed by JNK blockade using SP (31).

Our data also suggest that JNK plays a stimulatory role in the regulation of the rat FSHβ gene. However, as apposed to LHβ, the effect appears to be primarily through actions on basal transcription. In contrast, studies conducted using the ovine FSHβ promoter showed that JNK partially mediates responses to GnRH (16). The observation that activator protein-1 plays a role in the ovine FSHβ promoter response to GnRH (32) as well as data showing that JNK stimulates c-Jun expression and phosphorylation in gonadotrope-derived cell lines (15), supports a role for JNK in the ovine system that differs from the rat.

Data in Figs. 2 and 5 show that α PT was not increased after 24 h of 60-min pulses of GnRH. Because 50% of basal α PT levels in primary pituitaries are contained in thyrotrope cells, responses to GnRH are less marked. Also, in previous in vitro time course studies, we showed that maximal increases in LHβ and FSHβ PT are seen after 24 h of GnRH pulses. However, that same study showed that α PT is maximally stimulated by 14 h of pulsatile GnRH treatment, with responses declining over longer durations (7). Because LHβ and FSHβ were the primary focus of this investigation, a 24-h experimental duration was chosen. Previous studies reported that the JNK pathway plays a role in human α transcription via activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor and partially mediates the stimulatory response to GnRH via activating transcription factor-3 (15,33). However, because we did not observe a GnRH-induced increase in α PT, we cannot say whether JNK plays a role in stimulating α-subunit transcriptional responses to GnRH in the rat.

Various investigators have shown that GnRH stimulates p38 activation within gonadotrope-derived cell lines (11,12,13), and the present study is the first to show similar responses within primary pituitary cells. Also, blocking p38 activation with SB did not suppress GnRH-induced responses for LHβ and FSHβ transcription or LH/FSH secretion. Our findings for LHβ are similar to previously published reports, which showed that p38 does not regulate LHβ protein expression (13). In contrast, p38 may play a role in mediating GnRH stimulatory effects on the ovine FSHβ gene (16,34). Studies by Miller and colleagues (34) showed that activation of the TGFβ receptor stimulates ovine FSHβ promoter activity via two pathways, activin and p38. Based on the present findings, p38 may also have a partial action on the rat FSHβ gene (Fig. 5) because blocking the p38 pathway (SB) produced a small suppression of basal FSHβ PT levels. However, the present results suggest that, unlike the ovine gene, GnRH does not stimulate rat FSHβ transcription through the p38 pathway.

In summary, the present results show that JNK, but not p38, plays an important role in mediating gonadotropin subunit transcription. More specifically, JNK regulates both LHβ and FSHβ transcription in a differential manner. For LHβ, JNK plays an essential role in mediating the transcriptional responses to pulsatile GnRH. The JNK pathway also regulates FSH, at both the transcriptional (i.e. maintaining basal FSHβ gene expression) and secretory levels. These findings present a potential intracellular mechanism for divergent regulation of gonadotropin subunit gene expression and LH/FSH secretion.

Footnotes

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grants HD-33039 and HD-11489 (to J.C.M. and D.J.H.) and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/National Institutes of Health through a cooperative agreement (U54-HD28934, Ligand Assay and Analysis Core, Molecular Core) as part of the Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproductive Research (to J.C.M., D.J.H., M.A.S.).

Disclosure Summary: D.J.H., L.L.B., H.E.W., J.S., K.W.A., and J.C.M. have nothing to disclose. M.A.S. received consulting fees as president of The Endocrine Society.

First Published Online October 11, 2007

Abbreviations: DN, dominant negative; Egr-1, early growth response-1; GnRH-R, GnRH receptor; JNK, Jun N-terminal kinase; MKK, MAPK kinase; PKC, protein kinase C; PT, primary transcript; SB, SB203580; SP, SP600125; Veh, vehicle.

References

- Kaiser UB, Conn PM, Chin WW 1997 Studies of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) action using GnRH receptor-expressing pituitary cell lines. Endocr Rev 18:46–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojilkovic SS, Catt KJ 1995 Novel aspects of GnRH-induced intracellular signaling and secretion in pituitary gonadotrophs. J Neuroendocrinol 7:739–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrel G, McArdle CA, Hemmings BA, Counis R 1997 Gonadotropin-releasing hormone and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide affect levels of cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) subunits in the clonal gonadotrope αT3-1 cells: evidence for cross-talk between PKA and protein kinase C pathways. Endocrinology 138:2259–2266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haisenleder DJ, Ferris HA, Shupnik MA 2003 The calcium component of GnRH-stimulated LH subunit gene transcription is mediated by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II. Endocrinology 144:2409–2416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Usui I, Evans LG, Austin DA, Mellon PL, Olefsky JM, Webster NJ 2002 Involvement of both Gq/11 and Gs proteins in gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor-mediated signaling in Lβ T2 cells. J Biol Chem 277:32099–32108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naor Z 1990 Signal transduction mechanisms of Ca2+ mobilizing hormones: the case of gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Endocr Rev 11:326–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haisenleder DJ, Burger LL, Aylor KW, Dalkin AC, Marshall JC 2003 GnRH stimulation of gonadotropin subunit transcription: evidence for the involvement of calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II activation in rat pituitaries. Endocrinology 144:2768–2774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haisenleder DJ, Cox ME, Parsons SJ, Marshall JC 1998 Gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulses are required to maintain activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase: role in stimulation of gonadotrope gene expression. Endocrinology 139:3104–3111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weck J, Fallest PC, Pitt LK, Shupnik MA 1998 Differential gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulation of rat luteinizing hormone subunit gene transcription by calcium influx and mitogen-activated protein kinase-signaling pathways. Mol Endocrinol 12:451–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoi T, Ohmichi M, Tasaka K, Kimura A, Kanda Y, Hayakawa J, Tahara M, Hisamoto K, Kurachi H, Murata Y 2000 Activation of the luteinizing hormone beta promoter by gonadotropin-releasing hormone requires c-Jun NH2-terminal protein kinase. J Biol Chem 275:21639–21647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris D, Bonfil D, Chuderland D, Kraus S, Seger R, Naor Z 2002 Activation of MAPK cascades by GnRH: ERK and JNK are involved in basal and GnRH-stimulated activity of the glycoprotein hormone LHβ-subunit promoter. Endocrinology 143:1018–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson MS, Zhang T, Li HL, Mulvaney JM 1999 Activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Endocrinology 140:1310–1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui F, Austin DA, Mellon PL, Olefsky JM, Webster NJG 2002 GnRH activates ERK 1 and 2 leading to the induction of c-fos and LHβ protein expression in Lβ-T2 cells. Mol Endocrinol 16:419–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvaney JM, Roberson MS 2000 Divergent signaling pathways requiring discrete calcium signals mediate concurrent activation of two mitogen-activated protein kinases by gonadotropin-releasing hormone. J Biol Chem 275:14182–14189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J, Bliss SP, Nett TM, Eersole BJ, Sealfon SC, Roberson MS 2005 Transcript profiling of immediate early genes reveals a unique role of ATF-3 in mediating activation of the glycoprotein hormone α-subunit promoter by GnRH. Mol Endocrinol 19:2624–2638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfil D, Chuderland D, Krause S, Shahbazian D, Friedberg I, Seger R, Naor Z 2004 ERK, JNK, p38 and s-Src are involved in GnRH-stimulated activity of the glycoprotein hormone FSH β-subunit promoter. Endocrinology 145:2228–2244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner RA, Bremner WJ, Clifton DK 1982 Regulation of LH frequency and amplitude by testosterone in the adult male rat. Endocrinology 111:2055–2061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush ME, Blake CA 1982 Serum testosterone concentrations during the 4-day estrous cycle in normal and adrenalectomized rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 169:216–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y, Gu J, Chakrabarti S, Aylor K, Marshall JC, Takahashi Y, Yoshimoto T, Nadler JL 2007 Role of 12/15 lipoxygenase in the expression of IL-6 or TNF-α in macrophages. Endocrinology 148:1313–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalkin AC, Burger LL, Aylor KW, Haisenleder DJ, Workman LJ, Cho S, Marshall JC 2001 Regulation of gonadotropin subunit gene transcription by gonadotropin-releasing hormone: measurement of primary transcript RNAs by quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction assays. Endocrinology 142:139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haisenleder DJ, Katt JA, Dee C, Ortolano GA, Marshall JC 1988 The influence of GnRH pulse amplitude, frequency and treatment duration on LH subunit mRNAs and LH secretion. Mol Endocrinol 2:338–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortolano GA, Haisenleder DJ, Dalkin AC, Iliff-Sizemore SA, Landefeld TD, Maurer RA, Marshall JC 1988 FSH β subunit mRNA concentrations during the rat estrous cycle. Endocrinology 123:2149–2151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss N, Llevi LN, Shacham S, Harris D, Seger R, Naor Z 1997 Mechanism of mitogen-activated protein kinase activation by gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the pituitary αT3-1 cell line: differential roles of calcium and protein kinase. Endocrinology 138:1673–1682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders BD, Sabbagh E, Chin WW, Kaiser UB 1998 Differential use of signal transduction pathways in the gonadotropin-releasing hormone-mediated regulation of gonadotropin subunit gene expression. Endocrinology 139:1835–1843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilyev VV, Lawson MA, Dipaolo D, Webster NJ, Mellon PL 2002 Different signaling pathways control acute induction versus long-term repression of LH β transcription by GnRH. Endocrinology 143:3414–3426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Conn PM 1999 Transcriptional activation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor gene by GnRH: involvement of multiple signal transduction pathways. Endocrinology 140:358–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanasaki H, Bedecarrats GY, Kam KY, Xu S, Kaiser UB 2005 GnRH pulse frequency-dependent activation of ERK pathways in perifused LβT2 cells. Endocrinology 146:5503–5513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inostroza J, Saenz L, Calaf G, Cabello G, Parra E 2005 Role of phosphatase PP4 in the activation of JNK-1 in prostate carcinoma cell lines PC-3 and LNCaP resulting in increased AP-1 and Egr-1 activity. Biol Res 38:163–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser UB, Halvorson LM, Chen MT 2000 Sp1, steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1), and early growth response protein 1 (Egr-1) binding sites form a tripartite gonadotropin-releasing hormone response element in the rat luteinizing hormone-β gene promoter: an integral role for SF-1. Mol Endocrinol 14:1235–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weck J, Anderson AC, Jenkins S, Fallest PC, Shupnik MA 2000 Divergent and composite gonadotropin-releasing hormone-responsive elements in the rat luteinizing hormone subunit genes. Mol Endocrinol 14:472–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson MA, Tsutsumi R, Zhang H, Talur I, Butler BK, Santos SJ, Mellon PL, Webster NJG 2007 Pulse sensitivity of the LHβ promoter is determined by a negative feedback loop involving Egr-1 and Ngfi-A binding protein 1 and 2. Mol Endocrinol 21:1175–1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haisenleder DJ, Burger LL, Aylor KW, Marshall JC JNK mediates Egr-1 transcriptional responses to pulsatile GnRH in the rat pituitary. Program of the 89th Annual Meeting of The Endocrine Society, Toronto, Canada, 2007 (Abstract P1-384), p 425 [Google Scholar]

- Vasilyev VV, Pernasetti F, Rosenberg SB, Barsoum MJ, Austin DA, Webster NJG, Mellon PL 2002 Transcriptional activation of the ovine involves multiple signal transduction pathways. Endocrinology 143:1651–1659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson MS, Ban M, Zhang T, Mulvaney JM 2000 Role of the cAMP response element binding complex and activation of MAPKs in synergistic activation of the glycoprotein hormone α subunit gene by EGF and forskolin. Mol Cell Biol 20:3331–3344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safwat N, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Gore J, Miller WL 2005 Transforming growth factor β-activated kinase 1 is a key mediator of ovine follicle-stimulating hormone expression. Endocrinology 146:4814–4824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]