Abstract

Binding of the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) to the FGF receptor (FGFR) tyrosine kinase leads to receptor tyrosine autophosphorylation as well as phosphorylation of multiple downstream signaling molecules that are recruited to the receptor either by direct binding or through adaptor proteins. The FGFR substrate 2 (FRS2) family consists of two members, FRS2α and FRS2β, and has been shown to recruit multiple signaling molecules, including Grb2 and Shp2, to FGFR1. To better understand how FRS2 interacted with FGFR1, in vivo binding assays with coexpressed FGFR1 and FRS2 recombinant proteins in mammalian cells were carried out. The results showed that the interaction of full-length FRS2α, but not FRS2β, with FGFR1 was enhanced by activation of the receptor kinase. The truncated FRS2α mutant that was comprised only of the phosphotyrosine-binding domain (PTB) bound FGFR1 constitutively, suggesting that the C-terminal sequence downstream the PTB domain inhibited the PTB-FGFR1 binding. Inactivation of the FGFR1 kinase and substitutions of tyrosine phosphorylation sites of FGFR1, but not FRS2α, reduced binding of FGFR1 with FRS2α. The results suggest that although the tyrosine autophosphorylation sites of FGFR1 did not constitute the binding sites for FRS2α, phosphorylation of these residues was essential for optimal interaction with FRS2α. In addition, it was demonstrated that the Grb2-binding sites of FRS2α are essential for mediating signals of FGFR1 to activate the FiRE enhancer of the mouse syndecan 1 gene. The results, for the first time, demonstrate the specific signals mediated by the Grb2-binding sites and further our understanding of FGF signal transmission at the adaptor level.

THE FIBROBLAST GROWTH factor (FGF) signaling axis, consisting of 22 FGF ligands, four FGFR tyrosine kinases, and a bank of highly heterogeneic heparan sulfates, regulates a broad spectrum of cellular activities. The FGF elicits the regulatory activity by binding to FGF receptor (FGFR)-heparin sulfate complexes and inducing receptor autophosphorylation as well as phosphorylation of downstream signaling molecules. FRS2α, also called SNT1 for suc13-associating neurotrophic factor target 1, is phosphorylated by FGFR in response to FGF treatment and functions as an adaptor protein in the FGFR signaling axis (1,2). Tyrosine phosphorylation on FRS2α constitutes multiple binding sites that recruit several downstream signaling molecules to the FGFR signaling axis (1,2,3). The FRS2 family has two members, FRS2α and FRS2β, which share high homologies in amino acid sequence and structure domains. FRS2α is broadly expressed in adult and fetal tissues, whereas FRS2β is more restrictively expressed (4,5,6). Disruption of Frs2α alleles results in embryonic lethality at embryonic d 7 (E7)–E7.5 (4). Although FRS2β can compensate for the loss of FRS2α in MAPK activation in mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells (7), recent reports demonstrate that FRS2α and FRS2β may mediate different signals in cells (8,9,10,11). In addition, FRS2α phosphorylation appears to be FGFR isoform specific (12,13,14), which may result in differential recruitment of downstream signaling molecules and, thus, contribute to signaling specificity of the FGFR (12,14)

The first six amino acid residues at the N terminal of FRS2s consist of a myristylation site responsible for anchoring FRS2 to plasma membranes. Immediately downstream the myristylation site is a phosphotyrosine-binding (PTB) domain required for binding to the juxtamembrane domain of the FGFR (1,15), nerve growth factor receptor (TRK) (16), and possible other receptor tyrosine kinases (17). The PTB domain also binds Cks1, a molecule that triggers degradation of cell cycle regulatory protein p27kip1 during the G1/S transition in the cell cycle (18). A VT (valine-threonine) motif encoded by alternatively spliced sequences in the intracellular juxtamembrane domain of FGFR1 and FGFR2 has been reported to be important for association with FRS2α (15,16,19,20,21,22). Mouse embryos deficient in the VT-positive isoforms of FGFR1 develop multiple defects in different organs (23).

The C-terminal sequence downstream of the PTB domain contains multiple tyrosine and serine/threonine phosphorylation sites. Substitution of Tyr196, Tyr306, Tyr349, and Tyr392 with phenylalanine residues abrogates Grb2 recruitment, and substitutions of Tyr436 and Tyr471 abrogate Shp2 recruitment (24,25,26). Mice carrying mutations in the two Shp2 binding sites (Y436F and Y471F) exhibit a variety of developmental defects in many organs. In contrast, mice carrying mutations in the four Grb2 binding sites (Y196F, Y306F, Y349F, and Y392F) have a less severe phenotype (24,27). FGF stimulation also causes multiple threonine phosphorylations by MAPKs, thereby providing a negative feedback regulatory mechanism for the FGF signaling activity, because prevention of these phosphorylations by mutation results in enhancing the intensity and prolonging the duration of FGF signaling (28).

Binding of the FGF to the FGFR induces receptor tyrosine autophosphorylation. Seven autophosphorylation sites in the intracellular domain of FGFR1 have been reported (29,30). Among them, Tyr653, and possibly 654 in concert, are important for derepression of the FGFR1 kinase activity (29,30,31). Tyr766 at the C terminus is required for both PLC-γ phosphorylation (32,33) and the time-dependent acquisition of the proliferative response to FGFR1, although it is not necessary for FGFR1-mediated mitogenesis once it is acquired (12). It remains elusive whether these tyrosine autophosphorylation sites are important for FRS2 binding and whether the two FRS2 members, FRS2α and FRS2β, bind to FGFR kinases equally.

The FiRE element, a transcription enhancer from the mouse syndecan 1 gene, has two binding sites for Fos and Jun complexes (designated as Ap-1 sites). In fibroblasts, FiRE is induced only by members of the FGF family, and inhibition of either ERK or p38 MAPKs blocks FiRE activity (34,35). It has been shown that FGFR1 activates the FiRE via mitogenesis-independent pathways (12), but it remains undetermined whether FRS2α-mediated signals are required for the FiRE activation.

To address these issues, we expressed FRS2 and FGFR1 in 293T mammalian cells and Sf9 insect cells to characterize the interactions between FRS2α, FRS2β, and the FGFR1 tyrosine kinase. The results showed that both FRS2α and FRS2β bound to unactivated FGFR1 at a basal level. Furthermore, activation of FGFR1 enhanced binding of FRS2α, but not FRS2β, suggesting that the FGFR1-FRS2α binding was tyrosine phosphorylation regulated. Although not essential for interaction with FGFR1, deletion of the C-terminal sequence downstream of the PTB domain abrogated the regulation. Among the six phosphorylation sites, the four Grb2-binding sites were essential, whereas the two Shp2-binding sites were dispensable, for mediating FGFR1 signals to activate the FiRE enhancer of the mouse syndecan 1 gene. In addition, the alternatively spliced VT motif in FGFR1 was not obligatory for the binding of the receptor to FRS2, although it enhances the binding. The results augment the comprehension of FRS2α mediation of FGFR1 signals to downstream pathways and further our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the regulation of the signaling intensity and specificity of the FGFR1 signaling axis.

RESULTS

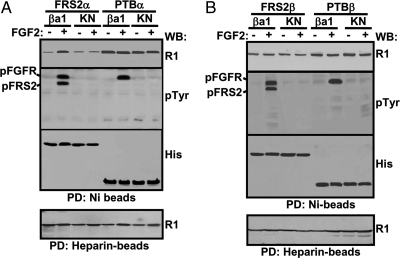

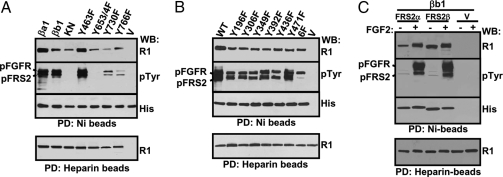

To determine whether the interaction of FRS2 with FGFR1 was tyrosine phosphorylation regulated, full-length FRS2α or FRS2β with a hexahistidine tag at the C terminus was coexpressed with FGFR1 in 293T cells. Before extraction with the lysis buffer, the cells were treated with 10 ng/ml FGF2 for 10 min. The cells were then lysed, and the FGFR1/FRS2α complexes were pulled down with Ni-beads for Western blot analyses. The results showed that both FRS2α and FRS2β pulled down unactivated FGFR1 at a basal level; preincubation with FGF2 increased the binding of FGFR1 with FRS2α (Fig. 1A) but not with FRS2β (Fig. 1B). The results suggest that activation of FGFR promotes the association of FGFR1 with FRS2α but not FRS2β. To confirm the results, the kinase-inactive mutant of FGFR1 (R1KN) (18) was used in similar experiments. The results demonstrated that both FRS2α and FRS2β only weakly interacted with R1KN, either with or without prior treatment of FGF2 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Tyrosine Phosphorylation Regulates the Interaction of FGFR1 with Full-Length FRS2α But Not FRS2β and PTB Domains

293T cells transiently coexpressing FRS2α (A) or FRS2β (B) with the indicated FGFR1 constructs were lysed with or without prior treatment of FGF2 for 10 min. The lysates were rocked with Ni- or heparin-agarose beads, and the specifically bound fractions were Western blotted with the indicated antibody. ba1, FGFR1βa1 isoform; KN, kinase-inactive mutant of FGFR1βa1; PTBα, PTB domain of FRS2α; PTBβ, PTB domain of FRS2β; pFGFR, phosphorylated FGFR1; pFRS2, phosphorylated FRS2; R1, anti-FGFR1 antibody; His, anti-His-tag antibody; pTyr, anti-phosphotyrosine antibody; PD, pull-down; WB, Western blot.

The PTB domain of FRS2 is responsible for the binding to the juxtamembrane domain of FGFR1 (15,25). To determine whether binding of PTB with FGFR1 was also tyrosine phosphorylation regulated, similar experiments were carried out with the truncated PTB domain of FRS2α (PTBα) and FRS2β (PTBβ). The results showed that both PTBα (Fig. 1A) and PTBβ (Fig. 1B) bound to wild-type FGFR1 and kinase dead FGFR1KN equally with or without FGF2 treatment, indicating that the FGFR1-PTB interaction was not FGFR1 kinase activity dependent. Interestingly, under the same conditions, the interaction of FGFR1 and the PTB domain was stronger than that of FGFR1 and the full-length FRS2. The results suggest that the C-terminal sequence downstream of the PTB domain inhibited the PTB-FGFR1 interaction, an effect that could be abrogated by tyrosine phosphorylation in the case of FRS2α but not FRS2β.

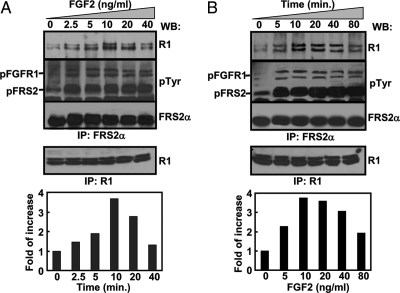

To further determine whether binding of endogenous FGFR1 and FRS2α was also enhanced by activation of the receptor, mouse prostatic tumor cells (TRAMP C2) that highly expressed FGFR1 and FRS2α were used in similar experiments. Pull-down experiments with anti-FRS2α antibody showed that FGF2 treatment increased FGFR1/FRS2α binding in a dosage-dependent manner (1) (Fig. 2A). The maximal effect was reached at the concentration of 10 ng/ml. Further increase of FGF2 concentration reduced the binding, which agreed with the previous finding that the FGF had biphasic activities in cells (36). In addition, the activity of FGF2 to promote FGFR1/FRS2α binding was time dependent; the maximal positive impact occurred at 10 min after the treatment and remained relatively constant until 40 min after the treatment (Fig. 2B). Together, the results confirmed that the interaction of FGFR1 and FRS2α is tyrosine phosphorylation regulated.

Figure 2.

The Endogenous FGFR1/FRS2α Interaction Induced by FGF2 Is Dosage and Time Dependent

The serum-starved TRAMP C2 cells were treated with FGF2 at the indicated concentrations for 10 min at 37 C (A) or treated with 10 ng/ml FGF2 for the indicated times (B) before being lysed. The FGFR1-FRS2α complexes pulled down from the cell lysates were Western blotted with the indicated antibodies. The bands representing FGFR1 were quantitated with a densitometer. The data were expressed as fold of increases from untreated samples. pFGFR, Phosphorylated FGFR1; pFRS2, phosphorylated FRS2; R1, anti-FGFR1 antibody; His, anti-His-tag antibody; pTyr, anti-phosphotyrosine antibody; Shp2, anti-Shp2 antibody; PD, pull-down; WB, Western blot.

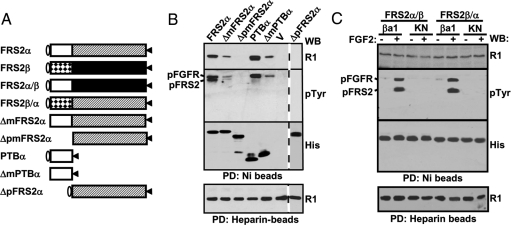

In addition, data in Fig. 3B also demonstrate that the PTB domain of FRS2α is the only FGFR1-binding domain. To confirm this, chimeric FRS2α/β and FRS2β/α were constructed in which the C-terminal domains downstream from the PTB domains were swapped between the two FRS2 members. Pull-down experiments showed that both chimeric mutants bound FGFR1 constitutively and strongly (Fig. 3C) and were phosphorylated upon FGF2 treatment. It is possible that the conformations of chimeric FRS2 mutants and their wild-type counterparts may not be identical, and the chimeric mutants may not have the right conformation to negatively impact the binding. Thus, the result is consistent with the data that conformational changes induced by tyrosine phosphorylation lift the negative impact imposed by the C-terminal sequence on the PTB-FGFR1 binding.

Figure 3.

The FRS2α C-Terminal Domain Is Required for Phosphorylation-Regulated FGFR1/FRS2α Interaction

A, Schematic of FRS2 mutants. Oval, The conserved myristylation sequence; open box, PTBα; dotted box, PTBβ; hatched box, the C-terminal sequence of FRS2α; solid box, the C-terminal sequence of FRS2β; triangles, the hexahistidine tag. B, The Sf9 expressed FRS2α mutants and FGFR1 kinase were incubated with Ni- or heparin-agarose beads as described, and the specifically bound fractions were subject to Western analyses as described. C, The 293 cells cotransfected with the assigned FGFR1 and FRS2 mutants were treated with 10 ng/ml FGF2 for 10 min where indicated before being lysed with the lysis buffer. The cell lysates were incubated with Ni- and heparin-beads as specified, and the specifically bound fractions were subjected to Western analyses as described. βa1, FGFR1βa1 isoform; KN, kinase-inactive mutant of FGFR1βa1; pFGFR, phosphorylated FGFR1; pFRS2, phosphorylated FRS2; R1, anti-FGFR1 antibody; His, anti-His-tag antibody; pTyr, anti-phosphotyrosine antibody; PD, pull-down; WB, Western blot; dotted lines indicate that the data were put together from different gels.

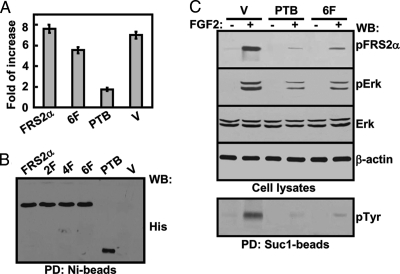

Because the PTB domain bound FGFR1 better than the full-length FRS2 did, we then tested whether the PTB domain could be a better dominant-negative inhibitor for the FGF signaling in comparison with full-length inactive mutants in NIH 3T3 cells that expressed endogenous FGFR1 and FRS2α at medium levels. The results showed that expression of PTBα significantly reduced the FGF2-induced FiRE-luciferase reporter expression, FRS2α phosphorylation, and MAPK activation (Fig. 4). In contrast, expression of the 6F mutant carrying point mutations in all six tyrosine phosphorylation sites only partially inhibited the FGF2 activity in NIH 3T3 cells. Thus, the results demonstrate that the PTB domain is a more effective dominant-negative inhibitor than full-length inactive mutants for the FGF signaling.

Figure 4.

The Dominant-Negative Inhibition Activity of the PTB Domain

A, NIH 3T3 cells cotransfected with the indicated FRS2α mutants and the FiRE-luciferase reporter were stimulated with FGF2 overnight where indicated. The cells were then lysed, and the luciferase activity was measured. After being normalized with the cell number, the data derived from three experiments are presented as fold of increases in response to FGF2 treatments. B, The expressed FRS2α mutants in the same cells as in A were enriched with Ni-beads and Western analyzed with the anti-His-tag antibody. C, NIH 3T3 cells transfected with the indicated FRS2α mutants were treated with FGF2 for 10 min where indicated before being lysed with the RIPA buffer. The cell lysates were Western analyzed with the indicated antibodies. Bottom panel, the same cell lysates were incubated with Suc13-beads, and the specifically bound fractions were Western analyzed with the anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. His, Anti-His-tag antibody; Erk, anti-Erk antibody; pErk, anti-phosphorylated Erk; pFRS2α, anti-phospho-FRS2α antibody; pTyr, anti-phosphotyrosine antibody; PTB, PTB domain of FRS2α; 2F, FRS2α2F mutant; 4F, FRS2α 4 F mutant; 6F, FRS2α mutant with substitutions of all six phosphorylation sites with phenylalanine residues; V, vector only; PD, pull-down; WB, Western blot.

The aforementioned data that tyrosine phosphorylation enhanced FGFR1-FRS2α interaction prompted us to test whether the effect was due to FGFR1 and/or FRS2α phosphorylation. The intracellular domain of FGFR1 has five major tyrosine autophosphorylation sites, Tyr463, Tyr653, Tyr654, Tyr730, and Tyr766 (29,30). To study the impact of receptor tyrosine autophosphorylation on interaction with FRS2α, a series of FGFR1 mutants bearing point mutations on the tyrosine phosphorylation sites were coexpressed with FRS2α in Sf9 cells. Pull-down assays showed that substitution of the autophosphorylation sites Tyr653/654, Tyr730, and Tyr766, but not Tyr463, with phenylalanine significantly reduced interaction with FRS2α (Fig. 5A). Similar experiments with the truncated PTB domain revealed that interaction of the PTB and FGFR1 was not affected by the mutations (supplemental Fig. 1, published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org).

Figure 5.

Tyrosine Phosphorylations of FGFR1 But Not FRS2α Promote Interaction of FGFR1 and FRS2α

A and B, Sf9 cells coexpressing FRS2α and FGFR1 mutants (A) or FGFR1 and FRS2α mutants (B) were pulled down with Ni- or heparin-beads as specified for Western analysis with the indicated antibodies. C, 293T cells transiently expressing the indicated FRS2 and FGFR1βb1 constructs were lysed with or without prior treatment of FGF2 for 10 min. The lysates were incubated with Ni- and heparin-beads as indicated. The specifically bound fractions were Western blotted with the indicated antibodies. βa1, FGFR1βa1; βb1, FGFR1βb1; Y463F, Y653/4F, Y730, Y766F, FGFR1βa1 isoforms with a substitution of the indicated tyrosine residue with phenylalanine residue; 196F, 306F, 349F, 392F, 436F, 471F, FRS2α with a substitution of the indicated tyrosine residue with phenylalanine residue; 6F, FRS2α mutant with substitutions of all six tyrosine phosphorylation sites with phenylalanine; V, vector only; PD, pull-down; WB, Western blot; pFGFR, phosphorylated FGFR1; pFRS2α, phosphorylated FRS2α; R1, anti-FGFR1 antibody; His, anti-His-tag antibody; pTyr, anti-phosphotyrosine antibody.

FRS2α has six tyrosine phosphorylation sites. To investigate whether the tyrosine phosphorylation on FRS2α promoted FGFR1/FRS2α interaction, the tyrosine phosphorylation sites on FRS2α were substituted with phenylalanine residues. The mutants were coexpressed with FGFR1 in Sf9 cells. Pull-down assays showed that the FRS2α mutants with mutations on a single tyrosine phosphorylation site and on all six tyrosine phosphorylation sites remained active in interacting with the FGFR1 kinase, although the interaction was somewhat attenuated by the mutations (Fig. 5B). In addition, all mutants, except 6F, were tyrosine phosphorylated by the FGFR1 kinase. Thus, the results demonstrate that the six tyrosine phosphorylation sites on FRS2α have only a limited impact on interaction with FGFR1. The FGFR1βb1 isoform devoid of the alternatively spliced VT motif bound and phosphorylated FRS2α, although the binding was relatively weaker than that of the VT-positive isoform, FGFR1βa1 (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, similar experiments with 293 cells showed that binding of FRS2α, but not FRS2β, to FGFR1βb1 was enhanced by FGF treatment (Fig. 5C). The results suggest that the VT motif, although not obligatory for FGFR1/FRS2 binding, enhances the binding.

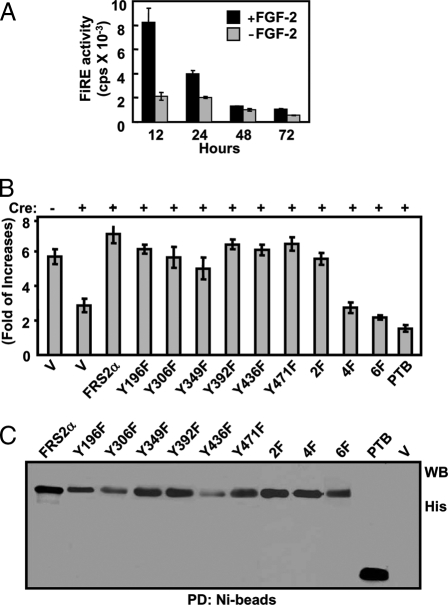

We then tested whether the six phosphorylation sites contributed to FGFR1 signaling specificity. The two Shp2 binding sites (Tyr436 and Tyr471) of FRS2α are generally more important for mediating mitogenic signals than the four Grb2 binding sites (Tyr196, Tyr306, Tyr349, and Tyr392) (4). Because the FGF activates the FiRE independent of its mitogenicity (12), we asked whether FRS2α was essential for mediating FiRE activation in Frs2αnull MEFs (37). The results demonstrated that 48 h after transfection with Cre cDNA, the Frs2αflox MEFs failed to respond to FGF2 in activation of the FiRE-luciferase reporter (Fig. 6A). Together with the data in Fig. 6B that cotransfection with wild-type FRS2α restored the luciferase expression, the time-dependent reduction in luciferase activity indicated that endogenous Frs2α alleles were required for FGF2-induced FiRE activation

Figure 6.

The Grb2-Recruiting Sites on FRS2α Are Essential for Mediating FGF2 Signals to Activate the FiRE Transcription Enhancer

A, Frs2αflox/flox MEF cells cotransfected with PCMV-Cre and FiRE-luciferase reporter plasmids were incubated with 2 ng/ml FGF2 for the indicated times. The cells were then lysed, and the luciferase activity was analyzed. B, Frs2αflox/flox MEF cells cotransfected with PCMV-Cre and FiRE-luciferase reporter plasmids were stimulated with FGF2 overnight, and the luciferase activity was analyzed. After being normalized with cell numbers, the data in A and B are presented as folds of increases in response to FGF2 treatments and are means and sd of triplicate experiments. C, The same transfected MEF cells as in B were lysed. The FRS2α recombinant proteins were immobilized on Ni-beads and Western analyzed with the anti-His-tag antibody. 196F, 306F, 349F, 392F, 436F, 471F, FRS2α with a substitution of the indicated tyrosine residue with phenylalanine residue; 2F, FRS2α mutant with substitutions of the two Shp2-binding tyrosines with phenylalanine; 4F, FRS2α mutant with substitution of the four Grb2-binding tyrosines with phenylalanine; 6F, FRS2α mutant with substitutions of all six phosphorylation sites with phenylalanine; V, vector only.

We then tested which substrate binding sites were more important for mediating the FiRE-activating signals by rescuing with mutant FRS2α carrying mutations on the phosphorylation sites. The results showed that expression of wild-type FRS2α restored the FGF2 activity to activate the FiRE-luciferase reporter, whereas elimination of all six phosphorylation sites (6F) prevented FRS2α from mediating FiRE-activating signals (Fig. 6, B and C). Disruption of all four Grb2-binding sites abolished the capacity of FRS2α to mediate FiRE activation, whereas disruption of the two Shp2-binding sites, as well as a single phosphorylation site, had only limited impact on the capacity. The results suggest that activation of the FiRE reporter is a composite outcome of signals mediated by the four Grb2-recruiting sites. Together with literature data that Grb2-binding sites are generally less important for mediating mitogenic signals than are the Shp2-binding sites (4), the results here, for the first time, demonstrate the specific activity relayed by the four Grb2-binding sites and show that the FGFR1 kinase regulates the FiRE activation via pathways different from those for proliferation.

DISCUSSION

FRS2α is an adaptor protein in the FGF signaling axis that links the FGFR kinase to multiple downstream signaling cascades and is itself a substrate of the FGFR1 tyrosine kinase. Here we report that although both FRS2α and FRS2β bound to unactivated FGFR1, activation of the FGFR1 kinase promoted FGFR1 binding to FRS2α but not FRS2β. In contrast, truncated PTB domains of both FRS2α and FRS2β bound FGFR1 strongly, and the binding was independent of FGFR1 activation. Because 1) PTB bound unphosphorylated FGFR1 better than did the full-length FRS2, 2) receptor autophosphorylation promoted binding to full-length FRS2α, and 3) binding of PTB to the FGFR1 kinase was independent of tyrosine phosphorylation, the results suggest that the C-terminal sequence downstream of the PTB domain negatively regulates the FGFR1/FRS2α binding and that the negative regulation is abrogated by tyrosine phosphorylations. It remains to be elucidated how receptor tyrosine autophosphorylation changes the three-dimensional conformation of the FGFR1 kinase domain and eliminates the negative impact of the effector domain on the binding.

Although FRS2α and FRS2β share high homology in amino acid sequences and structure domains, the two FRS2 members have very distinct expression patterns (5). Whether the two FRS2 members have similar functions in mediating FGF signals is not well understood, although it has been shown that FRS2β can compensate for the loss of FRS2α with respect to MAPK pathway activation in MEF cells (7). Here we demonstrate that although both FRS2α and FRS2β bind unactivated FGFR1, activation of FGFR1 kinase activity promotes binding only of FRS2α, but not FRS2β, to FGFR1, implying that the two FRS2 members may have distinct roles in mediating the regulatory signals of FGFR tyrosine kinases.

The data here showed that the alternatively spliced VT motif in the juxtamembrane domain was not obligatory for FGFR1 interaction with FRS2 (Fig. 1); yet, the VT-positive isoform generally bound FRS2 better than did the VT-negative isoform. Thus, the difference of the two FGFR1 isoforms in binding to FRS2α was quantitative, rather than qualitative. The result, although different from previously reported observations (15,22,25), is not contradictory because both our data and the literature show that the VT-positive isoform binds FRS2α better than does the VT-negative isoform. It is likely the discrepancy is due to detailed differences in assay conditions and construct, because we had optimized the pull-down conditions to improve the pull-down efficiency for the interaction of endogenous full-length FGFR1 and FRS2 in mammalian cells.

To date, how the FGF activates the transcription enhancer activity of the FiRE element is still not well characterized, although it has been shown that cooperation between protein kinase A and the Ras/ERK signaling pathway is necessary (38). Inhibition of both ERK and p38 MAPK pathways diminishes FiRE activation by FGF2 (35). Among the six tyrosine phosphorylation sites on FRS2, the two Shp2-binding sites are primarily responsible for mediating Ras/ERK activation by the FGF, whereas the Grb2-binding sites are for recruitment of Gab1, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and ubiquitin ligase Cb1 (24). The data here show that the Grb2-associated pathways were more important for FRS2α to mediate FGF2 signals for activating FiRE. Because the Grb2-associated pathways are less important for FRS2α to mediate mitogenic signals than the Shp2-associated pathway, the results suggest that the FiRE-activating pathway is different from mitogenic pathways where the Shp2-binding sites are essential.

It has been shown that expression of the PTB domain of FRS2α in mammalian cells prevents FGF from activating MAPK and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathways in the cells and attenuates FGF1 activity to promote antiestrogen-resistant growth in human breast carcinoma cells (39). The data here further demonstrate that the FRS2α-PTB domain exhibited a higher dominant-negative activity for FGF2 activity in 3T3 cells than did the full-length inactive mutant. This is consistent with the data that the PTB domain bound FGFR1 more strongly than did the full-length FRS2α and that the PTBα/FGFR1 binding was constitutive and phosphorylation independent. Therefore, the FRS2α-PTB domain may be used as a molecule to shut down FGF signaling pathways in malignant cells, which have been shown to be aberrantly activated in tumors of variable tissue origins.

In summary, the data here suggest that FRS2α binding to the FGFR1 kinase is regulated through tyrosine autophosphorylation of the receptor and demonstrate that substrate-recruiting sites on FRS2α contribute to specificity of the FGF signaling axis. Furthermore, the results here suggest new venues for manipulating the FGF signaling axis based on selective or complete inhibition of FRS2α activation, which can be of great therapeutic potential.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of FRS2 Mutants

The cDNA encoding the Y196F mutant fragment was PCR amplified from FRS2α cDNA templates with primers pSNT1-1 (13) and a p196 (TGTAGTGTTGACAAAGGTATGTAC); the cDNA for the Y306F fragment with primers p306 (TCTGTTAACAAACTGCTGTTTGAAAATATA) and p436 (CAAGTCAACCTGTATGAAATTAAG); the cDNA for the Y349F fragment with primers pSNT1–2 (13) and p349-1 (TTATTAAACTTCGAAAATCTACCA); the cDNA for the Y392F fragment with primers p392 (TAATCTAGATCCAATGCATAACTTTGTAAA)and p471-2 (CTCTCGATGTCTATCACGGCAAAGAGCTCT); the cDNA for the Y436F fragment with primers p392 and p436; and the cDNA for the Y471F fragment with primers pSNT1-2 and p471-1 (ACAGAGCTCTTTGCCGTGATAGACATCGAG). The mutant cDNA fragments were ligated with context sequences for full-length FRS2α mutants bearing a single point mutation or all six substitutions. Other FRS2α and FGFR mutants were prepared as described (18). The resulting full-length FRS2α cDNAs were sequence verified and subcloned to pVL1393 for preparation of recombinant baculoviruses or pcDNA-zeo-3.1(+) for expression in mammalian cells (18).

Construction and Expression of Wild-Type and Mutant FRS2β

cDNAs encoding for full-length mouse FRS2β were generated by ligation of two RT-PCR fragments cloned from kidney RNA pools with primers ms2-1 (CCGATAGGATCCTCTGACACCATGGGGAGC) and ms2-2 (GTGATGGGGAGGGTCCTGCATGCC), and ms2-3 (CAGGTGATGAAGTGCCAGAGCCTC) and ms2-4 (GCAGGCGAATTCCCAGGTCTACAGAGGCAG), respectively. The cDNA for PTBβ-His was generated with PCR-mediated mutagenesis with primers ms2-1 and ms2-6 (GCCCTCGAGAGTACTAGGGCAGCCAGGGAAGCCATT) with the full-length FRS2β template as described (18). The resulting cDNAs were subcloned in pVL1392 vector for preparation of recombinant baculoviruses for expression in Sf9 insect cells or pcDNA-zeo-3.1(+) vector for expression in mammalian cells.

Transfections and Phosphorylation of Endogenous FRS2α in Mammalian Cells

Overnight cultured 3T3 cells (1 × 106 cells in 10-cm dishes) were transfected with 5 μg of the indicated plasmids as above. The cells were incubated at 37 C for 24 h, and the culture media were then changed to a serum-free DMEM containing 10 μg/ml heparin for serum starvation. After incubation at 37 C for 12 h, the cells were then stimulated with 10 ng/ml FGF2 for the indicated time before being lysed with 500 μl lysis buffer. The cell lysates were Western analyzed with the indicated antibodies. Where indicated, the endogenous FRS2α in the cell lysates was pulled down with 10 μl p13Suc1 beads before Western analyses as described (12).

Pull-Down and Western Blot Assays

The mammalian cells (3 × 106) or insect cells expressing the indicated recombinant proteins were lysed with 0.5 ml of 1% Triton X-100 in PBS. For Ni-bead pull-down, the cell lysates were diluted with an equal volume of the washing buffer (0.5 m NaCl, 50 mm imidazole, and 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5), and the mixtures were gently rocked with 30 μl of Ni-agarose beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Lab, Uppsala, Sweden) at 4 C for 45 min. The beads were then washed three times with 1 ml washing buffer, and specifically bound fractions were recovered from beads with 30 μl SDS sample buffer for Western analyses.

For pull-down with heparin-beads, the cell lysates were mixed with 15 μl heparin-beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and 0.5 ml PBS as indicated and incubated at 4 C for 1.5 h. The beads were washed three times with 0.5 ml 0.2 n NaCl-PBS, and specifically bound fractions were recovered from the beads with 30 μl SDS sample buffer for Western analyses.

For immunoprecipitations, TRAMP-C2 cell lysates equivalent to 2 mg total proteins in 1 ml hypotonic gentle lysis buffer [10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100,1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml aprotinin,1 μg/ml leupeptin) were incubated with 15 μl of the indicated anti-FRS2α or anti-FGFR1 (M5G10) antibody at 4 C overnight. The immunocomplexes were pulled down with 40 μl protein A beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) by incubation at 4 C for 2 h. The beads were washed three times with 0.5 ml NET-2 wash buffer [50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 0.05% Triton X-100). The specifically bound fractions were recovered from the beads with 30 μl SDS sample buffer for Western analyses. Pull-down experiments with anti-FGFR1 antibody had a high background likely due to the quality of the antibody.

The source and concentration of antibodies used in the Western analyses were anti-phosphotyrosine 4G10 (1:5000; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), anti-His (1:3000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), and anti-FGFR1 antibodies (17A3, 1:3000) (40). Immunoreactivity was visualized with the Enhanced Chemiluminescence-2000 reagents (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For reprobing, the membranes were stripped off the antibodies by incubation with 15 ml stripping buffer [62.5 mm Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2% SDS, 100 mm β-mercaptoethanol] at 50 C for 30 min before incubation with new antibodies.

Establishing MEF Cultures and FiRE Assay

MEF cells were prepared from E14.5 embryos carrying homozygous LoxP-flanked Frs2α (Frs2αflox) alleles (37). Briefly, the embryos were minced in 3 ml ice-cold 0.25% trypsin-EDTA solution (Sigma-Adrich, St. Louis, MO) and then were further incubated at 37 C for 20 min. The isolated cells were propagated and maintained in 10% fetal bovine serum/DMEM until being used. The cells (2 × 105) were transfected with 1 μg of the pCMV-Cre plasmid to inactivate Frs2α alleles, the FiRE reporter, and indicated FRS2α mutants with 5 μl Lipofectamine-Plus reagents (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer’s suggestions. Disruption of the Frs2αflox alleles was confirmed by PCR analyses (data not shown), and loss of FRS2α activity was evaluated with the FiRE-luciferase reporter analyses (12).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Wallace L. McKeehan for critical review and helpful discussions of the manuscript and Mary Cole and Xinchen Wang for critical reading of this manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by CA96824 from the National Cancer Institute, DAMD17-03-0014 from the Department of Defense, and AHA0655077Y from the America Heart Association.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online September 27, 2007

Abbreviations: E7, Embryonic d 7; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; PTB, phosphotyrosine-binding domain.

References

- Kouhara H, Hadari YR, Spivak-Kroizman T, Schilling J, Bar-Sagi D, Lax I, Schlessinger J 1997 A lipid-anchored Grb2-binding protein that links FGF-receptor activation to the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway. Cell 89:693–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong SH, Goh KC, Lim YP, Low BC, Klint P, Claesson-Welsh L, Cao X, Tan YH, Guy GR 1996 Suc1-associated neurotrophic factor target (SNT) protein is a major FGF-stimulated tyrosine phosphorylated 90-kDa protein which binds to the SH2 domain of GRB2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 225:1021–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin SJ, Cleghon V, Kaplan DR 1993 SNT, a differentiation-specific target of neurotrophic factor-induced tyrosine kinase activity in neurons and PC12 cells. Mol Cell Biol 13:2203–2213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadari YR, Gotoh N, Kouhara H, Lax I, Schlessinger J 2001 Critical role for the docking-protein FRS2α in FGF receptor-mediated signal transduction pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:8578–8583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall K, Kubu C, Verdi JM, Meakin SO 2001 Developmental expression patterns of the signaling adapters FRS-2 and FRS-3 during early embryogenesis. Mech Dev 103:145–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, McDougall K, Kubu CJ, Verdi JM, Meakin SO 2003 Genomic organization and comparative sequence analysis of the mouse and human FRS2, FRS3 genes. Mol Biol Rep 30:15–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh N, Laks S, Nakashima M, Lax I, Schlessinger J 2004 FRS2 family docking proteins with overlapping roles in activation of MAP kinase have distinct spatial-temporal patterns of expression of their transcripts. FEBS Lett 564:14–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery AW, Figueroa C, Vojtek AB 2006 UNC-51-like kinase regulation of fibroblast growth factor receptor substrate 2/3. Cell Signal 19:177–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada A, Katoh H, Negishi M 2005 Direct interaction of Rnd1 with FRS2β regulates Rnd1-induced down-regulation of RhoA activity and is involved in fibroblast growth factor-induced neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. J Biol Chem 280:18418–18424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Gotoh N, Zhang S, Shibuya M, Yamamoto T, Tsuchida N 2004 SNT-2 interacts with ERK2 and negatively regulates ERK2 signaling in response to EGF stimulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 324:1011–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Watanabe M, Chikamori M, Kido Y, Yamamoto T, Shibuya M, Gotoh N, Tsuchida N 2006 Unique role of SNT-2/FRS2β/FRS3 docking/adaptor protein for negative regulation in EGF receptor tyrosine kinase signaling pathways. Oncogene 25:6457–6466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, McKeehan K, Yu C, McKeehan WL 2002 Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 phosphotyrosine 766: molecular target for prevention of progression of prostate tumors to malignancy. Cancer Res 62:1898–1903 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F 2002 Cell- and receptor isotype-specific phosphorylation of SNT1 by fibroblast growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 38:178–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xian W, Schwertfeger KL, Rosen JM 2007 Distinct roles of Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 1 and 2 in regulating cell survival and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Mol Endocrinol 21:987–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Lee KW, Goldfarb M 1998 Novel recognition motif on fibroblast growth factor receptor mediates direct association and activation of SNT adapter proteins. J Biol Chem 273:17987–17990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhalluin C, Yan KS, Plotnikova O, Lee KW, Zeng L, Kuti M, Mujtaba S, Goldfarb MP, Zhou MM 2000 Structural basis of SNT PTB domain interactions with distinct neurotrophic receptors. Mol Cell 6:921–929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon SJ, MacDonald JI, Robinson KN, Kubu CJ, Meakin SO 2006 Trk receptor binding and neurotrophin/fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-dependent activation of the FGF receptor substrate (FRS)-3. Biochim Biophys Acta 1763:366–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Lin Y, Bowles C, Wang F 2004 Direct cell cycle regulation by the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) kinase through phosphorylation-dependent release of Cks1 from FGFR substrate 2. J Biol Chem 279:55348–55354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackenridge S, Wilkie AO, Screaton GR 2003 Efficient use of a ‘dead-end’ GA 5′ splice site in the human fibroblast growth factor receptor genes. EMBO J 22:1620–1631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterno GD, Ryan PJ, Kao KR, Gillespie LL 2000 The VT+ and VT− isoforms of the fibroblast growth factor receptor type 1 are differentially expressed in the presumptive mesoderm of Xenopus embryos and differ in their ability to mediate mesoderm formation. J Biol Chem 275:9581–9586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan M, Wang F, Xu J, Crabb JW, Hou J, McKeehan WL 1993 An essential heparin-binding domain in the fibroblast growth factor receptor kinase. Science 259:1918–1921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgar HR, Burns HD, Elsden JL, Lalioti MD, Heath JK 2002 Association of the signaling adaptor FRS2 with fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (Fgfr1) is mediated by alternative splicing of the juxtamembrane domain. J Biol Chem 277:4018–4023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch RV, Soriano P 2006 Context-specific requirements for Fgfr1 signaling through Frs2 and Frs3 during mouse development. Development 133:663–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh N, Ito M, Yamamoto S, Yoshino I, Song N, Wang Y, Lax I, Schlessinger J, Shibuya M, Lang RA 2004 Tyrosine phosphorylation sites on FRS2α responsible for Shp2 recruitment are critical for induction of lens and retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:17144–17149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong SH, Guy GR, Hadari YR, Laks S, Gotoh N, Schlessinger J, Lax I 2000 FRS2 proteins recruit intracellular signaling pathways by binding to diverse targets on fibroblast growth factor and nerve growth factor receptors. Mol Cell Biol 20:979–989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Goldfarb M 2001 Multiple effector domains within SNT1 coordinate ERK activation and neuronal differentiation of PC12 cells. J Biol Chem 276:13049–13056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S, Yoshino I, Shimazaki T, Murohashi M, Hevner RF, Lax I, Okano H, Shibuya M, Schlessinger J, Gotoh N 2005 Essential role of Shp2-binding sites on FRS2α for corticogenesis and for FGF2-dependent proliferation of neural progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:15938–15988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lax I, Wong A, Lamothe B, Lee A, Frost A, Hawes J, Schlessinger J 2002 The docking protein FRS2α controls a MAP kinase-mediated negative feedback mechanism for signaling by FGF receptors. Mol Cell 10:709–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou J, McKeehan K, Kan M, Carr SA, Huddleston MJ, Crabb JW, McKeehan WL 1993 Identification of tyrosines 154 and 307 in the extracellular domain and 653 and 766 in the intracellular domain as phosphorylation sites in the heparin-binding fibroblast growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase (flg). Protein Sci 2:86–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi M, Dikic I, Sorokin A, Burgess WH, Jaye M, Schlessinger J 1996 Identification of six novel autophosphorylation sites on fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 and elucidation of their importance in receptor activation and signal transduction. Mol Cell Biol 16:977–989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi E, Kan M, Xu J, Wang F, Hou J, McKeehan WL 1993 Control of fibroblast growth factor receptor kinase signal transduction by heterodimerization of combinatorial splice variants. Mol Cell Biol 13:3907–3918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi M, Dionne CA, Li W, Li N, Spivak T, Honegger AM, Jaye M, Schlessinger J 1992 Point mutation in FGF receptor eliminates phosphatidylinositol hydrolysis without affecting mitogenesis. Nature 358:681–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters KG, Marie J, Wilson E, Ives HE, Escobedo J, Del Rosario M, Mirda D, Williams LT 1992 Point mutation of an FGF receptor abolishes phosphatidylinositol turnover and Ca2+ flux but not mitogenesis. Nature 358:678–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola P, Kontusaari S, Kauppi T, Maata A, Jalkanen M 1998 Wound reepithelialization activates a growth factor-responsive enhancer in migrating keratinocytes. FASEB J 12:959–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola P, Vihinen T, Maatta A, Jalkanen M 1997 Activation of an enhancer on the syndecan-1 gene is restricted to fibroblast growth factor family members in mesenchymal cells. Mol Cell Biol 17:3210–3219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeehan WL, Wang F, Kan M 1998 The heparan sulfate-fibroblast growth factor family: diversity of structure and function. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 59:135–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Zhang J, Liu G, McKeehan K, Wang F 2007 Generation of an FRS2a conditional null allele. Genesis 45:455–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pursiheimo JP, Saari J, Jalkanen M, Salmivirta M 2002 Cooperation of protein kinase A and Ras/ERK signaling pathways is required for AP-1-mediated activation of fibroblast growth factor-inducible response element (FiRE). J Biol Chem 277:25344–25355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuvakhova M, Thottassery JV, Hays S, Qu Z, Rentz SS, Westbrook L, Kern FG 2006 Expression of the SNT-1/FRS2 phosphotyrosine binding domain inhibits activation of MAP kinase and PI3-kinase pathways and antiestrogen resistant growth induced by FGF-1 in human breast carcinoma cells. Oncogene 25:6003–6014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Nakahara M, Crabb JW, Shi E, Matuo Y, Fraser M, Kan M, Hou J, McKeehan WL 1992 Expression and immunochemical analysis of rat and human fibroblast growth factor receptor (flg) isoforms. J Biol Chem 267:17792–17803 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.