Abstract

Müllerian inhibiting substance (MIS), the hormone required for Müllerian duct regression in fetal males, is also expressed in both adult males and females, but its physiological role in these settings is not clear. The expression of the MIS type II receptor (MISRII) in ovarian cancer cells and the ability of MIS to inhibit proliferation of these cells suggest that MIS might be a promising therapeutic for recurrent ovarian cancer. Using an MISRII-dependent activity assay in a small-molecule screen for MIS-mimetic compounds, we have identified the c-Jun N-terminal kinase inhibitor SP600125 as an activator of the MIS signal transduction pathway. SP600125 increased the activity of a bone morphogenetic protein-responsive reporter gene in a dose-dependent manner and exerted a synergistic effect when used in combination with MIS. This effect was specific for the MISRII and was not seen with other receptors of the TGFβ family. Moreover, treatment of mouse ovarian cancer cells with a combination of SP600125 and paclitaxel, an established chemotherapeutic agent used in the treatment of ovarian cancer, or with MIS enabled inhibition of cell proliferation at a lower dose than with each treatment alone. These results offer a strong rationale for testing the therapeutic potential of SP600125, alone or in combination with already established drugs, in the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer with a much-needed decrease in the toxic side effects of currently employed therapeutic agents.

MÜLLERIAN INHIBITING SUBSTANCE (MIS) is a glycoprotein hormone secreted by the newly differentiating testis during the fetal period where it is responsible for regression of the Müllerian ducts in males, which would otherwise develop into the internal female reproductive tract tissues (reviewed in Ref. 1). However, MIS is also produced during postnatal life in both male and female gonads. As a member of the TGFβ family, MIS signaling requires a set of membrane bound serine/threonine kinase receptors. After the type II receptor for MIS (MISRII) binds the MIS ligand, it recruits, phosphorylates, and activates one or more of three, activin receptor-like kinase type I receptors, Alk2, -3, or -6 (2,3,4,5,6). The activated type I receptor is thought to signal downstream by phosphorylating the receptor-specific Smad1/5/8, which translocate into the nucleus in a complex with the common Smad4 and bind to promoter regions to activate transcription of MIS-responsive genes (7).

In addition to its role during male fetal development, the continuous production of this hormone in both males and females after birth suggests a functional activity in the adult. One of the activities that has been ascribed to postnatal MIS has been as a tumor suppressor because it can inhibit tumor cell proliferation, including cells from breast (8,9), prostate (10,11), cervical (12), endometrial (13), and ovarian (14,15,16) cancers, in vitro and in vivo. Because MISRII appears to be expressed only in the gonads and other reproductive tract organs, targeting this receptor may provide specificity and minimize side effects associated with other systemic therapies. However, because producing large quantities of purified, biologically active MIS sufficient to be used therapeutically is challenging, we searched for a molecule that could be used either alone to mimic the effect of MIS by selectively activating the MISRII-mediated downstream signaling pathway or in combination with MIS to produce an additive or synergistic effect. This molecule could be helpful in the treatment of ovarian cancer or other MIS-responsive reproductive tumors in the clinic as a single agent or, more likely, in combination with reduced doses of MIS or with established chemotherapeutic agents.

Here we report that we have identified a c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) inhibitor, SP600125, as an activator of MISRII-mediated signaling in a small-molecule screen of approximately 15,000 compounds. SP600125 is an anthrapyrazole and a reversible ATP-competitive inhibitor of JNK (17), a serine/threonine protein kinase (18), and a member of the MAPK family. Three JNK genes have been identified in human (JNK1, -2, and -3), and SP600125 inhibits all isoforms with similar potency (17). JNKs have been implicated in processes such as oncogenic transformation (19), apoptosis (20), and cell proliferation, and as with other anthrapyrazoles, SP600125 has been shown to have antiproliferative properties (21,22). Based on our results, we hypothesize that activation of the MIS signal transduction pathway by SP600125 may have a therapeutic effect on reproductive tract cancer cells that are responsive to MIS.

Materials and Methods

Small-molecule screen

To identify molecules that interact with the MISRII, we developed a reporter assay where binding to MISRII activates a firefly luciferase reporter driven by the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-responsive element (BRE) promoter kindly provided by Dr. Peter ten Dijke (The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The BRE-luciferase reporter (23,24) has multiple optimized BREs (three Smad-binding elements, seven GC, and four CAGC) driving the expression of the firefly luciferase. This reporter construct together with a control Renilla luciferase reporter phRL-CMV (Promega, Madison, WI) and a rat MISRII cDNA expression construct (25) were transiently transfected into COS7 cells and plated in 384-well plates. Primary screens were performed at the Harvard Institute of Chemistry and Cell Biology screening facility. Compounds from chosen libraries were added at a volume of 100 nl at 5 mg/ml concentration in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) into 30 μl cell medium and cultured for 24 h at 37 C, after which the luciferase activity was measured with reagents from Promega according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A hit was identified as causing a fold induction over the plate median, and each compound was tested in duplicate in separate plates. MIS was used to control for intra- and interassay variability.

Cell culture

COS7 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% female fetal bovine serum. MOVCAR7 and 4306 cells were maintained in DMEM with 4% female fetal bovine serum as described (15,16). Cell lines were cultured in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37 C with added 2 mm l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. MIS (26) was produced in the laboratory from stably transfected CHO cells (27).

Transfection and reporter assay

COS7 cells were plated at a density of 5000 cells per well in 96-well plates for secondary screens. The day after plating, cells were transfected with rat MISRII receptors or EGFP-N1 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) together with the BRE firefly luciferase reporter construct and the control Renilla luciferase construct, phRL-CMV using TransIT-LT1 transfection reagent (Mirus Bio Corp., Madison WI). The following day, cells were treated with SP600125 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), JNK inhibitor VIII (Calbiochem), and/or MIS at the indicated concentrations for 24 h or as otherwise indicated for the time-course experiments in 1% serum medium. MOVCAR7 cells were transfected with the BRE and phRL-CMV luciferase reporters and treated with MIS and/or SP600125 at the indicated concentrations in growth medium for 24 h. Results were obtained using the dual luciferase reporter assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega). Plates were read in a Wallac Victor2 luminometer (PerkinElmer, Wellesley, MA). BMP2 and activin were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Proliferation assay

The effect of SP600125 on cell proliferation was measured by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay (28) in a mouse ovarian cancer cell line, MOVCAR7 cells, that were kindly provided by Dr. Denise Connolly, Fox Chase Cancer Center (Philadelphia, PA) (29). The 4306 cells were provided by Dr. Daniela Dinulescu, Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, MA) (30). Cells were plated at a density of 1000 cells per well in 96-well plates and treated 24 h later, and proliferation was measured on d 7 by registering the absorbance at 550 nm. Paclitaxel was manufactured by Ivax Pharmaceuticals and obtained from the Massachusetts General Hospital pharmacy.

Western blotting

Cells were washed in PBS, and lysates were prepared in 1× passive lysis buffer provided with the dual luciferase reporter assay kit (Promega). The lysates were cleared by centrifugation, and the protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Equal volumes of protein were loaded onto a NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gradient gel with MOPS buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose by electroblotting, the membrane was blocked in 5% milk Tris-buffered saline/Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with primary antibody (pJNK, c-jun, and phospho-cJun antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA; and JNK antibody came from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) overnight at 4 C in 5% BSA followed by incubation with secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antirabbit antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 1 h. Immunoreactive proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Anisomycin was purchased from Calbiochem.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by Student’s t test or ANOVA of the repeated experiments, followed by the Tukey’s post hoc test when appropriate with Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). When the control data were normalized to 1, these data were excluded from the statistical analyses. Synergy was calculated by two-way factorial ANOVA. For all analyses, significance was assigned at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

SP600125 activates a BMP-responsive promoter in MISRII-expressing cells

MIS-specific signaling requires the MIS type II receptor, and knockout studies in mice show phenocopy results when either MISRII or the MIS ligand is deleted (31,32). This has allowed us to develop an exquisitely precise screen for MIS signaling so that only cells that express MISRII initiate MIS downstream signaling. We used the BRE-luciferase reporter in COS cells cotransfected with an expression vector containing the rat MISRII receptor cDNA (25). This cell line expresses the three reported type I receptors, Alk2, -3, and -6 (data not shown). Screening of 15,000 compounds resulted in several hits that activated the MISRII at levels near those caused by its native ligand, MIS, in a reporter gene assay that identifies compounds that activate the BRE through MISRII interaction. The first suitable candidate to undergo further analysis after the primary screen was the JNK inhibitor II, also known as SP600125.

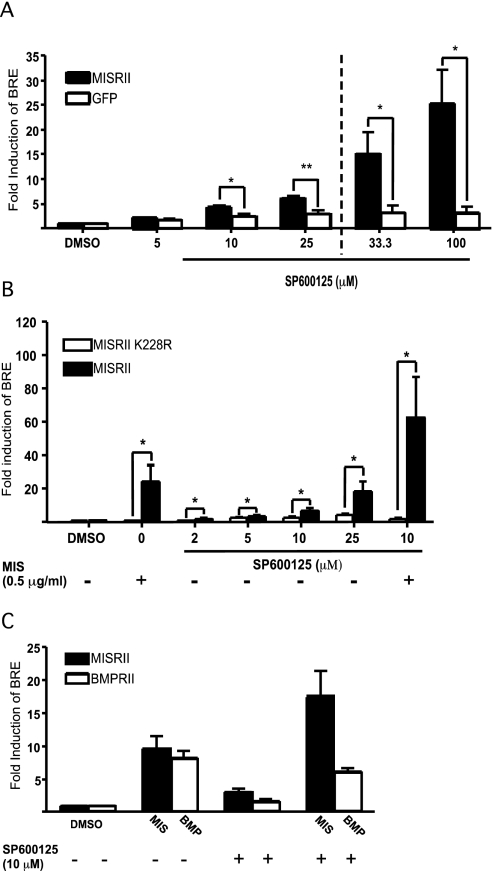

To characterize the activity of SP600125 and its effect on MIS signal transduction, we performed experiments with increasing concentrations of SP600125 and measured BRE-luciferase activity (Fig. 1A). SP600125 induced luciferase expression in a concentration-dependent manner in MISRII-transfected COS7 cells and at 25 μm reached 6-fold higher than that of vehicle-treated cells. Luciferase expression was also induced with 33.3 and 100 μm concentrations of added SP600125 by 15- and 25-fold, respectively (shown with bars after the dotted line) but the Renilla luciferase was inhibited by approximately 60%, suggesting toxic effects to the cells. Only cells transfected with MISRII showed a significant induction in luciferase activity, indicating that MISRII expression was necessary for SP600125 to induce MIS signaling in these cells.

Figure 1.

SP600125 induces MISRII-dependent BRE-luciferase reporter expression in COS7 cells and increases the MIS response in these cells. A, COS7 cells were transiently transfected with MISRII, BRE-luciferase, and phRL-CMV. The cells were treated with increasing doses of SP600125 for 24 h. Control cells were transfected with a control plasmid instead of the receptor to keep total DNA transfected constant. The results shown are the fold induction over vehicle-treated cells normalized to phRL-CMV expression to correct for variations in cell number and transfection efficiency. Bars shown to the right of the dashed line indicate that expression of Renilla luciferase was lower, suggesting toxic effects to the cells. The results represent the mean values from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (error bars represent sem; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). B, COS7 cells were transfected with normal MISRII or a kinase-deficient receptor MISRII K228R and treated with increasing doses of SP600125 and/or MIS for 24 h. Results shown represent the mean values from four independent experiments performed in triplicates (error bars represent sem; *, P < 0.05). C, COS7 cells were transfected with either MIS or BMP type II receptor together with BRE-luciferase reporter and treated with the respective ligand (MIS or BMP2) with or without SP600125 for 24 h. Results shown represent the mean values from three independent experiments.

To further demonstrate that the activating effect of SP600125 on BRE-luciferase was MISRII specific, we used a receptor construct where a conserved lysine (K228) in the ATP-binding region of the receptor was changed to an arginine (K228R), disabling the kinase activity of the receptor (4). In Fig. 1B, we show that neither MIS nor SP600125 activates BRE-luciferase when the kinase-deficient receptor is overexpressed. In addition we observed a further increase of the activity when MIS was added in combination with SP600125, an effect that was completely abolished with K228R, indicating that the serine/threonine activity of the MISRII is needed for activation of BRE-luciferase.

Little is known about the downstream signaling events that follow MIS binding to its receptor. Reporters that have been used to study MIS effects include the BMP-specific reporter genes XVent2 and Tlx (4). In this study, we used a BMP-responsive (BRE) promoter to drive expression of firefly luciferase. This reporter is also activated by BMPs but not by TGFβ or activin (23). To investigate the receptor specificity of SP600125 and exclude the possibility that this molecule activates other signaling pathways common for the TGFβ family, we transfected COS7 cells with a BMPRII expression construct and the BRE-luciferase reporter. As expected, 25 ng/ml BMP2, a ligand for BMPRII, induced BRE-luciferase activity in cells transfected with BMPRII. However, in contrast to the induction observed with the MISRII-transfected cells treated with MIS and SP600125, cotreatment of BMPRII-transfected cells with BMP2 and 10 μm SP600125 decreased luciferase activity by 25% compared with BMP2 alone (Fig. 1C).

In addition, we tested whether the type II receptors for TGFβ and activin responded to SP600125 by cotransfecting the corresponding receptor with a CAGA-promoter-driven luciferase reporter into COS7 cells. This reporter construct has been shown to be activated by both activin and TGFβ via the Smad3 pathway (33). However, SP600125 did not show any significant effect alone or in combination with the receptor-ligand (data not shown).

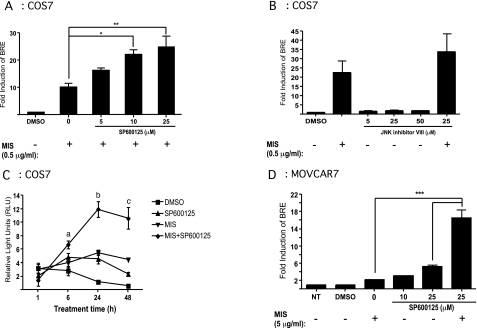

Synergy with SP600125 and MIS

In the next set of experiments, we assessed whether addition of MIS and SP600125 resulted in an additive effect or cooperated to provide a synergistic effect on BRE-luciferase activity. COS7 cells were cotransfected with the luciferase reporters and the MISRII expression construct, treated with a combination of MIS and SP600125, and compared with cells treated with MIS alone. In Fig. 2A, we show that MIS added at a final concentration of 0.5 μg/ml induced luciferase expression greater than 10-fold. Addition of as little as 5 μm SP600125 increased the MIS-mediated induction by approximately 16-fold, equivalent to an additional 6-fold over MIS alone. Increasing the concentration of SP600125 to 10 and 25 μm resulted in inductions of 22- and 25-fold, respectively. Statistical analyses by two-way ANOVA showed a synergistic effect on the activation of BRE-luciferase when MIS and SP600125 were combined compared with either alone. Addition of a different small-molecule inhibitor of JNK, JNK inhibitor VIII, did not result in any activation of BRE-luciferase at 5, 25, or 50 μm concentration, and no additional effect was seen when combined with MIS (Fig. 2B). Additionally, a peptide inhibitor, JNK inhibitor III, did not result in any activation of BRE-luciferase at 1 or 5 μm concentration, and no additional effect was seen when combined with MIS (data not shown). The synergy of SP600125 and MIS was also tested in a time-course experiment. In Fig. 2C, we show that 10 μm SP600125 and 0.5 μg/ml MIS maintain their synergistic effect on luciferase activity after 6 h through 48 h cotreatment over that of each treatment alone.

Figure 2.

SP600125 exerts a synergistic effect on BRE-luciferase induction in combination with MIS. A, COS7 cells transiently transfected with MISRII, BRE-luciferase, and phRLCMV were treated with MIS in combination with increasing doses of SP600125, and the BRE-luciferase response was measured after 24 h treatment. The results represent the mean values from three independent experiments performed in triplicates (error bars represent sem; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). B, Transiently transfected COS7 cells were treated with increasing doses of JNK inhibitor VIII with or without MIS. The results represent the mean values from three independent experiments. C, COS7 cells transiently transfected with MISRII, BRE-luciferase, and phRLCMV were treated with 0.5 μg/ml MIS and/or 10 μm SP600125 for 1, 6, 24, and 48 h. Luciferase activity was measured and normalized to phRL-CMV activity. The results show the relative light units (RLU) and represent the mean values from three independent experiments. a, P < 0.05 for MIS+SP600125 vs. DMSO; b, P < 0.05 for MIS and SP600125 vs. DMSO and P < 0.01 for MIS+SP600125 vs. MIS alone; c, P < 0.05 for MIS vs. DMSO and P < 0.01 for MIS+SP600125 vs. MIS. D, MOVCAR7 cells transfected with the BRE-luciferase and phRL-CMV were treated for 24 h, after which the cells were lysed and luciferase activity was measured and normalized to phRL-CMV. The figure shows the fold induction of BRE over untreated cells. The results shown are the mean values from three independent experiments (error bars represent sem; ***, P < 0.001).

To rule out the possibility that BRE-luciferase induction by SP600125 might be an artifact of MISRII overexpression in COS7 cells, we transfected the luciferase reporter constructs into a mouse ovarian cancer cell line, MOVCAR7, that expresses endogenous MISRII (16) and assayed for their response of these cells to MIS and SP600125. Treatment of the cells with 5 μg/ml MIS resulted in a 2-fold increase of BRE activity compared with untreated cells. Treatment with 25 μm SP600125 resulted in a 5-fold increase in BRE-luciferase activity compared with untreated control. The combined treatment with MIS and SP600125 gave a 16-fold increase in the BRE response, showing a synergistic effect with more than twice the activity of each treatment alone, which was similar to that observed in COS7 cells (Fig. 2A).

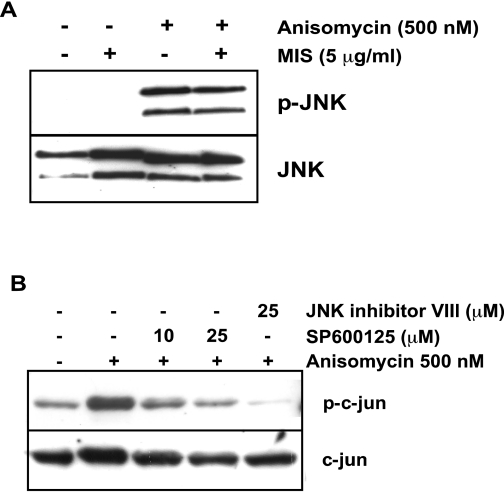

MIS does not activate JNK pathway

To test the possibility that the effects observed with SP600125 are the result of an indirect effect of MISRII-mediated activation of the JNK pathway, we treated MOVCAR7 cells with 5 μg/ml MIS and measured phosphorylation of JNK by immunoblotting (Fig. 3A). The known Jun kinase activator anisomycin was used as a positive control (34). However, no phosphorylation beyond background was observed after 30 min MIS treatment, although a strong activation was achieved with 500 nm anisomycin. Furthermore, MIS had no effect on phosphorylation of JNK by anisomycin. To examine the effects of SP600125 on phosphorylation of c-jun, a downstream target for phosphorylation by JNK, we pretreated MOVCAR cells with SP600125 before treatment with anisomycin and assessed phospho-c-jun by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3B). Although we observed inhibition of c-jun phosphorylation with 25 μm SP600125, at 10 μm SP600125, twice the concentration at which we observe synergy with MIS and paclitaxel (see below), we observed marginal and inconsistent inhibition of c-jun phosphorylation in our experiments, suggesting that the effects observed are not due to SP600125-mediated inhibition of the JNK signaling pathway. In addition, JNK inhibitor VIII almost completely blocked c-jun phosphorylation but does not activate BRE-luciferase (Fig 2B).

Figure 3.

MIS does not activate the JNK pathway. A, MOVCAR7 cells were treated with 5 μg/ml MIS, 500 nm anisomycin, or both for 30 min before harvesting and subjecting the lysates to Western blot analysis to detect the phosphorylated forms and total JNK; B, phosphorylation of c-jun was induced by 500 nm anisomycin. Cells were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of SP600125 or JNK inhibitor VIII. These results are representative of several experiments.

SP600125 inhibits proliferation of ovarian cancer cell lines

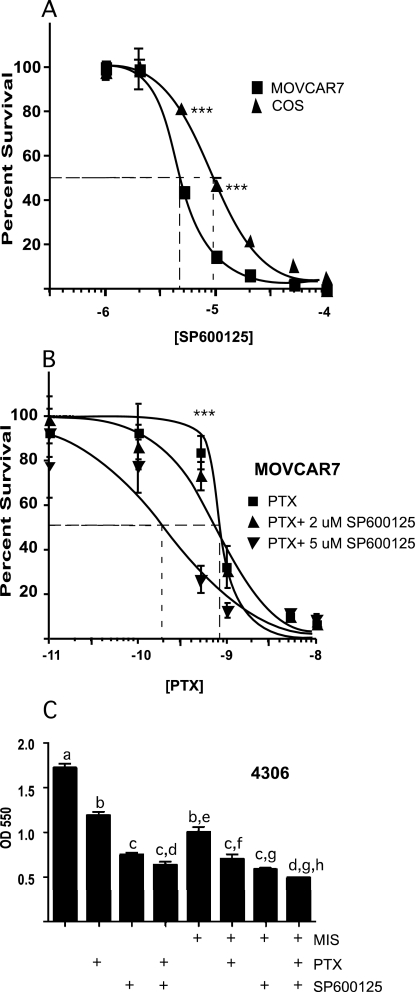

MIS inhibits both the proliferation of MOVCAR7 cells in vitro in proliferation assays and tumor growth in vivo when these cells are transplanted into an immunocompromised mouse model (16). Therefore, we tested whether SP600125 had similar effects on MOVCAR7 proliferation in vitro, again using the cell proliferation assay. The cells were treated for 7 d, and the proliferation was measured by spectrophotometry. To exclude cytotoxic effects on the cells unrelated to MIS signal transduction, we used untransfected COS7 cells as a negative control. Both cell lines have similar proliferation properties, and the effects of SP600125 can be roughly compared. The results (Fig. 4A) show that SP600125 inhibited cell proliferation in MOVCAR cells in a similar manner to MIS (15,16) and to a greater extent than in untransfected COS7 cells (IC50 4.5 vs. 9.5 μm, respectively). We also investigated whether SP600125 could potentiate the effect of an agent already established in the treatment of ovarian cancer, paclitaxel (Fig. 4B). Paclitaxel is used in treatment of a wide range of tumors, but the side effects can be debilitating (15,16). We chose 2 and 5 μm of SP600125 to test with paclitaxel because these doses inhibited MOVCAR7 cells but had a maximal effect on COS7 cells of only 20% (Fig. 4A). Combining 5 μm SP600125 with increasing doses of paclitaxel significantly shifted the curve to the left, and it has a progressively reduced slope compared with the paclitaxel alone (IC50 0.21 vs. 0.81 nm), suggesting that adjuvant therapy with SP600125 may be beneficial for patients undergoing treatment with paclitaxel.

Figure 4.

SP600125 inhibits proliferation of MOVCAR7 cells and increases the efficiency of paclitaxel-mediated inhibition of proliferation. Cells were plated in 96-well plates and treated the following day. Seven days later, cell survival was measured as described in Materials and Methods. A, Effect of SP600125 on cell proliferation and survival was assessed by comparing cell lines expressing MISRII and MOVCAR7 and cells that normally do not, COS7; B, increasing doses of a known ovarian cancer drug, paclitaxel (PTX), was used in combination with SP600125; C, effect of 2 μm SP600125, 10 μg/ml MIS, and 3 nm paclitaxel alone or in combination on another MIS-responsive mouse ovarian cancer cell line, 4306. The results shown are the mean values from three independent experiments (error bars represent sem. Significant differences at SP600125 concentrations between each cell line (A) or paclitaxel concentration between each treatment group (B) were determined by two-way factorial ANOVA; ***, P < 0.001). Significant differences (P < 0.05) in C were determined by one-way factorial ANOVA. If any given pair of bars shares the same letter, it is not significantly different.

We also tested whether SP600125 could inhibit the proliferation of another mouse ovarian cancer cell line that is inhibited by MIS, 4306 cells (15,16). In Fig. 4C, we show that SP600125 at a concentration of 2 μm inhibited the proliferation of 4306 cells by 50%. When combined with paclitaxel, SP600125 exerted a synergistically significant inhibition of 4306 proliferation over that of paclitaxel alone. If 2 μm SP600125 is combined with MIS or with MIS and paclitaxel, the level of cell proliferation is also significantly inhibited and with synergy over MIS alone. These results with another MIS-responsive ovarian cancer cell line suggest that SP600125 may also be helpful when MIS-paclitaxel combination therapy becomes available.

Discussion

The growing evidence showing that MIS can act as an inhibitor of tumor cell growth and as a potential therapeutic treatment for ovarian cancer encouraged us to screen for a small molecule that could mimic the receptor-mediated effects of MIS for use either alone or in combination with MIS or other chemotherapeutic agents. This screening identified SP600125 as a small-molecule activator of the MISRII signaling and a possible candidate for a drug with MIS-like effects. In this paper, we have shown that SP600125 activates signaling downstream of the MISRII in a receptor-dependent manner that is dependent on the kinase activity of the MISRII and that it has a synergistic effect on the cellular response to MIS. A role for the JNK pathway in MISRII signaling has not yet been reported, and we did not observe any phosphorylation of JNK by immunoblotting after treatment of cells with MIS. However, the JNK-pathway is involved in BMP2 signaling in osteoblasts (35,36) and is well documented in TGFβ-activated signal transduction (37,38,39,40) and should not be ruled out in MIS signaling as well as in other settings.

To exclude the possibility that JNK signaling pathway exerts a negative effect on MISRII signaling, we showed that other inhibitors to JNK, JNK inhibitor VIII, which is also a reversible ATP-competitive inhibitor of JNK (41), and JNK inhibitor III, a c-jun peptide inhibitor, had no effect on activation of the BRE-luciferase with or without added MIS. Furthermore, JNK inhibitor VIII is much more effective in inhibiting phosphorylation of c-jun than is SP600125, implying that it would have the same or greater effect on activation of MISRII-mediated signaling if the effect was mainly through inhibition of JNK. These findings suggest that SP600125 modifies MISRII signal transduction by interacting with the receptor or other molecules necessary for the activation of the receptor. How SP600125 interacts with MISRII is open to speculation, particularly because its ability to activate MISRII downstream signaling is counterintuitive when considering that it functions as a JNK inhibitor by reversibly occupying the ATP-binding site of JNK (42). It would be difficult to envision SP600125 similarly occupying the ATP-binding site of the kinase domain of MISRII and, in contrast to inhibiting JNK activity, activating the MISRII kinase activity. We suspect that SP600125 interacts with another site on the receptor, perhaps in the extracellular domain to activate downstream signaling.

Results from this study also show that SP600125 activates MISRII signaling in a concentration-dependent manner. This effect is specific for the MISRII and was not seen with cells that did not express MISRII or with transfection of other receptors of the TGFβ family. However, preliminary studies suggest that canonical Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation may not be involved in SP600125-mediated signaling (data not shown). Alternative pathways for MIS signaling that use nuclear factor-κB, p130, and p107 (9,12,43) have been described in a variety of cancer cell lines and might be operating in this setting as well. More studies are needed to determine the downstream signaling mechanisms used by SP600125-activated MISRII.

The specificity shown in the reporter assay using COS7 cells overexpressing the receptors encouraged us to investigate the effect of SP600125 on the proliferation of ovarian cancer cell lines expressing the MISRII (16). Using MOVCAR7 cells in the reporter assay showed a similar response pattern, indicating that this effect is not an artifact due to MISRII overexpression. We also showed that SP600125 inhibited the proliferation of MOVCAR7 cells to a significantly higher degree than it did in untransfected COS7 cells, thus indicating that endogenous MISRII could act as a target for SP600125, providing further evidence that it could be used as a targeted therapeutic to minimize cytotoxic side effects. The inhibitory effect of SP600125 on ovarian cancer cell proliferation was also observed in 4306 cells, another MIS-responsive cell line (15,16). Although these data are not direct evidence that the inhibitory effects of SP600125 on ovarian cancer cells is mediated by MISRII signaling, we do show that SP600125 activates the BRE-luciferase reporter in these MISRII-expressing cells (Fig. 2D), an effect that is synergistic with MIS. Additionally, MIS and SP600125 together had a greater effect on 4306 proliferation than with MIS alone (Fig. 4C). Taken together, the inhibitory effect of SP600125 on ovarian cancer cell proliferation in a manner similar to that observed with MIS (15,16), and the induced response of the BRE-luciferase reporter in MIS-expressing cells, leads us to speculate that SP600125 is affecting ovarian cancer cell proliferation at least in part by activating MISRII signaling.

SP600125 has been shown to inhibit the proliferation of human endothelial and prostate tumor cell lines both in vitro by arresting the cells in G2/M phase of the cell cycle and in vivo by inhibiting the growth of injected tumor cells and increasing the efficacy of cyclophosphamide treatment (21). Combined with our observations, these studies suggest that SP600125 may be beneficial in other cancer settings as well.

Paclitaxel has been used in the treatment of a wide range of tumors, including ovarian, breast, and prostate. It exerts its effect by targeting the microtubules and arresting the cells in G2/M phase, leading to the induction of apoptosis (44). In contrast to our findings, it has been shown that SP600125 reduced the apoptotic effect of paclitaxel on prostate cancer cells in vitro (45) and in ovarian cancer cells (46). One possible explanation for these discrepancies could be that higher doses of paclitaxel were used in these previous reports than those used in the experiments reported here. In fact, the effect of combination treatment was optimized at a lower concentration of paclitaxel. Furthermore, we used lower concentrations of SP600125, 2–5 μm compared with the 10–20 μm concentrations used in the experiments showing no apoptosis. Additionally, paclitaxel is thought to exert a biphasic apoptosis effect through a p53-dependent pathway that induces apoptosis at lower concentrations, whereas at higher concentrations, it inhibits p53 expression in a nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line (47). These data indicate that a concentration-dependent difference in apoptosis mediated by SP600125 alone or in combination with paclitaxel may be operative in different cells or tissues.

In conclusion, the identification of a small molecule that could act like MIS to cause MIS receptor-mediated downstream effects that result in inhibition of tumor cell proliferation is a step toward finding a therapeutic in treatment of MISRII-positive tumors. In this paper we have identified SP600125, a JNK inhibitor, as a small molecule that can mimic the effects of MIS in a receptor-specific manner. This molecule allows us to lower the effective concentration of MIS and might have a role in future treatment of ovarian cancer in concert with lower doses of already established drugs such as paclitaxel as well as MIS.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Institute of Chemistry and Cell Biology (ICCB) at Harvard Medical School for providing the small molecule library and for use of their facility.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant to P.K.D. from the National Cancer Institute (CA17393).

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to declare.

First Published Online October 18, 2007

Abbreviations: BMP, Bone morphogenetic protein; BRE, BMP-responsive element; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; MIS, Müllerian inhibiting substance; MISRII, MIS type II receptor.

References

- Teixeira J, Maheswaran S, Donahoe PK 2001 Mullerian inhibiting substance: an instructive developmental hormone with diagnostic and possible therapeutic applications. Endocr Rev 22:657–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouedard L, Chen YG, Thevenet L, Racine C, Borie S, Lamarre I, Josso N, Massague J, di Clemente N 2000 Engagement of bone morphogenetic protein type IB receptor and Smad1 signaling by anti-Mullerian hormone and its type II receptor. J Biol Chem 275:27973–27978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser JA, Olaso R, Verhoef-Post M, Kramer P, Themmen AP, Ingraham HA 2001 The serine/threonine transmembrane receptor ALK2 mediates Mullerian inhibiting substance signaling. Mol Endocrinol 15:936–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke TR, Hoshiya Y, Yi SE, Liu X, Lyons KM, Donahoe PK 2001 Mullerian inhibiting substance signaling uses a bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-like pathway mediated by ALK2 and induces SMAD6 expression. Mol Endocrinol 15:946–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamin SP, Arango NA, Mishina Y, Hanks MC, Behringer RR 2002 Requirement of Bmpr1a for Mullerian duct regression during male sexual development. Nature genetics 32:408–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Y, Fujino A, MacLaughlin DT, Manganaro TF, Szotek PP, Arango NA, Teixeira J, Donahoe PK 2006 Mullerian inhibiting substance regulates its receptor/SMAD signaling and causes mesenchymal transition of the coelomic epithelial cells early in Mullerian duct regression. Development 133:2359–2369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J, Wotton D 2000 Transcriptional control by the TGF-beta/Smad signaling system. EMBO J 19:1745–1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta V, Carey JL, Kawakubo H, Muzikansky A, Green JE, Donahoe PK, MacLaughlin DT, Maheswaran S 2005 Mullerian inhibiting substance suppresses tumor growth in the C3(1)T antigen transgenic mouse mammary carcinoma model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:3219–3224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segev DL, Ha TU, Tran TT, Kenneally M, Harkin P, Jung M, MacLaughlin DT, Donahoe PK, Maheswaran S 2000 Mullerian inhibiting substance inhibits breast cancer cell growth through an NFκB-mediated pathway. J Biol Chem 275:28371–28379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshiya Y, Gupta V, Segev DL, Hoshiya M, Carey JL, Sasur LM, Tran TT, Ha TU, Maheswaran S 2003 Mullerian inhibiting substance induces NFκB signaling in breast and prostate cancer cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 211:43–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran TT, Segev DL, Gupta V, Kawakubo H, Yeo G, Donahoe PK, Maheswaran S 2006 Mullerian inhibiting substance regulates androgen-induced gene expression and growth in prostate cancer cells through a nuclear factor-κB-dependent Smad-independent mechanism. Mol Endocrinol 20:2382–2391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbie TU, Barbie DA, MacLaughlin DT, Maheswaran S, Donahoe PK 2003 Mullerian inhibiting substance inhibits cervical cancer cell growth via a pathway involving p130 and p107. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:15601–15606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renaud EJ, MacLaughlin DT, Oliva E, Rueda BR, Donahoe PK 2005 Endometrial cancer is a receptor-mediated target for Mullerian inhibiting substance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:111–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephen AE, Pearsall LA, Christian BP, Donahoe PK, Vacanti JP, MacLaughlin DT 2002 Highly purified Mullerian inhibiting substance inhibits human ovarian cancer in vivo. Clin Cancer Res 8:2640–2646 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieretti-Vanmarcke R, Donahoe PK, Pearsall LA, Dinulescu DM, Connolly DC, Halpern EF, Seiden MV, MacLaughlin DT 2006 Mullerian inhibiting substance enhances subclinical doses of chemotherapeutic agents to inhibit human and mouse ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:17426–17431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieretti-Vanmarcke R, Donahoe PK, Szotek P, Manganaro T, Lorenzen MK, Lorenzen J, Connolly DC, Halpern EF, MacLaughlin DT 2006 Recombinant human Mullerian inhibiting substance inhibits long-term growth of MIS type II receptor-directed transgenic mouse ovarian cancers in vivo. Clin Cancer Res 12:1593–1598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett BL, Sasaki DT, Murray BW, O’Leary EC, Sakata ST, Xu W, Leisten JC, Motiwala A, Pierce S, Satoh Y, Bhagwat SS, Manning AM, Anderson DW 2001 SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:13681–13686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibi M, Lin A, Smeal T, Minden A, Karin M 1993 Identification of an oncoprotein- and UV-responsive protein kinase that binds and potentiates the c-Jun activation domain. Genes Dev 7:2135–2148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark GJ, Westwick JK, Der CJ 1997 p120 GAP modulates Ras activation of Jun kinases and transformation. J Biol Chem 272:1677–1681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Z, Dickens M, Raingeaud J, Davis RJ, Greenberg ME 1995 Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science 270:1326–1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis BW, Fultz KE, Smith KA, Westwick JK, Zhu D, Boluro-Ajayi M, Bilter GK, Stein B 2005 Inhibition of tumor growth, angiogenesis, and tumor cell proliferation by a small molecule inhibitor of c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 313:325–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Tsukada J, Higashi T, Mizobe T, Matsuura A, Mouri F, Sawamukai N, Ra C, Tanaka Y 2006 Growth suppression of human mast cells expressing constitutively active c-kit receptors by JNK inhibitor SP600125. Genes Cells 11:983–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korchynskyi O, ten Dijke P 2002 Identification and functional characterization of distinct critically important bone morphogenetic protein-specific response elements in the Id1 promoter. J Biol Chem 277:4883–4891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logeart-Avramoglou D, Bourguignon M, Oudina K, Ten Dijke P, Petite H 2006 An assay for the determination of biologically active bone morphogenetic proteins using cells transfected with an inhibitor of differentiation promoter-luciferase construct. Anal Biochem 349:78–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira J, He WW, Shah PC, Morikawa N, Lee MM, Catlin EA, Hudson PL, Wing J, Maclaughlin DT, Donahoe PK 1996 Developmental expression of a candidate Mullerian inhibiting substance type II receptor. Endocrinology 137:160–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahoe PK, Ito Y, Hendren WH 1977 A graded organ culture assay for the detection of Mullerian inhibiting substance. J Surg Res 23:141–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo HK, Teixeira J, Pahlavan N, Laurich VM, Donahoe PK, MacLaughlin DT 2002 New approaches for high-yield purification of Mullerian inhibiting substance improve its bioactivity. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 766:89–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T 1983 Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods 65:55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly DC, Bao R, Nikitin AY, Stephens KC, Poole TW, Hua X, Harris SS, Vanderhyden BC, Hamilton TC 2003 Female mice chimeric for expression of the simian virus 40 TAg under control of the MISIIR promoter develop epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res 63:1389–1397 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinulescu DM, Ince TA, Quade BJ, Shafer SA, Crowley D, Jacks T 2005 Role of K-ras and Pten in the development of mouse models of endometriosis and endometrioid ovarian cancer. Nat Med 11:63–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behringer RR, Finegold MJ, Cate RL 1994 Mullerian-inhibiting substance function during mammalian sexual development. Cell 79:415–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishina Y, Rey R, Finegold MJ, Matzuk MM, Josso N, Cate RL, Behringer RR 1996 Genetic analysis of the Mullerian-inhibiting substance signal transduction pathway in mammalian sexual differentiation. Genes Dev 10:2577–2587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennler S, Itoh S, Vivien D, ten Dijke P, Huet S, Gauthier JM 1998 Direct binding of Smad3 and Smad4 to critical TGFβ-inducible elements in the promoter of human plasminogen activator inhibitor-type 1 gene. EMBO J 17:3091–3100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazzalin CA, Le Panse R, Cano E, Mahadevan LC 1998 Anisomycin selectively desensitizes signalling components involved in stress kinase activation and fos and jun induction. Mol Cell Biol 18:1844–1854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemonnier J, Ghayor C, Guicheux J, Caverzasio J 2004 Protein kinase C-independent activation of protein kinase D is involved in BMP-2-induced activation of stress mitogen-activated protein kinases JNK and p38 and osteoblastic cell differentiation. J Biol Chem 279:259–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Ghayor C, Guicheux J, Magne D, Quillard S, Kakita A, Ono Y, Miura Y, Oiso Y, Itoh M, Caverzasio J 2006 Enhanced expression of the inorganic phosphate transporter Pit-1 is involved in BMP-2-induced matrix mineralization in osteoblast-like cells. J Bone Miner Res 21:674–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atfi A, Djelloul S, Chastre E, Davis R, Gespach C 1997 Evidence for a role of Rho-like GTPases and stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (SAPK/JNK) in transforming growth factor β-mediated signaling. J Biol Chem 272:1429–1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JI, Lee MG, Cho K, Park BJ, Chae KS, Byun DS, Ryu BK, Park YK, Chi SG 2003 Transforming growth factor-β1 activates interleukin-6 expression in prostate cancer cells through the synergistic collaboration of the Smad2, p38-NF-κB, JNK, and Ras signaling pathways. Oncogene 22:4314–4332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman R, Schiemann WP, Brooks MW, Lodish HF, Weinberg RA 2001 TGF-β-induced apoptosis is mediated by the adapter protein Daxx that facilitates JNK activation. Nat Cell Biol 3:708–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowa H, Kaji H, Yamaguchi T, Sugimoto T, Chihara K 2002 Activations of ERK1/2 and JNK by transforming growth factor β negatively regulate Smad3-induced alkaline phosphatase activity and mineralization in mouse osteoblastic cells. J Biol Chem 277:36024–36031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczepankiewicz BG, Kosogof C, Nelson LT, Liu G, Liu B, Zhao H, Serby MD, Xin Z, Liu M, Gum RJ, Haasch DL, Wang S, Clampit JE, Johnson EF, Lubben TH, Stashko MA, Olejniczak ET, Sun C, Dorwin SA, Haskins K, Abad-Zapatero C, Fry EH, Hutchins CW, Sham HL, Rondinone CM, Trevillyan JM 2006 Aminopyridine-based c-Jun N-terminal kinase inhibitors with cellular activity and minimal cross-kinase activity. J Med Chem 49:3563–3580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo YS, Kim SK, Seo CI, Kim YK, Sung BJ, Lee HS, Lee JI, Park SY, Kim JH, Hwang KY, Hyun YL, Jeon YH, Ro S, Cho JM, Lee TG, Yang CH 2004 Structural basis for the selective inhibition of JNK1 by the scaffolding protein JIP1 and SP600125. EMBO J 23:2185–2195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha TU, Segev DL, Barbie D, Masiakos PT, Tran TT, Dombkowski D, Glander M, Clarke TR, Lorenzo HK, Donahoe PK, Maheswaran S 2000 Müllerian inhibiting substance inhibits ovarian cell growth through an Rb-independent mechanism. J Biol Chem 275:37101–37109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla KN 2003 Microtubule-targeted anticancer agents and apoptosis. Oncogene 22:9075–9086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Ling MT, Wang X, Wong YC 2006 Inactivation of Id-1 in prostate cancer cells: a potential therapeutic target in inducing chemosensitization to taxol through activation of JNK pathway. Int J Cancer 118:2072–2081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang TH, Chan YH, Chen CW, Kung WH, Lee YS, Wang ST, Chang TC, Wang HS 2006 Paclitaxel (Taxol) upregulates expression of functional interleukin-6 in human ovarian cancer cells through multiple signaling pathways. Oncogene 25:4857–4866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan G, Heqing L, Jiangbo C, Ming J, Yanhong M, Xianghe L, Hong S, Li G 2002 Apoptosis induced by low-dose paclitaxel is associated with p53 upregulation in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer 97:168–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]